Effectiveness of Exercise for Falls in Dementia: A Systematic Review

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/23

|14

|11866

|30

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a systematic review and meta-analysis that investigates the effectiveness of exercise programs in reducing falls among older people with dementia living in the community. The study reviewed articles published between January 2000 and February 2014 from six electronic databases, focusing on randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental trials. The findings suggest that exercise programs can potentially assist in preventing falls, with the exercise group showing a lower mean number of falls and a reduced risk of being a faller compared to the control group. The review highlights the need for further research with larger sample sizes, standardized measurement outcomes, and longer follow-up periods to inform evidence-based recommendations. The study emphasizes the importance of exercise as a falls prevention strategy for older adults with dementia, despite the limitations of the current research. The review included studies using PLWD in a residential care or hospital setting, four had a majority of participants living in the community, nine had a mix of older people living in both community and residential care, and three were unclear in describing the setting.

© 2015 Burton et al. This work is published by Dove Medical Press Limited, and licensed under Creative Commons

License. The full terms of the License are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/. Non-commer

permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. Permissions beyond the scope of the Licen

how to request permission may be found at: http://www.dovepress.com/permissions.php

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10 421–434

Clinical Interventions in Aging Dovepress

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

421

R e v I e w

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article

http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S71691

effectiveness of exercise programs to reduce

falls in older people with dementia living in th

community: a systematic review and meta-an

elissa Burton1,2

vinicius Cavalheri1

Richard Adams3

Colleen Oakley Browne4

Petra Bovery-Spencer4

Audra M Fenton3

Bruce w Campbell5

Keith D Hill1,6

1School of Physiotherapy and exercise

Science, Curtin University, Perth, wA,

Australia;2Research Department,

Silver Chain, Perth, wA, Australia;

3Community Services, west Gippsland

Healthcare Group, warragul, vIC,

Australia;4Falls Prevention for

People Living with Dementia Project,

Central west Gippsland Primary

Care Partnership, Moe, vIC, Australia;

5Allied Health, Latrobe Regional

Hospital, Traralgon, vIC, Australia;

6Preventive and Public Health

Division, National Ageing Research

Institute, Melbourne, vIC, Australia

Objective:The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the effec-

tiveness of exercise programs to reduce falls in older people with dementia who are living in

the community.

Method:Peer-reviewed articles (randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and quasi-experimental

trials) published in English between January 2000 and February 2014, retrieved from six elec-

tronic databases – Medline (ProQuest), CINAHL, PubMed, PsycInfo, EMBASE and Scopus –

according to predefined inclusion criteria were included. Where possible, results were pooled

and meta-analysis was conducted.

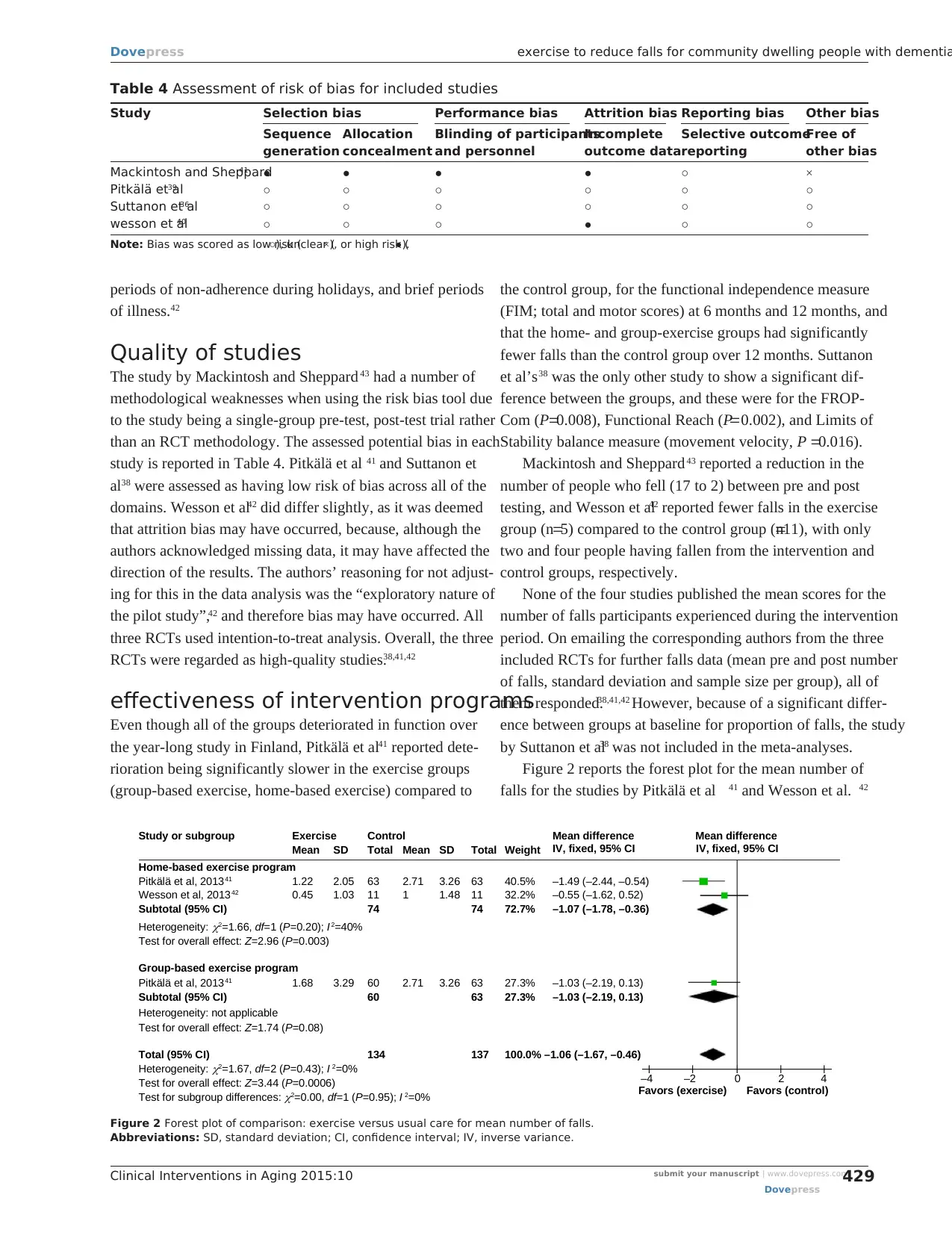

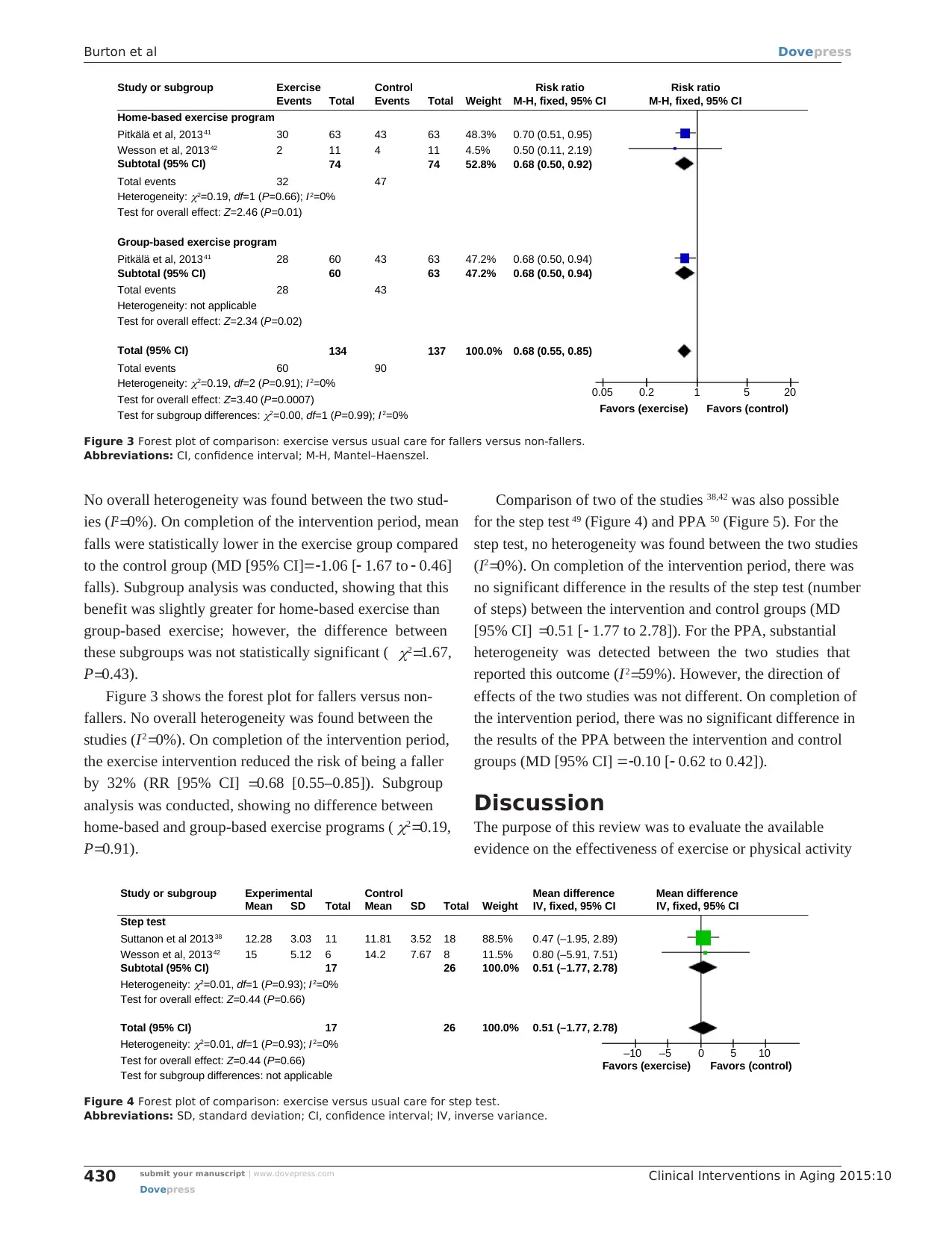

Results:Four articles (three RCT and one single-group pre- and post-test pilot study) were

included. The study quality of the three RCTs was high; however, measurement outcomes,

interventions, and follow-up time periods differed across studies. On completion of the interven-

tion period, the mean number of falls was lower in the exercise group compared to the control

group (mean difference [MD] [95% confidence interval {CI}] =-1.06 [- 1.67 to - 0.46] falls).

