Ethical, Authentic, Servant Leadership vs Transformational Leadership

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/26

|29

|17762

|468

Literature Review

AI Summary

This study conducts a meta-analysis to compare three emerging forms of positive leadership—authentic, ethical, and servant leadership—with transformational leadership, focusing on their associations with organizationally relevant measures and their ability to explain incremental variance. The research involves comprehensive meta-analyses of each leadership form, relative weights analyses to determine the relative contributions of each form versus transformational leadership, and hierarchical regression to test incremental validity. The findings suggest that while authentic and ethical leadership show high correlations with transformational leadership and limited incremental variance, servant leadership demonstrates promise as a stand-alone approach. The study provides valuable insights into the utility of these ethical/moral values-based leadership forms and offers guidance for future research, with the full paper available on Desklib for students and researchers.

Journal of Management

Vol. XX No. X, Month XXXX 1 –29

DOI: 10.1177/0149206316665461

© The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

1

Do Ethical, Authentic, and Servant Leadership

Explain Variance Above and Beyond

Transformational Leadership? A Meta-Analysis

Julia E. Hoch

California State University–Northridge

William H. Bommer

California State University–Fresno

James H. Dulebohn

Dongyuan Wu

Michigan State University

This study compares three emerging forms of positive leadership that emphasize ethical and

moral behavior (i.e., authentic leadership, ethical leadership, and servant leadership) with

transformational leadership in their associations with a wide range of organizationally relevant

measures. While scholars have noted conceptual overlap between transformational leadership

and these newer leadership forms, there has been inadequate investigation of the empirical

relationships with transformational leadership and the ability (or lack thereof) of these leader-

ship forms to explain incremental variance beyond transformational leadership. In response, we

conducted a series of meta-analyses to provide a comprehensive assessment of these emerging

leadership forms’ relationships with variables evaluated in the extant literature. Second, we

tested the relative performance of each of these leadership forms in explaining incremental vari-

ance, beyond transformational leadership, in nine outcomes. We also provide relative weights

analyses to further evaluate the relative contributions of the emerging leadership forms versus

transformational leadership. The high correlations between both authentic leadership and ethi-

cal leadership with transformational leadership coupled with their low amounts of incremental

variance suggest that their utility is low unless they are being used to explore very specific

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge that earlier versions of this manuscript received helpful

comments from Brian Hoffman, associate editor, and two anonymous reviewers.

Supplemental material for this article is available at http://jom.sagepub.com/supplemental

Corresponding author: Julia E. Hoch, Nazarian College of Business, California State University–Northridge,

Los Angeles, CA 91330, USA.

E-mail: julia.hoch@csun.edu

665461 JOMXXX10.1177/0149206316665461Journal of Management Hoch et al.

research-article2016

Vol. XX No. X, Month XXXX 1 –29

DOI: 10.1177/0149206316665461

© The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

1

Do Ethical, Authentic, and Servant Leadership

Explain Variance Above and Beyond

Transformational Leadership? A Meta-Analysis

Julia E. Hoch

California State University–Northridge

William H. Bommer

California State University–Fresno

James H. Dulebohn

Dongyuan Wu

Michigan State University

This study compares three emerging forms of positive leadership that emphasize ethical and

moral behavior (i.e., authentic leadership, ethical leadership, and servant leadership) with

transformational leadership in their associations with a wide range of organizationally relevant

measures. While scholars have noted conceptual overlap between transformational leadership

and these newer leadership forms, there has been inadequate investigation of the empirical

relationships with transformational leadership and the ability (or lack thereof) of these leader-

ship forms to explain incremental variance beyond transformational leadership. In response, we

conducted a series of meta-analyses to provide a comprehensive assessment of these emerging

leadership forms’ relationships with variables evaluated in the extant literature. Second, we

tested the relative performance of each of these leadership forms in explaining incremental vari-

ance, beyond transformational leadership, in nine outcomes. We also provide relative weights

analyses to further evaluate the relative contributions of the emerging leadership forms versus

transformational leadership. The high correlations between both authentic leadership and ethi-

cal leadership with transformational leadership coupled with their low amounts of incremental

variance suggest that their utility is low unless they are being used to explore very specific

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge that earlier versions of this manuscript received helpful

comments from Brian Hoffman, associate editor, and two anonymous reviewers.

Supplemental material for this article is available at http://jom.sagepub.com/supplemental

Corresponding author: Julia E. Hoch, Nazarian College of Business, California State University–Northridge,

Los Angeles, CA 91330, USA.

E-mail: julia.hoch@csun.edu

665461 JOMXXX10.1177/0149206316665461Journal of Management Hoch et al.

research-article2016

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

outcomes. Servant leadership, however, showed more promise as a stand-alone leadership

approach that is capable of helping leadership researchers and practitioners better explain a

wide range of outcomes. Guidance regarding future research and the utility of these three ethi-

cal/moral values–based leadership forms is provided.

Keywords: meta-analysis; transformational leadership; authentic leadership; ethical leader-

ship; servant leadership; construct redundancy

In recent years, a series of very public corporate scandals (e.g., Enron, Fannie Mae,

Lehmann Brothers, Tyco, WorldCom) have been associated with increased interest in posi-

tive leadership emphasizing ethical and moral leader behavior. These emerging ethical/moral

values–based leadership forms include ethical, authentic, and servant leadership (Dinh, Lord,

Gardner, Meuser, Liden, & Hu, 2014). The focus upon moral and ethical behavior resulted

from a widely held view that crises of leadership, attributed to unethical behavior among

senior leaders in organizations (Woods & West, 2010), were responsible for these scandals.

The rising popularity of these three leadership forms is reflected in the increase in public as

well as scholarly references. A Google Scholar search for “ethical leadership” yielded 2,090

results for 1980 to 2003 versus 16,200 results for the period 2003 to 2016; for “authentic

leadership,” there were 926 versus 13,200 results; and for “servant leadership,” there were

2,630 versus 16,800 results, respectively.1

While there has been a meteoric rise in interest when it comes to these three leadership

forms, the field has provided little direction regarding whether these emerging approaches

actually perform as their supporters claim. In other words, while there is certainly a lot of

attention being focused upon these ethical/moral values–based leadership forms, it remains

to be seen whether they are actually explaining anything “new” at all. This is reflective of

scholars’ general concern regarding potential construct redundancy, which occurs when new

theories of leadership with new behavioral constructs are promoted without evaluating their

distinctiveness and usefulness compared to existing leadership approaches (DeRue,

Nahrgang, Wellman, & Humphrey, 2011).

These three ethical/moral values–based leadership forms represent additions to positive

leadership, with transformational leadership being the dominant theory since the 1980s.

Positive leadership forms focus on leader behaviors and interpersonal dynamics that increase

followers’ confidence and result in positive outcomes, beyond task compliance, such as moti-

vating followers to go beyond expectations, positive self-development, and prosocial behaviors

(cf. Hannah, Sumanth, Lester, & Cavarretta, 2014). Primary studies and meta-analyses on

transformational leadership have consistently demonstrated that transformational leadership

has high overall validity and is significantly related to a variety of employee and organizational

criteria, such as commitment, trust, satisfaction, and performance (e.g., Judge & Piccolo, 2004).

Theorists have provided potential justification for the ethical/moral values–based leader-

ship forms by arguing that transformational leadership may be viewed as incomplete as a

result of an absence of a strong, explicit moral dimension. Specifically, leaders, while being

“transformational,” may be unethical, abusive of followers, and act in ways that are self-

serving and contrary to espoused values and organizational interests (Bass & Steidlmeier,

1999; Conger & Kanungo, 1988). This has been exemplified by corporate failures occurring

outcomes. Servant leadership, however, showed more promise as a stand-alone leadership

approach that is capable of helping leadership researchers and practitioners better explain a

wide range of outcomes. Guidance regarding future research and the utility of these three ethi-

cal/moral values–based leadership forms is provided.

Keywords: meta-analysis; transformational leadership; authentic leadership; ethical leader-

ship; servant leadership; construct redundancy

In recent years, a series of very public corporate scandals (e.g., Enron, Fannie Mae,

Lehmann Brothers, Tyco, WorldCom) have been associated with increased interest in posi-

tive leadership emphasizing ethical and moral leader behavior. These emerging ethical/moral

values–based leadership forms include ethical, authentic, and servant leadership (Dinh, Lord,

Gardner, Meuser, Liden, & Hu, 2014). The focus upon moral and ethical behavior resulted

from a widely held view that crises of leadership, attributed to unethical behavior among

senior leaders in organizations (Woods & West, 2010), were responsible for these scandals.

The rising popularity of these three leadership forms is reflected in the increase in public as

well as scholarly references. A Google Scholar search for “ethical leadership” yielded 2,090

results for 1980 to 2003 versus 16,200 results for the period 2003 to 2016; for “authentic

leadership,” there were 926 versus 13,200 results; and for “servant leadership,” there were

2,630 versus 16,800 results, respectively.1

While there has been a meteoric rise in interest when it comes to these three leadership

forms, the field has provided little direction regarding whether these emerging approaches

actually perform as their supporters claim. In other words, while there is certainly a lot of

attention being focused upon these ethical/moral values–based leadership forms, it remains

to be seen whether they are actually explaining anything “new” at all. This is reflective of

scholars’ general concern regarding potential construct redundancy, which occurs when new

theories of leadership with new behavioral constructs are promoted without evaluating their

distinctiveness and usefulness compared to existing leadership approaches (DeRue,

Nahrgang, Wellman, & Humphrey, 2011).

