ECO12 Macroeconomics: Job Boom, Unemployment, and Monetary Policy

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/04

|13

|2395

|219

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the Australian labour market, focusing on job growth, unemployment rates, and the Reserve Bank of Australia's (RBA) monetary policy responses. It examines the relationship between job creation, labour force participation, and unemployment, highlighting the shift from full-time to part-time employment. The aggregate expenditure model is used to illustrate economic equilibrium and potential inflationary gaps. Furthermore, the report employs static and dynamic AD-AS models to assess the impact of economic growth and aggregate demand shocks on inflation and interest rates. The analysis considers the pressure on the RBA to adjust interest rates in response to job market trends and discusses the potential implications of various monetary and fiscal policies.

Running head: MACROECONOMICS

Macroeconomics

Name of the student

Name of the university

Author Note

Macroeconomics

Name of the student

Name of the university

Author Note

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1MACROECONOMICS

Table of Contents

Answer 1 (a):...................................................................................................................................2

Answer 1 (b):...................................................................................................................................3

Answer 2:.........................................................................................................................................4

Answer 3:.........................................................................................................................................6

Answer 4:.........................................................................................................................................9

References:....................................................................................................................................11

Table of Contents

Answer 1 (a):...................................................................................................................................2

Answer 1 (b):...................................................................................................................................3

Answer 2:.........................................................................................................................................4

Answer 3:.........................................................................................................................................6

Answer 4:.........................................................................................................................................9

References:....................................................................................................................................11

2MACROECONOMICS

Answer to question 1 (a):

Job growth is a statistical measurement through which the government of any country can

track creation of new jobs on a monthly basis (Adelino, Ma and Robinson 2017). Hence, this

figure measures economic expansion of the country and consequently represents health of the

national economy.

Labour force participation rate, on the other side, measures the proportion of working-age

population, which actively engages within a country’s labour market. They can be engaged

through working or seeking for a job (Elsby, Hobijn and Şahin 2015). Thus, participation rate

gives the indication of available supply of labour compare to the working age population for

producing goods and services. Hence, this rate provides the distribution of the total working

force of a country.

The unemployment rate is another concept related with labour market. This rate

represents the share of total labour force, which is jobless, in terms of percentage. This rate is

considered as a lagging indicator, which implies measurable economic factor. This factor

changes when the economy starts to follow a specific trend (Theut Riis, Thorlacius, Knudsen

List and Jemec 2017). Thus, this unemployment rate rise when the economy experiences poor

conditions and jobs become scarce. On the contrary, if the economy follows a healthy rate as

well as huge number of jobs, then this rate could be decreased. In this context, it can be

mentioned that labour force participation rate and unemployment rate has opposite relation.

Thus, these three indicators has close link through which labour market of Australia can

be described. Through job growth, the economy can increase its labour force participation rate in

job market. This in turn can reduce the unemployment rate and represent a healthy labour market

Answer to question 1 (a):

Job growth is a statistical measurement through which the government of any country can

track creation of new jobs on a monthly basis (Adelino, Ma and Robinson 2017). Hence, this

figure measures economic expansion of the country and consequently represents health of the

national economy.

Labour force participation rate, on the other side, measures the proportion of working-age

population, which actively engages within a country’s labour market. They can be engaged

through working or seeking for a job (Elsby, Hobijn and Şahin 2015). Thus, participation rate

gives the indication of available supply of labour compare to the working age population for

producing goods and services. Hence, this rate provides the distribution of the total working

force of a country.

The unemployment rate is another concept related with labour market. This rate

represents the share of total labour force, which is jobless, in terms of percentage. This rate is

considered as a lagging indicator, which implies measurable economic factor. This factor

changes when the economy starts to follow a specific trend (Theut Riis, Thorlacius, Knudsen

List and Jemec 2017). Thus, this unemployment rate rise when the economy experiences poor

conditions and jobs become scarce. On the contrary, if the economy follows a healthy rate as

well as huge number of jobs, then this rate could be decreased. In this context, it can be

mentioned that labour force participation rate and unemployment rate has opposite relation.

Thus, these three indicators has close link through which labour market of Australia can

be described. Through job growth, the economy can increase its labour force participation rate in

job market. This in turn can reduce the unemployment rate and represent a healthy labour market

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3MACROECONOMICS

(Mokyr, Vickers and Ziebarth 2015). Thus, according to the given scenario, more jobs are need

to create for reducing the unemployment rate.

