Disease Epidemiology: West Nile Fever Outbreak Modeling and Prediction

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/26

|12

|3426

|13

Report

AI Summary

This report delves into the epidemiology of West Nile Fever (WNV), focusing on disease outbreak modeling and prediction. It begins with an introduction to epidemiology and the importance of predictive models in preventing disease outbreaks. The report then provides a detailed overview of WNV, including its history, disease characteristics, and progression, as well as current containment strategies. It explains the vector-borne transmission of WNV, its symptoms, and the risk factors associated with neuro-invasive forms of the disease. The core of the report lies in the application of epidemiological models, specifically the SIR (Susceptible, Infected, Recovered) model and SEIS model, to predict future outbreaks. The report explains the components of the SIR model and presents a non-linear equation for prediction, discussing the implications of the model for disease control. Finally, the report discusses how the SEIS model can be used to predict future outbreaks if a cure for WNV is discovered. The report highlights the importance of preventative measures and contact precautions in controlling the spread of WNV in the absence of a vaccine.

DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author note:

DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author note:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

Introduction

Epidemiology is the study dealing with understanding the dynamics of disease outbreak

and transmission so as to facilitate the development of preventive mechanisms for the same.

Despite the prevalence of extensive medical advancements as well as vaccines, it is worthwhile

to remember that disease outbreaks and epidemics yield considerable financial losses and

casualties across the world and are often too complex in nature so as to be prevented by merely

treatment or vaccination alone. Thus, to ensure timely detection and prediction of a disease

outbreak, engaging in an epidemiological formula may prove to be beneficial and cost effective

(Ramos da Silva & Gao, 2016).

The following paper thus aims to discuss on predictive models of infectious diseases and

disease outbreaks which can then be used to predict and prevent future incidences and associated

mortalities. The disease which will be chosen for the same is West Nile Fever (WNF) caused by

the West Nile Virus (WNV). To explain the same, a susceptible, exposed and recovered (SIR)

model coupled with a no-linear, differential equation will be considered. For the purpose of

predicting a future predictions in case of successful interventions, an exponential based

epidemiology equation will be used, with the help of a compartmental Susceptible, Exposed,

Infectious and Susceptible (SEIS) model.

Discussion

Disease Characteristics

Disease History

The West Nile Virus (WNV) is the key causative factor for the West Nile Fever (WNF) –

an infectious disease with debilitating neurological symptoms. This infectious disease has been

Introduction

Epidemiology is the study dealing with understanding the dynamics of disease outbreak

and transmission so as to facilitate the development of preventive mechanisms for the same.

Despite the prevalence of extensive medical advancements as well as vaccines, it is worthwhile

to remember that disease outbreaks and epidemics yield considerable financial losses and

casualties across the world and are often too complex in nature so as to be prevented by merely

treatment or vaccination alone. Thus, to ensure timely detection and prediction of a disease

outbreak, engaging in an epidemiological formula may prove to be beneficial and cost effective

(Ramos da Silva & Gao, 2016).

The following paper thus aims to discuss on predictive models of infectious diseases and

disease outbreaks which can then be used to predict and prevent future incidences and associated

mortalities. The disease which will be chosen for the same is West Nile Fever (WNF) caused by

the West Nile Virus (WNV). To explain the same, a susceptible, exposed and recovered (SIR)

model coupled with a no-linear, differential equation will be considered. For the purpose of

predicting a future predictions in case of successful interventions, an exponential based

epidemiology equation will be used, with the help of a compartmental Susceptible, Exposed,

Infectious and Susceptible (SEIS) model.

Discussion

Disease Characteristics

Disease History

The West Nile Virus (WNV) is the key causative factor for the West Nile Fever (WNF) –

an infectious disease with debilitating neurological symptoms. This infectious disease has been

2DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

found prevalently across populations residing in countries like Europe, Africa, North America,

the Middle East and the Western part of Asia. The virus undergoes vector-borne transmission,

that is, via mosquito bites. The WNV belongs to viruses of the genus ‘Flavivirus’ which is a part

of the antigenic and Japanese encephalitis complex known as the ‘Flaviviridae’ family. The key

hosts responsible for the transmission of WNV are birds, which is why, the cycle of WNV

disease transmission and outbreak is limited to ‘birds-mosquitoes-birds’ (Tisoncik-Go & Gale Jr,

2019).

