Industrial Relations: Exploring the Employment Relationship Dynamics

VerifiedAdded on 2022/02/05

|48

|19917

|32

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an in-depth analysis of the employment relationship within the field of industrial relations. It begins by defining industrial relations (IR) and distinguishing it from personnel management (PM) and human resource management (HRM). The report emphasizes the significance of paid employment for both employees and employers, highlighting its role in income, identity, and competitive advantage. It explores the importance of the employment relationship in organizing human resources and addresses the interplay of control and consent. The report further examines key issues in the regulation of work, including labor market participation, pay, and inequality, along with the trends of economically inactive people and the polarization of work. It also includes data and statistics from the UK to illustrate these points and concludes with a discussion of the analytical approaches used within IR as a field of study, and the structure of the book from which the chapter is taken.

1

The Employment Relationship and the

Field of Industrial Relations

Paul Edwards

This paper contains the text of Chapter 1 of the second edition of Industrial Relations:

Theory and Practice in Britain, to be published by Blackwell in January 2003. This is a

wholly revised version, including two completely new chapters, of the book first

published in 1995. The chapter refers to other chapters in the text, which are listed below.

1. The Employment Relationship Paul Edwards

2. The Historical Evolution of British IR Richard Hyman

3. Structure of Economy and Labour Market Peter Nolan and Gary Slater

4. Foreign Multinationals and Industrial Anthony Ferner

Relations Innovation in Britain

5. The State: Economic Management & Colin Crouch

Incomes Policy

6. Labour Law and Industrial Relations: Linda Dickens and Mark Hall

A New Settlement?

7. Management: Systems, Structure and Strategy Keith Sisson & Paul Marginson

8. The Management of William Brown, Paul Marginson, &

Collective Bargaining Janet Walsh

9. Trade Unions and Collective Industrial Action Jeremy Waddington

10. Employee Representation: Shop Stewards and Michael Terry

the New Legal Framework

11. Industrial Relations in the Public Sector Stephen Bach & David Winchester

12. Individualism and Collectivism in Industrial Ian Kessler & John Purcell

Relations

13. New Forms of Work Organization: Still Limited, John F. Geary

Still Controlled, but Still Welcome?

14. Managing without Unions: the Sources and Trevor Colling

Limitations of Individualism

15. Training Ewart Keep & Helen Rainbird

16. The Industrial Relations of a Diverse Workforce Sonia Liff

17. Low Pay and the National Minimum Wage Jill Rubery & Paul Edwards

18. Industrial Relations in Small Firms Richard Scase

19. Industrial Relations, HRM and Performance Peter Nolan and Kathy O’Donnell

Concluding Comments Paul Edwards

The Employment Relationship and the

Field of Industrial Relations

Paul Edwards

This paper contains the text of Chapter 1 of the second edition of Industrial Relations:

Theory and Practice in Britain, to be published by Blackwell in January 2003. This is a

wholly revised version, including two completely new chapters, of the book first

published in 1995. The chapter refers to other chapters in the text, which are listed below.

1. The Employment Relationship Paul Edwards

2. The Historical Evolution of British IR Richard Hyman

3. Structure of Economy and Labour Market Peter Nolan and Gary Slater

4. Foreign Multinationals and Industrial Anthony Ferner

Relations Innovation in Britain

5. The State: Economic Management & Colin Crouch

Incomes Policy

6. Labour Law and Industrial Relations: Linda Dickens and Mark Hall

A New Settlement?

7. Management: Systems, Structure and Strategy Keith Sisson & Paul Marginson

8. The Management of William Brown, Paul Marginson, &

Collective Bargaining Janet Walsh

9. Trade Unions and Collective Industrial Action Jeremy Waddington

10. Employee Representation: Shop Stewards and Michael Terry

the New Legal Framework

11. Industrial Relations in the Public Sector Stephen Bach & David Winchester

12. Individualism and Collectivism in Industrial Ian Kessler & John Purcell

Relations

13. New Forms of Work Organization: Still Limited, John F. Geary

Still Controlled, but Still Welcome?

14. Managing without Unions: the Sources and Trevor Colling

Limitations of Individualism

15. Training Ewart Keep & Helen Rainbird

16. The Industrial Relations of a Diverse Workforce Sonia Liff

17. Low Pay and the National Minimum Wage Jill Rubery & Paul Edwards

18. Industrial Relations in Small Firms Richard Scase

19. Industrial Relations, HRM and Performance Peter Nolan and Kathy O’Donnell

Concluding Comments Paul Edwards

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

The term ‘industrial relations’ (IR) came into common use in Britain and North America

during the 1920s. It has been joined by personnel management (PM) and, since the

1980s, human resource management (HRM). All three denote a practical activity (the

management of people) and an area of academic inquiry. Texts in all three fields

commonly take as their starting point the corporate assertion that ‘people are our most

important asset’: if this is indeed so, there is little further need to justify a text. Yet we

need first to explain what lies behind this apparent axiom. It is then important to highlight

some of the key current issues about the conduct of work in modern Britain. We can then

consider how IR as an academic approach addresses these issues and the distinction

between it and the other two fields of inquiry. Finally, the structure of the book is

explained.

First, some basic explanation. ‘Industry’ is sometimes equated with

manufacturing, as in contrasts between industry and services. ‘Industrial relations’ has in

principle never been so restricted. In practice, however, attention until recently often

focused on certain parts of the economy. These in fact embraced more than

manufacturing to include the public sector for example but there was neglect of small

firms and large parts of the private service sector. Whether or not there were good

reasons for this neglect (and the case is at least arguable), the situation has changed, and

recent research has addressed growing areas of the economy such as call centres. To

avoid confusion some writers prefer the term ‘employment relations’, and if we were

starting from scratch this might be the best label; yet the term ‘IR’ has become

sufficiently embedded that it is retained here to cover relations between manager and

worker in all spheres of economic activity. The focus is employment: all forms of

economic activity in which an employee works under the authority of an employer and

receives a wage in return for his or her labour. Industrial relations thus excludes domestic

labour and also the self-employed and professionals who work on their own account: the

contractual relations between a self-employed plumber and his customers are not

‘industrial relations’, but the relations between a plumbing firm and its employees are. In

the UK self-employment comprises about 12 per cent of people in employment (see

Table 1.1, below). The bulk of the working population is thus in an employment

The term ‘industrial relations’ (IR) came into common use in Britain and North America

during the 1920s. It has been joined by personnel management (PM) and, since the

1980s, human resource management (HRM). All three denote a practical activity (the

management of people) and an area of academic inquiry. Texts in all three fields

commonly take as their starting point the corporate assertion that ‘people are our most

important asset’: if this is indeed so, there is little further need to justify a text. Yet we

need first to explain what lies behind this apparent axiom. It is then important to highlight

some of the key current issues about the conduct of work in modern Britain. We can then

consider how IR as an academic approach addresses these issues and the distinction

between it and the other two fields of inquiry. Finally, the structure of the book is

explained.