Answer to question 1 (b):

The official unemployment rate is used in Australia to understand its labour market

condition. This situation occurs when someone wants to work though becomes unable to find

one. The job growth in this country fails to achieve the target, as full-time employment level

declines. The number of part-time job increases considerably and this reduces the rate of jobless

workers (Beveridge 2014). Labour market in Australia has reached almost near to its full

employment level. Therefore, unemployment rate is not reducing further, as many people are

entering into the job market for seeking job. As a result, work force participation rate also

becomes high. However, overall the number of part-time work becomes high compare to full-

time work.

Full employment implies an economic situation, where the economy can successfully

utilises all available labour resources efficiently. Full employment considers both skilled and

unskilled labours. Job growth considers both part-time and full time work while unemployment

rate of Australia also considers the same (Frey and Osborne 2017). Thus, job growth cannot

affect official unemployment rate due to full-time positions compare to part-time ones.

(Mokyr, Vickers and Ziebarth 2015). Thus, according to the given scenario, more jobs are need

to create for reducing the unemployment rate.

Answer to question 1 (b):

The official unemployment rate is used in Australia to understand its labour market

condition. This situation occurs when someone wants to work though becomes unable to find

one. The job growth in this country fails to achieve the target, as full-time employment level

declines. The number of part-time job increases considerably and this reduces the rate of jobless

workers (Beveridge 2014). Labour market in Australia has reached almost near to its full

employment level. Therefore, unemployment rate is not reducing further, as many people are

entering into the job market for seeking job. As a result, work force participation rate also

becomes high. However, overall the number of part-time work becomes high compare to full-

time work.

Full employment implies an economic situation, where the economy can successfully

utilises all available labour resources efficiently. Full employment considers both skilled and

unskilled labours. Job growth considers both part-time and full time work while unemployment

rate of Australia also considers the same (Frey and Osborne 2017). Thus, job growth cannot

affect official unemployment rate due to full-time positions compare to part-time ones.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4MACROECONOMICS

Answer to question 2:

