Investigating Glyphosate Resistance in Erigeron bonariensis: A Study

VerifiedAdded on 2020/02/24

|23

|6943

|76

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the mechanisms of glyphosate resistance in Erigeron bonariensis, a close relative of Erigeron canadensis, aiming to determine if EPSPS and ABC transporter genes (M10 and M11) are responsible for resistance. The study involves RNA extraction from glyphosate-treated and untreated individuals collected from various sites. Quantitative PCR and RNA-Seq analysis are used to examine gene expression. Total RNA is used for cDNA library synthesis, sequenced via Illumina HiSeq, assembled using Trinity, and analyzed for differential expression and functional annotation. The introduction provides a comprehensive background on herbicide resistance, including its history, the impact of glyphosate, and the two main resistance mechanisms: target-site and non-target site resistance. It discusses the evolution of glyphosate resistance in various weed species, the role of EPSPS, and the importance of translocation in herbicide efficacy. The report also reviews previous studies on glyphosate resistance in other plant species, highlighting different mechanisms and the significance of ABC transporters. The research seeks to determine if the resistance observed in E. bonariensis involves similar mechanisms or if other genes are responsible.

ABSTRACT

Herbicide resistance is the heritable ability of weeds to survive and reproduce in the presence of

herbicide doses that are lethal to the wild type of the species. One mechanism of such resistance

is non-target site reduced translocation of the herbicide, in which vacuolar sequestration prevents

the chemical from spreading around the plant. Resistance of Erigeron canadensis to glyphosate

is thought to involve this mechanism and it is believed that EPSPS and the ABC transporter

genes M10 and M11 may be responsible for this resistance. This study therefore aims at

determining through quantitative PCR and RNA-Seq if these genes provide the mechanism for

glyphosate resistance in Erigeron bonariensis, a close relative of Erigeron canadensis, or if there

are other genes responsible for the resistance observed in this species. RNA will be extracted

from the leaves of glyphosate treated and untreated individuals, collected from 10 sites in the

Central Valley and two control populations of Erigeron bonariensis, for quantitative real time

PCR and RNA-Seq analysis. Total RNA for RNA-Seq analysis will be used in cDNA library

synthesis and sequenced via Illumina HiSeq. Sequenced reads will be assembled de novo using

the software Trinity, assigned to respective genes with the pipeline HTSeq, tested for differential

expression by DESeq and functionally annotated using the NCBI nonredundant protein (Nr)

database.

1

Herbicide resistance is the heritable ability of weeds to survive and reproduce in the presence of

herbicide doses that are lethal to the wild type of the species. One mechanism of such resistance

is non-target site reduced translocation of the herbicide, in which vacuolar sequestration prevents

the chemical from spreading around the plant. Resistance of Erigeron canadensis to glyphosate

is thought to involve this mechanism and it is believed that EPSPS and the ABC transporter

genes M10 and M11 may be responsible for this resistance. This study therefore aims at

determining through quantitative PCR and RNA-Seq if these genes provide the mechanism for

glyphosate resistance in Erigeron bonariensis, a close relative of Erigeron canadensis, or if there

are other genes responsible for the resistance observed in this species. RNA will be extracted

from the leaves of glyphosate treated and untreated individuals, collected from 10 sites in the

Central Valley and two control populations of Erigeron bonariensis, for quantitative real time

PCR and RNA-Seq analysis. Total RNA for RNA-Seq analysis will be used in cDNA library

synthesis and sequenced via Illumina HiSeq. Sequenced reads will be assembled de novo using

the software Trinity, assigned to respective genes with the pipeline HTSeq, tested for differential

expression by DESeq and functionally annotated using the NCBI nonredundant protein (Nr)

database.

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

INTRODUCTION

Moss (2002) defines herbicide resistance as the heritable ability of weeds to survive and

reproduce in the presence of herbicide doses that are lethal to the wild type of the species.

Herbicide resistance was first observed by an ornamental nursery owner in 1968 (Jasieniuk at al.

1996). The first of resistance to herbicide was recorded in Senecio vulgaris; at which seeds from

the resistant biotypes were found to resist the chemicals simazine and atrazine (Pieterse 2010). In

1974, resistance to glyphosate herbicide became a problem for corn growers (Gressel et al.

1982). Since then, more than 187 species of weeds throughout the globe have developed

resistance against various herbicides which have targeted a broad range of biochemical processes

(Pieterse 2010). The first case of herbicide resistance was reported in 1981 at UC Riverside,

California (Holt at al. 1981) and recently, more species which are have also evolved resistance to

various other herbicide chemicals employed by farmers in California (Malone 2014).

