Non-Invasive Diagnosis of COPD Patients Using EMG and MMG Signals

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/18

|16

|3813

|28

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a comprehensive analysis of using Electromyography (EMG) and Mechanomyography (MMG) signal analysis for the non-invasive diagnosis of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) patients. The study focuses on the diaphragm, neck, and chest wall muscles, examining their activity through signal processing techniques. The introduction highlights COPD's global impact and the limitations of current diagnostic methods, emphasizing the potential of non-invasive approaches. The literature review explores various methods, including adaptive filter analysis and the use of adaptive noise cancellers, to improve signal quality and accurately detect respiratory onset. The report evaluates tools for better analysis of COPD patients and discusses the application of fixed sample entropy (fSE) and adaptive filtering to remove electrocardiographic (ECG) interference. The discussion section synthesizes the findings, comparing the performance of different methods and addressing the challenges in accurately detecting respiratory onset. The study concludes with the effectiveness of EMG and MMG analysis in COPD diagnosis and suggests future research directions. The study provides detailed insights into the methods, results, and implications of the study.

Diaphragm, Neck and Chest Wall Muscles Activity in COPD patients for Non-Invasive

Diagnosis using EMG and MMG

Signal Analysis

Diagnosis using EMG and MMG

Signal Analysis

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Table of Contents

Introduction.................................................................................................................................................3

Critical evaluation:......................................................................................................................................4

Literature Review........................................................................................................................................5

Evaluating tool to understand the better analysis of Copd patient.............................................................5

Adaptive Filter analysis:...............................................................................................................................6

Use of Adaptive Noise Canceller..................................................................................................................7

Discussion...................................................................................................................................................8

Conclusions...............................................................................................................................................11

Reference...................................................................................................................................................12

Appendix:..................................................................................................................................................14

Introduction.................................................................................................................................................3

Critical evaluation:......................................................................................................................................4

Literature Review........................................................................................................................................5

Evaluating tool to understand the better analysis of Copd patient.............................................................5

Adaptive Filter analysis:...............................................................................................................................6

Use of Adaptive Noise Canceller..................................................................................................................7

Discussion...................................................................................................................................................8

Conclusions...............................................................................................................................................11

Reference...................................................................................................................................................12

Appendix:..................................................................................................................................................14

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is fourth foremostreason of death in the world .

Due to ageing of the population and continuation of risk factors, this problem will keep

increasing in the coming decades. The disease is characterized by an airway obstruction leading

to airflow limitation and, as a consequence, persisted respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea and

production of sputum (Estrada et al. 2016). Last-stage COPD patient normally suffers chronic

hypercapnic respiratory failure, which is accompanying with the end-of-life. Long-term

application of nocturnal intermittent non-invasive ventilation (NIV) in sufferer with chronic

hypercapnic respiratory failure due to neuromuscular and thoracic restrictive disorders improves

clinical outcomes and survival. However, this therapy has long been controversial in COPD

patients [3, 4]. High-intensity NIV is well-defined as a mode of ventilation that delivers

sufficient inspiratory progressive airway pressure in arrangement with higher backup breathing

incidence to decrease arterial carbon dioxide levels. However, for some patients, adapting to

high-intensity NIV is difficult and compliance rates in clinical practice are therefore sometimes

disappointing. Furthermore, the response to NIV in context of progress in gas altercation and

patient-centered results such as improvement in healthy quality of life is variable between

patients, despite the application of high-intensity NIV. A reason for a more prolonged adaption

period, lower compliance rates and less effective ventilation might be the occurrence of patient-

ventilator asynchrony with high-intensity NIV. The surface diaphragm electromyography

(EMGdi) indicatordelivers a real-time ancillary measure of neural respiratory drive that shows

the load on respiratory muscles (Stocks and quanjer, 2015). Its non-invasive nature makes the

method extremely useful during NIV; both to visually detect patient-ventilator asynchrony, and

for repeated measurements (Quanjer et al. 2012). However, for longer recordings, such as whole

night recordings, visual inspection is burdensome and time-consuming. In addition, NIV is

normally applied during sleep. Thus, there is a clear need to develop an instinctiveprocess to

reliably detect the respiratory onset from the EMGdi signal. This is crucial since the timing of

respiratory effort versus the timing of the ventilator pressure wave determines the control of

ventilation. Nevertheless, the EMGdi signal is heavily contaminated by the electrocardiographic

(ECG) activity, compromising inspiratory onset detection.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is fourth foremostreason of death in the world .

Due to ageing of the population and continuation of risk factors, this problem will keep

increasing in the coming decades. The disease is characterized by an airway obstruction leading

to airflow limitation and, as a consequence, persisted respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea and

production of sputum (Estrada et al. 2016). Last-stage COPD patient normally suffers chronic

hypercapnic respiratory failure, which is accompanying with the end-of-life. Long-term

application of nocturnal intermittent non-invasive ventilation (NIV) in sufferer with chronic

hypercapnic respiratory failure due to neuromuscular and thoracic restrictive disorders improves

clinical outcomes and survival. However, this therapy has long been controversial in COPD

patients [3, 4]. High-intensity NIV is well-defined as a mode of ventilation that delivers

sufficient inspiratory progressive airway pressure in arrangement with higher backup breathing

incidence to decrease arterial carbon dioxide levels. However, for some patients, adapting to

high-intensity NIV is difficult and compliance rates in clinical practice are therefore sometimes

disappointing. Furthermore, the response to NIV in context of progress in gas altercation and

patient-centered results such as improvement in healthy quality of life is variable between

patients, despite the application of high-intensity NIV. A reason for a more prolonged adaption

period, lower compliance rates and less effective ventilation might be the occurrence of patient-

ventilator asynchrony with high-intensity NIV. The surface diaphragm electromyography

