In-Depth Case Study: Pathophysiology of DVT and Testis - Conditions

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/30

|20

|4236

|358

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study delves into the pathophysiology of lower limb Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and testis conditions, specifically epididymitis and hydrocele. For DVT, it explains Virchow's triad (venous stasis, injury/trauma, and hypercoagulability) and the role of coagulation factors, endothelial injuries, and tissue factor release in clot formation. It also describes the sonographic appearance of acute and chronic DVT using venous duplex ultrasound. Regarding epididymitis, the study discusses its causes (bacterial/fungal infections, STDs, UTIs), categorization (acute/chronic), and the ultrasonography findings such as enlarged, vascularized epididymis. For hydrocele, the study explores the accumulation of fluid around the testicles due to diseases, trauma, or lymphatic system disruption, and it discusses congenital vs. acquired hydroceles, potential complications, and treatment options. Sonographic appearance is also discussed.

Pathophysiology 1

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

By

Name of the Class

Professor

Name of the School

Date

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

By

Name of the Class

Professor

Name of the School

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Pathophysiology 2

Lower Limb DVT (Deep Venous Thrombosis)

Pathophysiology

Deep venous thrombosis is caused by blood clots in the veins, specifically those found in

the legs. When blood clots are dislodged from a vein, they move through blood and eventually

find their way to the lungs, causing a condition known as a pulmonary embolism (Thompson

2015). Deep vein thromboses together with pulmonary embolisms make up a condition referred

to as venous thrombo-embolism (VTE) (Stone et al. 2017). The main function of clotting is to

minimize blood clots through a process known as coagulation. When something goes wrong

during the coagulation process, there is a potential for clot build up which leads to thrombosis

(Blann 2015). Blood clots or thrombosis are caused by poor blood circulation, varicose veins,

congestive heart failure, pregnancy, an injury to the vein, hormone therapy or susceptibility to

blood clots (Thompson 2015).

The pathophysiology of deep vein thrombosis can trace its background to the work of a

German doctor known as Rudolf Virchow. He identified three factors, known as Virchow’s triad,

which caused blood clots to develop within the deep veins and these factors were venous stasis,

injury/trauma and hypercoagulability (Rumbaut & Thiagarajan 2010). Venous stasis is seen to

play the biggest role in the formation of blood clots within veins especially in post-surgical

patients and those who have experienced vascular trauma (Behravesh et al. 2017). While stasis

can lead to the development of blood clots, research is still unclear on whether stasis alone can

cause enough blood clot formation (Rumbaut & Thiagarajan 2010).

Endothelial injuries have been proposed by researchers to cause thrombosis if they are

occur in the deep vein valve pockets. The endothelial injuries trigger an increase in P-selectin

Lower Limb DVT (Deep Venous Thrombosis)

Pathophysiology

Deep venous thrombosis is caused by blood clots in the veins, specifically those found in

the legs. When blood clots are dislodged from a vein, they move through blood and eventually

find their way to the lungs, causing a condition known as a pulmonary embolism (Thompson

2015). Deep vein thromboses together with pulmonary embolisms make up a condition referred

to as venous thrombo-embolism (VTE) (Stone et al. 2017). The main function of clotting is to

minimize blood clots through a process known as coagulation. When something goes wrong

during the coagulation process, there is a potential for clot build up which leads to thrombosis

(Blann 2015). Blood clots or thrombosis are caused by poor blood circulation, varicose veins,

congestive heart failure, pregnancy, an injury to the vein, hormone therapy or susceptibility to

blood clots (Thompson 2015).

The pathophysiology of deep vein thrombosis can trace its background to the work of a

German doctor known as Rudolf Virchow. He identified three factors, known as Virchow’s triad,

which caused blood clots to develop within the deep veins and these factors were venous stasis,

injury/trauma and hypercoagulability (Rumbaut & Thiagarajan 2010). Venous stasis is seen to

play the biggest role in the formation of blood clots within veins especially in post-surgical

patients and those who have experienced vascular trauma (Behravesh et al. 2017). While stasis

can lead to the development of blood clots, research is still unclear on whether stasis alone can

cause enough blood clot formation (Rumbaut & Thiagarajan 2010).

Endothelial injuries have been proposed by researchers to cause thrombosis if they are

occur in the deep vein valve pockets. The endothelial injuries trigger an increase in P-selectin

Pathophysiology 3

production which in turn increases production of platelet-endothelial and platelet-leukocyte-

endothelial cells that create blood clots (Rumbaut & Thiagarajan 2010). Endothelial P-selectin

contributes to inflammatory mechanisms that are localized and various inflammatory stimuli

which lead to deep vein thrombosis. Hypercoagulability refers to conditions that exist in a

procoagulant state because of hemostatic imbalances within the body that lead to thrombosis.

Coagulation factors play an important role in venous thrombosis when they are activated because

they concentrate in areas that have a reduce blood flow like the valve pockets found in the lower

limbs (Rumbaut & Thiagarajan 2010).