Importantly, the exercise intervention reduced the risk of being a faller by 32% (risk ratio [95%

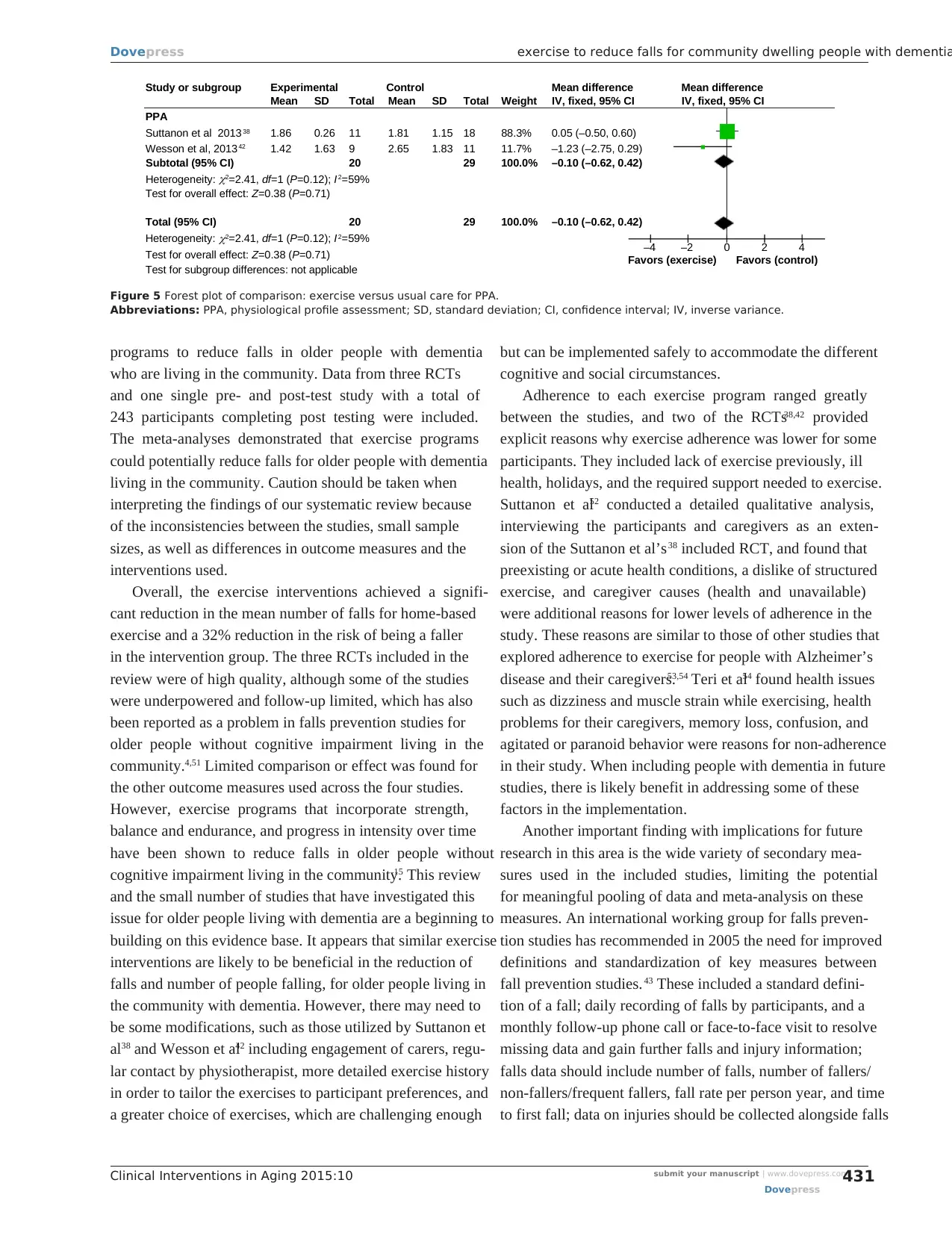

CI] =0.68 [0.55–0.85]). Only two other outcomes were reported in two or more of the studies

(step test and physiological profile assessment). No between-group differences were observed

in the results of the step test (number of steps) (MD [95% CI] =0.51 [- 1.77 to 2.78]) or the

physiological profile assessment (MD [95% CI] =-0.10 [- 0.62 to 0.42]).

Conclusion:Findings from this review suggest that an exercise program may potentially assist

in preventing falls of older people with dementia living in the community. However, further

research is needed with studies using larger sample sizes, standardized measurement outcomes,

and longer follow-up periods, to inform evidence-based recommendations.

Keywords:cognitive impairment, older people, physical activity, fallers, community

dwelling

Introduction

Dementia is a major health issue predominantly affecting older people. It is estimated

that over 44 million people worldwide are living with dementia, and by 2050 there

may be as many as 135.5 million people diagnosed with dementia.1 The world popula-

tion is aging and as such it is expected that the increase in the number of older people

will correspond with an increase in the number of older people living with dementia

(PLWD). Dementia is a syndrome that impairs brain function and cognition. As the

severity of dementia increases over time, the person with dementia often has increased

difficulties with many important functions, including gait impairments, problems with

postural control, reduced participation in activities such as shopping and driving,

Correspondence: elissa Burton

Curtin University, School of Physiotherapy

and exercise Science, GPO Box U 1987,

Perth, wA 6845, Australia

Tel +61 8 9266 3681

Fax+61 8 9266 3699

email e.burton@curtin.edu.au

License. The full terms of the License are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/. Non-commer

permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. Permissions beyond the scope of the Licen

how to request permission may be found at: http://www.dovepress.com/permissions.php

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10 421–434

Clinical Interventions in Aging Dovepress

submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

421

R e v I e w

open access to scientific and medical research

Open Access Full Text Article

http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S71691

effectiveness of exercise programs to reduce

falls in older people with dementia living in th

community: a systematic review and meta-an

elissa Burton1,2

vinicius Cavalheri1

Richard Adams3

Colleen Oakley Browne4

Petra Bovery-Spencer4

Audra M Fenton3

Bruce w Campbell5

Keith D Hill1,6

1School of Physiotherapy and exercise

Science, Curtin University, Perth, wA,

Australia;2Research Department,

Silver Chain, Perth, wA, Australia;

3Community Services, west Gippsland

Healthcare Group, warragul, vIC,

Australia;4Falls Prevention for

People Living with Dementia Project,

Central west Gippsland Primary

Care Partnership, Moe, vIC, Australia;

5Allied Health, Latrobe Regional

Hospital, Traralgon, vIC, Australia;

6Preventive and Public Health

Division, National Ageing Research

Institute, Melbourne, vIC, Australia

Objective:The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the effec-

tiveness of exercise programs to reduce falls in older people with dementia who are living in

the community.

Method:Peer-reviewed articles (randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and quasi-experimental

trials) published in English between January 2000 and February 2014, retrieved from six elec-

tronic databases – Medline (ProQuest), CINAHL, PubMed, PsycInfo, EMBASE and Scopus –

according to predefined inclusion criteria were included. Where possible, results were pooled

and meta-analysis was conducted.

Results:Four articles (three RCT and one single-group pre- and post-test pilot study) were

included. The study quality of the three RCTs was high; however, measurement outcomes,

interventions, and follow-up time periods differed across studies. On completion of the interven-

tion period, the mean number of falls was lower in the exercise group compared to the control

group (mean difference [MD] [95% confidence interval {CI}] =-1.06 [- 1.67 to - 0.46] falls).

Importantly, the exercise intervention reduced the risk of being a faller by 32% (risk ratio [95%

CI] =0.68 [0.55–0.85]). Only two other outcomes were reported in two or more of the studies

(step test and physiological profile assessment). No between-group differences were observed

in the results of the step test (number of steps) (MD [95% CI] =0.51 [- 1.77 to 2.78]) or the

physiological profile assessment (MD [95% CI] =-0.10 [- 0.62 to 0.42]).

Conclusion:Findings from this review suggest that an exercise program may potentially assist

in preventing falls of older people with dementia living in the community. However, further

research is needed with studies using larger sample sizes, standardized measurement outcomes,

and longer follow-up periods, to inform evidence-based recommendations.

Keywords:cognitive impairment, older people, physical activity, fallers, community

dwelling

Introduction

Dementia is a major health issue predominantly affecting older people. It is estimated

that over 44 million people worldwide are living with dementia, and by 2050 there

may be as many as 135.5 million people diagnosed with dementia.1 The world popula-

tion is aging and as such it is expected that the increase in the number of older people

will correspond with an increase in the number of older people living with dementia

(PLWD). Dementia is a syndrome that impairs brain function and cognition. As the

severity of dementia increases over time, the person with dementia often has increased

difficulties with many important functions, including gait impairments, problems with

postural control, reduced participation in activities such as shopping and driving,

Correspondence: elissa Burton

Curtin University, School of Physiotherapy

and exercise Science, GPO Box U 1987,

Perth, wA 6845, Australia

Tel +61 8 9266 3681

Fax+61 8 9266 3699

email e.burton@curtin.edu.au

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

422

Burton et al

and an increase in disability leading to difficulties in eat-

ing, bathing, and dressing.2,3 The impairments in cognition,

gait, and postural control also increase the risk of falls in

people with dementia. Approximately 30% of adults aged

65 years and over living in the community experience one or

more fall each year,4 but up to 50%–80% of PLWD fall in a

12-month period.5,6 There are many identified risk factors for

falls, including intrinsic factors such as postural instability

(gait and balance impairments), medications, neurocardio-

vascular complications, and vision impairment, as well as

extrinsic factors such as the environment (curbs, rugs, or poor

lighting).7 Falls can often lead to a fear of falling or loss of

confidence, which may result in a decline in activity and ulti-

mately a decrease in strength, balance, and mobility, leading

to decreased functional ability and a loss of independence.8,9

Falls are also often a trigger for emergency department or

hospital admission for older people with dementia 10 and/or

admission to residential care.10,11

Balance and mobility impairments in older people

have been shown to be a strong independent risk factor for

falling,12 and have been shown to decline at a significantly

faster rate in PLWD than age-matched older people without

cognitive impairment.13 To combat postural instability and

decreases in function, a large number of studies have been

conducted, investigating the effectiveness of exercise or

physical activity programs to prevent falls for older people

with a history of falling. 4,14 Reviews of these studies have

shown that strength- and balance-focused exercise programs

have been successful in decreasing the rate of falls for older

people living in the community with no cognitive impair-

ment, using both group- and home-based environments for

exercise. Based on these results, exercise or physical activity

programs are viewed as an important part of falls prevention

programs.3,4,15 However, direct translation of falls prevention

programs that have been shown to be effective in reducing

falls in samples with no cognitive impairment (eg, Close

et al16 multifactorial intervention) may not be effective when

implemented with people with cognitive impairment.17

Despite the higher risk of falls and greater rate of decline

of balance and gait in PLWD in the community, there has

been only a small but growing amount of research investigat-

ing the effect of exercise on improving physical performance

and reducing falls in people with dementia. There have been

nine systematic reviews14,18–25 and four general reviews7,17,26,27

investigating the effects of dementia/Alzheimer’s disease

on falls, and eight systematic reviews exploring the effects

of exercise (types of exercise) on people with cognitive

impairment. 3,28–34 Six of the 21 reviews reported earlier

included studies using PLWD in a residential care or hospital

setting, four had a majority of participants living in the

community, nine had a mix of older people living in both

community and residential care, and three were unclear

in describing the setting. Of the four reviews where older

people with dementia living in the community setting were

the majority sample population, one focused on medicine

and falls,21 another recruited participants living in the com-

munity from health care settings (emergency department,

dementia specific service, etc),25 the third looked at falls

risk with no specific emphasis on exercise,19 and the fourth

investigated the relationship between executive function,

falls, and gait abnormalities.32 There is a dearth of research

that specifically explored falls prevention exercise interven-

tions for people with dementia (cognitive impairment) living

in the community.