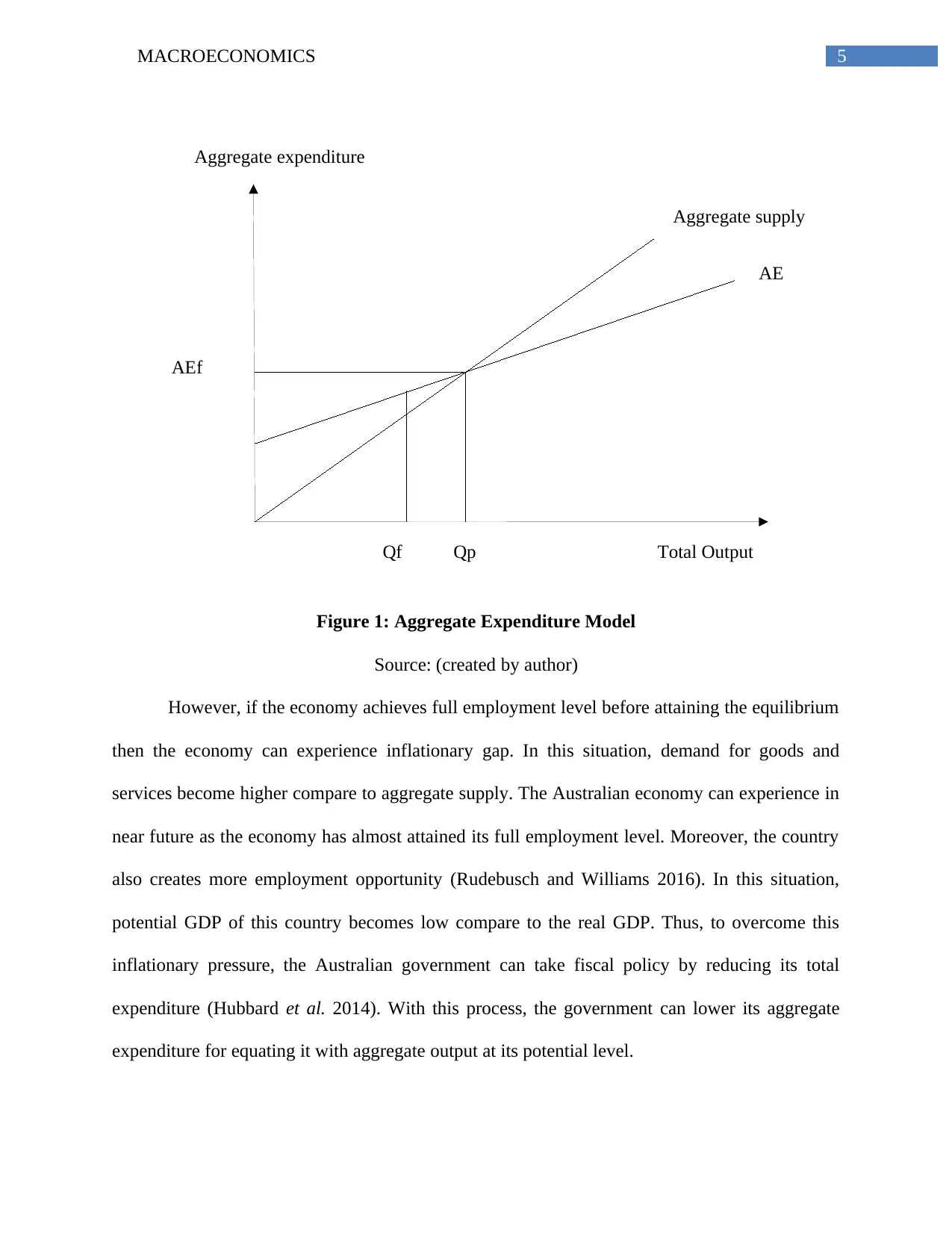

Aggregate expenditure model is equal with the sum of planned household consumption

(C) along with investment (I), government expenditure (G) and net exports (NX) at a particular

price level. Hence, the equation of aggregate expenditure (AE) is as follows:

AE= C+I+G+ NX

AE measures aggregate amount that households and firms intend to spend on goods and

services at each income level. The economy can reaches to an equilibrium level if aggregate

expenditure equates with aggregate supply or total output of the economy (Rodríguez 2018). If

the economy produces output at its full employment level then total expenditure equates with

total output. However, if the economy experiences more expenditure compare to aggregate

supply than output or prices can be increased due to higher demand (DiMasi, Grabowski and

Hansen 2016). On the contrary, if the economy experiences excess supply compare to aggregate

expenditure then prices or output level can be reduced and this in turn can reduce total national

income or gross domestic product of the economy.

Answer to question 2:

Aggregate expenditure model is equal with the sum of planned household consumption

(C) along with investment (I), government expenditure (G) and net exports (NX) at a particular

price level. Hence, the equation of aggregate expenditure (AE) is as follows:

AE= C+I+G+ NX

AE measures aggregate amount that households and firms intend to spend on goods and

services at each income level. The economy can reaches to an equilibrium level if aggregate

expenditure equates with aggregate supply or total output of the economy (Rodríguez 2018). If

the economy produces output at its full employment level then total expenditure equates with

total output. However, if the economy experiences more expenditure compare to aggregate

supply than output or prices can be increased due to higher demand (DiMasi, Grabowski and

Hansen 2016). On the contrary, if the economy experiences excess supply compare to aggregate

expenditure then prices or output level can be reduced and this in turn can reduce total national

income or gross domestic product of the economy.

5MACROECONOMICS

Aggregate expenditure

Total Output

AE

Qf

AEf

Aggregate supply

Qp

Figure 1: Aggregate Expenditure Model

Source: (created by author)

However, if the economy achieves full employment level before attaining the equilibrium

then the economy can experience inflationary gap. In this situation, demand for goods and

services become higher compare to aggregate supply. The Australian economy can experience in

near future as the economy has almost attained its full employment level. Moreover, the country

also creates more employment opportunity (Rudebusch and Williams 2016). In this situation,

potential GDP of this country becomes low compare to the real GDP. Thus, to overcome this

inflationary pressure, the Australian government can take fiscal policy by reducing its total

expenditure (Hubbard et al. 2014). With this process, the government can lower its aggregate

expenditure for equating it with aggregate output at its potential level.

Aggregate expenditure

Total Output

AE

Qf

AEf

Aggregate supply

Qp

Figure 1: Aggregate Expenditure Model

Source: (created by author)

However, if the economy achieves full employment level before attaining the equilibrium

then the economy can experience inflationary gap. In this situation, demand for goods and

services become higher compare to aggregate supply. The Australian economy can experience in

near future as the economy has almost attained its full employment level. Moreover, the country

also creates more employment opportunity (Rudebusch and Williams 2016). In this situation,

potential GDP of this country becomes low compare to the real GDP. Thus, to overcome this

inflationary pressure, the Australian government can take fiscal policy by reducing its total

expenditure (Hubbard et al. 2014). With this process, the government can lower its aggregate

expenditure for equating it with aggregate output at its potential level.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6MACROECONOMICS

Answer to question 3:

