Identifiable Dimensions to Effective Global Supply Chains: Culture

VerifiedAdded on 2020/12/07

|27

|9613

|74

Report

AI Summary

This report, prepared for the 28th International Congress of Psychology (ICP2004), investigates the critical role of culture in shaping the effectiveness of global supply chains, particularly within the context of the food industry. The research, by Susan A. Hornibrook and Pamela M. Yeow, examines how cultural differences influence perceptions of risk and impact relationships between firms in geographically and culturally diverse supply chains. The study builds upon previous work that views vertically coordinated supply chains as strategic responses to perceived risk, incorporating perspectives from various academic disciplines, including economics, management, and psychology. The authors develop a framework to analyze cross-cultural supply chain relationships, using Tesco's expansion into China as a case study. The report addresses the globalization of the food industry, supply chain management, and the application of Perceived Risk Theory, while also introducing alternative theoretical perspectives that account for cultural differences. The paper identifies areas suitable for further research regarding the consequences of culture and perceived risk on global supply chains, contributing to the supply chain literature by adopting an interdisciplinary approach and presenting a theoretical framework for the examination of the role of culture on effective supply chain management.

IDENTIFIABLE DIMENSIONS TO EFFECTIVE GLOBAL SUPPLY

CHAINS: THE ROLE OF CULTURE

SUSAN A HORNIBROOK & PAMELA M YEOW

Kent Business School

University of Kent

Parkwood Road

Canterbury, Kent CT2 7PE

United Kingdom

Telephone: (44) (0)1227 827731, (44) (0)1227 823991

Fax: (44) (0)1227 761187

Email: s.a.hornibrook@kent.ac.uk

p.m.yeow@kent.ac.uk

WORK IN PROGRESS (3)

Paper prepared for the 28th International Congress of Psychology (ICP2004) in

Beijing, China, 8-13 August 2004.

1

CHAINS: THE ROLE OF CULTURE

SUSAN A HORNIBROOK & PAMELA M YEOW

Kent Business School

University of Kent

Parkwood Road

Canterbury, Kent CT2 7PE

United Kingdom

Telephone: (44) (0)1227 827731, (44) (0)1227 823991

Fax: (44) (0)1227 761187

Email: s.a.hornibrook@kent.ac.uk

p.m.yeow@kent.ac.uk

WORK IN PROGRESS (3)

Paper prepared for the 28th International Congress of Psychology (ICP2004) in

Beijing, China, 8-13 August 2004.

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ABSTRACT

2

2

1. Introduction

The continuing globalisation of food manufacturing, together with the more recent

moves towards internationalisation of major food retailers such as Tesco, Metro,

Carrefour and Wal-Mart, poses a number of significant challenges to all firms along

the supply chain.

In Europe, and particularly the UK, own brand products are a key component of

competitive strategy, and in order to guarantee food quality and safety, retailer-led

domestic vertically co-ordinated supply chains have emerged (Hornibrook and Fearne

2001). As European retailers seek growth through international expansion in order to

combat market saturation and low growth in domestic markets, the strategic

importance of own brand products and economies of scale associated with global

sourcing will become increasingly significant. In addition to food quality and safety,

a number of other critical supply chain issues including ethical and environmental

concerns are also driving closer relationships between food retailers and their first and

second tier suppliers. Given the increasing globalisation of both trade and markets for

food, and the need for closer relationships and management of the supply chain, the

impact of culture on relationships between firms in geographically and culturally

diverse supply chains becomes particularly significant.

Researchers from various academic disciplines have adopted a number of different

economic and management theoretical perspectives in order to examine supply chain

management, in particular transaction cost economics, systems theory, game theory

and channel management. This paper seeks to build on previous work that considers

vertically co-ordinated supply chains as strategic responses to perceived risk

(Hornibrook and Fearne, 2001, 2003) by examining the role of culture (Hofstede,

1980, 1994; Schein, 1985, 1990; Trompennars., 1993; Yeow, 2000, 2002; Erez and

Gati, 2004). By adopting a cross-disciplinary behavioural perspective and including a

psychological dimension, the authors seek to add to the supply chain management and

organisational behaviour literature by developing a framework for the examination of

cross cultural supply chain relationships. Given the emerging significance of China

as a potential market and source of supply for western food firms, and the different

perspectives on personal and business relationships between Asia and the West (Liu

and Wang, 1999), the paper develops a number of propositions within the framework

3

The continuing globalisation of food manufacturing, together with the more recent

moves towards internationalisation of major food retailers such as Tesco, Metro,

Carrefour and Wal-Mart, poses a number of significant challenges to all firms along

the supply chain.

In Europe, and particularly the UK, own brand products are a key component of

competitive strategy, and in order to guarantee food quality and safety, retailer-led

domestic vertically co-ordinated supply chains have emerged (Hornibrook and Fearne

2001). As European retailers seek growth through international expansion in order to

combat market saturation and low growth in domestic markets, the strategic

importance of own brand products and economies of scale associated with global

sourcing will become increasingly significant. In addition to food quality and safety,

a number of other critical supply chain issues including ethical and environmental

concerns are also driving closer relationships between food retailers and their first and

second tier suppliers. Given the increasing globalisation of both trade and markets for

food, and the need for closer relationships and management of the supply chain, the

impact of culture on relationships between firms in geographically and culturally

diverse supply chains becomes particularly significant.

