Interactive Effect of Factors on Proactive Environmental Strategy

VerifiedAdded on 2021/09/27

|20

|15092

|482

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on a Springer 2009 Journal of Business Ethics article, investigates the complex relationship between a firm's proactive environmental strategy (PES) and its performance. Drawing on the resource-based view and institutional/legitimacy theories, the study explores the interactive effects of internal drivers (e.g., entrepreneurial orientation) and external drivers (e.g., government regulations, customer sensitivity) on a PES. The research examines how these factors influence a firm's sales and profit growth. The study utilizes data from manufacturing firms in New Zealand to test the proposed model. The report highlights the importance of top management support and pollution prevention in defining a PES and emphasizes the need to consider both internal and external perspectives for a comprehensive understanding of a PES's impact. The research aims to provide insights into achieving a competitive advantage through effective environmental strategies.

The Interactive Effect of Internal

and ExternalFactors on a Proactive

EnvironmentalStrategy and its Influence

on a Firm’s Performance

Bulent Menguc

Seigyoung Auh

Lucie Ozanne

ABSTRACT. While the literature on the effective man-

agement of business and natural environment interfaces is

rich and growing,there are stilltwo questions regarding

which the literature has yet to reach a definitive conclu-

sion: (1) what is the interactive effect between internal and

externaldriverson a proactive environmentalstrategy

(PES)? and (2) does a PES influence firm’s performance?

Drawing on the resource-based view forthe internal

drivers’ perspective and institutional and legitimacy theo-

ries for the external drivers’ perspective, this study suggests

that the effect of entrepreneurialorientation on a PES is

moderated by the intensity of government regulations and

customers’ sensitivity to environmental issues. The authors

also examine the relationship between the PES and a firm’s

performance in terms of sales and profit growth. Implica-

tions are discussed regarding the role of a PES in achieving

a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

KEY WORDS: proactive environmental strategy, entre-

preneurialorientation,resource-based view,legitimacy

theory,institutionalpressure,stakeholder theory,natural

environment

Scholarly interestin the antecedentsof a firm’s

proactive environmental strategy (hereafter PES) and

in its impact on performance has been strong and is

growingexponentially(e.g.,Aragon-Correaand

Sharma,2003).This interest is not confined to the

academic community.A recentreportby Business

for SocialResponsibility (2007,pp. 11–35)offers

severalexamplesof firmsengaging in PESs:(1)

DuPont, a $27 billionchemicalcompanywith

operationsin 75 countries,is well regarded for

achieving substantialemission reductionsoverthe

last 15 years, as well as making further commitments

to reach 65% below the 1990-emission levelsby

2010.The companyconsidersinternalcapacity

building importantfor cogenerating socialbenefit,

business opportunity,and growth in the context of

climate change. (2) 3M uses a companywide system

called Pollution Prevention Pays(3P)thatencour-

ages employees at alllevels to rethink products and

processesto eliminate waste.Over the lastthree

decades, the program has generated gains every ye

(3) Bayer has an executive Corporate Sustainability

Board on climate change and a working group on

renewable raw materials.(4) Unilever,which finds

thatraw materialsaccountfor up to 10 timesthe

company’sinternalemissions,givespreference to

suppliers’ products with lower emissions.

We define PES as a top management-supported,

environmentally oriented strategy that focuses on th

prevention (versus control or the reactive using of a

end-of-pipe approach) of wastes, emissions, and pol

lution through continuouslearning,totalquality

environmentalmanagement,risk taking,and plan-

ning (e.g.,Aragon-Correa and Sharma,2003; Hart,

1995). A PES has been predominantly viewed from a

internally driven (competitive) perspective,and the

term is used to describe a firm’s voluntary and inno-

vative activitiesof pollution prevention,which are

initiated and championed by top management (e.g.,

Aragon-Correa and Sharma,2003;Sharma,2000;

Sharma and Vredenburg, 1998). That is, we define a

PES as a higher-order construct that is composed of

two sub-dimensions:pollution-prevention and top

management support of natural environmental issue

Although a PES has generally been approached from

merely a pollution-prevention perspective, we deem

that the inclusion oftop management support,as a

Journalof Business Ethics(2010) 94:279–298 Springer 2009

DOI 10.1007/s10551-009-0264-0

and ExternalFactors on a Proactive

EnvironmentalStrategy and its Influence

on a Firm’s Performance

Bulent Menguc

Seigyoung Auh

Lucie Ozanne

ABSTRACT. While the literature on the effective man-

agement of business and natural environment interfaces is

rich and growing,there are stilltwo questions regarding

which the literature has yet to reach a definitive conclu-

sion: (1) what is the interactive effect between internal and

externaldriverson a proactive environmentalstrategy

(PES)? and (2) does a PES influence firm’s performance?

Drawing on the resource-based view forthe internal

drivers’ perspective and institutional and legitimacy theo-

ries for the external drivers’ perspective, this study suggests

that the effect of entrepreneurialorientation on a PES is

moderated by the intensity of government regulations and

customers’ sensitivity to environmental issues. The authors

also examine the relationship between the PES and a firm’s

performance in terms of sales and profit growth. Implica-

tions are discussed regarding the role of a PES in achieving

a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

KEY WORDS: proactive environmental strategy, entre-

preneurialorientation,resource-based view,legitimacy

theory,institutionalpressure,stakeholder theory,natural

environment

Scholarly interestin the antecedentsof a firm’s

proactive environmental strategy (hereafter PES) and

in its impact on performance has been strong and is

growingexponentially(e.g.,Aragon-Correaand

Sharma,2003).This interest is not confined to the

academic community.A recentreportby Business

for SocialResponsibility (2007,pp. 11–35)offers

severalexamplesof firmsengaging in PESs:(1)

DuPont, a $27 billionchemicalcompanywith

operationsin 75 countries,is well regarded for

achieving substantialemission reductionsoverthe

last 15 years, as well as making further commitments

to reach 65% below the 1990-emission levelsby

2010.The companyconsidersinternalcapacity

building importantfor cogenerating socialbenefit,

business opportunity,and growth in the context of

climate change. (2) 3M uses a companywide system

called Pollution Prevention Pays(3P)thatencour-

ages employees at alllevels to rethink products and

processesto eliminate waste.Over the lastthree

decades, the program has generated gains every ye

(3) Bayer has an executive Corporate Sustainability

Board on climate change and a working group on

renewable raw materials.(4) Unilever,which finds

thatraw materialsaccountfor up to 10 timesthe

company’sinternalemissions,givespreference to

suppliers’ products with lower emissions.

We define PES as a top management-supported,

environmentally oriented strategy that focuses on th

prevention (versus control or the reactive using of a

end-of-pipe approach) of wastes, emissions, and pol

lution through continuouslearning,totalquality

environmentalmanagement,risk taking,and plan-

ning (e.g.,Aragon-Correa and Sharma,2003; Hart,

1995). A PES has been predominantly viewed from a

internally driven (competitive) perspective,and the

term is used to describe a firm’s voluntary and inno-

vative activitiesof pollution prevention,which are

initiated and championed by top management (e.g.,

Aragon-Correa and Sharma,2003;Sharma,2000;

Sharma and Vredenburg, 1998). That is, we define a

PES as a higher-order construct that is composed of

two sub-dimensions:pollution-prevention and top

management support of natural environmental issue

Although a PES has generally been approached from

merely a pollution-prevention perspective, we deem

that the inclusion oftop management support,as a

Journalof Business Ethics(2010) 94:279–298 Springer 2009

DOI 10.1007/s10551-009-0264-0

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

top-down process,is essentialbecause winning the

support and attention of top management is critical for

a PES’s success. Previous researchers who have drawn

on this perspective have advanced our understanding

the effect of a PES on a firm’s competitive advantage

(Sharma and Vredenburg, 1998). Hart (1995), how-

ever,in his originalarticle on the naturalresource-

based framework, has proposed that a strict, internally

driven perspective to a PES is limited.Hart (1995)

arguesthata PES should also accommodatean

external,legitimacy-basedperspectivebecausea

legitimacy-based perspectiveto a PES doesnot

endanger competitive advantage but, in fact, further

strengthens it.

As a consequence,in thisstudy,we testHart’s

propositionaccommodatingthesetwo comple-

mentary perspectivesin the same research setting.

More specifically, we examine the interaction effect

between the internalperspective and the external

perspective on a PES.For example,we respond to

callsby researcherssuch asOliver (1991,p. 710)

who contends:‘‘Research on the combined effects

of resource capitaland institutionalcapitalon firm’s

performance mightbe one approach.’’Based on a

review of the extant literature, we argue that there is

a need to incorporate both the internally driven and

externally driven factors to capture fully the essence

of a PES.

There hasbeen considerable research aimed at

understanding the internally driven perspective ofa

PES by drawing on the resource-based view (RBV)

of the firm (e.g.,Aragon-Correa,1998;Sharma,

2000;Sharma and Vredenburg,1998).We extend

this framework by positing the externally driven

perspectiveas a moderatorthat is expectedto

delineate the boundary conditionsof the influence

of the internally driven perspective.Thatis, rather

than simply including the internaland externalfac-

tors as direct effects on a PES,our modelpursues a

contingency approach that explicates the contextual

conditionsof the impactof an internalfactor’s

contribution to a PES.The externally driven per-

spectivedrawson institutionaltheoryand the

legitimacy literature by incorporating the notion of

corporate socialperformance (e.g.,Hooghiemstra,

2000; Wilmshurst and Frost, 2000). Both the inter-

naland externalperspectives,we suggest,are com-

plementary and capture the extent of a firm’s social

performance and responsiveness. In order to realize a

true and accurate understanding ofthe value-gen-

erating role of a PES, there is a need to include the

interactive effect of the two perspectives.

In orderto summarize,thisstudy hasthe fol-

lowing purposes.First,we develop and testa con-

ceptualmodelthatinvestigateshow the externally

driven perspective,drawingon institutionaland

legitimacytheories,moderatesthe effectof the

internally driven perspective,which has its roots in

the RBV of the firm, and its derivatives(e.g.,

dynamic capabilities,naturalRBV, etc.) on a PES.

Second,we examine the performance ramifications

of a PES in terms of the sales and profit growth of a

firm. If a PES can enhance the salesand profit

growth ofa firm,we deem then thatthiswill be

perceived in a positive lightby managerswho are

contemplating whetherto allocate more resources

and budgetto environmentally friendly strategies.