(EMGdi) indicatordelivers a real-time ancillary measure of neural respiratory drive that shows

the load on respiratory muscles (Stocks and quanjer, 2015). Its non-invasive nature makes the

method extremely useful during NIV; both to visually detect patient-ventilator asynchrony, and

for repeated measurements (Quanjer et al. 2012). However, for longer recordings, such as whole

night recordings, visual inspection is burdensome and time-consuming. In addition, NIV is

normally applied during sleep. Thus, there is a clear need to develop an instinctiveprocess to

reliably detect the respiratory onset from the EMGdi signal. This is crucial since the timing of

respiratory effort versus the timing of the ventilator pressure wave determines the control of

ventilation. Nevertheless, the EMGdi signal is heavily contaminated by the electrocardiographic

(ECG) activity, compromising inspiratory onset detection.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Critical evaluation:

A number of methods have been used to estimate the envelope of EMGdi and automatically

identify inspiratory onset in the journal "Inspiratory muscle activation increases with COPD

severity as confirmed by non-invasive mechanographic" - by Leonardo Sarlabous. Recently,

fixed sample entropy (fSE) has proved to be a more robust technique to estimate the amplitude

variation in respiratory EMGdisignals. In addition, fSE permits extracting the EMGdi envelope

without requiring a prior removal of QRS complexes thus it is identified as the research

relevancy. However, poor EMGdi signal quality or high ECG interference can reduce the

robustness of fSE. The use of adaptive filters has also been proposed to remove ECG

interference and then estimate EMGdi amplitude and has made the research accurate as well as

reliable. However, these methods have been evaluated separately and in different contexts and it

lacks in biasness and timeliness. Therefore, there is a clear need to explore whether reducing

ECG interference by adaptive filtering can improve EMGdi envelope estimation and

consequently respiratory onset detection.

In this study, the article" Normative measurement of inspiratory muscles performance by meams

of diaphragm muscle mechanographic signals in CoPD patients during an incremental load

respiratory test”is aimed to compare the performance of previously proposed methods estimating

EMGdi envelope and respiratory onset, to optimize the automatic detection of the onset of neural

respiratory drive in COPD patients initiated on home NIV this includes the relevance of the test.

First, to estimate EMGdi envelope, the use of fSE in combination with adaptive straining was

compared and explored to the RMS-based EMGdi envelope provided by EMG acquisition device

helps in understanding the realistic nature of the study. Formerly, dynamic threshold based on

the kernel density estimation (KDE), applied to the EMGdi envelopes, and was proposed to

detect the respiratory onset. The performance of the onset detection was validated using EMG-

based visual scores completed by two well-trained clinicians and describes the timeliness and

completeness of the research.

A number of methods have been used to estimate the envelope of EMGdi and automatically

identify inspiratory onset in the journal "Inspiratory muscle activation increases with COPD

severity as confirmed by non-invasive mechanographic" - by Leonardo Sarlabous. Recently,

fixed sample entropy (fSE) has proved to be a more robust technique to estimate the amplitude

variation in respiratory EMGdisignals. In addition, fSE permits extracting the EMGdi envelope

without requiring a prior removal of QRS complexes thus it is identified as the research

relevancy. However, poor EMGdi signal quality or high ECG interference can reduce the

robustness of fSE. The use of adaptive filters has also been proposed to remove ECG

interference and then estimate EMGdi amplitude and has made the research accurate as well as

reliable. However, these methods have been evaluated separately and in different contexts and it

lacks in biasness and timeliness. Therefore, there is a clear need to explore whether reducing

ECG interference by adaptive filtering can improve EMGdi envelope estimation and

consequently respiratory onset detection.

In this study, the article" Normative measurement of inspiratory muscles performance by meams

of diaphragm muscle mechanographic signals in CoPD patients during an incremental load

respiratory test”is aimed to compare the performance of previously proposed methods estimating

EMGdi envelope and respiratory onset, to optimize the automatic detection of the onset of neural

respiratory drive in COPD patients initiated on home NIV this includes the relevance of the test.

First, to estimate EMGdi envelope, the use of fSE in combination with adaptive straining was

compared and explored to the RMS-based EMGdi envelope provided by EMG acquisition device

helps in understanding the realistic nature of the study. Formerly, dynamic threshold based on

the kernel density estimation (KDE), applied to the EMGdi envelopes, and was proposed to

detect the respiratory onset. The performance of the onset detection was validated using EMG-

based visual scores completed by two well-trained clinicians and describes the timeliness and

completeness of the research.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Literature Review

Evaluating tool to understand the better analysis of Copd patient

According to the article on clinical study performed at the Department of Pulmonary Diseases of

the University Medical Center Groningen (Groningen, The Netherlands). Nine patients with

COPD initiated on home NIV in the hospital were included in this analysis. All patients

participated in a randomized controlled trial of which investigating respiratory EMG and patient-

ventilator asynchrony during NIV initiation was a secondary objective. Both studies, including

the EMG measurements, were approved by the Ethical Committee Groningen (ClinicalTrials.gov

NCT02652559 and NCT03053973). All patients gave written informed consent for participation

in the trial and for the EMG measurements. TheEMGdi was measured in the COPD patients once

they got used to sleeping with NIV during the night. In 7 patients nocturnal measurements were

performed during the initiation period performed in the hospital after 2–5 nights NIV

acclimatization and titration, and in 2 patients the EMG measurements were performed after a

longer period of NIV used at home (in 1 patient a nocturnal measurement was performed after 6

months NIV use and in the other patient a daytime measurement was performed after more than

2 years NIV use). The EMGdi was measured using two 24 mm surface electrodes.