First, some basic explanation. ‘Industry’ is sometimes equated with

manufacturing, as in contrasts between industry and services. ‘Industrial relations’ has in

principle never been so restricted. In practice, however, attention until recently often

focused on certain parts of the economy. These in fact embraced more than

manufacturing to include the public sector for example but there was neglect of small

firms and large parts of the private service sector. Whether or not there were good

reasons for this neglect (and the case is at least arguable), the situation has changed, and

recent research has addressed growing areas of the economy such as call centres. To

avoid confusion some writers prefer the term ‘employment relations’, and if we were

starting from scratch this might be the best label; yet the term ‘IR’ has become

sufficiently embedded that it is retained here to cover relations between manager and

worker in all spheres of economic activity. The focus is employment: all forms of

economic activity in which an employee works under the authority of an employer and

receives a wage in return for his or her labour. Industrial relations thus excludes domestic

labour and also the self-employed and professionals who work on their own account: the

contractual relations between a self-employed plumber and his customers are not

‘industrial relations’, but the relations between a plumbing firm and its employees are. In

the UK self-employment comprises about 12 per cent of people in employment (see

Table 1.1, below). The bulk of the working population is thus in an employment

3

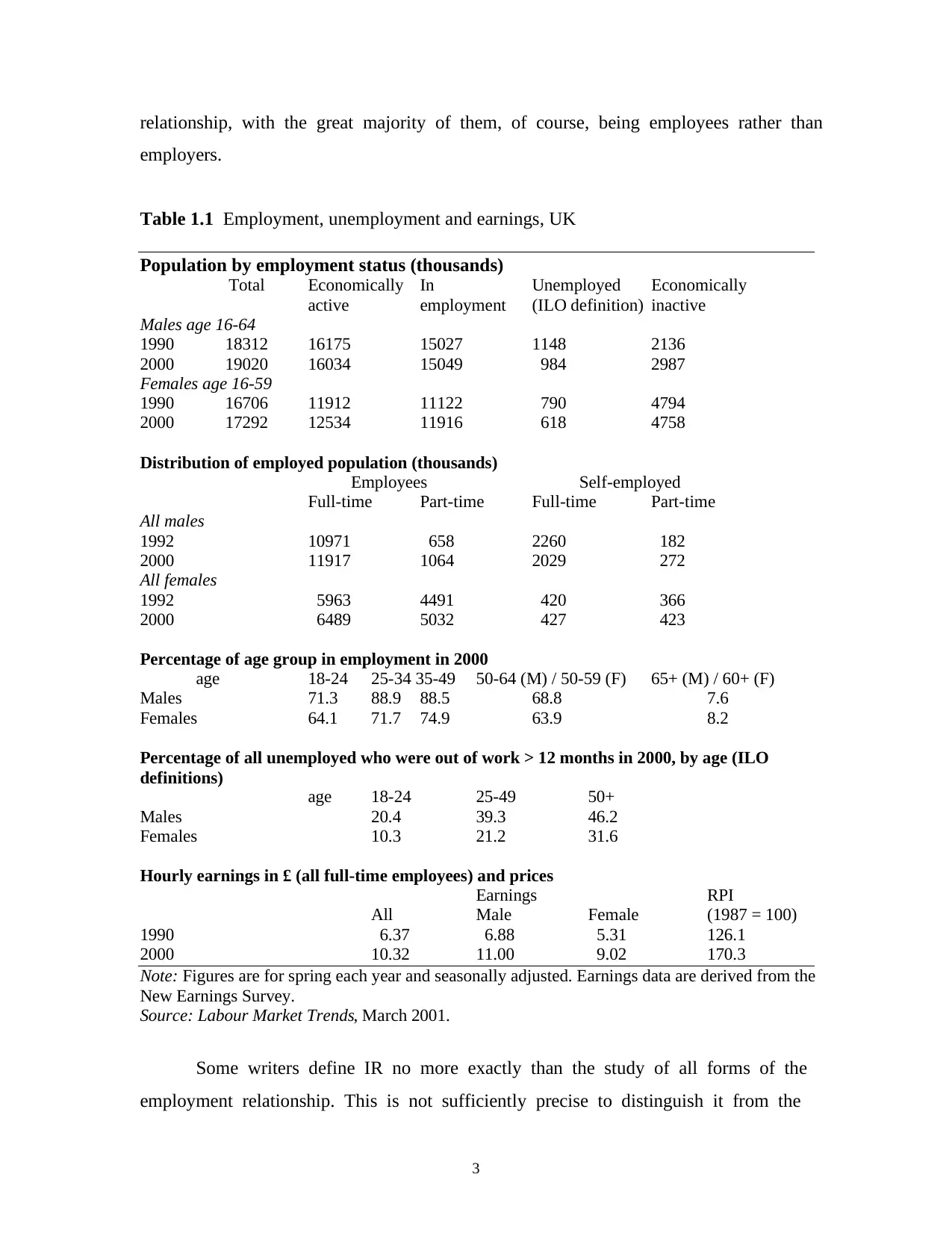

relationship, with the great majority of them, of course, being employees rather than

employers.

Table 1.1 Employment, unemployment and earnings, UK

Population by employment status (thousands)

Total Economically In Unemployed Economically

active employment (ILO definition) inactive

Males age 16-64

1990 18312 16175 15027 1148 2136

2000 19020 16034 15049 984 2987

Females age 16-59

1990 16706 11912 11122 790 4794

2000 17292 12534 11916 618 4758

Distribution of employed population (thousands)

Employees Self-employed

Full-time Part-time Full-time Part-time

All males

1992 10971 658 2260 182

2000 11917 1064 2029 272

All females

1992 5963 4491 420 366

2000 6489 5032 427 423

Percentage of age group in employment in 2000

age 18-24 25-34 35-49 50-64 (M) / 50-59 (F) 65+ (M) / 60+ (F)

Males 71.3 88.9 88.5 68.8 7.6

Females 64.1 71.7 74.9 63.9 8.2

Percentage of all unemployed who were out of work > 12 months in 2000, by age (ILO

definitions)

age 18-24 25-49 50+

Males 20.4 39.3 46.2

Females 10.3 21.2 31.6

Hourly earnings in £ (all full-time employees) and prices

Earnings RPI

All Male Female (1987 = 100)

1990 6.37 6.88 5.31 126.1

2000 10.32 11.00 9.02 170.3

Note: Figures are for spring each year and seasonally adjusted. Earnings data are derived from the

New Earnings Survey.

Source: Labour Market Trends, March 2001.

Some writers define IR no more exactly than the study of all forms of the

employment relationship. This is not sufficiently precise to distinguish it from the

relationship, with the great majority of them, of course, being employees rather than

employers.

Table 1.1 Employment, unemployment and earnings, UK

Population by employment status (thousands)

Total Economically In Unemployed Economically

active employment (ILO definition) inactive

Males age 16-64

1990 18312 16175 15027 1148 2136

2000 19020 16034 15049 984 2987

Females age 16-59

1990 16706 11912 11122 790 4794

2000 17292 12534 11916 618 4758

Distribution of employed population (thousands)

Employees Self-employed

Full-time Part-time Full-time Part-time

All males

1992 10971 658 2260 182

2000 11917 1064 2029 272

All females

1992 5963 4491 420 366

2000 6489 5032 427 423

Percentage of age group in employment in 2000

age 18-24 25-34 35-49 50-64 (M) / 50-59 (F) 65+ (M) / 60+ (F)

Males 71.3 88.9 88.5 68.8 7.6

Females 64.1 71.7 74.9 63.9 8.2

Percentage of all unemployed who were out of work > 12 months in 2000, by age (ILO

definitions)

age 18-24 25-49 50+

Males 20.4 39.3 46.2

Females 10.3 21.2 31.6

Hourly earnings in £ (all full-time employees) and prices

Earnings RPI

All Male Female (1987 = 100)

1990 6.37 6.88 5.31 126.1

2000 10.32 11.00 9.02 170.3

Note: Figures are for spring each year and seasonally adjusted. Earnings data are derived from the

New Earnings Survey.

Source: Labour Market Trends, March 2001.

Some writers define IR no more exactly than the study of all forms of the

employment relationship. This is not sufficiently precise to distinguish it from the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

economics or sociology of work. More importantly, there are some distinct emphases in

an IR approach which give it a specific value in explaining the world of work. These

emphases are discussed below. There has been much debate over the years as to whether

the emphases and analytical preferences of IR make it a discipline, as distinct from a field

of study. The view taken in this chapter (which is not necessarily shared by other

chapters) is that IR is a field of study and not a distinct discipline. Indeed, one of its

strengths is its willingness to draw from different disciplines so that people who

specialize in the field have developed an analytical approach which is more than the sum

total of the application of individual disciplines. Even if this view is accepted, there are

competing views as to the strengths and weaknesses of the approach, and whether it has

responded adequately to the changing nature of work. Some of these issues are addressed

below.

