E. coli Pathotypes: Relevance in the Era of Whole-Genome Sequencing

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/17

|9

|11895

|16

Report

AI Summary

This report, published in Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, investigates the continuing relevance of Escherichia coli pathotypes in the age of whole-genome sequencing (WGS). The study explores the limitations of traditional subtyping schemes (biotyping, serotyping, pathotyping) and highlights the advantages of WGS in accurately identifying E. coli subtypes based on allelic variation and gene content. It delves into the various E. coli pathotypes associated with intestinal and extraintestinal diseases, including EPEC, EIEC, ETEC, EHEC, EAEC, DAEC, AIEC, and ExPEC subtypes like UPEC and NMEC, and their defining virulence factors. The report emphasizes the importance of understanding both core and accessory genomes for a comprehensive typing scheme that reduces anomalies and promotes a better understanding of E. coli spread and disease mechanisms. The authors also discuss the diagnostic markers, essential virulence determinants, and genetic characteristics of each pathotype, including the role of Shiga toxins, LEE pathogenicity island, and various adhesins. The paper concludes by suggesting that a typing scheme based on genome sequences could refine pathotype definitions and improve our understanding of E. coli pathogenesis.

REVIEW

published: 18 November 2016

doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00141

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 1 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

Edited by:

NikhilA. Thomas,

Dalhousie University, Canada

Reviewed by:

Fernando Navarro-Garcia,

CINVESTAV, Mexico

Jorge Blanco,

University of Santiago de Compostela,

Spain

*Correspondence:

Roy M. Robins-Browne

r.browne@unimelb.edu.au

Received: 31 August 2016

Accepted: 13 October 2016

Published: 18 November 2016

Citation:

Robins-Browne RM, Holt KE, Ingle DJ,

Hocking DM, Yang J and Tauschek M

(2016) Are Escherichia coliPathotypes

StillRelevant in the Era of

Whole-Genome Sequencing?

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6:141.

doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00141

Are Escherichia coli Pathotypes Still

Relevant in the Era of Whole-Genome

Sequencing?

Roy M. Robins-Browne1, 2

*, Kathryn E. Holt3, 4, Danielle J. Ingle1, 3, 4

, Dianna M. Hocking1,

Ji Yang1 and Marija Tauschek1

1 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, The University of

Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia,2 Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, RoyalChildren’s Hospital, Parkville, VIC,

Australia,3 Centre for Systems Genomics, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia,4 Department of

Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, The University of Melbourne,

Parkville, VIC, Australia

The empiricaland pragmatic nature of diagnostic microbiology has given rise to sever

different schemes to subtype E.coli,including biotyping,serotyping,and pathotyping.

These schemes have proved invaluable in identifying and tracking outbreaks,and for

prognostication in individualcases ofinfection,but they are imprecise and potentially

misleading due to the malleability and continuous evolution ofE. coli.Whole genome

sequencing can be used to accurately determine E.coli subtypes thatare based on

allelic variation or differences in gene content, such as serotyping and pathotyping.

genome sequencing also provides information about single nucleotide polymorphism

the core genome of E. coli, which form the basis of sequence typing, and is more re

than other systems for tracking the evolution and spread of individualstrains. A typing

scheme for E. colibased on genome sequences that includes elements of both the cor

and accessory genomes, should reduce typing anomalies and promote understandin

of how different varieties of E. colispread and cause disease. Such a scheme could also

define pathotypes more precisely than current methods.

Keywords: E. coli, diarrhoea, bacterial typing, pathotype, pathogenesis, sequence type, whole genome sequence

Escherichia coli is the most comprehensively studied bacterium on earth.Because it is relatively

easy to manipulate genetically, it has become a popular laboratory workhorse. Its natura

however, is the intestinal tract of humans and other mammals. For this reason it is used

health as an indicator of faecal contamination of water and other consumables.

Despite its ubiquity as a commensal,E. coliis also an importantpathogen ofhumans and

domestic animals. It can become established and cause disease in tissues other than the

tract.These so-called extraintestinalpathogenic E.coli (ExPEC) are important causes of wound

infection, urinary tract infection, peritonitis, pneumonia, meningitis, and septicaemia. Th

group includes named subtypes,such as uropathogenic E.coli (UPEC), neonatalmeningitis-

associated E.coli (NMEC),and sepsis-associated E.coli (SEPEC) (Pitout,2012;Leimbach et al.,

2013).

Infections caused by ExPEC are usually opportunistic,i.e.,they occur mostoften in hosts

who are compromised in some way,such as by having a dysfunctional urinary tract or systemi

immunocompromise due to neutropenia or extremes of age. Nevertheless, some ExPEC

better equipped to cause extraintestinalinfections than others due to factors that facilitate their

published: 18 November 2016

doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00141

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 1 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

Edited by:

NikhilA. Thomas,

Dalhousie University, Canada

Reviewed by:

Fernando Navarro-Garcia,

CINVESTAV, Mexico

Jorge Blanco,

University of Santiago de Compostela,

Spain

*Correspondence:

Roy M. Robins-Browne

r.browne@unimelb.edu.au

Received: 31 August 2016

Accepted: 13 October 2016

Published: 18 November 2016

Citation:

Robins-Browne RM, Holt KE, Ingle DJ,

Hocking DM, Yang J and Tauschek M

(2016) Are Escherichia coliPathotypes

StillRelevant in the Era of

Whole-Genome Sequencing?

Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6:141.

doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00141

Are Escherichia coli Pathotypes Still

Relevant in the Era of Whole-Genome

Sequencing?

Roy M. Robins-Browne1, 2

*, Kathryn E. Holt3, 4, Danielle J. Ingle1, 3, 4

, Dianna M. Hocking1,

Ji Yang1 and Marija Tauschek1

1 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, The University of

Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia,2 Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, RoyalChildren’s Hospital, Parkville, VIC,

Australia,3 Centre for Systems Genomics, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia,4 Department of

Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, The University of Melbourne,

Parkville, VIC, Australia

The empiricaland pragmatic nature of diagnostic microbiology has given rise to sever

different schemes to subtype E.coli,including biotyping,serotyping,and pathotyping.

These schemes have proved invaluable in identifying and tracking outbreaks,and for

prognostication in individualcases ofinfection,but they are imprecise and potentially

misleading due to the malleability and continuous evolution ofE. coli.Whole genome

sequencing can be used to accurately determine E.coli subtypes thatare based on

allelic variation or differences in gene content, such as serotyping and pathotyping.

genome sequencing also provides information about single nucleotide polymorphism

the core genome of E. coli, which form the basis of sequence typing, and is more re

than other systems for tracking the evolution and spread of individualstrains. A typing

scheme for E. colibased on genome sequences that includes elements of both the cor

and accessory genomes, should reduce typing anomalies and promote understandin

of how different varieties of E. colispread and cause disease. Such a scheme could also

define pathotypes more precisely than current methods.

Keywords: E. coli, diarrhoea, bacterial typing, pathotype, pathogenesis, sequence type, whole genome sequence

Escherichia coli is the most comprehensively studied bacterium on earth.Because it is relatively

easy to manipulate genetically, it has become a popular laboratory workhorse. Its natura

however, is the intestinal tract of humans and other mammals. For this reason it is used

health as an indicator of faecal contamination of water and other consumables.

Despite its ubiquity as a commensal,E. coliis also an importantpathogen ofhumans and

domestic animals. It can become established and cause disease in tissues other than the

tract.These so-called extraintestinalpathogenic E.coli (ExPEC) are important causes of wound

infection, urinary tract infection, peritonitis, pneumonia, meningitis, and septicaemia. Th

group includes named subtypes,such as uropathogenic E.coli (UPEC), neonatalmeningitis-

associated E.coli (NMEC),and sepsis-associated E.coli (SEPEC) (Pitout,2012;Leimbach et al.,

2013).

Infections caused by ExPEC are usually opportunistic,i.e.,they occur mostoften in hosts

who are compromised in some way,such as by having a dysfunctional urinary tract or systemi

immunocompromise due to neutropenia or extremes of age. Nevertheless, some ExPEC

better equipped to cause extraintestinalinfections than others due to factors that facilitate their

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Robins-Browne et al. E. coliPathotypes

ability to colonisetissues.Theseincludetype I fimbriae,

pyelonephritis-associated pili(PAP), and AfA/Dr adhesins in

the case ofUPEC, or the K1 polysaccharide capsule,which

allows NMEC and SEPEC to evade complement-mediated killing

(Pitout, 2012; Leimbach et al., 2013).

The pathotypes of E.colithat are associated with intestinal

disease are known collectively as intestinalpathogenic E.coli

(IPEC) or diarrheagenic E.coli (DEC)—although notall of

the subtypesin this group necessarily cause diarrhoea.The

individualpathotypes of DEC include enteropathogenic E.coli

(EPEC),enteroinvasive E.coli (EIEC), enterotoxigenic E.coli

(ETEC), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enteroaggregative E.

coli(EAEC),diffusely-adherent E.coli(DAEC),and adherent-

invasive E.coli(AIEC) (Nataro and Kaper,1998;Kaper et al.,

2004; Croxen et al., 2013). In addition, the entire genus Shigella

is a DEC pathotype,which closely resemblesEIEC in terms

of virulence attributes and pathogenicity,but is distinguishable

from other strains of E. coli by virtue of its biochemical activity

(Lan etal., 2004).Accordingly,shigellae can be regarded as

members of the EIEC pathotype.

Each DEC pathotype represents a collection ofstrains that

possess similar virulence factors to each other and cause similar

diseases with similar pathology.Unlike ExPEC,where there are

no specific virulence determinants that exclusively define each

subtype,mostDEC pathotypes are defined by the possession

of one or more pathotype-specificvirulencemarkers,and

sometimesby the absence ofothers.Severalof the defining

markers of DEC pathotypes are proven virulence determinants

of that pathotype,but for EAEC,DAEC,and AIEC the role of

these markers in virulence is not proven (Table 1).

DEC PATHOTYPES

In this section,we provide a brief overview of DEC pathotypes

with an emphasison their defining characteristicsand key

virulence determinants (where known). We also point out some

importantgapsin the understanding ofcertain pathotypes.

For more detailed information on DEC in general,readers are

referred to reviews by Nataro and Kaper (1998),Kaper etal.

(2004),Clements et al.(2012),and Croxen et al.(2013).In the

bibliography, we have also included references to review articles

dealing with individual DEC pathotypes.

Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC)

EPEC was the first pathotype of DEC to be discovered, and is an

important cause of diarrhoea and premature death in children,

especially in developing countries (Robins-Browne,1987).As

a group,EPEC is characterised by the presence ofthe locus

of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (McDaniel

and Kaper,1997;Robins-Browne and Hartland,2002;Croxen

et al., 2013). This ∼40-kbp island encodes (i) an outer membrane

adhesive protein,known asintimin thatis encoded by the

eae gene,(ii) a type 3 protein secretory system,(iii) several

type 3-secreted effectors,including the Tir protein which is the

translocated receptor for intimin (Kenny et al., 1997).