In this case, EMGdi signals were filtered with a 4th-order zero-phase Butterworth band-pass

filter between 5 Hz and 400 Hz. Power line interference at 50 Hz and its harmonics were

removed using 10th-order zero-phase notch filters. For each patient, one hour of the EMGdi

recording was selected. The EMGdi signals were visually evaluated separately by two

physicians. The visual analysis included the onset annotations of every inspiration (Altintas,

2016). A graphic user interface developed in MATLAB facilitated visually determining the onset

points over the EMGdi signals (see Figure S1). The onset of diaphragm activity was selected as

the point at which the surface EMGdi amplitude exceeds the value of basal expiratory activity.

Respiratory cycles where the visual onset marks significantly differed between both experts (a

difference greater than a specific tolerance value) were considered unreliable and removed from

further analysis. The physicians, based on their clinical experience, set this tolerance value to

150 ms. when the visual onset marks were within the tolerance value, the mean of the two

annotations was considered as the gold standard. This metric provides a more objective onset

Evaluating tool to understand the better analysis of Copd patient

According to the article on clinical study performed at the Department of Pulmonary Diseases of

the University Medical Center Groningen (Groningen, The Netherlands). Nine patients with

COPD initiated on home NIV in the hospital were included in this analysis. All patients

participated in a randomized controlled trial of which investigating respiratory EMG and patient-

ventilator asynchrony during NIV initiation was a secondary objective. Both studies, including

the EMG measurements, were approved by the Ethical Committee Groningen (ClinicalTrials.gov

NCT02652559 and NCT03053973). All patients gave written informed consent for participation

in the trial and for the EMG measurements. TheEMGdi was measured in the COPD patients once

they got used to sleeping with NIV during the night. In 7 patients nocturnal measurements were

performed during the initiation period performed in the hospital after 2–5 nights NIV

acclimatization and titration, and in 2 patients the EMG measurements were performed after a

longer period of NIV used at home (in 1 patient a nocturnal measurement was performed after 6

months NIV use and in the other patient a daytime measurement was performed after more than

2 years NIV use). The EMGdi was measured using two 24 mm surface electrodes.

In this case, EMGdi signals were filtered with a 4th-order zero-phase Butterworth band-pass

filter between 5 Hz and 400 Hz. Power line interference at 50 Hz and its harmonics were

removed using 10th-order zero-phase notch filters. For each patient, one hour of the EMGdi

recording was selected. The EMGdi signals were visually evaluated separately by two

physicians. The visual analysis included the onset annotations of every inspiration (Altintas,

2016). A graphic user interface developed in MATLAB facilitated visually determining the onset

points over the EMGdi signals (see Figure S1). The onset of diaphragm activity was selected as

the point at which the surface EMGdi amplitude exceeds the value of basal expiratory activity.

Respiratory cycles where the visual onset marks significantly differed between both experts (a

difference greater than a specific tolerance value) were considered unreliable and removed from

further analysis. The physicians, based on their clinical experience, set this tolerance value to

150 ms. when the visual onset marks were within the tolerance value, the mean of the two

annotations was considered as the gold standard. This metric provides a more objective onset

value that reduces the subjective judgments of single scorers, thus minimizing the imperfect

nature of visual inspection scorers.

