EAEC: Virulence Factors and Clinical Manifestations of Infection

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/17

|32

|17557

|18

Report

AI Summary

This document provides a comprehensive overview of Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC), a significant food-borne pathogen responsible for causing acute and persistent diarrhea, particularly in children and immunocompromised individuals. The report delves into the definition of EAEC, characterized by its aggregative adherence pattern on epithelial cells, and its emergence as a global health concern, especially in developing countries. It explores the general concepts, including the evolution of the term 'aggregative adherence' and the classification of EAEC strains. The document also examines the general epidemiology of EAEC, highlighting its association with both acute and persistent diarrhea, traveler's diarrhea, and outbreaks worldwide, including those linked to contaminated food. Clinical features, such as watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever, are discussed, along with the heterogeneity of symptoms and the role of virulence factors. Furthermore, the document explores histopathological studies, illustrating EAEC's interactions with intestinal cells and its impact on the intestinal mucosa. The heterogeneity of EAEC strains, in terms of serotypes, genetic determinants, and virulence factors, is also addressed, emphasizing the ongoing research to understand the pathogenesis of this complex pathogen.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309172847

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

Chapter · October 2016

DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-45092-6_2

CITATIONS

6

READS

977

2 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Inflammation induced by the different diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypesView project

Effect of Bacterial proteases on biological substratesView project

Fernando Navarro-Garcia

Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute

105PUBLICATIONS3,924CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

Chapter · October 2016

DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-45092-6_2

CITATIONS

6

READS

977

2 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Inflammation induced by the different diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypesView project

Effect of Bacterial proteases on biological substratesView project

Fernando Navarro-Garcia

Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute

105PUBLICATIONS3,924CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

27© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016

A.G. Torres (ed.), Escherichia coli in the Americas,

DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45092-6_2

Chapter 2

EnteroaggregativeEscherichia coli (EAEC)

Waldir P. Elias and Fernando Navarro-Garcia

Summary EnteroaggregativeEscherichia coli (EAEC) is defi ned by the production

of the characteristic aggregative adherence pattern on cultured epithelial cel

pathotype is a food-borne emerging enteropathogen , responsible for case

and persistent diarrhea in children and immunocompromised patients in deve

countries, as well as in travelers returning from endemic areas. Growth and c

impairment are linked to EAEC infections in children living in developing coun

The pathogenesis of EAEC is characterized by abundant adherence to the in

mucosa,elaborationof enterotoxins/cytotoxins,and inductionof mucosal

infl ammation. Several putative virulence factors associated with these three

have been identifi ed and characterized, but none of them is present in all str

The virulence gene(s) that defi ne virulent strains within this complex heter

is yet to be determined. An increasing attention to this pathotype emerged si

massive outbreak caused by a hybrid hypervirulent Shiga toxin-expressing EA

strain with severe clinical consequences.

W. P.Elias

Laboratório de Bacteriologia, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, Brazil

e-mail: waldir.elias@butantan.gov.br

F.Navarro-Garcia(* )

Department of Cell Biology, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN

(CINVESTAV-IPN), México, Distrito Federal, Mexico

e-mail: fnavarro@cell.cinvestav.mx

A.G. Torres (ed.), Escherichia coli in the Americas,

DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-45092-6_2

Chapter 2

EnteroaggregativeEscherichia coli (EAEC)

Waldir P. Elias and Fernando Navarro-Garcia

Summary EnteroaggregativeEscherichia coli (EAEC) is defi ned by the production

of the characteristic aggregative adherence pattern on cultured epithelial cel

pathotype is a food-borne emerging enteropathogen , responsible for case

and persistent diarrhea in children and immunocompromised patients in deve

countries, as well as in travelers returning from endemic areas. Growth and c

impairment are linked to EAEC infections in children living in developing coun

The pathogenesis of EAEC is characterized by abundant adherence to the in

mucosa,elaborationof enterotoxins/cytotoxins,and inductionof mucosal

infl ammation. Several putative virulence factors associated with these three

have been identifi ed and characterized, but none of them is present in all str

The virulence gene(s) that defi ne virulent strains within this complex heter

is yet to be determined. An increasing attention to this pathotype emerged si

massive outbreak caused by a hybrid hypervirulent Shiga toxin-expressing EA

strain with severe clinical consequences.

W. P.Elias

Laboratório de Bacteriologia, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, Brazil

e-mail: waldir.elias@butantan.gov.br

F.Navarro-Garcia(* )

Department of Cell Biology, Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN

(CINVESTAV-IPN), México, Distrito Federal, Mexico

e-mail: fnavarro@cell.cinvestav.mx

28

1 General Concepts

1.1 Defi ning EAEC

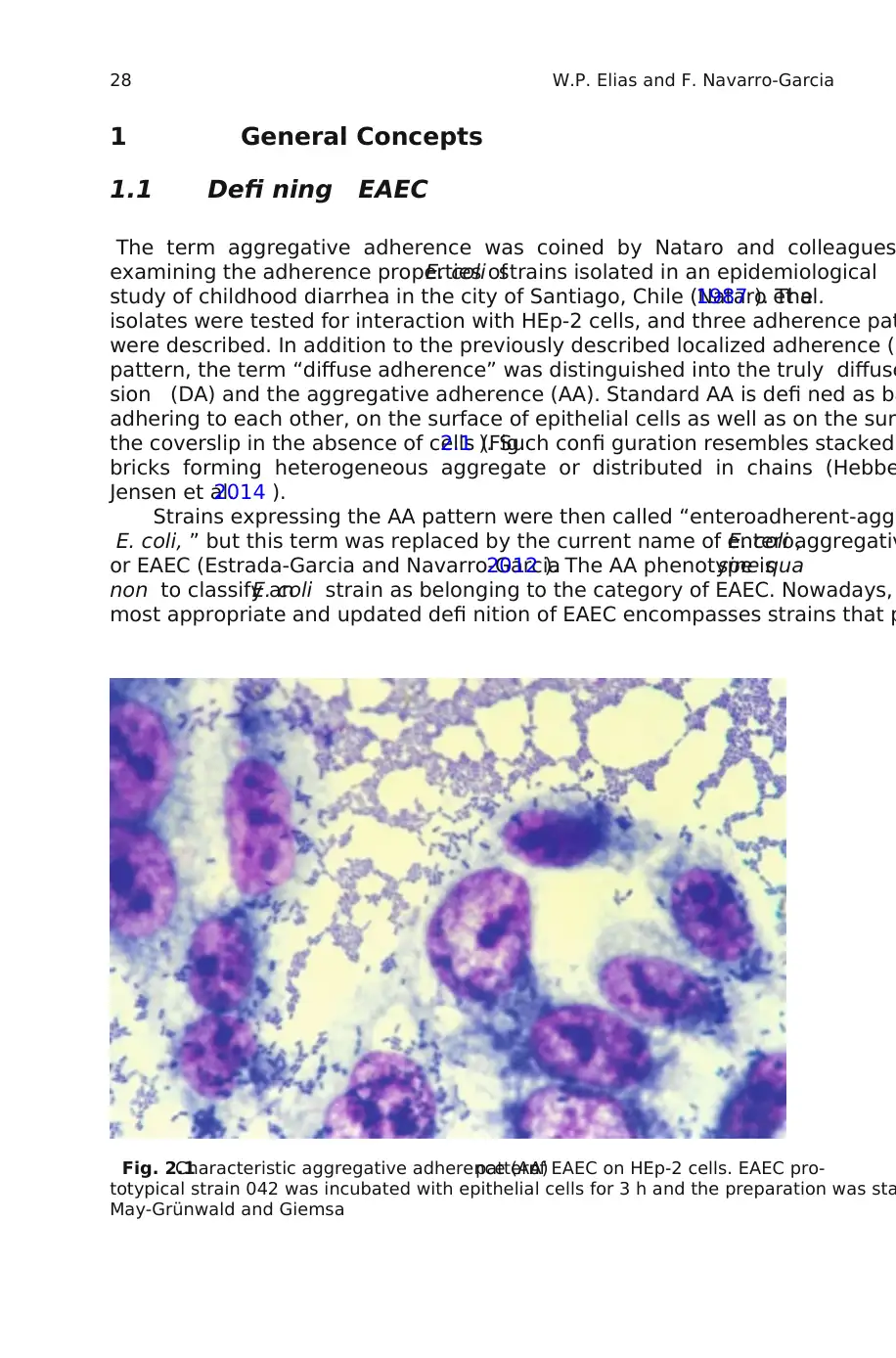

The term aggregative adherence was coined by Nataro and colleagues

examining the adherence properties ofE. coli strains isolated in an epidemiological

study of childhood diarrhea in the city of Santiago, Chile (Nataro et al.1987 ). The

isolates were tested for interaction with HEp-2 cells, and three adherence pat

were described. In addition to the previously described localized adherence (L

pattern, the term “diffuse adherence” was distinguished into the truly diffuse

sion (DA) and the aggregative adherence (AA). Standard AA is defi ned as ba

adhering to each other, on the surface of epithelial cells as well as on the sur

the coverslip in the absence of cells (Fig.2.1 ). Such confi guration resembles stacked

bricks forming heterogeneous aggregate or distributed in chains (Hebbe

Jensen et al.2014 ).

