Effect of Pain Relief on Diagnosis of Acute Abdominal Pain: A Report

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/23

|9

|2423

|15

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the effect of pain relief on the diagnosis and surgical treatment of acute abdominal pain, based on evidence-based practices. The study addresses the clinical question of whether pain relief before diagnosis impacts the surgical treatment of a 45-year-old male patient. The research methodology involves a PICO question format, searching databases like CINAHL, and prioritizing randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews. The critical appraisal focuses on a study by Manterola et al. (2011), highlighting the search methodology, the rigor of the review process, and the generalizability of the findings. The report also discusses barriers to the uptake of evidence-based practices, such as lack of time and skills, and proposes strategies for evaluation and implementation, including interviews, questionnaires, and creating a supportive organizational culture. The references include a range of sources supporting the evidence-based approach.

Running head: ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

Effect of pain relief for acute abdominal pain on diagnosis- evidence based practice

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author Note:

Effect of pain relief for acute abdominal pain on diagnosis- evidence based practice

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author Note:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

Section 1

Clinical question

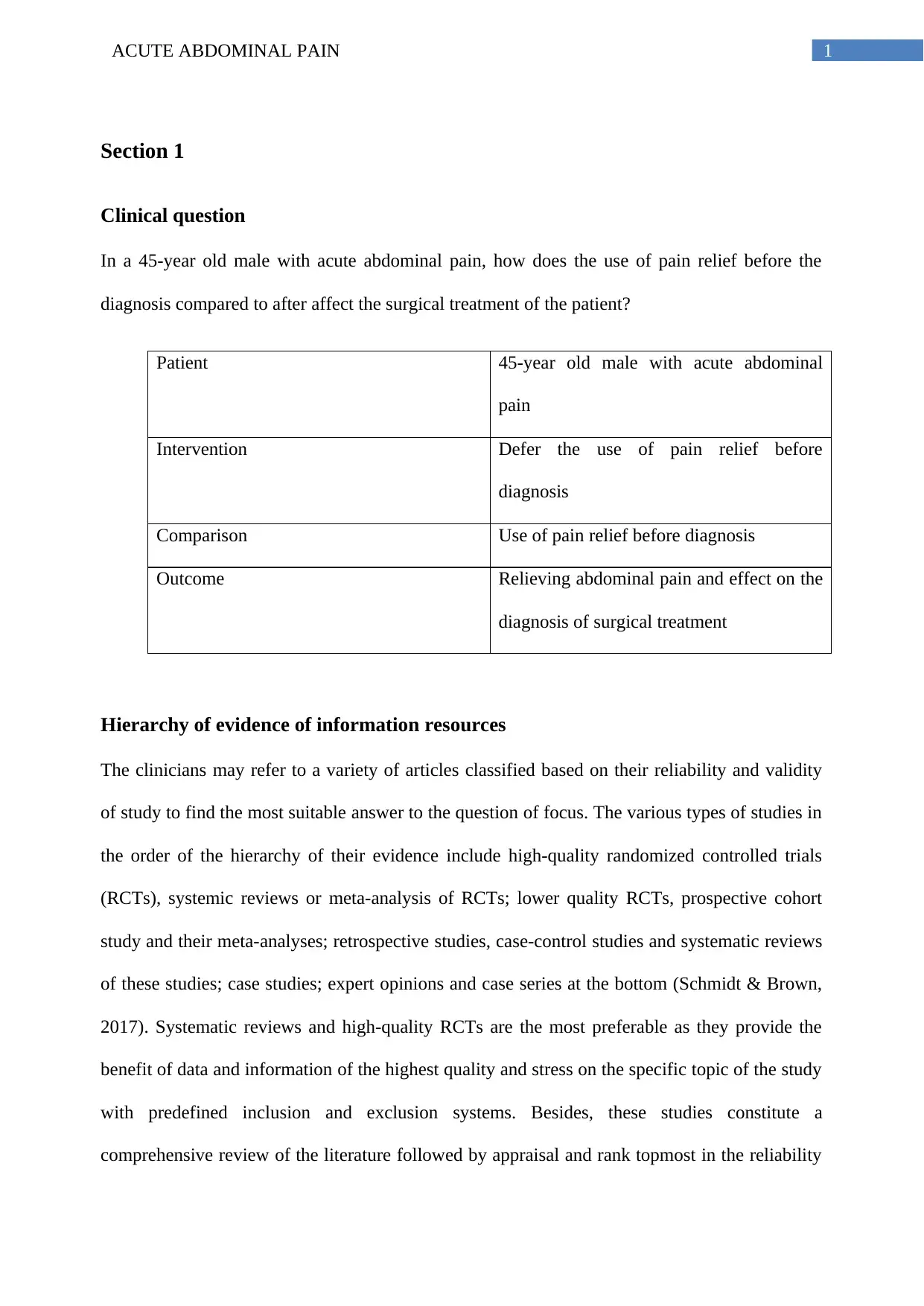

In a 45-year old male with acute abdominal pain, how does the use of pain relief before the

diagnosis compared to after affect the surgical treatment of the patient?

Patient 45-year old male with acute abdominal

pain

Intervention Defer the use of pain relief before

diagnosis

Comparison Use of pain relief before diagnosis

Outcome Relieving abdominal pain and effect on the

diagnosis of surgical treatment

Hierarchy of evidence of information resources

The clinicians may refer to a variety of articles classified based on their reliability and validity

of study to find the most suitable answer to the question of focus. The various types of studies in

the order of the hierarchy of their evidence include high-quality randomized controlled trials

(RCTs), systemic reviews or meta-analysis of RCTs; lower quality RCTs, prospective cohort

study and their meta-analyses; retrospective studies, case-control studies and systematic reviews

of these studies; case studies; expert opinions and case series at the bottom (Schmidt & Brown,

2017). Systematic reviews and high-quality RCTs are the most preferable as they provide the

benefit of data and information of the highest quality and stress on the specific topic of the study

with predefined inclusion and exclusion systems. Besides, these studies constitute a

comprehensive review of the literature followed by appraisal and rank topmost in the reliability

Section 1

Clinical question

