BUS708 - Gender Inequality and GDP: A Statistical Analysis Report

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|10

|2826

|237

Report

AI Summary

This report investigates the relationship between the gender wage gap and Australia's GDP using statistical analysis. It utilizes two datasets: one from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) providing individual salary and occupation data, and another from the OECD containing wage gap and GDP figures. The analysis includes descriptive statistics to compare gender distribution across occupations and salary levels, inferential statistics to test hypotheses about gender proportions and salary differences, and regression analysis to model the impact of the wage gap on GDP. The findings indicate a statistically significant, negative relationship, suggesting that a wider gender wage gap is associated with a reduction in GDP. The report concludes that addressing gender inequality is crucial for economic growth and provides insights relevant for policymaking and development. Desklib offers a range of similar solved assignments and resources for students.

Running Header: Gender equality in Australia 1

Gender equality in Australia

Student’s name:

Student’s ID:

Institution:

Gender equality in Australia

Student’s name:

Student’s ID:

Institution:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Gender equality in Australia 2

Section 1: Introduction

a. Introduction

The gender gap is the difference between the salary of men and that of women (Bekhouche ey al.,

2013). The gender gap is attributed to not only discrimination in hiring but also the different industries

which women and men work among others. Gender equality has been a major case of discussion by

many people across different fields globally (Grown et al., 2005). According to Schwab (2017), the

gender biases been experienced across the different field in the economy are keeping the mass from

closing the gender gap thereby causing an overwhelming of the economy.

The following research aims at finding the relationship between the gender gap and the GDP. Thus the

arising research question:

What is the a relationship between gender gap and the GDP

The research is necessitated by the fact that closing the gender gap is vital for policymaking and

development (World Bank, 2012). According to Revenga and Shetty (2012), gender equality is vital for

enhancing economic productivity, improving the outcomes of development for future generations, and

making institutional and policies more representative. Momsen (2009), states that progress is a course

which expands freedom similarly for all the people both female and male. Thus, closing gender equality

improves economic productivity and improves other outcomes of development (Hausmann, 2009).

The net impact of gender inequality on growth is quite ambiguous. In some way, gender inequality is

attributed to hindering growth or support growth circumstantially (Galor and Moav, 2004). Income and

wages rapidly affect and bring about changes in aggregate demand. In the long-run, benefits of gender-

equal opportunities in labor, education, and health are more efficient than the pervasive gender

inequality seeing today (Booth and Bennett, 2002). Thus, conversion of gender equality creates

opportunities for equal outcomes.

Therefore, the question that arises is whether differences in wages and income affect economic growth

or not? The following research will, therefore, endeavor to determine whether gender inequality has an

economic impact. Thus, this provides a guide for the researcher to determine if indeed there is a

relationship between gender gap and the GDP.

b. Dataset 1 description

Dataset 1 is a dataset specifically assigned to the undersigned researcher. The dataset entails an

individual sample file from 2013 to 2014 that was obtained from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

Thus, the dataset can be described as secondary in nature.

The dataset entails four variables; gender, occ_code, Sw_amt, and Gift_amt. The characteristics of the

variables are as shown in the table below:

Table 1: Variable description

Variable Description Values Type

Gender Gender (sex) Female or Male Dichotomous

Occ_code Salary/wage occupation 0 = Occupation not listed/Occupation not Dichotomous

Section 1: Introduction

a. Introduction

The gender gap is the difference between the salary of men and that of women (Bekhouche ey al.,

2013). The gender gap is attributed to not only discrimination in hiring but also the different industries

which women and men work among others. Gender equality has been a major case of discussion by

many people across different fields globally (Grown et al., 2005). According to Schwab (2017), the

gender biases been experienced across the different field in the economy are keeping the mass from

closing the gender gap thereby causing an overwhelming of the economy.

The following research aims at finding the relationship between the gender gap and the GDP. Thus the

arising research question:

What is the a relationship between gender gap and the GDP

The research is necessitated by the fact that closing the gender gap is vital for policymaking and

development (World Bank, 2012). According to Revenga and Shetty (2012), gender equality is vital for

enhancing economic productivity, improving the outcomes of development for future generations, and

making institutional and policies more representative. Momsen (2009), states that progress is a course

which expands freedom similarly for all the people both female and male. Thus, closing gender equality

improves economic productivity and improves other outcomes of development (Hausmann, 2009).

The net impact of gender inequality on growth is quite ambiguous. In some way, gender inequality is

attributed to hindering growth or support growth circumstantially (Galor and Moav, 2004). Income and

wages rapidly affect and bring about changes in aggregate demand. In the long-run, benefits of gender-

equal opportunities in labor, education, and health are more efficient than the pervasive gender

inequality seeing today (Booth and Bennett, 2002). Thus, conversion of gender equality creates

opportunities for equal outcomes.

Therefore, the question that arises is whether differences in wages and income affect economic growth

or not? The following research will, therefore, endeavor to determine whether gender inequality has an

economic impact. Thus, this provides a guide for the researcher to determine if indeed there is a

relationship between gender gap and the GDP.

b. Dataset 1 description

Dataset 1 is a dataset specifically assigned to the undersigned researcher. The dataset entails an

individual sample file from 2013 to 2014 that was obtained from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

Thus, the dataset can be described as secondary in nature.

The dataset entails four variables; gender, occ_code, Sw_amt, and Gift_amt. The characteristics of the

variables are as shown in the table below:

Table 1: Variable description

Variable Description Values Type

Gender Gender (sex) Female or Male Dichotomous

Occ_code Salary/wage occupation 0 = Occupation not listed/Occupation not Dichotomous

Gender equality in Australia 3

code specified

1 = Managers

2 = Professionals

3 = Technicians and Trades Workers

4 = Community and Personal Service

Workers

5 = Clerical and Administrative Workers

6 = Sales worker

7 = Machinery operators and drivers

8 = Laborers

9 = Consultants, apprentices and type not

specified or not listed

Sw_amt Salary/wage amount All numeric Continuous

Gift_amt Gifts or donation

deductions

All numeric Continuous

The first 5 cases of dataset 1 are as shown below:

Table 2: first 5 cases of dataset 1

Gender

Occ_cod

e

Sw_am

t

Gift_am

t

Male 0 17360 0

Male 3 2861 120

Male 0 0 0

Female 9 6661 0

Female 5 29881 25

c. Dataset 2 description

Dataset 2 was collected from online sources, which is the Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD). The sample collected cannot be termed as biased since it was obtained from a

verified source (Boakes et al., 2010). However, the use of online data source meant that the data being

searched had various disadvantages (Louise Hunter, 2012). For instance, the data collected had limited

time frame as it only captured data from 1975 till 2016. Moreover, there was missing data as there was

no recorded wage gap index for 1996. Collection of the data from the OECD implies that the data is

secondary in nature.

The variables used in dataset 2 are wage gap and GDP. The two variables are all numerical, thus they are

continuous in nature.