One systematic review by Hauer et al 35 did investigate

the effectiveness of physical training on motor performance

and fall prevention in cognitively impaired older persons

(search strategy was between 1966 and 2004). Again, of the

eleven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included in this

review, nine were from a residential/long-term care/hospital

setting and one was of people living in the community, and

in the other the setting was unknown. Physical training was

not defined and appeared to represent strength and balance

programs designed by physiotherapists to be conducted in

either an individual or group setting.35 Physical activity

programs such as Tai Chi, which have been shown to be

effective in reducing falls, were not included.

In summary, to date the reviews published in this area are

limited when exploring those that have specifically focused

on older PLWD in the community with exercise and/or physi-

cal activity as the intervention, and with falls as the outcome

of interest. This systematic review seeks to address this gap.

The purpose of this review is to evaluate the available evi-

dence on the effectiveness of exercise or physical activity

programs to reduce falls in older people with dementia who

are living in the community.

Method

eligibility criteria

The review is limited to studies meeting the following eli-

gibility criteria:

• aged 60 years and over (at least 50% of the sample size);

• living in the community;

• PLWD or cognitively impaired. Dementia had to have

been identified by diagnosis by a doctor/specialist, or a

validated test, such as the Mini Mental State Examination

Dovepress

Dovepress

422

Burton et al

and an increase in disability leading to difficulties in eat-

ing, bathing, and dressing.2,3 The impairments in cognition,

gait, and postural control also increase the risk of falls in

people with dementia. Approximately 30% of adults aged

65 years and over living in the community experience one or

more fall each year,4 but up to 50%–80% of PLWD fall in a

12-month period.5,6 There are many identified risk factors for

falls, including intrinsic factors such as postural instability

(gait and balance impairments), medications, neurocardio-

vascular complications, and vision impairment, as well as

extrinsic factors such as the environment (curbs, rugs, or poor

lighting).7 Falls can often lead to a fear of falling or loss of

confidence, which may result in a decline in activity and ulti-

mately a decrease in strength, balance, and mobility, leading

to decreased functional ability and a loss of independence.8,9

Falls are also often a trigger for emergency department or

hospital admission for older people with dementia 10 and/or

admission to residential care.10,11

Balance and mobility impairments in older people

have been shown to be a strong independent risk factor for

falling,12 and have been shown to decline at a significantly

faster rate in PLWD than age-matched older people without

cognitive impairment.13 To combat postural instability and

decreases in function, a large number of studies have been

conducted, investigating the effectiveness of exercise or

physical activity programs to prevent falls for older people

with a history of falling. 4,14 Reviews of these studies have

shown that strength- and balance-focused exercise programs

have been successful in decreasing the rate of falls for older

people living in the community with no cognitive impair-

ment, using both group- and home-based environments for

exercise. Based on these results, exercise or physical activity

programs are viewed as an important part of falls prevention

programs.3,4,15 However, direct translation of falls prevention

programs that have been shown to be effective in reducing

falls in samples with no cognitive impairment (eg, Close

et al16 multifactorial intervention) may not be effective when

implemented with people with cognitive impairment.17

Despite the higher risk of falls and greater rate of decline

of balance and gait in PLWD in the community, there has

been only a small but growing amount of research investigat-

ing the effect of exercise on improving physical performance

and reducing falls in people with dementia. There have been

nine systematic reviews14,18–25 and four general reviews7,17,26,27

investigating the effects of dementia/Alzheimer’s disease

on falls, and eight systematic reviews exploring the effects

of exercise (types of exercise) on people with cognitive

impairment. 3,28–34 Six of the 21 reviews reported earlier

included studies using PLWD in a residential care or hospital

setting, four had a majority of participants living in the

community, nine had a mix of older people living in both

community and residential care, and three were unclear

in describing the setting. Of the four reviews where older

people with dementia living in the community setting were

the majority sample population, one focused on medicine

and falls,21 another recruited participants living in the com-

munity from health care settings (emergency department,

dementia specific service, etc),25 the third looked at falls

risk with no specific emphasis on exercise,19 and the fourth

investigated the relationship between executive function,

falls, and gait abnormalities.32 There is a dearth of research

that specifically explored falls prevention exercise interven-

tions for people with dementia (cognitive impairment) living

in the community.

One systematic review by Hauer et al 35 did investigate

the effectiveness of physical training on motor performance

and fall prevention in cognitively impaired older persons

(search strategy was between 1966 and 2004). Again, of the

eleven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included in this

review, nine were from a residential/long-term care/hospital

setting and one was of people living in the community, and

in the other the setting was unknown. Physical training was

not defined and appeared to represent strength and balance

programs designed by physiotherapists to be conducted in

either an individual or group setting.35 Physical activity

programs such as Tai Chi, which have been shown to be

effective in reducing falls, were not included.

In summary, to date the reviews published in this area are

limited when exploring those that have specifically focused

on older PLWD in the community with exercise and/or physi-

cal activity as the intervention, and with falls as the outcome

of interest. This systematic review seeks to address this gap.

The purpose of this review is to evaluate the available evi-

dence on the effectiveness of exercise or physical activity

programs to reduce falls in older people with dementia who

are living in the community.

Method

eligibility criteria

The review is limited to studies meeting the following eli-

gibility criteria:

• aged 60 years and over (at least 50% of the sample size);

• living in the community;

• PLWD or cognitively impaired. Dementia had to have

been identified by diagnosis by a doctor/specialist, or a

validated test, such as the Mini Mental State Examination

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

423

exercise to reduce falls for community dwelling people with dementia

(MMSE), the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, or the

National Institute of Neurological and Communicative

Disorders and Stroke, Alzheimer’s Disease and Related

Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) Alzheimer’s

criteria;

• an exercise or physical activity program (intervention)

targeting a reduction in falls (and/or) risk of falls;

• outcome measures, which include number of falls, rate

of falls, or number of fallers, or time to first fall. Other

outcomes of interest were fear of having a fall, functional,

physical performance (eg, balance or mobility), or cogni-

tive benefits, or adherence to exercise/physical activity

intervention;

• study design: RCTs and quasi-experimental trials.

Information sources

Studies were identified by searching six databases (Medline

[ProQuest], CINAHL, PubMed, PsycInfo, EMBASE, and

Scopus, from January 2000 to February 2014). The search

strategy commenced from 2000, given a detailed review by

Hauer et al35 which searched across residential care, hospital,

and community settings, and did not identify any relevant

papers prior to 2003 in the community setting. In addition,

reference lists of the identified papers were scanned. Only

papers in English were included, no unpublished data,

books, conference proceedings, theses, or poster abstracts

were included.

Search strategy

The search was conducted using a mix of keywords to be

identified in the abstract and/or title of the paper or MESH

terms. The search strategy undertaken in Medline is presented

in Table 1. Each search was limited to English language

and the time period of January 1, 2000, to February 2014.

Language and syntax were adapted to individual databases:

for example, PubMed allowed title/abstract searches but not

all databases allowed this, so in these cases only the abstract

was searched.

Study selection

The study selection was conducted in three stages: stage

one involved the first author (EB) initially screening the

titles and scanning abstracts against the inclusion criteria to

identify relevant articles. This was followed (stage two) by

a full screening of the abstracts by EB. Stage three included

screening of the full articles by two of the authors (EB and

KH) to identify whether they met the eligibility criteria. Any

disagreements regarding potential inclusion were resolved by

discussion between EB and KH to achieve consensus, after

referring to the eligibility criteria and protocol.

The PRISMA checklist was used to ensure that the results

were reported systematically.36

Data collection process

Each study included in this review was evaluated, and the

following data were extracted: study design, purpose, inter-

vention, sample size, sex proportion, age of participants,

dropout rate of participants, MMSE or rating of dementia

score, number of fallers, time to first fall, fear of having a

fall, measures of balance, mobility, and function, intervention

effect, and length of follow-up.

Study quality

Methodological quality was assessed using the Cochrane

Collaboration’s risk of bias tool by two independent research-

ers (EB and KH).37 A third independent researcher completed

the risk of bias tool for one of the included studies because

of a conflict of interest for KH. 38 The categories assessed

were sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding

of participants and staff, blinding of outcome assessment,

incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and

other sources of bias.37 Risk of bias was assessed to be “low

risk”, “unclear risk”, or “high risk” of bias.37

Data analysis

The studies are described according to their characteristics,

interventions utilized, outcome measures, adherence to

exercise interventions, study quality, and effectiveness of

the intervention programs.

