Product Differentiation: Ethical Arguments in the Organic Food Sector

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/13

|10

|11670

|153

Report

AI Summary

This research report, published in Appetite 62 (2013), investigates promising ethical arguments for product differentiation within the organic food sector. The study employs a mixed methods research approach, combining an Information Display Matrix, Focus Group Discussions, and Choice Experiments across five European countries. The research aims to identify consumer preferences regarding organic food with additional ethical attributes, such as higher animal welfare, local production, and fair producer prices, and assess their relevance in the marketplace. The findings reveal that while consumers generally favor these attributes, the effectiveness of communication strategies varies. The research highlights the potential for product differentiation in the organic sector by exceeding existing minimum regulations and emphasizes the value of a mixed methods approach for gaining comprehensive insights. The study also discusses implications for both researchers and practitioners in the organic food industry, offering insights into consumer behavior and market opportunities.

Research report

Promising ethical arguments for product differentiation in the organic

food sector.A mixed methods research approachq

Katrin Zandera,c,⇑

, Hanna Stolzb, Ulrich Hamma

a Department of Agricultural and Food Marketing at the University of Kassel,Steinstrasse 19,D-37213 Witzenhausen,Germany

b Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) Socio-economic Division,Ackerstrasse,CH-5070 Frick,Switzerland

c Thünen-Institute of Market Analysis,Bundesalle 50,38116 Braunschweig,Germany1

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 2 February 2012

Received in revised form 12 November 2012

Accepted 20 November 2012

Available online 30 November 2012

Keywords:

Organic food

Consumer behaviour

Ethical consumerism

Information Display Matrix

Mixed methods research

Animal welfare

Local production

Fair producer prices

Attitude behaviour gap

a b s t r a c t

Ethical consumerism is a growing trend worldwide.Ethical consumers’expectations are increasing and

neither the Fairtrade nor the organic farming concept covers allthe ethical concerns of consumers.

Against this background the aim of this research is to elicit consumers’preferences regarding organic

food with additional ethical attributes and their relevance at the market place. A mixed methods researc

approach was applied by combining an Information Display Matrix, Focus Group Discussions and Choice

Experiments in five European countries.According to the results of the Information Display Matrix,

‘higher animal welfare’, ‘local production’ and ‘fair producer prices’ were preferred in all countries. These

three attributes were discussed with Focus Groups in depth,using rather emotive ways oflabelling.

While the ranking of the attributes was the same,the emotive way of communicating these attributes

was, for the most part,disliked by participants.The same attributes were then used in Choice Experi-

ments,but with completely revised communication arguments.According to the results of the Focus

Groups,the arguments were presented in a factual manner,using short and concise statements.In this

research step, consumers in all countries except Austria gave priority to ‘local production’. ‘Higher anima

welfare’and ‘fair producer prices’turned out to be relevant for buying decisions only in Germany and

Switzerland.According to our results,there is substantialpotential for product differentiation in the

organic sector through making use of production standards that exceed existing minimum regulations.

The combination of different research methods in a mixed methods approach proved to be very helpful.

The results of earlier research steps provided the basis from which to learn findings could be applied in

subsequent steps,and used to adjust and deepen the research design.

Ó 2012 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Introduction

Ethical consumerism is a growing trend worldwide. Various

studies indicate that consumers are interested in ethicalvalues

and that ethical consumerism is gaining relevance in food pur-

chase decisions (Carrigan, Smizgin, & Wright, 2004; Miele &

Evans, 2010; Newholm & Shaw, 2007; Shaw & Shiu, 2001;

Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006). Examples of ethical consumerism

in the food market are ‘Fairtrade’and (partly) organic products,

which have exhibited impressive growth rates during recent

years.2 The Fairtrade market in Germany increased by 50% be-

tween 2007 and 2008 (Crescenti, 2009) and by 27% from 2009

to 2010 (Rößler, 2011). In the UK, sales of Fairtrade products in-

creased from 16.7 million GBP in 1998 to 799.0 million GBP in

2009 (Fairtrade Foundation,2011). In Switzerland, the Max Have-

laar Foundation reported a growth in sales of 8% between 2010

and 2011 (Max Havelaar-Stiftung, 2011). Similar developments

have taken place in the organic food sector. The turnover of

the global market for organic food has increased by 200% from

17.9 billion USD in 2000, to 54.9 billion USD in 2009 (Sahota,

0195-6663/$ - see front matter Ó 2012 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.11.015

q Acknowledgments: The authors greatly appreciate the helpful comments of three

anonymous reviewers and gratefully acknowledge the financialsupport for this

research provided by the members of the CORE Organic Funding Body Network,

being former partners of the FP6 ERA-NET Project,CORE Organic (Coordination of

European Transnational Research in Organic Food and Farming,EU FP6 Project No.

011716).

⇑ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: katrin.zander@vti.bund.de (K.Zander).

1 Present address.

2 Organic food is also consumed for personalreasons,of which health consider-

ations are most important (see e.g. Aertsens, Verbeke, Mondelaers, & van

Huylenbroeck, 2009; Hughner, McDonagh, Prothero, Shultz, & Stanton, 2007; Pearson,

Henryks,& Jones,2010).

Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Appetite

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / a p p e t

Promising ethical arguments for product differentiation in the organic

food sector.A mixed methods research approachq

Katrin Zandera,c,⇑

, Hanna Stolzb, Ulrich Hamma

a Department of Agricultural and Food Marketing at the University of Kassel,Steinstrasse 19,D-37213 Witzenhausen,Germany

b Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) Socio-economic Division,Ackerstrasse,CH-5070 Frick,Switzerland

c Thünen-Institute of Market Analysis,Bundesalle 50,38116 Braunschweig,Germany1

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 2 February 2012

Received in revised form 12 November 2012

Accepted 20 November 2012

Available online 30 November 2012

Keywords:

Organic food

Consumer behaviour

Ethical consumerism

Information Display Matrix

Mixed methods research

Animal welfare

Local production

Fair producer prices

Attitude behaviour gap

a b s t r a c t

Ethical consumerism is a growing trend worldwide.Ethical consumers’expectations are increasing and

neither the Fairtrade nor the organic farming concept covers allthe ethical concerns of consumers.

Against this background the aim of this research is to elicit consumers’preferences regarding organic

food with additional ethical attributes and their relevance at the market place. A mixed methods researc

approach was applied by combining an Information Display Matrix, Focus Group Discussions and Choice

Experiments in five European countries.According to the results of the Information Display Matrix,

‘higher animal welfare’, ‘local production’ and ‘fair producer prices’ were preferred in all countries. These

three attributes were discussed with Focus Groups in depth,using rather emotive ways oflabelling.

While the ranking of the attributes was the same,the emotive way of communicating these attributes

was, for the most part,disliked by participants.The same attributes were then used in Choice Experi-

ments,but with completely revised communication arguments.According to the results of the Focus

Groups,the arguments were presented in a factual manner,using short and concise statements.In this

research step, consumers in all countries except Austria gave priority to ‘local production’. ‘Higher anima

welfare’and ‘fair producer prices’turned out to be relevant for buying decisions only in Germany and

Switzerland.According to our results,there is substantialpotential for product differentiation in the

organic sector through making use of production standards that exceed existing minimum regulations.

The combination of different research methods in a mixed methods approach proved to be very helpful.

The results of earlier research steps provided the basis from which to learn findings could be applied in

subsequent steps,and used to adjust and deepen the research design.

Ó 2012 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

Introduction

Ethical consumerism is a growing trend worldwide. Various

studies indicate that consumers are interested in ethicalvalues

and that ethical consumerism is gaining relevance in food pur-

chase decisions (Carrigan, Smizgin, & Wright, 2004; Miele &

Evans, 2010; Newholm & Shaw, 2007; Shaw & Shiu, 2001;

Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006). Examples of ethical consumerism

in the food market are ‘Fairtrade’and (partly) organic products,

which have exhibited impressive growth rates during recent

years.2 The Fairtrade market in Germany increased by 50% be-

tween 2007 and 2008 (Crescenti, 2009) and by 27% from 2009

to 2010 (Rößler, 2011). In the UK, sales of Fairtrade products in-

creased from 16.7 million GBP in 1998 to 799.0 million GBP in

2009 (Fairtrade Foundation,2011). In Switzerland, the Max Have-

laar Foundation reported a growth in sales of 8% between 2010

and 2011 (Max Havelaar-Stiftung, 2011). Similar developments

have taken place in the organic food sector. The turnover of

the global market for organic food has increased by 200% from

17.9 billion USD in 2000, to 54.9 billion USD in 2009 (Sahota,

0195-6663/$ - see front matter Ó 2012 Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.11.015

q Acknowledgments: The authors greatly appreciate the helpful comments of three

anonymous reviewers and gratefully acknowledge the financialsupport for this

research provided by the members of the CORE Organic Funding Body Network,

being former partners of the FP6 ERA-NET Project,CORE Organic (Coordination of

European Transnational Research in Organic Food and Farming,EU FP6 Project No.

011716).

⇑ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: katrin.zander@vti.bund.de (K.Zander).

1 Present address.

2 Organic food is also consumed for personalreasons,of which health consider-

ations are most important (see e.g. Aertsens, Verbeke, Mondelaers, & van

Huylenbroeck, 2009; Hughner, McDonagh, Prothero, Shultz, & Stanton, 2007; Pearson,

Henryks,& Jones,2010).

Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Appetite

j o u r n a lhomepage: w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / a p p e t

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2011). The growth of organic markets between 2000 and 2009

was also impressive in European countries: 183% in Germany

(AMI, 2011), 129% in the UK (Soil Association, 2010) and 90%

in Switzerland (FiBL, 2010). However, market shares for both

markets are still small: the share of organic in all food sales in

2010 were at about 6.0% in Austria, 5.7% in Switzerland and

3.5% in Germany (Willer,2012). The market volume for fair trade

products is even less and at about one sixth of the organic mar-

ket in Germany (Der Handel, 2012; Schaack, Willer, & Padel,

2011), one third in Switzerland (Max Havelaar-Stiftung, 2011;

Schaack et al., 2011) and three quarters in the UK (CNN, 2012;

Schaack et al., 2011).

Neither of these ethical market segments is independentof

the other and a growing share of products is certified according

to both Fairtrade and organic farming standards. At the same

time, in the organic sector,more and more consumers seem to

be dissatisfied with anonymous,homogenous organic food prod-

ucts, which may be produced under unknown socialconditions.

They want greater traceability and information about the diverse

origins and conditions under which organic food is produced,

and from where and how it is transported. Thus, neither the

Fairtrade nor the organic farming concept covers allthe ethical

concerns ofconsumers.

But what are the ethical concerns of (organic) food consumers?