Defects in the mechanisms that promote anticoagulation such as antithrombin deficiency

or fibrin deposits play a significant role in causing deep vein thrombosis (Rumbaut &

Thiagarajan 2010). In addition, the initiation of a coagulation cascade caused by the release of

tissue factor due to tumors or tissue damage increases the risk of a person developing DVT

(Behravesh et al. 2017). Thrombosis mostly occurs in the deep vein valve pockets of the lower

legs in areas that have decreased blood flow.

These valves usually help to promote blood flow but they also have a potential to be sites

for venous stasis and hypoxia (Stone et al. 2017). Blood clots are caused by tissue factor which

leads to the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin and this process is later followed by fibrin

deposition. Prothrombin, produced in the liver, is a protein essential in blood clotting while

thrombin converts fibrinogen into fibrin during blood coagulation (Blann 2015).

Sonographic Appearance

A venous duplex ultrasound of the lower limbs makes use of two components to detect

deep vein thrombosis and these are a Doppler imaging of the leg using spectral waveform

production which in turn increases production of platelet-endothelial and platelet-leukocyte-

endothelial cells that create blood clots (Rumbaut & Thiagarajan 2010). Endothelial P-selectin

contributes to inflammatory mechanisms that are localized and various inflammatory stimuli

which lead to deep vein thrombosis. Hypercoagulability refers to conditions that exist in a

procoagulant state because of hemostatic imbalances within the body that lead to thrombosis.

Coagulation factors play an important role in venous thrombosis when they are activated because

they concentrate in areas that have a reduce blood flow like the valve pockets found in the lower

limbs (Rumbaut & Thiagarajan 2010).

Defects in the mechanisms that promote anticoagulation such as antithrombin deficiency

or fibrin deposits play a significant role in causing deep vein thrombosis (Rumbaut &

Thiagarajan 2010). In addition, the initiation of a coagulation cascade caused by the release of

tissue factor due to tumors or tissue damage increases the risk of a person developing DVT

(Behravesh et al. 2017). Thrombosis mostly occurs in the deep vein valve pockets of the lower

legs in areas that have decreased blood flow.

These valves usually help to promote blood flow but they also have a potential to be sites

for venous stasis and hypoxia (Stone et al. 2017). Blood clots are caused by tissue factor which

leads to the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin and this process is later followed by fibrin

deposition. Prothrombin, produced in the liver, is a protein essential in blood clotting while

thrombin converts fibrinogen into fibrin during blood coagulation (Blann 2015).

Sonographic Appearance

A venous duplex ultrasound of the lower limbs makes use of two components to detect

deep vein thrombosis and these are a Doppler imaging of the leg using spectral waveform

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Pathophysiology 4

analysis and color-flow imaging or compression techniques using a transducer that makes use of

B-mode or gray-scale images. The main criterion for diagnosing deep vein thrombosis is the

inability to compress the vein. The secondary criteria for diagnosing the condition is the presence

of a thrombus in the vein, distention within the veins, the lack of a Doppler spectral signal and no

response to valsalva maneuvers (Karande et al. 2016). The Venous duplex ultrasound can also

detect whether the thrombus is acute or chronic. For an acute diagnosis, there is venous

distention with partial or no compression of the vein while for a chronic diagnosis, there is no

compression and the vein has an irregular shape with blood clots present on the walls (Karande

et al. 2016).

