International Trade: Economic Integration of Italy and Sweden Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/07

|10

|1478

|190

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the international trade relationships between Italy and Sweden, focusing on their economic integration. It begins with a data analysis of trade flows, including imports, exports, and GDP, to compute the degree of economic openness for both countries from 2002 to 2016. The analysis reveals that Italy generally has a higher degree of openness compared to Sweden, with both countries showing increasing trends over time. The report then explores the relationship between openness and economic development, using GDP per capita as a proxy. Furthermore, the report employs the Ricardian model of trade to examine comparative advantages in shoe and calculator production, determining opportunity costs, and constructing Production Possibility Frontiers (PPF) for both nations. Finally, the report determines the autarky prices, and optimal production and consumption levels under autarky for both countries.

Running head: INTERNATIONAL TRADE

International Trade

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Course ID

International Trade

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Course ID

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Table of Contents

Data Analysis...................................................................................................................................2

Economic Integration of Italy and Sweden.................................................................................2

Openness and Economic development........................................................................................4

Technical Analysis...........................................................................................................................5

Ricardian model of trade.............................................................................................................5

References........................................................................................................................................9

Table of Contents

Data Analysis...................................................................................................................................2

Economic Integration of Italy and Sweden.................................................................................2

Openness and Economic development........................................................................................4

Technical Analysis...........................................................................................................................5

Ricardian model of trade.............................................................................................................5

References........................................................................................................................................9

2INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Data Analysis

Economic Integration of Italy and Sweden

Economic integration refers to an arrangement between two or more regions that includes

reduction or elimination of tariff or non-tariff trade barriers and coordination between fiscal and

monetary policies. Economic integration among nations aims to lower cost for both consumers

and producers in order to increase trade flow among countries involved in the trade agreement.

Broadly, economic integration is classified into three groups – integration of goods/service

markets, integration of financial markets and integration of factor markets (Baier, Bergstrand and

Feng 2014). The first form of integration is used to evaluate economic integration of Italy and

Sweden. Economic openness of the two nations are computed using the trade flows and GDP of

the nation. Trade flows of countries are computed as a sum of export and import and goods and

services. Export of goods and services refers to sales of domestic product to the international

market while import of goods and services refers to the purchase of goods and services from

abroad. Trade flows include both export and import (Hosny 2013). Gross Domestic Product of a

nation indicates sum of the values of goods and services that a country produces in a given year.

Trade flows presented as a percentage of GDP thus measures share of external activities in

aggregate output or extent of economic integration.

Openness=( Export of goods∧services +Import of goods∧services)

GDP ×100

Data Analysis

Economic Integration of Italy and Sweden

Economic integration refers to an arrangement between two or more regions that includes

reduction or elimination of tariff or non-tariff trade barriers and coordination between fiscal and

monetary policies. Economic integration among nations aims to lower cost for both consumers

and producers in order to increase trade flow among countries involved in the trade agreement.

Broadly, economic integration is classified into three groups – integration of goods/service

markets, integration of financial markets and integration of factor markets (Baier, Bergstrand and

Feng 2014). The first form of integration is used to evaluate economic integration of Italy and

Sweden. Economic openness of the two nations are computed using the trade flows and GDP of

the nation. Trade flows of countries are computed as a sum of export and import and goods and

services. Export of goods and services refers to sales of domestic product to the international

market while import of goods and services refers to the purchase of goods and services from

abroad. Trade flows include both export and import (Hosny 2013). Gross Domestic Product of a

nation indicates sum of the values of goods and services that a country produces in a given year.

Trade flows presented as a percentage of GDP thus measures share of external activities in

aggregate output or extent of economic integration.

Openness=( Export of goods∧services +Import of goods∧services)

GDP ×100

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3INTERNATIONAL TRADE

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016

40.00%

50.00%

60.00%

70.00%

80.00%

90.00%

100.00%

Italy Vs Sweden

Openness (Italy)

Openness (Sweden)

