The Effect of Emotional Valence on Masked Repetitive Priming

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/05

|15

|4023

|18

Report

AI Summary

This report presents an experimental study investigating the effects of emotional valence on semantic priming and cognitive load. Conducted with 65 students from the University of Melbourne, the study employed a masked repetitive priming task where participants classified words as positive or negative, with some tasks involving cognitive load. The research explored how reaction times were influenced by the emotional valence of words (positive or negative) and the relationship between related and unrelated primes. The study also incorporated individual difference measures, using the Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Oxford Happiness Scale, to assess the impact of anxiety and happiness levels on priming effects. The results indicated faster reaction times for negative words and significant priming effects in both meaning and cognitive load tasks, particularly for negative words. The findings support the hypotheses that emotional valence influences cognitive processing and that priming effects are modulated by both emotional states and cognitive demands.

Emotional valence words on a level of masked repetitive priming and its effect

Student name: Jullie Franciska Indriani

Student id: 102132206

Due date: Monday, 13th of January 2020

Word count: 1700

1 | P a g e

Student name: Jullie Franciska Indriani

Student id: 102132206

Due date: Monday, 13th of January 2020

Word count: 1700

1 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Abstract

The study and the included experiments aimed to evaluate the influence of semantic

priming on different individuals on the basis of their perceived difference depending on the

conscious and unconscious effort to recognize and identify during the experiments. A total of

three experiments were carried out with a group of 65 students from the University of

Melbourne who all claimed English to be their Native language. The first experiment, namely

the meaning experiment was to determine the way they connect the semantics of the meaning

of the word for them as positive, negative or neutral. The second experiment and its result

were based on two scales- Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (SSTAI) and Oxford

Happiness Scale (OHS) for the evaluation to be based on and easier to recognize the

emotional identification of the word as positive and negative. During the experiments, the

second and the third were combined to get a better assessment of the emotional valence and

association. The result was a confirmation of the predominant conception that the reactions

were quicker for the negative words.

Introduction

The study of semantic activation and priming has been at the forefront of arguments

in the area of cognitive recognition of stimuli identification in the formation and association

of words. The task consists of experiments carried out to search the relation between stimuli,

both symbolic and perceptual with the semantic activation which Heyman specified in his

paper – “The Influence of Working Memory Load on Semantic Priming”. The conscious and

unconscious access of an individual is characterised by the responses chartered during the

experiments showing the recognition of negative semantic recognition which is quicker and is

2 | P a g e

The study and the included experiments aimed to evaluate the influence of semantic

priming on different individuals on the basis of their perceived difference depending on the

conscious and unconscious effort to recognize and identify during the experiments. A total of

three experiments were carried out with a group of 65 students from the University of

Melbourne who all claimed English to be their Native language. The first experiment, namely

the meaning experiment was to determine the way they connect the semantics of the meaning

of the word for them as positive, negative or neutral. The second experiment and its result

were based on two scales- Spielberg State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (SSTAI) and Oxford

Happiness Scale (OHS) for the evaluation to be based on and easier to recognize the

emotional identification of the word as positive and negative. During the experiments, the

second and the third were combined to get a better assessment of the emotional valence and

association. The result was a confirmation of the predominant conception that the reactions

were quicker for the negative words.

Introduction

The study of semantic activation and priming has been at the forefront of arguments

in the area of cognitive recognition of stimuli identification in the formation and association

of words. The task consists of experiments carried out to search the relation between stimuli,

both symbolic and perceptual with the semantic activation which Heyman specified in his

paper – “The Influence of Working Memory Load on Semantic Priming”. The conscious and

unconscious access of an individual is characterised by the responses chartered during the

experiments showing the recognition of negative semantic recognition which is quicker and is

2 | P a g e

retained more than the positive words. This was done with the aim of analysing the impact of

stimuli which is processed by the conscious processing given to them through the Learning

Management System. The individuals were observed to be following the experiments

chronologically without anyone changing their direction.

Perceptions were not only based on their awareness of the note and meaning denoting

it but the connotation of the stimuli which arose in them due to the use of the different cases

of the alphabets used. It also enabled the experiment and the researcher to reach the result

whether the awareness was the sole reason for the conception and perception. The conscious

effort which the individual thought was not entirely conscious but it was triggered by the

perception which came into play without them being aware of it. As the same negative word

denoted negative stimuli in the individual when used in the uppercase was taken as positive

under unrelated priming. This came as a breakthrough supporting the hypotheses that the

stimuli are not always the result of the conscious and the aware but rather the cognitive

recognition under the load. The individuals were completing the experiments in the sequence

they were provided without deviating due to the cognitive pressure of retaining the pairs

which they knew would be analysed in the next step. Perception, plays an important role here

such that they knew they would be able to respond better following the sequence signifying

the compliance with the theory of Deutsch that an individual is able to retain information

intentionally that they want to in order to get the result they want. It breaks away from the

assumption that perception is the result of an unconscious recognition and retention of the

information around them. It is instead the conscious effort of an individual which comes into

play, when they are already aware of the experiment. In scenarios such as these, they are able

to manipulate their reaction to permit themselves to fare better.

