Assessment of a Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility: A Detailed Report

VerifiedAdded on 2020/04/01

|36

|11036

|119

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an in-depth assessment of a mobile e-waste processing facility, focusing on the methodologies used for recycling and metal recovery from electronic waste. The study covers various aspects, including the processing of e-waste, the recovery of valuable metals like gold, platinum, silver, and palladium, as well as the responsible management of toxic substances such as mercury, lead, and beryllium. The report details the e-waste processing stages, from collection and dismantling to end processing, and the use of techniques like pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy. It includes preliminary designs for the recycling process, extractive metallurgy, sorting, and dismantling processes. Furthermore, it examines the design of integrated mobile recycling plants, with a focus on the container designs, and the analysis and results obtained from the evaluation. The report also emphasizes the importance of urban mining and the economic and environmental benefits of recycling electronic waste, providing a comprehensive overview of the entire e-waste recycling process.

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 1

ASSESSMENT OF MOBILE E-WASTE PROCESSING FACILITY

A Report Paper on Mobile E-Waste By

Student’s Name

Name of the Professor

Institutional Affiliation

City/State

Year/Month/Day

ASSESSMENT OF MOBILE E-WASTE PROCESSING FACILITY

A Report Paper on Mobile E-Waste By

Student’s Name

Name of the Professor

Institutional Affiliation

City/State

Year/Month/Day

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 2

TABLE OF CONTENT

Item Page

METHODOLOGY………………………………………………………….…….……3

Recovering metals from e-wastes………………………………………………6

EVALUATION…………………………………………………………………...……6

Preliminary design for the recycling process……………………………………..……8

Extractive metallurgy…………………………………………………………………..8

Sorting and dismantling………………………………………………………………..10

End processing…………………………………………………………………………11

Hydrometallurgical processing…………………………….………………………..…12

Detailed designs for the integrated mobile recycling plants………………………......16

Container 1 Design……………………………………………………………….…...17

Container 2 Design………………………………………….………………….….…18

Container 3 Design………………………………………….………………….….…19

Container 4 Design………………………………………….……………….………20

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS………………………………………………………..21

CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………………24

Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………28

TABLE OF CONTENT

Item Page

METHODOLOGY………………………………………………………….…….……3

Recovering metals from e-wastes………………………………………………6

EVALUATION…………………………………………………………………...……6

Preliminary design for the recycling process……………………………………..……8

Extractive metallurgy…………………………………………………………………..8

Sorting and dismantling………………………………………………………………..10

End processing…………………………………………………………………………11

Hydrometallurgical processing…………………………….………………………..…12

Detailed designs for the integrated mobile recycling plants………………………......16

Container 1 Design……………………………………………………………….…...17

Container 2 Design………………………………………….………………….….…18

Container 3 Design………………………………………….………………….….…19

Container 4 Design………………………………………….……………….………20

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS………………………………………………………..21

CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………………24

Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………28

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 3

METHODOLOGY

E-waste contain valuable metals like gold, platinum, silver and palladium also toxic substance

such as mercury, lead, and beryllium. The management of responsible end life of electronic

waste management is to get constituents that are valuable and manage toxic and hazardous

components properly. The end life management of electronic waste comprises of reprocess of

useful electronics, repair and refurbishment and recovery of electronic components, disposal and

recycling electronic wastes. Recycling of electronics enable the recovery of valuable metals and

also reduces the impact of environmental related with the manufacturing of electronics from raw

materials and ensures appropriate handling of hazardous and toxic components.