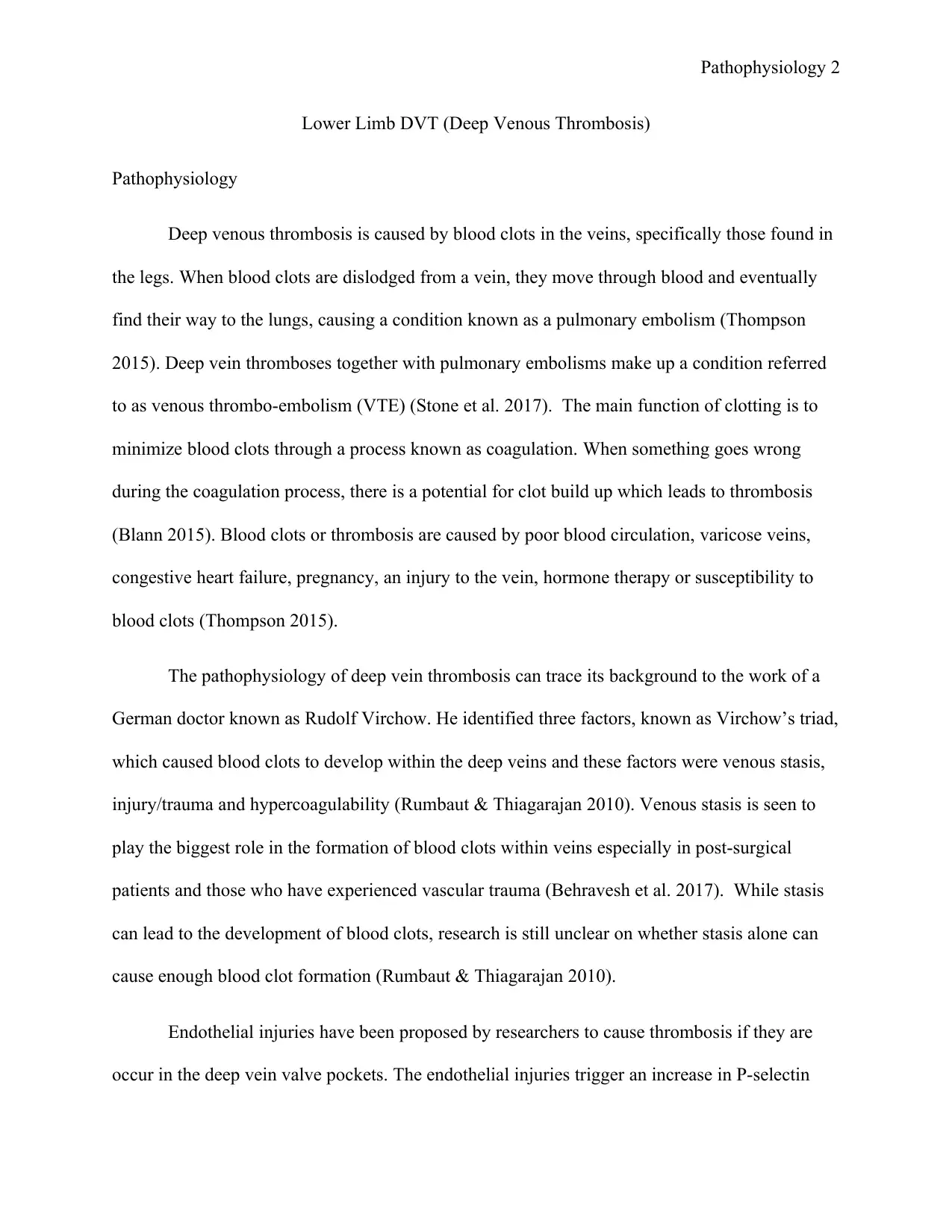

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has developed guidelines that can be used to

diagnose deep vein thrombosis through the use of ultrasound. These guidelines are compression

should be done in the lower extremity when using the ultrasound, the color and spectral Doppler

should show there is adequate blood flow in the vein and also phasicity (Karande et al. 2016).

The images below show acute DVT. Image A and B are gray-scale or B-mode ultrasound images

of the left femoral vein with the arrow pointing to an enlarged vein that has no compression.

Image C is a color image generated by a spectral Doppler showing a lack of flow within the vein

(Karande et al. 2016).

analysis and color-flow imaging or compression techniques using a transducer that makes use of

B-mode or gray-scale images. The main criterion for diagnosing deep vein thrombosis is the

inability to compress the vein. The secondary criteria for diagnosing the condition is the presence

of a thrombus in the vein, distention within the veins, the lack of a Doppler spectral signal and no

response to valsalva maneuvers (Karande et al. 2016). The Venous duplex ultrasound can also

detect whether the thrombus is acute or chronic. For an acute diagnosis, there is venous

distention with partial or no compression of the vein while for a chronic diagnosis, there is no

compression and the vein has an irregular shape with blood clots present on the walls (Karande

et al. 2016).

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has developed guidelines that can be used to

diagnose deep vein thrombosis through the use of ultrasound. These guidelines are compression

should be done in the lower extremity when using the ultrasound, the color and spectral Doppler

should show there is adequate blood flow in the vein and also phasicity (Karande et al. 2016).

The images below show acute DVT. Image A and B are gray-scale or B-mode ultrasound images

of the left femoral vein with the arrow pointing to an enlarged vein that has no compression.

Image C is a color image generated by a spectral Doppler showing a lack of flow within the vein

(Karande et al. 2016).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Pathophysiology 5

