Analyzing Ethical Leadership: Moral Equity & Workplace Discretion

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/14

|23

|12581

|139

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study examines the relationship between ethical leadership, moral equity judgments, and discretionary workplace behaviors (both organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and workplace deviance (WPD)). It posits that ethical leaders influence employees' moral equity judgments, leading them to view workplace deviance as morally inequitable and organizational citizenship as morally equitable. These judgments, in turn, guide employee behavior, mediating the relationship between ethical leadership and both the avoidance of antisocial conduct and engagement in prosocial behavior. The study provides empirical evidence supporting the importance of ethical leadership in shaping employee ethics-related judgments and behaviors, and highlights how moral equity judgments serve as a cognitive mechanism through which employees regulate their actions in the workplace. The research emphasizes that individuals tend to engage in behaviors they perceive as morally equitable while avoiding those they deem morally inequitable.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication

Ethical Leadership, Moral Equity Jud

and Discretionary Workplace Behav

Article in Human Relations · July

DOI: 10.1177/0018726713481633

CITATIONS

44

READS

438

4 authors, including:

Ping Shao

California State University, Sacramento

14PUBLICATIONS130CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Scott Dust

Miami University

13PUBLICATIONS117CITAT

SEE PROFILE

Ethical Leadership, Moral Equity Jud

and Discretionary Workplace Behav

Article in Human Relations · July

DOI: 10.1177/0018726713481633

CITATIONS

44

READS

438

4 authors, including:

Ping Shao

California State University, Sacramento

14PUBLICATIONS130CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Scott Dust

Miami University

13PUBLICATIONS117CITAT

SEE PROFILE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

human relations

66(7) 951 –972

© The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0018726713481633

hum.sagepub.com

human relations

Ethical leadership, moral equity

judgments, and discretionary

workplace behavior

Christian J Resick

Drexel University, USA

Michael B Hargis

University of Central Arkansas, USA

Ping Shao

California State University, Sacramento, USA

Scott B Dust

Drexel University, USA

Abstract

The current study examines the role of ethical cognition as a psychological me

linking ethical leadership to employee engagement in specific discretionary wo

behaviors. Hypotheses are developed proposing that ethical leadership is assoc

with employees’ negative moral equity judgments of workplace deviance (a dis

antisocial behavior) and positive moral equity judgments of organizational citiz

discretionary prosocial behavior). In addition, hypotheses propose that moral e

judgments are a key type of ethical cognition linking ethical leadership with em

behaviors. Hypotheses are tested in a cross-organizational sample of 190 supe

employee dyads. Results indicate that employees who work for ethical leaders

to judge acts of workplace deviance as morally inequitable and acts of organiza

citizenship as morally equitable. In turn, these judgments guided employee reg

of behavior, and mediated the relationships between ethical leadership and em

avoidance of antisocial conduct and engagement in prosocial behavior.

Corresponding author:

Christian J Resick, Department of Management, Drexel University, Peck PSRC, #213, Philadelphia,

PA 19104, USA.

Email: cresick@drexel.edu

481633 HUM66710.1177/0018726713481633Human RelationsResick et al.

2013

66(7) 951 –972

© The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0018726713481633

hum.sagepub.com

human relations

Ethical leadership, moral equity

judgments, and discretionary

workplace behavior

Christian J Resick

Drexel University, USA

Michael B Hargis

University of Central Arkansas, USA

Ping Shao

California State University, Sacramento, USA

Scott B Dust

Drexel University, USA

Abstract

The current study examines the role of ethical cognition as a psychological me

linking ethical leadership to employee engagement in specific discretionary wo

behaviors. Hypotheses are developed proposing that ethical leadership is assoc

with employees’ negative moral equity judgments of workplace deviance (a dis

antisocial behavior) and positive moral equity judgments of organizational citiz

discretionary prosocial behavior). In addition, hypotheses propose that moral e

judgments are a key type of ethical cognition linking ethical leadership with em

behaviors. Hypotheses are tested in a cross-organizational sample of 190 supe

employee dyads. Results indicate that employees who work for ethical leaders

to judge acts of workplace deviance as morally inequitable and acts of organiza

citizenship as morally equitable. In turn, these judgments guided employee reg

of behavior, and mediated the relationships between ethical leadership and em

avoidance of antisocial conduct and engagement in prosocial behavior.

Corresponding author:

Christian J Resick, Department of Management, Drexel University, Peck PSRC, #213, Philadelphia,

PA 19104, USA.

Email: cresick@drexel.edu

481633 HUM66710.1177/0018726713481633Human RelationsResick et al.

2013

952 Human Relations 66(7)

Keywords

ethical judgments, ethical leadership, leadership, organizational citizenship beha

workplace deviance

When we see men of worth, we should think of equaling them; when we see men of a

contrary character, we should turn inwards and examine ourselves. (Confucius 551−479

BCE)

When you deal with ethical dilemmas in the years to come, I hope that you will stay true

to yourself by remembering those whose lives your decision will affect. (Mary L Schapiro,

US Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman 2011)

Introduction

Ethical transgressions in business, sports, academic, and even religious organizations

have been well documented over the past decade. While some transgressions are the

result of intentional unethical behavior, many others occur because people fail to con-

sider the ethical consequences of their actions and decisions. For example, the financial

crisis of 2008 resulted from a complex combination of factors including high risk lend-

ing, passing on the risk in secondary markets, and corporate leaders failing to consider

the potential consequences to borrowers, institutions, or markets. In contrast, ethical

misconduct is less likely to occur when people recognize the ethical consequences of

their actions. Organizational leadership plays a prominent role in managing ethical

accountability (Barnard, 1938; Dickson et al., 2001); to so do effectively, leaders must

help employees to understand ethically charged issues, and make appropriate

judgments.

To better understand the linkages between leadership and organizational ethics,

Brown et al. (2005) put forth a social learning-based theory that defined ethical leader-

ship as ‘the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions

and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through

two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision making’ (p. 120). An emerging

body of research provides support for a connection between ethical leadership and

employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors, such as commitment, psychological

safety, voice, citizenship behaviors, and task performance (e.g. Brown et al., 2005;

Kalshoven et al., 2011; Mayer et al., 2009; Piccolo et al., 2010; Walumbwa and

Schaubroeck, 2009). To date, however, surprisingly little research has examined the link-

ages between ethical leadership and employee ethical cognitions, particularly specific

ethical judgments. This is an important omission as Brown and Treviño (2006) proposed

that employees of ethical leaders should have a heightened awareness of the ethical

implications of their actions and decisions, along with a tendency to make ethically

appropriate decisions. In turn, ethical cognitions, such as ethical judgments, are thought

to guide ethical intentions and behaviors (Hannah et al., 2011; Rest, 1986). That is, ethical

cognition provides a basis for behavior regulation; people are likely to engage in behav-

iors they deem as ethically appropriate and refrain from actions they deem as ethically

inappropriate. As such, we expect that ethical judgments are a psychological mechanism

Keywords

ethical judgments, ethical leadership, leadership, organizational citizenship beha

workplace deviance

When we see men of worth, we should think of equaling them; when we see men of a

contrary character, we should turn inwards and examine ourselves. (Confucius 551−479

BCE)

When you deal with ethical dilemmas in the years to come, I hope that you will stay true

to yourself by remembering those whose lives your decision will affect. (Mary L Schapiro,

US Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman 2011)

Introduction

Ethical transgressions in business, sports, academic, and even religious organizations

have been well documented over the past decade. While some transgressions are the

result of intentional unethical behavior, many others occur because people fail to con-

sider the ethical consequences of their actions and decisions. For example, the financial

crisis of 2008 resulted from a complex combination of factors including high risk lend-

ing, passing on the risk in secondary markets, and corporate leaders failing to consider

the potential consequences to borrowers, institutions, or markets. In contrast, ethical

misconduct is less likely to occur when people recognize the ethical consequences of

their actions. Organizational leadership plays a prominent role in managing ethical

accountability (Barnard, 1938; Dickson et al., 2001); to so do effectively, leaders must

help employees to understand ethically charged issues, and make appropriate

judgments.

To better understand the linkages between leadership and organizational ethics,

Brown et al. (2005) put forth a social learning-based theory that defined ethical leader-

ship as ‘the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions

and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through

two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision making’ (p. 120). An emerging

body of research provides support for a connection between ethical leadership and

employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors, such as commitment, psychological

safety, voice, citizenship behaviors, and task performance (e.g. Brown et al., 2005;

Kalshoven et al., 2011; Mayer et al., 2009; Piccolo et al., 2010; Walumbwa and

Schaubroeck, 2009). To date, however, surprisingly little research has examined the link-

ages between ethical leadership and employee ethical cognitions, particularly specific

ethical judgments. This is an important omission as Brown and Treviño (2006) proposed

that employees of ethical leaders should have a heightened awareness of the ethical

implications of their actions and decisions, along with a tendency to make ethically

appropriate decisions. In turn, ethical cognitions, such as ethical judgments, are thought

to guide ethical intentions and behaviors (Hannah et al., 2011; Rest, 1986). That is, ethical

cognition provides a basis for behavior regulation; people are likely to engage in behav-

iors they deem as ethically appropriate and refrain from actions they deem as ethically

inappropriate. As such, we expect that ethical judgments are a psychological mechanism

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Resick et al. 953

that sheds new light on the relationships between ethical leadership and employee discre-

tionary behavior. Research is now needed to examine these relationships empirically.