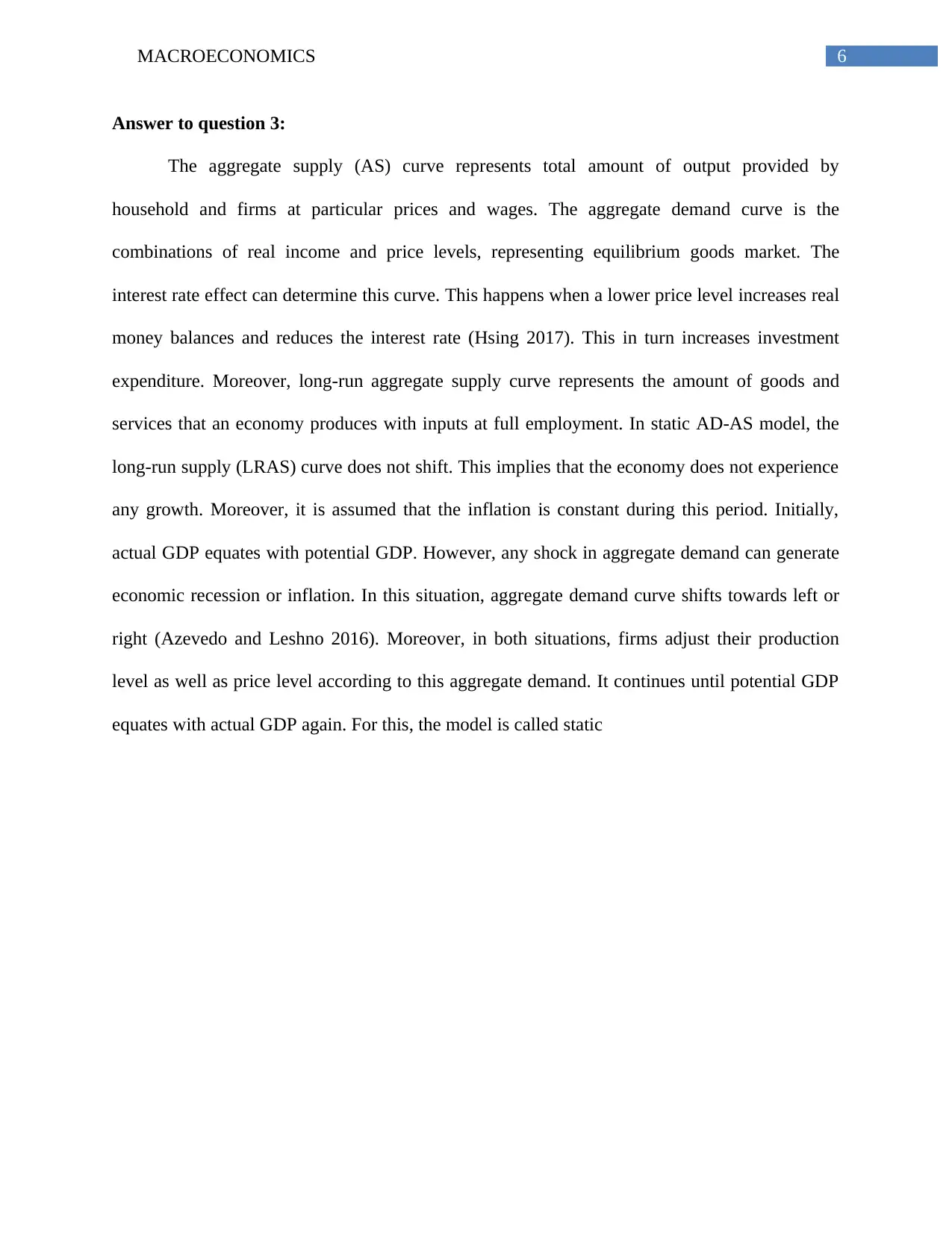

The aggregate supply (AS) curve represents total amount of output provided by

household and firms at particular prices and wages. The aggregate demand curve is the

combinations of real income and price levels, representing equilibrium goods market. The

interest rate effect can determine this curve. This happens when a lower price level increases real

money balances and reduces the interest rate (Hsing 2017). This in turn increases investment

expenditure. Moreover, long-run aggregate supply curve represents the amount of goods and

services that an economy produces with inputs at full employment. In static AD-AS model, the

long-run supply (LRAS) curve does not shift. This implies that the economy does not experience

any growth. Moreover, it is assumed that the inflation is constant during this period. Initially,

actual GDP equates with potential GDP. However, any shock in aggregate demand can generate

economic recession or inflation. In this situation, aggregate demand curve shifts towards left or

right (Azevedo and Leshno 2016). Moreover, in both situations, firms adjust their production

level as well as price level according to this aggregate demand. It continues until potential GDP

equates with actual GDP again. For this, the model is called static

Answer to question 3:

The aggregate supply (AS) curve represents total amount of output provided by

household and firms at particular prices and wages. The aggregate demand curve is the

combinations of real income and price levels, representing equilibrium goods market. The

interest rate effect can determine this curve. This happens when a lower price level increases real

money balances and reduces the interest rate (Hsing 2017). This in turn increases investment

expenditure. Moreover, long-run aggregate supply curve represents the amount of goods and

services that an economy produces with inputs at full employment. In static AD-AS model, the

long-run supply (LRAS) curve does not shift. This implies that the economy does not experience

any growth. Moreover, it is assumed that the inflation is constant during this period. Initially,

actual GDP equates with potential GDP. However, any shock in aggregate demand can generate

economic recession or inflation. In this situation, aggregate demand curve shifts towards left or

right (Azevedo and Leshno 2016). Moreover, in both situations, firms adjust their production

level as well as price level according to this aggregate demand. It continues until potential GDP

equates with actual GDP again. For this, the model is called static

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7MACROECONOMICS

Real GDP

Price level LAS

P0

O

SRAS0

AD0

Qp

AD1

SRAS1

P1

Figure 2: Static AD-AS Model

Source: (created by author)

In above figure, Qp represents long-run equilibrium where potential GDP equates with

actual real GDP. In the given situation, Australian economy is in expansionary phase.

Consequently, aggregate demand increases and actual short-run GDP exceeds its potential GDP.

In figure, aggregate demand shifts upward from AD0 to AD1. Fort this, the economy can

experience inflation. However, to reduce this excess demand, firms can produce more output and

increase price level (Cavoli and Wilson 2015). Consequently, the short-run aggregate supply

curve also increases from SRAS0 to SRAS1. In this new equilibrium, the economy again starts

to produce same amount of output at comparatively higher price level. Hence, based on static

AD-AS model, the economy is actually experiencing stagflation where economy actually cannot

grow further though the price level increases due to increase in aggregate demand. To maintain

this inflation where further production is not possible, the economy needs to increase its interest

Real GDP

Price level LAS

P0

O

SRAS0

AD0

Qp

AD1

SRAS1

P1

Figure 2: Static AD-AS Model

Source: (created by author)

In above figure, Qp represents long-run equilibrium where potential GDP equates with

actual real GDP. In the given situation, Australian economy is in expansionary phase.

Consequently, aggregate demand increases and actual short-run GDP exceeds its potential GDP.

In figure, aggregate demand shifts upward from AD0 to AD1. Fort this, the economy can

experience inflation. However, to reduce this excess demand, firms can produce more output and

increase price level (Cavoli and Wilson 2015). Consequently, the short-run aggregate supply

curve also increases from SRAS0 to SRAS1. In this new equilibrium, the economy again starts

to produce same amount of output at comparatively higher price level. Hence, based on static

AD-AS model, the economy is actually experiencing stagflation where economy actually cannot

grow further though the price level increases due to increase in aggregate demand. To maintain

this inflation where further production is not possible, the economy needs to increase its interest

8MACROECONOMICS

rate. If the Reserve bank of Australia (RBA) cannot increase this interest rate then the price level

even increases further with no economic growth (Leduc and Liu 2016). Thus, according to

analysts, job boom in Australian market may pressurise the RBA to increase its interest rate.

However, economists suggest that RBA is not increasing its cash rate up to 2020.

rate. If the Reserve bank of Australia (RBA) cannot increase this interest rate then the price level

even increases further with no economic growth (Leduc and Liu 2016). Thus, according to

analysts, job boom in Australian market may pressurise the RBA to increase its interest rate.

However, economists suggest that RBA is not increasing its cash rate up to 2020.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9MACROECONOMICS