Year

Openness

Figure 1: Openness of Italy and Sweden

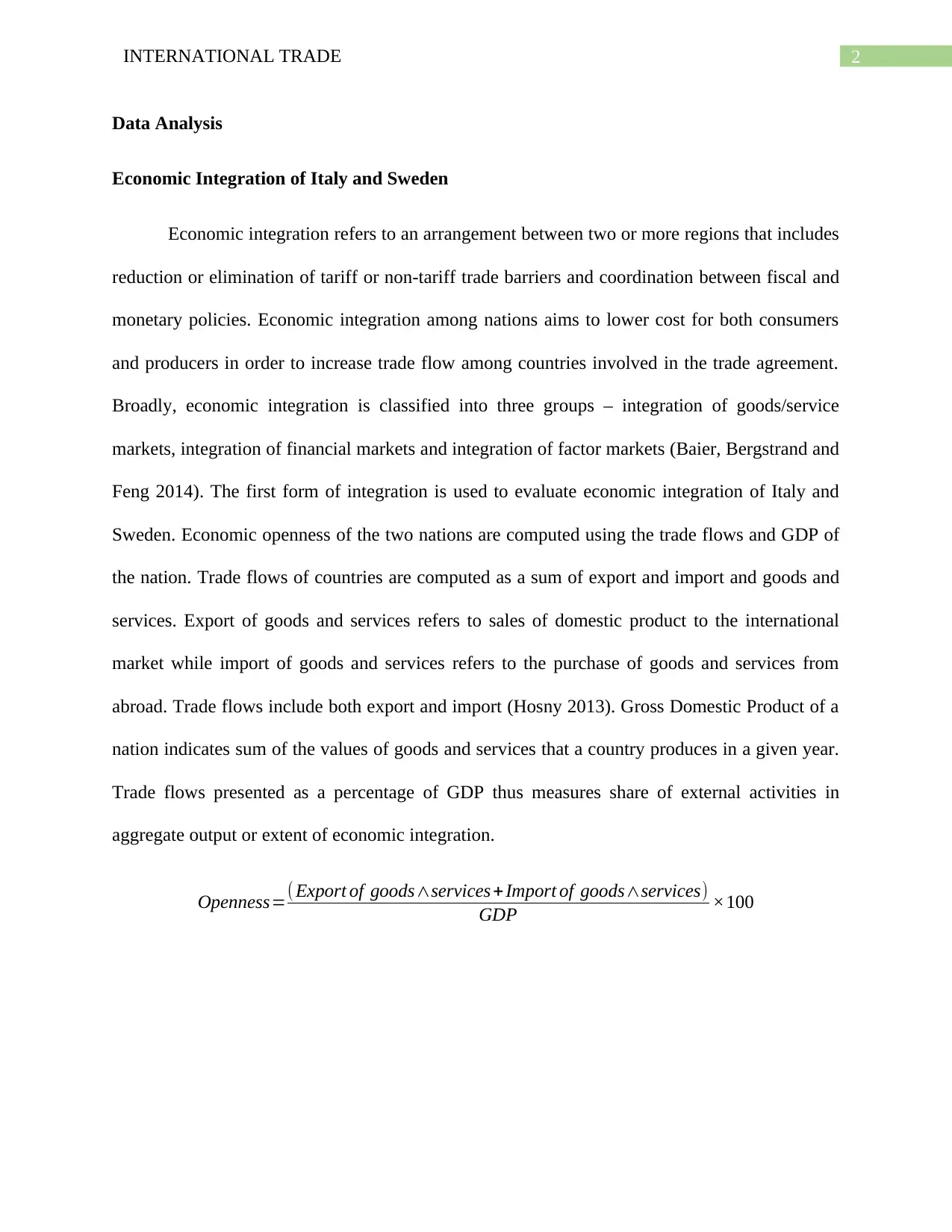

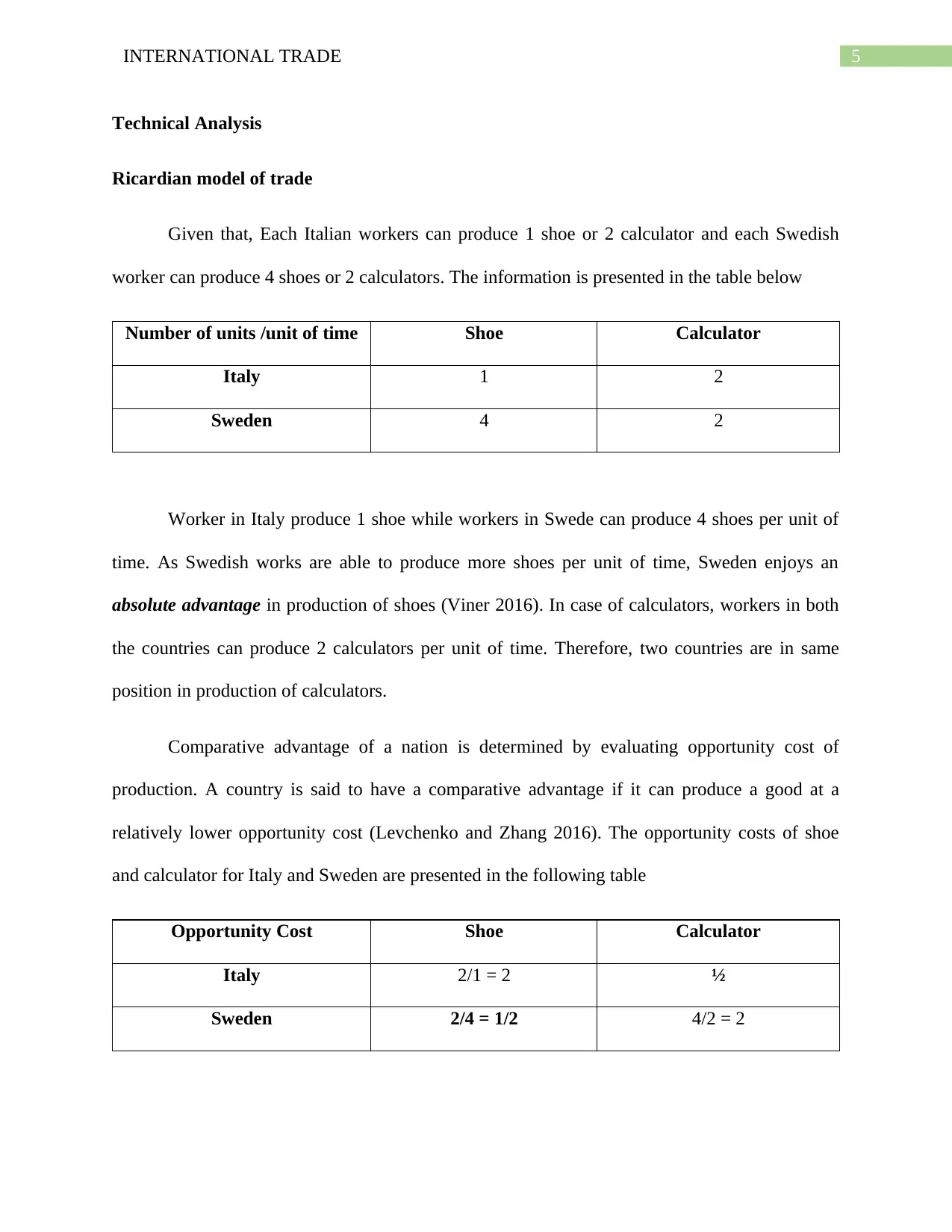

The measures of openness for Italy and Sweden show that degree of openness is higher

for Italy compared to Sweden. In both the nations, however degree of openness has increased

over time. In addition to trade flows, there are alternative measures that can be used to measure

economic integration. Indicators that represents economic integration include extent of foreign

direct or foreign portfolio investment, flow of migrant labor, immigration and extent of

offshoring (Ortega and Peri 2014).

Figure 1 shows the overtime trend in degree of openness of Italy and Sweden. The trade

flow accounts nearly 46 percent of total GDP of Italy in the year 2003. The trend of openness

reveals a continuous increasing trend from 2003 to 2007 with percentage of trade in total GDP

increased to nearly 55 percent in 2007. The percentage share of trade in GDP declined to 45

percent in 2008 and since then started to increase with percentage share of trade in GDP being

close to 57 percent in 2015.

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016

40.00%

50.00%

60.00%

70.00%

80.00%

90.00%

100.00%

Italy Vs Sweden

Openness (Italy)

Openness (Sweden)

Year

Openness

Figure 1: Openness of Italy and Sweden

The measures of openness for Italy and Sweden show that degree of openness is higher

for Italy compared to Sweden. In both the nations, however degree of openness has increased

over time. In addition to trade flows, there are alternative measures that can be used to measure

economic integration. Indicators that represents economic integration include extent of foreign

direct or foreign portfolio investment, flow of migrant labor, immigration and extent of

offshoring (Ortega and Peri 2014).

Figure 1 shows the overtime trend in degree of openness of Italy and Sweden. The trade

flow accounts nearly 46 percent of total GDP of Italy in the year 2003. The trend of openness

reveals a continuous increasing trend from 2003 to 2007 with percentage of trade in total GDP

increased to nearly 55 percent in 2007. The percentage share of trade in GDP declined to 45

percent in 2008 and since then started to increase with percentage share of trade in GDP being

close to 57 percent in 2015.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4INTERNATIONAL TRADE

In case of Sweden, the estimated degree of openness is greater than Italy. Trade accounts

a much larger share of Sweden’s GDP. The estimated share of trade in GDP of Sweden in 2000

approximately equals 76 percent. The trade share continued to increase until 2008 with share

being as high as 93 percent. The share slightly declined in 2009 but still accounted to be 83

percent. Since then the continuous increase in export and import contributed to an increase in

trade share. The share of trade flows in GDP accounted to be 86 percent in 2015.

