Review of Recent Advances in Pathogenic E. coli Adherence and Invasion

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/17

|12

|6941

|14

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on a NIH Public Access Author Manuscript, reviews recent progress in understanding the mechanisms of adherence and invasion used by pathogenic Escherichia coli (E. coli). The review focuses on intestinal and extra-intestinal E. coli strains, detailing how they colonize host cells. It covers enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), highlighting the specific adhesins and invasins each strain utilizes. The report examines the influence of dietary and environmental factors on colonization, including the impact of fiber, diet, and host signaling pathways. It also discusses the role of the type III secretion system (TTSS) and various virulence factors in E. coli pathogenesis. The review emphasizes the need for further research to develop new strategies to combat these infections, focusing on the complex interactions between the bacteria and host epithelial cells. The report is a valuable resource for understanding the complexities of E. coli infections and the ongoing efforts to mitigate their impact.

Recent advances in adherence and invasion of pathogenic

Escherichia coli

Anjana Kalita1,*, Jia Hu1,*, and Alfredo G. Torres1,2,†

1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston,

Texas, 77555, USA

2Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, 77555, USA

Abstract

Purpose of review—Colonization of the host epithelia by pathogenic Escherichia coli is

influenced by the ability of the bacteria to interact with host surfaces. Because the initial step of an

E. coli infection is to adhere, invade, and persist within host cells, some strategies used by

intestinal and extra-intestinal E. coli to infect host cell are presented.

Recent findings—This review highlights recent progress understanding how extra-intestinal

pathogenic E. coli strains express specific adhesins/invasins that allow colonization of the urinary

tract or the meninges, while intestinal E. coli strains are able to colonize different regions of the

intestinal tract using other specialized adhesins/invasins. Finally, evaluation of, different diets and

environmental conditions regulating the colonization of these pathogens is discussed.

Summary—Discovery of new interactions between pathogenic E. coli and the host epithelial

cells unravels the need of more mechanistic studies that can provide new clues in how to combat

these infections.

Keywords

enterohemorrhagic E. coli; enteropathogenic; enterotoxigenic; uropathogenic; enteroaggregative;

adherent invasive E. coli

Introduction

Escherichia coli are commonly found as part of the gut flora, where it is the predominant

aerobic organism, living in symbiosis with its vertebrate host. However, there are several

categories of E. coli strains that have acquired the ability to cause pathogenic processes in

the host (1). These E. coli strains can cause intestinal (enteritis, diarrhea, or dysentery), or.

extra-intestinal diseases (urinary tract infections, sepsis, or meningitis) (2, 3). To cause

infection, pathogenic E. coli interact with the mucosa, by either attaching to the epithelial

†Corresponding author: Alfredo G. Torres, PhD. UTMB, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Galveston, Texas, 77555

Phone (409) 747 0189; Fax (409) 747 6869; altorres@utmb.edu.

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

Published in final edited form as:

Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014 October ; 27(5): 459–464. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000092.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Escherichia coli

Anjana Kalita1,*, Jia Hu1,*, and Alfredo G. Torres1,2,†

1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston,

Texas, 77555, USA

2Department of Pathology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, 77555, USA

Abstract

Purpose of review—Colonization of the host epithelia by pathogenic Escherichia coli is

influenced by the ability of the bacteria to interact with host surfaces. Because the initial step of an

E. coli infection is to adhere, invade, and persist within host cells, some strategies used by

intestinal and extra-intestinal E. coli to infect host cell are presented.

Recent findings—This review highlights recent progress understanding how extra-intestinal

pathogenic E. coli strains express specific adhesins/invasins that allow colonization of the urinary

tract or the meninges, while intestinal E. coli strains are able to colonize different regions of the

intestinal tract using other specialized adhesins/invasins. Finally, evaluation of, different diets and

environmental conditions regulating the colonization of these pathogens is discussed.

Summary—Discovery of new interactions between pathogenic E. coli and the host epithelial

cells unravels the need of more mechanistic studies that can provide new clues in how to combat

these infections.

Keywords

enterohemorrhagic E. coli; enteropathogenic; enterotoxigenic; uropathogenic; enteroaggregative;

adherent invasive E. coli

Introduction

Escherichia coli are commonly found as part of the gut flora, where it is the predominant

aerobic organism, living in symbiosis with its vertebrate host. However, there are several

categories of E. coli strains that have acquired the ability to cause pathogenic processes in

the host (1). These E. coli strains can cause intestinal (enteritis, diarrhea, or dysentery), or.

extra-intestinal diseases (urinary tract infections, sepsis, or meningitis) (2, 3). To cause

infection, pathogenic E. coli interact with the mucosa, by either attaching to the epithelial

†Corresponding author: Alfredo G. Torres, PhD. UTMB, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Galveston, Texas, 77555

Phone (409) 747 0189; Fax (409) 747 6869; altorres@utmb.edu.

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

NIH Public Access

Author Manuscript

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

Published in final edited form as:

Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014 October ; 27(5): 459–464. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000092.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

cells and in some instances, invading the target host cells. Because bacterial adhesion and/or

invasion to/into host cells are the first step during infection, it is necessary to understand at a

molecular level the mechanisms mediating these initial interactions. This article focus on

reviewing recent progress on the understanding of the adhesion/invasion mechanisms used

by intestinal and extra-intestinal pathogenic E. coli during colonization of the host cells.

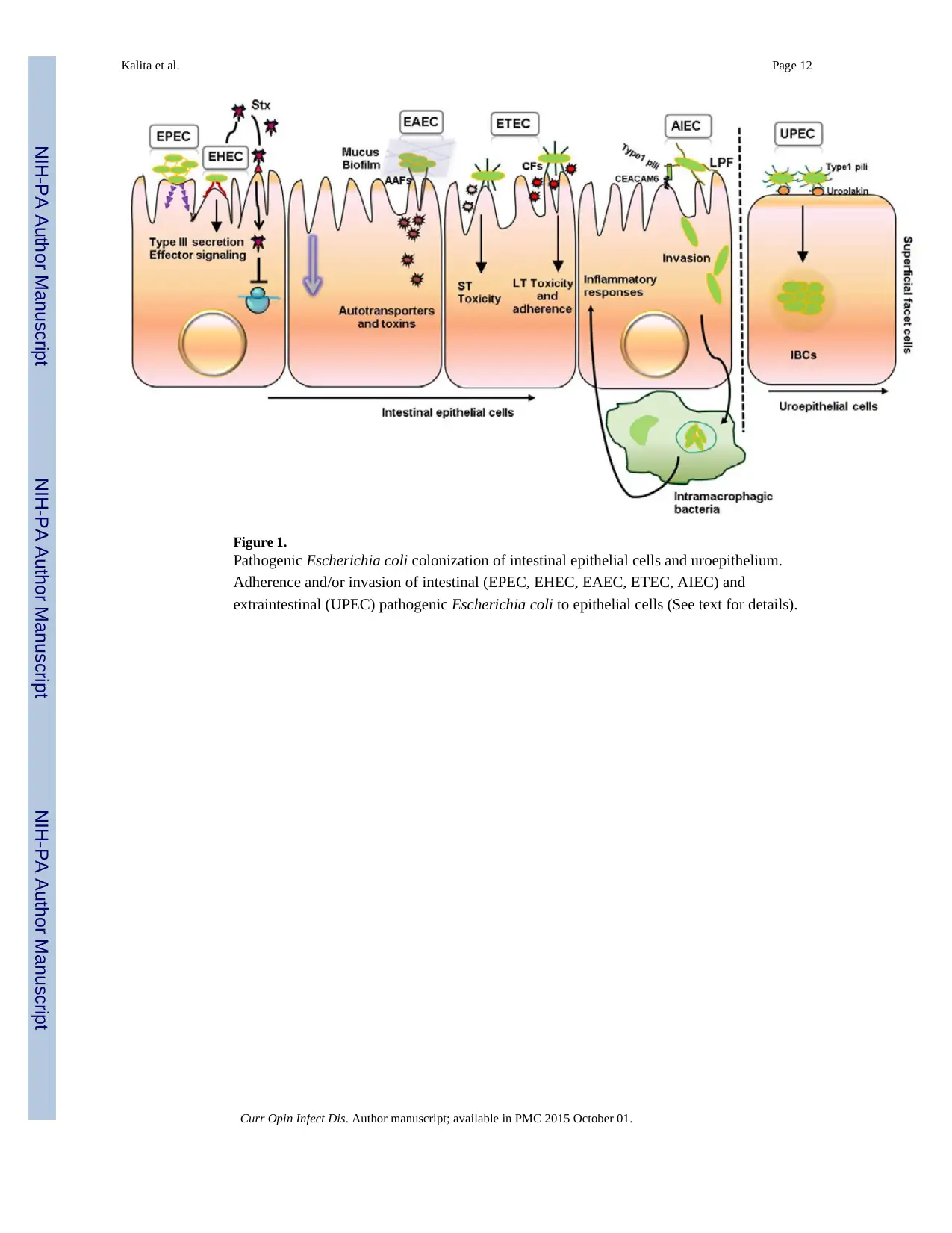

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC)

EHEC are a category of pathogenic E. coli that colonize the human large intestine and which

can cause bloody diarrhea, or a systemic process known as hemolytic uremic syndrome (4).