We use data from variousmanufacturing firmsin

New Zealand, a country known for its commitment

to advancing an environmentalagenda.

In the sections to follow,we revisitthe existing

literature on the internally driven and externally

driven perspectives ofa PES and integrate the two

streams ofresearch into a broader modelof a PES.

We then developour modeland proposeour

hypotheses,followed by our research methodsand

data analysis.Finally,we discussour study’stheo-

reticaland managerialimplications.

Literature review

In accordance with the growing scholarly interest,

previousresearchershave discussed atlength the

performance implications of a PES. The proponents

of a PES have, for long, provided empirical evidence

thata PES isindeed positively related to a firm’s

efficiency and effectiveness (Russo and Fouts, 1997)

There is also, however, equally convincing empirical

evidenceshowing thata PES hasno significant

performanceimpact(Christmann,2000).In her

study,Christmann (2000)discussed someof the

noticeable methodologicalproblems thatmay have

contributed to the inconsistent findings in the cur-

rent literature. While this scholarly debate continues

it is clear that there is a lack of agreement about wh

the antecedentsto a PES are and how they are

combined to influence aPES. A carefulreview,

280 Bulent Menguc et al.

support and attention of top management is critical for

a PES’s success. Previous researchers who have drawn

on this perspective have advanced our understanding

the effect of a PES on a firm’s competitive advantage

(Sharma and Vredenburg, 1998). Hart (1995), how-

ever,in his originalarticle on the naturalresource-

based framework, has proposed that a strict, internally

driven perspective to a PES is limited.Hart (1995)

arguesthata PES should also accommodatean

external,legitimacy-basedperspectivebecausea

legitimacy-based perspectiveto a PES doesnot

endanger competitive advantage but, in fact, further

strengthens it.

As a consequence,in thisstudy,we testHart’s

propositionaccommodatingthesetwo comple-

mentary perspectivesin the same research setting.

More specifically, we examine the interaction effect

between the internalperspective and the external

perspective on a PES.For example,we respond to

callsby researcherssuch asOliver (1991,p. 710)

who contends:‘‘Research on the combined effects

of resource capitaland institutionalcapitalon firm’s

performance mightbe one approach.’’Based on a

review of the extant literature, we argue that there is

a need to incorporate both the internally driven and

externally driven factors to capture fully the essence

of a PES.

There hasbeen considerable research aimed at

understanding the internally driven perspective ofa

PES by drawing on the resource-based view (RBV)

of the firm (e.g.,Aragon-Correa,1998;Sharma,

2000;Sharma and Vredenburg,1998).We extend

this framework by positing the externally driven

perspectiveas a moderatorthat is expectedto

delineate the boundary conditionsof the influence

of the internally driven perspective.Thatis, rather

than simply including the internaland externalfac-

tors as direct effects on a PES,our modelpursues a

contingency approach that explicates the contextual

conditionsof the impactof an internalfactor’s

contribution to a PES.The externally driven per-

spectivedrawson institutionaltheoryand the

legitimacy literature by incorporating the notion of

corporate socialperformance (e.g.,Hooghiemstra,

2000; Wilmshurst and Frost, 2000). Both the inter-

naland externalperspectives,we suggest,are com-

plementary and capture the extent of a firm’s social

performance and responsiveness. In order to realize a

true and accurate understanding ofthe value-gen-

erating role of a PES, there is a need to include the

interactive effect of the two perspectives.

In orderto summarize,thisstudy hasthe fol-

lowing purposes.First,we develop and testa con-

ceptualmodelthatinvestigateshow the externally

driven perspective,drawingon institutionaland

legitimacytheories,moderatesthe effectof the

internally driven perspective,which has its roots in

the RBV of the firm, and its derivatives(e.g.,

dynamic capabilities,naturalRBV, etc.) on a PES.

Second,we examine the performance ramifications

of a PES in terms of the sales and profit growth of a

firm. If a PES can enhance the salesand profit

growth ofa firm,we deem then thatthiswill be

perceived in a positive lightby managerswho are

contemplating whetherto allocate more resources

and budgetto environmentally friendly strategies.

We use data from variousmanufacturing firmsin

New Zealand, a country known for its commitment

to advancing an environmentalagenda.

In the sections to follow,we revisitthe existing

literature on the internally driven and externally

driven perspectives ofa PES and integrate the two

streams ofresearch into a broader modelof a PES.

We then developour modeland proposeour

hypotheses,followed by our research methodsand

data analysis.Finally,we discussour study’stheo-

reticaland managerialimplications.

Literature review

In accordance with the growing scholarly interest,

previousresearchershave discussed atlength the

performance implications of a PES. The proponents

of a PES have, for long, provided empirical evidence

thata PES isindeed positively related to a firm’s

efficiency and effectiveness (Russo and Fouts, 1997)

There is also, however, equally convincing empirical

evidenceshowing thata PES hasno significant

performanceimpact(Christmann,2000).In her

study,Christmann (2000)discussed someof the

noticeable methodologicalproblems thatmay have

contributed to the inconsistent findings in the cur-

rent literature. While this scholarly debate continues

it is clear that there is a lack of agreement about wh

the antecedentsto a PES are and how they are

combined to influence aPES. A carefulreview,

280 Bulent Menguc et al.

however,of Hart’s(1995)originalproposition re-

veals that two complementary perspectives of a PES

exist:(1) an internally driven (or competitive) per-

spective (Aragon-Correa and Sharma, 2003) and (2)

an externally driven (or legitimacy-based)perspec-

tive (Oliver,1991).We now revisitthe existing

literatureon eachperspective,respectively,and

subsequentlyintegratethe two by positingan

interaction between the two perspectives.

Internally driven perspective on a proactive environmental

strategy

Sharma (2000, p. 683) defines a PES as ‘‘a consistent

pattern ofcompany actionstaken to reducethe

environmentalimpactof operations,not to fulfill

environmental regulations or to conform to standard

practices.’’In addition,we add top management

support to such a strategy as an important dimension

of a PES because we see this strategy as a process that is

top-down in nature.Thus,we define a PES asa

higher-order construct that consists of two first-order

dimensions:pollution-prevention and top manage-

ment support of natural environmental issues. Next,

we explain the two sub-dimensions in greater detail.

From a pollution-prevention perspective,a pro-

active (orinnovative)environmentalstrategy isa

reflection ofevolutionaryenvironmentalstrategy

modelsthathave gone beyond the early compli-

ance versus noncompliance categorizations. Previous

researchers have approached PES from a pollution-

prevention versus pollution-control perspective (e.g.,

Hart, 1995; Hart and Ahuja, 1996; Russo and Fouts,

1997),while othershave taken a proactive versus

reactiveperspective(e.g.,Aragon-Correa,1998;

Sharma,2000;Sharmaand Vredenburg,1998).

Nevertheless,both approaches have highlighted the

same phenomenon. That is, while a PES represents a

proactive (orvoluntary and innovative)approach,

pollution-controlstrategiesrepresenta reactive

(or conformance/compliance) approach. A PES aims

to minimize emissions, effluents, and wastes. Central

to a PES are continuous improvement methods that

focus on well-defined environmental objectives rather

than relying on expensive ‘‘end-pipe’’capitalinvest-

ments to control emissions. As Hart (1995) has dem-

onstrated,a PES provides a firm with a competitive

advantage through lower costs, shorter cycle times,

a better utilization of resources and capabilities.

From a top managementsupportive perspective,

we positthata firm’sadoption ofa PES reflects

top management’s commitment to naturalenviron-

mentalissues.Key behaviors on the part ofthe top

managersinclude,butare notlimited to:commu-

nicating and addressing critical environmental issue

initiatingenvironmentalprogramsand policies;

rewarding employeesfor environmentalimprove-

ments;and contributing organizationalresources to

environmentalinitiatives(Berry and Rondinelli,

1998).

In general, top managers’ strategic leadership and

their supportmay play a criticalrole in shaping an

organization’s values and orientation toward natural

environmentalissues (Berry and Rondinelli,1998).

The building ofstrongnetwork tiesinsideand

outsidethe industry,and acquisitionof more

knowledge aboutenvironmentalactivitiesmay in-

crease top managers’sensitivity to environmental

concerns and enable them to benchmark their firm’s

environmental activities with those of competitors in

the marketplace(Menon and Menon,1997).In

addition, previous researchers acknowledge the role

of top management as significant in predicting cor-

poratesocialperformance(Miles, 1987;Weaver

et al.,1999).In firmsthatare described as‘‘com-

mercial and environmentally excellent,’’ support and

involvementfrom top managementon environ-

mental issues are common (Henriques and Sadorsky

1999;Hunt and Auster,1990;Roome, 1992).

Banerjee (1992) argues that the commitment of top

managementis crucialto successfulenvironmental

management.In addition,Coddington (1993)and

Hart (1995)concludethatcorporatevision and

strong leadership are the two key facilitators ofthe

implementation ofa corporatewide,environmental

managementstrategy.To this end,Dechantand

Altman(1994,p. 9) note that ‘‘environmental

leaders inspire a shared value ofthe organization as

environmentally sustainable, creating or maintaining

green valuesthroughoutthe enterprise.’’A good

example oftop managementleadership and proac-

tive involvementon environmentalissuesis the

environmentalposition taken by The Body Shop

and its founder Anita Roddick.

Since Hart’s articlefirst appearedin AMR,

scholars have spent significant time and effort trying

281Interactive Effect ofInternaland ExternalFactors on PES

veals that two complementary perspectives of a PES

exist:(1) an internally driven (or competitive) per-

spective (Aragon-Correa and Sharma, 2003) and (2)

an externally driven (or legitimacy-based)perspec-

tive (Oliver,1991).We now revisitthe existing

literatureon eachperspective,respectively,and

subsequentlyintegratethe two by positingan

interaction between the two perspectives.

Internally driven perspective on a proactive environmental

strategy

Sharma (2000, p. 683) defines a PES as ‘‘a consistent

pattern ofcompany actionstaken to reducethe

environmentalimpactof operations,not to fulfill

environmental regulations or to conform to standard

practices.’’In addition,we add top management

support to such a strategy as an important dimension

of a PES because we see this strategy as a process that is

top-down in nature.Thus,we define a PES asa

higher-order construct that consists of two first-order

dimensions:pollution-prevention and top manage-

ment support of natural environmental issues. Next,

we explain the two sub-dimensions in greater detail.