These three ethical/moral values–based leadership forms represent additions to positive

leadership, with transformational leadership being the dominant theory since the 1980s.

Positive leadership forms focus on leader behaviors and interpersonal dynamics that increase

followers’ confidence and result in positive outcomes, beyond task compliance, such as moti-

vating followers to go beyond expectations, positive self-development, and prosocial behaviors

(cf. Hannah, Sumanth, Lester, & Cavarretta, 2014). Primary studies and meta-analyses on

transformational leadership have consistently demonstrated that transformational leadership

has high overall validity and is significantly related to a variety of employee and organizational

criteria, such as commitment, trust, satisfaction, and performance (e.g., Judge & Piccolo, 2004).

Theorists have provided potential justification for the ethical/moral values–based leader-

ship forms by arguing that transformational leadership may be viewed as incomplete as a

result of an absence of a strong, explicit moral dimension. Specifically, leaders, while being

“transformational,” may be unethical, abusive of followers, and act in ways that are self-

serving and contrary to espoused values and organizational interests (Bass & Steidlmeier,

1999; Conger & Kanungo, 1988). This has been exemplified by corporate failures occurring

Hoch et al. / Emerging Forms of Leadership 3

under leaders widely viewed as transformational, such as Ken Lay (Tourish, 2013) and Al

Dunlap (Fastenburg, 2010). In response, scholars introduced a distinction between authentic

and pseudo transformational leadership, to account for the presence or absence of ethical and

positive moral character in transformational leaders (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Price, 2003),

and advanced ethically oriented leadership forms, including authentic, ethical, and servant

leadership (Northouse, 2010).

Consistent with the DeRue et al. (2011) call for integration across leadership forms, the

current study seeks not only to understand the three ethical/moral values–based leadership

forms but also to assess these leadership forms in the context of transformational leadership.2

With the promotion of these ethically oriented leadership approaches, there has been an

accompanying concern as to whether they are conceptually distinct from transformational

leadership (e.g., Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Adding further concern to the issues of distinct-

ness, extant research has provided some empirical evidence of significant associations

between transformational leadership and ethical (cf. Ng & Feldman, 2015), authentic (cf.

Riggio, Zhu, Reina, & Maroosis, 2010), and servant leadership (cf. van Dierendonck, Stam,

Boersma, de Windt, & Alkema, 2014).

Some attention has been given in primary studies to examining the predictive validity of

these emerging forms of leadership above transformational leadership on a few correlates

(Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, 2005; Liden, Wayne, Zhao, & Henderson, 2008). To date, how-

ever, their incremental validity in relation to transformational leadership in explaining key

outcomes is unknown. This is not to say, however, that no one has started the evaluation pro-

cess. More specifically, two meta-analyses have been recently conducted on ethical leadership

(Bedi, Alpaslan, & Green, in press; Ng & Feldman, 2015), but none have been conducted on

authentic or servant leadership. Ng and Feldman (2015) did a narrow analysis of the predictive

validity of ethical leadership, in the presence of transformational leadership, on task perfor-

mance and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) and found some support.

Consequently, questions exist whether these “new additions” make unique contributions to

explaining key measures beyond those provided by transformational leadership (cf. Haynes &

Lench, 2003). Therefore, this study’s objective is to evaluate the incremental validity of the

three ethical/moral forms of leadership to determine whether they add to the prediction of

criteria above those explained by transformational leadership alone. Testing the incremental

validity of each emerging leadership approach is important to inform the optimal array of

leadership forms and evaluate potential construct redundancy. Furthermore, the study repre-

sents a response to calls to evaluate incremental validity on related constructs, which has been

a neglected focus “in most areas of applied psychology” (Hunsley & Meyer, 2003: 446).

To effectively accomplish the above goals, we present three distinct yet related sets of

analyses. First, we conduct a separate broad-based, comprehensive meta-analysis for each of

the three emerging leadership forms to determine their associations with organizationally

relevant variables. Consequently, this study is the first to provide comprehensive meta-anal-

yses on authentic and servant leadership. For ethical leadership, we expand upon the prior

meta-analyses by including a larger number of independent studies and correlates. Together,

we are able to meta-analyze 20, 15, and 11 correlates for ethical, authentic, and servant lead-

ership, respectively.

Once these three comprehensive meta-analyses of the emerging leadership forms are pre-

sented, we select nine correlates shared across the analyses and investigate the relative

under leaders widely viewed as transformational, such as Ken Lay (Tourish, 2013) and Al

Dunlap (Fastenburg, 2010). In response, scholars introduced a distinction between authentic

and pseudo transformational leadership, to account for the presence or absence of ethical and

positive moral character in transformational leaders (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Price, 2003),

and advanced ethically oriented leadership forms, including authentic, ethical, and servant

leadership (Northouse, 2010).

Consistent with the DeRue et al. (2011) call for integration across leadership forms, the

current study seeks not only to understand the three ethical/moral values–based leadership

forms but also to assess these leadership forms in the context of transformational leadership.2

With the promotion of these ethically oriented leadership approaches, there has been an

accompanying concern as to whether they are conceptually distinct from transformational

leadership (e.g., Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Adding further concern to the issues of distinct-

ness, extant research has provided some empirical evidence of significant associations

between transformational leadership and ethical (cf. Ng & Feldman, 2015), authentic (cf.

Riggio, Zhu, Reina, & Maroosis, 2010), and servant leadership (cf. van Dierendonck, Stam,

Boersma, de Windt, & Alkema, 2014).

Some attention has been given in primary studies to examining the predictive validity of

these emerging forms of leadership above transformational leadership on a few correlates

(Brown, Treviño, & Harrison, 2005; Liden, Wayne, Zhao, & Henderson, 2008). To date, how-

ever, their incremental validity in relation to transformational leadership in explaining key

outcomes is unknown. This is not to say, however, that no one has started the evaluation pro-

cess. More specifically, two meta-analyses have been recently conducted on ethical leadership

(Bedi, Alpaslan, & Green, in press; Ng & Feldman, 2015), but none have been conducted on

authentic or servant leadership. Ng and Feldman (2015) did a narrow analysis of the predictive

validity of ethical leadership, in the presence of transformational leadership, on task perfor-

mance and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) and found some support.

Consequently, questions exist whether these “new additions” make unique contributions to

explaining key measures beyond those provided by transformational leadership (cf. Haynes &

Lench, 2003). Therefore, this study’s objective is to evaluate the incremental validity of the

three ethical/moral forms of leadership to determine whether they add to the prediction of

criteria above those explained by transformational leadership alone. Testing the incremental

validity of each emerging leadership approach is important to inform the optimal array of

leadership forms and evaluate potential construct redundancy. Furthermore, the study repre-

sents a response to calls to evaluate incremental validity on related constructs, which has been

a neglected focus “in most areas of applied psychology” (Hunsley & Meyer, 2003: 446).

To effectively accomplish the above goals, we present three distinct yet related sets of

analyses. First, we conduct a separate broad-based, comprehensive meta-analysis for each of

the three emerging leadership forms to determine their associations with organizationally

relevant variables. Consequently, this study is the first to provide comprehensive meta-anal-

yses on authentic and servant leadership. For ethical leadership, we expand upon the prior

meta-analyses by including a larger number of independent studies and correlates. Together,

we are able to meta-analyze 20, 15, and 11 correlates for ethical, authentic, and servant lead-

ership, respectively.

Once these three comprehensive meta-analyses of the emerging leadership forms are pre-

sented, we select nine correlates shared across the analyses and investigate the relative

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

weights (cf. Tonidandel & LeBreton, 2011) of the relationships between the new leadership

forms and the correlates versus transformational leadership and the correlates. The relative

weights approach takes a different quantitative and philosophical perspective than the incre-

mental validity tests, which will also be conducted. Rather than putting the burden of proof

on the new leadership forms to explain incremental variance, the relative weights analyses

partition the variance explained to determine the relative variance explained by each of the

new forms versus that explained by transformational leadership.

Next, we use hierarchical regression results to test the incremental validity provided by

each of the three emerging leadership forms as compared to transformational leadership. The

transformational leadership associations are based on a fourth meta-analysis we conduct on

transformational leadership that includes the nine shared correlates from the ethical/moral

values–based leadership forms’ analyses.

The above analyses allow the current research to accomplish four major objectives. First,

we provide comprehensive summaries of the ethical/moral values–based leadership forms

and their relationships with an array of relevant measures. Second, we present the largest

meta-analysis of transformational leadership done to date. Third, we present the relative vari-

ance in organizationally relevant outcomes explained by the different leadership forms.

Fourth, we assess whether these emerging forms of leadership are redundant and to what

degree they explain incremental variance beyond that already explained by transformational

leadership.

