U22011 Structural Integrity Coursework: Fan Blade & Piping Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/22

|21

|4028

|13

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a structural integrity assessment, divided into two parts. Part A focuses on the damage tolerance analysis of an aero-engine fan blade made of Ti-6Al-4V alloy, employing fracture mechanics principles to evaluate potential failure causes under various stress conditions, including fatigue crack growth predictions using the Paris law. Part B investigates the life assessment of a steam power plant header piping system, emphasizing creep as the primary life-limiting factor for low-alloyed ferritic steels at high temperatures. The report explores both post-service examination and operational parameter approaches for creep life prediction, examining the effects of material properties and operational stresses on component lifespan. The analysis includes calculations, discussions, and conclusions regarding inspection schedules and the importance of damage tolerance analysis for ensuring the safety and reliability of aircraft and power plant components. The report emphasizes the importance of material selection, inspection frequency, and the application of fracture mechanics and creep analysis in engineering design and maintenance.

Surname 1

Student Name

Professors Name

Course Title

Date

Part A: Fan Blade Damage Tolerance Analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Aircraft components are usually made of super-alloys with outstanding strengths to improve their

reliability during the service operation. However, different factors affect the life of these

components, such as service-induced degradation and material defects during manufacturing.

The fan blades of an aero-engine have severe operating conditions that influence their life. They

undergo high mechanical stresses from vibratory, centrifugal, and flexural stresses and high

thermal stresses from the high temperature in their operating environment [1].

Damage tolerance analysis must be performed to identify the possible causes of fan-blade failure.

Metallurgical examinations and mechanical analyses are both integrated in investigating the

aero-engine fan blade damage tolerance. The low-cyclic fatigue (LCF) and high-cyclic fatigue

(HCF) damages are considered in combination during structural integrity assessment of the fan

blades. This paper emphasizes on the analytical analysis of aero-engine’s fan blades made of Ti-

6Al-4V alloy by the use of fracture mechanics analysis principles [2].

Student Name

Professors Name

Course Title

Date

Part A: Fan Blade Damage Tolerance Analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Aircraft components are usually made of super-alloys with outstanding strengths to improve their

reliability during the service operation. However, different factors affect the life of these

components, such as service-induced degradation and material defects during manufacturing.

The fan blades of an aero-engine have severe operating conditions that influence their life. They

undergo high mechanical stresses from vibratory, centrifugal, and flexural stresses and high

thermal stresses from the high temperature in their operating environment [1].

Damage tolerance analysis must be performed to identify the possible causes of fan-blade failure.

Metallurgical examinations and mechanical analyses are both integrated in investigating the

aero-engine fan blade damage tolerance. The low-cyclic fatigue (LCF) and high-cyclic fatigue

(HCF) damages are considered in combination during structural integrity assessment of the fan

blades. This paper emphasizes on the analytical analysis of aero-engine’s fan blades made of Ti-

6Al-4V alloy by the use of fracture mechanics analysis principles [2].

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Surname 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

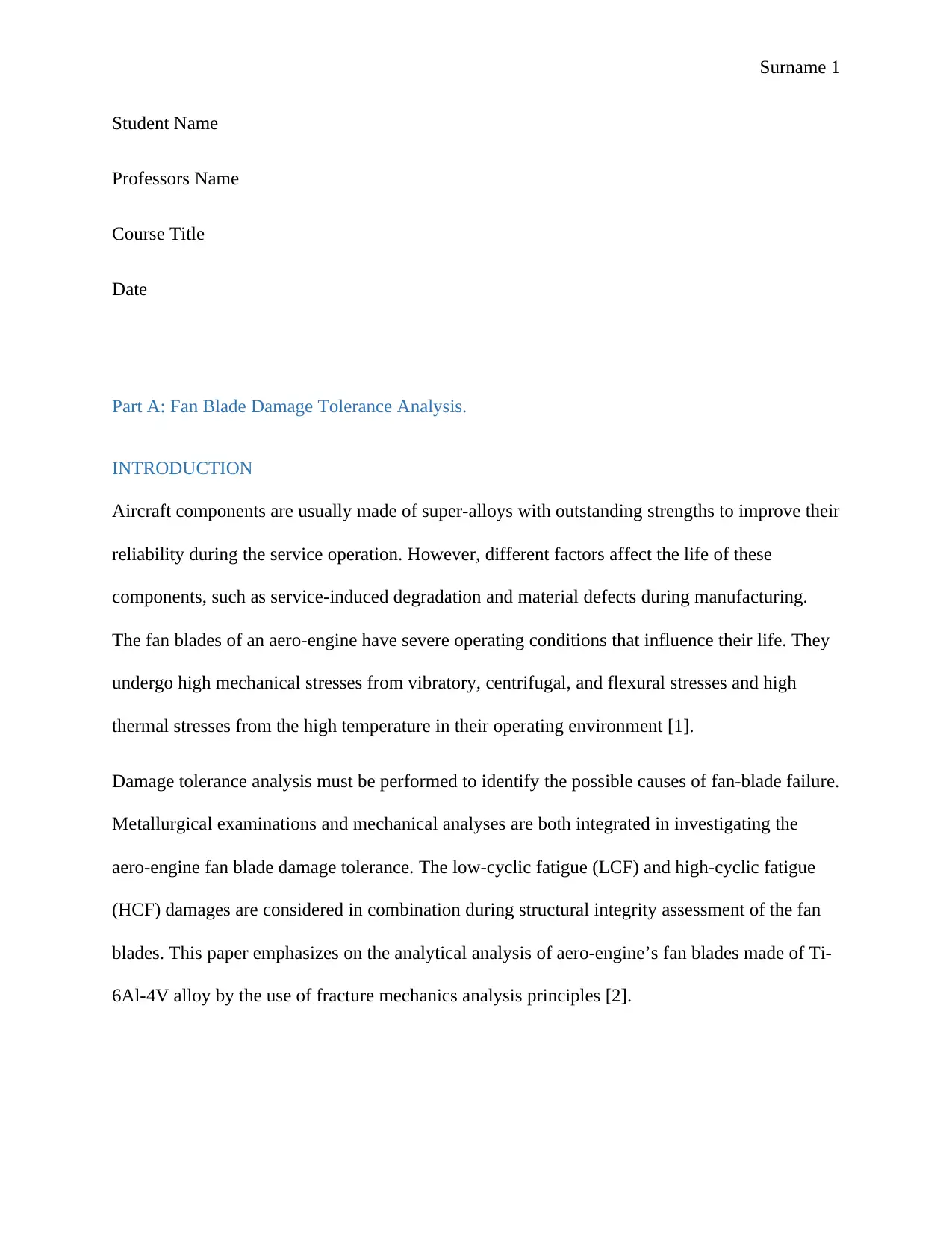

Metals exhibit damage when subjected to repeated cyclic-loading due to fatigue. The stress