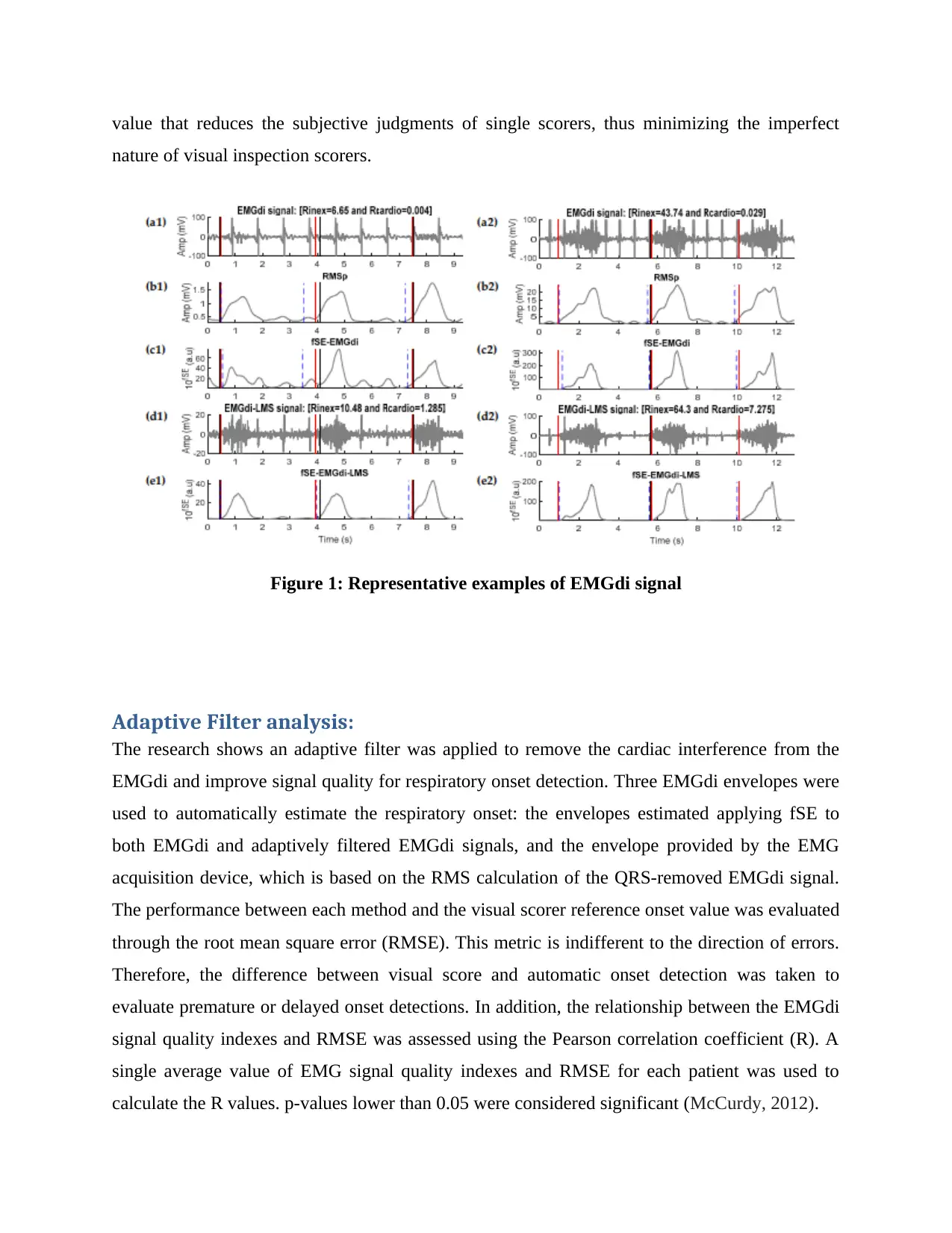

Figure 1: Representative examples of EMGdi signal

Adaptive Filter analysis:

The research shows an adaptive filter was applied to remove the cardiac interference from the

EMGdi and improve signal quality for respiratory onset detection. Three EMGdi envelopes were

used to automatically estimate the respiratory onset: the envelopes estimated applying fSE to

both EMGdi and adaptively filtered EMGdi signals, and the envelope provided by the EMG

acquisition device, which is based on the RMS calculation of the QRS-removed EMGdi signal.

The performance between each method and the visual scorer reference onset value was evaluated

through the root mean square error (RMSE). This metric is indifferent to the direction of errors.

Therefore, the difference between visual score and automatic onset detection was taken to

evaluate premature or delayed onset detections. In addition, the relationship between the EMGdi

signal quality indexes and RMSE was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient (R). A

single average value of EMG signal quality indexes and RMSE for each patient was used to

calculate the R values. p-values lower than 0.05 were considered significant (McCurdy, 2012).

nature of visual inspection scorers.

Figure 1: Representative examples of EMGdi signal

Adaptive Filter analysis:

The research shows an adaptive filter was applied to remove the cardiac interference from the

EMGdi and improve signal quality for respiratory onset detection. Three EMGdi envelopes were

used to automatically estimate the respiratory onset: the envelopes estimated applying fSE to

both EMGdi and adaptively filtered EMGdi signals, and the envelope provided by the EMG

acquisition device, which is based on the RMS calculation of the QRS-removed EMGdi signal.

The performance between each method and the visual scorer reference onset value was evaluated

through the root mean square error (RMSE). This metric is indifferent to the direction of errors.

Therefore, the difference between visual score and automatic onset detection was taken to

evaluate premature or delayed onset detections. In addition, the relationship between the EMGdi

signal quality indexes and RMSE was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient (R). A

single average value of EMG signal quality indexes and RMSE for each patient was used to

calculate the R values. p-values lower than 0.05 were considered significant (McCurdy, 2012).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