In a 45-year old male with acute abdominal pain, how does the use of pain relief before the

diagnosis compared to after affect the surgical treatment of the patient?

Patient 45-year old male with acute abdominal

pain

Intervention Defer the use of pain relief before

diagnosis

Comparison Use of pain relief before diagnosis

Outcome Relieving abdominal pain and effect on the

diagnosis of surgical treatment

Hierarchy of evidence of information resources

The clinicians may refer to a variety of articles classified based on their reliability and validity

of study to find the most suitable answer to the question of focus. The various types of studies in

the order of the hierarchy of their evidence include high-quality randomized controlled trials

(RCTs), systemic reviews or meta-analysis of RCTs; lower quality RCTs, prospective cohort

study and their meta-analyses; retrospective studies, case-control studies and systematic reviews

of these studies; case studies; expert opinions and case series at the bottom (Schmidt & Brown,

2017). Systematic reviews and high-quality RCTs are the most preferable as they provide the

benefit of data and information of the highest quality and stress on the specific topic of the study

with predefined inclusion and exclusion systems. Besides, these studies constitute a

comprehensive review of the literature followed by appraisal and rank topmost in the reliability

2ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

scale. However, a significant drawback of using systematic reviews re that they are more

appropriate for quantitative studies and do not address the questions of qualitative studies well.

A significant disadvantage of using RTC studies is that their validities need numerous sites that

are often tough to manage. Although positioned after systematic reviews and RTCs, an

advantage of using prospective cohort studies is that they are designed such that the eligibility

criteria and the results of the assessment are standard. Also, they are less expensive than RTCs.

The disadvantage of cohort studies is that the data involved in these studies may often be linked

to a hidden cofactor. Next in the hierarchy, case controls have the benefit of allowing the

analysis of a variety of prognostic factors and identify correlations between them. However, the

disadvantage of using these studies is that it may involve unknown risk factors involved in the

study. Case studies, positioned below case controls, are active for studies involving prolonged

periods of latency and are relatively inexpensive. Nonetheless, the results of these studies cannot

be generalized to a broader population and frequently reflects the subjective opinions of the

researcher. Though places lower in the hierarchy, retrospective studies such as case reports and

case series provide information on a particular subgroup of the population under study and have

no comparison group. The disadvantage of using these studies is that they focus on a specific

setting or clinic and cannot be generalized to the vast majority of the population.