Why is paid employment important? It is important to the employee most

obviously as a source of income. Note that it is not the case that work outside

employment is an easy alternative: at one time, it was argued by some that a combination

of unemployment, self-provisioning and work in the informal economy provided an

alternative to the formal economy, but research found that such work tends to be

additional rather than an alternative to formal employment. Work is also important to the

employee as a means of identity. ‘What do you do for a living?’ is a standard query to

locate a new acquaintance. And what goes on within the employment relationship is

crucial, not only in terms of the pay which is earned but also the conditions under which

it is earned: the degree of autonomy the employee is granted, the safety of the work

environment, the opportunity for training and development, and so on.

For the employer the work relationship is crucial in two different senses. First, it

is commonly argued that capital and technologies are increasingly readily available, so

that a firm’s competitive position depends on the skills and knowledge of its workers.

Some analytical grounding for this argument comes from the resource-based view of the

firm which developed from debates on strategic management. This view sees the firm as

a bundle of assets and argues that it is the configuration of these assets, rather than

positioning in relation to an external market, which is central to competitive advantage

(Wernerfeld 1984; see further Chapter 7). Not surprisingly, HRM and IR writers have

economics or sociology of work. More importantly, there are some distinct emphases in

an IR approach which give it a specific value in explaining the world of work. These

emphases are discussed below. There has been much debate over the years as to whether

the emphases and analytical preferences of IR make it a discipline, as distinct from a field

of study. The view taken in this chapter (which is not necessarily shared by other

chapters) is that IR is a field of study and not a distinct discipline. Indeed, one of its

strengths is its willingness to draw from different disciplines so that people who

specialize in the field have developed an analytical approach which is more than the sum

total of the application of individual disciplines. Even if this view is accepted, there are

competing views as to the strengths and weaknesses of the approach, and whether it has

responded adequately to the changing nature of work. Some of these issues are addressed

below.

Why is paid employment important? It is important to the employee most

obviously as a source of income. Note that it is not the case that work outside

employment is an easy alternative: at one time, it was argued by some that a combination

of unemployment, self-provisioning and work in the informal economy provided an

alternative to the formal economy, but research found that such work tends to be

additional rather than an alternative to formal employment. Work is also important to the

employee as a means of identity. ‘What do you do for a living?’ is a standard query to

locate a new acquaintance. And what goes on within the employment relationship is

crucial, not only in terms of the pay which is earned but also the conditions under which

it is earned: the degree of autonomy the employee is granted, the safety of the work

environment, the opportunity for training and development, and so on.

For the employer the work relationship is crucial in two different senses. First, it

is commonly argued that capital and technologies are increasingly readily available, so

that a firm’s competitive position depends on the skills and knowledge of its workers.

Some analytical grounding for this argument comes from the resource-based view of the

firm which developed from debates on strategic management. This view sees the firm as

a bundle of assets and argues that it is the configuration of these assets, rather than

positioning in relation to an external market, which is central to competitive advantage

(Wernerfeld 1984; see further Chapter 7). Not surprisingly, HRM and IR writers have

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

latched onto this idea, arguing that ‘distinctive human resources’ are the core resource

(Cappelli and Crocker-Hefter 1996). Second, and fundamentally, these ‘human resources’

are different from other resources because they cannot be separated from the people in

whom they exist. The employment relationship is about organizing human resources in

the light of the productive aims of the firm but also the aims of employees. It is

necessarily open-ended, uncertain, and, as argued below, a blend of inherently

contradictory principles concerning control and consent.

Finally, paid employment is important to society for what it expects in terms of

‘inputs’ and produces as ‘outputs’. Inputs include how much labour is demanded (with

obvious implications if demand is less than supply, resulting in unemployment) and what

types of labour are sought (influencing, for example, the kinds of skills which ‘society’

provides through the education system). If employment is structured on gender lines, this

will have major consequences for the domestic division of labour and the roles of men

and women in society; the traditional image of the male breadwinner applied not only to

paid employment but also had implications for the ability of women to engage in politics,

the arts, and sport. ‘Outputs’ include not only goods and services but also structures of

advantage and disadvantage. These are properly called structures because they are

established features of society which are hard to change, for example differences of pay

between occupations and between men and women.

Issues in the Regulation of Work

If work is important, how many people are in an employment relationship and how many

are not, and what has been happening to work relationships? The exercise in Box 1.1 may

thus be helpful.

latched onto this idea, arguing that ‘distinctive human resources’ are the core resource

(Cappelli and Crocker-Hefter 1996). Second, and fundamentally, these ‘human resources’

are different from other resources because they cannot be separated from the people in

whom they exist. The employment relationship is about organizing human resources in

the light of the productive aims of the firm but also the aims of employees. It is

necessarily open-ended, uncertain, and, as argued below, a blend of inherently

contradictory principles concerning control and consent.

Finally, paid employment is important to society for what it expects in terms of

‘inputs’ and produces as ‘outputs’. Inputs include how much labour is demanded (with

obvious implications if demand is less than supply, resulting in unemployment) and what

types of labour are sought (influencing, for example, the kinds of skills which ‘society’

provides through the education system). If employment is structured on gender lines, this

will have major consequences for the domestic division of labour and the roles of men

and women in society; the traditional image of the male breadwinner applied not only to

paid employment but also had implications for the ability of women to engage in politics,

the arts, and sport. ‘Outputs’ include not only goods and services but also structures of

advantage and disadvantage. These are properly called structures because they are

established features of society which are hard to change, for example differences of pay

between occupations and between men and women.

Issues in the Regulation of Work

If work is important, how many people are in an employment relationship and how many

are not, and what has been happening to work relationships? The exercise in Box 1.1 may

thus be helpful.

