Economics for Business: Exploring Economic Concepts and Elasticity

VerifiedAdded on 2021/04/17

|6

|1489

|24

Homework Assignment

AI Summary

This assignment explores fundamental economic principles and their practical applications. It begins by defining and explaining three key economic ideas: rational behavior, the role of incentives, and the concept of making optimal decisions at the margin. The assignment then delves into the concept of income elasticity of demand, providing estimates for different products and categorizing goods as normal or inferior based on their elasticity. The analysis includes examples such as bread, gold, and public transport to illustrate how changes in consumer income affect demand. The document references several academic sources to support the analysis and provides a comprehensive overview of economic concepts relevant to business.

Running Head: Economics for Business

Economics for Business

Economics for Business

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Economics for Business 1

Question 1: Define and explain the three key economic ideas:

People are rational: Rationality plays an important role in the field of economics. It is a

common to assume that people are rational in behaviour. They choose a bundle of goods,

from the given alternatives, which gives them highest level of satisfaction. The resources are

taken to be constant and the decision is made according to the priorities and preferences

(Mathis & Steffen, 2012). Consumer, producers and society try to maximise their level of

satisfaction, profits and welfare respectively. They all work at margin. A consumer tries to

consume a commodity till the point his satisfaction from additional unit turns to zero, given

his level of income and prevailing prices (Krstic & Krstic, 2015). Producer produces till the

point where his gains from additional unit turn to zero. For example, if George produces

belts, he will produce till the point where his profits (revenue- cost) turn to zero with given

resources and technology. There is no incentive for him to produce further as the costs will be

higher than the revenue.

People respond to incentives: Incentive motivates consumers, producers and society to

increase their consumption, production and welfare respectively. A rational person compares

his costs to his gains. Positive incentives increase the gains of each while the negative ones

forbid further consumption or production (Cardinaels & Jia, 2010). Fall in prices is a positive

incentive for consumers to increase their consumption while the same phenomenon is

negative for the producers and vice versa. They then decrease their production until the

increase in demand (because of lower price) pushes the prices back to the initial value.

Decline in prices both increases the demand and decrease the production. Producers decrease

the output because their profits are reduced (Matthew McCaffrey, 2014). For example, if the

price of apples falls, Serena increases her consumption of apples with her given level of

income. The reduced prices acts as in incentive and persuades Serena to increase her

satisfaction with increased consumption.

Optimal decisions are made at the margin: A rational person makes a decision based on a

given number of alternatives. He trade-offs the ones associated with lesser satisfaction for the

better ones, as per his preferences. These decisions are made with respect to the existing

circumstances. It is about increase or decrease in the current consumption or production.

Decisions are never about all or none. Optimum decisions are made in terms of satisfaction or

profits derived from the subsequent unit. Decision will be favourable when the satisfaction or

gains from the subsequent unit exceeds the cost or it and vice versa. At the optimum level,

Question 1: Define and explain the three key economic ideas:

People are rational: Rationality plays an important role in the field of economics. It is a

common to assume that people are rational in behaviour. They choose a bundle of goods,

from the given alternatives, which gives them highest level of satisfaction. The resources are

taken to be constant and the decision is made according to the priorities and preferences

(Mathis & Steffen, 2012). Consumer, producers and society try to maximise their level of

satisfaction, profits and welfare respectively. They all work at margin. A consumer tries to

consume a commodity till the point his satisfaction from additional unit turns to zero, given

his level of income and prevailing prices (Krstic & Krstic, 2015). Producer produces till the

point where his gains from additional unit turn to zero. For example, if George produces

belts, he will produce till the point where his profits (revenue- cost) turn to zero with given

resources and technology. There is no incentive for him to produce further as the costs will be

higher than the revenue.

People respond to incentives: Incentive motivates consumers, producers and society to

increase their consumption, production and welfare respectively. A rational person compares

his costs to his gains. Positive incentives increase the gains of each while the negative ones

forbid further consumption or production (Cardinaels & Jia, 2010). Fall in prices is a positive

incentive for consumers to increase their consumption while the same phenomenon is

negative for the producers and vice versa. They then decrease their production until the

increase in demand (because of lower price) pushes the prices back to the initial value.

Decline in prices both increases the demand and decrease the production. Producers decrease

the output because their profits are reduced (Matthew McCaffrey, 2014). For example, if the

price of apples falls, Serena increases her consumption of apples with her given level of

income. The reduced prices acts as in incentive and persuades Serena to increase her

satisfaction with increased consumption.

Optimal decisions are made at the margin: A rational person makes a decision based on a

given number of alternatives. He trade-offs the ones associated with lesser satisfaction for the

better ones, as per his preferences. These decisions are made with respect to the existing

circumstances. It is about increase or decrease in the current consumption or production.