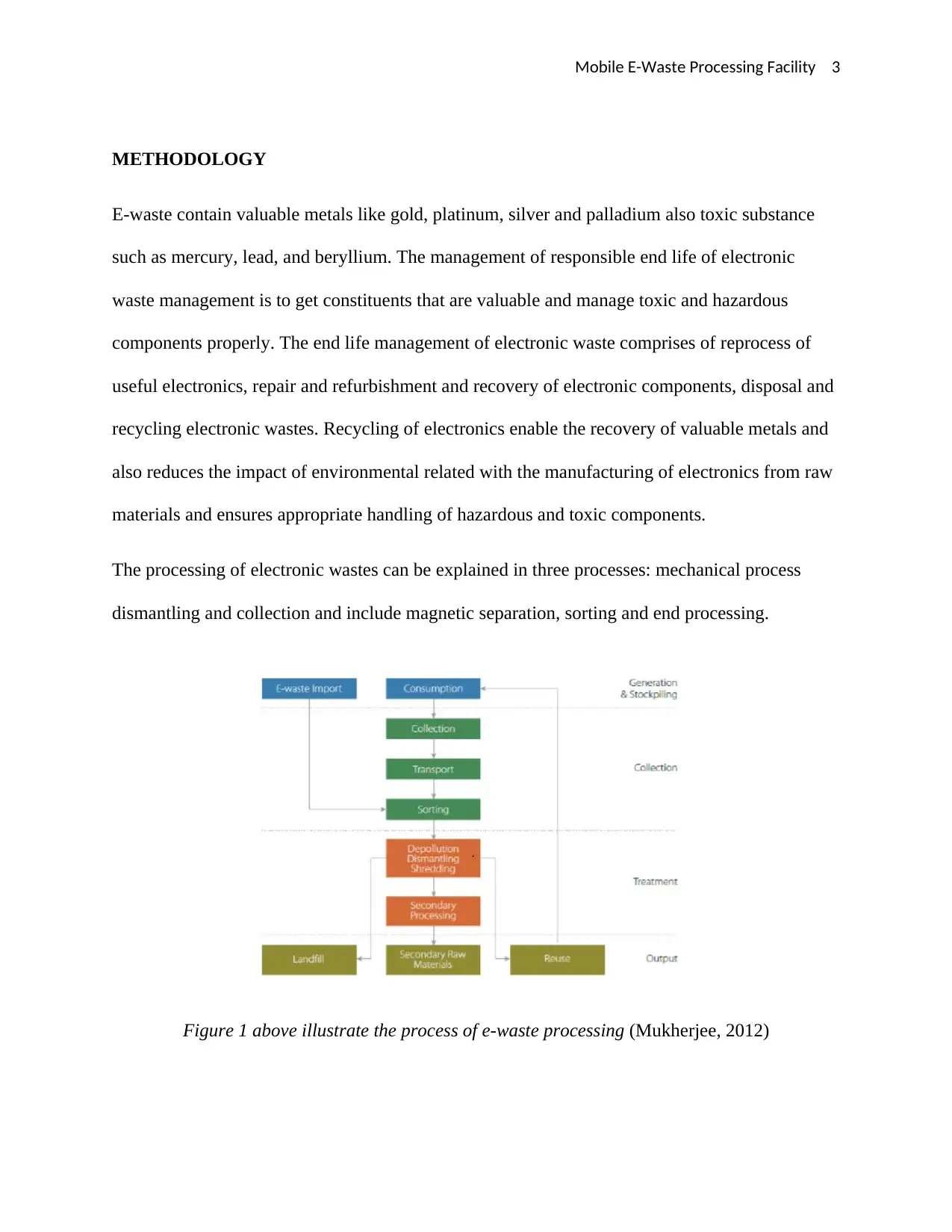

The processing of electronic wastes can be explained in three processes: mechanical process

dismantling and collection and include magnetic separation, sorting and end processing.

Figure 1 above illustrate the process of e-waste processing (Mukherjee, 2012)

METHODOLOGY

E-waste contain valuable metals like gold, platinum, silver and palladium also toxic substance

such as mercury, lead, and beryllium. The management of responsible end life of electronic

waste management is to get constituents that are valuable and manage toxic and hazardous

components properly. The end life management of electronic waste comprises of reprocess of

useful electronics, repair and refurbishment and recovery of electronic components, disposal and

recycling electronic wastes. Recycling of electronics enable the recovery of valuable metals and

also reduces the impact of environmental related with the manufacturing of electronics from raw

materials and ensures appropriate handling of hazardous and toxic components.

The processing of electronic wastes can be explained in three processes: mechanical process

dismantling and collection and include magnetic separation, sorting and end processing.

Figure 1 above illustrate the process of e-waste processing (Mukherjee, 2012)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 4

Collection: assortment usually occur at the national or regional level and is attained through the

programs supported by the manufacturers and retailers of electronics, collection drop off centre

of municipal and collection program of nonprofit and for profit. There are many dissimilar

objects which gather electronic scrap for recycling, alternating from municipal government to

local government to big corporations of managing wastes (Bhasin, 2014).

Dismantling sorting and mechanical processing: dismantling, sorting and pre-processing occur

at the national or local level, and its end objective is to separate streams devices into materials

steam, primarily glass, plastics and metals for end processing. The objective of this stage is to

advance the content of treasured materials and safely eradicate and dispose of hazardous. It

should be known that optimal level of pre-processing is dictated by the quality of requirements

of freed for the end processing. Excessive preprocessing adds cost and may lead to important

losses of the precious metals. Therefore the optimal level of preprocessing needs to be reached.