Strains expressing the AA pattern were then called “enteroadherent-aggr

E. coli, ” but this term was replaced by the current name of enteroaggregativE. coli ,

or EAEC (Estrada-Garcia and Navarro-Garcia2012 ). The AA phenotype issine qua

non to classify anE. coli strain as belonging to the category of EAEC. Nowadays,

most appropriate and updated defi nition of EAEC encompasses strains that p

Fig. 2.1Characteristic aggregative adherence (AA)patternof EAEC on HEp-2 cells. EAEC pro-

totypical strain 042 was incubated with epithelial cells for 3 h and the preparation was sta

May-Grünwald and Giemsa

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

1 General Concepts

1.1 Defi ning EAEC

The term aggregative adherence was coined by Nataro and colleagues

examining the adherence properties ofE. coli strains isolated in an epidemiological

study of childhood diarrhea in the city of Santiago, Chile (Nataro et al.1987 ). The

isolates were tested for interaction with HEp-2 cells, and three adherence pat

were described. In addition to the previously described localized adherence (L

pattern, the term “diffuse adherence” was distinguished into the truly diffuse

sion (DA) and the aggregative adherence (AA). Standard AA is defi ned as ba

adhering to each other, on the surface of epithelial cells as well as on the sur

the coverslip in the absence of cells (Fig.2.1 ). Such confi guration resembles stacked

bricks forming heterogeneous aggregate or distributed in chains (Hebbe

Jensen et al.2014 ).

Strains expressing the AA pattern were then called “enteroadherent-aggr

E. coli, ” but this term was replaced by the current name of enteroaggregativE. coli ,

or EAEC (Estrada-Garcia and Navarro-Garcia2012 ). The AA phenotype issine qua

non to classify anE. coli strain as belonging to the category of EAEC. Nowadays,

most appropriate and updated defi nition of EAEC encompasses strains that p

Fig. 2.1Characteristic aggregative adherence (AA)patternof EAEC on HEp-2 cells. EAEC pro-

totypical strain 042 was incubated with epithelial cells for 3 h and the preparation was sta

May-Grünwald and Giemsa

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

29

the AA pattern on HeLa or HEp-2 cells (3 or 6 h adhesion assay) and are devo

virulence markers that defi ne other types of diarrheagenicE. coli. An exception is for

strains presenting the AA pattern and other EAEC-specifi c genetic markers in

bination with the production of Shiga toxin (Stx) , which defi nes the hybrid

and Shiga toxin-producingE. coli (STEC), discussed below.

Currently, EAEC is considered an emerging enteropathogen, responsib

cases of acute and persistent diarrhea in children and adults worldwide, and

opmental consequences in children living in developing countries (Hebb

Jensen et al.2014 ). An increasing attention to this pathotype has arisen from t

massive outbreak caused by ahybrid hypervirulent EAEC strain (Stx2-expressing

EAEC) with severe sequelae such as the development of hemolytic uremic sy

drome (Navarro-Garcia2014 ).

1.2 General Epidemiology

Since its description in 1987, when EAEC was signifi cantly associated with a

diarrhea in children (Nataro et al.1987 ), numerous epidemiological studies of the

etiology of diarrhea searched for EAEC in an attempt to clarify its role as diarr

agent. In the early years, the association between EAEC and persistent

(≥14 days of duration) in children was well supported (Cravioto et al.1991 ).

However, the association with acute diarrhea in childhood was controversial.

In the following years, a large number of studies have reported the detect

EAEC in cases of acute diarrhea in developing and developed countries, persi

diarrhea in developing countries, and signifi cant outbreaks worldwide. In fac

and colleagues demonstrated by a meta-analysis study of the literature betw

and 2006 that EAEC was statistically associated with acute and persistent dia

developed and developing countries, to diarrhea in HIV-infected patients in d

ing countries, and adults traveler’s diarrhea (Huang et al.2006 ). Another recent

meta-analysis study of published articles between 1989 and 2011 showed as

of EAEC with acute diarrhea in children of South Asian populations (Pabalan e

2013 ). Thus, EAEC has been systematically identifi ed as an emerging enter

gen, globally distributed (Estrada-Garcia and Navarro-Garcia2012 ).

A high rate of asymptomatic young children carrying EAEC is still a

reported in several studies in the last years (Hebbelstrup Jensen et al.2014 ).

Moreover, such persistent colonization has a link with growth impairment in

dren from low socioeconomic status.

The linkage between EAEC and diarrhea in individuals living in developed c

tries became clearer in the last years. In the USA and Europe, EAEC has been

quently isolated from cases of diarrhea from children and adults. In prospecti

EAEC was the major cause of diarrhea in children in the USA (Nataro et al.2006 ).

Traveler’s diarrhea (TD) is the most frequent disease that affects individ

ing in developed countries when visiting middle and low incoming endemic a

EAEC has been systematically found among the most prevalent bacterial age

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

the AA pattern on HeLa or HEp-2 cells (3 or 6 h adhesion assay) and are devo

virulence markers that defi ne other types of diarrheagenicE. coli. An exception is for

strains presenting the AA pattern and other EAEC-specifi c genetic markers in

bination with the production of Shiga toxin (Stx) , which defi nes the hybrid

and Shiga toxin-producingE. coli (STEC), discussed below.

Currently, EAEC is considered an emerging enteropathogen, responsib

cases of acute and persistent diarrhea in children and adults worldwide, and

opmental consequences in children living in developing countries (Hebb

Jensen et al.2014 ). An increasing attention to this pathotype has arisen from t

massive outbreak caused by ahybrid hypervirulent EAEC strain (Stx2-expressing

EAEC) with severe sequelae such as the development of hemolytic uremic sy

drome (Navarro-Garcia2014 ).

1.2 General Epidemiology

Since its description in 1987, when EAEC was signifi cantly associated with a

diarrhea in children (Nataro et al.1987 ), numerous epidemiological studies of the

etiology of diarrhea searched for EAEC in an attempt to clarify its role as diarr

agent. In the early years, the association between EAEC and persistent

(≥14 days of duration) in children was well supported (Cravioto et al.1991 ).

However, the association with acute diarrhea in childhood was controversial.

In the following years, a large number of studies have reported the detect

EAEC in cases of acute diarrhea in developing and developed countries, persi

diarrhea in developing countries, and signifi cant outbreaks worldwide. In fac

and colleagues demonstrated by a meta-analysis study of the literature betw

and 2006 that EAEC was statistically associated with acute and persistent dia

developed and developing countries, to diarrhea in HIV-infected patients in d

ing countries, and adults traveler’s diarrhea (Huang et al.2006 ). Another recent

meta-analysis study of published articles between 1989 and 2011 showed as

of EAEC with acute diarrhea in children of South Asian populations (Pabalan e

2013 ). Thus, EAEC has been systematically identifi ed as an emerging enter

gen, globally distributed (Estrada-Garcia and Navarro-Garcia2012 ).

A high rate of asymptomatic young children carrying EAEC is still a

reported in several studies in the last years (Hebbelstrup Jensen et al.2014 ).

Moreover, such persistent colonization has a link with growth impairment in

dren from low socioeconomic status.

The linkage between EAEC and diarrhea in individuals living in developed c

tries became clearer in the last years. In the USA and Europe, EAEC has been

quently isolated from cases of diarrhea from children and adults. In prospecti

EAEC was the major cause of diarrhea in children in the USA (Nataro et al.2006 ).

Traveler’s diarrhea (TD) is the most frequent disease that affects individ

ing in developed countries when visiting middle and low incoming endemic a

EAEC has been systematically found among the most prevalent bacterial age

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

30

traveler’s diarrhea since the defi nition of this category. The prevalence of EA

TD varies from 19 to 33 %, depending on the geographic region visited (Moha

et al.2011 ).