Search methodology

The selection of the research articles highly relevant to the PICO question under review will be

conducted by searching the medical database CINAHL. The primary aim of the search strategy

is to obtain articles and studies, preferable of the RCT design that addresses the effect of

administering pain relief before the diagnosis of a patient and gives relevant outcomes of the

analgesic on the diagnosis and surgical treatment of the patient. The set search terms and

keywords used include pain relief, the effect of pain relief on diagnosis, use of analgesic in

surgical treatment, the effect of analgesic on diagnosis outcome, diagnosis with and without pain

scale. However, a significant drawback of using systematic reviews re that they are more

appropriate for quantitative studies and do not address the questions of qualitative studies well.

A significant disadvantage of using RTC studies is that their validities need numerous sites that

are often tough to manage. Although positioned after systematic reviews and RTCs, an

advantage of using prospective cohort studies is that they are designed such that the eligibility

criteria and the results of the assessment are standard. Also, they are less expensive than RTCs.

The disadvantage of cohort studies is that the data involved in these studies may often be linked

to a hidden cofactor. Next in the hierarchy, case controls have the benefit of allowing the

analysis of a variety of prognostic factors and identify correlations between them. However, the

disadvantage of using these studies is that it may involve unknown risk factors involved in the

study. Case studies, positioned below case controls, are active for studies involving prolonged

periods of latency and are relatively inexpensive. Nonetheless, the results of these studies cannot

be generalized to a broader population and frequently reflects the subjective opinions of the

researcher. Though places lower in the hierarchy, retrospective studies such as case reports and

case series provide information on a particular subgroup of the population under study and have

no comparison group. The disadvantage of using these studies is that they focus on a specific

setting or clinic and cannot be generalized to the vast majority of the population.

Search methodology

The selection of the research articles highly relevant to the PICO question under review will be

conducted by searching the medical database CINAHL. The primary aim of the search strategy

is to obtain articles and studies, preferable of the RCT design that addresses the effect of

administering pain relief before the diagnosis of a patient and gives relevant outcomes of the

analgesic on the diagnosis and surgical treatment of the patient. The set search terms and

keywords used include pain relief, the effect of pain relief on diagnosis, use of analgesic in

surgical treatment, the effect of analgesic on diagnosis outcome, diagnosis with and without pain

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

relief, the outcome of pain relief on surgery and pain relief and diagnosis result in an adult male.

Boolean operators will be accompanied by these sets of search terms to increase the accuracy of

the results and filter them for easier identification of relevant articles. The primary rationale

behind this is to increase the count of results and screen the most appropriate ones from the less

relevant articles. Moreover, this method of search strategy allows the scope to gather an

overview of the available literature on this topic and determine the inclusion or exclusion of

keywords to enhance the pertinence of the search (Robb & Shellenbarger, 2014). The search can

be further limited by using different inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reason behind this is

that it enables screening of the articles for further precision and developing an accurate answer

can be completed. Only the articles that followed randomized control trials, systematic reviews

and prospective cohort studies were screened for further evaluation. Additionally, it is crucial to

limit the search specifically to the adult male population to avoid results related to pregnancies.

Domain/type of the question

The most suitable technique for this evidence-based study is the PICO type of question. It stands

for Population/Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome. It emphasizes the significance

of the study by a well-structured question under review and helps a precise search of the

evidence (Echevarria & Walker, 2014).

Preferred type of study

Randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies would be the most suitable to obtain appropriate

results to the question under review as these studies involve randomization and are beneficial in

controlling bias (Deaton & Cartwright, 2018). It would provide a clear picture of the effects of

the use of pain relief on diagnosis and surgical treatment by involving a sample of a large,

generalized population. Also, the randomness of the study eliminates any sort of selection bias

in choosing whether the pain relief should be administered or not. Apart from RCTs, cohort

relief, the outcome of pain relief on surgery and pain relief and diagnosis result in an adult male.

Boolean operators will be accompanied by these sets of search terms to increase the accuracy of

the results and filter them for easier identification of relevant articles. The primary rationale

behind this is to increase the count of results and screen the most appropriate ones from the less

relevant articles. Moreover, this method of search strategy allows the scope to gather an

overview of the available literature on this topic and determine the inclusion or exclusion of

keywords to enhance the pertinence of the search (Robb & Shellenbarger, 2014). The search can

be further limited by using different inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reason behind this is

that it enables screening of the articles for further precision and developing an accurate answer

can be completed. Only the articles that followed randomized control trials, systematic reviews

and prospective cohort studies were screened for further evaluation. Additionally, it is crucial to

limit the search specifically to the adult male population to avoid results related to pregnancies.

