Comprehensive Economic Analysis of Japan's Performance: 2006-2016

VerifiedAdded on 2022/10/19

|13

|3156

|16

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of Japan's economic performance between 2006 and 2016, examining key macroeconomic indicators. It begins with an overview of the Japanese economy, highlighting its position in the world and its key sectors. The report then delves into production output performance, analyzing GDP, GDP growth rate, and GDP per capita, with comparisons to South Korea. The analysis includes discussions of the government's measures, particularly the 'Abenomics' policies, aimed at stimulating economic growth. The report further explores the labor market, examining unemployment trends and the government's responses to unemployment, including fiscal stimulus and initiatives to increase female employment. Finally, the report investigates price level analysis, focusing on inflation trends and the causes of deflation in Japan, including the impact of the global financial crisis and the 'lost decade.' The analysis draws on data from the World Bank and other sources, providing a detailed understanding of the economic challenges and developments in Japan during this period.

Running head: ECONOMICS

Economic Performance of Japan: 2006 - 2016

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author note:

Economic Performance of Japan: 2006 - 2016

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author note:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECONOMICS 1

1.0 Introduction

Japan is a highly developed economy of Asia as well as in the world. The

economy of Japan is a free market economy, which is 3rd biggest in the world in nominal

GDP and 4rth largest in purchasing power parity (PPP). It is also the 2nd biggest among

the most developed economies of the world (Felbermayr et al., 2017). In 2016, the

country’s GDP was 4.93 trillion a current USD, with GDP per capita being 38794.33 at

current USD (World Bank, 2019). Japan is a nation with most innovative techniques in

all types of application in personal and professional life of individuals. It has the largest

industry in electronic goods and filling of patents. Moreover, Japan holds the 3rd rank

among the biggest automobile manufacturing countries (Sawe, 2019). It is also the

largest creditor of the world with leading public debt ratio. Top 5 products and/or

services produced by the economy are automobiles, electronic goods, semiconductors,

petrochemicals and iron and steel products. The biggest industries of the Japanese

economy are manufacturing, agriculture, fishing and tourism. The service sector

contributes the maximum amount in the GDP with 71.4%, followed by the industry

sector with 27.5% and agriculture with 1.2% (Sawe, 2019). The rate of unemployment is

2.9%. As of 2018, Japan is 4th biggest exporter with exports worth of $728 billion and 4th

biggest importer with imports worth of $632 billion in the global economy. The top 5

export markets of Japan are USA (20%), China (17.55%), South Korea (7.1%), Hong

Kong (5.6%) and Thailand (4.5%). The major exports of the country consists of

automobiles, motor parts, power generating machinery, electronic goods, iron and steel

products, plastic materials and semiconductors (Sawe, 2019). According to a report by

Phillpott (2019), the top 5 biggest organizations of Japan are Toyota Motor Corporation

(biggest car manufacturer of Japan), SoftBank Group (conglomerate with businesses in

telecommunications, finance, e-commerce, media, and technology), Mitsubishi UFJ

Financial Group (banking and finance), Nippon Telegraph and Telephone

(Telecommunication Company) and Japan Post Holdings (conglomerate with

businesses in postal service, banking, logistics and insurance). This essay will highlight

the production output performance analysis, labor market analysis and price level

1.0 Introduction

Japan is a highly developed economy of Asia as well as in the world. The

economy of Japan is a free market economy, which is 3rd biggest in the world in nominal

GDP and 4rth largest in purchasing power parity (PPP). It is also the 2nd biggest among

the most developed economies of the world (Felbermayr et al., 2017). In 2016, the

country’s GDP was 4.93 trillion a current USD, with GDP per capita being 38794.33 at

current USD (World Bank, 2019). Japan is a nation with most innovative techniques in

all types of application in personal and professional life of individuals. It has the largest

industry in electronic goods and filling of patents. Moreover, Japan holds the 3rd rank

among the biggest automobile manufacturing countries (Sawe, 2019). It is also the

largest creditor of the world with leading public debt ratio. Top 5 products and/or

services produced by the economy are automobiles, electronic goods, semiconductors,

petrochemicals and iron and steel products. The biggest industries of the Japanese

economy are manufacturing, agriculture, fishing and tourism. The service sector

contributes the maximum amount in the GDP with 71.4%, followed by the industry

sector with 27.5% and agriculture with 1.2% (Sawe, 2019). The rate of unemployment is

2.9%. As of 2018, Japan is 4th biggest exporter with exports worth of $728 billion and 4th

biggest importer with imports worth of $632 billion in the global economy. The top 5

export markets of Japan are USA (20%), China (17.55%), South Korea (7.1%), Hong

Kong (5.6%) and Thailand (4.5%). The major exports of the country consists of

automobiles, motor parts, power generating machinery, electronic goods, iron and steel

products, plastic materials and semiconductors (Sawe, 2019). According to a report by

Phillpott (2019), the top 5 biggest organizations of Japan are Toyota Motor Corporation

(biggest car manufacturer of Japan), SoftBank Group (conglomerate with businesses in

telecommunications, finance, e-commerce, media, and technology), Mitsubishi UFJ

Financial Group (banking and finance), Nippon Telegraph and Telephone

(Telecommunication Company) and Japan Post Holdings (conglomerate with

businesses in postal service, banking, logistics and insurance). This essay will highlight

the production output performance analysis, labor market analysis and price level

2ECONOMICS

analysis of Japan along with a discussion on the government measures taken to

address the situations.

2.0 Production Output Performance Analysis

2.1 GDP

GDP or Gross Domestic Product is referred to the monetary value of the total

output produced within the geographical boundary of a nation in a given time period,

mostly a financial year (Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2015). It is the best measure of a country’s

economic health. Japan has been experiencing high GDP for almost a decade due to

advanced technology and high level manufacturing and within 2006 and 2016, it

achieved highest GDP of 6.2 trillion USD in 2012 while in 2015, it experienced lowest

GDP of 4.39 trillion USD (World Bank, 2019).