Researchers from various academic disciplines have adopted a number of different

economic and management theoretical perspectives in order to examine supply chain

management, in particular transaction cost economics, systems theory, game theory

and channel management. This paper seeks to build on previous work that considers

vertically co-ordinated supply chains as strategic responses to perceived risk

(Hornibrook and Fearne, 2001, 2003) by examining the role of culture (Hofstede,

1980, 1994; Schein, 1985, 1990; Trompennars., 1993; Yeow, 2000, 2002; Erez and

Gati, 2004). By adopting a cross-disciplinary behavioural perspective and including a

psychological dimension, the authors seek to add to the supply chain management and

organisational behaviour literature by developing a framework for the examination of

cross cultural supply chain relationships. Given the emerging significance of China

as a potential market and source of supply for western food firms, and the different

perspectives on personal and business relationships between Asia and the West (Liu

and Wang, 1999), the paper develops a number of propositions within the framework

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

to identify and discuss the impact of culture on perceptions of risk, using the example

of Tesco’s recent expansion into China as a case study. Additionally, the paper will

identify areas suitable for further research regarding the consequences of culture and

perceived risk on global supply chains.

This paper contributes to the supply chain literature in two ways. It adopts an

interdisciplinary approach to supply chain management and presents a theoretical

framework for the examination of the role of culture on effective supply chain

management. The paper is presented in four parts. The first section sets the scene by

discussing the globalisation of the food industry, supply chain management and

implications for firms. The second section critically discusses the application of

Perceived Risk Theory to supply chains, in particular the failure of the framework to

account for the effect of culture on behaviour. Other theoretical perspectives that do

take account of cultural differences are introduced in the third section, and the

proposed theoretical framework is introduced in the fourth section. Next, the

framework is tested using the example of the UK food retailer, Tesco, and their recent

expansion into China. The final part draws some conclusions and presents

recommendations for further research.

2. Supply Chain Management

2.1 Globalisation and the Food Industry

Paton and McCalman (2000:7-8) identified a number of major external changes that

all organisations are currently addressing or will have to come to terms with in the 21st

Century. These include the development of enhanced technologies and increased

competition due to world-wide historical, political and economic changes; worldwide

recognition of the increasing importance of finite resources and the environment as an

influential variable; health consciousness as a permanent trend across all age groups

and a growing awareness and concern associated with food production and

consumption throughout the developed world; changes in lifestyle trends affecting the

way people view work, purchases, leisure time and society; changes in the workplace

creating a need for non-traditional employees; and the crucial role of knowledge and

people to the competitive well being of organisations.

4

of Tesco’s recent expansion into China as a case study. Additionally, the paper will

identify areas suitable for further research regarding the consequences of culture and

perceived risk on global supply chains.

This paper contributes to the supply chain literature in two ways. It adopts an

interdisciplinary approach to supply chain management and presents a theoretical

framework for the examination of the role of culture on effective supply chain

management. The paper is presented in four parts. The first section sets the scene by

discussing the globalisation of the food industry, supply chain management and

implications for firms. The second section critically discusses the application of

Perceived Risk Theory to supply chains, in particular the failure of the framework to

account for the effect of culture on behaviour. Other theoretical perspectives that do

take account of cultural differences are introduced in the third section, and the

proposed theoretical framework is introduced in the fourth section. Next, the

framework is tested using the example of the UK food retailer, Tesco, and their recent

expansion into China. The final part draws some conclusions and presents

recommendations for further research.

2. Supply Chain Management

2.1 Globalisation and the Food Industry

Paton and McCalman (2000:7-8) identified a number of major external changes that

all organisations are currently addressing or will have to come to terms with in the 21st

Century. These include the development of enhanced technologies and increased

competition due to world-wide historical, political and economic changes; worldwide

recognition of the increasing importance of finite resources and the environment as an

influential variable; health consciousness as a permanent trend across all age groups

and a growing awareness and concern associated with food production and

consumption throughout the developed world; changes in lifestyle trends affecting the

way people view work, purchases, leisure time and society; changes in the workplace

creating a need for non-traditional employees; and the crucial role of knowledge and

people to the competitive well being of organisations.