It has been evidenced that disease outbreaks by the WNV first originated in Africa, where

the virus was isolated first from a woman was residing in the Ugandan district of West Nile, in

the year 1937. In the year 1953, the virus was found to be prevalent in birds like crows which

were residing in the delta region of West Nile (Parkash et al., 2019). Since the last 5 decades, the

prevalence rate of incidences of infections caused by WNV have increased extensively, most

notably in the United States during early 21st century which was in turn attributed to have been

imported from disease incidences reported in African and Middle East regions like Tunisia and

Israel. The high incident rate of WNV in the United States reported in the decade ranging from

1999 to 2000 demonstrated the highly infectious, transmissible and fatal nature of this condition,

which in turn, paved the way for development of epidemiological and disease based modelling

and preventive strategies (Williamson et al., 2017).

Disease Progression

The transmission and progression of infection by WNV across humans is facilitated

largely via mosquitoes which have been infected and are carriers of the same (Sinigaglia et al.,

2019). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2017) also denoted the positive associated

between high rates of WNV infection transmission and the summer and monsoon season or

found prevalently across populations residing in countries like Europe, Africa, North America,

the Middle East and the Western part of Asia. The virus undergoes vector-borne transmission,

that is, via mosquito bites. The WNV belongs to viruses of the genus ‘Flavivirus’ which is a part

of the antigenic and Japanese encephalitis complex known as the ‘Flaviviridae’ family. The key

hosts responsible for the transmission of WNV are birds, which is why, the cycle of WNV

disease transmission and outbreak is limited to ‘birds-mosquitoes-birds’ (Tisoncik-Go & Gale Jr,

2019).

It has been evidenced that disease outbreaks by the WNV first originated in Africa, where

the virus was isolated first from a woman was residing in the Ugandan district of West Nile, in

the year 1937. In the year 1953, the virus was found to be prevalent in birds like crows which

were residing in the delta region of West Nile (Parkash et al., 2019). Since the last 5 decades, the

prevalence rate of incidences of infections caused by WNV have increased extensively, most

notably in the United States during early 21st century which was in turn attributed to have been

imported from disease incidences reported in African and Middle East regions like Tunisia and

Israel. The high incident rate of WNV in the United States reported in the decade ranging from

1999 to 2000 demonstrated the highly infectious, transmissible and fatal nature of this condition,

which in turn, paved the way for development of epidemiological and disease based modelling

and preventive strategies (Williamson et al., 2017).

Disease Progression

The transmission and progression of infection by WNV across humans is facilitated

largely via mosquitoes which have been infected and are carriers of the same (Sinigaglia et al.,

2019). The World Health Organization (WHO, 2017) also denoted the positive associated

between high rates of WNV infection transmission and the summer and monsoon season or

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

during temperature climatic condition found prevalently between the months of July and October

in Europe and the United States. WNV infects mosquitoes after the latter feeds on infected birds.

After the viral strain transferred to the salivary glands of the vector, it is likely that the mosquito

injects the same into other organisms and humans after feeding on blood from the latter.

Ironically, the infection has been found to be asymptomatic in approximately 80% of those who

have been infected (Sinigaglia et al., 2019). The remaining approximate 20 to 30% are likely to

be infected West Nile Fever – an infections with symptoms like body aches and head aches,

persistent fever, vomiting, nausea, rash and an inflamed lymphatic system (WHO, 2017). The

predicted incubated period for the above symptoms to appear is 3 days to 14 days. However, it

has been estimated that approximately one out of 150 infections are at risk of acquiring a neuro-

invasive form of WNV infection, known as West Nile meningitis or encephalitis or

poliomyelitis, and is characterized by fatal neurological symptoms like convulsions, tremors,

stupor, muscular pain and weakness, coma, disorientation, persistent high fever and headaches

and fatigue. The risk of acquiring such symptoms, though rare, are higher in case of older

individuals aged 50 years or above and those whose immunological status is likely to be

compromised, that is patients undergoing organ transplantation (Ronca, Murray & Nolan, 2019).

Disease Containment

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2019), fever due to

WNV is caused in individuals who have been bitten by mosquitos infected with the same. It has

been estimated that the virus is likely to cause fever and the above identified symptoms across

one out of a total of five individuals who may be bitten by a mosquito infected by WNV.

Additionally, it has been estimated that the WNV may also cause fatal neurological symptoms

and possibly death in one out of a total of 150 individuals bitten by an infected mosquito. No

during temperature climatic condition found prevalently between the months of July and October

in Europe and the United States. WNV infects mosquitoes after the latter feeds on infected birds.

After the viral strain transferred to the salivary glands of the vector, it is likely that the mosquito

injects the same into other organisms and humans after feeding on blood from the latter.