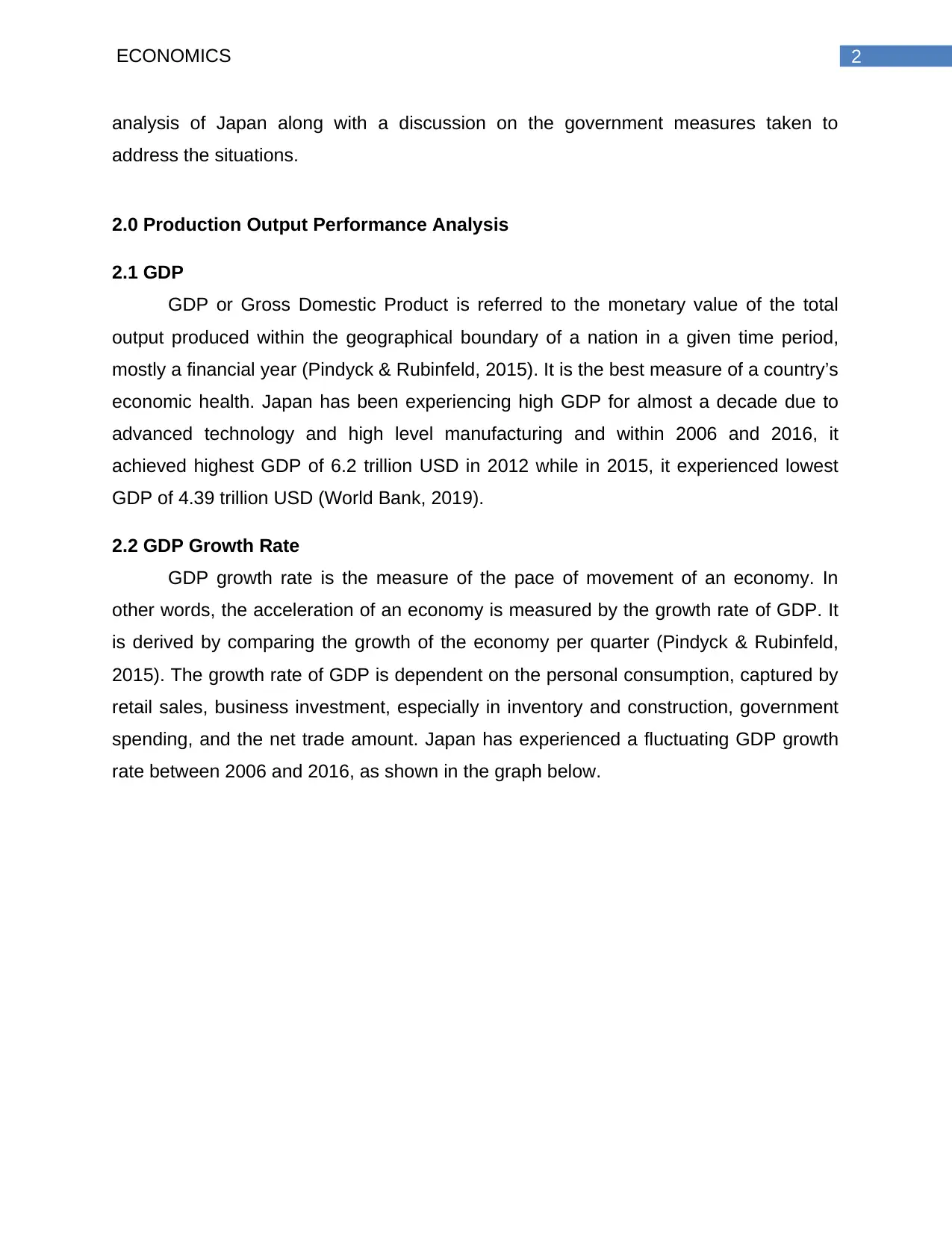

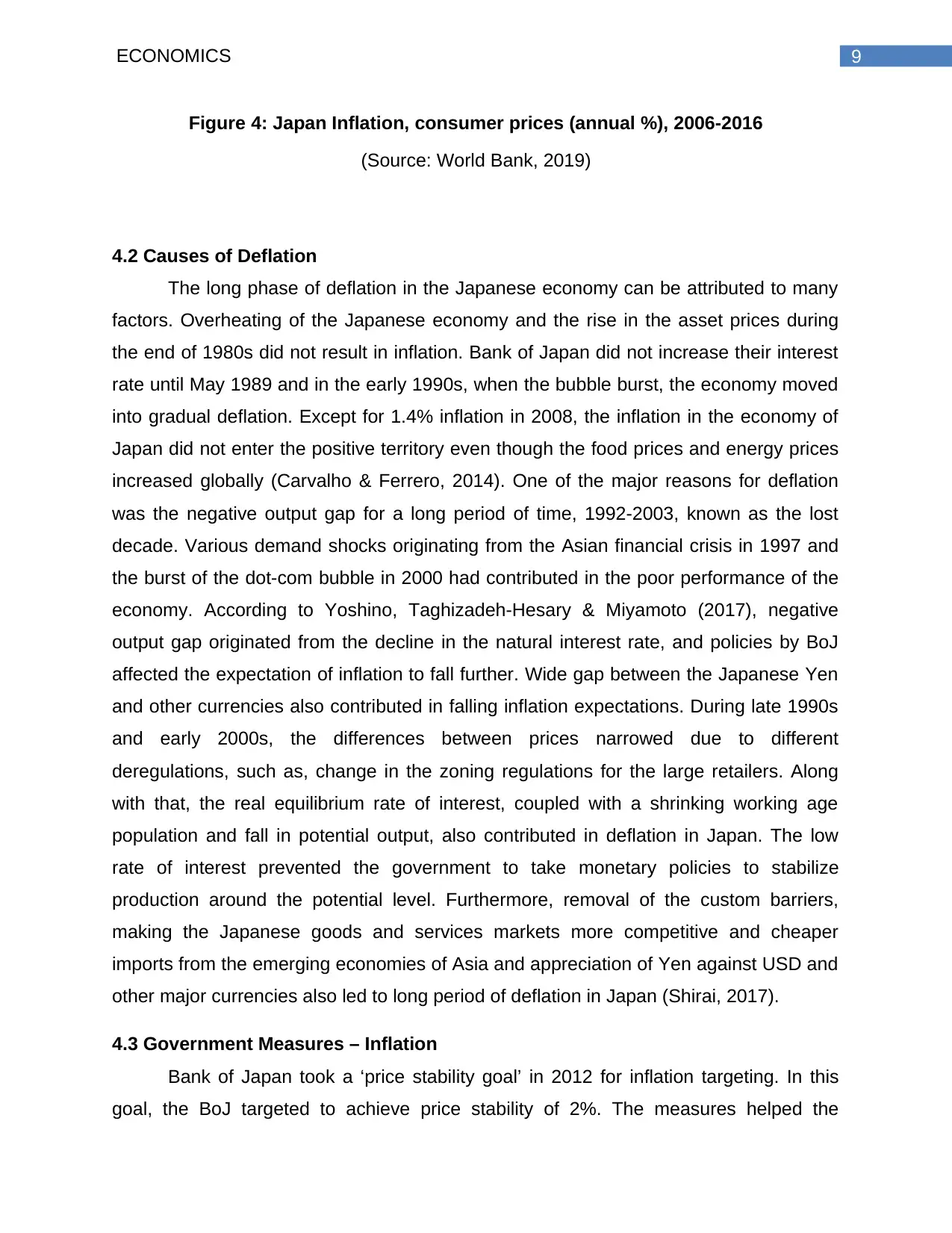

2.2 GDP Growth Rate

GDP growth rate is the measure of the pace of movement of an economy. In

other words, the acceleration of an economy is measured by the growth rate of GDP. It

is derived by comparing the growth of the economy per quarter (Pindyck & Rubinfeld,

2015). The growth rate of GDP is dependent on the personal consumption, captured by

retail sales, business investment, especially in inventory and construction, government

spending, and the net trade amount. Japan has experienced a fluctuating GDP growth

rate between 2006 and 2016, as shown in the graph below.

analysis of Japan along with a discussion on the government measures taken to

address the situations.

2.0 Production Output Performance Analysis

2.1 GDP

GDP or Gross Domestic Product is referred to the monetary value of the total

output produced within the geographical boundary of a nation in a given time period,

mostly a financial year (Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2015). It is the best measure of a country’s

economic health. Japan has been experiencing high GDP for almost a decade due to

advanced technology and high level manufacturing and within 2006 and 2016, it

achieved highest GDP of 6.2 trillion USD in 2012 while in 2015, it experienced lowest

GDP of 4.39 trillion USD (World Bank, 2019).

2.2 GDP Growth Rate

GDP growth rate is the measure of the pace of movement of an economy. In

other words, the acceleration of an economy is measured by the growth rate of GDP. It

is derived by comparing the growth of the economy per quarter (Pindyck & Rubinfeld,

2015). The growth rate of GDP is dependent on the personal consumption, captured by

retail sales, business investment, especially in inventory and construction, government

spending, and the net trade amount. Japan has experienced a fluctuating GDP growth

rate between 2006 and 2016, as shown in the graph below.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3ECONOMICS

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

-6.00

-4.00

-2.00

0.00

2.00

4.00

6.00

1.42 1.65

-1.09

-5.42

4.19

-0.12

1.50 2.00

0.37

1.22

0.61

GDP Growth rate of Japan(%),

2006-2016

Figure 1: GDP growth rate of Japan (2006-2016)

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

It is observed that economy of Japan experienced a huge fall during 2008-09

when the growth rate became highly negative. During the global financial crisis, the

export of Japan shrank 26% and the consumers and businesses went for spending

cuts. Business investment fell by 10.4% and consumer expenditure fell by 1.1%. There

was wage cut also followed by increasing unemployment (McCurry, 2009). However,

the country bounced back in 2010 with a sharp increase in the GDP growth rate due to

strong capital spending. However, the growth fell again 2011 due to the massive impact

of earthquake and tsunami and after recovery in the subsequent years, it has been

experiencing a positive and moderate growth rate.