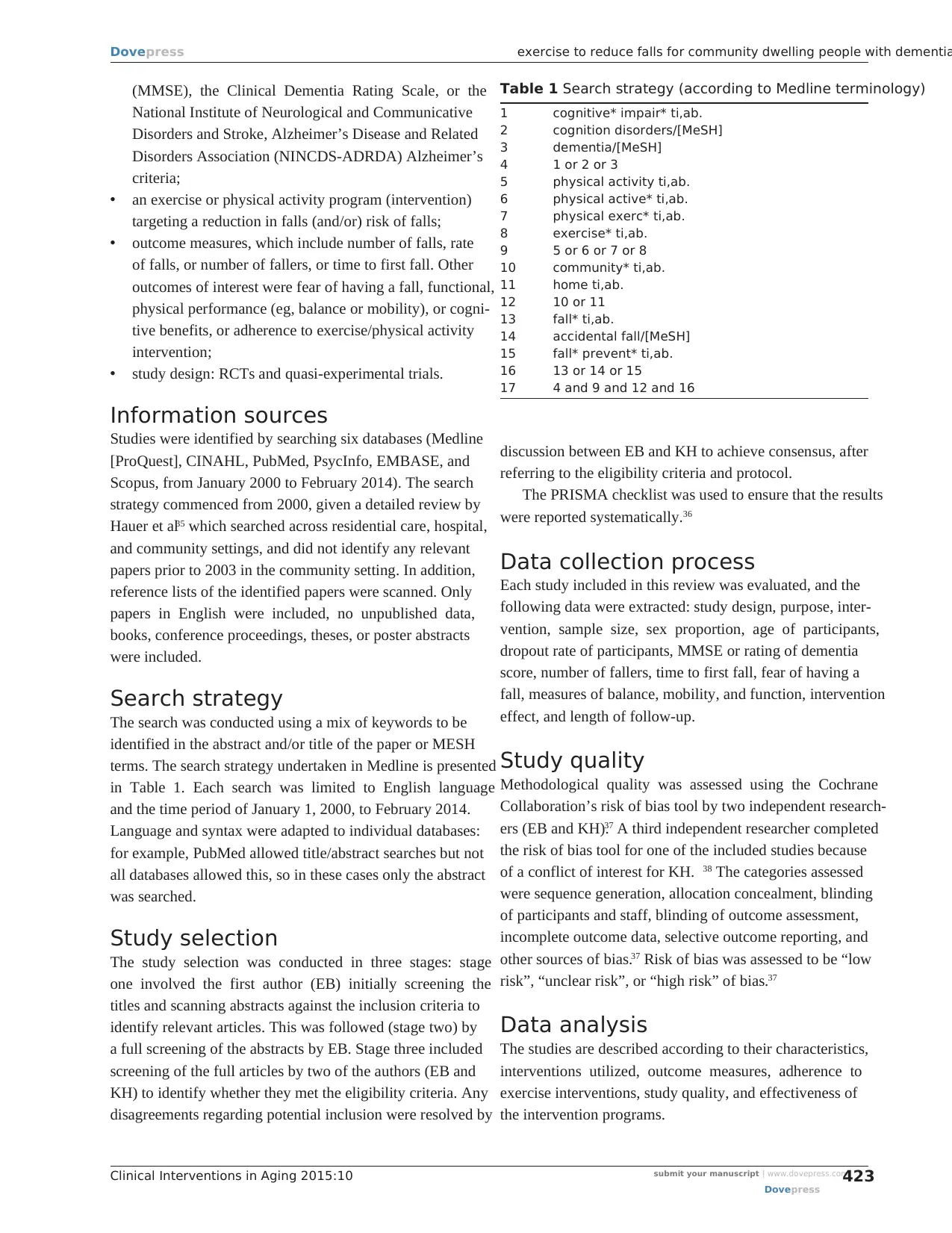

Table 1 Search strategy (according to Medline terminology)

1 cognitive* impair* ti,ab.

2 cognition disorders/[MeSH]

3 dementia/[MeSH]

4 1 or 2 or 3

5 physical activity ti,ab.

6 physical active* ti,ab.

7 physical exerc* ti,ab.

8 exercise* ti,ab.

9 5 or 6 or 7 or 8

10 community* ti,ab.

11 home ti,ab.

12 10 or 11

13 fall* ti,ab.

14 accidental fall/[MeSH]

15 fall* prevent* ti,ab.

16 13 or 14 or 15

17 4 and 9 and 12 and 16

Dovepress

Dovepress

423

exercise to reduce falls for community dwelling people with dementia

(MMSE), the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, or the

National Institute of Neurological and Communicative

Disorders and Stroke, Alzheimer’s Disease and Related

Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) Alzheimer’s

criteria;

• an exercise or physical activity program (intervention)

targeting a reduction in falls (and/or) risk of falls;

• outcome measures, which include number of falls, rate

of falls, or number of fallers, or time to first fall. Other

outcomes of interest were fear of having a fall, functional,

physical performance (eg, balance or mobility), or cogni-

tive benefits, or adherence to exercise/physical activity

intervention;

• study design: RCTs and quasi-experimental trials.

Information sources

Studies were identified by searching six databases (Medline

[ProQuest], CINAHL, PubMed, PsycInfo, EMBASE, and

Scopus, from January 2000 to February 2014). The search

strategy commenced from 2000, given a detailed review by

Hauer et al35 which searched across residential care, hospital,

and community settings, and did not identify any relevant

papers prior to 2003 in the community setting. In addition,

reference lists of the identified papers were scanned. Only

papers in English were included, no unpublished data,

books, conference proceedings, theses, or poster abstracts

were included.

Search strategy

The search was conducted using a mix of keywords to be

identified in the abstract and/or title of the paper or MESH

terms. The search strategy undertaken in Medline is presented

in Table 1. Each search was limited to English language

and the time period of January 1, 2000, to February 2014.

Language and syntax were adapted to individual databases:

for example, PubMed allowed title/abstract searches but not

all databases allowed this, so in these cases only the abstract

was searched.

Study selection

The study selection was conducted in three stages: stage

one involved the first author (EB) initially screening the

titles and scanning abstracts against the inclusion criteria to

identify relevant articles. This was followed (stage two) by

a full screening of the abstracts by EB. Stage three included

screening of the full articles by two of the authors (EB and

KH) to identify whether they met the eligibility criteria. Any

disagreements regarding potential inclusion were resolved by

discussion between EB and KH to achieve consensus, after

referring to the eligibility criteria and protocol.

The PRISMA checklist was used to ensure that the results

were reported systematically.36

Data collection process

Each study included in this review was evaluated, and the

following data were extracted: study design, purpose, inter-

vention, sample size, sex proportion, age of participants,

dropout rate of participants, MMSE or rating of dementia

score, number of fallers, time to first fall, fear of having a

fall, measures of balance, mobility, and function, intervention

effect, and length of follow-up.

Study quality

Methodological quality was assessed using the Cochrane

Collaboration’s risk of bias tool by two independent research-

ers (EB and KH).37 A third independent researcher completed

the risk of bias tool for one of the included studies because

of a conflict of interest for KH. 38 The categories assessed

were sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding

of participants and staff, blinding of outcome assessment,

incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and

other sources of bias.37 Risk of bias was assessed to be “low

risk”, “unclear risk”, or “high risk” of bias.37

Data analysis

The studies are described according to their characteristics,

interventions utilized, outcome measures, adherence to

exercise interventions, study quality, and effectiveness of

the intervention programs.

Table 1 Search strategy (according to Medline terminology)

1 cognitive* impair* ti,ab.

2 cognition disorders/[MeSH]

3 dementia/[MeSH]

4 1 or 2 or 3

5 physical activity ti,ab.

6 physical active* ti,ab.

7 physical exerc* ti,ab.

8 exercise* ti,ab.

9 5 or 6 or 7 or 8

10 community* ti,ab.

11 home ti,ab.

12 10 or 11

13 fall* ti,ab.

14 accidental fall/[MeSH]

15 fall* prevent* ti,ab.

16 13 or 14 or 15

17 4 and 9 and 12 and 16

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

424

Burton et al

Three continuous outcomes (mean falls, step test, and

physiological profile assessment [PPA]) and one dichoto-

mous outcome (faller status [ie, faller versus non-faller]) were

included in the quantitative analyses. The mean difference

(MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated

for continuous outcomes, whereas risk ratio (RR) and 95%

CI were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. The Review

Manager (RevMan) version 5.2 was used to conduct the anal-

yses and generate the forest plots, and a fixed-effect model

was applied. Heterogeneity was assessed by the I 2 statistic

and by visual inspection of the forest plots. For continuous

outcomes, the results of homogeneous studies were subjected

to meta-analysis using the inverse variance DerSimonian and

Laird method.39 For faller status (ie, dichotomous outcome),

the results of homogeneous studies were meta-analyzed using

the Mantel–Haenszel’s fixed effects model.40 Two-sided

value of P , 0.05 was the statistically significant level set

for all analyses.

In instances where data provided in the published papers

were insufficient for the meta-analysis, the corresponding

authors for the RCT papers were contacted and asked for

the total number of falls pre and post intervention, the mean

number of falls per group at post intervention, the standard

deviation, the number of fallers per group (post intervention),

and the number of participants for both groups at pre and

post data collection.