Studies linked EAEC with diarrhea in HIV-infected adults and children, a gr

usually susceptible to signifi cant cases of protracted diarrhea. EAEC was isol

the only enteropathogen in symptomatic patients presenting diarrhea for 30

(Polotsky et al.1997 ). In addition, isolation of EAEC was similar in a case/contro

study of HIV patients (Medina et al.2010 ).

Several outbreaks of gastroenteritis caused by EAEC have been reported i

and high-income countries. Some of them involving very impressive numbers

infected children or adults and associated with the consumption of contamina

food. Outbreaks in the UK (Dallman et al.2014 ), Japan (Itoh et al. 1997 ), and Italy

(Scavia et al.2008 ) show the relevance of EAEC in developed countries. In one

the Japanese outbreaks, 2697 schoolchildren were affected after consum

school lunches (Itoh et al.1997). In Italy, the outbreaks were transmitted by unpas-

teurized cheese. EAEC was also responsible for outbreaks in developing coun

(Cobeljic et al.1996 ).

1.3 Clinical Features

The most common symptoms reported in EAEC infection are watery diarrhea

mucoid, with or without blood and abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and low

These signs and symptoms are often self-limited but some selected patients

develop persistent diarrhea (≥14 days). The diversity of clinical symptoms in

pathotype infection may be due to heterogeneity between EAEC isolates, infe

dose, genetic susceptibility factors in the host, as well as the immune

(Harrington et al.2006 ).

In order to better characterize the virulent properties of EAEC, studi

human volunteers receiving oral inoculum of different EAEC strains were

formed (Mathewson et al.1986 ; Nataro et al.1992 , 1995 ).

Nataro and colleagues evaluated four different EAEC isolated from diff

geographic regions and different serotypes in volunteers (Nataro et al.1995 ). In this

study, the volunteers ingested dose of 1010 CFU and just EAEC O42 (serotype

O44:H18) caused diarrhea in three out of fi ve volunteers. EAEC 042 was isola

from a case of childhood diarrhea in Peru. The clinical data obtained from the

unteers who developed diarrhea suggested that EAEC 042 caused secretory d

rhea, with short incubation period, absence of fever, and leukocytes or blood

stool. Furthermore, the mucus found in the feces of two patients suggested la

intestinal secretion induced by colonization by EAEC 042. These studies, as w

others that demonstrate the virulence of EAEC for humans, have indica

EAEC is a heterogeneous category of diarrheagenicE. coli , including virulent

strains or not, what seems to depend on factors not yet fully understood.

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

traveler’s diarrhea since the defi nition of this category. The prevalence of EA

TD varies from 19 to 33 %, depending on the geographic region visited (Moha

et al.2011 ).

Studies linked EAEC with diarrhea in HIV-infected adults and children, a gr

usually susceptible to signifi cant cases of protracted diarrhea. EAEC was isol

the only enteropathogen in symptomatic patients presenting diarrhea for 30

(Polotsky et al.1997 ). In addition, isolation of EAEC was similar in a case/contro

study of HIV patients (Medina et al.2010 ).

Several outbreaks of gastroenteritis caused by EAEC have been reported i

and high-income countries. Some of them involving very impressive numbers

infected children or adults and associated with the consumption of contamina

food. Outbreaks in the UK (Dallman et al.2014 ), Japan (Itoh et al. 1997 ), and Italy

(Scavia et al.2008 ) show the relevance of EAEC in developed countries. In one

the Japanese outbreaks, 2697 schoolchildren were affected after consum

school lunches (Itoh et al.1997). In Italy, the outbreaks were transmitted by unpas-

teurized cheese. EAEC was also responsible for outbreaks in developing coun

(Cobeljic et al.1996 ).

1.3 Clinical Features

The most common symptoms reported in EAEC infection are watery diarrhea

mucoid, with or without blood and abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and low

These signs and symptoms are often self-limited but some selected patients

develop persistent diarrhea (≥14 days). The diversity of clinical symptoms in

pathotype infection may be due to heterogeneity between EAEC isolates, infe

dose, genetic susceptibility factors in the host, as well as the immune

(Harrington et al.2006 ).

In order to better characterize the virulent properties of EAEC, studi

human volunteers receiving oral inoculum of different EAEC strains were

formed (Mathewson et al.1986 ; Nataro et al.1992 , 1995 ).

Nataro and colleagues evaluated four different EAEC isolated from diff

geographic regions and different serotypes in volunteers (Nataro et al.1995 ). In this

study, the volunteers ingested dose of 1010 CFU and just EAEC O42 (serotype

O44:H18) caused diarrhea in three out of fi ve volunteers. EAEC 042 was isola

from a case of childhood diarrhea in Peru. The clinical data obtained from the

unteers who developed diarrhea suggested that EAEC 042 caused secretory d

rhea, with short incubation period, absence of fever, and leukocytes or blood

stool. Furthermore, the mucus found in the feces of two patients suggested la

intestinal secretion induced by colonization by EAEC 042. These studies, as w

others that demonstrate the virulence of EAEC for humans, have indica

EAEC is a heterogeneous category of diarrheagenicE. coli , including virulent

strains or not, what seems to depend on factors not yet fully understood.

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

31

1.4 Histopathology

Studies in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo, evaluating EAEC interactions with intest

cells from animals or humans, have tried to elucidate the pathogenesis

pathotype since its description in 1987. The fi rst study about EAEC pathogen

in animal models employed ligated ileal loop of rabbit and rat intestines (Vial

1988 ), showing that EAEC 042 and 17-2 strongly adhered to the mucosa and

ing shortening of microvilli, hemorrhagic necrosis with edema, and mononucl

infi ltrates in the submucosa. Analysis by transmission electron microscopy re

no bacterial invasion and the microvilli architecture was preserved.

Other studies employing in vitro organ culture (IVOC) models have elucid

the intestinal alterations induced by EAEC in fragments of human biopsies of

denum, ileum, and colon (Hicks et al. 1996 ; Nataro et al. 1996 ). Cytotoxic e

the colon were observed, such as microvilli vesiculation, enlarged crypt open

and increased epithelial cell extrusion (Hicks et al.1996 ). Also using IVOC, Nataro

and colleagues demonstrated strong adhesion of EAEC 042 to jejunal

ileum, and more intensely to the colon, while 042 cured of the pAA2 plasmid

this ability (Nataro et al.1996 ). All together, these data strongly indicated that EA