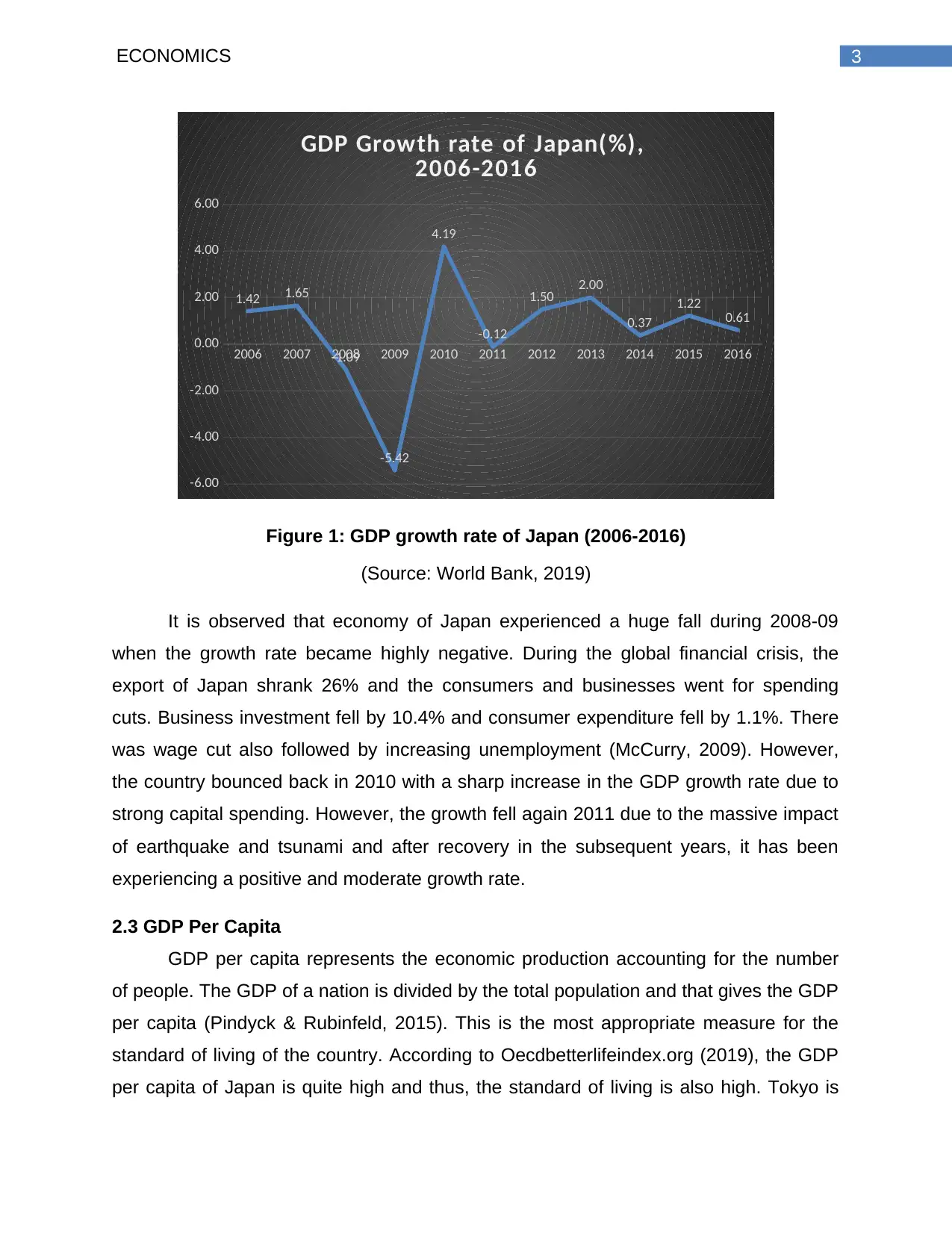

2.3 GDP Per Capita

GDP per capita represents the economic production accounting for the number

of people. The GDP of a nation is divided by the total population and that gives the GDP

per capita (Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2015). This is the most appropriate measure for the

standard of living of the country. According to Oecdbetterlifeindex.org (2019), the GDP

per capita of Japan is quite high and thus, the standard of living is also high. Tokyo is

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

-6.00

-4.00

-2.00

0.00

2.00

4.00

6.00

1.42 1.65

-1.09

-5.42

4.19

-0.12

1.50 2.00

0.37

1.22

0.61

GDP Growth rate of Japan(%),

2006-2016

Figure 1: GDP growth rate of Japan (2006-2016)

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

It is observed that economy of Japan experienced a huge fall during 2008-09

when the growth rate became highly negative. During the global financial crisis, the

export of Japan shrank 26% and the consumers and businesses went for spending

cuts. Business investment fell by 10.4% and consumer expenditure fell by 1.1%. There

was wage cut also followed by increasing unemployment (McCurry, 2009). However,

the country bounced back in 2010 with a sharp increase in the GDP growth rate due to

strong capital spending. However, the growth fell again 2011 due to the massive impact

of earthquake and tsunami and after recovery in the subsequent years, it has been

experiencing a positive and moderate growth rate.

2.3 GDP Per Capita

GDP per capita represents the economic production accounting for the number

of people. The GDP of a nation is divided by the total population and that gives the GDP

per capita (Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2015). This is the most appropriate measure for the

standard of living of the country. According to Oecdbetterlifeindex.org (2019), the GDP

per capita of Japan is quite high and thus, the standard of living is also high. Tokyo is

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4ECONOMICS

the most expensive city of the world and it implies that the cost of living in Japan is

extremely high (Sakai, Kawamura & Hyodo, 2015).