3 | P a g e

stimuli which is processed by the conscious processing given to them through the Learning

Management System. The individuals were observed to be following the experiments

chronologically without anyone changing their direction.

Perceptions were not only based on their awareness of the note and meaning denoting

it but the connotation of the stimuli which arose in them due to the use of the different cases

of the alphabets used. It also enabled the experiment and the researcher to reach the result

whether the awareness was the sole reason for the conception and perception. The conscious

effort which the individual thought was not entirely conscious but it was triggered by the

perception which came into play without them being aware of it. As the same negative word

denoted negative stimuli in the individual when used in the uppercase was taken as positive

under unrelated priming. This came as a breakthrough supporting the hypotheses that the

stimuli are not always the result of the conscious and the aware but rather the cognitive

recognition under the load. The individuals were completing the experiments in the sequence

they were provided without deviating due to the cognitive pressure of retaining the pairs

which they knew would be analysed in the next step. Perception, plays an important role here

such that they knew they would be able to respond better following the sequence signifying

the compliance with the theory of Deutsch that an individual is able to retain information

intentionally that they want to in order to get the result they want. It breaks away from the

assumption that perception is the result of an unconscious recognition and retention of the

information around them. It is instead the conscious effort of an individual which comes into

play, when they are already aware of the experiment. In scenarios such as these, they are able

to manipulate their reaction to permit themselves to fare better.

3 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The research consisted of a lexical experiment where masked priming played a pivotal

role. It could be reflected to study the priming effect on the individuals based on the cognitive

reaction. Numerous studies are already present in the aspect which shows us the segregation

of words into three distinct divisions. The process of categorizing these responses with

respect to the stimulus produced in an individual is termed as the priming effect. Therefore,

the categorization follows as- the first stimulus is due to the visualization of the formation of

the word which is shown to have a distinct effect on the psychology of onlooker. This is the

orthographic effect where the alphabets and its structure has stimuli or more likely a prompt

which produces an image in the mind of an individual. The second stimulus is the result of

the phonological effect of the word, formed by the combination of alphabets and the sound of

the term produced when spoken. And lastly, the meaning of the word which sometimes again

plays as a prompt which may or may not respond to the actual meaning of the word.

The study is also aimed at finding the semantic priming effect which can be defined

as the unconscious response produced in an individual as a result of being exposed to another

completely unrelated to the given the word. For example, the use of accidents are more

recognized with the use of the term Cars and yet it is not the case with a bicycle. This is due

to the fact known as repetitive semantic, where the human mind unconsciously saves the

result of each stimulus and the next mention or occurrence of these will result in a quicker

recognition (Bodner & Stalinski, 2008). The process continues to be modified each time a

new unrelated prime gets added and later has been observed to take almost the face of an

automatic sequence where the process occurs unconsciously and yet they are not the result of

the unconscious.

4 | P a g e

role. It could be reflected to study the priming effect on the individuals based on the cognitive

reaction. Numerous studies are already present in the aspect which shows us the segregation

of words into three distinct divisions. The process of categorizing these responses with

respect to the stimulus produced in an individual is termed as the priming effect. Therefore,

the categorization follows as- the first stimulus is due to the visualization of the formation of

the word which is shown to have a distinct effect on the psychology of onlooker. This is the

orthographic effect where the alphabets and its structure has stimuli or more likely a prompt

which produces an image in the mind of an individual. The second stimulus is the result of

the phonological effect of the word, formed by the combination of alphabets and the sound of

the term produced when spoken. And lastly, the meaning of the word which sometimes again

plays as a prompt which may or may not respond to the actual meaning of the word.

The study is also aimed at finding the semantic priming effect which can be defined

as the unconscious response produced in an individual as a result of being exposed to another

completely unrelated to the given the word. For example, the use of accidents are more

recognized with the use of the term Cars and yet it is not the case with a bicycle. This is due

to the fact known as repetitive semantic, where the human mind unconsciously saves the

result of each stimulus and the next mention or occurrence of these will result in a quicker

recognition (Bodner & Stalinski, 2008). The process continues to be modified each time a

new unrelated prime gets added and later has been observed to take almost the face of an

automatic sequence where the process occurs unconsciously and yet they are not the result of

the unconscious.

4 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The study clearly forms three hypotheses- the use of two different scales signifying

positive and negative response where the negative response is higher for people with anxiety

and the people scoring higher on the happiness scale responds to the positive words. The

second hypotheses formed is based on the response time for the words and their association

that they react quickly to the related primes quicker than the unrelated prims. The third and

the last hypotheses are the relations between the priming effect and the emotional association

which is found to score higher on the OHS (Hills & Argyle, 2002).