Expression of the LEE is associated with distinctive attaching-

effacing lesions in the intestinalepithelium which characterise

EPEC pathology (Moon et al., 1983; Tzipori et al., 1985). Almo

all genes within the LEE are required for the production of

these lesions, and studies in adult volunteers have demonstra

that intimin and EspB,a key componentof the type 3

secretion system,are essentialvirulence determinants of EPEC

(Donnenberg etal., 1993;Tacketet al., 2000).An accessory

virulence determinant,which EPEC also requires for virulence

in humans, is the bundle-forming pilus (BFP) (Girón et al., 199

Bieber et al., 1998). Some human isolates of EPEC naturally la

BFP,but may cause disease (Trabulsi et al.,2002;Nguyen et al.,

2006). These strains, known as atypical EPEC are associated

persistent diarrhoea in children (Nguyen et al.,2006).Atypical

EPEC are genetically diverse and appear to vary in virulence

(Tennant et al., 2009; Ingle et al., 2016a).

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC)

EHEC first came to attention as the cause oftwo outbreaks

of haemorrhagic colitis (HC) in the USA during 1982 (Riley

et al., 1983).The defining virulencedeterminantof EHEC

is the phage-encoded Shiga toxin (also known as Verotoxin),

of which there are severalvarieties (O’Loughlin and Robins-

Browne,2001;Melton-Celsa etal.,2012).Although volunteer

studieswith EHEC are prohibited forethicalreasons,vast

quantities of epidemiological data leave no doubt that Shiga t

is responsible for the life-threatening manifestations ofEHEC

infections,namely,HC and the haemolytic uraemic syndrome

(HUS). Evidence supporting a role forShiga toxin in these

conditions include the observation thatinfections with other

bacteria which produce Shiga toxin, such as Shigella dysente

serotype 1 and occasional strains of EAEC,may also cause HC

and HUS (Rohde et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2012).

Not all strains ofShiga toxin-producing E.coli (STEC or

VTEC) cause HC or HUS,and the term “EHEC” is generally

reserved for those that do.Thus,although all EHEC are STEC,

not allSTEC are EHEC.The properties that distinguish EHEC

from those STEC that do not cause HC or HUS are accessory

virulence factorswhich allow the bacteria to adhere to the

intestinal epithelium, such as the LEE pathogenicity island in

called “typicalEHEC” or a number of other adhesins that are

present in LEE-positive and/or LEE-negative strains (reviewed

McWilliams and Torres, 2014).

TypicalEHEC strainsof serotype O157:H7 also generally

carry a virulence-associated plasmid,known as pO157,which

encodes a number of putative virulence determinants (Burlan

et al., 1998).Relatedplasmidsoccur in EHEC of other

serogroups,including O26,O103,O111,and O145 (Ogura

et al.,2009).One ofthe virulence-associated factors encoded

by theseplasmidsis a serum-sensitivehaemolysin,known

as EHEC haemolysinor enterohaemolysin.Many EHEC

isolatesproducethis protein,includingsome that carry

plasmids only distantly related to pO157 (Beutin et al.,1989).

Accordingly, the production of enterohaemolysin can be used

a diagnostic marker of EHEC (Feldsine et al., 2016). Interestin

enterohaemolysin is also produced by some LEE-positive, Shi

toxin-negative strains of E.coli obtained from cattle and sheep

(Cookson etal.,2007).This observation provides evidence of

the evolutionary relationship between atypical EPEC and EHE

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 2 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

ability to colonisetissues.Theseincludetype I fimbriae,

pyelonephritis-associated pili(PAP), and AfA/Dr adhesins in

the case ofUPEC, or the K1 polysaccharide capsule,which

allows NMEC and SEPEC to evade complement-mediated killing

(Pitout, 2012; Leimbach et al., 2013).

The pathotypes of E.colithat are associated with intestinal

disease are known collectively as intestinalpathogenic E.coli

(IPEC) or diarrheagenic E.coli (DEC)—although notall of

the subtypesin this group necessarily cause diarrhoea.The

individualpathotypes of DEC include enteropathogenic E.coli

(EPEC),enteroinvasive E.coli (EIEC), enterotoxigenic E.coli

(ETEC), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enteroaggregative E.

coli(EAEC),diffusely-adherent E.coli(DAEC),and adherent-

invasive E.coli(AIEC) (Nataro and Kaper,1998;Kaper et al.,

2004; Croxen et al., 2013). In addition, the entire genus Shigella

is a DEC pathotype,which closely resemblesEIEC in terms

of virulence attributes and pathogenicity,but is distinguishable

from other strains of E. coli by virtue of its biochemical activity

(Lan etal., 2004).Accordingly,shigellae can be regarded as

members of the EIEC pathotype.

Each DEC pathotype represents a collection ofstrains that

possess similar virulence factors to each other and cause similar

diseases with similar pathology.Unlike ExPEC,where there are

no specific virulence determinants that exclusively define each

subtype,mostDEC pathotypes are defined by the possession

of one or more pathotype-specificvirulencemarkers,and

sometimesby the absence ofothers.Severalof the defining

markers of DEC pathotypes are proven virulence determinants

of that pathotype,but for EAEC,DAEC,and AIEC the role of

these markers in virulence is not proven (Table 1).

DEC PATHOTYPES

In this section,we provide a brief overview of DEC pathotypes

with an emphasison their defining characteristicsand key

virulence determinants (where known). We also point out some

importantgapsin the understanding ofcertain pathotypes.

For more detailed information on DEC in general,readers are

referred to reviews by Nataro and Kaper (1998),Kaper etal.

(2004),Clements et al.(2012),and Croxen et al.(2013).In the

bibliography, we have also included references to review articles

dealing with individual DEC pathotypes.

Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC)

EPEC was the first pathotype of DEC to be discovered, and is an

important cause of diarrhoea and premature death in children,

especially in developing countries (Robins-Browne,1987).As

a group,EPEC is characterised by the presence ofthe locus

of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (McDaniel

and Kaper,1997;Robins-Browne and Hartland,2002;Croxen

et al., 2013). This ∼40-kbp island encodes (i) an outer membrane

adhesive protein,known asintimin thatis encoded by the

eae gene,(ii) a type 3 protein secretory system,(iii) several

type 3-secreted effectors,including the Tir protein which is the

translocated receptor for intimin (Kenny et al., 1997).

Expression of the LEE is associated with distinctive attaching-

effacing lesions in the intestinalepithelium which characterise

EPEC pathology (Moon et al., 1983; Tzipori et al., 1985). Almo

all genes within the LEE are required for the production of

these lesions, and studies in adult volunteers have demonstra

that intimin and EspB,a key componentof the type 3

secretion system,are essentialvirulence determinants of EPEC

(Donnenberg etal., 1993;Tacketet al., 2000).An accessory

virulence determinant,which EPEC also requires for virulence

in humans, is the bundle-forming pilus (BFP) (Girón et al., 199

Bieber et al., 1998). Some human isolates of EPEC naturally la

BFP,but may cause disease (Trabulsi et al.,2002;Nguyen et al.,

2006). These strains, known as atypical EPEC are associated

persistent diarrhoea in children (Nguyen et al.,2006).Atypical

EPEC are genetically diverse and appear to vary in virulence

(Tennant et al., 2009; Ingle et al., 2016a).

Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC)

EHEC first came to attention as the cause oftwo outbreaks

of haemorrhagic colitis (HC) in the USA during 1982 (Riley

et al., 1983).The defining virulencedeterminantof EHEC

is the phage-encoded Shiga toxin (also known as Verotoxin),

of which there are severalvarieties (O’Loughlin and Robins-

Browne,2001;Melton-Celsa etal.,2012).Although volunteer

studieswith EHEC are prohibited forethicalreasons,vast

quantities of epidemiological data leave no doubt that Shiga t

is responsible for the life-threatening manifestations ofEHEC

infections,namely,HC and the haemolytic uraemic syndrome

(HUS). Evidence supporting a role forShiga toxin in these

conditions include the observation thatinfections with other

bacteria which produce Shiga toxin, such as Shigella dysente

serotype 1 and occasional strains of EAEC,may also cause HC

and HUS (Rohde et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2012).

Not all strains ofShiga toxin-producing E.coli (STEC or

VTEC) cause HC or HUS,and the term “EHEC” is generally

reserved for those that do.Thus,although all EHEC are STEC,

not allSTEC are EHEC.The properties that distinguish EHEC

from those STEC that do not cause HC or HUS are accessory

virulence factorswhich allow the bacteria to adhere to the

intestinal epithelium, such as the LEE pathogenicity island in

called “typicalEHEC” or a number of other adhesins that are

present in LEE-positive and/or LEE-negative strains (reviewed

McWilliams and Torres, 2014).

TypicalEHEC strainsof serotype O157:H7 also generally

carry a virulence-associated plasmid,known as pO157,which

encodes a number of putative virulence determinants (Burlan

et al., 1998).Relatedplasmidsoccur in EHEC of other

serogroups,including O26,O103,O111,and O145 (Ogura

et al.,2009).One ofthe virulence-associated factors encoded

by theseplasmidsis a serum-sensitivehaemolysin,known

as EHEC haemolysinor enterohaemolysin.Many EHEC

isolatesproducethis protein,includingsome that carry

plasmids only distantly related to pO157 (Beutin et al.,1989).

Accordingly, the production of enterohaemolysin can be used

a diagnostic marker of EHEC (Feldsine et al., 2016). Interestin

enterohaemolysin is also produced by some LEE-positive, Shi

toxin-negative strains of E.coli obtained from cattle and sheep

(Cookson etal.,2007).This observation provides evidence of

the evolutionary relationship between atypical EPEC and EHE

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 2 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

