Quantifying Vegetation Effects on Near-Road Air Quality

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/21

|9

|8805

|202

Report

AI Summary

This report, based on a study conducted by Cornell University, investigates the effects of vegetation on near-road air quality, specifically focusing on the dispersion of PM2.5. The research involved brief field campaigns in Queens, NY, near major highways, where high-resolution measurements of PM2.5 were taken along transects. The study found that the presence of trees can influence local pollution concentrations, sometimes increasing them due to aerodynamic effects that reduce dispersion. The report highlights that the polydisperse PM2.5 class poorly represented the behavior of discrete classes. The study also compared transects across lawns with and without trees, observing fewer spikes in PM2.5 concentrations but a more gradual decrease downwind of trees, indicating recirculation and reduced dispersion. The findings emphasize that simply planting trees might not always improve air quality, especially if the goal is to protect vulnerable populations. The report concludes by advocating for a mechanistic approach based on fluid dynamics to better understand and manage air quality in urban environments.

Quantifying the effect of vegetation on near-road air quality using

brief campaigns

Zheming Tonga

, Thomas H.Whitlow b, * , Patrick F.MacRaeb

, Andrew J. Landersc

,

Yoshiki Haradab

a Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering,Cornell University,Gruman Hall,Ithaca,NY,USA

b Section of Horticulture,School of Integrative Plant Science,Cornell University,Room 23 Plant Science Building,Ithaca,NY 14853,USA

c New York State Agricultural Experiment Station,630 West North Street,Geneva,NY 14456,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 18 August 2014

Received in revised form

18 February 2015

Accepted 20 February 2015

Available online 20 March 2015

Keywords:

Near-road air pollution

Trees

Dispersion

Aerodynamics

PM 2.5

a b s t r a c t

Many reports of trees'impacts on urban air quality neglect pattern and process at the landscape scale.

Here,we describe brief campaigns to quantify the effect of trees on the dispersion of airborne particu-

lates using high time resolution measurements along short transects away from roads.Campaigns near

major highways in Queens,NY showed frequent,stochastic spikes in PM2.5.The polydisperse PM2.5

class poorly represented the behavior of discrete classes.A transect across a lawn with trees had fewer

spikes in PM2.5 concentration but decreased more gradually than a transect crossing a treeless lawn. Th

coincided with decreased Turbulence Kinetic Energy downwind of trees, indicating recirculation, longer

residence times and decreased dispersion.Simply planting trees can increase localpollution concen-

trations, which is a special concern if the intent is to protect vulnerable populations.Emphasizing

deposition to leaf surfaces obscures the dominant impact of aerodynamics on local concentration.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

There is a general consensus that proximity to major highways

increases the risk of adverse health effects caused by exposure to air

pollution (HEI, 2010). Roadside barriers, including vegetation, have

been shown to alter the dispersion of traffic emissions.If the

vegetative barriers consistently lower ground-levelair pollution

concentrationsin the near-road environment, they may be a

practical tool for reducing human exposure to air pollution along

populated roadways.

It is widely reported that trees intercept airborne particles

which are subsequently removed from the canopy by re-

suspension,by rain and leaf abscission (Dochinger,1980; Freer-

Smith et al., 2004; Nowak, 2002; Nowak et al., 2013). Using

empirical estimates of deposition velocities, these reports estimate

the total particulate removed by trees (typically PM10) at either city

wide or local scales.Calculations like these are often used to

advocate tree planting policieslike the numerous million-tree

programs across the US.However laudable these programs are,

the approach ignores the effects of distance from source and the

local aerodynamics around trees,how these affect dispersion and

ultimately local PM concentration, and provide no guidance for the

rational design of landscapes to improve local air quality.For this

purpose, a mechanistic approach based on fluid dynamics of

different particle sizes and the local turbulent flow field caused by

road-canopy configurations is needed.

Aerosol science has long known that particle dry deposition

velocity varies as a function of particle size,and ranges over three

orders of magnitude (Sehmel,1980; Seinfeld and Pandis,2006;

Slinn et al., 1978).This is because particles <0.001mm behave

more like gases, diffusing along concentration gradients to deposit

on surfaces,unlike particles >10mm whose deposition rates de-

pends on inertial impaction and gravitationalsettling.The local

turbulent flow field also plays a significant role in particle disper-

sion.A tree canopy consists of numerous elements such as leaves,

branches and trunks.When these elements interact with airflow,

the flow momentum is absorbed by both form and skin-friction

drag on the canopy,reducing mean flow velocity (Raupach and

Thom,1981).Larger scale turbulent eddies introduced by traffic

and the background atmosphere are broken down to smallscale

eddies by a tree canopy,causing a recirculation zone behind the

vegetation with elevated concentrations (Steffens et al., 2012; Tong

et al.,2011; Wang and Zhang,2009).

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: thw2@cornell.edu (T.H.Whitlow).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Environmental Pollution

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / e n v p o l

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.02.026

0269-7491/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149

brief campaigns

Zheming Tonga

, Thomas H.Whitlow b, * , Patrick F.MacRaeb

, Andrew J. Landersc

,

Yoshiki Haradab

a Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering,Cornell University,Gruman Hall,Ithaca,NY,USA

b Section of Horticulture,School of Integrative Plant Science,Cornell University,Room 23 Plant Science Building,Ithaca,NY 14853,USA

c New York State Agricultural Experiment Station,630 West North Street,Geneva,NY 14456,USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 18 August 2014

Received in revised form

18 February 2015

Accepted 20 February 2015

Available online 20 March 2015

Keywords:

Near-road air pollution

Trees

Dispersion

Aerodynamics

PM 2.5

a b s t r a c t

Many reports of trees'impacts on urban air quality neglect pattern and process at the landscape scale.

Here,we describe brief campaigns to quantify the effect of trees on the dispersion of airborne particu-

lates using high time resolution measurements along short transects away from roads.Campaigns near

major highways in Queens,NY showed frequent,stochastic spikes in PM2.5.The polydisperse PM2.5

class poorly represented the behavior of discrete classes.A transect across a lawn with trees had fewer

spikes in PM2.5 concentration but decreased more gradually than a transect crossing a treeless lawn. Th

coincided with decreased Turbulence Kinetic Energy downwind of trees, indicating recirculation, longer

residence times and decreased dispersion.Simply planting trees can increase localpollution concen-

trations, which is a special concern if the intent is to protect vulnerable populations.Emphasizing

deposition to leaf surfaces obscures the dominant impact of aerodynamics on local concentration.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

There is a general consensus that proximity to major highways

increases the risk of adverse health effects caused by exposure to air

pollution (HEI, 2010). Roadside barriers, including vegetation, have

been shown to alter the dispersion of traffic emissions.If the

vegetative barriers consistently lower ground-levelair pollution

concentrationsin the near-road environment, they may be a

practical tool for reducing human exposure to air pollution along

populated roadways.

It is widely reported that trees intercept airborne particles

which are subsequently removed from the canopy by re-

suspension,by rain and leaf abscission (Dochinger,1980; Freer-

Smith et al., 2004; Nowak, 2002; Nowak et al., 2013). Using

empirical estimates of deposition velocities, these reports estimate

the total particulate removed by trees (typically PM10) at either city

wide or local scales.Calculations like these are often used to

advocate tree planting policieslike the numerous million-tree

programs across the US.However laudable these programs are,

the approach ignores the effects of distance from source and the

local aerodynamics around trees,how these affect dispersion and

ultimately local PM concentration, and provide no guidance for the

rational design of landscapes to improve local air quality.For this

purpose, a mechanistic approach based on fluid dynamics of

different particle sizes and the local turbulent flow field caused by

road-canopy configurations is needed.

Aerosol science has long known that particle dry deposition

velocity varies as a function of particle size,and ranges over three

orders of magnitude (Sehmel,1980; Seinfeld and Pandis,2006;

Slinn et al., 1978).This is because particles <0.001mm behave

more like gases, diffusing along concentration gradients to deposit

on surfaces,unlike particles >10mm whose deposition rates de-

pends on inertial impaction and gravitationalsettling.The local

turbulent flow field also plays a significant role in particle disper-

sion.A tree canopy consists of numerous elements such as leaves,

branches and trunks.When these elements interact with airflow,

the flow momentum is absorbed by both form and skin-friction

drag on the canopy,reducing mean flow velocity (Raupach and

Thom,1981).Larger scale turbulent eddies introduced by traffic

and the background atmosphere are broken down to smallscale

eddies by a tree canopy,causing a recirculation zone behind the

vegetation with elevated concentrations (Steffens et al., 2012; Tong

et al.,2011; Wang and Zhang,2009).

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: thw2@cornell.edu (T.H.Whitlow).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Environmental Pollution

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / e n v p o l

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2015.02.026

0269-7491/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Both experimental and numerical simulation studies have

investigated the effectof vegetation on PM concentration along

roads unbounded by buildings.Brantley et al.(2014) conducted a

field assessment of the effect of roadside vegetation on near-road

black carbon and particulate matter.They found that particle

counts in the fine and coarse particle size range (0.5e10mm aero-

dynamic diameter)were unaffected by vegetation.Baldaufet al.

(2008) found that both a solid noise barrier and vegetation barrier

can reduce PM concentrations in their wakes when wind is from the

direction of the road. In general, these studies have shown decreased

concentrationsof ultrafine and coarse mode PM with limited

reduction measured for PM2.5 mass. Set€al€a et al. (2013) used passive

samplers to study the effect of urban park/forest vegetation on NO2,

anthropogenic VOCs and particle deposition in two Finnish cities.

They found that pollutant concentrations were often only slightly

lower under tree canopies than in adjacent open areas. Maher et al.

(2013) examined the impact of a line of young trees on indoor air

quality adjacent to a heavy traffic road, and a substantial reduction of

PM 10 was observed. Cavanagh et al. (2009) conducted a field study to

investigate the spatialattenuation ofPM10. Concentrations were

higher outside the forest than deep within the forest.

Other researchers have used physicalmodels in wind tunnels

and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) models to simulate the

impact of vegetative buffers on roadside plume dispersion. Gromke

and Ruck performed a wind tunnel experimenton dispersion

processesof traffic exhaust in urban street canyons with and

without street trees (Gromke, 2011; Gromke and Ruck, 2009). Trees

reduced pollutant dispersion, thereby increasing particle residence

time and concentration.In the wind tunnel, street trees caused

localized concentration increases of 50% at some locations in the

canyon compared with the treeless case. This indicates that trees in

street canyons reduce air exchange with the ambient atmosphere.

Buccolieri et al.(2009) conducted both CFD and wind tunnel ex-

periments to study the aerodynamic effects of trees on pollutant

concentration in street canyons.Both approaches showed consid-

erably greater pollutant concentration near the leeward wall and

slightly lower concentration near the windward wallwhen trees

were present.Another CFD study compared CFD modeled results

and field measurements explore the effect of a near-road vegeta-

tion barrier on ultrafine particles (Steffens et al.,2012).The CFD

model was evaluated against the roadside measurements,and a

good agreement was observed (Hagler et al., 2012). They found that

increasing leaf area density (LAD) reduced ultrafine particle con-

centration,but the response was non-linear.Pugh et al.modeled

the effect of green walls on air quality in a street canyon.Using

deposition velocities from the literature, they calculated that green

walls could cause a 40% reduction for NO2 and a 60% reduction for

PM 10 (Pugh et al.,2012).

This brief review shows that vegetation can either decrease or

increase PM concentration,depending on the road-canopy config-

uration, particle size, and local flow field. The goal of this study is to

improve our understanding of the impact of vegetation on PM2.5

transport in the near road environment. We focus on PM2.5 because

it includes the particle sizes with the lowest deposition velocities

and is more closely linked to human mortality (EPA, 2009; Seinfeld

and Pandis, 2006). By strategically deploying multiple particle

counters and sonic anemometers,this approach achieves high

spatial and temporal resolution of PM2.5 concentration in discrete

particle size classes,and corresponding turbulence data.This is a

unique addition to the existing literature that provides empirical

data for detailed landscape scale modeling.