6

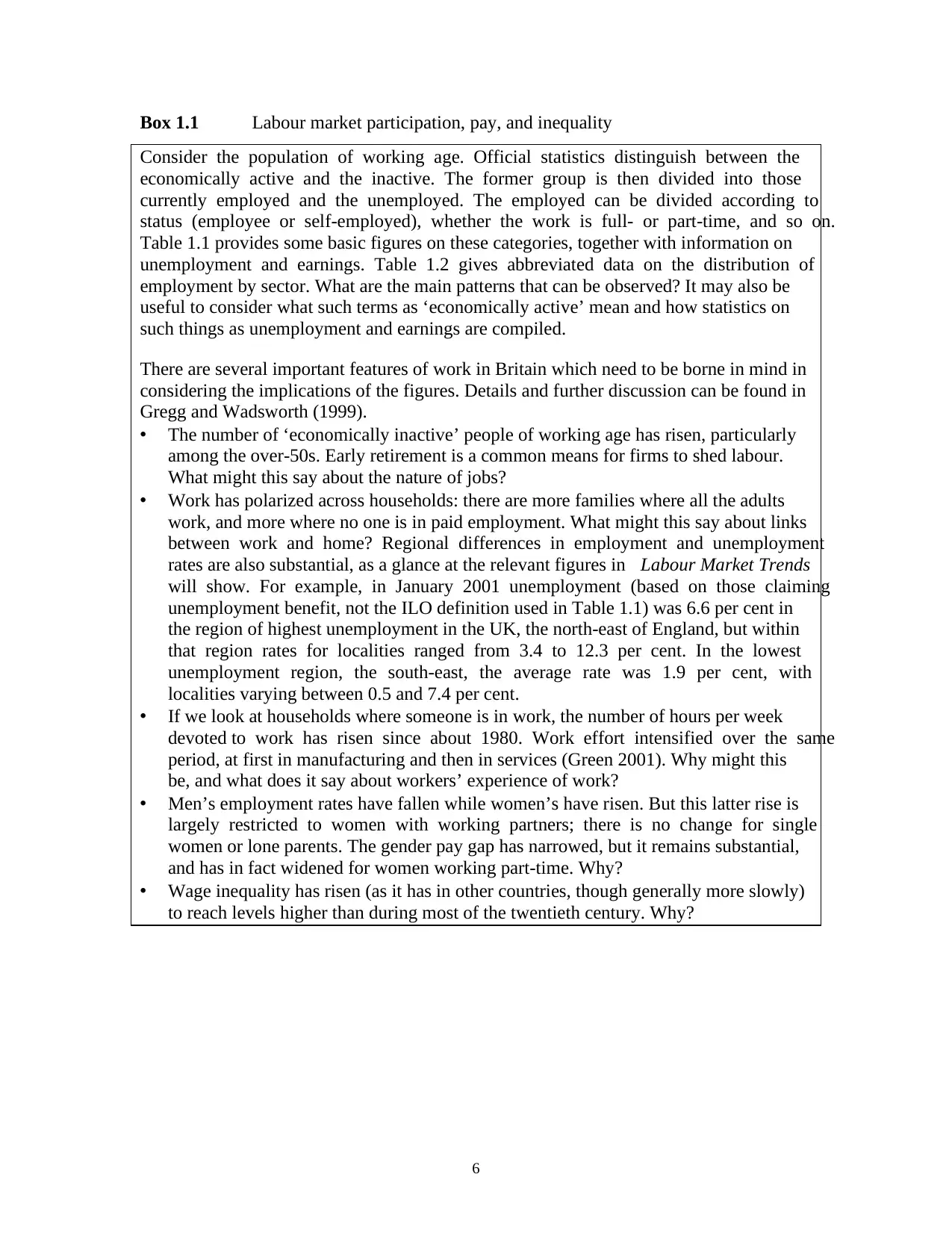

Box 1.1 Labour market participation, pay, and inequality

Consider the population of working age. Official statistics distinguish between the

economically active and the inactive. The former group is then divided into those

currently employed and the unemployed. The employed can be divided according to

status (employee or self-employed), whether the work is full- or part-time, and so on.

Table 1.1 provides some basic figures on these categories, together with information on

unemployment and earnings. Table 1.2 gives abbreviated data on the distribution of

employment by sector. What are the main patterns that can be observed? It may also be

useful to consider what such terms as ‘economically active’ mean and how statistics on

such things as unemployment and earnings are compiled.

There are several important features of work in Britain which need to be borne in mind in

considering the implications of the figures. Details and further discussion can be found in

Gregg and Wadsworth (1999).

• The number of ‘economically inactive’ people of working age has risen, particularly

among the over-50s. Early retirement is a common means for firms to shed labour.

What might this say about the nature of jobs?

• Work has polarized across households: there are more families where all the adults

work, and more where no one is in paid employment. What might this say about links

between work and home? Regional differences in employment and unemployment

rates are also substantial, as a glance at the relevant figures in Labour Market Trends

will show. For example, in January 2001 unemployment (based on those claiming

unemployment benefit, not the ILO definition used in Table 1.1) was 6.6 per cent in

the region of highest unemployment in the UK, the north-east of England, but within

that region rates for localities ranged from 3.4 to 12.3 per cent. In the lowest

unemployment region, the south-east, the average rate was 1.9 per cent, with

localities varying between 0.5 and 7.4 per cent.

• If we look at households where someone is in work, the number of hours per week

devoted to work has risen since about 1980. Work effort intensified over the same

period, at first in manufacturing and then in services (Green 2001). Why might this

be, and what does it say about workers’ experience of work?

• Men’s employment rates have fallen while women’s have risen. But this latter rise is

largely restricted to women with working partners; there is no change for single

women or lone parents. The gender pay gap has narrowed, but it remains substantial,

and has in fact widened for women working part-time. Why?

• Wage inequality has risen (as it has in other countries, though generally more slowly)

to reach levels higher than during most of the twentieth century. Why?

Box 1.1 Labour market participation, pay, and inequality

Consider the population of working age. Official statistics distinguish between the

economically active and the inactive. The former group is then divided into those

currently employed and the unemployed. The employed can be divided according to

status (employee or self-employed), whether the work is full- or part-time, and so on.

Table 1.1 provides some basic figures on these categories, together with information on

unemployment and earnings. Table 1.2 gives abbreviated data on the distribution of

employment by sector. What are the main patterns that can be observed? It may also be

useful to consider what such terms as ‘economically active’ mean and how statistics on

such things as unemployment and earnings are compiled.

There are several important features of work in Britain which need to be borne in mind in

considering the implications of the figures. Details and further discussion can be found in

Gregg and Wadsworth (1999).

• The number of ‘economically inactive’ people of working age has risen, particularly

among the over-50s. Early retirement is a common means for firms to shed labour.

What might this say about the nature of jobs?

• Work has polarized across households: there are more families where all the adults

work, and more where no one is in paid employment. What might this say about links

between work and home? Regional differences in employment and unemployment

rates are also substantial, as a glance at the relevant figures in Labour Market Trends

will show. For example, in January 2001 unemployment (based on those claiming

unemployment benefit, not the ILO definition used in Table 1.1) was 6.6 per cent in

the region of highest unemployment in the UK, the north-east of England, but within

that region rates for localities ranged from 3.4 to 12.3 per cent. In the lowest

unemployment region, the south-east, the average rate was 1.9 per cent, with

localities varying between 0.5 and 7.4 per cent.

• If we look at households where someone is in work, the number of hours per week

devoted to work has risen since about 1980. Work effort intensified over the same

period, at first in manufacturing and then in services (Green 2001). Why might this

be, and what does it say about workers’ experience of work?

• Men’s employment rates have fallen while women’s have risen. But this latter rise is

largely restricted to women with working partners; there is no change for single

women or lone parents. The gender pay gap has narrowed, but it remains substantial,

and has in fact widened for women working part-time. Why?

• Wage inequality has risen (as it has in other countries, though generally more slowly)

to reach levels higher than during most of the twentieth century. Why?