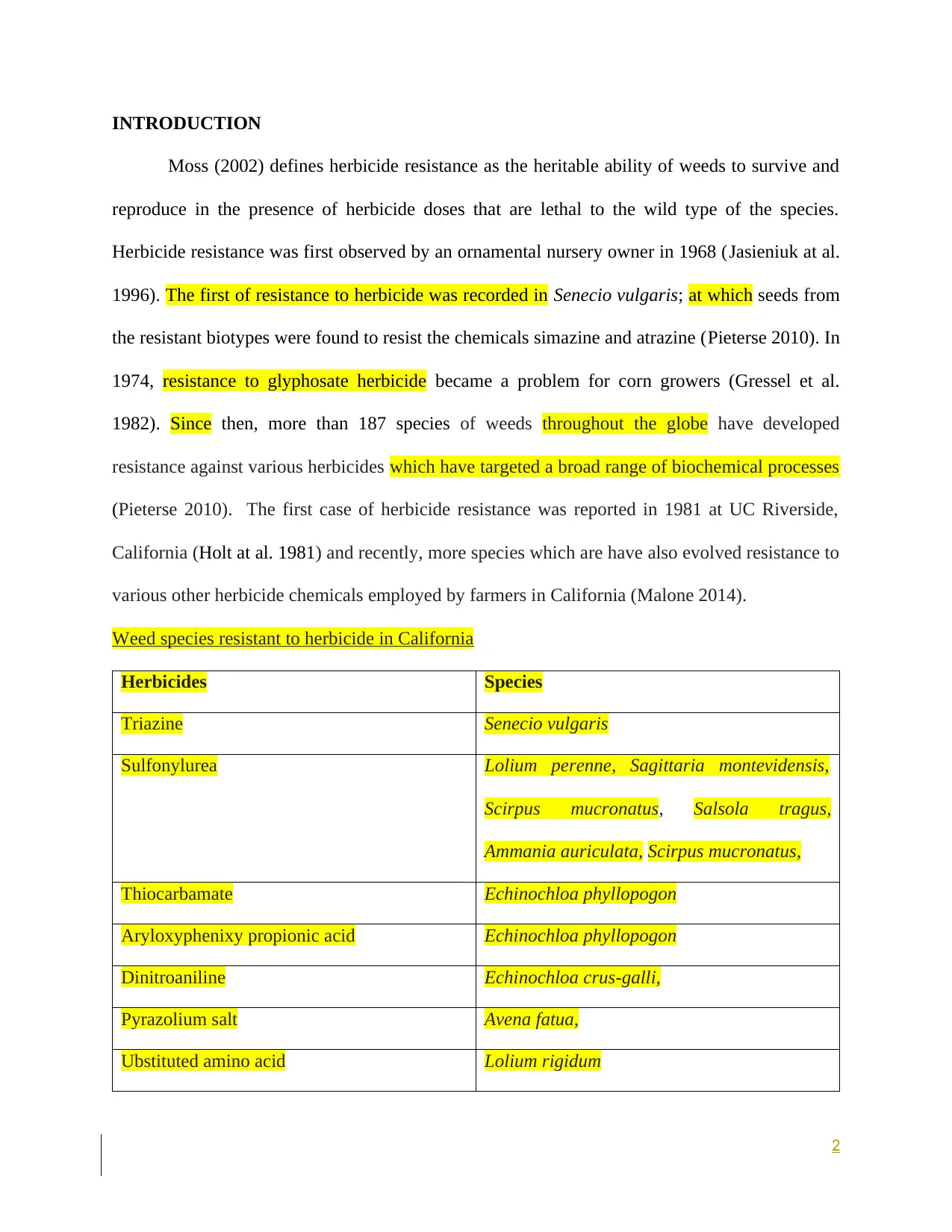

Weed species resistant to herbicide in California

Herbicides Species

Triazine Senecio vulgaris

Sulfonylurea Lolium perenne, Sagittaria montevidensis,

Scirpus mucronatus, Salsola tragus,

Ammania auriculata, Scirpus mucronatus,

Thiocarbamate Echinochloa phyllopogon

Aryloxyphenixy propionic acid Echinochloa phyllopogon

Dinitroaniline Echinochloa crus-galli,

Pyrazolium salt Avena fatua,

Ubstituted amino acid Lolium rigidum

2

Moss (2002) defines herbicide resistance as the heritable ability of weeds to survive and

reproduce in the presence of herbicide doses that are lethal to the wild type of the species.

Herbicide resistance was first observed by an ornamental nursery owner in 1968 (Jasieniuk at al.

1996). The first of resistance to herbicide was recorded in Senecio vulgaris; at which seeds from

the resistant biotypes were found to resist the chemicals simazine and atrazine (Pieterse 2010). In

1974, resistance to glyphosate herbicide became a problem for corn growers (Gressel et al.

1982). Since then, more than 187 species of weeds throughout the globe have developed

resistance against various herbicides which have targeted a broad range of biochemical processes

(Pieterse 2010). The first case of herbicide resistance was reported in 1981 at UC Riverside,

California (Holt at al. 1981) and recently, more species which are have also evolved resistance to

various other herbicide chemicals employed by farmers in California (Malone 2014).

Weed species resistant to herbicide in California

Herbicides Species

Triazine Senecio vulgaris

Sulfonylurea Lolium perenne, Sagittaria montevidensis,

Scirpus mucronatus, Salsola tragus,

Ammania auriculata, Scirpus mucronatus,

Thiocarbamate Echinochloa phyllopogon

Aryloxyphenixy propionic acid Echinochloa phyllopogon

Dinitroaniline Echinochloa crus-galli,

Pyrazolium salt Avena fatua,

Ubstituted amino acid Lolium rigidum

2

Glyphosate herbicide (marketed by Monsanto as RoundUp®) contains N-

phosphonomethyl glycine that acts against plants by hindering aromatic amino acid synthesis

(Bridges 2003). Upon application on leaves, the plant takes in glyphosate through pores and is

transported through the phloem alongside with other products of photosynthesis to all parts of the

plant. In susceptible plants, glyphosate hinders the role of the plastidine enzyme 5-

enolpiruvilshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) important in the prechorismate step of the

shikimate pathway. In the absence of glyphosate, this enzyme works by condensing shikimate-3-

phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate into 5-enolpiruvilshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP) with

inorganic phosphate, initiating the anabolism of aromatic amino acids (Ferreira 2008).