Theoretical Background and Expectations

Transformational Leadership

Beginning in the late 1970s, leadership research experienced a paradigm shift away from

traditional or classical leadership approaches to what has been labeled positive forms of

leadership (cf. Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Burns (1978) introduced transformational leader-

ship to describe the ideal situation between political leaders and their followers. Burns speci-

fied transformational leadership as an ongoing process, whereby “leaders and followers raise

one another to higher levels of morality and motivation beyond self-interest to serve collec-

tive interests” (20). He contrasted transformational and transactional leadership (which is

based upon contingent reinforcement and is focused on short-term goals, self-interest, and

the exchange relationship). This positive leadership theory highlighted leaders’ ability to

influence positive follower outcomes through identifying and addressing followers’ needs

and transforming them by inspiring trust, instilling pride, communicating vision, and moti-

vating followers to perform at higher levels (cf. Turner, Barling, & Zacharatos, 2002).3

Bass (1985) developed and expanded Burn’s (1978) political concept of transformational

leadership and applied it to organizational contexts. Bass defined the process of transforma-

tional leadership in terms of a leader’s ability “to achieve follower performance beyond

ordinary limits” (xiii). In contrast to Burns, Bass’s initial conceptualization and application

of transformational leadership to organizations did not specify an ethical or moral dimension

but highlighted the importance of such later (cf. Bass & Riggio, 2006). According to Bass,

transformational leaders transform their followers to perform beyond expectations by engag-

ing in “the four Is” of behavior: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual

stimulation, and individualized consideration.

weights (cf. Tonidandel & LeBreton, 2011) of the relationships between the new leadership

forms and the correlates versus transformational leadership and the correlates. The relative

weights approach takes a different quantitative and philosophical perspective than the incre-

mental validity tests, which will also be conducted. Rather than putting the burden of proof

on the new leadership forms to explain incremental variance, the relative weights analyses

partition the variance explained to determine the relative variance explained by each of the

new forms versus that explained by transformational leadership.

Next, we use hierarchical regression results to test the incremental validity provided by

each of the three emerging leadership forms as compared to transformational leadership. The

transformational leadership associations are based on a fourth meta-analysis we conduct on

transformational leadership that includes the nine shared correlates from the ethical/moral

values–based leadership forms’ analyses.

The above analyses allow the current research to accomplish four major objectives. First,

we provide comprehensive summaries of the ethical/moral values–based leadership forms

and their relationships with an array of relevant measures. Second, we present the largest

meta-analysis of transformational leadership done to date. Third, we present the relative vari-

ance in organizationally relevant outcomes explained by the different leadership forms.

Fourth, we assess whether these emerging forms of leadership are redundant and to what

degree they explain incremental variance beyond that already explained by transformational

leadership.

Theoretical Background and Expectations

Transformational Leadership

Beginning in the late 1970s, leadership research experienced a paradigm shift away from

traditional or classical leadership approaches to what has been labeled positive forms of

leadership (cf. Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Burns (1978) introduced transformational leader-

ship to describe the ideal situation between political leaders and their followers. Burns speci-

fied transformational leadership as an ongoing process, whereby “leaders and followers raise

one another to higher levels of morality and motivation beyond self-interest to serve collec-

tive interests” (20). He contrasted transformational and transactional leadership (which is

based upon contingent reinforcement and is focused on short-term goals, self-interest, and

the exchange relationship). This positive leadership theory highlighted leaders’ ability to

influence positive follower outcomes through identifying and addressing followers’ needs

and transforming them by inspiring trust, instilling pride, communicating vision, and moti-

vating followers to perform at higher levels (cf. Turner, Barling, & Zacharatos, 2002).3

Bass (1985) developed and expanded Burn’s (1978) political concept of transformational

leadership and applied it to organizational contexts. Bass defined the process of transforma-

tional leadership in terms of a leader’s ability “to achieve follower performance beyond

ordinary limits” (xiii). In contrast to Burns, Bass’s initial conceptualization and application

of transformational leadership to organizations did not specify an ethical or moral dimension

but highlighted the importance of such later (cf. Bass & Riggio, 2006). According to Bass,

transformational leaders transform their followers to perform beyond expectations by engag-

ing in “the four Is” of behavior: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual

stimulation, and individualized consideration.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Hoch et al. / Emerging Forms of Leadership 5

During the past three decades, a majority of organizational leadership research has been

based on transformational leadership (cf. Judge & Piccolo, 2004). Numerous empirical studies

have supported a relationship between transformational leadership and leader effectiveness in

terms of follower attitudinal outcomes; organizational climate; OCBs; individual, group, and

organizational performance; job satisfaction; supervisor satisfaction; engagement; and reduced

turnover (e.g., Bass, Avolio, Jung, & Berson, 2003; Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt, & Van Engen,

2003; Judge & Piccolo, 2004; Wang, Oh, Courtright, & Colbert, 2011).

The delineation of authentic and pseudo transformational leadership by Bass and

Steidlmeier (1999) was based on a recognition that leaders could potentially engage in “inau-

thentic” transformational leadership (cf. Conger & Kanungo, 1988). Bass and Steidlmeier

stated: “Each component of either transaction or transformational leadership has an ethical

dimension. It is the behavior of leaders—including their moral character, values and pro-

grams—that is authentic to less authentic rather than authentic or inauthentic” (184).

Authenticity refers to being true and acting consistently with one’s own self and values and

being transparent regarding those values. Authentic leaders are aware of their beliefs and

values, and they are genuine, reliable, moral, other focused, and devoted to developing fol-

lowers and creating a positive and engaging organizational context (Ilies, Morgeson, &

Nahrgang, 2005).

Authentic Leadership

Luthans and Avolio (2003) proposed authentic leadership as a specific leadership form. It

was further developed by Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, and Walumbwa (2005) and Avolio

and Luthans (2006) following major corporate scandals. Authentic leaders are described as

high on moral character and those who are “deeply aware of how they think and behave and

are perceived by others as being aware of their own and others’ values/moral perspectives,

knowledge, and strengths” (Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, 2004: 802).

Authentic leadership is viewed as a root concept or precursor to all other forms of positive

leadership including transformational, ethical, and servant leadership (Avolio & Gardner,

2005). Thus, the degree of authenticity represents an underlying determinant or wellspring

defining positive leadership. For example, with respect to transformational leadership, it

answers the question: Is the leader’s leadership genuine and beneficial to followers and orga-

nizations, or is it abusive and unethical?

Although a number of definitions of authentic leadership have been proposed, Avolio and

Gardner (2005) identified the following dimensions of authentic leadership: positive moral

perspective, self-awareness, balanced processing, relational transparency, positive psycho-

logical capital, and authentic behavior. In addition, authentic leadership has a strong devel-

opmental focus in terms of both moral development of the leader and development of

authenticity in followers (Avolio & Gardner, 2005). The positive moral perspective dimen-

sion highlights that authentic leadership requires a leader’s actions to be based on internal-

ized positive virtues and high moral character. Regarding self-awareness, authentic leaders

are cognizant of their strengths, knowledge, beliefs, and values and act on these openly and

candidly (Avolio et al., 2004). Balanced processing reflects an inclination to objectively con-

sider and weigh multiple perspectives and listen to others when processing information and

before making decisions. Relational transparency describes the open and transparent manner

with which authentic leaders share information about themselves to followers, including

During the past three decades, a majority of organizational leadership research has been

based on transformational leadership (cf. Judge & Piccolo, 2004). Numerous empirical studies

have supported a relationship between transformational leadership and leader effectiveness in

terms of follower attitudinal outcomes; organizational climate; OCBs; individual, group, and

organizational performance; job satisfaction; supervisor satisfaction; engagement; and reduced

turnover (e.g., Bass, Avolio, Jung, & Berson, 2003; Eagly, Johannesen-Schmidt, & Van Engen,

2003; Judge & Piccolo, 2004; Wang, Oh, Courtright, & Colbert, 2011).

The delineation of authentic and pseudo transformational leadership by Bass and

Steidlmeier (1999) was based on a recognition that leaders could potentially engage in “inau-

thentic” transformational leadership (cf. Conger & Kanungo, 1988). Bass and Steidlmeier

stated: “Each component of either transaction or transformational leadership has an ethical

dimension. It is the behavior of leaders—including their moral character, values and pro-

grams—that is authentic to less authentic rather than authentic or inauthentic” (184).

Authenticity refers to being true and acting consistently with one’s own self and values and

being transparent regarding those values. Authentic leaders are aware of their beliefs and

values, and they are genuine, reliable, moral, other focused, and devoted to developing fol-

lowers and creating a positive and engaging organizational context (Ilies, Morgeson, &

Nahrgang, 2005).

Authentic Leadership

Luthans and Avolio (2003) proposed authentic leadership as a specific leadership form. It

was further developed by Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, and Walumbwa (2005) and Avolio

and Luthans (2006) following major corporate scandals. Authentic leaders are described as

high on moral character and those who are “deeply aware of how they think and behave and

are perceived by others as being aware of their own and others’ values/moral perspectives,

knowledge, and strengths” (Avolio, Gardner, Walumbwa, Luthans, & May, 2004: 802).

Authentic leadership is viewed as a root concept or precursor to all other forms of positive

leadership including transformational, ethical, and servant leadership (Avolio & Gardner,

2005). Thus, the degree of authenticity represents an underlying determinant or wellspring

defining positive leadership. For example, with respect to transformational leadership, it

answers the question: Is the leader’s leadership genuine and beneficial to followers and orga-

nizations, or is it abusive and unethical?