Ironically, the infection has been found to be asymptomatic in approximately 80% of those who

have been infected (Sinigaglia et al., 2019). The remaining approximate 20 to 30% are likely to

be infected West Nile Fever – an infections with symptoms like body aches and head aches,

persistent fever, vomiting, nausea, rash and an inflamed lymphatic system (WHO, 2017). The

predicted incubated period for the above symptoms to appear is 3 days to 14 days. However, it

has been estimated that approximately one out of 150 infections are at risk of acquiring a neuro-

invasive form of WNV infection, known as West Nile meningitis or encephalitis or

poliomyelitis, and is characterized by fatal neurological symptoms like convulsions, tremors,

stupor, muscular pain and weakness, coma, disorientation, persistent high fever and headaches

and fatigue. The risk of acquiring such symptoms, though rare, are higher in case of older

individuals aged 50 years or above and those whose immunological status is likely to be

compromised, that is patients undergoing organ transplantation (Ronca, Murray & Nolan, 2019).

Disease Containment

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2019), fever due to

WNV is caused in individuals who have been bitten by mosquitos infected with the same. It has

been estimated that the virus is likely to cause fever and the above identified symptoms across

one out of a total of five individuals who may be bitten by a mosquito infected by WNV.

Additionally, it has been estimated that the WNV may also cause fatal neurological symptoms

and possibly death in one out of a total of 150 individuals bitten by an infected mosquito. No

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

vaccine has been established till date, which can prevent or provide immunity against WNV

infection in individuals (Ronca, Murray & Nolan, 2019). Maintenance of contact precautions and

preventive measures have been evidenced to be the only mode of mitigating disease transmission

and outbreaks. The CDC (2019) denotes the need to follow a twofold mode of infection

prevention strategies: firstly, via engaging in personal protective clothing and secondly, via

practicing mosquito repelling strategies. Thus, these preventive strategies can be summarized as:

wearing full length outfits to prevent mosquito bites and using mosquito repellants both

individual as well as in the community, preventing the collection of stagnating bodies of water in

buckets, pools and containers and using additional preventive methods like mosquito repelling

screens and nets (Mallya et al., 2018). Additionally, it has been recommended that communities

engaging in widespread surveillance strategies have improved chances of infection prevention. A

beneficial procedure with regards to the same, includes community reporting to healthcare

organizations in case of notable incidences like high rates of bird deaths in a given region

(Montgomery, 2017).

In addition to vector born transmission, infection by the WNV is also transmitted via

contact between humans in the form of organ transplantation and blood transfusion from an

infected to a healthy individual. Additionally the viral infection may also be transmitted via the

placenta from an infected mother to her baby. Ironically however, the incidence reports of such

human to human transmission have been very rare (Krause et al., 2019). The viral infection is

also not transmitted via droplet modes such as sneezing or coughing as wells via consumption of

birds. It is recommended however, that poultry be cooked well prior to consumption for the

purpose of infection risk prevention. Patients with adverse symptoms need to go hospitalization

coupled with intravenous fluid administration, respiratory support and mitigation for secondary

vaccine has been established till date, which can prevent or provide immunity against WNV

infection in individuals (Ronca, Murray & Nolan, 2019). Maintenance of contact precautions and

preventive measures have been evidenced to be the only mode of mitigating disease transmission

and outbreaks. The CDC (2019) denotes the need to follow a twofold mode of infection

prevention strategies: firstly, via engaging in personal protective clothing and secondly, via

practicing mosquito repelling strategies. Thus, these preventive strategies can be summarized as:

wearing full length outfits to prevent mosquito bites and using mosquito repellants both

individual as well as in the community, preventing the collection of stagnating bodies of water in

buckets, pools and containers and using additional preventive methods like mosquito repelling

screens and nets (Mallya et al., 2018). Additionally, it has been recommended that communities

engaging in widespread surveillance strategies have improved chances of infection prevention. A

beneficial procedure with regards to the same, includes community reporting to healthcare

organizations in case of notable incidences like high rates of bird deaths in a given region

(Montgomery, 2017).