We posed 4 initiating hypotheses:

1. PM 2.5 concentrations will be reduced below ambient downwind

of tree canopies.

2. PM 2.5 concentration will decline more sharply along a transect

occupied by trees than an open transect

3. The effect of trees on PM2.5 concentration depends on wind

direction.

4. The effect of trees on PM2.5 concentration depends on particle

size.

2. Methods

2.1.Measurement approach

We used an observational approach to conduct a series of short-

term field campaigns exploring the spatiotemporalpatterns of

particulate matterdispersion across a large urban open space

(Dominici et al.,2014).We used portable monitoring instruments

(see below) to conduct a series of brief, intensive campaigns during

a 2 week period,lasting ca. 10 h each day during daylight hours,

capturing both morning and evening rush hours.This approach

resembles that of Spengler et al.(2011) in their study of ultrafine

particles in a neighborhood adjacent to a toll plaza. In comparison

with permanently located monitors, brief campaigns can be used in

public spaces where vehicles are not allowed, make efficient use of

instrumentation and labor,allow multiple locations to be moni-

tored in real time, are suited to addressing the effectiveness of

vegetated buffers atscales relevantto engineering and human

exposure, and permit sampling where permanent samplers cannot

be secured against vandalism. Importantly, small mobile sensors do

not impact local dispersion patterns and can monitor near the

ground where human exposure would occur.The tradeoff is in

terms of generalizability of the findings over long time periods and

varying air mass conditions.

2.2. Sample location

We selected Flushing Meadows-Corona Park,a 3.63 km2 com-

plex in Queens,New York City,USA (Map is shown in the Supple-

mentary Material(SM1), and relevantfeatures are described in

Table 1). The park is surrounded by the heavily trafficked Van Wyck

and Long Island Expressways (LIE),allowing us to select sample

locations to control for prevailing wind direction on any given

sampling day.Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) is 84,601 vehi-

cles/day on the Van Wyck and 138,406 vehicles/day on the LIE. Over

a 2-week mid-summer period when trees were in full leaf, we

sampled at three locations in the park when weather and wind

direction were suitable for testing our hypotheses.None of these

sites was deliberately designed to modify airflow or capture par-

ticles, yet each represents a landscape common in urban centers in

the eastern US, consisting of trees, lawns, and playing fields near a

highway. The park is separated from the highway right-of-way by a

continuous 2.4 m high chain link fence deliberately kept free of

vegetation, thus having essentially no impact on wind and particle

movement at the scale of our measurements (Details of the vege-

tation at each site are presented in Table 1 and SM2).

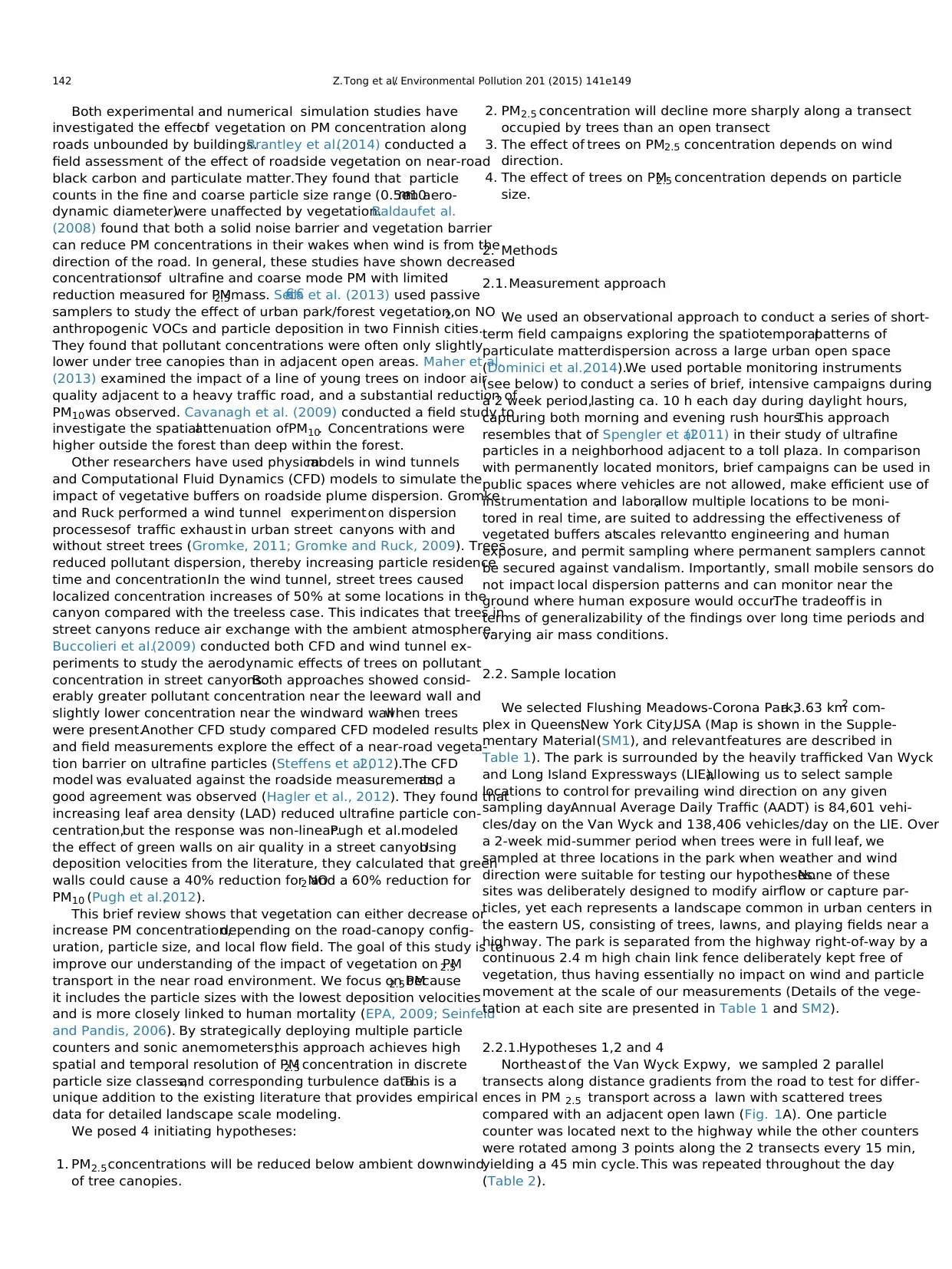

2.2.1.Hypotheses 1,2 and 4

Northeast of the Van Wyck Expwy, we sampled 2 parallel

transects along distance gradients from the road to test for differ-

ences in PM 2.5 transport across a lawn with scattered trees

compared with an adjacent open lawn (Fig. 1A). One particle

counter was located next to the highway while the other counters

were rotated among 3 points along the 2 transects every 15 min,

yielding a 45 min cycle. This was repeated throughout the day

(Table 2).

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149142

investigated the effectof vegetation on PM concentration along

roads unbounded by buildings.Brantley et al.(2014) conducted a

field assessment of the effect of roadside vegetation on near-road

black carbon and particulate matter.They found that particle

counts in the fine and coarse particle size range (0.5e10mm aero-

dynamic diameter)were unaffected by vegetation.Baldaufet al.

(2008) found that both a solid noise barrier and vegetation barrier

can reduce PM concentrations in their wakes when wind is from the

direction of the road. In general, these studies have shown decreased

concentrationsof ultrafine and coarse mode PM with limited

reduction measured for PM2.5 mass. Set€al€a et al. (2013) used passive

samplers to study the effect of urban park/forest vegetation on NO2,

anthropogenic VOCs and particle deposition in two Finnish cities.

They found that pollutant concentrations were often only slightly

lower under tree canopies than in adjacent open areas. Maher et al.

(2013) examined the impact of a line of young trees on indoor air

quality adjacent to a heavy traffic road, and a substantial reduction of

PM 10 was observed. Cavanagh et al. (2009) conducted a field study to

investigate the spatialattenuation ofPM10. Concentrations were

higher outside the forest than deep within the forest.

Other researchers have used physicalmodels in wind tunnels

and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) models to simulate the

impact of vegetative buffers on roadside plume dispersion. Gromke

and Ruck performed a wind tunnel experimenton dispersion

processesof traffic exhaust in urban street canyons with and

without street trees (Gromke, 2011; Gromke and Ruck, 2009). Trees

reduced pollutant dispersion, thereby increasing particle residence

time and concentration.In the wind tunnel, street trees caused

localized concentration increases of 50% at some locations in the

canyon compared with the treeless case. This indicates that trees in

street canyons reduce air exchange with the ambient atmosphere.

Buccolieri et al.(2009) conducted both CFD and wind tunnel ex-

periments to study the aerodynamic effects of trees on pollutant

concentration in street canyons.Both approaches showed consid-

erably greater pollutant concentration near the leeward wall and

slightly lower concentration near the windward wallwhen trees

were present.Another CFD study compared CFD modeled results

and field measurements explore the effect of a near-road vegeta-

tion barrier on ultrafine particles (Steffens et al.,2012).The CFD

model was evaluated against the roadside measurements,and a

good agreement was observed (Hagler et al., 2012). They found that

increasing leaf area density (LAD) reduced ultrafine particle con-

centration,but the response was non-linear.Pugh et al.modeled

the effect of green walls on air quality in a street canyon.Using

deposition velocities from the literature, they calculated that green

walls could cause a 40% reduction for NO2 and a 60% reduction for

PM 10 (Pugh et al.,2012).

This brief review shows that vegetation can either decrease or

increase PM concentration,depending on the road-canopy config-

uration, particle size, and local flow field. The goal of this study is to

improve our understanding of the impact of vegetation on PM2.5

transport in the near road environment. We focus on PM2.5 because

it includes the particle sizes with the lowest deposition velocities

and is more closely linked to human mortality (EPA, 2009; Seinfeld

and Pandis, 2006). By strategically deploying multiple particle

counters and sonic anemometers,this approach achieves high

spatial and temporal resolution of PM2.5 concentration in discrete

particle size classes,and corresponding turbulence data.This is a

unique addition to the existing literature that provides empirical

data for detailed landscape scale modeling.

We posed 4 initiating hypotheses:

1. PM 2.5 concentrations will be reduced below ambient downwind

of tree canopies.

2. PM 2.5 concentration will decline more sharply along a transect

occupied by trees than an open transect

3. The effect of trees on PM2.5 concentration depends on wind

direction.

4. The effect of trees on PM2.5 concentration depends on particle

size.

2. Methods

2.1.Measurement approach

We used an observational approach to conduct a series of short-

term field campaigns exploring the spatiotemporalpatterns of

particulate matterdispersion across a large urban open space

(Dominici et al.,2014).We used portable monitoring instruments

(see below) to conduct a series of brief, intensive campaigns during

a 2 week period,lasting ca. 10 h each day during daylight hours,

capturing both morning and evening rush hours.This approach

resembles that of Spengler et al.(2011) in their study of ultrafine

particles in a neighborhood adjacent to a toll plaza. In comparison

with permanently located monitors, brief campaigns can be used in

public spaces where vehicles are not allowed, make efficient use of

instrumentation and labor,allow multiple locations to be moni-

tored in real time, are suited to addressing the effectiveness of

vegetated buffers atscales relevantto engineering and human

exposure, and permit sampling where permanent samplers cannot

be secured against vandalism. Importantly, small mobile sensors do

not impact local dispersion patterns and can monitor near the

ground where human exposure would occur.The tradeoff is in

terms of generalizability of the findings over long time periods and

varying air mass conditions.