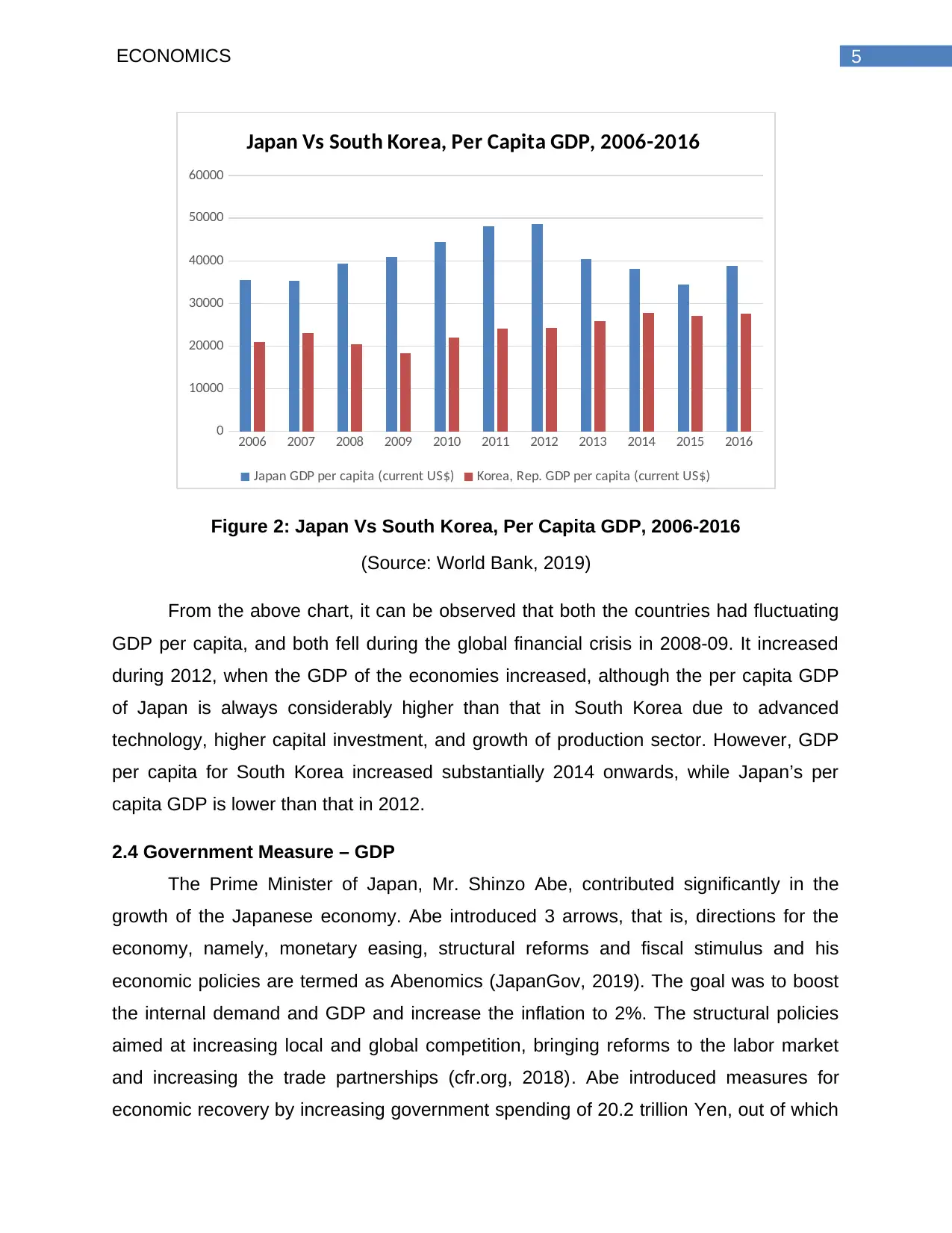

When compared the GDP per capita of Japan with that of South Korea, it can be

observed that it is quite low for South Korea between 2006 and 2016.

Japan Vs. South Korea: GDP per capita (current US$)

Japan Korea, Rep.

2006 35433.99 20888.38

2007 35275.23 23060.71

2008 39339.30 20430.64

2009 40855.18 18291.92

2010 44507.68 22086.95

2011 48168.00 24079.79

2012 48603.48 24358.78

2013 40454.45 25890.02

2014 38109.41 27811.37

2015 34524.47 27105.08

2016 38794.33 27608.25

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

the most expensive city of the world and it implies that the cost of living in Japan is

extremely high (Sakai, Kawamura & Hyodo, 2015).

When compared the GDP per capita of Japan with that of South Korea, it can be

observed that it is quite low for South Korea between 2006 and 2016.

Japan Vs. South Korea: GDP per capita (current US$)

Japan Korea, Rep.

2006 35433.99 20888.38

2007 35275.23 23060.71

2008 39339.30 20430.64

2009 40855.18 18291.92

2010 44507.68 22086.95

2011 48168.00 24079.79

2012 48603.48 24358.78

2013 40454.45 25890.02

2014 38109.41 27811.37

2015 34524.47 27105.08

2016 38794.33 27608.25

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

5ECONOMICS

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

0

10000

20000

30000

40000

50000

60000

Japan Vs South Korea, Per Capita GDP, 2006-2016

Japan GDP per capita (current US$) Korea, Rep. GDP per capita (current US$)

Figure 2: Japan Vs South Korea, Per Capita GDP, 2006-2016

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

From the above chart, it can be observed that both the countries had fluctuating

GDP per capita, and both fell during the global financial crisis in 2008-09. It increased

during 2012, when the GDP of the economies increased, although the per capita GDP

of Japan is always considerably higher than that in South Korea due to advanced

technology, higher capital investment, and growth of production sector. However, GDP

per capita for South Korea increased substantially 2014 onwards, while Japan’s per

capita GDP is lower than that in 2012.

2.4 Government Measure – GDP

The Prime Minister of Japan, Mr. Shinzo Abe, contributed significantly in the

growth of the Japanese economy. Abe introduced 3 arrows, that is, directions for the

economy, namely, monetary easing, structural reforms and fiscal stimulus and his

economic policies are termed as Abenomics (JapanGov, 2019). The goal was to boost

the internal demand and GDP and increase the inflation to 2%. The structural policies

aimed at increasing local and global competition, bringing reforms to the labor market

and increasing the trade partnerships (cfr.org, 2018). Abe introduced measures for

economic recovery by increasing government spending of 20.2 trillion Yen, out of which

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

0

10000

20000

30000

40000

50000

60000

Japan Vs South Korea, Per Capita GDP, 2006-2016

Japan GDP per capita (current US$) Korea, Rep. GDP per capita (current US$)

Figure 2: Japan Vs South Korea, Per Capita GDP, 2006-2016

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

From the above chart, it can be observed that both the countries had fluctuating

GDP per capita, and both fell during the global financial crisis in 2008-09. It increased

during 2012, when the GDP of the economies increased, although the per capita GDP

of Japan is always considerably higher than that in South Korea due to advanced

technology, higher capital investment, and growth of production sector. However, GDP

per capita for South Korea increased substantially 2014 onwards, while Japan’s per

capita GDP is lower than that in 2012.

2.4 Government Measure – GDP

The Prime Minister of Japan, Mr. Shinzo Abe, contributed significantly in the

growth of the Japanese economy. Abe introduced 3 arrows, that is, directions for the

economy, namely, monetary easing, structural reforms and fiscal stimulus and his

economic policies are termed as Abenomics (JapanGov, 2019). The goal was to boost

the internal demand and GDP and increase the inflation to 2%. The structural policies

aimed at increasing local and global competition, bringing reforms to the labor market

and increasing the trade partnerships (cfr.org, 2018). Abe introduced measures for

economic recovery by increasing government spending of 20.2 trillion Yen, out of which

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6ECONOMICS

10.3 trillion was direct government spending. Infrastructure was developed and

monetary policy was eased out to stimulate the GDP (JapanGov, 2019).

3.0 Labour Market Analysis

3.1 Types of Unemployment

Unemployment is that state of an economy, in which an individual is willing to

work but cannot find or do not have a job. Rate of unemployment is the measure of

unemployment, which is a percentage of unemployed people divided by total population

(Ezzy, 2017). Unemployment is of three types, structural, cyclical and frictional.

Structural unemployment emerges from the structural changes in an economy,

such as, change of technologies. Some people cannot adapt and leave jobs, while

some lose their jobs as they are unable to learn new technology and thus, structural

unemployment is generated. Cyclical unemployment occurs with economic cycle, that

is, when there is contraction, the market demand falls, and unemployment increases,

and the opposite happens in case of economic expansion. Lastly, frictional

unemployment represents the mismatch between the job requirement and skills and

knowledge of the potential employees. Such unemployment always exists to a certain

extent in all the economies (Murtin & Robin, 2018). Japan has faced structural

unemployment over the years due to the structural reforms introduced by the

government.

10.3 trillion was direct government spending. Infrastructure was developed and

monetary policy was eased out to stimulate the GDP (JapanGov, 2019).

3.0 Labour Market Analysis

3.1 Types of Unemployment

Unemployment is that state of an economy, in which an individual is willing to

work but cannot find or do not have a job. Rate of unemployment is the measure of

unemployment, which is a percentage of unemployed people divided by total population

(Ezzy, 2017). Unemployment is of three types, structural, cyclical and frictional.

Structural unemployment emerges from the structural changes in an economy,

such as, change of technologies. Some people cannot adapt and leave jobs, while

some lose their jobs as they are unable to learn new technology and thus, structural

unemployment is generated. Cyclical unemployment occurs with economic cycle, that

is, when there is contraction, the market demand falls, and unemployment increases,

and the opposite happens in case of economic expansion. Lastly, frictional

unemployment represents the mismatch between the job requirement and skills and

knowledge of the potential employees. Such unemployment always exists to a certain