Disruption of the synthesis of aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine)

eventually kills the plant (Herman and Weaver 1999).

Glyphosate has become the world’s most commonly used herbicide since its market

introduction in 1974 (Baylis 2000). Its use around the globe is contributed by several factors to

make it the most utilized herbicide. The ideal characteristics that it has include the potency

against an extensive variety of species (monocots and dicots), less harmful activity against

animals than other herbicides (the enzyme EPSPS which is not found in animals), rapid

microbial degeneration and low cost (Duke and Powles 2008). Also, it has been commonly used

in recent years as a part of reduced tillage frameworks with a dependence on herbicides to

control weeds that have numerous environmental benefits and economic importance (Owen

2008; Powles 2008; Shaner 2000). With the adoption of genetically modified crops with

glyphosate resistance in 1996, the already high levels of glyphosate application increased

(Powles & Preston 2006). The combined effects of glyphosate ignorant over-usage in glyphosate

resistant hairy fleabane and completely reduced tillage has created an agricultural environment

3

phosphonomethyl glycine that acts against plants by hindering aromatic amino acid synthesis

(Bridges 2003). Upon application on leaves, the plant takes in glyphosate through pores and is

transported through the phloem alongside with other products of photosynthesis to all parts of the

plant. In susceptible plants, glyphosate hinders the role of the plastidine enzyme 5-

enolpiruvilshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS) important in the prechorismate step of the

shikimate pathway. In the absence of glyphosate, this enzyme works by condensing shikimate-3-

phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate into 5-enolpiruvilshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP) with

inorganic phosphate, initiating the anabolism of aromatic amino acids (Ferreira 2008).

Disruption of the synthesis of aromatic amino acids (phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine)

eventually kills the plant (Herman and Weaver 1999).

Glyphosate has become the world’s most commonly used herbicide since its market

introduction in 1974 (Baylis 2000). Its use around the globe is contributed by several factors to

make it the most utilized herbicide. The ideal characteristics that it has include the potency

against an extensive variety of species (monocots and dicots), less harmful activity against

animals than other herbicides (the enzyme EPSPS which is not found in animals), rapid

microbial degeneration and low cost (Duke and Powles 2008). Also, it has been commonly used

in recent years as a part of reduced tillage frameworks with a dependence on herbicides to

control weeds that have numerous environmental benefits and economic importance (Owen

2008; Powles 2008; Shaner 2000). With the adoption of genetically modified crops with

glyphosate resistance in 1996, the already high levels of glyphosate application increased

(Powles & Preston 2006). The combined effects of glyphosate ignorant over-usage in glyphosate

resistant hairy fleabane and completely reduced tillage has created an agricultural environment

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

that has an increased risk of evolution of glyphosate resistance (Neve at al. 2003). Herbicide

resistance is stimulated by the re-current use of herbicides with the same active chemical

ingredients (LeBaron 1991), and so inevitably, glyphosate resistance has evolved in many weeds

(Powles et al. 1998). Because of its ability to control numerous weed species adaptability to low

tillage systems, and low animal toxicity result in increased glyphosate remaining to be a key

factor in modern systems because growers are unwilling to return to the greater tillage systems or

older, more toxic herbicides (Beckie 2012).

Two mechanisms that confer resistance have contributed to glyphosate resistance in

weeds are target-site and non-target site resistance (REF). Target site-based resistance is a

condition where resistance evolves due to a gene mutation resulting in a structural or chemical

change to a target site enzyme so that the herbicide fails to effectively inhibit the normal enzyme

function (Powles and Preston 2006). The missense mutation may involve a specific nucleotide

substitution in the coding region producing a different amino acid that results in structural,

hydrophobicity or charge change in site of the enzyme that the herbicide targets, making it less

sensitive to inhibition by the herbicide. A few weeds such as goosegrass (Eleusine indica (L.)

Gaertn.), have evolved weak target site mutagenesis (Lee and Ngim, 2000; Dinelli et al. 2006) of

the enzyme EPSPS, via a substitution mutation that replaced the amino acid proline with serine

at position 106 (Pro106-Ser). Ng et al. (2004 & 2005) demonstrated that substitution of proline

by threonine (Pro106-Thr) confers resistance glyphosate resistance to goosegrass The mutated

EPSPS enzyme has a low affinity for glyphosate but almost normal affinity for phosphoenol

pyruvate (the enzyme’s usual substrate); permitting the shikimate pathway can proceed normally

even in the presence of glyphosate (Gaines et al. 2010).

4

resistance is stimulated by the re-current use of herbicides with the same active chemical

ingredients (LeBaron 1991), and so inevitably, glyphosate resistance has evolved in many weeds

(Powles et al. 1998). Because of its ability to control numerous weed species adaptability to low

tillage systems, and low animal toxicity result in increased glyphosate remaining to be a key

factor in modern systems because growers are unwilling to return to the greater tillage systems or

older, more toxic herbicides (Beckie 2012).