Figure 2 shows the process of dismantling and sorting e wastes (Milligan, 2011)

Once the constituents are separated, the elements of ferrous are transferred to plants for

repossession of iron, a fraction of aluminium are led to smelters of aluminium and copper alloys

Collection: assortment usually occur at the national or regional level and is attained through the

programs supported by the manufacturers and retailers of electronics, collection drop off centre

of municipal and collection program of nonprofit and for profit. There are many dissimilar

objects which gather electronic scrap for recycling, alternating from municipal government to

local government to big corporations of managing wastes (Bhasin, 2014).

Dismantling sorting and mechanical processing: dismantling, sorting and pre-processing occur

at the national or local level, and its end objective is to separate streams devices into materials

steam, primarily glass, plastics and metals for end processing. The objective of this stage is to

advance the content of treasured materials and safely eradicate and dispose of hazardous. It

should be known that optimal level of pre-processing is dictated by the quality of requirements

of freed for the end processing. Excessive preprocessing adds cost and may lead to important

losses of the precious metals. Therefore the optimal level of preprocessing needs to be reached.

Figure 2 shows the process of dismantling and sorting e wastes (Milligan, 2011)

Once the constituents are separated, the elements of ferrous are transferred to plants for

repossession of iron, a fraction of aluminium are led to smelters of aluminium and copper alloys

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 5

are directed to an smelter that is integrated where the retrieval of precious metals, non-ferrous

metals and copper takes place.

End processing: end processing occurs at the global level and is determined by the steam

materials. The aim of this end processing is to recover the constituents that are valuable and

remove the impurities. Assaying and sampling are important to determine the content of valuable

metals and the composition of the electronic waste stream and ensure that the process that is

optimum is employed to recover the precious metals. Pyrometallurgical is the process employed

to recover the valuable metals but hydrometallurgical and bio metallurgical can also be used

(Bergman, 2017).

The collection, preprocessing, dismantling and repossession from less compound of electronic

wastes such as copper, ferrous, and aluminium normally occurs at national or local level. The

end processing is a more complex component of electronic wastes like batteries, circuit board,

and cell phones mostly take place in global context and occur in integrated smelters of copper.

These smelters are non-ferrous metallurgy extractive to separate segments that are complex into

their basic metals and these companies are very expensive to construct hence it is not economical

to build them in all counties (Santillo, 2010).