extent in all the economies (Murtin & Robin, 2018). Japan has faced structural

unemployment over the years due to the structural reforms introduced by the

government.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7ECONOMICS

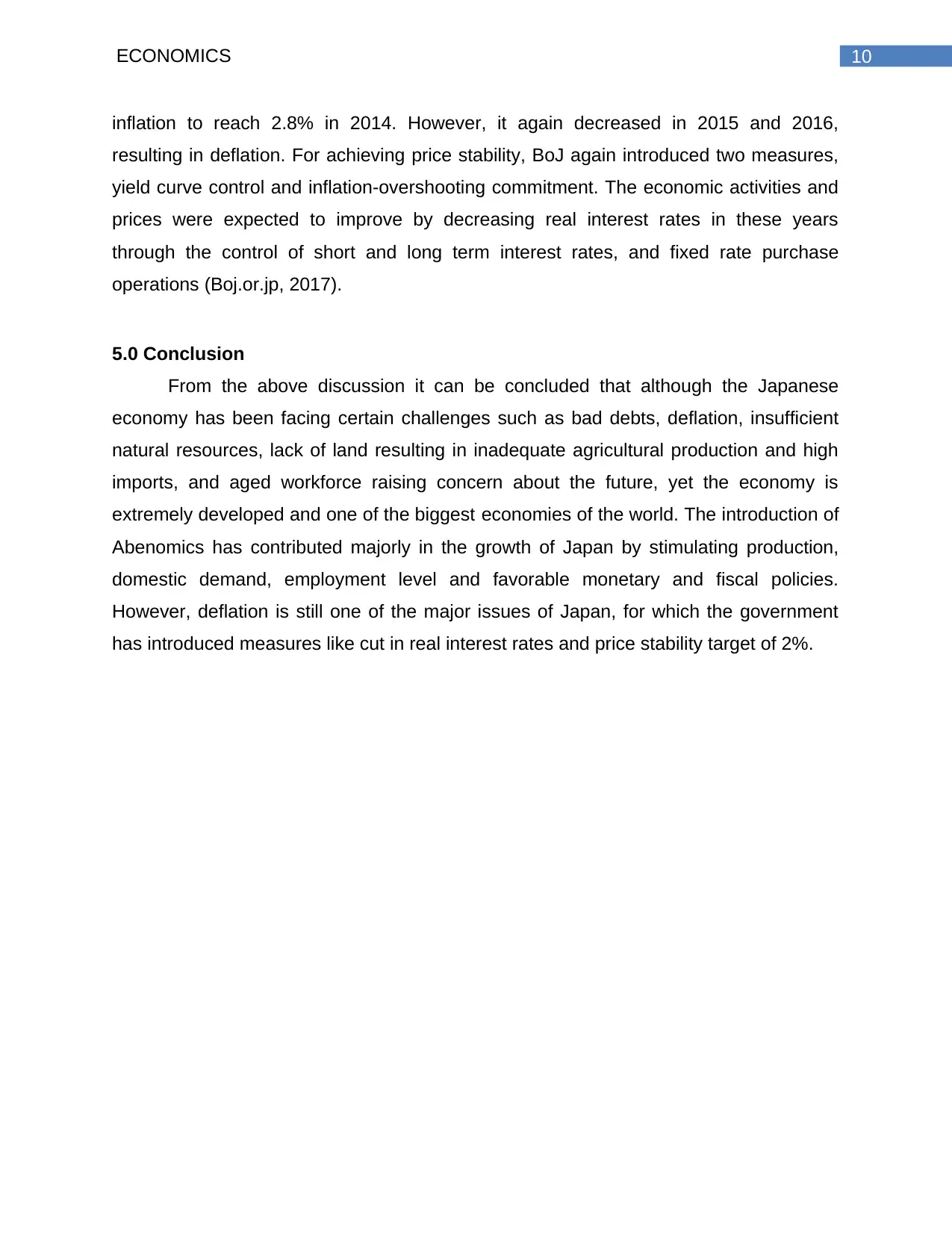

3.2 Unemployment Trend

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0.0 1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0

4.1

3.9

4.0

5.1

5.1

4.5

4.3

4.0

3.6

3.4

3.1

Unemployment trend in Japan (%),

2006-2016

Figure 3: Unemployment trend in Japan (%), 2006-2016

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

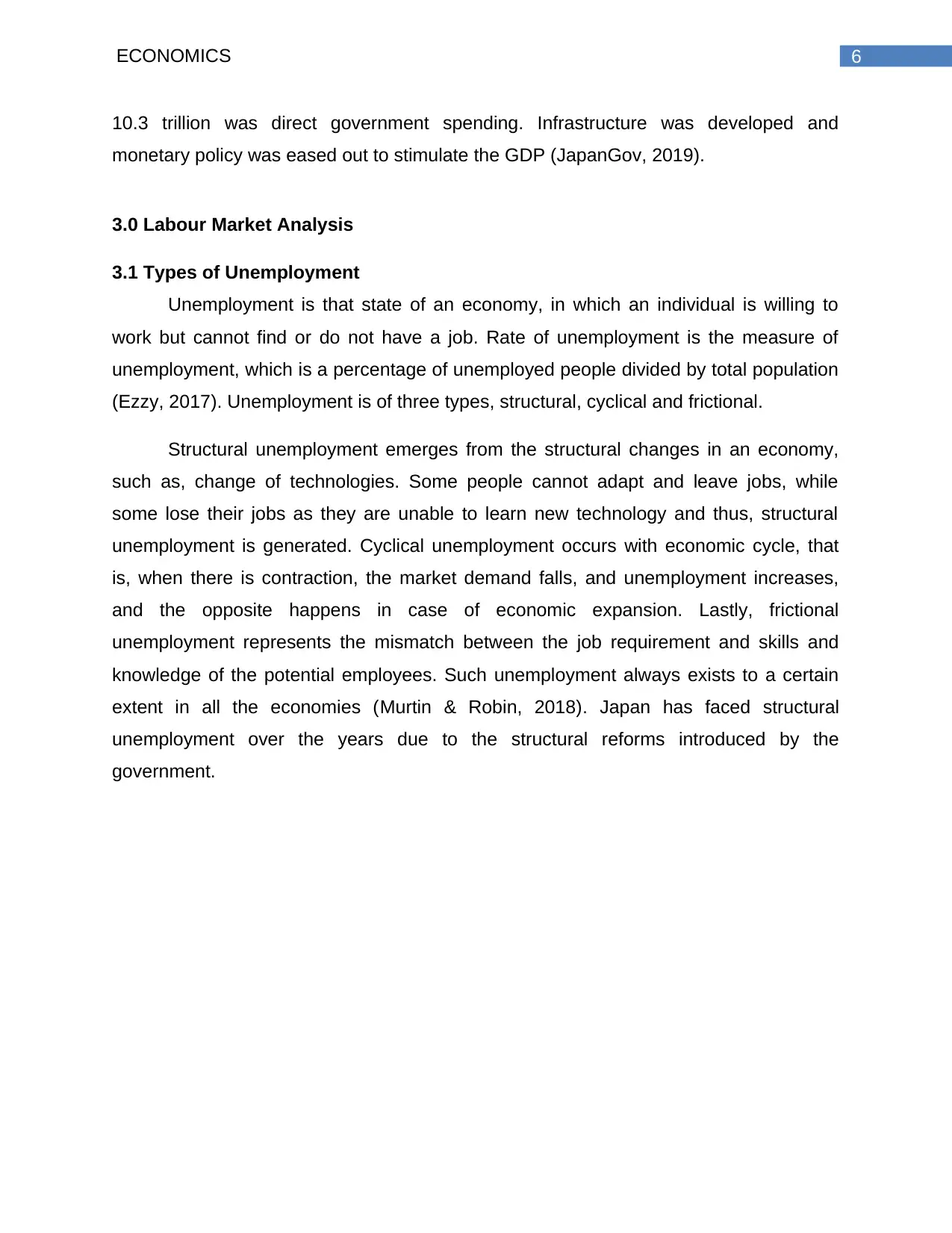

Japan has the lowest unemployment rate among all the OECD countries (Kondo,

2015). In the years between 2006 and 2016, Japan has experienced a positive and

moderate unemployment. During 2009-10, the rate of unemployment was highest and

reached 5.1% when the economy shrank as a resultant effect of global financial crisis.

2011 onwards, the level of unemployment decreased and it was lowest in 2016 at 3.1%.

Growth in the manufacturing and technology sectors have contributed in increasing

number of jobs in Japan resulting in lower unemployment rate. Along with that, shrinking

labor force, and shortage of skilled and unskilled workers in the healthcare, hospitality

and construction industry are also reasons for lower unemployment in Japan

(japantimes.co.jp, 2016).