Two mechanisms that confer resistance have contributed to glyphosate resistance in

weeds are target-site and non-target site resistance (REF). Target site-based resistance is a

condition where resistance evolves due to a gene mutation resulting in a structural or chemical

change to a target site enzyme so that the herbicide fails to effectively inhibit the normal enzyme

function (Powles and Preston 2006). The missense mutation may involve a specific nucleotide

substitution in the coding region producing a different amino acid that results in structural,

hydrophobicity or charge change in site of the enzyme that the herbicide targets, making it less

sensitive to inhibition by the herbicide. A few weeds such as goosegrass (Eleusine indica (L.)

Gaertn.), have evolved weak target site mutagenesis (Lee and Ngim, 2000; Dinelli et al. 2006) of

the enzyme EPSPS, via a substitution mutation that replaced the amino acid proline with serine

at position 106 (Pro106-Ser). Ng et al. (2004 & 2005) demonstrated that substitution of proline

by threonine (Pro106-Thr) confers resistance glyphosate resistance to goosegrass The mutated

EPSPS enzyme has a low affinity for glyphosate but almost normal affinity for phosphoenol

pyruvate (the enzyme’s usual substrate); permitting the shikimate pathway can proceed normally

even in the presence of glyphosate (Gaines et al. 2010).

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Non-target site mutations including sequestration and detoxification in addition to

translocation function by limiting the translocation of glyphosate (Wakelin et al. 2004) to target

sites. According to Claus and Brehrens’ (1976) study-rapid and widespread glyphosate

translocation is necessary to achieve high herbicide efficacy. There is therefore a possibility that

changes in its translocation may confer resistance. The study that unraveled this phenomenon

was carried out in rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaud.; Lorraine-Colwill et al. 2002), and

indicated that resistance in at least one biotype was not due to EPSPS enzyme target mutagenesis

or degradation. In the same study, it was shown that there was no significant difference between

glyphosate resistance and susceptible species in EPSPS sensitivity or expression level or in

glyphosate absorption. However, the patters of glyphosate translocation differed. The

researchers observed accumulation of glyphosate at lower parts of the plant through diffusion

and to some extend in the roots in susceptible plants whereas in resistant plants, it accumulated

in the tip of the leaves through transpiration with a negligible amount transported to the roots

(Lorraine-Colwill et al. 2002). (Welkelin et al. 2004) found the same pattern of reduced

glyphosate translocation when working with only four glyphosate resistant ryegrass populations

in Australia.

Researchers investigating mechanisms of glyphosate resistance in all Lolium rigidum

species have not found large differences in glyphosate translocation. Perez et al. (2004) found no

significant difference in glyphosate absorption and translocation between susceptible and

resistant Chilean Lolium plants. In an investigation in glyphosate resistance in Californian

Lolium, Simarmata et al. (2003) found significantly higher glyphosate concentration in treated

leaves of glyphosate resistant plants 2-3 days after treatment. Interestingly, these authors

observed no other significant differences in glyphosate absorption or translocation between

5

translocation function by limiting the translocation of glyphosate (Wakelin et al. 2004) to target

sites. According to Claus and Brehrens’ (1976) study-rapid and widespread glyphosate

translocation is necessary to achieve high herbicide efficacy. There is therefore a possibility that

changes in its translocation may confer resistance. The study that unraveled this phenomenon

was carried out in rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaud.; Lorraine-Colwill et al. 2002), and

indicated that resistance in at least one biotype was not due to EPSPS enzyme target mutagenesis

or degradation. In the same study, it was shown that there was no significant difference between

glyphosate resistance and susceptible species in EPSPS sensitivity or expression level or in

glyphosate absorption. However, the patters of glyphosate translocation differed. The

researchers observed accumulation of glyphosate at lower parts of the plant through diffusion

and to some extend in the roots in susceptible plants whereas in resistant plants, it accumulated

in the tip of the leaves through transpiration with a negligible amount transported to the roots

(Lorraine-Colwill et al. 2002). (Welkelin et al. 2004) found the same pattern of reduced

glyphosate translocation when working with only four glyphosate resistant ryegrass populations

in Australia.

Researchers investigating mechanisms of glyphosate resistance in all Lolium rigidum

species have not found large differences in glyphosate translocation. Perez et al. (2004) found no

significant difference in glyphosate absorption and translocation between susceptible and

resistant Chilean Lolium plants. In an investigation in glyphosate resistance in Californian

Lolium, Simarmata et al. (2003) found significantly higher glyphosate concentration in treated

leaves of glyphosate resistant plants 2-3 days after treatment. Interestingly, these authors

observed no other significant differences in glyphosate absorption or translocation between

5

resistant and susceptible plants (Lorraine-Colwill et al. 2002). These varying results suggest

potentially different non-target resistance mechanisms to glyphosate in different Lolium

populations. In general, most studies observed no differences in glyphosate absorption, but with

phloem translocation reduced greatly (Feng et al. 2004; Koger and Reddy 2005) in resistant

species. Failure of glyphosate translocation from leaves to the roots seems to be important

mechanisms that lead to resistance in certain Lolium biotypes (Preston 2002).

Erigeron species are annual or short-lived perennial plants native to the Americas that

have in the recent past become cosmopolitan and invasive weeds of many crops and arable lands

(Prieur-Richard et al. 2000). The genus is in the sunflower family (Asteraceae) and the weed

species were formerly placed in the genus Conyza before taxonomic revision ( Baldwin, 2012).