Price level

O Real output

Q0 Q1+

SRAS0

SRAS1

AD0

LRAS0 LRAS1

AD1

AD3

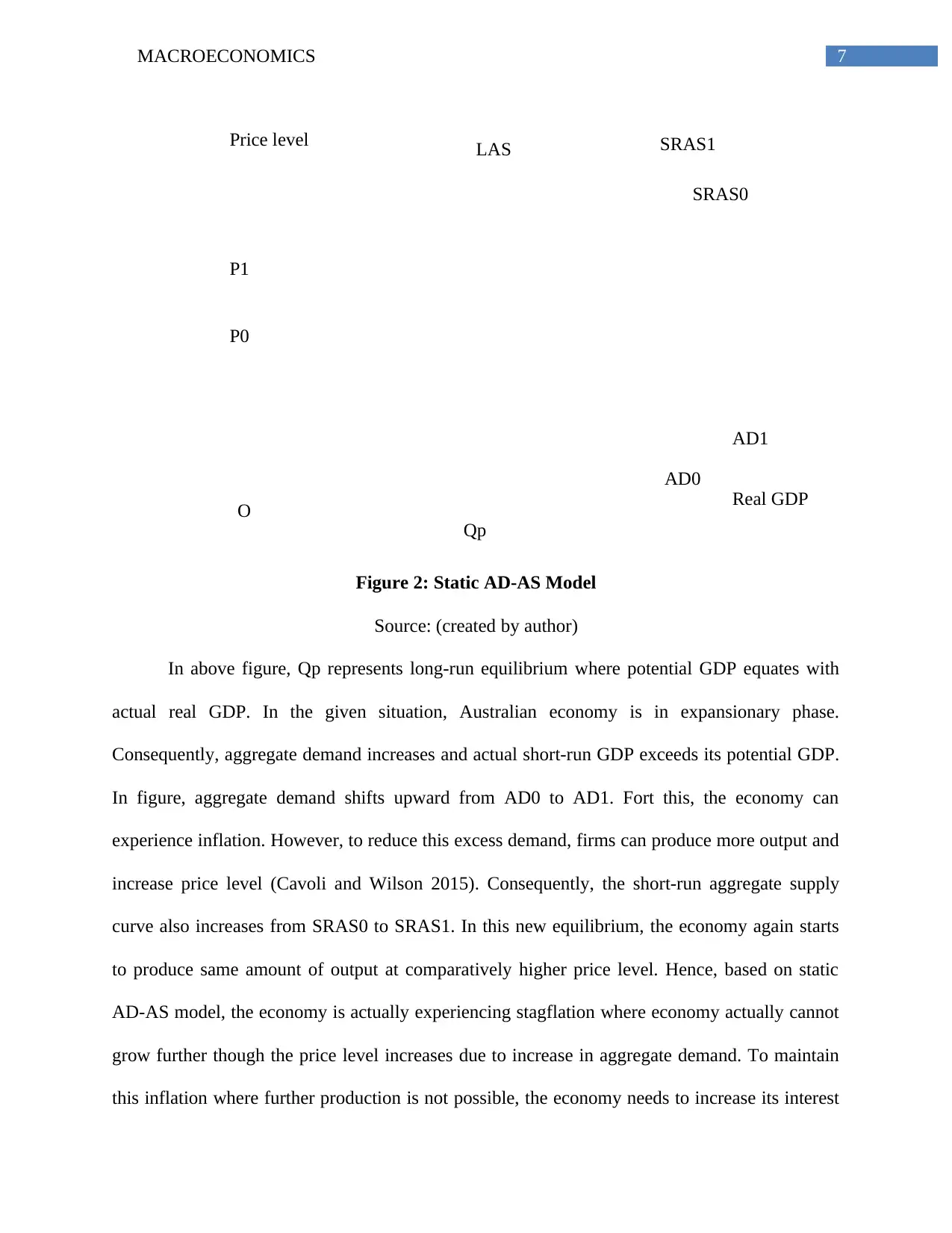

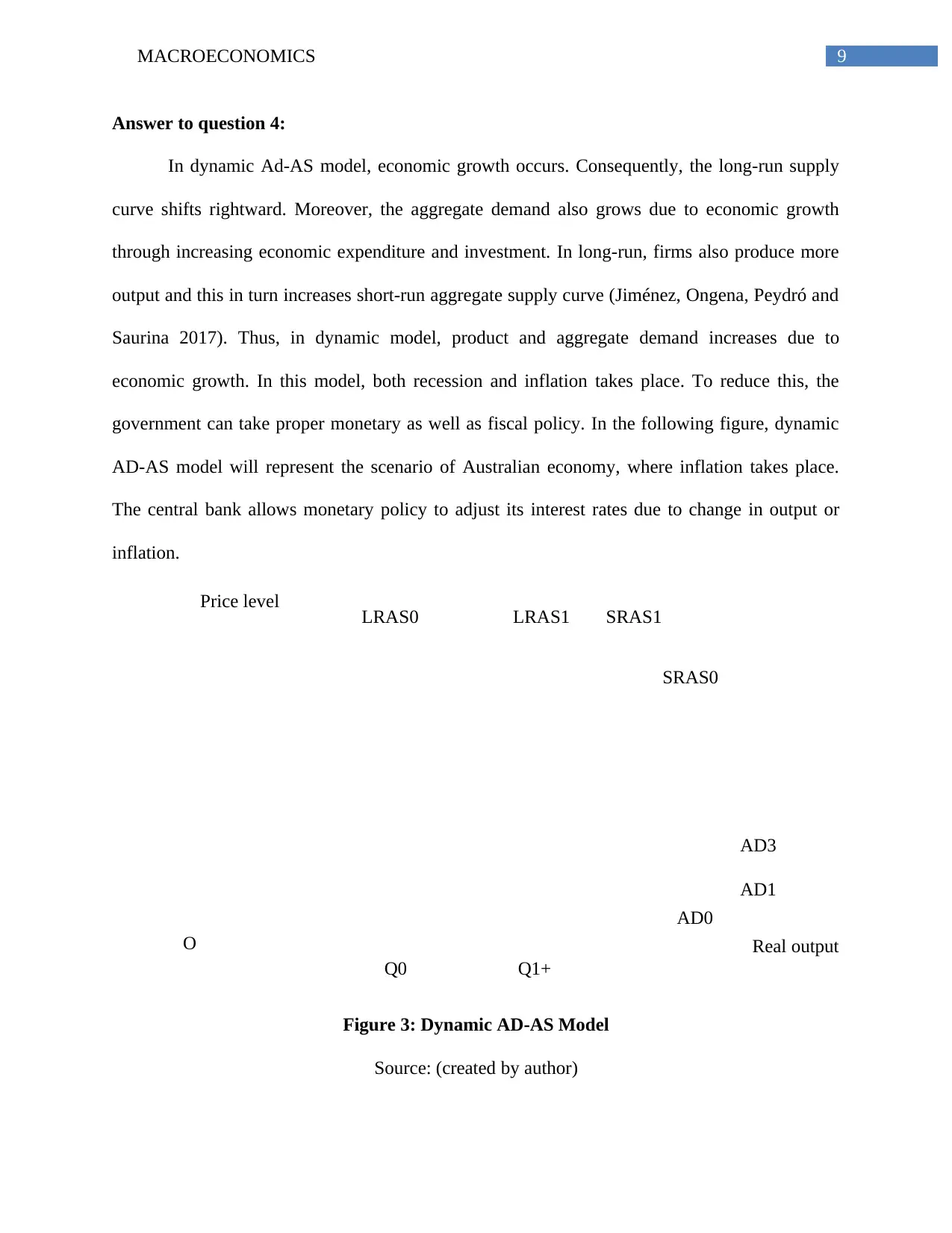

Answer to question 4:

In dynamic Ad-AS model, economic growth occurs. Consequently, the long-run supply

curve shifts rightward. Moreover, the aggregate demand also grows due to economic growth

through increasing economic expenditure and investment. In long-run, firms also produce more

output and this in turn increases short-run aggregate supply curve (Jiménez, Ongena, Peydró and

Saurina 2017). Thus, in dynamic model, product and aggregate demand increases due to

economic growth. In this model, both recession and inflation takes place. To reduce this, the

government can take proper monetary as well as fiscal policy. In the following figure, dynamic

AD-AS model will represent the scenario of Australian economy, where inflation takes place.

The central bank allows monetary policy to adjust its interest rates due to change in output or

inflation.

Figure 3: Dynamic AD-AS Model

Source: (created by author)

Price level

O Real output

Q0 Q1+

SRAS0

SRAS1

AD0

LRAS0 LRAS1

AD1

AD3

Answer to question 4:

In dynamic Ad-AS model, economic growth occurs. Consequently, the long-run supply

curve shifts rightward. Moreover, the aggregate demand also grows due to economic growth

through increasing economic expenditure and investment. In long-run, firms also produce more

output and this in turn increases short-run aggregate supply curve (Jiménez, Ongena, Peydró and

Saurina 2017). Thus, in dynamic model, product and aggregate demand increases due to

economic growth. In this model, both recession and inflation takes place. To reduce this, the

government can take proper monetary as well as fiscal policy. In the following figure, dynamic

AD-AS model will represent the scenario of Australian economy, where inflation takes place.

The central bank allows monetary policy to adjust its interest rates due to change in output or

inflation.

Figure 3: Dynamic AD-AS Model

Source: (created by author)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10MACROECONOMICS

The dynamic aggregate supply curve will shift to the right, as the Australian economy is

going to produce more goods and services. In addition to this, aggregate demand curve also

increases. Thus, the economy is producing its output and consequently aggregate demand curve

shifts from AD0 to AD1. However, due to increase in long-run aggregate supply curve, the

economy may perform at recession (Michaillat and Saez 2015). Hence, to obtain equilibrium

again, the Australian government needs to increase its aggregate demand up to AD3. To do so,

the government can take effective monetary or fiscal policy (Hubbard et al. 2014). However, the

aggregate price level will also increase and this further can cause inflation. Thus, to reduce this

situation, the RBA may increase its cash rate.