Although research has shown that consumers of organic food know

only little about organic production standards (Janssen & Hamm,

2011), they have their own expectations aboutthe production

methods of the organic products they buy. These expectations

are related to animal welfare,support for local production struc-

tures and the well-being of those engaged in food production

(Aschemann & Hamm,2007; Browne,Harris, Hofny-Collins,Pas-

iecznik, & Wallace,2000; Goig,2007; Hughner et al.,2007; Lusk

& Briggeman, 2009; Ozcaglar-Toulouse, Shiu, & Shaw, 2006; Torju-

sen,Sangstad,O’Doherty Jensen,& Kjærnes,2004).Generally,or-

ganic consumers are characterised by a strong interest in

deliberate pro-socialbehaviour (Spiller & Lüth,2004; Sylvander

& François,2006; Zanoli et al.,2004).Padel and Gössinger (2008)

categorised the various ethical concerns (additional to common or-

ganic farming standards) according to the three pillars of

sustainability.

Social issues,such as fair, safe and equitable working condi-

tions, ban on child labour and exploitation of foreign workers,

employment of disabled people,re-integration of drug addicts

or delinquents.

Environmental issues, such as protection of natural resources,

water,soil, biodiversity or climate as well as conservation and

enhancement of landscapes.

Economic issues, such as fair prices for organic farmers,manu-

facturers or retailers, long-term contracts for smaller farms,

processing or trading companies, support for enterprises in dis-

advantaged or mountainous regions.

Other issues which might be summarised under the term spiri-

tual (or cultural) concerns,such as cultural or religious convic-

tions or the preservation of specific agricultural or

manufacturing traditions. The well-being of farm animals

would also be part of this category.

Local production is difficult to assign to one of these categories

since environmental,such as short transport distances,as well as

economic and culturalaspects are associated with it (Roinenen,

Arvola,& Lähteenmäki,2006).

While, on the one hand,organic consumers’interest in ‘ethical

consumption’is increasing,on the other hand organic production

is subject to growing international competition and price pressure.

In order to survive growing internationalcompetition,more and

more European farmers try to minimise production costs by orient-

ing their production systems towards minimum organic standards,

for example,according to the EU Regulation on Organic Farming

834/2007.These standards concentrate on environmental aspects

and some animal welfare concerns but do not cover further ethical

concerns,such as social aspects or local production.Accordingly,

actual production methods and ways of distribution might be quite

different from what consumers expect.At the same time,farmers

might engage in production methods which meet standards signif-

icantly higher than what is required by the EU Reg.on Organic

Farming or other standards.In order to secure competitiveness

they need to know how to efficiently communicate their additional

efforts to consumers.In any case,organic farmers and processors

need to care about adjusting and communicating their production

methods in line with customers’ concerns, in order to remain cred-

ible and to secure,or even increase,market shares.Organic pro-

duction according to standards that are higher than those of the

named EU Reg.can be assumed to offer additionalopportunities

for product differentiation within the organic market, such as local

production,higher animal welfare standards,improved biodiver-

sity and other.

Previous research has indicated that consumer concerns

regarding organic food vary between countries.However, most

studies have focused only on one country and different studies

use different methodological approaches.Therefore,the question

of whether variation between countries is due to culturalmat-

ters or due to the use of different research methods still re-

mains open. The research presented in this paper consists ofa

cross-country comparison between five European countries

(Austria, Germany,Italy, Switzerland and the United Kingdom),

employing exactly the same methodologicalapproaches in each

country.

The aim of this contribution is threefold: first,to identify the

three additionalethical attributes which are ofmost interest to

consumers of organic food,second,to discuss with consumers on

ways to successfully communicate these attributes, and third to as-

sess the relevance of these attributes in purchase decisions. For this

purpose,‘mixed methods research’was used which combined dif-

ferent methodological approaches in order to systematically ana-

lyse consumer preferences step by step as well as from different

perspectives.

Section ‘‘Methodological approach’’of this article describes the

different methods that were combined in order to meet the aims of

this contribution.Section ‘‘Consumers’preferences for additional

ethical attributes of organic food’’presents and discusses the re-

sults according to the research methods employed.The paper

closes with a discussion of conclusions for researchers regarding

the use of the mixed methods research approach, and for practitio-

ners regarding the opportunities for product differentiation within

the organic market.

Methodological approach

The research was undertaken in severalsteps,since the task

was to derive specific, promising ‘communication arguments’

from the wide and foggy array of ethical concerns in the organic

sector.This is why a mixed methods research approach (MMR)

was used, combining quantitative and qualitative methods in a

subsequent manner.Typically,MMR brings both of these meth-

ods together within the same research project(Bryman,2004),

neglecting the traditional premise of using either exclusively

quantitative or qualitative methodology (Teddlie & Tashakkori,

2010).MMR offers the possibility of different perspectives in or-

der to increase the validity of results and to increase confidence,

and/or to make use of the convergent or complementary effect

134 K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142

was also impressive in European countries: 183% in Germany

(AMI, 2011), 129% in the UK (Soil Association, 2010) and 90%

in Switzerland (FiBL, 2010). However, market shares for both

markets are still small: the share of organic in all food sales in

2010 were at about 6.0% in Austria, 5.7% in Switzerland and

3.5% in Germany (Willer,2012). The market volume for fair trade

products is even less and at about one sixth of the organic mar-

ket in Germany (Der Handel, 2012; Schaack, Willer, & Padel,

2011), one third in Switzerland (Max Havelaar-Stiftung, 2011;

Schaack et al., 2011) and three quarters in the UK (CNN, 2012;

Schaack et al., 2011).

Neither of these ethical market segments is independentof

the other and a growing share of products is certified according

to both Fairtrade and organic farming standards. At the same

time, in the organic sector,more and more consumers seem to

be dissatisfied with anonymous,homogenous organic food prod-

ucts, which may be produced under unknown socialconditions.

They want greater traceability and information about the diverse

origins and conditions under which organic food is produced,

and from where and how it is transported. Thus, neither the

Fairtrade nor the organic farming concept covers allthe ethical

concerns ofconsumers.

But what are the ethical concerns of (organic) food consumers?

Although research has shown that consumers of organic food know

only little about organic production standards (Janssen & Hamm,

2011), they have their own expectations aboutthe production

methods of the organic products they buy. These expectations

are related to animal welfare,support for local production struc-

tures and the well-being of those engaged in food production

(Aschemann & Hamm,2007; Browne,Harris, Hofny-Collins,Pas-

iecznik, & Wallace,2000; Goig,2007; Hughner et al.,2007; Lusk

& Briggeman, 2009; Ozcaglar-Toulouse, Shiu, & Shaw, 2006; Torju-

sen,Sangstad,O’Doherty Jensen,& Kjærnes,2004).Generally,or-

ganic consumers are characterised by a strong interest in

deliberate pro-socialbehaviour (Spiller & Lüth,2004; Sylvander

& François,2006; Zanoli et al.,2004).Padel and Gössinger (2008)

categorised the various ethical concerns (additional to common or-

ganic farming standards) according to the three pillars of

sustainability.

Social issues,such as fair, safe and equitable working condi-

tions, ban on child labour and exploitation of foreign workers,

employment of disabled people,re-integration of drug addicts

or delinquents.

Environmental issues, such as protection of natural resources,

water,soil, biodiversity or climate as well as conservation and

enhancement of landscapes.

Economic issues, such as fair prices for organic farmers,manu-

facturers or retailers, long-term contracts for smaller farms,

processing or trading companies, support for enterprises in dis-

advantaged or mountainous regions.

Other issues which might be summarised under the term spiri-

tual (or cultural) concerns,such as cultural or religious convic-

tions or the preservation of specific agricultural or

manufacturing traditions. The well-being of farm animals

would also be part of this category.

Local production is difficult to assign to one of these categories

since environmental,such as short transport distances,as well as

economic and culturalaspects are associated with it (Roinenen,

Arvola,& Lähteenmäki,2006).

While, on the one hand,organic consumers’interest in ‘ethical

consumption’is increasing,on the other hand organic production

is subject to growing international competition and price pressure.

In order to survive growing internationalcompetition,more and

more European farmers try to minimise production costs by orient-

ing their production systems towards minimum organic standards,

for example,according to the EU Regulation on Organic Farming

834/2007.These standards concentrate on environmental aspects

and some animal welfare concerns but do not cover further ethical

concerns,such as social aspects or local production.Accordingly,

actual production methods and ways of distribution might be quite

different from what consumers expect.At the same time,farmers

might engage in production methods which meet standards signif-

icantly higher than what is required by the EU Reg.on Organic

Farming or other standards.In order to secure competitiveness

they need to know how to efficiently communicate their additional

efforts to consumers.In any case,organic farmers and processors

need to care about adjusting and communicating their production

methods in line with customers’ concerns, in order to remain cred-

ible and to secure,or even increase,market shares.Organic pro-

duction according to standards that are higher than those of the

named EU Reg.can be assumed to offer additionalopportunities

for product differentiation within the organic market, such as local

production,higher animal welfare standards,improved biodiver-

sity and other.

Previous research has indicated that consumer concerns

regarding organic food vary between countries.However, most

studies have focused only on one country and different studies

use different methodological approaches.Therefore,the question

of whether variation between countries is due to culturalmat-

ters or due to the use of different research methods still re-

mains open. The research presented in this paper consists ofa

cross-country comparison between five European countries

(Austria, Germany,Italy, Switzerland and the United Kingdom),

employing exactly the same methodologicalapproaches in each

country.

The aim of this contribution is threefold: first,to identify the

three additionalethical attributes which are ofmost interest to

consumers of organic food,second,to discuss with consumers on

ways to successfully communicate these attributes, and third to as-

sess the relevance of these attributes in purchase decisions. For this

purpose,‘mixed methods research’was used which combined dif-

ferent methodological approaches in order to systematically ana-

lyse consumer preferences step by step as well as from different

perspectives.

Section ‘‘Methodological approach’’of this article describes the

different methods that were combined in order to meet the aims of

this contribution.Section ‘‘Consumers’preferences for additional

ethical attributes of organic food’’presents and discusses the re-

sults according to the research methods employed.The paper

closes with a discussion of conclusions for researchers regarding

the use of the mixed methods research approach, and for practitio-

ners regarding the opportunities for product differentiation within

the organic market.

Methodological approach

The research was undertaken in severalsteps,since the task

was to derive specific, promising ‘communication arguments’

from the wide and foggy array of ethical concerns in the organic

sector.This is why a mixed methods research approach (MMR)

was used, combining quantitative and qualitative methods in a

subsequent manner.Typically,MMR brings both of these meth-

ods together within the same research project(Bryman,2004),

neglecting the traditional premise of using either exclusively

quantitative or qualitative methodology (Teddlie & Tashakkori,

2010).MMR offers the possibility of different perspectives in or-

der to increase the validity of results and to increase confidence,

and/or to make use of the convergent or complementary effect

134 K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142

of different approaches.Another issue is that of including and

drawing out the various aspects in order to obtain a differenti-

ated picture of the whole (Bryman, 2006). ‘‘The key goal in

studies that pursue complementarity is to use the strengths of

one method to enhance the performance ofthe other method’’

(Morgan,1998: 365).The use of separated studies,distinct from

each other but linked by a joint superior topic,also falls under

the MMR approach (Brennan, 2000). The choice of the most

appropriate method and mix of methods out of the large number

of options depends on the research topic under question (Teddlie

& Tashakkori, 2010). Greene, Caracelli, and Graham (1989)

identify five reasons for mixing different research methods: tri-

angulation,complementarity,development,initiation and expan-

sion. Within this study, the advantage of using a combination of

different methods laid in ‘development’,because insights were

generated at each step of the research which enabled the specific

design of the next.

