Ethical Theories: An Introduction for IT Professionals

VerifiedAdded on 2019/10/18

|10

|4222

|180

Essay

AI Summary

This essay provides a comprehensive introduction to ethical theories, crucial for understanding the ethical challenges in information technology. It begins by exploring the fundamental question of why ethics and morality matter, emphasizing the role of ethical systems, values, and beliefs in decision-making. The essay then defines ethics, highlighting its societal dimension and the specific ethical issues arising from IT's evolution. It discusses the importance of ethical thought and theories as tools for decision-making, referencing insights from business ethics. The core of the essay introduces two main categories of normative ethical theories: teleology and deontology. Teleological theories, focusing on consequences, are examined through utilitarianism, ethical egoism, and the common good approach. Deontological theories, emphasizing duties and rights, are also discussed. The essay underscores the relevance of these theories in IT, where the ability to gather and disseminate data brings significant ethical responsibilities. It aims to equip readers with a basic understanding of ethical frameworks to navigate the complexities of IT-related ethical dilemmas.

Introduction to Ethical Theories

The concepts of ethics, character, right and wrong, and good and evil

have captivated humankind since we began to live in groups,

communicate, and pass judgment on each other. The morality of our

actions is based on motivation, group rules and norms, and the end

result. The difficult questions of ethics and information technology (IT)

may not have been considered by previous generations, but what is good,

evil, right, and wrong in human behavior certainly has been. With these

historical foundations and systematic analyses of present-day and future

IT challenges, we are equipped for both the varied ethical battles we will

face and the ethical successes we desire.

Although most of you will be called upon to practice applied ethics in

typical business situations, you'll find that the foundation for such

application is a basic understanding of fundamental ethical theories.

These ethical theories include the work of ancient philosophers such as

Plato and Aristotle. This module introduces the widely accepted core

ethical philosophies, which will serve to provide you with a basic

understanding of ethical thought. With this knowledge, you can begin to

relate these theoretical frameworks to practical ethical applications in

today's IT environment.

Let's start with a fundamental question: "Why be ethical and moral?" At

the most existential level, it may not matter. But we don't live our lives in

a vacuum—we live our lives with our friends, relatives, acquaintances, co-

workers, strangers, and fellow wanderers. To be ethical and moral allows

us to be counted upon by others and to be better than we would

otherwise be. This, in turn, engenders trust and allows us to have

productive relationships with other people and in society. Our ethical

system, supported by critical thinking skills, is what enables us to make

distinctions between what is good, bad, right, or wrong.

An individual's ethical system is based upon his or her personal values

and beliefs as they relate to what is important and is, therefore, highly

individualized. Values are things that are important to us. "Values can be

categorized into three areas: Moral (fairness, truth, justice, love,

happiness), Pragmatic (efficiency, thrift, health, variety, patience) and

Aesthetic (attractive, soft, cold, square)" (Navran, n.d.). Moral values

influence our ethical system. These values may or may not be supported

by individual beliefs. For example, a person is faced with a decision—he

borrowed a friend's car and accidentally backed into a tree stump,

denting the fender—should he confess or make up a story about how it

happened when the car was parked? If he had a personal value of

honesty, he would decide not to lie to his friend. Or, he could have a

strong belief that lying is wrong because it shows disrespect for another

person and, therefore, he would tell the truth. In either case, the ethical

The concepts of ethics, character, right and wrong, and good and evil

have captivated humankind since we began to live in groups,

communicate, and pass judgment on each other. The morality of our

actions is based on motivation, group rules and norms, and the end

result. The difficult questions of ethics and information technology (IT)

may not have been considered by previous generations, but what is good,

evil, right, and wrong in human behavior certainly has been. With these

historical foundations and systematic analyses of present-day and future

IT challenges, we are equipped for both the varied ethical battles we will

face and the ethical successes we desire.

Although most of you will be called upon to practice applied ethics in

typical business situations, you'll find that the foundation for such

application is a basic understanding of fundamental ethical theories.

These ethical theories include the work of ancient philosophers such as

Plato and Aristotle. This module introduces the widely accepted core

ethical philosophies, which will serve to provide you with a basic

understanding of ethical thought. With this knowledge, you can begin to

relate these theoretical frameworks to practical ethical applications in

today's IT environment.

Let's start with a fundamental question: "Why be ethical and moral?" At

the most existential level, it may not matter. But we don't live our lives in

a vacuum—we live our lives with our friends, relatives, acquaintances, co-

workers, strangers, and fellow wanderers. To be ethical and moral allows

us to be counted upon by others and to be better than we would

otherwise be. This, in turn, engenders trust and allows us to have

productive relationships with other people and in society. Our ethical

system, supported by critical thinking skills, is what enables us to make

distinctions between what is good, bad, right, or wrong.

An individual's ethical system is based upon his or her personal values

and beliefs as they relate to what is important and is, therefore, highly

individualized. Values are things that are important to us. "Values can be

categorized into three areas: Moral (fairness, truth, justice, love,

happiness), Pragmatic (efficiency, thrift, health, variety, patience) and

Aesthetic (attractive, soft, cold, square)" (Navran, n.d.). Moral values

influence our ethical system. These values may or may not be supported

by individual beliefs. For example, a person is faced with a decision—he

borrowed a friend's car and accidentally backed into a tree stump,

denting the fender—should he confess or make up a story about how it

happened when the car was parked? If he had a personal value of

honesty, he would decide not to lie to his friend. Or, he could have a

strong belief that lying is wrong because it shows disrespect for another

person and, therefore, he would tell the truth. In either case, the ethical

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

decision making was influenced by his system of values or beliefs. These

may come from family, culture, experience, education, and so on.