virulence was probable due to intestinal colonization, mainly to the colonic m

in the characteristic aggregative manner, with bacteria forming strong biofi lm

increased mucus layer, followed by cytotoxic and pro-infl ammatory effects

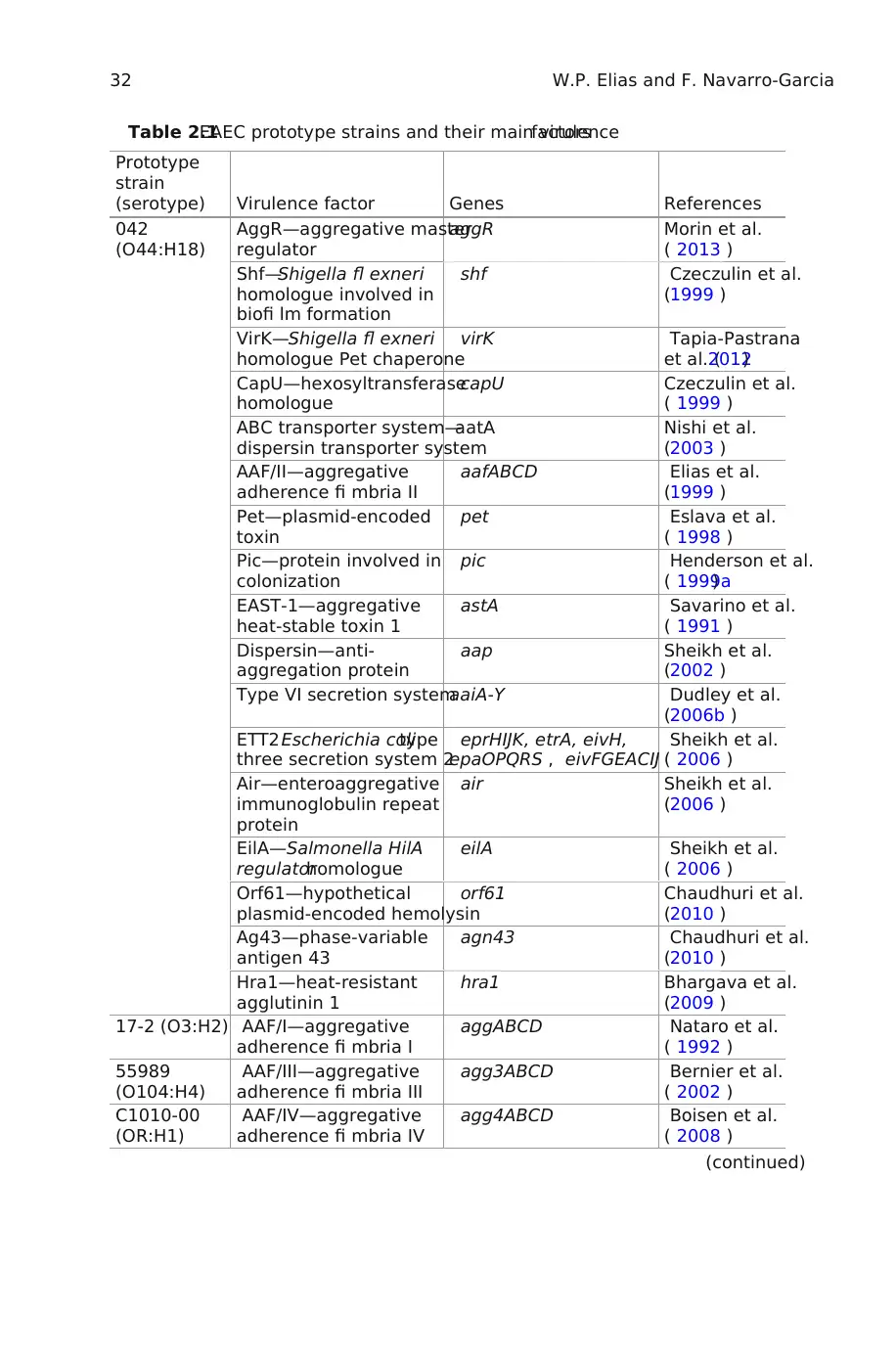

1.5 Strain Heterogeneity

In the decades that followed its original description, EAEC strains have been

acterized in numerous studies around the world, highlighting the particular h

geneity of this category in terms of serotypes, genetic determinants lin

virulence and phylogenetic groups (Boisen et al. 2012; Chattaway et al. 2014b ;

Czeczulin et al.1999; Jenkins et al.2006 ). This heterogeneity together with the

fact that not all EAEC strains were able to cause diarrhea in experimental infe

of humans raises the idea that only a subset of EAEC strains, carrying a speci

of virulence factors, has the capacity to cause diarrhea. This set of factors ha

been determined.

After demonstrating its pathogenicity in human volunteers, EAEC 042 beca

genetically and phenotypically widely studied and considered the prototype s

for EAEC. Major advances in understanding the pathogenesis of EAEC result

from data obtained with this strain whose genome has been sequenced (Chau

et al.2010 ). Other EAEC strains have been also used as prototype in studies d

ing virulence factors and pathogenic mechanisms not present in EAEC 042. D

the variety of identifi ed virulence factors, such as enterotoxins, cytotoxins, s

proteins, outer membrane proteins, and fi mbriae (Table2.1 ), the pathogenesis of the

diarrhea caused by EAEC remains unclear.

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

1.4 Histopathology

Studies in vitro, in vivo, and ex vivo, evaluating EAEC interactions with intest

cells from animals or humans, have tried to elucidate the pathogenesis

pathotype since its description in 1987. The fi rst study about EAEC pathogen

in animal models employed ligated ileal loop of rabbit and rat intestines (Vial

1988 ), showing that EAEC 042 and 17-2 strongly adhered to the mucosa and

ing shortening of microvilli, hemorrhagic necrosis with edema, and mononucl

infi ltrates in the submucosa. Analysis by transmission electron microscopy re

no bacterial invasion and the microvilli architecture was preserved.

Other studies employing in vitro organ culture (IVOC) models have elucid

the intestinal alterations induced by EAEC in fragments of human biopsies of

denum, ileum, and colon (Hicks et al. 1996 ; Nataro et al. 1996 ). Cytotoxic e

the colon were observed, such as microvilli vesiculation, enlarged crypt open

and increased epithelial cell extrusion (Hicks et al.1996 ). Also using IVOC, Nataro

and colleagues demonstrated strong adhesion of EAEC 042 to jejunal

ileum, and more intensely to the colon, while 042 cured of the pAA2 plasmid

this ability (Nataro et al.1996 ). All together, these data strongly indicated that EA

virulence was probable due to intestinal colonization, mainly to the colonic m

in the characteristic aggregative manner, with bacteria forming strong biofi lm

increased mucus layer, followed by cytotoxic and pro-infl ammatory effects

1.5 Strain Heterogeneity

In the decades that followed its original description, EAEC strains have been

acterized in numerous studies around the world, highlighting the particular h

geneity of this category in terms of serotypes, genetic determinants lin

virulence and phylogenetic groups (Boisen et al. 2012; Chattaway et al. 2014b ;

Czeczulin et al.1999; Jenkins et al.2006 ). This heterogeneity together with the

fact that not all EAEC strains were able to cause diarrhea in experimental infe

of humans raises the idea that only a subset of EAEC strains, carrying a speci

of virulence factors, has the capacity to cause diarrhea. This set of factors ha

been determined.

After demonstrating its pathogenicity in human volunteers, EAEC 042 beca

genetically and phenotypically widely studied and considered the prototype s

for EAEC. Major advances in understanding the pathogenesis of EAEC result

from data obtained with this strain whose genome has been sequenced (Chau

et al.2010 ). Other EAEC strains have been also used as prototype in studies d

ing virulence factors and pathogenic mechanisms not present in EAEC 042. D

the variety of identifi ed virulence factors, such as enterotoxins, cytotoxins, s

proteins, outer membrane proteins, and fi mbriae (Table2.1 ), the pathogenesis of the

diarrhea caused by EAEC remains unclear.

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

32

Table 2.1EAEC prototype strains and their main virulencefactors

Prototype

strain

(serotype) Virulence factor Genes References

042

(O44:H18)

AggR—aggregative master

regulator

aggR Morin et al.

( 2013 )

Shf—Shigella fl exneri

homologue involved in

biofi lm formation

shf Czeczulin et al.

(1999 )

VirK—Shigella fl exneri

homologue Pet chaperone

virK Tapia-Pastrana

et al. (2012)

CapU—hexosyltransferase

homologue

capU Czeczulin et al.

( 1999 )

ABC transporter system—

dispersin transporter system

aatA Nishi et al.

(2003 )

AAF/II—aggregative

adherence fi mbria II

aafABCD Elias et al.

(1999 )

Pet—plasmid-encoded

toxin

pet Eslava et al.

( 1998 )

Pic—protein involved in

colonization

pic Henderson et al.

( 1999a)

EAST-1—aggregative

heat-stable toxin 1

astA Savarino et al.

( 1991 )

Dispersin—anti-

aggregation protein

aap Sheikh et al.

(2002 )

Type VI secretion systemaaiA-Y Dudley et al.

(2006b )

ETT2 Escherichia colitype

three secretion system 2

eprHIJK, etrA, eivH,

epaOPQRS , eivFGEACIJ

Sheikh et al.

( 2006 )

Air—enteroaggregative

immunoglobulin repeat

protein

air Sheikh et al.

(2006 )

EilA—Salmonella HilA

regulatorhomologue

eilA Sheikh et al.

( 2006 )

Orf61—hypothetical

plasmid-encoded hemolysin

orf61 Chaudhuri et al.

(2010 )

Ag43—phase-variable

antigen 43

agn43 Chaudhuri et al.

(2010 )

Hra1—heat-resistant

agglutinin 1

hra1 Bhargava et al.

(2009 )

17-2 (O3:H2) AAF/I—aggregative

adherence fi mbria I

aggABCD Nataro et al.

( 1992 )

55989

(O104:H4)

AAF/III—aggregative

adherence fi mbria III

agg3ABCD Bernier et al.

( 2002 )

C1010-00

(OR:H1)

AAF/IV—aggregative

adherence fi mbria IV

agg4ABCD Boisen et al.

( 2008 )

(continued)

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

Table 2.1EAEC prototype strains and their main virulencefactors

Prototype

strain

(serotype) Virulence factor Genes References

042

(O44:H18)

AggR—aggregative master

regulator

aggR Morin et al.

( 2013 )

Shf—Shigella fl exneri

homologue involved in

biofi lm formation

shf Czeczulin et al.