In addition to vector born transmission, infection by the WNV is also transmitted via

contact between humans in the form of organ transplantation and blood transfusion from an

infected to a healthy individual. Additionally the viral infection may also be transmitted via the

placenta from an infected mother to her baby. Ironically however, the incidence reports of such

human to human transmission have been very rare (Krause et al., 2019). The viral infection is

also not transmitted via droplet modes such as sneezing or coughing as wells via consumption of

birds. It is recommended however, that poultry be cooked well prior to consumption for the

purpose of infection risk prevention. Patients with adverse symptoms need to go hospitalization

coupled with intravenous fluid administration, respiratory support and mitigation for secondary

5DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

morbidities for treatment, which generally lasts for a few weeks or even months (Moirano et al.,

2018).

Epidemiological Model, Equation Type and Graph

While no cure or vaccination is present, it has been evidenced that, individuals inflicted

with an infection caused by WNV, are likely to recover within a few months of weeks when

provided with secondary infection prevention and vital signs based support, due to the viral

nature of the disease (Chen et al., 2016). While the associated symptoms may linger and cause

individuals to mildly relapse after several months or years, most individuals recovering from

WNV infections are likely to demonstrate immunity to future incidences of the disease. Thus, for

this reason, based on current evidence concerning preventive, containment and recovery

measures, a compartmental model in the form of a simple SIR model can be considered as the

most appropriate epidemiological for prevention (Liu, Zhang & Chen, 2020).

The SIR model comprises of three compartment, which have been outline as:

S = Individuals who are susceptible to the infection. With regards to the WNV caused

infection, these can include individual communities or groups residing in areas lacking

hygienic or potable water sources, individuals aged 50 years or above and individuals

who are undergoing organ transplantation or blood transfusion.

I – Individuals who are infected with the infection. In the case of infections due to WNV,

these will include individuals infected via a mosquito bite.

R = Individuals who have recovered and are now likely immune to the infection.

To obtain a simple non-linear equation for prediction, we can consider the

following:

morbidities for treatment, which generally lasts for a few weeks or even months (Moirano et al.,

2018).

Epidemiological Model, Equation Type and Graph

While no cure or vaccination is present, it has been evidenced that, individuals inflicted

with an infection caused by WNV, are likely to recover within a few months of weeks when

provided with secondary infection prevention and vital signs based support, due to the viral

nature of the disease (Chen et al., 2016). While the associated symptoms may linger and cause

individuals to mildly relapse after several months or years, most individuals recovering from

WNV infections are likely to demonstrate immunity to future incidences of the disease. Thus, for

this reason, based on current evidence concerning preventive, containment and recovery

measures, a compartmental model in the form of a simple SIR model can be considered as the

most appropriate epidemiological for prevention (Liu, Zhang & Chen, 2020).

The SIR model comprises of three compartment, which have been outline as:

S = Individuals who are susceptible to the infection. With regards to the WNV caused

infection, these can include individual communities or groups residing in areas lacking

hygienic or potable water sources, individuals aged 50 years or above and individuals

who are undergoing organ transplantation or blood transfusion.

I – Individuals who are infected with the infection. In the case of infections due to WNV,

these will include individuals infected via a mosquito bite.

R = Individuals who have recovered and are now likely immune to the infection.

To obtain a simple non-linear equation for prediction, we can consider the

following:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

N denotes a population which is constant and expansive enough to consider all the above

as continuous variables,

‘t’ as a variable of time.

The rate of transition can be considered as ‘y’, thus implying the rate of death or

recovery.

D can be considered as the duration of the disease or infection. Thus, y = 1/D, which

implies that each individual is likely to experience one incidence of recovery time

measured as D units.

Thus, taking insights from the Kermack-McKendrick theoretical model: dS/dt + dI/dt +

dR/dT = 0, which implies that: S(t) + I(t) + R(t) = Constant = N (Chen et al., 2016).

Based on this equation, it can be implied after a disease epidemic has been ended, unless

and until ‘S’ or the number of individuals who are susceptible to WNV infection are absolutely 0

in number within a given point of time (that is, S(0) = 0), it means that not every person

belonging to the given population has undergone recovery and thus, there continues to remain

some who are still susceptible to acquiring this viral infection. Thus, a decline in an epidemic of

WNV fever is likely due to an increase in the number of those individuals who have recovered

rather than a misperception that susceptible individuals have decreased in number (Nasrinpour,

Friesen & McLeod, 2017). Indeed, such a model and formula holds true for the purpose of

predicting and preventing further WNV viral infections. While individuals who are infected are

likely to recover and have low risk of acquiring adverse consequences, individuals bitten by an

infected mosquito or those with compromised immunity are likely to contribute to the epidemic

in the future. For this reason, it is understandable why current disease preventive strategies target

contact precautions as the key mode of disease containment in the absent of a vaccine for WNV

N denotes a population which is constant and expansive enough to consider all the above

as continuous variables,

‘t’ as a variable of time.