This discussion brings us to the term ethics. Frank Navran, principal

consultant with the Ethics Resource Center (ERC), defines ethics as "the

study of what we understand to be good and right behavior and how

people make those judgments" (n.d.). Behavior that is consistent with

one's moral values would be considered ethical behavior. Actions that are

inconsistent with one's view of right, just, and good are considered

unethical behavior. However, it is important to note that determining

what is ethical is not just an individual decision—it also is determined

societally.

We will witness this larger social dimension in this course, which is

designed to provide you with an understanding of the specific ethical

issues that have arisen as information technology has evolved over the

last few decades. The very changes that enhanced technology causes in

society also create ethical issues and dilemmas not previously

encountered. The lack of precedent in many areas, combined with the

ease of potentially operating outside of ethical paradigms, pose

significant challenges to end users, IT analysts, programmers,

technicians, and managers of information systems. We must be prepared

logically and scientifically to understand ethics and to practice using

ethical guidelines in order to achieve good and right solutions and to plan

courses of action in times of change and uncertainty.

You can see from the benefits discussed above that knowledge, respect

for, and a deeper understanding of norms and laws and their source—

ethics and morals—is extremely useful. Ethical thought and theories are

tools to facilitate our ethical decision-making process. They can provide

the foundation on which to build a great company, or to become a better

and more productive employee, a better neighbor, and a better person.

Still, some professionals may wonder "Why study ethics?" Robert Hartley,

author of Business Ethics: Violations of the Public Trust (Hartley, 1993, pp.

322–324) closes his book with four insights, which speak directly to this

question for business and IT professionals. They are:

• The modern era is one of caveat vendidor, "Let the seller beware." For

IT managers, this is an important reason to understand and practice

ethics.

• In business (and in life), adversity is not forever. But Hartley points out

that when business problems are handled unethically, the adversity

becomes a permanent flaw and results in company, organization,

and individual failure.

• Trusting relationships (with customers, employees, and suppliers) are

critical keys to success. Ethical behavior is part and parcel of

building and maintaining the trust relationship, and hence business

success.

may come from family, culture, experience, education, and so on.

This discussion brings us to the term ethics. Frank Navran, principal

consultant with the Ethics Resource Center (ERC), defines ethics as "the

study of what we understand to be good and right behavior and how

people make those judgments" (n.d.). Behavior that is consistent with

one's moral values would be considered ethical behavior. Actions that are

inconsistent with one's view of right, just, and good are considered

unethical behavior. However, it is important to note that determining

what is ethical is not just an individual decision—it also is determined

societally.

We will witness this larger social dimension in this course, which is

designed to provide you with an understanding of the specific ethical

issues that have arisen as information technology has evolved over the

last few decades. The very changes that enhanced technology causes in

society also create ethical issues and dilemmas not previously

encountered. The lack of precedent in many areas, combined with the

ease of potentially operating outside of ethical paradigms, pose

significant challenges to end users, IT analysts, programmers,

technicians, and managers of information systems. We must be prepared

logically and scientifically to understand ethics and to practice using

ethical guidelines in order to achieve good and right solutions and to plan

courses of action in times of change and uncertainty.

You can see from the benefits discussed above that knowledge, respect

for, and a deeper understanding of norms and laws and their source—

ethics and morals—is extremely useful. Ethical thought and theories are

tools to facilitate our ethical decision-making process. They can provide

the foundation on which to build a great company, or to become a better

and more productive employee, a better neighbor, and a better person.

Still, some professionals may wonder "Why study ethics?" Robert Hartley,

author of Business Ethics: Violations of the Public Trust (Hartley, 1993, pp.

322–324) closes his book with four insights, which speak directly to this

question for business and IT professionals. They are:

• The modern era is one of caveat vendidor, "Let the seller beware." For

IT managers, this is an important reason to understand and practice

ethics.

• In business (and in life), adversity is not forever. But Hartley points out

that when business problems are handled unethically, the adversity

becomes a permanent flaw and results in company, organization,

and individual failure.

• Trusting relationships (with customers, employees, and suppliers) are

critical keys to success. Ethical behavior is part and parcel of

building and maintaining the trust relationship, and hence business

success.

• One person can make a difference. This difference may be for good or

evil, but one person equipped with the understanding of ethical

decision-making, either by acting on it or simply articulating it to

others, changes history. This sometimes takes courage or

steadfastness—qualities that spring from basic ethical confidence.

In the world of information technology today and in the future, the

application of these ethical theories to day-to-day and strategic decision

making is particularly relevant. The ability to garner personal, corporate,

and governmental information and to disseminate this data in thousands

of applications with various configurations and components brings

significant responsibilities to ensure the privacy, accuracy, and integrity

of such information. The drive to collect and distribute data at increasing

volume and speed, whether for competitive advantage in the marketplace

or homeland security cannot overshadow the IT manager's responsibility

to provide appropriate controls, processes, and procedures to protect

individual and organizational rights.

Let's begin building our understanding of several predominant ethical

theories. Ethical theories typically begin with the premise that what is

being evaluated is good or bad, right or wrong. Theorists seek to examine

either the basic nature of the act or the results the act brings about. As

Deborah Johnson (2001, p. 29) states in Computer Ethics, philosophical

ethics is normative (explaining how things should be, not how they are at

any given moment) and ethical theories are prescriptive (prescribing the

"desired" behavior). Frameworks for ethical analysis aim to shape or

guide the most beneficial outcome or behavior. There are two main

categories of normative ethical theories: teleology and deontology. Telos

refers to end and deon refers to that which is obligatory. These theories

address the fundamental question of whether the "means justify the end"

or the "end justifies the means." Deontological ethical systems focus on

the principle of the matter (the means), not the end result. In contrast,

teleological ethical systems address the resulting consequences of an

action (the ends).