EHEC strains are characterized by the production of Shiga toxin and the formation of

attaching and effacing intestinal lesions (Figure 1). Cattle are a main reservoir for EHEC

strains; however several vegetables and fruits can serve as vehicles for EHEC outbreaks (5).

EHEC colonization is impacted by nutrient availability and dietary choice. Zumbrun et al

found that dietary fiber content affects susceptibility to E. coli O157:H7 infection in mice

(6). They treated BALB/c mice with high fiber diet (10% guar gum) or low fiber diet (2%

guar gum) for two weeks and then mice were challenge with 109 to 1011 cfu of E. coli

O157:H7. The results showed that mice fed with high fiber diet had enhanced levels of

butyrate that temporally increased the expression of the Shiga toxin receptor Gb3.

Therefore, mice exhibited greater E. coli O157:H7 colonization and reduction in resident

Escherichia spp. Sheng et al also showed that cattle fed a hay diet are colonized by EHEC

for a longer period of time than grain fed cattle (7). Different diets regulate the colonization

of E. coli O157:H7 by altering the composition of gastrointestinal tract microbiota and the

study demonstrated that the bacterial SdiA sensor activates genes conferring EHEC acid

resistance, increasing efficient colonization of the cattle mucosa (8).

Modulation of host signals in the intestinal epithelia also affects EHEC colonization.

Intestinal epithelial cells produced SIGIRR, a negative regulator of interleukin (IL)-1 and

TLR signaling, that makes the cells hypo-responsive (9, 10). To address whether hypo-

responsiveness affects enteric host defense, Sham et al challenge Sigirr deficient (−/−) mice

with the murine pathogen, EHEC-related, Citrobacter rodentium and showed that Sigirr−/−

mice are more susceptible to bacterial infection and had a dramatic loss of microbiota (11).

The study showed that this host signaling mechanism promotes commensal dependent

resistance to EHEC colonization.

Type III secretion system (TTSS) is required for EHEC colonization and attaching and

effacing lesion formation. This syringe-like structure used to inject virulence factors into the

host cell is exquisitely regulated. Hansen et al revealed that tyrosine phosphorylation in

EHEC mediates signaling of virulence properties, including the type III secretion system

(12). SspA is a known regulator of the TTSS (13) and a phosphorylated tyrosine residue of

this protein positively affects expression and secretion of type III secretion system proteins.

Branchu et al also found a new regulator of the TTSS (14) known as the NO-sensor

regulator, NsrR. Nitric oxide (NO) reduced EHEC adherence to intestinal epithelial cells, by

causing the detachment of the NsrR activator from the type III secretion system-encoding

operons (LEE1/4/5), limiting colonization.

Kalita et al. Page 2

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

invasion to/into host cells are the first step during infection, it is necessary to understand at a

molecular level the mechanisms mediating these initial interactions. This article focus on

reviewing recent progress on the understanding of the adhesion/invasion mechanisms used

by intestinal and extra-intestinal pathogenic E. coli during colonization of the host cells.

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC)

EHEC are a category of pathogenic E. coli that colonize the human large intestine and which

can cause bloody diarrhea, or a systemic process known as hemolytic uremic syndrome (4).

EHEC strains are characterized by the production of Shiga toxin and the formation of

attaching and effacing intestinal lesions (Figure 1). Cattle are a main reservoir for EHEC

strains; however several vegetables and fruits can serve as vehicles for EHEC outbreaks (5).

EHEC colonization is impacted by nutrient availability and dietary choice. Zumbrun et al

found that dietary fiber content affects susceptibility to E. coli O157:H7 infection in mice

(6). They treated BALB/c mice with high fiber diet (10% guar gum) or low fiber diet (2%

guar gum) for two weeks and then mice were challenge with 109 to 1011 cfu of E. coli

O157:H7. The results showed that mice fed with high fiber diet had enhanced levels of

butyrate that temporally increased the expression of the Shiga toxin receptor Gb3.

Therefore, mice exhibited greater E. coli O157:H7 colonization and reduction in resident

Escherichia spp. Sheng et al also showed that cattle fed a hay diet are colonized by EHEC

for a longer period of time than grain fed cattle (7). Different diets regulate the colonization

of E. coli O157:H7 by altering the composition of gastrointestinal tract microbiota and the

study demonstrated that the bacterial SdiA sensor activates genes conferring EHEC acid

resistance, increasing efficient colonization of the cattle mucosa (8).

Modulation of host signals in the intestinal epithelia also affects EHEC colonization.

Intestinal epithelial cells produced SIGIRR, a negative regulator of interleukin (IL)-1 and

TLR signaling, that makes the cells hypo-responsive (9, 10). To address whether hypo-

responsiveness affects enteric host defense, Sham et al challenge Sigirr deficient (−/−) mice

with the murine pathogen, EHEC-related, Citrobacter rodentium and showed that Sigirr−/−

mice are more susceptible to bacterial infection and had a dramatic loss of microbiota (11).

The study showed that this host signaling mechanism promotes commensal dependent

resistance to EHEC colonization.

Type III secretion system (TTSS) is required for EHEC colonization and attaching and

effacing lesion formation. This syringe-like structure used to inject virulence factors into the

host cell is exquisitely regulated. Hansen et al revealed that tyrosine phosphorylation in

EHEC mediates signaling of virulence properties, including the type III secretion system

(12). SspA is a known regulator of the TTSS (13) and a phosphorylated tyrosine residue of

this protein positively affects expression and secretion of type III secretion system proteins.

Branchu et al also found a new regulator of the TTSS (14) known as the NO-sensor

regulator, NsrR. Nitric oxide (NO) reduced EHEC adherence to intestinal epithelial cells, by

causing the detachment of the NsrR activator from the type III secretion system-encoding

operons (LEE1/4/5), limiting colonization.

Kalita et al. Page 2

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC)

EPEC isolates colonize the small intestine and are one of the leading causes of infantile fatal

diarrhea (15). In industrialized countries, there are sporadic diarrheal cases in daycare

facilities (16, 17). As for EHEC, EPEC uses the type III secretion system to form attaching

and effacing lesions (Figure 1). EPEC strains are subdivided into typical (tEPEC) and

atypical EPEC (aEPEC) based on the presence of EPEC adherence factor plasmid associated

with the tEPEC localized adherence pattern (18). Some aEPEC form diffuse (DA) or

aggregative adherence pattern and Hernandes et al (19) found that the DA pattern is

associated with the TTSS system and its suggested that the traslocon serves as the DA

adhesin.

Regarding the type III secretion system, recent studies have evaluated the role of the effector

protein NleB in pathogenesis. Deletion of nleB1 in C. rodentium caused significant

reduction in murine intestinal colonization (20), and NleB has also been shown to modulate

the host innate immune system by suppressing tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated NF-

κB activation (21). Three studies have investigated the role of NleB1 in EPEC. Gao et al

focused on how NleB interfere with NF-κB (22). A proteomic screen was used to identify

the host GAPDH as NleB-interacting protein, which results in modification of GAPDH and

inhibition of NF-κB-dependent innate immune responses. The other two groups discovered

that NleB blocks host death receptor signaling (23, 24), by interacting with two death

receptor-signaling proteins, TRADD and FADD. NleB is the first known bacterial virulence

factor to target death receptor signaling and it has been suggested that blocking this

signaling mechanism may facilitate EPEC and EHEC colonization.

Other studies evaluated ways to reduce EPEC adhesion to host cells. Pan et al expressed

synthetic tetrameric-branched peptide that enhanced the expression of Mucin 3 (25). They

found that Mucin 3 interacted with EPEC and EHEC and reduced their binding to epithelial

cells. In other study, Salcedo et al showed that the combination of gangliosides and sialic

acid were able to interfere with EPEC and EHEC adhesion to Caco-2 cells (26).

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)

ETEC colonizes the human small intestine and is responsible for neonatal diarrhea in

developing countries as well as “travelers’ diarrhea” (27). ETEC adherence to the intestinal

mucosa is mainly mediated by diverse adhesive structures known as colonization factors,

which in combination with the heat-labile (LT) and/or heat-stable (ST) enterotoxins, causes

disruption of fluid homeostasis in the host, resulting in diarrhea (2, 28) (Figure 1).