The rate of transition can be considered as ‘y’, thus implying the rate of death or

recovery.

D can be considered as the duration of the disease or infection. Thus, y = 1/D, which

implies that each individual is likely to experience one incidence of recovery time

measured as D units.

Thus, taking insights from the Kermack-McKendrick theoretical model: dS/dt + dI/dt +

dR/dT = 0, which implies that: S(t) + I(t) + R(t) = Constant = N (Chen et al., 2016).

Based on this equation, it can be implied after a disease epidemic has been ended, unless

and until ‘S’ or the number of individuals who are susceptible to WNV infection are absolutely 0

in number within a given point of time (that is, S(0) = 0), it means that not every person

belonging to the given population has undergone recovery and thus, there continues to remain

some who are still susceptible to acquiring this viral infection. Thus, a decline in an epidemic of

WNV fever is likely due to an increase in the number of those individuals who have recovered

rather than a misperception that susceptible individuals have decreased in number (Nasrinpour,

Friesen & McLeod, 2017). Indeed, such a model and formula holds true for the purpose of

predicting and preventing further WNV viral infections. While individuals who are infected are

likely to recover and have low risk of acquiring adverse consequences, individuals bitten by an

infected mosquito or those with compromised immunity are likely to contribute to the epidemic

in the future. For this reason, it is understandable why current disease preventive strategies target

contact precautions as the key mode of disease containment in the absent of a vaccine for WNV