From a pollution-prevention perspective,a pro-

active (orinnovative)environmentalstrategy isa

reflection ofevolutionaryenvironmentalstrategy

modelsthathave gone beyond the early compli-

ance versus noncompliance categorizations. Previous

researchers have approached PES from a pollution-

prevention versus pollution-control perspective (e.g.,

Hart, 1995; Hart and Ahuja, 1996; Russo and Fouts,

1997),while othershave taken a proactive versus

reactiveperspective(e.g.,Aragon-Correa,1998;

Sharma,2000;Sharmaand Vredenburg,1998).

Nevertheless,both approaches have highlighted the

same phenomenon. That is, while a PES represents a

proactive (orvoluntary and innovative)approach,

pollution-controlstrategiesrepresenta reactive

(or conformance/compliance) approach. A PES aims

to minimize emissions, effluents, and wastes. Central

to a PES are continuous improvement methods that

focus on well-defined environmental objectives rather

than relying on expensive ‘‘end-pipe’’capitalinvest-

ments to control emissions. As Hart (1995) has dem-

onstrated,a PES provides a firm with a competitive

advantage through lower costs, shorter cycle times,

a better utilization of resources and capabilities.

From a top managementsupportive perspective,

we positthata firm’sadoption ofa PES reflects

top management’s commitment to naturalenviron-

mentalissues.Key behaviors on the part ofthe top

managersinclude,butare notlimited to:commu-

nicating and addressing critical environmental issue

initiatingenvironmentalprogramsand policies;

rewarding employeesfor environmentalimprove-

ments;and contributing organizationalresources to

environmentalinitiatives(Berry and Rondinelli,

1998).

In general, top managers’ strategic leadership and

their supportmay play a criticalrole in shaping an

organization’s values and orientation toward natural

environmentalissues (Berry and Rondinelli,1998).

The building ofstrongnetwork tiesinsideand

outsidethe industry,and acquisitionof more

knowledge aboutenvironmentalactivitiesmay in-

crease top managers’sensitivity to environmental

concerns and enable them to benchmark their firm’s

environmental activities with those of competitors in

the marketplace(Menon and Menon,1997).In

addition, previous researchers acknowledge the role

of top management as significant in predicting cor-

poratesocialperformance(Miles, 1987;Weaver

et al.,1999).In firmsthatare described as‘‘com-

mercial and environmentally excellent,’’ support and

involvementfrom top managementon environ-

mental issues are common (Henriques and Sadorsky

1999;Hunt and Auster,1990;Roome, 1992).

Banerjee (1992) argues that the commitment of top

managementis crucialto successfulenvironmental

management.In addition,Coddington (1993)and

Hart (1995)concludethatcorporatevision and

strong leadership are the two key facilitators ofthe

implementation ofa corporatewide,environmental

managementstrategy.To this end,Dechantand

Altman(1994,p. 9) note that ‘‘environmental

leaders inspire a shared value ofthe organization as

environmentally sustainable, creating or maintaining

green valuesthroughoutthe enterprise.’’A good

example oftop managementleadership and proac-

tive involvementon environmentalissuesis the

environmentalposition taken by The Body Shop

and its founder Anita Roddick.

Since Hart’s articlefirst appearedin AMR,

scholars have spent significant time and effort trying

281Interactive Effect ofInternaland ExternalFactors on PES

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

to understand the fundamentalpropositionsof the

natural resource-based view (NRBV). Similarly, the

internally driven (orcompetitive)perspective has

received considerable attention.More recently,this

perspective hasbeen located within the ‘‘dynamic

capabilities’’approach (Aragon-Correa and Sharma,

2003). Eisenhardt and Martin (2000, p. 1107) define

dynamic capabilities as ‘‘the firm’s processes that use

resources– especially theprocessesto integrate,

reconfigure, gain and release resources – to match and

even create marketchange.Dynamic capabilities,

thus, are the organizational and strategic routines by

which firms achieve new resource configurations as

markets emerge, collide, split, evolve, and die.’’

According to proponents of this perspective (e.g.,

Aragon-Correa and Sharma,2003),a PES,from a

pollution-prevention and top management support-

ive perspective, is consistent with the very definition

of dynamic capabilities for several reasons. First, a PES

shares a fundamental proposition with the NRBV in

that‘‘to the extent[that]these practicesare tacit,

casually ambiguous,firm specific,socially complex,

path dependent, and value adding for consumers, they

may provide advantage’’(Aragon-Correa and Shar-

ma, 2003, p. 74). In fact, the adoption of a PES results

in a substantialcompetitive advantage due to (pro-

cess-driven)cost advantages(Aragon-Correaand

Sharma,2003;Hart,1995;Hartand Ahuja,1996;

Klassen and Whybark, 1999; Majumdar and Marcus,

2001) and (product-driven) differentiation advantages

(Hart, 1995). A long-term, sustainable advantage lies

in the resource configurationsthatmanagersbuild

using aPES (Aragon-Correaand Sharma,2003;

Christmann, 2000).

Second,a PES is idiosyncratic (i.e.,organization

specific) due to its social complexity (Aragon-Correa

and Sharma,2003).For example,Majumdarand

Marcus (2001) showed that when managers create a

balance between regulatory policiesand theirdis-

cretion, they can enjoy entrepreneurship, creativity,

and risk taking;conductR&D; and even develop

new technologies, which are all important resources

for a PES. Sharma (2000) found that the managerial

interpretationof the environmenteitheras an

opportunity ora threatinfluencesthe extentto

which a PES is deployed.To this end,Marcus and

Geffen (1998, p. 1147) came to the conclusion that

‘‘key playersare likely to interpretthe conditions

they face and assign meaning to the actions they take

in fairly idiosyncratic ways.’’Therefore,depending

on the dominant coalition’s attitude and commitmen

to naturalenvironmentalissues,the adoption and

implementation ofa PES can be viewed asan

opportunity to generate growth or asa threatand

disruption to existing operations.Andersson and

Bateman’s(2000)study showsthatthe successof

employee-championing behaviors regarding natural

environmental issues depends on their alignment wi

top management’s positive attention and actions to-

ward these issues. Thus, we view top management’s

supportof naturalenvironmentalissues to be idio-

syncratic and organization specific because manage

rialvision,leadership,and focus are distinctive and

socially complex.

Third, a dynamic capability approach to a PES

entails a complex integration and reconfiguration of

organizational,managerial,higher-orderlearning,

and divergentstakeholderperspectives(Aragon-

Correa and Sharma,2003).To thisend,a PES is

consistent with the dynamic capability perspective in

that a PES involves an intricate integration of pollu-

tion prevention, and managerial support and leader-

ship. Sharma and Vredenburg (1998) have shown th

competitivelyvaluableorganizationalcapabilities

such as stakeholder integration,continuous innova-

tion, and higher-order learning may emerge from the

adoption of a PES.

Fourth,the application ofa PES involvespath

dependency.It necessitatesthe integrationand

combination oftacitcapabilitiesthatlead to causal

ambiguity and barriersto imitation.The effective

formulation and execution ofa PES demandsthe

alignmentof the appropriate controlmechanisms

with incentives eliciting organizationalstructures so

that all employees are motivated to participate activ

in the delivery ofthe strategy (Aragon-Correa and

Sharma, 2003).

Externally driven perspective on a proactive environ

strategy

In addition to the internally driven perspective,a

PES needsto take into consideration externally

driven (orlegitimacy-based)activitiesunderinsti-

tutionalpressure because a purely internally driven

approach may prove inadequate due to issuesof

external(social)legitimacy and reputation (Hart,

282 Bulent Menguc et al.

natural resource-based view (NRBV). Similarly, the

internally driven (orcompetitive)perspective has

received considerable attention.More recently,this

perspective hasbeen located within the ‘‘dynamic

capabilities’’approach (Aragon-Correa and Sharma,

2003). Eisenhardt and Martin (2000, p. 1107) define

dynamic capabilities as ‘‘the firm’s processes that use

resources– especially theprocessesto integrate,

reconfigure, gain and release resources – to match and

even create marketchange.Dynamic capabilities,

thus, are the organizational and strategic routines by

which firms achieve new resource configurations as

markets emerge, collide, split, evolve, and die.’’

According to proponents of this perspective (e.g.,

Aragon-Correa and Sharma,2003),a PES,from a

pollution-prevention and top management support-

ive perspective, is consistent with the very definition

of dynamic capabilities for several reasons. First, a PES

shares a fundamental proposition with the NRBV in

that‘‘to the extent[that]these practicesare tacit,

casually ambiguous,firm specific,socially complex,

path dependent, and value adding for consumers, they

may provide advantage’’(Aragon-Correa and Shar-

ma, 2003, p. 74). In fact, the adoption of a PES results

in a substantialcompetitive advantage due to (pro-

cess-driven)cost advantages(Aragon-Correaand

Sharma,2003;Hart,1995;Hartand Ahuja,1996;

Klassen and Whybark, 1999; Majumdar and Marcus,

2001) and (product-driven) differentiation advantages

(Hart, 1995). A long-term, sustainable advantage lies

in the resource configurationsthatmanagersbuild

using aPES (Aragon-Correaand Sharma,2003;

Christmann, 2000).

Second,a PES is idiosyncratic (i.e.,organization

specific) due to its social complexity (Aragon-Correa

and Sharma,2003).For example,Majumdarand

Marcus (2001) showed that when managers create a

balance between regulatory policiesand theirdis-

cretion, they can enjoy entrepreneurship, creativity,

and risk taking;conductR&D; and even develop

new technologies, which are all important resources

for a PES. Sharma (2000) found that the managerial

interpretationof the environmenteitheras an

opportunity ora threatinfluencesthe extentto

which a PES is deployed.To this end,Marcus and

Geffen (1998, p. 1147) came to the conclusion that

‘‘key playersare likely to interpretthe conditions

they face and assign meaning to the actions they take

in fairly idiosyncratic ways.’’Therefore,depending

on the dominant coalition’s attitude and commitmen

to naturalenvironmentalissues,the adoption and

implementation ofa PES can be viewed asan

opportunity to generate growth or asa threatand

disruption to existing operations.Andersson and

Bateman’s(2000)study showsthatthe successof

employee-championing behaviors regarding natural

environmental issues depends on their alignment wi

top management’s positive attention and actions to-

ward these issues. Thus, we view top management’s

supportof naturalenvironmentalissues to be idio-

syncratic and organization specific because manage

rialvision,leadership,and focus are distinctive and

socially complex.