2.2. Sample location

We selected Flushing Meadows-Corona Park,a 3.63 km2 com-

plex in Queens,New York City,USA (Map is shown in the Supple-

mentary Material(SM1), and relevantfeatures are described in

Table 1). The park is surrounded by the heavily trafficked Van Wyck

and Long Island Expressways (LIE),allowing us to select sample

locations to control for prevailing wind direction on any given

sampling day.Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT) is 84,601 vehi-

cles/day on the Van Wyck and 138,406 vehicles/day on the LIE. Over

a 2-week mid-summer period when trees were in full leaf, we

sampled at three locations in the park when weather and wind

direction were suitable for testing our hypotheses.None of these

sites was deliberately designed to modify airflow or capture par-

ticles, yet each represents a landscape common in urban centers in

the eastern US, consisting of trees, lawns, and playing fields near a

highway. The park is separated from the highway right-of-way by a

continuous 2.4 m high chain link fence deliberately kept free of

vegetation, thus having essentially no impact on wind and particle

movement at the scale of our measurements (Details of the vege-

tation at each site are presented in Table 1 and SM2).

2.2.1.Hypotheses 1,2 and 4

Northeast of the Van Wyck Expwy, we sampled 2 parallel

transects along distance gradients from the road to test for differ-

ences in PM 2.5 transport across a lawn with scattered trees

compared with an adjacent open lawn (Fig. 1A). One particle

counter was located next to the highway while the other counters

were rotated among 3 points along the 2 transects every 15 min,

yielding a 45 min cycle. This was repeated throughout the day

(Table 2).

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149142

2.2.2.Hypotheses 1 and 4

The 2 LIE sites were selected because the landscape on both

sides of the highway has roadside trees,open lawn and sports

fields, and in the case of LIE North, a patch of closed canopy forest.

On the south side of LIE (Fig. 1B), we located particle counters at 3

fixed points: at the highway edge, 12 m downwind of a line of trees,

and 52 m downwind of the trees in an athletic field. Measurements

were fully synchronized in time.

2.2.3.Hypotheses 3

North of the LIE, we sampled at 3 static locations: adjacent to the

highway shoulder,in a grassy field and under a forest canopy

(Fig. 1C). On the day we sampled, wind was from the north, upwind

of the highway. The three sites are referred to as Van Wyck East, LIE

South, and LIE North in the text.

2.3. Instrumentation

2.3.1.Particle counters

We measured atmospheric particulates using 3 Grimm Aerosol

Spectrometers (Model1.108) equipped with isokinetic probes to

reduce the effect of variation in wind speed. We monitored 15 size

classes between 0.3 and 20mm every 6 s. This approximates a

human resting inhalation rate and also allows us to observe con-

ditions corresponding to spikes in PM 2.5 concentration. In-

struments had been factory calibrated just prior to the summer

campaign. In addition, all 3 instruments were co-located for 60 min

each sampling day and readings from each instrument were

regressed against their average.These empiricalequations were

used to adjust readings to compensate for small variations among

the instruments.We approximated fine particulate matter (PM2.5)

as sum of all sizes from 0.3mm to 3.0 mm, and particle counts are

converted to mass by assuming that the particles are spherical and

using the conversion factor 1.4 g/cm3 (Armbruster et al., 1984;

Murakami et al.,2005).This underestimated the regulatory defi-

nition of PM2.5 because it excludes particles below the detection

Table 1

Site description; a) Measurements were taken on days when weather permitted and wind direction was appropriate for testing the 4 hypotheses; b) The unit of latitude

longitude is in decimal degrees. c) Canopy porosity was determined from hemispherical images taken beneath the canopy. More details are provided in the Supplemen

Material (SM2).d) Tree cover percentage was measured with a line intercept method from aerial photographs.e) Grass,bare soil,and pavement cover were measured by

quadrat method.Percentage of road pavement is not presented in this table,but can be found in SM2.A list of tree species is also provided in SM2.

Datea Latitudeb Longitudeb Porosityc % Treesd % Bare soil % Grasse

Van Wyck East Jun 7,2011 40.723 73.838 15.7% 44.1%(w/trees)

0%(no trees)

10.5%(w/trees)

3.5%(no trees)

89.5%(w/trees)

96.5%(no trees)

LIE South Jul 13/14/15,2011 40.741 73.841 9.8% 4.3% 3.1% 66.7%

LIE North Jul 12,2011 40.743 73.841 21.9% 82.5%(w/trees)

6.3%(no trees)

17.0%(w/trees)

22.5%(no trees)

71.9%(w/trees)

64.7%(no trees)

Fig. 1. Details of the sample points at the 3 sites. A) Van Wyck East,stations and 2,3,4

represent the vegetated transect,and 5, 6, 7 represent the open transect.Station 1

beside the road serves as a common reference point for both transects; B) LIE (Long

Island Expressway) South; C) LIE North; Wind roses are based on daily on site mea-

surements.The numbers on each figure indicate the sampling points.In the text,the

sites are referred to as Van Wyck East,LIE South,and LIE North.

Table 2

Average concentration and standard deviation (shown in parentheses) of PM2.5 at

various sampling stations for Van Wyck East and LIE South; Locations are indicated

by distances from the road. The averaging period for Van Wyck East site is the same

as the one used in the decay curves. The averaging period for LIE South is from 12:10

to 1:30 PM where the traffic and wind condition is most steady.

Open transect at Van Wyck EastRoadside 10 m 23 m 40 m

Average concentration [mg/m3

] 4.92(1.84) 3.90(1.33) 3.81(1.19) 3.75(1.27)

Vegetated transect at Van

Wyck East

Roadside 7 m 15 m 51 m

Average concentration [mg/m3

] 4.92(1.84) 4.36(0.94) 4.46(1.11) 4.17(0.81)

Vegetated Transect at LIE SouthRoadside 12 m 52 m

Average concentration [mg/m3

] 1.96(0.84) 1.77(0.74) 1.65(0.64)

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149 143

The 2 LIE sites were selected because the landscape on both

sides of the highway has roadside trees,open lawn and sports

fields, and in the case of LIE North, a patch of closed canopy forest.

On the south side of LIE (Fig. 1B), we located particle counters at 3

fixed points: at the highway edge, 12 m downwind of a line of trees,

and 52 m downwind of the trees in an athletic field. Measurements

were fully synchronized in time.

2.2.3.Hypotheses 3

North of the LIE, we sampled at 3 static locations: adjacent to the

highway shoulder,in a grassy field and under a forest canopy

(Fig. 1C). On the day we sampled, wind was from the north, upwind

of the highway. The three sites are referred to as Van Wyck East, LIE

South, and LIE North in the text.

2.3. Instrumentation

2.3.1.Particle counters

We measured atmospheric particulates using 3 Grimm Aerosol

Spectrometers (Model1.108) equipped with isokinetic probes to

reduce the effect of variation in wind speed. We monitored 15 size

classes between 0.3 and 20mm every 6 s. This approximates a

human resting inhalation rate and also allows us to observe con-

ditions corresponding to spikes in PM 2.5 concentration. In-

struments had been factory calibrated just prior to the summer

campaign. In addition, all 3 instruments were co-located for 60 min

each sampling day and readings from each instrument were

regressed against their average.These empiricalequations were

used to adjust readings to compensate for small variations among

the instruments.We approximated fine particulate matter (PM2.5)

as sum of all sizes from 0.3mm to 3.0 mm, and particle counts are

converted to mass by assuming that the particles are spherical and

using the conversion factor 1.4 g/cm3 (Armbruster et al., 1984;

Murakami et al.,2005).This underestimated the regulatory defi-

nition of PM2.5 because it excludes particles below the detection

Table 1

Site description; a) Measurements were taken on days when weather permitted and wind direction was appropriate for testing the 4 hypotheses; b) The unit of latitude

longitude is in decimal degrees. c) Canopy porosity was determined from hemispherical images taken beneath the canopy. More details are provided in the Supplemen

Material (SM2).d) Tree cover percentage was measured with a line intercept method from aerial photographs.e) Grass,bare soil,and pavement cover were measured by

quadrat method.Percentage of road pavement is not presented in this table,but can be found in SM2.A list of tree species is also provided in SM2.

Datea Latitudeb Longitudeb Porosityc % Treesd % Bare soil % Grasse

Van Wyck East Jun 7,2011 40.723 73.838 15.7% 44.1%(w/trees)

0%(no trees)

10.5%(w/trees)

3.5%(no trees)

89.5%(w/trees)

96.5%(no trees)

LIE South Jul 13/14/15,2011 40.741 73.841 9.8% 4.3% 3.1% 66.7%

LIE North Jul 12,2011 40.743 73.841 21.9% 82.5%(w/trees)

6.3%(no trees)

17.0%(w/trees)

22.5%(no trees)

71.9%(w/trees)

64.7%(no trees)

Fig. 1. Details of the sample points at the 3 sites. A) Van Wyck East,stations and 2,3,4

represent the vegetated transect,and 5, 6, 7 represent the open transect.Station 1

beside the road serves as a common reference point for both transects; B) LIE (Long

Island Expressway) South; C) LIE North; Wind roses are based on daily on site mea-

surements.The numbers on each figure indicate the sampling points.In the text,the

sites are referred to as Van Wyck East,LIE South,and LIE North.

Table 2

Average concentration and standard deviation (shown in parentheses) of PM2.5 at

various sampling stations for Van Wyck East and LIE South; Locations are indicated

by distances from the road. The averaging period for Van Wyck East site is the same

as the one used in the decay curves. The averaging period for LIE South is from 12:10

to 1:30 PM where the traffic and wind condition is most steady.

Open transect at Van Wyck EastRoadside 10 m 23 m 40 m

Average concentration [mg/m3

] 4.92(1.84) 3.90(1.33) 3.81(1.19) 3.75(1.27)

Vegetated transect at Van

Wyck East

Roadside 7 m 15 m 51 m

Average concentration [mg/m3

] 4.92(1.84) 4.36(0.94) 4.46(1.11) 4.17(0.81)

Vegetated Transect at LIE SouthRoadside 12 m 52 m

Average concentration [mg/m3

] 1.96(0.84) 1.77(0.74) 1.65(0.64)

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149 143

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

limit of the instruments (0.3mm). It does, however,include the

range of particle diameters in so-called accumulation mode where

deposition is lowest.

2.3.2.Instantaneous wind speed/direction

We used four 3-D Gill sonic anemometers to measure the

instantaneous wind speed and direction at 1 Hz.These data were

used to generate wind roses for the sampling days and also tur-

bulent kinetic energy (TKE,see below and SM4).

2.3.3.Hemispherical canopy porosity and tree cover

Porosity is a property ofvegetation that correlates wellwith

downwind velocity, turbulence and particle deposition (Heisler and

Dewalle, 1988; Li et al.,2010; Loeffler et al., 1992; Raupach et al.,

2001).We estimated porosity to characterize the canopy density

of the trees closest to our downwind monitoring stations for each of

the three sites using a technique modified from Kenney (1987). We

used a digital camera (5 megapixel resolution; Nikon Coolpix 5700)

equipped with a fisheye lens (Nikon FC-E9) to take hemispherical

images beneath the canopy. Images were rendered in high contrast

black and white in Photoshop®

, white and black pixels were tallied,

and porosity was calculated as the % white pixels on the image. An

example of the hemisphericalimage is provided in the Supple-

mentary Material.We also estimated tree cover using line in-

tercepts perpendicular to the highway and tabulating the distance

below the drip lines of the trees as a percent of the total distance

between the highway and the particle counters.