Method

Participants

Sixty-five students from a medium sized university in Melbourne participated in the

experiment. All claimed to be native speakers of English.

Materials

Word stimuli. There were sixty target words, half of which were positive and half of

which were negative. In addition to these target words there were thirty neutral words that

were used as unrelated primes. This created sixty prime target pairs for each valence, thirty of

which were related (repetition priming) and thirty were unrelated. The words in each group

were balanced on psycholinguistic characteristics including word frequency, letter length, and

association strength using the website of Landauer and Dumais. Repetition priming was used

such that each target word (in lower case) was primed by the same word in upper case

(related prime-target pair), or was paired with a prime word (in upper case) of neutral

emotional valence (unrelated prime-target pair). An example negative related repetition

prime-target pair was TORTURE-torture, and the corresponding unrelated prime-target pair

was JETTY-torture.

5 | P a g e

positive and negative response where the negative response is higher for people with anxiety

and the people scoring higher on the happiness scale responds to the positive words. The

second hypotheses formed is based on the response time for the words and their association

that they react quickly to the related primes quicker than the unrelated prims. The third and

the last hypotheses are the relations between the priming effect and the emotional association

which is found to score higher on the OHS (Hills & Argyle, 2002).

Method

Participants

Sixty-five students from a medium sized university in Melbourne participated in the

experiment. All claimed to be native speakers of English.

Materials

Word stimuli. There were sixty target words, half of which were positive and half of

which were negative. In addition to these target words there were thirty neutral words that

were used as unrelated primes. This created sixty prime target pairs for each valence, thirty of

which were related (repetition priming) and thirty were unrelated. The words in each group

were balanced on psycholinguistic characteristics including word frequency, letter length, and

association strength using the website of Landauer and Dumais. Repetition priming was used

such that each target word (in lower case) was primed by the same word in upper case

(related prime-target pair), or was paired with a prime word (in upper case) of neutral

emotional valence (unrelated prime-target pair). An example negative related repetition

prime-target pair was TORTURE-torture, and the corresponding unrelated prime-target pair

was JETTY-torture.

5 | P a g e

Individual differences measures. The state items from the Spielberg State-Trait

Anxiety Inventory (SSTAI; Spielberger et al., 1983) were used to provide a measure of

anxiety, which is a negatively valenced emotion. Items from the Oxford Happiness Scale

(OHS; Argyle et al., 1995) were used to provide a measure of happiness, which is a positive

valenced emotion.

Procedure

Participants reached the experiment via a link on the Learning Management System.

Participants were informed about the sequence of events in the task, and asked to respond as

quickly and as accurately as possible. For each of the three main sections of the experiment,

they completed 10 practice trials followed by 60 experimental trials. The first section of the

experiment asked participants to classify words presented on the screen as negative or

positive emotional valence (Meaning Task). The second task repeated the meaning task, but

this time in a dual task situation (Cognitive Load Task), where they were also asked to

remember a pattern containing four x's and 4 o's in various configurations. After every five

trials of the meaning task, they were asked to recall the current pattern, and then were asked

to remember a new pattern. Following this, they were presented with a list of questions that

they should answer based on their initial intuition without thinking too hard. The questions

were from the two surveys, with the questions from the SSTAI (Spielberger et al., 1983)

being presented first and the OHS second (Hills & Argyle, 2002). The experimental task and

the two short surveys took about 15 minutes to complete.

All of the participants performed the sequence of tasks in the same order without

counterbalancing, beginning with the Meaning Task, followed by the Cognitive Load Task

followed by the surveys. The instructions in the Meaning Task were designed to get

6 | P a g e

Anxiety Inventory (SSTAI; Spielberger et al., 1983) were used to provide a measure of

anxiety, which is a negatively valenced emotion. Items from the Oxford Happiness Scale

(OHS; Argyle et al., 1995) were used to provide a measure of happiness, which is a positive

valenced emotion.

Procedure

Participants reached the experiment via a link on the Learning Management System.

Participants were informed about the sequence of events in the task, and asked to respond as

quickly and as accurately as possible. For each of the three main sections of the experiment,

they completed 10 practice trials followed by 60 experimental trials. The first section of the

experiment asked participants to classify words presented on the screen as negative or

positive emotional valence (Meaning Task). The second task repeated the meaning task, but

this time in a dual task situation (Cognitive Load Task), where they were also asked to

remember a pattern containing four x's and 4 o's in various configurations. After every five

trials of the meaning task, they were asked to recall the current pattern, and then were asked

to remember a new pattern. Following this, they were presented with a list of questions that

they should answer based on their initial intuition without thinking too hard. The questions

were from the two surveys, with the questions from the SSTAI (Spielberger et al., 1983)

being presented first and the OHS second (Hills & Argyle, 2002). The experimental task and

the two short surveys took about 15 minutes to complete.