By employing an MMR approach,the relevance ofadditional

ethical concerns for organic consumers was analysed systemati-

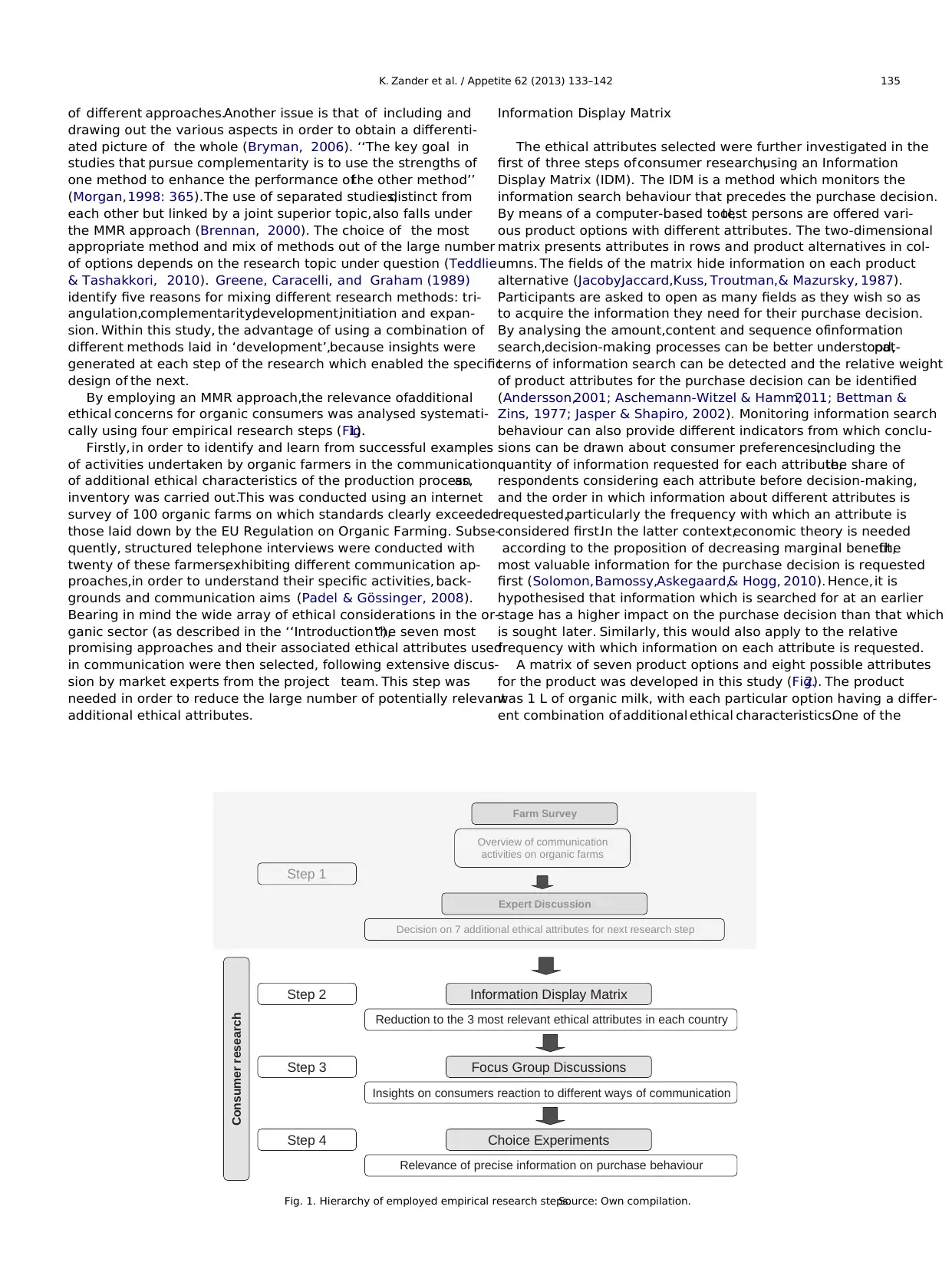

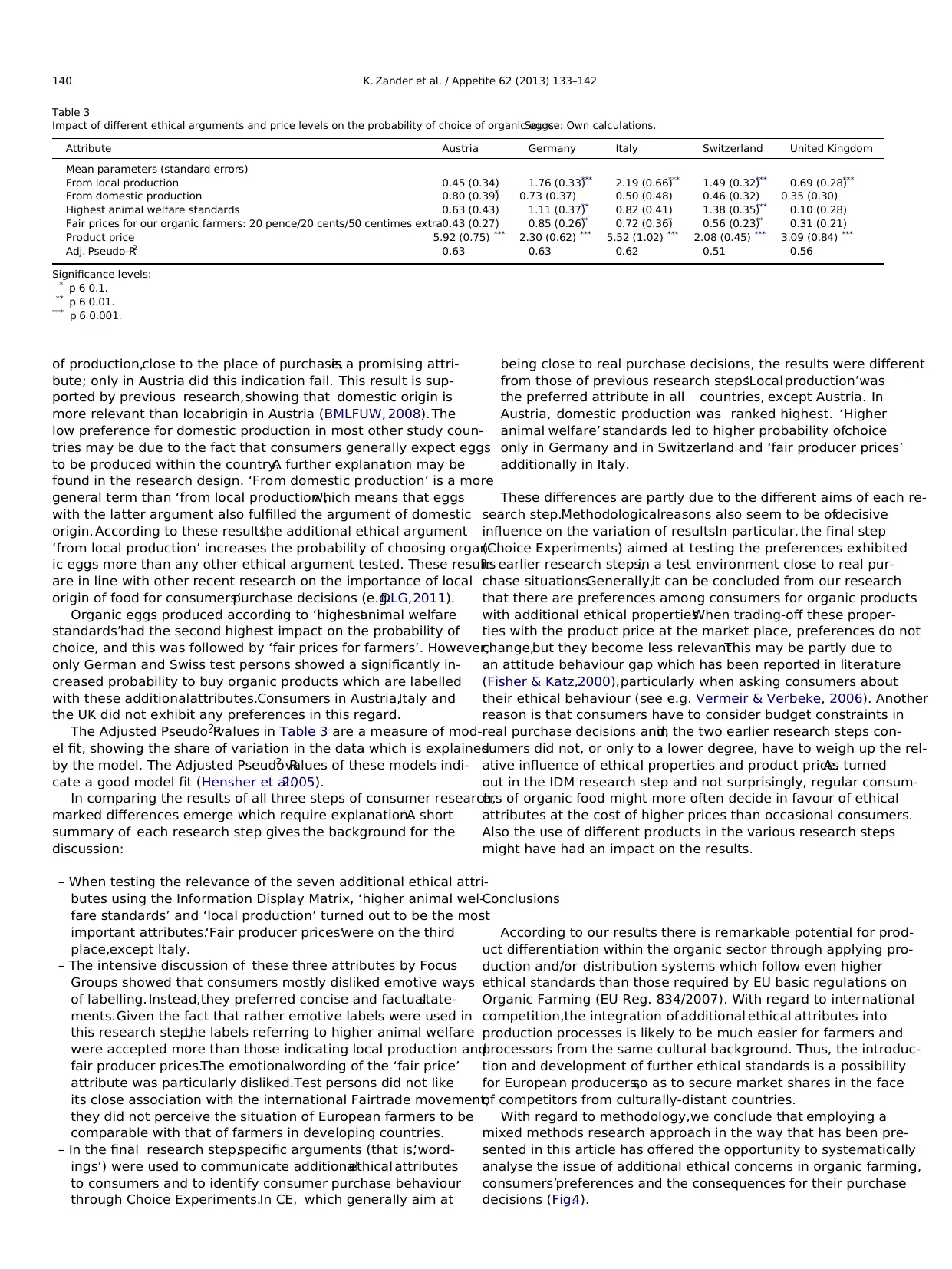

cally using four empirical research steps (Fig.1).

Firstly,in order to identify and learn from successful examples

of activities undertaken by organic farmers in the communication

of additional ethical characteristics of the production process,an

inventory was carried out.This was conducted using an internet

survey of 100 organic farms on which standards clearly exceeded

those laid down by the EU Regulation on Organic Farming. Subse-

quently, structured telephone interviews were conducted with

twenty of these farmers,exhibiting different communication ap-

proaches,in order to understand their specific activities, back-

grounds and communication aims (Padel & Gössinger, 2008).

Bearing in mind the wide array of ethical considerations in the or-

ganic sector (as described in the ‘‘Introduction’’),the seven most

promising approaches and their associated ethical attributes used

in communication were then selected, following extensive discus-

sion by market experts from the project team. This step was

needed in order to reduce the large number of potentially relevant

additional ethical attributes.

Information Display Matrix

The ethical attributes selected were further investigated in the

first of three steps ofconsumer research,using an Information

Display Matrix (IDM). The IDM is a method which monitors the

information search behaviour that precedes the purchase decision.

By means of a computer-based tool,test persons are offered vari-

ous product options with different attributes. The two-dimensional

matrix presents attributes in rows and product alternatives in col-

umns. The fields of the matrix hide information on each product

alternative (Jacoby,Jaccard,Kuss, Troutman,& Mazursky, 1987).

Participants are asked to open as many fields as they wish so as

to acquire the information they need for their purchase decision.

By analysing the amount,content and sequence ofinformation

search,decision-making processes can be better understood,pat-

terns of information search can be detected and the relative weight

of product attributes for the purchase decision can be identified

(Andersson,2001; Aschemann-Witzel & Hamm,2011; Bettman &

Zins, 1977; Jasper & Shapiro, 2002). Monitoring information search

behaviour can also provide different indicators from which conclu-

sions can be drawn about consumer preferences,including the

quantity of information requested for each attribute,the share of

respondents considering each attribute before decision-making,

and the order in which information about different attributes is

requested,particularly the frequency with which an attribute is

considered first.In the latter context,economic theory is needed

according to the proposition of decreasing marginal benefit,the

most valuable information for the purchase decision is requested

first (Solomon,Bamossy,Askegaard,& Hogg, 2010). Hence,it is

hypothesised that information which is searched for at an earlier

stage has a higher impact on the purchase decision than that which

is sought later. Similarly, this would also apply to the relative

frequency with which information on each attribute is requested.