Openness and Economic development

The standard theory of trade suggests that participating in trade; a country can improve its

welfare. With trade, country can enjoy a wide range of goods and services at a relatively cheaper

price. Before trade, consumption of a nation remains limited by the goods and services produced

within the nation (Balassa 2013). Opening up to trade expands consumption choice of the nation.

Trade thus has a welfare enhancing effect and contributes to economic development. For purpose

of the paper, GDP per capita is taken as a proxy measure of economic development. The relation

between openness and economic development has been evaluated by computing the correlation

between GDP per capita and openness. For Italy, the correlation between GDP per capita and

openness is computed as 0.41. The positive correlation suggests that openness has a positive

association with GDP per capita. That means increase in openness contributes to an increase in

per capita GDP of Italy and hence, increases economic development (Van den Berg 2016). For

Sweden, the correlation between openness and GDP per capita is 0.57. Higher correlation

suggests a relatively stronger association between the two. The evidences for Italy and Sweden

thus suggest that more and more involvement in trade contribute to economic development.

In case of Sweden, the estimated degree of openness is greater than Italy. Trade accounts

a much larger share of Sweden’s GDP. The estimated share of trade in GDP of Sweden in 2000

approximately equals 76 percent. The trade share continued to increase until 2008 with share

being as high as 93 percent. The share slightly declined in 2009 but still accounted to be 83

percent. Since then the continuous increase in export and import contributed to an increase in

trade share. The share of trade flows in GDP accounted to be 86 percent in 2015.

Openness and Economic development

The standard theory of trade suggests that participating in trade; a country can improve its

welfare. With trade, country can enjoy a wide range of goods and services at a relatively cheaper

price. Before trade, consumption of a nation remains limited by the goods and services produced

within the nation (Balassa 2013). Opening up to trade expands consumption choice of the nation.

Trade thus has a welfare enhancing effect and contributes to economic development. For purpose

of the paper, GDP per capita is taken as a proxy measure of economic development. The relation

between openness and economic development has been evaluated by computing the correlation

between GDP per capita and openness. For Italy, the correlation between GDP per capita and

openness is computed as 0.41. The positive correlation suggests that openness has a positive

association with GDP per capita. That means increase in openness contributes to an increase in

per capita GDP of Italy and hence, increases economic development (Van den Berg 2016). For

Sweden, the correlation between openness and GDP per capita is 0.57. Higher correlation

suggests a relatively stronger association between the two. The evidences for Italy and Sweden

thus suggest that more and more involvement in trade contribute to economic development.

5INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Technical Analysis

Ricardian model of trade

Given that, Each Italian workers can produce 1 shoe or 2 calculator and each Swedish

worker can produce 4 shoes or 2 calculators. The information is presented in the table below

Number of units /unit of time Shoe Calculator

Italy 1 2

Sweden 4 2

Worker in Italy produce 1 shoe while workers in Swede can produce 4 shoes per unit of

time. As Swedish works are able to produce more shoes per unit of time, Sweden enjoys an

absolute advantage in production of shoes (Viner 2016). In case of calculators, workers in both

the countries can produce 2 calculators per unit of time. Therefore, two countries are in same

position in production of calculators.

Comparative advantage of a nation is determined by evaluating opportunity cost of

production. A country is said to have a comparative advantage if it can produce a good at a

relatively lower opportunity cost (Levchenko and Zhang 2016). The opportunity costs of shoe

and calculator for Italy and Sweden are presented in the following table

Opportunity Cost Shoe Calculator

Italy 2/1 = 2 ½

Sweden 2/4 = 1/2 4/2 = 2

Technical Analysis

Ricardian model of trade

Given that, Each Italian workers can produce 1 shoe or 2 calculator and each Swedish

worker can produce 4 shoes or 2 calculators. The information is presented in the table below

Number of units /unit of time Shoe Calculator

Italy 1 2

Sweden 4 2

Worker in Italy produce 1 shoe while workers in Swede can produce 4 shoes per unit of

time. As Swedish works are able to produce more shoes per unit of time, Sweden enjoys an

absolute advantage in production of shoes (Viner 2016). In case of calculators, workers in both

the countries can produce 2 calculators per unit of time. Therefore, two countries are in same

position in production of calculators.