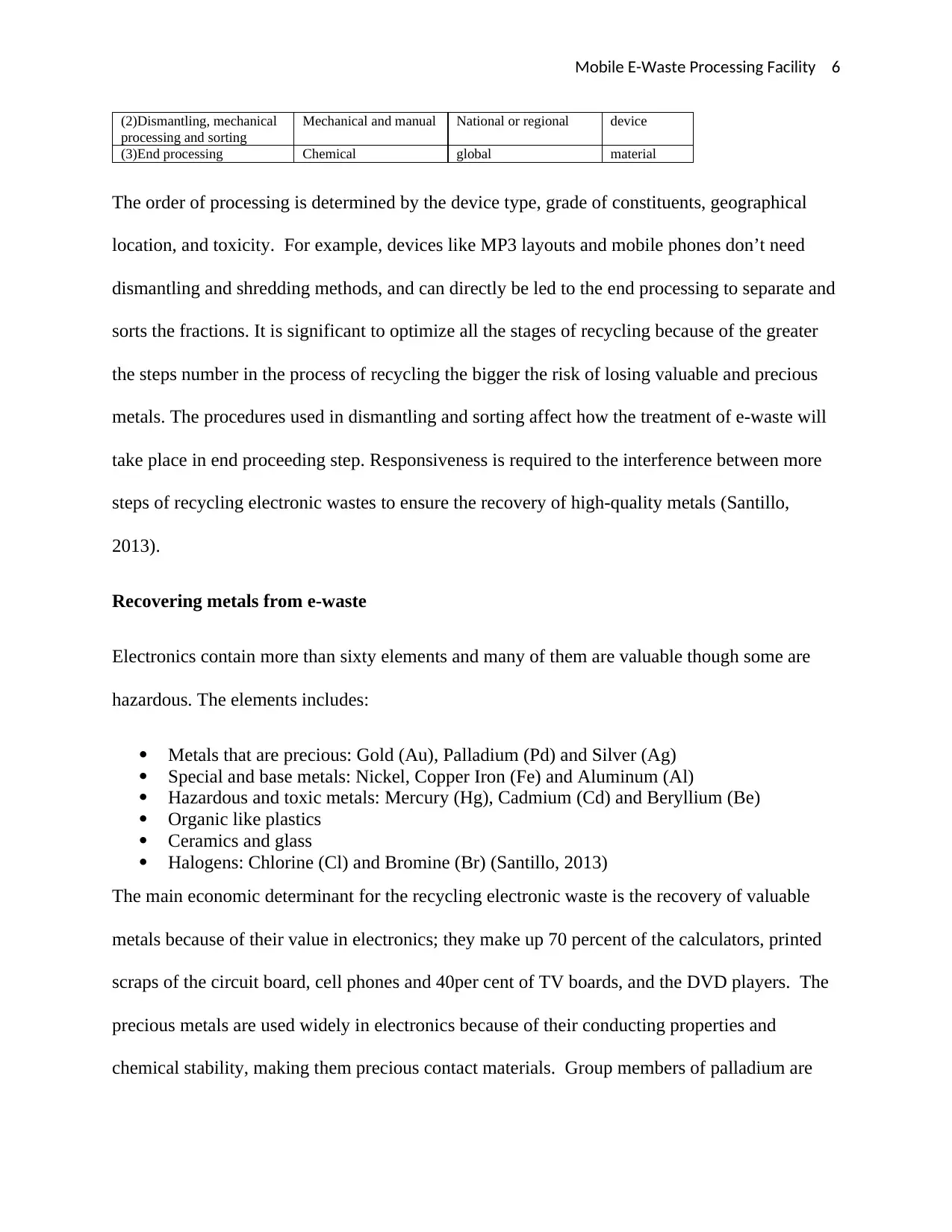

It is significant to know that steps 2 and 1 have been established with the emphasis on stream of

electronic devices like C& F appliances, ICT equipment, TVs and monitors and uses mechanical

processes, whereas the technologies of final processing have been established with the emphasis

of the material stream and uses chemical processes

Table 1 below show methods processing e wastes

Stage of recycling Process level Stream

(1) collection Manual National or regional device

are directed to an smelter that is integrated where the retrieval of precious metals, non-ferrous

metals and copper takes place.

End processing: end processing occurs at the global level and is determined by the steam

materials. The aim of this end processing is to recover the constituents that are valuable and

remove the impurities. Assaying and sampling are important to determine the content of valuable

metals and the composition of the electronic waste stream and ensure that the process that is

optimum is employed to recover the precious metals. Pyrometallurgical is the process employed

to recover the valuable metals but hydrometallurgical and bio metallurgical can also be used

(Bergman, 2017).

The collection, preprocessing, dismantling and repossession from less compound of electronic

wastes such as copper, ferrous, and aluminium normally occurs at national or local level. The

end processing is a more complex component of electronic wastes like batteries, circuit board,

and cell phones mostly take place in global context and occur in integrated smelters of copper.

These smelters are non-ferrous metallurgy extractive to separate segments that are complex into

their basic metals and these companies are very expensive to construct hence it is not economical

to build them in all counties (Santillo, 2010).

It is significant to know that steps 2 and 1 have been established with the emphasis on stream of

electronic devices like C& F appliances, ICT equipment, TVs and monitors and uses mechanical

processes, whereas the technologies of final processing have been established with the emphasis

of the material stream and uses chemical processes

Table 1 below show methods processing e wastes

Stage of recycling Process level Stream

(1) collection Manual National or regional device

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 6

(2)Dismantling, mechanical

processing and sorting

Mechanical and manual National or regional device

(3)End processing Chemical global material

The order of processing is determined by the device type, grade of constituents, geographical

location, and toxicity. For example, devices like MP3 layouts and mobile phones don’t need

dismantling and shredding methods, and can directly be led to the end processing to separate and

sorts the fractions. It is significant to optimize all the stages of recycling because of the greater

the steps number in the process of recycling the bigger the risk of losing valuable and precious

metals. The procedures used in dismantling and sorting affect how the treatment of e-waste will

take place in end proceeding step. Responsiveness is required to the interference between more

steps of recycling electronic wastes to ensure the recovery of high-quality metals (Santillo,

2013).

Recovering metals from e-waste

Electronics contain more than sixty elements and many of them are valuable though some are

hazardous. The elements includes:

Metals that are precious: Gold (Au), Palladium (Pd) and Silver (Ag)

Special and base metals: Nickel, Copper Iron (Fe) and Aluminum (Al)

Hazardous and toxic metals: Mercury (Hg), Cadmium (Cd) and Beryllium (Be)

Organic like plastics

Ceramics and glass

Halogens: Chlorine (Cl) and Bromine (Br) (Santillo, 2013)

The main economic determinant for the recycling electronic waste is the recovery of valuable

metals because of their value in electronics; they make up 70 percent of the calculators, printed

scraps of the circuit board, cell phones and 40per cent of TV boards, and the DVD players. The

precious metals are used widely in electronics because of their conducting properties and

chemical stability, making them precious contact materials. Group members of palladium are

(2)Dismantling, mechanical

processing and sorting

Mechanical and manual National or regional device

(3)End processing Chemical global material

The order of processing is determined by the device type, grade of constituents, geographical

location, and toxicity. For example, devices like MP3 layouts and mobile phones don’t need

dismantling and shredding methods, and can directly be led to the end processing to separate and

sorts the fractions. It is significant to optimize all the stages of recycling because of the greater

the steps number in the process of recycling the bigger the risk of losing valuable and precious

metals. The procedures used in dismantling and sorting affect how the treatment of e-waste will

take place in end proceeding step. Responsiveness is required to the interference between more

steps of recycling electronic wastes to ensure the recovery of high-quality metals (Santillo,

2013).