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

In addition to the above general changes, the food industry has been subject to a

number of specific environmental changes that have affected and driven international

and global activity. Drivers of the increase of cross border trade in agricultural and

food products include the reduction of national tariffs and non-tariff barriers (WTO,

2003), standardisation of food safety and quality standards (WHO, 2003), consumer

demand, and firm strategic behaviour (Fearne et al, 2001). As a result, the food

industry has become interdependent and global, instead of simply international

(Varzakas and Jukes, 1997). Globalisation is not just limited to the range of a firm’s

activities across geographical markets, but also the extent of contractual co-operation

with other firms (Mattsson, 2003). As a consequence, actions, events and decisions

taken in one part of the world will have a significant impact on individuals and

communities in other, more distant, parts of the earth (McGrew, 1992). Globalisation

therefore, has implications for those firms such as multinational food manufacturers

and more recently European retailers, whose commercial reputation and success

depends upon branded products sourced and produced by suppliers who may operate

under different environmental conditions.

The drive for more consistent eating quality has become a competitive strategy

amongst UK food retailers to gain market share through improved margins and

customer loyalty (IGD 2003), and has led to various attempts at marketing

differentiated retail branded products sourced through retailer-led co-ordinated supply

chains. Own brands, as defined by Davis (1992) are positioned as niche, high quality

products sold at a premium price, supported by strong technical and quality control

involvement from the retailer. UK retailers do not produce own brand products but

delegate the task of production to a small number of large suppliers, with whom they

develop close relationships. Such businesses that participate in co-ordinated

relationships remain distinct in the legal sense, but in other respects, extend their

influence beyond their organisational boundaries. The structure of the UK retailing

sector is such that market power is a feature, with multiple retailers able to impose

their requirements very effectively on the supply chain (Northern, 2000). However,

the economic benefits resulting from the success of own brands are offset by an

increase in the level of risk for those retailers who invest in own brand products. The

more detailed their requirements and instructions to their upstream suppliers, the more

5

number of specific environmental changes that have affected and driven international

and global activity. Drivers of the increase of cross border trade in agricultural and

food products include the reduction of national tariffs and non-tariff barriers (WTO,

2003), standardisation of food safety and quality standards (WHO, 2003), consumer

demand, and firm strategic behaviour (Fearne et al, 2001). As a result, the food

industry has become interdependent and global, instead of simply international

(Varzakas and Jukes, 1997). Globalisation is not just limited to the range of a firm’s

activities across geographical markets, but also the extent of contractual co-operation

with other firms (Mattsson, 2003). As a consequence, actions, events and decisions

taken in one part of the world will have a significant impact on individuals and

communities in other, more distant, parts of the earth (McGrew, 1992). Globalisation

therefore, has implications for those firms such as multinational food manufacturers

and more recently European retailers, whose commercial reputation and success

depends upon branded products sourced and produced by suppliers who may operate

under different environmental conditions.

The drive for more consistent eating quality has become a competitive strategy

amongst UK food retailers to gain market share through improved margins and

customer loyalty (IGD 2003), and has led to various attempts at marketing

differentiated retail branded products sourced through retailer-led co-ordinated supply

chains. Own brands, as defined by Davis (1992) are positioned as niche, high quality

products sold at a premium price, supported by strong technical and quality control

involvement from the retailer. UK retailers do not produce own brand products but

delegate the task of production to a small number of large suppliers, with whom they

develop close relationships. Such businesses that participate in co-ordinated

relationships remain distinct in the legal sense, but in other respects, extend their

influence beyond their organisational boundaries. The structure of the UK retailing

sector is such that market power is a feature, with multiple retailers able to impose

their requirements very effectively on the supply chain (Northern, 2000). However,

the economic benefits resulting from the success of own brands are offset by an

increase in the level of risk for those retailers who invest in own brand products. The

more detailed their requirements and instructions to their upstream suppliers, the more

5

they are held responsible for the safety and quality of the end product by both

regulators and consumers. By delegating the task to upstream suppliers, the need for

control, communication and information is paramount in order to protect the retailers’

reputation and market share.

Supply chain management is therefore seen as crucial by UK retailers, particularly in

relation to maintaining food quality and safety. In the UK, consumers have become

increasingly concerned about food safety and quality issues, particularly those risks

that have potentially severe consequences, and are little understood, such as nvCJD.

However, other emerging and high profile issues that may impact upon brand image

and reputation are beginning to attract interest by supply chain researchers and

practitioners. These areas include environmental issues such as pollution, resource

depletion and waste management, as well as ethical issues (New, 2004b) relating to

labour and human rights, employment practices, bribery and corruption, and corporate

governance. In today’s challenging global markets, the management of relationships

are viewed as a key element of successful supply chains (Christopher, 2004).

2.2 Theoretical Roots and Approaches

The concept of Supply Chain Management (SCM) has developed over time from

having an intra-organisational focus on logistics to becoming focused on wider inter-

organisational issues. Although practitioners and academics use the term widely, there

is no universally agreed definition (Dubois et al, 2004). The main tensions arise

between those who adopt a functional perspective and view SCM as an overall term

for logistics - managing the flow of materials and products from source to user - with

the focus on operational issues. Others view SCM as a management philosophy

concerned with the management of supply and demand across traditional boundaries –

functional, organisational and relational – and recognises that by doing so,

organisations will gain commercial benefits (New, 1996). This research recognises the

latter approach, in which the scope of SCM is defined as wider than that of logistics,

is driven by the need to develop competitive advantage for all firms in the supply

chain, and involves collaboration across functional, organisational and individual

boundaries. The emphasis is on key supply chain-wide business processes across the

whole supply chain, including customers and consumers (customer relationship

management, demand management, order fulfilment, manufacturing flow

6

regulators and consumers. By delegating the task to upstream suppliers, the need for

control, communication and information is paramount in order to protect the retailers’

reputation and market share.