Comparative advantage of a nation is determined by evaluating opportunity cost of

production. A country is said to have a comparative advantage if it can produce a good at a

relatively lower opportunity cost (Levchenko and Zhang 2016). The opportunity costs of shoe

and calculator for Italy and Sweden are presented in the following table

Opportunity Cost Shoe Calculator

Italy 2/1 = 2 ½

Sweden 2/4 = 1/2 4/2 = 2

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6INTERNATIONAL TRADE

As shown from the above table, in order to produce 1 shoe, Italy needs to sacrifice 2

calculators while Sweden sacrifices only 1/2 calculator. Sweden thus has a lower opportunity

cost to produce shoe giving Sweden a comparative advantage in shoe production. In order to

produce 1 calculator, Italy needs to forgo ½ shoe while Sweden needs to forgo 2 shoes. The

opportunity cost of calculator is lower in Italy as compared to Sweden. Italy thus has a

comparative advantage in producing calculators.

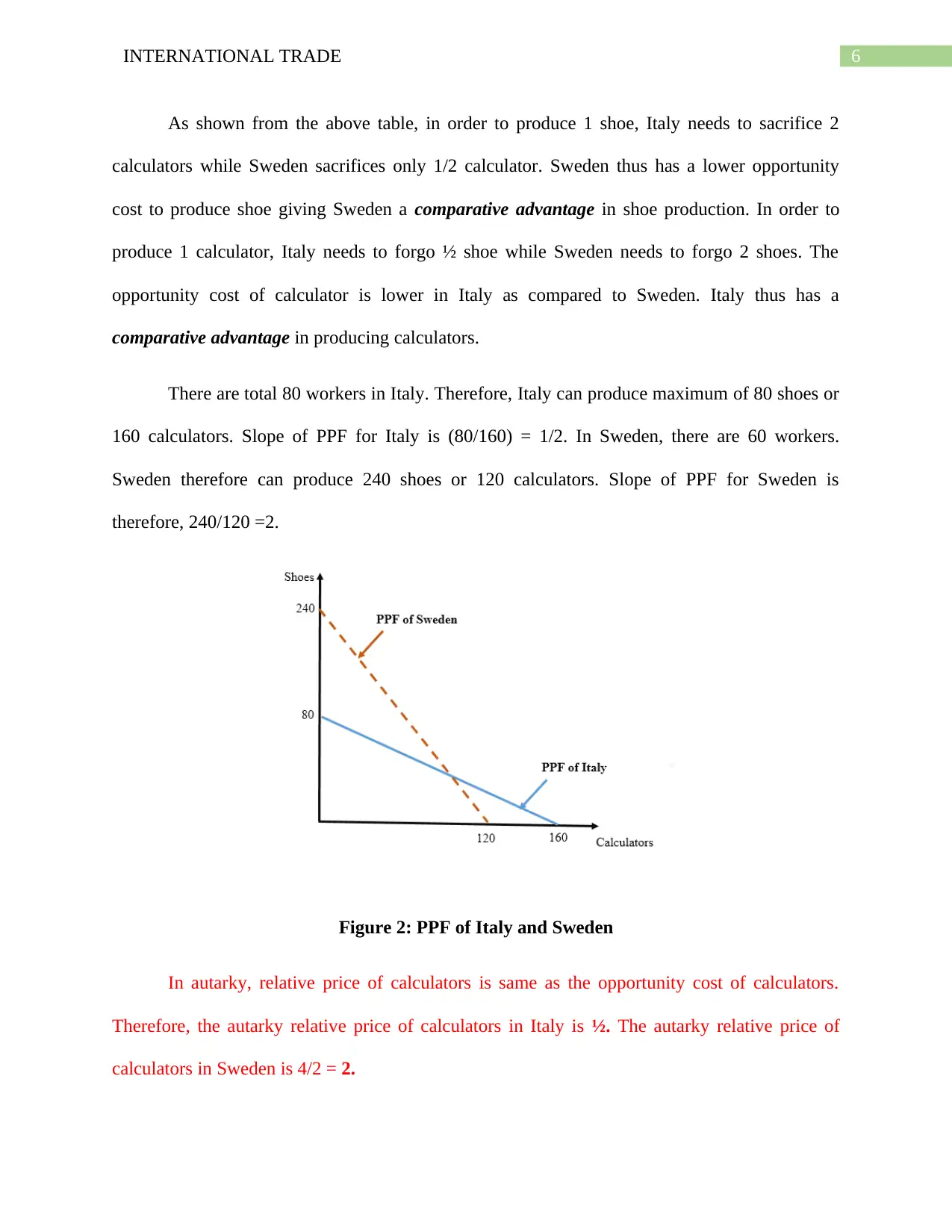

There are total 80 workers in Italy. Therefore, Italy can produce maximum of 80 shoes or

160 calculators. Slope of PPF for Italy is (80/160) = 1/2. In Sweden, there are 60 workers.