Although a number of definitions of authentic leadership have been proposed, Avolio and

Gardner (2005) identified the following dimensions of authentic leadership: positive moral

perspective, self-awareness, balanced processing, relational transparency, positive psycho-

logical capital, and authentic behavior. In addition, authentic leadership has a strong devel-

opmental focus in terms of both moral development of the leader and development of

authenticity in followers (Avolio & Gardner, 2005). The positive moral perspective dimen-

sion highlights that authentic leadership requires a leader’s actions to be based on internal-

ized positive virtues and high moral character. Regarding self-awareness, authentic leaders

are cognizant of their strengths, knowledge, beliefs, and values and act on these openly and

candidly (Avolio et al., 2004). Balanced processing reflects an inclination to objectively con-

sider and weigh multiple perspectives and listen to others when processing information and

before making decisions. Relational transparency describes the open and transparent manner

with which authentic leaders share information about themselves to followers, including

6 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

their personal values, weaknesses, and limitations (Ilies et al., 2005). Also, authentic leaders

possess positive psychological capital in that they are confident, optimistic, hopeful, and

resilient (Luthans & Avolio, 2009). Furthermore, authentic leaders display “actions that are

guided by the leaders’ true self as reflected by core values, beliefs, thoughts and feelings, as

opposed to environmental contingencies or pressures from others” (Gardner et al., 2005: 347).

In comparing authentic and transformational leadership, Avolio et al. (2004) described

authentic leadership as adding ethical leadership qualities to positive leadership forms. Thus,

leaders may be authentic but not transformational and simply display ethical characteristics

of authentic leadership. As a result, genuine transformational leaders must be authentic

(Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Although the ethical aspects of authentic leadership are additions

to components of transformational leadership identified by Bass (1985, 1998), in light of the

positive capital attributes, there appears to be significant conceptual overlap between authen-

tic and transformational leadership.

Ethical Leadership

Brown et al. defined ethical leadership as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate

conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such

conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-mak-

ing” (2005: 120). They identified how ethical leadership differs from other positive leader-

ship forms. First, ethical leadership focuses on the ethical dimension of leadership rather than

including ethics as an ancillary dimension (Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador,

2009). Second, Brown et al. (2005) described ethical leadership as including trait (i.e., the

moral person) and behavior (i.e., the moral manager) dimensions. They argued that ethical

leadership can be reflected by leader traits, such as integrity, social responsibility, fairness, and

the willingness to think through the consequences of one’s actions. However, ethical leadership

is also reflected by specific behaviors, whereby the leader promotes workplace ethicality.

Ethical leaders seek to do the right thing and conduct their lives and leadership roles in an

ethical manner (Brown & Treviño, 2006). Ethical leadership draws on social learning theory

(Bandura, 1986) and posits that ethical leaders influence followers to engage in ethical

behaviors through behavioral modeling and transactional leadership behaviors (e.g., reward-

ing, communicating, and punishing). The recent focus on ethical leadership has been based

on the belief that ethics represent a critical component in effective leadership and leaders are

responsible for promoting ethical climates and behavior (Brown & Treviño, 2006). In com-

paring ethical leadership and transformational leadership, the empirical findings generally

suggest a strong relationship (cf. Brown & Treviño, 2006; Mayer, Aquino, Greenbaum, &

Kuenzi, 2012) with the exception of a study by Brown et al. (2005) that reported a relatively

weak association between ethical leadership and idealized influence (r = .20, p < .01).

Servant Leadership

Robert Greenleaf (1970, 1977) developed the philosophy of servant leadership that

focuses on putting the needs of followers and stakeholders first. Greenleaf stated: “The ser-

vant-leader is servant first. It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve. Then

conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead” (1970: 13). Keith (2008) described servant

their personal values, weaknesses, and limitations (Ilies et al., 2005). Also, authentic leaders

possess positive psychological capital in that they are confident, optimistic, hopeful, and

resilient (Luthans & Avolio, 2009). Furthermore, authentic leaders display “actions that are

guided by the leaders’ true self as reflected by core values, beliefs, thoughts and feelings, as

opposed to environmental contingencies or pressures from others” (Gardner et al., 2005: 347).

In comparing authentic and transformational leadership, Avolio et al. (2004) described

authentic leadership as adding ethical leadership qualities to positive leadership forms. Thus,

leaders may be authentic but not transformational and simply display ethical characteristics

of authentic leadership. As a result, genuine transformational leaders must be authentic

(Avolio & Gardner, 2005). Although the ethical aspects of authentic leadership are additions

to components of transformational leadership identified by Bass (1985, 1998), in light of the

positive capital attributes, there appears to be significant conceptual overlap between authen-

tic and transformational leadership.

Ethical Leadership

Brown et al. defined ethical leadership as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate

conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such

conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-mak-

ing” (2005: 120). They identified how ethical leadership differs from other positive leader-

ship forms. First, ethical leadership focuses on the ethical dimension of leadership rather than

including ethics as an ancillary dimension (Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador,

2009). Second, Brown et al. (2005) described ethical leadership as including trait (i.e., the

moral person) and behavior (i.e., the moral manager) dimensions. They argued that ethical

leadership can be reflected by leader traits, such as integrity, social responsibility, fairness, and

the willingness to think through the consequences of one’s actions. However, ethical leadership

is also reflected by specific behaviors, whereby the leader promotes workplace ethicality.

Ethical leaders seek to do the right thing and conduct their lives and leadership roles in an

ethical manner (Brown & Treviño, 2006). Ethical leadership draws on social learning theory

(Bandura, 1986) and posits that ethical leaders influence followers to engage in ethical

behaviors through behavioral modeling and transactional leadership behaviors (e.g., reward-

ing, communicating, and punishing). The recent focus on ethical leadership has been based

on the belief that ethics represent a critical component in effective leadership and leaders are

responsible for promoting ethical climates and behavior (Brown & Treviño, 2006). In com-

paring ethical leadership and transformational leadership, the empirical findings generally

suggest a strong relationship (cf. Brown & Treviño, 2006; Mayer, Aquino, Greenbaum, &

Kuenzi, 2012) with the exception of a study by Brown et al. (2005) that reported a relatively

weak association between ethical leadership and idealized influence (r = .20, p < .01).

Servant Leadership

Robert Greenleaf (1970, 1977) developed the philosophy of servant leadership that

focuses on putting the needs of followers and stakeholders first. Greenleaf stated: “The ser-

vant-leader is servant first. It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve. Then

conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead” (1970: 13). Keith (2008) described servant

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Hoch et al. / Emerging Forms of Leadership 7

leadership as ethical, practical, and meaningful. On the basis of Greenleaf’s writings, Spears

(2010) identified 10 characteristics of servant leaders, including listening, empathy, healing,

awareness, persuasion, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, commitment to the growth

of others, and building community. Servant leadership posits that by first facilitating the

development and well-being of followers, long-term organizational goals will be achieved.

According to Bass, servant leadership has numerous parallels with transformational lead-

ership, including “needing vision, influence, credibility, trust and service but it goes beyond

transformational leadership in selecting the needs of others as its highest priority” (2000: 33).

Furthermore, Bass stated that the two leadership forms are most similar with respect to the

transformational leadership facets of inspirational motivation and individualized consider-

ation. Stone, Russell, and Patterson (2003) noted that the major difference between transfor-

mational leadership and servant leadership is the leader’s primary focus. Servant leaders’

principal focus is on their followers; transformational leaders primarily focus on organiza-

tional objectives and inspiring follower commitment toward those objectives. Overall, it

appears that there are certainly conceptual similarities and differences between servant and

transformational leadership, but whether the conceptual overlap is associated with significant

empirical overlap is explored in the current research.

Expectations for the Emerging Leadership Forms

Not surprisingly, the research focus to date of the emerging leadership forms has been on

their individual consequences, not on their incremental contributions when compared to

transformational leadership. Therefore, we examine a number of organizationally relevant

measures in our comparison of authentic leadership, ethical leadership, and servant leader-

ship with transformational leadership by using meta-analytic techniques. Specifically, the

extant research allowed us to include the behavioral outcomes of job performance, OCBs,

and deviance; attitudinal outcomes of employee engagement, job satisfaction, affective com-

mitment, and organizational commitment; and relational perception measures of trust and

leader-member exchange (LMX). While not proposing formal hypotheses for the variance

explained by each new leadership form with each outcome, we present expectations as

follows.

Behavioral outcomes. A central emphasis of transformational leadership is fostering fol-

lower identification with organizational goals and influencing followers to engage in in-role

performance that exceeds expectations (Bass, 1985). Empirical investigation of transforma-

tional leadership has provided strong support for positive associations between transforma-

tional leadership and individual performance. For example, in their meta-analyses, Wang

et al. (2011) and Fuller, Patterson, Hester, and Stringer (1996) found overall effect sizes (ρs)

between transformational leadership and job performance of .25 and .45, respectively.

