Guidelines for Writing a Comprehensive Research Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/02

|5

|2157

|50

Report

AI Summary

This document provides a comprehensive guide to writing a research report, primarily focusing on the structure and style of academic writing. It begins by emphasizing the importance of early-stage writing and outlining, recommending the use of drafts and revisions, and providing a framework for the typical five-chapter structure of a Master's dissertation, including the introduction, literature review, methodology, results, and conclusion. The report emphasizes the importance of a research proposal, detailing its key components, including the introduction, literature review, theoretical framework, methodology, and conclusion. It then focuses on enhancing the readability of the report, including using consistent terms, understanding narrative thoughts, and maintaining coherence. The document also includes a section on improving writing style, recommending the use of active voice, strong verbs, appropriate tense, and editing for conciseness. References to key texts on research methodology and academic writing are provided. This document serves as a valuable resource for students looking to improve their research report writing skills.

1

WEEK 4 NOTES

WRITING RESEARCH REPORT

The notes are mostly extracted (copy paste) from the references provided at the end of this document.

Undertaking Writing

Before a writing endeavour is ventured, it is advisable for students to read previous Master

dissertation to grasp the writing style of research. Reading journal articles will also help.

One sign of inexperienced writers is that they prefer to discuss their proposed study rather than

write about it. It is helpful to write it out quickly as rough as it may be in the first rendering.

The following are recommended:

Early in the process of research, write ideas down rather than talk about them. One

author has talked directly about this concept of writing as thinking (Bailey, 1984).

Zinsser (1983) also discussed the need to get words out of our heads and onto paper.

Advisers react better when they read the ideas on paper than when they hear and discuss

a research topic with a student or colleague. When a researcher renders ideas on paper,

a reader can visualize the final product, actually see how it looks, and begin to clarify

ideas. The concept of working ideas out on paper has served many experienced writers

well. Before designing a proposal, draft a one- to two-page overview of your project

and have your adviser approve the direction of your proposed study. This draft might

contain the essential information: the research problem being addressed, the purpose of

the study, the central questions being asked, the source of data, and the significance of

the project for different audiences. It might also be useful to draft several one- to two

page statements on different topics and see which one your adviser likes best and feels

would make the best contribution to your field.

Work through several drafts of a proposal rather than trying to polish the first draft. It

is illuminating to see how people think on paper. Do not edit your proposal at the

early-draft stage. Instead, consider Franklin’s (1986) three-stage model, which have

been found useful in developing proposals and in our scholarly writing:

o First, develop an outline; it could be a sentence or word outline or a visual

map.

o Write out a draft and then shift and sort ideas, moving around entire

paragraphs in the manuscript.

o Finally, edit and polish each sentence.

Project Report Structure

For a Master’s dissertation, there are generally five chapters to report:

Chapter 1 – Introduction

Chapter 2 – Literature Review

Chapter 3 – Data and Methodology

Chapter 4 – Results and Analysis

Chapter 5 – Conclusion

WEEK 4 NOTES

WRITING RESEARCH REPORT

The notes are mostly extracted (copy paste) from the references provided at the end of this document.

Undertaking Writing

Before a writing endeavour is ventured, it is advisable for students to read previous Master

dissertation to grasp the writing style of research. Reading journal articles will also help.

One sign of inexperienced writers is that they prefer to discuss their proposed study rather than

write about it. It is helpful to write it out quickly as rough as it may be in the first rendering.

The following are recommended:

Early in the process of research, write ideas down rather than talk about them. One

author has talked directly about this concept of writing as thinking (Bailey, 1984).

Zinsser (1983) also discussed the need to get words out of our heads and onto paper.

Advisers react better when they read the ideas on paper than when they hear and discuss

a research topic with a student or colleague. When a researcher renders ideas on paper,

a reader can visualize the final product, actually see how it looks, and begin to clarify

ideas. The concept of working ideas out on paper has served many experienced writers

well. Before designing a proposal, draft a one- to two-page overview of your project

and have your adviser approve the direction of your proposed study. This draft might

contain the essential information: the research problem being addressed, the purpose of

the study, the central questions being asked, the source of data, and the significance of

the project for different audiences. It might also be useful to draft several one- to two

page statements on different topics and see which one your adviser likes best and feels

would make the best contribution to your field.

Work through several drafts of a proposal rather than trying to polish the first draft. It

is illuminating to see how people think on paper. Do not edit your proposal at the

early-draft stage. Instead, consider Franklin’s (1986) three-stage model, which have

been found useful in developing proposals and in our scholarly writing:

o First, develop an outline; it could be a sentence or word outline or a visual

map.

o Write out a draft and then shift and sort ideas, moving around entire

paragraphs in the manuscript.

o Finally, edit and polish each sentence.