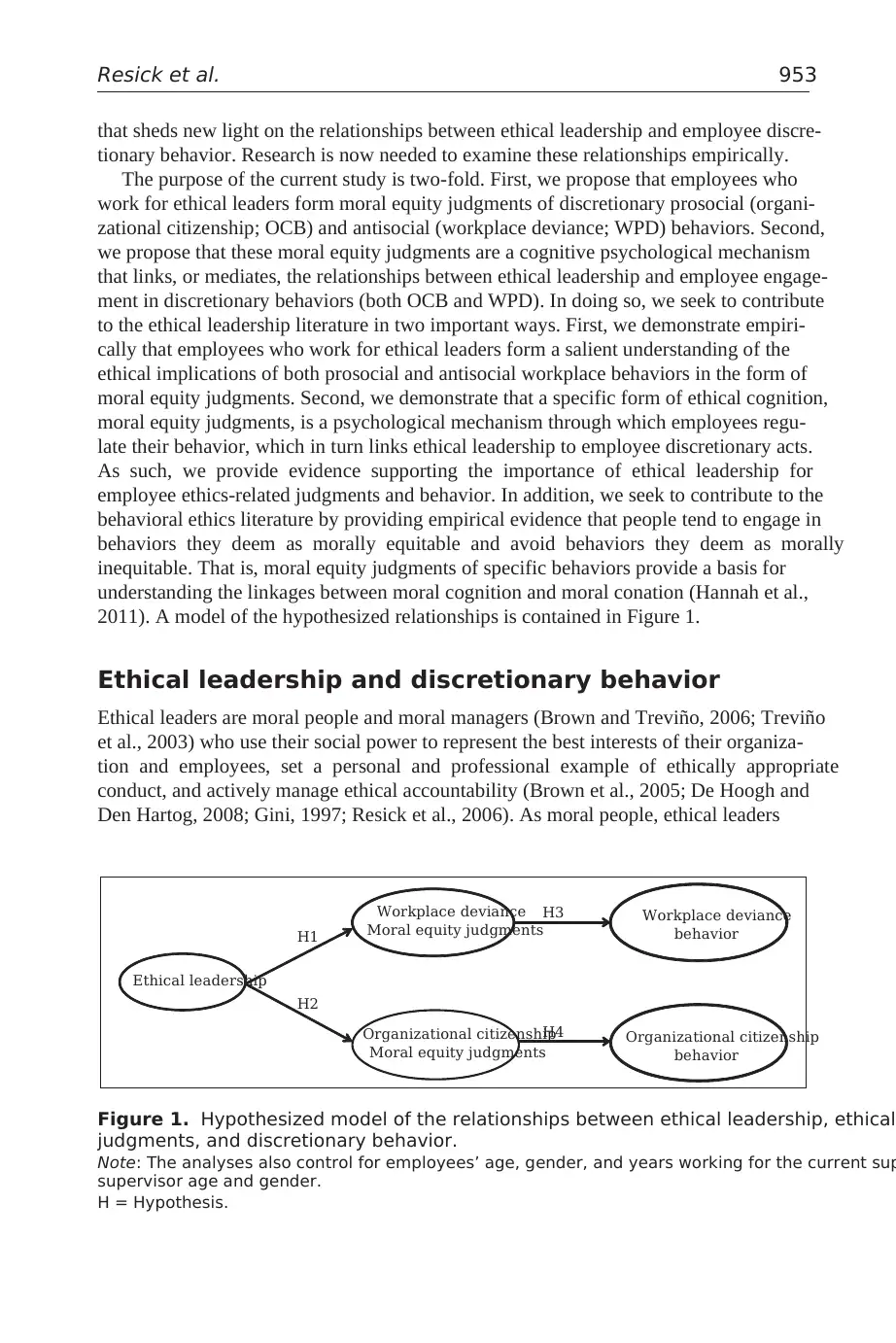

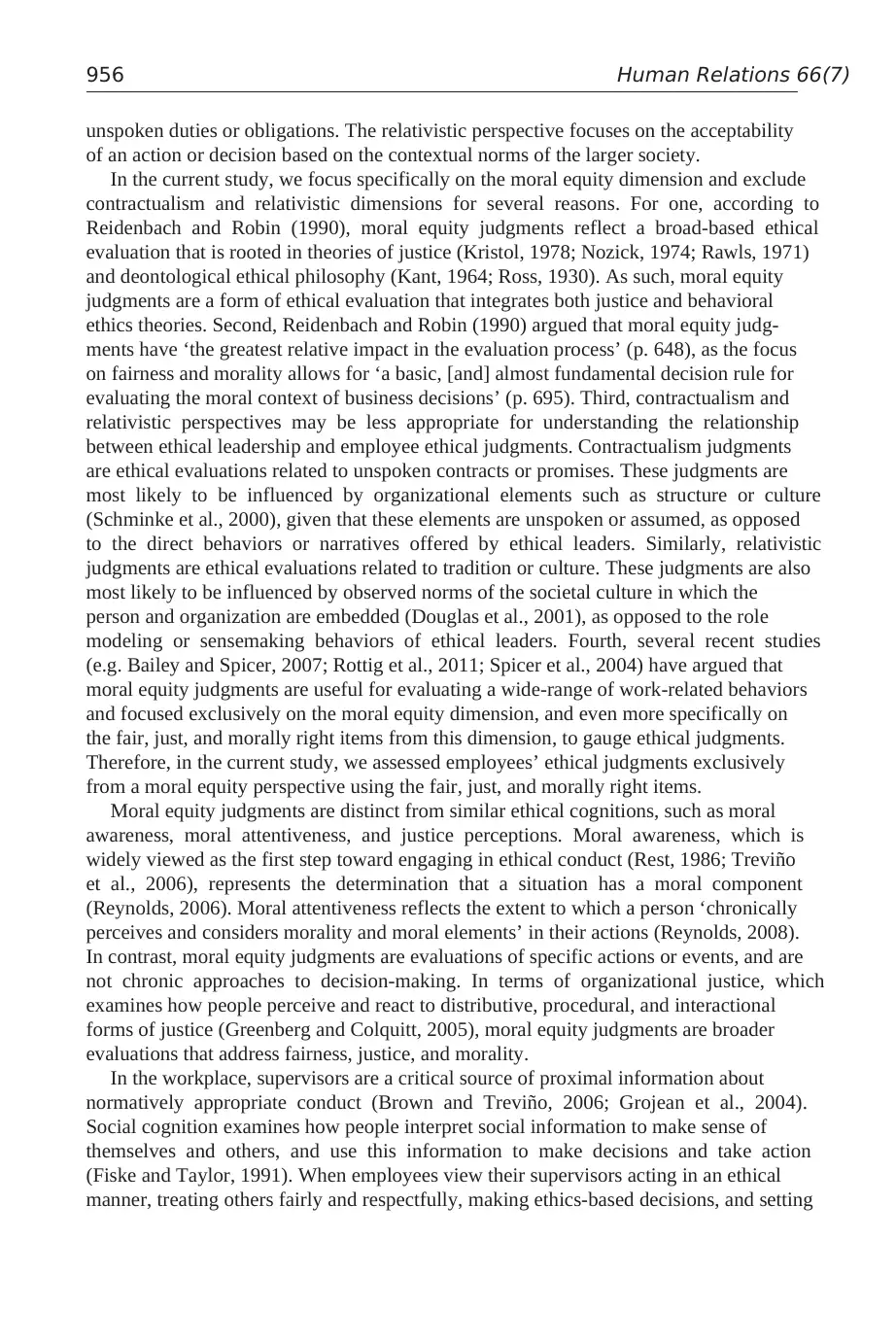

The purpose of the current study is two-fold. First, we propose that employees who

work for ethical leaders form moral equity judgments of discretionary prosocial (organi-

zational citizenship; OCB) and antisocial (workplace deviance; WPD) behaviors. Second,

we propose that these moral equity judgments are a cognitive psychological mechanism

that links, or mediates, the relationships between ethical leadership and employee engage-

ment in discretionary behaviors (both OCB and WPD). In doing so, we seek to contribute

to the ethical leadership literature in two important ways. First, we demonstrate empiri-

cally that employees who work for ethical leaders form a salient understanding of the

ethical implications of both prosocial and antisocial workplace behaviors in the form of

moral equity judgments. Second, we demonstrate that a specific form of ethical cognition,

moral equity judgments, is a psychological mechanism through which employees regu-

late their behavior, which in turn links ethical leadership to employee discretionary acts.