Return to top of page

Teleology (Consequentialism)

Teleological theories focus on maximizing the goodness of the cumulative

end result of a decision or action. In determining action, one considers the

good of the end result before the immediate rightness of the action itself.

These theories focus on consequences of an action or decision and are

often referred to as consequentialism. Teleological theories include

utilitarianism, ethical egoism, and common good ethics.

Utilitarianism

The most prevalent example of a teleological theory is utilitarianism,

evil, but one person equipped with the understanding of ethical

decision-making, either by acting on it or simply articulating it to

others, changes history. This sometimes takes courage or

steadfastness—qualities that spring from basic ethical confidence.

In the world of information technology today and in the future, the

application of these ethical theories to day-to-day and strategic decision

making is particularly relevant. The ability to garner personal, corporate,

and governmental information and to disseminate this data in thousands

of applications with various configurations and components brings

significant responsibilities to ensure the privacy, accuracy, and integrity

of such information. The drive to collect and distribute data at increasing

volume and speed, whether for competitive advantage in the marketplace

or homeland security cannot overshadow the IT manager's responsibility

to provide appropriate controls, processes, and procedures to protect

individual and organizational rights.

Let's begin building our understanding of several predominant ethical

theories. Ethical theories typically begin with the premise that what is

being evaluated is good or bad, right or wrong. Theorists seek to examine

either the basic nature of the act or the results the act brings about. As

Deborah Johnson (2001, p. 29) states in Computer Ethics, philosophical

ethics is normative (explaining how things should be, not how they are at

any given moment) and ethical theories are prescriptive (prescribing the

"desired" behavior). Frameworks for ethical analysis aim to shape or

guide the most beneficial outcome or behavior. There are two main

categories of normative ethical theories: teleology and deontology. Telos

refers to end and deon refers to that which is obligatory. These theories

address the fundamental question of whether the "means justify the end"

or the "end justifies the means." Deontological ethical systems focus on

the principle of the matter (the means), not the end result. In contrast,

teleological ethical systems address the resulting consequences of an

action (the ends).

Return to top of page

Teleology (Consequentialism)

Teleological theories focus on maximizing the goodness of the cumulative

end result of a decision or action. In determining action, one considers the

good of the end result before the immediate rightness of the action itself.

These theories focus on consequences of an action or decision and are

often referred to as consequentialism. Teleological theories include

utilitarianism, ethical egoism, and common good ethics.

Utilitarianism

The most prevalent example of a teleological theory is utilitarianism,

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

often associated with the writings of John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham.

Utilitarianism looks for the greatest good for the greatest number of

people, including oneself. Individual rights and entitlements are

subservient to the general welfare. There are two main subtypes: act-

utilitarianism (for which the rules are more like rules-of-thumb/guidelines)

and rule-utilitarianism (for which the rules are more tightly defined and

critical). Utilitarianism requires consideration of actions that generate the

best overall consequences for all parties involved. This entails:

• cost/benefit analysis

• determination of the greatest good or happiness for the greatest

number

• identifying the action that will maximize benefits for the greatest

number of stakeholders of the organization

This quote explains a bit more: "The fathers of utilitarianism thought of it

principally as a system of social and political decision, as offering a

criterion and basis of judgment for legislators and administrators"

(Williams, 1993, p. 135). Utilitarianism is geared to administrative and

organizational decision-making, given that in complex systems or

relationships, a single individual may not have the resources to determine

the overall benefit to the total number of people affected by the

decisions.

Ethical Egoism and Altruism

Egoism is maximizing your own benefits and minimizing harm to yourself.

This is sometimes thought of as behavioral Darwinism, and clearly it

guides decision-making with an eye toward basic survival. Although

different aspects of this theory debate whether all human behavior is self-

serving or should be self-serving, it is impossible to know with certainty

what internally motivates an individual.

Altruism determines decisions and actions based on the interests of

others, the perceived maximized good for others, often at one's own

expense or in a way directly opposed to the egoist alternative.

Further debate can be found over whether ethical egoism also

incorporates an element of altruism. For example, a network engineer

working for a vendor recommends to a client a network security

installation that generates a substantial commission for the engineer.

However, this installation also provides maximum network security for the

benefit of the client. Is this self-serving or altruistic? The inability to

distinguish pure motives in most practical applications, along with the

inherent conflict resulting from competing self-interests, leads to an

unsurprising result: these theories are not typically used in generally

accepted frameworks for ethical decision-making.

The Common Good

The common-good approach comes from the teachings and writings of

Utilitarianism looks for the greatest good for the greatest number of

people, including oneself. Individual rights and entitlements are

subservient to the general welfare. There are two main subtypes: act-

utilitarianism (for which the rules are more like rules-of-thumb/guidelines)

and rule-utilitarianism (for which the rules are more tightly defined and

critical). Utilitarianism requires consideration of actions that generate the

best overall consequences for all parties involved. This entails:

• cost/benefit analysis

• determination of the greatest good or happiness for the greatest

number

• identifying the action that will maximize benefits for the greatest

number of stakeholders of the organization

This quote explains a bit more: "The fathers of utilitarianism thought of it

principally as a system of social and political decision, as offering a

criterion and basis of judgment for legislators and administrators"

(Williams, 1993, p. 135). Utilitarianism is geared to administrative and

organizational decision-making, given that in complex systems or

relationships, a single individual may not have the resources to determine

the overall benefit to the total number of people affected by the

decisions.

Ethical Egoism and Altruism

Egoism is maximizing your own benefits and minimizing harm to yourself.