(1999 )

VirK—Shigella fl exneri

homologue Pet chaperone

virK Tapia-Pastrana

et al. (2012)

CapU—hexosyltransferase

homologue

capU Czeczulin et al.

( 1999 )

ABC transporter system—

dispersin transporter system

aatA Nishi et al.

(2003 )

AAF/II—aggregative

adherence fi mbria II

aafABCD Elias et al.

(1999 )

Pet—plasmid-encoded

toxin

pet Eslava et al.

( 1998 )

Pic—protein involved in

colonization

pic Henderson et al.

( 1999a)

EAST-1—aggregative

heat-stable toxin 1

astA Savarino et al.

( 1991 )

Dispersin—anti-

aggregation protein

aap Sheikh et al.

(2002 )

Type VI secretion systemaaiA-Y Dudley et al.

(2006b )

ETT2 Escherichia colitype

three secretion system 2

eprHIJK, etrA, eivH,

epaOPQRS , eivFGEACIJ

Sheikh et al.

( 2006 )

Air—enteroaggregative

immunoglobulin repeat

protein

air Sheikh et al.

(2006 )

EilA—Salmonella HilA

regulatorhomologue

eilA Sheikh et al.

( 2006 )

Orf61—hypothetical

plasmid-encoded hemolysin

orf61 Chaudhuri et al.

(2010 )

Ag43—phase-variable

antigen 43

agn43 Chaudhuri et al.

(2010 )

Hra1—heat-resistant

agglutinin 1

hra1 Bhargava et al.

(2009 )

17-2 (O3:H2) AAF/I—aggregative

adherence fi mbria I

aggABCD Nataro et al.

( 1992 )

55989

(O104:H4)

AAF/III—aggregative

adherence fi mbria III

agg3ABCD Bernier et al.

( 2002 )

C1010-00

(OR:H1)

AAF/IV—aggregative

adherence fi mbria IV

agg4ABCD Boisen et al.

( 2008 )

(continued)

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

33

Due to the association of AA phenotype with high-molecular weight plasm

carrying large number of plasmid-encoded virulence factors in EAEC, these

mids are called aggregative virulence plasmids or pAA (Harrington et al.2006 ).

From the pAA1 plasmid present in the prototype EAEC 17-2 (serotype O3:H

Baudry et al. ( 1990 ) isolated the CVD432 probe fragment, widely us

molecular diagnosis of EAEC. Plasmid pAA2, present in the EAEC 042, also ha

approximately 100 kb of genetic information and encodes many well-charact

virulence factors (Czeczulin et al.1999 ).

AggR is a transcriptional activator and regulates the expression of various

lence factors present in the chromosome and pAA2 plasmid of EAEC 042, defi

the AggR regulon (Harrington et al.2006 ). At least 44 genes are regulated byaggR ,

including the genes for AAF/II biogenesis, dispersin and its secretion system,

CapU, theaai type VI secretion system, andaagR itself (Morin et al.2013 ; Dudley

et al.2006b ). Not all EAEC strains harbor aggR and, consequently, the pAA p

mid. Thus, the classifi cation of EAEC was proposed into two subgroups, e.g.,

cal and atypical, taking into account the presence or absence ofaggR , respectively

(Harrington et al. 2006 ). This classifi cation defi nes two groups of strains, on

them consisting of typical strains with higher pathogenic potential due to the

ence of the AggR regulon and the pAA virulence plasmid (Estrada-Gar

Navarro-Garcia2012 ). However, atypical EAEC strains are commonly isolat

from cases of diarrhea, as the sole pathogen (Huang et al.2007 ; Jiang et al. 2002 ).

In one epidemiological study on the etiology of acute diarrhea in childr

Espírito Santo (Brazil), atypical strains were more frequent than typical

(Isabel Scaletsky, unpublished data). In addition, at least two outbreaks of dia

were caused by atypical EAEC (Cobeljic et al. 1996 ), one of them affected m

than two thousand children (Itoh et al.1997 ).

Table 2.1(continued)

Prototype

strain

(serotype) Virulence factor Genes References

C338-14

(O55:H19)

AAF/V—aggregative

adherence fi mbria V

Agg5ABCD Jonsson et al.

(2015 )

C1096

(O4:HNT)

Pil—type IV pilus pilLMNOPQRSTUV Dudley et al.

( 2006a)

JM221

(O92:H33)

AAF/I—aggregative

adherence fi mbria I

aggABCD Mathewson et al.

( 1986 )

60A (ND) Hra2—heat-resistant

agglutinin 2

hra2 Mancini et al.

( 2011)

OR O rough,NT non-typable,ND not determined

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

Due to the association of AA phenotype with high-molecular weight plasm

carrying large number of plasmid-encoded virulence factors in EAEC, these

mids are called aggregative virulence plasmids or pAA (Harrington et al.2006 ).

From the pAA1 plasmid present in the prototype EAEC 17-2 (serotype O3:H

Baudry et al. ( 1990 ) isolated the CVD432 probe fragment, widely us

molecular diagnosis of EAEC. Plasmid pAA2, present in the EAEC 042, also ha

approximately 100 kb of genetic information and encodes many well-charact

virulence factors (Czeczulin et al.1999 ).

AggR is a transcriptional activator and regulates the expression of various

lence factors present in the chromosome and pAA2 plasmid of EAEC 042, defi

the AggR regulon (Harrington et al.2006 ). At least 44 genes are regulated byaggR ,

including the genes for AAF/II biogenesis, dispersin and its secretion system,

CapU, theaai type VI secretion system, andaagR itself (Morin et al.2013 ; Dudley

et al.2006b ). Not all EAEC strains harbor aggR and, consequently, the pAA p

mid. Thus, the classifi cation of EAEC was proposed into two subgroups, e.g.,

cal and atypical, taking into account the presence or absence ofaggR , respectively

(Harrington et al. 2006 ). This classifi cation defi nes two groups of strains, on

them consisting of typical strains with higher pathogenic potential due to the

ence of the AggR regulon and the pAA virulence plasmid (Estrada-Gar

Navarro-Garcia2012 ). However, atypical EAEC strains are commonly isolat

from cases of diarrhea, as the sole pathogen (Huang et al.2007 ; Jiang et al. 2002 ).

In one epidemiological study on the etiology of acute diarrhea in childr

Espírito Santo (Brazil), atypical strains were more frequent than typical

(Isabel Scaletsky, unpublished data). In addition, at least two outbreaks of dia

were caused by atypical EAEC (Cobeljic et al. 1996 ), one of them affected m

than two thousand children (Itoh et al.1997 ).

Table 2.1(continued)

Prototype

strain

(serotype) Virulence factor Genes References

C338-14

(O55:H19)

AAF/V—aggregative

adherence fi mbria V

Agg5ABCD Jonsson et al.

(2015 )

C1096

(O4:HNT)

Pil—type IV pilus pilLMNOPQRSTUV Dudley et al.

( 2006a)

JM221

(O92:H33)

AAF/I—aggregative

adherence fi mbria I

aggABCD Mathewson et al.

( 1986 )

60A (ND) Hra2—heat-resistant

agglutinin 2

hra2 Mancini et al.

( 2011)

OR O rough,NT non-typable,ND not determined

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

34

1.6 Pathogenesis in Three Steps

EAEC ability to mediate diarrhea was clearly established through the

study with EAEC strain 042 (Nataro et al.1995 ). However, this study and others

have left clear that the pathogenesis of EAEC is complex, and EAEC strains ar

very heterogeneous.