As such, we provide evidence supporting the importance of ethical leadership for

employee ethics-related judgments and behavior. In addition, we seek to contribute to the

behavioral ethics literature by providing empirical evidence that people tend to engage in

behaviors they deem as morally equitable and avoid behaviors they deem as morally

inequitable. That is, moral equity judgments of specific behaviors provide a basis for

understanding the linkages between moral cognition and moral conation (Hannah et al.,

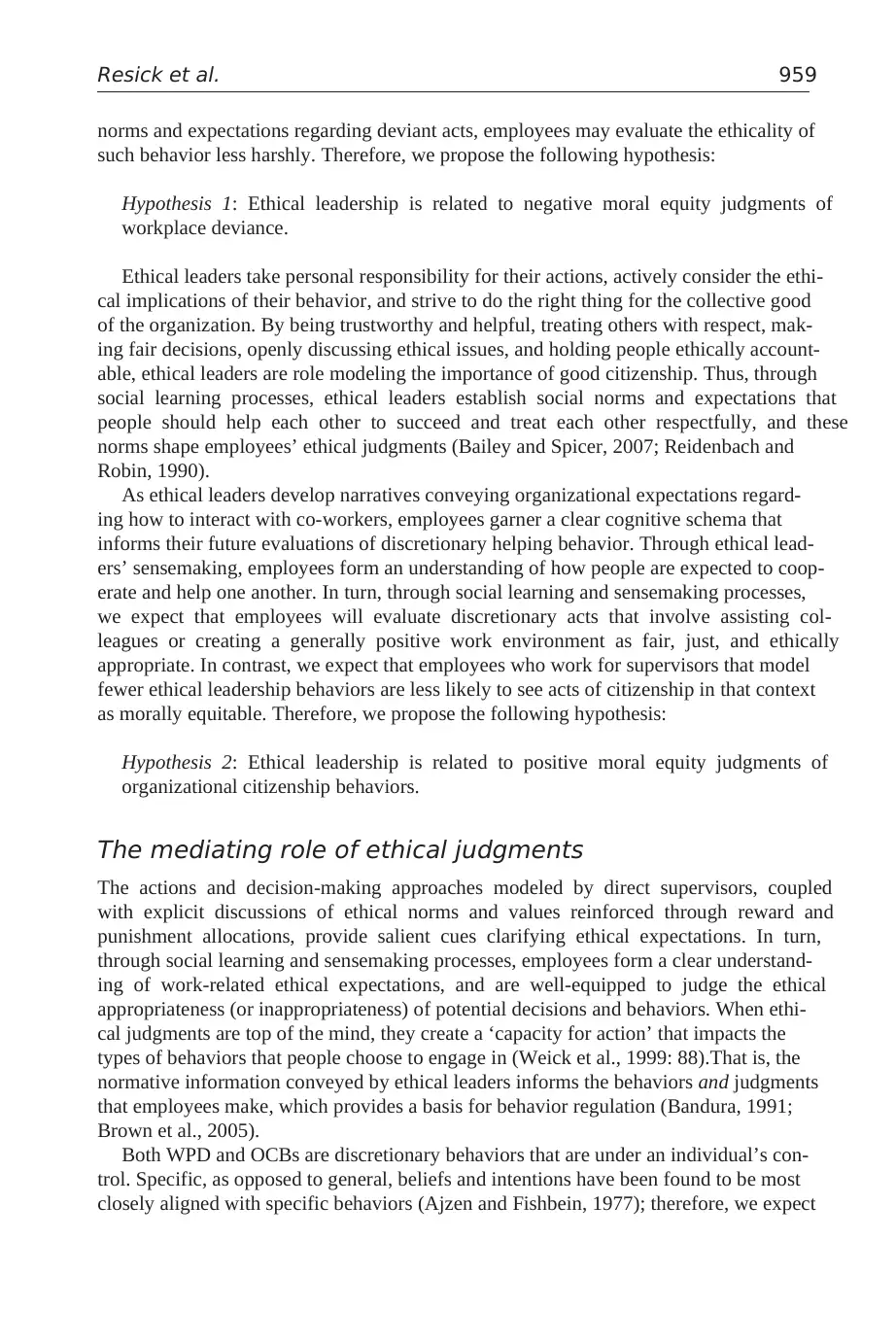

2011). A model of the hypothesized relationships is contained in Figure 1.

Ethical leadership and discretionary behavior

Ethical leaders are moral people and moral managers (Brown and Treviño, 2006; Treviño

et al., 2003) who use their social power to represent the best interests of their organiza-

tion and employees, set a personal and professional example of ethically appropriate

conduct, and actively manage ethical accountability (Brown et al., 2005; De Hoogh and

Den Hartog, 2008; Gini, 1997; Resick et al., 2006). As moral people, ethical leaders

Ethical leadership

Workplace deviance

Moral equity judgments

Organizational citizenship

Moral equity judgments

Workplace deviance

behavior

Organizational citizenship

behavior

H1

H2

H3

H4

Figure 1. Hypothesized model of the relationships between ethical leadership, ethical

judgments, and discretionary behavior.

Note: The analyses also control for employees’ age, gender, and years working for the current sup

supervisor age and gender.

H = Hypothesis.

that sheds new light on the relationships between ethical leadership and employee discre-

tionary behavior. Research is now needed to examine these relationships empirically.

The purpose of the current study is two-fold. First, we propose that employees who

work for ethical leaders form moral equity judgments of discretionary prosocial (organi-

zational citizenship; OCB) and antisocial (workplace deviance; WPD) behaviors. Second,

we propose that these moral equity judgments are a cognitive psychological mechanism

that links, or mediates, the relationships between ethical leadership and employee engage-

ment in discretionary behaviors (both OCB and WPD). In doing so, we seek to contribute

to the ethical leadership literature in two important ways. First, we demonstrate empiri-

cally that employees who work for ethical leaders form a salient understanding of the

ethical implications of both prosocial and antisocial workplace behaviors in the form of

moral equity judgments. Second, we demonstrate that a specific form of ethical cognition,

moral equity judgments, is a psychological mechanism through which employees regu-

late their behavior, which in turn links ethical leadership to employee discretionary acts.

As such, we provide evidence supporting the importance of ethical leadership for

employee ethics-related judgments and behavior. In addition, we seek to contribute to the

behavioral ethics literature by providing empirical evidence that people tend to engage in

behaviors they deem as morally equitable and avoid behaviors they deem as morally

inequitable. That is, moral equity judgments of specific behaviors provide a basis for

understanding the linkages between moral cognition and moral conation (Hannah et al.,

2011). A model of the hypothesized relationships is contained in Figure 1.

Ethical leadership and discretionary behavior

Ethical leaders are moral people and moral managers (Brown and Treviño, 2006; Treviño

et al., 2003) who use their social power to represent the best interests of their organiza-

tion and employees, set a personal and professional example of ethically appropriate

conduct, and actively manage ethical accountability (Brown et al., 2005; De Hoogh and

Den Hartog, 2008; Gini, 1997; Resick et al., 2006). As moral people, ethical leaders

Ethical leadership

Workplace deviance

Moral equity judgments

Organizational citizenship

Moral equity judgments

Workplace deviance

behavior

Organizational citizenship

behavior

H1

H2

H3

H4

Figure 1. Hypothesized model of the relationships between ethical leadership, ethical

judgments, and discretionary behavior.

Note: The analyses also control for employees’ age, gender, and years working for the current sup

supervisor age and gender.

H = Hypothesis.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

954 Human Relations 66(7)

demonstrate honesty, integrity, fairness, a broad ethical awareness, and are considerate

and respectful of others; as moral managers, ethical leaders comply with laws and

regulations, establish ethical expectations and hold employees accountable, and make

decisions reflecting the best interests of employees and the organization (Brown et al.,

2005; Kalshoven et al., 2011; Resick et al., 2011; Treviño et al., 2003).

Brown and colleagues (2005) proposed that ethical leaders are ethical role models

who provide ethical guidance to employees via social learning processes. According to

social learning theory, individuals learn by observing role models’ actions, decisions,

and subsequent consequences, and then emulating what they observed (Bandura, 1977,

1986). To serve as an ethical role model and an ethical leader, Brown et al. (2005)

noted that a leader first needs to be perceived as attractive, legitimate, and credible.

This perception is developed by demonstrating normatively appropriate behaviors, and

explicitly discussing ethical expectations to draw employees’ attention to ethical issues.