Recovering metals from e-waste

Electronics contain more than sixty elements and many of them are valuable though some are

hazardous. The elements includes:

Metals that are precious: Gold (Au), Palladium (Pd) and Silver (Ag)

Special and base metals: Nickel, Copper Iron (Fe) and Aluminum (Al)

Hazardous and toxic metals: Mercury (Hg), Cadmium (Cd) and Beryllium (Be)

Organic like plastics

Ceramics and glass

Halogens: Chlorine (Cl) and Bromine (Br) (Santillo, 2013)

The main economic determinant for the recycling electronic waste is the recovery of valuable

metals because of their value in electronics; they make up 70 percent of the calculators, printed

scraps of the circuit board, cell phones and 40per cent of TV boards, and the DVD players. The

precious metals are used widely in electronics because of their conducting properties and

chemical stability, making them precious contact materials. Group members of palladium are

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 7

used in switches, relays and sensors also other materials like zinc and copper drive the recycling.

The following materials can be grouped based on their relative value:

High value: capacitors, mobile phones and circuit boards from the mainframes

Medium value: boards of PC, handheld and laptop computer circuit boards

Low value: boards of TV, printed board, monitor boards, calculators, cordless phones,

and bulk shredded material after separation of aluminium or iron (Allsopp, 2014).

The volumes of valuable metals in the PWBs fluctuates from computers to televisions,

calculators and DVD players, but it has been noted that PWBs from mobile phones and personal

computers have the maximum capacity of precious metals. It is well-known that printed wiring

boards may have toxic components such as switches, batteries and relays that must be removed

manually before any processing and the values of printed wiring boards’ doubles annually

(Allsopp, 2014).

Urban mining

Urban mining describes the process of recycling components that are valuable from the building,

wastes, and existing products. It is a growth that has resulted in economic and environmental

benefits and creation of opportunities for jobs through recycling. Primary metal production like

smelting, mining, refining and concentration has the important impact especially for the special

and precious metals because the metals are lowly concentrated in the ores. Getting materials

from the electronic scrap is profitable than processing concentration because of the energy

savings associated with the recycling of electronic scraps. It needs only 10 to 15 percent of the

energy in the refining and smelting concentrates (Andrewes, 2012).

Funds are made to treat the electronic scrap and regain the precious materials, mostly as the raw

materials are becoming expensive and scarce. Production of copper from methods of primary

production involves many processes like grinding, roasting, crushing, refining and smelting to

used in switches, relays and sensors also other materials like zinc and copper drive the recycling.

The following materials can be grouped based on their relative value:

High value: capacitors, mobile phones and circuit boards from the mainframes

Medium value: boards of PC, handheld and laptop computer circuit boards

Low value: boards of TV, printed board, monitor boards, calculators, cordless phones,

and bulk shredded material after separation of aluminium or iron (Allsopp, 2014).

The volumes of valuable metals in the PWBs fluctuates from computers to televisions,

calculators and DVD players, but it has been noted that PWBs from mobile phones and personal

computers have the maximum capacity of precious metals. It is well-known that printed wiring

boards may have toxic components such as switches, batteries and relays that must be removed

manually before any processing and the values of printed wiring boards’ doubles annually

(Allsopp, 2014).

Urban mining

Urban mining describes the process of recycling components that are valuable from the building,

wastes, and existing products. It is a growth that has resulted in economic and environmental

benefits and creation of opportunities for jobs through recycling. Primary metal production like

smelting, mining, refining and concentration has the important impact especially for the special

and precious metals because the metals are lowly concentrated in the ores. Getting materials

from the electronic scrap is profitable than processing concentration because of the energy

savings associated with the recycling of electronic scraps. It needs only 10 to 15 percent of the

energy in the refining and smelting concentrates (Andrewes, 2012).