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

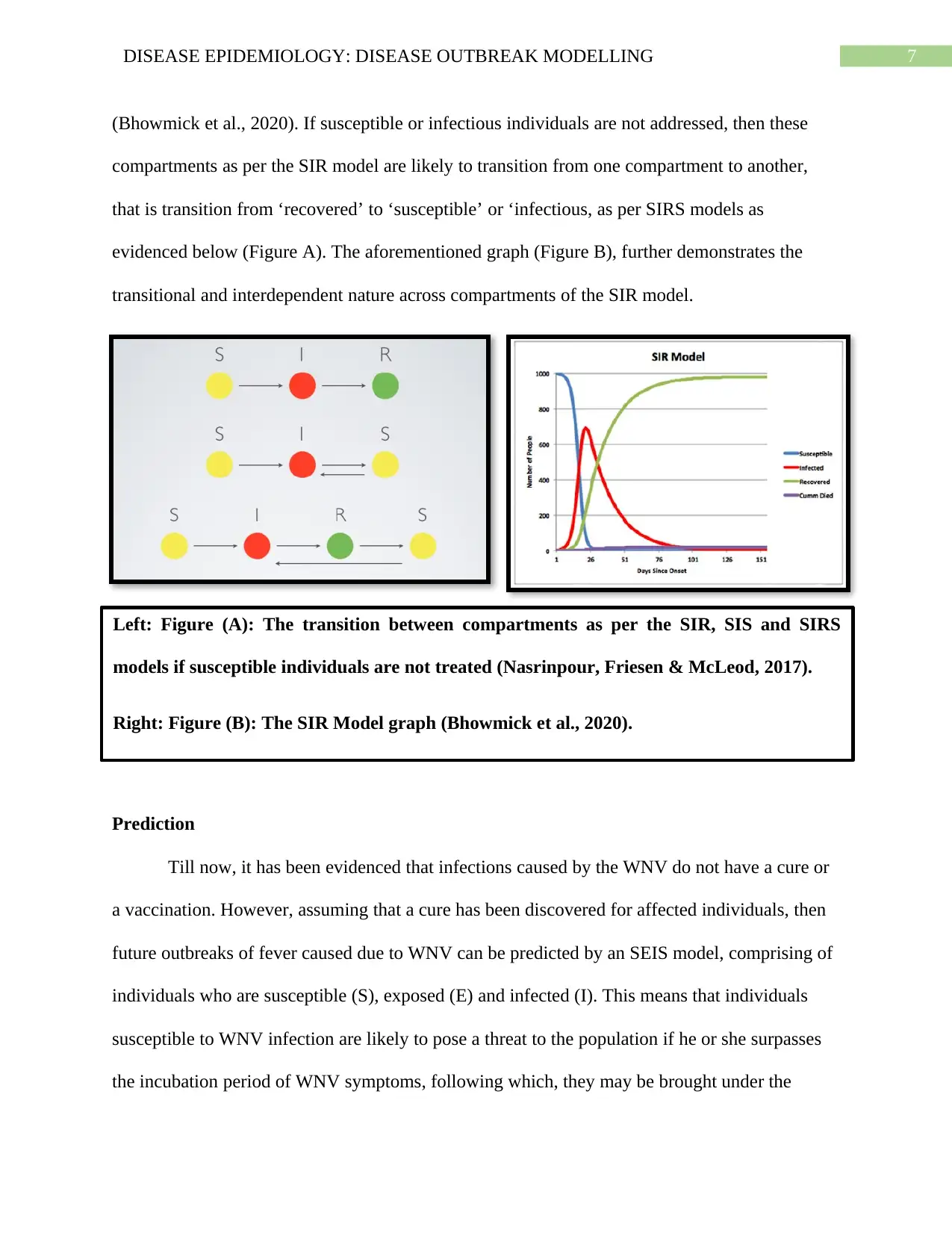

(Bhowmick et al., 2020). If susceptible or infectious individuals are not addressed, then these

compartments as per the SIR model are likely to transition from one compartment to another,

that is transition from ‘recovered’ to ‘susceptible’ or ‘infectious, as per SIRS models as

evidenced below (Figure A). The aforementioned graph (Figure B), further demonstrates the

transitional and interdependent nature across compartments of the SIR model.

Prediction

Till now, it has been evidenced that infections caused by the WNV do not have a cure or

a vaccination. However, assuming that a cure has been discovered for affected individuals, then

future outbreaks of fever caused due to WNV can be predicted by an SEIS model, comprising of

individuals who are susceptible (S), exposed (E) and infected (I). This means that individuals

susceptible to WNV infection are likely to pose a threat to the population if he or she surpasses

the incubation period of WNV symptoms, following which, they may be brought under the

Left: Figure (A): The transition between compartments as per the SIR, SIS and SIRS

models if susceptible individuals are not treated (Nasrinpour, Friesen & McLeod, 2017).

Right: Figure (B): The SIR Model graph (Bhowmick et al., 2020).

(Bhowmick et al., 2020). If susceptible or infectious individuals are not addressed, then these

compartments as per the SIR model are likely to transition from one compartment to another,

that is transition from ‘recovered’ to ‘susceptible’ or ‘infectious, as per SIRS models as

evidenced below (Figure A). The aforementioned graph (Figure B), further demonstrates the

transitional and interdependent nature across compartments of the SIR model.

Prediction

Till now, it has been evidenced that infections caused by the WNV do not have a cure or

a vaccination. However, assuming that a cure has been discovered for affected individuals, then

future outbreaks of fever caused due to WNV can be predicted by an SEIS model, comprising of

individuals who are susceptible (S), exposed (E) and infected (I). This means that individuals

susceptible to WNV infection are likely to pose a threat to the population if he or she surpasses

the incubation period of WNV symptoms, following which, they may be brought under the

Left: Figure (A): The transition between compartments as per the SIR, SIS and SIRS

models if susceptible individuals are not treated (Nasrinpour, Friesen & McLeod, 2017).

Right: Figure (B): The SIR Model graph (Bhowmick et al., 2020).

8DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

exposed group under a given point of time ‘t’ (Chen et al., 2016). This means that if individuals

who do recover from the WNV infection, if they are not immunized or treated within the

incubation period then they are likely to cause infection to the population as evidenced by them

returning to the susceptible compartment. Thus, S -> E -> I -> S as per this model can predict

and regulate WNV disease outbreak by prioritizing timely immunization and treatment of

recovered populations. Current evidence demonstrates exploration of SEIR models where birds

or horses infected with WNV can move to the recovered compartment after treatment based on

the transition from exposed to susceptible groups (S -> E -> I -> R). This is because, as

compared to human, vaccines now exist for WNV prevention in horses (Andayani, Azmi & Sari,

2018).

Conclusion

Thus, to conclude, this paper provides an elaborate and extensive discussion on the key

components underlying the best possible epidemiological model and formulae with regards to

prediction and prevention of disease outbreaks caused by the West Nile Virus. As per current

evidence, despite a few rare cases, individuals generally demonstrate immunity to this viral

infection after recovery. For this reason, a simple compartment based SIR model with a

differential, non-linear equation has been considered for the purpose of predicting disease

outbreaks. For the purpose of future predictions with regards to a cure such as a vaccine, as per

current evidence, a revised SEIS model with an exponential formula can be considered. To

conclude, in addition to advanced treatments there is also a need for the development of

comprehensive predictive models examining disease transmission associated with human to

human infection disseminations via organs, blood or the placenta.