Guevara et al recently investigated one colonization factors, the CS21 pilus, and its role in

adherence and pathogenesis in vivo (29). They found that ETEC CS21 (Longus) adherence

to primary intestinal cells was inhibited by anti-LngA sera and the purified LngA protein. In

vivo intra-stomach administration of CS21-expressing ETEC strain contributes to 100%

lethality of newborn mice, which was reduced in the lngA mutant. A separate study

investigated the role of the LT toxin in ETEC colonization (30). The authors observed

enhanced adherence to IPEC-J2 cells by various isogenic ETEC constructs carrying different

forms of the LT toxin (K88/LT wild type, attenuated toxin form [K88/LTR192G] and

Kalita et al. Page 3

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

EPEC isolates colonize the small intestine and are one of the leading causes of infantile fatal

diarrhea (15). In industrialized countries, there are sporadic diarrheal cases in daycare

facilities (16, 17). As for EHEC, EPEC uses the type III secretion system to form attaching

and effacing lesions (Figure 1). EPEC strains are subdivided into typical (tEPEC) and

atypical EPEC (aEPEC) based on the presence of EPEC adherence factor plasmid associated

with the tEPEC localized adherence pattern (18). Some aEPEC form diffuse (DA) or

aggregative adherence pattern and Hernandes et al (19) found that the DA pattern is

associated with the TTSS system and its suggested that the traslocon serves as the DA

adhesin.

Regarding the type III secretion system, recent studies have evaluated the role of the effector

protein NleB in pathogenesis. Deletion of nleB1 in C. rodentium caused significant

reduction in murine intestinal colonization (20), and NleB has also been shown to modulate

the host innate immune system by suppressing tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated NF-

κB activation (21). Three studies have investigated the role of NleB1 in EPEC. Gao et al

focused on how NleB interfere with NF-κB (22). A proteomic screen was used to identify

the host GAPDH as NleB-interacting protein, which results in modification of GAPDH and

inhibition of NF-κB-dependent innate immune responses. The other two groups discovered

that NleB blocks host death receptor signaling (23, 24), by interacting with two death

receptor-signaling proteins, TRADD and FADD. NleB is the first known bacterial virulence

factor to target death receptor signaling and it has been suggested that blocking this

signaling mechanism may facilitate EPEC and EHEC colonization.

Other studies evaluated ways to reduce EPEC adhesion to host cells. Pan et al expressed

synthetic tetrameric-branched peptide that enhanced the expression of Mucin 3 (25). They

found that Mucin 3 interacted with EPEC and EHEC and reduced their binding to epithelial

cells. In other study, Salcedo et al showed that the combination of gangliosides and sialic

acid were able to interfere with EPEC and EHEC adhesion to Caco-2 cells (26).

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)

ETEC colonizes the human small intestine and is responsible for neonatal diarrhea in

developing countries as well as “travelers’ diarrhea” (27). ETEC adherence to the intestinal

mucosa is mainly mediated by diverse adhesive structures known as colonization factors,

which in combination with the heat-labile (LT) and/or heat-stable (ST) enterotoxins, causes

disruption of fluid homeostasis in the host, resulting in diarrhea (2, 28) (Figure 1).

Guevara et al recently investigated one colonization factors, the CS21 pilus, and its role in

adherence and pathogenesis in vivo (29). They found that ETEC CS21 (Longus) adherence

to primary intestinal cells was inhibited by anti-LngA sera and the purified LngA protein. In

vivo intra-stomach administration of CS21-expressing ETEC strain contributes to 100%

lethality of newborn mice, which was reduced in the lngA mutant. A separate study

investigated the role of the LT toxin in ETEC colonization (30). The authors observed

enhanced adherence to IPEC-J2 cells by various isogenic ETEC constructs carrying different

forms of the LT toxin (K88/LT wild type, attenuated toxin form [K88/LTR192G] and

Kalita et al. Page 3

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

expressing just the B subunit [K88/LTB]), in contrast to the attenuated phenotype of the LT-

negative construct. LT+ strains blocking binding of wild type ETEC strain to IPEC-J2 cells

suggested that LT-driven adherence alters net surface charge on epithelial cells. Another

study evaluated the transcriptional pattern of 214 genes at different time points following

interaction of prototype ETEC E24377A with epithelial cells (31). The study found a

prominent alteration of genes associated with motility, adhesion, toxin production, and

global regulatory mechanisms, such as those linked to cAMP receptor protein and c-di-

GMP, upon ETEC-host interaction, which suggested that ETEC coordinated its responses to

the host environment by sequential activation of different virulence factors.

Among those ETEC strains infecting animals, the most common adhesive fimbriae include

K88 or K99 (also called F4 and F5) (28). Recently, Zhou et al have demonstrated that

deletion of fliC (encoding the major flagellin protein) and/or the faeG (encoding the F4

major fimbrial subunit) from ETEC strain C83902 significantly reduced its ability to adhere

to porcine epithelia IPEC-J2 cells, but also impacting biofilm formation and quorum sensing

(32). Interestingly, another study found an alternative way to block the adherence of ETEC

K88 to IPEC-J2 by using ETEC anti-adhesives, including casein glycomacropeptide,

exopolysaccharide, and vegetable extract (locust bean or wheat bran) (33). Finally, studies

with human milk and commercial infant formulas found that the main gangliosides (GM3,

GD3, GM1) and free sialic acid (Neu5Ac) are able to impede the adhesion of several

pathogenic bacteria, including ETEC (26). Other dietary supplements, such as plantain NSP,

also hampered the adherence of ETEC to Caco-2 cells, and has been suggested that blocking

M-cell bacterial translocation can subsequently prevent diarrheal episodes (34).

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC)

EAEC are a major cause of acute and persistent diarrhea in the small intestine of children

and adults worldwide, including industrialized countries (35). EAEC is also responsible for

sporadic cases and several outbreaks (36). At an initial stage of infection, EAEC adhere in a

characteristic “stacked-brick” formation to host intestinal mucosa; forming a thick mucoid

biofilm. The adherence process is mainly mediated by fimbrial structures called aggregative

adherence fimbriae (AAF) (35) (Figure 1). Additionally, several EAEC virulence-related

genes have been described but their role in the clinical outcome of infection is not

completely defined.

A study recently confirmed a high prevalence, endemicity and heterogeneity of EAEC

strains, and found that the plasmid-encoded toxin or AAF/II fimbrial subunit genes were

associated significantly with disease (37). However, this study also demonstrated that the

pathophysiology of EAEC infections involves a complex and dynamic modulation of several

virulence factors. Another study identified an association of the EAEC virulence-encoded

aggR gene (virulence regulator), pCDV432 plasmid, and additional virulence gene products,

including dispersin and the Air adhesin in 90% of the diarrheagenic isolates that

distinguished them from non-diarrheagenic EAEC strains, suggesting heterogeneity among

highly pathogenic EAEC strains (38).

Kalita et al. Page 4

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

negative construct. LT+ strains blocking binding of wild type ETEC strain to IPEC-J2 cells

suggested that LT-driven adherence alters net surface charge on epithelial cells. Another

study evaluated the transcriptional pattern of 214 genes at different time points following

interaction of prototype ETEC E24377A with epithelial cells (31). The study found a

prominent alteration of genes associated with motility, adhesion, toxin production, and

global regulatory mechanisms, such as those linked to cAMP receptor protein and c-di-

GMP, upon ETEC-host interaction, which suggested that ETEC coordinated its responses to

the host environment by sequential activation of different virulence factors.

Among those ETEC strains infecting animals, the most common adhesive fimbriae include

K88 or K99 (also called F4 and F5) (28). Recently, Zhou et al have demonstrated that

deletion of fliC (encoding the major flagellin protein) and/or the faeG (encoding the F4

major fimbrial subunit) from ETEC strain C83902 significantly reduced its ability to adhere

to porcine epithelia IPEC-J2 cells, but also impacting biofilm formation and quorum sensing

(32). Interestingly, another study found an alternative way to block the adherence of ETEC

K88 to IPEC-J2 by using ETEC anti-adhesives, including casein glycomacropeptide,

exopolysaccharide, and vegetable extract (locust bean or wheat bran) (33). Finally, studies

with human milk and commercial infant formulas found that the main gangliosides (GM3,

GD3, GM1) and free sialic acid (Neu5Ac) are able to impede the adhesion of several

pathogenic bacteria, including ETEC (26). Other dietary supplements, such as plantain NSP,

also hampered the adherence of ETEC to Caco-2 cells, and has been suggested that blocking

M-cell bacterial translocation can subsequently prevent diarrheal episodes (34).

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC)

EAEC are a major cause of acute and persistent diarrhea in the small intestine of children

and adults worldwide, including industrialized countries (35). EAEC is also responsible for

sporadic cases and several outbreaks (36). At an initial stage of infection, EAEC adhere in a

characteristic “stacked-brick” formation to host intestinal mucosa; forming a thick mucoid

biofilm. The adherence process is mainly mediated by fimbrial structures called aggregative

adherence fimbriae (AAF) (35) (Figure 1). Additionally, several EAEC virulence-related

genes have been described but their role in the clinical outcome of infection is not

completely defined.

A study recently confirmed a high prevalence, endemicity and heterogeneity of EAEC

strains, and found that the plasmid-encoded toxin or AAF/II fimbrial subunit genes were

associated significantly with disease (37). However, this study also demonstrated that the

pathophysiology of EAEC infections involves a complex and dynamic modulation of several

virulence factors. Another study identified an association of the EAEC virulence-encoded

aggR gene (virulence regulator), pCDV432 plasmid, and additional virulence gene products,

including dispersin and the Air adhesin in 90% of the diarrheagenic isolates that

distinguished them from non-diarrheagenic EAEC strains, suggesting heterogeneity among

highly pathogenic EAEC strains (38).