All of the participants performed the sequence of tasks in the same order without

counterbalancing, beginning with the Meaning Task, followed by the Cognitive Load Task

followed by the surveys. The instructions in the Meaning Task were designed to get

6 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

participants to make a judgement about the words based on them being either of negative

valence or positive valence. In the Cognitive Load Task, the participants were performing

two tasks simultaneously. At the end of each block of trials, the participant were given

performance feedback on latency to response and accuracy.

In terms of the stimulus presentation, the main stimuli always appeared in the centre

of the screen. The timing was as follows: (a) a forward letter mask appeared for 500 ms; (b)

the prime was then presented for 48 ms; (c) a backward mask appeared for 96 ms; and (e) the

target remained on the screen until the participant responded. In the Cognitive Load Task, the

pattern to be remembered appeared on the screen for 2500 ms, then five trials of the Meaning

Task occurred, and then the participant was asked to recall the pattern. The participant had 20

seconds to record their response and were given feedback as to whether the entry was correct

before being shown another pattern to remember.

Results

Data were screened for response times that were less than 200 ms or greater than 1000

ms, and for incomplete data sets. The final data set contained data from 65 participants. To

confirm that participants were successfully completing the meaning judgement in both

conditions tasks, the percentage of correct responses was collated for all conditions, and

presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Mean and SDs of the percentage of correct responses across conditions

Meaning Cognitive Load

Mean SD Mean SD

7 | P a g e

valence or positive valence. In the Cognitive Load Task, the participants were performing

two tasks simultaneously. At the end of each block of trials, the participant were given

performance feedback on latency to response and accuracy.

In terms of the stimulus presentation, the main stimuli always appeared in the centre

of the screen. The timing was as follows: (a) a forward letter mask appeared for 500 ms; (b)

the prime was then presented for 48 ms; (c) a backward mask appeared for 96 ms; and (e) the

target remained on the screen until the participant responded. In the Cognitive Load Task, the

pattern to be remembered appeared on the screen for 2500 ms, then five trials of the Meaning

Task occurred, and then the participant was asked to recall the pattern. The participant had 20

seconds to record their response and were given feedback as to whether the entry was correct

before being shown another pattern to remember.

Results

Data were screened for response times that were less than 200 ms or greater than 1000

ms, and for incomplete data sets. The final data set contained data from 65 participants. To

confirm that participants were successfully completing the meaning judgement in both

conditions tasks, the percentage of correct responses was collated for all conditions, and

presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Mean and SDs of the percentage of correct responses across conditions

Meaning Cognitive Load

Mean SD Mean SD

7 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Percent

correct 94.10 (5.19) 94.97 (4.31)

As can be seen from this table, the mean percent correct for all tasks was well above

90% and there were no obvious differences across the two tasks. The mean percent correct

for the pattern task was 82.11 (SD=15.63), confirming that participants were genuinely