Project Report Structure

For a Master’s dissertation, there are generally five chapters to report:

Chapter 1 – Introduction

Chapter 2 – Literature Review

Chapter 3 – Data and Methodology

Chapter 4 – Results and Analysis

Chapter 5 – Conclusion

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

At times, often for PhD thesis, the Literature Review may be broken down into two or three

chapters; depending on how broad the literature themes are. Same goes with Results and

Analysis. The Results and Analysis chapter may be translated into more chapters depending on

the research findings and methodology used. Since this course focuses on developing a research

proposal and quantitative research, only chapters on the research proposal based on quantitative

method are discussed in depth.

A research proposal is an overall plan, scheme, structure and strategy designed to obtain

answers to the research questions or problems that constitute your research project. A research

proposal should outline the various tasks you plan to undertake to fulfil your research

objectives, test hypotheses (if any) or obtain answers to your research questions. It should also

state your reasons for undertaking the study. Broadly, a research proposal’s main function is to

detail the operational plan for obtaining answers to your research questions. In doing so it

ensures and reassures the reader of the validity of the methodology for obtaining answers to

your research questions accurately and objectively. In order to achieve this function, a research

proposal must tell you, your research supervisor and reviewers the following information about

your study:

what you are proposing to do;

how you plan to find answers to what you are proposing;

why you selected the proposed strategies of investigation.

A research proposal should contain the following sections:

An introduction – Background of the study, problem statement, research objectives,

research questions, and significance of the study

A brief literature review – break down into subsections according to the literature