Kalita et al. Page 4

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Another area of study in EAEC pathogenesis is the contribution of the autotransporter

proteins. Munera et al evaluated the role of chromosome-encoded autotransporters in

colonization and subsequent induction of diarrheal disease in infant rabbits and found that

Shiga toxin-producing EAEC O104:H4 autotransporters, but not its virulence plasmid, are

critical for robust colonization and disease (39). EAEC has also been associated with urinary

tract infections (40, 41). The autotrasporter Pic has been defined as a gene marker associated

with spreading of infection to the urinary tract (40). Finally, comparison of EAEC isolates

from HIV-positive and non-HIV diarrheal samples showed that HIV-positive isolates are

stronger biofilm producers and more resistant to antibiotics than the non-HIV diarrheal

isolates, which confirmed the heterogeneity of the EAEC isolates (42).

Adherent and Invasive E. coli (AIEC)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are

the result of alterations in the intestinal microbiota due to a variety of genetic and

environmental factors (43). Interestingly, an increased number of AIEC have been isolated

from IBD patients and more frequently found in ileal-Crohn’s disease patients than in

healthy controls (44). AIEC strains have the ability to adhere and invade intestinal epithelial

cells and survive within macrophages (45). Small et al recently established a chronic

infection murine model using prototypical AIEC isolates (46), and demonstrated that AIEC

infection stimulates chronic inflammation and fibrosis in mice. This study showed for the

first time evidence that an infection with AIEC can cause intestinal symptoms similar to

those observed in Crohn’s disease patients.

AIEC adherence depends on the expression of the type 1 pili, long polar fimbriae and the

presence of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEACAM6) as a host cell receptor (47, 48)

(Figure 1). Crohn’s disease patients showed abnormal expression of CEACAM6 (48) and as

such, Martinez-Medina et al used a model of transgenic mice expressing CEACAMs to

assess the effects of a high fat/high sugar western diet on gut microbiota composition,

barrier integrity and susceptibility to infection (49). They found that the diet induces

changes in gut microbiota composition, altering host homeostasis and promoting AIEC

murine gut colonization. With respect to the type 1 pili, a study sequenced the fimH gene

(FimH is the adhesin protein located on the tip of the pili) from 45 AIEC strains and 47 non-

AIEC E. coli strains. Phylogenetic analysis found that AIEC strains predominantly express

FimH with amino acid mutations of a recent evolutionary origin as compared to non-AIEC

strains, which represents a feature of pathoadaptive changes in several bacterial pathogens

(50). The accumulation of these mutations confers AIEC the ability to adhere to CEACAM-

expressing intestinal epithelial cells and to participate in the development of chronic

inflammation in a genetically susceptible host. Finally, it is known that the long polar

fimbriae help AIEC to interact with intestinal Peyer’s patches and M cells (51). A recent

study analyzed the effect of gastrointestinal conditions on AIEC long polar fimbriae

expression. The authors found that bile salts strongly enhanced fimbriae expression, causing

a higher level of interaction of AIEC with Peyer’s patches and a higher level of translocation

through M cell monolayers (52).

Kalita et al. Page 5

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

proteins. Munera et al evaluated the role of chromosome-encoded autotransporters in

colonization and subsequent induction of diarrheal disease in infant rabbits and found that

Shiga toxin-producing EAEC O104:H4 autotransporters, but not its virulence plasmid, are

critical for robust colonization and disease (39). EAEC has also been associated with urinary

tract infections (40, 41). The autotrasporter Pic has been defined as a gene marker associated

with spreading of infection to the urinary tract (40). Finally, comparison of EAEC isolates

from HIV-positive and non-HIV diarrheal samples showed that HIV-positive isolates are

stronger biofilm producers and more resistant to antibiotics than the non-HIV diarrheal

isolates, which confirmed the heterogeneity of the EAEC isolates (42).

Adherent and Invasive E. coli (AIEC)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are

the result of alterations in the intestinal microbiota due to a variety of genetic and

environmental factors (43). Interestingly, an increased number of AIEC have been isolated

from IBD patients and more frequently found in ileal-Crohn’s disease patients than in

healthy controls (44). AIEC strains have the ability to adhere and invade intestinal epithelial

cells and survive within macrophages (45). Small et al recently established a chronic

infection murine model using prototypical AIEC isolates (46), and demonstrated that AIEC

infection stimulates chronic inflammation and fibrosis in mice. This study showed for the

first time evidence that an infection with AIEC can cause intestinal symptoms similar to

those observed in Crohn’s disease patients.

AIEC adherence depends on the expression of the type 1 pili, long polar fimbriae and the

presence of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEACAM6) as a host cell receptor (47, 48)

(Figure 1). Crohn’s disease patients showed abnormal expression of CEACAM6 (48) and as

such, Martinez-Medina et al used a model of transgenic mice expressing CEACAMs to

assess the effects of a high fat/high sugar western diet on gut microbiota composition,

barrier integrity and susceptibility to infection (49). They found that the diet induces

changes in gut microbiota composition, altering host homeostasis and promoting AIEC

murine gut colonization. With respect to the type 1 pili, a study sequenced the fimH gene

(FimH is the adhesin protein located on the tip of the pili) from 45 AIEC strains and 47 non-

AIEC E. coli strains. Phylogenetic analysis found that AIEC strains predominantly express

FimH with amino acid mutations of a recent evolutionary origin as compared to non-AIEC

strains, which represents a feature of pathoadaptive changes in several bacterial pathogens

(50). The accumulation of these mutations confers AIEC the ability to adhere to CEACAM-

expressing intestinal epithelial cells and to participate in the development of chronic

inflammation in a genetically susceptible host. Finally, it is known that the long polar

fimbriae help AIEC to interact with intestinal Peyer’s patches and M cells (51). A recent

study analyzed the effect of gastrointestinal conditions on AIEC long polar fimbriae

expression. The authors found that bile salts strongly enhanced fimbriae expression, causing

a higher level of interaction of AIEC with Peyer’s patches and a higher level of translocation

through M cell monolayers (52).

Kalita et al. Page 5

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Regarding the clinical implications of AIEC recent investigation indicates that colonization

of AIEC results in chronic colitis in mice lacking the flagellin receptor TLR5. Transient

AIEC colonization drove intestinal inflammation which is associated with altering

microbiota composition (53). Proteases and protease inhibitors control microbiota

composition, immune response and intestinal function to maintain gut homeostasis. CYLD

is a de-ubiquitinase that is significantly downregulated in the intestine of Crohn’s disease

patients (54). Decrease CYLD expression results in an enhanced intracellular replication of

AIEC (54). Therefore, protection against AIEC during microbiota acquisition might be a

strategy to control IBD in genetically susceptible individuals (53).

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC)

UPEC are among the most prevalent extra-intestinal bacteria, accounting for 90% of all

urinary tract infection (UTI) (2). The most predominant chaperone-usher fimbriae in UPEC

strains is the type 1 fimbriae, which is an important determinant for pathogenicity, allowing

the interaction of UPEC with urinary tract host epithelia (55, 56). FimH within the type 1

fimbriae bound to α-D-mannosylated uroplakin, facilitating bacterial invasion, colonization

and formation of biofilm-like structures called intracellular bacterial communities (IBCs)

(57) (Figure 1). A high-throughput insilico analysis and in-vitro binding study discovered

that pathoadaptive alleles of FimH, with variant residues outside the binding pocket, affect

FimH-mediated acute and chronic pathogenesis of two prototype UPEC strains (56). The

study argues that FimH variants, which maintain a high-affinity conformation, were

attenuated during chronic bladder infection, implying FimH's ability to switch between

conformations is important during pathogenesis.

With respect to the regulatory mechanisms controlling UPEC colonization, Mitra et al found

UvrY as a key regulator modulating phase variation during UPEC pathogenesis, down-

regulating the expression of type 1 fimbrial structural genes, and influencing biofilm

formation, virulence and motility in UPEC strain CFT073 (58). Cpx is another key regulator

involved in bacterial adhesion. The deletion of cpxRA impaired the ability of UPEC strain

UTI89 to invade and colonize bladder epithelial cells, suggesting that the Cpx system is

needed for UPEC persistence in the urinary tract (59). Similarly, mutation in cpxRA and

cpxP in CFT073 also greatly reduced virulence tested the zebrafish infection model (59).

Finally, natural medicinal plants and secondary metabolites have being study because asiatic

acid and ursolic acid decreased expression of P fimbriae and curli fibers, altering cell

morphology and adhesion of UPEC to uroepithelial cells (60). Finally, Rafsanjany et al also

demonstrated anti-adhesive effects of various medicinal plant extracts against UPEC strains

(61).

Conclusion

The recent progress understanding the adhesion/invasion properties of intestinal and extra-

intestinal pathogenic E. coli during colonization of host cells reveals that there is a need of

further mechanistic studies that can be used for development of specific therapeutic

approaches.