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

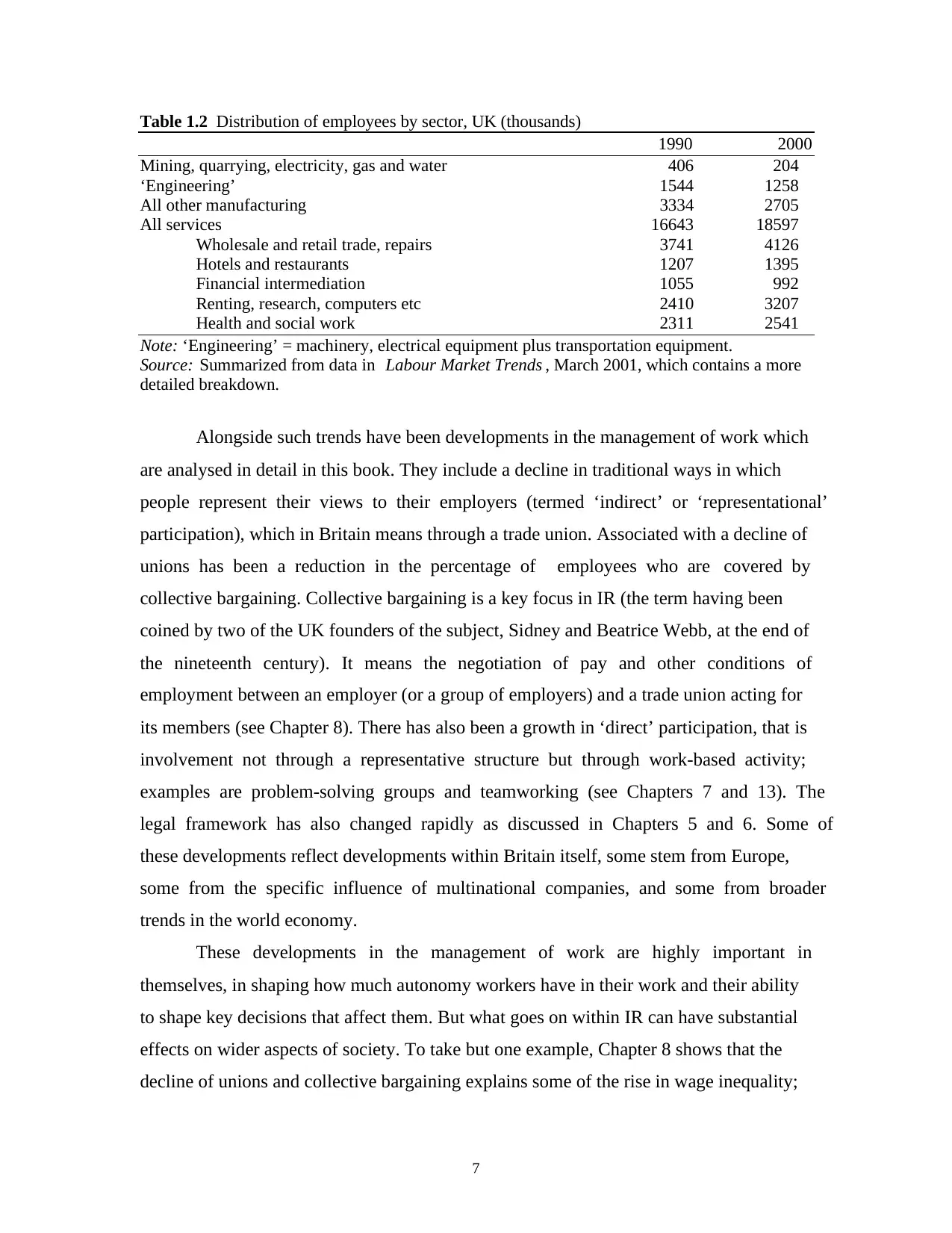

Table 1.2 Distribution of employees by sector, UK (thousands)

1990 2000

Mining, quarrying, electricity, gas and water 406 204

‘Engineering’ 1544 1258

All other manufacturing 3334 2705

All services 16643 18597

Wholesale and retail trade, repairs 3741 4126

Hotels and restaurants 1207 1395

Financial intermediation 1055 992

Renting, research, computers etc 2410 3207

Health and social work 2311 2541

Note: ‘Engineering’ = machinery, electrical equipment plus transportation equipment.

Source: Summarized from data in Labour Market Trends , March 2001, which contains a more

detailed breakdown.

Alongside such trends have been developments in the management of work which

are analysed in detail in this book. They include a decline in traditional ways in which

people represent their views to their employers (termed ‘indirect’ or ‘representational’

participation), which in Britain means through a trade union. Associated with a decline of

unions has been a reduction in the percentage of employees who are covered by

collective bargaining. Collective bargaining is a key focus in IR (the term having been

coined by two of the UK founders of the subject, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, at the end of

the nineteenth century). It means the negotiation of pay and other conditions of

employment between an employer (or a group of employers) and a trade union acting for

its members (see Chapter 8). There has also been a growth in ‘direct’ participation, that is

involvement not through a representative structure but through work-based activity;

examples are problem-solving groups and teamworking (see Chapters 7 and 13). The

legal framework has also changed rapidly as discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. Some of

these developments reflect developments within Britain itself, some stem from Europe,

some from the specific influence of multinational companies, and some from broader

trends in the world economy.

These developments in the management of work are highly important in

themselves, in shaping how much autonomy workers have in their work and their ability

to shape key decisions that affect them. But what goes on within IR can have substantial

effects on wider aspects of society. To take but one example, Chapter 8 shows that the

decline of unions and collective bargaining explains some of the rise in wage inequality;

Table 1.2 Distribution of employees by sector, UK (thousands)

1990 2000

Mining, quarrying, electricity, gas and water 406 204

‘Engineering’ 1544 1258

All other manufacturing 3334 2705

All services 16643 18597

Wholesale and retail trade, repairs 3741 4126

Hotels and restaurants 1207 1395

Financial intermediation 1055 992

Renting, research, computers etc 2410 3207

Health and social work 2311 2541

Note: ‘Engineering’ = machinery, electrical equipment plus transportation equipment.

Source: Summarized from data in Labour Market Trends , March 2001, which contains a more

detailed breakdown.

Alongside such trends have been developments in the management of work which

are analysed in detail in this book. They include a decline in traditional ways in which

people represent their views to their employers (termed ‘indirect’ or ‘representational’

participation), which in Britain means through a trade union. Associated with a decline of

unions has been a reduction in the percentage of employees who are covered by

collective bargaining. Collective bargaining is a key focus in IR (the term having been

coined by two of the UK founders of the subject, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, at the end of

the nineteenth century). It means the negotiation of pay and other conditions of

employment between an employer (or a group of employers) and a trade union acting for

its members (see Chapter 8). There has also been a growth in ‘direct’ participation, that is

involvement not through a representative structure but through work-based activity;

examples are problem-solving groups and teamworking (see Chapters 7 and 13). The

legal framework has also changed rapidly as discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. Some of

these developments reflect developments within Britain itself, some stem from Europe,

some from the specific influence of multinational companies, and some from broader

trends in the world economy.

These developments in the management of work are highly important in

themselves, in shaping how much autonomy workers have in their work and their ability

to shape key decisions that affect them. But what goes on within IR can have substantial

effects on wider aspects of society. To take but one example, Chapter 8 shows that the

decline of unions and collective bargaining explains some of the rise in wage inequality;

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

as mentioned below, moreover, it appears that international differences in IR structures

help to explain the size of the gender pay gap. It might be helpful to pause to consider

what mechanisms may explain such links between processes and outcomes, and which of

the other features in the bullet points in Box 1.1 could be the result of trends in the

handling of IR. IR thus has important implications for life beyond its own terrain.

What are the pressing current issues in employment? Three examples are given,

partly for their substantive importance, but also to signal the critical view of them which

is developing within IR.

The first concerns so-called ‘high commitment’ or ‘high involvement’ work

systems. These are discussed in detail in Chapter 13, but essentially embrace systems

such as teamworking and are often linked to new managerial techniques such as Business

Process Re-engineering. Some research in the UK and the US finds that these systems

‘work’ in that they produce improvements in efficiency and (though the evidence is much

more controversial here) can be associated with benefits for workers too (see Chapter 19).

Yet it is also found that they exist only rarely; perhaps 2 per cent of UK workplaces

conform to the high commitment model. This situation is often seen as a paradox.

There is some value in posing the matter this way, but there are now some

reasonably well-established resolutions of the paradox as posed. As will be seen in

Chapters 7 and 13 in particular, the benefits depend on certain conditions and they

operate at best only in the long-term whereas their costs are significant and immediate.

The structure of British firms tends to mean that the conditions are hard to secure and that

the short-term considerations outweigh the long-run ones. Moreover, what is meant by

‘working’ requires more exploration: working in what ways and for whom? Other modes

of organizing work, notably those based on low skills and low wages, can equally work

for employers in producing acceptable profits; and, some commentators would argue,

they are well-suited to the British context (see Chapter 15). And high commitment

systems will have their own tensions: they are a way of managing the contradictions of

control and consent, not escaping from them.