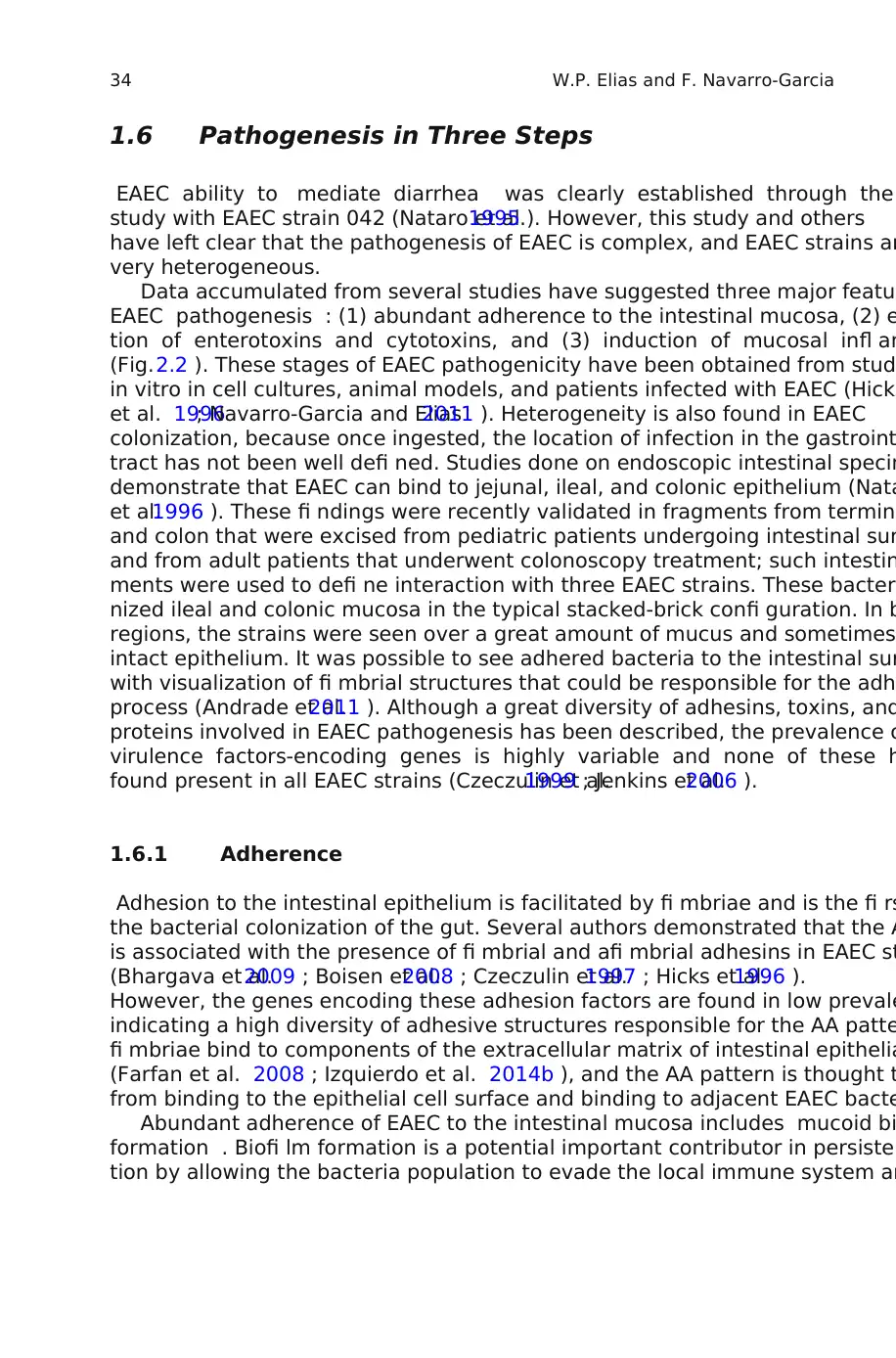

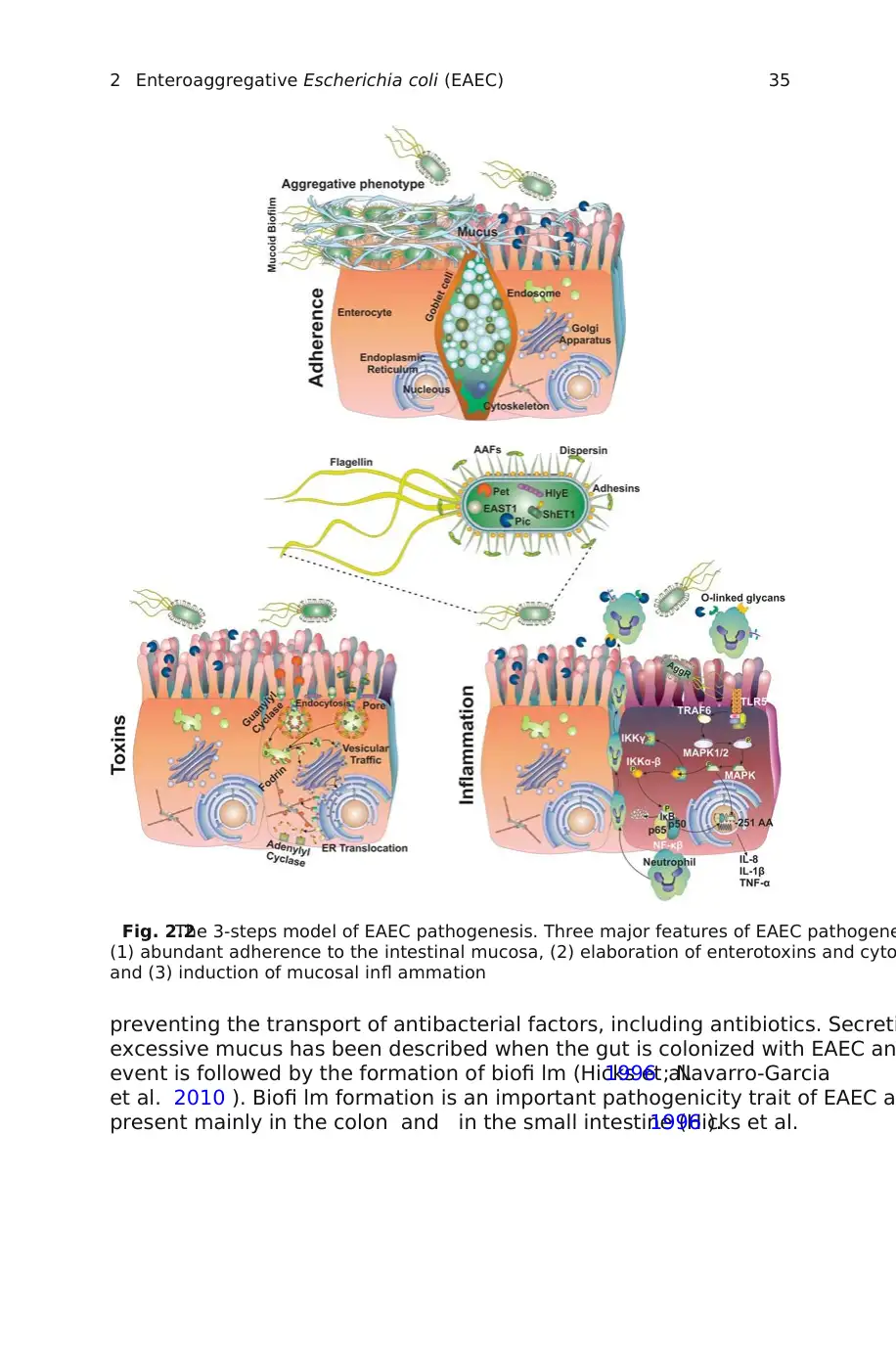

Data accumulated from several studies have suggested three major featur

EAEC pathogenesis : (1) abundant adherence to the intestinal mucosa, (2) e

tion of enterotoxins and cytotoxins, and (3) induction of mucosal infl am

(Fig.2.2 ). These stages of EAEC pathogenicity have been obtained from stud

in vitro in cell cultures, animal models, and patients infected with EAEC (Hicks

et al. 1996; Navarro-Garcia and Elias2011 ). Heterogeneity is also found in EAEC

colonization, because once ingested, the location of infection in the gastroint

tract has not been well defi ned. Studies done on endoscopic intestinal specim

demonstrate that EAEC can bind to jejunal, ileal, and colonic epithelium (Nata

et al.1996 ). These fi ndings were recently validated in fragments from termina

and colon that were excised from pediatric patients undergoing intestinal sur

and from adult patients that underwent colonoscopy treatment; such intestin

ments were used to defi ne interaction with three EAEC strains. These bacter

nized ileal and colonic mucosa in the typical stacked-brick confi guration. In b

regions, the strains were seen over a great amount of mucus and sometimes

intact epithelium. It was possible to see adhered bacteria to the intestinal sur

with visualization of fi mbrial structures that could be responsible for the adh

process (Andrade et al.2011 ). Although a great diversity of adhesins, toxins, and

proteins involved in EAEC pathogenesis has been described, the prevalence o

virulence factors-encoding genes is highly variable and none of these h

found present in all EAEC strains (Czeczulin et al.1999 ; Jenkins et al.2006 ).

1.6.1 Adherence

Adhesion to the intestinal epithelium is facilitated by fi mbriae and is the fi rs

the bacterial colonization of the gut. Several authors demonstrated that the A

is associated with the presence of fi mbrial and afi mbrial adhesins in EAEC st

(Bhargava et al.2009 ; Boisen et al.2008 ; Czeczulin et al.1997 ; Hicks et al.1996 ).