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1.Temporal variation

Koniographs,analogous to hydrographs used by hydrologists,

were used to show fine scale temporal variation in concentration at

the 6-s sampling frequency of the aerosol spectrometers (Whitlow

et al., 2011). This sampling rate approximates the human inhalation

rate, hence exposure to short term concentration spikes.

2.4.2.Return period

PM concentrations averaged over periods ranging from days-

years,while useful for regulatory purposes,eliminate fine scale

patterns that are usefulfor quantifying human exposure risk at

temporal scales relevant to daily activities,especially physical ex-

ercise. Risk is probabilistic and contingent on many environmental

factors, many of which are beyond our control. Recognizing that air

pollution events are stochastic over time, resembling flood events,

we used the Gumbel Method (Gumbel, 1941; Whitlow et al., 2011)

to calculate return period of PM2.5 events of any observed magni-

tude during each day's set of observations. Return period estimates

the magnitude of the highest concentration occurring during a

given period.This statistic is analogous to the familiar 100-year

flood, which expresses the probability ofa flood of an observed

magnitude occurring in any given year. In our usage here, the time

scale is in minutes instead of years. Further, like the 100-year flood

plain, it also characterizes a specific location.The calculation of

return period is provided in the Supplementary Material (SM3).

2.4.3.Turbulence Kinetic Energy (TKE)

We calculated TKE for time intervals when the wind direction

and speed were relatively steady for each day.The sampling fre-

quency of the sonic anemometer is 1 Hz,which though not rapid

enough to capture turbulence in the dissipation range, does capture

most of the energy containing eddies.The calculation ofTKE is

provided in the Supplementary Material (SM4).

3. Results and discussion

3.1.Experiment 1: Van Wyck East

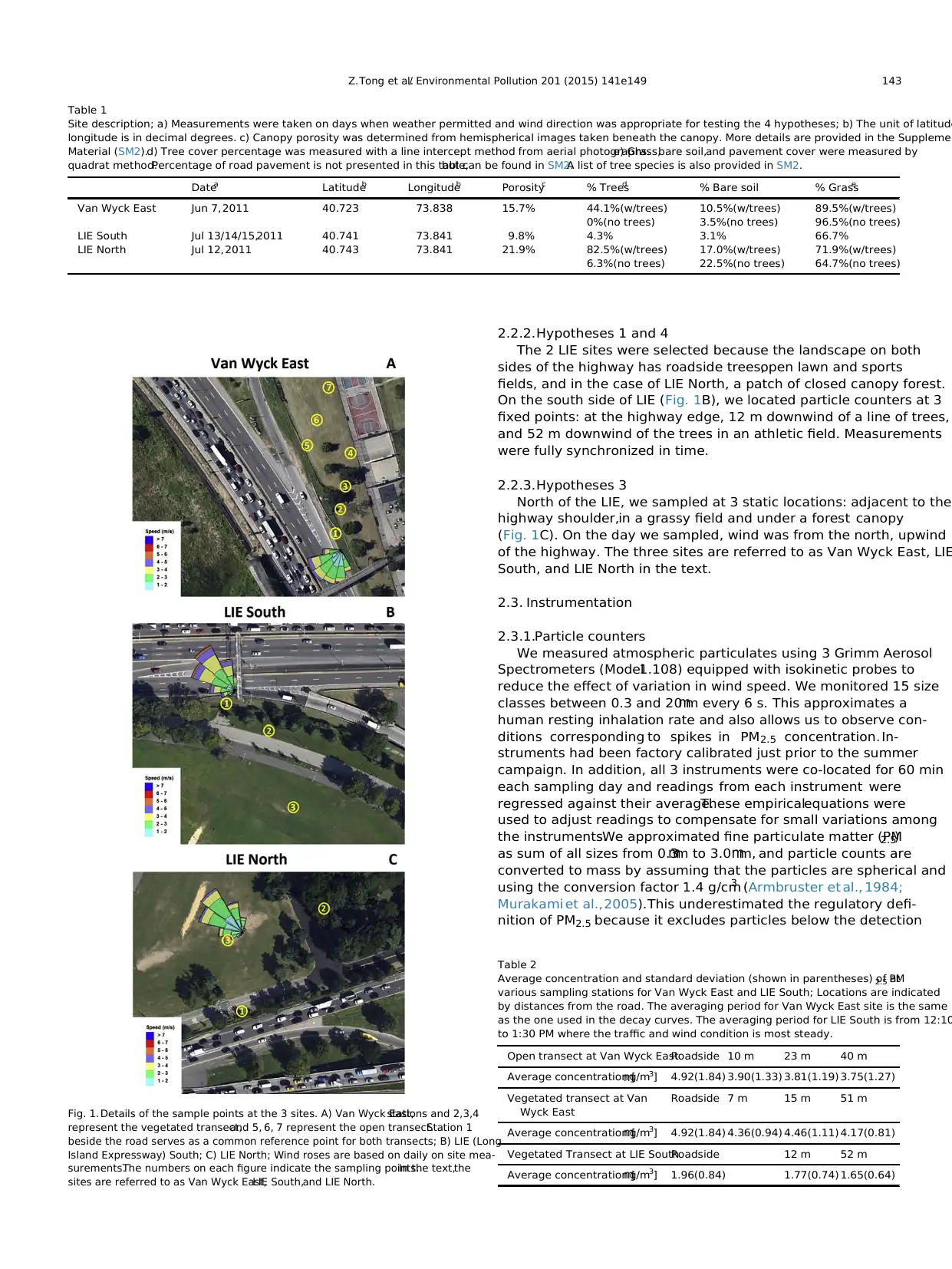

The high resolution of the 6-s sampling frequency shows the

nearly instantaneous stochastic variation of PM2.5 concentration in

the roadside environment.Sampling location 1 in Van Wyck East

site adjacent to the highway displays most variable PM2.5 concen-

tration data (Fig.2a),showing frequent spikes above background,

corresponding to passage of especially “dirty” vehicles. Because our

spectrometers cannot detect particles <0.3mm, these spikes are not

caused by primary tailpipe emissions butare either secondary

particles or particles re-suspended from the road surface and lofted

by the turbulent wakes of vehicles (Fig. 3a). Observations across the

vegetated transectshowed far less variation,higher mean con-

centrations, and large spikes in concentration were absent (Fig. 2b),

while the open transect had concentration spikes (Fig.2c).

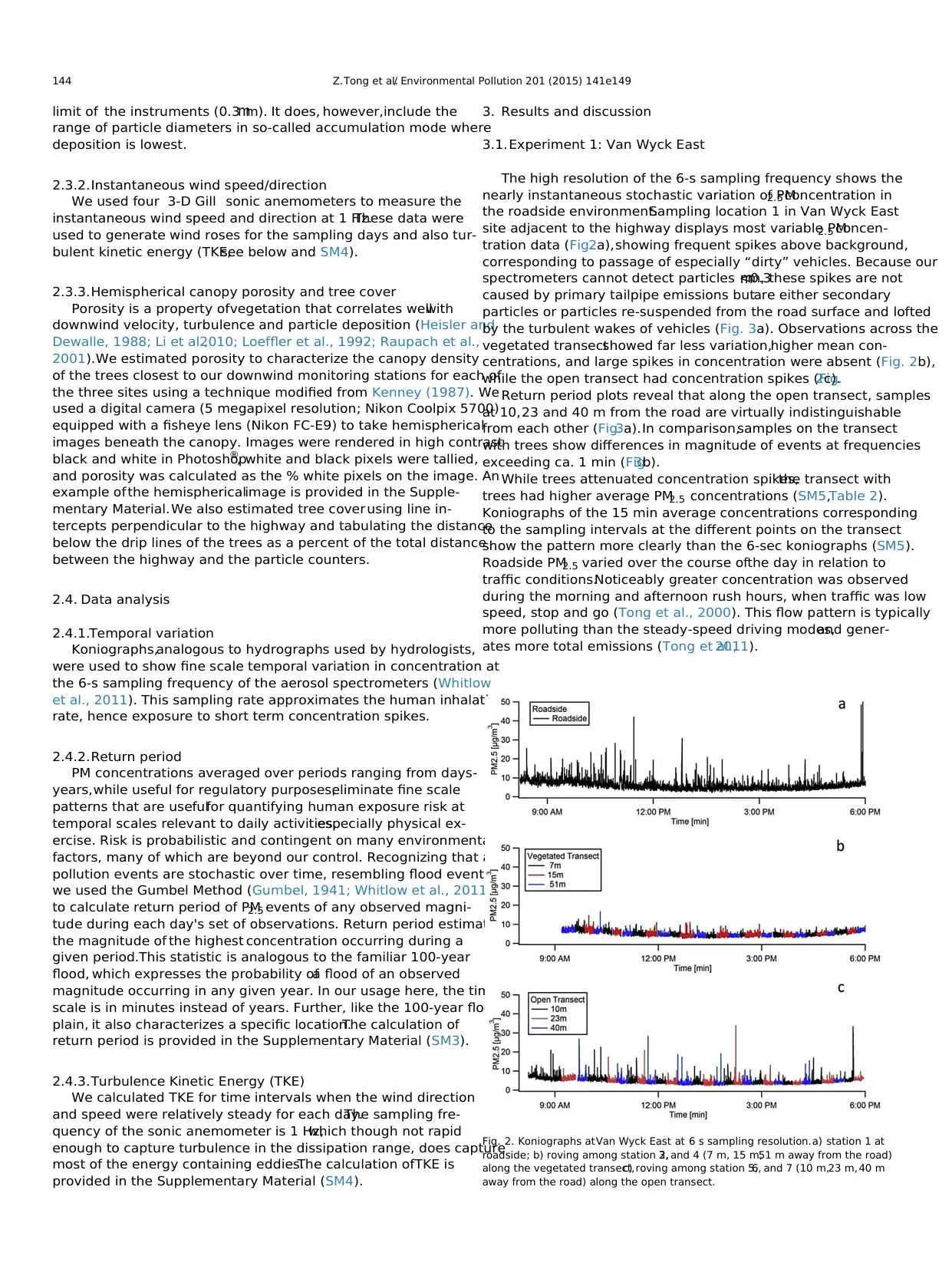

Return period plots reveal that along the open transect, samples

at 10,23 and 40 m from the road are virtually indistinguishable

from each other (Fig.3a).In comparison,samples on the transect

with trees show differences in magnitude of events at frequencies

exceeding ca. 1 min (Fig.3b).

While trees attenuated concentration spikes,the transect with

trees had higher average PM2.5 concentrations (SM5,Table 2).

Koniographs of the 15 min average concentrations corresponding

to the sampling intervals at the different points on the transect

show the pattern more clearly than the 6-sec koniographs (SM5).

Roadside PM2.5 varied over the course ofthe day in relation to

traffic conditions.Noticeably greater concentration was observed

during the morning and afternoon rush hours, when traffic was low

speed, stop and go (Tong et al., 2000). This flow pattern is typically

more polluting than the steady-speed driving modes,and gener-

ates more total emissions (Tong et al.,2011).

Fig. 2. Koniographs atVan Wyck East at 6 s sampling resolution.a) station 1 at

roadside; b) roving among station 2,3, and 4 (7 m, 15 m,51 m away from the road)

along the vegetated transect,c) roving among station 5,6, and 7 (10 m,23 m, 40 m

away from the road) along the open transect.

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149144

range of particle diameters in so-called accumulation mode where

deposition is lowest.

2.3.2.Instantaneous wind speed/direction

We used four 3-D Gill sonic anemometers to measure the

instantaneous wind speed and direction at 1 Hz.These data were

used to generate wind roses for the sampling days and also tur-

bulent kinetic energy (TKE,see below and SM4).