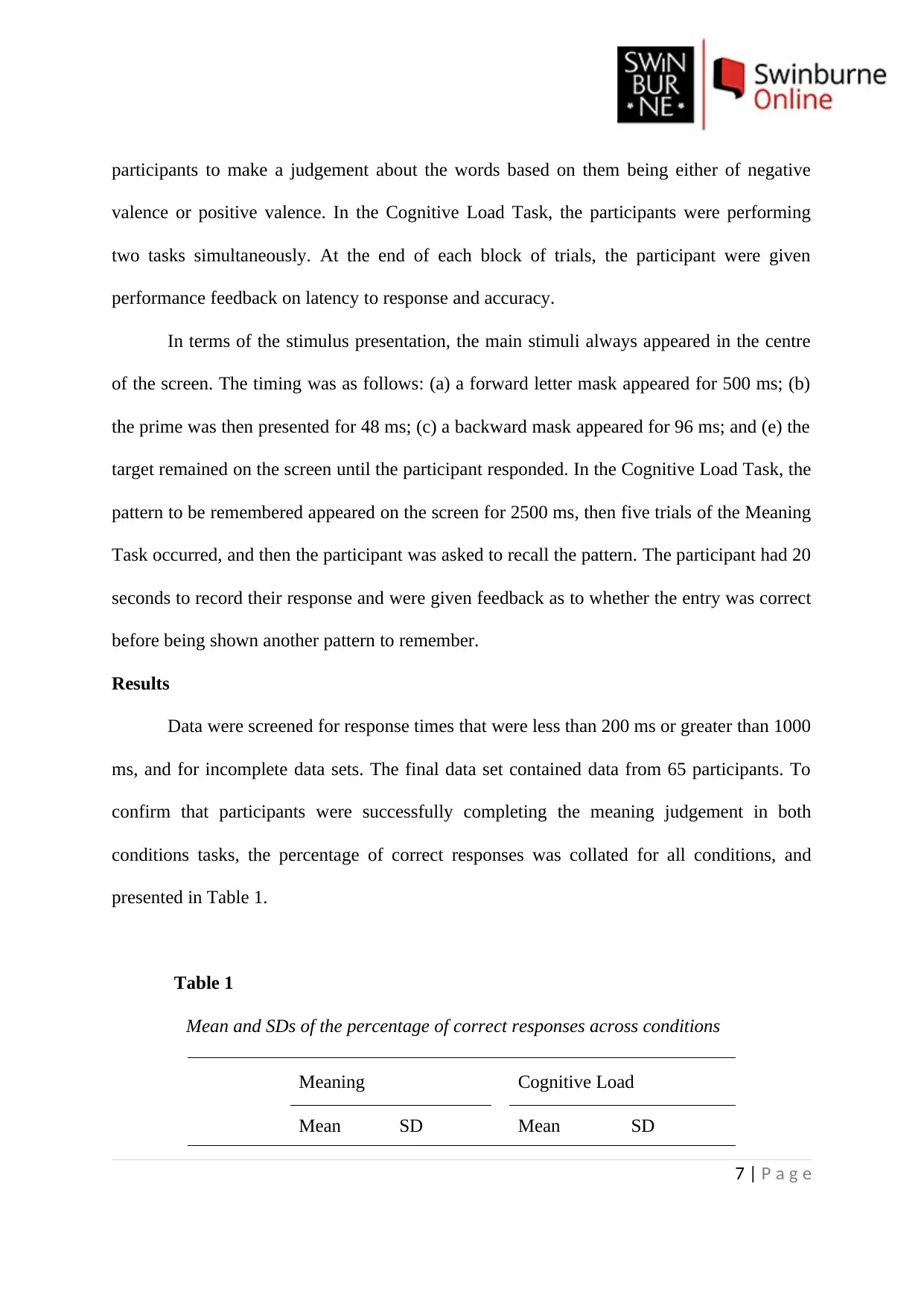

attempting the second task in the cognitive load condition. Reaction times as a function of

emotional valence, task condition and prime relatedness are presented in Figure 1.

NEG MEAN POS MEAN NEG LOAD POS LOAD

550.00

570.00

590.00

610.00

630.00

650.00

670.00

690.00

710.00

730.00

750.00

REL UNREL

Mean Reaction Time (ms)

Figure 1. Mean reaction times and error rates for identical and unrelated prime

target pairs as a function of word valence and task condition. Note: REL=related,

UNREL=unrelated, POS=positive, NEG=negative, MEAN=meaning task,

LOAD=Cognitive load task. The error bars are +-1 SE.

As can be seen from Figure 1, reaction times were faster in the related compared to

the unrelated conditions. This difference in reaction times between related and unrelated

prime-target pairs is referred to as a priming effect. When comparing related trials between

the meaning and cognitive load conditions, reaction times appear generally faster for the load

conditions. However, for the unrelated trials, the reaction times appear slightly slower in the

8 | P a g e

correct 94.10 (5.19) 94.97 (4.31)

As can be seen from this table, the mean percent correct for all tasks was well above

90% and there were no obvious differences across the two tasks. The mean percent correct

for the pattern task was 82.11 (SD=15.63), confirming that participants were genuinely

attempting the second task in the cognitive load condition. Reaction times as a function of

emotional valence, task condition and prime relatedness are presented in Figure 1.

NEG MEAN POS MEAN NEG LOAD POS LOAD

550.00

570.00

590.00

610.00

630.00

650.00

670.00

690.00

710.00

730.00

750.00

REL UNREL

Mean Reaction Time (ms)

Figure 1. Mean reaction times and error rates for identical and unrelated prime

target pairs as a function of word valence and task condition. Note: REL=related,

UNREL=unrelated, POS=positive, NEG=negative, MEAN=meaning task,

LOAD=Cognitive load task. The error bars are +-1 SE.