magnitudes in a single load cycle may not be sufficient to cause material failure. However,

repeated cyclic loading ultimately leads to a fatigue failure. Crack initiation, followed by its

propagation under operating load, may lead to rupture when the crack exceeds a critical crack

size [3]. Aircraft components operate under variable amplitude load cycles resulting from the

changing and unpredictable wind speed and directions. Figure 1.1 presents important fatigue

terms of common types of load cycles [4].

Figure 1.1: Specification of the load cycle.

Fan blades in aero-engines

Fan blades undergo considerable mechanical and thermal loading. They are crucial components

of the aero-engine that affect the engine’s performance and reliability. Damage tolerance

LITERATURE REVIEW

Metals exhibit damage when subjected to repeated cyclic-loading due to fatigue. The stress

magnitudes in a single load cycle may not be sufficient to cause material failure. However,

repeated cyclic loading ultimately leads to a fatigue failure. Crack initiation, followed by its

propagation under operating load, may lead to rupture when the crack exceeds a critical crack

size [3]. Aircraft components operate under variable amplitude load cycles resulting from the

changing and unpredictable wind speed and directions. Figure 1.1 presents important fatigue

terms of common types of load cycles [4].

Figure 1.1: Specification of the load cycle.

Fan blades in aero-engines

Fan blades undergo considerable mechanical and thermal loading. They are crucial components

of the aero-engine that affect the engine’s performance and reliability. Damage tolerance

Surname 3

analysis of the fan blades has been the focus of research works since a fan blade failure can cause

a puncture to the engine and consequently affect the performance and safety of the aircraft [8].

The common failures in fan blades of aero-engines are due to mechanical damage, damage due

to high-temperature exposure, and creep failures. More profound knowledge and understanding

are gained on the damage tolerance of the fan blades through investigations of the crack

initiation and propagation mechanisms. High Cyclic fatigue (HCF) and Low Cycle fatigue (LCF)

failures often occur in the rotating parts, such as the fan blades [9].

Effects of small defects on fatigue thresholds.

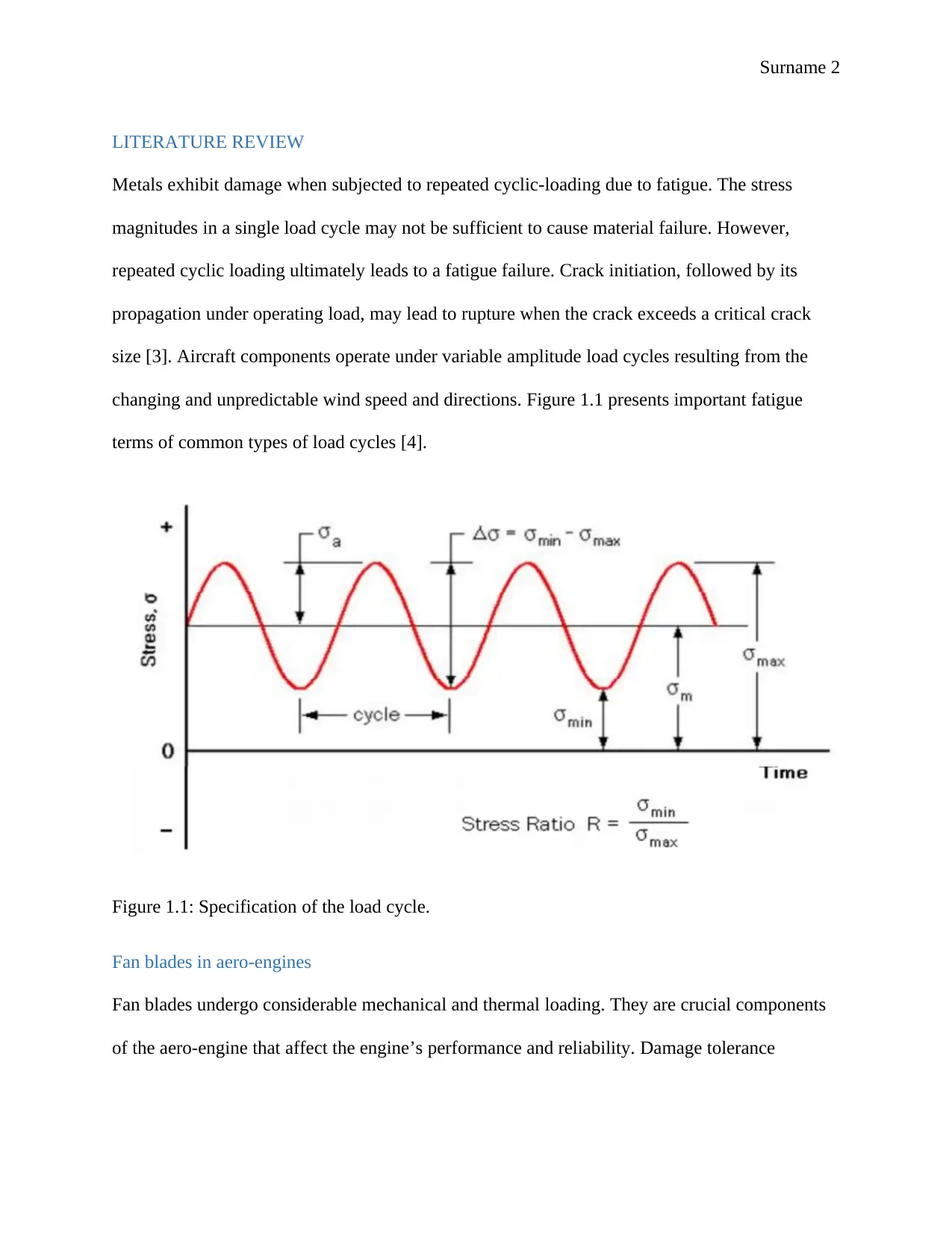

In fracture mechanics, defects in the material are considered in structural integrity assessment.