In contrast to transformational leadership, authentic, ethical, and servant leadership do not

have as strong an emphasis on affecting follower in-role performance. Rather, the focus of

these emerging leadership forms, as a group, appears to be directed more to ethical behav-

ioral role modeling by leaders, social learning, moral development of followers, and promo-

tion of socially and normatively appropriate, as well as extrarole, behavior (Avolio &

Luthans, 2006; Brown et al., 2005; Gardner et al., 2005; Hu & Liden, 2013). Consequently,

leadership as ethical, practical, and meaningful. On the basis of Greenleaf’s writings, Spears

(2010) identified 10 characteristics of servant leaders, including listening, empathy, healing,

awareness, persuasion, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, commitment to the growth

of others, and building community. Servant leadership posits that by first facilitating the

development and well-being of followers, long-term organizational goals will be achieved.

According to Bass, servant leadership has numerous parallels with transformational lead-

ership, including “needing vision, influence, credibility, trust and service but it goes beyond

transformational leadership in selecting the needs of others as its highest priority” (2000: 33).

Furthermore, Bass stated that the two leadership forms are most similar with respect to the

transformational leadership facets of inspirational motivation and individualized consider-

ation. Stone, Russell, and Patterson (2003) noted that the major difference between transfor-

mational leadership and servant leadership is the leader’s primary focus. Servant leaders’

principal focus is on their followers; transformational leaders primarily focus on organiza-

tional objectives and inspiring follower commitment toward those objectives. Overall, it

appears that there are certainly conceptual similarities and differences between servant and

transformational leadership, but whether the conceptual overlap is associated with significant

empirical overlap is explored in the current research.

Expectations for the Emerging Leadership Forms

Not surprisingly, the research focus to date of the emerging leadership forms has been on

their individual consequences, not on their incremental contributions when compared to

transformational leadership. Therefore, we examine a number of organizationally relevant

measures in our comparison of authentic leadership, ethical leadership, and servant leader-

ship with transformational leadership by using meta-analytic techniques. Specifically, the

extant research allowed us to include the behavioral outcomes of job performance, OCBs,

and deviance; attitudinal outcomes of employee engagement, job satisfaction, affective com-

mitment, and organizational commitment; and relational perception measures of trust and

leader-member exchange (LMX). While not proposing formal hypotheses for the variance

explained by each new leadership form with each outcome, we present expectations as

follows.

Behavioral outcomes. A central emphasis of transformational leadership is fostering fol-

lower identification with organizational goals and influencing followers to engage in in-role

performance that exceeds expectations (Bass, 1985). Empirical investigation of transforma-

tional leadership has provided strong support for positive associations between transforma-

tional leadership and individual performance. For example, in their meta-analyses, Wang

et al. (2011) and Fuller, Patterson, Hester, and Stringer (1996) found overall effect sizes (ρs)

between transformational leadership and job performance of .25 and .45, respectively.

In contrast to transformational leadership, authentic, ethical, and servant leadership do not

have as strong an emphasis on affecting follower in-role performance. Rather, the focus of

these emerging leadership forms, as a group, appears to be directed more to ethical behav-

ioral role modeling by leaders, social learning, moral development of followers, and promo-

tion of socially and normatively appropriate, as well as extrarole, behavior (Avolio &

Luthans, 2006; Brown et al., 2005; Gardner et al., 2005; Hu & Liden, 2013). Consequently,

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

we do not expect significant incremental variance in explaining job performance from these

emerging forms.

With respect to OCBs, the meta-analysis of Wang et al. (2011) reported an association

between transformational leadership and this outcome (ρ = .30). Nevertheless, we expect the

emerging leadership forms will contribute significant incremental variance in explaining

both employee OCBs and reducing employee deviance above transformational leadership as

a result of their focus on the promotion of extrarole and normatively appropriate behaviors.

Attitudinal outcomes. Attitudinal outcomes include employee engagement, job satisfac-

tion, affective commitment, and organizational commitment. Employee engagement has

been defined as a “positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by

vigor, dedication, and absorption to one’s work” (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, &

Bakker, 2002: 74). A general assumption is that transformational leaders are motivational,

charismatic, engaged, and visionary and influence followers to experience identification with

organizational goals. Transformational leaders also have been described as leading followers

to view their work as more important and self-congruent (Shamir, House, & Arthur, 1993).

Bono and Judge (2003) noted that transformational leaders influence followers through value

internalization and work engagement. In addition, Judge and Piccolo’s (2004) meta-analysis

demonstrated that follower engagement (ρ = .53) and follower job satisfaction (ρ = .58) were

strongly associated with transformational leadership.

Researchers have found engagement and job satisfaction to be positively associated with

authentic leadership (Neider & Schriesheim, 2011; Wong, Laschinger, & Cummings, 2010),

ethical leadership (Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012; Neubert, Carlson, Kacmar, Roberts, &

Chonko, 2009), and servant leadership (Chan & Mak, 2014; E. M. Hunter, Neubert, Perry,

Witt, Penney, & Weinberger, 2013). This may occur through authentic leadership’s personal

identification with followers, ethical leadership’s emphasis on fair treatment of followers,

and servant leadership’s focus on serving followers, thus promoting identification with the

leader that could contribute to employee work engagement and engender positive attitudes,

such as job satisfaction. In spite of these associations, because of the centrality of these out-

comes to transformational leadership, we do not expect the new forms of leadership to add

significant incremental validity above transformational leadership for engagement and job

satisfaction for both the theoretical and empirical reasons provided above.

Although the literature does not directly support a significant incremental effect upon the

previous discussed attitudinal measures, a different picture emerges for employee commit-

ment. Organizational commitment has been defined as “the relative strength of an individu-

al’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization” (Mowday & Steers,

1979: 226), and affective commitment refers to employees’ emotional bonds to their organi-

zations (Meyer & Allen, 1984). Researchers have found associations between transforma-

tional leadership and both organizational commitment (ρ = .43; DeGroot, Kiker, & Cross,

2000) and affective commitment (r = .33; Liao & Chuang, 2007). In spite of the positive

associations with transformational leadership, we expect that the three emerging leadership

forms will contribute incremental variance in explaining affective commitment and organi-

zational commitment. This expectation is based on empirical research supporting direct

effects of these three leadership forms on follower work attitudes, including organizational

commitment (cf. Leroy, Palanski, & Simons, 2012; Liden et al., 2008; Ng & Feldman, 2015),

we do not expect significant incremental variance in explaining job performance from these

emerging forms.

With respect to OCBs, the meta-analysis of Wang et al. (2011) reported an association

between transformational leadership and this outcome (ρ = .30). Nevertheless, we expect the

emerging leadership forms will contribute significant incremental variance in explaining

both employee OCBs and reducing employee deviance above transformational leadership as

a result of their focus on the promotion of extrarole and normatively appropriate behaviors.

Attitudinal outcomes. Attitudinal outcomes include employee engagement, job satisfac-

tion, affective commitment, and organizational commitment. Employee engagement has

been defined as a “positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by

vigor, dedication, and absorption to one’s work” (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, &

Bakker, 2002: 74). A general assumption is that transformational leaders are motivational,

charismatic, engaged, and visionary and influence followers to experience identification with

organizational goals. Transformational leaders also have been described as leading followers

to view their work as more important and self-congruent (Shamir, House, & Arthur, 1993).

Bono and Judge (2003) noted that transformational leaders influence followers through value

internalization and work engagement. In addition, Judge and Piccolo’s (2004) meta-analysis

demonstrated that follower engagement (ρ = .53) and follower job satisfaction (ρ = .58) were

strongly associated with transformational leadership.

Researchers have found engagement and job satisfaction to be positively associated with

authentic leadership (Neider & Schriesheim, 2011; Wong, Laschinger, & Cummings, 2010),

ethical leadership (Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012; Neubert, Carlson, Kacmar, Roberts, &

Chonko, 2009), and servant leadership (Chan & Mak, 2014; E. M. Hunter, Neubert, Perry,

Witt, Penney, & Weinberger, 2013). This may occur through authentic leadership’s personal

identification with followers, ethical leadership’s emphasis on fair treatment of followers,

and servant leadership’s focus on serving followers, thus promoting identification with the

leader that could contribute to employee work engagement and engender positive attitudes,

such as job satisfaction. In spite of these associations, because of the centrality of these out-

comes to transformational leadership, we do not expect the new forms of leadership to add

significant incremental validity above transformational leadership for engagement and job

satisfaction for both the theoretical and empirical reasons provided above.

Although the literature does not directly support a significant incremental effect upon the

previous discussed attitudinal measures, a different picture emerges for employee commit-

ment. Organizational commitment has been defined as “the relative strength of an individu-

al’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization” (Mowday & Steers,

1979: 226), and affective commitment refers to employees’ emotional bonds to their organi-

zations (Meyer & Allen, 1984). Researchers have found associations between transforma-

tional leadership and both organizational commitment (ρ = .43; DeGroot, Kiker, & Cross,

2000) and affective commitment (r = .33; Liao & Chuang, 2007). In spite of the positive

associations with transformational leadership, we expect that the three emerging leadership

forms will contribute incremental variance in explaining affective commitment and organi-

zational commitment. This expectation is based on empirical research supporting direct

effects of these three leadership forms on follower work attitudes, including organizational

commitment (cf. Leroy, Palanski, & Simons, 2012; Liden et al., 2008; Ng & Feldman, 2015),

Hoch et al. / Emerging Forms of Leadership 9

and the expectation that leaders who engage in these ethical forms of leadership will signifi-

cantly affect followers’ emotional attachments and connections to the organization. This is

consistent with authentic leadership’s emphasis on the positive moral perspective and fol-

lower development; ethical leadership’s emphasis upon the moral manager; individualized

consideration, fairness, and leader honesty; and servant leadership’s emphasis on the leader’s

serving followers.