Decisions are never about all or none. Optimum decisions are made in terms of satisfaction or

profits derived from the subsequent unit. Decision will be favourable when the satisfaction or

gains from the subsequent unit exceeds the cost or it and vice versa. At the optimum level,

Economics for Business 2

marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue. After this point, gains are less than the costs and

the production or consumption is reduced (Lunenburg, 2010). For example, Dan, a bread

baker, uses marginal analysis to compare the costs and gains associated with the additional

production of breads. He employs his funds and other resources to increase the production

when there is high demand. The gains will be more than the cost associated with the

production increase.

Question 2: Using the economics or other literature to identify estimates of the income

elasticity of demand for at least three different products.

Income Elasticity of Demand estimates:

Income elasticity of demand refers to the responsiveness of demanded quantity of a good for

a given change in the income of the consumer (Fouquet, 2010). It is used to estimate the

future production gains associated with the rise in the income level of the consumers. It can

be calculated as follows:

Income elasticity of demand (η)¿ % change∈quantity demanded

% change∈income level

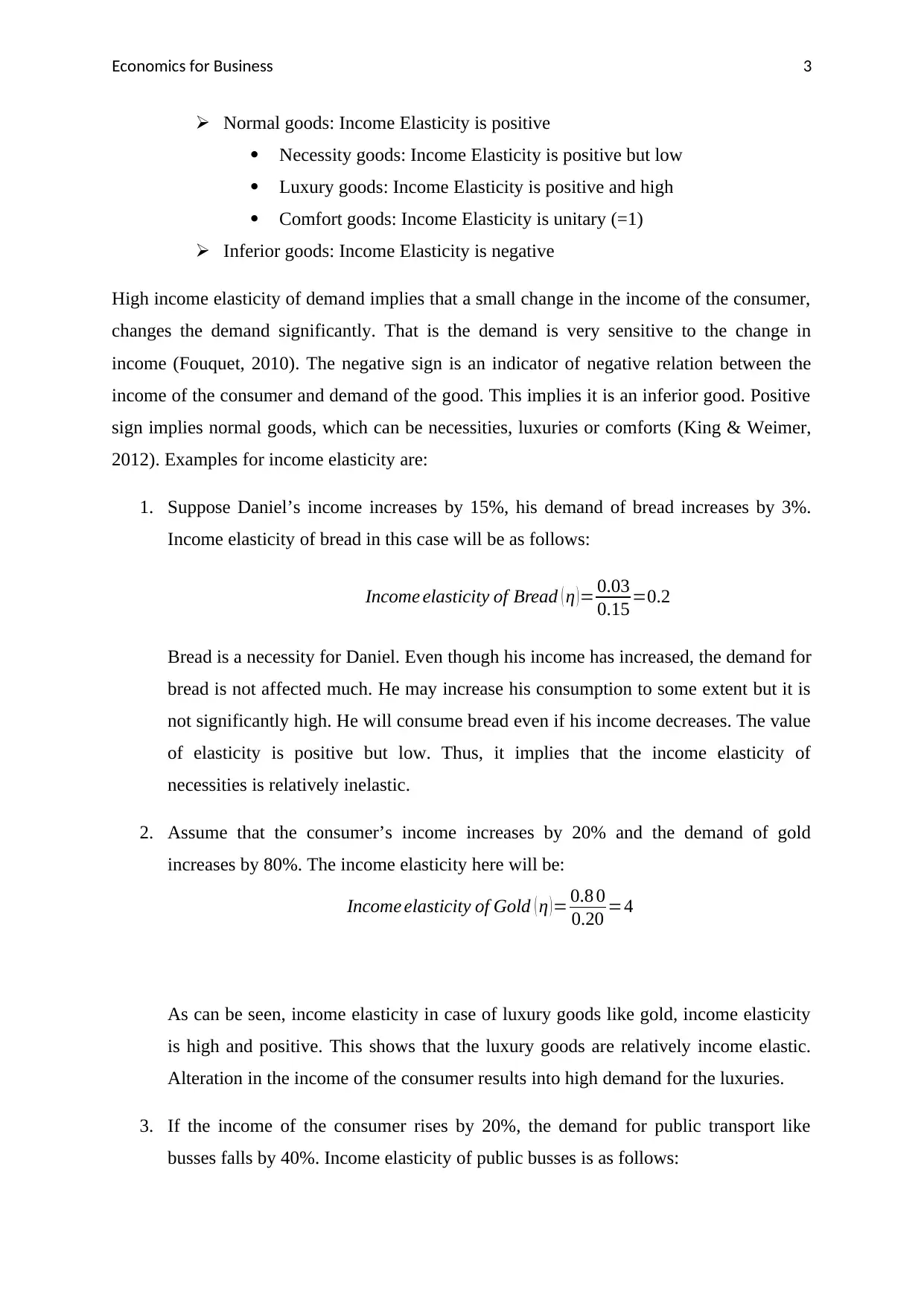

The income elasticity of demand has a range from zero to ∞ infinity. As the value of

elasticity gets closer to infinity, the more elastic is the good. If the magnitude is closer to

zero, then the good is inelastic to the income. Income elasticity range is as follows:

Value Elasticity

0 Perfectly Inelastic

0< η <1 Relatively Inelastic

1 Unit Elastic

1< η <∞ Relatively Elastic

∞ Perfectly Elastic

Income elasticity of demand bifurcates goods into normal and inferior. Normal goods have a

positive relationship between income level and demand while inferior goods’ demand

increases with the decrease in income level and vice versa (Khan, 2012).

marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue. After this point, gains are less than the costs and

the production or consumption is reduced (Lunenburg, 2010). For example, Dan, a bread

baker, uses marginal analysis to compare the costs and gains associated with the additional

production of breads. He employs his funds and other resources to increase the production

when there is high demand. The gains will be more than the cost associated with the

production increase.

Question 2: Using the economics or other literature to identify estimates of the income

elasticity of demand for at least three different products.

Income Elasticity of Demand estimates:

Income elasticity of demand refers to the responsiveness of demanded quantity of a good for

a given change in the income of the consumer (Fouquet, 2010). It is used to estimate the

future production gains associated with the rise in the income level of the consumers. It can

be calculated as follows:

Income elasticity of demand (η)¿ % change∈quantity demanded

% change∈income level

The income elasticity of demand has a range from zero to ∞ infinity. As the value of

elasticity gets closer to infinity, the more elastic is the good. If the magnitude is closer to

zero, then the good is inelastic to the income. Income elasticity range is as follows:

Value Elasticity

0 Perfectly Inelastic

0< η <1 Relatively Inelastic

1 Unit Elastic

1< η <∞ Relatively Elastic

∞ Perfectly Elastic

Income elasticity of demand bifurcates goods into normal and inferior. Normal goods have a

positive relationship between income level and demand while inferior goods’ demand

increases with the decrease in income level and vice versa (Khan, 2012).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Economics for Business 3

Normal goods: Income Elasticity is positive

Necessity goods: Income Elasticity is positive but low

Luxury goods: Income Elasticity is positive and high

Comfort goods: Income Elasticity is unitary (=1)

Inferior goods: Income Elasticity is negative

High income elasticity of demand implies that a small change in the income of the consumer,

changes the demand significantly. That is the demand is very sensitive to the change in

income (Fouquet, 2010). The negative sign is an indicator of negative relation between the

income of the consumer and demand of the good. This implies it is an inferior good. Positive

sign implies normal goods, which can be necessities, luxuries or comforts (King & Weimer,

2012). Examples for income elasticity are:

1. Suppose Daniel’s income increases by 15%, his demand of bread increases by 3%.

Income elasticity of bread in this case will be as follows:

Income elasticity of Bread ( η ) = 0.03

0.15 =0.2

Bread is a necessity for Daniel. Even though his income has increased, the demand for

bread is not affected much. He may increase his consumption to some extent but it is

not significantly high. He will consume bread even if his income decreases. The value

of elasticity is positive but low. Thus, it implies that the income elasticity of

necessities is relatively inelastic.

2. Assume that the consumer’s income increases by 20% and the demand of gold

increases by 80%. The income elasticity here will be:

Income elasticity of Gold ( η )= 0.8 0

0.20 =4

As can be seen, income elasticity in case of luxury goods like gold, income elasticity

is high and positive. This shows that the luxury goods are relatively income elastic.

Alteration in the income of the consumer results into high demand for the luxuries.

3. If the income of the consumer rises by 20%, the demand for public transport like

busses falls by 40%. Income elasticity of public busses is as follows:

Normal goods: Income Elasticity is positive

Necessity goods: Income Elasticity is positive but low

Luxury goods: Income Elasticity is positive and high

Comfort goods: Income Elasticity is unitary (=1)

Inferior goods: Income Elasticity is negative

High income elasticity of demand implies that a small change in the income of the consumer,

changes the demand significantly. That is the demand is very sensitive to the change in

income (Fouquet, 2010). The negative sign is an indicator of negative relation between the

income of the consumer and demand of the good. This implies it is an inferior good. Positive

sign implies normal goods, which can be necessities, luxuries or comforts (King & Weimer,

2012). Examples for income elasticity are:

1. Suppose Daniel’s income increases by 15%, his demand of bread increases by 3%.

Income elasticity of bread in this case will be as follows:

Income elasticity of Bread ( η ) = 0.03

0.15 =0.2

Bread is a necessity for Daniel. Even though his income has increased, the demand for

bread is not affected much. He may increase his consumption to some extent but it is

not significantly high. He will consume bread even if his income decreases. The value

of elasticity is positive but low. Thus, it implies that the income elasticity of

necessities is relatively inelastic.