Kalita et al. Page 6

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

of AIEC results in chronic colitis in mice lacking the flagellin receptor TLR5. Transient

AIEC colonization drove intestinal inflammation which is associated with altering

microbiota composition (53). Proteases and protease inhibitors control microbiota

composition, immune response and intestinal function to maintain gut homeostasis. CYLD

is a de-ubiquitinase that is significantly downregulated in the intestine of Crohn’s disease

patients (54). Decrease CYLD expression results in an enhanced intracellular replication of

AIEC (54). Therefore, protection against AIEC during microbiota acquisition might be a

strategy to control IBD in genetically susceptible individuals (53).

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC)

UPEC are among the most prevalent extra-intestinal bacteria, accounting for 90% of all

urinary tract infection (UTI) (2). The most predominant chaperone-usher fimbriae in UPEC

strains is the type 1 fimbriae, which is an important determinant for pathogenicity, allowing

the interaction of UPEC with urinary tract host epithelia (55, 56). FimH within the type 1

fimbriae bound to α-D-mannosylated uroplakin, facilitating bacterial invasion, colonization

and formation of biofilm-like structures called intracellular bacterial communities (IBCs)

(57) (Figure 1). A high-throughput insilico analysis and in-vitro binding study discovered

that pathoadaptive alleles of FimH, with variant residues outside the binding pocket, affect

FimH-mediated acute and chronic pathogenesis of two prototype UPEC strains (56). The

study argues that FimH variants, which maintain a high-affinity conformation, were

attenuated during chronic bladder infection, implying FimH's ability to switch between

conformations is important during pathogenesis.

With respect to the regulatory mechanisms controlling UPEC colonization, Mitra et al found

UvrY as a key regulator modulating phase variation during UPEC pathogenesis, down-

regulating the expression of type 1 fimbrial structural genes, and influencing biofilm

formation, virulence and motility in UPEC strain CFT073 (58). Cpx is another key regulator

involved in bacterial adhesion. The deletion of cpxRA impaired the ability of UPEC strain

UTI89 to invade and colonize bladder epithelial cells, suggesting that the Cpx system is

needed for UPEC persistence in the urinary tract (59). Similarly, mutation in cpxRA and

cpxP in CFT073 also greatly reduced virulence tested the zebrafish infection model (59).

Finally, natural medicinal plants and secondary metabolites have being study because asiatic

acid and ursolic acid decreased expression of P fimbriae and curli fibers, altering cell

morphology and adhesion of UPEC to uroepithelial cells (60). Finally, Rafsanjany et al also

demonstrated anti-adhesive effects of various medicinal plant extracts against UPEC strains

(61).

Conclusion

The recent progress understanding the adhesion/invasion properties of intestinal and extra-

intestinal pathogenic E. coli during colonization of host cells reveals that there is a need of

further mechanistic studies that can be used for development of specific therapeutic

approaches.

Kalita et al. Page 6

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Acknowledgments

The laboratory of A.G.T. was supported in part by NIH/NIAID grant AI079154.

References and Recommended reading

1. Leimbach A, Hacker J, Dobrindt U. E. coli as an all-rounder: the thin line between commensalism

and pathogenicity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013; 358:3–32. [PubMed: 23340801]

2. Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2004; 2:123–

140. [PubMed: 15040260]

3. Croxen MA, Law RJ, Scholz R, Keeney KM, Wlodarska M, Finlay BB. Recent advances in

understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013; 4:822–880. [PubMed:

24092857] . This is a comprehensive review highlighting recent advances in the understanding of

pathogenesis of intestinal pathotypes of E. coli.

4. Farfan MJ, Torres AG. Molecular mechanisms that mediate colonization of Shiga toxin-producing

Escherichia coli strains. Infect Immun. 2012; 80:903–913. [PubMed: 22144484]

5. Ferens WA, Hovde CJ. Escherichia coli O157:H7: animal reservoir and sources of human infection.

Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011; 8:465–487. [PubMed: 21117940]

6. Zumbrun SD, Melton-Celsa AR, Smith MA, Gilbreath JJ, Merrell DS, O'Brien AD. Dietary choice

affects Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157:H7 colonization and disease. Proc

Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110:E2126–E2133. [PubMed: 23690602] . This paper demonstrate that

susceptibility to infection and subsequent disease after E. coli O157:H7 consumption may depend,

on individual diet and/or commensal flora properties.

7. Sheng H, Nguyen YN, Hovde CJ, Sperandio V. SdiA aids enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli

carriage by cattle fed a forage or grain diet. Infect Immun. 2013; 81:3472–3478. [PubMed:

23836826]

8. Hughes DT, Terekhova DA, Liou L, Hovde CJ, Sahl JW, Patankar AV, et al. Chemical sensing in

mammalian host-bacterial commensal associations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:9831–

9836. [PubMed: 20457895]

9. Garlanda C, Riva F, Polentarutti N, Buracchi C, Sironi M, De Bortoli M, et al. Intestinal

inflammation in mice deficient in Tir8, an inhibitory member of the IL-1 receptor family. Proc Natl

Acad Sci U S A. 2004; 101:3522–3526. [PubMed: 14993616]

10. Wald D, Qin J, Zhao Z, Qian Y, Naramura M, Tian L, et al. SIGIRR, a negative regulator of Toll-

like receptor-interleukin 1 receptor signaling. Nat Immunol. 2003; 4:920–927. [PubMed:

12925853]

11. Sham HP, Yu EY, Gulen MF, Bhinder G, Stahl M, Chan JM, et al. SIGIRR, a negative regulator of

TLR/IL-1R signalling promotes Microbiota dependent resistance to colonization by enteric

bacterial pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2013; 9:e1003539. [PubMed: 23950714] . The paper

demonstrates that SIGIRR expression by intestinal epithelial cells is a strategy that promotes

commensal microbe-based colonization resistance against bacterial pathogens.

12. Hansen AM, Chaerkady R, Sharma J, Diaz-Mejia JJ, Tyagi N, Renuse S, et al. The Escherichia

coli phosphotyrosine proteome relates to core pathways and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2013;

9:e1003403. [PubMed: 23785281]

13. Hansen AM, Jin DJ. SspA up-regulates gene expression of the LEE pathogenicity island by

decreasing H-NS levels in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2012; 12:231.

[PubMed: 23051860]

14. Branchu P, Matrat S, Vareille M, Garrivier A, Durand A, Crepin S, et al. NsrR, GadE, and GadX

interplay in repressing expression of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 LEE pathogenicity island in

response to nitric oxide. PLoS Pathog. 2014; 10:e1003874. [PubMed: 24415940]

15. Ochoa TJ, Barletta F, Contreras C, Mercado E. New insights into the epidemiology of

enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008; 102:852–856.

[PubMed: 18455741]

Kalita et al. Page 7

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

The laboratory of A.G.T. was supported in part by NIH/NIAID grant AI079154.

References and Recommended reading

1. Leimbach A, Hacker J, Dobrindt U. E. coli as an all-rounder: the thin line between commensalism

and pathogenicity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013; 358:3–32. [PubMed: 23340801]

2. Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2004; 2:123–

140. [PubMed: 15040260]

3. Croxen MA, Law RJ, Scholz R, Keeney KM, Wlodarska M, Finlay BB. Recent advances in

understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013; 4:822–880. [PubMed:

24092857] . This is a comprehensive review highlighting recent advances in the understanding of

pathogenesis of intestinal pathotypes of E. coli.

4. Farfan MJ, Torres AG. Molecular mechanisms that mediate colonization of Shiga toxin-producing

Escherichia coli strains. Infect Immun. 2012; 80:903–913. [PubMed: 22144484]

5. Ferens WA, Hovde CJ. Escherichia coli O157:H7: animal reservoir and sources of human infection.

Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011; 8:465–487. [PubMed: 21117940]

6. Zumbrun SD, Melton-Celsa AR, Smith MA, Gilbreath JJ, Merrell DS, O'Brien AD. Dietary choice

affects Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157:H7 colonization and disease. Proc

Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110:E2126–E2133. [PubMed: 23690602] . This paper demonstrate that

susceptibility to infection and subsequent disease after E. coli O157:H7 consumption may depend,

on individual diet and/or commensal flora properties.

7. Sheng H, Nguyen YN, Hovde CJ, Sperandio V. SdiA aids enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli

carriage by cattle fed a forage or grain diet. Infect Immun. 2013; 81:3472–3478. [PubMed:

23836826]

8. Hughes DT, Terekhova DA, Liou L, Hovde CJ, Sahl JW, Patankar AV, et al. Chemical sensing in

mammalian host-bacterial commensal associations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:9831–

9836. [PubMed: 20457895]

9. Garlanda C, Riva F, Polentarutti N, Buracchi C, Sironi M, De Bortoli M, et al. Intestinal

inflammation in mice deficient in Tir8, an inhibitory member of the IL-1 receptor family. Proc Natl

Acad Sci U S A. 2004; 101:3522–3526. [PubMed: 14993616]

10. Wald D, Qin J, Zhao Z, Qian Y, Naramura M, Tian L, et al. SIGIRR, a negative regulator of Toll-

like receptor-interleukin 1 receptor signaling. Nat Immunol. 2003; 4:920–927. [PubMed:

12925853]

11. Sham HP, Yu EY, Gulen MF, Bhinder G, Stahl M, Chan JM, et al. SIGIRR, a negative regulator of

TLR/IL-1R signalling promotes Microbiota dependent resistance to colonization by enteric

bacterial pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2013; 9:e1003539. [PubMed: 23950714] . The paper

demonstrates that SIGIRR expression by intestinal epithelial cells is a strategy that promotes

commensal microbe-based colonization resistance against bacterial pathogens.