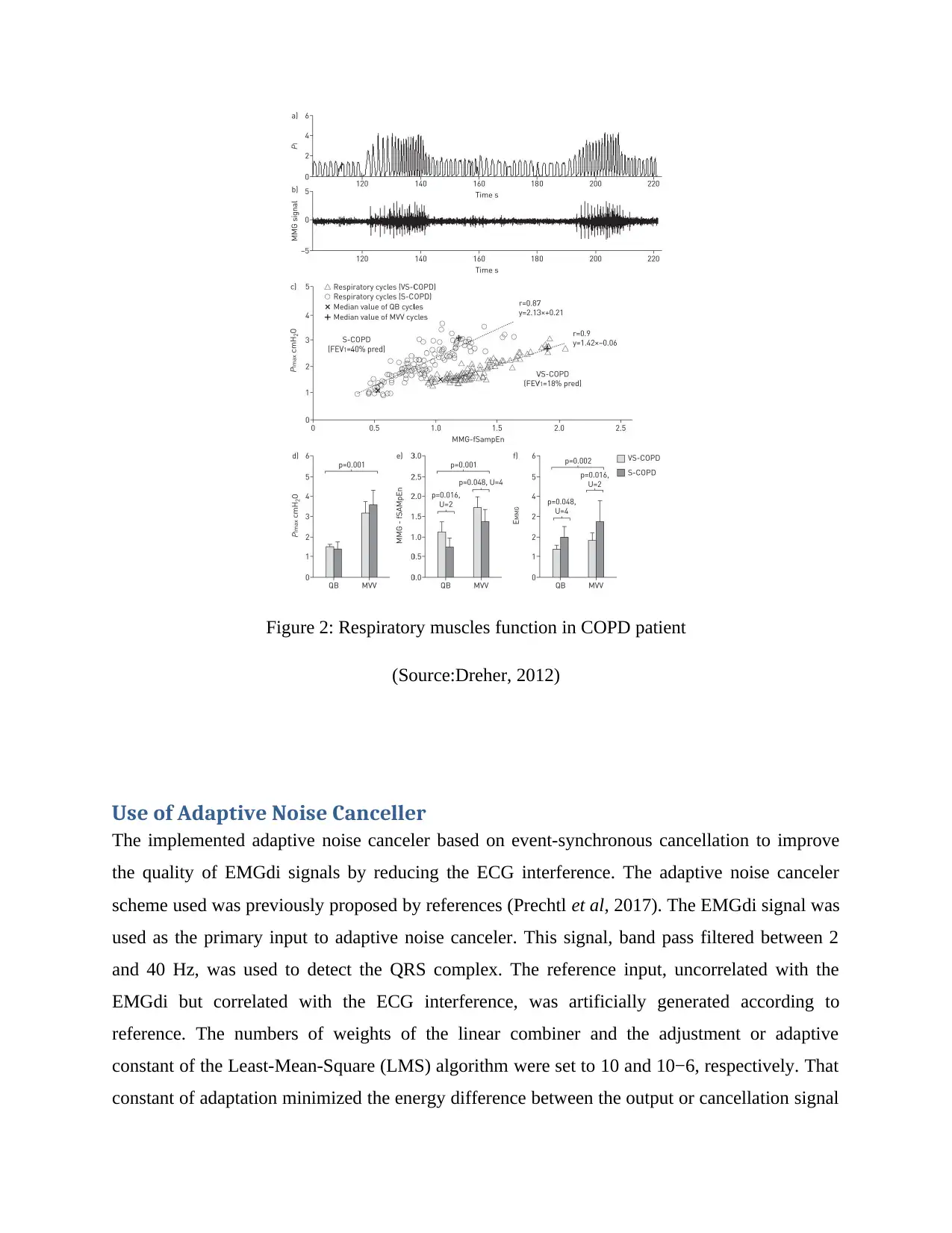

Figure 2: Respiratory muscles function in COPD patient

(Source:Dreher, 2012)

Use of Adaptive Noise Canceller

The implemented adaptive noise canceler based on event-synchronous cancellation to improve

the quality of EMGdi signals by reducing the ECG interference. The adaptive noise canceler

scheme used was previously proposed by references (Prechtl et al, 2017). The EMGdi signal was

used as the primary input to adaptive noise canceler. This signal, band pass filtered between 2

and 40 Hz, was used to detect the QRS complex. The reference input, uncorrelated with the

EMGdi but correlated with the ECG interference, was artificially generated according to

reference. The numbers of weights of the linear combiner and the adjustment or adaptive

constant of the Least-Mean-Square (LMS) algorithm were set to 10 and 10−6, respectively. That

constant of adaptation minimized the energy difference between the output or cancellation signal

(Source:Dreher, 2012)

Use of Adaptive Noise Canceller

The implemented adaptive noise canceler based on event-synchronous cancellation to improve

the quality of EMGdi signals by reducing the ECG interference. The adaptive noise canceler

scheme used was previously proposed by references (Prechtl et al, 2017). The EMGdi signal was

used as the primary input to adaptive noise canceler. This signal, band pass filtered between 2

and 40 Hz, was used to detect the QRS complex. The reference input, uncorrelated with the

EMGdi but correlated with the ECG interference, was artificially generated according to

reference. The numbers of weights of the linear combiner and the adjustment or adaptive

constant of the Least-Mean-Square (LMS) algorithm were set to 10 and 10−6, respectively. That

constant of adaptation minimized the energy difference between the output or cancellation signal

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

and the reference input signal. The EMGdi-LMS signal represents the EMGdi signal adaptively

filtered using the LMS algorithm and fSE-EMGdi-LMS represents the envelope extracted with

fSE.

Discussion

In the present study, a new approach has been developed to automatically detect respiratory

onset from EMGdi. We proposed a novel method using sample entropy to compute the envelope

of EMGdi and a Gaussian-KDE based threshold to non-invasively estimate the onset of the

inspiratory activity in COPD patients initiated on home NIV in the hospital. The envelope,

derived using fSE (mean RMSE = 298 ms), showed slightly higher values in estimating the onset

compared to the RMS-based envelope (mean RMSE = 301 ms) provided by the EMG acquisition

device; both evaluated during day and/or night, and with poor EMG signal-to-noise ratios.

In addition, this study is the first to our knowledge to introduce the combination of the fSE and

the adaptive filtering techniques to improve the estimation of EMGdi envelope when dealing

with low quality EMGdi signals, which further reduced the RMSE to 264 ms. Furthermore, we

proposed EMGdi quality indexes to assess the impact of EMGdi signal quality detecting

inspiratory onset. This showed that there is significant moderate to strong negative correlations

between the quality indices and RMSE. However, as observed for patient 7, the LMS approach

slightly reduced the Rinex index from 3.65 to 3.29, without compromising the performance of

the automatic onset detections. All automated methods detected the onset before the visual

scores; with a mean premature detection of 159 ms, 152 ms and 196 ms, for fSE-EMGdi, fSE-

EMGdi-LMS and RMSp, respectively. The mean and dispersion of onset detection errors were

higher for patients with lower EMGdi signal quality (Duiverman et al. 2015). The estimation of

inspiratory onset is the necessary key step to detect patient-ventilator asynchrony, which is

normally done by visual inspection. In an attempt to automatize patient-ventilator asynchrony

detection, we showed that it is feasible to automatically detect inspiratory onset from EMGdi.