Section 2: Descriptive Statistics

code specified

1 = Managers

2 = Professionals

3 = Technicians and Trades Workers

4 = Community and Personal Service

Workers

5 = Clerical and Administrative Workers

6 = Sales worker

7 = Machinery operators and drivers

8 = Laborers

9 = Consultants, apprentices and type not

specified or not listed

Sw_amt Salary/wage amount All numeric Continuous

Gift_amt Gifts or donation

deductions

All numeric Continuous

The first 5 cases of dataset 1 are as shown below:

Table 2: first 5 cases of dataset 1

Gender

Occ_cod

e

Sw_am

t

Gift_am

t

Male 0 17360 0

Male 3 2861 120

Male 0 0 0

Female 9 6661 0

Female 5 29881 25

c. Dataset 2 description

Dataset 2 was collected from online sources, which is the Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD). The sample collected cannot be termed as biased since it was obtained from a

verified source (Boakes et al., 2010). However, the use of online data source meant that the data being

searched had various disadvantages (Louise Hunter, 2012). For instance, the data collected had limited

time frame as it only captured data from 1975 till 2016. Moreover, there was missing data as there was

no recorded wage gap index for 1996. Collection of the data from the OECD implies that the data is

secondary in nature.

The variables used in dataset 2 are wage gap and GDP. The two variables are all numerical, thus they are

continuous in nature.

Section 2: Descriptive Statistics

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Gender equality in Australia 4