Supply chain management is therefore seen as crucial by UK retailers, particularly in

relation to maintaining food quality and safety. In the UK, consumers have become

increasingly concerned about food safety and quality issues, particularly those risks

that have potentially severe consequences, and are little understood, such as nvCJD.

However, other emerging and high profile issues that may impact upon brand image

and reputation are beginning to attract interest by supply chain researchers and

practitioners. These areas include environmental issues such as pollution, resource

depletion and waste management, as well as ethical issues (New, 2004b) relating to

labour and human rights, employment practices, bribery and corruption, and corporate

governance. In today’s challenging global markets, the management of relationships

are viewed as a key element of successful supply chains (Christopher, 2004).

2.2 Theoretical Roots and Approaches

The concept of Supply Chain Management (SCM) has developed over time from

having an intra-organisational focus on logistics to becoming focused on wider inter-

organisational issues. Although practitioners and academics use the term widely, there

is no universally agreed definition (Dubois et al, 2004). The main tensions arise

between those who adopt a functional perspective and view SCM as an overall term

for logistics - managing the flow of materials and products from source to user - with

the focus on operational issues. Others view SCM as a management philosophy

concerned with the management of supply and demand across traditional boundaries –

functional, organisational and relational – and recognises that by doing so,

organisations will gain commercial benefits (New, 1996). This research recognises the

latter approach, in which the scope of SCM is defined as wider than that of logistics,

is driven by the need to develop competitive advantage for all firms in the supply

chain, and involves collaboration across functional, organisational and individual

boundaries. The emphasis is on key supply chain-wide business processes across the