Domain/type of the question

The most suitable technique for this evidence-based study is the PICO type of question. It stands

for Population/Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome. It emphasizes the significance

of the study by a well-structured question under review and helps a precise search of the

evidence (Echevarria & Walker, 2014).

Preferred type of study

Randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies would be the most suitable to obtain appropriate

results to the question under review as these studies involve randomization and are beneficial in

controlling bias (Deaton & Cartwright, 2018). It would provide a clear picture of the effects of

the use of pain relief on diagnosis and surgical treatment by involving a sample of a large,

generalized population. Also, the randomness of the study eliminates any sort of selection bias

in choosing whether the pain relief should be administered or not. Apart from RCTs, cohort

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

studies, case series and case control studies might also be useful to find the effects of

administering pain relief to the patient.

Section 2

Critical appraisal

As per the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, the study conducted by Manterola et al. (2011),

addresses an explicitly focused question of whether the use of opioid analgesics affects the

diagnostic outcome of patients with acute abdominal pain. The review is focused on the question

as the population under consideration consists of adults, the intervention considered is the use of

analgesic on acute abdominal pain and the outcome to be studied is the effect of the pain relief

on diagnostic results. Thus, the review article is clearly in line with the question under focus.

The authors searched for the most relevant papers using appropriate search methodology and

reliable articles. This is evident as all the selected study designs followed randomized double-

blinded controlled trials by two independent reviewers (Haddaway et al., 2015). Besides, the

selected articles were highly relevant and reliable sources for the study. They were all selected

from recognized databases such as CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE. They were carefully

referenced and followed up in the reference list. It only included published studies. An essential

consideration of the study is that the reviewers rigorously assessed the articles. Two independent

reviewers were involved in the process who sorted the relevant articles based on the titles and

abstracts. Articles selected by at least one of the reviewers was required for the full-text review

of the article. The results of the different reviews studied were combined effectively to frame a

common conclusion (Brannen, 2017). The papers under review presented similar overall results

and the variations in the papers were mentioned. For instance, the majority of the papers

included the effect of visual analog scale (VAS) which resulted in similar outcomes and can be

combined reasonably. The overall results of the review are clearly stated and expressed

studies, case series and case control studies might also be useful to find the effects of

administering pain relief to the patient.

Section 2

Critical appraisal

As per the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, the study conducted by Manterola et al. (2011),

addresses an explicitly focused question of whether the use of opioid analgesics affects the

diagnostic outcome of patients with acute abdominal pain. The review is focused on the question

as the population under consideration consists of adults, the intervention considered is the use of

analgesic on acute abdominal pain and the outcome to be studied is the effect of the pain relief

on diagnostic results. Thus, the review article is clearly in line with the question under focus.

The authors searched for the most relevant papers using appropriate search methodology and

reliable articles. This is evident as all the selected study designs followed randomized double-

blinded controlled trials by two independent reviewers (Haddaway et al., 2015). Besides, the

selected articles were highly relevant and reliable sources for the study. They were all selected

from recognized databases such as CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE. They were carefully

referenced and followed up in the reference list. It only included published studies. An essential

consideration of the study is that the reviewers rigorously assessed the articles. Two independent

reviewers were involved in the process who sorted the relevant articles based on the titles and

abstracts. Articles selected by at least one of the reviewers was required for the full-text review

of the article. The results of the different reviews studied were combined effectively to frame a

common conclusion (Brannen, 2017). The papers under review presented similar overall results

and the variations in the papers were mentioned. For instance, the majority of the papers

included the effect of visual analog scale (VAS) which resulted in similar outcomes and can be

combined reasonably. The overall results of the review are clearly stated and expressed

5ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

statistically, as well. The result depicted that the use of opioid analgesics had caused no error in

the diagnosis of the patients. Also, the results are precisely stated and addresses the initial

question of focus. Also, as the population under study did not have restrictions on any gender

and considered a variety of settings, it can be generalized to the local population. Moreover, the

total population size was significant including 922 patients, which makes it generally acceptable

(Boddy, 2016). Lastly, the study discussed all the relevant outcomes of the use of opioid

analgesic including associated morbidity, changes in the intensity of the pain, comfort level and

hospital stay among others.