Robins-Browne et al. E. coliPathotypes

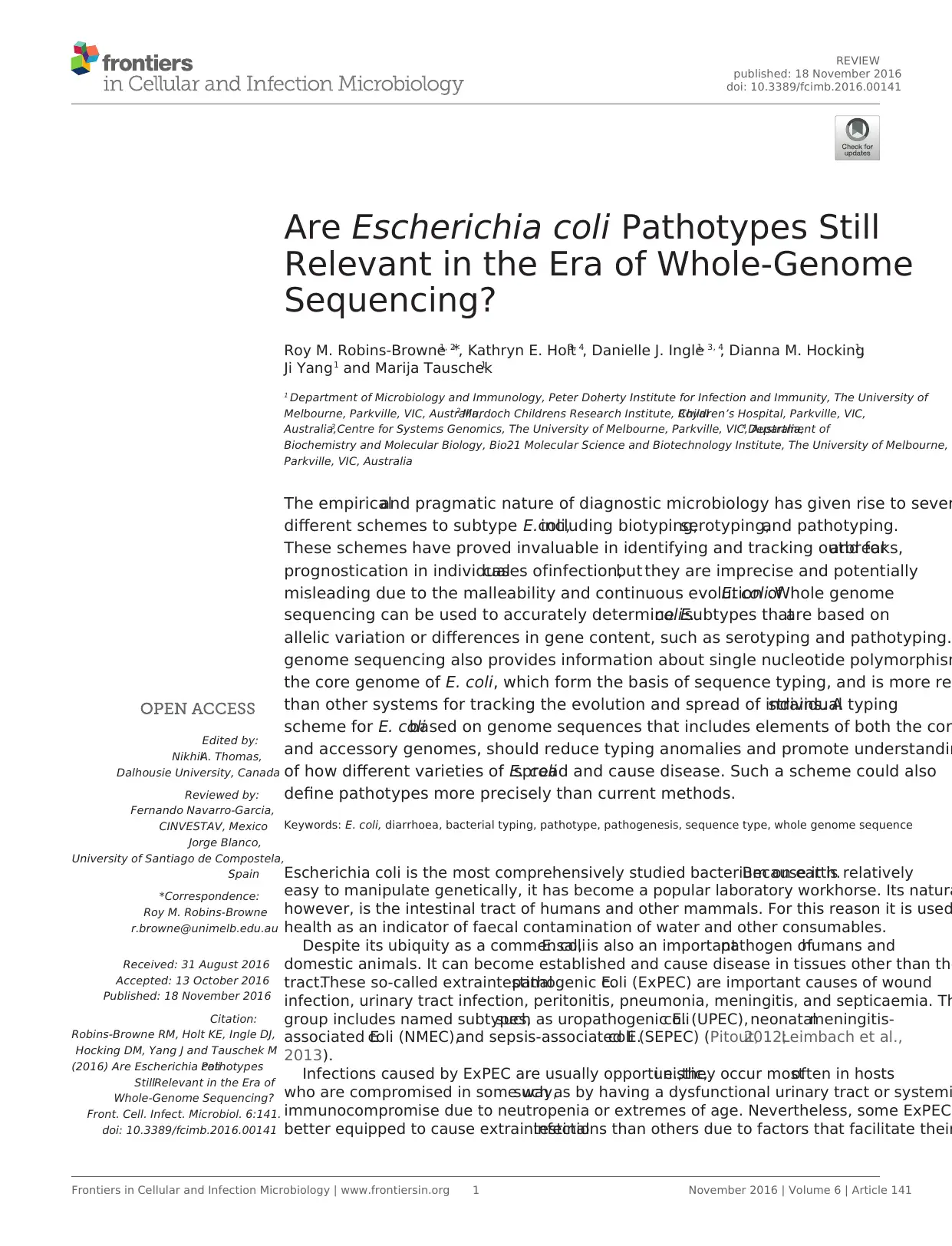

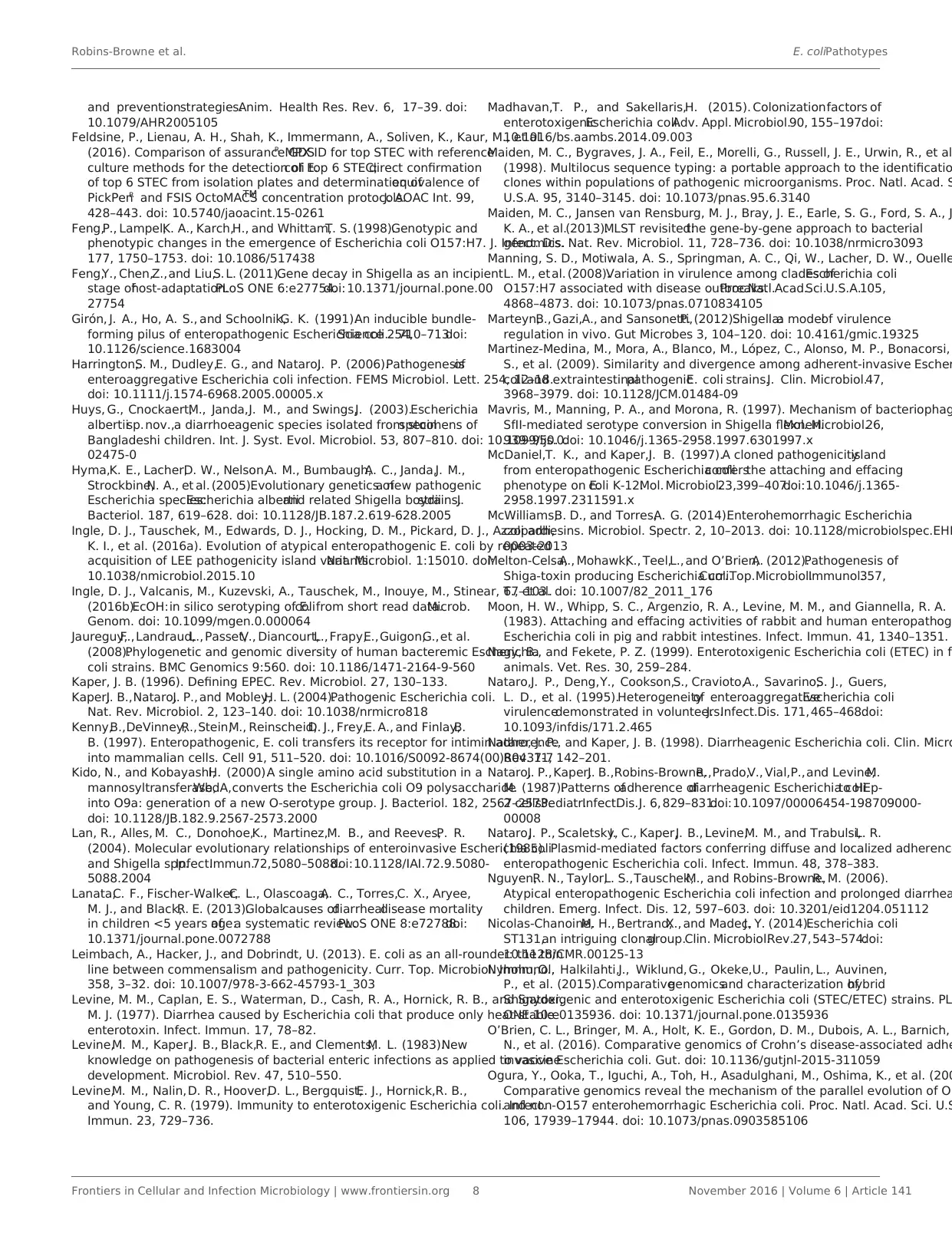

TABLE 1 | Virulence-associated markers of diarrheagenic E. coli from humans.

Pathotype Defining marker Essential virulence

determinant(s)

Location of essential

virulence determinant(s)

Major diagnostic

target(s) for PCR

Other diagnostic

target(s)

EPEC LEE PAI LEE PAI Pathogenicity island eae bfpAa

EIEC/Shigella pINV pINV Plasmid ipaH Other ipa genes

ETEC ST or LT ST and/or LT plus colonisation

factors

Plasmid; transposon elt, est

EHEC Shiga toxin Shiga toxin 1 and/or 2 Prophages stx1, stx2 eaea, ehxAa

EAEC pAA; aggregative adhesion Not known Plasmid (probably); possibly

others

aggR, aatA, aaiC

DAEC Afa/Dr adhesins Not known Not known Afa/Dr adhesinsb

AIEC Adherent-invasive phenotypeNot known Not known none none

aaiC, gene for a secreted protein of enteroaggregative E. coli; aatA, gene for a transporter protein of enteroaggregative E. coli; Afa, afimbrialadhesin; aggR, gene for a transcriptional

regulator; AIEC, adherent-invasive E. coli; bfpA, gene for a structural protein of bundle-forming pili; DAEC, diffusely-adherent E. coli; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; EIEC,

E. coli; elt, gene for heat-labile enterotoxin; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; est, gene for heat-stable enterotoxin; ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; ipaH, gene for a type 3-sec

protein of enteroinvasive E. coliand Shigella; LEE PAI, locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island; LT, heat-labile enterotoxin; pAA, virulence plasmid of enteroaggreg

coli; pINV, virulence plasmid of enteroinvasive E. coliand Shigella; ST, heat-stable enterotoxin.

aNot present in allstrains.

bThese are under review following concerns about specificity.

which is also evident from the high degree of relatedness between

atypicalEPEC strains of serotype O55:H7 and EHEC O157:H7

(Feng et al., 1998).

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)

ETEC is a leading cause of diarrhoea in children in developing

countries and in travellers to these countries (Qadri et al., 2005;

Lanata et al., 2013). ETEC is also an important cause of diarrhoea

in domestic animals,notably calves and piglets,where ETEC-

induced diarrhoea is of considerable economic importance (Nagy

and Fekete, 1999; Fairbrother et al., 2005).

As the name suggests,the ETEC pathotype is defined by the

capacity of the bacteria to produce one or more enterotoxins. In

ETEC the specific enterotoxins are the heat-labile and heat-stable

enterotoxins (LT and ST) and their various subtypes (Qadri et al.,

2005). The two major subtypes of ST are STa (also known as STI)

and Stb (STII), of which only STa is important in humans (Qadri

et al.,2005;Taxt et al.,2010).Most ETEC strains isolated from

humans with diarrhoea produce STa, often together with LT. The

role ofeach ofthese toxins in disease has been established in

volunteer studies (Levine et al., 1977, 1979).

Both ST and LT exert their maximum impact on water and

electrolyte transport in the smallintestine.In order to deliver

thesetoxinsto the smallintestinalepithelium,ETEC need

to attach to epithelialcells,which they achieve by means of

specific colonisation factors (Qadriet al.,2005;Madhavan and

Sakellaris,2015).These factors are highly variable structurally

and antigenically, and also differ between isolates from humans

and animals. In several instances, the role of colonisation factors

as accessory virulencedeterminantshas been demonstrated

experimentally (Qadriet al., 2005;Madhavan and Sakellaris,

2015).

Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC)

EIEC are closely related to Shigella,especially in termsof

the disease they cause,i.e.,bacillary dysentery,and their key

virulence determinant: a plasmid known as pINV. This plasmid

encodes a type 3 secretion system and a number of effectors

allow shigellae/EIEC to penetrate epithelialcells,move within

these cells and invade neighbouring cells (Marteyn et al., 2012).

Both shigellae and EIEC carry severalother putative virulence

determinants including adhesins and secreted toxins, but pIN

which appears to be restricted to these bacteria, is the key to

virulence (Marteyn et al., 2012; Croxen et al., 2013).

EIEC and shigellae exemplify the changes thatE. coli can

make to adjust to a pathogenic lifestyle (Day et al., 2001). Th

by acquiring pINV,and other genetic elements thatallow the

bacteria to adopt an intracellular lifestyle, the capacity of E. c

to live inside cells is continuously enhanced by the deletion o

inactivation of genes that are inimical to this lifestyle (Day et

2001;Feng et al.,2011;Prosseda et al.,2012).Examples of such

genes include some that encode anti-virulence factors,such as

nadA,nadB,and ompT,and those for metabolic pathways such

as lysine decarboxylation,the end products ofwhich restrict

intracellulargrowth (Day etal., 2001;Prunieret al., 2007).

Moreover,since flagella are not required for colonisation of the

large intestine or for motility within cells, all shigellae and ma

strains of EIEC are non-motile. The capacity of E. coli to adapt

new environments in this way provides fascinating insights in

the extraordinary versatility of this species as a pathogen.