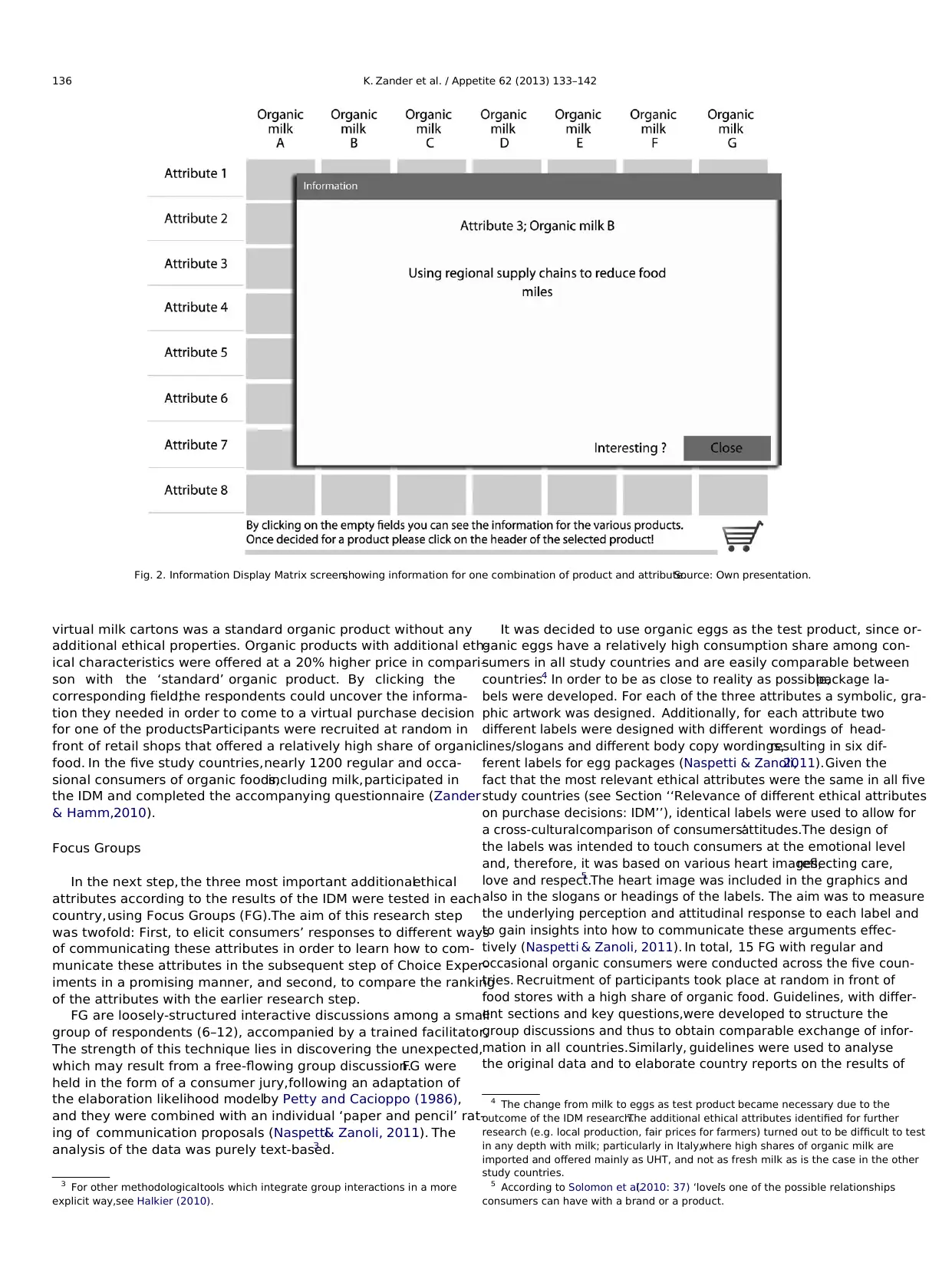

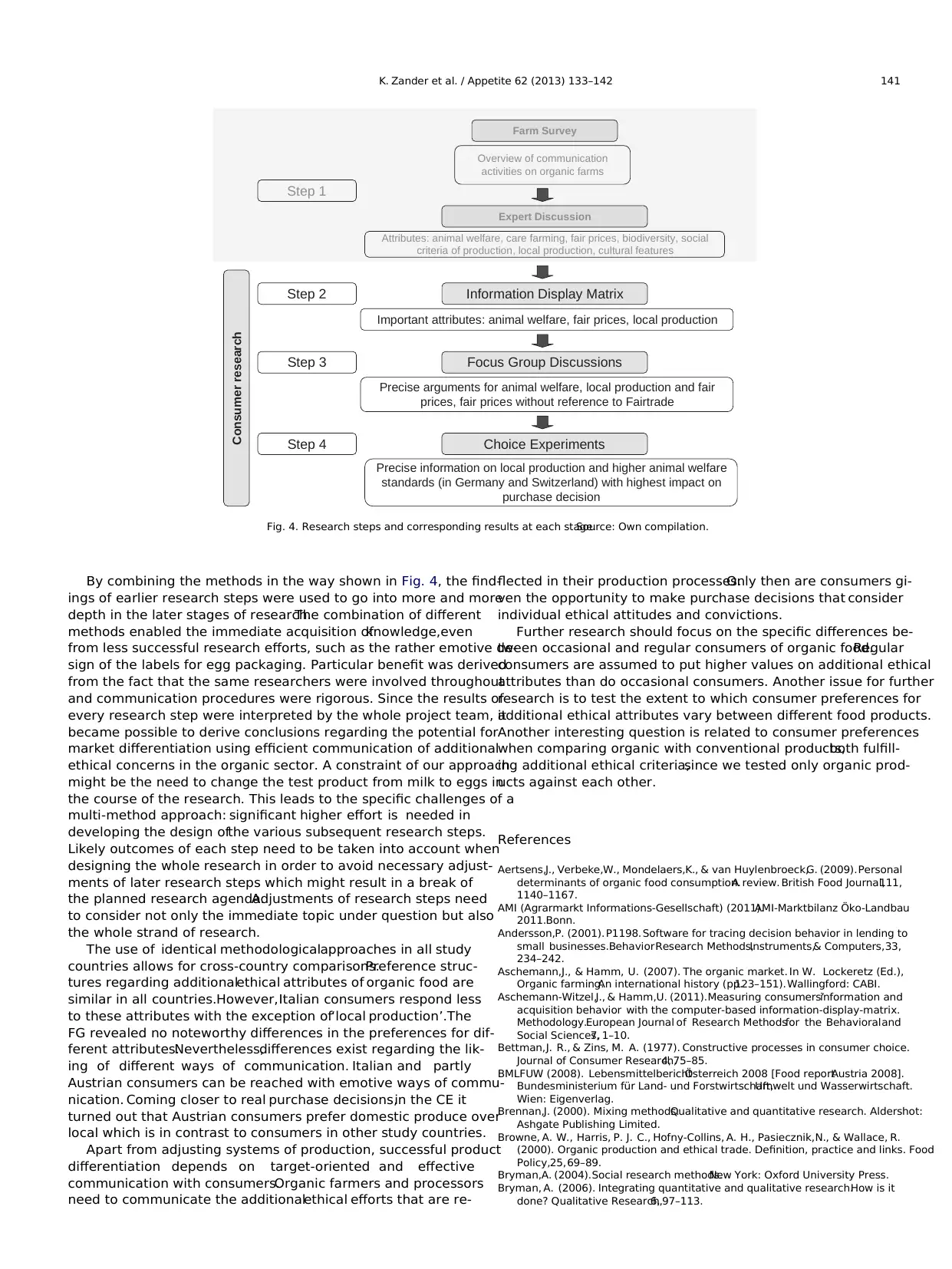

A matrix of seven product options and eight possible attributes

for the product was developed in this study (Fig.2). The product

was 1 L of organic milk, with each particular option having a differ-

ent combination of additional ethical characteristics.One of the

Step 1

Farm Survey

Overview of communication

activities on organic farms

Step 2

Step 3

Step 4

Information Display Matrix

Expert Discussion

Decision on 7 additional ethical attributes for next research step

Reduction to the 3 most relevant ethical attributes in each country

Consumer research

Focus Group Discussions

Insights on consumers reaction to different ways of communication

Choice Experiments

Relevance of precise information on purchase behaviour

Fig. 1. Hierarchy of employed empirical research steps.Source: Own compilation.

K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142 135

drawing out the various aspects in order to obtain a differenti-

ated picture of the whole (Bryman, 2006). ‘‘The key goal in

studies that pursue complementarity is to use the strengths of

one method to enhance the performance ofthe other method’’

(Morgan,1998: 365).The use of separated studies,distinct from

each other but linked by a joint superior topic,also falls under

the MMR approach (Brennan, 2000). The choice of the most

appropriate method and mix of methods out of the large number

of options depends on the research topic under question (Teddlie

& Tashakkori, 2010). Greene, Caracelli, and Graham (1989)

identify five reasons for mixing different research methods: tri-

angulation,complementarity,development,initiation and expan-

sion. Within this study, the advantage of using a combination of

different methods laid in ‘development’,because insights were

generated at each step of the research which enabled the specific

design of the next.

By employing an MMR approach,the relevance ofadditional

ethical concerns for organic consumers was analysed systemati-

cally using four empirical research steps (Fig.1).

Firstly,in order to identify and learn from successful examples

of activities undertaken by organic farmers in the communication

of additional ethical characteristics of the production process,an

inventory was carried out.This was conducted using an internet

survey of 100 organic farms on which standards clearly exceeded

those laid down by the EU Regulation on Organic Farming. Subse-

quently, structured telephone interviews were conducted with

twenty of these farmers,exhibiting different communication ap-

proaches,in order to understand their specific activities, back-

grounds and communication aims (Padel & Gössinger, 2008).

Bearing in mind the wide array of ethical considerations in the or-

ganic sector (as described in the ‘‘Introduction’’),the seven most

promising approaches and their associated ethical attributes used

in communication were then selected, following extensive discus-

sion by market experts from the project team. This step was

needed in order to reduce the large number of potentially relevant

additional ethical attributes.

Information Display Matrix

The ethical attributes selected were further investigated in the

first of three steps ofconsumer research,using an Information

Display Matrix (IDM). The IDM is a method which monitors the

information search behaviour that precedes the purchase decision.

By means of a computer-based tool,test persons are offered vari-

ous product options with different attributes. The two-dimensional

matrix presents attributes in rows and product alternatives in col-

umns. The fields of the matrix hide information on each product

alternative (Jacoby,Jaccard,Kuss, Troutman,& Mazursky, 1987).

Participants are asked to open as many fields as they wish so as

to acquire the information they need for their purchase decision.