whole supply chain, including customers and consumers (customer relationship

management, demand management, order fulfilment, manufacturing flow

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

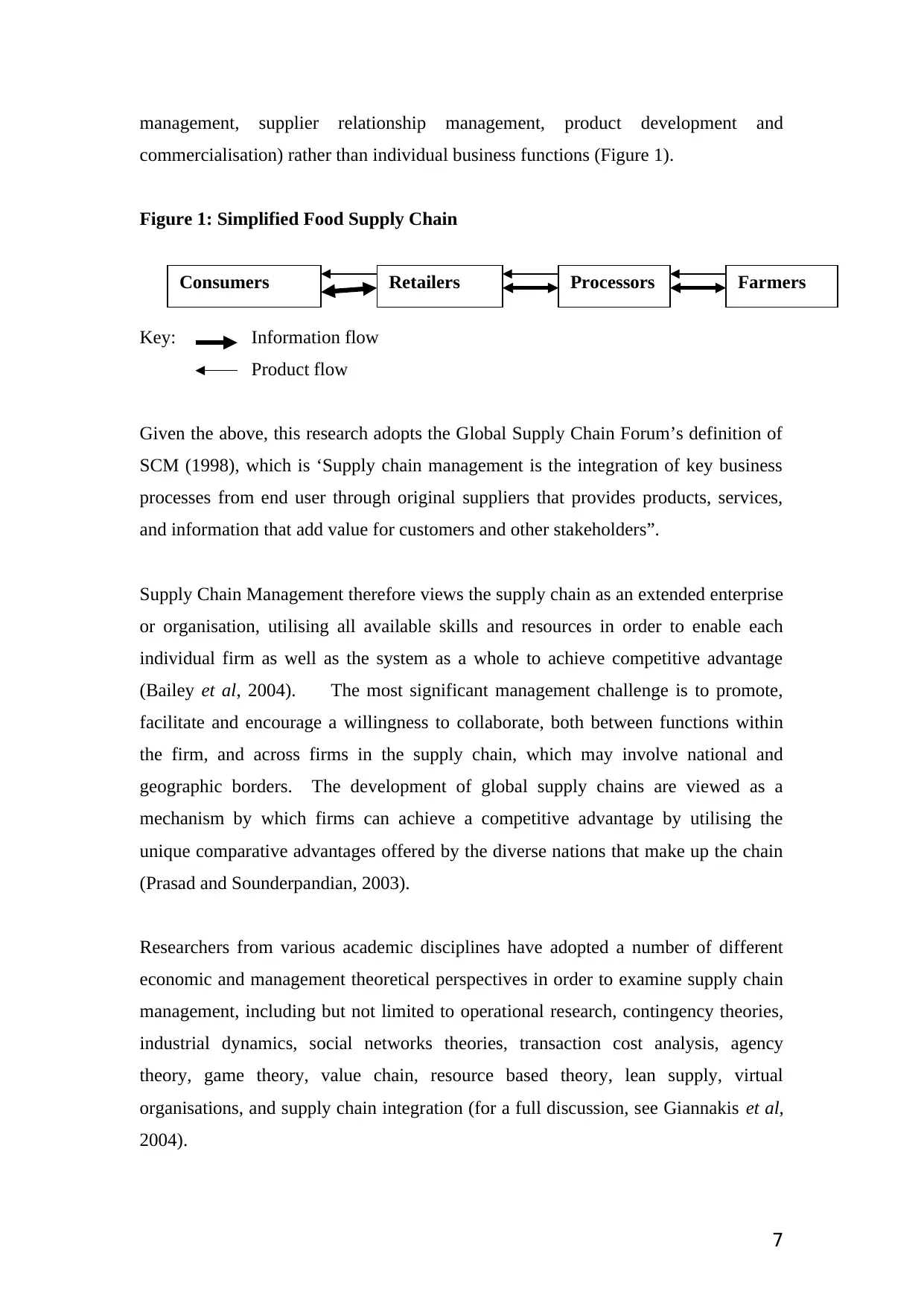

management, supplier relationship management, product development and

commercialisation) rather than individual business functions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Simplified Food Supply Chain

Key: Information flow

Product flow

Given the above, this research adopts the Global Supply Chain Forum’s definition of

SCM (1998), which is ‘Supply chain management is the integration of key business

processes from end user through original suppliers that provides products, services,

and information that add value for customers and other stakeholders”.

Supply Chain Management therefore views the supply chain as an extended enterprise

or organisation, utilising all available skills and resources in order to enable each

individual firm as well as the system as a whole to achieve competitive advantage

(Bailey et al, 2004). The most significant management challenge is to promote,

facilitate and encourage a willingness to collaborate, both between functions within

the firm, and across firms in the supply chain, which may involve national and

geographic borders. The development of global supply chains are viewed as a

mechanism by which firms can achieve a competitive advantage by utilising the

unique comparative advantages offered by the diverse nations that make up the chain

(Prasad and Sounderpandian, 2003).

Researchers from various academic disciplines have adopted a number of different

economic and management theoretical perspectives in order to examine supply chain

management, including but not limited to operational research, contingency theories,

industrial dynamics, social networks theories, transaction cost analysis, agency

theory, game theory, value chain, resource based theory, lean supply, virtual

organisations, and supply chain integration (for a full discussion, see Giannakis et al,

2004).

7

Consumers Retailers Processors Farmers

commercialisation) rather than individual business functions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Simplified Food Supply Chain

Key: Information flow

Product flow

Given the above, this research adopts the Global Supply Chain Forum’s definition of

SCM (1998), which is ‘Supply chain management is the integration of key business

processes from end user through original suppliers that provides products, services,

and information that add value for customers and other stakeholders”.

Supply Chain Management therefore views the supply chain as an extended enterprise

or organisation, utilising all available skills and resources in order to enable each

individual firm as well as the system as a whole to achieve competitive advantage

(Bailey et al, 2004). The most significant management challenge is to promote,

facilitate and encourage a willingness to collaborate, both between functions within

the firm, and across firms in the supply chain, which may involve national and

geographic borders. The development of global supply chains are viewed as a

mechanism by which firms can achieve a competitive advantage by utilising the

unique comparative advantages offered by the diverse nations that make up the chain

(Prasad and Sounderpandian, 2003).

Researchers from various academic disciplines have adopted a number of different

economic and management theoretical perspectives in order to examine supply chain

management, including but not limited to operational research, contingency theories,

industrial dynamics, social networks theories, transaction cost analysis, agency

theory, game theory, value chain, resource based theory, lean supply, virtual

organisations, and supply chain integration (for a full discussion, see Giannakis et al,

2004).

7

Consumers Retailers Processors Farmers

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Critics of the operational perspective adopted by economists, sociologists and

organisational theorists have noted the need to adopt a multidisciplinary approach

(Nassimbeni, 2004; Harland et al, 2004) and have called for different ways to

conceptualise the problems faced by manufacturers, retailers and distributors (New,

2004). In the UK, a series of high profile food safety and quality incidents, changes

in both public and private regulation of the market, and the greater exposure to the

risks of product failure for retail brands have increased risk for all stakeholders.

Supply chains operating across geographic and national borders will encounter

increased cultural and ethnic diversity in comparison to domestically based supply

chains, which in turn will affect the risks associated with food safety and quality, and

consequent consumer and organisational behaviour. From a theoretical perspective,

the risk perceptions of both consumers and organisations (Zwart and Mollenkopf,

2000, Yeung and Morris 2001) and the impact of culture on such perceptions cannot

be ignored when examining global supply chain behaviour.

3. Perceived Risk Theory

Different interpretations and approaches to risk can be identified in the literature.

Scientists and policy makers in western societies view risk objectively, assuming that

the probabilities and consequences of adverse events can be identified and quantified.

This notion is rejected by many social scientists, who argue instead that such a view is

incomplete at best and misleading at worst, and that risk “does not exist “out there”,

independent of our minds and cultures, waiting to be measured” (Slovic, 2002:4).