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC)

This relatively recently discovered E.colipathotype is mainly

associated with paediatric diarrhoea in developing countries,

has also been linked to diarrhoea in adults,including travellers

(Okeke and Nataro,2001;Harrington et al.,2006).EAEC was

originally identified by its characteristic “stacked-brick” patte

of adherenceto tissueculturecellsin vitro (Nataro etal.,

1987; Figure 1). This phenotype is attributable to one of sev

differenthydrophobic aggregative fimbriae,known as AAF/I,

AAF/II, AAF/III, and AAF/IV, encoded by pAA orsimilar

plasmids.Other putative virulence factors of EAEC include (i)

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 3 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

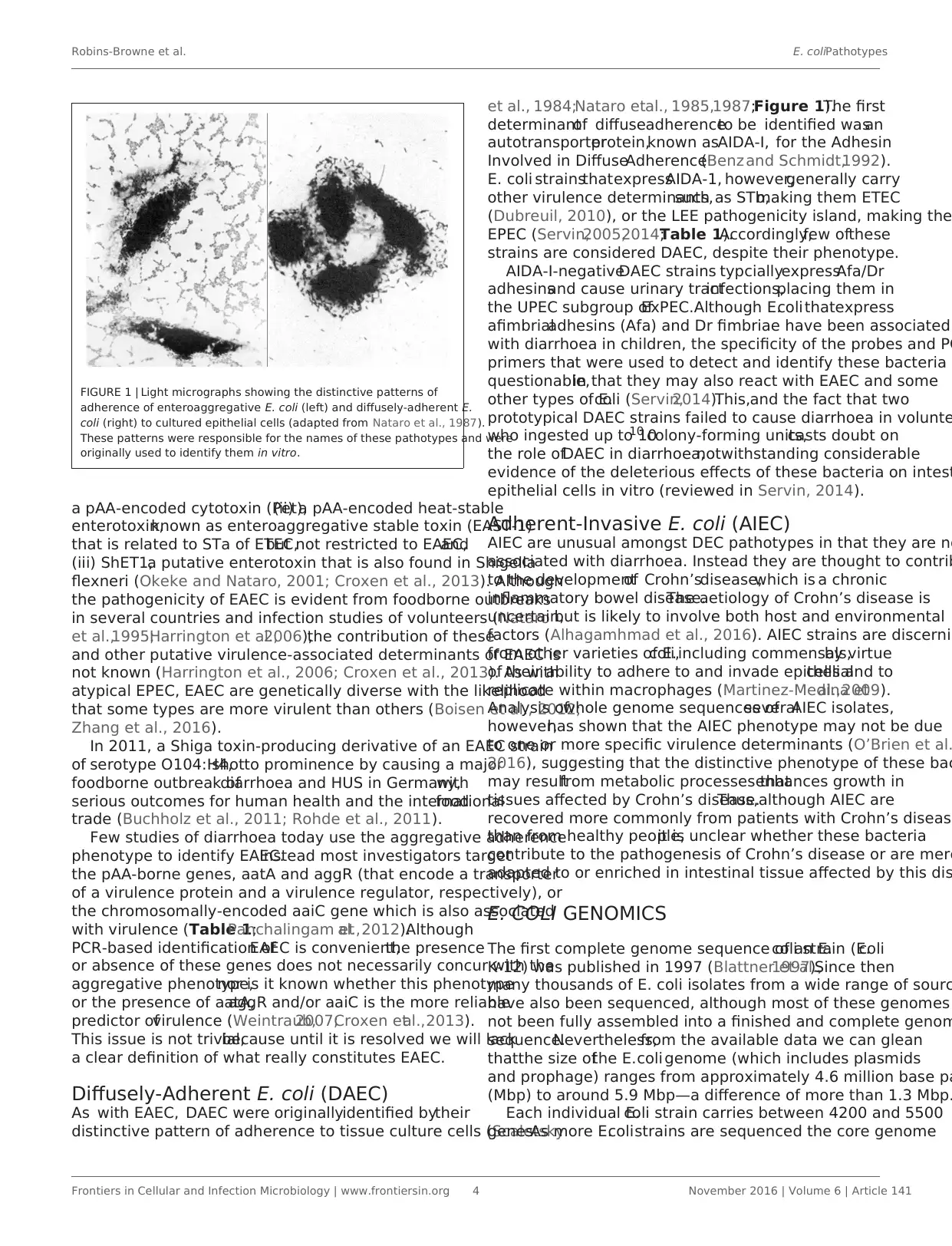

TABLE 1 | Virulence-associated markers of diarrheagenic E. coli from humans.

Pathotype Defining marker Essential virulence

determinant(s)

Location of essential

virulence determinant(s)

Major diagnostic

target(s) for PCR

Other diagnostic

target(s)

EPEC LEE PAI LEE PAI Pathogenicity island eae bfpAa

EIEC/Shigella pINV pINV Plasmid ipaH Other ipa genes

ETEC ST or LT ST and/or LT plus colonisation

factors

Plasmid; transposon elt, est

EHEC Shiga toxin Shiga toxin 1 and/or 2 Prophages stx1, stx2 eaea, ehxAa

EAEC pAA; aggregative adhesion Not known Plasmid (probably); possibly

others

aggR, aatA, aaiC

DAEC Afa/Dr adhesins Not known Not known Afa/Dr adhesinsb

AIEC Adherent-invasive phenotypeNot known Not known none none

aaiC, gene for a secreted protein of enteroaggregative E. coli; aatA, gene for a transporter protein of enteroaggregative E. coli; Afa, afimbrialadhesin; aggR, gene for a transcriptional

regulator; AIEC, adherent-invasive E. coli; bfpA, gene for a structural protein of bundle-forming pili; DAEC, diffusely-adherent E. coli; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; EIEC,

E. coli; elt, gene for heat-labile enterotoxin; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; est, gene for heat-stable enterotoxin; ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; ipaH, gene for a type 3-sec

protein of enteroinvasive E. coliand Shigella; LEE PAI, locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island; LT, heat-labile enterotoxin; pAA, virulence plasmid of enteroaggreg

coli; pINV, virulence plasmid of enteroinvasive E. coliand Shigella; ST, heat-stable enterotoxin.

aNot present in allstrains.

bThese are under review following concerns about specificity.

which is also evident from the high degree of relatedness between

atypicalEPEC strains of serotype O55:H7 and EHEC O157:H7

(Feng et al., 1998).

Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)

ETEC is a leading cause of diarrhoea in children in developing

countries and in travellers to these countries (Qadri et al., 2005;

Lanata et al., 2013). ETEC is also an important cause of diarrhoea

in domestic animals,notably calves and piglets,where ETEC-

induced diarrhoea is of considerable economic importance (Nagy

and Fekete, 1999; Fairbrother et al., 2005).

As the name suggests,the ETEC pathotype is defined by the

capacity of the bacteria to produce one or more enterotoxins. In

ETEC the specific enterotoxins are the heat-labile and heat-stable

enterotoxins (LT and ST) and their various subtypes (Qadri et al.,

2005). The two major subtypes of ST are STa (also known as STI)

and Stb (STII), of which only STa is important in humans (Qadri

et al.,2005;Taxt et al.,2010).Most ETEC strains isolated from

humans with diarrhoea produce STa, often together with LT. The

role ofeach ofthese toxins in disease has been established in

volunteer studies (Levine et al., 1977, 1979).

Both ST and LT exert their maximum impact on water and

electrolyte transport in the smallintestine.In order to deliver

thesetoxinsto the smallintestinalepithelium,ETEC need

to attach to epithelialcells,which they achieve by means of

specific colonisation factors (Qadriet al.,2005;Madhavan and

Sakellaris,2015).These factors are highly variable structurally

and antigenically, and also differ between isolates from humans

and animals. In several instances, the role of colonisation factors

as accessory virulencedeterminantshas been demonstrated

experimentally (Qadriet al., 2005;Madhavan and Sakellaris,

2015).

Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC)

EIEC are closely related to Shigella,especially in termsof

the disease they cause,i.e.,bacillary dysentery,and their key

virulence determinant: a plasmid known as pINV. This plasmid

encodes a type 3 secretion system and a number of effectors

allow shigellae/EIEC to penetrate epithelialcells,move within

these cells and invade neighbouring cells (Marteyn et al., 2012).

Both shigellae and EIEC carry severalother putative virulence

determinants including adhesins and secreted toxins, but pIN

which appears to be restricted to these bacteria, is the key to

virulence (Marteyn et al., 2012; Croxen et al., 2013).

EIEC and shigellae exemplify the changes thatE. coli can

make to adjust to a pathogenic lifestyle (Day et al., 2001). Th

by acquiring pINV,and other genetic elements thatallow the

bacteria to adopt an intracellular lifestyle, the capacity of E. c

to live inside cells is continuously enhanced by the deletion o

inactivation of genes that are inimical to this lifestyle (Day et

2001;Feng et al.,2011;Prosseda et al.,2012).Examples of such

genes include some that encode anti-virulence factors,such as

nadA,nadB,and ompT,and those for metabolic pathways such

as lysine decarboxylation,the end products ofwhich restrict

intracellulargrowth (Day etal., 2001;Prunieret al., 2007).

Moreover,since flagella are not required for colonisation of the

large intestine or for motility within cells, all shigellae and ma

strains of EIEC are non-motile. The capacity of E. coli to adapt

new environments in this way provides fascinating insights in

the extraordinary versatility of this species as a pathogen.

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC)

This relatively recently discovered E.colipathotype is mainly

associated with paediatric diarrhoea in developing countries,

has also been linked to diarrhoea in adults,including travellers

(Okeke and Nataro,2001;Harrington et al.,2006).EAEC was

originally identified by its characteristic “stacked-brick” patte

of adherenceto tissueculturecellsin vitro (Nataro etal.,

1987; Figure 1). This phenotype is attributable to one of sev

differenthydrophobic aggregative fimbriae,known as AAF/I,

AAF/II, AAF/III, and AAF/IV, encoded by pAA orsimilar

plasmids.Other putative virulence factors of EAEC include (i)

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 3 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Robins-Browne et al. E. coliPathotypes

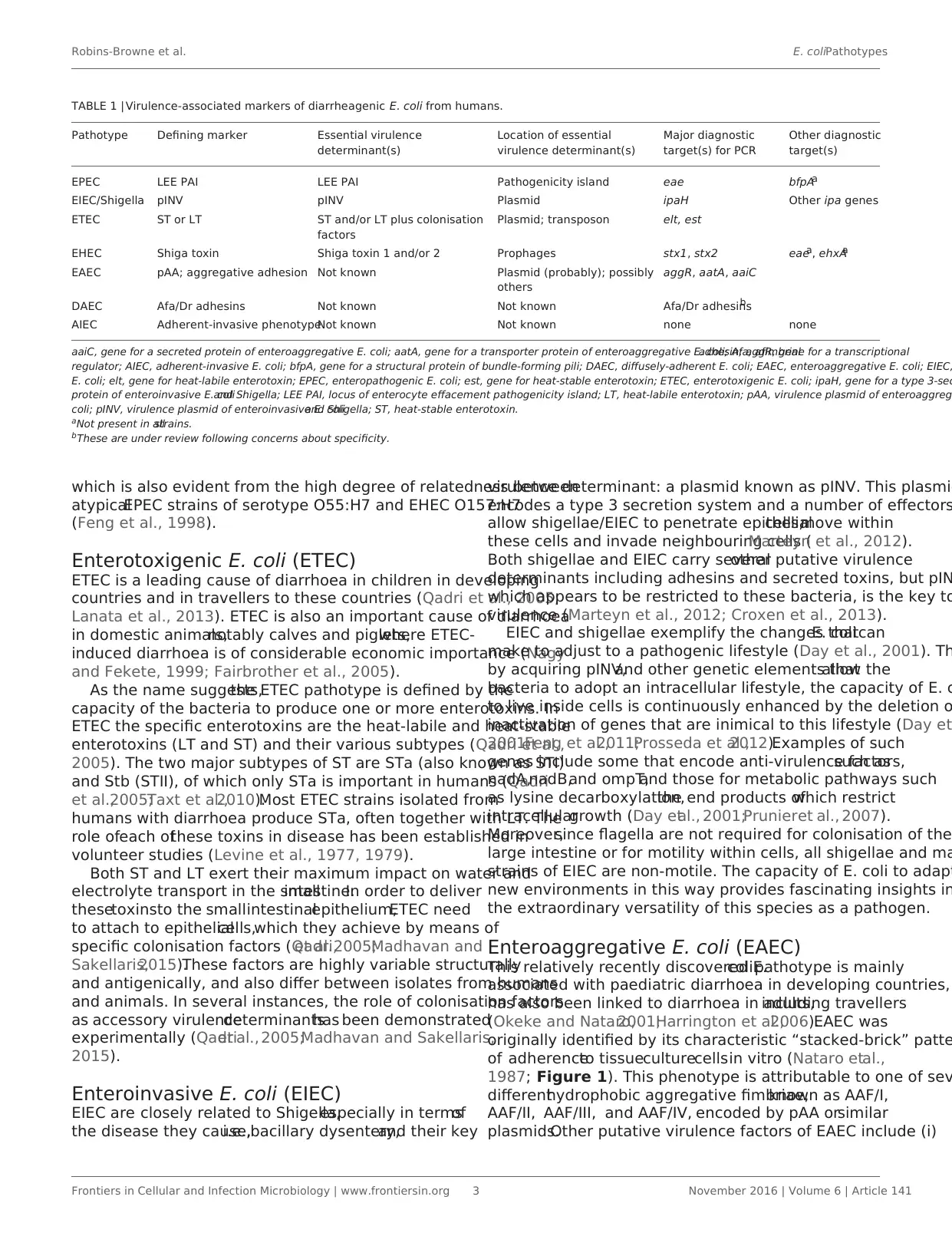

FIGURE 1 | Light micrographs showing the distinctive patterns of

adherence of enteroaggregative E. coli (left) and diffusely-adherent E.