A second pressing issue is the international context. Some writers deploy concepts

such as globalization to capture new international competitive pressures. They are better

seen as convenient labels rather than developed concepts, for issues immediately arise as

as mentioned below, moreover, it appears that international differences in IR structures

help to explain the size of the gender pay gap. It might be helpful to pause to consider

what mechanisms may explain such links between processes and outcomes, and which of

the other features in the bullet points in Box 1.1 could be the result of trends in the

handling of IR. IR thus has important implications for life beyond its own terrain.

What are the pressing current issues in employment? Three examples are given,

partly for their substantive importance, but also to signal the critical view of them which

is developing within IR.

The first concerns so-called ‘high commitment’ or ‘high involvement’ work

systems. These are discussed in detail in Chapter 13, but essentially embrace systems

such as teamworking and are often linked to new managerial techniques such as Business

Process Re-engineering. Some research in the UK and the US finds that these systems

‘work’ in that they produce improvements in efficiency and (though the evidence is much

more controversial here) can be associated with benefits for workers too (see Chapter 19).

Yet it is also found that they exist only rarely; perhaps 2 per cent of UK workplaces

conform to the high commitment model. This situation is often seen as a paradox.

There is some value in posing the matter this way, but there are now some

reasonably well-established resolutions of the paradox as posed. As will be seen in

Chapters 7 and 13 in particular, the benefits depend on certain conditions and they

operate at best only in the long-term whereas their costs are significant and immediate.

The structure of British firms tends to mean that the conditions are hard to secure and that

the short-term considerations outweigh the long-run ones. Moreover, what is meant by

‘working’ requires more exploration: working in what ways and for whom? Other modes

of organizing work, notably those based on low skills and low wages, can equally work

for employers in producing acceptable profits; and, some commentators would argue,

they are well-suited to the British context (see Chapter 15). And high commitment

systems will have their own tensions: they are a way of managing the contradictions of

control and consent, not escaping from them.

A second pressing issue is the international context. Some writers deploy concepts

such as globalization to capture new international competitive pressures. They are better

seen as convenient labels rather than developed concepts, for issues immediately arise as

9

to the novelty of the developments identified and what identifiable social forces are

actually causing them. In the field of work, three inter-related forces are international

competition, the role of multinational companies (MNCs), and European integration.

Under the first, the British economy has become increasingly open, as indicated by a

growth in imports and exports as a proportion of GDP and the use of explicit wage and

cost comparisons by companies in the making of investment decisions (see Chapters 3

and 7). A well-known UK example is the decision in early 2000 of the German firm

BMW to sell the Rover car company, which it had acquired in 1994, blaming the value of

the pound in relation to the euro and the difficulty of re-structuring the Rover operations

to attain satisfactory productivity levels. That the UK is not alone is illustrated by the

case of Renault in Belgium, which in February 1997 announced without warning the

closure of its Vilvoorde plant with the loss of 3000 jobs.

This example also points to one role of the MNC. But, as discussed in Chapter 4,

there are other roles notably the importing of forms of work organization, and it is often

US MNCs which are in the lead here. Finally, European integration has effects through

the impact of European labour law on Britain and through the wider processes of

economic and monetary union (EMU). Under the first, European directives have had

clear effects on matters as varied as the regulation of working time, consultation over

redundancies and European Works Councils (requiring that certain large MNCs establish

such councils for the purposes of information and consultation about their European

operations). Under the second, unit wage costs are increasingly subject to comparison

across Europe, while the implications spread outside the traded goods sector. Thus

government finances are shaped by pressures on interest rates and the public sector

borrowing requirement, which in turn has implications for the control of costs, including

pay, in the public sector.

One aspect of internationalization which has recently come to the fore is whether

British industrial relations are being Europeanized or Americanized.

• Europeanization means either or both of: the influence of European-level

developments in Britain (either directly, for example the application of directives, or

indirectly, for example where monetary union brings pressure for convergence in IR

practice); and the development of a common model across Europe. Such a model

to the novelty of the developments identified and what identifiable social forces are

actually causing them. In the field of work, three inter-related forces are international

competition, the role of multinational companies (MNCs), and European integration.

Under the first, the British economy has become increasingly open, as indicated by a

growth in imports and exports as a proportion of GDP and the use of explicit wage and

cost comparisons by companies in the making of investment decisions (see Chapters 3

and 7). A well-known UK example is the decision in early 2000 of the German firm

BMW to sell the Rover car company, which it had acquired in 1994, blaming the value of

the pound in relation to the euro and the difficulty of re-structuring the Rover operations

to attain satisfactory productivity levels. That the UK is not alone is illustrated by the

case of Renault in Belgium, which in February 1997 announced without warning the

closure of its Vilvoorde plant with the loss of 3000 jobs.

This example also points to one role of the MNC. But, as discussed in Chapter 4,

there are other roles notably the importing of forms of work organization, and it is often

US MNCs which are in the lead here. Finally, European integration has effects through

the impact of European labour law on Britain and through the wider processes of

economic and monetary union (EMU). Under the first, European directives have had

clear effects on matters as varied as the regulation of working time, consultation over

redundancies and European Works Councils (requiring that certain large MNCs establish

such councils for the purposes of information and consultation about their European

operations). Under the second, unit wage costs are increasingly subject to comparison

across Europe, while the implications spread outside the traded goods sector. Thus

government finances are shaped by pressures on interest rates and the public sector

borrowing requirement, which in turn has implications for the control of costs, including

pay, in the public sector.

One aspect of internationalization which has recently come to the fore is whether

British industrial relations are being Europeanized or Americanized.

• Europeanization means either or both of: the influence of European-level

developments in Britain (either directly, for example the application of directives, or

indirectly, for example where monetary union brings pressure for convergence in IR

practice); and the development of a common model across Europe. Such a model

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

often embraces ideas of ‘social partnership’. As discussed in Chapter 7, 9 and 10,

these ideas are often imprecise and contested, but at their core is the notion of a

common agenda between representatives of capital and labour.

• Americanization embraces the continuing decline of unions and the assertion of a

market-driven model.

The former process is perhaps the more obvious in the light of European integration and

the promulgation of a European social model claiming to combine flexibility with

security and to promote employee participation without threatening efficiency (see Bach

and Sisson 2000: 35). As Bach and Sisson stress, however, such a model is a prescription

for what might be rather than an account of what exists, and several aspects of it are

under challenge from international cost pressures. At the same time, the rapid growth of

the American economy during the 1990s and the European interest in its ability to

generate jobs indicate that the American model of weak trade unions and extensive

flexibility is equally influential. It is not of course the case that these models are tightly

integrated packages or that one can simply choose between them. Different features can

be combined in different ways.

A third set of issues concerns ‘outcomes’ of a pattern of IR. The most discussed

outcome, touched on above, is economic performance. Chapter 19 discusses the linkages

between IR arrangements and performance. But other outcomes include the level and

pattern of pay. As indicated above, one of the outstanding features of the British economy

has been the rise in income inequality since 1980. A closely connected form of outcome

is the pattern of gender inequality, as indexed by pay differentials and the degree to

which women gain access to the most desirable occupations (see Chapter 16). It has been

shown across many advanced industrialized countries that various measures of equality

and well-being, including the size of the pay gap between men and women and the degree

of pay inequality between the top and bottom of the income distribution, are affected by

the extent of collective bargaining (e.g. Whitehouse and Zetlin 1999). Given that

collective bargaining has been in long-term decline in the UK, key issues are whether this

decline is likely to be reversed and if not what other arrangements might be put in place

and what implications they have for economic welfare.

often embraces ideas of ‘social partnership’. As discussed in Chapter 7, 9 and 10,

these ideas are often imprecise and contested, but at their core is the notion of a

common agenda between representatives of capital and labour.