2.3.3.Hemispherical canopy porosity and tree cover

Porosity is a property ofvegetation that correlates wellwith

downwind velocity, turbulence and particle deposition (Heisler and

Dewalle, 1988; Li et al.,2010; Loeffler et al., 1992; Raupach et al.,

2001).We estimated porosity to characterize the canopy density

of the trees closest to our downwind monitoring stations for each of

the three sites using a technique modified from Kenney (1987). We

used a digital camera (5 megapixel resolution; Nikon Coolpix 5700)

equipped with a fisheye lens (Nikon FC-E9) to take hemispherical

images beneath the canopy. Images were rendered in high contrast

black and white in Photoshop®

, white and black pixels were tallied,

and porosity was calculated as the % white pixels on the image. An

example of the hemisphericalimage is provided in the Supple-

mentary Material.We also estimated tree cover using line in-

tercepts perpendicular to the highway and tabulating the distance

below the drip lines of the trees as a percent of the total distance

between the highway and the particle counters.

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1.Temporal variation

Koniographs,analogous to hydrographs used by hydrologists,

were used to show fine scale temporal variation in concentration at

the 6-s sampling frequency of the aerosol spectrometers (Whitlow

et al., 2011). This sampling rate approximates the human inhalation

rate, hence exposure to short term concentration spikes.

2.4.2.Return period

PM concentrations averaged over periods ranging from days-

years,while useful for regulatory purposes,eliminate fine scale

patterns that are usefulfor quantifying human exposure risk at

temporal scales relevant to daily activities,especially physical ex-

ercise. Risk is probabilistic and contingent on many environmental

factors, many of which are beyond our control. Recognizing that air

pollution events are stochastic over time, resembling flood events,

we used the Gumbel Method (Gumbel, 1941; Whitlow et al., 2011)

to calculate return period of PM2.5 events of any observed magni-

tude during each day's set of observations. Return period estimates

the magnitude of the highest concentration occurring during a

given period.This statistic is analogous to the familiar 100-year

flood, which expresses the probability ofa flood of an observed

magnitude occurring in any given year. In our usage here, the time

scale is in minutes instead of years. Further, like the 100-year flood

plain, it also characterizes a specific location.The calculation of

return period is provided in the Supplementary Material (SM3).

2.4.3.Turbulence Kinetic Energy (TKE)

We calculated TKE for time intervals when the wind direction

and speed were relatively steady for each day.The sampling fre-

quency of the sonic anemometer is 1 Hz,which though not rapid

enough to capture turbulence in the dissipation range, does capture

most of the energy containing eddies.The calculation ofTKE is

provided in the Supplementary Material (SM4).

3. Results and discussion

3.1.Experiment 1: Van Wyck East

The high resolution of the 6-s sampling frequency shows the

nearly instantaneous stochastic variation of PM2.5 concentration in

the roadside environment.Sampling location 1 in Van Wyck East

site adjacent to the highway displays most variable PM2.5 concen-

tration data (Fig.2a),showing frequent spikes above background,

corresponding to passage of especially “dirty” vehicles. Because our

spectrometers cannot detect particles <0.3mm, these spikes are not

caused by primary tailpipe emissions butare either secondary

particles or particles re-suspended from the road surface and lofted

by the turbulent wakes of vehicles (Fig. 3a). Observations across the

vegetated transectshowed far less variation,higher mean con-

centrations, and large spikes in concentration were absent (Fig. 2b),

while the open transect had concentration spikes (Fig.2c).

Return period plots reveal that along the open transect, samples

at 10,23 and 40 m from the road are virtually indistinguishable

from each other (Fig.3a).In comparison,samples on the transect

with trees show differences in magnitude of events at frequencies

exceeding ca. 1 min (Fig.3b).

While trees attenuated concentration spikes,the transect with

trees had higher average PM2.5 concentrations (SM5,Table 2).

Koniographs of the 15 min average concentrations corresponding

to the sampling intervals at the different points on the transect

show the pattern more clearly than the 6-sec koniographs (SM5).

Roadside PM2.5 varied over the course ofthe day in relation to

traffic conditions.Noticeably greater concentration was observed

during the morning and afternoon rush hours, when traffic was low

speed, stop and go (Tong et al., 2000). This flow pattern is typically

more polluting than the steady-speed driving modes,and gener-

ates more total emissions (Tong et al.,2011).

Fig. 2. Koniographs atVan Wyck East at 6 s sampling resolution.a) station 1 at

roadside; b) roving among station 2,3, and 4 (7 m, 15 m,51 m away from the road)

along the vegetated transect,c) roving among station 5,6, and 7 (10 m,23 m, 40 m

away from the road) along the open transect.

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149144

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

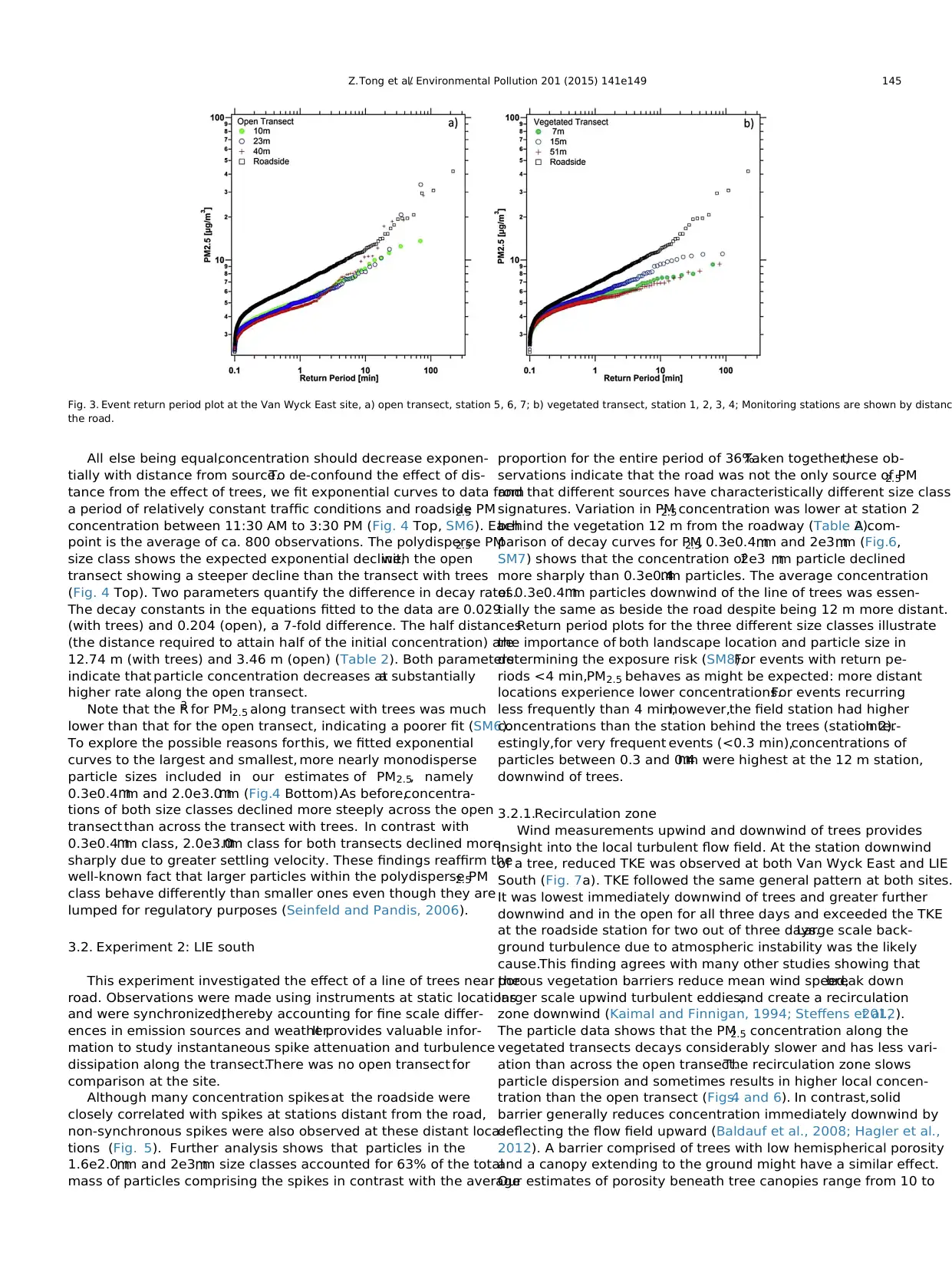

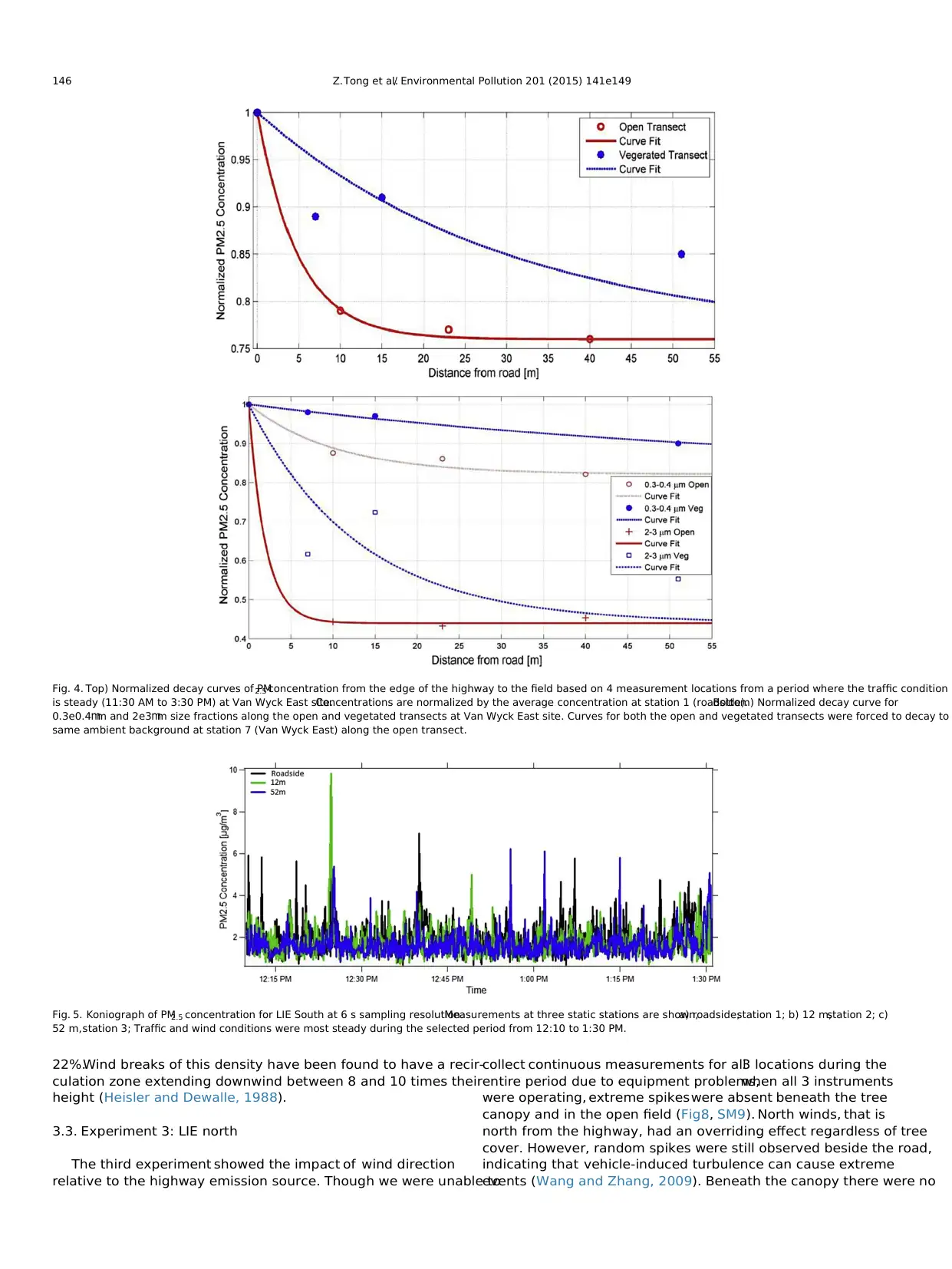

All else being equal,concentration should decrease exponen-

tially with distance from source.To de-confound the effect of dis-

tance from the effect of trees, we fit exponential curves to data from

a period of relatively constant traffic conditions and roadside PM2.5

concentration between 11:30 AM to 3:30 PM (Fig. 4 Top, SM6). Each

point is the average of ca. 800 observations. The polydisperse PM2.5

size class shows the expected exponential decline,with the open

transect showing a steeper decline than the transect with trees

(Fig. 4 Top). Two parameters quantify the difference in decay rates.