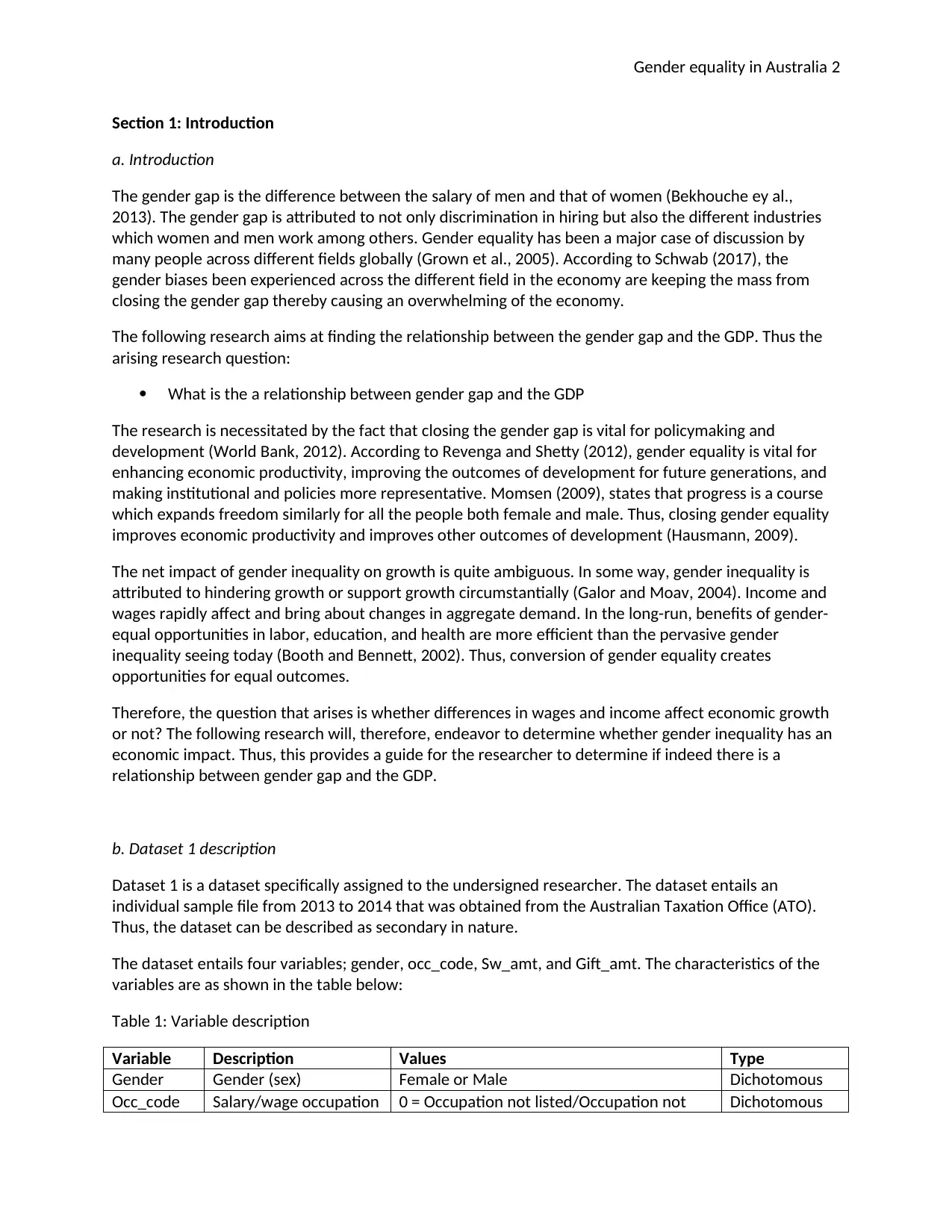

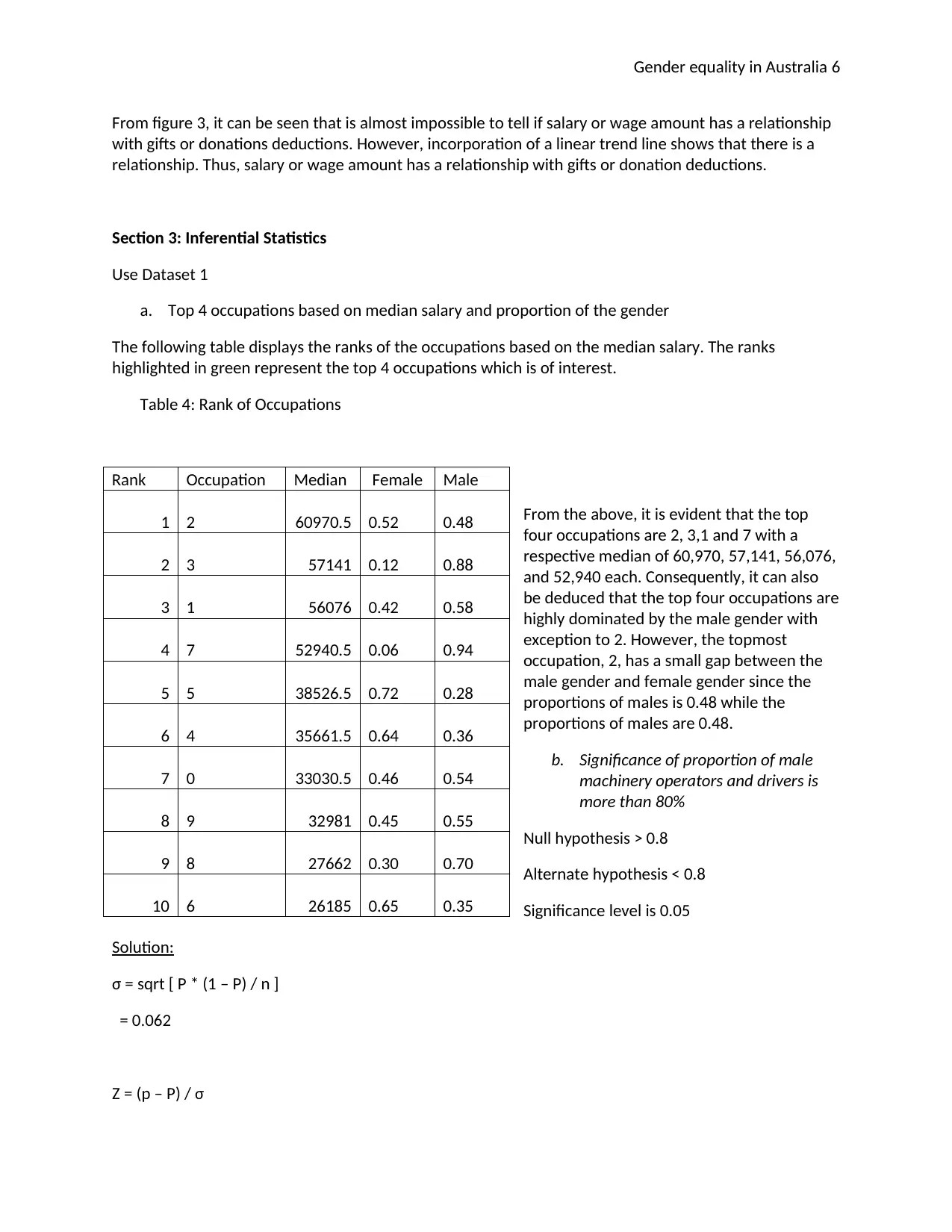

a. The relationship between the Gender variable and Occupation

The relationship between the gender variable and occupation can is as seen in the figure below:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

46% 42%

52%

12%

64% 72% 65%

6%

30%

45%

54% 58%

48%

88%

36% 28% 35%

94%

70%

55%

Gender Distribution against Occupation

Female(%) Male(%)

Figure 1: Gender distribution against the occupation

Figure 1 shows that most of the occupations including the ones not listed were highly dominated by the

male gender. However, occupation 4, 5, and 6 were dominated by the female gender with a

representation of 64%, 72% and 65% each. It can be noted that the male gender main domination is in

occupation 7 where they have a representation of 94% compared to the female gender who have a

representation of 6%. The female gender has mainly dominated occupation 5 where they are

represented by 72% while the male gender gets a meager representation of 28%.