Leaders further become attractive and credible by modeling honest and fair behavior,

treating others with consideration, and making decisions aimed at employees’ best

interests. Leaders also become legitimate sources of ethical authority by using rewards

and punishment to manage ethical accountability. All of these behaviors increase the

effectiveness of social learning (Brown et al., 2005). Through these processes, ethical

leaders are expected to influence employee ethical decision making, promote ethical

and prosocial conduct, and inhibit deviant and unethical behavior (Brown and Treviño,

2006).

Several studies have linked ethical leadership with employee prosocial OCBs (e.g.

Kalshoven et al., 2011; Mayer et al., 2009). Citizenship behaviors are important for

both individual and organizational success (Podsakoff et al., 2009), and include actions

that are ‘discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward sys-

tem, and that in the aggregate, promotes the efficient and effective functioning of the

organization’ (Organ, 1988: 4). There are generally considered to be two broad dimen-

sions underlying OCBs. One dimension is targeted at co-workers and includes passing

along helpful information and going out of one’s way to help other employees. The

second dimension is targeted at the organization itself and includes adhering to infor-

mal rules and promoting the organization’s products or services to others (see Dalal,

2005; Williams and Anderson, 1991). Consistent with Mayer et al.’s (2009) work, we

specifically focus on interpersonal-focused OCBs. This set of OCBs are most relevant

to our model because they are a reflection of a broad concern for others, they signal the

importance of the work environment to the employee, and they are the most frequently

studied OCBs (Podsakoff et al., 2000).

Workplace deviance is a contrasting set of discretionary behaviors that nearly all

organizations must confront, and involves ‘voluntary behavior that violates significant

organizational norms and in so doing threatens the well-being of an organization, its

members, or both’ (Robinson and Bennett, 1995: 556). WPD includes overt actions such

as damaging property and instigating a confrontation, along with covert actions such as

withholding effort or sabotaging a project (Bennett and Robinson, 2000; Robinson and

Bennett, 1995). There are two underlying dimensions of WPD behaviors, with one dimen-

sion targeted at harming co-workers through actions such as behaving rudely or publi-

cally embarrassing someone, and one dimension targeted at harming the organization by

demonstrate honesty, integrity, fairness, a broad ethical awareness, and are considerate

and respectful of others; as moral managers, ethical leaders comply with laws and

regulations, establish ethical expectations and hold employees accountable, and make

decisions reflecting the best interests of employees and the organization (Brown et al.,

2005; Kalshoven et al., 2011; Resick et al., 2011; Treviño et al., 2003).

Brown and colleagues (2005) proposed that ethical leaders are ethical role models

who provide ethical guidance to employees via social learning processes. According to

social learning theory, individuals learn by observing role models’ actions, decisions,

and subsequent consequences, and then emulating what they observed (Bandura, 1977,

1986). To serve as an ethical role model and an ethical leader, Brown et al. (2005)

noted that a leader first needs to be perceived as attractive, legitimate, and credible.

This perception is developed by demonstrating normatively appropriate behaviors, and

explicitly discussing ethical expectations to draw employees’ attention to ethical issues.

Leaders further become attractive and credible by modeling honest and fair behavior,

treating others with consideration, and making decisions aimed at employees’ best

interests. Leaders also become legitimate sources of ethical authority by using rewards

and punishment to manage ethical accountability. All of these behaviors increase the

effectiveness of social learning (Brown et al., 2005). Through these processes, ethical

leaders are expected to influence employee ethical decision making, promote ethical

and prosocial conduct, and inhibit deviant and unethical behavior (Brown and Treviño,

2006).

Several studies have linked ethical leadership with employee prosocial OCBs (e.g.

Kalshoven et al., 2011; Mayer et al., 2009). Citizenship behaviors are important for

both individual and organizational success (Podsakoff et al., 2009), and include actions

that are ‘discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward sys-

tem, and that in the aggregate, promotes the efficient and effective functioning of the

organization’ (Organ, 1988: 4). There are generally considered to be two broad dimen-

sions underlying OCBs. One dimension is targeted at co-workers and includes passing

along helpful information and going out of one’s way to help other employees. The

second dimension is targeted at the organization itself and includes adhering to infor-

mal rules and promoting the organization’s products or services to others (see Dalal,

2005; Williams and Anderson, 1991). Consistent with Mayer et al.’s (2009) work, we

specifically focus on interpersonal-focused OCBs. This set of OCBs are most relevant

to our model because they are a reflection of a broad concern for others, they signal the

importance of the work environment to the employee, and they are the most frequently

studied OCBs (Podsakoff et al., 2000).

Workplace deviance is a contrasting set of discretionary behaviors that nearly all

organizations must confront, and involves ‘voluntary behavior that violates significant

organizational norms and in so doing threatens the well-being of an organization, its

members, or both’ (Robinson and Bennett, 1995: 556). WPD includes overt actions such

as damaging property and instigating a confrontation, along with covert actions such as

withholding effort or sabotaging a project (Bennett and Robinson, 2000; Robinson and

Bennett, 1995). There are two underlying dimensions of WPD behaviors, with one dimen-

sion targeted at harming co-workers through actions such as behaving rudely or publi-

cally embarrassing someone, and one dimension targeted at harming the organization by

Resick et al. 955

engaging in acts such as taking supplies, damaging property, or discussing confidential

information with unauthorized personnel (Bennett and Robinson, 2000; Robinson and

Bennett, 1995). Both dimensions have been found to be highly intercorrelated (Dalal,

2005; Dunlop and Lee, 2004). In prior studies, Mayer and colleagues have found ethical

leadership to be directly and negatively related to organization-focused WPD (Mayer

et al., 2009) and unethical behaviors (Mayer et al., 2012). However, Detert et al. (2007)

found that ethical leadership was unrelated to objective indicators of counterproductive

behaviors. In the current study, we focus on the full set of WPD behaviors to understand

the implications of ethical leadership for inhibiting antisocial behaviors directed at both

co-workers and the organization in general.

Ethical leaders are thought to influence the employee’s ethical understanding and

decision making (Brown and Treviño, 2006); in turn, these ethical cognition provide a

basis for behavior regulation (Hannah et al., 2012; Rest, 1986; Rottig et al., 2011). As

such, we expect that ethical judgments are a psychological mechanism that sheds new

light on the relationship between ethical leadership and both OCB and WPD discretion-

ary workplace behaviors.

Several studies have provided insights into the psychological mechanisms linking

ethical leadership and employee behavior (both prosocial and antisocial). Focusing on

prosocial and general work-related behaviors, studies have found that motivation-related

mechanisms such as effort, task significance, self-efficacy, and organizational identifi-

cation mediate relationships between ethical leadership and both task and citizenship

forms of performance (Piccolo et al., 2010; Walumbwa et al., 2011). Similarly,

Walumbwa and Schaubroeck (2009) found that employees’ psychological safety partially

mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and constructive voice behavior.

In contrast, the psychological mechanisms linking ethical leadership with employee

avoidance of deviance or ethical transgressions is somewhat less clear. Several studies

provide some indication that ethical leadership inhibits antisocial behavior through its

impact on the unit’s psychosocial environment, including ethical climates (Mayer et al.,

2012) and ethical culture (Schaubroeck et al., 2012). Given the social learning basis of

ethical leadership, surprisingly little research has examined the relationships between

ethical leadership and the extent to which employees form judgments about the types of

behaviors that are fair, just, and morally appropriate or inappropriate, and use these

judgments to regulate behavior. We examine the intervening role of moral equity judg-

ment in the next section.

Ethical leadership and ethical judgments

Ethical judgments

Reidenbach and Robin (1990) posited that individuals use multiple philosophical per-

spectives of ethics and morals (e.g. justice, relativism, egoism, utilitarianism, and

deontology) when making ethical judgments, and developed a scale to assess ethical

judgments from three perspectives, including moral equity, contractualism, and relativ-

istic judgments. The moral equity perspective focuses on evaluations of decisions or

actions in terms of their moral rightness, justice, and fairness. Contractualism focuses on

engaging in acts such as taking supplies, damaging property, or discussing confidential

information with unauthorized personnel (Bennett and Robinson, 2000; Robinson and

Bennett, 1995). Both dimensions have been found to be highly intercorrelated (Dalal,

2005; Dunlop and Lee, 2004). In prior studies, Mayer and colleagues have found ethical

leadership to be directly and negatively related to organization-focused WPD (Mayer

et al., 2009) and unethical behaviors (Mayer et al., 2012). However, Detert et al. (2007)

found that ethical leadership was unrelated to objective indicators of counterproductive

behaviors. In the current study, we focus on the full set of WPD behaviors to understand

the implications of ethical leadership for inhibiting antisocial behaviors directed at both

co-workers and the organization in general.