3.3 Government Measures – Unemployment

Shinzo Abe has taken measures to tighten the labor market through fiscal

stimulus and that has lowered the unemployment rate to the lowest among all the

OECD countries. The direct government spending of 10.3 trillion Yen on public works,

small businesses and in military helped to boost the employment. Increase in the

3.2 Unemployment Trend

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

0.0 1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0

4.1

3.9

4.0

5.1

5.1

4.5

4.3

4.0

3.6

3.4

3.1

Unemployment trend in Japan (%),

2006-2016

Figure 3: Unemployment trend in Japan (%), 2006-2016

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

Japan has the lowest unemployment rate among all the OECD countries (Kondo,

2015). In the years between 2006 and 2016, Japan has experienced a positive and

moderate unemployment. During 2009-10, the rate of unemployment was highest and

reached 5.1% when the economy shrank as a resultant effect of global financial crisis.

2011 onwards, the level of unemployment decreased and it was lowest in 2016 at 3.1%.

Growth in the manufacturing and technology sectors have contributed in increasing

number of jobs in Japan resulting in lower unemployment rate. Along with that, shrinking

labor force, and shortage of skilled and unskilled workers in the healthcare, hospitality

and construction industry are also reasons for lower unemployment in Japan

(japantimes.co.jp, 2016).

3.3 Government Measures – Unemployment

Shinzo Abe has taken measures to tighten the labor market through fiscal

stimulus and that has lowered the unemployment rate to the lowest among all the

OECD countries. The direct government spending of 10.3 trillion Yen on public works,

small businesses and in military helped to boost the employment. Increase in the

8ECONOMICS

spending helped to create demand in the economy and that reduced the level of

unemployment. Abe also introduced “womenomics” initiative in 2013 and that surged

the female employment to 70.1% in 2015 (Sposato, 2015). Shrinking working age

population is a great challenge for Japan and increasing women participation in the

labor force has mitigated the impact of the issue. Moreover, the companies adopted

capitalism and introduced two types of development, performance related pay and non-

regular employment, for example, temporary, part-time, and hiring through the HR

agencies to reduce the level of unemployment (JapanGov, 2019).