This is sometimes thought of as behavioral Darwinism, and clearly it

guides decision-making with an eye toward basic survival. Although

different aspects of this theory debate whether all human behavior is self-

serving or should be self-serving, it is impossible to know with certainty

what internally motivates an individual.

Altruism determines decisions and actions based on the interests of

others, the perceived maximized good for others, often at one's own

expense or in a way directly opposed to the egoist alternative.

Further debate can be found over whether ethical egoism also

incorporates an element of altruism. For example, a network engineer

working for a vendor recommends to a client a network security

installation that generates a substantial commission for the engineer.

However, this installation also provides maximum network security for the

benefit of the client. Is this self-serving or altruistic? The inability to

distinguish pure motives in most practical applications, along with the

inherent conflict resulting from competing self-interests, leads to an

unsurprising result: these theories are not typically used in generally

accepted frameworks for ethical decision-making.

The Common Good

The common-good approach comes from the teachings and writings of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Rawls. It is based on an assumption that

within our society, certain general conditions are equally advantageous to

all and should therefore be maximized. These conditions include health

care, safety, peace, justice, and the environment. This is different from

utilitarianism in that utilitarianism strives for the maximum good for the

most (but not necessarily all) people. The common-good approach sets

aside only those conditions that apply to all.

All teleological theories focus on the end result: what's best for me,

what's best for you, or what's best for some or all of us. One important

factor in using teleological frameworks as a guide to action is that you

need to be able to understand accurately and project the end result for

the variety of affected groups. For egoism and altruism, this is perhaps

not difficult. For larger, more remote, and less-well-understood groups,

teleological theories can lead to acts that in turn become the bricks

paving the road of good intentions. However, in information technology,

where many people are affected either positively or negatively by the

acts of a few, teleological theories can be very helpful.

Return to top of page

Deontology (Rights and Duties)

Deontological theories focus on defining the right action independently of

and prior to considerations of the goodness or badness of the outcomes.

The prefix deon refers to duty or obligation—one acts because one is

bound by honor or training to act in the right manner, regardless of the

outcome. Deontological theories include those that focus on protection of

universal rights and execution of universal duties, as well as those that

protect less universal rights and more specific duties. These rights and

duties are usually learned and are often codified in some traditional way.

For example, theologism is a deontological theory based on the Ten

Commandments. Boy Scouts have a code that is intended as a guide to

the rights of others and personal duties. Deontology uses one's duty as

the guide to action, regardless of the end results.

Kant's Categorical Imperative

Deontological theories are most often associated with Immanuel Kant and

his categorical imperative. Kant's famous categorical imperative takes

two forms:

1 You ought never act in any way unless that way or act can be made into

a universal maxim (i.e., your act may be universalized for all

people), and

2 Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or that of

another, always as an end and never only as a means.

Kant's duty-based approach might directly conflict with teleological

approaches, for in a utilitarian solution, individuals could very easily serve

within our society, certain general conditions are equally advantageous to

all and should therefore be maximized. These conditions include health

care, safety, peace, justice, and the environment. This is different from

utilitarianism in that utilitarianism strives for the maximum good for the

most (but not necessarily all) people. The common-good approach sets

aside only those conditions that apply to all.

All teleological theories focus on the end result: what's best for me,

what's best for you, or what's best for some or all of us. One important

factor in using teleological frameworks as a guide to action is that you

need to be able to understand accurately and project the end result for

the variety of affected groups. For egoism and altruism, this is perhaps

not difficult. For larger, more remote, and less-well-understood groups,

teleological theories can lead to acts that in turn become the bricks

paving the road of good intentions. However, in information technology,

where many people are affected either positively or negatively by the

acts of a few, teleological theories can be very helpful.

Return to top of page

Deontology (Rights and Duties)

Deontological theories focus on defining the right action independently of

and prior to considerations of the goodness or badness of the outcomes.

The prefix deon refers to duty or obligation—one acts because one is

bound by honor or training to act in the right manner, regardless of the

outcome. Deontological theories include those that focus on protection of

universal rights and execution of universal duties, as well as those that

protect less universal rights and more specific duties. These rights and

duties are usually learned and are often codified in some traditional way.

For example, theologism is a deontological theory based on the Ten

Commandments. Boy Scouts have a code that is intended as a guide to

the rights of others and personal duties. Deontology uses one's duty as

the guide to action, regardless of the end results.

Kant's Categorical Imperative

Deontological theories are most often associated with Immanuel Kant and

his categorical imperative. Kant's famous categorical imperative takes

two forms:

1 You ought never act in any way unless that way or act can be made into

a universal maxim (i.e., your act may be universalized for all

people), and

2 Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or that of

another, always as an end and never only as a means.

Kant's duty-based approach might directly conflict with teleological

approaches, for in a utilitarian solution, individuals could very easily serve

as the means for other ends. Duty-based ethical analysis leads a manager

to consider the following questions:

1 What if everyone did what I'm about to do? What kind of world would

this be? Can I universalize the course of action I am considering?

2 Does this course of action violate any basic ethical duties?

3 Are there alternatives that better conform to these duties? If each

alternative seems to violate one duty or another, which is the

stronger duty?

Duty-Based Ethics (Pluralism)

A duty-based approach to ethics focuses on the universally recognized

duties that we are morally compelled to do. There are several "duties"

that are recognized by most cultures as being binding and self-evident.

These duties include being honest, being fair, making reparations,

working toward self-improvement, and not hurting others. A duty-based

approach would put these obligations ahead of the end result, regardless

of what it may be. Pluralism includes the care-based ethical approach

based simply on the Golden Rule, "Do unto others as you would have

them do unto you."