themes

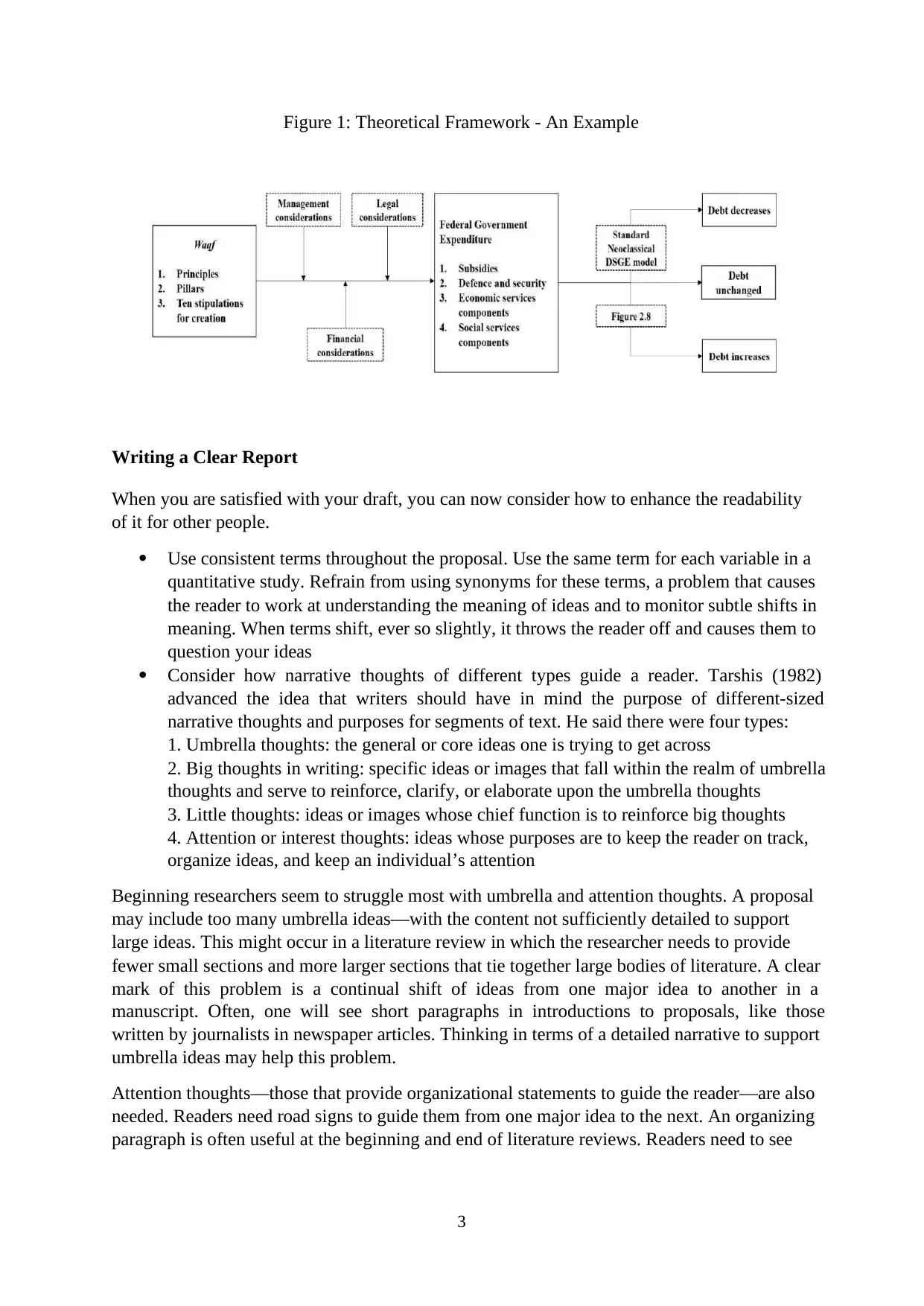

A theoretical framework

A theoretical framework consists of concepts, together with their definitions, and

existing theory/theories that are used for your particular study. The theoretical

framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are

relevant to the topic of your research paper and that will relate it to the broader fields

of knowledge in the class you are taking. The theoretical framework is not something

that is found readily available in the literature. You must review course readings and

pertinent research literature for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the

research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its

appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power. Figure 1 shows an

example of a theoretical framework taken from the instructor’s PhD thesis.

Data and methodology – research design, hypothesis, research instrument, sampling

methods, sampling size, and methods of data analysis

Conclusion – sum up the main points of the proposal and limitations of the study

List of references

At times, often for PhD thesis, the Literature Review may be broken down into two or three

chapters; depending on how broad the literature themes are. Same goes with Results and

Analysis. The Results and Analysis chapter may be translated into more chapters depending on

the research findings and methodology used. Since this course focuses on developing a research

proposal and quantitative research, only chapters on the research proposal based on quantitative

method are discussed in depth.

A research proposal is an overall plan, scheme, structure and strategy designed to obtain

answers to the research questions or problems that constitute your research project. A research

proposal should outline the various tasks you plan to undertake to fulfil your research

objectives, test hypotheses (if any) or obtain answers to your research questions. It should also

state your reasons for undertaking the study. Broadly, a research proposal’s main function is to

detail the operational plan for obtaining answers to your research questions. In doing so it

ensures and reassures the reader of the validity of the methodology for obtaining answers to

your research questions accurately and objectively. In order to achieve this function, a research

proposal must tell you, your research supervisor and reviewers the following information about

your study:

what you are proposing to do;

how you plan to find answers to what you are proposing;

why you selected the proposed strategies of investigation.

A research proposal should contain the following sections:

An introduction – Background of the study, problem statement, research objectives,

research questions, and significance of the study

A brief literature review – break down into subsections according to the literature

themes

A theoretical framework

A theoretical framework consists of concepts, together with their definitions, and

existing theory/theories that are used for your particular study. The theoretical

framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are

relevant to the topic of your research paper and that will relate it to the broader fields

of knowledge in the class you are taking. The theoretical framework is not something

that is found readily available in the literature. You must review course readings and

pertinent research literature for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the

research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its

appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power. Figure 1 shows an

example of a theoretical framework taken from the instructor’s PhD thesis.

Data and methodology – research design, hypothesis, research instrument, sampling

methods, sampling size, and methods of data analysis

Conclusion – sum up the main points of the proposal and limitations of the study

List of references

3

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework - An Example

Writing a Clear Report

When you are satisfied with your draft, you can now consider how to enhance the readability

of it for other people.

Use consistent terms throughout the proposal. Use the same term for each variable in a

quantitative study. Refrain from using synonyms for these terms, a problem that causes

the reader to work at understanding the meaning of ideas and to monitor subtle shifts in

meaning. When terms shift, ever so slightly, it throws the reader off and causes them to

question your ideas

Consider how narrative thoughts of different types guide a reader. Tarshis (1982)

advanced the idea that writers should have in mind the purpose of different-sized

narrative thoughts and purposes for segments of text. He said there were four types:

1. Umbrella thoughts: the general or core ideas one is trying to get across

2. Big thoughts in writing: specific ideas or images that fall within the realm of umbrella

thoughts and serve to reinforce, clarify, or elaborate upon the umbrella thoughts

3. Little thoughts: ideas or images whose chief function is to reinforce big thoughts

4. Attention or interest thoughts: ideas whose purposes are to keep the reader on track,

organize ideas, and keep an individual’s attention

Beginning researchers seem to struggle most with umbrella and attention thoughts. A proposal

may include too many umbrella ideas—with the content not sufficiently detailed to support

large ideas. This might occur in a literature review in which the researcher needs to provide

fewer small sections and more larger sections that tie together large bodies of literature. A clear

mark of this problem is a continual shift of ideas from one major idea to another in a

manuscript. Often, one will see short paragraphs in introductions to proposals, like those

written by journalists in newspaper articles. Thinking in terms of a detailed narrative to support

umbrella ideas may help this problem.