By analysing the amount,content and sequence ofinformation

search,decision-making processes can be better understood,pat-

terns of information search can be detected and the relative weight

of product attributes for the purchase decision can be identified

(Andersson,2001; Aschemann-Witzel & Hamm,2011; Bettman &

Zins, 1977; Jasper & Shapiro, 2002). Monitoring information search

behaviour can also provide different indicators from which conclu-

sions can be drawn about consumer preferences,including the

quantity of information requested for each attribute,the share of

respondents considering each attribute before decision-making,

and the order in which information about different attributes is

requested,particularly the frequency with which an attribute is

considered first.In the latter context,economic theory is needed

according to the proposition of decreasing marginal benefit,the

most valuable information for the purchase decision is requested

first (Solomon,Bamossy,Askegaard,& Hogg, 2010). Hence,it is

hypothesised that information which is searched for at an earlier

stage has a higher impact on the purchase decision than that which

is sought later. Similarly, this would also apply to the relative

frequency with which information on each attribute is requested.

A matrix of seven product options and eight possible attributes

for the product was developed in this study (Fig.2). The product

was 1 L of organic milk, with each particular option having a differ-

ent combination of additional ethical characteristics.One of the

Step 1

Farm Survey

Overview of communication

activities on organic farms

Step 2

Step 3

Step 4

Information Display Matrix

Expert Discussion

Decision on 7 additional ethical attributes for next research step

Reduction to the 3 most relevant ethical attributes in each country

Consumer research

Focus Group Discussions

Insights on consumers reaction to different ways of communication

Choice Experiments

Relevance of precise information on purchase behaviour

Fig. 1. Hierarchy of employed empirical research steps.Source: Own compilation.

K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142 135

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

virtual milk cartons was a standard organic product without any

additional ethical properties. Organic products with additional eth-

ical characteristics were offered at a 20% higher price in compari-

son with the ‘standard’ organic product. By clicking the

corresponding field,the respondents could uncover the informa-

tion they needed in order to come to a virtual purchase decision

for one of the products.Participants were recruited at random in

front of retail shops that offered a relatively high share of organic

food. In the five study countries,nearly 1200 regular and occa-

sional consumers of organic foods,including milk,participated in

the IDM and completed the accompanying questionnaire (Zander

& Hamm,2010).

Focus Groups

In the next step, the three most important additionalethical

attributes according to the results of the IDM were tested in each

country,using Focus Groups (FG).The aim of this research step

was twofold: First, to elicit consumers’ responses to different ways

of communicating these attributes in order to learn how to com-

municate these attributes in the subsequent step of Choice Exper-

iments in a promising manner, and second, to compare the ranking

of the attributes with the earlier research step.

FG are loosely-structured interactive discussions among a small

group of respondents (6–12), accompanied by a trained facilitator.

The strength of this technique lies in discovering the unexpected,

which may result from a free-flowing group discussion.FG were

held in the form of a consumer jury,following an adaptation of

the elaboration likelihood modelby Petty and Cacioppo (1986),

and they were combined with an individual ‘paper and pencil’ rat-

ing of communication proposals (Naspetti& Zanoli, 2011). The

analysis of the data was purely text-based.3

It was decided to use organic eggs as the test product, since or-

ganic eggs have a relatively high consumption share among con-

sumers in all study countries and are easily comparable between

countries.4 In order to be as close to reality as possible,package la-

bels were developed. For each of the three attributes a symbolic, gra-

phic artwork was designed. Additionally, for each attribute two

different labels were designed with different wordings of head-

lines/slogans and different body copy wordings,resulting in six dif-

ferent labels for egg packages (Naspetti & Zanoli,2011).Given the

fact that the most relevant ethical attributes were the same in all five

study countries (see Section ‘‘Relevance of different ethical attributes

on purchase decisions: IDM’’), identical labels were used to allow for

a cross-culturalcomparison of consumers’attitudes.The design of

the labels was intended to touch consumers at the emotional level

and, therefore, it was based on various heart images,reflecting care,

love and respect.5 The heart image was included in the graphics and

also in the slogans or headings of the labels. The aim was to measure

the underlying perception and attitudinal response to each label and

to gain insights into how to communicate these arguments effec-

tively (Naspetti & Zanoli, 2011). In total, 15 FG with regular and

occasional organic consumers were conducted across the five coun-

tries. Recruitment of participants took place at random in front of

food stores with a high share of organic food. Guidelines, with differ-

ent sections and key questions,were developed to structure the

group discussions and thus to obtain comparable exchange of infor-

mation in all countries.Similarly, guidelines were used to analyse

the original data and to elaborate country reports on the results of

Fig. 2. Information Display Matrix screen,showing information for one combination of product and attribute.Source: Own presentation.

3 For other methodologicaltools which integrate group interactions in a more

explicit way,see Halkier (2010).

4 The change from milk to eggs as test product became necessary due to the

outcome of the IDM research.The additional ethical attributes identified for further

research (e.g. local production, fair prices for farmers) turned out to be difficult to test

in any depth with milk; particularly in Italy,where high shares of organic milk are

imported and offered mainly as UHT, and not as fresh milk as is the case in the other

study countries.

5 According to Solomon et al.(2010: 37) ‘love’is one of the possible relationships

consumers can have with a brand or a product.

136 K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142

additional ethical properties. Organic products with additional eth-

ical characteristics were offered at a 20% higher price in compari-

son with the ‘standard’ organic product. By clicking the

corresponding field,the respondents could uncover the informa-

tion they needed in order to come to a virtual purchase decision

for one of the products.Participants were recruited at random in

front of retail shops that offered a relatively high share of organic

food. In the five study countries,nearly 1200 regular and occa-

sional consumers of organic foods,including milk,participated in

the IDM and completed the accompanying questionnaire (Zander

& Hamm,2010).

Focus Groups

In the next step, the three most important additionalethical

attributes according to the results of the IDM were tested in each

country,using Focus Groups (FG).The aim of this research step

was twofold: First, to elicit consumers’ responses to different ways

of communicating these attributes in order to learn how to com-

municate these attributes in the subsequent step of Choice Exper-

iments in a promising manner, and second, to compare the ranking

of the attributes with the earlier research step.

FG are loosely-structured interactive discussions among a small

group of respondents (6–12), accompanied by a trained facilitator.

The strength of this technique lies in discovering the unexpected,

which may result from a free-flowing group discussion.FG were

held in the form of a consumer jury,following an adaptation of

the elaboration likelihood modelby Petty and Cacioppo (1986),

and they were combined with an individual ‘paper and pencil’ rat-

ing of communication proposals (Naspetti& Zanoli, 2011). The

analysis of the data was purely text-based.3

It was decided to use organic eggs as the test product, since or-

ganic eggs have a relatively high consumption share among con-

sumers in all study countries and are easily comparable between

countries.4 In order to be as close to reality as possible,package la-

bels were developed. For each of the three attributes a symbolic, gra-

phic artwork was designed. Additionally, for each attribute two

different labels were designed with different wordings of head-

lines/slogans and different body copy wordings,resulting in six dif-

ferent labels for egg packages (Naspetti & Zanoli,2011).Given the

fact that the most relevant ethical attributes were the same in all five

study countries (see Section ‘‘Relevance of different ethical attributes

on purchase decisions: IDM’’), identical labels were used to allow for

a cross-culturalcomparison of consumers’attitudes.The design of

the labels was intended to touch consumers at the emotional level

and, therefore, it was based on various heart images,reflecting care,

love and respect.5 The heart image was included in the graphics and

also in the slogans or headings of the labels. The aim was to measure

the underlying perception and attitudinal response to each label and

to gain insights into how to communicate these arguments effec-

tively (Naspetti & Zanoli, 2011). In total, 15 FG with regular and

occasional organic consumers were conducted across the five coun-

tries. Recruitment of participants took place at random in front of

food stores with a high share of organic food. Guidelines, with differ-

ent sections and key questions,were developed to structure the

group discussions and thus to obtain comparable exchange of infor-

mation in all countries.Similarly, guidelines were used to analyse

the original data and to elaborate country reports on the results of

Fig. 2. Information Display Matrix screen,showing information for one combination of product and attribute.Source: Own presentation.

3 For other methodologicaltools which integrate group interactions in a more

explicit way,see Halkier (2010).

4 The change from milk to eggs as test product became necessary due to the

outcome of the IDM research.The additional ethical attributes identified for further

research (e.g. local production, fair prices for farmers) turned out to be difficult to test

in any depth with milk; particularly in Italy,where high shares of organic milk are

imported and offered mainly as UHT, and not as fresh milk as is the case in the other

study countries.

5 According to Solomon et al.(2010: 37) ‘love’is one of the possible relationships

consumers can have with a brand or a product.

136 K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

the FG, which were then merged to one single report on the outcome

of the FG. This approach was preferred over an analysis of the trans-

lated raw material from each country by a single researcher, so as to

avoid the risk of basic misunderstandings and loss of detail in the fi-

nal results (Janssen & Hamm,2011).

Choice Experiments

Finally,Choice Experiments (CE) were conducted.CE are used

to reveal stated preferences and the willingness to pay of consum-

ers. For this purpose,test persons are usually presented with dif-

ferent product options,which have different characteristics,and

they must choose one of these products. Usually,each test person

repeats the purchase decision a number of times.

For the CE, organic eggs were again used as test product.

According to the results of the FG, however, the egg package labels

were redesigned in order to better address consumer concerns and

to be better accepted.Specific communication arguments were

developed for each attribute and used in this research step.The

new labels contained only short and concise arguments,while

the images had been removed.Three price levels were included

in the choice sets. Price level 1 corresponded to the average organic

egg price in the country concerned. Price levels 2 and 3 amounted

to 120% and 140% of price level 1,respectively.Additional ethical

arguments were tested individually or in different combinations,

with varying price levels 1–3,on two organic egg alternatives in

each choice set. Additionally, a reference product alternative (with-

out any ethical argument)was offered at price level 1 in each

choice set,as well as a ‘no choice’option. This no choice option

was included in order to prevent bias caused by ‘forced choice’

(Dhar & Simonson,2003) and to create a buying situation closer

to reality. A fractional factorial d-efficient design using the soft-

ware NGene was created.An unlabelled design was chosen and

18 choice sets were constructed. Each choice set consisted of three

alternatives and the choice sets were split into three blocks.Thus,

each respondent made six consecutive choices,and one of the six

choices was randomly chosen as a binding purchase decision in or-

der to increase the reliability of the results, following the approach

of Lusk and Schroeder (2004).Consumers obtained an incentive

which they could spend on eggs in the choice experiment.

For the experiments in each study country,at least 80 organic

consumers (regular and occasional)6 were recruited via telephone

by market research institutions. In total 400 consumers participated

in laboratory experiments. Quota sampling was used with respect to

age,gender and employment.