Ethical leaders are thought to influence the employee’s ethical understanding and

decision making (Brown and Treviño, 2006); in turn, these ethical cognition provide a

basis for behavior regulation (Hannah et al., 2012; Rest, 1986; Rottig et al., 2011). As

such, we expect that ethical judgments are a psychological mechanism that sheds new

light on the relationship between ethical leadership and both OCB and WPD discretion-

ary workplace behaviors.

Several studies have provided insights into the psychological mechanisms linking

ethical leadership and employee behavior (both prosocial and antisocial). Focusing on

prosocial and general work-related behaviors, studies have found that motivation-related

mechanisms such as effort, task significance, self-efficacy, and organizational identifi-

cation mediate relationships between ethical leadership and both task and citizenship

forms of performance (Piccolo et al., 2010; Walumbwa et al., 2011). Similarly,

Walumbwa and Schaubroeck (2009) found that employees’ psychological safety partially

mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and constructive voice behavior.

In contrast, the psychological mechanisms linking ethical leadership with employee

avoidance of deviance or ethical transgressions is somewhat less clear. Several studies

provide some indication that ethical leadership inhibits antisocial behavior through its

impact on the unit’s psychosocial environment, including ethical climates (Mayer et al.,

2012) and ethical culture (Schaubroeck et al., 2012). Given the social learning basis of

ethical leadership, surprisingly little research has examined the relationships between

ethical leadership and the extent to which employees form judgments about the types of

behaviors that are fair, just, and morally appropriate or inappropriate, and use these

judgments to regulate behavior. We examine the intervening role of moral equity judg-

ment in the next section.

Ethical leadership and ethical judgments

Ethical judgments

Reidenbach and Robin (1990) posited that individuals use multiple philosophical per-

spectives of ethics and morals (e.g. justice, relativism, egoism, utilitarianism, and

deontology) when making ethical judgments, and developed a scale to assess ethical

judgments from three perspectives, including moral equity, contractualism, and relativ-

istic judgments. The moral equity perspective focuses on evaluations of decisions or

actions in terms of their moral rightness, justice, and fairness. Contractualism focuses on

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

956 Human Relations 66(7)

unspoken duties or obligations. The relativistic perspective focuses on the acceptability

of an action or decision based on the contextual norms of the larger society.

In the current study, we focus specifically on the moral equity dimension and exclude

contractualism and relativistic dimensions for several reasons. For one, according to

Reidenbach and Robin (1990), moral equity judgments reflect a broad-based ethical

evaluation that is rooted in theories of justice (Kristol, 1978; Nozick, 1974; Rawls, 1971)

and deontological ethical philosophy (Kant, 1964; Ross, 1930). As such, moral equity

judgments are a form of ethical evaluation that integrates both justice and behavioral

ethics theories. Second, Reidenbach and Robin (1990) argued that moral equity judg-

ments have ‘the greatest relative impact in the evaluation process’ (p. 648), as the focus

on fairness and morality allows for ‘a basic, [and] almost fundamental decision rule for

evaluating the moral context of business decisions’ (p. 695). Third, contractualism and

relativistic perspectives may be less appropriate for understanding the relationship

between ethical leadership and employee ethical judgments. Contractualism judgments

are ethical evaluations related to unspoken contracts or promises. These judgments are

most likely to be influenced by organizational elements such as structure or culture

(Schminke et al., 2000), given that these elements are unspoken or assumed, as opposed

to the direct behaviors or narratives offered by ethical leaders. Similarly, relativistic

judgments are ethical evaluations related to tradition or culture. These judgments are also

most likely to be influenced by observed norms of the societal culture in which the

person and organization are embedded (Douglas et al., 2001), as opposed to the role

modeling or sensemaking behaviors of ethical leaders. Fourth, several recent studies

(e.g. Bailey and Spicer, 2007; Rottig et al., 2011; Spicer et al., 2004) have argued that

moral equity judgments are useful for evaluating a wide-range of work-related behaviors

and focused exclusively on the moral equity dimension, and even more specifically on

the fair, just, and morally right items from this dimension, to gauge ethical judgments.

Therefore, in the current study, we assessed employees’ ethical judgments exclusively

from a moral equity perspective using the fair, just, and morally right items.

Moral equity judgments are distinct from similar ethical cognitions, such as moral

awareness, moral attentiveness, and justice perceptions. Moral awareness, which is

widely viewed as the first step toward engaging in ethical conduct (Rest, 1986; Treviño

et al., 2006), represents the determination that a situation has a moral component

(Reynolds, 2006). Moral attentiveness reflects the extent to which a person ‘chronically

perceives and considers morality and moral elements’ in their actions (Reynolds, 2008).

In contrast, moral equity judgments are evaluations of specific actions or events, and are

not chronic approaches to decision-making. In terms of organizational justice, which

examines how people perceive and react to distributive, procedural, and interactional

forms of justice (Greenberg and Colquitt, 2005), moral equity judgments are broader

evaluations that address fairness, justice, and morality.

In the workplace, supervisors are a critical source of proximal information about

normatively appropriate conduct (Brown and Treviño, 2006; Grojean et al., 2004).

Social cognition examines how people interpret social information to make sense of

themselves and others, and use this information to make decisions and take action

(Fiske and Taylor, 1991). When employees view their supervisors acting in an ethical

manner, treating others fairly and respectfully, making ethics-based decisions, and setting

unspoken duties or obligations. The relativistic perspective focuses on the acceptability

of an action or decision based on the contextual norms of the larger society.

In the current study, we focus specifically on the moral equity dimension and exclude

contractualism and relativistic dimensions for several reasons. For one, according to

Reidenbach and Robin (1990), moral equity judgments reflect a broad-based ethical

evaluation that is rooted in theories of justice (Kristol, 1978; Nozick, 1974; Rawls, 1971)

and deontological ethical philosophy (Kant, 1964; Ross, 1930). As such, moral equity

judgments are a form of ethical evaluation that integrates both justice and behavioral

ethics theories. Second, Reidenbach and Robin (1990) argued that moral equity judg-

ments have ‘the greatest relative impact in the evaluation process’ (p. 648), as the focus

on fairness and morality allows for ‘a basic, [and] almost fundamental decision rule for

evaluating the moral context of business decisions’ (p. 695). Third, contractualism and

relativistic perspectives may be less appropriate for understanding the relationship

between ethical leadership and employee ethical judgments. Contractualism judgments

are ethical evaluations related to unspoken contracts or promises. These judgments are

most likely to be influenced by organizational elements such as structure or culture

(Schminke et al., 2000), given that these elements are unspoken or assumed, as opposed

to the direct behaviors or narratives offered by ethical leaders. Similarly, relativistic

judgments are ethical evaluations related to tradition or culture. These judgments are also

most likely to be influenced by observed norms of the societal culture in which the

person and organization are embedded (Douglas et al., 2001), as opposed to the role

modeling or sensemaking behaviors of ethical leaders. Fourth, several recent studies

(e.g. Bailey and Spicer, 2007; Rottig et al., 2011; Spicer et al., 2004) have argued that

moral equity judgments are useful for evaluating a wide-range of work-related behaviors

and focused exclusively on the moral equity dimension, and even more specifically on

the fair, just, and morally right items from this dimension, to gauge ethical judgments.

Therefore, in the current study, we assessed employees’ ethical judgments exclusively

from a moral equity perspective using the fair, just, and morally right items.

Moral equity judgments are distinct from similar ethical cognitions, such as moral

awareness, moral attentiveness, and justice perceptions. Moral awareness, which is

widely viewed as the first step toward engaging in ethical conduct (Rest, 1986; Treviño

et al., 2006), represents the determination that a situation has a moral component

(Reynolds, 2006). Moral attentiveness reflects the extent to which a person ‘chronically

perceives and considers morality and moral elements’ in their actions (Reynolds, 2008).

In contrast, moral equity judgments are evaluations of specific actions or events, and are

not chronic approaches to decision-making. In terms of organizational justice, which

examines how people perceive and react to distributive, procedural, and interactional

forms of justice (Greenberg and Colquitt, 2005), moral equity judgments are broader

evaluations that address fairness, justice, and morality.

In the workplace, supervisors are a critical source of proximal information about

normatively appropriate conduct (Brown and Treviño, 2006; Grojean et al., 2004).

Social cognition examines how people interpret social information to make sense of

themselves and others, and use this information to make decisions and take action

(Fiske and Taylor, 1991). When employees view their supervisors acting in an ethical

manner, treating others fairly and respectfully, making ethics-based decisions, and setting

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Resick et al. 957

ethical standards, they should form a clear understanding of what constitutes fair, just,

and morally appropriate behavior, and the need to consider the ethical appropriateness

of their actions. Drawing on two social cognition processes, social learning and sense-

making, we examine the relationships between ethical leadership and employee moral

equity judgments.