exposed group under a given point of time ‘t’ (Chen et al., 2016). This means that if individuals

who do recover from the WNV infection, if they are not immunized or treated within the

incubation period then they are likely to cause infection to the population as evidenced by them

returning to the susceptible compartment. Thus, S -> E -> I -> S as per this model can predict

and regulate WNV disease outbreak by prioritizing timely immunization and treatment of

recovered populations. Current evidence demonstrates exploration of SEIR models where birds

or horses infected with WNV can move to the recovered compartment after treatment based on

the transition from exposed to susceptible groups (S -> E -> I -> R). This is because, as

compared to human, vaccines now exist for WNV prevention in horses (Andayani, Azmi & Sari,

2018).

Conclusion

Thus, to conclude, this paper provides an elaborate and extensive discussion on the key

components underlying the best possible epidemiological model and formulae with regards to

prediction and prevention of disease outbreaks caused by the West Nile Virus. As per current

evidence, despite a few rare cases, individuals generally demonstrate immunity to this viral

infection after recovery. For this reason, a simple compartment based SIR model with a

differential, non-linear equation has been considered for the purpose of predicting disease

outbreaks. For the purpose of future predictions with regards to a cure such as a vaccine, as per

current evidence, a revised SEIS model with an exponential formula can be considered. To

conclude, in addition to advanced treatments there is also a need for the development of

comprehensive predictive models examining disease transmission associated with human to

human infection disseminations via organs, blood or the placenta.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

References

Andayani, P., Azmi, R. D., & Sari, L. R. (2018). Comparing Vector-host and SEIR models for

Zika Virus Transmission. The Journal of Experimental Life Science, 8(3), 161-164.

Bhowmick, S., Gethmann, J., Conraths, F. J., Sokolov, I. M., & Lentz, H. H. (2020). Locally

temperature-driven mathematical model of West Nile virus spread in Germany. Journal

of Theoretical Biology, 488, 110117.

Chen, J., Huang, J., Beier, J. C., Cantrell, R. S., Cosner, C., Fuller, D. O., ... & Ruan, S. (2016).

Modeling and control of local outbreaks of West Nile virus in the United States. Discrete

& Continuous Dynamical Systems-B, 21(8), 2423-2449.

Krause, K., Azouz, F., Nakano, E., Nerurkar, V. R., & Kumar, M. (2019). Deletion of pregnancy

zone protein and murinoglobulin-1 restricts the pathogenesis of West Nile virus infection

in mice. Frontiers in microbiology, 10.

Liu, J., Zhang, T., & Chen, Q. (2020). A Periodic West Nile Virus Transmission Model with

Stage-Structured Host Population. Complexity, 2020.

Mallya, S., Sander, B., Roy-Gagnon, M. H., Taljaard, M., Jolly, A., & Kulkarni, M. A. (2018).

Factors associated with human West Nile virus infection in Ontario: a generalized linear

mixed modelling approach. BMC infectious diseases, 18(1), 141.

Moirano, G., Gasparrini, A., Acquaotta, F., Fratianni, S., Merletti, F., Maule, M., & Richiardi, L.

(2018). West Nile virus infection in Northern Italy: case-crossover study on the short-

term effect of climatic parameters. Environmental research, 167, 544-549.

References

Andayani, P., Azmi, R. D., & Sari, L. R. (2018). Comparing Vector-host and SEIR models for

Zika Virus Transmission. The Journal of Experimental Life Science, 8(3), 161-164.

Bhowmick, S., Gethmann, J., Conraths, F. J., Sokolov, I. M., & Lentz, H. H. (2020). Locally

temperature-driven mathematical model of West Nile virus spread in Germany. Journal

of Theoretical Biology, 488, 110117.

Chen, J., Huang, J., Beier, J. C., Cantrell, R. S., Cosner, C., Fuller, D. O., ... & Ruan, S. (2016).

Modeling and control of local outbreaks of West Nile virus in the United States. Discrete

& Continuous Dynamical Systems-B, 21(8), 2423-2449.

Krause, K., Azouz, F., Nakano, E., Nerurkar, V. R., & Kumar, M. (2019). Deletion of pregnancy

zone protein and murinoglobulin-1 restricts the pathogenesis of West Nile virus infection

in mice. Frontiers in microbiology, 10.

Liu, J., Zhang, T., & Chen, Q. (2020). A Periodic West Nile Virus Transmission Model with

Stage-Structured Host Population. Complexity, 2020.