Determination of the strain release rate and the stress integrity factor is possible from the

knowledge of applied stress and the different sizes of the defects. The most commonly used

fracture mechanics method is the linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM), which is based on

Griffin’s theory of fracture [10]. Fatigue failure stages are initiation of crack, propagation of

crack growth, and, finally, catastrophic fracture. The reduction in fatigue limit as a result of

increase in the defect size of the crack is shown in figure 1.1 [11].

Figure 1.2: Fatigue versus defect size on log-log paper

analysis of the fan blades has been the focus of research works since a fan blade failure can cause

a puncture to the engine and consequently affect the performance and safety of the aircraft [8].

The common failures in fan blades of aero-engines are due to mechanical damage, damage due

to high-temperature exposure, and creep failures. More profound knowledge and understanding

are gained on the damage tolerance of the fan blades through investigations of the crack

initiation and propagation mechanisms. High Cyclic fatigue (HCF) and Low Cycle fatigue (LCF)

failures often occur in the rotating parts, such as the fan blades [9].

Effects of small defects on fatigue thresholds.

In fracture mechanics, defects in the material are considered in structural integrity assessment.

Determination of the strain release rate and the stress integrity factor is possible from the

knowledge of applied stress and the different sizes of the defects. The most commonly used

fracture mechanics method is the linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM), which is based on

Griffin’s theory of fracture [10]. Fatigue failure stages are initiation of crack, propagation of

crack growth, and, finally, catastrophic fracture. The reduction in fatigue limit as a result of

increase in the defect size of the crack is shown in figure 1.1 [11].

Figure 1.2: Fatigue versus defect size on log-log paper

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Surname 4

METHODS

Damage tolerance analysis is used to devise inspection schedules based on the following criteria:

i. The assumed initial damage condition of the fan blade which in this case is assumed

as a center-cracked plate [12]

ii. The fatigue and maximum operational stresses in the fan blade that cause crack

growth from the assumed damaged condition. The fan blade is considered to

experience a uniformly distributed tensile stress.

iii. The fan blade geometry.

iv. Critical crack size beyond which catastrophic failure occurs.

v. Acceptable level of risk [13]

Material properties and fatigue calculations

The Ti-6Al-4V alloy is composed of Ti (89.137 wt%), Al(6.30 %), Fe(0.19 %), N(0.013 %),

O(0.19 %) and V(4.17 %). From the ASM material datasheet, Ti6-4 has a fatigue strength of 240

MPa at stress concentration factor of Kt=5.3. Considering that the blade is modelled as a

rectangular plate of width, W equals 500mm and defect size, 2a of 0.5mm, the following stress

calculations can be made [14].

Maximum stress acting on the blade:

σ =σ d ± σb

Where σ d is the direct stress and σ b is the bending stress given by

σ d= P

Amin

; σ b=± P . e

I y ; y being distance starting at a neutral point.

METHODS

Damage tolerance analysis is used to devise inspection schedules based on the following criteria:

i. The assumed initial damage condition of the fan blade which in this case is assumed

as a center-cracked plate [12]

ii. The fatigue and maximum operational stresses in the fan blade that cause crack

growth from the assumed damaged condition. The fan blade is considered to

experience a uniformly distributed tensile stress.

iii. The fan blade geometry.

iv. Critical crack size beyond which catastrophic failure occurs.

v. Acceptable level of risk [13]

Material properties and fatigue calculations

The Ti-6Al-4V alloy is composed of Ti (89.137 wt%), Al(6.30 %), Fe(0.19 %), N(0.013 %),

O(0.19 %) and V(4.17 %). From the ASM material datasheet, Ti6-4 has a fatigue strength of 240

MPa at stress concentration factor of Kt=5.3. Considering that the blade is modelled as a

rectangular plate of width, W equals 500mm and defect size, 2a of 0.5mm, the following stress

calculations can be made [14].

Maximum stress acting on the blade:

σ =σ d ± σb

Where σ d is the direct stress and σ b is the bending stress given by

σ d= P

Amin

; σ b=± P . e

I y ; y being distance starting at a neutral point.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Surname 5

Amin=W × a=500 × 0.5

2 =125 m m2 from the given dimensions [15].

y

I = 60

W 2 t = 60

5002 × 0.5

2

=9.6 ×10−4

for Ti-6Al-4V alloy.

Assuming a load of P=5 kN, the direct and the bending stress can be calculated as:

σ d= 5000

125 =40 MPa

And

σ b=± P. e ( y

I )= (5000 × 0.25 ) × 9.6 ×10−4=1.2 MPa

σ =40+1.2=41.2 MPa

Since the blade is considered to be center-cracked, high stress concentrations exist near the

notch. Maximum stress at the notch is obtained from the acting stress on the fan blade and the

stress concentration factor, Kt [16].

σ max=kt σ

σ max=5.3 × 41.2=218.36 MPa

The alternating stress, sn is given by:

sn=a Nb

Where a and b are constants for the Ti-6Al-4V alloy and N are the cycles number.