Rights-Based Ethics (Contractarianism)

A rights-based approach to ethics has its roots in the social contract

philosophies of Rousseau, Hobbes, and John Locke. These ideas are also

at the foundation of the United States form of government and history,

and rights (whether natural or granted by governments) are intensely

held American ideological values. Because the global information

technology leadership is fundamentally an American creation,

contractarian philosophical approaches in IT are widely used, even if we

don't think about it overtly. When invoking a rights-based or contractarian

framework, managers must carefully consider the rights of affected

parties:

• Which action or policy best upholds the human rights of the individuals

involved?

• Do any alternatives under consideration violate their fundamental

human rights (i.e., liberty, privacy, and so on)?

• Do any alternatives under consideration violate their institutional or

legal rights (e.g., rights derived from a contract or other institutional

arrangement)?

Fairness and Justice

The fairness-and-justice approach is based on the teachings of Aristotle. It

is quite simple: equals should be treated equally. Favoritism, a situation

where some benefit for no justifiable reason, is unethical. Discrimination,

a situation where a burden is imposed on some who are not relevantly

different from the others, is also unethical. This approach is deontological

because it simply identifies a right and a duty, and does not specifically

to consider the following questions:

1 What if everyone did what I'm about to do? What kind of world would

this be? Can I universalize the course of action I am considering?

2 Does this course of action violate any basic ethical duties?

3 Are there alternatives that better conform to these duties? If each

alternative seems to violate one duty or another, which is the

stronger duty?

Duty-Based Ethics (Pluralism)

A duty-based approach to ethics focuses on the universally recognized

duties that we are morally compelled to do. There are several "duties"

that are recognized by most cultures as being binding and self-evident.

These duties include being honest, being fair, making reparations,

working toward self-improvement, and not hurting others. A duty-based

approach would put these obligations ahead of the end result, regardless

of what it may be. Pluralism includes the care-based ethical approach

based simply on the Golden Rule, "Do unto others as you would have

them do unto you."

Rights-Based Ethics (Contractarianism)

A rights-based approach to ethics has its roots in the social contract

philosophies of Rousseau, Hobbes, and John Locke. These ideas are also

at the foundation of the United States form of government and history,

and rights (whether natural or granted by governments) are intensely

held American ideological values. Because the global information

technology leadership is fundamentally an American creation,

contractarian philosophical approaches in IT are widely used, even if we

don't think about it overtly. When invoking a rights-based or contractarian

framework, managers must carefully consider the rights of affected

parties:

• Which action or policy best upholds the human rights of the individuals

involved?

• Do any alternatives under consideration violate their fundamental

human rights (i.e., liberty, privacy, and so on)?

• Do any alternatives under consideration violate their institutional or

legal rights (e.g., rights derived from a contract or other institutional

arrangement)?

Fairness and Justice

The fairness-and-justice approach is based on the teachings of Aristotle. It

is quite simple: equals should be treated equally. Favoritism, a situation

where some benefit for no justifiable reason, is unethical. Discrimination,

a situation where a burden is imposed on some who are not relevantly

different from the others, is also unethical. This approach is deontological

because it simply identifies a right and a duty, and does not specifically

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

consider the end result.

Virtue Ethics

Whereas teleological theories focus on results or consequences and

deontological theories relate to rights and duties, the virtue ethics

approach attributes ethics to personal attitudes or character traits and

encourages all to develop to their highest potential. This theory includes

the virtues themselves: "motives and moral character, moral education,

moral wisdom or discernment, friendship and family relationships, a deep

concept of happiness, the role of emotions in one's moral life and the

fundamentally important questions of what sort of person I should be and

how I should live my life" (Hursthouse, 2003). When faced with an ethical

dilemma, a virtue ethicist would focus on the character traits of honesty,

generosity, or compassion, for example, rather than consequences or

rules. Virtue ethics is included in the area of what is referred to as

normative ethics.