12. Hansen AM, Chaerkady R, Sharma J, Diaz-Mejia JJ, Tyagi N, Renuse S, et al. The Escherichia

coli phosphotyrosine proteome relates to core pathways and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2013;

9:e1003403. [PubMed: 23785281]

13. Hansen AM, Jin DJ. SspA up-regulates gene expression of the LEE pathogenicity island by

decreasing H-NS levels in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2012; 12:231.

[PubMed: 23051860]

14. Branchu P, Matrat S, Vareille M, Garrivier A, Durand A, Crepin S, et al. NsrR, GadE, and GadX

interplay in repressing expression of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 LEE pathogenicity island in

response to nitric oxide. PLoS Pathog. 2014; 10:e1003874. [PubMed: 24415940]

15. Ochoa TJ, Barletta F, Contreras C, Mercado E. New insights into the epidemiology of

enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008; 102:852–856.

[PubMed: 18455741]

Kalita et al. Page 7

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

16. Enserink R, Scholts R, Bruijning-Verhagen P, Duizer E, Vennema H, de Boer R, et al. High

detection rates of enteropathogens in asymptomatic children attending day care. PLoS ONE. 2014;

9:e89496. [PubMed: 24586825]

17. Yatsuyanagi J, Saito S, Sato H, Miyajima Y, Amano K, Enomoto K. Characterization of

enteropathogenic and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli isolated from diarrheal outbreaks. J Clin

Microbiol. 2002; 40:294–297. [PubMed: 11773137]

18. Hernandes RT, Elias WP, Vieira MA, Gomes TA. An overview of atypical enteropathogenic

Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009; 297:137–149. [PubMed: 19527295]

19. Hernandes RT, De la Cruz MA, Yamamoto D, Giron JA, Gomes TA. Dissection of the role of pili

and type 2 and 3 secretion systems in adherence and biofilm formation of an atypical

enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect Immun. 2013; 81:3793–3802. [PubMed:

23897608]

20. Kelly M, Hart E, Mundy R, Marches O, Wiles S, Badea L, et al. Essential role of the type III

secretion system effector NleB in colonization of mice by Citrobacter rodentium. Infect Immun.

2006; 74:2328–2337. [PubMed: 16552063]

21. Newton HJ, Pearson JS, Badea L, Kelly M, Lucas M, Holloway G, et al. The type III effectors

NleE and NleB from enteropathogenic E. coli and OspZ from Shigella block nuclear translocation

of NF-kappaB p65. PLoS Pathog. 2010; 6:e1000898. [PubMed: 20485572]

22. Gao X, Wang X, Pham TH, Feuerbacher LA, Lubos ML, Huang M, et al. NleB, a bacterial effector

with glycosyltransferase activity, targets GAPDH function to inhibit NF-kappaB activation. Cell

Host Microbe. 2013; 13:87–99. [PubMed: 23332158] . This paper reveals a virulence strategy

employed by Attaching and Effacing pathogens to inhibit NF-κB-dependent host innate immune

responses.

23. Pearson JS, Giogha C, Ong SY, Kennedy CL, Kelly M, Robinson KS, et al. A type III effector

antagonizes death receptor signalling during bacterial gut infection. Nature. 2013; 501:247–251.

[PubMed: 24025841]

24. Li S, Zhang L, Yao Q, Li L, Dong N, Rong J, et al. Pathogen blocks host death receptor signalling

by arginine GlcNAcylation of death domains. Nature. 2013; 501:242–246. [PubMed: 23955153] .

The paper reveals the mechanism of action of NleB, representing a new model by which bacteria

counteract host defenses.

25. Pan Q, Tian Y, Li X, Ye J, Liu Y, Song L, et al. Enhanced membrane-tethered mucin 3 (MUC3)

expression by a tetrameric branched peptide with a conserved TFLK motif inhibits bacteria

adherence. J Biol Chem. 2013; 288:5407–5416. [PubMed: 23316049]

26. Salcedo J, Barbera R, Matencio E, Alegria A, Lagarda MJ. Gangliosides and sialic acid effects

upon newborn pathogenic bacteria adhesion: an in vitro study. Food Chem. 2013; 136:726–734.

[PubMed: 23122120]

27. Beatty ME, Adcock PM, Smith SW, Quinlan K, Kamimoto LA, Rowe SY, et al. Epidemic diarrhea

due to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 42:329–334. [PubMed: 16392076]

28. Torres AG, Zhou X, Kaper JB. Adherence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains to epithelial

cells. Infect Immun. 2005; 73:18–29. [PubMed: 15618137]

29. Guevara CP, Luiz WB, Sierra A, Cruz C, Qadri F, Kaushik RS, et al. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia

coli CS21 pilus contributes to adhesion to intestinal cells and to pathogenesis under in vivo

conditions. Microbiology. 2013; 159:1725–1735. [PubMed: 23760820]

30. Fekete PZ, Mateo KS, Zhang W, Moxley RA, Kaushik RS, Francis DH. Both enzymatic and non-

enzymatic properties of heat-labile enterotoxin are responsible for LT-enhanced adherence of

enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli to porcine IPEC-J2 cells. Vet Microbiol. 2013; 164:330–335.

[PubMed: 23517763]

31. Kansal R, Rasko DA, Sahl JW, Munson GP, Roy K, Luo Q, et al. Transcriptional modulation of

enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli virulence genes in response to epithelial cell interactions. Infect

Immun. 2013; 81:259–270. [PubMed: 23115039] . This manuscript demonstrated that pathogen-

host interactions are finely coordinated by ETEC during the infectious process.

32. Zhou M, Duan Q, Zhu X, Guo Z, Li Y, Hardwidge PR, et al. Both flagella and F4 fimbriae from

F4ac+ enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli contribute to attachment to IPEC-J2 cells in vitro. Vet Res.

2013; 44:30. [PubMed: 23668601]

Kalita et al. Page 8

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

detection rates of enteropathogens in asymptomatic children attending day care. PLoS ONE. 2014;

9:e89496. [PubMed: 24586825]

17. Yatsuyanagi J, Saito S, Sato H, Miyajima Y, Amano K, Enomoto K. Characterization of

enteropathogenic and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli isolated from diarrheal outbreaks. J Clin

Microbiol. 2002; 40:294–297. [PubMed: 11773137]

18. Hernandes RT, Elias WP, Vieira MA, Gomes TA. An overview of atypical enteropathogenic

Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009; 297:137–149. [PubMed: 19527295]

19. Hernandes RT, De la Cruz MA, Yamamoto D, Giron JA, Gomes TA. Dissection of the role of pili

and type 2 and 3 secretion systems in adherence and biofilm formation of an atypical

enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect Immun. 2013; 81:3793–3802. [PubMed:

23897608]

20. Kelly M, Hart E, Mundy R, Marches O, Wiles S, Badea L, et al. Essential role of the type III

secretion system effector NleB in colonization of mice by Citrobacter rodentium. Infect Immun.

2006; 74:2328–2337. [PubMed: 16552063]

21. Newton HJ, Pearson JS, Badea L, Kelly M, Lucas M, Holloway G, et al. The type III effectors

NleE and NleB from enteropathogenic E. coli and OspZ from Shigella block nuclear translocation

of NF-kappaB p65. PLoS Pathog. 2010; 6:e1000898. [PubMed: 20485572]

22. Gao X, Wang X, Pham TH, Feuerbacher LA, Lubos ML, Huang M, et al. NleB, a bacterial effector

with glycosyltransferase activity, targets GAPDH function to inhibit NF-kappaB activation. Cell

Host Microbe. 2013; 13:87–99. [PubMed: 23332158] . This paper reveals a virulence strategy

employed by Attaching and Effacing pathogens to inhibit NF-κB-dependent host innate immune

responses.

23. Pearson JS, Giogha C, Ong SY, Kennedy CL, Kelly M, Robinson KS, et al. A type III effector

antagonizes death receptor signalling during bacterial gut infection. Nature. 2013; 501:247–251.

[PubMed: 24025841]

24. Li S, Zhang L, Yao Q, Li L, Dong N, Rong J, et al. Pathogen blocks host death receptor signalling

by arginine GlcNAcylation of death domains. Nature. 2013; 501:242–246. [PubMed: 23955153] .

The paper reveals the mechanism of action of NleB, representing a new model by which bacteria

counteract host defenses.