However, compared to visual analysis, the automatic methods estimate the onset prematurely

with an error ranging from 30 ms to 309 ms, 47 ms to 233 ms, and 89 ms to 255 ms, using fSE-

EMGdi, fSE-EMGdi-LMS and RMSp, respectively.

filtered using the LMS algorithm and fSE-EMGdi-LMS represents the envelope extracted with

fSE.

Discussion

In the present study, a new approach has been developed to automatically detect respiratory

onset from EMGdi. We proposed a novel method using sample entropy to compute the envelope

of EMGdi and a Gaussian-KDE based threshold to non-invasively estimate the onset of the

inspiratory activity in COPD patients initiated on home NIV in the hospital. The envelope,

derived using fSE (mean RMSE = 298 ms), showed slightly higher values in estimating the onset

compared to the RMS-based envelope (mean RMSE = 301 ms) provided by the EMG acquisition

device; both evaluated during day and/or night, and with poor EMG signal-to-noise ratios.

In addition, this study is the first to our knowledge to introduce the combination of the fSE and

the adaptive filtering techniques to improve the estimation of EMGdi envelope when dealing

with low quality EMGdi signals, which further reduced the RMSE to 264 ms. Furthermore, we

proposed EMGdi quality indexes to assess the impact of EMGdi signal quality detecting

inspiratory onset. This showed that there is significant moderate to strong negative correlations

between the quality indices and RMSE. However, as observed for patient 7, the LMS approach

slightly reduced the Rinex index from 3.65 to 3.29, without compromising the performance of

the automatic onset detections. All automated methods detected the onset before the visual

scores; with a mean premature detection of 159 ms, 152 ms and 196 ms, for fSE-EMGdi, fSE-

EMGdi-LMS and RMSp, respectively. The mean and dispersion of onset detection errors were

higher for patients with lower EMGdi signal quality (Duiverman et al. 2015). The estimation of

inspiratory onset is the necessary key step to detect patient-ventilator asynchrony, which is

normally done by visual inspection. In an attempt to automatize patient-ventilator asynchrony

detection, we showed that it is feasible to automatically detect inspiratory onset from EMGdi.

However, compared to visual analysis, the automatic methods estimate the onset prematurely

with an error ranging from 30 ms to 309 ms, 47 ms to 233 ms, and 89 ms to 255 ms, using fSE-

EMGdi, fSE-EMGdi-LMS and RMSp, respectively.

Nevertheless, it should be considered that the variability between visual scorers was very high.

The lack of exact mathematical definition of the EMGdi onset represents a challenging problem .

This is reflected by the percentages of cycles removed, up to 45% in one patient with low

EMGdi signal quality, because the inter-scorer’s difference was very high. Only cycles where the

scorers agreed within a tolerance of 150 ms were included in the analysis. The mean between

both scores was considered the reference onset, which included some error in our analysis, as

both marks could be 150 ms apart. The main source of variability was the onsets that lay close to

QRS complexes. In addition, the visual marks were performed in the EMGdi signal, without the

adaptive filter that reduced ECG interference, which might have negatively influenced the visual

onset detection. This can be observed in Figure 2, where the automatic marks look more reliable

than the visual marks.

Several studies based on sample entropy analysis have properly estimated respiratory onset

without removal of ECG artifacts from good quality EMGdi signals (Zhan et al. 2010). The main

challenge on onset detection studies using the fSE technique is to determine the optimal

parameters. Recommendations for estimating respiratory muscle activity using fSE on EMGdi

for different levels of inspiratory effort developed by a healthy subject in seated position were

established by Estrada et al. (2012). However, such recommendations were not made considering

surface EMGdi signals from COPD patients with home mechanical ventilation. Therefore, we

investigated the effect of fSE parameters: r values of 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 times the standard deviation

of the EMGdi signal excluding ECG interference segments, m = 1 and 2, and overlapping sliding

windows between 0.25 s to 0.5 s on estimation of neural onset. The optimal parameters were set

to m = 1, r = 0.3, and sliding moving window equal to 0.25 s, based on the lowest geometric

mean RMSE found for fSE-EMGdi (276.4 ms) and fSE-EMGdi-LMS (253.7 ms). Interestingly,

the selected parameters were in accordance with the recommendations made by Estrada et al.

[25], and were suitable to extract respiratory muscle activity in COPD patients undergoing NIV.

Other problems related to background noise presented during EMG signal recording and signal

to noise ratio notably could also affect the accuracy of onset detection [31]. In studies with

EMGdi signals, the interference and frequency overlap between ECG and EMGdi signals can

affect the analysis and interpretation of researchers and clinicians. ECG and EMGdi signals

could be viewed as being derived from two dynamic systems with different complexity

characteristics [29]. Despite fSE permits extracting the EMGdi envelope without removing ECG

The lack of exact mathematical definition of the EMGdi onset represents a challenging problem .

This is reflected by the percentages of cycles removed, up to 45% in one patient with low

EMGdi signal quality, because the inter-scorer’s difference was very high. Only cycles where the

scorers agreed within a tolerance of 150 ms were included in the analysis. The mean between

both scores was considered the reference onset, which included some error in our analysis, as

both marks could be 150 ms apart. The main source of variability was the onsets that lay close to

QRS complexes. In addition, the visual marks were performed in the EMGdi signal, without the

adaptive filter that reduced ECG interference, which might have negatively influenced the visual

onset detection. This can be observed in Figure 2, where the automatic marks look more reliable

than the visual marks.