Erigeron spp. are prolific seed producers: a single plant is capable of producing thousands of

viable wind dispersed seeds (Weaver 2001; Shields et al. 2006).

Erigeron spp. have become very common and problematic weedy plants in agronomic

crops around the world (Weaver 2001). This is probably because they are capable of adapting to

plain soils where they establish in the absence of tillage (Buhler 1992). The opportunistic nature

of Erigeron in undisturbed areas makes them well- suited for becoming established in

agricultural fields and surrounding areas; particularly in no-tillage or where tillage is minimal

(Bruce and Kells 1990). Considering the fact that over the last two decades the amount of crop

hectares in conservation tillage has increased in is=n CA (Young 2006), weeds such as Erigeron

spp. are becoming a great concern.

The two main species of Erigeron in California are hairy fleabane (Erigeron bonariensis

L.) and horseweed (Erigeron canadensis L.), both summer annuals. Unlike horseweed, which is

weedy across the U.S., fleabane is an agricultural problem specific to California (Shrestha 2008).

6

potentially different non-target resistance mechanisms to glyphosate in different Lolium

populations. In general, most studies observed no differences in glyphosate absorption, but with

phloem translocation reduced greatly (Feng et al. 2004; Koger and Reddy 2005) in resistant

species. Failure of glyphosate translocation from leaves to the roots seems to be important

mechanisms that lead to resistance in certain Lolium biotypes (Preston 2002).

Erigeron species are annual or short-lived perennial plants native to the Americas that

have in the recent past become cosmopolitan and invasive weeds of many crops and arable lands

(Prieur-Richard et al. 2000). The genus is in the sunflower family (Asteraceae) and the weed

species were formerly placed in the genus Conyza before taxonomic revision ( Baldwin, 2012).

Erigeron spp. are prolific seed producers: a single plant is capable of producing thousands of

viable wind dispersed seeds (Weaver 2001; Shields et al. 2006).

Erigeron spp. have become very common and problematic weedy plants in agronomic

crops around the world (Weaver 2001). This is probably because they are capable of adapting to

plain soils where they establish in the absence of tillage (Buhler 1992). The opportunistic nature

of Erigeron in undisturbed areas makes them well- suited for becoming established in

agricultural fields and surrounding areas; particularly in no-tillage or where tillage is minimal

(Bruce and Kells 1990). Considering the fact that over the last two decades the amount of crop

hectares in conservation tillage has increased in is=n CA (Young 2006), weeds such as Erigeron

spp. are becoming a great concern.

The two main species of Erigeron in California are hairy fleabane (Erigeron bonariensis

L.) and horseweed (Erigeron canadensis L.), both summer annuals. Unlike horseweed, which is

weedy across the U.S., fleabane is an agricultural problem specific to California (Shrestha 2008).

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The optimal temperature for germination of hairy fleabane ranges between 2.03 and 2.34 degrees

centigrade and the seeds usually germinate under moderate water availability conditions

(Karlsson and Milberg, 2007). Based on these characteristics, conditions are ideal for fleabane

germination in the cooler seasons of California’s Central Valley, October-March. Hairy fleabane

has adapted to a wide range of conditions ranging from irrigated vineyard and orchard systems

dry non-crop areas (Shrestha et al. 2014). Information is available concerning the economic

impact of hairy fleabane (Pandolfo et al. 2016).

Erigeron bonariensis have been shown to exhibit high concentration of glyphosate in the

southern Central Valley of California (Okada et al. 2013), but the actual resistance mechanism is

still obscure, especially the dynamics that occur at the genetic level that bring about the plant

obscuring glyphosate resistance. A number of studies have been performed on fleabane’s close

relative, E. canadensis, in an attempt to establish the presence or absence of target site mutations

at codon 106 of the EPSPS gene, as well the synchronization mechanism of EPSPS enzyme

overexpression levels (Tani et al. 2015). However, the presence and number of these genes and

their specific roles in glyphosate resistance in fleabane have not been established. The ABC

transporter genes’ expression relationship with glyphosate transport in the resistant biotypes

needs to be examined in Hairy fleabane (Tani et al. 2015), and the fact that reduced translocation

is the suspected mechanism of glyphosate resistance in fleabane from other parts of the world

(Ferreira et al. 2008). It is also imperative to examine target mutations in the EPSPS gene

(Gaines et al. 2010), are involved in fleabane glyphosate resistance. In addition to identifying the

known target site mutation in EPSPS (Pro106 in Lolium rigidum), it is important to determine if

there are other mutations that confer target site resistance via changes in the EPSPS enzyme

itself.

7

centigrade and the seeds usually germinate under moderate water availability conditions

(Karlsson and Milberg, 2007). Based on these characteristics, conditions are ideal for fleabane

germination in the cooler seasons of California’s Central Valley, October-March. Hairy fleabane

has adapted to a wide range of conditions ranging from irrigated vineyard and orchard systems

dry non-crop areas (Shrestha et al. 2014). Information is available concerning the economic

impact of hairy fleabane (Pandolfo et al. 2016).