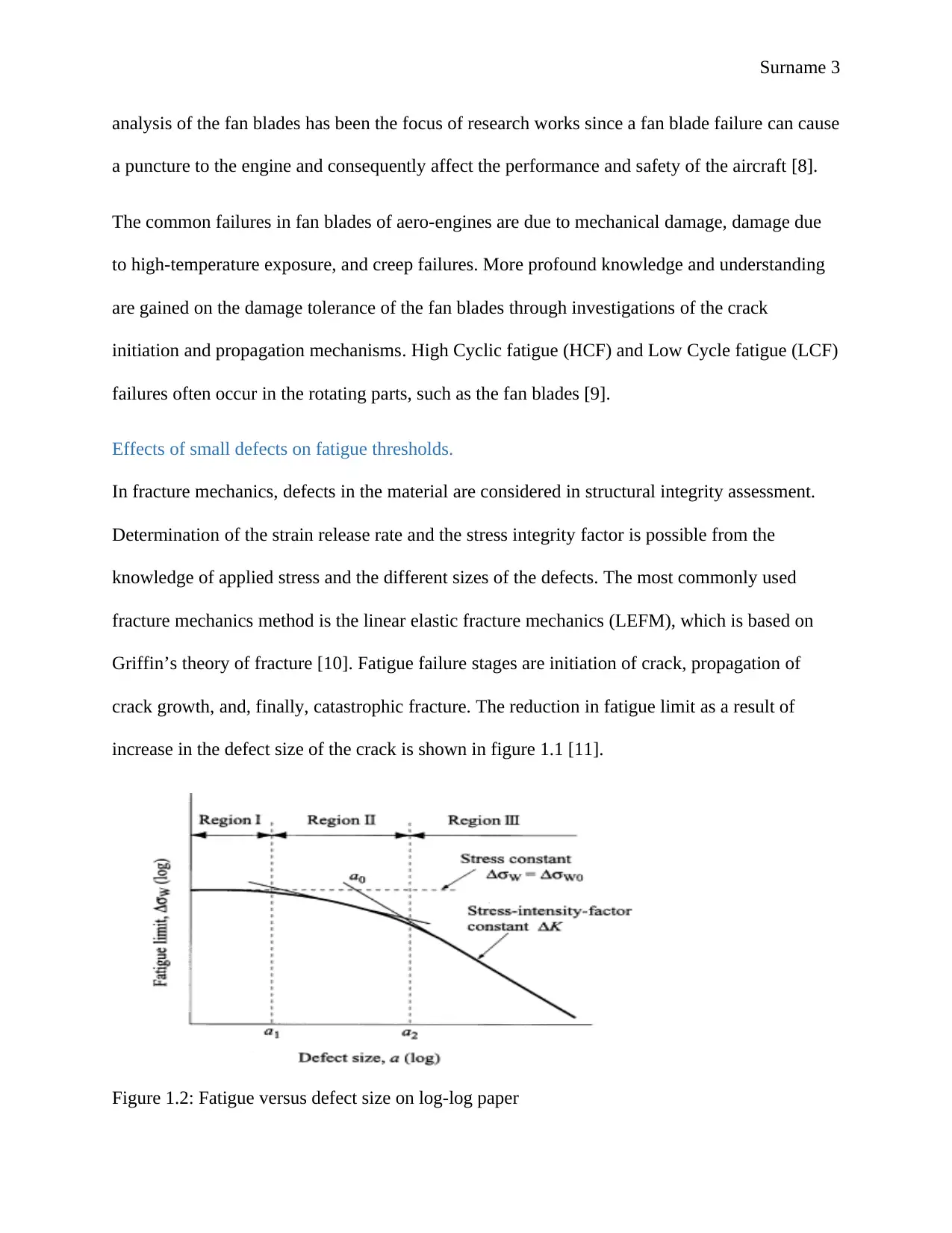

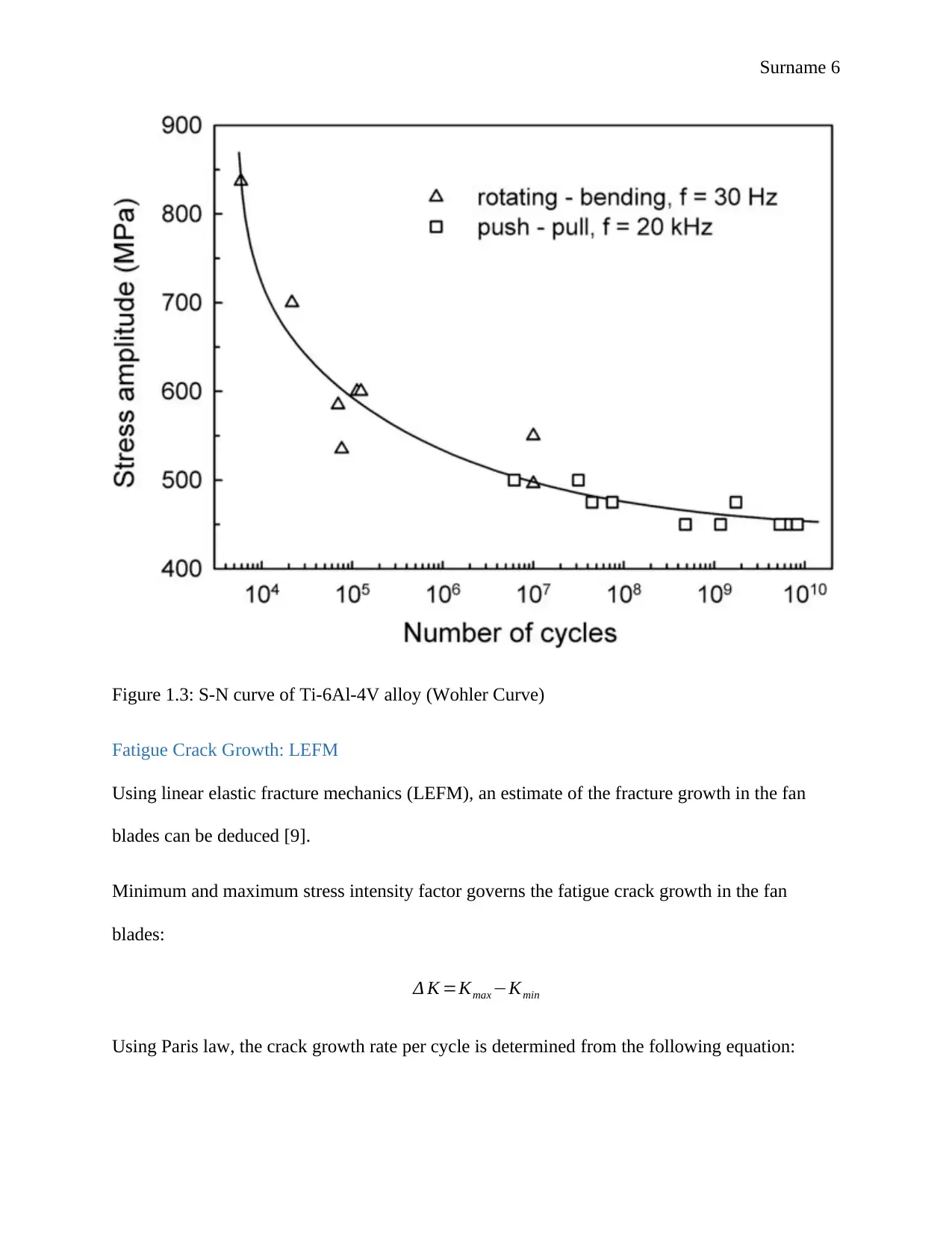

The figure 1.3 below shows the curve of stress against number of cycles for Ti6-4 material used.

Amin=W × a=500 × 0.5

2 =125 m m2 from the given dimensions [15].

y

I = 60

W 2 t = 60

5002 × 0.5

2

=9.6 ×10−4

for Ti-6Al-4V alloy.

Assuming a load of P=5 kN, the direct and the bending stress can be calculated as:

σ d= 5000

125 =40 MPa

And

σ b=± P. e ( y

I )= (5000 × 0.25 ) × 9.6 ×10−4=1.2 MPa

σ =40+1.2=41.2 MPa

Since the blade is considered to be center-cracked, high stress concentrations exist near the

notch. Maximum stress at the notch is obtained from the acting stress on the fan blade and the

stress concentration factor, Kt [16].

σ max=kt σ

σ max=5.3 × 41.2=218.36 MPa

The alternating stress, sn is given by:

sn=a Nb

Where a and b are constants for the Ti-6Al-4V alloy and N are the cycles number.

The figure 1.3 below shows the curve of stress against number of cycles for Ti6-4 material used.

Surname 6

Figure 1.3: S-N curve of Ti-6Al-4V alloy (Wohler Curve)

Fatigue Crack Growth: LEFM

Using linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM), an estimate of the fracture growth in the fan

blades can be deduced [9].

Minimum and maximum stress intensity factor governs the fatigue crack growth in the fan

blades:

Δ K =Kmax −Kmin

Using Paris law, the crack growth rate per cycle is determined from the following equation:

Figure 1.3: S-N curve of Ti-6Al-4V alloy (Wohler Curve)

Fatigue Crack Growth: LEFM

Using linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM), an estimate of the fracture growth in the fan

blades can be deduced [9].

Minimum and maximum stress intensity factor governs the fatigue crack growth in the fan

blades:

Δ K =Kmax −Kmin

Using Paris law, the crack growth rate per cycle is determined from the following equation:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Surname 7

da

dN =C ( Δ K )m

Where the Paris law parameters (C, m) are unique for any particular material.