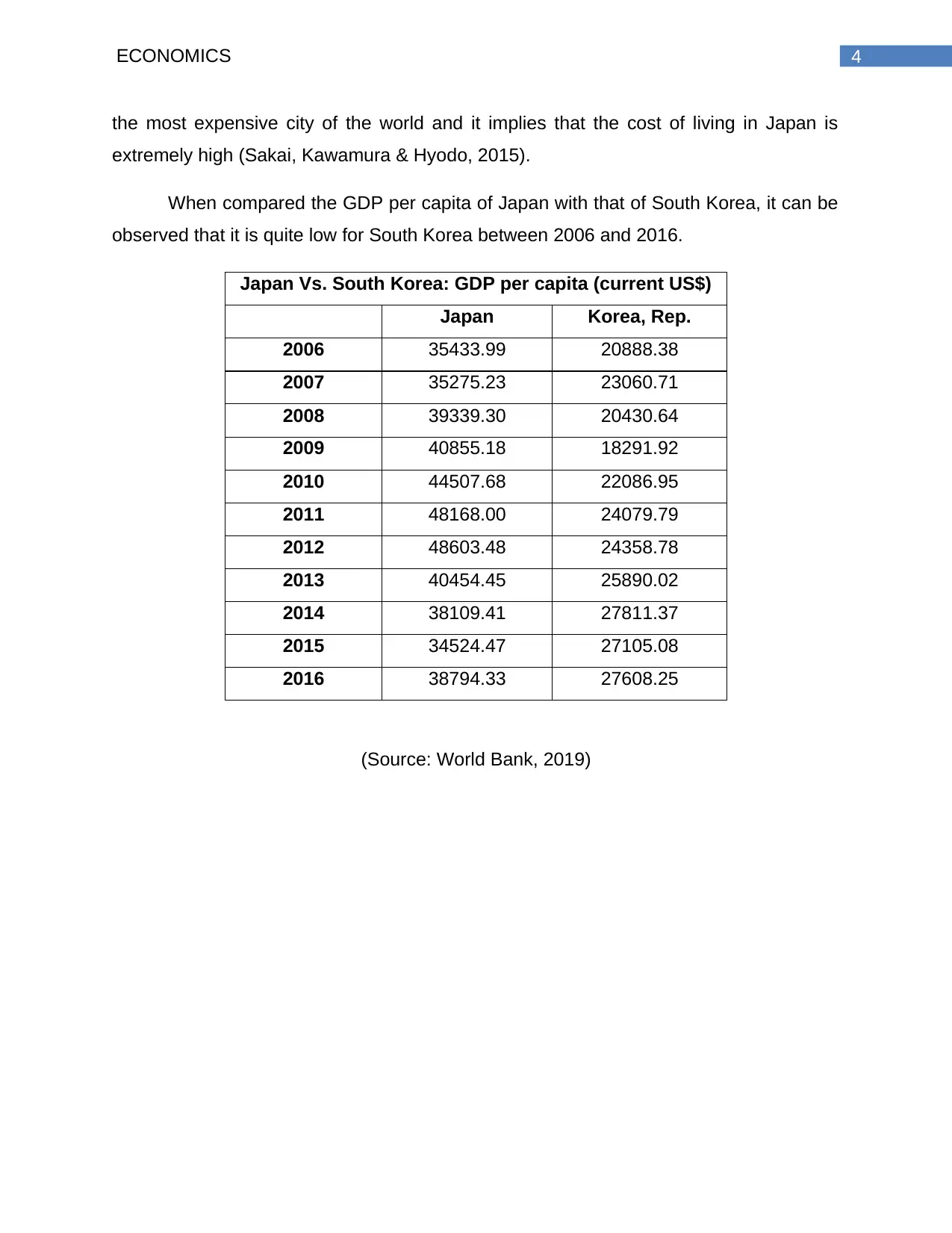

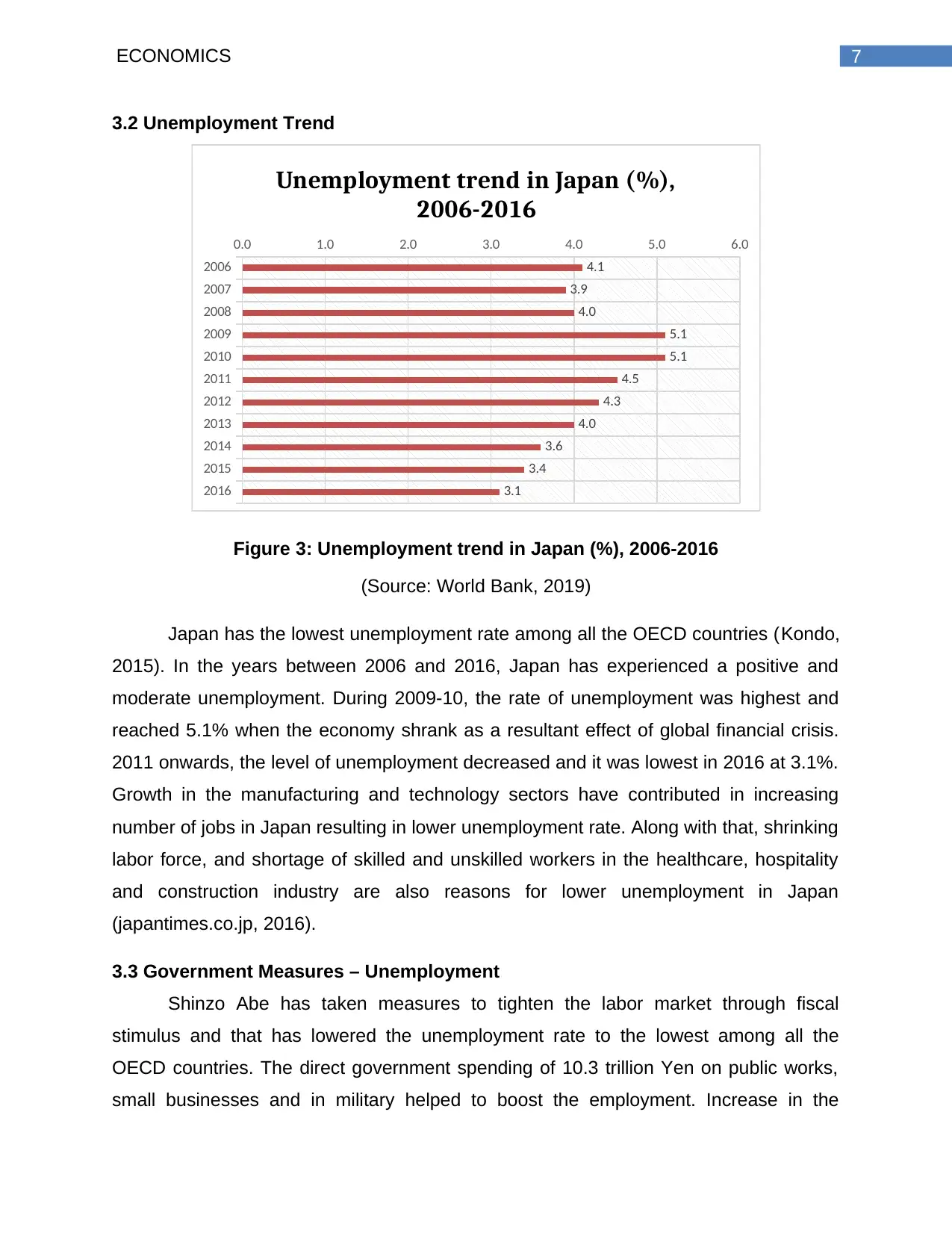

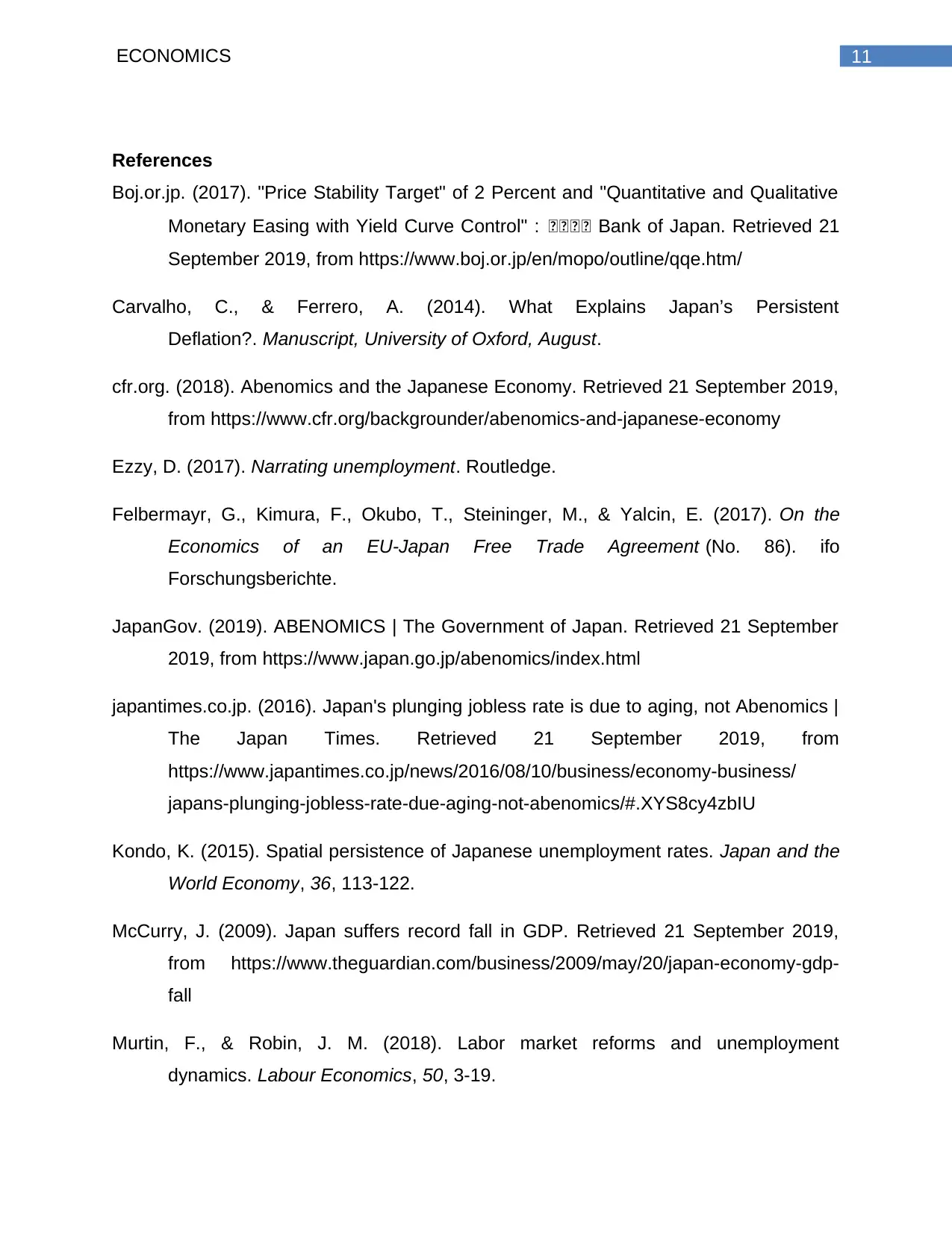

4.0 Price Level Analysis

4.1 Inflation Trend

Inflation is referred to as the increase in the overall price level of an economy

(Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2015). It is measured by the rate of fluctuations in the level of

price in the economy over time. As seen from the chart below, it can be said that the

Japanese economy mostly experienced negative inflation between 2006 and 2016.

Rate of inflation reached 2.8% in 2014 while it was -1.4% in 2009. The economy has

been facing the challenge of long standing deflation. The price level rose in 2012 after

the Abe government took over.

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

0.2 0.1

1.4

-1.4

-0.7

-0.3 -0.1

0.3

2.8

0.8

-0.1

Japan Infl ati on, consume r prices (annual %),

2006-2016

spending helped to create demand in the economy and that reduced the level of

unemployment. Abe also introduced “womenomics” initiative in 2013 and that surged

the female employment to 70.1% in 2015 (Sposato, 2015). Shrinking working age

population is a great challenge for Japan and increasing women participation in the

labor force has mitigated the impact of the issue. Moreover, the companies adopted

capitalism and introduced two types of development, performance related pay and non-

regular employment, for example, temporary, part-time, and hiring through the HR

agencies to reduce the level of unemployment (JapanGov, 2019).

4.0 Price Level Analysis

4.1 Inflation Trend

Inflation is referred to as the increase in the overall price level of an economy

(Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2015). It is measured by the rate of fluctuations in the level of

price in the economy over time. As seen from the chart below, it can be said that the

Japanese economy mostly experienced negative inflation between 2006 and 2016.

Rate of inflation reached 2.8% in 2014 while it was -1.4% in 2009. The economy has

been facing the challenge of long standing deflation. The price level rose in 2012 after

the Abe government took over.

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

0.2 0.1

1.4

-1.4

-0.7

-0.3 -0.1

0.3

2.8

0.8

-0.1

Japan Infl ati on, consume r prices (annual %),

2006-2016

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9ECONOMICS

Figure 4: Japan Inflation, consumer prices (annual %), 2006-2016

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

4.2 Causes of Deflation

The long phase of deflation in the Japanese economy can be attributed to many

factors. Overheating of the Japanese economy and the rise in the asset prices during

the end of 1980s did not result in inflation. Bank of Japan did not increase their interest

rate until May 1989 and in the early 1990s, when the bubble burst, the economy moved

into gradual deflation. Except for 1.4% inflation in 2008, the inflation in the economy of

Japan did not enter the positive territory even though the food prices and energy prices

increased globally (Carvalho & Ferrero, 2014). One of the major reasons for deflation

was the negative output gap for a long period of time, 1992-2003, known as the lost

decade. Various demand shocks originating from the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and

the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000 had contributed in the poor performance of the

economy. According to Yoshino, Taghizadeh-Hesary & Miyamoto (2017), negative

output gap originated from the decline in the natural interest rate, and policies by BoJ

affected the expectation of inflation to fall further. Wide gap between the Japanese Yen

and other currencies also contributed in falling inflation expectations. During late 1990s

and early 2000s, the differences between prices narrowed due to different

deregulations, such as, change in the zoning regulations for the large retailers. Along

with that, the real equilibrium rate of interest, coupled with a shrinking working age

population and fall in potential output, also contributed in deflation in Japan. The low

rate of interest prevented the government to take monetary policies to stabilize

production around the potential level. Furthermore, removal of the custom barriers,

making the Japanese goods and services markets more competitive and cheaper

imports from the emerging economies of Asia and appreciation of Yen against USD and

other major currencies also led to long period of deflation in Japan (Shirai, 2017).