The focus of the approach in the sociology and psychology literature is therefore on

the effects of perceptions of risk on individual behaviour.

Initial research into consumer behaviour began in the 1960’s, informed by theory

borrowed from social and clinical psychology, anthropology and sociology (Cox,

1967). Perceived Risk Theory (Cox, 1967; Bauer, 1967; Dowling and Staelin, 1994)

asserts that consumers perceive risk in a buying situation because the resultant

consequences cannot be known in advance, and that some such consequences are

likely to be unpleasant. Researchers note that risk perception is shaped more by the

severity of the consequences than the probability of occurrence (Slovic, Fischoff,

Lichenstein, 1980; Diamond, 1988; Mitchell, 1998). The theory also notes that the

consequences from a purchase can be divided into various types of loss: performance,

8

organisational theorists have noted the need to adopt a multidisciplinary approach

(Nassimbeni, 2004; Harland et al, 2004) and have called for different ways to

conceptualise the problems faced by manufacturers, retailers and distributors (New,

2004). In the UK, a series of high profile food safety and quality incidents, changes

in both public and private regulation of the market, and the greater exposure to the

risks of product failure for retail brands have increased risk for all stakeholders.

Supply chains operating across geographic and national borders will encounter

increased cultural and ethnic diversity in comparison to domestically based supply

chains, which in turn will affect the risks associated with food safety and quality, and

consequent consumer and organisational behaviour. From a theoretical perspective,

the risk perceptions of both consumers and organisations (Zwart and Mollenkopf,

2000, Yeung and Morris 2001) and the impact of culture on such perceptions cannot

be ignored when examining global supply chain behaviour.

3. Perceived Risk Theory

Different interpretations and approaches to risk can be identified in the literature.

Scientists and policy makers in western societies view risk objectively, assuming that

the probabilities and consequences of adverse events can be identified and quantified.

This notion is rejected by many social scientists, who argue instead that such a view is

incomplete at best and misleading at worst, and that risk “does not exist “out there”,

independent of our minds and cultures, waiting to be measured” (Slovic, 2002:4).

The focus of the approach in the sociology and psychology literature is therefore on

the effects of perceptions of risk on individual behaviour.

Initial research into consumer behaviour began in the 1960’s, informed by theory

borrowed from social and clinical psychology, anthropology and sociology (Cox,

1967). Perceived Risk Theory (Cox, 1967; Bauer, 1967; Dowling and Staelin, 1994)

asserts that consumers perceive risk in a buying situation because the resultant

consequences cannot be known in advance, and that some such consequences are

likely to be unpleasant. Researchers note that risk perception is shaped more by the

severity of the consequences than the probability of occurrence (Slovic, Fischoff,

Lichenstein, 1980; Diamond, 1988; Mitchell, 1998). The theory also notes that the

consequences from a purchase can be divided into various types of loss: performance,

8

psychosocial, physical, financial and time (Mitchell, 1998). Performance risk can be

viewed in two ways: either as a surrogate measure for overall risk in that the product

results in a combination of other losses (Mitchell, 1998) or does not perform as

expected (Sweeney, Soutar, Johnson, 1999; Schiffman and Kanuk, 1994). Financial

risk is defined as a net financial loss, physical risk relates to the possible danger or

harm to the individual or to others, time risk is associated with the loss of time and

effort associated with achieving satisfaction with a purchase. Psychosocial risk

relates to possible loss of self-image or self-concept as a result of a purchase or use

(Murray and Schlacter, 1990) or social embarrassment (Schiffman and Kanuk, 1994).

The overall level of perceived risk is viewed as the sum of the attributes’ perceived

risk levels, with the degree of risk perceived varying by individual consumer,

depending on risk tolerance and wealth level, both of which impact upon the ability to

absorb a loss. If perceived risk exceeds the tolerable degree of the individual level,

then this triggers the motivation for risk-reducing behaviour. Such perceptions of risk

can be reduced through various risk reducing strategies, including increasing

information and reducing the consequences.

Theoretical debate on the possible impact of organisation’s perceptions of risk on

complete supply chains has only recently emerged (Christopher, 2004; New, 2004;

Lamming, Caldwell and Phillips, 2004, Hornibrook, 2002). In addition to consumers,

the impact of perceived risk on a purchase decision could also be extended to

business-to-business sourcing situations (Mitchell, 1998). Peters and Venkatesan

(1973) confirm that organisational buyers are affected by many of the same variables

that affect consumers, including perceived risk, an observation also supported by

March and Shapira (1987), Mitchell (1998) and Greatorex, Mitchell and Cunliffe

(1992). Generally, empirical research has focused on the perceived risk and risk

handling strategies of industrial buyers associated with choosing a supplier (Puto,

Patton and King, 1985; Hawes and Barnhouse, 1987; Greatorex, Mitchell and

Cunliffe, 1992). Most recently, Perceived Risk Theory has been utilised, using a

supply chain methodology, to examine vertically co-ordinated supply chains

comprising consumers, retailers, processors and farmers in the UK food industry.