coli (right) to cultured epithelial cells (adapted from Nataro et al., 1987).

These patterns were responsible for the names of these pathotypes and were

originally used to identify them in vitro.

a pAA-encoded cytotoxin (Pet),(ii) a pAA-encoded heat-stable

enterotoxin,known as enteroaggregative stable toxin (EAST-1)

that is related to STa of ETEC,but not restricted to EAEC,and

(iii) ShET1,a putative enterotoxin that is also found in Shigella

flexneri (Okeke and Nataro, 2001; Croxen et al., 2013). Although

the pathogenicity of EAEC is evident from foodborne outbreaks

in several countries and infection studies of volunteers (Nataro

et al.,1995;Harrington et al.,2006),the contribution of these

and other putative virulence-associated determinants of EAEC is

not known (Harrington et al., 2006; Croxen et al., 2013). As with

atypical EPEC, EAEC are genetically diverse with the likelihood

that some types are more virulent than others (Boisen et al., 2012;

Zhang et al., 2016).

In 2011, a Shiga toxin-producing derivative of an EAEC strain

of serotype O104:H4,shotto prominence by causing a major

foodborne outbreak ofdiarrhoea and HUS in Germany,with

serious outcomes for human health and the internationalfood

trade (Buchholz et al., 2011; Rohde et al., 2011).

Few studies of diarrhoea today use the aggregative adherence

phenotype to identify EAEC.Instead most investigators target

the pAA-borne genes, aatA and aggR (that encode a transporter

of a virulence protein and a virulence regulator, respectively), or

the chromosomally-encoded aaiC gene which is also associated

with virulence (Table 1;Panchalingam etal.,2012).Although

PCR-based identification ofEAEC is convenient,the presence

or absence of these genes does not necessarily concur with the

aggregative phenotype,nor is it known whether this phenotype

or the presence of aatA,aggR and/or aaiC is the more reliable

predictor ofvirulence (Weintraub,2007;Croxen etal.,2013).

This issue is not trivial,because until it is resolved we will lack

a clear definition of what really constitutes EAEC.

Diffusely-Adherent E. coli (DAEC)

As with EAEC, DAEC were originallyidentified bytheir

distinctive pattern of adherence to tissue culture cells (Scaletsky

et al., 1984;Nataro etal., 1985,1987;Figure 1).The first

determinantof diffuseadherenceto be identified wasan

autotransporterprotein,known asAIDA-I, for the Adhesin

Involved in DiffuseAdherence(Benz and Schmidt,1992).

E. coli strainsthatexpressAIDA-1, however,generally carry

other virulence determinants,such as STb,making them ETEC

(Dubreuil, 2010), or the LEE pathogenicity island, making the

EPEC (Servin,2005,2014;Table 1).Accordingly,few ofthese

strains are considered DAEC, despite their phenotype.

AIDA-I-negativeDAEC strains typciallyexpressAfa/Dr

adhesinsand cause urinary tractinfections,placing them in

the UPEC subgroup ofExPEC.Although E.coli thatexpress

afimbrialadhesins (Afa) and Dr fimbriae have been associated

with diarrhoea in children, the specificity of the probes and PC

primers that were used to detect and identify these bacteria

questionable,in that they may also react with EAEC and some

other types of E.coli (Servin,2014).This,and the fact that two

prototypical DAEC strains failed to cause diarrhoea in volunte

who ingested up to 1010 colony-forming units,casts doubt on

the role ofDAEC in diarrhoea,notwithstanding considerable

evidence of the deleterious effects of these bacteria on intest

epithelial cells in vitro (reviewed in Servin, 2014).

Adherent-Invasive E. coli (AIEC)

AIEC are unusual amongst DEC pathotypes in that they are no

associated with diarrhoea. Instead they are thought to contrib

to the developmentof Crohn’sdisease,which is a chronic

inflammatory bowel disease.The aetiology of Crohn’s disease is

uncertain,but is likely to involve both host and environmental

factors (Alhagamhmad et al., 2016). AIEC strains are discernib

from other varieties of E.coli,including commensals,by virtue

of their ability to adhere to and invade epithelialcells and to

replicate within macrophages (Martinez-Medina etal.,2009).

Analysis ofwhole genome sequences ofseveralAIEC isolates,

however,has shown that the AIEC phenotype may not be due

to one or more specific virulence determinants (O’Brien et al.

2016), suggesting that the distinctive phenotype of these bac

may resultfrom metabolic processes thatenhances growth in

tissues affected by Crohn’s disease.Thus,although AIEC are

recovered more commonly from patients with Crohn’s diseas

than from healthy people,it is unclear whether these bacteria

contribute to the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease or are mere

adapted to or enriched in intestinal tissue affected by this dis

E. COLI GENOMICS

The first complete genome sequence of an E.coli strain (E.coli

K-12) was published in 1997 (Blattner et al.,1997).Since then

many thousands of E. coli isolates from a wide range of sourc

have also been sequenced, although most of these genomes

not been fully assembled into a finished and complete genom

sequence.Nevertheless,from the available data we can glean

thatthe size ofthe E.coli genome (which includes plasmids

and prophage) ranges from approximately 4.6 million base pa

(Mbp) to around 5.9 Mbp—a difference of more than 1.3 Mbp.

Each individual E.coli strain carries between 4200 and 5500

genes.As more E.colistrains are sequenced the core genome

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 4 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

FIGURE 1 | Light micrographs showing the distinctive patterns of

adherence of enteroaggregative E. coli (left) and diffusely-adherent E.

coli (right) to cultured epithelial cells (adapted from Nataro et al., 1987).

These patterns were responsible for the names of these pathotypes and were

originally used to identify them in vitro.

a pAA-encoded cytotoxin (Pet),(ii) a pAA-encoded heat-stable

enterotoxin,known as enteroaggregative stable toxin (EAST-1)

that is related to STa of ETEC,but not restricted to EAEC,and

(iii) ShET1,a putative enterotoxin that is also found in Shigella

flexneri (Okeke and Nataro, 2001; Croxen et al., 2013). Although

the pathogenicity of EAEC is evident from foodborne outbreaks

in several countries and infection studies of volunteers (Nataro

et al.,1995;Harrington et al.,2006),the contribution of these

and other putative virulence-associated determinants of EAEC is

not known (Harrington et al., 2006; Croxen et al., 2013). As with

atypical EPEC, EAEC are genetically diverse with the likelihood

that some types are more virulent than others (Boisen et al., 2012;

Zhang et al., 2016).

In 2011, a Shiga toxin-producing derivative of an EAEC strain

of serotype O104:H4,shotto prominence by causing a major

foodborne outbreak ofdiarrhoea and HUS in Germany,with

serious outcomes for human health and the internationalfood

trade (Buchholz et al., 2011; Rohde et al., 2011).

Few studies of diarrhoea today use the aggregative adherence

phenotype to identify EAEC.Instead most investigators target

the pAA-borne genes, aatA and aggR (that encode a transporter

of a virulence protein and a virulence regulator, respectively), or

the chromosomally-encoded aaiC gene which is also associated

with virulence (Table 1;Panchalingam etal.,2012).Although

PCR-based identification ofEAEC is convenient,the presence

or absence of these genes does not necessarily concur with the

aggregative phenotype,nor is it known whether this phenotype

or the presence of aatA,aggR and/or aaiC is the more reliable

predictor ofvirulence (Weintraub,2007;Croxen etal.,2013).

This issue is not trivial,because until it is resolved we will lack

a clear definition of what really constitutes EAEC.

Diffusely-Adherent E. coli (DAEC)

As with EAEC, DAEC were originallyidentified bytheir

distinctive pattern of adherence to tissue culture cells (Scaletsky

et al., 1984;Nataro etal., 1985,1987;Figure 1).The first

determinantof diffuseadherenceto be identified wasan

autotransporterprotein,known asAIDA-I, for the Adhesin

Involved in DiffuseAdherence(Benz and Schmidt,1992).

E. coli strainsthatexpressAIDA-1, however,generally carry

other virulence determinants,such as STb,making them ETEC

(Dubreuil, 2010), or the LEE pathogenicity island, making the

EPEC (Servin,2005,2014;Table 1).Accordingly,few ofthese

strains are considered DAEC, despite their phenotype.

AIDA-I-negativeDAEC strains typciallyexpressAfa/Dr

adhesinsand cause urinary tractinfections,placing them in

the UPEC subgroup ofExPEC.Although E.coli thatexpress

afimbrialadhesins (Afa) and Dr fimbriae have been associated

with diarrhoea in children, the specificity of the probes and PC

primers that were used to detect and identify these bacteria

questionable,in that they may also react with EAEC and some

other types of E.coli (Servin,2014).This,and the fact that two

prototypical DAEC strains failed to cause diarrhoea in volunte

who ingested up to 1010 colony-forming units,casts doubt on

the role ofDAEC in diarrhoea,notwithstanding considerable

evidence of the deleterious effects of these bacteria on intest

epithelial cells in vitro (reviewed in Servin, 2014).

Adherent-Invasive E. coli (AIEC)

AIEC are unusual amongst DEC pathotypes in that they are no

associated with diarrhoea. Instead they are thought to contrib

to the developmentof Crohn’sdisease,which is a chronic

inflammatory bowel disease.The aetiology of Crohn’s disease is

uncertain,but is likely to involve both host and environmental

factors (Alhagamhmad et al., 2016). AIEC strains are discernib

from other varieties of E.coli,including commensals,by virtue

of their ability to adhere to and invade epithelialcells and to

replicate within macrophages (Martinez-Medina etal.,2009).

Analysis ofwhole genome sequences ofseveralAIEC isolates,

however,has shown that the AIEC phenotype may not be due

to one or more specific virulence determinants (O’Brien et al.