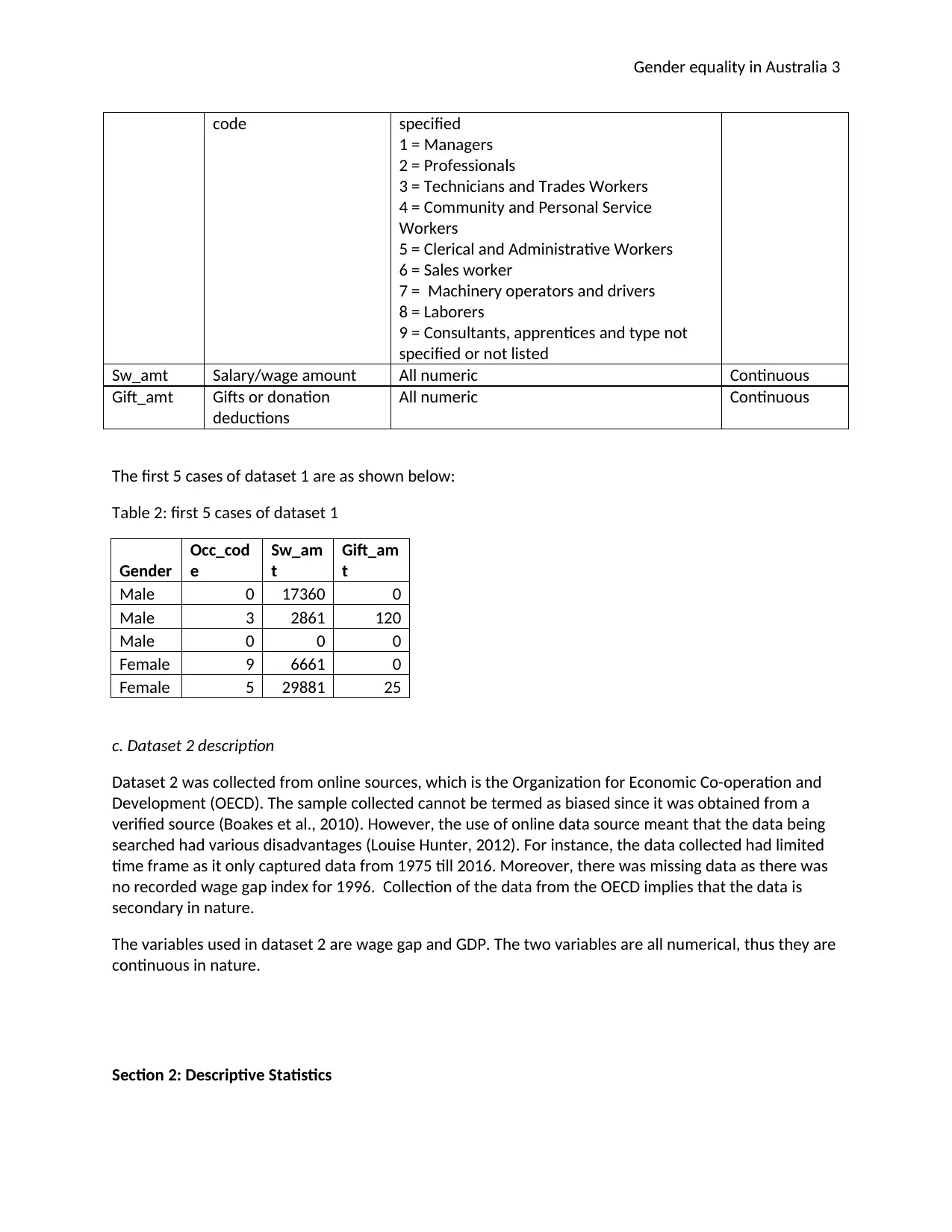

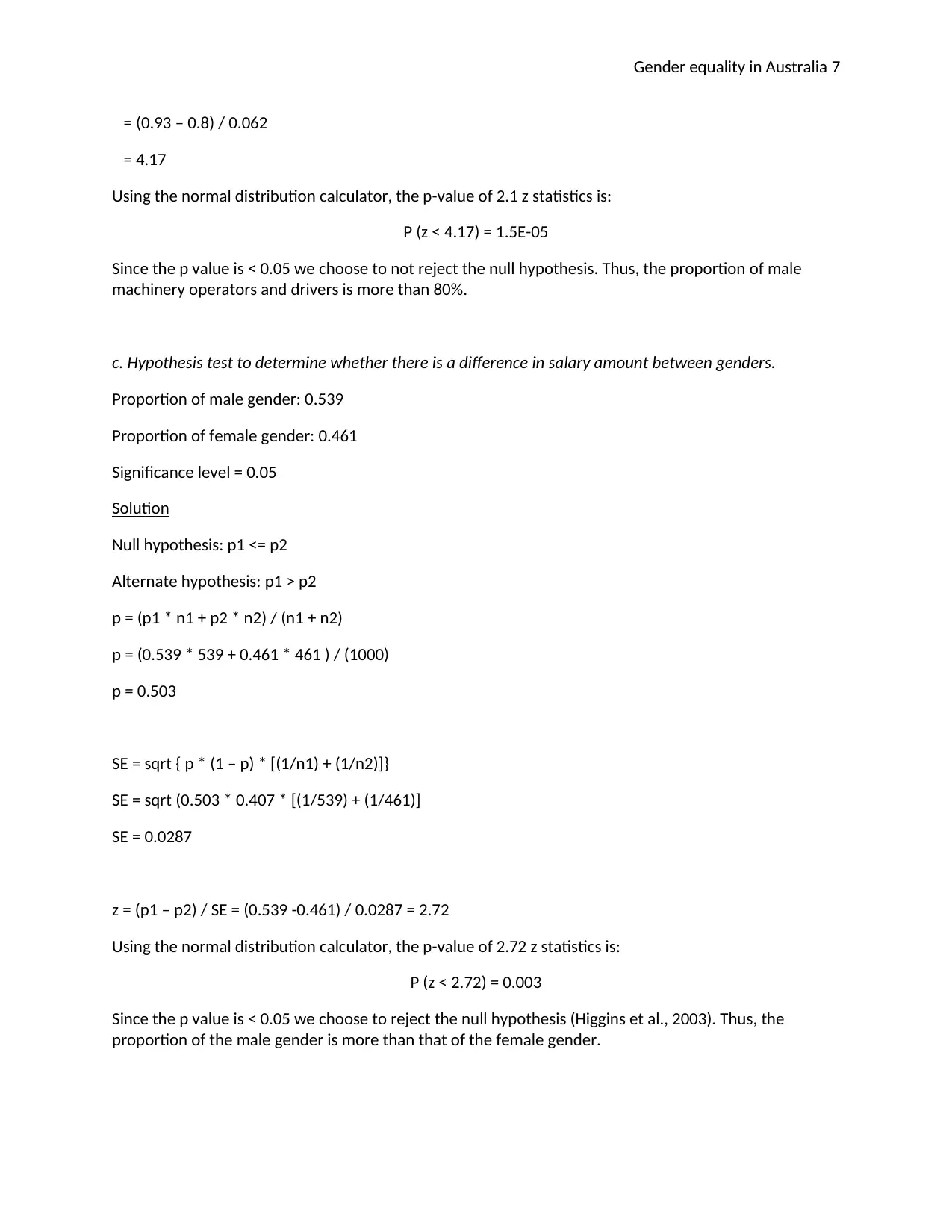

b. The relationship between the Gender Variable and Salary or wage amount

The following dot plot was constructed with the aim of coming up with a graphical presentation to show

the relationship between the gender variable and the salary or wage amount.

Figure 2: Salary/wage amount against

gender

Figure 2 shows that most of the female

genders earn less than $200,000 except for

one incidence (outlier) who earns more

than $200,000. On the other hand, the

more of the male gender earn more than

$200,000 when compared to the female

gender. Additionally, the incidence (outliers)

of those who earn a great amount of salary

a. The relationship between the Gender variable and Occupation

The relationship between the gender variable and occupation can is as seen in the figure below:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

46% 42%

52%

12%

64% 72% 65%

6%

30%

45%

54% 58%

48%

88%

36% 28% 35%

94%

70%

55%

Gender Distribution against Occupation

Female(%) Male(%)

Figure 1: Gender distribution against the occupation

Figure 1 shows that most of the occupations including the ones not listed were highly dominated by the

male gender. However, occupation 4, 5, and 6 were dominated by the female gender with a

representation of 64%, 72% and 65% each. It can be noted that the male gender main domination is in

occupation 7 where they have a representation of 94% compared to the female gender who have a

representation of 6%. The female gender has mainly dominated occupation 5 where they are

represented by 72% while the male gender gets a meager representation of 28%.

b. The relationship between the Gender Variable and Salary or wage amount

The following dot plot was constructed with the aim of coming up with a graphical presentation to show

the relationship between the gender variable and the salary or wage amount.

Figure 2: Salary/wage amount against

gender

Figure 2 shows that most of the female

genders earn less than $200,000 except for

one incidence (outlier) who earns more

than $200,000. On the other hand, the

more of the male gender earn more than

$200,000 when compared to the female

gender. Additionally, the incidence (outliers)

of those who earn a great amount of salary

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Gender equality in Australia 5

or wages in the male gender is two with one matching the maximum of the female gender while the

other earning more than $800,000.