Attention thoughts—those that provide organizational statements to guide the reader—are also

needed. Readers need road signs to guide them from one major idea to the next. An organizing

paragraph is often useful at the beginning and end of literature reviews. Readers need to see

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework - An Example

Writing a Clear Report

When you are satisfied with your draft, you can now consider how to enhance the readability

of it for other people.

Use consistent terms throughout the proposal. Use the same term for each variable in a

quantitative study. Refrain from using synonyms for these terms, a problem that causes

the reader to work at understanding the meaning of ideas and to monitor subtle shifts in

meaning. When terms shift, ever so slightly, it throws the reader off and causes them to

question your ideas

Consider how narrative thoughts of different types guide a reader. Tarshis (1982)

advanced the idea that writers should have in mind the purpose of different-sized

narrative thoughts and purposes for segments of text. He said there were four types:

1. Umbrella thoughts: the general or core ideas one is trying to get across

2. Big thoughts in writing: specific ideas or images that fall within the realm of umbrella

thoughts and serve to reinforce, clarify, or elaborate upon the umbrella thoughts

3. Little thoughts: ideas or images whose chief function is to reinforce big thoughts

4. Attention or interest thoughts: ideas whose purposes are to keep the reader on track,

organize ideas, and keep an individual’s attention

Beginning researchers seem to struggle most with umbrella and attention thoughts. A proposal

may include too many umbrella ideas—with the content not sufficiently detailed to support

large ideas. This might occur in a literature review in which the researcher needs to provide

fewer small sections and more larger sections that tie together large bodies of literature. A clear

mark of this problem is a continual shift of ideas from one major idea to another in a

manuscript. Often, one will see short paragraphs in introductions to proposals, like those

written by journalists in newspaper articles. Thinking in terms of a detailed narrative to support

umbrella ideas may help this problem.

Attention thoughts—those that provide organizational statements to guide the reader—are also

needed. Readers need road signs to guide them from one major idea to the next. An organizing

paragraph is often useful at the beginning and end of literature reviews. Readers need to see

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

the overall organization of the ideas through introductory paragraphs and to be told the most

salient points they should remember in a summary.

Use coherence to add to the readability of the manuscript. Coherence in writing means that the

ideas tie together and logically flow from one sentence to another and from one paragraph to

another. For example, the repetition of the same variable names in the title, the purpose

statement, the research questions, and the review of the literature headings in a quantitative

project illustrate this thinking. This approach builds coherence into the study. Emphasizing a

consistent order whenever independent and dependent variables are mentioned also reinforces

this idea.

On a more detailed level, coherence builds through connecting sentences and paragraphs in the

manuscript. Zinsser (1983) suggested that every sentence should be a logical sequel to the one

that preceded it. The hookand-eye exercise (Wilkinson, 1991) is useful for connecting thoughts

from sentence to sentence and paragraph to paragraph. The basic idea here is that one sentence

builds on the next and sentences in a paragraph build into the next paragraph. The way this

occurs is by specific words that provide a linkage.

From working with broad thoughts and paragraphs, it is recommended to move on to the level

of writing sentences and words. The following ideas about active voice, verb tense, and reduced

fat can strengthen and invigorate scholarly writing for dissertation and thesis proposals:

Use the active voice as much as possible in scholarly writing (APA, 2010). According

to the literary writer Ross-Larson (1982), “If the subject acts, the voice is active. If the

subject is acted on, the voice is passive” (p. 29). In addition, a sign of passive

construction is some variation of an auxiliary verb, such as was. Examples include will

be, have been, and is being. Writers can use the passive construction when the person

acting can logically be left out of the sentence and when what is acted on is the subject

of the rest of the paragraph (Ross-Larson, 1982)

Use strong active verbs appropriate for the passage. Lazy verbs are those that lack

action, commonly called “to be” verbs, such as is or was, or verbs turned into adjectives

or adverbs.