2016), suggesting that the distinctive phenotype of these bac

may resultfrom metabolic processes thatenhances growth in

tissues affected by Crohn’s disease.Thus,although AIEC are

recovered more commonly from patients with Crohn’s diseas

than from healthy people,it is unclear whether these bacteria

contribute to the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease or are mere

adapted to or enriched in intestinal tissue affected by this dis

E. COLI GENOMICS

The first complete genome sequence of an E.coli strain (E.coli

K-12) was published in 1997 (Blattner et al.,1997).Since then

many thousands of E. coli isolates from a wide range of sourc

have also been sequenced, although most of these genomes

not been fully assembled into a finished and complete genom

sequence.Nevertheless,from the available data we can glean

thatthe size ofthe E.coli genome (which includes plasmids

and prophage) ranges from approximately 4.6 million base pa

(Mbp) to around 5.9 Mbp—a difference of more than 1.3 Mbp.

Each individual E.coli strain carries between 4200 and 5500

genes.As more E.colistrains are sequenced the core genome

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 4 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Robins-Browne et al. E. coliPathotypes

(i.e.,the backbone ofchromosomalgenes thatare presentin

every E.coli strain)shrinks.The size of the core genome

currently stands at fewer than 1500 genes and willto continue

to diminish, albeit slowly, as more strains are sequenced. Genes

thatare notpartof the core are referred to as the accessory

genome. These include all of the genes that encode bacteriophage

elements,virulence determinantsand acquired resistance to

antimicrobials.The E. coli pangenome—the totalnumberof

unique genes that have been identified in E. coli—comprises more

than 22,000 and willcontinue to increase as more strains are

sequenced.

All of the genesfor E. coli virulence determinantswere

mostlikely acquired by horizontalgene transferfrom other

bacteria via plasmids, bacteriophages, pathogenicity islands, and

transposons (Leimbach et al., 2013; Table 1). Thus, every E. coli

strain comprises a mosaic ofcore and accessory genes,with

almost allof the latter,including the virulence determinants of

DEC, being transmissible between strains. For these reasons, it is

inevitable that new pathotypes of DEC will continue to emerge,

either through novel assemblies of E. coli virulence determinants,

as in the case ofEHEC (Feng etal.,1998) and Shiga toxin-

producing EAEC (Rohde et al., 2011), or through the acquisition

of virulence genes from other bacterial species.

E. COLI SUBTYPES

Apart from pathotype,individualstrainsof E. coli can be

subtyped using a variety ofcriteria thatmay vary between

individualstrains.These includesequencetype, serotype,

pulsotype, phage type, and biotype.

Sequence Type

The conserved natureof the E. coli core genomeallows

determination ofthe genetic distance between strainsbased

on nucleotidepolymorphismsin shared genes.For more

than a decade multi-locus sequence typing (MLST),in which

sequence types (STs) are defined on the basis of combinations

of allelicvariation in 6–11 so-called “housekeepinggenes”

(Maiden etal., 1998),hasbeen the gold standard forDNA

sequence-based typing ofbacterialpathogens.ThreeMLST

schemeshavebeen proposed forE. coli, each based on a

differentset of 7–8 genes(Reid et al., 2000;Wirth et al.,

2006;Jaureguy etal.,2008),of which the 7-locus scheme of

Mark Achtman appears to be the moststable and congruent

with whole genome phylogenies (Chaudhuriand Henderson,

2012;Clermontet al., 2015).The principleof MLST has

recently been extended to core gene MLST (cgMLST) (Maiden

et al., 2013),and a new E. coli schemeincorporating

more than 2500genesis now available(alongsidethe 7-

locus scheme ofMark Achtman)in the Enterobase database

hostedat the Warwick Medical School (http://enterobase.

warwick.ac.uk).Sequence typing hasproved usefulin many

settings,e.g.,in tracing thespread ofparticularstrainsin

differentregions,such as E.coliST131,a multidrug resistant

UPEC clone (Nicolas-Chanoineet al., 2014;Petty et al.,

2014).

Serotype

Serotypingbased on antigenicvariation in thesurfaceO-

(polysaccharide)and H- (flagella)antigensof E. coli was

previouslyused for the preliminaryidentification ofDEC

pathotypes. Indeed, much of the early evidence linking EPEC

the cause of outbreaks of diarrhoea was based on the antigen

relatedness of strains obtained from patients in different loca

(Robins-Browne,1987).ETEC, EIEC, EHEC, and EAEC also

belong to a limited number of serotypes,but serotyping is no

longer used for the preliminary identification of these categor

having been replaced by directtesting forthe presenceof

virulence-associated genes (Table 1). Moreover, E. coli serot

are not immutable,and can change due to mutation or phage-

mediated transduction (Mavris et al., 1997; Kido and Kobayas

2000).The superiority ofsequence typing over serotyping is

illustrated by the ST131 UPEC pandemic strain,in which most

isolates are serotype O25b:H4,butsome are serotype O16:H5

(Nicolas-Chanoine etal.,2014).Importantly,E. coliserotypes

can be reliably predicted from whole genome sequences (Ing

et al., 2016b).Indeed,in-silico serotyping offersa number

of advantages over traditionalserotyping,including the non-

reliance on typing sera that may vary in quality,and the ability

to type strains that do not express the O- or H-antigens in vit

or that autoagglutinate (Ingle et al.,2016b).For these reasons,

in-silico serotyping is likely to replace traditionalserotyping in

future.

Nevertheless, many food microbiology laboratories current

use serotyping for the preliminary identification of EHEC, mos

notably E.coli O157:H7 and the so-called “big six” serogroups

(O26,O45,O103,O111,O121,and O145)of EHEC strains

(Brooks et al., 2005).

Interestingly,even the identification ofserotype,together

with the demonstration ofa suite ofshared virulence genes,

may notprovide sufficiently refined information to identify a

particular subclone or clade ofEHEC (Manning etal.,2008).

In such instances,further subtyping may be required to track

outbreaks.Traditionally,this has included phage typing (which

is based on the susceptibility ofisolates to infection with one

or more specific virulentbacteriophages)or typing based on

restriction fragment length polymorphism (pulsotyping),which

permits the discernment of outbreak strains from background

“noise”(Benderet al., 1997).The valueof pulsotypingis

exemplified byPulseNet,a surveillancenetworkof public

health laboratories thatuse DNA fingerprinting for the early

identification ofcommon sourcesof foodborne outbreaksof

disease (Swaminathan et al., 2001). More recently, public hea

laboratories have been shifting to analysis of whole genome s

nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to trace outbreaks of E.coli

and other foodborne pathogens.This approach firstcaptured

the attention ofthe internationalpublichealth community

during the high-profile 2011 outbreak ofdiarrhoea and HUS

in Germany caused by Shiga toxin producing EAEC (Buchholz

et al., 2011; Rohde et al., 2011), and is now being used for ro

analysis in many laboratories, e.g., to investigate E. coli O157

outbreaks by Public Health England (Cowley et al.,2016),and

the GenomeTrakr project established by the US Food and Dru

Administration (Allard et al., 2016).

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 5 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

(i.e.,the backbone ofchromosomalgenes thatare presentin

every E.coli strain)shrinks.The size of the core genome

currently stands at fewer than 1500 genes and willto continue

to diminish, albeit slowly, as more strains are sequenced. Genes

thatare notpartof the core are referred to as the accessory

genome. These include all of the genes that encode bacteriophage

elements,virulence determinantsand acquired resistance to

antimicrobials.The E. coli pangenome—the totalnumberof

unique genes that have been identified in E. coli—comprises more

than 22,000 and willcontinue to increase as more strains are

sequenced.

All of the genesfor E. coli virulence determinantswere

mostlikely acquired by horizontalgene transferfrom other

bacteria via plasmids, bacteriophages, pathogenicity islands, and

transposons (Leimbach et al., 2013; Table 1). Thus, every E. coli

strain comprises a mosaic ofcore and accessory genes,with

almost allof the latter,including the virulence determinants of

DEC, being transmissible between strains. For these reasons, it is

inevitable that new pathotypes of DEC will continue to emerge,

either through novel assemblies of E. coli virulence determinants,

as in the case ofEHEC (Feng etal.,1998) and Shiga toxin-

producing EAEC (Rohde et al., 2011), or through the acquisition

of virulence genes from other bacterial species.

E. COLI SUBTYPES

Apart from pathotype,individualstrainsof E. coli can be

subtyped using a variety ofcriteria thatmay vary between

individualstrains.These includesequencetype, serotype,

pulsotype, phage type, and biotype.

Sequence Type

The conserved natureof the E. coli core genomeallows

determination ofthe genetic distance between strainsbased

on nucleotidepolymorphismsin shared genes.For more

than a decade multi-locus sequence typing (MLST),in which

sequence types (STs) are defined on the basis of combinations

of allelicvariation in 6–11 so-called “housekeepinggenes”

(Maiden etal., 1998),hasbeen the gold standard forDNA

sequence-based typing ofbacterialpathogens.ThreeMLST

schemeshavebeen proposed forE. coli, each based on a

differentset of 7–8 genes(Reid et al., 2000;Wirth et al.,

2006;Jaureguy etal.,2008),of which the 7-locus scheme of

Mark Achtman appears to be the moststable and congruent

with whole genome phylogenies (Chaudhuriand Henderson,

2012;Clermontet al., 2015).The principleof MLST has

recently been extended to core gene MLST (cgMLST) (Maiden

et al., 2013),and a new E. coli schemeincorporating

more than 2500genesis now available(alongsidethe 7-

locus scheme ofMark Achtman)in the Enterobase database

hostedat the Warwick Medical School (http://enterobase.

warwick.ac.uk).Sequence typing hasproved usefulin many

settings,e.g.,in tracing thespread ofparticularstrainsin

differentregions,such as E.coliST131,a multidrug resistant

UPEC clone (Nicolas-Chanoineet al., 2014;Petty et al.,

2014).

Serotype

Serotypingbased on antigenicvariation in thesurfaceO-

(polysaccharide)and H- (flagella)antigensof E. coli was

previouslyused for the preliminaryidentification ofDEC

pathotypes. Indeed, much of the early evidence linking EPEC

the cause of outbreaks of diarrhoea was based on the antigen

relatedness of strains obtained from patients in different loca

(Robins-Browne,1987).ETEC, EIEC, EHEC, and EAEC also

belong to a limited number of serotypes,but serotyping is no

longer used for the preliminary identification of these categor

having been replaced by directtesting forthe presenceof

virulence-associated genes (Table 1). Moreover, E. coli serot

are not immutable,and can change due to mutation or phage-

mediated transduction (Mavris et al., 1997; Kido and Kobayas

2000).The superiority ofsequence typing over serotyping is

illustrated by the ST131 UPEC pandemic strain,in which most

isolates are serotype O25b:H4,butsome are serotype O16:H5

(Nicolas-Chanoine etal.,2014).Importantly,E. coliserotypes

can be reliably predicted from whole genome sequences (Ing

et al., 2016b).Indeed,in-silico serotyping offersa number

of advantages over traditionalserotyping,including the non-

reliance on typing sera that may vary in quality,and the ability

to type strains that do not express the O- or H-antigens in vit

or that autoagglutinate (Ingle et al.,2016b).For these reasons,

in-silico serotyping is likely to replace traditionalserotyping in

future.