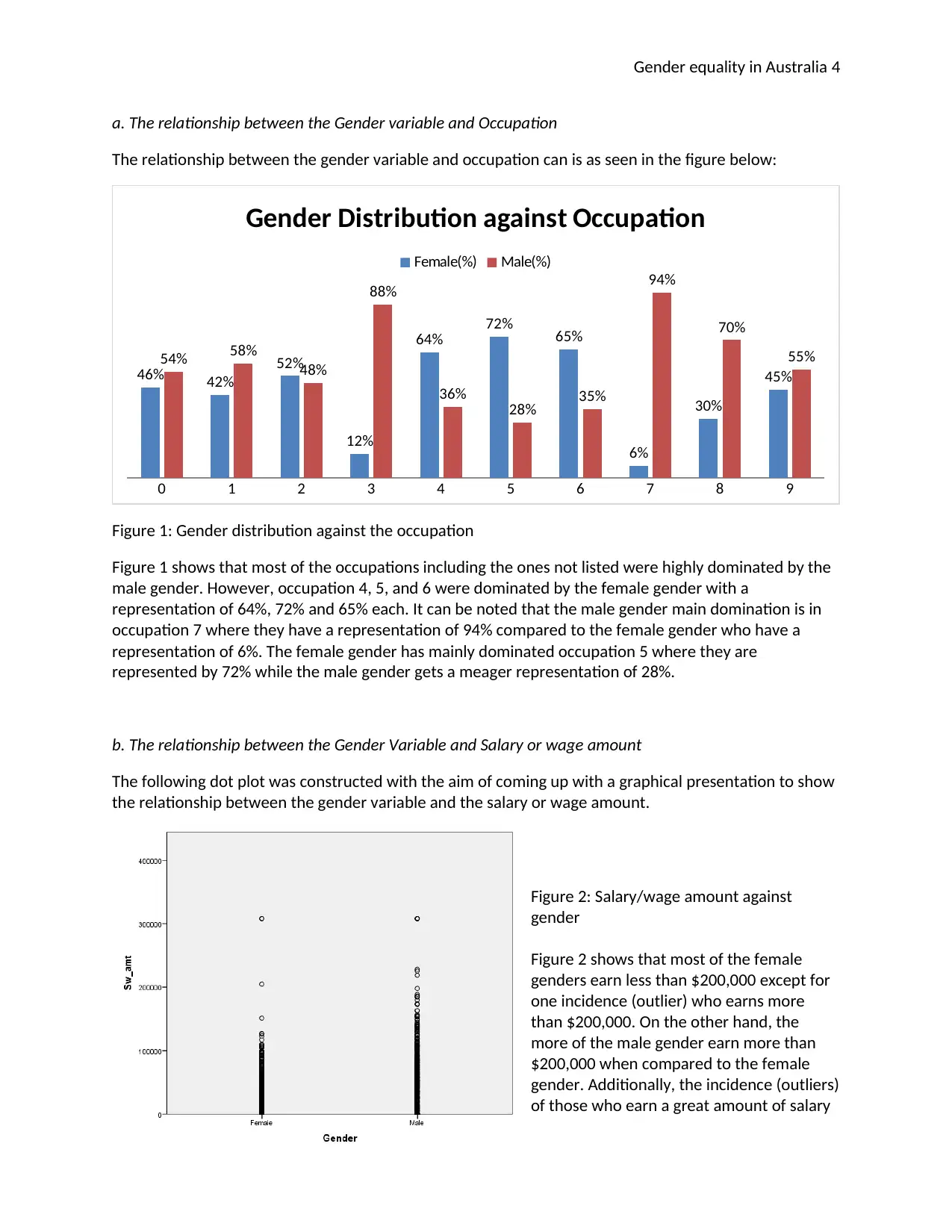

c. The relationship between the variables Gender and Salary or wage amount (numerical summary)

The table below shows the numerical statistics which shows the relationship between gender and salary

or wage amount.

Table 3: Gender vs. salary or wage amount

Row Labels

Average of

Sw_amt

StdDev of

Sw_amt

Min of

Sw_amt

Max of

Sw_amt

Count of

Sw_amt

Female 35,462 40,189 0 308,183 461

Male 55,680 68,244 0 839,840 539

Grand Total 46,359 57,910 0 839,840 1,000

The mean of female gender with regards to salary or wage amount is $35462 with a standard deviation

of $40,189. On the other hand, the male gender had a salary or wage amount that averaged $55,680

with a standard deviation of $68,244. From this, it is evident that the male gender earned a high salary

or wage amount compared with the female gender. Conversely, the male gender had a high variation

($68,244 standard deviation) compared to the female gender ($40,189 standard deviation).