Sweden therefore can produce 240 shoes or 120 calculators. Slope of PPF for Sweden is

therefore, 240/120 =2.

Figure 2: PPF of Italy and Sweden

In autarky, relative price of calculators is same as the opportunity cost of calculators.

Therefore, the autarky relative price of calculators in Italy is ½. The autarky relative price of

calculators in Sweden is 4/2 = 2.

As shown from the above table, in order to produce 1 shoe, Italy needs to sacrifice 2

calculators while Sweden sacrifices only 1/2 calculator. Sweden thus has a lower opportunity

cost to produce shoe giving Sweden a comparative advantage in shoe production. In order to

produce 1 calculator, Italy needs to forgo ½ shoe while Sweden needs to forgo 2 shoes. The

opportunity cost of calculator is lower in Italy as compared to Sweden. Italy thus has a

comparative advantage in producing calculators.

There are total 80 workers in Italy. Therefore, Italy can produce maximum of 80 shoes or

160 calculators. Slope of PPF for Italy is (80/160) = 1/2. In Sweden, there are 60 workers.

Sweden therefore can produce 240 shoes or 120 calculators. Slope of PPF for Sweden is

therefore, 240/120 =2.

Figure 2: PPF of Italy and Sweden

In autarky, relative price of calculators is same as the opportunity cost of calculators.

Therefore, the autarky relative price of calculators in Italy is ½. The autarky relative price of

calculators in Sweden is 4/2 = 2.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7INTERNATIONAL TRADE