ANALYSIS

From the methodology, the maximum stress that the fan blade with the provided dimensions is

subjected to is 218.36 MPa assuming a combined load contribution of 5 kN from the vibrational

and centrifugal forces. An operational cyclic stress range of -30 to 220 MPa will cause a fatigue

fracture growth in the fan blade since its maximum stress falls within this range. Increasing the

maximum stress by 50% means [2]:

New maximum stress=1.5× 218.36=327.54 MPa

With the same stress range, fatigue crack growth occurs much faster since 327.54 MPa is much

higher than the cyclic stress range.

If the fan blade sustains a 5 times overload of the nominal stress, the following calculations can

be made [8]:

P=5 × 5000=25000 N

σ d= 25000

125 =200 MPa

And σ b=± P. e ( y

I )= (25000 × 0.25 ) × 9.6 ×10−4=6 MPa

σ =200+6=206 MPa σ max=5.3 × 206=1091.8 MPa

The component will not be strong enough to sustain a 5-times overload.

da

dN =C ( Δ K )m

Where the Paris law parameters (C, m) are unique for any particular material.

ANALYSIS

From the methodology, the maximum stress that the fan blade with the provided dimensions is

subjected to is 218.36 MPa assuming a combined load contribution of 5 kN from the vibrational

and centrifugal forces. An operational cyclic stress range of -30 to 220 MPa will cause a fatigue

fracture growth in the fan blade since its maximum stress falls within this range. Increasing the

maximum stress by 50% means [2]:

New maximum stress=1.5× 218.36=327.54 MPa

With the same stress range, fatigue crack growth occurs much faster since 327.54 MPa is much

higher than the cyclic stress range.

If the fan blade sustains a 5 times overload of the nominal stress, the following calculations can

be made [8]:

P=5 × 5000=25000 N

σ d= 25000

125 =200 MPa

And σ b=± P. e ( y

I )= (25000 × 0.25 ) × 9.6 ×10−4=6 MPa

σ =200+6=206 MPa σ max=5.3 × 206=1091.8 MPa

The component will not be strong enough to sustain a 5-times overload.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Surname 8