25. Pan Q, Tian Y, Li X, Ye J, Liu Y, Song L, et al. Enhanced membrane-tethered mucin 3 (MUC3)

expression by a tetrameric branched peptide with a conserved TFLK motif inhibits bacteria

adherence. J Biol Chem. 2013; 288:5407–5416. [PubMed: 23316049]

26. Salcedo J, Barbera R, Matencio E, Alegria A, Lagarda MJ. Gangliosides and sialic acid effects

upon newborn pathogenic bacteria adhesion: an in vitro study. Food Chem. 2013; 136:726–734.

[PubMed: 23122120]

27. Beatty ME, Adcock PM, Smith SW, Quinlan K, Kamimoto LA, Rowe SY, et al. Epidemic diarrhea

due to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 42:329–334. [PubMed: 16392076]

28. Torres AG, Zhou X, Kaper JB. Adherence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains to epithelial

cells. Infect Immun. 2005; 73:18–29. [PubMed: 15618137]

29. Guevara CP, Luiz WB, Sierra A, Cruz C, Qadri F, Kaushik RS, et al. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia

coli CS21 pilus contributes to adhesion to intestinal cells and to pathogenesis under in vivo

conditions. Microbiology. 2013; 159:1725–1735. [PubMed: 23760820]

30. Fekete PZ, Mateo KS, Zhang W, Moxley RA, Kaushik RS, Francis DH. Both enzymatic and non-

enzymatic properties of heat-labile enterotoxin are responsible for LT-enhanced adherence of

enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli to porcine IPEC-J2 cells. Vet Microbiol. 2013; 164:330–335.

[PubMed: 23517763]

31. Kansal R, Rasko DA, Sahl JW, Munson GP, Roy K, Luo Q, et al. Transcriptional modulation of

enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli virulence genes in response to epithelial cell interactions. Infect

Immun. 2013; 81:259–270. [PubMed: 23115039] . This manuscript demonstrated that pathogen-

host interactions are finely coordinated by ETEC during the infectious process.

32. Zhou M, Duan Q, Zhu X, Guo Z, Li Y, Hardwidge PR, et al. Both flagella and F4 fimbriae from

F4ac+ enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli contribute to attachment to IPEC-J2 cells in vitro. Vet Res.

2013; 44:30. [PubMed: 23668601]

Kalita et al. Page 8

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

33. Gonzalez-Ortiz G, Perez JF, Hermes RG, Molist F, Jimenez-Diaz R, Martin-Orue SM. Screening

the ability of natural feed ingredients to interfere with the adherence of enterotoxigenic

Escherichia coli (ETEC) K88 to the porcine intestinal mucus. Br J Nutr. 2014; 111:633–642.

[PubMed: 24047890]

34. Roberts CL, Keita AV, Parsons BN, Prorok-Hamon M, Knight P, Winstanley C, et al. Soluble

plantain fibre blocks adhesion and M-cell translocation of intestinal pathogens. J Nutr Biochem.

2013; 24:97–103. [PubMed: 22818716]

35. Flores J, Okhuysen PC. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli infection. Curr Opin Gastroenterol.

2009; 25:8–11. [PubMed: 19114769]

36. Weintraub A. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli : epidemiology, virulence and detection. J Med

Microbiol. 2007; 56:4–8. [PubMed: 17172509]

37. Lima IF, Boisen N, Quetz Jda S, Havt A, de Carvalho EB, Soares AM, et al. Prevalence of

enteroaggregative Escherichia coli and its virulence-related genes in a case-control study among

children from north-eastern Brazil. J Med Microbiol. 2013; 62:683–693. [PubMed: 23429698]

38. Nuesch-Inderbinen MT, Hofer E, Hachler H, Beutin L, Stephan R. Characteristics of

enteroaggregative Escherichia coli isolated from healthy carriers and from patients with diarrhoea.

J Med Microbiol. 2013; 62:1828–1834. [PubMed: 24008499]

39. Munera D, Ritchie JM, Hatzios SK, Bronson R, Fang G, Schadt EE, et al. Autotransporters but not

pAA are critical for rabbit colonization by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4. Nat

Commun. 2014; 5:3080. [PubMed: 24445323] . This study revealed that the virulence pAA

plasmid in STEC O104:H4 is dispensable for intestinal colonization while the production of

autotransporters is critical for development of intestinal pathology.

40. Herzog K, Engeler Dusel J, Hugentobler M, Beutin L, Sagesser G, Stephan R, et al. Diarrheagenic

enteroaggregative Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infection and bacteremia leading to sepsis.

Infection. 2014; 42:441–444. [PubMed: 24323785]

41. Boll EJ, Struve C, Boisen N, Olesen B, Stahlhut SG, Krogfelt KA. Role of enteroaggregative

Escherichia coli virulence factors in uropathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2013; 81:1164–1171.

[PubMed: 23357383] . The study found that EAEC-specific virulence factors increase

uropathogenicity and strains carrying these factors might cause a community-acquired urinary

tract infections.

42. Jafari A, Shafaei E, Oloomi M, Aghasadeghi MR, Bouzari S. Genotypic and Phenotypic

Comparison of Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli Isolates from HIV-Positive and non-HIV

Diarrheal Samples. Curr HIV Res. 2014 [Epub ahead of print].

43. Cieza RJ, Cao AT, Cong Y, Torres AG. Immunomodulation for gastrointestinal infections. Expert

Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012; 10:391–400. [PubMed: 22397571]

44. Rolhion N, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel

disease. Bowel Dis. 2007; 13:1277–1283.

45. Glasser AL, Boudeau J, Barnich N, Perruchot MH, Colombel JF, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Adherent

invasive Escherichia coli strains from patients with Crohn's disease survive and replicate within

macrophages without inducing host cell death. Infect Immun. 2001; 69:5529–5537. [PubMed:

11500426]

46. Small CL, Reid-Yu SA, McPhee JB, Coombes BK. Persistent infection with Crohn's disease-

associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli leads to chronic inflammation and intestinal fibrosis.

Nat Commun. 2013; 4:1957. [PubMed: 23748852] . This paper describes a murine model in which

chronic adherent-invasive E. coli infections result in immunopathology similar to that seen in

Crohn's disease patients.

47. Glas J, Seiderer J, Fries C, Tillack C, Pfennig S, Weidinger M, et al. CEACAM6 gene variants in

inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e19319. [PubMed: 21559399]

48. Barnich N, Carvalho FA, Glasser AL, Darcha C, Jantscheff P, Allez M, et al. CEACAM6 acts as a

receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli supporting ileal mucosa colonization in Crohn disease. J

Clin Invest. 2007; 117:1566–1574. [PubMed: 17525800]

49. Martinez-Medina M, Denizot J, Dreux N, Robin F, Billard E, Bonnet R, et al. Western diet induces

dysbiosis with increased E. coli in CEABAC10 mice, alters host barrier function favouring AIEC

colonisation. Gut. 2014; 63:116–124. [PubMed: 23598352]

Kalita et al. Page 9

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

the ability of natural feed ingredients to interfere with the adherence of enterotoxigenic

Escherichia coli (ETEC) K88 to the porcine intestinal mucus. Br J Nutr. 2014; 111:633–642.

[PubMed: 24047890]

34. Roberts CL, Keita AV, Parsons BN, Prorok-Hamon M, Knight P, Winstanley C, et al. Soluble

plantain fibre blocks adhesion and M-cell translocation of intestinal pathogens. J Nutr Biochem.

2013; 24:97–103. [PubMed: 22818716]

35. Flores J, Okhuysen PC. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli infection. Curr Opin Gastroenterol.

2009; 25:8–11. [PubMed: 19114769]

36. Weintraub A. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli : epidemiology, virulence and detection. J Med

Microbiol. 2007; 56:4–8. [PubMed: 17172509]

37. Lima IF, Boisen N, Quetz Jda S, Havt A, de Carvalho EB, Soares AM, et al. Prevalence of

enteroaggregative Escherichia coli and its virulence-related genes in a case-control study among

children from north-eastern Brazil. J Med Microbiol. 2013; 62:683–693. [PubMed: 23429698]

38. Nuesch-Inderbinen MT, Hofer E, Hachler H, Beutin L, Stephan R. Characteristics of

enteroaggregative Escherichia coli isolated from healthy carriers and from patients with diarrhoea.

J Med Microbiol. 2013; 62:1828–1834. [PubMed: 24008499]

39. Munera D, Ritchie JM, Hatzios SK, Bronson R, Fang G, Schadt EE, et al. Autotransporters but not

pAA are critical for rabbit colonization by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4. Nat

Commun. 2014; 5:3080. [PubMed: 24445323] . This study revealed that the virulence pAA

plasmid in STEC O104:H4 is dispensable for intestinal colonization while the production of

autotransporters is critical for development of intestinal pathology.

40. Herzog K, Engeler Dusel J, Hugentobler M, Beutin L, Sagesser G, Stephan R, et al. Diarrheagenic

enteroaggregative Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infection and bacteremia leading to sepsis.