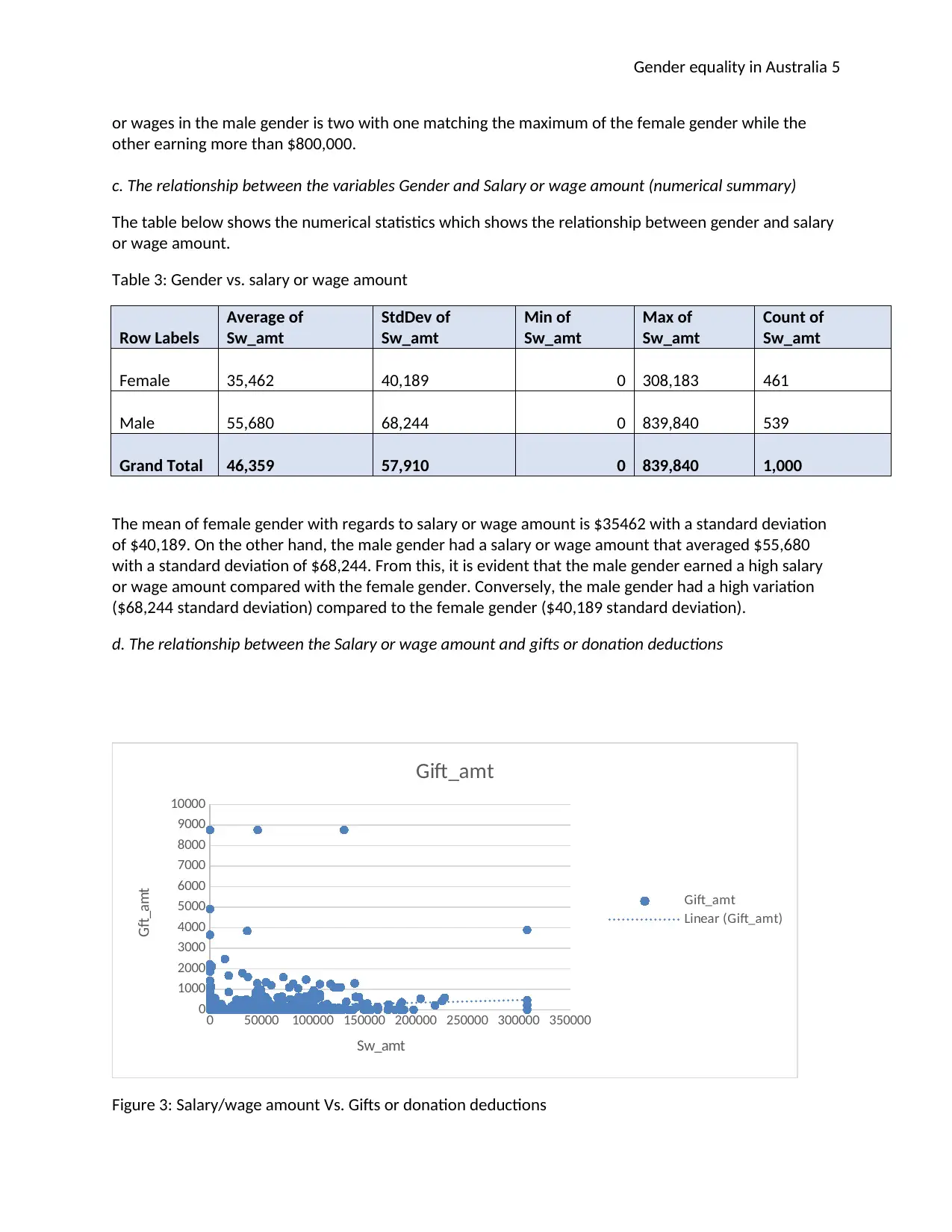

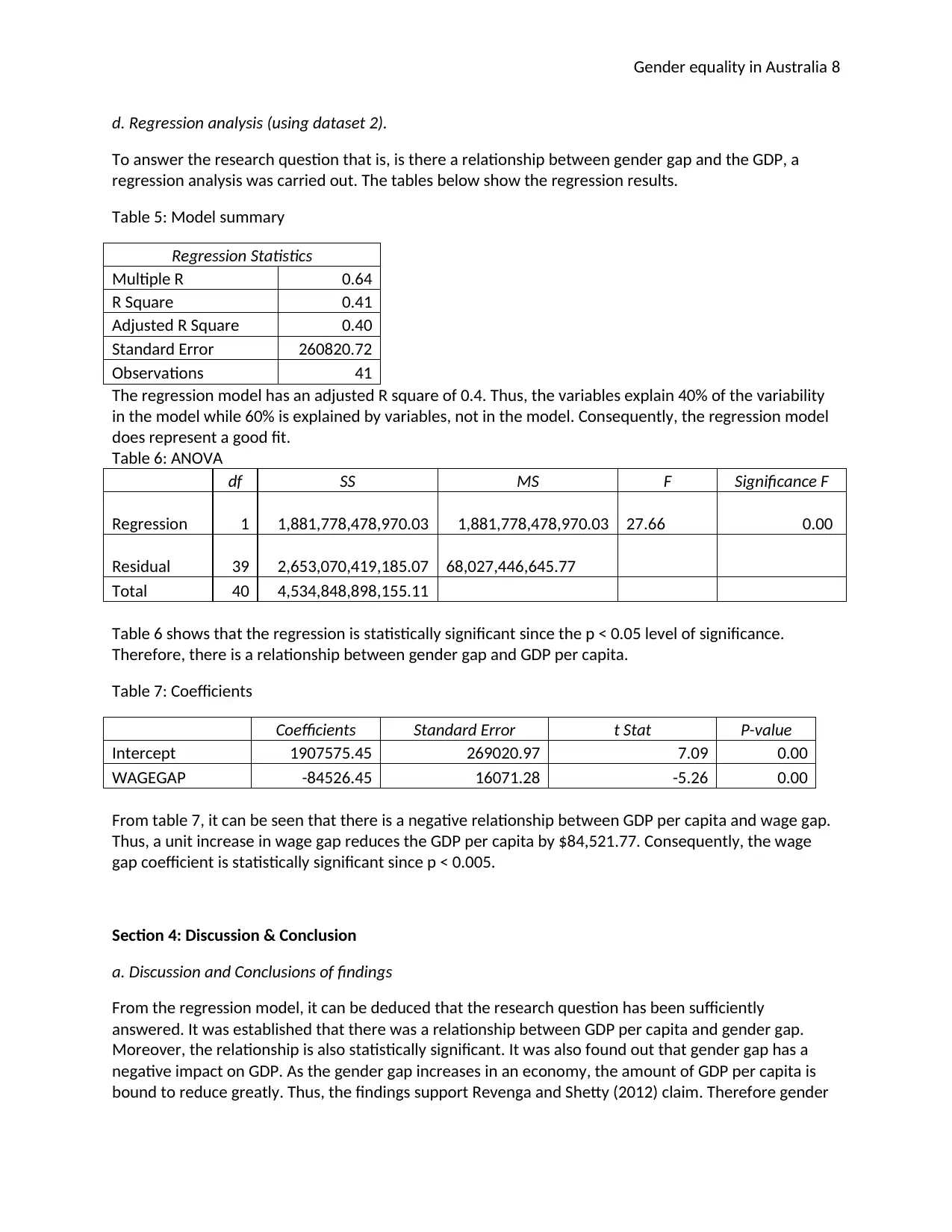

d. The relationship between the Salary or wage amount and gifts or donation deductions

0 50000 100000 150000 200000 250000 300000 350000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Gift_amt

Gift_amt

Linear (Gift_amt)

Sw_amt

Gft_amt

Figure 3: Salary/wage amount Vs. Gifts or donation deductions

or wages in the male gender is two with one matching the maximum of the female gender while the

other earning more than $800,000.

c. The relationship between the variables Gender and Salary or wage amount (numerical summary)

The table below shows the numerical statistics which shows the relationship between gender and salary

or wage amount.

Table 3: Gender vs. salary or wage amount

Row Labels

Average of

Sw_amt

StdDev of

Sw_amt

Min of

Sw_amt

Max of

Sw_amt

Count of

Sw_amt

Female 35,462 40,189 0 308,183 461

Male 55,680 68,244 0 839,840 539

Grand Total 46,359 57,910 0 839,840 1,000

The mean of female gender with regards to salary or wage amount is $35462 with a standard deviation

of $40,189. On the other hand, the male gender had a salary or wage amount that averaged $55,680

with a standard deviation of $68,244. From this, it is evident that the male gender earned a high salary

or wage amount compared with the female gender. Conversely, the male gender had a high variation

($68,244 standard deviation) compared to the female gender ($40,189 standard deviation).

d. The relationship between the Salary or wage amount and gifts or donation deductions

0 50000 100000 150000 200000 250000 300000 350000

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Gift_amt

Gift_amt

Linear (Gift_amt)

Sw_amt

Gft_amt

Figure 3: Salary/wage amount Vs. Gifts or donation deductions

Gender equality in Australia 6

From figure 3, it can be seen that is almost impossible to tell if salary or wage amount has a relationship

with gifts or donations deductions. However, incorporation of a linear trend line shows that there is a

relationship. Thus, salary or wage amount has a relationship with gifts or donation deductions.

Section 3: Inferential Statistics

Use Dataset 1

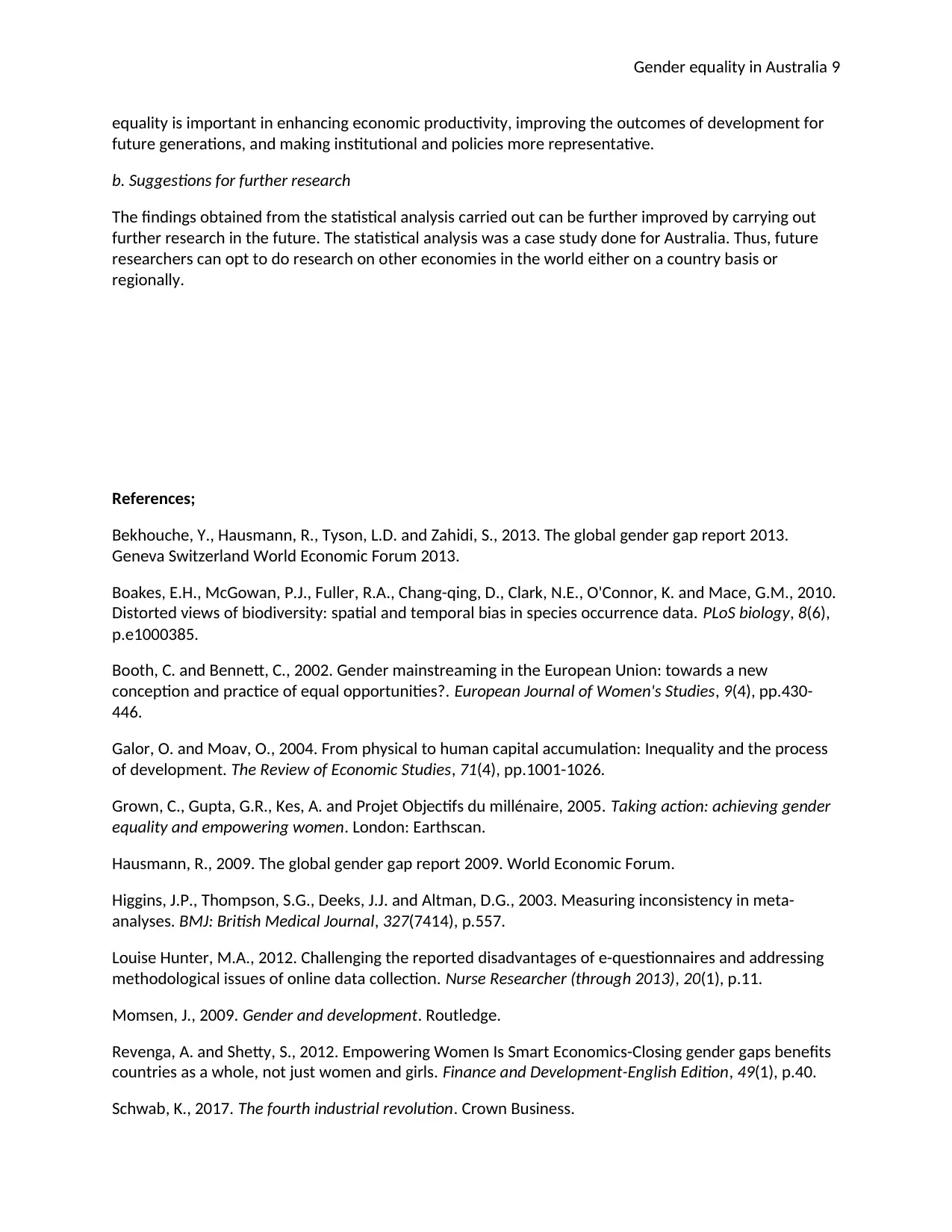

a. Top 4 occupations based on median salary and proportion of the gender

The following table displays the ranks of the occupations based on the median salary. The ranks

highlighted in green represent the top 4 occupations which is of interest.