Third, a dynamic capability approach to a PES

entails a complex integration and reconfiguration of

organizational,managerial,higher-orderlearning,

and divergentstakeholderperspectives(Aragon-

Correa and Sharma,2003).To thisend,a PES is

consistent with the dynamic capability perspective in

that a PES involves an intricate integration of pollu-

tion prevention, and managerial support and leader-

ship. Sharma and Vredenburg (1998) have shown th

competitivelyvaluableorganizationalcapabilities

such as stakeholder integration,continuous innova-

tion, and higher-order learning may emerge from the

adoption of a PES.

Fourth,the application ofa PES involvespath

dependency.It necessitatesthe integrationand

combination oftacitcapabilitiesthatlead to causal

ambiguity and barriersto imitation.The effective

formulation and execution ofa PES demandsthe

alignmentof the appropriate controlmechanisms

with incentives eliciting organizationalstructures so

that all employees are motivated to participate activ

in the delivery ofthe strategy (Aragon-Correa and

Sharma, 2003).

Externally driven perspective on a proactive environ

strategy

In addition to the internally driven perspective,a

PES needsto take into consideration externally

driven (orlegitimacy-based)activitiesunderinsti-

tutionalpressure because a purely internally driven

approach may prove inadequate due to issuesof

external(social)legitimacy and reputation (Hart,

282 Bulent Menguc et al.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1995). Suchman (1995, p. 574) defines legitimacy as

‘‘a generalized perception orassumption thatthe

actions of an entity are desirable.’’ Rao et al. (2008)

argue that in emerging industries, new ventures face

the vexing ‘‘liability ofnewness’’problem because

they have to prove to stakeholdersthatthey are

worthy investment opportunities.We contend that

when there are institutionalpressuressuch asgov-

ernmentregulationand consumersensitivityto

environmental issues, a firm’s desire to enhance social

fitness is likely to provide the boundary condition for

the effectiveness ofeconomic fitness.That is,insti-

tutionaltheory suggeststhatwhen there isinstitu-

tional pressure from various stakeholders, improving

sociallegitimacy in the eyes ofits stakeholders can

moderate the degree to which firms adopt a PES based

on internalantecedents (e.g., Oliver, 1991). In fact,

Oliver (1991, p. 150) posits that responding to insti-

tutionalpressure‘‘emphasizesthe importanceof

obtaining legitimacy for purposesof demonstrating

social worthiness.’’

A legitimacy-based view hasits rootsin neo-

institutionaltheory (e.g.,DiMaggio and Powell,

1983; Oliver, 1991). Legitimacy theory is widely used

as a framework to explain strategic choice with regard

to the environmentaland socialbehavior of organi-

zations (Harvey and Schaefer,2001;Hooghiemstra,

2000).Neo-institutionaltheorists(e.g.,DiMaggio

and Powell,1983;Oliver,1991)positthatsince a

competitive strategy may foster cooperative action in

the interestof sociallegitimacy,a competitive

advantage must be created within the broader scope

of sociallegitimacy.From a legitimacy theory per-

spective,attention to the public’s perception ofthe

firm and the reputation of the company will alter the

internalperspective’s impact on a PES (Hooghiem-

stra, 2000). As we outline subsequently, our predic-

tion is that when there is greater social pressure from

stakeholders such as the government and consumers,

the influence of the internal perspective on a PES will

be strengthened.

Because ofthe tacitnature ofa pollution-pre-

vention capability,an external(legitimacy-based)

orientationshould not jeopardizecompetitive

advantage,but rather reinforce and differentiate the

firm’s position through the positive effect of a good

reputation (Hart,1995).Hence,a firm mustalso

maintain legitimacy and build reputation through

communication and transparency to invite external

stakeholders’scrutiny into theiroperations(Hart,

1995; Suchman, 1995).

Interaction between the two perspectives

Based on the preceding literature review, we sugges

that a model attempting to explain a PES should tak

a contingency view and capture how the externally

driven perspective moderatesthe internally driven

perspective’s effect on a PES. We outline the reason

for our approach below.

First, while each perspective emphasizes a differen

aspect of a firm’s management of the business–natu

environmentinterface,both aim to enhance the

firm’s competitive advantage in the natural environ-

mentalarena. While one underscores the economic

fitnessapproach,the otheremphasizesthe social

fitnessapproach.As a consequence,the interplay

between these two approaches can shed light on ho

a PES can be developed.Second,both perspectives

are theory driven and have received attention from

scholars in their respective fields of research. It is als

important to note that both perspectives are designe

to promote a better understanding of the influence o

a PES on a firm’s performance. Indeed, they are not

mutually exclusive paths for firms to follow.

In summary, our review of the literature suggests

that there is a shortage of studies that simultaneous

modelboth the internaland externalperspectives

relating to a PES, and moreover, their interactive ef-

fects.The lack ofsuch a contingency approach in

modeling a PES leads to at least two major problems

that are of concern: First, most studies have subscrib

to only one perspective of a PES and have used the

same term to referto differentaspectsof a firm’s

behavior; this has produced results that are often di

ficult to compare and sometimes contradictory. Sec-

ond, the richness of a PES is not exploited. Adopting

only one perspective impliesthatthe fullrange of

options for a firm seeking to improve its performanc

may not be captured; this can lead to a partial expla

nation of a firm’s performance and to an incomplete

theory. Third, reliance on a direct effects only model

can obstruct the insights that a contingency model,

offering the boundary conditionsof the impactof

internally driven factors on a PES, can provide.

In light of the limitationsassociated with the

extant literature, it is important to develop a model

283Interactive Effect ofInternaland ExternalFactors on PES

‘‘a generalized perception orassumption thatthe

actions of an entity are desirable.’’ Rao et al. (2008)

argue that in emerging industries, new ventures face

the vexing ‘‘liability ofnewness’’problem because

they have to prove to stakeholdersthatthey are

worthy investment opportunities.We contend that

when there are institutionalpressuressuch asgov-

ernmentregulationand consumersensitivityto

environmental issues, a firm’s desire to enhance social

fitness is likely to provide the boundary condition for

the effectiveness ofeconomic fitness.That is,insti-

tutionaltheory suggeststhatwhen there isinstitu-

tional pressure from various stakeholders, improving

sociallegitimacy in the eyes ofits stakeholders can

moderate the degree to which firms adopt a PES based

on internalantecedents (e.g., Oliver, 1991). In fact,

Oliver (1991, p. 150) posits that responding to insti-

tutionalpressure‘‘emphasizesthe importanceof

obtaining legitimacy for purposesof demonstrating

social worthiness.’’

A legitimacy-based view hasits rootsin neo-

institutionaltheory (e.g.,DiMaggio and Powell,

1983; Oliver, 1991). Legitimacy theory is widely used

as a framework to explain strategic choice with regard

to the environmentaland socialbehavior of organi-

zations (Harvey and Schaefer,2001;Hooghiemstra,

2000).Neo-institutionaltheorists(e.g.,DiMaggio

and Powell,1983;Oliver,1991)positthatsince a

competitive strategy may foster cooperative action in

the interestof sociallegitimacy,a competitive

advantage must be created within the broader scope

of sociallegitimacy.From a legitimacy theory per-

spective,attention to the public’s perception ofthe

firm and the reputation of the company will alter the

internalperspective’s impact on a PES (Hooghiem-

stra, 2000). As we outline subsequently, our predic-

tion is that when there is greater social pressure from

stakeholders such as the government and consumers,

the influence of the internal perspective on a PES will

be strengthened.

Because ofthe tacitnature ofa pollution-pre-

vention capability,an external(legitimacy-based)

orientationshould not jeopardizecompetitive

advantage,but rather reinforce and differentiate the

firm’s position through the positive effect of a good

reputation (Hart,1995).Hence,a firm mustalso

maintain legitimacy and build reputation through

communication and transparency to invite external

stakeholders’scrutiny into theiroperations(Hart,

1995; Suchman, 1995).

Interaction between the two perspectives

Based on the preceding literature review, we sugges

that a model attempting to explain a PES should tak

a contingency view and capture how the externally

driven perspective moderatesthe internally driven

perspective’s effect on a PES. We outline the reason

for our approach below.

First, while each perspective emphasizes a differen

aspect of a firm’s management of the business–natu

environmentinterface,both aim to enhance the

firm’s competitive advantage in the natural environ-

mentalarena. While one underscores the economic

fitnessapproach,the otheremphasizesthe social

fitnessapproach.As a consequence,the interplay

between these two approaches can shed light on ho

a PES can be developed.Second,both perspectives

are theory driven and have received attention from

scholars in their respective fields of research. It is als

important to note that both perspectives are designe

to promote a better understanding of the influence o

a PES on a firm’s performance. Indeed, they are not

mutually exclusive paths for firms to follow.

In summary, our review of the literature suggests

that there is a shortage of studies that simultaneous

modelboth the internaland externalperspectives

relating to a PES, and moreover, their interactive ef-

fects.The lack ofsuch a contingency approach in

modeling a PES leads to at least two major problems

that are of concern: First, most studies have subscrib

to only one perspective of a PES and have used the

same term to referto differentaspectsof a firm’s

behavior; this has produced results that are often di

ficult to compare and sometimes contradictory. Sec-

ond, the richness of a PES is not exploited. Adopting

only one perspective impliesthatthe fullrange of

options for a firm seeking to improve its performanc

may not be captured; this can lead to a partial expla

nation of a firm’s performance and to an incomplete

theory. Third, reliance on a direct effects only model

can obstruct the insights that a contingency model,

offering the boundary conditionsof the impactof

internally driven factors on a PES, can provide.

In light of the limitationsassociated with the

extant literature, it is important to develop a model

283Interactive Effect ofInternaland ExternalFactors on PES

thatcan incorporate both perspectives,and more

importantly, demonstrate the interactive effect of the

two on a PES. It is also essentialto substantiate

empirically the effectof a PES on firm’sperfor-

mance. Our model, which we explain next, satisfies

these requirements.