Infection. 2014; 42:441–444. [PubMed: 24323785]

41. Boll EJ, Struve C, Boisen N, Olesen B, Stahlhut SG, Krogfelt KA. Role of enteroaggregative

Escherichia coli virulence factors in uropathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2013; 81:1164–1171.

[PubMed: 23357383] . The study found that EAEC-specific virulence factors increase

uropathogenicity and strains carrying these factors might cause a community-acquired urinary

tract infections.

42. Jafari A, Shafaei E, Oloomi M, Aghasadeghi MR, Bouzari S. Genotypic and Phenotypic

Comparison of Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli Isolates from HIV-Positive and non-HIV

Diarrheal Samples. Curr HIV Res. 2014 [Epub ahead of print].

43. Cieza RJ, Cao AT, Cong Y, Torres AG. Immunomodulation for gastrointestinal infections. Expert

Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012; 10:391–400. [PubMed: 22397571]

44. Rolhion N, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel

disease. Bowel Dis. 2007; 13:1277–1283.

45. Glasser AL, Boudeau J, Barnich N, Perruchot MH, Colombel JF, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Adherent

invasive Escherichia coli strains from patients with Crohn's disease survive and replicate within

macrophages without inducing host cell death. Infect Immun. 2001; 69:5529–5537. [PubMed:

11500426]

46. Small CL, Reid-Yu SA, McPhee JB, Coombes BK. Persistent infection with Crohn's disease-

associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli leads to chronic inflammation and intestinal fibrosis.

Nat Commun. 2013; 4:1957. [PubMed: 23748852] . This paper describes a murine model in which

chronic adherent-invasive E. coli infections result in immunopathology similar to that seen in

Crohn's disease patients.

47. Glas J, Seiderer J, Fries C, Tillack C, Pfennig S, Weidinger M, et al. CEACAM6 gene variants in

inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e19319. [PubMed: 21559399]

48. Barnich N, Carvalho FA, Glasser AL, Darcha C, Jantscheff P, Allez M, et al. CEACAM6 acts as a

receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli supporting ileal mucosa colonization in Crohn disease. J

Clin Invest. 2007; 117:1566–1574. [PubMed: 17525800]

49. Martinez-Medina M, Denizot J, Dreux N, Robin F, Billard E, Bonnet R, et al. Western diet induces

dysbiosis with increased E. coli in CEABAC10 mice, alters host barrier function favouring AIEC

colonisation. Gut. 2014; 63:116–124. [PubMed: 23598352]

Kalita et al. Page 9

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

50. Dreux N, Denizot J, Martinez-Medina M, Mellmann A, Billig M, Kisiela D, et al. Point mutations

in FimH adhesin of Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli enhance

intestinal inflammatory response. PLoS Pathog. 2013; 9:e1003141. [PubMed: 23358328] . This

study highlights a mechanism of AIEC virulence evolution that leads to the development of

chronic inflammatory bowel disease in a genetically susceptible host.

51. Chassaing B, Rolhion N, de Vallee A, Salim SY, Prorok-Hamon M, Neut C, et al. Crohn disease--

associated adherent-invasive E. coli bacteria target mouse and human Peyer's patches via long

polar fimbriae. J Clin Invest. 2011; 121:966–975. [PubMed: 21339647]

52. Chassaing B, Etienne-Mesmin L, Bonnet R, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Bile salts induce long polar

fimbriae expression favouring Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli

interaction with Peyer's patches. Environ Microbiol. 2013; 15:355–371. [PubMed: 22789019]

53. Chassaing B, Koren O, Carvalho FA, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. AIEC pathobiont instigates chronic

colitis in susceptible hosts by altering microbiota composition. Gut. 2014; 63:1069–1080.

[PubMed: 23896971]

54. Cleynen I, Vazeille E, Artieda M, Verspaget HW, Szczypiorska M, Bringer MA, et al. Genetic and

microbial factors modulating the ubiquitin proteasome system in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut.

2013 [Epub ahead of print].

55. Sauer FG, Mulvey MA, Schilling JD, Martinez JJ, Hultgren SJ. Bacterial pili: molecular

mechanisms of pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000; 3:65–72. [PubMed: 10679419]

56. Schwartz DJ, Kalas V, Pinkner JS, Chen SL, Spaulding CN, Dodson KW, et al. Positively selected

FimH residues enhance virulence during urinary tract infection by altering FimH conformation.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110:15530–15537. [PubMed: 24003161] . This study present

evidence indicating that positively selected residues within type 1 fimbriae modulate bacterial

fitness during UTI by affecting FimH conformation and function.

57. Anderson GG, Palermo JJ, Schilling JD, Roth R, Heuser J, Hultgren SJ. Intracellular bacterial

biofilm-like pods in urinary tract infections. Science. 2003; 301:105–107. [PubMed: 12843396]

58. Mitra A, Palaniyandi S, Herren CD, Zhu X, Mukhopadhyay S. Pleiotropic roles of uvrY on biofilm

formation, motility and virulence in uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073. PLoS One. 2013;

8:e55492. [PubMed: 23383333]

59. Debnath I, Norton JP, Barber AE, Ott EM, Dhakal BK, Kulesus RR, et al. The Cpx stress response

system potentiates the fitness and virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun.

2013; 81:1450–1459. [PubMed: 23429541]

60. Dorota W, Marta K, Dorota TG. Effect of asiatic and ursolic acids on morphology, hydrophobicity,

and adhesion of UPECs to uroepithelial cells. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2013; 58:245–252.

[PubMed: 23132656]

61. Rafsanjany N, Lechtenberg M, Petereit F, Hensel A. Antiadhesion as a functional concept for

protection against uropathogenic Escherichia coli : in vitro studies with traditionally used plants

with antiadhesive activity against uropathognic Escherichia coli. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;

145:591–597. [PubMed: 23211661]

Kalita et al. Page 10

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

in FimH adhesin of Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli enhance

intestinal inflammatory response. PLoS Pathog. 2013; 9:e1003141. [PubMed: 23358328] . This

study highlights a mechanism of AIEC virulence evolution that leads to the development of

chronic inflammatory bowel disease in a genetically susceptible host.

51. Chassaing B, Rolhion N, de Vallee A, Salim SY, Prorok-Hamon M, Neut C, et al. Crohn disease--

associated adherent-invasive E. coli bacteria target mouse and human Peyer's patches via long

polar fimbriae. J Clin Invest. 2011; 121:966–975. [PubMed: 21339647]

52. Chassaing B, Etienne-Mesmin L, Bonnet R, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Bile salts induce long polar

fimbriae expression favouring Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli

interaction with Peyer's patches. Environ Microbiol. 2013; 15:355–371. [PubMed: 22789019]

53. Chassaing B, Koren O, Carvalho FA, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. AIEC pathobiont instigates chronic

colitis in susceptible hosts by altering microbiota composition. Gut. 2014; 63:1069–1080.

[PubMed: 23896971]

54. Cleynen I, Vazeille E, Artieda M, Verspaget HW, Szczypiorska M, Bringer MA, et al. Genetic and

microbial factors modulating the ubiquitin proteasome system in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut.

2013 [Epub ahead of print].

55. Sauer FG, Mulvey MA, Schilling JD, Martinez JJ, Hultgren SJ. Bacterial pili: molecular

mechanisms of pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000; 3:65–72. [PubMed: 10679419]

56. Schwartz DJ, Kalas V, Pinkner JS, Chen SL, Spaulding CN, Dodson KW, et al. Positively selected

FimH residues enhance virulence during urinary tract infection by altering FimH conformation.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110:15530–15537. [PubMed: 24003161] . This study present

evidence indicating that positively selected residues within type 1 fimbriae modulate bacterial

fitness during UTI by affecting FimH conformation and function.

57. Anderson GG, Palermo JJ, Schilling JD, Roth R, Heuser J, Hultgren SJ. Intracellular bacterial

biofilm-like pods in urinary tract infections. Science. 2003; 301:105–107. [PubMed: 12843396]

58. Mitra A, Palaniyandi S, Herren CD, Zhu X, Mukhopadhyay S. Pleiotropic roles of uvrY on biofilm

formation, motility and virulence in uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073. PLoS One. 2013;

8:e55492. [PubMed: 23383333]

59. Debnath I, Norton JP, Barber AE, Ott EM, Dhakal BK, Kulesus RR, et al. The Cpx stress response

system potentiates the fitness and virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun.

2013; 81:1450–1459. [PubMed: 23429541]

60. Dorota W, Marta K, Dorota TG. Effect of asiatic and ursolic acids on morphology, hydrophobicity,

and adhesion of UPECs to uroepithelial cells. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2013; 58:245–252.

[PubMed: 23132656]

61. Rafsanjany N, Lechtenberg M, Petereit F, Hensel A. Antiadhesion as a functional concept for

protection against uropathogenic Escherichia coli : in vitro studies with traditionally used plants

with antiadhesive activity against uropathognic Escherichia coli. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;

145:591–597. [PubMed: 23211661]

Kalita et al. Page 10

Curr Opin Infect Dis. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 October 01.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Paraphrase This Document