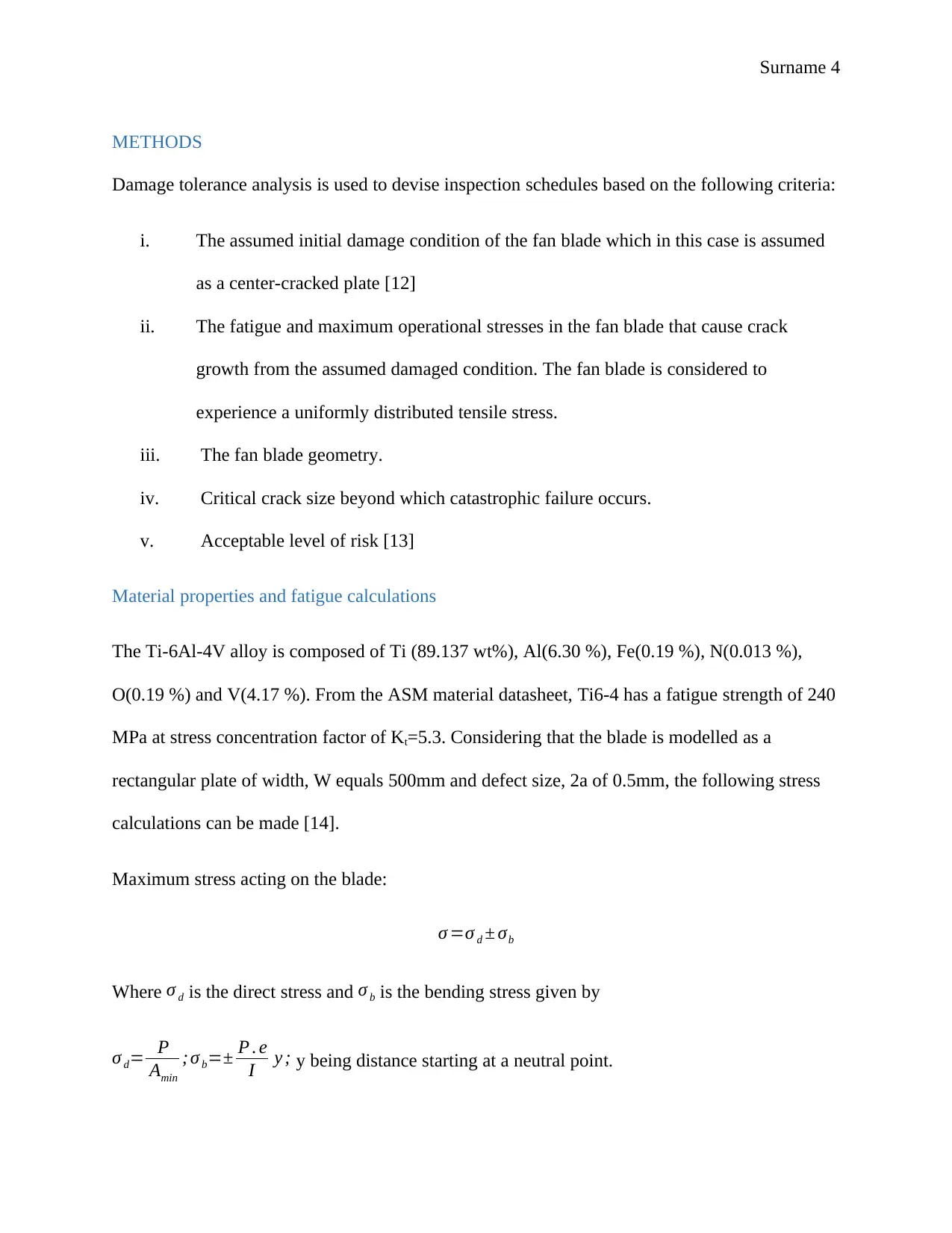

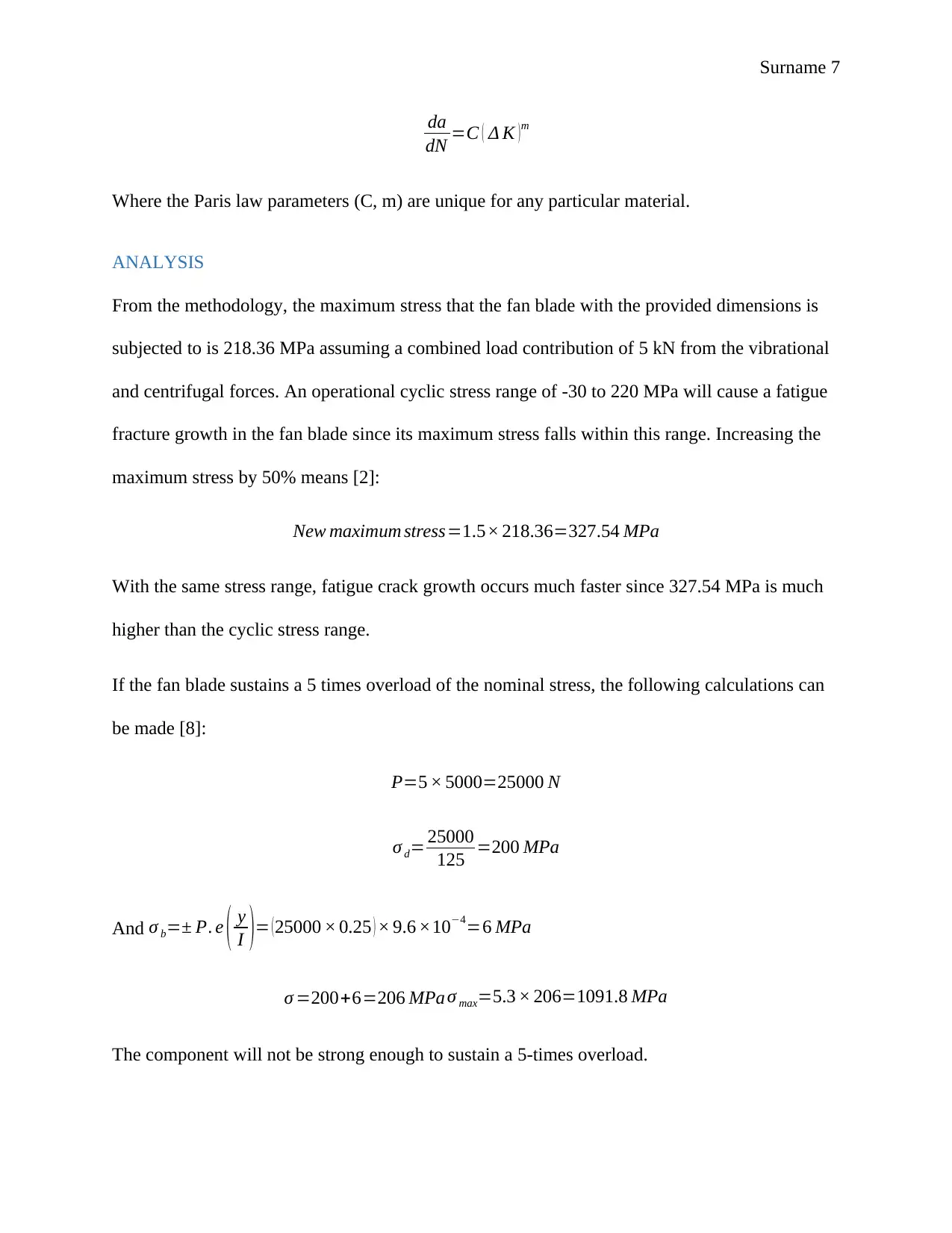

The fan blades fatigue life predictions can be determined by the HCF data for Ti-6Al-4V I shown

in the graphs of figure 1.4 [13]

Figure 1.4: Fan fatigue life predictions from maximum stress.

For a stress range of 0-220 MPa of the base loading cycle, the maximum stress used from fatigue

life prediction is 220MPa. At 220 MPa, the fatigue life of Ti6-4 is 22000 hours from figure 1.4.

Inspections are scheduled at 70% of the predicted life is given by:

tinspect=0.7 ×22,000=154 00 hours

Introduction of a minor vibrational cycle of 200-240 MPa to superimpose the major stress cycle

of the fan blade leads to more frequent scheduled inspections due to the reduction of component

predicted life. The maximum stress for this combination is 240 MPa and the corresponding

predicted lie of 16000 hours from figure 1.4. The new inspection period is:

The fan blades fatigue life predictions can be determined by the HCF data for Ti-6Al-4V I shown

in the graphs of figure 1.4 [13]

Figure 1.4: Fan fatigue life predictions from maximum stress.

For a stress range of 0-220 MPa of the base loading cycle, the maximum stress used from fatigue

life prediction is 220MPa. At 220 MPa, the fatigue life of Ti6-4 is 22000 hours from figure 1.4.

Inspections are scheduled at 70% of the predicted life is given by:

tinspect=0.7 ×22,000=154 00 hours

Introduction of a minor vibrational cycle of 200-240 MPa to superimpose the major stress cycle

of the fan blade leads to more frequent scheduled inspections due to the reduction of component

predicted life. The maximum stress for this combination is 240 MPa and the corresponding

predicted lie of 16000 hours from figure 1.4. The new inspection period is:

Surname 9

tinspect=0.7 ×16 , 000=11200 hours

Small scale yielding (SSY) conditions are met for all stress conditions and the Ti6-4 material

will eventually yield under the calculated stress cases [4]

DISCUSSION

As from the analysis above, the small-scale yielding (SSY) conditions are met since the stress

ranges needed for crack growth initiation is quite low. This can be attributed to the large initial

defect size of the fan blade crack as well as the assumption that the component can be modelled

as a rectangular center-cracked plate [16].

Material choices for fan blade are based on their ductility, yield strength, HCF strength and

damage tolerance. The trade-off amongst the aerodynamic efficiency, weight and cost present a

main challenge of fan blade material selection. Titanium-based alloys have been employed in the

fan blade design and manufacturing for large turbofan engine equipment due to their good

performance such as unique physical, corrosion and mechanical properties as seen in this paper.

Its availability, ease of fabrication and intrinsic metallurgical properties gives it an edge over