Relational perceptions. The relational perceptions that allowed for analysis include trust

in supervisor and LMX. Dirks and Ferrin’s (2002) meta-analysis demonstrated that transfor-

mational leadership is strongly associated with trust (ρ = .72). Similarly, the meta-analysis

of Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer, and Ferris (2012) found transformational leadership

to be strongly associated with LMX (ρ = .73). Even though scholars have described the

emerging leadership forms as resulting in followers’ perceiving themselves to be in social

exchange relationships, which represents a central premise for LMX and trust (Avolio &

Gardner, 2005; Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006; Brown & Treviño, 2006), transformational leader-

ship’s strong association with both trust and LMX make it empirically unlikely that the new

leadership forms will explain much incremental variance. Thus, while the emerging forms of

leadership are described as creating social exchanges between leaders and followers, trans-

formational leadership creates the same social exchange.

Data and Method

Literature Search and Criteria for Inclusion

We conducted a systematic computer-based search of the literature associated with the

leadership forms included in this research (i.e., authentic leadership, ethical leadership, ser-

vant leadership, and transformational leadership) by using several methods, including

searches of the ABI-Inform, Dissertation Abstracts, PsycINFO, ISI Web of Knowledge, and

Google Scholar databases for dissertations and articles that included the leadership behaviors

of interest. To be as inclusive as possible, we conducted a broad search using each of the

forms as keywords. For authentic leadership, we included search terms such as authentic

leadership, authentic leader, authenticity, and authentic behavior; for ethical leadership, we

included ethical leadership, ethical leader, ethical integrity, ethical identity, ethical man-

ager, moral manager, ethical climate, and ethical context. For servant leadership, we

included servant leadership, servant leader, servant organization, and servant behavior. For

transformational leadership, we used terms such as transformational leadership, charismatic

leadership, and charisma. Additionally, we conducted a manual search for “in press” articles

in leading management journals and contacted authors who are active in the area. Data col-

lection included studies up to November 2015.

Inclusion Criteria

We used several decision rules regarding which studies would be included in the analyses.

First, studies had to be empirical and use working employees as the sample. Thus, we omitted

the few lab studies that used nonworking student samples and did not include work-related

and the expectation that leaders who engage in these ethical forms of leadership will signifi-

cantly affect followers’ emotional attachments and connections to the organization. This is

consistent with authentic leadership’s emphasis on the positive moral perspective and fol-

lower development; ethical leadership’s emphasis upon the moral manager; individualized

consideration, fairness, and leader honesty; and servant leadership’s emphasis on the leader’s

serving followers.

Relational perceptions. The relational perceptions that allowed for analysis include trust

in supervisor and LMX. Dirks and Ferrin’s (2002) meta-analysis demonstrated that transfor-

mational leadership is strongly associated with trust (ρ = .72). Similarly, the meta-analysis

of Dulebohn, Bommer, Liden, Brouer, and Ferris (2012) found transformational leadership

to be strongly associated with LMX (ρ = .73). Even though scholars have described the

emerging leadership forms as resulting in followers’ perceiving themselves to be in social

exchange relationships, which represents a central premise for LMX and trust (Avolio &

Gardner, 2005; Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006; Brown & Treviño, 2006), transformational leader-

ship’s strong association with both trust and LMX make it empirically unlikely that the new

leadership forms will explain much incremental variance. Thus, while the emerging forms of

leadership are described as creating social exchanges between leaders and followers, trans-

formational leadership creates the same social exchange.

Data and Method

Literature Search and Criteria for Inclusion

We conducted a systematic computer-based search of the literature associated with the

leadership forms included in this research (i.e., authentic leadership, ethical leadership, ser-

vant leadership, and transformational leadership) by using several methods, including

searches of the ABI-Inform, Dissertation Abstracts, PsycINFO, ISI Web of Knowledge, and

Google Scholar databases for dissertations and articles that included the leadership behaviors

of interest. To be as inclusive as possible, we conducted a broad search using each of the

forms as keywords. For authentic leadership, we included search terms such as authentic

leadership, authentic leader, authenticity, and authentic behavior; for ethical leadership, we

included ethical leadership, ethical leader, ethical integrity, ethical identity, ethical man-

ager, moral manager, ethical climate, and ethical context. For servant leadership, we

included servant leadership, servant leader, servant organization, and servant behavior. For

transformational leadership, we used terms such as transformational leadership, charismatic

leadership, and charisma. Additionally, we conducted a manual search for “in press” articles

in leading management journals and contacted authors who are active in the area. Data col-

lection included studies up to November 2015.

Inclusion Criteria

We used several decision rules regarding which studies would be included in the analyses.

First, studies had to be empirical and use working employees as the sample. Thus, we omitted

the few lab studies that used nonworking student samples and did not include work-related

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

outcomes (two each for authentic and ethical leadership and five for transformational leader-

ship). Second, studies needed to report sample sizes along with correlations or statistical

results adequate to compute a correlation coefficient or effect size between the leadership

form and one or more correlates of interest. Third, we excluded studies that examined leader-

ship relationships only at the group level of analysis. In addition, studies had to be written in

English to be included in our analysis. Finally, we included only those studies that contrib-

uted one or more relationships to the analyses. This last criteria is important as it is possible

that a study met the four criteria described but did not contain one or more of the effects of

interest. This could happen if the study in question used a novel measure that other research-

ers have not used, which made it unsuitable for inclusion in a meta-analysis.

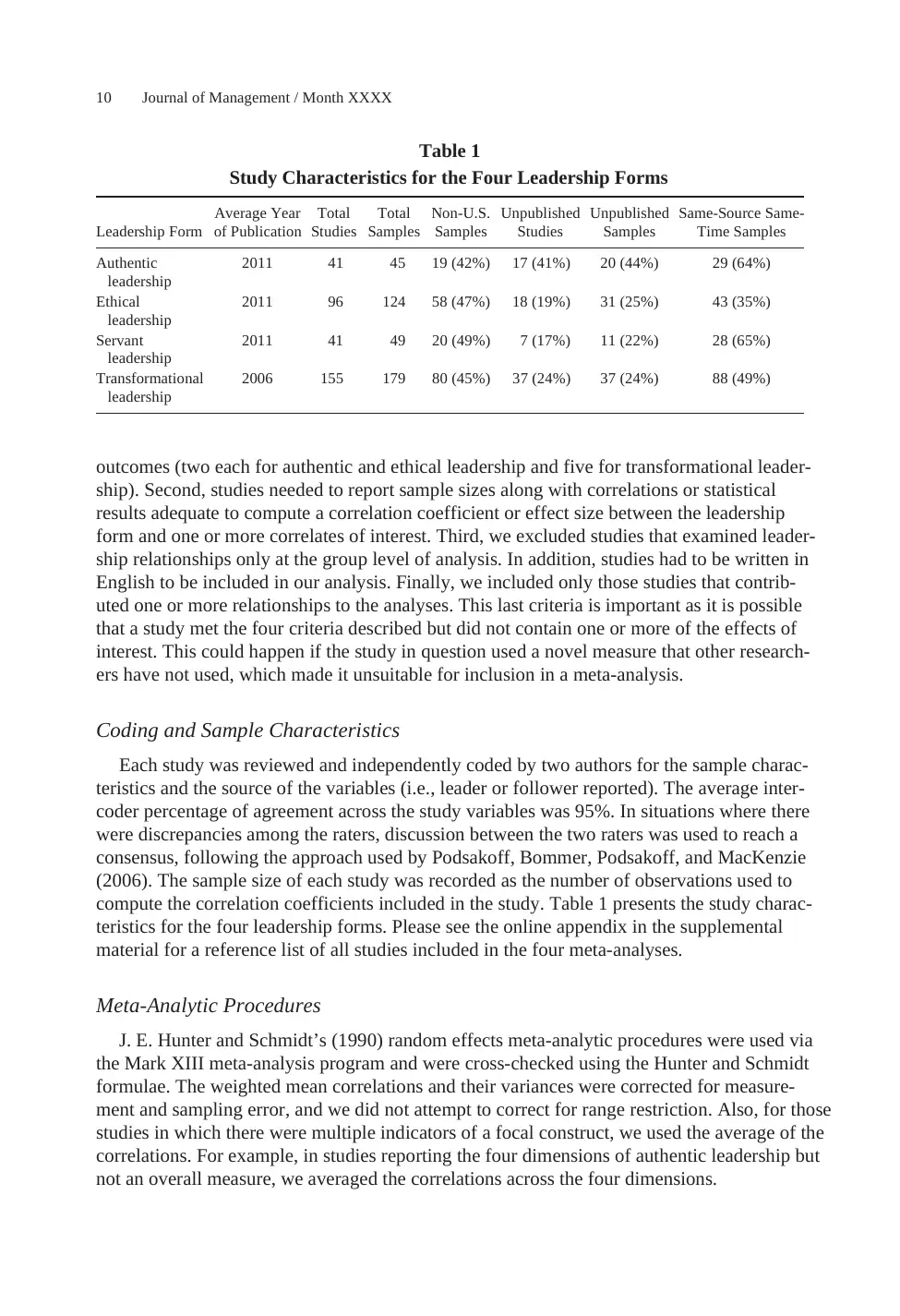

Coding and Sample Characteristics

Each study was reviewed and independently coded by two authors for the sample charac-

teristics and the source of the variables (i.e., leader or follower reported). The average inter-

coder percentage of agreement across the study variables was 95%. In situations where there

were discrepancies among the raters, discussion between the two raters was used to reach a

consensus, following the approach used by Podsakoff, Bommer, Podsakoff, and MacKenzie