As can be seen from Figure 1, reaction times were faster in the related compared to

the unrelated conditions. This difference in reaction times between related and unrelated

prime-target pairs is referred to as a priming effect. When comparing related trials between

the meaning and cognitive load conditions, reaction times appear generally faster for the load

conditions. However, for the unrelated trials, the reaction times appear slightly slower in the

8 | P a g e

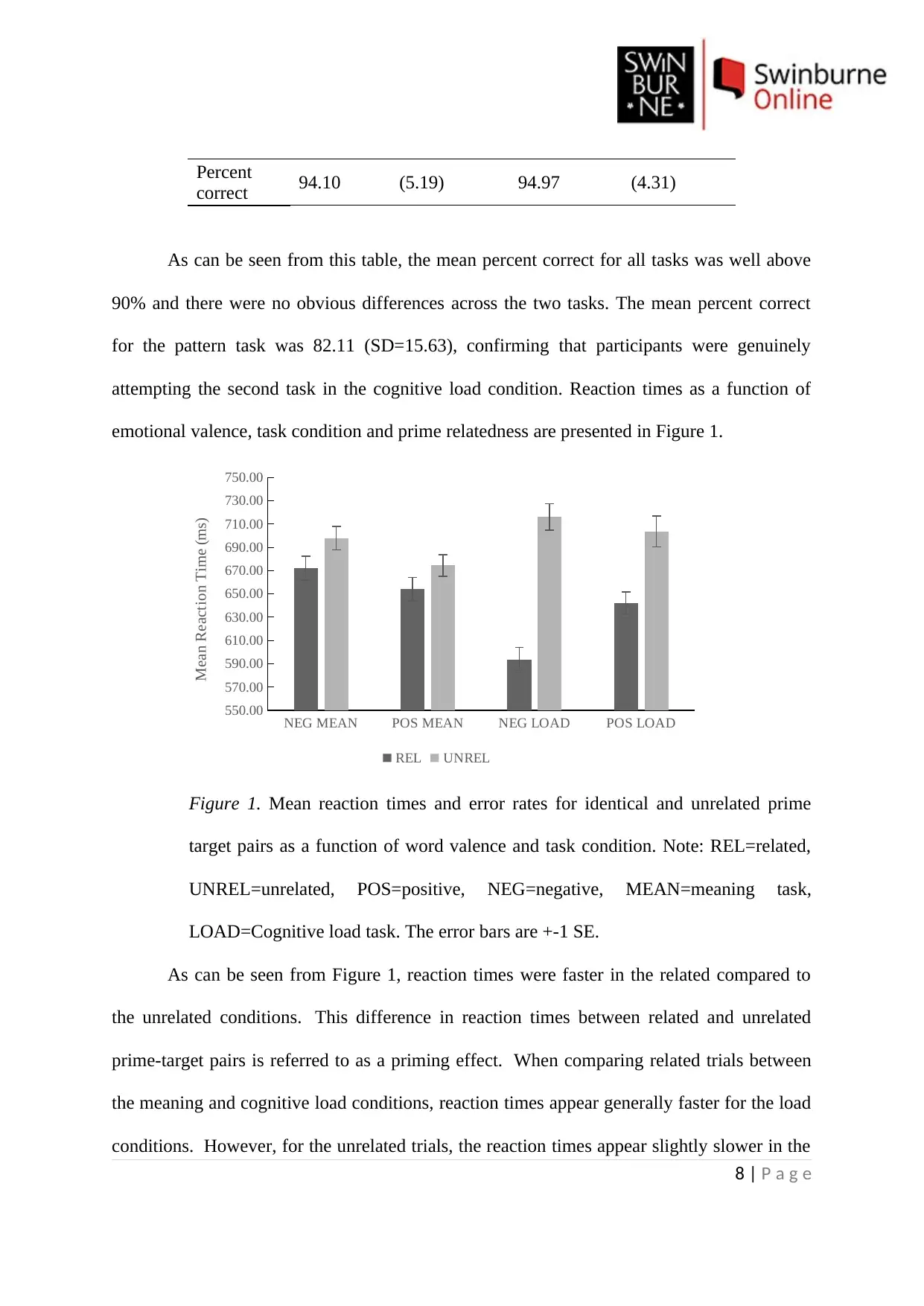

load task. In terms of priming effects, it appears the largest priming effects observed were for

negative words in the cognitive load task, followed by positive words in the same task. The

priming effects for the meaning tasks appear smaller than priming effects in the load

condition and appear relatively similar in size across valence. The same data from Figure 1

are presented to highlight priming effects for negatively and positively valenced words for

the different task conditions in Figure 2.

MEANING LOAD

0.00

20.00

40.00

60.00

80.00

100.00

120.00

140.00

NEGATIVE VALENCE POSITIVE VALENCE

Priming Effect (ms)

Figure 2. Mean priming effect as a function of word valence and task type. The

error bars are +-1 SE.

In order to determine whether the size of the priming effects differed between the

meaning and cognitive load task, a 2 (relatedness) by 2 (task) analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was conducted. This revealed a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1, 64)=115.30,

p<.001), suggesting a significant priming effect overall, and a significant interaction effect

between task and relatedness (F(1, 64)=48.03, p<.001), with priming effects being greater in

the cognitive load condition.

9 | P a g e

negative words in the cognitive load task, followed by positive words in the same task. The

priming effects for the meaning tasks appear smaller than priming effects in the load

condition and appear relatively similar in size across valence. The same data from Figure 1

are presented to highlight priming effects for negatively and positively valenced words for

the different task conditions in Figure 2.