Table 4: Rank of Occupations

From the above, it is evident that the top

four occupations are 2, 3,1 and 7 with a

respective median of 60,970, 57,141, 56,076,

and 52,940 each. Consequently, it can also

be deduced that the top four occupations are

highly dominated by the male gender with

exception to 2. However, the topmost

occupation, 2, has a small gap between the

male gender and female gender since the

proportions of males is 0.48 while the

proportions of males are 0.48.

b. Significance of proportion of male

machinery operators and drivers is

more than 80%

Null hypothesis > 0.8

Alternate hypothesis < 0.8

Significance level is 0.05

Solution:

σ = sqrt [ P * (1 – P) / n ]

= 0.062

Z = (p – P) / σ

Rank Occupation Median Female Male

1 2 60970.5 0.52 0.48

2 3 57141 0.12 0.88

3 1 56076 0.42 0.58

4 7 52940.5 0.06 0.94

5 5 38526.5 0.72 0.28

6 4 35661.5 0.64 0.36

7 0 33030.5 0.46 0.54

8 9 32981 0.45 0.55

9 8 27662 0.30 0.70

10 6 26185 0.65 0.35

From figure 3, it can be seen that is almost impossible to tell if salary or wage amount has a relationship

with gifts or donations deductions. However, incorporation of a linear trend line shows that there is a

relationship. Thus, salary or wage amount has a relationship with gifts or donation deductions.

Section 3: Inferential Statistics

Use Dataset 1

a. Top 4 occupations based on median salary and proportion of the gender

The following table displays the ranks of the occupations based on the median salary. The ranks

highlighted in green represent the top 4 occupations which is of interest.

Table 4: Rank of Occupations

From the above, it is evident that the top

four occupations are 2, 3,1 and 7 with a

respective median of 60,970, 57,141, 56,076,

and 52,940 each. Consequently, it can also

be deduced that the top four occupations are

highly dominated by the male gender with

exception to 2. However, the topmost

occupation, 2, has a small gap between the

male gender and female gender since the

proportions of males is 0.48 while the

proportions of males are 0.48.

b. Significance of proportion of male

machinery operators and drivers is

more than 80%

Null hypothesis > 0.8

Alternate hypothesis < 0.8

Significance level is 0.05

Solution:

σ = sqrt [ P * (1 – P) / n ]

= 0.062

Z = (p – P) / σ

Rank Occupation Median Female Male

1 2 60970.5 0.52 0.48

2 3 57141 0.12 0.88

3 1 56076 0.42 0.58

4 7 52940.5 0.06 0.94

5 5 38526.5 0.72 0.28

6 4 35661.5 0.64 0.36

7 0 33030.5 0.46 0.54

8 9 32981 0.45 0.55

9 8 27662 0.30 0.70

10 6 26185 0.65 0.35

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Gender equality in Australia 7

= (0.93 – 0.8) / 0.062

= 4.17

Using the normal distribution calculator, the p-value of 2.1 z statistics is:

P (z < 4.17) = 1.5E-05

Since the p value is < 0.05 we choose to not reject the null hypothesis. Thus, the proportion of male

machinery operators and drivers is more than 80%.

c. Hypothesis test to determine whether there is a difference in salary amount between genders.

Proportion of male gender: 0.539

Proportion of female gender: 0.461

Significance level = 0.05

Solution

Null hypothesis: p1 <= p2

Alternate hypothesis: p1 > p2

p = (p1 * n1 + p2 * n2) / (n1 + n2)

p = (0.539 * 539 + 0.461 * 461 ) / (1000)

p = 0.503

SE = sqrt { p * (1 – p) * [(1/n1) + (1/n2)]}

SE = sqrt (0.503 * 0.407 * [(1/539) + (1/461)]

SE = 0.0287

z = (p1 – p2) / SE = (0.539 -0.461) / 0.0287 = 2.72

Using the normal distribution calculator, the p-value of 2.72 z statistics is:

P (z < 2.72) = 0.003

Since the p value is < 0.05 we choose to reject the null hypothesis (Higgins et al., 2003). Thus, the

proportion of the male gender is more than that of the female gender.

= (0.93 – 0.8) / 0.062

= 4.17

Using the normal distribution calculator, the p-value of 2.1 z statistics is:

P (z < 4.17) = 1.5E-05

Since the p value is < 0.05 we choose to not reject the null hypothesis. Thus, the proportion of male

machinery operators and drivers is more than 80%.

c. Hypothesis test to determine whether there is a difference in salary amount between genders.

Proportion of male gender: 0.539

Proportion of female gender: 0.461

Significance level = 0.05

Solution

Null hypothesis: p1 <= p2

Alternate hypothesis: p1 > p2

p = (p1 * n1 + p2 * n2) / (n1 + n2)

p = (0.539 * 539 + 0.461 * 461 ) / (1000)

p = 0.503

SE = sqrt { p * (1 – p) * [(1/n1) + (1/n2)]}

SE = sqrt (0.503 * 0.407 * [(1/539) + (1/461)]

SE = 0.0287

z = (p1 – p2) / SE = (0.539 -0.461) / 0.0287 = 2.72

Using the normal distribution calculator, the p-value of 2.72 z statistics is:

P (z < 2.72) = 0.003

Since the p value is < 0.05 we choose to reject the null hypothesis (Higgins et al., 2003). Thus, the

proportion of the male gender is more than that of the female gender.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Gender equality in Australia 8

d. Regression analysis (using dataset 2).

To answer the research question that is, is there a relationship between gender gap and the GDP, a

regression analysis was carried out. The tables below show the regression results.

Table 5: Model summary

Regression Statistics

Multiple R 0.64

R Square 0.41

Adjusted R Square 0.40

Standard Error 260820.72

Observations 41

The regression model has an adjusted R square of 0.4. Thus, the variables explain 40% of the variability

in the model while 60% is explained by variables, not in the model. Consequently, the regression model

does represent a good fit.

Table 6: ANOVA

df SS MS F Significance F

Regression 1 1,881,778,478,970.03 1,881,778,478,970.03 27.66 0.00

Residual 39 2,653,070,419,185.07 68,027,446,645.77

Total 40 4,534,848,898,155.11

Table 6 shows that the regression is statistically significant since the p < 0.05 level of significance.

Therefore, there is a relationship between gender gap and GDP per capita.