4.3 Government Measures – Inflation

Bank of Japan took a ‘price stability goal’ in 2012 for inflation targeting. In this

goal, the BoJ targeted to achieve price stability of 2%. The measures helped the

Figure 4: Japan Inflation, consumer prices (annual %), 2006-2016

(Source: World Bank, 2019)

4.2 Causes of Deflation

The long phase of deflation in the Japanese economy can be attributed to many

factors. Overheating of the Japanese economy and the rise in the asset prices during

the end of 1980s did not result in inflation. Bank of Japan did not increase their interest

rate until May 1989 and in the early 1990s, when the bubble burst, the economy moved

into gradual deflation. Except for 1.4% inflation in 2008, the inflation in the economy of

Japan did not enter the positive territory even though the food prices and energy prices

increased globally (Carvalho & Ferrero, 2014). One of the major reasons for deflation

was the negative output gap for a long period of time, 1992-2003, known as the lost

decade. Various demand shocks originating from the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and

the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000 had contributed in the poor performance of the

economy. According to Yoshino, Taghizadeh-Hesary & Miyamoto (2017), negative

output gap originated from the decline in the natural interest rate, and policies by BoJ

affected the expectation of inflation to fall further. Wide gap between the Japanese Yen

and other currencies also contributed in falling inflation expectations. During late 1990s

and early 2000s, the differences between prices narrowed due to different

deregulations, such as, change in the zoning regulations for the large retailers. Along

with that, the real equilibrium rate of interest, coupled with a shrinking working age

population and fall in potential output, also contributed in deflation in Japan. The low

rate of interest prevented the government to take monetary policies to stabilize

production around the potential level. Furthermore, removal of the custom barriers,

making the Japanese goods and services markets more competitive and cheaper

imports from the emerging economies of Asia and appreciation of Yen against USD and

other major currencies also led to long period of deflation in Japan (Shirai, 2017).

4.3 Government Measures – Inflation

Bank of Japan took a ‘price stability goal’ in 2012 for inflation targeting. In this

goal, the BoJ targeted to achieve price stability of 2%. The measures helped the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10ECONOMICS

inflation to reach 2.8% in 2014. However, it again decreased in 2015 and 2016,

resulting in deflation. For achieving price stability, BoJ again introduced two measures,

yield curve control and inflation-overshooting commitment. The economic activities and

prices were expected to improve by decreasing real interest rates in these years

through the control of short and long term interest rates, and fixed rate purchase

operations (Boj.or.jp, 2017).

5.0 Conclusion

From the above discussion it can be concluded that although the Japanese

economy has been facing certain challenges such as bad debts, deflation, insufficient

natural resources, lack of land resulting in inadequate agricultural production and high

imports, and aged workforce raising concern about the future, yet the economy is

extremely developed and one of the biggest economies of the world. The introduction of

Abenomics has contributed majorly in the growth of Japan by stimulating production,

domestic demand, employment level and favorable monetary and fiscal policies.

However, deflation is still one of the major issues of Japan, for which the government

has introduced measures like cut in real interest rates and price stability target of 2%.

inflation to reach 2.8% in 2014. However, it again decreased in 2015 and 2016,

resulting in deflation. For achieving price stability, BoJ again introduced two measures,

yield curve control and inflation-overshooting commitment. The economic activities and

prices were expected to improve by decreasing real interest rates in these years

through the control of short and long term interest rates, and fixed rate purchase

operations (Boj.or.jp, 2017).

5.0 Conclusion

From the above discussion it can be concluded that although the Japanese

economy has been facing certain challenges such as bad debts, deflation, insufficient

natural resources, lack of land resulting in inadequate agricultural production and high

imports, and aged workforce raising concern about the future, yet the economy is

extremely developed and one of the biggest economies of the world. The introduction of

Abenomics has contributed majorly in the growth of Japan by stimulating production,

domestic demand, employment level and favorable monetary and fiscal policies.

However, deflation is still one of the major issues of Japan, for which the government

has introduced measures like cut in real interest rates and price stability target of 2%.

11ECONOMICS

References

Boj.or.jp. (2017). "Price Stability Target" of 2 Percent and "Quantitative and Qualitative

Monetary Easing with Yield Curve Control" : 日日日日 Bank of Japan. Retrieved 21

September 2019, from https://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/outline/qqe.htm/

Carvalho, C., & Ferrero, A. (2014). What Explains Japan’s Persistent

Deflation?. Manuscript, University of Oxford, August.

cfr.org. (2018). Abenomics and the Japanese Economy. Retrieved 21 September 2019,

from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/abenomics-and-japanese-economy

Ezzy, D. (2017). Narrating unemployment. Routledge.

Felbermayr, G., Kimura, F., Okubo, T., Steininger, M., & Yalcin, E. (2017). On the

Economics of an EU-Japan Free Trade Agreement (No. 86). ifo

Forschungsberichte.

JapanGov. (2019). ABENOMICS | The Government of Japan. Retrieved 21 September

2019, from https://www.japan.go.jp/abenomics/index.html

japantimes.co.jp. (2016). Japan's plunging jobless rate is due to aging, not Abenomics |

The Japan Times. Retrieved 21 September 2019, from

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/08/10/business/economy-business/

japans-plunging-jobless-rate-due-aging-not-abenomics/#.XYS8cy4zbIU

Kondo, K. (2015). Spatial persistence of Japanese unemployment rates. Japan and the

World Economy, 36, 113-122.

McCurry, J. (2009). Japan suffers record fall in GDP. Retrieved 21 September 2019,

from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/may/20/japan-economy-gdp-

fall

Murtin, F., & Robin, J. M. (2018). Labor market reforms and unemployment

dynamics. Labour Economics, 50, 3-19.

References

Boj.or.jp. (2017). "Price Stability Target" of 2 Percent and "Quantitative and Qualitative

Monetary Easing with Yield Curve Control" : 日日日日 Bank of Japan. Retrieved 21

September 2019, from https://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/outline/qqe.htm/

Carvalho, C., & Ferrero, A. (2014). What Explains Japan’s Persistent

Deflation?. Manuscript, University of Oxford, August.

cfr.org. (2018). Abenomics and the Japanese Economy. Retrieved 21 September 2019,

from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/abenomics-and-japanese-economy

Ezzy, D. (2017). Narrating unemployment. Routledge.

Felbermayr, G., Kimura, F., Okubo, T., Steininger, M., & Yalcin, E. (2017). On the

Economics of an EU-Japan Free Trade Agreement (No. 86). ifo

Forschungsberichte.

JapanGov. (2019). ABENOMICS | The Government of Japan. Retrieved 21 September

2019, from https://www.japan.go.jp/abenomics/index.html

japantimes.co.jp. (2016). Japan's plunging jobless rate is due to aging, not Abenomics |

The Japan Times. Retrieved 21 September 2019, from

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/08/10/business/economy-business/

japans-plunging-jobless-rate-due-aging-not-abenomics/#.XYS8cy4zbIU

Kondo, K. (2015). Spatial persistence of Japanese unemployment rates. Japan and the

World Economy, 36, 113-122.

McCurry, J. (2009). Japan suffers record fall in GDP. Retrieved 21 September 2019,

from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/may/20/japan-economy-gdp-

fall

Murtin, F., & Robin, J. M. (2018). Labor market reforms and unemployment

dynamics. Labour Economics, 50, 3-19.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.