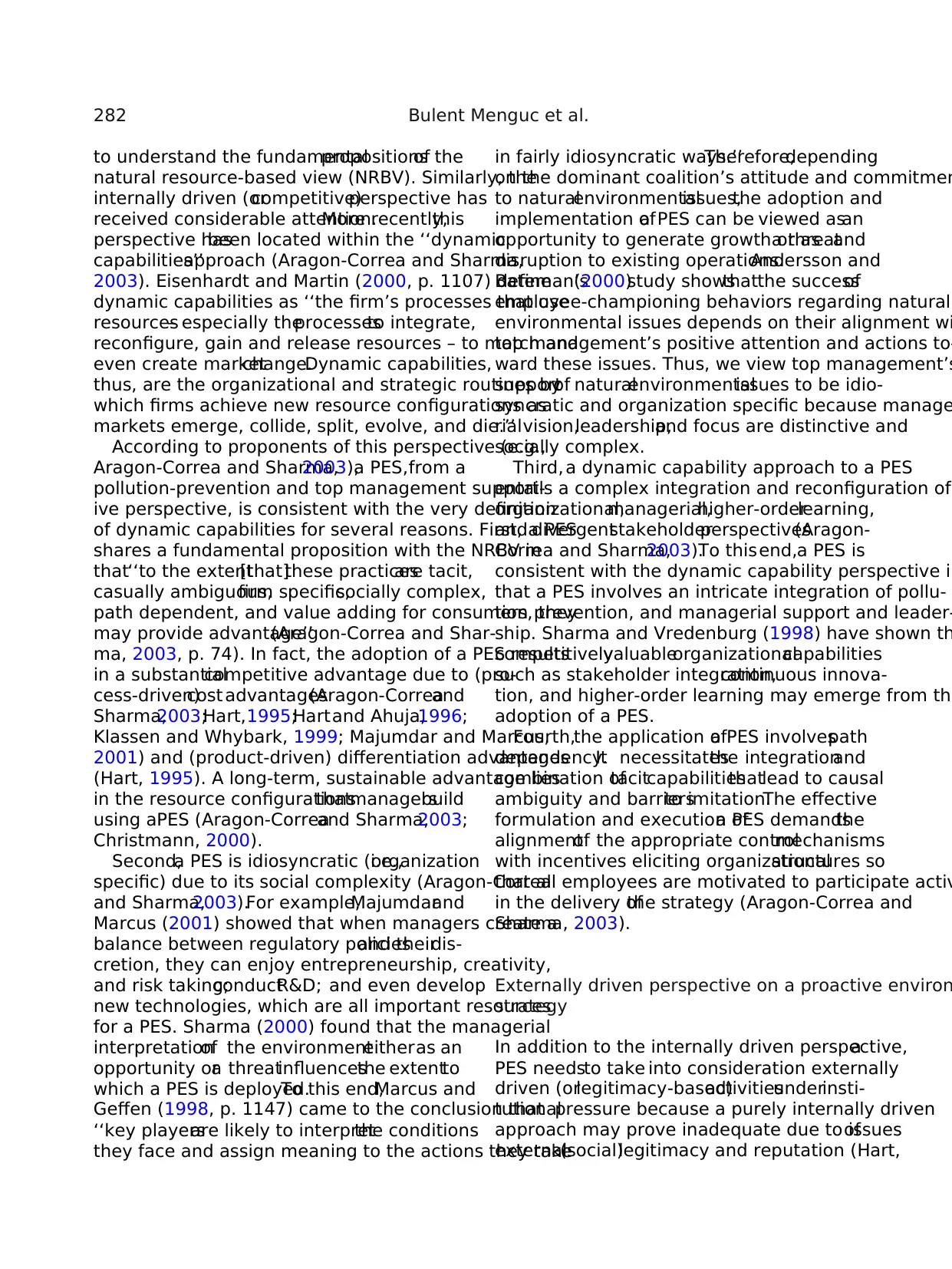

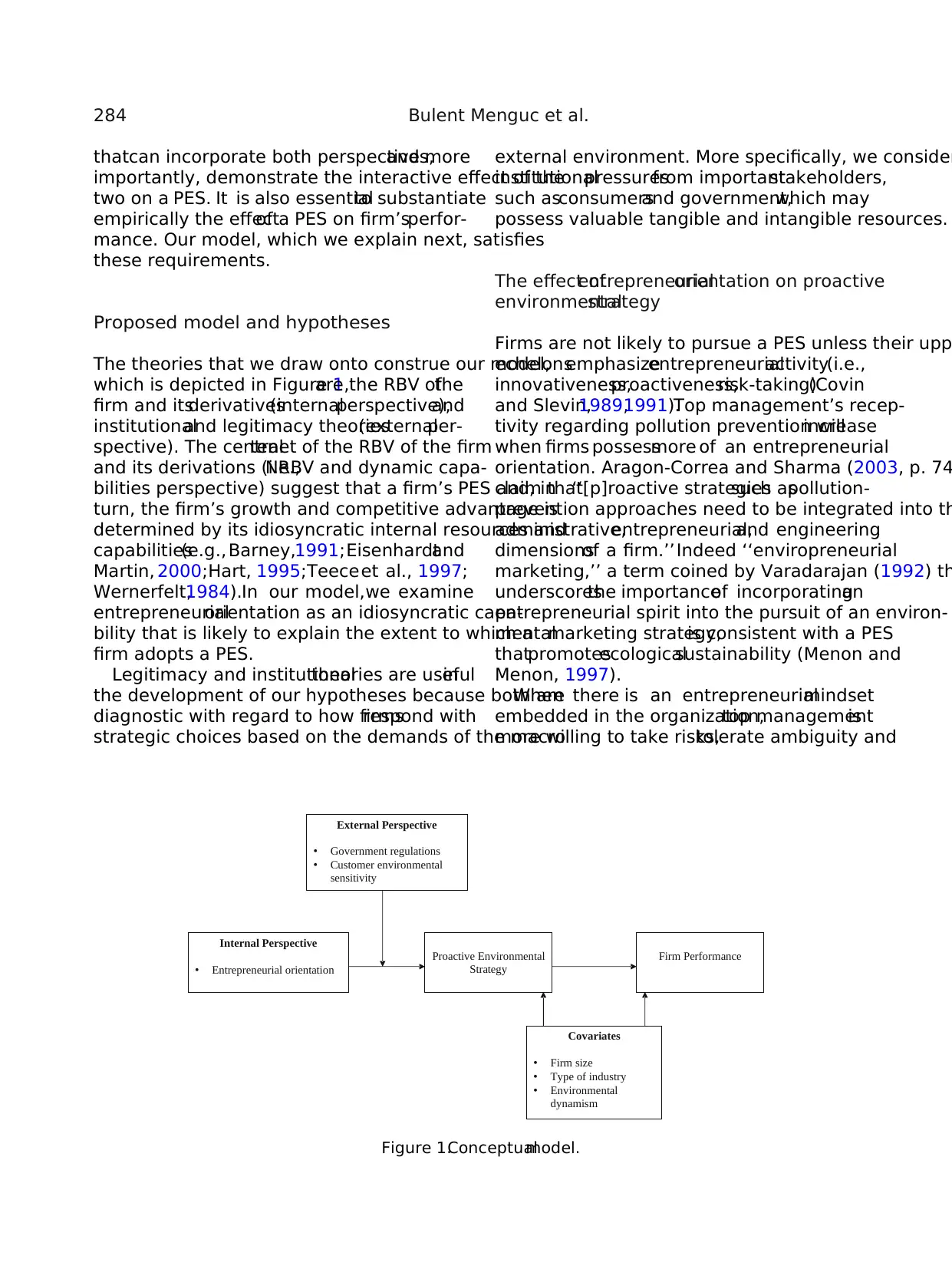

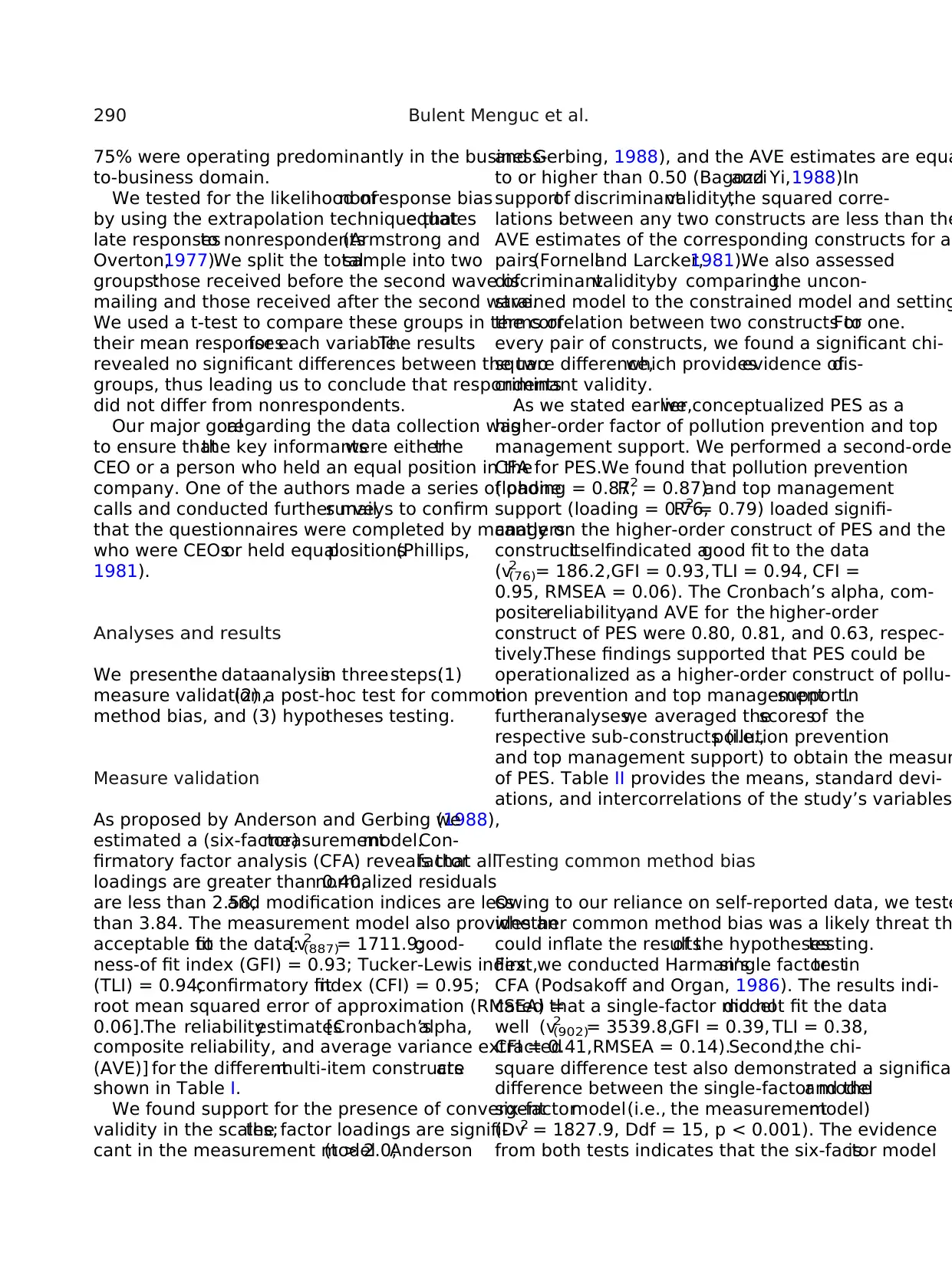

Proposed model and hypotheses

The theories that we draw onto construe our model,

which is depicted in Figure 1,are the RBV ofthe

firm and itsderivatives(internalperspective),and

institutionaland legitimacy theories(externalper-

spective). The centraltenet of the RBV of the firm

and its derivations (i.e.,NRBV and dynamic capa-

bilities perspective) suggest that a firm’s PES and, in

turn, the firm’s growth and competitive advantage is

determined by its idiosyncratic internal resources and

capabilities(e.g., Barney,1991;Eisenhardtand

Martin, 2000;Hart, 1995;Teeceet al., 1997;

Wernerfelt,1984).In our model,we examine

entrepreneurialorientation as an idiosyncratic capa-

bility that is likely to explain the extent to which a

firm adopts a PES.