Funds are made to treat the electronic scrap and regain the precious materials, mostly as the raw

materials are becoming expensive and scarce. Production of copper from methods of primary

production involves many processes like grinding, roasting, crushing, refining and smelting to

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 8

produce one ton of copper form two hundred tons of copper ore. the energy of approximately

80/5 will be needed to yield copper from sources of mining is related to milling and mining

process because of the stem of intensive energy like grinding, crushing and hauling. This is

because the copper that is recycled avoids the stages that need intensive energy and has much

copper content than copper ores, it is beneficial to reprocess copper. Copper that is recycled

contains 13 to 19 percent annual consumption of copper globally (Stanmore, 2012).

Pre-processing

The mechanical processing’s level of ore influence directly how the electronic wastes in the end

processing and also the metals’ concentration can be regained. It is usually advantageous to

remove the components with valuable metals value before the pre-processing. Devices that are

complex and components like circuit boards and small devices of high grade and cell phones

should be removed from the electronic wastes stream before the mechanical process. When

circuit board are not shredded and dismantled manually precious metals mix with other

components like aluminium or glass. Grinding and shredding of electronic wastes of high grades

can result in the loss of 40 percent of precious metals and formation of dioxins and dangerous

dust (Wilber, 2015).

EVALUATION

Preliminary design for the recycling process

Extractive metallurgy

The most widely used metal is copper in the electronics because of its electrical conductivity is

high. Metals are added frequently to copper to adjust the hardness, resistance to corrosion and

strength. The alloys of copper are metals that have copper as the main components like bronzes

produce one ton of copper form two hundred tons of copper ore. the energy of approximately

80/5 will be needed to yield copper from sources of mining is related to milling and mining

process because of the stem of intensive energy like grinding, crushing and hauling. This is

because the copper that is recycled avoids the stages that need intensive energy and has much

copper content than copper ores, it is beneficial to reprocess copper. Copper that is recycled

contains 13 to 19 percent annual consumption of copper globally (Stanmore, 2012).

Pre-processing

The mechanical processing’s level of ore influence directly how the electronic wastes in the end

processing and also the metals’ concentration can be regained. It is usually advantageous to

remove the components with valuable metals value before the pre-processing. Devices that are

complex and components like circuit boards and small devices of high grade and cell phones

should be removed from the electronic wastes stream before the mechanical process. When

circuit board are not shredded and dismantled manually precious metals mix with other

components like aluminium or glass. Grinding and shredding of electronic wastes of high grades

can result in the loss of 40 percent of precious metals and formation of dioxins and dangerous

dust (Wilber, 2015).

EVALUATION

Preliminary design for the recycling process

Extractive metallurgy

The most widely used metal is copper in the electronics because of its electrical conductivity is

high. Metals are added frequently to copper to adjust the hardness, resistance to corrosion and

strength. The alloys of copper are metals that have copper as the main components like bronzes

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 9

that is Cu alloyed with aluminium, silicon and tin; brass that is zinc alloyed with copper and

precious metals alloys that are copper alloyed with gold, silver and palladium.

Numerous metal elements melt in copper like silver, palladium, platinum, gold, tellurium and

selenium; hence getting metals from the electronic wastes focus on the smelting to have

contaminated Cu and them electrorefining the copper into uncontaminated Cu and other

materials. There are three major procedures of recycling e wastes, hydrometallurgy, bio

metallurgy and pyrometallurgy serving as the primary method. Hydrometallurgy is the method of

low temperature and uses aqueous chemistry to recover metals and pyrometallurgy uses high

temperatures for melting electronic wastes into impure copper that have other materials (Canada,

2015).

Pyrometallurgical processing

This process consists of melting the electronic wastes in the furnace of high temperature and the

most process that is commonly used in the recovery of metals from WEEE. This process is

known as smelting recover the copper content in the electronic wastes and any other noble

metals that in the process of smelting dissolve copper like silver, platinum, palladium and gold.

Aluminum and iron are not got in the process of smelting copper instead they are iodized to slag.

Electronic wastes can be processed in the small furnace, but the most industrious process is to

compress them with concentrates of copper sulphide in the large furnace of smelting copper like

anode copper furnace, copper converter and copper converting and converting furnace like

Naronda process (Chancerel, 2012).

Global electronic wastes are sent 4 integrated plants or smelters worldwide that process

electronic wastes and get valuable metals, located in Germany, Belgium, and Europe, Sweden

that is Cu alloyed with aluminium, silicon and tin; brass that is zinc alloyed with copper and

precious metals alloys that are copper alloyed with gold, silver and palladium.

Numerous metal elements melt in copper like silver, palladium, platinum, gold, tellurium and

selenium; hence getting metals from the electronic wastes focus on the smelting to have

contaminated Cu and them electrorefining the copper into uncontaminated Cu and other

materials. There are three major procedures of recycling e wastes, hydrometallurgy, bio

metallurgy and pyrometallurgy serving as the primary method. Hydrometallurgy is the method of

low temperature and uses aqueous chemistry to recover metals and pyrometallurgy uses high

temperatures for melting electronic wastes into impure copper that have other materials (Canada,

2015).