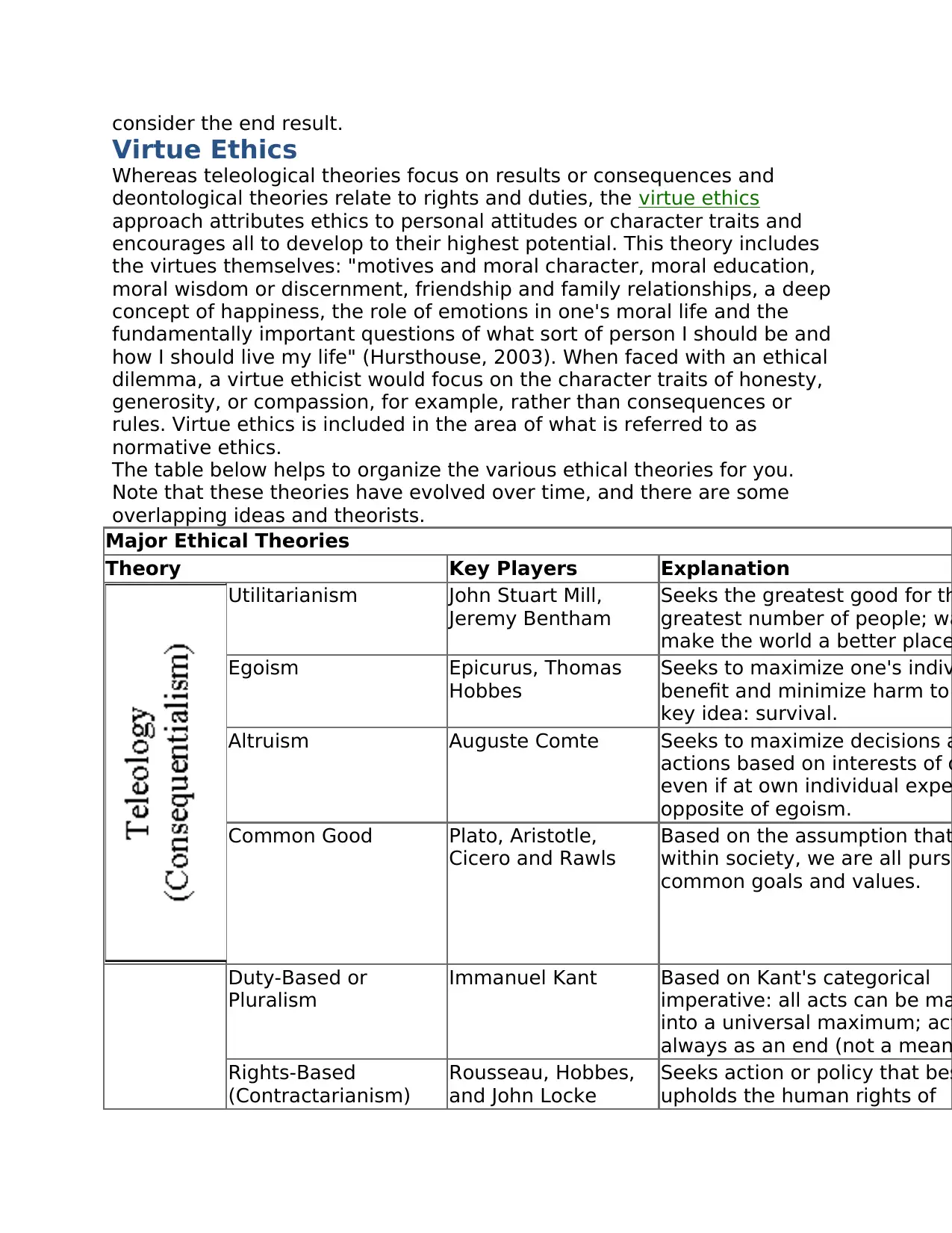

The table below helps to organize the various ethical theories for you.

Note that these theories have evolved over time, and there are some

overlapping ideas and theorists.

Major Ethical Theories

Theory Key Players Explanation

Utilitarianism John Stuart Mill,

Jeremy Bentham

Seeks the greatest good for th

greatest number of people; wa

make the world a better place

Egoism Epicurus, Thomas

Hobbes

Seeks to maximize one's indiv

benefit and minimize harm to

key idea: survival.

Altruism Auguste Comte Seeks to maximize decisions a

actions based on interests of o

even if at own individual expe

opposite of egoism.

Common Good Plato, Aristotle,

Cicero and Rawls

Based on the assumption that

within society, we are all pursu

common goals and values.

Duty-Based or

Pluralism

Immanuel Kant Based on Kant's categorical

imperative: all acts can be ma

into a universal maximum; act

always as an end (not a mean

Rights-Based

(Contractarianism)

Rousseau, Hobbes,

and John Locke

Seeks action or policy that bes

upholds the human rights of

Virtue Ethics

Whereas teleological theories focus on results or consequences and

deontological theories relate to rights and duties, the virtue ethics

approach attributes ethics to personal attitudes or character traits and

encourages all to develop to their highest potential. This theory includes

the virtues themselves: "motives and moral character, moral education,

moral wisdom or discernment, friendship and family relationships, a deep

concept of happiness, the role of emotions in one's moral life and the

fundamentally important questions of what sort of person I should be and

how I should live my life" (Hursthouse, 2003). When faced with an ethical

dilemma, a virtue ethicist would focus on the character traits of honesty,

generosity, or compassion, for example, rather than consequences or

rules. Virtue ethics is included in the area of what is referred to as

normative ethics.

The table below helps to organize the various ethical theories for you.

Note that these theories have evolved over time, and there are some

overlapping ideas and theorists.

Major Ethical Theories

Theory Key Players Explanation

Utilitarianism John Stuart Mill,

Jeremy Bentham

Seeks the greatest good for th

greatest number of people; wa

make the world a better place

Egoism Epicurus, Thomas

Hobbes

Seeks to maximize one's indiv

benefit and minimize harm to

key idea: survival.

Altruism Auguste Comte Seeks to maximize decisions a

actions based on interests of o

even if at own individual expe

opposite of egoism.

Common Good Plato, Aristotle,

Cicero and Rawls

Based on the assumption that

within society, we are all pursu

common goals and values.

Duty-Based or

Pluralism

Immanuel Kant Based on Kant's categorical

imperative: all acts can be ma

into a universal maximum; act

always as an end (not a mean

Rights-Based

(Contractarianism)