The decay constants in the equations fitted to the data are 0.029

(with trees) and 0.204 (open), a 7-fold difference. The half distances

(the distance required to attain half of the initial concentration) are

12.74 m (with trees) and 3.46 m (open) (Table 2). Both parameters

indicate that particle concentration decreases ata substantially

higher rate along the open transect.

Note that the R2 for PM2.5 along transect with trees was much

lower than that for the open transect, indicating a poorer fit (SM6).

To explore the possible reasons forthis, we fitted exponential

curves to the largest and smallest, more nearly monodisperse

particle sizes included in our estimates of PM 2.5, namely

0.3e0.4 mm and 2.0e3.0mm (Fig.4 Bottom).As before,concentra-

tions of both size classes declined more steeply across the open

transect than across the transect with trees. In contrast with

0.3e0.4mm class, 2.0e3.0mm class for both transects declined more

sharply due to greater settling velocity. These findings reaffirm the

well-known fact that larger particles within the polydisperse PM2.5

class behave differently than smaller ones even though they are

lumped for regulatory purposes (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006).

3.2. Experiment 2: LIE south

This experiment investigated the effect of a line of trees near the

road. Observations were made using instruments at static locations

and were synchronized,thereby accounting for fine scale differ-

ences in emission sources and weather.It provides valuable infor-

mation to study instantaneous spike attenuation and turbulence

dissipation along the transect.There was no open transect for

comparison at the site.

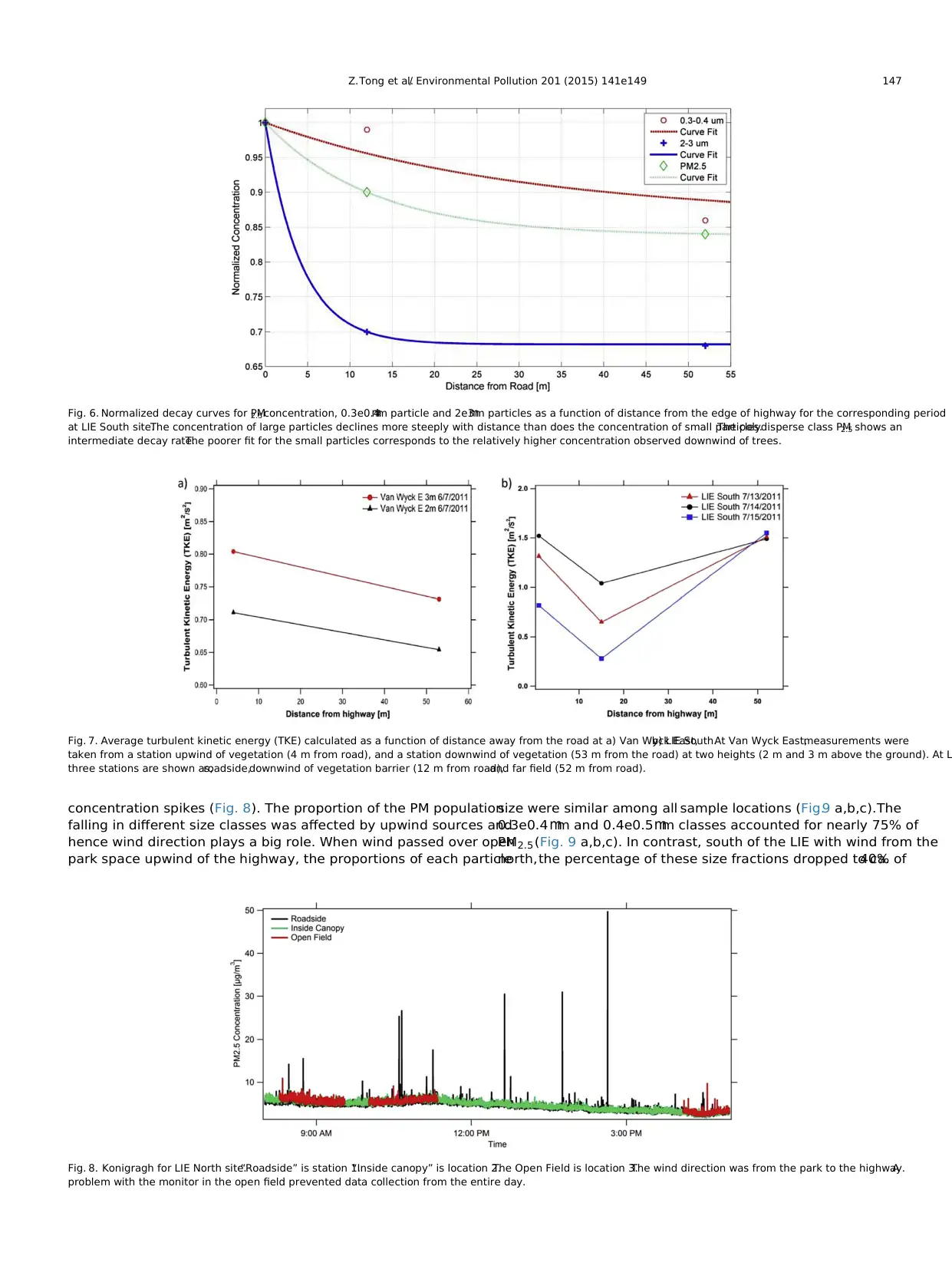

Although many concentration spikes at the roadside were

closely correlated with spikes at stations distant from the road,

non-synchronous spikes were also observed at these distant loca-

tions (Fig. 5). Further analysis shows that particles in the

1.6e2.0mm and 2e3mm size classes accounted for 63% of the total

mass of particles comprising the spikes in contrast with the average

proportion for the entire period of 36%.Taken together,these ob-

servations indicate that the road was not the only source of PM2.5

and that different sources have characteristically different size class

signatures. Variation in PM2.5 concentration was lower at station 2

behind the vegetation 12 m from the roadway (Table 2).A com-

parison of decay curves for PM2.5, 0.3e0.4 mm and 2e3 mm (Fig.6,

SM7) shows that the concentration of2e3 mm particle declined

more sharply than 0.3e0.4mm particles. The average concentration

of 0.3e0.4mm particles downwind of the line of trees was essen-

tially the same as beside the road despite being 12 m more distant.

Return period plots for the three different size classes illustrate

the importance of both landscape location and particle size in

determining the exposure risk (SM8).For events with return pe-

riods <4 min,PM 2.5 behaves as might be expected: more distant

locations experience lower concentrations.For events recurring

less frequently than 4 min,however,the field station had higher

concentrations than the station behind the trees (station 2).Inter-

estingly,for very frequent events (<0.3 min),concentrations of

particles between 0.3 and 0.4mm were highest at the 12 m station,

downwind of trees.

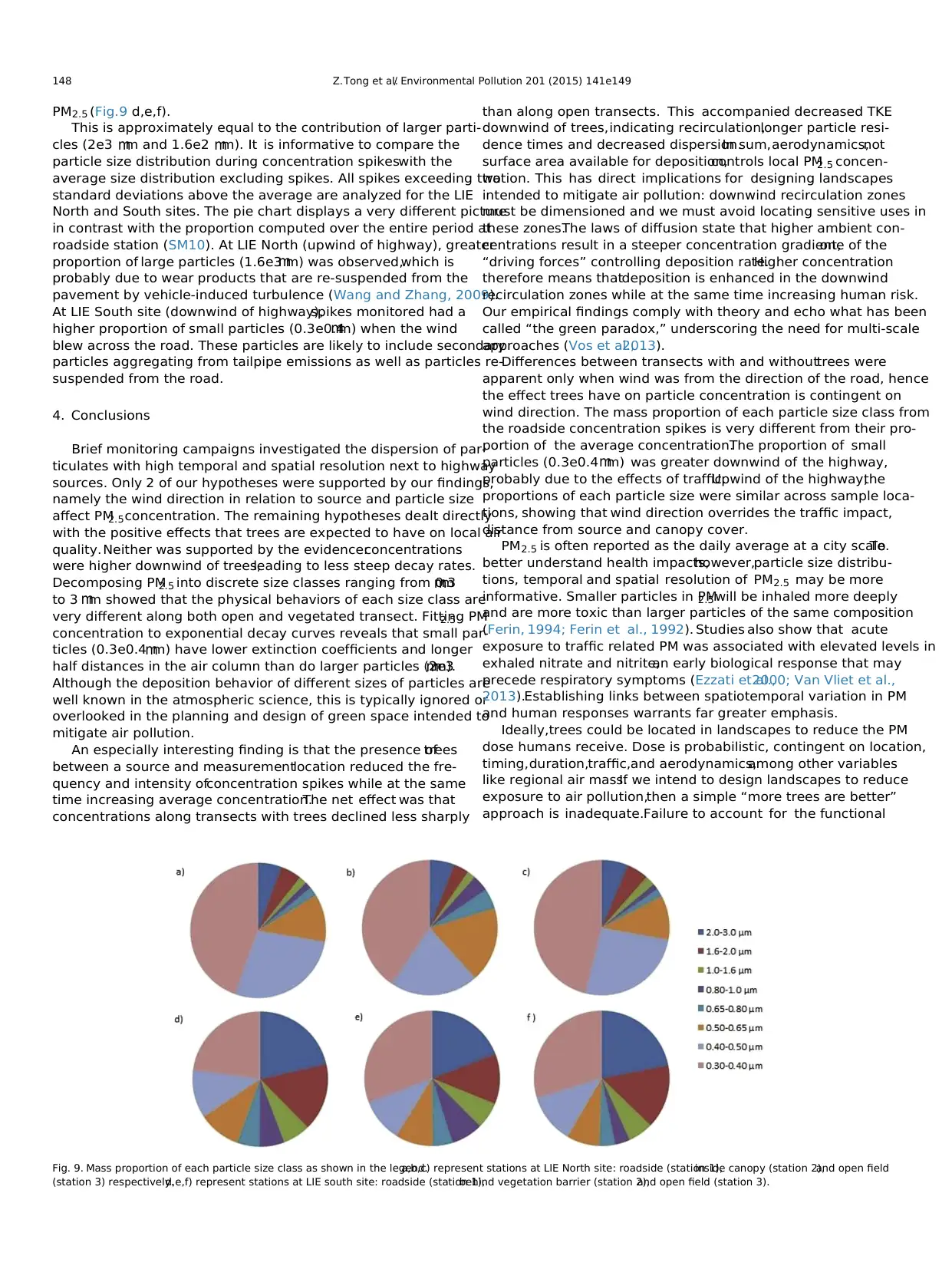

3.2.1.Recirculation zone

Wind measurements upwind and downwind of trees provides

insight into the local turbulent flow field. At the station downwind

of a tree, reduced TKE was observed at both Van Wyck East and LIE

South (Fig. 7a). TKE followed the same general pattern at both sites.