Supply chain management is therefore viewed as a strategy to manage perceived risk,

for both consumers and organisations at different stages in the supply chain

(Hornibrook and Fearne, 2001, 2003).

9

viewed in two ways: either as a surrogate measure for overall risk in that the product

results in a combination of other losses (Mitchell, 1998) or does not perform as

expected (Sweeney, Soutar, Johnson, 1999; Schiffman and Kanuk, 1994). Financial

risk is defined as a net financial loss, physical risk relates to the possible danger or

harm to the individual or to others, time risk is associated with the loss of time and

effort associated with achieving satisfaction with a purchase. Psychosocial risk

relates to possible loss of self-image or self-concept as a result of a purchase or use

(Murray and Schlacter, 1990) or social embarrassment (Schiffman and Kanuk, 1994).

The overall level of perceived risk is viewed as the sum of the attributes’ perceived

risk levels, with the degree of risk perceived varying by individual consumer,

depending on risk tolerance and wealth level, both of which impact upon the ability to

absorb a loss. If perceived risk exceeds the tolerable degree of the individual level,

then this triggers the motivation for risk-reducing behaviour. Such perceptions of risk

can be reduced through various risk reducing strategies, including increasing

information and reducing the consequences.

Theoretical debate on the possible impact of organisation’s perceptions of risk on

complete supply chains has only recently emerged (Christopher, 2004; New, 2004;

Lamming, Caldwell and Phillips, 2004, Hornibrook, 2002). In addition to consumers,

the impact of perceived risk on a purchase decision could also be extended to

business-to-business sourcing situations (Mitchell, 1998). Peters and Venkatesan

(1973) confirm that organisational buyers are affected by many of the same variables

that affect consumers, including perceived risk, an observation also supported by

March and Shapira (1987), Mitchell (1998) and Greatorex, Mitchell and Cunliffe

(1992). Generally, empirical research has focused on the perceived risk and risk

handling strategies of industrial buyers associated with choosing a supplier (Puto,

Patton and King, 1985; Hawes and Barnhouse, 1987; Greatorex, Mitchell and

Cunliffe, 1992). Most recently, Perceived Risk Theory has been utilised, using a

supply chain methodology, to examine vertically co-ordinated supply chains

comprising consumers, retailers, processors and farmers in the UK food industry.

Supply chain management is therefore viewed as a strategy to manage perceived risk,

for both consumers and organisations at different stages in the supply chain

(Hornibrook and Fearne, 2001, 2003).

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The above describes a number of theoretical approaches, in particular Perceived Risk

Theory, to describe and explain supply chain behaviour. However, a number of

criticisms and limitations can be noted regarding current theory in general, and

Perceived Risk Theory in particular.

Perceived Risk theory makes some attempt to acknowledge the context and history of

actions and behaviour. However, although culture is identified as one determinant of

risk perception (Joffe, 2003, Slovic, 2002), the theory does not include the role of

culture in determining risk perception and the subsequent influence on risk reducing

behaviour. Additionally, the theory adopts individual dimensions of loss (physical,

time, financial, psychosocial, performance) that may only be appropriate in western

societies and may be limited in its scope for understanding global supply chains that

span different countries and cultures. Previous empirical research has been limited to

small, domestically orientated supply chains in the UK.

One of the main criticisms of both normative and descriptive research into supply

chains is that the prevailing SCM literature tends to use theoretical assumptions that

simplify the complex reality of interconnecting relationships between a host of

different actors (Dubois et al, 2004). Most research occurs at the dyad, limited

attempts have been made to examine relationships along product supply chains

(Hornibrook, 2002), and more recently, interest has extended to links among supply

chains (Dubois et al 2004). However, the dominant paradigm has been the

Newtonian style in which an idealised world is constructed in the form of an abstract

model, in order to approximate the behaviour of real objects (Tsoukas, 1998); to

examine and then to predict future behaviour without taking account of context and

history. The focus is on linear relationships, the organisation as a machine, agents as

objects, generalisability, observation, and universal laws.

Given that supply chains are extremely complex (Cox, 1999; Christopher, 2004;

Dubois et al, 2004), the use of oversimplified linear models and a Newtonian

perspective would seem to be inappropriate. Globalisation of firms and markets

involves reorganisation and confrontation between cultures, both at the organisational

and the national level (Mattsson, 2003). The need to understand the role of culture on

10

Theory, to describe and explain supply chain behaviour. However, a number of

criticisms and limitations can be noted regarding current theory in general, and

Perceived Risk Theory in particular.

Perceived Risk theory makes some attempt to acknowledge the context and history of

actions and behaviour. However, although culture is identified as one determinant of

risk perception (Joffe, 2003, Slovic, 2002), the theory does not include the role of

culture in determining risk perception and the subsequent influence on risk reducing

behaviour. Additionally, the theory adopts individual dimensions of loss (physical,

time, financial, psychosocial, performance) that may only be appropriate in western

societies and may be limited in its scope for understanding global supply chains that

span different countries and cultures. Previous empirical research has been limited to

small, domestically orientated supply chains in the UK.