(2006). The sample size of each study was recorded as the number of observations used to

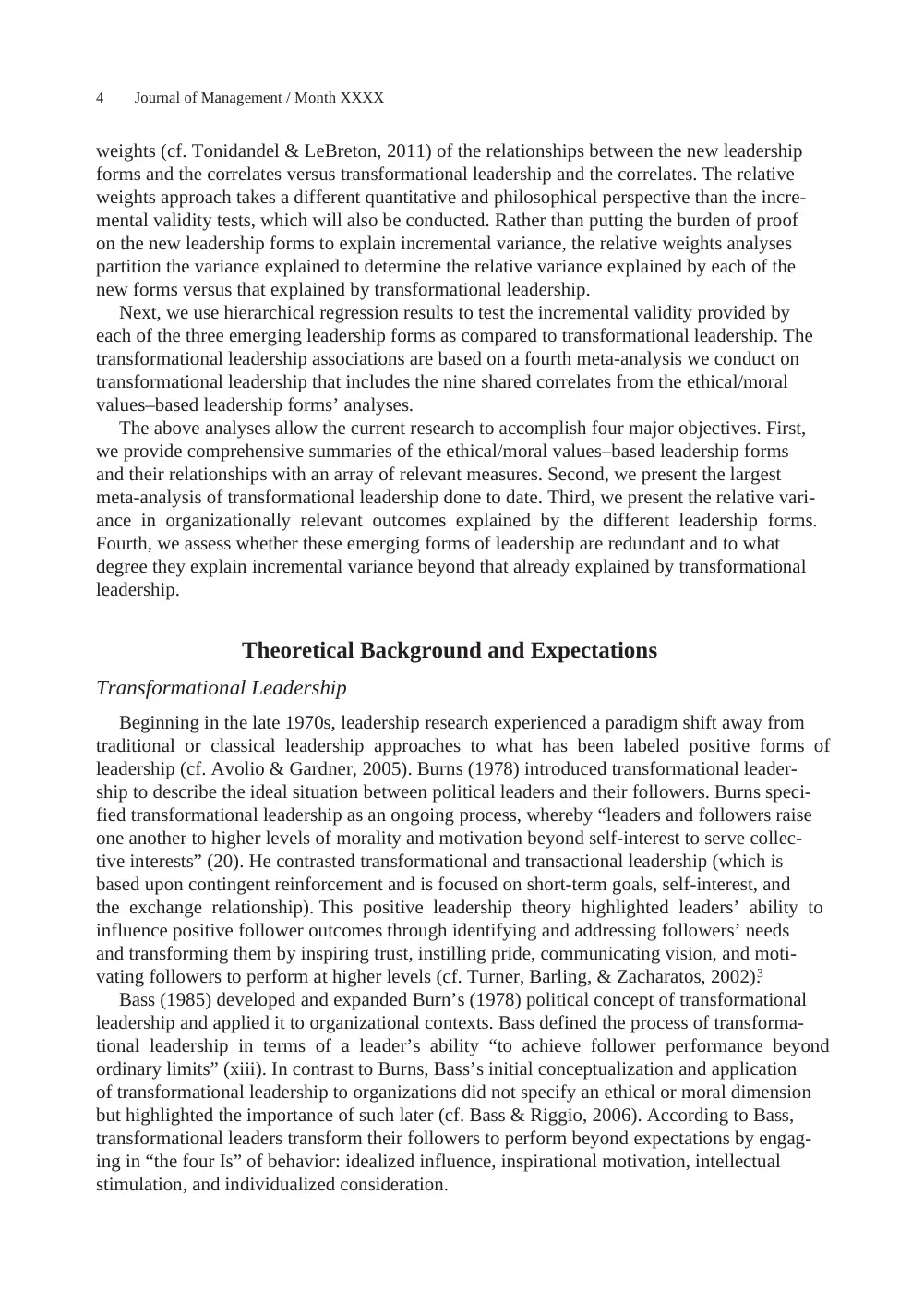

compute the correlation coefficients included in the study. Table 1 presents the study charac-

teristics for the four leadership forms. Please see the online appendix in the supplemental

material for a reference list of all studies included in the four meta-analyses.

Meta-Analytic Procedures

J. E. Hunter and Schmidt’s (1990) random effects meta-analytic procedures were used via

the Mark XIII meta-analysis program and were cross-checked using the Hunter and Schmidt

formulae. The weighted mean correlations and their variances were corrected for measure-

ment and sampling error, and we did not attempt to correct for range restriction. Also, for those

studies in which there were multiple indicators of a focal construct, we used the average of the

correlations. For example, in studies reporting the four dimensions of authentic leadership but

not an overall measure, we averaged the correlations across the four dimensions.

Table 1

Study Characteristics for the Four Leadership Forms

Leadership Form

Average Year

of Publication

Total

Studies

Total

Samples

Non-U.S.

Samples

Unpublished

Studies

Unpublished

Samples

Same-Source Same-

Time Samples

Authentic

leadership

2011 41 45 19 (42%) 17 (41%) 20 (44%) 29 (64%)

Ethical

leadership

2011 96 124 58 (47%) 18 (19%) 31 (25%) 43 (35%)

Servant

leadership

2011 41 49 20 (49%) 7 (17%) 11 (22%) 28 (65%)

Transformational

leadership

2006 155 179 80 (45%) 37 (24%) 37 (24%) 88 (49%)

outcomes (two each for authentic and ethical leadership and five for transformational leader-

ship). Second, studies needed to report sample sizes along with correlations or statistical

results adequate to compute a correlation coefficient or effect size between the leadership

form and one or more correlates of interest. Third, we excluded studies that examined leader-

ship relationships only at the group level of analysis. In addition, studies had to be written in

English to be included in our analysis. Finally, we included only those studies that contrib-

uted one or more relationships to the analyses. This last criteria is important as it is possible

that a study met the four criteria described but did not contain one or more of the effects of

interest. This could happen if the study in question used a novel measure that other research-

ers have not used, which made it unsuitable for inclusion in a meta-analysis.

Coding and Sample Characteristics

Each study was reviewed and independently coded by two authors for the sample charac-

teristics and the source of the variables (i.e., leader or follower reported). The average inter-

coder percentage of agreement across the study variables was 95%. In situations where there

were discrepancies among the raters, discussion between the two raters was used to reach a

consensus, following the approach used by Podsakoff, Bommer, Podsakoff, and MacKenzie

(2006). The sample size of each study was recorded as the number of observations used to

compute the correlation coefficients included in the study. Table 1 presents the study charac-

teristics for the four leadership forms. Please see the online appendix in the supplemental

material for a reference list of all studies included in the four meta-analyses.

Meta-Analytic Procedures

J. E. Hunter and Schmidt’s (1990) random effects meta-analytic procedures were used via

the Mark XIII meta-analysis program and were cross-checked using the Hunter and Schmidt

formulae. The weighted mean correlations and their variances were corrected for measure-

ment and sampling error, and we did not attempt to correct for range restriction. Also, for those

studies in which there were multiple indicators of a focal construct, we used the average of the

correlations. For example, in studies reporting the four dimensions of authentic leadership but

not an overall measure, we averaged the correlations across the four dimensions.

Table 1

Study Characteristics for the Four Leadership Forms

Leadership Form

Average Year

of Publication

Total

Studies

Total

Samples

Non-U.S.