Section 3

Barriers to the uptake of evidence-based practices (EBP)

The uptake of evidence-based practice is associated with multiple barriers. The first barrier to its

uptake it that though allied healthcare professionals reflect a positive response and attitude

towards evidence-based practices, they do not frequently participate in it. These practices lack

full adoption by healthcare clinicians (Aarons et al., 2014). Another critical barrier includes

difficulty in implementing evidence-based practices in the clinical settings and is commonly

associated with lack of time. Inadequate time is the reason behind the trouble in implementing

these practices practically (Harding et al., 2014). The third barrier to the uptake of evidence-

based practices includes a lack of sufficient skills or knowledge required to access the

information. Some studies depict that many clinicians do not possess adequate expertise in

accessing information from evidence-based practices.

Strategies to evaluate the outcomes of successful uptake of EBP

The uptake of evidence based practice can be evaluated by various methods to systematically

assess the potential barriers to its uptake and find suitable strategies for its promotion. The first

strategy for practical evaluation includes face-to-face interviews with the clinicians to obtain

statistically, as well. The result depicted that the use of opioid analgesics had caused no error in

the diagnosis of the patients. Also, the results are precisely stated and addresses the initial

question of focus. Also, as the population under study did not have restrictions on any gender

and considered a variety of settings, it can be generalized to the local population. Moreover, the

total population size was significant including 922 patients, which makes it generally acceptable

(Boddy, 2016). Lastly, the study discussed all the relevant outcomes of the use of opioid

analgesic including associated morbidity, changes in the intensity of the pain, comfort level and

hospital stay among others.

Section 3

Barriers to the uptake of evidence-based practices (EBP)

The uptake of evidence-based practice is associated with multiple barriers. The first barrier to its

uptake it that though allied healthcare professionals reflect a positive response and attitude

towards evidence-based practices, they do not frequently participate in it. These practices lack

full adoption by healthcare clinicians (Aarons et al., 2014). Another critical barrier includes

difficulty in implementing evidence-based practices in the clinical settings and is commonly

associated with lack of time. Inadequate time is the reason behind the trouble in implementing

these practices practically (Harding et al., 2014). The third barrier to the uptake of evidence-

based practices includes a lack of sufficient skills or knowledge required to access the

information. Some studies depict that many clinicians do not possess adequate expertise in

accessing information from evidence-based practices.

Strategies to evaluate the outcomes of successful uptake of EBP

The uptake of evidence based practice can be evaluated by various methods to systematically

assess the potential barriers to its uptake and find suitable strategies for its promotion. The first

strategy for practical evaluation includes face-to-face interviews with the clinicians to obtain

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

qualitative and descriptive responses and get a more extensive overview of the barrier faced. The

second method of evaluation includes questionnaires and surveys. It provides a quantitative

analysis of the extent of the different barriers in the successful implementation of evidence-

based practices. However, it does not incorporate personal opinions as in the case of interviews.

The third strategy for successful evaluation includes focus groups that provide detailed

responses from a considerable sample size consisting of clinicians (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber,

2014).

Implementation strategies to promote EBP

The evidence-based practice serves as a problem-solving method by incorporating the most

relevant available clinical expertise and scientific evidence. Thus, it is vital to promote its uptake

by overcoming the barriers in its implementation. One such strategy includes redefining the role

of nurses in training them in inculcating these practices. This is justified as it removes the barrier

of adequate expertise (White, 2016). The second strategy includes investing additional funds and

time into the process of evidence-based practices. This addresses the barrier of insufficient

money and time for the uptake of evidence-based practices. Thirdly, it is essential to create a

culture within the organization that fosters evidence-based practices. This strategy encourages

the workforce to apply these practices in their professional habits (Sharplin et al., 2019).

qualitative and descriptive responses and get a more extensive overview of the barrier faced. The

second method of evaluation includes questionnaires and surveys. It provides a quantitative

analysis of the extent of the different barriers in the successful implementation of evidence-

based practices. However, it does not incorporate personal opinions as in the case of interviews.

The third strategy for successful evaluation includes focus groups that provide detailed

responses from a considerable sample size consisting of clinicians (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber,

2014).