Nevertheless, many food microbiology laboratories current

use serotyping for the preliminary identification of EHEC, mos

notably E.coli O157:H7 and the so-called “big six” serogroups

(O26,O45,O103,O111,O121,and O145)of EHEC strains

(Brooks et al., 2005).

Interestingly,even the identification ofserotype,together

with the demonstration ofa suite ofshared virulence genes,

may notprovide sufficiently refined information to identify a

particular subclone or clade ofEHEC (Manning etal.,2008).

In such instances,further subtyping may be required to track

outbreaks.Traditionally,this has included phage typing (which

is based on the susceptibility ofisolates to infection with one

or more specific virulentbacteriophages)or typing based on

restriction fragment length polymorphism (pulsotyping),which

permits the discernment of outbreak strains from background

“noise”(Benderet al., 1997).The valueof pulsotypingis

exemplified byPulseNet,a surveillancenetworkof public

health laboratories thatuse DNA fingerprinting for the early

identification ofcommon sourcesof foodborne outbreaksof

disease (Swaminathan et al., 2001). More recently, public hea

laboratories have been shifting to analysis of whole genome s

nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to trace outbreaks of E.coli

and other foodborne pathogens.This approach firstcaptured

the attention ofthe internationalpublichealth community

during the high-profile 2011 outbreak ofdiarrhoea and HUS

in Germany caused by Shiga toxin producing EAEC (Buchholz

et al., 2011; Rohde et al., 2011), and is now being used for ro

analysis in many laboratories, e.g., to investigate E. coli O157

outbreaks by Public Health England (Cowley et al.,2016),and

the GenomeTrakr project established by the US Food and Dru

Administration (Allard et al., 2016).

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 5 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

Robins-Browne et al. E. coliPathotypes

Biotype

Biotyping was once relied upon to group and separate individual

strains ofE. coli,particularly in the period before serotyping

became established for this purpose. Currently, biotyping is still

used to distinguish shigellae from othervarietiesof E. coli.

Although at present there is no comprehensive scheme to predict

E. coli biotype from whole genome sequences,this may be

possible in future should biotyping still be required.

Biochemicalprofiles also play a centralrole in the isolation

and preliminary identification ofE. colistrains in general,on

media such as McConkey and eosin methylene blue agar,and

of EHEC on sorbitol MaConkey (SMAC) agar and CHROMagar

STEC medium (de Boer et al., 2015).

Pathotype

As mentioned above,the subdivision ofDEC into pathotypes

has may uses.However,some isolates do not comply with the

standard pathotyping scheme (Table 2).Such strainsinclude

isolates of EPEC that carry genes for the heat-labile enterotoxin

of ETEC (Dutta et al., 2015); and strains of ETEC and EAEC that

secrete Shiga toxin (Zhang et al.,2007;Buchholz et al.,2011).

Even Shigella dysenteriae type 1,which carries the Shiga toxin

gene on its chromosome is atypical, as far as the Shigella biotype

is concerned,since no other strain in this “genus” produces

this toxin.In addition,Shigella boydii serotype 13 is unusual in

thatit carries the LEE pathogenicity island ofEPEC (Walters

et al., 2012), although this particular clone is evidently incorrectly

classified,being more closely related to E.albertiithan to E.

coli (Hyma etal., 2005).E. albertiiis a disctinctEscherichia

species that is characterised in part by its carriage ofthe LEE

pathogenicity island (Huys et al., 2003).

Hybrid strains of E.coli pathotypes are not surprising given

the mobility of most of the genes that encode virulence in DEC.

Whatis perhaps more surprising is thathybrids don’toccur

more often. In this regard, DEC strains that infect humans seem

somewhat limited in the combinations of virulence determinants

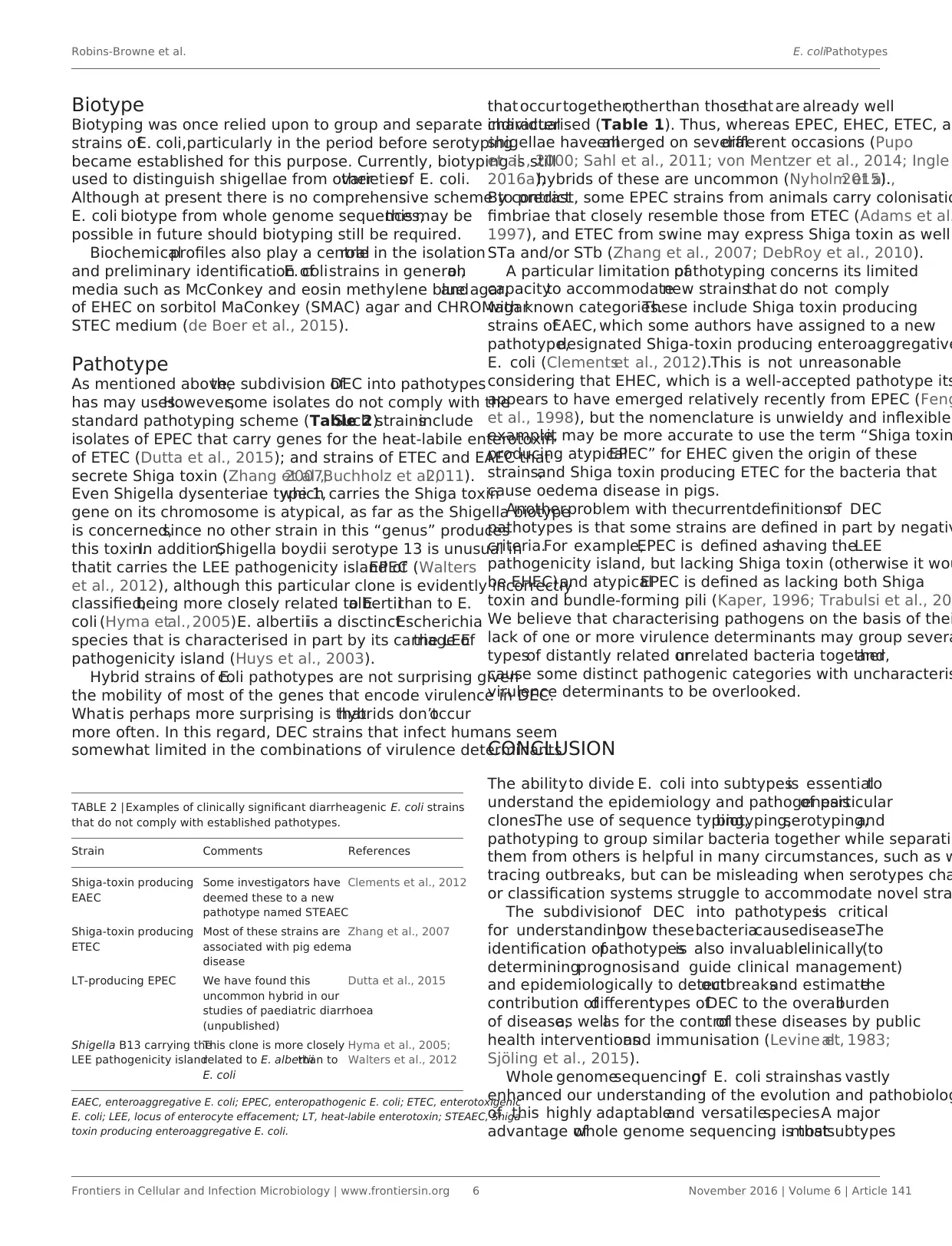

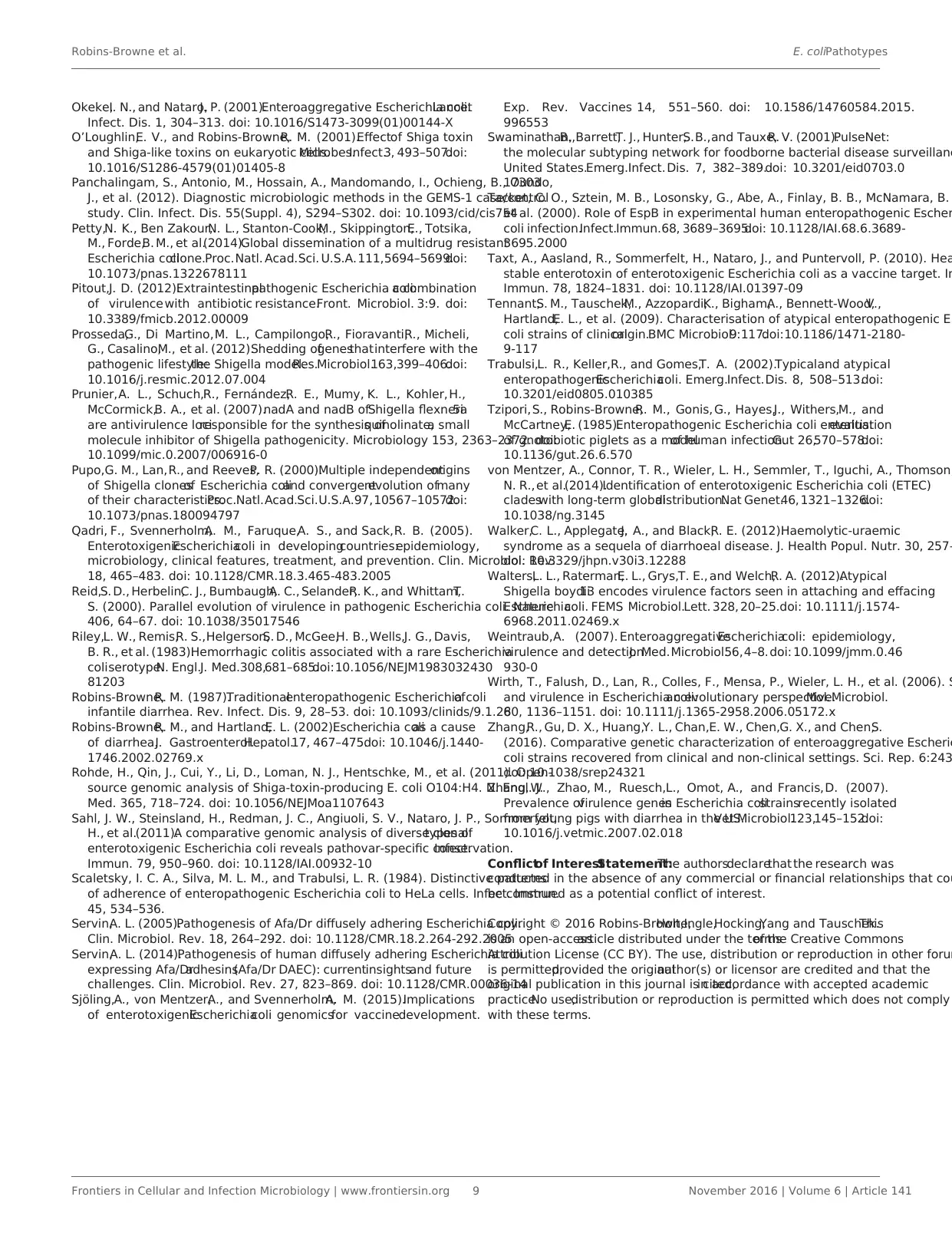

TABLE 2 | Examples of clinically significant diarrheagenic E. coli strains

that do not comply with established pathotypes.