Social learning processes

Social learning theory indicates that individuals are more likely to pay attention to the

behavior of attractive, credible, and high status models that have control over valued

rewards (Bandura, 1977, 1986). In organizations, leaders are role models due to their

status within the organizational hierarchy and their power to control resources. Employees

come to learn what behaviors are ethically appropriate and rewarded, and what actions

are unacceptable and punished by observing leader role models (Brown et al., 2005).

We point to three aspects of social learning theory that help to explain how ethical

leaders influence employees’ ethical judgments. First, Brown et al. (2005: 120) argued

that leaders ‘become attractive, credible, and legitimate as ethical role models’ by con-

sistently demonstrating behaviors that are normatively appropriate, such as being trust-

worthy, making fair decisions, and managing ethical accountability, as well as conveying

prosocial motivation by being open to employee perspectives and treating others in a

considerate and respectful manner. Second, for social learning to occur, individuals need

to pay attention to both the model and behaviors being modeled (Bandura, 1977, 1986).

The actions and decisions of immediate supervisors are generally readily observable, and

those behaviors that are rewarded or punished tend to attract attention (Brown et al.,

2005). Third, social learning is facilitated when individuals understand consequences in

the form of rewards and punishments (Bandura, 1986). Through these processes, ethical

leaders set an example of right and wrong behavior and provide cues that help employees

to determine which courses of action are ethically appropriate (or inappropriate).

Sensemaking processes

A second way that leaders shape ethical judgments is through sensemaking, which

occurs when people confront novel events and engage in a process of constructing

meaning for what has occurred and what people should do (Weick, 1995). More spe-

cifically, sensemaking is a social construction process (Berger and Luckmann, 1966)

in which individuals ‘interpret their environment in and through interactions with

others’ (Maitlis, 2005: 21) to address the question, ‘what does an event mean?’ (Weick

et al., 2005: 410). Narratives are a core mechanism through which sensemaking pro-

cesses occur (Cunliffe and Coupland, 2012; Weick, 2012). Information presented in a

systematic and organized manner, and conveyed with a high degree of animation,

helps people to form a rich understanding of events, and leads to consistency of

behavior (Maitlis, 2005). Leaders engage in sensemaking by monitoring the environ-

ment, interpreting issues and events, and constructing meaning; leaders use sensegiv-

ing to convey information in a manner that captures members’ attention and helps

them to understand events (Gioia and Chittipeddi, 1991; Zaccaro et al., 2001). As

ethical standards, they should form a clear understanding of what constitutes fair, just,

and morally appropriate behavior, and the need to consider the ethical appropriateness

of their actions. Drawing on two social cognition processes, social learning and sense-

making, we examine the relationships between ethical leadership and employee moral

equity judgments.

Social learning processes

Social learning theory indicates that individuals are more likely to pay attention to the

behavior of attractive, credible, and high status models that have control over valued

rewards (Bandura, 1977, 1986). In organizations, leaders are role models due to their

status within the organizational hierarchy and their power to control resources. Employees

come to learn what behaviors are ethically appropriate and rewarded, and what actions

are unacceptable and punished by observing leader role models (Brown et al., 2005).

We point to three aspects of social learning theory that help to explain how ethical

leaders influence employees’ ethical judgments. First, Brown et al. (2005: 120) argued

that leaders ‘become attractive, credible, and legitimate as ethical role models’ by con-

sistently demonstrating behaviors that are normatively appropriate, such as being trust-

worthy, making fair decisions, and managing ethical accountability, as well as conveying

prosocial motivation by being open to employee perspectives and treating others in a

considerate and respectful manner. Second, for social learning to occur, individuals need

to pay attention to both the model and behaviors being modeled (Bandura, 1977, 1986).

The actions and decisions of immediate supervisors are generally readily observable, and

those behaviors that are rewarded or punished tend to attract attention (Brown et al.,

2005). Third, social learning is facilitated when individuals understand consequences in

the form of rewards and punishments (Bandura, 1986). Through these processes, ethical

leaders set an example of right and wrong behavior and provide cues that help employees

to determine which courses of action are ethically appropriate (or inappropriate).

Sensemaking processes

A second way that leaders shape ethical judgments is through sensemaking, which

occurs when people confront novel events and engage in a process of constructing

meaning for what has occurred and what people should do (Weick, 1995). More spe-

cifically, sensemaking is a social construction process (Berger and Luckmann, 1966)

in which individuals ‘interpret their environment in and through interactions with

others’ (Maitlis, 2005: 21) to address the question, ‘what does an event mean?’ (Weick

et al., 2005: 410). Narratives are a core mechanism through which sensemaking pro-

cesses occur (Cunliffe and Coupland, 2012; Weick, 2012). Information presented in a

systematic and organized manner, and conveyed with a high degree of animation,

helps people to form a rich understanding of events, and leads to consistency of

behavior (Maitlis, 2005). Leaders engage in sensemaking by monitoring the environ-

ment, interpreting issues and events, and constructing meaning; leaders use sensegiv-

ing to convey information in a manner that captures members’ attention and helps

them to understand events (Gioia and Chittipeddi, 1991; Zaccaro et al., 2001). As

958 Human Relations 66(7)

such, leaders build, establish legitimacy for, and sustain organizational practices and

norms through sensemaking processes (Maclean et al., 2012; Maitlis, 2005; Gioia and

Thomas, 1996).

Ethical leaders help employees make sense of ethical expectations through the man-

ner in which they convey ethical expectations, implications, and consequences. As

moral people, ethical leaders convey the importance of honesty, integrity and fairness,

as well as being supportive and respectful towards others; as moral managers, ethical

leaders also convey ethical expectations by providing ethical guidance, taking ethical

accountability, and holding others ethically accountable (Brown et al., 2005; Kalshoven

et al., 2011; Resick et al., 2011). One way that ethical leaders engage in sensemaking is

through their retrospective responses (Weick et al., 2005) to ethical transgressions or

other workplace incidents. By presenting their reaction through an organized narrative

that first identifies the critical incidents and responses, and then examines the conse-

quences and implications, ethical leaders help employees make sense of behaviors that

are morally equitable and morally inequitable. Ethical leaders also engage in sensemak-

ing processes through the narratives contained in spontaneous and on-going communi-

cations (Cunliffe and Coupland, 2012) regarding issues such as organizational values,

ethics policies, and general ethical expectations. Through sensemaking processes, ethical

leaders help employees to clearly differentiate between ethically appropriate and inap-

propriate conduct.

Leadership and ethical judgments

By making fair and objective decisions, being approachable and open to new ideas, and

not being malicious or condescending to others, ethical leaders set an example of appro-

priate workplace relations. Ethical leaders also comply with laws and regulations,

establish clear ethics-related guidelines, hold themselves and staff accountable, pay

attention to both process and results, and generally look out for the best interest of

employees and the organization. In summary, employees use these social norms to form

their own ethical evaluations (Bailey and Spicer, 2007; Reidenbach and Robin, 1990).

Thus, through social learning processes, ethical leaders establish social norms and

expectations that employees should treat each other and the organization respectfully,

and that acts of deviance are neither acceptable nor tolerated.

When leaders offer employees retrospective evaluations of ethically-related situa-

tions, or proactive narratives for how to approach ethically-related situations, employees

gain a cognitive anchor that guides future ethically-related judgments. Thus, through

sensemaking processes, ethical leaders help employees to make sense of the expecta-

tions of appropriate and inappropriate conduct and treatment of others. Therefore,

through social learning and sensemaking processes, we expect that employees who

work for ethical leaders to form judgments about acts that are dishonest, reflect a misuse

of company resources, and disrupt workplace relations as being unfair, unjust, and ethi-

cally inappropriate. In contrast, employees who work for supervisors who model fewer

ethical leadership behaviors may form a less clear understanding of the importance of

workplace relations or the negative effects of organization-focused deviance. As leaders

have not conveyed enough information to help employees learn or make sense of social

such, leaders build, establish legitimacy for, and sustain organizational practices and

norms through sensemaking processes (Maclean et al., 2012; Maitlis, 2005; Gioia and

Thomas, 1996).

Ethical leaders help employees make sense of ethical expectations through the man-

ner in which they convey ethical expectations, implications, and consequences. As

moral people, ethical leaders convey the importance of honesty, integrity and fairness,

as well as being supportive and respectful towards others; as moral managers, ethical

leaders also convey ethical expectations by providing ethical guidance, taking ethical

accountability, and holding others ethically accountable (Brown et al., 2005; Kalshoven

et al., 2011; Resick et al., 2011). One way that ethical leaders engage in sensemaking is

through their retrospective responses (Weick et al., 2005) to ethical transgressions or

other workplace incidents. By presenting their reaction through an organized narrative

that first identifies the critical incidents and responses, and then examines the conse-

quences and implications, ethical leaders help employees make sense of behaviors that

are morally equitable and morally inequitable. Ethical leaders also engage in sensemak-

ing processes through the narratives contained in spontaneous and on-going communi-

cations (Cunliffe and Coupland, 2012) regarding issues such as organizational values,

ethics policies, and general ethical expectations. Through sensemaking processes, ethical

leaders help employees to clearly differentiate between ethically appropriate and inap-

propriate conduct.