other materials. However, titanium is very expensive compared to the potential materials that

can be used for the fan blades [15].

Metal matrix composite (MMC) materials are finding application for fan blades due to the high

strength-to-density and stiffness-to-density ratios that they offer. Fan blades made from

composite materials are lighter and contribute to the overall weight savings of the engine. Lower

stresses and centrifugal loads can be achieved and is beneficial in increasing the fatigue strength

of the fan blade. However, MMC materials are too expensive for wide application of fan blade

manufacturing [15].

tinspect=0.7 ×16 , 000=11200 hours

Small scale yielding (SSY) conditions are met for all stress conditions and the Ti6-4 material

will eventually yield under the calculated stress cases [4]

DISCUSSION

As from the analysis above, the small-scale yielding (SSY) conditions are met since the stress

ranges needed for crack growth initiation is quite low. This can be attributed to the large initial

defect size of the fan blade crack as well as the assumption that the component can be modelled

as a rectangular center-cracked plate [16].

Material choices for fan blade are based on their ductility, yield strength, HCF strength and

damage tolerance. The trade-off amongst the aerodynamic efficiency, weight and cost present a

main challenge of fan blade material selection. Titanium-based alloys have been employed in the

fan blade design and manufacturing for large turbofan engine equipment due to their good

performance such as unique physical, corrosion and mechanical properties as seen in this paper.

Its availability, ease of fabrication and intrinsic metallurgical properties gives it an edge over

other materials. However, titanium is very expensive compared to the potential materials that

can be used for the fan blades [15].

Metal matrix composite (MMC) materials are finding application for fan blades due to the high

strength-to-density and stiffness-to-density ratios that they offer. Fan blades made from

composite materials are lighter and contribute to the overall weight savings of the engine. Lower

stresses and centrifugal loads can be achieved and is beneficial in increasing the fatigue strength

of the fan blade. However, MMC materials are too expensive for wide application of fan blade

manufacturing [15].

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Surname 10

Hybrid metallic materials have improved structural strengths and are becoming popular in fan

blade fabrication. They provide both weight and structural benefits by combining the structural

stiffness of titanium and the lightness of the composite design materials. Use of hybrid-metallic

materials reduces the costs of construction and increases engine’s tolerance to bird impact

strikes. However, these materials are not durable and a life assessment is required more

frequently [13].