• Americanization embraces the continuing decline of unions and the assertion of a

market-driven model.

The former process is perhaps the more obvious in the light of European integration and

the promulgation of a European social model claiming to combine flexibility with

security and to promote employee participation without threatening efficiency (see Bach

and Sisson 2000: 35). As Bach and Sisson stress, however, such a model is a prescription

for what might be rather than an account of what exists, and several aspects of it are

under challenge from international cost pressures. At the same time, the rapid growth of

the American economy during the 1990s and the European interest in its ability to

generate jobs indicate that the American model of weak trade unions and extensive

flexibility is equally influential. It is not of course the case that these models are tightly

integrated packages or that one can simply choose between them. Different features can

be combined in different ways.

A third set of issues concerns ‘outcomes’ of a pattern of IR. The most discussed

outcome, touched on above, is economic performance. Chapter 19 discusses the linkages

between IR arrangements and performance. But other outcomes include the level and

pattern of pay. As indicated above, one of the outstanding features of the British economy

has been the rise in income inequality since 1980. A closely connected form of outcome

is the pattern of gender inequality, as indexed by pay differentials and the degree to

which women gain access to the most desirable occupations (see Chapter 16). It has been

shown across many advanced industrialized countries that various measures of equality

and well-being, including the size of the pay gap between men and women and the degree

of pay inequality between the top and bottom of the income distribution, are affected by

the extent of collective bargaining (e.g. Whitehouse and Zetlin 1999). Given that

collective bargaining has been in long-term decline in the UK, key issues are whether this

decline is likely to be reversed and if not what other arrangements might be put in place

and what implications they have for economic welfare.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

Analysing the Employment Relationship

Components of industrial relations

What has IR to say about how we might analyse such issues? The employment

relationship has two parts, market relations and managerial relations (Flanders 1974). The

former is the more obvious. It covers the price of labour, which embraces not only the

basic wage but also hours of work, holidays and pension rights. In this respect, labour is

like any other commodity with a price which represents the total cost of enjoying its use.

Yet labour differs from all other commodities in that it is enjoyed in use and is embodied

in people. A machine in a factory is also enjoyed in use and for what it can produce. Yet

how it is used is solely in up to its owner. The ‘owner’ of labour, the employer, has to

persuade the worker, that is the person in whom the labour is embodied, to work.

Managerial relations are the relationships that define how this process takes place: market

relations set a price for a set number of hours of work, and managerial relations

determine how much work is performed in that time, at what specific task or tasks, who

has the right to define the tasks and change a particular mix of tasks and what penalties

will be deployed for any failure to meet these obligations. A standard text thus defines IR

as the ‘study of the rules governing employment’ (Clegg 1979: 1). The importance of this

definition is developed below.