2. Assume that the consumer’s income increases by 20% and the demand of gold

increases by 80%. The income elasticity here will be:

Income elasticity of Gold ( η )= 0.8 0

0.20 =4

As can be seen, income elasticity in case of luxury goods like gold, income elasticity

is high and positive. This shows that the luxury goods are relatively income elastic.

Alteration in the income of the consumer results into high demand for the luxuries.

3. If the income of the consumer rises by 20%, the demand for public transport like

busses falls by 40%. Income elasticity of public busses is as follows:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Economics for Business 4

Income elasticity of Public Busses( η)=−0.40

0.20 =−2

The negative sign only signifies that it is an inferior good.

Here, the income elasticity is negative and relatively elastic. When the income of the

consumer rises, the demand for inferior good gets reduced. Since, the quality of the

goods is low; people opt for better options with the increased income. They switch to

cabs in the given case.

References

Cardinaels, E., & Jia, Y. (2010). The Impact of Economic Incentives and Peer Influences.

Retrieved March 09, 2018, from

file:///C:/Users/%234079/Downloads/econ_incent_peers_honesty_final_draft.pdf

Fouquet, R. (2010). Trens in Income and Price Elasticities of Transport Demand (1850-

2010). Energy Policy, 50, 50-61.

Khan, S. (2012, June). Income Elasticities of Demand for major consumption items.

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 02(06).

King, M. K., & Weimer, D. L. (2012). Price and Income Elasticities of Demand for Energy.

Theory and Practices for Energy Education, Training, Regulation and Standards.

Krstic, B., & Krstic, M. (2015). Rational Choice Theory and Random Behvaviour. Original

Scientific Article, 61(01), 1-13.

Lunenburg, F. C. (2010). The Decision Making Process. National Forum of Educational

Administration and Supervision Journal, 27(04).

Mathis, K., & Steffen, A. D. (2012). From Rational Choice to Behavioural. Retrieved March

09, 2018, from

Income elasticity of Public Busses( η)=−0.40

0.20 =−2

The negative sign only signifies that it is an inferior good.

Here, the income elasticity is negative and relatively elastic. When the income of the

consumer rises, the demand for inferior good gets reduced. Since, the quality of the

goods is low; people opt for better options with the increased income. They switch to

cabs in the given case.

References

Cardinaels, E., & Jia, Y. (2010). The Impact of Economic Incentives and Peer Influences.

Retrieved March 09, 2018, from

file:///C:/Users/%234079/Downloads/econ_incent_peers_honesty_final_draft.pdf

Fouquet, R. (2010). Trens in Income and Price Elasticities of Transport Demand (1850-

2010). Energy Policy, 50, 50-61.

Khan, S. (2012, June). Income Elasticities of Demand for major consumption items.

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 02(06).

King, M. K., & Weimer, D. L. (2012). Price and Income Elasticities of Demand for Energy.

Theory and Practices for Energy Education, Training, Regulation and Standards.

Krstic, B., & Krstic, M. (2015). Rational Choice Theory and Random Behvaviour. Original

Scientific Article, 61(01), 1-13.

Lunenburg, F. C. (2010). The Decision Making Process. National Forum of Educational

Administration and Supervision Journal, 27(04).

Mathis, K., & Steffen, A. D. (2012). From Rational Choice to Behavioural. Retrieved March

09, 2018, from

Economics for Business 5

https://www.unilu.ch/fileadmin/fakultaeten/rf/mathis/Dok/1_Mathis_Steffen_From_R

ational_Choice_to_Behavioural_Economics.pdf

Matthew McCaffrey. (2014). Incetive and Economic Point of View: The Case of Popular

Economics. The Review of Social and Economic Issues, 01(01), 71-87.

https://www.unilu.ch/fileadmin/fakultaeten/rf/mathis/Dok/1_Mathis_Steffen_From_R

ational_Choice_to_Behavioural_Economics.pdf

Matthew McCaffrey. (2014). Incetive and Economic Point of View: The Case of Popular

Economics. The Review of Social and Economic Issues, 01(01), 71-87.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 6

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.