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the fracture mechanics analysis of the aero-engine’s fan blade was performed with

consideration of thermal and mechanical forces. The nonlinearities that exist in the fan blade

structure forced an assumption of a center-cracked plate to be made. Using Paris-Erdogan law,

the values of stress integrity factor was obtained from the crack growth curves as a show under

the methodology. Information obtained from the crack growth was used to determine the period

between scheduled technical engine inspections. The damage tolerance analysis is useful in

detecting the crack growth before it reaches a critical size to avoid catastrophic rupture. It is

recommended that damage tolerance analysis be frequently done, not only to the fan blades but

also other components of the aircraft to ensure safety of the flight.

Hybrid metallic materials have improved structural strengths and are becoming popular in fan

blade fabrication. They provide both weight and structural benefits by combining the structural

stiffness of titanium and the lightness of the composite design materials. Use of hybrid-metallic

materials reduces the costs of construction and increases engine’s tolerance to bird impact

strikes. However, these materials are not durable and a life assessment is required more

frequently [13].

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the fracture mechanics analysis of the aero-engine’s fan blade was performed with

consideration of thermal and mechanical forces. The nonlinearities that exist in the fan blade

structure forced an assumption of a center-cracked plate to be made. Using Paris-Erdogan law,

the values of stress integrity factor was obtained from the crack growth curves as a show under

the methodology. Information obtained from the crack growth was used to determine the period

between scheduled technical engine inspections. The damage tolerance analysis is useful in

detecting the crack growth before it reaches a critical size to avoid catastrophic rupture. It is

recommended that damage tolerance analysis be frequently done, not only to the fan blades but

also other components of the aircraft to ensure safety of the flight.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Surname 11

Part B: Life Assessment of Steam Power Plant Header Piping System

INTRODUCTION

In modern power plants, low-alloyed ferritic steels are in extensive use for high temperature

applications. The steels are used for high-temperature components such as steam pipes and

headers in power generation plants due to their good resistance to hydrogen embrittlement and

oxidation together with good elevated temperature creep strength. Considering that the typical

stress and operating temperature in the power plant are about 50 MPa and 5500C respectively, the

main life-limiting factor of the steam pipes and headers is creep [17].

Reduction in the mechanical properties of the materials necessitates plant integrity assessment in

order to reach a definite design life of the components. Oftentimes, component replacement may

be necessary even before the design life. The remaining life assessment of the high-temperature

components is thus needed from both safety and economic perspectives. Two approaches will be

explored in creep life prediction; post-service examination approach and operational parameter

approach [18].

Part B: Life Assessment of Steam Power Plant Header Piping System

INTRODUCTION

In modern power plants, low-alloyed ferritic steels are in extensive use for high temperature

applications. The steels are used for high-temperature components such as steam pipes and

headers in power generation plants due to their good resistance to hydrogen embrittlement and

oxidation together with good elevated temperature creep strength. Considering that the typical

stress and operating temperature in the power plant are about 50 MPa and 5500C respectively, the

main life-limiting factor of the steam pipes and headers is creep [17].

Reduction in the mechanical properties of the materials necessitates plant integrity assessment in

order to reach a definite design life of the components. Oftentimes, component replacement may

be necessary even before the design life. The remaining life assessment of the high-temperature

components is thus needed from both safety and economic perspectives. Two approaches will be

explored in creep life prediction; post-service examination approach and operational parameter

approach [18].

Surname 12

LITERATURE REVIEW

Use of low-alloyed steels in steam plant piping system

Low-alloyed steels have been used for high-temperature applications since the development of

the first low Chromium (Cr) and Molybdenum (Mo) steels just after the First World War. Later,

Vanadium (V) was appreciated due to its beneficial properties on creep rupture. Power plant

pipes and tubes of the 0.5Mo-0.2V (wt %) alloy steels were the first to be installed. According to

material specifications of the ASME B31.1 standards, CMV low-alloyed steel pipe materials are

manufactured with the major alloying elements as Cr (0.5 wt %), Mo (0.5 wt %) and V(0.25 wt

%) [19]. CMV materials have uniform fine dispersion of precipitates that are distributed over the

material surface thus improving the creep strength.

Creep life prediction

Creep is the distortion of a material properties due to stresses below the material’s yield stress

when the material is exposed to high operating temperatures. The available creep life prediction

approaches for power plant components can be classified broadly into post-service examination

approach and operational approach [20].

The operational parameter approach is used to evaluate the stress history and the service

temperature of the given component. The historical data is combined with the lowest standard

value from the material data to assess the remaining life. The creep life prediction is done by the

life fraction rule as indicated in figure 2.1 [17].

Life fraction rule:

∑ t (σ ,T )

tR ( σ ,T )=1

LITERATURE REVIEW

Use of low-alloyed steels in steam plant piping system

Low-alloyed steels have been used for high-temperature applications since the development of

the first low Chromium (Cr) and Molybdenum (Mo) steels just after the First World War. Later,

Vanadium (V) was appreciated due to its beneficial properties on creep rupture. Power plant

pipes and tubes of the 0.5Mo-0.2V (wt %) alloy steels were the first to be installed. According to

material specifications of the ASME B31.1 standards, CMV low-alloyed steel pipe materials are

manufactured with the major alloying elements as Cr (0.5 wt %), Mo (0.5 wt %) and V(0.25 wt

%) [19]. CMV materials have uniform fine dispersion of precipitates that are distributed over the

material surface thus improving the creep strength.

Creep life prediction

Creep is the distortion of a material properties due to stresses below the material’s yield stress

when the material is exposed to high operating temperatures. The available creep life prediction

approaches for power plant components can be classified broadly into post-service examination

approach and operational approach [20].

The operational parameter approach is used to evaluate the stress history and the service

temperature of the given component. The historical data is combined with the lowest standard

value from the material data to assess the remaining life. The creep life prediction is done by the

life fraction rule as indicated in figure 2.1 [17].

Life fraction rule:

∑ t (σ ,T )

tR ( σ ,T )=1

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 21

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.