Results

Study selection

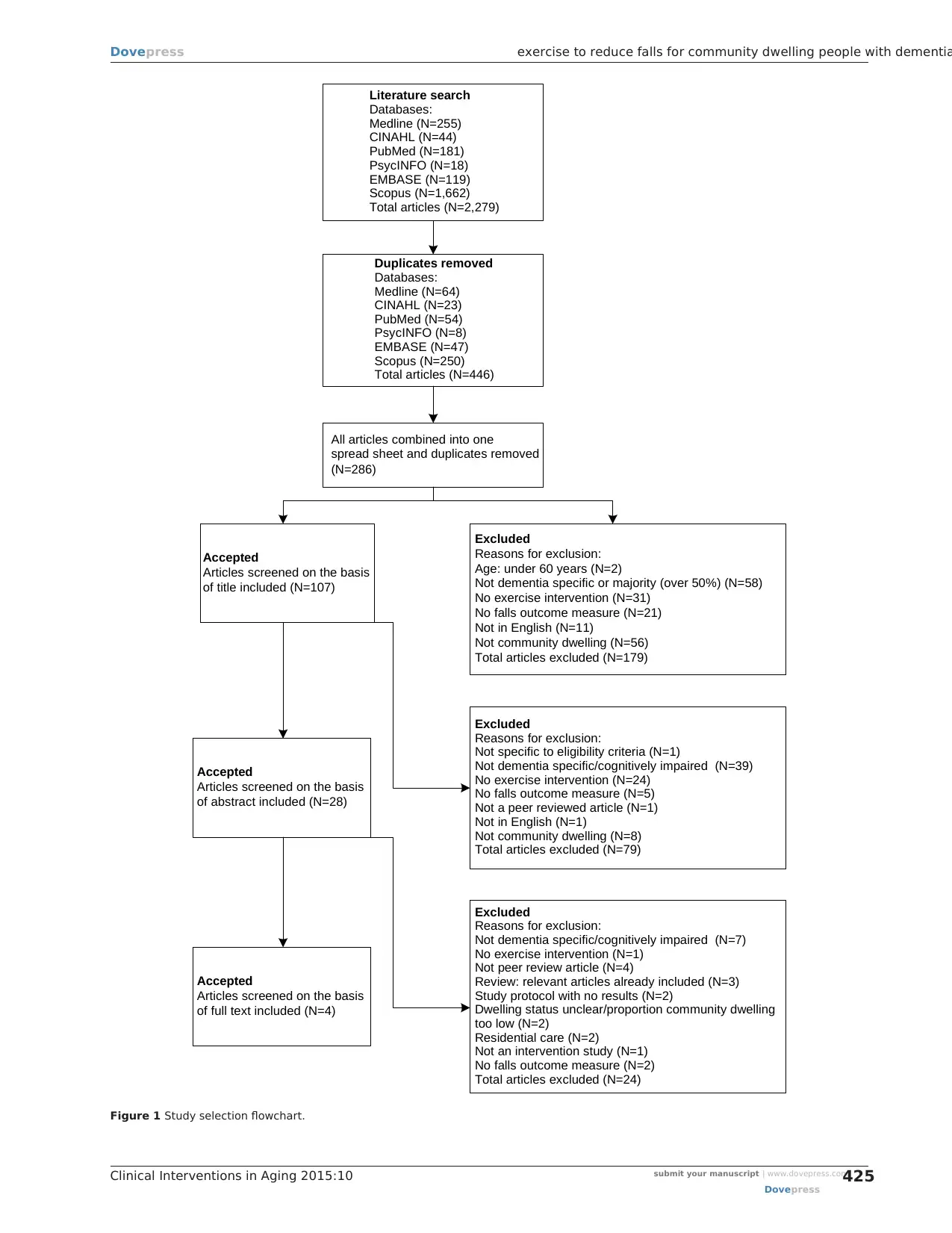

The search strategy yielded 2,279 articles from six databases.

Duplicate articles within each database were removed,

leaving 446 articles. The 446 articles were then combined

into an excel spreadsheet, with duplicates again removed,

resulting in 286 remaining articles. Articles were then

screened on the basis of title, with 179 articles excluded (rea-

sons for exclusion are reported in Figure 1). The 107 articles

were then checked, and 79 articles were excluded based

on the abstracts. The full manuscripts of the 28 remaining

articles were then examined in detail, and 24 were found not

to meet the inclusion criteria. A total of four articles were

left for inclusion in the review. Three of these were RCTs

and were included in the meta-analyses.

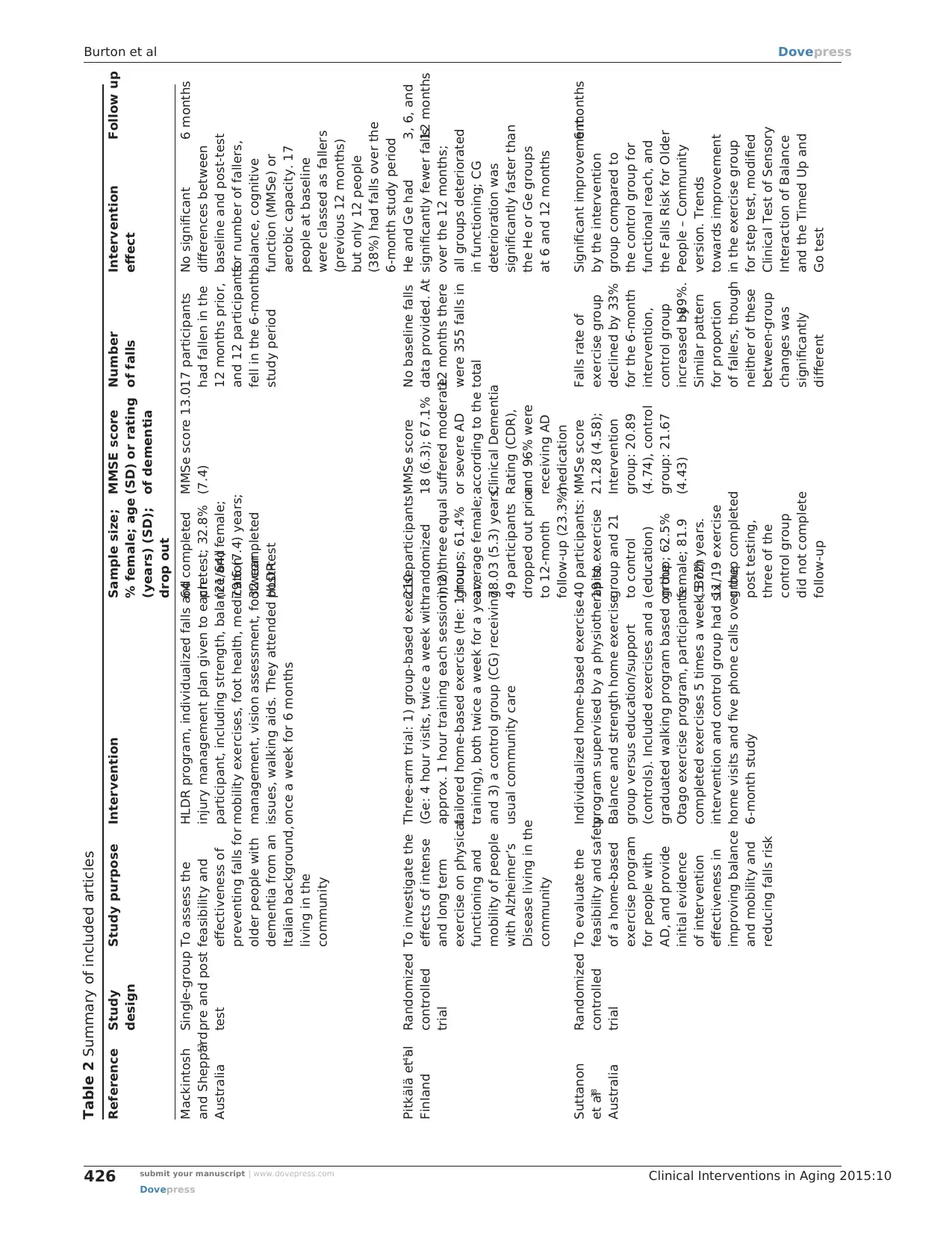

Study characteristics

Three of the four articles included in the review were

RCTs.38,41,42 The fourth was a single-group pre- and post-test

pilot study.43 As presented in Table 2, sample sizes across the

studies ranged from 2242 to 210 participants.41 Three-hundred

and thirty-six participants completed pre-testing in the four

studies, but only 243 completed post-testing (72.3%). The

largest dropout rate was found for Mackintosh and Shep-

pard’s43 study, with half of the participants not continuing

across the 6-month study period. In contrast, Wesson et al42

only had one participant from the intervention group drop

out prior to completing the 12-week intervention (95.2%

completed the follow-up assessment).

All studies included MMSE scores of participants, with an

average score (and standard deviation) of 18.9 (5.5) across all

studies. There was little difference in MMSE scores between

the intervention groups (20.4 [5.1]) and controls (20.6 [5.0])

for the three RCTs.38,41,42 All studies reported the mean age

and standard deviation; the average age of the participants

was 79.8 (5.8) years.

Interventions

Interventions ranged between 3 months and 12 months, and

participants randomized to the intervention group were rec-

ommended to complete the exercises once a week, 43 twice

a week,41 three times a week, 42 or five times a week. 38 The

exercise interventions took place in a group (or individual

assistance where required) at a facility41,43 or at home.38,41,42

Pitkälä et al’s41 study comprised three groups: group-based

exercise, home-based exercise, and usual care (control). Two

studies provided multifactorial programs, which included an

exercise component.42,43 Other interventions included in the

two studies were foot health, medication management, vision

assessments, walking aids and footwear issues,43 and home

hazard reduction.42 The exercise programs predominantly

concentrated on strength, balance, and mobility, and these

programs were established and supervised by physiothera-

pists, occupational therapists, or physiotherapy students who

were trained and supervised by physiotherapists. In two of

the studies,38,42 carers were actively involved in monitoring

and encouraging participation between therapist visits for

the assigned exercise program.

Participants in Mackintosh and Sheppard’s43 study under-

took lower limb strength exercises (hip abductor, knee exten-

sor, and ankle dorsiflexion, bilaterally) using velcro ankle

weights; balance exercises while standing, and walking was

based on time or distance. The falls risk assessment assisted

the physiotherapist to develop individual falls and injury

prevention plans for each participant. Pitkälä et al41 had two

exercise groups (home-based and group-based) with different

programs. The home exercise group was given individually

tailored exercise programs provided by a physiotherapist with

specialist dementia training and the exercises addressed the

Dovepress

Dovepress

424

Burton et al

Three continuous outcomes (mean falls, step test, and

physiological profile assessment [PPA]) and one dichoto-

mous outcome (faller status [ie, faller versus non-faller]) were

included in the quantitative analyses. The mean difference

(MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated

for continuous outcomes, whereas risk ratio (RR) and 95%

CI were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. The Review

Manager (RevMan) version 5.2 was used to conduct the anal-

yses and generate the forest plots, and a fixed-effect model

was applied. Heterogeneity was assessed by the I 2 statistic

and by visual inspection of the forest plots. For continuous

outcomes, the results of homogeneous studies were subjected

to meta-analysis using the inverse variance DerSimonian and

Laird method.39 For faller status (ie, dichotomous outcome),

the results of homogeneous studies were meta-analyzed using

the Mantel–Haenszel’s fixed effects model.40 Two-sided

value of P , 0.05 was the statistically significant level set

for all analyses.

In instances where data provided in the published papers

were insufficient for the meta-analysis, the corresponding

authors for the RCT papers were contacted and asked for

the total number of falls pre and post intervention, the mean

number of falls per group at post intervention, the standard

deviation, the number of fallers per group (post intervention),

and the number of participants for both groups at pre and

post data collection.

Results

Study selection

The search strategy yielded 2,279 articles from six databases.

Duplicate articles within each database were removed,

leaving 446 articles. The 446 articles were then combined

into an excel spreadsheet, with duplicates again removed,

resulting in 286 remaining articles. Articles were then

screened on the basis of title, with 179 articles excluded (rea-

sons for exclusion are reported in Figure 1). The 107 articles

were then checked, and 79 articles were excluded based

on the abstracts. The full manuscripts of the 28 remaining

articles were then examined in detail, and 24 were found not

to meet the inclusion criteria. A total of four articles were

left for inclusion in the review. Three of these were RCTs

and were included in the meta-analyses.