Pyrometallurgical processing

This process consists of melting the electronic wastes in the furnace of high temperature and the

most process that is commonly used in the recovery of metals from WEEE. This process is

known as smelting recover the copper content in the electronic wastes and any other noble

metals that in the process of smelting dissolve copper like silver, platinum, palladium and gold.

Aluminum and iron are not got in the process of smelting copper instead they are iodized to slag.

Electronic wastes can be processed in the small furnace, but the most industrious process is to

compress them with concentrates of copper sulphide in the large furnace of smelting copper like

anode copper furnace, copper converter and copper converting and converting furnace like

Naronda process (Chancerel, 2012).

Global electronic wastes are sent 4 integrated plants or smelters worldwide that process

electronic wastes and get valuable metals, located in Germany, Belgium, and Europe, Sweden

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 10

and one in Canada. Modernized sized electronic wastes smelters are located in South Korea and

Japan. The need of electronic wastes processing and recycling capacity is recognized widely by

some of the global leaders in smelting. Xstrata announced the plans for doubling the capacity of

the electronic wastes recycling giving the smelter with the capacity to process and receive one

hundred thousand metric yearly. Boliden announced that it will be investing two hundred and

two million dollars to triple the capacity of electronic wastes recycling from forty-five thousand

to one hundred and twenty thousand metric ton yearly. This expansion will enable for the 2.7

million metric ton of electronic wastes to be recycled (Chancerel, 2011).

The general process at the global smelters is described below

Sorting and dismantling

Removal of toxic components: toxic components like cathode ray tube, batteries, and bulbs of

mercury are removed at the selected stations for sorting. Horne smelter of Xstrata, Cathode ray

tubes are completely recycled; tubes of plastics are sent to the smelters; the glass is reused at the

facility as the agent of fluxing and lead is recovered (Sakai, 2015).

Reduction of the particles size: after the electronics have been removed from the toxic

components, they are shredder into the fine and scrap metals. The material shredded is separated

further by the magnets of cross belts, shaker tables, sand flow units and eddy currents and other

methods of magnetic and density separations. Dust is produced during proses of pretreatment and

is collected in the system of bag-house and filters. Dust generated can have content of high

precious metals and a significant amount of components of high burn loss like paper, plastic and

wood and also may have pollutants (Zennegg, 2014).

and one in Canada. Modernized sized electronic wastes smelters are located in South Korea and

Japan. The need of electronic wastes processing and recycling capacity is recognized widely by

some of the global leaders in smelting. Xstrata announced the plans for doubling the capacity of

the electronic wastes recycling giving the smelter with the capacity to process and receive one

hundred thousand metric yearly. Boliden announced that it will be investing two hundred and

two million dollars to triple the capacity of electronic wastes recycling from forty-five thousand

to one hundred and twenty thousand metric ton yearly. This expansion will enable for the 2.7

million metric ton of electronic wastes to be recycled (Chancerel, 2011).

The general process at the global smelters is described below

Sorting and dismantling

Removal of toxic components: toxic components like cathode ray tube, batteries, and bulbs of

mercury are removed at the selected stations for sorting. Horne smelter of Xstrata, Cathode ray

tubes are completely recycled; tubes of plastics are sent to the smelters; the glass is reused at the

facility as the agent of fluxing and lead is recovered (Sakai, 2015).

Reduction of the particles size: after the electronics have been removed from the toxic

components, they are shredder into the fine and scrap metals. The material shredded is separated

further by the magnets of cross belts, shaker tables, sand flow units and eddy currents and other

methods of magnetic and density separations. Dust is produced during proses of pretreatment and

is collected in the system of bag-house and filters. Dust generated can have content of high

precious metals and a significant amount of components of high burn loss like paper, plastic and

wood and also may have pollutants (Zennegg, 2014).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 11

The dust can be sent to the process of smelting to recover the valuable metals. It is usual for the

high-grade electronic wastes not to pass through the process of mechanical shredding instead

they go directly to the integrated smelter. The shredding of electronic wastes of high grade is not

done due to:

Manufacture of valuable metals with dust

Significant loss of the components and metals in the steams that cannot be recovered such

as iron, plastics and aluminium.

The financial value of the valuable metal is higher than base metals' value, such as

aluminium and iron. It is not worth losing precious metals to get base metals.

Saving money and time spent in the pretreatment (Wijnen, 2012).

Sample essay: electronic scrap is experimented to evaluate the content of precious metals and

copper and separated materials sent to the smelter.