Legitimacy and institutionaltheories are usefulin

the development of our hypotheses because both are

diagnostic with regard to how firmsrespond with

strategic choices based on the demands of the macro

external environment. More specifically, we consider

institutionalpressuresfrom importantstakeholders,

such asconsumersand government,which may

possess valuable tangible and intangible resources.

The effect ofentrepreneurialorientation on proactive

environmentalstrategy

Firms are not likely to pursue a PES unless their upp

echelonsemphasizeentrepreneurialactivity(i.e.,

innovativeness,proactiveness,risk-taking)(Covin

and Slevin,1989,1991).Top management’s recep-

tivity regarding pollution prevention willincrease

when firms possessmore of an entrepreneurial

orientation. Aragon-Correa and Sharma (2003, p. 74

claim that‘‘[p]roactive strategiessuch aspollution-

prevention approaches need to be integrated into th

administrative,entrepreneurial,and engineering

dimensionsof a firm.’’Indeed ‘‘enviropreneurial

marketing,’’ a term coined by Varadarajan (1992) th

underscoresthe importanceof incorporatingan

entrepreneurial spirit into the pursuit of an environ-

mentalmarketing strategy,is consistent with a PES

thatpromotesecologicalsustainability (Menon and

Menon, 1997).

When there is an entrepreneurialmindset

embedded in the organization,top managementis

more willing to take risks,tolerate ambiguity and

Internal Perspective

• Entrepreneurial orientation

External Perspective

• Government regulations

• Customer environmental

sensitivity

Proactive Environmental

Strategy

Firm Performance

Covariates

• Firm size

• Type of industry

• Environmental

dynamism

Figure 1.Conceptualmodel.

284 Bulent Menguc et al.

importantly, demonstrate the interactive effect of the

two on a PES. It is also essentialto substantiate

empirically the effectof a PES on firm’sperfor-

mance. Our model, which we explain next, satisfies

these requirements.

Proposed model and hypotheses

The theories that we draw onto construe our model,

which is depicted in Figure 1,are the RBV ofthe

firm and itsderivatives(internalperspective),and

institutionaland legitimacy theories(externalper-

spective). The centraltenet of the RBV of the firm

and its derivations (i.e.,NRBV and dynamic capa-

bilities perspective) suggest that a firm’s PES and, in

turn, the firm’s growth and competitive advantage is

determined by its idiosyncratic internal resources and

capabilities(e.g., Barney,1991;Eisenhardtand

Martin, 2000;Hart, 1995;Teeceet al., 1997;

Wernerfelt,1984).In our model,we examine

entrepreneurialorientation as an idiosyncratic capa-

bility that is likely to explain the extent to which a

firm adopts a PES.

Legitimacy and institutionaltheories are usefulin

the development of our hypotheses because both are

diagnostic with regard to how firmsrespond with

strategic choices based on the demands of the macro

external environment. More specifically, we consider

institutionalpressuresfrom importantstakeholders,

such asconsumersand government,which may

possess valuable tangible and intangible resources.

The effect ofentrepreneurialorientation on proactive

environmentalstrategy

Firms are not likely to pursue a PES unless their upp

echelonsemphasizeentrepreneurialactivity(i.e.,

innovativeness,proactiveness,risk-taking)(Covin

and Slevin,1989,1991).Top management’s recep-

tivity regarding pollution prevention willincrease

when firms possessmore of an entrepreneurial

orientation. Aragon-Correa and Sharma (2003, p. 74

claim that‘‘[p]roactive strategiessuch aspollution-

prevention approaches need to be integrated into th

administrative,entrepreneurial,and engineering

dimensionsof a firm.’’Indeed ‘‘enviropreneurial

marketing,’’ a term coined by Varadarajan (1992) th

underscoresthe importanceof incorporatingan

entrepreneurial spirit into the pursuit of an environ-

mentalmarketing strategy,is consistent with a PES

thatpromotesecologicalsustainability (Menon and

Menon, 1997).

When there is an entrepreneurialmindset

embedded in the organization,top managementis

more willing to take risks,tolerate ambiguity and

Internal Perspective

• Entrepreneurial orientation

External Perspective

• Government regulations

• Customer environmental

sensitivity

Proactive Environmental

Strategy

Firm Performance

Covariates

• Firm size

• Type of industry

• Environmental

dynamism

Figure 1.Conceptualmodel.

284 Bulent Menguc et al.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

uncertainty,and ventureinto potentiallyhigh-

rewarding, albeit risky, domains. Managers are more

inclined to interpretnew marketspacesasoppor-

tunitiesthan threats(Dutton and Jackson,1987;

Sharma, 2000). In fact, drawing on the strategic issue

interpretation literature,Sharma (2000) reports that

the more managers interpret environmental issues as

opportunitiesratherthan threats,the more likely

they are to adopt a PES. Such bold, aggressive, and

proactiveattitudesare likely to transferinto the

adoption and implementation ofmore innovative

and creative products and processes that are unique

and difficultto imitate (Russo and Fouts,1997).

Moreover,when thereis a high entrepreneur-

ial orientation,organizationalcapabilities,such as

learning,continuousinnovation,and experimenta-

tion,are present,which lay the foundation for the

adoption ofa PES.Consistentwith our argument,

Aragon-Correa (1998)found thatprospector-type

firmsthatinvesthighly in entrepreneurship,engi-

neering, and administration are more likely to adopt

a PES.

A PES entailsconsiderable risk and uncertainty,

and requires an innovative posture for it to be firmly

established in an organization (Aragon-Correa, 1998;

Aragon-Correa and Sharma, 2003). The proclivity of

top managementto supportnaturalenvironmental

issues is enhanced when an entrepreneurialorienta-

tion ispervasive in the organization.As a conse-

quence, an entrepreneurial orientation with its focus

on seekingnew ventures,growth,and market

opportunities is consistent with the development of a

PES. As a result, a firm’s entrepreneurial orientation is

likely to promote a PES.Thus,we hypothesize the

following:

H1: A firm’sentrepreneurialorientation isrelated

positivelyto a proactiveenvironmental

strategy.

Moderating role ofintensity ofgovernment regulation

Institutional pressures are defined as social, legal, and

culturalforces outside the firm that exert influence

on how managersperceive the environmentand

eventually shape and determine strategic decisions

and behaviors (e.g., DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). In

a natural environmental setting, many external forces

may strengthen a firm’s desire to adopt a PES based

on the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation (Bansal and

Roth, 2000).We considertwo componentsof

institutionalpressure:the intensity ofgovernment

regulation andconsumersensitivityto environ-

mentalissues (e.g.,Kassinis and Vafeas,2006).The

intensity ofgovernmentregulation and consumer

sensitivityto environmentalissuesmay further

motivate firmsto take proactive stepstoward the

adoption of a PES from entrepreneurialorientation.

According to stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984),

the strategic choicesadopted by firmsdepend on

institutionalpressuresand the influence ofimpor-

tantstakeholders(Oliver,1991).More specifically,

Mitchell et al. (1997) showed that stakeholder power

legitimacy,and urgency affecta manager’sattitude

toward stakeholder pressures and requests. This wa

confirmed by Henriques and Sadorsky (1999) who

affirmed that managers in environmentally proactive

firms were more committed to a proactive environ-

mental posture than those in environmentally reacti

firms.

Neo-institutionaltheoristshaveproposedthat

firms,through proactivemoves,may meettheir

stakeholders’expectationsand enhance legitimacy,

therebyobtainingaccessto the scarceresources

neededto surviveand succeed(DiMaggio and

Powell, 1983). For example, Majumdar and Marcus

(2001)showed thatwhen managersachieve a bal-

ancebetween theirdiscretion and governmental

regulatory policies,they may enjoy entrepreneur-

ship, be creative, conduct R & D, and even develop

new technologies,all of which are important

resources for the development of a PES.

Our argumentis also consistentwith legitimacy

theory because a central tenet of this theory is a soc

contractthatimpliesthata company’ssurvivalis

dependenton the extentto which the company

operates within the bounds and norms of the macro

environment,including society,and isviewed as

constructive and performing desirable actions (Brow

and Deegan,1998,p. 22). As a consequence,a

company needsto demonstrate thatits actionsare

legitimate and its behaviors resemble good corporat

citizenship (e.g.,Berman etal., 1999;Miles and

Covin, 2000).

Taking the above into account,we positthat

there is a need to examine the interaction between

the RBV perspective and institutional(legitimacy)

285Interactive Effect ofInternaland ExternalFactors on PES

rewarding, albeit risky, domains. Managers are more

inclined to interpretnew marketspacesasoppor-

tunitiesthan threats(Dutton and Jackson,1987;

Sharma, 2000). In fact, drawing on the strategic issue

interpretation literature,Sharma (2000) reports that

the more managers interpret environmental issues as

opportunitiesratherthan threats,the more likely

they are to adopt a PES. Such bold, aggressive, and

proactiveattitudesare likely to transferinto the

adoption and implementation ofmore innovative

and creative products and processes that are unique

and difficultto imitate (Russo and Fouts,1997).