Several studies based on sample entropy analysis have properly estimated respiratory onset

without removal of ECG artifacts from good quality EMGdi signals (Zhan et al. 2010). The main

challenge on onset detection studies using the fSE technique is to determine the optimal

parameters. Recommendations for estimating respiratory muscle activity using fSE on EMGdi

for different levels of inspiratory effort developed by a healthy subject in seated position were

established by Estrada et al. (2012). However, such recommendations were not made considering

surface EMGdi signals from COPD patients with home mechanical ventilation. Therefore, we

investigated the effect of fSE parameters: r values of 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 times the standard deviation

of the EMGdi signal excluding ECG interference segments, m = 1 and 2, and overlapping sliding

windows between 0.25 s to 0.5 s on estimation of neural onset. The optimal parameters were set

to m = 1, r = 0.3, and sliding moving window equal to 0.25 s, based on the lowest geometric

mean RMSE found for fSE-EMGdi (276.4 ms) and fSE-EMGdi-LMS (253.7 ms). Interestingly,

the selected parameters were in accordance with the recommendations made by Estrada et al.

[25], and were suitable to extract respiratory muscle activity in COPD patients undergoing NIV.

Other problems related to background noise presented during EMG signal recording and signal

to noise ratio notably could also affect the accuracy of onset detection [31]. In studies with

EMGdi signals, the interference and frequency overlap between ECG and EMGdi signals can

affect the analysis and interpretation of researchers and clinicians. ECG and EMGdi signals

could be viewed as being derived from two dynamic systems with different complexity

characteristics [29]. Despite fSE permits extracting the EMGdi envelope without removing ECG

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

interference, the quality of EMGdi is a key factor in robust envelope estimation. Thus, in this

study, for the first time, we proposed EMG quality indices and a combined adaptive filter with

fSE to detect respiratory onset when dealing with challenging EMGdi signals. These quality

indices enabled quantifying the performance of adaptive filtering. Although the ECG

interference was not completely removed, the quality of the EMGdi signal improved, which

enhanced the fSE performance and the automatic onset detection. Nevertheless, despite being

beneficial in low quality signals, adaptive filtering is very time consuming and could be avoided

when working with high quality signals since the improvement could be minimal. Patient-

ventilator interaction is generally evaluated through indirect estimates of neural onset time based

on a drop in esophageal pressure and the onset of airflow at the mouth. However, indirect

estimates of neural onset can be affected by physiological factors such as intrinsic positive end-

expiratory pressure (PEEPi), or mechanical changes of rib cage (Kondili et al. 2007). Therefore,

more direct measures of respiratory muscle electrical activity have been proposed to alleviate

imprecisions whilst using surrogate estimates of neural onset in mechanical ventilation. Although

it is possible to detect diaphragm EMG with esophageal or even needle electrodes, these invasive

methods are impractical in patients on chronic home NIV. Therefore, we focused on using

surface EMG, being aware of its drawbacks in terms of more signal noise and crosstalk by other

muscles, to detect respiratory neural drive in patients on home mechanical ventilation. The

present study does have certain limitations. Firstly, it is a study with a relatively small sample

size that could limit the generalization of the results. A second limitation is that despite the visual

EMG onset detection approach being the gold standard and considered to provide accurate onset

detection; this method strongly depends on the experience of the expert. It is highly subjective

and with poor reproducibility, and thus could be heavily biased by personal skills (Dreher et al.

2012). A third limitation is the fact that the EMGdi signals, unlike EMG signals recorded in

other muscles, have low signal-to-noise ratio and the manual annotations are more difficult to

make. Therefore, in future works, we plan to make manual annotations over the EMGdi-LMS

signals and compare them with those made on the EMGdi signal. Another limitation of the study

is that the implemented adaptive noise canceler filter was based on a fixed ECG template. In the

future, we will investigate whether generating an adaptive noise canceler that better represents

the variability of the cardiac pattern, improves the cancelation of ECG interference. In this sense,

different templates obtained every 5 min will be used instead of single template. We will also

study, for the first time, we proposed EMG quality indices and a combined adaptive filter with

fSE to detect respiratory onset when dealing with challenging EMGdi signals. These quality

indices enabled quantifying the performance of adaptive filtering. Although the ECG

interference was not completely removed, the quality of the EMGdi signal improved, which

enhanced the fSE performance and the automatic onset detection. Nevertheless, despite being

beneficial in low quality signals, adaptive filtering is very time consuming and could be avoided

when working with high quality signals since the improvement could be minimal. Patient-

ventilator interaction is generally evaluated through indirect estimates of neural onset time based

on a drop in esophageal pressure and the onset of airflow at the mouth. However, indirect

estimates of neural onset can be affected by physiological factors such as intrinsic positive end-

expiratory pressure (PEEPi), or mechanical changes of rib cage (Kondili et al. 2007). Therefore,

more direct measures of respiratory muscle electrical activity have been proposed to alleviate

imprecisions whilst using surrogate estimates of neural onset in mechanical ventilation. Although

it is possible to detect diaphragm EMG with esophageal or even needle electrodes, these invasive

methods are impractical in patients on chronic home NIV. Therefore, we focused on using

surface EMG, being aware of its drawbacks in terms of more signal noise and crosstalk by other

muscles, to detect respiratory neural drive in patients on home mechanical ventilation. The

present study does have certain limitations. Firstly, it is a study with a relatively small sample

size that could limit the generalization of the results. A second limitation is that despite the visual

EMG onset detection approach being the gold standard and considered to provide accurate onset

detection; this method strongly depends on the experience of the expert. It is highly subjective

and with poor reproducibility, and thus could be heavily biased by personal skills (Dreher et al.