Rousseau, Hobbes,

and John Locke

Seeks action or policy that bes

upholds the human rights of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

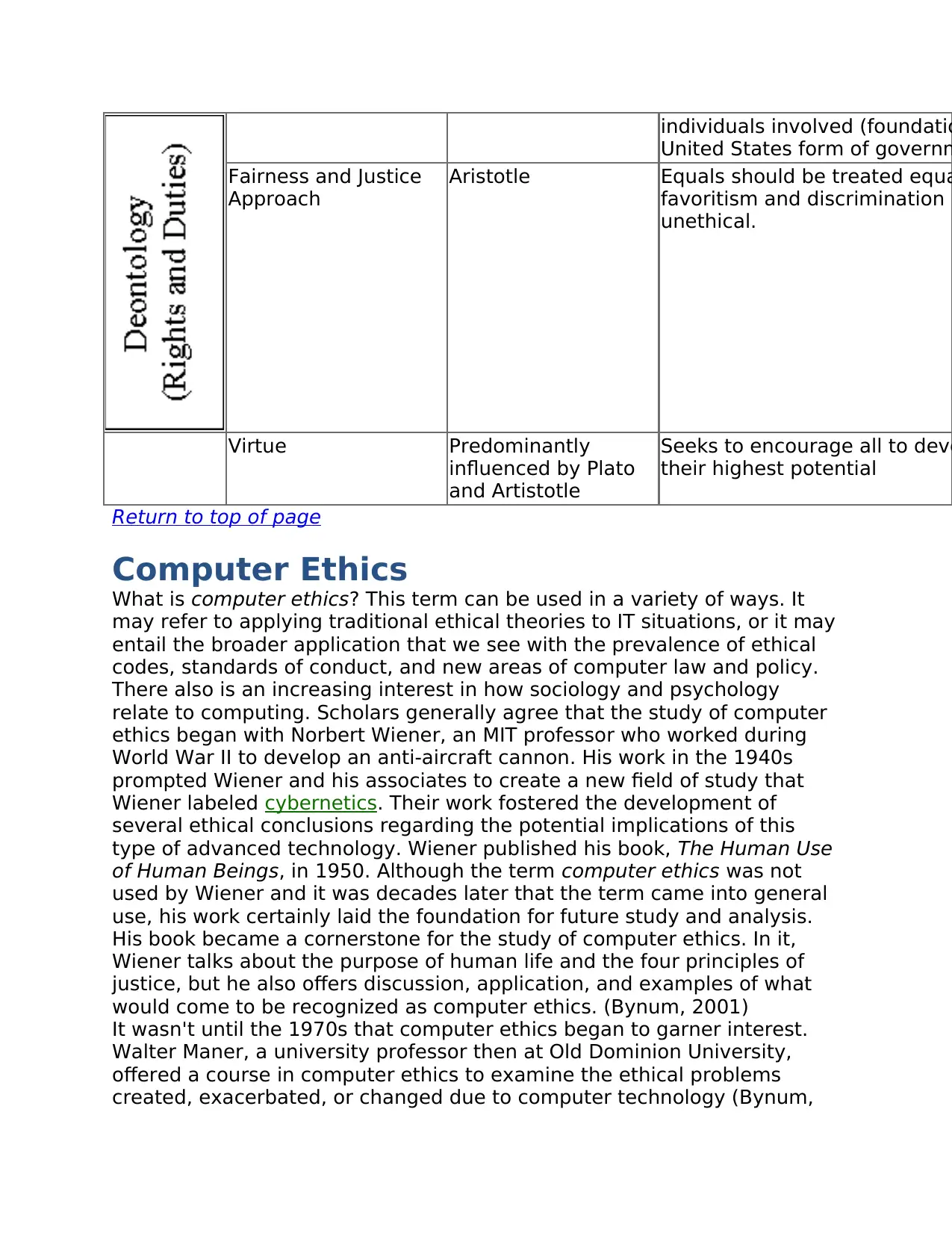

individuals involved (foundatio

United States form of governm

Fairness and Justice

Approach

Aristotle Equals should be treated equa

favoritism and discrimination a

unethical.

Virtue Predominantly

influenced by Plato

and Artistotle

Seeks to encourage all to deve

their highest potential

Return to top of page

Computer Ethics

What is computer ethics? This term can be used in a variety of ways. It

may refer to applying traditional ethical theories to IT situations, or it may

entail the broader application that we see with the prevalence of ethical

codes, standards of conduct, and new areas of computer law and policy.

There also is an increasing interest in how sociology and psychology

relate to computing. Scholars generally agree that the study of computer

ethics began with Norbert Wiener, an MIT professor who worked during

World War II to develop an anti-aircraft cannon. His work in the 1940s

prompted Wiener and his associates to create a new field of study that

Wiener labeled cybernetics. Their work fostered the development of

several ethical conclusions regarding the potential implications of this

type of advanced technology. Wiener published his book, The Human Use

of Human Beings, in 1950. Although the term computer ethics was not

used by Wiener and it was decades later that the term came into general

use, his work certainly laid the foundation for future study and analysis.

His book became a cornerstone for the study of computer ethics. In it,

Wiener talks about the purpose of human life and the four principles of

justice, but he also offers discussion, application, and examples of what

would come to be recognized as computer ethics. (Bynum, 2001)

It wasn't until the 1970s that computer ethics began to garner interest.

Walter Maner, a university professor then at Old Dominion University,

offered a course in computer ethics to examine the ethical problems

created, exacerbated, or changed due to computer technology (Bynum,

United States form of governm

Fairness and Justice

Approach

Aristotle Equals should be treated equa

favoritism and discrimination a

unethical.

Virtue Predominantly

influenced by Plato

and Artistotle

Seeks to encourage all to deve

their highest potential

Return to top of page

Computer Ethics

What is computer ethics? This term can be used in a variety of ways. It

may refer to applying traditional ethical theories to IT situations, or it may

entail the broader application that we see with the prevalence of ethical

codes, standards of conduct, and new areas of computer law and policy.

There also is an increasing interest in how sociology and psychology

relate to computing. Scholars generally agree that the study of computer

ethics began with Norbert Wiener, an MIT professor who worked during

World War II to develop an anti-aircraft cannon. His work in the 1940s

prompted Wiener and his associates to create a new field of study that

Wiener labeled cybernetics. Their work fostered the development of

several ethical conclusions regarding the potential implications of this

type of advanced technology. Wiener published his book, The Human Use

of Human Beings, in 1950. Although the term computer ethics was not

used by Wiener and it was decades later that the term came into general

use, his work certainly laid the foundation for future study and analysis.