Implementation strategies to promote EBP

The evidence-based practice serves as a problem-solving method by incorporating the most

relevant available clinical expertise and scientific evidence. Thus, it is vital to promote its uptake

by overcoming the barriers in its implementation. One such strategy includes redefining the role

of nurses in training them in inculcating these practices. This is justified as it removes the barrier

of adequate expertise (White, 2016). The second strategy includes investing additional funds and

time into the process of evidence-based practices. This addresses the barrier of insufficient

money and time for the uptake of evidence-based practices. Thirdly, it is essential to create a

culture within the organization that fosters evidence-based practices. This strategy encourages

the workforce to apply these practices in their professional habits (Sharplin et al., 2019).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

References

Aarons, G.A., Ehrhart, M.G., Farahnak, L.R. & Sklar, M., (2014). Aligning leadership across

systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice

implementation. Annual review of public health, 35.

Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An

International Journal.

Brannen, J. (2017). Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: an overview. In Mixing

methods: Qualitative and quantitative research (pp. 3-37). Routledge.

Deaton, A., & Cartwright, N. (2018). Understanding and misunderstanding randomized

controlled trials. Social Science & Medicine, 210, 2-21.

Echevarria, I. M., & Walker, S. (2014). To make your case, start with a PICOT

question. Nursing2020, 44(2), 18-19.

Haddaway, N. R., Woodcock, P., Macura, B., & Collins, A. (2015). Making literature reviews

more reliable through application of lessons from systematic reviews. Conservation

Biology, 29(6), 1596-1605.

Harding, K. E., Porter, J., Horne‐Thompson, A., Donley, E., & Taylor, N. F. (2014). Not enough

time or a low priority? Barriers to evidence‐based practice for allied health

clinicians. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 34(4), 224-231.

LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2014). Nursing research-e-book: methods and critical

appraisal for evidence-based practice. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Robb, M., & Shellenbarger, T. (2014). Strategies for searching and managing evidence-based

practice resources. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 45(10), 461-466.

References

Aarons, G.A., Ehrhart, M.G., Farahnak, L.R. & Sklar, M., (2014). Aligning leadership across

systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice

implementation. Annual review of public health, 35.

Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research: An

International Journal.

Brannen, J. (2017). Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: an overview. In Mixing

methods: Qualitative and quantitative research (pp. 3-37). Routledge.

Deaton, A., & Cartwright, N. (2018). Understanding and misunderstanding randomized

controlled trials. Social Science & Medicine, 210, 2-21.

Echevarria, I. M., & Walker, S. (2014). To make your case, start with a PICOT

question. Nursing2020, 44(2), 18-19.

Haddaway, N. R., Woodcock, P., Macura, B., & Collins, A. (2015). Making literature reviews

more reliable through application of lessons from systematic reviews. Conservation

Biology, 29(6), 1596-1605.

Harding, K. E., Porter, J., Horne‐Thompson, A., Donley, E., & Taylor, N. F. (2014). Not enough

time or a low priority? Barriers to evidence‐based practice for allied health

clinicians. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 34(4), 224-231.

LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2014). Nursing research-e-book: methods and critical

appraisal for evidence-based practice. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Robb, M., & Shellenbarger, T. (2014). Strategies for searching and managing evidence-based

practice resources. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 45(10), 461-466.

8ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

Schmidt, N. A., & Brown, J. M. (2017). Evidence-based practice for nurses: Appraisal and

application of research. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Sharplin, G., Adelson, P., Kennedy, K., Williams, N., Hewlett, R., Wood, J., ... & Eckert, M.

(2019, December). Establishing and Sustaining a Culture of Evidence-Based Practice:

An Evaluation of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing the Best Practice Spotlight

Organization Program in the Australian Healthcare Context. In Healthcare (Vol. 7, No.

4, p. 142). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

White, K., (2016). Evidence-based practice. Translation of Evidence into Nursing and Health

Care. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Schmidt, N. A., & Brown, J. M. (2017). Evidence-based practice for nurses: Appraisal and

application of research. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Sharplin, G., Adelson, P., Kennedy, K., Williams, N., Hewlett, R., Wood, J., ... & Eckert, M.

(2019, December). Establishing and Sustaining a Culture of Evidence-Based Practice:

An Evaluation of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing the Best Practice Spotlight

Organization Program in the Australian Healthcare Context. In Healthcare (Vol. 7, No.

4, p. 142). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

White, K., (2016). Evidence-based practice. Translation of Evidence into Nursing and Health

Care. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.