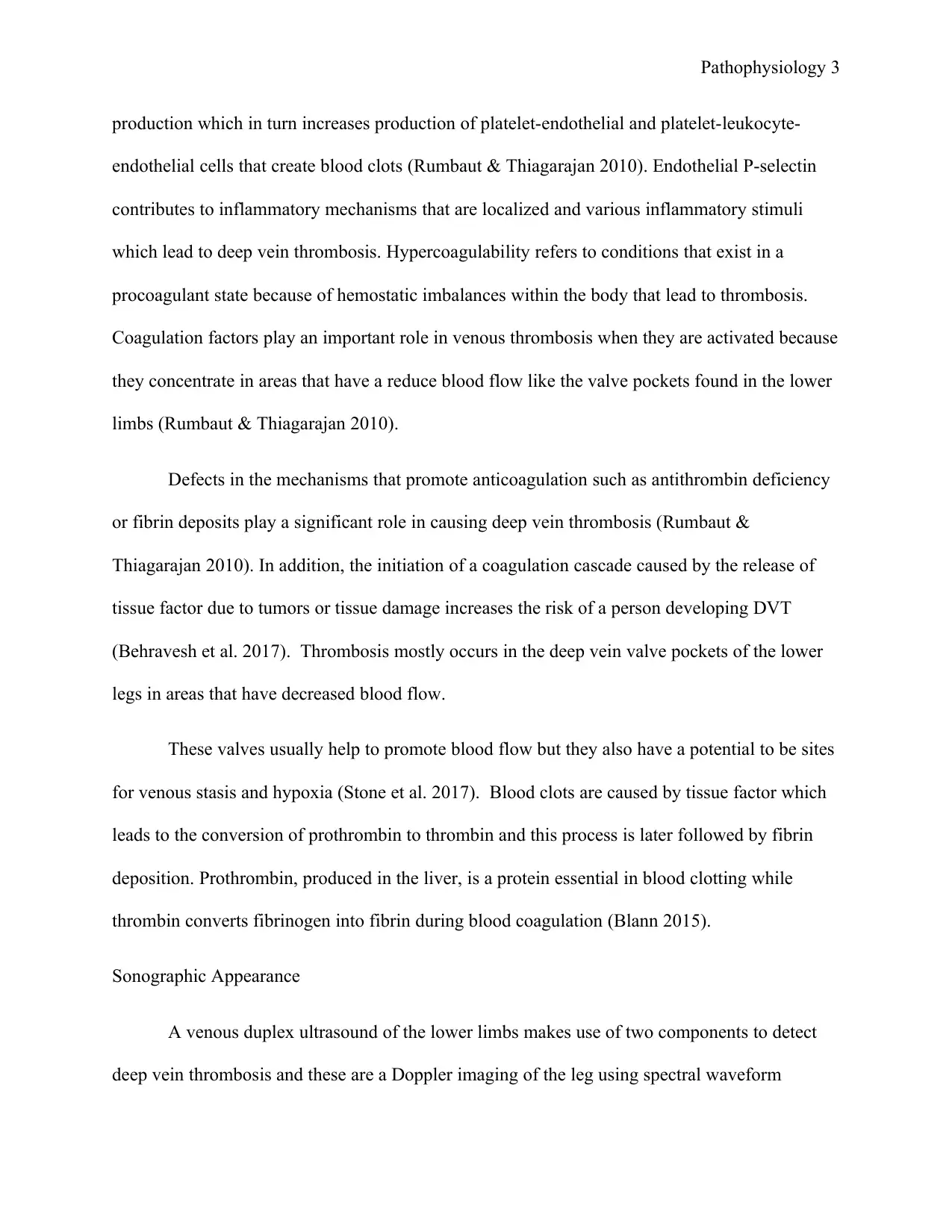

The images below depict chronic DVT in the right popliteal vein. Images A and B are a

gray scale or B-mode ultrasound imaging of vein depicting compression of the lumen and an

echogenic wall as shown by the arrow. The color image is generated from the spectral Doppler

and it shows there is flow within the linear area of echogenic material (Karande et al. 2016).

The images below depict chronic DVT in the right popliteal vein. Images A and B are a

gray scale or B-mode ultrasound imaging of vein depicting compression of the lumen and an

echogenic wall as shown by the arrow. The color image is generated from the spectral Doppler

and it shows there is flow within the linear area of echogenic material (Karande et al. 2016).

Pathophysiology 6

References

Behravesh, S, Hoang, P, Nanda, A, Wallace, A, Sheth, RA, Deipolyi, AR, Memic, A, Naidu, S &

Oklu, R 2017, ‘Pathogenesis of thromboembolism and endovascular management,’ Thrombosis,

pp. 1-13, viewed 2 December 2018,

<https://www.hindawi.com/journals/thrombosis/2017/3039713/>

Blann, A 2015, Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a guide for practitioners. M&K

Publishing, Glasgow, viewed 2 December 2018, <https://books.google.co.ke/books?

id=aVxuBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=pathophysiology+of+dvt&hl=en&sa=X&ved=

0ahUKEwiQ46T45oDfAhX0oXEKHYdgAtoQ6AEILTAB#v=onepage&q=pathophysiology

%20of%20dvt&f=false>

Karande, GY, Hedgire, SS, Sanchez, Y, Baliyan, V, Mishra, V, Ganguli, S & Prabhakar, AM

2016, ‘Advanced imaging in acute and chronic deep vein thrombosis,’ Cardiovascular Diagnosis

and Therapy, vol. 6, no.6, pp.493-507, viewed 11 December 2018,

<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5220209/>

Rumbaut, RE & Thiagarajan, P 2010, Arterial, venous and microvascular

hemostasis/thrombosis, Morgan and Claypool Life Sciences, San Rafael, CA, viewed 2

December 2018, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53453/>

Stone, J, Hangge, P, Albadawi, H, Wallace, A, Shamoun, F, Knuttien, MG, Naidu, S & Oklu, R

2017, ‘Deep vein thrombosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and medical management,’

Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy, vol. 7, viewed 2 December 2018,

<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5778510/>

References

Behravesh, S, Hoang, P, Nanda, A, Wallace, A, Sheth, RA, Deipolyi, AR, Memic, A, Naidu, S &

Oklu, R 2017, ‘Pathogenesis of thromboembolism and endovascular management,’ Thrombosis,

pp. 1-13, viewed 2 December 2018,

<https://www.hindawi.com/journals/thrombosis/2017/3039713/>

Blann, A 2015, Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a guide for practitioners. M&K