MEANING LOAD

0.00

20.00

40.00

60.00

80.00

100.00

120.00

140.00

NEGATIVE VALENCE POSITIVE VALENCE

Priming Effect (ms)

Figure 2. Mean priming effect as a function of word valence and task type. The

error bars are +-1 SE.

In order to determine whether the size of the priming effects differed between the

meaning and cognitive load task, a 2 (relatedness) by 2 (task) analysis of variance (ANOVA)

was conducted. This revealed a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1, 64)=115.30,

p<.001), suggesting a significant priming effect overall, and a significant interaction effect

between task and relatedness (F(1, 64)=48.03, p<.001), with priming effects being greater in

the cognitive load condition.

9 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

A further two separate 2 (relatedness) by 2 (valence) ANOVAs were conducted to

determine whether differences in priming effects were significant between words of a

positive and negative valence for both the meaning and cognitive load conditions. For the

meaning condition, the analysis revealed a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1,

64)=31.07, p<.001) and valence (F(1, 64)=19.27, p<.001), with RTs for negatively valenced

words being faster than for positively valenced words. However, there was no significant

interaction between relatedness and valence (F(1, 64)=.44, p=.51), suggesting that priming

effects for the meaning conditions were relatively similar across valence. For the cognitive

load condition, the analysis revealed significant main effects for both relatedness (F(1,

64)=94.34, p<.001) and valence (F(1, 64)=4.88, p=.03), again revealing RTs for negative

trials were faster overall compared to positive trials. In contrast to the meaning task, a

significant interaction between relatedness and valence was observed (F(1, 64)=22.06,

p<.001), confirming the size of the priming effect for negatively valenced words was greater

than that of positively valenced words within this cognitive load task condition.

To examine any potential correlations between priming effects and individual

difference variables, the anxiety (STAI) and happiness (OHS) scores were correlated with the

size of the priming effect across emotional valence and task condition. While there was an

expected negative correlation between anxiety and happiness, (r = -.82, p < .001), none of the

correlations of specific interest to the research hypotheses were significant.

Discussion

The study deals with the effect of semantic activation on the emotional valence of

individuals basing on their anxiety quotient determining them on the anxiety and happiness

scale. The experiments carried out during the study aims to evaluate the cognitive response

10 | P a g e

determine whether differences in priming effects were significant between words of a

positive and negative valence for both the meaning and cognitive load conditions. For the

meaning condition, the analysis revealed a significant main effect of relatedness (F(1,

64)=31.07, p<.001) and valence (F(1, 64)=19.27, p<.001), with RTs for negatively valenced

words being faster than for positively valenced words. However, there was no significant

interaction between relatedness and valence (F(1, 64)=.44, p=.51), suggesting that priming

effects for the meaning conditions were relatively similar across valence. For the cognitive

load condition, the analysis revealed significant main effects for both relatedness (F(1,

64)=94.34, p<.001) and valence (F(1, 64)=4.88, p=.03), again revealing RTs for negative

trials were faster overall compared to positive trials. In contrast to the meaning task, a

significant interaction between relatedness and valence was observed (F(1, 64)=22.06,

p<.001), confirming the size of the priming effect for negatively valenced words was greater

than that of positively valenced words within this cognitive load task condition.

To examine any potential correlations between priming effects and individual

difference variables, the anxiety (STAI) and happiness (OHS) scores were correlated with the

size of the priming effect across emotional valence and task condition. While there was an

expected negative correlation between anxiety and happiness, (r = -.82, p < .001), none of the

correlations of specific interest to the research hypotheses were significant.

Discussion

The study deals with the effect of semantic activation on the emotional valence of

individuals basing on their anxiety quotient determining them on the anxiety and happiness

scale. The experiments carried out during the study aims to evaluate the cognitive response

10 | P a g e

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

identifying them under the division of conscious and unconscious. The last or the third

experiment shows the working of the masked semantic priming which can be defined as the

psychological study comprising of lexical experimental activity. It gives us an insight into an

individual’s understanding of the words and the response by them shows their perception

they have in them consciously and unconsciously. The study helps us establish the

association of the working memory also referred to as conscious and the semantic priming

which is the repetition of the same word used as stimuli resulting in the same reaction again

and again. This is also referred to as the automatic priming which is considered to be

unconscious and forms the third hypotheses of the task. It is not proved by the study as the

automatic priming is observed to be emerging as a result of the repetitive priming (Bodner,

Masson & Richard, 2006). The study does show that their response is somewhat intuitive and

instinctive but it is the result of the repeated information saved by the mind and is

unconsciously the result of the conscious recognition of the stimuli.