Moreover,when thereis a high entrepreneur-

ial orientation,organizationalcapabilities,such as

learning,continuousinnovation,and experimenta-

tion,are present,which lay the foundation for the

adoption ofa PES.Consistentwith our argument,

Aragon-Correa (1998)found thatprospector-type

firmsthatinvesthighly in entrepreneurship,engi-

neering, and administration are more likely to adopt

a PES.

A PES entailsconsiderable risk and uncertainty,

and requires an innovative posture for it to be firmly

established in an organization (Aragon-Correa, 1998;

Aragon-Correa and Sharma, 2003). The proclivity of

top managementto supportnaturalenvironmental

issues is enhanced when an entrepreneurialorienta-

tion ispervasive in the organization.As a conse-

quence, an entrepreneurial orientation with its focus

on seekingnew ventures,growth,and market

opportunities is consistent with the development of a

PES. As a result, a firm’s entrepreneurial orientation is

likely to promote a PES.Thus,we hypothesize the

following:

H1: A firm’sentrepreneurialorientation isrelated

positivelyto a proactiveenvironmental

strategy.

Moderating role ofintensity ofgovernment regulation

Institutional pressures are defined as social, legal, and

culturalforces outside the firm that exert influence

on how managersperceive the environmentand

eventually shape and determine strategic decisions

and behaviors (e.g., DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). In

a natural environmental setting, many external forces

may strengthen a firm’s desire to adopt a PES based

on the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation (Bansal and

Roth, 2000).We considertwo componentsof

institutionalpressure:the intensity ofgovernment

regulation andconsumersensitivityto environ-

mentalissues (e.g.,Kassinis and Vafeas,2006).The

intensity ofgovernmentregulation and consumer

sensitivityto environmentalissuesmay further

motivate firmsto take proactive stepstoward the

adoption of a PES from entrepreneurialorientation.

According to stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984),

the strategic choicesadopted by firmsdepend on

institutionalpressuresand the influence ofimpor-

tantstakeholders(Oliver,1991).More specifically,

Mitchell et al. (1997) showed that stakeholder power

legitimacy,and urgency affecta manager’sattitude

toward stakeholder pressures and requests. This wa

confirmed by Henriques and Sadorsky (1999) who

affirmed that managers in environmentally proactive

firms were more committed to a proactive environ-

mental posture than those in environmentally reacti

firms.

Neo-institutionaltheoristshaveproposedthat

firms,through proactivemoves,may meettheir

stakeholders’expectationsand enhance legitimacy,

therebyobtainingaccessto the scarceresources

neededto surviveand succeed(DiMaggio and

Powell, 1983). For example, Majumdar and Marcus

(2001)showed thatwhen managersachieve a bal-

ancebetween theirdiscretion and governmental

regulatory policies,they may enjoy entrepreneur-

ship, be creative, conduct R & D, and even develop

new technologies,all of which are important

resources for the development of a PES.

Our argumentis also consistentwith legitimacy

theory because a central tenet of this theory is a soc

contractthatimpliesthata company’ssurvivalis

dependenton the extentto which the company

operates within the bounds and norms of the macro

environment,including society,and isviewed as

constructive and performing desirable actions (Brow

and Deegan,1998,p. 22). As a consequence,a

company needsto demonstrate thatits actionsare

legitimate and its behaviors resemble good corporat

citizenship (e.g.,Berman etal., 1999;Miles and

Covin, 2000).

Taking the above into account,we positthat

there is a need to examine the interaction between

the RBV perspective and institutional(legitimacy)

285Interactive Effect ofInternaland ExternalFactors on PES

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

theory.According to ourconceptualframework,

this would involveexamininghow institutional

pressures such as intensity of government regulations

moderate the influence ofentrepreneurialorienta-

tion on a PES. More specifically, we argue that the

interaction effectbetween entrepreneurialorienta-

tion and intensity ofgovernmentregulation on a

PES will be positive. This is because firms operate in

a macro environmentwhere governmentscontrol,

sanction,and withhold important resources that are

likely to influence a firm’s adoption of a PES. When

firms competein a marketwheregovernment

involvement,interest,and regulationsregarding

environmentalissuesare heightened,thereis an

elevated expectation for top management to comply,

as this is the norm, with government demands. As a

consequence, in such a context, the implementation

of an entrepreneurialorientation willbe related

positively to the adoption of a pollution-prevention

strategy by top management.Thus,we offerthe

following interaction hypothesis.

H2: The interaction effect between entrepreneurial

orientation and intensity ofgovernmentreg-

ulations willbe related positively to a PES.

Moderating role ofconsumer sensitivity to natural

environmentalissues

Next, we turn our attention to the moderating role

of consumer sensitivity to naturalenvironmentalis-

sues. When consumers are sensitive to and involved

with naturalenvironmentalissues,they favorand

react positively to firms that attempt to develop and

initiate innovative and proactive methods that pre-

serve the naturalenvironment(e.g.,Garrett,1987;

Schwepkerand Cornwell,1991).As consumer

sensitivity to naturalenvironmentalissuesincrease,

consumerscome to expectfirmsto develop inno-

vative waysto interactwith the naturalenviron-

ment. As a consequence, in such a context, as firms

engage in entrepreneurial activities, firms will realize

more PES.When consumersexertpressure,firms

are more prone to adopt a PES for a given levelof

entrepreneurial orientation because the adoption of a

PES is consistentwith the voice of consumers

(Ogden and Watson,1999).We positthatwhen

there is fit between entrepreneurialorientation and

consumer sensitivity to natural environmental issues

it is likely thata firm’sentrepreneurialorientation

will be related positively to a PES.Therefore,we

hypothesize that:

H3: The interaction effect between entrepreneurial

orientation and customers’sensitivity to envi-

ronmentalissues willbe related positively to a

PES.

Proactive environmentalstrategy and firm’s

performance

Firms that implement a PES will be more innovative,

entrepreneurially oriented,technologically sophis-

ticated,and socially conscious,which makessuch

organizations distinct in the eyes of customers (Port

and van der Linde,1995).Accordingly,these orga-

nizationswill be able to preemptthe marketfrom

their competitors and enjoy a first mover advantage

statusby sending a strong signalabouttheir com-

mitmentto the naturalenvironment.Because such

firmsinvestin pollution prevention asopposed to

controlprograms,they willengage in continuous

total quality environment management programs th

enable them to be more cost efficient by minimizing

the need to invest in expensive end-of-pipe capital

intensive investments (Hart,1995;Hart and Ahuja,

1996). In addition, because the implementation of a

PES improves the image, reputation, and eventually

the legitimacy of a firm, it willincrease the positive

view of the firm as a good corporate citizen (Menon

and Menon,1997).We contend thatby imple-

menting a PES,corporate citizenship willbe en-

hanced,which will lead to astrongercorporate

reputation (Berman et al., 1999). In fact, Rondinelli

and Berry (2000) argue that corporate environmenta

citizenship is critical for sustainable development.

As a consequence, firms that pursue a PES will be

perceived as differentiated in the eyes of customers

Through differentiation, firms with a PES will be able

to create more opportunities,and hence generate

greater business growth. A PES can be used to reig-

nite, spark. or fuel firms into a new market space, th

providing the catalystfor salesand profitgrowth.

Owing to a growing environmentalconsciousness

286 Bulent Menguc et al.

this would involveexamininghow institutional

pressures such as intensity of government regulations

moderate the influence ofentrepreneurialorienta-

tion on a PES. More specifically, we argue that the

interaction effectbetween entrepreneurialorienta-

tion and intensity ofgovernmentregulation on a

PES will be positive. This is because firms operate in

a macro environmentwhere governmentscontrol,

sanction,and withhold important resources that are

likely to influence a firm’s adoption of a PES. When

firms competein a marketwheregovernment

involvement,interest,and regulationsregarding

environmentalissuesare heightened,thereis an

elevated expectation for top management to comply,

as this is the norm, with government demands. As a

consequence, in such a context, the implementation

of an entrepreneurialorientation willbe related

positively to the adoption of a pollution-prevention

strategy by top management.Thus,we offerthe

following interaction hypothesis.

H2: The interaction effect between entrepreneurial

orientation and intensity ofgovernmentreg-

ulations willbe related positively to a PES.

Moderating role ofconsumer sensitivity to natural

environmentalissues

Next, we turn our attention to the moderating role

of consumer sensitivity to naturalenvironmentalis-

sues. When consumers are sensitive to and involved

with naturalenvironmentalissues,they favorand

react positively to firms that attempt to develop and

initiate innovative and proactive methods that pre-

serve the naturalenvironment(e.g.,Garrett,1987;

Schwepkerand Cornwell,1991).As consumer

sensitivity to naturalenvironmentalissuesincrease,

consumerscome to expectfirmsto develop inno-

vative waysto interactwith the naturalenviron-

ment. As a consequence, in such a context, as firms

engage in entrepreneurial activities, firms will realize

more PES.When consumersexertpressure,firms

are more prone to adopt a PES for a given levelof

entrepreneurial orientation because the adoption of a

PES is consistentwith the voice of consumers

(Ogden and Watson,1999).We positthatwhen

there is fit between entrepreneurialorientation and

consumer sensitivity to natural environmental issues

it is likely thata firm’sentrepreneurialorientation

will be related positively to a PES.Therefore,we

hypothesize that:

H3: The interaction effect between entrepreneurial

orientation and customers’sensitivity to envi-

ronmentalissues willbe related positively to a

PES.

Proactive environmentalstrategy and firm’s

performance

Firms that implement a PES will be more innovative,

entrepreneurially oriented,technologically sophis-

ticated,and socially conscious,which makessuch

organizations distinct in the eyes of customers (Port

and van der Linde,1995).Accordingly,these orga-

nizationswill be able to preemptthe marketfrom

their competitors and enjoy a first mover advantage

statusby sending a strong signalabouttheir com-

mitmentto the naturalenvironment.Because such

firmsinvestin pollution prevention asopposed to

controlprograms,they willengage in continuous

total quality environment management programs th

enable them to be more cost efficient by minimizing

the need to invest in expensive end-of-pipe capital

intensive investments (Hart,1995;Hart and Ahuja,

1996). In addition, because the implementation of a

PES improves the image, reputation, and eventually

the legitimacy of a firm, it willincrease the positive

view of the firm as a good corporate citizen (Menon

and Menon,1997).We contend thatby imple-

menting a PES,corporate citizenship willbe en-

hanced,which will lead to astrongercorporate

reputation (Berman et al., 1999). In fact, Rondinelli

and Berry (2000) argue that corporate environmenta

citizenship is critical for sustainable development.