Erigeron bonariensis have been shown to exhibit high concentration of glyphosate in the

southern Central Valley of California (Okada et al. 2013), but the actual resistance mechanism is

still obscure, especially the dynamics that occur at the genetic level that bring about the plant

obscuring glyphosate resistance. A number of studies have been performed on fleabane’s close

relative, E. canadensis, in an attempt to establish the presence or absence of target site mutations

at codon 106 of the EPSPS gene, as well the synchronization mechanism of EPSPS enzyme

overexpression levels (Tani et al. 2015). However, the presence and number of these genes and

their specific roles in glyphosate resistance in fleabane have not been established. The ABC

transporter genes’ expression relationship with glyphosate transport in the resistant biotypes

needs to be examined in Hairy fleabane (Tani et al. 2015), and the fact that reduced translocation

is the suspected mechanism of glyphosate resistance in fleabane from other parts of the world

(Ferreira et al. 2008). It is also imperative to examine target mutations in the EPSPS gene

(Gaines et al. 2010), are involved in fleabane glyphosate resistance. In addition to identifying the

known target site mutation in EPSPS (Pro106 in Lolium rigidum), it is important to determine if

there are other mutations that confer target site resistance via changes in the EPSPS enzyme

itself.

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Candidate ABC transporter genes for our study were selected based on previous research

on horseweed where it was demonstrated that application of glyphosate to either resistant or

susceptible biotypes did not influence EPSPS gene extension, but ABC transporter genes M10

and M11 were tremendously upregulated in the resistant plants but not in the non-resistant

biotypes (Nol et al. 2012). This suggests a possible role of M11 and M10 ABC transporter genes

in resistance to glyphosate in Erigeron Canadensis (horseweed). These ABC transporters may

function to sequester glyphosate into the vacuole resulting in a non-target site mechanism of

glyphosate resistance in horseweed (Peng et al. 2010).

P450 genes have been demonstrated to play an important role in mediating non-target

herbicide resistance. An affirmation of the relationship between p450 enzyme activity and

herbicide resistance in weeds by Yuan et al. (2007), suggested that this class of genes also

contributes to the difficulty with which the weeds are eliminated. P450 genes code for several

enzymes that can participate in herbicide detoxification in phase 1 metabolic processes. Their

expression products bring about reactions such as hydroxylation, decarboxylation, and

deamination, among other processes that all aim at neutralizing the toxin in the plant body

(Morant et al. 2003). The p450 enzymes have been shown synchronized with phase 2 detoxifying

enzymes to ensure that herbicide effects are neutralized in the plant body (Menendez et al. 1996).

Even though no specific p450 genes have yet been identified from herbicide resistant weeds,

p450 genes are candidates for study via RNA-Seg in glyphosate-resistant hairy fleabane to

determine whether they are unregulated in resistant plants before or after glyphosate treatment,

and if so, whether they work in conjunction with other relevant detoxification genes.

Weeds are very competitive for resources, both above and below ground, and therefore

contribute to reduction in crop yield. As herbicides are the most commonly used weed control

8

on horseweed where it was demonstrated that application of glyphosate to either resistant or

susceptible biotypes did not influence EPSPS gene extension, but ABC transporter genes M10

and M11 were tremendously upregulated in the resistant plants but not in the non-resistant

biotypes (Nol et al. 2012). This suggests a possible role of M11 and M10 ABC transporter genes

in resistance to glyphosate in Erigeron Canadensis (horseweed). These ABC transporters may

function to sequester glyphosate into the vacuole resulting in a non-target site mechanism of

glyphosate resistance in horseweed (Peng et al. 2010).

P450 genes have been demonstrated to play an important role in mediating non-target

herbicide resistance. An affirmation of the relationship between p450 enzyme activity and

herbicide resistance in weeds by Yuan et al. (2007), suggested that this class of genes also

contributes to the difficulty with which the weeds are eliminated. P450 genes code for several

enzymes that can participate in herbicide detoxification in phase 1 metabolic processes. Their

expression products bring about reactions such as hydroxylation, decarboxylation, and

deamination, among other processes that all aim at neutralizing the toxin in the plant body

(Morant et al. 2003). The p450 enzymes have been shown synchronized with phase 2 detoxifying

enzymes to ensure that herbicide effects are neutralized in the plant body (Menendez et al. 1996).

Even though no specific p450 genes have yet been identified from herbicide resistant weeds,

p450 genes are candidates for study via RNA-Seg in glyphosate-resistant hairy fleabane to

determine whether they are unregulated in resistant plants before or after glyphosate treatment,

and if so, whether they work in conjunction with other relevant detoxification genes.

Weeds are very competitive for resources, both above and below ground, and therefore

contribute to reduction in crop yield. As herbicides are the most commonly used weed control

8

method, weed populations are subject to significant evolutionary pressure for the mechanisms to

survive herbicide exposure. This herbicide selection pressure has been present for decades in

weed population- resulting in herbicide efficacy and rising crop losses (Green et al. 2008).

Information about the genetic basis of herbicide resistance is key in effective weed management

and has the potential to bolster agricultural productivity. Elucidating the role of both target site

and non-target mutations in resistance to various chemicals is important in the genetic

engineering of crop plant resistance, especially by plant transformation techniques. Modern

molecular biology techniques permit the determination of the genes that are upregulated in

response to herbicide exposure in particular weed species, to begin to decipher the mechanisms

behind non-target-site-based resistance (NTSR). The aim of this study is to elaborate on the

specific role of the p450 genes in herbicide resistance in fleabane and identify, any additional

target and non-target mutations that may yet be undiscovered,. This study will reaffirm the

presence of glyphosate-resistant genes in hairy fleabane in the Central Valley; and will identify

whether it has evolved once or multiple times,. This information is critical to the cultivators to

ensure that effective and sustainable weed management and control strategies are put in place.