His book became a cornerstone for the study of computer ethics. In it,

Wiener talks about the purpose of human life and the four principles of

justice, but he also offers discussion, application, and examples of what

would come to be recognized as computer ethics. (Bynum, 2001)

It wasn't until the 1970s that computer ethics began to garner interest.

Walter Maner, a university professor then at Old Dominion University,

offered a course in computer ethics to examine the ethical problems

created, exacerbated, or changed due to computer technology (Bynum,

2001). Through the 70s and 80s, interest increased in this area, and in

1985, Deborah Johnson (previously referenced in this module) authored

the first textbook on the subject, Computer Ethics. Both Maner and

Johnson advocated the application of concepts from the ethical theories of

utilitarianism and Kantianism. However, in 1985, James Moor published a

broader definition of computer ethics in his article "What is Computer

Ethics?" He states: "computer ethics is the analysis of the nature and

social impact of computer technology and the corresponding formulation

and justification of policies for the ethical use of such technology" (Moor,

1985, p. 266). His definition was in line with several frameworks for

ethical problem-solving rather than the specific application of any

philosopher's theory. With the potentially limitless ability of computing

comes a dynamic, evolutionary flow of related ethical dilemmas. Moor

indicated that as computer technology became more entwined with

people and their everyday activities, the ethical challenges would become

more difficult to conceptualize and do not lend themselves to the

development of a static set of rules (Moor, 1985).

Throughout the 1990s and continuing into the new millennium, we've

seen tremendous developments in the field of technology. Not

surprisingly, with these developments, we've seen the wide-spread

adoption of computers to almost every application imaginable, including

the affordability and prevalence of computers in homes and businesses.

Professional associations have adopted codes of conduct for their

members, organizations have developed ethical codes and standards of

conduct for employees, and the IT field has focused increased efforts in

addressing the ethical situations and challenges that have unfolded.

In the following modules, we will explore how to apply these traditional

theories and analysis and problem-solving frameworks to effectively

understand and address ethical challenges in the information age.

Return to top of page

References

Bynum, T. (2001).Computer ethics: Basic concepts and historical

overview. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy

(Winter 2001 ed.). Retrieved July 7, 2005, from

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2001/entries/ethics-computer/

Hartley, R. F. (1993). Business ethics: Violations of the public trust. New

York: John Wiley.

Hursthouse, R. (2003). Virtue ethics. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford

encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2003 ed.). Retrieved July 2, 2005, from

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2003/entries/ethics-virtue/

Johnson, D. G. (2001). Computer ethics (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New

Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Kidder, R. M. (1995). How good people make tough choices: Resolving the

1985, Deborah Johnson (previously referenced in this module) authored

the first textbook on the subject, Computer Ethics. Both Maner and

Johnson advocated the application of concepts from the ethical theories of

utilitarianism and Kantianism. However, in 1985, James Moor published a

broader definition of computer ethics in his article "What is Computer

Ethics?" He states: "computer ethics is the analysis of the nature and

social impact of computer technology and the corresponding formulation

and justification of policies for the ethical use of such technology" (Moor,

1985, p. 266). His definition was in line with several frameworks for

ethical problem-solving rather than the specific application of any

philosopher's theory. With the potentially limitless ability of computing

comes a dynamic, evolutionary flow of related ethical dilemmas. Moor

indicated that as computer technology became more entwined with

people and their everyday activities, the ethical challenges would become

more difficult to conceptualize and do not lend themselves to the

development of a static set of rules (Moor, 1985).

Throughout the 1990s and continuing into the new millennium, we've

seen tremendous developments in the field of technology. Not

surprisingly, with these developments, we've seen the wide-spread

adoption of computers to almost every application imaginable, including

the affordability and prevalence of computers in homes and businesses.

Professional associations have adopted codes of conduct for their

members, organizations have developed ethical codes and standards of

conduct for employees, and the IT field has focused increased efforts in

addressing the ethical situations and challenges that have unfolded.

In the following modules, we will explore how to apply these traditional

theories and analysis and problem-solving frameworks to effectively

understand and address ethical challenges in the information age.

Return to top of page

References

Bynum, T. (2001).Computer ethics: Basic concepts and historical

overview. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy

(Winter 2001 ed.). Retrieved July 7, 2005, from

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2001/entries/ethics-computer/

Hartley, R. F. (1993). Business ethics: Violations of the public trust. New

York: John Wiley.

Hursthouse, R. (2003). Virtue ethics. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford

encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2003 ed.). Retrieved July 2, 2005, from

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2003/entries/ethics-virtue/

Johnson, D. G. (2001). Computer ethics (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New

Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Kidder, R. M. (1995). How good people make tough choices: Resolving the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

dilemmas of ethical living. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Narvan, F. Ask the expert: What is the difference between ethics, morals

and values? The Ethics Resource Center. Retrieved June 19, 2005, from

http://www.ethics.org/ask_e4.html

Williams, B. (1993). A critique of utilitarianism. In J.J.C. Smart & B.

Williams (Eds.), Utilitarianism: For and against. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Return to top of page

Report broken links or any other problems on this page.

Copyright © by University of Maryland University College.

Narvan, F. Ask the expert: What is the difference between ethics, morals

and values? The Ethics Resource Center. Retrieved June 19, 2005, from

http://www.ethics.org/ask_e4.html

Williams, B. (1993). A critique of utilitarianism. In J.J.C. Smart & B.

Williams (Eds.), Utilitarianism: For and against. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Return to top of page

Report broken links or any other problems on this page.

Copyright © by University of Maryland University College.

1 out of 10

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.