Pay close attention to the tense of your verbs. A common practice exists in using the

past tense to review the literature and report results of past studies. The past tense

represents a commonly used form in quantitative research. The future tense

appropriately indicates that the study will be conducted in the future, a key verb-use for

proposals. Use the present tense to add vigor to a study, especially in the introduction,

as this tense-form frequently occurs in qualitative studies. The APA Publication Manual

(APA, 2010) recommends the past tense (e.g., “Jones reported”) or the present perfect

tense (e.g., “Researchers have reported”) for the literature review and procedures based

on past events, the past tense to describe results (e.g., “stress lowered self-esteem”),

and the present tense (e.g., “the qualitative findings show”) to discuss the results and to

present the conclusions.

Expect to edit and revise drafts of a manuscript to trim the fat. Fat refers to additional

words that are unnecessary to convey the meaning of ideas and need to be edited out.

Writing multiple drafts of a manuscript is standard practice for most writers. The

process typically consists of writing, reviewing, and editing. In the editing process, trim

excess words from sentences, such as piled-up modifiers, excessive prepositions, and

the overall organization of the ideas through introductory paragraphs and to be told the most

salient points they should remember in a summary.

Use coherence to add to the readability of the manuscript. Coherence in writing means that the

ideas tie together and logically flow from one sentence to another and from one paragraph to

another. For example, the repetition of the same variable names in the title, the purpose

statement, the research questions, and the review of the literature headings in a quantitative

project illustrate this thinking. This approach builds coherence into the study. Emphasizing a

consistent order whenever independent and dependent variables are mentioned also reinforces

this idea.

On a more detailed level, coherence builds through connecting sentences and paragraphs in the

manuscript. Zinsser (1983) suggested that every sentence should be a logical sequel to the one

that preceded it. The hookand-eye exercise (Wilkinson, 1991) is useful for connecting thoughts

from sentence to sentence and paragraph to paragraph. The basic idea here is that one sentence

builds on the next and sentences in a paragraph build into the next paragraph. The way this

occurs is by specific words that provide a linkage.

From working with broad thoughts and paragraphs, it is recommended to move on to the level

of writing sentences and words. The following ideas about active voice, verb tense, and reduced

fat can strengthen and invigorate scholarly writing for dissertation and thesis proposals:

Use the active voice as much as possible in scholarly writing (APA, 2010). According

to the literary writer Ross-Larson (1982), “If the subject acts, the voice is active. If the

subject is acted on, the voice is passive” (p. 29). In addition, a sign of passive

construction is some variation of an auxiliary verb, such as was. Examples include will

be, have been, and is being. Writers can use the passive construction when the person

acting can logically be left out of the sentence and when what is acted on is the subject

of the rest of the paragraph (Ross-Larson, 1982)

Use strong active verbs appropriate for the passage. Lazy verbs are those that lack

action, commonly called “to be” verbs, such as is or was, or verbs turned into adjectives

or adverbs.

Pay close attention to the tense of your verbs. A common practice exists in using the

past tense to review the literature and report results of past studies. The past tense

represents a commonly used form in quantitative research. The future tense

appropriately indicates that the study will be conducted in the future, a key verb-use for

proposals. Use the present tense to add vigor to a study, especially in the introduction,

as this tense-form frequently occurs in qualitative studies. The APA Publication Manual

(APA, 2010) recommends the past tense (e.g., “Jones reported”) or the present perfect

tense (e.g., “Researchers have reported”) for the literature review and procedures based

on past events, the past tense to describe results (e.g., “stress lowered self-esteem”),

and the present tense (e.g., “the qualitative findings show”) to discuss the results and to

present the conclusions.

Expect to edit and revise drafts of a manuscript to trim the fat. Fat refers to additional

words that are unnecessary to convey the meaning of ideas and need to be edited out.

Writing multiple drafts of a manuscript is standard practice for most writers. The

process typically consists of writing, reviewing, and editing. In the editing process, trim

excess words from sentences, such as piled-up modifiers, excessive prepositions, and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

“the-of” constructions—for example, “the study of”—that add unnecessary verbiage

(Ross-Larson, 1982).

References

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and

Mixed Methods Approaches. California: SAGE Publications.

Kumar, R. (2011). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners. London:

SAGE Publications.

“the-of” constructions—for example, “the study of”—that add unnecessary verbiage

(Ross-Larson, 1982).

References

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and

Mixed Methods Approaches. California: SAGE Publications.

Kumar, R. (2011). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners. London:

SAGE Publications.

1 out of 5

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.