SPECIFIC AIMS

Broad Objective: To identify the presence of genetic basis of glyphosate (RoundUp®)

resistance in Central Valley population of the agricultural weed fleabane (Erigeron bonariensis

L.).

9

survive herbicide exposure. This herbicide selection pressure has been present for decades in

weed population- resulting in herbicide efficacy and rising crop losses (Green et al. 2008).

Information about the genetic basis of herbicide resistance is key in effective weed management

and has the potential to bolster agricultural productivity. Elucidating the role of both target site

and non-target mutations in resistance to various chemicals is important in the genetic

engineering of crop plant resistance, especially by plant transformation techniques. Modern

molecular biology techniques permit the determination of the genes that are upregulated in

response to herbicide exposure in particular weed species, to begin to decipher the mechanisms

behind non-target-site-based resistance (NTSR). The aim of this study is to elaborate on the

specific role of the p450 genes in herbicide resistance in fleabane and identify, any additional

target and non-target mutations that may yet be undiscovered,. This study will reaffirm the

presence of glyphosate-resistant genes in hairy fleabane in the Central Valley; and will identify

whether it has evolved once or multiple times,. This information is critical to the cultivators to

ensure that effective and sustainable weed management and control strategies are put in place.

SPECIFIC AIMS

Broad Objective: To identify the presence of genetic basis of glyphosate (RoundUp®)

resistance in Central Valley population of the agricultural weed fleabane (Erigeron bonariensis

L.).

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Specific Objectives:

1. To determine differential gene expression in known populations of glyphosate-resistant

vs. sensitive fleabane before and after different glyphosate application rates.

2. To establish if the candidate genes EPSPS and ABC transporter genes M10 and M11, as

well as to-be-determined candidate genes from RNA-Seq, are significant in glyphosate

herbicide resistance in fleabane populations.

3. To determine whether different glyphosate-resistant populations of fleabane from the

Central Valley have different genetic bases for resistance.

Hypothesis: Glyphosate resistance in fleabane is due to non-target site resistance, facilitated by

transcriptional upregulation of ABC transporter genes.

Specific Hypotheses:

1. Glyphosate application will show significant result in upregulation of ABC transporter

genes in glyphosate –resistant hairy fleabane but not the glyphosate-sensitive population.

2. Target site resistance in the EPSPS gene is not significant in glyphosate resistance but

M10 and M11 (and possibly other ABC transporter genes) participate in non-target site

herbicide resistance in fleabane.

3. Different glyphosate-resistant Central Valley fleabane populations have different

expression levels for M10 and M11 (and possibly other ABC transporter genes), due to

different origins of resistance.

10

1. To determine differential gene expression in known populations of glyphosate-resistant

vs. sensitive fleabane before and after different glyphosate application rates.

2. To establish if the candidate genes EPSPS and ABC transporter genes M10 and M11, as

well as to-be-determined candidate genes from RNA-Seq, are significant in glyphosate

herbicide resistance in fleabane populations.

3. To determine whether different glyphosate-resistant populations of fleabane from the

Central Valley have different genetic bases for resistance.

Hypothesis: Glyphosate resistance in fleabane is due to non-target site resistance, facilitated by

transcriptional upregulation of ABC transporter genes.

Specific Hypotheses:

1. Glyphosate application will show significant result in upregulation of ABC transporter

genes in glyphosate –resistant hairy fleabane but not the glyphosate-sensitive population.

2. Target site resistance in the EPSPS gene is not significant in glyphosate resistance but

M10 and M11 (and possibly other ABC transporter genes) participate in non-target site

herbicide resistance in fleabane.

3. Different glyphosate-resistant Central Valley fleabane populations have different

expression levels for M10 and M11 (and possibly other ABC transporter genes), due to

different origins of resistance.

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Sample preparation

Ten different populations of Erigeron bonariensis (each population containing 18 plants) will be

selected for germination from the central valley 2016 (in Waselkov lab). HFS, HFR and one

hybrid fleabane/ horseweed population for DNA analysis (from Dr. Shrestha) will be used. HFS

and HFR will be used as control plants as HFS are susceptible and the HFR are glyphosate in

nature. Some seeds will be bulked from our 20 plants per population for the 10 Valley

populations. Collected seeds from each plant in their own envelope will be mixed from these

envelopes to make a "bulk population" sample for this experiment. 4 Petri dishes will be labelled

for each population, each with its own filter paper. 25 seeds for each Petri plate will be

counted, except for the GR population, which has very low germination success--- 8 Petri plates

will be used for this population. After adding the seeds, add 10 ml of distilled water plates will

be sealed with Para film. Growth chamber will be used to germinate seeds, set at 20/15 C

day/night temperature and 13-hr day length. There is no control over humidity in these chambers

(Nandula et al. 2006's). Each day, the number of seedlings will be counted on each plate by keep

careful track in an Excel spreadsheet. After two weeks in the growth chamber, germination

percentage on each plate and average for each population will be counted. Germination is

defined as the stage when the root or the stem has extended >1 mm beyond the seed coat.