Data obtained through the Choice Experiments were analysed

using random parameter logit models (RPL) (Revelt & Train,

1998) and,for each country,a separate modelwas estimated.In

RPL models,the choice probability in a choice set t is conditional

over the vector of taste parameters bnt of K elements that can be

random.Furthermore,the choice probability is conditional on the

individual-specific error componentseni. The conditional probabil-

ity that a consumer n chooses a specific alternative i from a choice

set J in choice t of a sequence of choices T is:

Pðint bnj ;enÞ ¼ eXintbnþ1ðejnÞ

P J

j¼1eXjntbnþ1ðejnÞ

By the exponential function e, a constant change in the independent

variable gives the same proportional change in the dependent var-

iable (here,choice).Xint represents a vector of variables explaining

choice and bn is a vector of parameters to be estimated.Finally ejn

is the error component as described above and 1(. . .) serves as an

indicator function for the experimentally-designed alternatives

involving choice in each choice set, serving as additional error com-

ponent meant to capture the cognitive effort of evaluating a hypo-

thetical purchase. Other than basic multinomial logit models (MNL),

RPL models account for heterogeneous preferences – which are

likely to occur in the case of additional ethical attributes of organic

food – and do not rely on the IIA assumption (‘independence of

irrelevant alternatives’)(Hahn, 1997; Hensher, Rose, & Greene,

2005; Teratanavat & Hooker,2006).

Consumers’preferences for additional ethical attributes of

organic food

This section focuses on presenting the results of different steps

of the consumer research: the Information Display Matrix,Focus

Groups and the Choice Experiments.

Relevance of different ethical attributes on purchase decisions: IDM

Based on the inventory of organic farms and expertdiscus-

sion, the attributes ‘animal welfare’,‘regional/localproduction’,

‘care farming’,‘social criteria of production’,‘biodiversity’,‘cul-

tural features of production’and ‘fair prices for farmers’were se-

lected for the first step of consumer research.An Information

Display Matrix (IDM) was used in order to extract,from the ori-

ginal seven selected,the three additional ethical attributes re-

garded as most relevant for consumers’purchase decisions.The

indicator used to derive consumers’ preferences for additional

ethical attributes was the relative share of each attribute in first

requests for information.According to this indicator,information

on ‘animal welfare’and ‘localproduction’were the most impor-

tant additional ethical attributes on average,followed by ‘fair

prices for farmers’in almost all countries.For Italian consumers,

‘local production’ appeared to be more importantthan ‘animal

welfare’, and the ‘fair prices for farmers’ argument was less

important than product price.Swiss participants had a high rel-

ative preference for ‘animalwelfare’and ‘local production’com-

pared to other attributes,and ‘product price’was less important

than in other countries (Table 1).There were no differences be-

tween regular and occasionalconsumers of organic food regard-

ing the ordering of the additional ethicalattributes.Significantly

however,occasionalconsumers accessed the product price more

frequently first (15.6%) than regular consumers (9.5%) (Chi2

-Test

for Independence).

Another indicator used to reveal consumers’ preference was the

share of respondents looking for information about a particular

attribute at least once.The ranking of attributes according to this

indicator was similar to the results presented in Table 1.Interest-

ingly, on average, only 80% of all respondents considered the attri-

bute ‘product price’ at least once before making their virtual

purchase decision.In other words, 19.7% of test persons did not

ask for any information at all on product prices before opting for

the product.This proportion was significantly higher among con-

sumers who regularly buy organic food (25.3%) in comparison with

those who buy organic food only occasionally (17.4%) (Chi2

-Test for

Independence). Similar results regarding relatively low price sensi-

tivity among regular organic consumers were found by Plassmann

and Hamm (2011).

Communication of selected ethical attributes: FG

Based on these results,and in order to understand both the

perception and acceptance ofdifferent ways of communicating

these additional ethical concerns in each study country, the

6 In order to exclude those consumers who were unfamiliar with the concept of

organic food, potential test persons had to correctly answer the question ‘‘How do you

identify organic products?’’.

K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142 137

of the FG. This approach was preferred over an analysis of the trans-

lated raw material from each country by a single researcher, so as to

avoid the risk of basic misunderstandings and loss of detail in the fi-

nal results (Janssen & Hamm,2011).

Choice Experiments

Finally,Choice Experiments (CE) were conducted.CE are used

to reveal stated preferences and the willingness to pay of consum-

ers. For this purpose,test persons are usually presented with dif-

ferent product options,which have different characteristics,and

they must choose one of these products. Usually,each test person

repeats the purchase decision a number of times.

For the CE, organic eggs were again used as test product.

According to the results of the FG, however, the egg package labels

were redesigned in order to better address consumer concerns and

to be better accepted.Specific communication arguments were

developed for each attribute and used in this research step.The

new labels contained only short and concise arguments,while

the images had been removed.Three price levels were included

in the choice sets. Price level 1 corresponded to the average organic

egg price in the country concerned. Price levels 2 and 3 amounted

to 120% and 140% of price level 1,respectively.Additional ethical

arguments were tested individually or in different combinations,

with varying price levels 1–3,on two organic egg alternatives in

each choice set. Additionally, a reference product alternative (with-

out any ethical argument)was offered at price level 1 in each

choice set,as well as a ‘no choice’option. This no choice option

was included in order to prevent bias caused by ‘forced choice’

(Dhar & Simonson,2003) and to create a buying situation closer

to reality. A fractional factorial d-efficient design using the soft-

ware NGene was created.An unlabelled design was chosen and

18 choice sets were constructed. Each choice set consisted of three

alternatives and the choice sets were split into three blocks.Thus,

each respondent made six consecutive choices,and one of the six

choices was randomly chosen as a binding purchase decision in or-

der to increase the reliability of the results, following the approach

of Lusk and Schroeder (2004).Consumers obtained an incentive

which they could spend on eggs in the choice experiment.

For the experiments in each study country,at least 80 organic

consumers (regular and occasional)6 were recruited via telephone

by market research institutions. In total 400 consumers participated

in laboratory experiments. Quota sampling was used with respect to

age,gender and employment.

Data obtained through the Choice Experiments were analysed

using random parameter logit models (RPL) (Revelt & Train,

1998) and,for each country,a separate modelwas estimated.In

RPL models,the choice probability in a choice set t is conditional

over the vector of taste parameters bnt of K elements that can be

random.Furthermore,the choice probability is conditional on the

individual-specific error componentseni. The conditional probabil-

ity that a consumer n chooses a specific alternative i from a choice

set J in choice t of a sequence of choices T is:

Pðint bnj ;enÞ ¼ eXintbnþ1ðejnÞ

P J

j¼1eXjntbnþ1ðejnÞ

By the exponential function e, a constant change in the independent

variable gives the same proportional change in the dependent var-

iable (here,choice).Xint represents a vector of variables explaining

choice and bn is a vector of parameters to be estimated.Finally ejn

is the error component as described above and 1(. . .) serves as an

indicator function for the experimentally-designed alternatives

involving choice in each choice set, serving as additional error com-

ponent meant to capture the cognitive effort of evaluating a hypo-

thetical purchase. Other than basic multinomial logit models (MNL),

RPL models account for heterogeneous preferences – which are

likely to occur in the case of additional ethical attributes of organic

food – and do not rely on the IIA assumption (‘independence of

irrelevant alternatives’)(Hahn, 1997; Hensher, Rose, & Greene,

2005; Teratanavat & Hooker,2006).

Consumers’preferences for additional ethical attributes of

organic food

This section focuses on presenting the results of different steps

of the consumer research: the Information Display Matrix,Focus

Groups and the Choice Experiments.

Relevance of different ethical attributes on purchase decisions: IDM

Based on the inventory of organic farms and expertdiscus-

sion, the attributes ‘animal welfare’,‘regional/localproduction’,

‘care farming’,‘social criteria of production’,‘biodiversity’,‘cul-

tural features of production’and ‘fair prices for farmers’were se-

lected for the first step of consumer research.An Information

Display Matrix (IDM) was used in order to extract,from the ori-

ginal seven selected,the three additional ethical attributes re-

garded as most relevant for consumers’purchase decisions.The

indicator used to derive consumers’ preferences for additional

ethical attributes was the relative share of each attribute in first

requests for information.According to this indicator,information

on ‘animal welfare’and ‘localproduction’were the most impor-

tant additional ethical attributes on average,followed by ‘fair

prices for farmers’in almost all countries.For Italian consumers,

‘local production’ appeared to be more importantthan ‘animal

welfare’, and the ‘fair prices for farmers’ argument was less

important than product price.Swiss participants had a high rel-

ative preference for ‘animalwelfare’and ‘local production’com-

pared to other attributes,and ‘product price’was less important

than in other countries (Table 1).There were no differences be-

tween regular and occasionalconsumers of organic food regard-

ing the ordering of the additional ethicalattributes.Significantly

however,occasionalconsumers accessed the product price more

frequently first (15.6%) than regular consumers (9.5%) (Chi2

-Test

for Independence).

Another indicator used to reveal consumers’ preference was the

share of respondents looking for information about a particular

attribute at least once.The ranking of attributes according to this

indicator was similar to the results presented in Table 1.Interest-

ingly, on average, only 80% of all respondents considered the attri-

bute ‘product price’ at least once before making their virtual

purchase decision.In other words, 19.7% of test persons did not

ask for any information at all on product prices before opting for

the product.This proportion was significantly higher among con-

sumers who regularly buy organic food (25.3%) in comparison with

those who buy organic food only occasionally (17.4%) (Chi2

-Test for

Independence). Similar results regarding relatively low price sensi-

tivity among regular organic consumers were found by Plassmann

and Hamm (2011).

Communication of selected ethical attributes: FG

Based on these results,and in order to understand both the

perception and acceptance ofdifferent ways of communicating

these additional ethical concerns in each study country, the

6 In order to exclude those consumers who were unfamiliar with the concept of

organic food, potential test persons had to correctly answer the question ‘‘How do you

identify organic products?’’.

K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142 137

three most important additional ethical attributes ‘animal

welfare’,‘local production’ and ‘fair prices for farmers’ were

discussed in the Focus Groups (FG) with consumers of organic

food. Discussions were based on the six different egg labels that

had been designed (see Section ‘‘Methodologicalapproach’’and

Table 2).