It was lowest immediately downwind of trees and greater further

downwind and in the open for all three days and exceeded the TKE

at the roadside station for two out of three days.Large scale back-

ground turbulence due to atmospheric instability was the likely

cause.This finding agrees with many other studies showing that

porous vegetation barriers reduce mean wind speed,break down

larger scale upwind turbulent eddies,and create a recirculation

zone downwind (Kaimal and Finnigan, 1994; Steffens et al.,2012).

The particle data shows that the PM2.5 concentration along the

vegetated transects decays considerably slower and has less vari-

ation than across the open transect.The recirculation zone slows

particle dispersion and sometimes results in higher local concen-

tration than the open transect (Figs.4 and 6). In contrast,solid

barrier generally reduces concentration immediately downwind by

deflecting the flow field upward (Baldauf et al., 2008; Hagler et al.,

2012). A barrier comprised of trees with low hemispherical porosity

and a canopy extending to the ground might have a similar effect.

Our estimates of porosity beneath tree canopies range from 10 to

Fig. 3. Event return period plot at the Van Wyck East site, a) open transect, station 5, 6, 7; b) vegetated transect, station 1, 2, 3, 4; Monitoring stations are shown by distanc

the road.

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149 145

tially with distance from source.To de-confound the effect of dis-

tance from the effect of trees, we fit exponential curves to data from

a period of relatively constant traffic conditions and roadside PM2.5

concentration between 11:30 AM to 3:30 PM (Fig. 4 Top, SM6). Each

point is the average of ca. 800 observations. The polydisperse PM2.5

size class shows the expected exponential decline,with the open

transect showing a steeper decline than the transect with trees

(Fig. 4 Top). Two parameters quantify the difference in decay rates.

The decay constants in the equations fitted to the data are 0.029

(with trees) and 0.204 (open), a 7-fold difference. The half distances

(the distance required to attain half of the initial concentration) are

12.74 m (with trees) and 3.46 m (open) (Table 2). Both parameters

indicate that particle concentration decreases ata substantially

higher rate along the open transect.

Note that the R2 for PM2.5 along transect with trees was much

lower than that for the open transect, indicating a poorer fit (SM6).

To explore the possible reasons forthis, we fitted exponential

curves to the largest and smallest, more nearly monodisperse

particle sizes included in our estimates of PM 2.5, namely

0.3e0.4 mm and 2.0e3.0mm (Fig.4 Bottom).As before,concentra-

tions of both size classes declined more steeply across the open

transect than across the transect with trees. In contrast with

0.3e0.4mm class, 2.0e3.0mm class for both transects declined more

sharply due to greater settling velocity. These findings reaffirm the

well-known fact that larger particles within the polydisperse PM2.5

class behave differently than smaller ones even though they are

lumped for regulatory purposes (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006).

3.2. Experiment 2: LIE south

This experiment investigated the effect of a line of trees near the

road. Observations were made using instruments at static locations

and were synchronized,thereby accounting for fine scale differ-

ences in emission sources and weather.It provides valuable infor-

mation to study instantaneous spike attenuation and turbulence

dissipation along the transect.There was no open transect for

comparison at the site.

Although many concentration spikes at the roadside were

closely correlated with spikes at stations distant from the road,

non-synchronous spikes were also observed at these distant loca-

tions (Fig. 5). Further analysis shows that particles in the

1.6e2.0mm and 2e3mm size classes accounted for 63% of the total

mass of particles comprising the spikes in contrast with the average

proportion for the entire period of 36%.Taken together,these ob-

servations indicate that the road was not the only source of PM2.5

and that different sources have characteristically different size class

signatures. Variation in PM2.5 concentration was lower at station 2

behind the vegetation 12 m from the roadway (Table 2).A com-

parison of decay curves for PM2.5, 0.3e0.4 mm and 2e3 mm (Fig.6,

SM7) shows that the concentration of2e3 mm particle declined

more sharply than 0.3e0.4mm particles. The average concentration

of 0.3e0.4mm particles downwind of the line of trees was essen-

tially the same as beside the road despite being 12 m more distant.

Return period plots for the three different size classes illustrate

the importance of both landscape location and particle size in

determining the exposure risk (SM8).For events with return pe-

riods <4 min,PM 2.5 behaves as might be expected: more distant

locations experience lower concentrations.For events recurring

less frequently than 4 min,however,the field station had higher

concentrations than the station behind the trees (station 2).Inter-

estingly,for very frequent events (<0.3 min),concentrations of

particles between 0.3 and 0.4mm were highest at the 12 m station,

downwind of trees.

3.2.1.Recirculation zone

Wind measurements upwind and downwind of trees provides

insight into the local turbulent flow field. At the station downwind

of a tree, reduced TKE was observed at both Van Wyck East and LIE

South (Fig. 7a). TKE followed the same general pattern at both sites.

It was lowest immediately downwind of trees and greater further

downwind and in the open for all three days and exceeded the TKE

at the roadside station for two out of three days.Large scale back-

ground turbulence due to atmospheric instability was the likely

cause.This finding agrees with many other studies showing that

porous vegetation barriers reduce mean wind speed,break down

larger scale upwind turbulent eddies,and create a recirculation

zone downwind (Kaimal and Finnigan, 1994; Steffens et al.,2012).

The particle data shows that the PM2.5 concentration along the

vegetated transects decays considerably slower and has less vari-

ation than across the open transect.The recirculation zone slows

particle dispersion and sometimes results in higher local concen-

tration than the open transect (Figs.4 and 6). In contrast,solid

barrier generally reduces concentration immediately downwind by

deflecting the flow field upward (Baldauf et al., 2008; Hagler et al.,

2012). A barrier comprised of trees with low hemispherical porosity

and a canopy extending to the ground might have a similar effect.

Our estimates of porosity beneath tree canopies range from 10 to

Fig. 3. Event return period plot at the Van Wyck East site, a) open transect, station 5, 6, 7; b) vegetated transect, station 1, 2, 3, 4; Monitoring stations are shown by distanc

the road.

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149 145

22%.Wind breaks of this density have been found to have a recir-

culation zone extending downwind between 8 and 10 times their

height (Heisler and Dewalle, 1988).

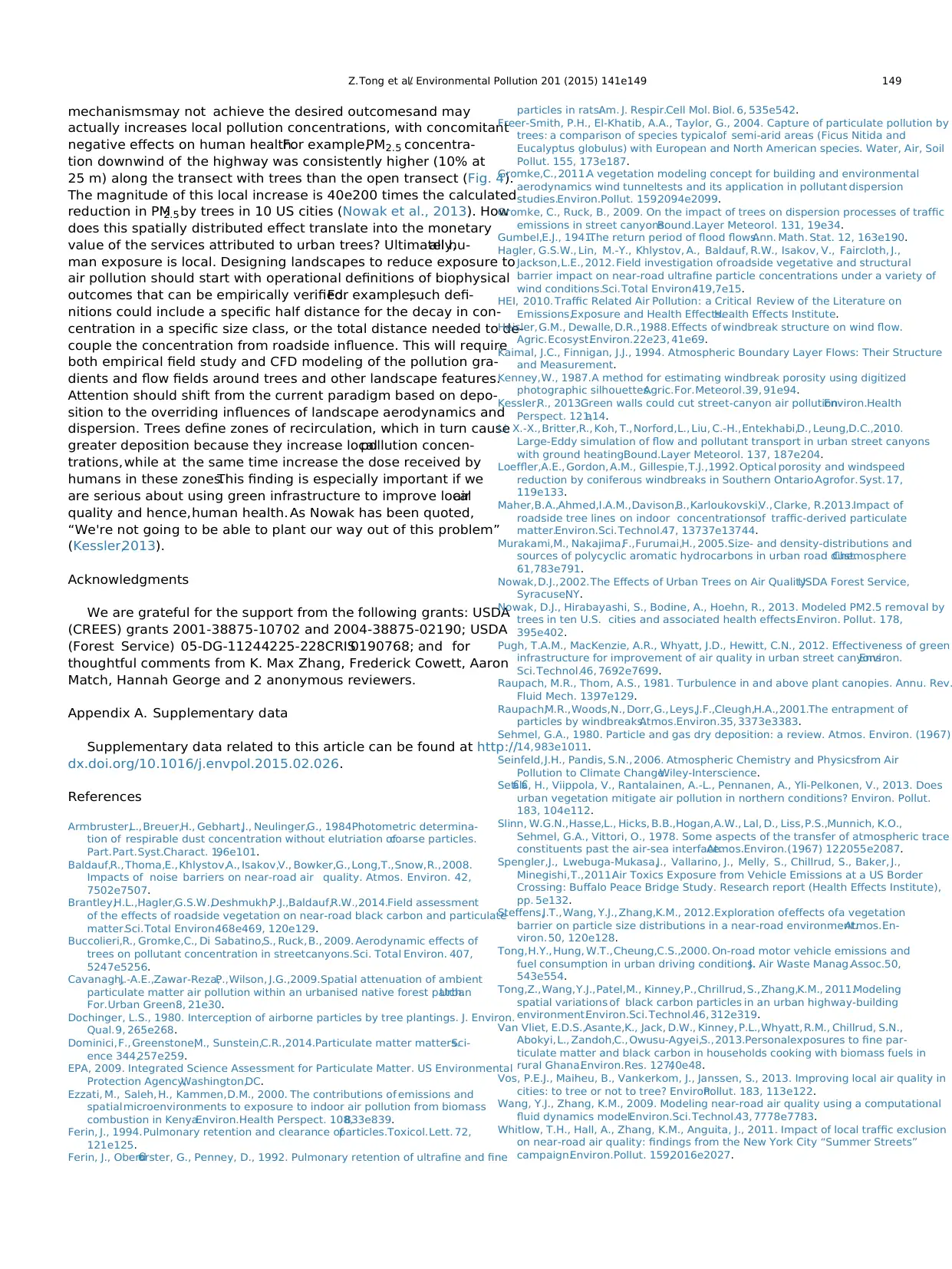

3.3. Experiment 3: LIE north

The third experiment showed the impact of wind direction

relative to the highway emission source. Though we were unable to

collect continuous measurements for all3 locations during the

entire period due to equipment problems,when all 3 instruments

were operating, extreme spikeswere absent beneath the tree

canopy and in the open field (Fig.8, SM9). North winds, that is

north from the highway, had an overriding effect regardless of tree

cover. However, random spikes were still observed beside the road,

indicating that vehicle-induced turbulence can cause extreme

events (Wang and Zhang, 2009). Beneath the canopy there were no

Fig. 4. Top) Normalized decay curves of PM2.5 concentration from the edge of the highway to the field based on 4 measurement locations from a period where the traffic condition

is steady (11:30 AM to 3:30 PM) at Van Wyck East site.Concentrations are normalized by the average concentration at station 1 (roadside).Bottom) Normalized decay curve for

0.3e0.4mm and 2e3mm size fractions along the open and vegetated transects at Van Wyck East site. Curves for both the open and vegetated transects were forced to decay to

same ambient background at station 7 (Van Wyck East) along the open transect.

Fig. 5. Koniograph of PM2.5 concentration for LIE South at 6 s sampling resolution.Measurements at three static stations are shown,a) roadside,station 1; b) 12 m,station 2; c)

52 m,station 3; Traffic and wind conditions were most steady during the selected period from 12:10 to 1:30 PM.

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149146

culation zone extending downwind between 8 and 10 times their

height (Heisler and Dewalle, 1988).