End processing

Stage of smelting: the electronic scraps that have already been shredded are directed to the

incorporated smelter. The resolution of iron sulphide and copper is produced known as ‘matte’

while ironing and other oxides from the solution of silicates known as ‘slag’. The valuable

metals are held in ‘matte’ which proceed to the transforming stage. The ‘slag’ is separately

treated through by the lead blast furnace, special plants of metals and refinery of lead. It is

significant to note that electronic wastes of high grades can directly be sent to the converter stage

without passing to the smelting stage (WHO, 2010).

Converting stage: the converting stage follows the smelting stage where the ‘matte’ is converted

to polluted copper known as ‘blister’ Cu.

Furnace of anode: the blister of liquid Cu is developed in the furnace anode. The bubble Cu is

cast to anodes that are electrified to the copper that is pure.

The dust can be sent to the process of smelting to recover the valuable metals. It is usual for the

high-grade electronic wastes not to pass through the process of mechanical shredding instead

they go directly to the integrated smelter. The shredding of electronic wastes of high grade is not

done due to:

Manufacture of valuable metals with dust

Significant loss of the components and metals in the steams that cannot be recovered such

as iron, plastics and aluminium.

The financial value of the valuable metal is higher than base metals' value, such as

aluminium and iron. It is not worth losing precious metals to get base metals.

Saving money and time spent in the pretreatment (Wijnen, 2012).

Sample essay: electronic scrap is experimented to evaluate the content of precious metals and

copper and separated materials sent to the smelter.

End processing

Stage of smelting: the electronic scraps that have already been shredded are directed to the

incorporated smelter. The resolution of iron sulphide and copper is produced known as ‘matte’

while ironing and other oxides from the solution of silicates known as ‘slag’. The valuable

metals are held in ‘matte’ which proceed to the transforming stage. The ‘slag’ is separately

treated through by the lead blast furnace, special plants of metals and refinery of lead. It is

significant to note that electronic wastes of high grades can directly be sent to the converter stage

without passing to the smelting stage (WHO, 2010).

Converting stage: the converting stage follows the smelting stage where the ‘matte’ is converted

to polluted copper known as ‘blister’ Cu.

Furnace of anode: the blister of liquid Cu is developed in the furnace anode. The bubble Cu is

cast to anodes that are electrified to the copper that is pure.

Mobile E-Waste Processing Facility 12

Electrorefining stage: in this process, anode copper undergo refining to have cathodes of pure

copper and precious metals like gold, silver, tellurium and selenium settle down as the

precipitates at the bottom of the cell for electrorefining (Viberg, 2010).

Refinery of precious metals: the residue of the precious metals is melted, cast and refined to have

bullion of precious metals.

Plastic constituents of the electronic wastes cannot be reprocessed easily because of the mix of

retardants flames. Smelting process is able to use the content of plastics' energy. The usage of

energy is decreased because of burning of plastics and combustible constituents in the electronic

wastes feed, that substitute the coke needed as the energy source and reducing agent (Luo, 2013).

Although the pyrometallurgical is the best method for valuable metals recovery from the

electronic wastes, it has some limitations:

Certain product component lie bare fibreglass boards and chips cannot be recovered by

smelting

Aluminum and iron cannot be recovered by smelting because they iodized and transferred

in the slag

Smelting retardants flame and polyvinyl chlorides in the electronic wastes lead to dioxins

formation and need special control of the emissions

The process of pyrometallurgy cannot separate all metals fully, therefore

hydrometallurgical method must be subsequently used (Yanagisawa, 2013)

Electrorefining stage: in this process, anode copper undergo refining to have cathodes of pure

copper and precious metals like gold, silver, tellurium and selenium settle down as the

precipitates at the bottom of the cell for electrorefining (Viberg, 2010).

Refinery of precious metals: the residue of the precious metals is melted, cast and refined to have

bullion of precious metals.

Plastic constituents of the electronic wastes cannot be reprocessed easily because of the mix of

retardants flames. Smelting process is able to use the content of plastics' energy. The usage of

energy is decreased because of burning of plastics and combustible constituents in the electronic

wastes feed, that substitute the coke needed as the energy source and reducing agent (Luo, 2013).

Although the pyrometallurgical is the best method for valuable metals recovery from the

electronic wastes, it has some limitations:

Certain product component lie bare fibreglass boards and chips cannot be recovered by

smelting

Aluminum and iron cannot be recovered by smelting because they iodized and transferred

in the slag

Smelting retardants flame and polyvinyl chlorides in the electronic wastes lead to dioxins

formation and need special control of the emissions

The process of pyrometallurgy cannot separate all metals fully, therefore

hydrometallurgical method must be subsequently used (Yanagisawa, 2013)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 36

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.