Strain Comments References

Shiga-toxin producing

EAEC

Some investigators have

deemed these to a new

pathotype named STEAEC

Clements et al., 2012

Shiga-toxin producing

ETEC

Most of these strains are

associated with pig edema

disease

Zhang et al., 2007

LT-producing EPEC We have found this

uncommon hybrid in our

studies of paediatric diarrhoea

(unpublished)

Dutta et al., 2015

Shigella B13 carrying the

LEE pathogenicity island

This clone is more closely

related to E. albertiithan to

E. coli

Hyma et al., 2005;

Walters et al., 2012

EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; ETEC, enterotoxigenic

E. coli; LEE, locus of enterocyte effacement; LT, heat-labile enterotoxin; STEAEC, Shiga-

toxin producing enteroaggregative E. coli.

that occurtogether,otherthan thosethat are already well

characterised (Table 1). Thus, whereas EPEC, EHEC, ETEC, a

shigellae have allemerged on severaldifferent occasions (Pupo

et al., 2000; Sahl et al., 2011; von Mentzer et al., 2014; Ingle

2016a),hybrids of these are uncommon (Nyholm et al.,2015).

By contrast, some EPEC strains from animals carry colonisatio

fimbriae that closely resemble those from ETEC (Adams et al.

1997), and ETEC from swine may express Shiga toxin as well

STa and/or STb (Zhang et al., 2007; DebRoy et al., 2010).

A particular limitation ofpathotyping concerns its limited

capacityto accommodatenew strainsthat do not comply

with known categories.These include Shiga toxin producing

strains ofEAEC, which some authors have assigned to a new

pathotype,designated Shiga-toxin producing enteroaggregative

E. coli (Clementset al., 2012).This is not unreasonable

considering that EHEC, which is a well-accepted pathotype its

appears to have emerged relatively recently from EPEC (Feng

et al., 1998), but the nomenclature is unwieldy and inflexible.

example,it may be more accurate to use the term “Shiga toxin

producing atypicalEPEC” for EHEC given the origin of these

strains,and Shiga toxin producing ETEC for the bacteria that

cause oedema disease in pigs.

Anotherproblem with thecurrentdefinitionsof DEC

pathotypes is that some strains are defined in part by negativ

criteria.For example,EPEC is defined ashaving theLEE

pathogenicity island, but lacking Shiga toxin (otherwise it wou

be EHEC),and atypicalEPEC is defined as lacking both Shiga

toxin and bundle-forming pili (Kaper, 1996; Trabulsi et al., 20

We believe that characterising pathogens on the basis of thei

lack of one or more virulence determinants may group severa

typesof distantly related orunrelated bacteria together,and

cause some distinct pathogenic categories with uncharacteris

virulence determinants to be overlooked.

CONCLUSION

The abilityto divide E. coli into subtypesis essentialto

understand the epidemiology and pathogenesisof particular

clones.The use of sequence typing,biotyping,serotyping,and

pathotyping to group similar bacteria together while separatin

them from others is helpful in many circumstances, such as w

tracing outbreaks, but can be misleading when serotypes cha

or classification systems struggle to accommodate novel stra

The subdivisionof DEC into pathotypesis critical

for understandinghow thesebacteriacausedisease.The

identification ofpathotypesis also invaluableclinically(to

determiningprognosisand guide clinical management)

and epidemiologically to detectoutbreaksand estimatethe

contribution ofdifferenttypes ofDEC to the overallburden

of disease,as wellas for the controlof these diseases by public

health interventionsand immunisation (Levine etal., 1983;

Sjöling et al., 2015).

Whole genomesequencingof E. coli strainshas vastly

enhanced our understanding of the evolution and pathobiolog

of this highly adaptableand versatilespecies.A major

advantage ofwhole genome sequencing is thatmostsubtypes

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 6 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

Biotype

Biotyping was once relied upon to group and separate individual

strains ofE. coli,particularly in the period before serotyping

became established for this purpose. Currently, biotyping is still

used to distinguish shigellae from othervarietiesof E. coli.

Although at present there is no comprehensive scheme to predict

E. coli biotype from whole genome sequences,this may be

possible in future should biotyping still be required.

Biochemicalprofiles also play a centralrole in the isolation

and preliminary identification ofE. colistrains in general,on

media such as McConkey and eosin methylene blue agar,and

of EHEC on sorbitol MaConkey (SMAC) agar and CHROMagar

STEC medium (de Boer et al., 2015).

Pathotype

As mentioned above,the subdivision ofDEC into pathotypes

has may uses.However,some isolates do not comply with the

standard pathotyping scheme (Table 2).Such strainsinclude

isolates of EPEC that carry genes for the heat-labile enterotoxin

of ETEC (Dutta et al., 2015); and strains of ETEC and EAEC that

secrete Shiga toxin (Zhang et al.,2007;Buchholz et al.,2011).

Even Shigella dysenteriae type 1,which carries the Shiga toxin

gene on its chromosome is atypical, as far as the Shigella biotype

is concerned,since no other strain in this “genus” produces

this toxin.In addition,Shigella boydii serotype 13 is unusual in

thatit carries the LEE pathogenicity island ofEPEC (Walters

et al., 2012), although this particular clone is evidently incorrectly

classified,being more closely related to E.albertiithan to E.

coli (Hyma etal., 2005).E. albertiiis a disctinctEscherichia

species that is characterised in part by its carriage ofthe LEE

pathogenicity island (Huys et al., 2003).

Hybrid strains of E.coli pathotypes are not surprising given

the mobility of most of the genes that encode virulence in DEC.

Whatis perhaps more surprising is thathybrids don’toccur

more often. In this regard, DEC strains that infect humans seem

somewhat limited in the combinations of virulence determinants

TABLE 2 | Examples of clinically significant diarrheagenic E. coli strains

that do not comply with established pathotypes.

Strain Comments References

Shiga-toxin producing

EAEC

Some investigators have

deemed these to a new

pathotype named STEAEC

Clements et al., 2012

Shiga-toxin producing

ETEC

Most of these strains are

associated with pig edema

disease

Zhang et al., 2007

LT-producing EPEC We have found this

uncommon hybrid in our

studies of paediatric diarrhoea

(unpublished)

Dutta et al., 2015

Shigella B13 carrying the

LEE pathogenicity island

This clone is more closely

related to E. albertiithan to

E. coli

Hyma et al., 2005;

Walters et al., 2012

EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; ETEC, enterotoxigenic

E. coli; LEE, locus of enterocyte effacement; LT, heat-labile enterotoxin; STEAEC, Shiga-

toxin producing enteroaggregative E. coli.

that occurtogether,otherthan thosethat are already well

characterised (Table 1). Thus, whereas EPEC, EHEC, ETEC, a

shigellae have allemerged on severaldifferent occasions (Pupo

et al., 2000; Sahl et al., 2011; von Mentzer et al., 2014; Ingle

2016a),hybrids of these are uncommon (Nyholm et al.,2015).

By contrast, some EPEC strains from animals carry colonisatio

fimbriae that closely resemble those from ETEC (Adams et al.

1997), and ETEC from swine may express Shiga toxin as well

STa and/or STb (Zhang et al., 2007; DebRoy et al., 2010).

A particular limitation ofpathotyping concerns its limited

capacityto accommodatenew strainsthat do not comply

with known categories.These include Shiga toxin producing

strains ofEAEC, which some authors have assigned to a new

pathotype,designated Shiga-toxin producing enteroaggregative

E. coli (Clementset al., 2012).This is not unreasonable

considering that EHEC, which is a well-accepted pathotype its

appears to have emerged relatively recently from EPEC (Feng

et al., 1998), but the nomenclature is unwieldy and inflexible.

example,it may be more accurate to use the term “Shiga toxin

producing atypicalEPEC” for EHEC given the origin of these

strains,and Shiga toxin producing ETEC for the bacteria that

cause oedema disease in pigs.

Anotherproblem with thecurrentdefinitionsof DEC

pathotypes is that some strains are defined in part by negativ

criteria.For example,EPEC is defined ashaving theLEE

pathogenicity island, but lacking Shiga toxin (otherwise it wou

be EHEC),and atypicalEPEC is defined as lacking both Shiga

toxin and bundle-forming pili (Kaper, 1996; Trabulsi et al., 20

We believe that characterising pathogens on the basis of thei

lack of one or more virulence determinants may group severa

typesof distantly related orunrelated bacteria together,and

cause some distinct pathogenic categories with uncharacteris

virulence determinants to be overlooked.

CONCLUSION

The abilityto divide E. coli into subtypesis essentialto

understand the epidemiology and pathogenesisof particular

clones.The use of sequence typing,biotyping,serotyping,and

pathotyping to group similar bacteria together while separatin

them from others is helpful in many circumstances, such as w

tracing outbreaks, but can be misleading when serotypes cha

or classification systems struggle to accommodate novel stra

The subdivisionof DEC into pathotypesis critical

for understandinghow thesebacteriacausedisease.The

identification ofpathotypesis also invaluableclinically(to

determiningprognosisand guide clinical management)

and epidemiologically to detectoutbreaksand estimatethe

contribution ofdifferenttypes ofDEC to the overallburden

of disease,as wellas for the controlof these diseases by public

health interventionsand immunisation (Levine etal., 1983;

Sjöling et al., 2015).

Whole genomesequencingof E. coli strainshas vastly

enhanced our understanding of the evolution and pathobiolog

of this highly adaptableand versatilespecies.A major

advantage ofwhole genome sequencing is thatmostsubtypes

Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology | www.frontiersin.org 6 November 2016 | Volume 6 | Article 141

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Robins-Browne et al. E. coliPathotypes

and otherpropertiescan be predicted with ahigh degree

of accuracyfrom sequencedata.Combinedwith clinical,

pathologicaland epidemiologicalmetadata,whole genome

sequencing willalso permit elucidation of which strains within

a subtype are more virulence than others.For these reasons,

we expectthatsome ofthe typing schemesin currentuse

will eventuallybe replaced bya system thatis based on

a combination ofgeneswithin thecore genome(probably

cgMLST) and the accessory genome, comprising major virulence

determinants and associated pathogenic potential. In this regard,

the coordinated sharing ofwhole genome sequence data via

GenomeTrakr,coupled with standardised extraction ofE. coli

typing information including sequence type, serotype, pathotype

and antimicrobial resistance from genome data using tools such

as Enterobase is likely to become the new gold standard for E.

coli analysis.Thus,although whole genome sequencing will not

replace pathotyping in the short-term,it should,together with

clinical,field,and experimentaldata,be used to enhance our

understanding of what constitutes a pathotype, while allowing

more pathotypes to be identified by permitting the identificat

of particularcombinationsof genesthatare associated with

specific clinicalsyndromes and pathology.This is particularly

important for loosely defined pathotypes, such as EAEC, DAEC

AIEC, and atypical EPEC.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All of the authorscontributed tothe preparation ofthe

manuscript, and to the ideas and concepts contained in it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research in the authors’ laboratories is funded by the Austral

NHMRC.

REFERENCES

Adams, L. M., Simmons, C. P., Rezmann, L., Strugnell, R. A., and Robins-Browne,

R. M. (1997).Identification and characterization ofa K88- and CS31A-like

operon ofa rabbitenteropathogenic Escherichia colistrain which encodes

fimbriae involved in the colonization ofrabbit intestine.Infect.Immun.65,

5222–5230.

Alhagamhmad,M. H., Day,A. S.,Lemberg,D. A., and Leach,S. T. (2016).An

overview of the bacterial contribution to Crohn disease pathogenesis.J. Med.