Table 7: Coefficients

Coefficients Standard Error t Stat P-value

Intercept 1907575.45 269020.97 7.09 0.00

WAGEGAP -84526.45 16071.28 -5.26 0.00

From table 7, it can be seen that there is a negative relationship between GDP per capita and wage gap.

Thus, a unit increase in wage gap reduces the GDP per capita by $84,521.77. Consequently, the wage

gap coefficient is statistically significant since p < 0.005.

Section 4: Discussion & Conclusion

a. Discussion and Conclusions of findings

From the regression model, it can be deduced that the research question has been sufficiently

answered. It was established that there was a relationship between GDP per capita and gender gap.

Moreover, the relationship is also statistically significant. It was also found out that gender gap has a

negative impact on GDP. As the gender gap increases in an economy, the amount of GDP per capita is

bound to reduce greatly. Thus, the findings support Revenga and Shetty (2012) claim. Therefore gender

d. Regression analysis (using dataset 2).

To answer the research question that is, is there a relationship between gender gap and the GDP, a

regression analysis was carried out. The tables below show the regression results.

Table 5: Model summary

Regression Statistics

Multiple R 0.64

R Square 0.41

Adjusted R Square 0.40

Standard Error 260820.72

Observations 41

The regression model has an adjusted R square of 0.4. Thus, the variables explain 40% of the variability

in the model while 60% is explained by variables, not in the model. Consequently, the regression model

does represent a good fit.

Table 6: ANOVA

df SS MS F Significance F

Regression 1 1,881,778,478,970.03 1,881,778,478,970.03 27.66 0.00

Residual 39 2,653,070,419,185.07 68,027,446,645.77

Total 40 4,534,848,898,155.11

Table 6 shows that the regression is statistically significant since the p < 0.05 level of significance.

Therefore, there is a relationship between gender gap and GDP per capita.

Table 7: Coefficients

Coefficients Standard Error t Stat P-value

Intercept 1907575.45 269020.97 7.09 0.00

WAGEGAP -84526.45 16071.28 -5.26 0.00

From table 7, it can be seen that there is a negative relationship between GDP per capita and wage gap.

Thus, a unit increase in wage gap reduces the GDP per capita by $84,521.77. Consequently, the wage

gap coefficient is statistically significant since p < 0.005.

Section 4: Discussion & Conclusion

a. Discussion and Conclusions of findings

From the regression model, it can be deduced that the research question has been sufficiently

answered. It was established that there was a relationship between GDP per capita and gender gap.

Moreover, the relationship is also statistically significant. It was also found out that gender gap has a

negative impact on GDP. As the gender gap increases in an economy, the amount of GDP per capita is

bound to reduce greatly. Thus, the findings support Revenga and Shetty (2012) claim. Therefore gender

Gender equality in Australia 9

equality is important in enhancing economic productivity, improving the outcomes of development for

future generations, and making institutional and policies more representative.

b. Suggestions for further research

The findings obtained from the statistical analysis carried out can be further improved by carrying out

further research in the future. The statistical analysis was a case study done for Australia. Thus, future

researchers can opt to do research on other economies in the world either on a country basis or

regionally.

References;

Bekhouche, Y., Hausmann, R., Tyson, L.D. and Zahidi, S., 2013. The global gender gap report 2013.

Geneva Switzerland World Economic Forum 2013.

Boakes, E.H., McGowan, P.J., Fuller, R.A., Chang-qing, D., Clark, N.E., O'Connor, K. and Mace, G.M., 2010.

Distorted views of biodiversity: spatial and temporal bias in species occurrence data. PLoS biology, 8(6),

p.e1000385.

Booth, C. and Bennett, C., 2002. Gender mainstreaming in the European Union: towards a new

conception and practice of equal opportunities?. European Journal of Women's Studies, 9(4), pp.430-

446.

Galor, O. and Moav, O., 2004. From physical to human capital accumulation: Inequality and the process

of development. The Review of Economic Studies, 71(4), pp.1001-1026.

Grown, C., Gupta, G.R., Kes, A. and Projet Objectifs du millénaire, 2005. Taking action: achieving gender

equality and empowering women. London: Earthscan.

Hausmann, R., 2009. The global gender gap report 2009. World Economic Forum.

Higgins, J.P., Thompson, S.G., Deeks, J.J. and Altman, D.G., 2003. Measuring inconsistency in meta-

analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 327(7414), p.557.

Louise Hunter, M.A., 2012. Challenging the reported disadvantages of e-questionnaires and addressing

methodological issues of online data collection. Nurse Researcher (through 2013), 20(1), p.11.

Momsen, J., 2009. Gender and development. Routledge.

Revenga, A. and Shetty, S., 2012. Empowering Women Is Smart Economics-Closing gender gaps benefits

countries as a whole, not just women and girls. Finance and Development-English Edition, 49(1), p.40.

Schwab, K., 2017. The fourth industrial revolution. Crown Business.

equality is important in enhancing economic productivity, improving the outcomes of development for

future generations, and making institutional and policies more representative.

b. Suggestions for further research

The findings obtained from the statistical analysis carried out can be further improved by carrying out

further research in the future. The statistical analysis was a case study done for Australia. Thus, future

researchers can opt to do research on other economies in the world either on a country basis or

regionally.

References;

Bekhouche, Y., Hausmann, R., Tyson, L.D. and Zahidi, S., 2013. The global gender gap report 2013.

Geneva Switzerland World Economic Forum 2013.

Boakes, E.H., McGowan, P.J., Fuller, R.A., Chang-qing, D., Clark, N.E., O'Connor, K. and Mace, G.M., 2010.

Distorted views of biodiversity: spatial and temporal bias in species occurrence data. PLoS biology, 8(6),

p.e1000385.

Booth, C. and Bennett, C., 2002. Gender mainstreaming in the European Union: towards a new

conception and practice of equal opportunities?. European Journal of Women's Studies, 9(4), pp.430-

446.

Galor, O. and Moav, O., 2004. From physical to human capital accumulation: Inequality and the process

of development. The Review of Economic Studies, 71(4), pp.1001-1026.

Grown, C., Gupta, G.R., Kes, A. and Projet Objectifs du millénaire, 2005. Taking action: achieving gender

equality and empowering women. London: Earthscan.

Hausmann, R., 2009. The global gender gap report 2009. World Economic Forum.

Higgins, J.P., Thompson, S.G., Deeks, J.J. and Altman, D.G., 2003. Measuring inconsistency in meta-

analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 327(7414), p.557.

Louise Hunter, M.A., 2012. Challenging the reported disadvantages of e-questionnaires and addressing

methodological issues of online data collection. Nurse Researcher (through 2013), 20(1), p.11.

Momsen, J., 2009. Gender and development. Routledge.

Revenga, A. and Shetty, S., 2012. Empowering Women Is Smart Economics-Closing gender gaps benefits

countries as a whole, not just women and girls. Finance and Development-English Edition, 49(1), p.40.

Schwab, K., 2017. The fourth industrial revolution. Crown Business.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Gender equality in Australia 10

World Bank’s 2012 World Development Report: Gender Equality and Development.

World Bank’s 2012 World Development Report: Gender Equality and Development.

1 out of 10

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.