Study characteristics

Three of the four articles included in the review were

RCTs.38,41,42 The fourth was a single-group pre- and post-test

pilot study.43 As presented in Table 2, sample sizes across the

studies ranged from 2242 to 210 participants.41 Three-hundred

and thirty-six participants completed pre-testing in the four

studies, but only 243 completed post-testing (72.3%). The

largest dropout rate was found for Mackintosh and Shep-

pard’s43 study, with half of the participants not continuing

across the 6-month study period. In contrast, Wesson et al42

only had one participant from the intervention group drop

out prior to completing the 12-week intervention (95.2%

completed the follow-up assessment).

All studies included MMSE scores of participants, with an

average score (and standard deviation) of 18.9 (5.5) across all

studies. There was little difference in MMSE scores between

the intervention groups (20.4 [5.1]) and controls (20.6 [5.0])

for the three RCTs.38,41,42 All studies reported the mean age

and standard deviation; the average age of the participants

was 79.8 (5.8) years.

Interventions

Interventions ranged between 3 months and 12 months, and

participants randomized to the intervention group were rec-

ommended to complete the exercises once a week, 43 twice

a week,41 three times a week, 42 or five times a week. 38 The

exercise interventions took place in a group (or individual

assistance where required) at a facility41,43 or at home.38,41,42

Pitkälä et al’s41 study comprised three groups: group-based

exercise, home-based exercise, and usual care (control). Two

studies provided multifactorial programs, which included an

exercise component.42,43 Other interventions included in the

two studies were foot health, medication management, vision

assessments, walking aids and footwear issues,43 and home

hazard reduction.42 The exercise programs predominantly

concentrated on strength, balance, and mobility, and these

programs were established and supervised by physiothera-

pists, occupational therapists, or physiotherapy students who

were trained and supervised by physiotherapists. In two of

the studies,38,42 carers were actively involved in monitoring

and encouraging participation between therapist visits for

the assigned exercise program.

Participants in Mackintosh and Sheppard’s43 study under-

took lower limb strength exercises (hip abductor, knee exten-

sor, and ankle dorsiflexion, bilaterally) using velcro ankle

weights; balance exercises while standing, and walking was

based on time or distance. The falls risk assessment assisted

the physiotherapist to develop individual falls and injury

prevention plans for each participant. Pitkälä et al41 had two

exercise groups (home-based and group-based) with different

programs. The home exercise group was given individually

tailored exercise programs provided by a physiotherapist with

specialist dementia training and the exercises addressed the

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

425

exercise to reduce falls for community dwelling people with dementia

Figure 1 Study selection flowchart.

Literature search

Databases:

Medline (N=255)

CINAHL (N=44)

PubMed (N=181)

PsycINFO (N=18)

EMBASE (N=119)

Scopus (N=1,662)

Total articles (N=2,279)

Duplicates removed

Databases:

Medline (N=64)

CINAHL (N=23)

PubMed (N=54)

PsycINFO (N=8)

EMBASE (N=47)

Scopus (N=250)

Total articles (N=446)

All articles combined into one

spread sheet and duplicates removed

(N=286)

Accepted

Articles screened on the basis

of title included (N=107)

Excluded

Reasons for exclusion:

Age: under 60 years (N=2)

Not dementia specific or majority (over 50%) (N=58)

No exercise intervention (N=31)

No falls outcome measure (N=21)

Not in English (N=11)

Not community dwelling (N=56)

Total articles excluded (N=179)

Accepted

Articles screened on the basis

of abstract included (N=28)

Excluded

Reasons for exclusion:

Not specific to eligibility criteria (N=1)

Not dementia specific/cognitively impaired (N=39)

No exercise intervention (N=24)

No falls outcome measure (N=5)

Not a peer reviewed article (N=1)

Not in English (N=1)

Not community dwelling (N=8)

Total articles excluded (N=79)

Accepted

Articles screened on the basis

of full text included (N=4)

Excluded

Reasons for exclusion:

Not dementia specific/cognitively impaired (N=7)

No exercise intervention (N=1)

Not peer review article (N=4)

Review: relevant articles already included (N=3)

Study protocol with no results (N=2)

Dwelling status unclear/proportion community dwelling

too low (N=2)

Residential care (N=2)

Not an intervention study (N=1)

No falls outcome measure (N=2)

Total articles excluded (N=24)

Dovepress

Dovepress

425

exercise to reduce falls for community dwelling people with dementia

Figure 1 Study selection flowchart.

Literature search

Databases:

Medline (N=255)

CINAHL (N=44)

PubMed (N=181)

PsycINFO (N=18)

EMBASE (N=119)

Scopus (N=1,662)

Total articles (N=2,279)

Duplicates removed

Databases:

Medline (N=64)

CINAHL (N=23)

PubMed (N=54)

PsycINFO (N=8)

EMBASE (N=47)

Scopus (N=250)

Total articles (N=446)

All articles combined into one

spread sheet and duplicates removed

(N=286)

Accepted

Articles screened on the basis

of title included (N=107)

Excluded

Reasons for exclusion:

Age: under 60 years (N=2)

Not dementia specific or majority (over 50%) (N=58)

No exercise intervention (N=31)

No falls outcome measure (N=21)

Not in English (N=11)

Not community dwelling (N=56)

Total articles excluded (N=179)

Accepted

Articles screened on the basis

of abstract included (N=28)

Excluded

Reasons for exclusion:

Not specific to eligibility criteria (N=1)

Not dementia specific/cognitively impaired (N=39)

No exercise intervention (N=24)

No falls outcome measure (N=5)

Not a peer reviewed article (N=1)

Not in English (N=1)

Not community dwelling (N=8)

Total articles excluded (N=79)

Accepted

Articles screened on the basis

of full text included (N=4)

Excluded

Reasons for exclusion:

Not dementia specific/cognitively impaired (N=7)

No exercise intervention (N=1)

Not peer review article (N=4)

Review: relevant articles already included (N=3)

Study protocol with no results (N=2)

Dwelling status unclear/proportion community dwelling

too low (N=2)

Residential care (N=2)

Not an intervention study (N=1)

No falls outcome measure (N=2)

Total articles excluded (N=24)

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

426

Burton et al

Table 2 Summary of included articles

Reference Study

design

Study purpose Intervention Sample size;

% female; age

(years) (SD);

drop out

MMSE score

(SD) or rating

of dementia

Number

of falls

Intervention

effect

Follow up

Mackintosh

and Sheppard43

Australia

Single-group

pre and post

test

To assess the

feasibility and

effectiveness of

preventing falls for

older people with

dementia from an

Italian background,

living in the

community

HLDR program, individualized falls and

injury management plan given to each

participant, including strength, balance and

mobility exercises, foot health, medication

management, vision assessment, footwear

issues, walking aids. They attended HLDR

once a week for 6 months

64 completed

pretest; 32.8%

(21/64) female;

79.6 (7.4) years;

32 completed

post-test

MMSe score 13.0

(7.4)

17 participants

had fallen in the

12 months prior,

and 12 participants

fell in the 6-month

study period

No significant

differences between

baseline and post-test

for number of fallers,

balance, cognitive

function (MMSe) or

aerobic capacity. 17

people at baseline

were classed as fallers

(previous 12 months)

but only 12 people

(38%) had falls over the

6-month study period

6 months

Pitkälä et al41

Finland

Randomized

controlled

trial

To investigate the

effects of intense

and long term

exercise on physical

functioning and

mobility of people

with Alzheimer’s

Disease living in the

community

Three-arm trial: 1) group-based exercise

(Ge: 4 hour visits, twice a week with

approx. 1 hour training each session); 2)

tailored home-based exercise (He: 1 hour

training), both twice a week for a year;

and 3) a control group (CG) receiving

usual community care

210 participants

randomized

into three equal

groups; 61.4%

average female;

78.03 (5.3) years;

49 participants

dropped out prior

to 12-month

follow-up (23.3%)

MMSe score

18 (6.3); 67.1%

suffered moderate

or severe AD

according to the

Clinical Dementia

Rating (CDR),

and 96% were

receiving AD

medication

No baseline falls

data provided. At

12 months there

were 355 falls in

total

He and Ge had

significantly fewer falls

over the 12 months;

all groups deteriorated

in functioning; CG

deterioration was

significantly faster than

the He or Ge groups

at 6 and 12 months

3, 6, and

12 months

Suttanon

et al38

Australia

Randomized

controlled

trial

To evaluate the

feasibility and safety

of a home-based

exercise program

for people with

AD, and provide

initial evidence

of intervention

effectiveness in

improving balance

and mobility and

reducing falls risk

Individualized home-based exercise

program supervised by a physiotherapist.

Balance and strength home exercise

group versus education/support

(controls). Included exercises and a

graduated walking program based on the

Otago exercise program, participants

completed exercises 5 times a week. Both

intervention and control group had six

home visits and five phone calls over the

6-month study

40 participants:

19 to exercise

group and 21

to control

(education)

group; 62.5%

female; 81.9

(5.72) years.

11/19 exercise

group completed

post testing,

three of the

control group

did not complete

follow-up

MMSe score

21.28 (4.58);

Intervention

group: 20.89

(4.74), control

group: 21.67

(4.43)

Falls rate of

exercise group

declined by 33%

for the 6-month

intervention,

control group

increased by~89%.