Experiment will be run for 4 weeks. For the 10 Valley populations and GS and GR controls: At

the 2-3 true leaf stage, 18 plants/population into 5 cm^2 or 4-inch pots will be transplanted. This

is for the glyphosate spraying experiment (modeled on Okada et al. 2014)—we will spray 2

replicates of 6 plants each per population, with 6 plants of the GR and GS populations as a

control each time. The third replicate of 6 plants will be an unsprayed control—we will grow

11

Sample preparation

Ten different populations of Erigeron bonariensis (each population containing 18 plants) will be

selected for germination from the central valley 2016 (in Waselkov lab). HFS, HFR and one

hybrid fleabane/ horseweed population for DNA analysis (from Dr. Shrestha) will be used. HFS

and HFR will be used as control plants as HFS are susceptible and the HFR are glyphosate in

nature. Some seeds will be bulked from our 20 plants per population for the 10 Valley

populations. Collected seeds from each plant in their own envelope will be mixed from these

envelopes to make a "bulk population" sample for this experiment. 4 Petri dishes will be labelled

for each population, each with its own filter paper. 25 seeds for each Petri plate will be

counted, except for the GR population, which has very low germination success--- 8 Petri plates

will be used for this population. After adding the seeds, add 10 ml of distilled water plates will

be sealed with Para film. Growth chamber will be used to germinate seeds, set at 20/15 C

day/night temperature and 13-hr day length. There is no control over humidity in these chambers

(Nandula et al. 2006's). Each day, the number of seedlings will be counted on each plate by keep

careful track in an Excel spreadsheet. After two weeks in the growth chamber, germination

percentage on each plate and average for each population will be counted. Germination is

defined as the stage when the root or the stem has extended >1 mm beyond the seed coat.

Experiment will be run for 4 weeks. For the 10 Valley populations and GS and GR controls: At

the 2-3 true leaf stage, 18 plants/population into 5 cm^2 or 4-inch pots will be transplanted. This

is for the glyphosate spraying experiment (modeled on Okada et al. 2014)—we will spray 2

replicates of 6 plants each per population, with 6 plants of the GR and GS populations as a

control each time. The third replicate of 6 plants will be an unsprayed control—we will grow

11

these GR and GS plants up for multiplication of seeds for future studies (like replicating drought

experiment). After transplanting into small pots, plants will be grown to the 5-8 leaf stage, as per

Okada et al. 2014. 2 replicates of the plants with glyphosate at this stage (1X and 2X) will be

sprayed, and one replicate will be unsprayed. Randomized plants will be randomized among

treatment before spraying, and a complete randomized block design will be done after spraying,

to minimize spatial effects in the greenhouse. The setting up of the greenhouse for the rearing of

the samples began with the minimal headspace (few if any of the plants would grow into a

hanging plant) and utmost lighting in great consideration. Square footage was also to be minimal

as the samples requires not as much clearance. The freestanding design will be favored due to the

maximum lighting provided by the design unlike the attached design which would limit the

lighting to only the sides. Research design, growth conditions and exposure to glyphosate will

be as described in Okada et al. (2013; 2014). Prior to exposure to glyphosate, several leaves will

be collected from all the populations and stored in a -800C freezer for RNA extraction. Twenty-

four hours after exposure to glyphosate, leaves will be collected from all the individuals and

stored in the -800C freezer for RNA analysis. The leaves are to be selected randomly ensuring

inclusiveness of all strata (pots/trays) picking equal number of sample subjects per stratum

randomly.

RNA extraction

Leaves will be harvested, stored at -80°C, and ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA will be

isolated from the leaves using the Qiagen Plant RNeasy Mini Kit, using the protocol included

with the kit, and stored at -20°C C until downstream gene-expression analysis. Potential genomic

DNA will be removed using DNase (FisherSci) and RNA will be measured using Qubit® dsDNA

HS Assay Kits. Denaturing gel electrophoresis will be done to assess RNA quality.

12

experiment). After transplanting into small pots, plants will be grown to the 5-8 leaf stage, as per

Okada et al. 2014. 2 replicates of the plants with glyphosate at this stage (1X and 2X) will be

sprayed, and one replicate will be unsprayed. Randomized plants will be randomized among

treatment before spraying, and a complete randomized block design will be done after spraying,

to minimize spatial effects in the greenhouse. The setting up of the greenhouse for the rearing of

the samples began with the minimal headspace (few if any of the plants would grow into a

hanging plant) and utmost lighting in great consideration. Square footage was also to be minimal

as the samples requires not as much clearance. The freestanding design will be favored due to the

maximum lighting provided by the design unlike the attached design which would limit the

lighting to only the sides. Research design, growth conditions and exposure to glyphosate will

be as described in Okada et al. (2013; 2014). Prior to exposure to glyphosate, several leaves will

be collected from all the populations and stored in a -800C freezer for RNA extraction. Twenty-

four hours after exposure to glyphosate, leaves will be collected from all the individuals and

stored in the -800C freezer for RNA analysis. The leaves are to be selected randomly ensuring

inclusiveness of all strata (pots/trays) picking equal number of sample subjects per stratum

randomly.

RNA extraction

Leaves will be harvested, stored at -80°C, and ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA will be

isolated from the leaves using the Qiagen Plant RNeasy Mini Kit, using the protocol included

with the kit, and stored at -20°C C until downstream gene-expression analysis. Potential genomic

DNA will be removed using DNase (FisherSci) and RNA will be measured using Qubit® dsDNA

HS Assay Kits. Denaturing gel electrophoresis will be done to assess RNA quality.

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 23

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.