However, the tables and the results show the verification of the first two hypotheses

establishing the relation between semantic priming and the emotional valence of an

individual through the first and the second experiment. The result of the first experiment

where the individuals were seen to be quicker to allocate the words in the negative section

irrespective of their due to their priming with the negative word is shown to be unable to

recognize them when they are written in the lower case (Neely & Kahan, 2001). The

cognitive load to remember the pairing and their patterns and the time given to recognize

them showed the conscious effort of the individual to retain them. However, it also confirmed

with the help of SSTAI scale, that people who scored higher on their anxiety were prone to

remember the pair denoting the negative while the people scoring high on the OHS scale

11 | P a g e

experiment shows the working of the masked semantic priming which can be defined as the

psychological study comprising of lexical experimental activity. It gives us an insight into an

individual’s understanding of the words and the response by them shows their perception

they have in them consciously and unconsciously. The study helps us establish the

association of the working memory also referred to as conscious and the semantic priming

which is the repetition of the same word used as stimuli resulting in the same reaction again

and again. This is also referred to as the automatic priming which is considered to be

unconscious and forms the third hypotheses of the task. It is not proved by the study as the

automatic priming is observed to be emerging as a result of the repetitive priming (Bodner,

Masson & Richard, 2006). The study does show that their response is somewhat intuitive and

instinctive but it is the result of the repeated information saved by the mind and is

unconsciously the result of the conscious recognition of the stimuli.

However, the tables and the results show the verification of the first two hypotheses

establishing the relation between semantic priming and the emotional valence of an

individual through the first and the second experiment. The result of the first experiment

where the individuals were seen to be quicker to allocate the words in the negative section

irrespective of their due to their priming with the negative word is shown to be unable to

recognize them when they are written in the lower case (Neely & Kahan, 2001). The

cognitive load to remember the pairing and their patterns and the time given to recognize

them showed the conscious effort of the individual to retain them. However, it also confirmed

with the help of SSTAI scale, that people who scored higher on their anxiety were prone to

remember the pair denoting the negative while the people scoring high on the OHS scale

11 | P a g e

showed the tendency to score higher on retaining the information of specific denomination.

This proved that in spite of the cognitive load individual tends to respond according to the

repetitive semantic.

The second experiment also records the response time where the participants verify

the second hypotheses that priming words if followed by words associated in their meaning

were recognized far quicker than the unrelated primes. That the recognition was based on the

meaning of the word proves the people sitting higher on the anxiety scale also happen to be

higher on the emotional valence. But, the people scoring higher in the happiness scale were

shown to be able to retain the negative pairs but on the positive scale reputes our hypotheses

that anxiety builds and higher and stronger on the priming. The third experiment moreover

evaluates their retaining power when they had to remember the patterns of the pairs they have

already recognized in the first and second. The result shows a drastic difference as they were

not able to retain the negative pairs and even if they did, they were quite low in comparison

to the number of positives by both groups. This also shows a deviation and emergence of new

hypotheses that forward priming is far easier fetched than backward priming as it is

dependent on the unconscious or the repetitive priming (Smets et al., 2015). The result

showed that people who recognized the negative pair during the first experiment failed to do

so when the cases of the words were changed. This shows the orthographic effect on the

emotional valence of the participants.

The study was a deviation from the previous researches as it also included the same

set of neutral words which showed how they could help assess the impact of negative and the

positive alike as people were unable to segregate most of them and placed them under

negative and positives. The difficulty in the process shows their cognitive perception of those

12 | P a g e

This proved that in spite of the cognitive load individual tends to respond according to the

repetitive semantic.

The second experiment also records the response time where the participants verify

the second hypotheses that priming words if followed by words associated in their meaning

were recognized far quicker than the unrelated primes. That the recognition was based on the

meaning of the word proves the people sitting higher on the anxiety scale also happen to be

higher on the emotional valence. But, the people scoring higher in the happiness scale were

shown to be able to retain the negative pairs but on the positive scale reputes our hypotheses

that anxiety builds and higher and stronger on the priming. The third experiment moreover

evaluates their retaining power when they had to remember the patterns of the pairs they have

already recognized in the first and second. The result shows a drastic difference as they were

not able to retain the negative pairs and even if they did, they were quite low in comparison

to the number of positives by both groups. This also shows a deviation and emergence of new

hypotheses that forward priming is far easier fetched than backward priming as it is

dependent on the unconscious or the repetitive priming (Smets et al., 2015). The result

showed that people who recognized the negative pair during the first experiment failed to do

so when the cases of the words were changed. This shows the orthographic effect on the

emotional valence of the participants.

The study was a deviation from the previous researches as it also included the same

set of neutral words which showed how they could help assess the impact of negative and the

positive alike as people were unable to segregate most of them and placed them under

negative and positives. The difficulty in the process shows their cognitive perception of those

12 | P a g e

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 15

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.