Similar pattern

for proportion

of fallers, though

neither of these

between-group

changes was

significantly

different

Significant improvement

by the intervention

group compared to

the control group for

functional reach, and

the Falls Risk for Older

People – Community

version. Trends

towards improvement

in the exercise group

for step test, modified

Clinical Test of Sensory

Interaction of Balance

and the Timed Up and

Go test

6 months

Dovepress

Dovepress

426

Burton et al

Table 2 Summary of included articles

Reference Study

design

Study purpose Intervention Sample size;

% female; age

(years) (SD);

drop out

MMSE score

(SD) or rating

of dementia

Number

of falls

Intervention

effect

Follow up

Mackintosh

and Sheppard43

Australia

Single-group

pre and post

test

To assess the

feasibility and

effectiveness of

preventing falls for

older people with

dementia from an

Italian background,

living in the

community

HLDR program, individualized falls and

injury management plan given to each

participant, including strength, balance and

mobility exercises, foot health, medication

management, vision assessment, footwear

issues, walking aids. They attended HLDR

once a week for 6 months

64 completed

pretest; 32.8%

(21/64) female;

79.6 (7.4) years;

32 completed

post-test

MMSe score 13.0

(7.4)

17 participants

had fallen in the

12 months prior,

and 12 participants

fell in the 6-month

study period

No significant

differences between

baseline and post-test

for number of fallers,

balance, cognitive

function (MMSe) or

aerobic capacity. 17

people at baseline

were classed as fallers

(previous 12 months)

but only 12 people

(38%) had falls over the

6-month study period

6 months

Pitkälä et al41

Finland

Randomized

controlled

trial

To investigate the

effects of intense

and long term

exercise on physical

functioning and

mobility of people

with Alzheimer’s

Disease living in the

community

Three-arm trial: 1) group-based exercise

(Ge: 4 hour visits, twice a week with

approx. 1 hour training each session); 2)

tailored home-based exercise (He: 1 hour

training), both twice a week for a year;

and 3) a control group (CG) receiving

usual community care

210 participants

randomized

into three equal

groups; 61.4%

average female;

78.03 (5.3) years;

49 participants

dropped out prior

to 12-month

follow-up (23.3%)

MMSe score

18 (6.3); 67.1%

suffered moderate

or severe AD

according to the

Clinical Dementia

Rating (CDR),

and 96% were

receiving AD

medication

No baseline falls

data provided. At

12 months there

were 355 falls in

total

He and Ge had

significantly fewer falls

over the 12 months;

all groups deteriorated

in functioning; CG

deterioration was

significantly faster than

the He or Ge groups

at 6 and 12 months

3, 6, and

12 months

Suttanon

et al38

Australia

Randomized

controlled

trial

To evaluate the

feasibility and safety

of a home-based

exercise program

for people with

AD, and provide

initial evidence

of intervention

effectiveness in

improving balance

and mobility and

reducing falls risk

Individualized home-based exercise

program supervised by a physiotherapist.

Balance and strength home exercise

group versus education/support

(controls). Included exercises and a

graduated walking program based on the

Otago exercise program, participants

completed exercises 5 times a week. Both

intervention and control group had six

home visits and five phone calls over the

6-month study

40 participants:

19 to exercise

group and 21

to control

(education)

group; 62.5%

female; 81.9

(5.72) years.

11/19 exercise

group completed

post testing,

three of the

control group

did not complete

follow-up

MMSe score

21.28 (4.58);

Intervention

group: 20.89

(4.74), control

group: 21.67

(4.43)

Falls rate of

exercise group

declined by 33%

for the 6-month

intervention,

control group

increased by~89%.

Similar pattern

for proportion

of fallers, though

neither of these

between-group

changes was

significantly

different

Significant improvement

by the intervention

group compared to

the control group for

functional reach, and

the Falls Risk for Older

People – Community

version. Trends

towards improvement

in the exercise group

for step test, modified

Clinical Test of Sensory

Interaction of Balance

and the Timed Up and

Go test

6 months

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10 submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

427

exercise to reduce falls for community dwelling people with dementia

wesson et al42

Australia

Randomized

controlled

trial

To explore the

design and feasibility

of a novel approach

to fall prevention

for people with mild

dementia living in the

community

Strength and balance training exercises

and home hazard reduction. Six

occupational therapy home visits (and

three phone calls), five home visits from

a physiotherapist. The physio-prescribed

and progressed the exercises. exercise

intervention consisted of a maximum of

six exercises from the weBB program,

including sit to stand, calf raises, step ups

onto a block, stands with diminishing base

of support (eyes open or closed), step-

overs, foot taps onto block, lateral side

steps and sideways walking. Participants

were asked to complete the exercises

three times per week. Control group

received usual care

22 participants

randomized into

two equal groups;

40.95% female;

79.8 (4.6) years; all

controls and ten

of the intervention

group completed

follow-up

MMSe score:

23.5 (3.7)

Falls during previous

12 months: 16 falls

in total. Intervention

group had fewer

falls (n=5) than

the control group

(n=11) during the

intervention

Risk of falling and

number of falls

was lower in the

intervention group;

however neither

was significant. No

significant differences

in physiological

outcome measures

between groups

due to small sample

size and incomplete

data primarily in the

intervention group at

follow-up

3 months

(12 weeks)

Notes: Data from: Mackintosh S, Sheppard L. A pilot falls-prevention programme for older people with dementia from a predominantly Italian background. Hong Kong Phys J. 2005;23:20–26.43 Pitkälä KH, Pöysti MM, Laakkonen ML, et

al. effects of the Finnish Alzheimer’s disease exercise trial (FINALeX). JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):894–901. Copyright © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.41 Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, et al. Feasibility, safety

and preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of a home-based exercise programme for older people with Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(5):427–438.38 wesson J, Clemson L, Brodaty H, et al.

A feasibility study and pilot randomised trial of a tailored prevention program to reduce falls in older people with mild dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:89. Published by BioMed Central.42

Abbreviations: HLDR, healthy lifestyle dementia respite; SD, standard deviation; MMSe, mini mental state examination; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; He, home exercise; Ge, group exercise; CG, control group.

participant’s needs and problems regarding daily functioning

and mobility.41 Exercises included climbing stairs, balance and

transfer training, walking, dual tasking, and outdoor activities.

Equipment included exercise bikes, ankle/hand weights, balls,

canes, and balance pillows. The group exercisers undertook

predetermined exercises consisting of endurance (exercise

bikes), balance (walking in a line, training while bouncing

a ball, climbing a ladder), and strength training (specialized

weights in the gym). All exercises increased in intensity and

dosage over time and were recorded. The group ratio was ten

participants to two physiotherapists.

Suttanon et al 38 based their home exercise regimen on

the Otago exercise program, which has been shown to

reduce falls for older people living in the community.44 The

exercise program included strengthening exercises, standing

balance exercises, and a walking program, and meets the

physical activity guidelines (30 minutes at least five times

a week) recommended by the World Health Organization

and the Australian Government.45,46 Ankle weights were

used to progress the strengthening exercises over time,

and each participant also received a booklet with illustra-

tions and instructions of the exercises. A physiotherapist

conducted six home visits over the 6-month intervention

(four in the first two months) 47 to prescribe individualized

exercises based on assessment findings and to ensure that

the carer and the person with dementia understood the

exercises and safety issues, and subsequent visits were used

to monitor, modify exercises if required, and motivate the

participant. The carer supervised the exercise program on

a day-to-day basis.

Wesson et al42 utilized strength and balance exercises from

the Weight-Bearing Exercise for Better Balance (WEBB)

program.48 Up to six exercises were individually prescribed

by a physiotherapist for each participant based on their physi-

cal performance assessment. Depending on the participant’s

cognitive level, they were fully supervised, or given a written

booklet and visual cues around the home with supervision

from a carer, or completed the exercises unsupervised.42

Exercises included sit to stand, calf raises, step-ups onto a

block, stances with reduced base of support (eyes open and

closed), step-overs, foot taps onto a block, lateral sidesteps,

and sideways walking. 42 The number and intensity of the

exercises were increased as the participant progressed.

Outcome measures

There were a wide range of measurements used across the

four studies. Falls were reported as number of falls, number

of people falling, and rate of falls. Falls risk was assessed

Dovepress

Dovepress

427

exercise to reduce falls for community dwelling people with dementia

wesson et al42

Australia

Randomized

controlled

trial

To explore the

design and feasibility

of a novel approach

to fall prevention

for people with mild

dementia living in the

community

Strength and balance training exercises

and home hazard reduction. Six

occupational therapy home visits (and

three phone calls), five home visits from

a physiotherapist. The physio-prescribed

and progressed the exercises. exercise

intervention consisted of a maximum of

six exercises from the weBB program,

including sit to stand, calf raises, step ups

onto a block, stands with diminishing base

of support (eyes open or closed), step-

overs, foot taps onto block, lateral side

steps and sideways walking. Participants

were asked to complete the exercises

three times per week. Control group

received usual care

22 participants

randomized into

two equal groups;

40.95% female;

79.8 (4.6) years; all

controls and ten

of the intervention

group completed

follow-up

MMSe score:

23.5 (3.7)

Falls during previous

12 months: 16 falls

in total. Intervention

group had fewer

falls (n=5) than

the control group

(n=11) during the

intervention

Risk of falling and

number of falls

was lower in the

intervention group;

however neither

was significant. No

significant differences

in physiological

outcome measures

between groups

due to small sample

size and incomplete

data primarily in the

intervention group at

follow-up

3 months

(12 weeks)

Notes: Data from: Mackintosh S, Sheppard L. A pilot falls-prevention programme for older people with dementia from a predominantly Italian background. Hong Kong Phys J. 2005;23:20–26.43 Pitkälä KH, Pöysti MM, Laakkonen ML, et

al. effects of the Finnish Alzheimer’s disease exercise trial (FINALeX). JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):894–901. Copyright © 2013 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.41 Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, et al. Feasibility, safety

and preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of a home-based exercise programme for older people with Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(5):427–438.38 wesson J, Clemson L, Brodaty H, et al.

A feasibility study and pilot randomised trial of a tailored prevention program to reduce falls in older people with mild dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:89. Published by BioMed Central.42

Abbreviations: HLDR, healthy lifestyle dementia respite; SD, standard deviation; MMSe, mini mental state examination; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; He, home exercise; Ge, group exercise; CG, control group.

participant’s needs and problems regarding daily functioning

and mobility.41 Exercises included climbing stairs, balance and

transfer training, walking, dual tasking, and outdoor activities.

Equipment included exercise bikes, ankle/hand weights, balls,

canes, and balance pillows. The group exercisers undertook

predetermined exercises consisting of endurance (exercise

bikes), balance (walking in a line, training while bouncing

a ball, climbing a ladder), and strength training (specialized

weights in the gym). All exercises increased in intensity and

dosage over time and were recorded. The group ratio was ten

participants to two physiotherapists.

Suttanon et al 38 based their home exercise regimen on

the Otago exercise program, which has been shown to

reduce falls for older people living in the community.44 The

exercise program included strengthening exercises, standing

balance exercises, and a walking program, and meets the

physical activity guidelines (30 minutes at least five times

a week) recommended by the World Health Organization

and the Australian Government.45,46 Ankle weights were

used to progress the strengthening exercises over time,

and each participant also received a booklet with illustra-

tions and instructions of the exercises. A physiotherapist

conducted six home visits over the 6-month intervention

(four in the first two months) 47 to prescribe individualized

exercises based on assessment findings and to ensure that

the carer and the person with dementia understood the

exercises and safety issues, and subsequent visits were used

to monitor, modify exercises if required, and motivate the

participant. The carer supervised the exercise program on

a day-to-day basis.