However, the genes encoding these adhesion factors are found in low prevale

indicating a high diversity of adhesive structures responsible for the AA patte

fi mbriae bind to components of the extracellular matrix of intestinal epithelia

(Farfan et al. 2008 ; Izquierdo et al. 2014b ), and the AA pattern is thought t

from binding to the epithelial cell surface and binding to adjacent EAEC bacte

Abundant adherence of EAEC to the intestinal mucosa includes mucoid bi

formation . Biofi lm formation is a potential important contributor in persisten

tion by allowing the bacteria population to evade the local immune system an

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

1.6 Pathogenesis in Three Steps

EAEC ability to mediate diarrhea was clearly established through the

study with EAEC strain 042 (Nataro et al.1995 ). However, this study and others

have left clear that the pathogenesis of EAEC is complex, and EAEC strains ar

very heterogeneous.

Data accumulated from several studies have suggested three major featur

EAEC pathogenesis : (1) abundant adherence to the intestinal mucosa, (2) e

tion of enterotoxins and cytotoxins, and (3) induction of mucosal infl am

(Fig.2.2 ). These stages of EAEC pathogenicity have been obtained from stud

in vitro in cell cultures, animal models, and patients infected with EAEC (Hicks

et al. 1996; Navarro-Garcia and Elias2011 ). Heterogeneity is also found in EAEC

colonization, because once ingested, the location of infection in the gastroint

tract has not been well defi ned. Studies done on endoscopic intestinal specim

demonstrate that EAEC can bind to jejunal, ileal, and colonic epithelium (Nata

et al.1996 ). These fi ndings were recently validated in fragments from termina

and colon that were excised from pediatric patients undergoing intestinal sur

and from adult patients that underwent colonoscopy treatment; such intestin

ments were used to defi ne interaction with three EAEC strains. These bacter

nized ileal and colonic mucosa in the typical stacked-brick confi guration. In b

regions, the strains were seen over a great amount of mucus and sometimes

intact epithelium. It was possible to see adhered bacteria to the intestinal sur

with visualization of fi mbrial structures that could be responsible for the adh

process (Andrade et al.2011 ). Although a great diversity of adhesins, toxins, and

proteins involved in EAEC pathogenesis has been described, the prevalence o

virulence factors-encoding genes is highly variable and none of these h

found present in all EAEC strains (Czeczulin et al.1999 ; Jenkins et al.2006 ).

1.6.1 Adherence

Adhesion to the intestinal epithelium is facilitated by fi mbriae and is the fi rs

the bacterial colonization of the gut. Several authors demonstrated that the A

is associated with the presence of fi mbrial and afi mbrial adhesins in EAEC st

(Bhargava et al.2009 ; Boisen et al.2008 ; Czeczulin et al.1997 ; Hicks et al.1996 ).

However, the genes encoding these adhesion factors are found in low prevale

indicating a high diversity of adhesive structures responsible for the AA patte

fi mbriae bind to components of the extracellular matrix of intestinal epithelia

(Farfan et al. 2008 ; Izquierdo et al. 2014b ), and the AA pattern is thought t

from binding to the epithelial cell surface and binding to adjacent EAEC bacte

Abundant adherence of EAEC to the intestinal mucosa includes mucoid bi

formation . Biofi lm formation is a potential important contributor in persisten

tion by allowing the bacteria population to evade the local immune system an

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

35

preventing the transport of antibacterial factors, including antibiotics. Secreti

excessive mucus has been described when the gut is colonized with EAEC an

event is followed by the formation of biofi lm (Hicks et al.1996 ; Navarro-Garcia

et al. 2010 ). Biofi lm formation is an important pathogenicity trait of EAEC a

present mainly in the colon and in the small intestine (Hicks et al.1996 ).

Fig. 2.2The 3-steps model of EAEC pathogenesis. Three major features of EAEC pathogene

(1) abundant adherence to the intestinal mucosa, (2) elaboration of enterotoxins and cyto

and (3) induction of mucosal infl ammation

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

preventing the transport of antibacterial factors, including antibiotics. Secreti

excessive mucus has been described when the gut is colonized with EAEC an

event is followed by the formation of biofi lm (Hicks et al.1996 ; Navarro-Garcia

et al. 2010 ). Biofi lm formation is an important pathogenicity trait of EAEC a

present mainly in the colon and in the small intestine (Hicks et al.1996 ).

Fig. 2.2The 3-steps model of EAEC pathogenesis. Three major features of EAEC pathogene

(1) abundant adherence to the intestinal mucosa, (2) elaboration of enterotoxins and cyto

and (3) induction of mucosal infl ammation

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

36

1.6.2 Toxins

Once the biofi lm has been established, EAEC produces cytotoxic effects such

microvillus vesiculation, enlarged crypt openings, and increased epithelia

extrusion (Harrington et al.2006 ). It is thought that the secretion of toxins plays a

important role in secretory diarrhea, which is a typical clinical manifest

EAEC infection. Numerous putative EAEC virulence factors, such as Pet, EAST

and ShET1 toxins, and Pic, have been associated to these cytotoxic effects.

1.6.3 Infl ammation

EAEC is an infl ammatory pathogen, as demonstrated both in clinical (Greenb

2002 ) and laboratory (Steiner et al.1998 ) studies. It is clear that multiple factors con

tribute to EAEC-induced infl ammation, and further characterization of the na

EAEC pro-infl ammatory factors will greatly advance the understanding of this

ing pathogen. The initial host infl ammatory response to EAEC infection is dep

on the host innate immune system and the type of EAEC strain causing infect

role of putative virulence genes and clinical outcomes is not well understood;

ever, the presence of several EAEC virulence factors correlate with fi ndings i

ing that levels of fecal cytokines and infl ammatory markers in stools of adult

children with diarrhea are elevated, including interleukin (IL)-1 receptor

IL-1β, IL-8, interferon (INF)-γ, lactoferrin, fecal leukocytes, and occult blood (Ji

et al. 2002 ). The IL-8 infl ammatory response appears to be partially caused

(FliC) in a Caco-2 cell assay, as it was found that an afl agellated mutant of EA

not produce the same infl ammatory response (Steiner et al.2000 ).

Besides the pathogenic EAEC mechanisms, host factors are also determina

EAEC infl ammation. It was found that single nucleotide polymorphisms in the

moter region of the gene encoding the lipopolysaccharide receptor CD14 ar

ated with bacterial diarrhea in US and Canadian travelers to Mexico (Mohame

et al. 2011 ). The CD14 gene encodes a crucial step in the infl ammatory res

bacterial lipopolysaccharide stimulation mediated by the innate immune

Thus, this study found that one SNP in the promoter region of the CD14 gene

associated with an increased risk of EAEC-induced diarrhea. Patients wit

CD14 − 159 TT genotype were signifi cantly associated with EAEC-induced

rhea compared with healthy controls.

1.7 Main Virulence Factors

In the initial stage of EAEC colonization, the role of fi mbrial and afi mbrial ad

is fundamental. Five aggregative adherence fi mbriae (AAF/I–AAF/V) have bee

characterized in EAEC (Boisen et al. 2008 ; Czeczulin et al. 1997 ; Nataro et

Jonsson et al. 2015 ). All AAF fi mbriae are encoded by genes located in the p

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

1.6.2 Toxins

Once the biofi lm has been established, EAEC produces cytotoxic effects such

microvillus vesiculation, enlarged crypt openings, and increased epithelia

extrusion (Harrington et al.2006 ). It is thought that the secretion of toxins plays a

important role in secretory diarrhea, which is a typical clinical manifest

EAEC infection. Numerous putative EAEC virulence factors, such as Pet, EAST

and ShET1 toxins, and Pic, have been associated to these cytotoxic effects.

1.6.3 Infl ammation

EAEC is an infl ammatory pathogen, as demonstrated both in clinical (Greenb

2002 ) and laboratory (Steiner et al.1998 ) studies. It is clear that multiple factors con

tribute to EAEC-induced infl ammation, and further characterization of the na

EAEC pro-infl ammatory factors will greatly advance the understanding of this

ing pathogen. The initial host infl ammatory response to EAEC infection is dep

on the host innate immune system and the type of EAEC strain causing infect

role of putative virulence genes and clinical outcomes is not well understood;

ever, the presence of several EAEC virulence factors correlate with fi ndings i

ing that levels of fecal cytokines and infl ammatory markers in stools of adult

children with diarrhea are elevated, including interleukin (IL)-1 receptor

IL-1β, IL-8, interferon (INF)-γ, lactoferrin, fecal leukocytes, and occult blood (Ji

et al. 2002 ). The IL-8 infl ammatory response appears to be partially caused

(FliC) in a Caco-2 cell assay, as it was found that an afl agellated mutant of EA

not produce the same infl ammatory response (Steiner et al.2000 ).