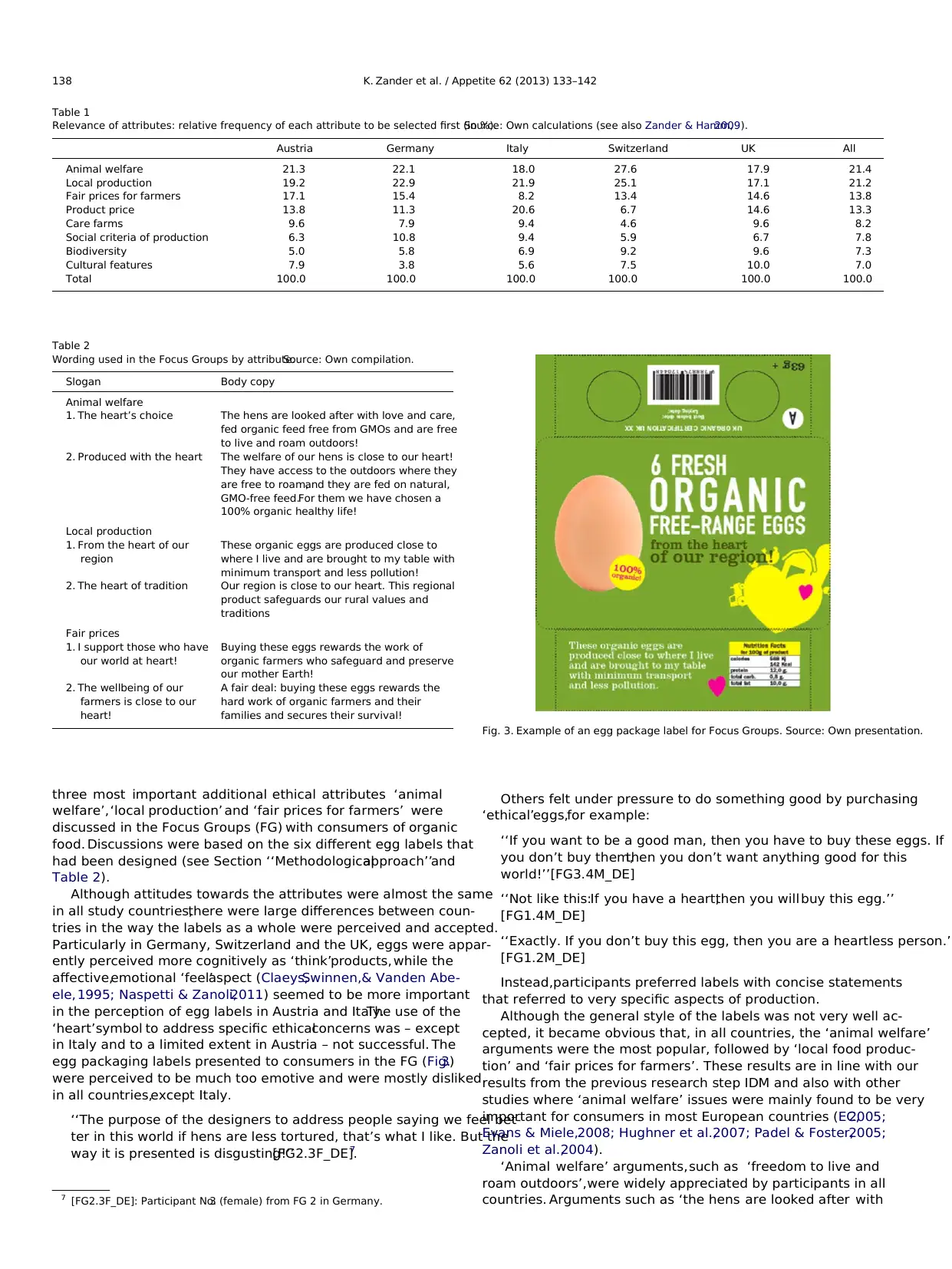

Although attitudes towards the attributes were almost the same

in all study countries,there were large differences between coun-

tries in the way the labels as a whole were perceived and accepted.

Particularly in Germany, Switzerland and the UK, eggs were appar-

ently perceived more cognitively as ‘think’products, while the

affective,emotional ‘feel’aspect (Claeys,Swinnen,& Vanden Abe-

ele,1995; Naspetti & Zanoli,2011) seemed to be more important

in the perception of egg labels in Austria and Italy.The use of the

‘heart’symbol to address specific ethicalconcerns was – except

in Italy and to a limited extent in Austria – not successful. The

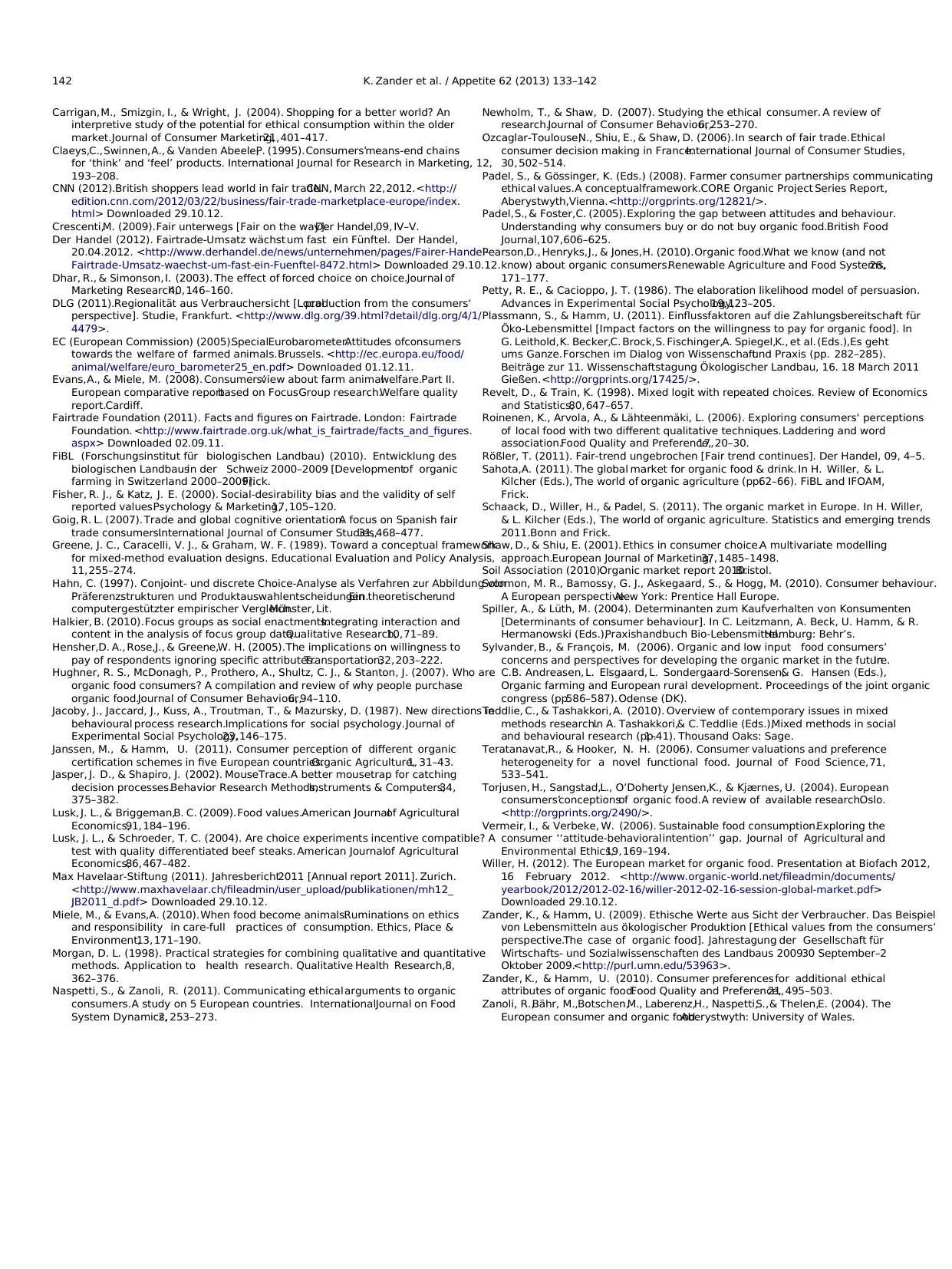

egg packaging labels presented to consumers in the FG (Fig.3)

were perceived to be much too emotive and were mostly disliked

in all countries,except Italy.

‘‘The purpose of the designers to address people saying we feel bet-

ter in this world if hens are less tortured, that’s what I like. But the

way it is presented is disgusting!’’[FG2.3F_DE].7

Others felt under pressure to do something good by purchasing

‘ethical’eggs,for example:

‘‘If you want to be a good man, then you have to buy these eggs. If

you don’t buy them,then you don’t want anything good for this

world!’’[FG3.4M_DE]

‘‘Not like this:If you have a heart,then you will buy this egg.’’

[FG1.4M_DE]

‘‘Exactly. If you don’t buy this egg, then you are a heartless person.’’

[FG1.2M_DE]

Instead,participants preferred labels with concise statements

that referred to very specific aspects of production.

Although the general style of the labels was not very well ac-

cepted, it became obvious that, in all countries, the ‘animal welfare’

arguments were the most popular, followed by ‘local food produc-

tion’ and ‘fair prices for farmers’. These results are in line with our

results from the previous research step IDM and also with other

studies where ‘animal welfare’ issues were mainly found to be very

important for consumers in most European countries (EC,2005;

Evans & Miele,2008; Hughner et al.,2007; Padel & Foster,2005;

Zanoli et al.,2004).

‘Animal welfare’ arguments,such as ‘freedom to live and

roam outdoors’,were widely appreciated by participants in all

countries. Arguments such as ‘the hens are looked after with

Table 1

Relevance of attributes: relative frequency of each attribute to be selected first (in %).Source: Own calculations (see also Zander & Hamm,2009).

Austria Germany Italy Switzerland UK All

Animal welfare 21.3 22.1 18.0 27.6 17.9 21.4

Local production 19.2 22.9 21.9 25.1 17.1 21.2

Fair prices for farmers 17.1 15.4 8.2 13.4 14.6 13.8

Product price 13.8 11.3 20.6 6.7 14.6 13.3

Care farms 9.6 7.9 9.4 4.6 9.6 8.2

Social criteria of production 6.3 10.8 9.4 5.9 6.7 7.8

Biodiversity 5.0 5.8 6.9 9.2 9.6 7.3

Cultural features 7.9 3.8 5.6 7.5 10.0 7.0

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Table 2

Wording used in the Focus Groups by attribute.Source: Own compilation.

Slogan Body copy

Animal welfare

1. The heart’s choice The hens are looked after with love and care,

fed organic feed free from GMOs and are free

to live and roam outdoors!

2. Produced with the heart The welfare of our hens is close to our heart!

They have access to the outdoors where they

are free to roam,and they are fed on natural,

GMO-free feed.For them we have chosen a

100% organic healthy life!

Local production

1. From the heart of our

region

These organic eggs are produced close to

where I live and are brought to my table with

minimum transport and less pollution!

2. The heart of tradition Our region is close to our heart. This regional

product safeguards our rural values and

traditions

Fair prices

1. I support those who have

our world at heart!

Buying these eggs rewards the work of

organic farmers who safeguard and preserve

our mother Earth!

2. The wellbeing of our

farmers is close to our

heart!

A fair deal: buying these eggs rewards the

hard work of organic farmers and their

families and secures their survival!

Fig. 3. Example of an egg package label for Focus Groups. Source: Own presentation.

7 [FG2.3F_DE]: Participant No.3 (female) from FG 2 in Germany.