Wesson et al42 utilized strength and balance exercises from

the Weight-Bearing Exercise for Better Balance (WEBB)

program.48 Up to six exercises were individually prescribed

by a physiotherapist for each participant based on their physi-

cal performance assessment. Depending on the participant’s

cognitive level, they were fully supervised, or given a written

booklet and visual cues around the home with supervision

from a carer, or completed the exercises unsupervised.42

Exercises included sit to stand, calf raises, step-ups onto a

block, stances with reduced base of support (eyes open and

closed), step-overs, foot taps onto a block, lateral sidesteps,

and sideways walking. 42 The number and intensity of the

exercises were increased as the participant progressed.

Outcome measures

There were a wide range of measurements used across the

four studies. Falls were reported as number of falls, number

of people falling, and rate of falls. Falls risk was assessed

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Clinical Interventions in Aging 2015:10submit your manuscript | www.dovepress.com

Dovepress

Dovepress

428

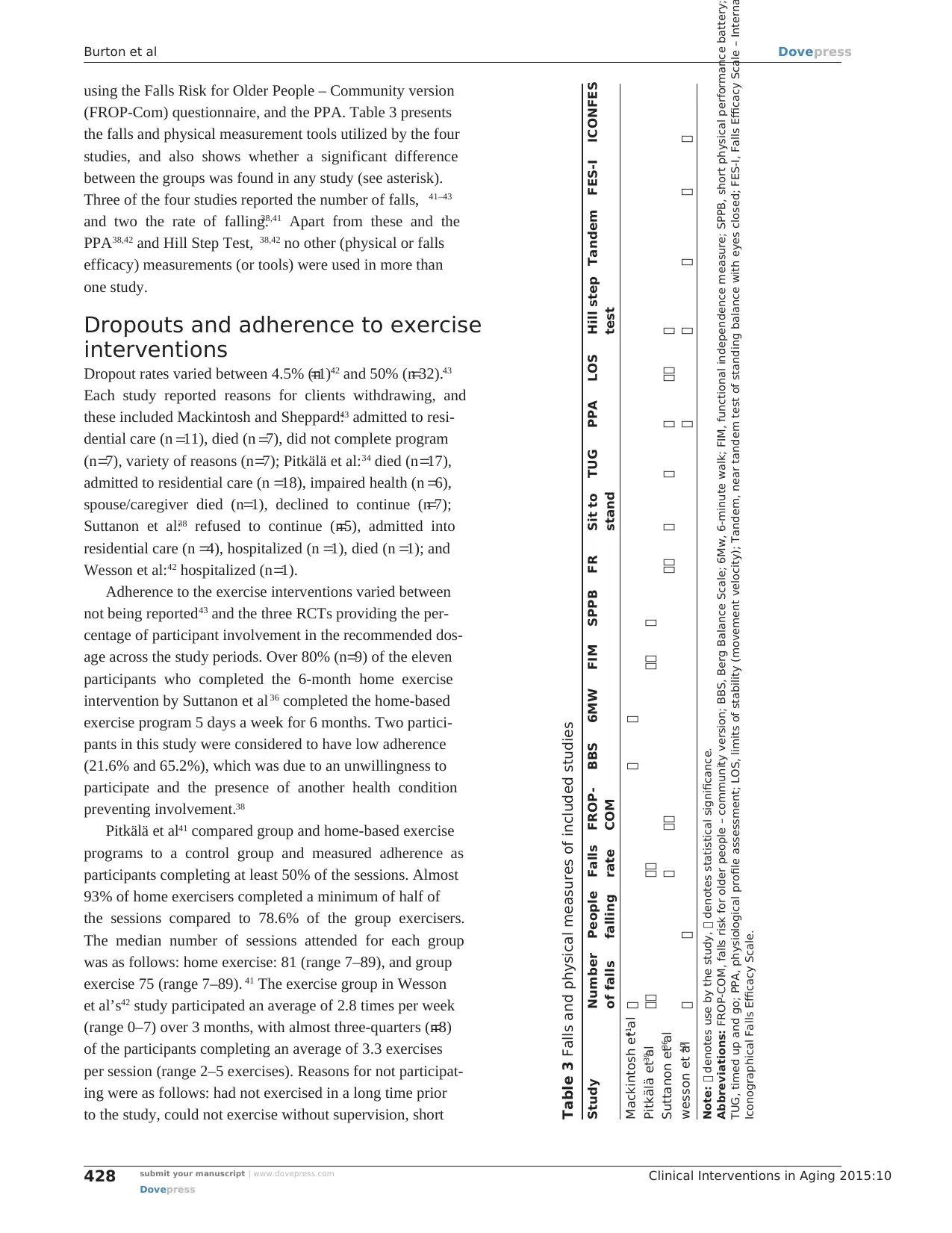

Burton et al

using the Falls Risk for Older People – Community version

(FROP-Com) questionnaire, and the PPA. Table 3 presents

the falls and physical measurement tools utilized by the four

studies, and also shows whether a significant difference

between the groups was found in any study (see asterisk).

Three of the four studies reported the number of falls, 41–43

and two the rate of falling.38,41 Apart from these and the

PPA38,42 and Hill Step Test, 38,42 no other (physical or falls

efficacy) measurements (or tools) were used in more than

one study.

Dropouts and adherence to exercise

interventions

Dropout rates varied between 4.5% (n=1)42 and 50% (n=32).43

Each study reported reasons for clients withdrawing, and

these included Mackintosh and Sheppard:43 admitted to resi-

dential care (n =11), died (n =7), did not complete program

(n=7), variety of reasons (n=7); Pitkälä et al:34 died (n=17),

admitted to residential care (n =18), impaired health (n =6),

spouse/caregiver died (n=1), declined to continue (n=7);

Suttanon et al:38 refused to continue (n=5), admitted into

residential care (n =4), hospitalized (n =1), died (n =1); and

Wesson et al:42 hospitalized (n=1).

Adherence to the exercise interventions varied between

not being reported43 and the three RCTs providing the per-

centage of participant involvement in the recommended dos-

age across the study periods. Over 80% (n=9) of the eleven

participants who completed the 6-month home exercise

intervention by Suttanon et al 36 completed the home-based

exercise program 5 days a week for 6 months. Two partici-

pants in this study were considered to have low adherence

(21.6% and 65.2%), which was due to an unwillingness to

participate and the presence of another health condition

preventing involvement.38

Pitkälä et al41 compared group and home-based exercise

programs to a control group and measured adherence as

participants completing at least 50% of the sessions. Almost

93% of home exercisers completed a minimum of half of

the sessions compared to 78.6% of the group exercisers.

The median number of sessions attended for each group

was as follows: home exercise: 81 (range 7–89), and group

exercise 75 (range 7–89). 41 The exercise group in Wesson

et al’s42 study participated an average of 2.8 times per week

(range 0–7) over 3 months, with almost three-quarters (n=8)

of the participants completing an average of 3.3 exercises

per session (range 2–5 exercises). Reasons for not participat-

ing were as follows: had not exercised in a long time prior

to the study, could not exercise without supervision, short

Table 3 Falls and physical measures of included studies

Study Number

of falls

People

falling

Falls

rate

FROP-

COM

BBS 6MW FIM SPPB FR Sit to

stand

TUG PPA LOS Hill step

test

Tandem FES-I ICONFES

Mackintosh et al41

Pitkälä et al39

Suttanon et al36

wesson et al40

Note: denotes use by the study, denotes statistical significance.

Abbreviations: FROP-COM, falls risk for older people – community version; BBS, Berg Balance Scale; 6Mw, 6-minute walk; FIM, functional independence measure; SPPB, short physical performance battery;

TUG, timed up and go; PPA, physiological profile assessment; LOS, limits of stability (movement velocity); Tandem, near tandem test of standing balance with eyes closed; FES-I, Falls Efficacy Scale – Interna

Iconographical Falls Efficacy Scale.

Dovepress

Dovepress

428

Burton et al

using the Falls Risk for Older People – Community version

(FROP-Com) questionnaire, and the PPA. Table 3 presents

the falls and physical measurement tools utilized by the four

studies, and also shows whether a significant difference

between the groups was found in any study (see asterisk).

Three of the four studies reported the number of falls, 41–43

and two the rate of falling.38,41 Apart from these and the

PPA38,42 and Hill Step Test, 38,42 no other (physical or falls

efficacy) measurements (or tools) were used in more than

one study.

Dropouts and adherence to exercise

interventions

Dropout rates varied between 4.5% (n=1)42 and 50% (n=32).43

Each study reported reasons for clients withdrawing, and

these included Mackintosh and Sheppard:43 admitted to resi-

dential care (n =11), died (n =7), did not complete program

(n=7), variety of reasons (n=7); Pitkälä et al:34 died (n=17),

admitted to residential care (n =18), impaired health (n =6),

spouse/caregiver died (n=1), declined to continue (n=7);

Suttanon et al:38 refused to continue (n=5), admitted into

residential care (n =4), hospitalized (n =1), died (n =1); and

Wesson et al:42 hospitalized (n=1).

Adherence to the exercise interventions varied between

not being reported43 and the three RCTs providing the per-

centage of participant involvement in the recommended dos-

age across the study periods. Over 80% (n=9) of the eleven

participants who completed the 6-month home exercise

intervention by Suttanon et al 36 completed the home-based

exercise program 5 days a week for 6 months. Two partici-

pants in this study were considered to have low adherence

(21.6% and 65.2%), which was due to an unwillingness to

participate and the presence of another health condition

preventing involvement.38

Pitkälä et al41 compared group and home-based exercise

programs to a control group and measured adherence as

participants completing at least 50% of the sessions. Almost

93% of home exercisers completed a minimum of half of

the sessions compared to 78.6% of the group exercisers.

The median number of sessions attended for each group

was as follows: home exercise: 81 (range 7–89), and group

exercise 75 (range 7–89). 41 The exercise group in Wesson

et al’s42 study participated an average of 2.8 times per week

(range 0–7) over 3 months, with almost three-quarters (n=8)

of the participants completing an average of 3.3 exercises

per session (range 2–5 exercises). Reasons for not participat-

ing were as follows: had not exercised in a long time prior

to the study, could not exercise without supervision, short

Table 3 Falls and physical measures of included studies

Study Number

of falls

People

falling

Falls

rate

FROP-

COM

BBS 6MW FIM SPPB FR Sit to

stand

TUG PPA LOS Hill step

test

Tandem FES-I ICONFES

Mackintosh et al41

Pitkälä et al39

Suttanon et al36

wesson et al40

Note: denotes use by the study, denotes statistical significance.

Abbreviations: FROP-COM, falls risk for older people – community version; BBS, Berg Balance Scale; 6Mw, 6-minute walk; FIM, functional independence measure; SPPB, short physical performance battery;