The dynamic aggregate supply curve will shift to the right, as the Australian economy is

going to produce more goods and services. In addition to this, aggregate demand curve also

increases. Thus, the economy is producing its output and consequently aggregate demand curve

shifts from AD0 to AD1. However, due to increase in long-run aggregate supply curve, the

economy may perform at recession (Michaillat and Saez 2015). Hence, to obtain equilibrium

again, the Australian government needs to increase its aggregate demand up to AD3. To do so,

the government can take effective monetary or fiscal policy (Hubbard et al. 2014). However, the

aggregate price level will also increase and this further can cause inflation. Thus, to reduce this

situation, the RBA may increase its cash rate.

11MACROECONOMICS

References:

Adelino, M., Ma, S. and Robinson, D., 2017. Firm age, investment opportunities, and job

creation. The Journal of Finance, 72(3), pp.999-1038.

Azevedo, E.M. and Leshno, J.D., 2016. A supply and demand framework for two-sided

matching markets. Journal of Political Economy, 124(5), pp.1235-1268.

Beveridge, W.H., 2014. Full Employment in a Free Society (Works of William H. Beveridge): A

Report. Routledge.

Cavoli, T. and Wilson, J.K., 2015. Corruption, central bank (in) dependence and optimal

monetary policy in a simple model. Journal of Policy Modeling, 37(3), pp.501-509.

DiMasi, J.A., Grabowski, H.G. and Hansen, R.W., 2016. Innovation in the pharmaceutical

industry: new estimates of R&D costs. Journal of health economics, 47, pp.20-33.

Elsby, M.W., Hobijn, B. and Şahin, A., 2015. On the importance of the participation margin for

labor market fluctuations. Journal of Monetary Economics, 72, pp.64-82.

Frey, C.B. and Osborne, M.A., 2017. The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to

computerisation?. Technological forecasting and social change, 114, pp.254-280.

Hsing, Y., 2017. Is Currency Depreciation or More Government Debt Expansionary? The Case

of Thailand. Journal of Advances in Economics and Finance, 2(4), p.237.

Hubbard, G., Garnett, A., Lewis, P. and O’Brien, A., 2014. Essentials of Economics. Pearson

Australia Pty Ltd

Jiménez, G., Ongena, S., Peydró, J.L. and Saurina, J., 2017. Macroprudential policy,

countercyclical bank capital buffers, and credit supply: evidence from the Spanish dynamic

provisioning experiments. Journal of Political Economy, 125(6), pp.2126-2177.

References:

Adelino, M., Ma, S. and Robinson, D., 2017. Firm age, investment opportunities, and job

creation. The Journal of Finance, 72(3), pp.999-1038.

Azevedo, E.M. and Leshno, J.D., 2016. A supply and demand framework for two-sided

matching markets. Journal of Political Economy, 124(5), pp.1235-1268.

Beveridge, W.H., 2014. Full Employment in a Free Society (Works of William H. Beveridge): A

Report. Routledge.

Cavoli, T. and Wilson, J.K., 2015. Corruption, central bank (in) dependence and optimal

monetary policy in a simple model. Journal of Policy Modeling, 37(3), pp.501-509.

DiMasi, J.A., Grabowski, H.G. and Hansen, R.W., 2016. Innovation in the pharmaceutical

industry: new estimates of R&D costs. Journal of health economics, 47, pp.20-33.

Elsby, M.W., Hobijn, B. and Şahin, A., 2015. On the importance of the participation margin for

labor market fluctuations. Journal of Monetary Economics, 72, pp.64-82.

Frey, C.B. and Osborne, M.A., 2017. The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to

computerisation?. Technological forecasting and social change, 114, pp.254-280.

Hsing, Y., 2017. Is Currency Depreciation or More Government Debt Expansionary? The Case

of Thailand. Journal of Advances in Economics and Finance, 2(4), p.237.

Hubbard, G., Garnett, A., Lewis, P. and O’Brien, A., 2014. Essentials of Economics. Pearson

Australia Pty Ltd

Jiménez, G., Ongena, S., Peydró, J.L. and Saurina, J., 2017. Macroprudential policy,

countercyclical bank capital buffers, and credit supply: evidence from the Spanish dynamic

provisioning experiments. Journal of Political Economy, 125(6), pp.2126-2177.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.