( Relative price of calculator )Italy= Price of calculators

Price of shoes

¿ 1

2

( Relative price of calculator )Sweden= Price of calculators

Price of shoes

¿ 4

2

¿ 2

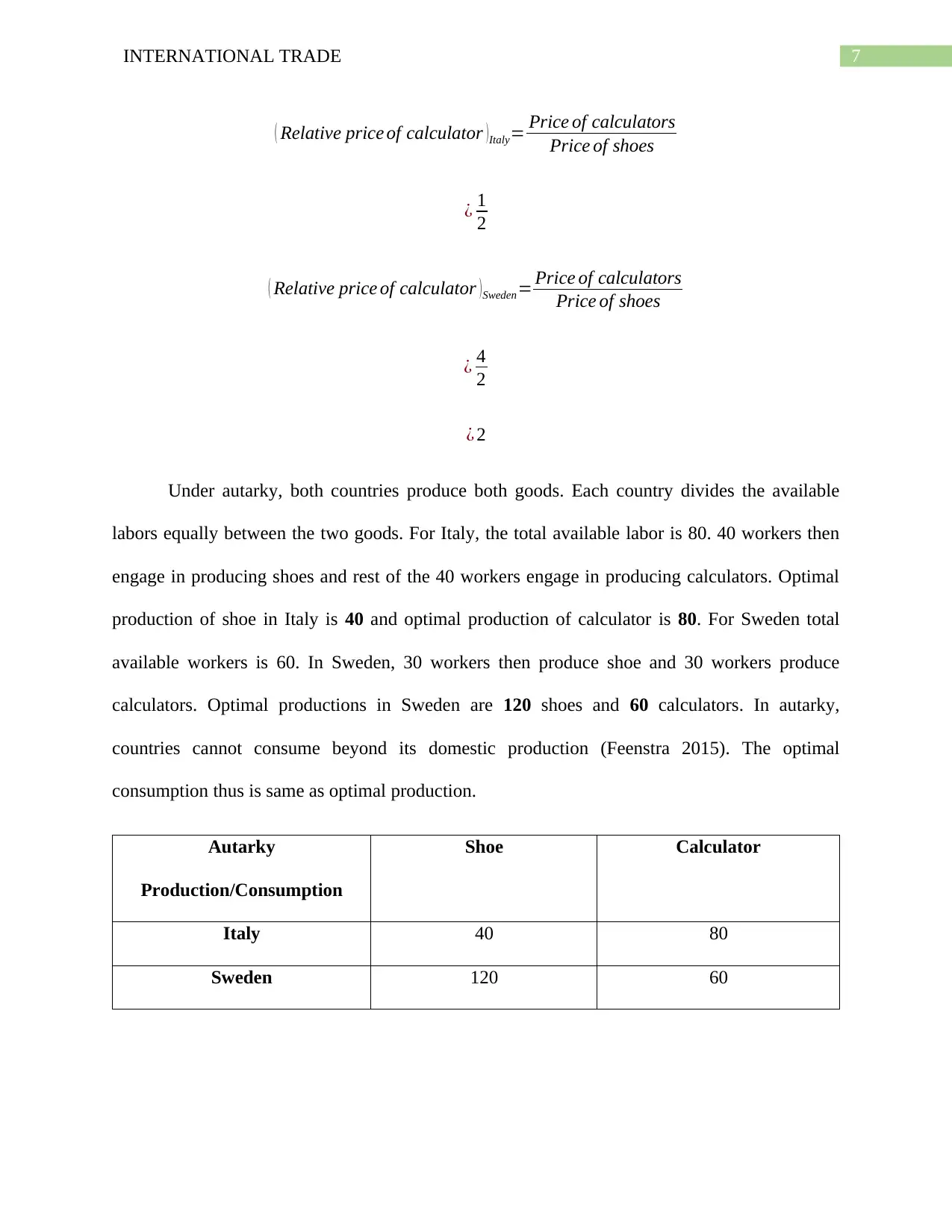

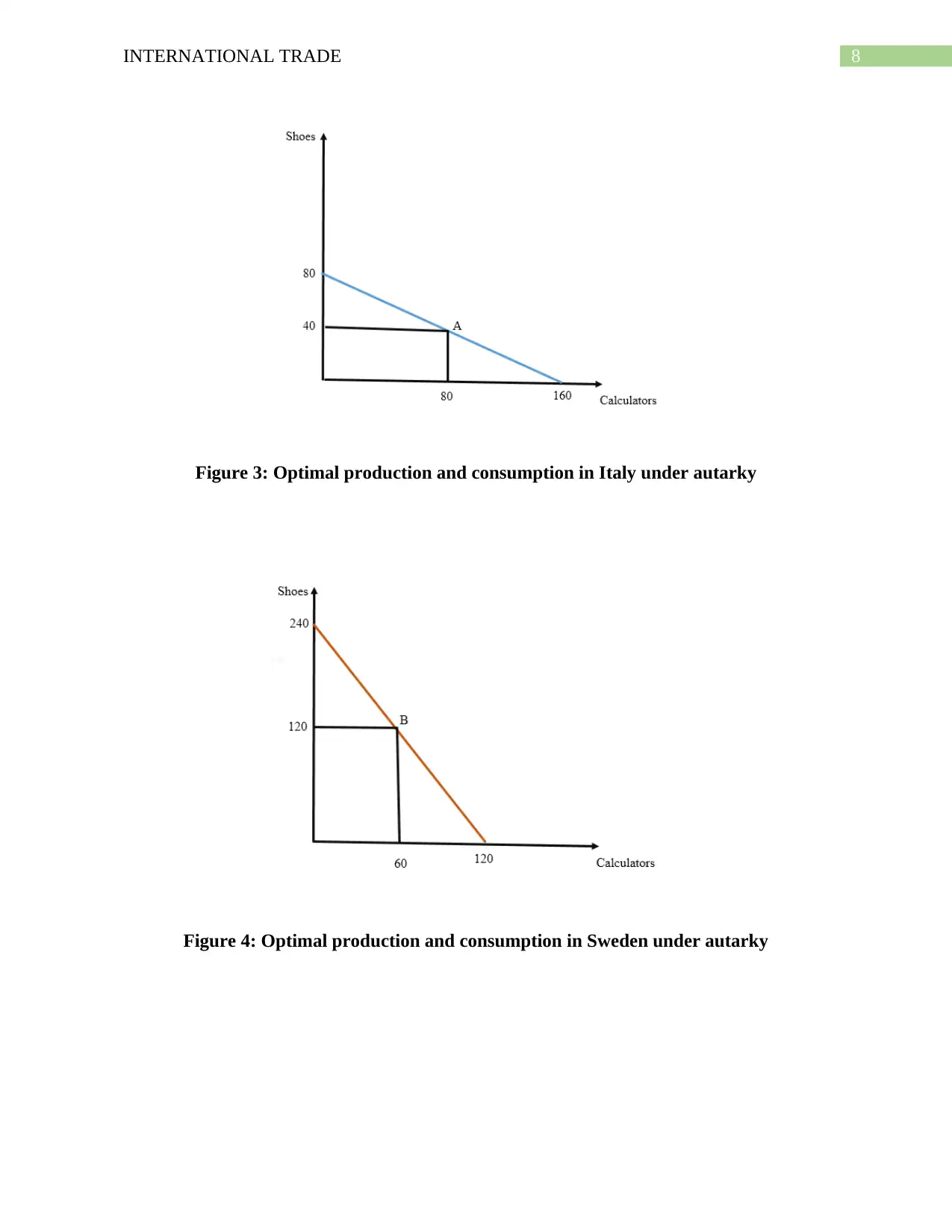

Under autarky, both countries produce both goods. Each country divides the available

labors equally between the two goods. For Italy, the total available labor is 80. 40 workers then

engage in producing shoes and rest of the 40 workers engage in producing calculators. Optimal

production of shoe in Italy is 40 and optimal production of calculator is 80. For Sweden total

available workers is 60. In Sweden, 30 workers then produce shoe and 30 workers produce

calculators. Optimal productions in Sweden are 120 shoes and 60 calculators. In autarky,

countries cannot consume beyond its domestic production (Feenstra 2015). The optimal

consumption thus is same as optimal production.

Autarky

Production/Consumption

Shoe Calculator

Italy 40 80

Sweden 120 60

( Relative price of calculator )Italy= Price of calculators

Price of shoes

¿ 1

2

( Relative price of calculator )Sweden= Price of calculators

Price of shoes

¿ 4

2

¿ 2

Under autarky, both countries produce both goods. Each country divides the available

labors equally between the two goods. For Italy, the total available labor is 80. 40 workers then

engage in producing shoes and rest of the 40 workers engage in producing calculators. Optimal

production of shoe in Italy is 40 and optimal production of calculator is 80. For Sweden total

available workers is 60. In Sweden, 30 workers then produce shoe and 30 workers produce

calculators. Optimal productions in Sweden are 120 shoes and 60 calculators. In autarky,

countries cannot consume beyond its domestic production (Feenstra 2015). The optimal

consumption thus is same as optimal production.

Autarky

Production/Consumption

Shoe Calculator

Italy 40 80

Sweden 120 60

8INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Figure 3: Optimal production and consumption in Italy under autarky

Figure 4: Optimal production and consumption in Sweden under autarky

Figure 3: Optimal production and consumption in Italy under autarky

Figure 4: Optimal production and consumption in Sweden under autarky