Leadership and ethical judgments

By making fair and objective decisions, being approachable and open to new ideas, and

not being malicious or condescending to others, ethical leaders set an example of appro-

priate workplace relations. Ethical leaders also comply with laws and regulations,

establish clear ethics-related guidelines, hold themselves and staff accountable, pay

attention to both process and results, and generally look out for the best interest of

employees and the organization. In summary, employees use these social norms to form

their own ethical evaluations (Bailey and Spicer, 2007; Reidenbach and Robin, 1990).

Thus, through social learning processes, ethical leaders establish social norms and

expectations that employees should treat each other and the organization respectfully,

and that acts of deviance are neither acceptable nor tolerated.

When leaders offer employees retrospective evaluations of ethically-related situa-

tions, or proactive narratives for how to approach ethically-related situations, employees

gain a cognitive anchor that guides future ethically-related judgments. Thus, through

sensemaking processes, ethical leaders help employees to make sense of the expecta-

tions of appropriate and inappropriate conduct and treatment of others. Therefore,

through social learning and sensemaking processes, we expect that employees who

work for ethical leaders to form judgments about acts that are dishonest, reflect a misuse

of company resources, and disrupt workplace relations as being unfair, unjust, and ethi-

cally inappropriate. In contrast, employees who work for supervisors who model fewer

ethical leadership behaviors may form a less clear understanding of the importance of

workplace relations or the negative effects of organization-focused deviance. As leaders

have not conveyed enough information to help employees learn or make sense of social

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Resick et al. 959

norms and expectations regarding deviant acts, employees may evaluate the ethicality of

such behavior less harshly. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Ethical leadership is related to negative moral equity judgments of

workplace deviance.

Ethical leaders take personal responsibility for their actions, actively consider the ethi-

cal implications of their behavior, and strive to do the right thing for the collective good

of the organization. By being trustworthy and helpful, treating others with respect, mak-

ing fair decisions, openly discussing ethical issues, and holding people ethically account-

able, ethical leaders are role modeling the importance of good citizenship. Thus, through

social learning processes, ethical leaders establish social norms and expectations that

people should help each other to succeed and treat each other respectfully, and these

norms shape employees’ ethical judgments (Bailey and Spicer, 2007; Reidenbach and

Robin, 1990).

As ethical leaders develop narratives conveying organizational expectations regard-

ing how to interact with co-workers, employees garner a clear cognitive schema that

informs their future evaluations of discretionary helping behavior. Through ethical lead-

ers’ sensemaking, employees form an understanding of how people are expected to coop-

erate and help one another. In turn, through social learning and sensemaking processes,

we expect that employees will evaluate discretionary acts that involve assisting col-

leagues or creating a generally positive work environment as fair, just, and ethically

appropriate. In contrast, we expect that employees who work for supervisors that model

fewer ethical leadership behaviors are less likely to see acts of citizenship in that context

as morally equitable. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Ethical leadership is related to positive moral equity judgments of

organizational citizenship behaviors.

The mediating role of ethical judgments

The actions and decision-making approaches modeled by direct supervisors, coupled

with explicit discussions of ethical norms and values reinforced through reward and

punishment allocations, provide salient cues clarifying ethical expectations. In turn,

through social learning and sensemaking processes, employees form a clear understand-

ing of work-related ethical expectations, and are well-equipped to judge the ethical

appropriateness (or inappropriateness) of potential decisions and behaviors. When ethi-

cal judgments are top of the mind, they create a ‘capacity for action’ that impacts the

types of behaviors that people choose to engage in (Weick et al., 1999: 88).That is, the

normative information conveyed by ethical leaders informs the behaviors and judgments

that employees make, which provides a basis for behavior regulation (Bandura, 1991;

Brown et al., 2005).

Both WPD and OCBs are discretionary behaviors that are under an individual’s con-

trol. Specific, as opposed to general, beliefs and intentions have been found to be most

closely aligned with specific behaviors (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977); therefore, we expect

norms and expectations regarding deviant acts, employees may evaluate the ethicality of

such behavior less harshly. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Ethical leadership is related to negative moral equity judgments of

workplace deviance.

Ethical leaders take personal responsibility for their actions, actively consider the ethi-

cal implications of their behavior, and strive to do the right thing for the collective good

of the organization. By being trustworthy and helpful, treating others with respect, mak-

ing fair decisions, openly discussing ethical issues, and holding people ethically account-

able, ethical leaders are role modeling the importance of good citizenship. Thus, through

social learning processes, ethical leaders establish social norms and expectations that

people should help each other to succeed and treat each other respectfully, and these

norms shape employees’ ethical judgments (Bailey and Spicer, 2007; Reidenbach and

Robin, 1990).

As ethical leaders develop narratives conveying organizational expectations regard-

ing how to interact with co-workers, employees garner a clear cognitive schema that

informs their future evaluations of discretionary helping behavior. Through ethical lead-

ers’ sensemaking, employees form an understanding of how people are expected to coop-

erate and help one another. In turn, through social learning and sensemaking processes,

we expect that employees will evaluate discretionary acts that involve assisting col-

leagues or creating a generally positive work environment as fair, just, and ethically

appropriate. In contrast, we expect that employees who work for supervisors that model

fewer ethical leadership behaviors are less likely to see acts of citizenship in that context

as morally equitable. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Ethical leadership is related to positive moral equity judgments of

organizational citizenship behaviors.

The mediating role of ethical judgments

The actions and decision-making approaches modeled by direct supervisors, coupled

with explicit discussions of ethical norms and values reinforced through reward and

punishment allocations, provide salient cues clarifying ethical expectations. In turn,

through social learning and sensemaking processes, employees form a clear understand-

ing of work-related ethical expectations, and are well-equipped to judge the ethical

appropriateness (or inappropriateness) of potential decisions and behaviors. When ethi-

cal judgments are top of the mind, they create a ‘capacity for action’ that impacts the

types of behaviors that people choose to engage in (Weick et al., 1999: 88).That is, the

normative information conveyed by ethical leaders informs the behaviors and judgments

that employees make, which provides a basis for behavior regulation (Bandura, 1991;

Brown et al., 2005).

Both WPD and OCBs are discretionary behaviors that are under an individual’s con-

trol. Specific, as opposed to general, beliefs and intentions have been found to be most

closely aligned with specific behaviors (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977); therefore, we expect

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

960 Human Relations 66(7)

that ethical judgments of specific sets of discretionary behaviors are likely to be aligned

with engagement in those behaviors. That is, individuals are more likely to avoid acts of

deviance if they judge those acts as morally inequitable. Conversely, people who judge

deviant behaviors less harshly should be more likely to engage in those acts. At the same

time, we expect that employees are more likely to engage in acts of citizenship if they

view those specific acts as morally equitable, and less likely to engage in those acts if

they form less favorable ethical evaluations. We further expect that ethical judgments are

a mediating mechanism linking ethical leadership and employee avoidance of WPD and

engagement in OCBs, and present the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Moral equity judgments of workplace deviance behaviors are positively

related to the engagement in workplace deviance behaviors and mediate the relation-

ship between ethical leadership and workplace deviance.

Hypothesis 4: Moral equity judgments of organizational citizenship behaviors are

positively related to the engagement in organizational citizenship behaviors and medi-

ate the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational citizenship.

Methods

Sample and procedure

We recruited participants through StudyResponse, a non-profit service that matches

social science researchers with individuals willing to complete online surveys (Stanton

and Weiss, 2002). Numerous studies have obtained samples using the StudyResponse

service (e.g. Barnes et al., 2011; Piccolo and Colquitt, 2006). StudyResponse first con-

tacted potential participants to ask if they would be willing to complete a survey, ask

their immediate supervisor to complete a separate survey, and provide a contact email for

their supervisor. StudyResponse then randomly selected a subset of individuals who

indicated ‘yes’ to the first survey and sent them an email inviting them to participate in

the study and provided a link to an online survey containing measures of ethical leadership,

and ethical judgments of WPD and OCBs. StudyResponse also sent a separate email to

the employee’s supervisor with a link to a separate online survey asking them to rate the

employee’s WPD and OCB behaviors. Both employee and supervisor participants

received a US$5.00 gift card to an online store.

Invitations were sent to 255 individuals and their immediate supervisors. We obtained

a final sample of 190 matched pairs (74.5%) after removing cases with incomplete

responses and where the employee and supervisor completed the surveys within 30 min-

utes of one another, which we used to identify and remove potential irregularities.