Publishing, Glasgow, viewed 2 December 2018, <https://books.google.co.ke/books?

id=aVxuBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=pathophysiology+of+dvt&hl=en&sa=X&ved=

0ahUKEwiQ46T45oDfAhX0oXEKHYdgAtoQ6AEILTAB#v=onepage&q=pathophysiology

%20of%20dvt&f=false>

Karande, GY, Hedgire, SS, Sanchez, Y, Baliyan, V, Mishra, V, Ganguli, S & Prabhakar, AM

2016, ‘Advanced imaging in acute and chronic deep vein thrombosis,’ Cardiovascular Diagnosis

and Therapy, vol. 6, no.6, pp.493-507, viewed 11 December 2018,

<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5220209/>

Rumbaut, RE & Thiagarajan, P 2010, Arterial, venous and microvascular

hemostasis/thrombosis, Morgan and Claypool Life Sciences, San Rafael, CA, viewed 2

December 2018, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53453/>

Stone, J, Hangge, P, Albadawi, H, Wallace, A, Shamoun, F, Knuttien, MG, Naidu, S & Oklu, R

2017, ‘Deep vein thrombosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and medical management,’

Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy, vol. 7, viewed 2 December 2018,

<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5778510/>

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Pathophysiology 7

Thompson, AE 2015, ‘Deep vein thrombosis,’ JAMA, vol. 313, no. 20, viewed 2 December

2018, <https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2297171>

Thompson, AE 2015, ‘Deep vein thrombosis,’ JAMA, vol. 313, no. 20, viewed 2 December

2018, <https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2297171>

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Pathophysiology 8

Testis: Epididymitis/Hydrocele

Pathophysiology

Epididymitis is the swelling and inflammation of the epididymis as a result of a bacterial

or fungal infection. If the infection is not treated, it can spread to the testicles, leading to a

condition known as epididymo-orchitis. Currently there is not a lot of research to show the true

prevalence of the disease. Data from the US shows that 600,000 people had epididymitis in 2002

with men between 18-35 years being the most infected (Taylor 2015). Epididymitis infections

can be sexually transmitted or urinary tract infections even though UTIs are not common in men.

UTIs are more likely to be the cause if the male has an indwelling urinary catheter, surgery in

any of the male reproductive organs or an enlarged prostate gland (NHS 2018).

Epididymitis can be categorized as acute or chronic where acute is characterized by pain

and swelling that lasts for less than six weeks. If no treatment is initiated, the infection can

spread to the testis within a matter of days leading to epididymo-orchitis (Cek, Sturdza & Pilatz

2017). According to Campbell’s research in 1927, acute infections of the epididymis were

caused by the ascension of microorganisms into the urethra. Another study found that patients

with urinary catheters had bacterial pathogens that led to infections (Cek, Sturdza & Pilatz 2017).

Chronic epididymitis occurs between six weeks to three months where the patient has pain and

discomfort in the epididymis. The factors that lead to chronic infections include an obstruction in

the urethra or an infection (Cek, Sturdza & Pilatz 2017).

Infections caused by STD begin when a bacterium is introduced to the genitourinary tract

through sexual intercourse where it then migrates to the epididymis. UTI infections are caused

when there is an obstruction in the flow of urine within the urinary tract, leading to an

Testis: Epididymitis/Hydrocele

Pathophysiology

Epididymitis is the swelling and inflammation of the epididymis as a result of a bacterial

or fungal infection. If the infection is not treated, it can spread to the testicles, leading to a

condition known as epididymo-orchitis. Currently there is not a lot of research to show the true

prevalence of the disease. Data from the US shows that 600,000 people had epididymitis in 2002

with men between 18-35 years being the most infected (Taylor 2015). Epididymitis infections

can be sexually transmitted or urinary tract infections even though UTIs are not common in men.

UTIs are more likely to be the cause if the male has an indwelling urinary catheter, surgery in

any of the male reproductive organs or an enlarged prostate gland (NHS 2018).

Epididymitis can be categorized as acute or chronic where acute is characterized by pain

and swelling that lasts for less than six weeks. If no treatment is initiated, the infection can

spread to the testis within a matter of days leading to epididymo-orchitis (Cek, Sturdza & Pilatz

2017). According to Campbell’s research in 1927, acute infections of the epididymis were

caused by the ascension of microorganisms into the urethra. Another study found that patients

with urinary catheters had bacterial pathogens that led to infections (Cek, Sturdza & Pilatz 2017).

Chronic epididymitis occurs between six weeks to three months where the patient has pain and

discomfort in the epididymis. The factors that lead to chronic infections include an obstruction in

the urethra or an infection (Cek, Sturdza & Pilatz 2017).

Infections caused by STD begin when a bacterium is introduced to the genitourinary tract

through sexual intercourse where it then migrates to the epididymis. UTI infections are caused

when there is an obstruction in the flow of urine within the urinary tract, leading to an

Pathophysiology 9

inflammation of the epididymis. This happens in patients who have indwelling catheters that

have been in place for a long time (Rupp & Leslie 2018).