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9INTERNATIONAL TRADE

References

Baier, S.L., Bergstrand, J.H. and Feng, M., 2014. Economic integration agreements and the

margins of international trade. Journal of International Economics, 93(2), pp.339-350.

Balassa, B., 2013. The theory of economic integration (routledge revivals). Routledge.

Feenstra, R.C., 2015. Advanced international trade: theory and evidence. Princeton university

press.

Hosny, A.S., 2013. Theories of economic integration: a survey of the economic and political

literature. International Journal of Economy, Management and Social Sciences, 2(5), pp.133-

155.

Levchenko, A.A. and Zhang, J., 2016. The evolution of comparative advantage: Measurement

and welfare implications. Journal of Monetary Economics, 78, pp.96-111.

Ortega, F. and Peri, G., 2014. Openness and income: The roles of trade and migration. Journal

of international Economics, 92(2), pp.231-251.

Van den Berg, H., 2016. Economic growth and development. World Scientific Publishing

Company.

Viner, J., 2016. Studies in the theory of international trade. Routledge.

References

Baier, S.L., Bergstrand, J.H. and Feng, M., 2014. Economic integration agreements and the

margins of international trade. Journal of International Economics, 93(2), pp.339-350.

Balassa, B., 2013. The theory of economic integration (routledge revivals). Routledge.

Feenstra, R.C., 2015. Advanced international trade: theory and evidence. Princeton university

press.

Hosny, A.S., 2013. Theories of economic integration: a survey of the economic and political

literature. International Journal of Economy, Management and Social Sciences, 2(5), pp.133-

155.

Levchenko, A.A. and Zhang, J., 2016. The evolution of comparative advantage: Measurement

and welfare implications. Journal of Monetary Economics, 78, pp.96-111.

Ortega, F. and Peri, G., 2014. Openness and income: The roles of trade and migration. Journal

of international Economics, 92(2), pp.231-251.

Van den Berg, H., 2016. Economic growth and development. World Scientific Publishing

Company.

Viner, J., 2016. Studies in the theory of international trade. Routledge.

1 out of 10

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.