Mallya, S., Sander, B., Roy-Gagnon, M. H., Taljaard, M., Jolly, A., & Kulkarni, M. A. (2018).

Factors associated with human West Nile virus infection in Ontario: a generalized linear

mixed modelling approach. BMC infectious diseases, 18(1), 141.

Moirano, G., Gasparrini, A., Acquaotta, F., Fratianni, S., Merletti, F., Maule, M., & Richiardi, L.

(2018). West Nile virus infection in Northern Italy: case-crossover study on the short-

term effect of climatic parameters. Environmental research, 167, 544-549.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

Montgomery, R. R. (2017). Age‐related alterations in immune responses to West Nile virus

infection. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 187(1), 26-34.

Nasrinpour, H. R., Friesen, M. R., & McLeod, R. D. (2017). Modelling of West Nile Virus: A

Survey. CMBES Proceedings, 40.

Parkash, V., Woods, K., Kafetzopoulou, L., Osborne, J., Aarons, E., & Cartwright, K. (2019).

West Nile Virus Infection in Travelers Returning to United Kingdom from South

Africa. Emerging infectious diseases, 25(2), 367.

Ramos da Silva, S., & Gao, S. J. (2016). Zika virus: an update on epidemiology, pathology,

molecular biology, and animal model. Journal of medical virology, 88(8), 1291-1296.

Ronca, S. E., Murray, K. O., & Nolan, M. S. (2019). Cumulative incidence of West Nile virus

infection, continental United States, 1999–2016. Emerging infectious diseases, 25(2),

325.

Sinigaglia, A., Pacenti, M., Martello, T., Pagni, S., Franchin, E., & Barzon, L. (2019). West Nile

virus infection in individuals with pre-existing Usutu virus immunity, northern Italy,

2018. Eurosurveillance, 24(21).

Tisoncik-Go, J., & Gale Jr, M. (2019). Microglia in Memory Decline from Zika Virus and West

Nile Virus Infection. Trends in neurosciences, 42(11), 757-759.

WHO. (2017). West Nile virus. Retrieved 5 February 2020, from https://www.who.int/news-

room/fact-sheets/detail/west-nile-virus.

Williamson, P. C., Custer, B., Biggerstaff, B. J., Lanciotti, R. S., Sayers, M. H., Eason, S. J., ... &

Busch, M. P. (2017). Incidence of West Nile virus infection in the Dallas–Fort Worth

Montgomery, R. R. (2017). Age‐related alterations in immune responses to West Nile virus

infection. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 187(1), 26-34.

Nasrinpour, H. R., Friesen, M. R., & McLeod, R. D. (2017). Modelling of West Nile Virus: A

Survey. CMBES Proceedings, 40.

Parkash, V., Woods, K., Kafetzopoulou, L., Osborne, J., Aarons, E., & Cartwright, K. (2019).

West Nile Virus Infection in Travelers Returning to United Kingdom from South

Africa. Emerging infectious diseases, 25(2), 367.

Ramos da Silva, S., & Gao, S. J. (2016). Zika virus: an update on epidemiology, pathology,

molecular biology, and animal model. Journal of medical virology, 88(8), 1291-1296.

Ronca, S. E., Murray, K. O., & Nolan, M. S. (2019). Cumulative incidence of West Nile virus

infection, continental United States, 1999–2016. Emerging infectious diseases, 25(2),

325.

Sinigaglia, A., Pacenti, M., Martello, T., Pagni, S., Franchin, E., & Barzon, L. (2019). West Nile

virus infection in individuals with pre-existing Usutu virus immunity, northern Italy,

2018. Eurosurveillance, 24(21).

Tisoncik-Go, J., & Gale Jr, M. (2019). Microglia in Memory Decline from Zika Virus and West

Nile Virus Infection. Trends in neurosciences, 42(11), 757-759.

WHO. (2017). West Nile virus. Retrieved 5 February 2020, from https://www.who.int/news-

room/fact-sheets/detail/west-nile-virus.

Williamson, P. C., Custer, B., Biggerstaff, B. J., Lanciotti, R. S., Sayers, M. H., Eason, S. J., ... &

Busch, M. P. (2017). Incidence of West Nile virus infection in the Dallas–Fort Worth

11DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY: DISEASE OUTBREAK MODELLING

metropolitan area during the 2012 epidemic. Epidemiology & Infection, 145(12), 2536-

2544.

metropolitan area during the 2012 epidemic. Epidemiology & Infection, 145(12), 2536-

2544.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.