A hydrocele occurs when there is an accumulation of fluid in the membrane that covers

the testicles. This fluid build-up is caused by severe diseases, trauma or imbalances in the

secretion and absorption of fluids in the tunica vaginalis (Dagur et al. 2017). Hydroceles are

usually painless but they can lead to complications if they are not treated. The most common

cause of hydroceles is a disruption within the lymphatic system. Laparoscopic procedures like

varicocelectomies have the potential to disrupt drainage within the testicles leading to hydrocele

complications. Imbalances in the input and output of lymphatic tissue covering the scrotum are

also another cause of hydroceles (Dagur et al. 2017).

Hydroceles can be congenital which are commonly found in pediatric patients and are

caused when the tunica vaginalis closes, leading to spermatic cord hydroceles. Acquired

hydroceles are commonly found in adult males and they are caused by increased secretion of

fluids, reaction of the hydrocele to epididymitis, trauma and reduced lymphatic flow (Wright et

al. 2012). They can also occur in patients who have undergone kidney transplants because of

disruptions within the lymphatic system. The disruption causes hydroceles because the

absorption of lymphatic fluid has been negatively affected despite the normal secretion of the

fluid (Dagur et al. 2017).

If hydroceles are not treated, they can cause low sperm production due to the increased

pressure within the testis. Both benign and malignant tumors can also be hidden by the hydrocele

because the built-up fluid makes it difficult to detect underlying problems. They can also cause

pressure to sensitive tissues within the body such as the testis (Dagur et al. 2017). The pressure

from hydroceles can be very severe, surpassing that of blood vessels in the scrotum and this

inflammation of the epididymis. This happens in patients who have indwelling catheters that

have been in place for a long time (Rupp & Leslie 2018).

A hydrocele occurs when there is an accumulation of fluid in the membrane that covers

the testicles. This fluid build-up is caused by severe diseases, trauma or imbalances in the

secretion and absorption of fluids in the tunica vaginalis (Dagur et al. 2017). Hydroceles are

usually painless but they can lead to complications if they are not treated. The most common

cause of hydroceles is a disruption within the lymphatic system. Laparoscopic procedures like

varicocelectomies have the potential to disrupt drainage within the testicles leading to hydrocele

complications. Imbalances in the input and output of lymphatic tissue covering the scrotum are

also another cause of hydroceles (Dagur et al. 2017).

Hydroceles can be congenital which are commonly found in pediatric patients and are

caused when the tunica vaginalis closes, leading to spermatic cord hydroceles. Acquired

hydroceles are commonly found in adult males and they are caused by increased secretion of

fluids, reaction of the hydrocele to epididymitis, trauma and reduced lymphatic flow (Wright et

al. 2012). They can also occur in patients who have undergone kidney transplants because of

disruptions within the lymphatic system. The disruption causes hydroceles because the

absorption of lymphatic fluid has been negatively affected despite the normal secretion of the

fluid (Dagur et al. 2017).

If hydroceles are not treated, they can cause low sperm production due to the increased

pressure within the testis. Both benign and malignant tumors can also be hidden by the hydrocele

because the built-up fluid makes it difficult to detect underlying problems. They can also cause

pressure to sensitive tissues within the body such as the testis (Dagur et al. 2017). The pressure

from hydroceles can be very severe, surpassing that of blood vessels in the scrotum and this

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Pathophysiology 10

becomes a leading cause of ischemia in the testis. Hydroceles can be treated through invasive or

non-invasive surgery. Hydrocelectomy is an invasive surgery for hydroceles that are particularly

large and persistent while aspiration and sclerotherapy are non-invasive techniques that are used

to treat hydroceles that are 750ml in size (Dagur et al. 2017).

Sonographic Appearance

Epididymitis is detected through the use of ultrasonography which is a noninvasive

procedure for diagnosing abnormalities within the scrotum. A linear array transducer that uses a

frequency of 12 to 17 MHz is used to provide grayscale and color Doppler images of the

testicles, scrotum and epididymis (Kuhn et al. 2016). The scanning of the epididymis involves

taking longitudinal imaging of the lateral, mid and medial parts of the head, body and tail of the

epididymis. Transverse images include those of the upper, middle and lower parts of the

epididymis (Kuhn et al. 2016).

The color Doppler imaging for the epididymis should be done bilaterally to assess the

capsular, centripetal arteries and check for a reduction in velocity of venous flow. Arterial and

venous flow on both sides should also be assessed using spectral waveforms (Kuhn et al. 2016).

Ultrasonography results for diagnosing epididymitis show the presence of an enlarged and highly

vascularized epididymis with a hypoechoic appearance. The color Doppler has a sensitivity of

100 percent and is an effective tool in detecting acute inflammations as well as diagnosing

epididymitis. The formation of abscess is a complication found in acute epididymitis and it

appears as a hypoechoic area that is avascular under sonography (Kuhn et al. 2016).