Besides the pathogenic EAEC mechanisms, host factors are also determina

EAEC infl ammation. It was found that single nucleotide polymorphisms in the

moter region of the gene encoding the lipopolysaccharide receptor CD14 ar

ated with bacterial diarrhea in US and Canadian travelers to Mexico (Mohame

et al. 2011 ). The CD14 gene encodes a crucial step in the infl ammatory res

bacterial lipopolysaccharide stimulation mediated by the innate immune

Thus, this study found that one SNP in the promoter region of the CD14 gene

associated with an increased risk of EAEC-induced diarrhea. Patients wit

CD14 − 159 TT genotype were signifi cantly associated with EAEC-induced

rhea compared with healthy controls.

1.7 Main Virulence Factors

In the initial stage of EAEC colonization, the role of fi mbrial and afi mbrial ad

is fundamental. Five aggregative adherence fi mbriae (AAF/I–AAF/V) have bee

characterized in EAEC (Boisen et al. 2008 ; Czeczulin et al. 1997 ; Nataro et

Jonsson et al. 2015 ). All AAF fi mbriae are encoded by genes located in the p

W.P. Elias and F. Navarro-Garcia

37

plasmids, which regulated by AggR and their biogenesis follows the usher- ch

pathway. Also, a type IV fi mbrial, calledPil pilus, is responsible for the AA pattern in

cultured epithelial cells and abiotic surface and it’s exhibited by an atypical E

strain isolated in the outbreak in Serbia (Cobeljic et al.1996 ; Dudley et al.2006a ).

Non-fi mbrial adhesins, or outer membrane proteins with molecular w

between 30 and 58 kDa, and associated with AA pattern have been described

various EAEC strains (Bhargava et al.2009 ). In addition, Hra1 and Hra2 are heat-

resistant agglutinins involved in autoaggregation, biofi lm formation, and agg

tive adherence phenotypes (Bhargava et al.2009 ; Mancini et al. 2011 ). The presence

of agn43gene, encoding the autotransporter protein antigen 43, was associate

biofi lm formation and autoaggregation in EAEC 042 (Chaudhuri et al.2010 ). The

multifactorial characteristic of the AA phenotype is clear from studies with str

expressing multiple adhesins. Furthermore, the low prevalence of genes enco

these adhesins highlights the great diversity of adhesive structures in EAEC.

The dispersin protein (anti-aggregation protein) is an important EAEC vir

factor that mediates the dispersion of EAEC along the intestinal mucosa (She

et al.2002 ). Dispersin neutralizes the negative charge on the surface of the ba

cell and allows AAF/II fi mbrial projection , leading to anti-aggregation and d

sal of bacteria in the intestinal wall. This protein requires an ABC-type transpo

system encoded by the aatPABCD operon, which is present in the pAA2 plas

(Nishi et al.2003 ).

As described before, EAEC produces cytotoxic effects evident during in vit

and in vivo studies. Several putative virulence factors associated to those cyt

effects have been identifi ed and characterized in EAEC.

The fi rst toxin described in EAEC was the enteroaggregative heat-stabl

1 (EAST-1) , which is related to the heat-stable toxin (STa) of enterotoxigenic

(Savarino et al.1991 ). EAST-1 activates adenylate cyclase inducing increased cy

GMP levels in enterocytes, generating a secretory response (Savarino et al. 1

EAST-1 is a 38 amino acids peptide (4.1 kDa) encoded by astA gene,

located in pAA2 of EAEC 042 (Czeczulin et al.1999 ). Since STa toxin causes

secretory diarrhea, it was believed que EAST-1 was responsible for this effect

EAEC-induced diarrhea. However, the presence of EAST-1 in EAEC 17-2 was n

suffi cient to provoke diarrhea in volunteers (Nataro et al.1995 ).

Another toxin encoded by a chromosomal gene in EAEC 042 is called ShET

(Shigella enterotoxin 1), which is encoded by setAB located in the antisense str

of pic (Henderson et al.1999a ; Navarro-Garcia and Elias2011). ShET1 is an A:B

type toxin that causes accumulation of fl uid in rabbit ileal loops. The enterot

mechanism of ShET1 is independent of cAMP, cGMP, and calcium. However, t

precise mechanism of ShET1 action remains unclear.

Amongst the virulence factors produced by EAEC, the autotransporter prot

have a relevant role in the EAEC pathogenesis. Initially, two autotransporter p

teins were identifi ed in EAEC, comprising high-molecular weight protein

104 kDa for Pet and 109 kDa for Pic (Eslava et al.1998 ; Henderson et al.1999a ).

Autotransporter proteins are currently assigned to the type 5 secretio

(T5SS), which is described in detail in Chap. 10. Autotransporters contain three

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

plasmids, which regulated by AggR and their biogenesis follows the usher- ch

pathway. Also, a type IV fi mbrial, calledPil pilus, is responsible for the AA pattern in

cultured epithelial cells and abiotic surface and it’s exhibited by an atypical E

strain isolated in the outbreak in Serbia (Cobeljic et al.1996 ; Dudley et al.2006a ).

Non-fi mbrial adhesins, or outer membrane proteins with molecular w

between 30 and 58 kDa, and associated with AA pattern have been described

various EAEC strains (Bhargava et al.2009 ). In addition, Hra1 and Hra2 are heat-

resistant agglutinins involved in autoaggregation, biofi lm formation, and agg

tive adherence phenotypes (Bhargava et al.2009 ; Mancini et al. 2011 ). The presence

of agn43gene, encoding the autotransporter protein antigen 43, was associate

biofi lm formation and autoaggregation in EAEC 042 (Chaudhuri et al.2010 ). The

multifactorial characteristic of the AA phenotype is clear from studies with str

expressing multiple adhesins. Furthermore, the low prevalence of genes enco

these adhesins highlights the great diversity of adhesive structures in EAEC.

The dispersin protein (anti-aggregation protein) is an important EAEC vir

factor that mediates the dispersion of EAEC along the intestinal mucosa (She

et al.2002 ). Dispersin neutralizes the negative charge on the surface of the ba

cell and allows AAF/II fi mbrial projection , leading to anti-aggregation and d

sal of bacteria in the intestinal wall. This protein requires an ABC-type transpo

system encoded by the aatPABCD operon, which is present in the pAA2 plas

(Nishi et al.2003 ).

As described before, EAEC produces cytotoxic effects evident during in vit

and in vivo studies. Several putative virulence factors associated to those cyt

effects have been identifi ed and characterized in EAEC.

The fi rst toxin described in EAEC was the enteroaggregative heat-stabl

1 (EAST-1) , which is related to the heat-stable toxin (STa) of enterotoxigenic

(Savarino et al.1991 ). EAST-1 activates adenylate cyclase inducing increased cy

GMP levels in enterocytes, generating a secretory response (Savarino et al. 1

EAST-1 is a 38 amino acids peptide (4.1 kDa) encoded by astA gene,

located in pAA2 of EAEC 042 (Czeczulin et al.1999 ). Since STa toxin causes

secretory diarrhea, it was believed que EAST-1 was responsible for this effect

EAEC-induced diarrhea. However, the presence of EAST-1 in EAEC 17-2 was n

suffi cient to provoke diarrhea in volunteers (Nataro et al.1995 ).

Another toxin encoded by a chromosomal gene in EAEC 042 is called ShET

(Shigella enterotoxin 1), which is encoded by setAB located in the antisense str

of pic (Henderson et al.1999a ; Navarro-Garcia and Elias2011). ShET1 is an A:B

type toxin that causes accumulation of fl uid in rabbit ileal loops. The enterot

mechanism of ShET1 is independent of cAMP, cGMP, and calcium. However, t

precise mechanism of ShET1 action remains unclear.

Amongst the virulence factors produced by EAEC, the autotransporter prot

have a relevant role in the EAEC pathogenesis. Initially, two autotransporter p

teins were identifi ed in EAEC, comprising high-molecular weight protein

104 kDa for Pet and 109 kDa for Pic (Eslava et al.1998 ; Henderson et al.1999a ).

Autotransporter proteins are currently assigned to the type 5 secretio

(T5SS), which is described in detail in Chap. 10. Autotransporters contain three

2 Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 32

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.