3.3. Experiment 3: LIE north

The third experiment showed the impact of wind direction

relative to the highway emission source. Though we were unable to

collect continuous measurements for all3 locations during the

entire period due to equipment problems,when all 3 instruments

were operating, extreme spikeswere absent beneath the tree

canopy and in the open field (Fig.8, SM9). North winds, that is

north from the highway, had an overriding effect regardless of tree

cover. However, random spikes were still observed beside the road,

indicating that vehicle-induced turbulence can cause extreme

events (Wang and Zhang, 2009). Beneath the canopy there were no

Fig. 4. Top) Normalized decay curves of PM2.5 concentration from the edge of the highway to the field based on 4 measurement locations from a period where the traffic condition

is steady (11:30 AM to 3:30 PM) at Van Wyck East site.Concentrations are normalized by the average concentration at station 1 (roadside).Bottom) Normalized decay curve for

0.3e0.4mm and 2e3mm size fractions along the open and vegetated transects at Van Wyck East site. Curves for both the open and vegetated transects were forced to decay to

same ambient background at station 7 (Van Wyck East) along the open transect.

Fig. 5. Koniograph of PM2.5 concentration for LIE South at 6 s sampling resolution.Measurements at three static stations are shown,a) roadside,station 1; b) 12 m,station 2; c)

52 m,station 3; Traffic and wind conditions were most steady during the selected period from 12:10 to 1:30 PM.

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149146

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

concentration spikes (Fig. 8). The proportion of the PM population

falling in different size classes was affected by upwind sources and

hence wind direction plays a big role. When wind passed over open

park space upwind of the highway, the proportions of each particle

size were similar among all sample locations (Fig.9 a,b,c).The

0.3e0.4 mm and 0.4e0.5 mm classes accounted for nearly 75% of

PM 2.5 (Fig. 9 a,b,c). In contrast, south of the LIE with wind from the

north,the percentage of these size fractions dropped to ca.40% of

Fig. 6. Normalized decay curves for PM2.5 concentration, 0.3e0.4mm particle and 2e3mm particles as a function of distance from the edge of highway for the corresponding period

at LIE South site.The concentration of large particles declines more steeply with distance than does the concentration of small particles.The polydisperse class PM2.5 shows an

intermediate decay rate.The poorer fit for the small particles corresponds to the relatively higher concentration observed downwind of trees.

Fig. 7. Average turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) calculated as a function of distance away from the road at a) Van Wyck East,b) LIE South.At Van Wyck East,measurements were

taken from a station upwind of vegetation (4 m from road), and a station downwind of vegetation (53 m from the road) at two heights (2 m and 3 m above the ground). At L

three stations are shown as,roadside,downwind of vegetation barrier (12 m from road),and far field (52 m from road).

Fig. 8. Konigragh for LIE North site.“Roadside” is station 1.“Inside canopy” is location 2.The Open Field is location 3.The wind direction was from the park to the highway.A

problem with the monitor in the open field prevented data collection from the entire day.

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149 147

falling in different size classes was affected by upwind sources and

hence wind direction plays a big role. When wind passed over open

park space upwind of the highway, the proportions of each particle

size were similar among all sample locations (Fig.9 a,b,c).The

0.3e0.4 mm and 0.4e0.5 mm classes accounted for nearly 75% of

PM 2.5 (Fig. 9 a,b,c). In contrast, south of the LIE with wind from the

north,the percentage of these size fractions dropped to ca.40% of

Fig. 6. Normalized decay curves for PM2.5 concentration, 0.3e0.4mm particle and 2e3mm particles as a function of distance from the edge of highway for the corresponding period

at LIE South site.The concentration of large particles declines more steeply with distance than does the concentration of small particles.The polydisperse class PM2.5 shows an

intermediate decay rate.The poorer fit for the small particles corresponds to the relatively higher concentration observed downwind of trees.

Fig. 7. Average turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) calculated as a function of distance away from the road at a) Van Wyck East,b) LIE South.At Van Wyck East,measurements were

taken from a station upwind of vegetation (4 m from road), and a station downwind of vegetation (53 m from the road) at two heights (2 m and 3 m above the ground). At L

three stations are shown as,roadside,downwind of vegetation barrier (12 m from road),and far field (52 m from road).

Fig. 8. Konigragh for LIE North site.“Roadside” is station 1.“Inside canopy” is location 2.The Open Field is location 3.The wind direction was from the park to the highway.A

problem with the monitor in the open field prevented data collection from the entire day.

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149 147

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

PM 2.5 (Fig.9 d,e,f).

This is approximately equal to the contribution of larger parti-

cles (2e3 mm and 1.6e2 mm). It is informative to compare the

particle size distribution during concentration spikeswith the

average size distribution excluding spikes. All spikes exceeding two

standard deviations above the average are analyzed for the LIE

North and South sites. The pie chart displays a very different picture

in contrast with the proportion computed over the entire period at

roadside station (SM10). At LIE North (upwind of highway), greater

proportion of large particles (1.6e3mm) was observed,which is

probably due to wear products that are re-suspended from the

pavement by vehicle-induced turbulence (Wang and Zhang, 2009).

At LIE South site (downwind of highway),spikes monitored had a

higher proportion of small particles (0.3e0.4mm) when the wind

blew across the road. These particles are likely to include secondary

particles aggregating from tailpipe emissions as well as particles re-

suspended from the road.

4. Conclusions

Brief monitoring campaigns investigated the dispersion of par-

ticulates with high temporal and spatial resolution next to highway

sources. Only 2 of our hypotheses were supported by our findings,

namely the wind direction in relation to source and particle size

affect PM2.5 concentration. The remaining hypotheses dealt directly

with the positive effects that trees are expected to have on local air

quality.Neither was supported by the evidence:concentrations

were higher downwind of trees,leading to less steep decay rates.

Decomposing PM2.5 into discrete size classes ranging from 0.3mm

to 3 mm showed that the physical behaviors of each size class are

very different along both open and vegetated transect. Fitting PM2.5

concentration to exponential decay curves reveals that small par-

ticles (0.3e0.4mm) have lower extinction coefficients and longer

half distances in the air column than do larger particles (2e3mm).

Although the deposition behavior of different sizes of particles are

well known in the atmospheric science, this is typically ignored or

overlooked in the planning and design of green space intended to

mitigate air pollution.

An especially interesting finding is that the presence oftrees

between a source and measurementlocation reduced the fre-

quency and intensity ofconcentration spikes while at the same

time increasing average concentration.The net effect was that

concentrations along transects with trees declined less sharply

than along open transects. This accompanied decreased TKE

downwind of trees,indicating recirculation,longer particle resi-

dence times and decreased dispersion.In sum,aerodynamics,not

surface area available for deposition,controls local PM2.5 concen-

tration. This has direct implications for designing landscapes

intended to mitigate air pollution: downwind recirculation zones

must be dimensioned and we must avoid locating sensitive uses in

these zones.The laws of diffusion state that higher ambient con-

centrations result in a steeper concentration gradient,one of the

“driving forces” controlling deposition rate.Higher concentration

therefore means thatdeposition is enhanced in the downwind

recirculation zones while at the same time increasing human risk.

Our empirical findings comply with theory and echo what has been

called “the green paradox,” underscoring the need for multi-scale

approaches (Vos et al.,2013).

Differences between transects with and withouttrees were

apparent only when wind was from the direction of the road, hence

the effect trees have on particle concentration is contingent on

wind direction. The mass proportion of each particle size class from

the roadside concentration spikes is very different from their pro-

portion of the average concentration.The proportion of small

particles (0.3e0.4 mm) was greater downwind of the highway,

probably due to the effects of traffic.Upwind of the highway,the

proportions of each particle size were similar across sample loca-

tions, showing that wind direction overrides the traffic impact,

distance from source and canopy cover.

PM 2.5 is often reported as the daily average at a city scale.To

better understand health impacts,however,particle size distribu-

tions, temporal and spatial resolution of PM 2.5 may be more

informative. Smaller particles in PM2.5 will be inhaled more deeply

and are more toxic than larger particles of the same composition

(Ferin, 1994; Ferin et al., 1992). Studies also show that acute

exposure to traffic related PM was associated with elevated levels in

exhaled nitrate and nitrite,an early biological response that may

precede respiratory symptoms (Ezzati et al.,2000; Van Vliet et al.,

2013).Establishing links between spatiotemporal variation in PM

and human responses warrants far greater emphasis.

Ideally,trees could be located in landscapes to reduce the PM

dose humans receive. Dose is probabilistic, contingent on location,

timing,duration,traffic,and aerodynamics,among other variables

like regional air mass.If we intend to design landscapes to reduce

exposure to air pollution,then a simple “more trees are better”

approach is inadequate.Failure to account for the functional

Fig. 9. Mass proportion of each particle size class as shown in the legend.a,b,c) represent stations at LIE North site: roadside (station 1),inside canopy (station 2),and open field

(station 3) respectively.d,e,f) represent stations at LIE south site: roadside (station 1),behind vegetation barrier (station 2),and open field (station 3).

Z.Tong et al./ Environmental Pollution 201 (2015) 141e149148

This is approximately equal to the contribution of larger parti-

cles (2e3 mm and 1.6e2 mm). It is informative to compare the

particle size distribution during concentration spikeswith the

average size distribution excluding spikes. All spikes exceeding two

standard deviations above the average are analyzed for the LIE

North and South sites. The pie chart displays a very different picture

in contrast with the proportion computed over the entire period at

roadside station (SM10). At LIE North (upwind of highway), greater

proportion of large particles (1.6e3mm) was observed,which is

probably due to wear products that are re-suspended from the

pavement by vehicle-induced turbulence (Wang and Zhang, 2009).

At LIE South site (downwind of highway),spikes monitored had a

higher proportion of small particles (0.3e0.4mm) when the wind

blew across the road. These particles are likely to include secondary

particles aggregating from tailpipe emissions as well as particles re-

suspended from the road.

4. Conclusions

Brief monitoring campaigns investigated the dispersion of par-

ticulates with high temporal and spatial resolution next to highway

sources. Only 2 of our hypotheses were supported by our findings,

namely the wind direction in relation to source and particle size

affect PM2.5 concentration. The remaining hypotheses dealt directly

with the positive effects that trees are expected to have on local air

quality.Neither was supported by the evidence:concentrations

were higher downwind of trees,leading to less steep decay rates.

Decomposing PM2.5 into discrete size classes ranging from 0.3mm

to 3 mm showed that the physical behaviors of each size class are

very different along both open and vegetated transect. Fitting PM2.5

concentration to exponential decay curves reveals that small par-

ticles (0.3e0.4mm) have lower extinction coefficients and longer

half distances in the air column than do larger particles (2e3mm).

Although the deposition behavior of different sizes of particles are

well known in the atmospheric science, this is typically ignored or

overlooked in the planning and design of green space intended to

mitigate air pollution.

An especially interesting finding is that the presence oftrees

between a source and measurementlocation reduced the fre-

quency and intensity ofconcentration spikes while at the same

time increasing average concentration.The net effect was that

concentrations along transects with trees declined less sharply

than along open transects. This accompanied decreased TKE

downwind of trees,indicating recirculation,longer particle resi-

dence times and decreased dispersion.In sum,aerodynamics,not

surface area available for deposition,controls local PM2.5 concen-

tration. This has direct implications for designing landscapes

intended to mitigate air pollution: downwind recirculation zones

must be dimensioned and we must avoid locating sensitive uses in

these zones.The laws of diffusion state that higher ambient con-

centrations result in a steeper concentration gradient,one of the

“driving forces” controlling deposition rate.Higher concentration

therefore means thatdeposition is enhanced in the downwind

recirculation zones while at the same time increasing human risk.

Our empirical findings comply with theory and echo what has been

called “the green paradox,” underscoring the need for multi-scale

approaches (Vos et al.,2013).

Differences between transects with and withouttrees were

apparent only when wind was from the direction of the road, hence

the effect trees have on particle concentration is contingent on

wind direction. The mass proportion of each particle size class from

the roadside concentration spikes is very different from their pro-