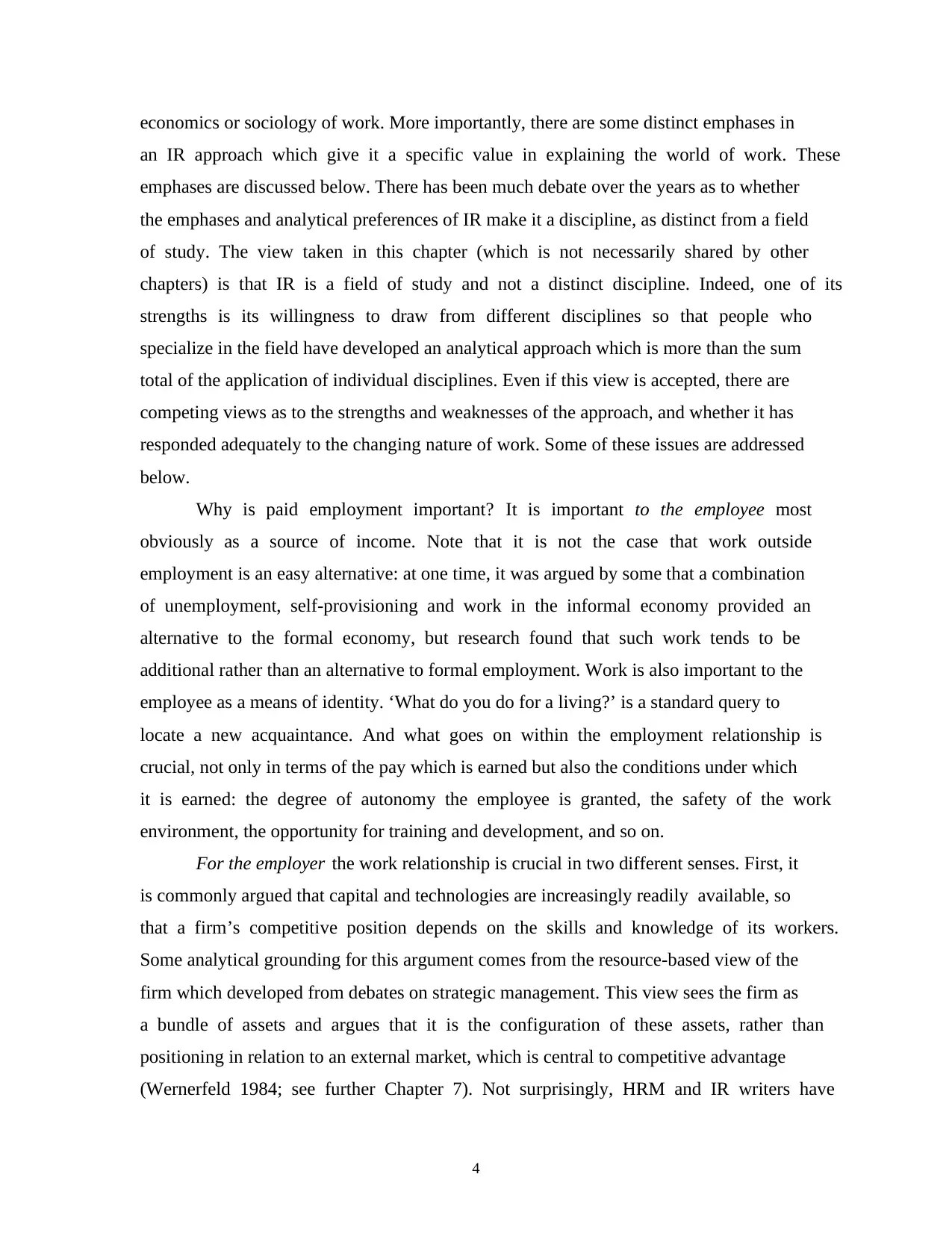

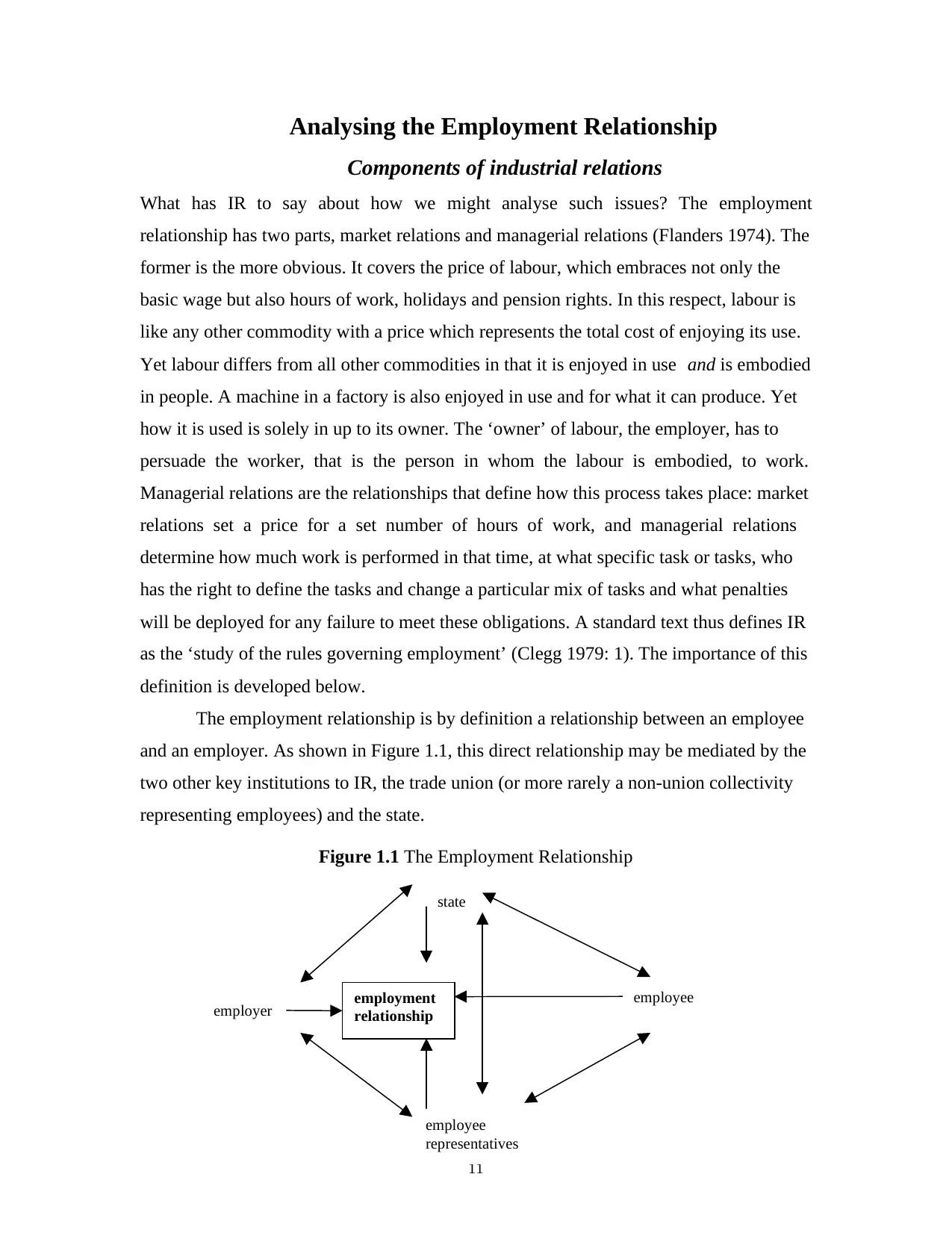

The employment relationship is by definition a relationship between an employee

and an employer. As shown in Figure 1.1, this direct relationship may be mediated by the

two other key institutions to IR, the trade union (or more rarely a non-union collectivity

representing employees) and the state.

Figure 1.1 The Employment Relationship

employment

relationshipemployer employee

state

employee

representatives

Analysing the Employment Relationship

Components of industrial relations

What has IR to say about how we might analyse such issues? The employment

relationship has two parts, market relations and managerial relations (Flanders 1974). The

former is the more obvious. It covers the price of labour, which embraces not only the

basic wage but also hours of work, holidays and pension rights. In this respect, labour is

like any other commodity with a price which represents the total cost of enjoying its use.

Yet labour differs from all other commodities in that it is enjoyed in use and is embodied

in people. A machine in a factory is also enjoyed in use and for what it can produce. Yet

how it is used is solely in up to its owner. The ‘owner’ of labour, the employer, has to

persuade the worker, that is the person in whom the labour is embodied, to work.

Managerial relations are the relationships that define how this process takes place: market

relations set a price for a set number of hours of work, and managerial relations

determine how much work is performed in that time, at what specific task or tasks, who

has the right to define the tasks and change a particular mix of tasks and what penalties

will be deployed for any failure to meet these obligations. A standard text thus defines IR

as the ‘study of the rules governing employment’ (Clegg 1979: 1). The importance of this

definition is developed below.

The employment relationship is by definition a relationship between an employee

and an employer. As shown in Figure 1.1, this direct relationship may be mediated by the

two other key institutions to IR, the trade union (or more rarely a non-union collectivity

representing employees) and the state.

Figure 1.1 The Employment Relationship

employment

relationshipemployer employee

state

employee

representatives

12

A trade union in its most basic role represents a group of workers in a specified

part of their relations with a single employer. A union’s role can be measured in terms of

density, mobilization, extent and scope.

• Density is the proportion of an identified constituency who are members of a union.

• The extent of a union’s activity refers to the range of the constituency: a union can

represent a small group of employees in one locality, or all the employees in an

occupation, or all the employees of a given employer, or extend beyond an

occupation or an employer.

• Mobilization – the degree to which unions identify common interests among their

members, persuade the members as to what the interests are, and organize in pursuit

of the interests -- is important because, most obviously in countries such as France, a

union may be capable of mobilizing more employees than its nominal members. By

the same token, members will not necessarily follow a union’s policy. Unions face

issues of how far they represent members and of aggregating membership interests

into a common policy.

• Scope is the degree to which the various aspects of the employment relationship are

within the purview of the union: it may bargain only over wages and hours, or cover

also working conditions, or extend further to issues including training, the

classification of jobs and the system of workplace discipline.

Unions engage with employees through efforts to organize them and through

mobilization around sets of demands. They engage with employers by taking part in

collective bargaining. They may also engage with the state, for example in making

demands for legislation or in engaging in more lasting forms of accommodation (such as

‘corporatism’ in the Nordic countries or a series of ‘Accords’ in Australia).

The state influences the employment relationship directly through laws on wages

(e.g. minimum wages), working conditions (e.g. on hours of work) and many other issues

and through its role as the employer of public sector workers (see Chapter 11). It also has

a series of indirect influences. It has relationships with unions, either through laws on

union government or through bilateral arrangements (e.g. the UK ‘social contract’ of the

1970s in which unions promised to moderate wage demands in return for tax

concessions) or through trilateral relationships also involving employers (corporatism). In

A trade union in its most basic role represents a group of workers in a specified

part of their relations with a single employer. A union’s role can be measured in terms of

density, mobilization, extent and scope.

• Density is the proportion of an identified constituency who are members of a union.

• The extent of a union’s activity refers to the range of the constituency: a union can

represent a small group of employees in one locality, or all the employees in an

occupation, or all the employees of a given employer, or extend beyond an

occupation or an employer.

• Mobilization – the degree to which unions identify common interests among their

members, persuade the members as to what the interests are, and organize in pursuit

of the interests -- is important because, most obviously in countries such as France, a

union may be capable of mobilizing more employees than its nominal members. By

the same token, members will not necessarily follow a union’s policy. Unions face

issues of how far they represent members and of aggregating membership interests

into a common policy.

• Scope is the degree to which the various aspects of the employment relationship are

within the purview of the union: it may bargain only over wages and hours, or cover

also working conditions, or extend further to issues including training, the

classification of jobs and the system of workplace discipline.

Unions engage with employees through efforts to organize them and through

mobilization around sets of demands. They engage with employers by taking part in

collective bargaining. They may also engage with the state, for example in making

demands for legislation or in engaging in more lasting forms of accommodation (such as

‘corporatism’ in the Nordic countries or a series of ‘Accords’ in Australia).

The state influences the employment relationship directly through laws on wages

(e.g. minimum wages), working conditions (e.g. on hours of work) and many other issues

and through its role as the employer of public sector workers (see Chapter 11). It also has

a series of indirect influences. It has relationships with unions, either through laws on

union government or through bilateral arrangements (e.g. the UK ‘social contract’ of the

1970s in which unions promised to moderate wage demands in return for tax

concessions) or through trilateral relationships also involving employers (corporatism). In

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 48

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.