Employees were predominately male (54%) with a mean age of 36.5, and had worked for

their organization (M = 8.1 years) and supervisor (41% indicating five or more years) at

least one year. Employees represented a variety of occupational types and ethnic back-

grounds (75.3% White/Non-Hispanic; 11.1% Asian; 4.7% Black/African-American;

3.2% Hispanic/Latino; 2.1% Pacific Islander; and 2.1% Native American; 1.5% other/

not identified). The majority of employees (61.4%) indicated their education was a four-

year college degree and 70.7% indicated over five years of work experience. Supervisors

that ethical judgments of specific sets of discretionary behaviors are likely to be aligned

with engagement in those behaviors. That is, individuals are more likely to avoid acts of

deviance if they judge those acts as morally inequitable. Conversely, people who judge

deviant behaviors less harshly should be more likely to engage in those acts. At the same

time, we expect that employees are more likely to engage in acts of citizenship if they

view those specific acts as morally equitable, and less likely to engage in those acts if

they form less favorable ethical evaluations. We further expect that ethical judgments are

a mediating mechanism linking ethical leadership and employee avoidance of WPD and

engagement in OCBs, and present the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Moral equity judgments of workplace deviance behaviors are positively

related to the engagement in workplace deviance behaviors and mediate the relation-

ship between ethical leadership and workplace deviance.

Hypothesis 4: Moral equity judgments of organizational citizenship behaviors are

positively related to the engagement in organizational citizenship behaviors and medi-

ate the relationship between ethical leadership and organizational citizenship.

Methods

Sample and procedure

We recruited participants through StudyResponse, a non-profit service that matches

social science researchers with individuals willing to complete online surveys (Stanton

and Weiss, 2002). Numerous studies have obtained samples using the StudyResponse

service (e.g. Barnes et al., 2011; Piccolo and Colquitt, 2006). StudyResponse first con-

tacted potential participants to ask if they would be willing to complete a survey, ask

their immediate supervisor to complete a separate survey, and provide a contact email for

their supervisor. StudyResponse then randomly selected a subset of individuals who

indicated ‘yes’ to the first survey and sent them an email inviting them to participate in

the study and provided a link to an online survey containing measures of ethical leadership,

and ethical judgments of WPD and OCBs. StudyResponse also sent a separate email to

the employee’s supervisor with a link to a separate online survey asking them to rate the

employee’s WPD and OCB behaviors. Both employee and supervisor participants

received a US$5.00 gift card to an online store.

Invitations were sent to 255 individuals and their immediate supervisors. We obtained

a final sample of 190 matched pairs (74.5%) after removing cases with incomplete

responses and where the employee and supervisor completed the surveys within 30 min-

utes of one another, which we used to identify and remove potential irregularities.

Employees were predominately male (54%) with a mean age of 36.5, and had worked for

their organization (M = 8.1 years) and supervisor (41% indicating five or more years) at

least one year. Employees represented a variety of occupational types and ethnic back-

grounds (75.3% White/Non-Hispanic; 11.1% Asian; 4.7% Black/African-American;

3.2% Hispanic/Latino; 2.1% Pacific Islander; and 2.1% Native American; 1.5% other/

not identified). The majority of employees (61.4%) indicated their education was a four-

year college degree and 70.7% indicated over five years of work experience. Supervisors

Resick et al. 961

were predominately male (67%) with a mean age of 40, and represented a variety of

ethnic backgrounds (79.5% White/Non-Hispanic; 7.4% Asian; 3.7% Latino; 3.7% Black/

African-American; 3.2% Pacific Islander; and 1.6% Native American; 0.9% other/not

identified).

We followed Podsakoff et al.’s (2003) recommendations for minimizing the potential

for socially desirable responding in survey administration. First, the survey introduction

indicated that all responses would be kept private and confidential. Second, the instruc-

tions to each scale indicated that responses would only be used for research purposes,

and stressed the importance of responding honestly. Third, we created a sense of psycho-

logical separation between the leadership and judgment variables by repeating the survey

instructions, and again stressing the importance of honest responding.

Measures

Ethical leadership.We assessed ethical leadership using Brown et al.’s (2005) 10-item

Ethical Leadership Scale (sample item: ‘Discusses business ethics or values with

employees’). Employee participants responded using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 =

he/she never uses this behavior to 5 = he/she uses this behavior very often. Internal con-

sistency reliability was α = .92.

Judgments of WPD.We assessed ethical judgments of WPD by applying Reidenbach and

Robin’s (1990) scale to Bennett and Robinson’s (2000) measure of WPD, which contains

seven items focusing on interpersonal behavior (sample item = I acted rudely toward

someone at work), and 12 items focusing on organization-targeted behavior (sample item

= I neglected to follow my boss’s instructions). Employee participants were presented

each item and asked to judge the behavior depicted as: (a) just, (b) fair, and (c) morally

right on a 1 (e.g. unjust, unfair) to 7 (e.g. just, fair) point range. We excluded Reidenbach

and Robin’s fourth moral equity judgment, ‘acceptable/unacceptable to my family’ for

three reasons. First, this item provides an external referent, which is inconsistent with the

other items. Second, there is a potential for differences to exist in the behaviors that are

acceptable (or unacceptable) at work and to one’s family. Our goal was to assess employ-

ees’ moral equity judgments of work as opposed to non-work behaviors. Third, recent

studies using the moral equity dimension to assess ethical judgments focus exclusively

on these items (see Bailey and Spicer, 2007; Rottig et al., 2011; Spicer et al., 2004). In

total, each employee made 57 moral equity judgment ratings of WPD items; these ratings

were aggregated to the behavior level and then combined across behaviors to create a

WPD moral equity judgment rating. Higher scores indicated that the behaviors were

judged as morally equitable and lower scores indicated the behaviors were judged as not

morally equitable. An acceptable internal consistency reliability across items was found

(α = .98).

Judgments of OCBs.Ethical judgments of OCBs were assessed by applying Reidenbach

and Robin’s (1990) scale to Williams and Anderson’s (1991) 7-item measure of interper-

sonal-targeted OCBs (sample item = helped others who have been absent). Employee

participants were presented with each item, and asked to judge the behavior as: (a) just,

were predominately male (67%) with a mean age of 40, and represented a variety of

ethnic backgrounds (79.5% White/Non-Hispanic; 7.4% Asian; 3.7% Latino; 3.7% Black/

African-American; 3.2% Pacific Islander; and 1.6% Native American; 0.9% other/not

identified).

We followed Podsakoff et al.’s (2003) recommendations for minimizing the potential

for socially desirable responding in survey administration. First, the survey introduction

indicated that all responses would be kept private and confidential. Second, the instruc-

tions to each scale indicated that responses would only be used for research purposes,

and stressed the importance of responding honestly. Third, we created a sense of psycho-

logical separation between the leadership and judgment variables by repeating the survey

instructions, and again stressing the importance of honest responding.

Measures

Ethical leadership.We assessed ethical leadership using Brown et al.’s (2005) 10-item

Ethical Leadership Scale (sample item: ‘Discusses business ethics or values with

employees’). Employee participants responded using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 =

he/she never uses this behavior to 5 = he/she uses this behavior very often. Internal con-

sistency reliability was α = .92.

Judgments of WPD.We assessed ethical judgments of WPD by applying Reidenbach and

Robin’s (1990) scale to Bennett and Robinson’s (2000) measure of WPD, which contains

seven items focusing on interpersonal behavior (sample item = I acted rudely toward

someone at work), and 12 items focusing on organization-targeted behavior (sample item

= I neglected to follow my boss’s instructions). Employee participants were presented

each item and asked to judge the behavior depicted as: (a) just, (b) fair, and (c) morally

right on a 1 (e.g. unjust, unfair) to 7 (e.g. just, fair) point range. We excluded Reidenbach

and Robin’s fourth moral equity judgment, ‘acceptable/unacceptable to my family’ for

three reasons. First, this item provides an external referent, which is inconsistent with the

other items. Second, there is a potential for differences to exist in the behaviors that are

acceptable (or unacceptable) at work and to one’s family. Our goal was to assess employ-

ees’ moral equity judgments of work as opposed to non-work behaviors. Third, recent

studies using the moral equity dimension to assess ethical judgments focus exclusively

on these items (see Bailey and Spicer, 2007; Rottig et al., 2011; Spicer et al., 2004). In

total, each employee made 57 moral equity judgment ratings of WPD items; these ratings

were aggregated to the behavior level and then combined across behaviors to create a

WPD moral equity judgment rating. Higher scores indicated that the behaviors were

judged as morally equitable and lower scores indicated the behaviors were judged as not

morally equitable. An acceptable internal consistency reliability across items was found

(α = .98).

Judgments of OCBs.Ethical judgments of OCBs were assessed by applying Reidenbach

and Robin’s (1990) scale to Williams and Anderson’s (1991) 7-item measure of interper-

sonal-targeted OCBs (sample item = helped others who have been absent). Employee

participants were presented with each item, and asked to judge the behavior as: (a) just,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 23

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.