138 K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142

welfare’,‘local production’ and ‘fair prices for farmers’ were

discussed in the Focus Groups (FG) with consumers of organic

food. Discussions were based on the six different egg labels that

had been designed (see Section ‘‘Methodologicalapproach’’and

Table 2).

Although attitudes towards the attributes were almost the same

in all study countries,there were large differences between coun-

tries in the way the labels as a whole were perceived and accepted.

Particularly in Germany, Switzerland and the UK, eggs were appar-

ently perceived more cognitively as ‘think’products, while the

affective,emotional ‘feel’aspect (Claeys,Swinnen,& Vanden Abe-

ele,1995; Naspetti & Zanoli,2011) seemed to be more important

in the perception of egg labels in Austria and Italy.The use of the

‘heart’symbol to address specific ethicalconcerns was – except

in Italy and to a limited extent in Austria – not successful. The

egg packaging labels presented to consumers in the FG (Fig.3)

were perceived to be much too emotive and were mostly disliked

in all countries,except Italy.

‘‘The purpose of the designers to address people saying we feel bet-

ter in this world if hens are less tortured, that’s what I like. But the

way it is presented is disgusting!’’[FG2.3F_DE].7

Others felt under pressure to do something good by purchasing

‘ethical’eggs,for example:

‘‘If you want to be a good man, then you have to buy these eggs. If

you don’t buy them,then you don’t want anything good for this

world!’’[FG3.4M_DE]

‘‘Not like this:If you have a heart,then you will buy this egg.’’

[FG1.4M_DE]

‘‘Exactly. If you don’t buy this egg, then you are a heartless person.’’

[FG1.2M_DE]

Instead,participants preferred labels with concise statements

that referred to very specific aspects of production.

Although the general style of the labels was not very well ac-

cepted, it became obvious that, in all countries, the ‘animal welfare’

arguments were the most popular, followed by ‘local food produc-

tion’ and ‘fair prices for farmers’. These results are in line with our

results from the previous research step IDM and also with other

studies where ‘animal welfare’ issues were mainly found to be very

important for consumers in most European countries (EC,2005;

Evans & Miele,2008; Hughner et al.,2007; Padel & Foster,2005;

Zanoli et al.,2004).

‘Animal welfare’ arguments,such as ‘freedom to live and

roam outdoors’,were widely appreciated by participants in all

countries. Arguments such as ‘the hens are looked after with

Table 1

Relevance of attributes: relative frequency of each attribute to be selected first (in %).Source: Own calculations (see also Zander & Hamm,2009).

Austria Germany Italy Switzerland UK All

Animal welfare 21.3 22.1 18.0 27.6 17.9 21.4

Local production 19.2 22.9 21.9 25.1 17.1 21.2

Fair prices for farmers 17.1 15.4 8.2 13.4 14.6 13.8

Product price 13.8 11.3 20.6 6.7 14.6 13.3

Care farms 9.6 7.9 9.4 4.6 9.6 8.2

Social criteria of production 6.3 10.8 9.4 5.9 6.7 7.8

Biodiversity 5.0 5.8 6.9 9.2 9.6 7.3

Cultural features 7.9 3.8 5.6 7.5 10.0 7.0

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Table 2

Wording used in the Focus Groups by attribute.Source: Own compilation.

Slogan Body copy

Animal welfare

1. The heart’s choice The hens are looked after with love and care,

fed organic feed free from GMOs and are free

to live and roam outdoors!

2. Produced with the heart The welfare of our hens is close to our heart!

They have access to the outdoors where they

are free to roam,and they are fed on natural,

GMO-free feed.For them we have chosen a

100% organic healthy life!

Local production

1. From the heart of our

region

These organic eggs are produced close to

where I live and are brought to my table with

minimum transport and less pollution!

2. The heart of tradition Our region is close to our heart. This regional

product safeguards our rural values and

traditions

Fair prices

1. I support those who have

our world at heart!

Buying these eggs rewards the work of

organic farmers who safeguard and preserve

our mother Earth!

2. The wellbeing of our

farmers is close to our

heart!

A fair deal: buying these eggs rewards the

hard work of organic farmers and their

families and secures their survival!

Fig. 3. Example of an egg package label for Focus Groups. Source: Own presentation.

7 [FG2.3F_DE]: Participant No.3 (female) from FG 2 in Germany.

138 K. Zander et al. / Appetite 62 (2013) 133–142

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

love and care’ were only liked by some participants. However,

consumer perception of such statements also dependson the

type of animal, and some participants mentioned that similar

arguments for milk would be more acceptable in the case of

cows. In particular, German and Swiss participants preferred

product statements that were much more to the point and less

emotive.

With regard to ‘local production’ attributes, consumers fa-

voured detailed information such as place of production, and

even about the producer or farmer him/herself. The discus-

sions revealed that local products were preferred over regio-

nal, while regional products were preferred over national. The

argument ‘minimum transport and less pollution’ was per-

ceived as a concise message which many participants

appreciated.

‘‘Why can’t it just say produced locally instead of putting from the

heart of our region? Get rid of the heart!’’[FG3.5F_UK9].

In the context of organic egg production,the ‘fair prices for

farmers’argument turned out to be very difficult to communi-

cate. The argument for supporting farmers did not work well

because of its proximity to the international Fairtrade concept.

Most consumers felt that the situation for European farmers

was not comparable with that of poor farmers in developing

countries.

‘‘We are not talking about sport shoes sewn by kids. Instead we are

talking about eggs produced in Germany.’’[FG1.2F_DE].

‘‘They sell their eggs anyway so why should they be rewarded fur-

ther?’’[FG1.1M_UK].

‘‘As if it is our fault that farmers don’t survive’’or ‘‘this is just too

much.’’[FG1.3M_AT].

‘‘I have to say that on this one that I’m not too worried about the

well-being of the farmer.I’m more concerned about the chick that

laid the egg.’’[FG3.4M_UK].

It was clear from their discussions that participants did not

understand why domestic poultry farmers should receive any spe-

cial support. They also entered into the wider debate on the mean-

ing of ‘fair prices’/‘fair to whom?’,as well as aspects of fairness in

agricultural production more generally. Thus,‘fair prices for farm-

ers’ emerged as a complex attribute that will need particular atten-

tion as regards ‘‘finding the right words’’.Furthermore,consumer

reactions to this attribute may also depend on the product: while

the consumers’response in the context of egg production was

rather negative,there are several successful examples of the ‘fair

prices for farmers’argument being used by dairy farmers in Ger-

many and in Austria.

Consumers preferences for selected ethical attributes: CE

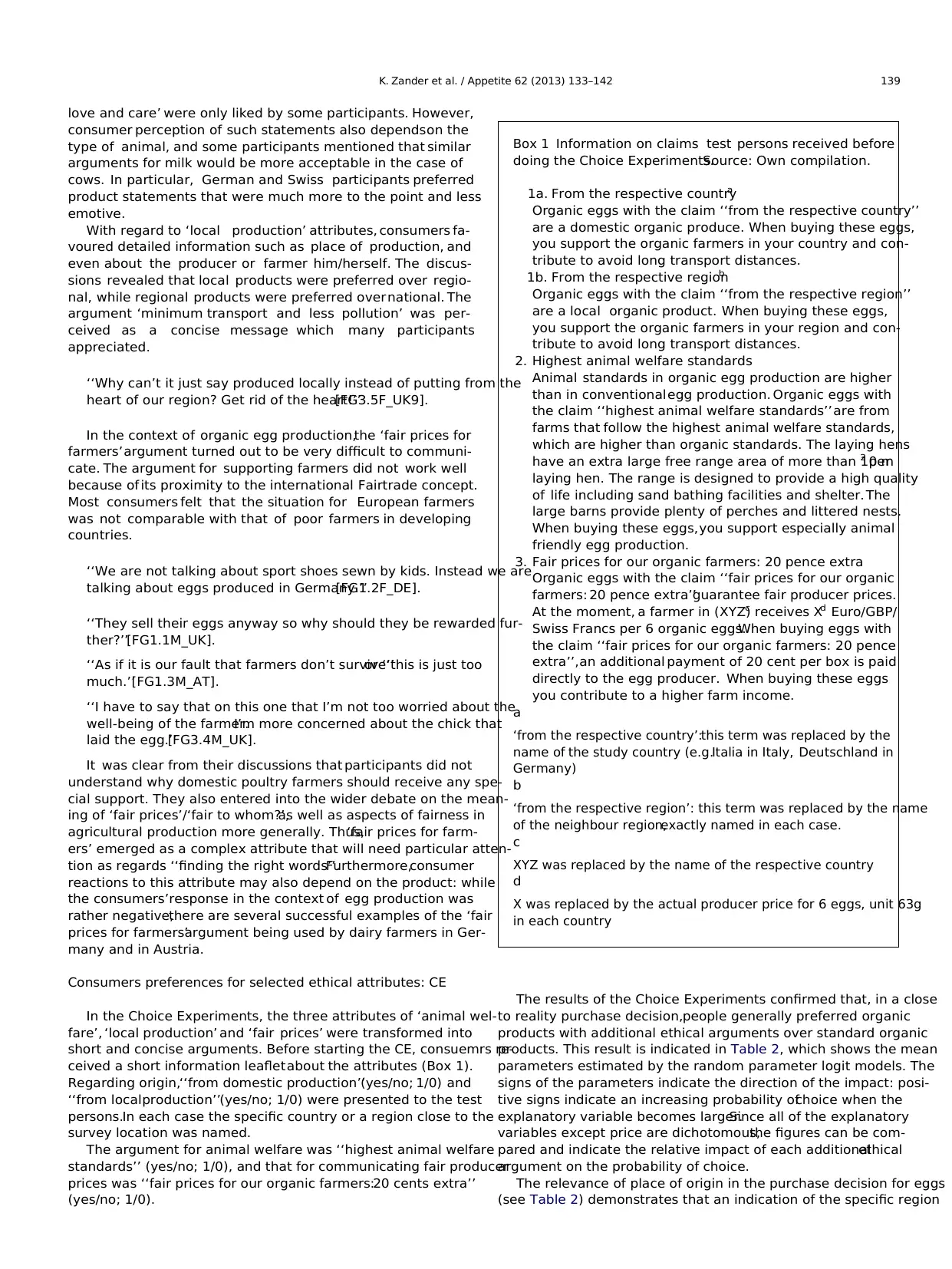

In the Choice Experiments, the three attributes of ‘animal wel-

fare’, ‘local production’ and ‘fair prices’ were transformed into

short and concise arguments. Before starting the CE, consuemrs re-

ceived a short information leafletabout the attributes (Box 1).

Regarding origin,‘‘from domestic production’’(yes/no; 1/0) and

‘‘from localproduction’’(yes/no; 1/0) were presented to the test

persons.In each case the specific country or a region close to the

survey location was named.

The argument for animal welfare was ‘‘highest animal welfare

standards’’ (yes/no; 1/0), and that for communicating fair producer