As a consequence, firms that pursue a PES will be

perceived as differentiated in the eyes of customers

Through differentiation, firms with a PES will be able

to create more opportunities,and hence generate

greater business growth. A PES can be used to reig-

nite, spark. or fuel firms into a new market space, th

providing the catalystfor salesand profitgrowth.

Owing to a growing environmentalconsciousness

286 Bulent Menguc et al.

and demandsfrom variousstakeholderssuch as

customers,interestgroups,government,and the

media, a PES can be expected to contribute to sales

growth and profit growth. Increased sales growth will

be realized as environmentally friendly products are

well received.That is, implementing aPES will

generate additional sales in areas that are untapped and

where competition isscarce.Further,a PES will

motivate firmsto produce high margin products

adopting cutting-edge technology which can en-

hance profit growth. Through a PES, firms can realize

improved streams of cash flow as a PES will be able to

function in a rent-generating role. Thus, we offer the

following hypothesis regarding the performance im-

pact of a PES:

H4: A proactiveenvironmentalstrategy willbe

positively related to (a)salesgrowth and (b)

profit growth.

Finally,we do nothypothesize a directeffect on a

PES from the externalperspective (i.e.,intensity of

governmentregulation and consumer sensitivity to

naturalenvironmentalissues)because according to

our conceptualmodel,the externalperspective is a

moderatorthateitherstrengthensor weakensthe

effectof entrepreneurialorientationon a PES.

However, as we shall show subsequently, we include

the externalperspective on a PES for modelspeci-

fication purposes and report its effect.

Research method

Questionnaire development and measures

As stated earlier, previous studies have employed the

internal(i.e., resource-based)and external(i.e.,

legitimacy-based) perspectives to explain the extent

of a firm’s implementation of PES. However, there

is a lack ofsystematic research thatinvestigates the

interactive effect of the two perspectives. In order to

fill this gap in the literature, we decided to devise a

survey instrumentthatwould enable usto testthe

conceptualmodeldeveloped in thisstudy.More

specifically, this survey instrument was meant to test

how customers’sensitivity to environmentalissues

and the intensity ofgovernmentregulationsmod-

erate the effectof entrepreneurialorientation on a

PES. The survey instrument also helped us measure

the performance outcomes of a PES in terms of sales

and profit growths.

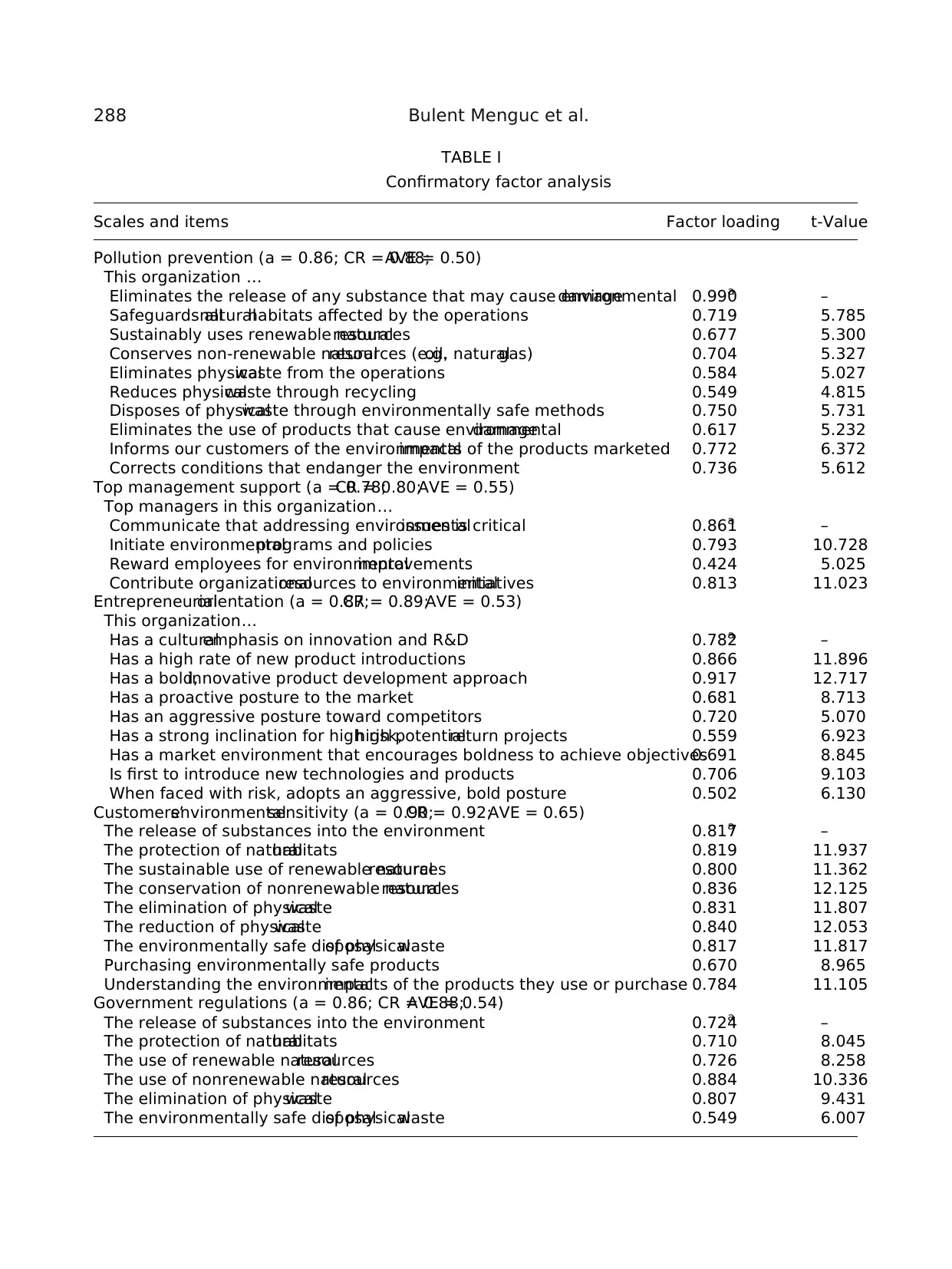

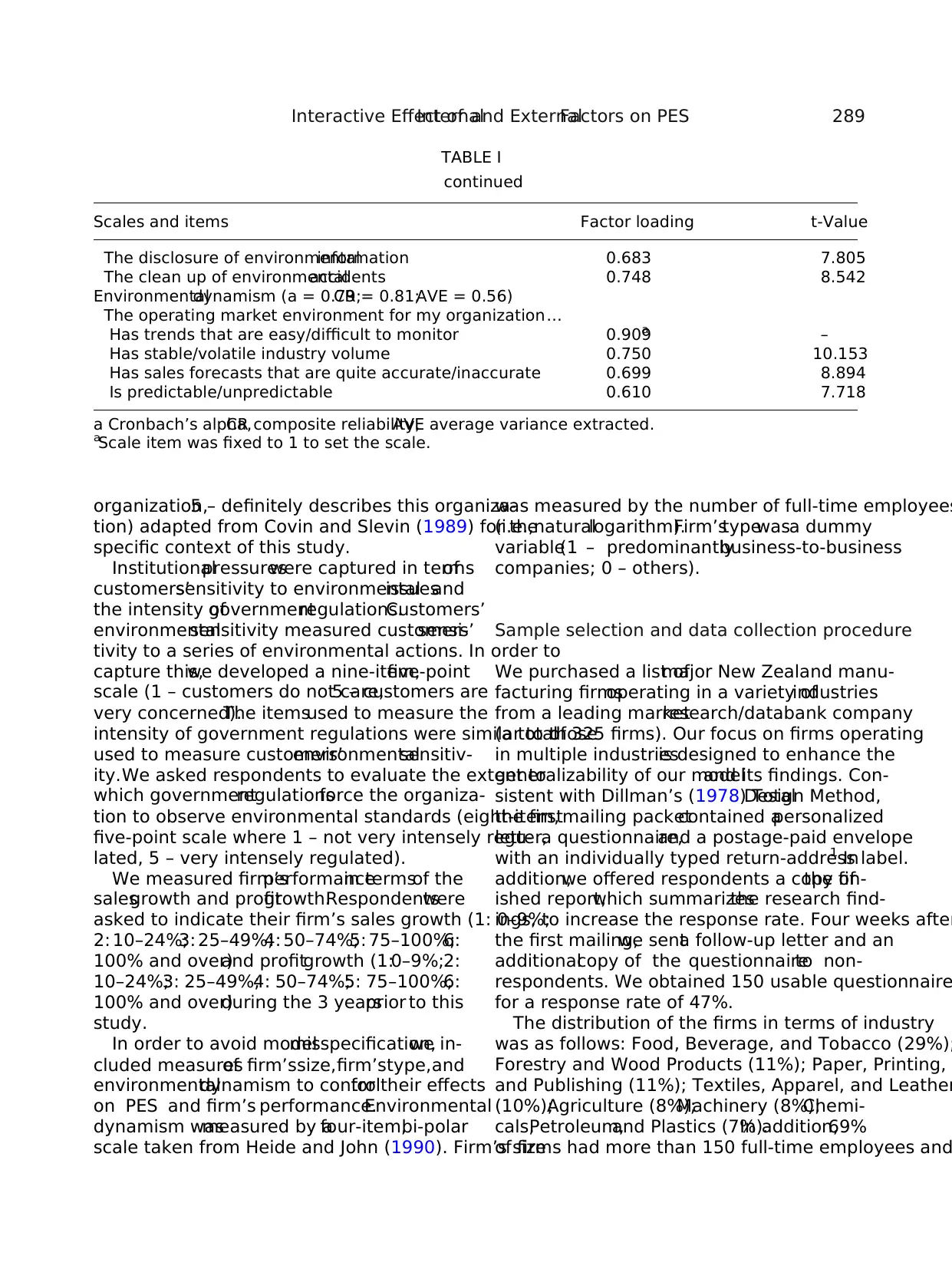

The survey instrument was developed as follows:

First, we contacted a random selection of 15 CEOs

and/or key managers. We mailed a draft form of the

survey questionnaire and asked them to identify the

scale itemsthey considered awkward and/ornot

applicable. They evaluated every scale item in terms