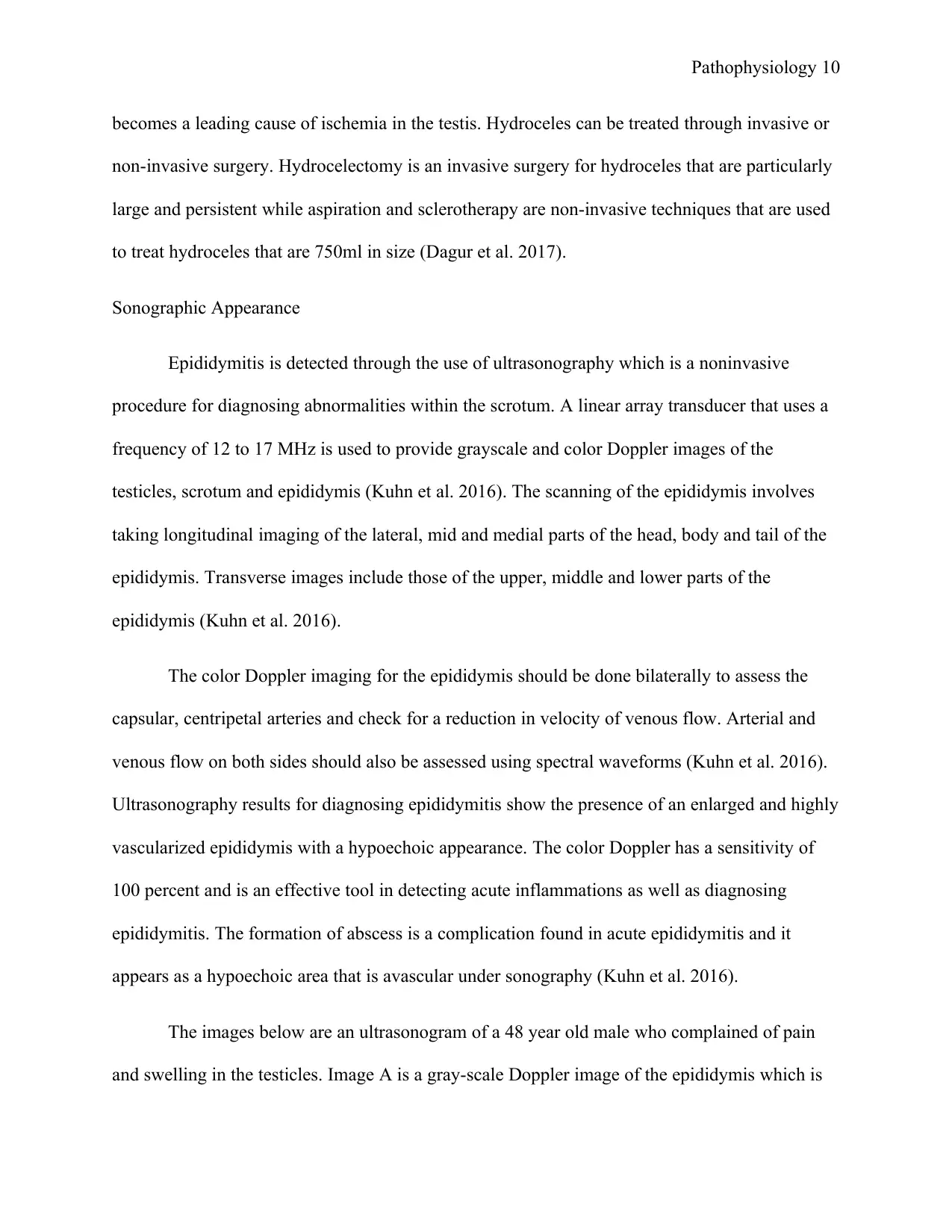

The images below are an ultrasonogram of a 48 year old male who complained of pain

and swelling in the testicles. Image A is a gray-scale Doppler image of the epididymis which is

becomes a leading cause of ischemia in the testis. Hydroceles can be treated through invasive or

non-invasive surgery. Hydrocelectomy is an invasive surgery for hydroceles that are particularly

large and persistent while aspiration and sclerotherapy are non-invasive techniques that are used

to treat hydroceles that are 750ml in size (Dagur et al. 2017).

Sonographic Appearance

Epididymitis is detected through the use of ultrasonography which is a noninvasive

procedure for diagnosing abnormalities within the scrotum. A linear array transducer that uses a

frequency of 12 to 17 MHz is used to provide grayscale and color Doppler images of the

testicles, scrotum and epididymis (Kuhn et al. 2016). The scanning of the epididymis involves

taking longitudinal imaging of the lateral, mid and medial parts of the head, body and tail of the

epididymis. Transverse images include those of the upper, middle and lower parts of the

epididymis (Kuhn et al. 2016).

The color Doppler imaging for the epididymis should be done bilaterally to assess the

capsular, centripetal arteries and check for a reduction in velocity of venous flow. Arterial and

venous flow on both sides should also be assessed using spectral waveforms (Kuhn et al. 2016).

Ultrasonography results for diagnosing epididymitis show the presence of an enlarged and highly

vascularized epididymis with a hypoechoic appearance. The color Doppler has a sensitivity of

100 percent and is an effective tool in detecting acute inflammations as well as diagnosing

epididymitis. The formation of abscess is a complication found in acute epididymitis and it

appears as a hypoechoic area that is avascular under sonography (Kuhn et al. 2016).