Samples

Unpublished

Studies

Unpublished

Samples

Same-Source Same-

Time Samples

Authentic

leadership

2011 41 45 19 (42%) 17 (41%) 20 (44%) 29 (64%)

Ethical

leadership

2011 96 124 58 (47%) 18 (19%) 31 (25%) 43 (35%)

Servant

leadership

2011 41 49 20 (49%) 7 (17%) 11 (22%) 28 (65%)

Transformational

leadership

2006 155 179 80 (45%) 37 (24%) 37 (24%) 88 (49%)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Hoch et al. / Emerging Forms of Leadership 11

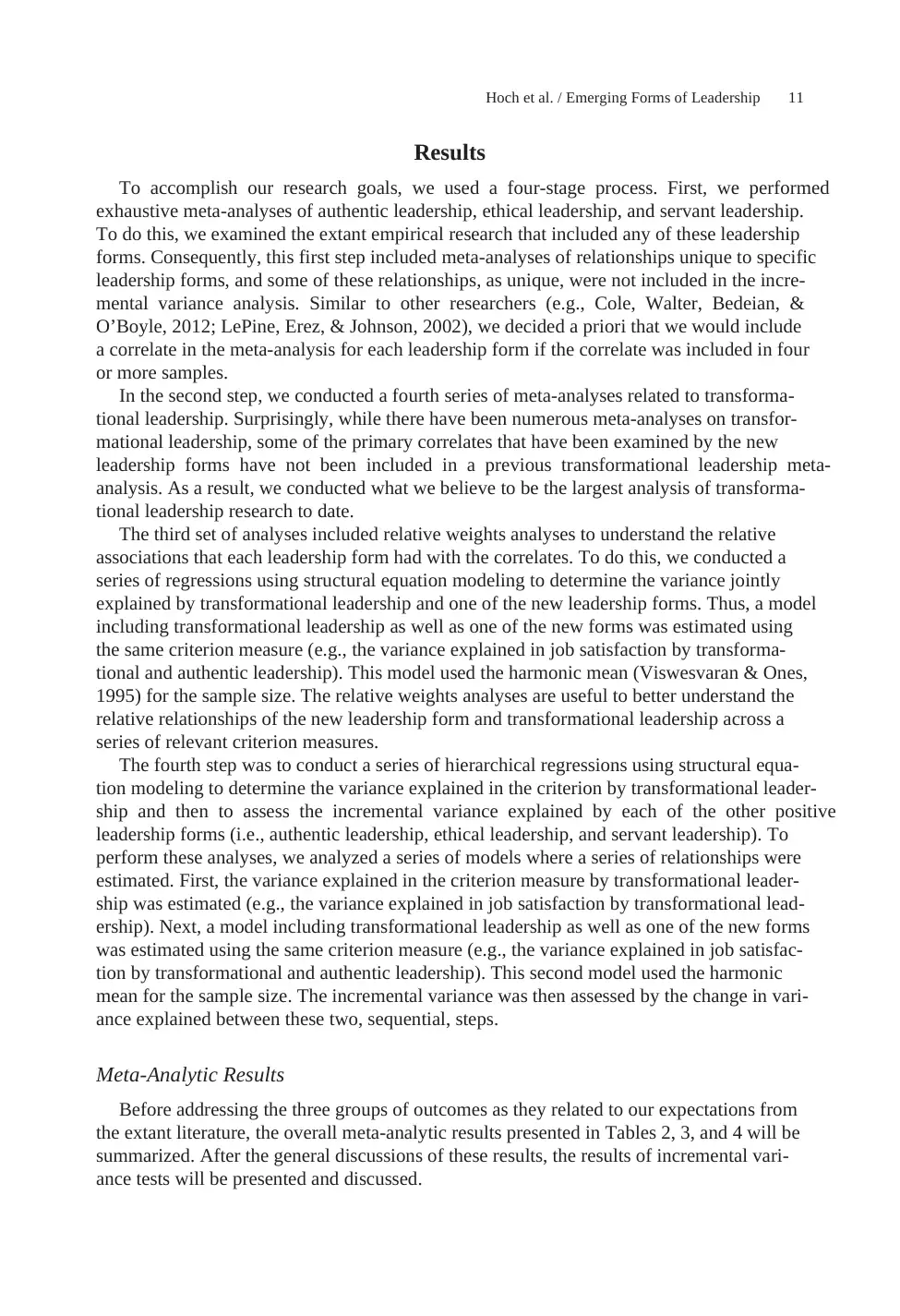

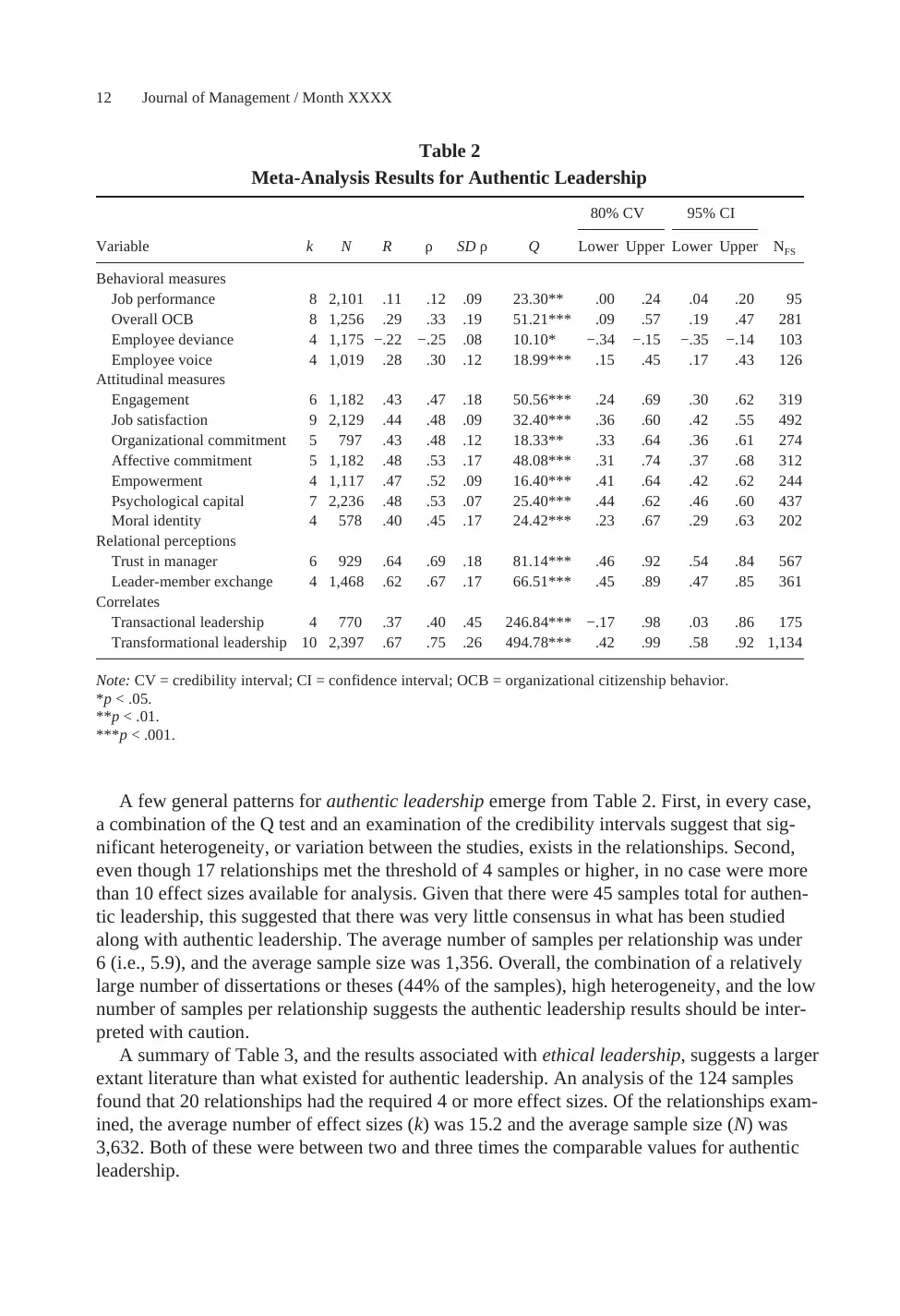

Results

To accomplish our research goals, we used a four-stage process. First, we performed

exhaustive meta-analyses of authentic leadership, ethical leadership, and servant leadership.

To do this, we examined the extant empirical research that included any of these leadership

forms. Consequently, this first step included meta-analyses of relationships unique to specific

leadership forms, and some of these relationships, as unique, were not included in the incre-

mental variance analysis. Similar to other researchers (e.g., Cole, Walter, Bedeian, &

O’Boyle, 2012; LePine, Erez, & Johnson, 2002), we decided a priori that we would include

a correlate in the meta-analysis for each leadership form if the correlate was included in four

or more samples.

In the second step, we conducted a fourth series of meta-analyses related to transforma-

tional leadership. Surprisingly, while there have been numerous meta-analyses on transfor-

mational leadership, some of the primary correlates that have been examined by the new

leadership forms have not been included in a previous transformational leadership meta-

analysis. As a result, we conducted what we believe to be the largest analysis of transforma-

tional leadership research to date.

The third set of analyses included relative weights analyses to understand the relative

associations that each leadership form had with the correlates. To do this, we conducted a

series of regressions using structural equation modeling to determine the variance jointly

explained by transformational leadership and one of the new leadership forms. Thus, a model

including transformational leadership as well as one of the new forms was estimated using

the same criterion measure (e.g., the variance explained in job satisfaction by transforma-

tional and authentic leadership). This model used the harmonic mean (Viswesvaran & Ones,

1995) for the sample size. The relative weights analyses are useful to better understand the

relative relationships of the new leadership form and transformational leadership across a

series of relevant criterion measures.

The fourth step was to conduct a series of hierarchical regressions using structural equa-

tion modeling to determine the variance explained in the criterion by transformational leader-

ship and then to assess the incremental variance explained by each of the other positive

leadership forms (i.e., authentic leadership, ethical leadership, and servant leadership). To

perform these analyses, we analyzed a series of models where a series of relationships were

estimated. First, the variance explained in the criterion measure by transformational leader-

ship was estimated (e.g., the variance explained in job satisfaction by transformational lead-

ership). Next, a model including transformational leadership as well as one of the new forms

was estimated using the same criterion measure (e.g., the variance explained in job satisfac-