2012). A third limitation is the fact that the EMGdi signals, unlike EMG signals recorded in

other muscles, have low signal-to-noise ratio and the manual annotations are more difficult to

make. Therefore, in future works, we plan to make manual annotations over the EMGdi-LMS

signals and compare them with those made on the EMGdi signal. Another limitation of the study

is that the implemented adaptive noise canceler filter was based on a fixed ECG template. In the

future, we will investigate whether generating an adaptive noise canceler that better represents

the variability of the cardiac pattern, improves the cancelation of ECG interference. In this sense,

different templates obtained every 5 min will be used instead of single template. We will also

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

explore the use of other adaptive filtering algorithms such as the Recursive-Least-Squares

algorithm. 6.

Conclusions

In this work, a new fSE-based approach to detect neural onset from muscle respiratory signals

was proposed for COPD patients during non-invasive ventilation. The performance of fSE was

improved including an adaptive filtering step that allowed us to reduce cardiac interference when

evaluating EMGdi recordings with low signal quality. The fSE combined with the KDE resulted

in a suitable tool for onset detection where the muscle activation profile can be difficult to

evaluate. Our findings suggest that using fSE is promising to detect neural onset from muscle

respiratory signals in COPD patients during non-invasive ventilation. We recommend using fSE

alongside adaptive filtering when EMGdi recordings have low signal-to-noise ratio. More

research is required to further validate our findings in a larger cohort and to investigate whether

it can be used to detect and treat patient-ventilator asynchrony in order to improve clinical

outcomes.

algorithm. 6.

Conclusions

In this work, a new fSE-based approach to detect neural onset from muscle respiratory signals

was proposed for COPD patients during non-invasive ventilation. The performance of fSE was

improved including an adaptive filtering step that allowed us to reduce cardiac interference when

evaluating EMGdi recordings with low signal quality. The fSE combined with the KDE resulted

in a suitable tool for onset detection where the muscle activation profile can be difficult to

evaluate. Our findings suggest that using fSE is promising to detect neural onset from muscle

respiratory signals in COPD patients during non-invasive ventilation. We recommend using fSE

alongside adaptive filtering when EMGdi recordings have low signal-to-noise ratio. More

research is required to further validate our findings in a larger cohort and to investigate whether

it can be used to detect and treat patient-ventilator asynchrony in order to improve clinical

outcomes.

Reference

1. GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the

Diagnosis,Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2018

Report). Availableonline: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-

FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2019).

2. Lopez, A.D., Shibuya, K., Rao, C., Mathers, C.D., Hansell, A.L., Held, L.S., Schmid, V. and

Buist, S., 2006. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections.

European Respiratory Journal, 27(2), pp.397-412.

3. Duiverman, M.L., Huberts, A.S., van Eykern, L.A., Bladder, G. and Wijkstra, P.J., 2017.

respiratory muscle activity and patient–ventilator asynchrony during different settings of

noninvasive ventilation in stable hypercapnic COPD: does high inspiratory pressure lead to

respiratory muscle unloading?. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease, 12, p.243.

4. McCurdy, B.R., 2012. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for acute respiratory failure

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence-based

analysis. Ontario health technology assessment series, 12(8), p.1.

5. Altintas, N., 2016. Update: non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in chronic respiratory

failure due to COPD. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 13(1), pp.110-

121.

6. Dreher, M., Storre, J.H., Schmoor, C. and Windisch, W., 2010. High-intensity versus low-

intensity non-invasive ventilation in patients with stable hypercapnic COPD: a randomised

crossover trial. Thorax, 65(4), pp.303-308.7.

9. Kondili, E., Xirouchaki, N. and Georgopoulos, D., 2007. Modulation and treatment of patient–

ventilator dyssynchrony. Current opinion in critical care, 13(1), pp.84-89.

1. GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the

Diagnosis,Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2018

Report). Availableonline: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-

FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2019).

2. Lopez, A.D., Shibuya, K., Rao, C., Mathers, C.D., Hansell, A.L., Held, L.S., Schmid, V. and

Buist, S., 2006. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections.

European Respiratory Journal, 27(2), pp.397-412.

3. Duiverman, M.L., Huberts, A.S., van Eykern, L.A., Bladder, G. and Wijkstra, P.J., 2017.

respiratory muscle activity and patient–ventilator asynchrony during different settings of

noninvasive ventilation in stable hypercapnic COPD: does high inspiratory pressure lead to

respiratory muscle unloading?. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease, 12, p.243.

4. McCurdy, B.R., 2012. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation for acute respiratory failure

patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence-based

analysis. Ontario health technology assessment series, 12(8), p.1.

5. Altintas, N., 2016. Update: non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in chronic respiratory

failure due to COPD. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 13(1), pp.110-

121.

6. Dreher, M., Storre, J.H., Schmoor, C. and Windisch, W., 2010. High-intensity versus low-

intensity non-invasive ventilation in patients with stable hypercapnic COPD: a randomised

crossover trial. Thorax, 65(4), pp.303-308.7.

9. Kondili, E., Xirouchaki, N. and Georgopoulos, D., 2007. Modulation and treatment of patient–

ventilator dyssynchrony. Current opinion in critical care, 13(1), pp.84-89.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 16

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.