The images below are an ultrasonogram of a 48 year old male who complained of pain

and swelling in the testicles. Image A is a gray-scale Doppler image of the epididymis which is

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Pathophysiology 11

enlarged (marked by the asterisk) and a right testicle that is also enlarged with edema. Image B is

a color image which demonstrates increased vascularity consistent with epididymo-orchitis

(Kuhn et al. 2016).

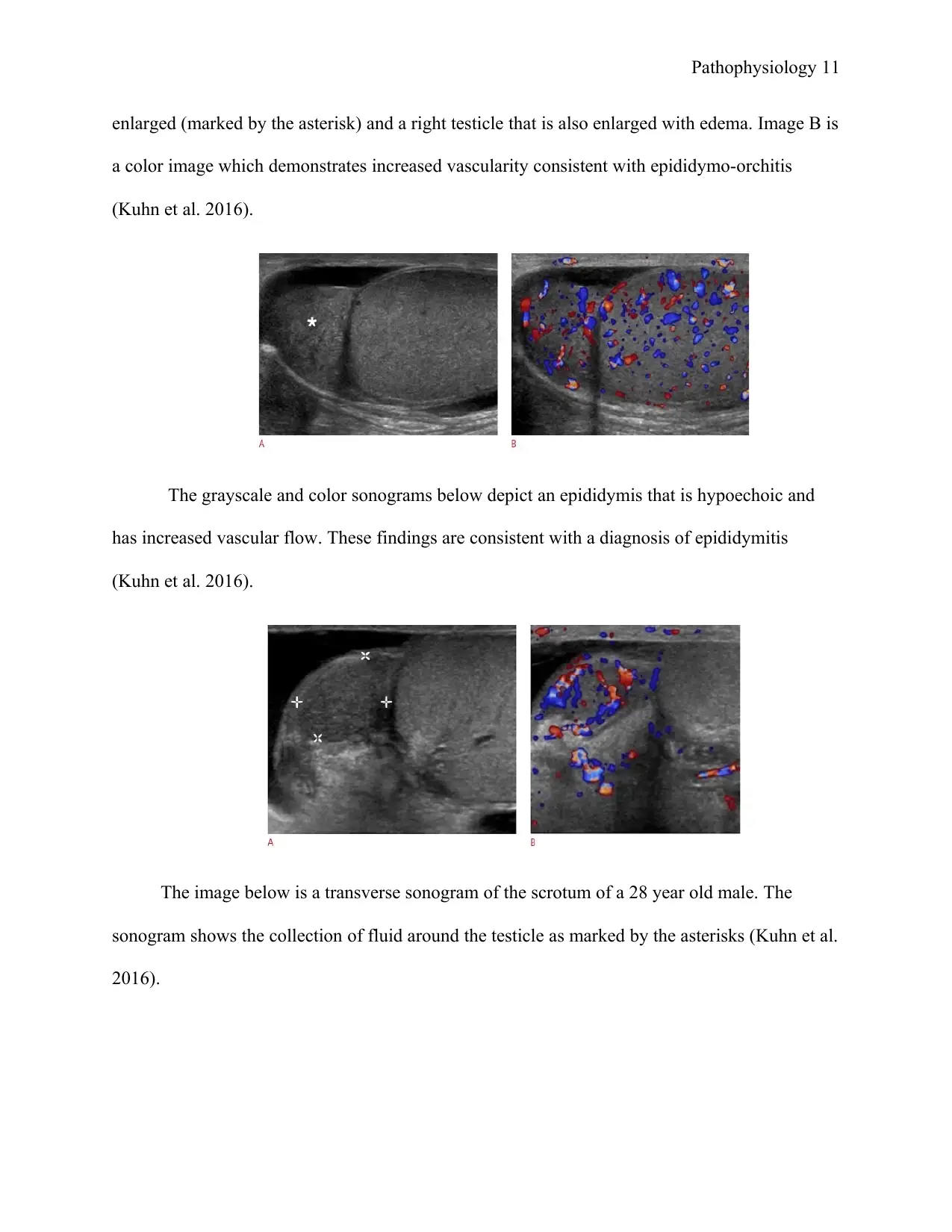

The grayscale and color sonograms below depict an epididymis that is hypoechoic and

has increased vascular flow. These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of epididymitis

(Kuhn et al. 2016).

The image below is a transverse sonogram of the scrotum of a 28 year old male. The

sonogram shows the collection of fluid around the testicle as marked by the asterisks (Kuhn et al.

2016).

enlarged (marked by the asterisk) and a right testicle that is also enlarged with edema. Image B is

a color image which demonstrates increased vascularity consistent with epididymo-orchitis

(Kuhn et al. 2016).

The grayscale and color sonograms below depict an epididymis that is hypoechoic and

has increased vascular flow. These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of epididymitis

(Kuhn et al. 2016).

The image below is a transverse sonogram of the scrotum of a 28 year old male. The

sonogram shows the collection of fluid around the testicle as marked by the asterisks (Kuhn et al.

2016).

Pathophysiology 12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 20

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.