One of the main criticisms of both normative and descriptive research into supply

chains is that the prevailing SCM literature tends to use theoretical assumptions that

simplify the complex reality of interconnecting relationships between a host of

different actors (Dubois et al, 2004). Most research occurs at the dyad, limited

attempts have been made to examine relationships along product supply chains

(Hornibrook, 2002), and more recently, interest has extended to links among supply

chains (Dubois et al 2004). However, the dominant paradigm has been the

Newtonian style in which an idealised world is constructed in the form of an abstract

model, in order to approximate the behaviour of real objects (Tsoukas, 1998); to

examine and then to predict future behaviour without taking account of context and

history. The focus is on linear relationships, the organisation as a machine, agents as

objects, generalisability, observation, and universal laws.

Given that supply chains are extremely complex (Cox, 1999; Christopher, 2004;

Dubois et al, 2004), the use of oversimplified linear models and a Newtonian

perspective would seem to be inappropriate. Globalisation of firms and markets

involves reorganisation and confrontation between cultures, both at the organisational

and the national level (Mattsson, 2003). The need to understand the role of culture on

10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

the effective management of different supply chain issues is highlighted by a number

of observers (Mattsson, 2003; Robertson and Crittenden, 2003; Prasad and

Sounderpandian, 2003; Weaver, 2001; Schneider & Barsoux, 2003).

4. Culture and Globalisation

Globalisation can be defined as the process by which cultures influence one another

and become more alike through trade, immigration and the exchange of information

and ideas. As such, the reach of globalisation extends to every part of the world, but

cultures differ greatly in how much they have been affected by it with considerable

variations within regions and within countries (Arnett, 2002). Culture comprises

divergent behaviours, norms and expectations and is fluid across space and time

(Ettlinger, 2003) and can be viewed as the patterns of cognitions and behaviour shared

by a group which evolve and becomes manifest in continuous processes of social

interaction. As beliefs and attitudes are important determinants of perceived risk,

interdisciplinary research is required to investigate the role of culture in determining

perceived risk, and the consequent influence of culture on organisational behaviour

and global supply chains.

Much work has been done in the importance in considering notions of culture in terms

of global organisations, virtual or otherwise (e.g. Schein, 1989, 1990; Hofstede, 1980,

1994; Hampden-Turner & Trompennars, 1993; Trompenaars, 1993), particularly

addressing the classification of cultural patterns. Alongside such work, a continuing

debate has been conducted regarding a) the appropriate level of analysis, as culture

level analysis reflects central tendencies for a country but does not predict individual

behaviour, and b) that differences in cultural patterns should be identified through

behaviour or values (Dahl, 2004).

Hofstede carried out large cross-cultural studies and identified five dimensions of

differences or traits between national cultures. These were labelled power-distance,

uncertainty avoidance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity and

long-term/short-term orientation. Power-distance indicates the extent to which a

society accepts that power is distributed unequally, with high power distance cultures

accepting inequality and respect for social status and class; low power distance

societies are more likely to value equality. Uncertainty avoidance indicates the extent

11

of observers (Mattsson, 2003; Robertson and Crittenden, 2003; Prasad and

Sounderpandian, 2003; Weaver, 2001; Schneider & Barsoux, 2003).

4. Culture and Globalisation

Globalisation can be defined as the process by which cultures influence one another

and become more alike through trade, immigration and the exchange of information

and ideas. As such, the reach of globalisation extends to every part of the world, but

cultures differ greatly in how much they have been affected by it with considerable

variations within regions and within countries (Arnett, 2002). Culture comprises

divergent behaviours, norms and expectations and is fluid across space and time

(Ettlinger, 2003) and can be viewed as the patterns of cognitions and behaviour shared

by a group which evolve and becomes manifest in continuous processes of social

interaction. As beliefs and attitudes are important determinants of perceived risk,

interdisciplinary research is required to investigate the role of culture in determining

perceived risk, and the consequent influence of culture on organisational behaviour

and global supply chains.

Much work has been done in the importance in considering notions of culture in terms

of global organisations, virtual or otherwise (e.g. Schein, 1989, 1990; Hofstede, 1980,

1994; Hampden-Turner & Trompennars, 1993; Trompenaars, 1993), particularly

addressing the classification of cultural patterns. Alongside such work, a continuing

debate has been conducted regarding a) the appropriate level of analysis, as culture

level analysis reflects central tendencies for a country but does not predict individual

behaviour, and b) that differences in cultural patterns should be identified through

behaviour or values (Dahl, 2004).

Hofstede carried out large cross-cultural studies and identified five dimensions of

differences or traits between national cultures. These were labelled power-distance,

uncertainty avoidance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity and

long-term/short-term orientation. Power-distance indicates the extent to which a

society accepts that power is distributed unequally, with high power distance cultures

accepting inequality and respect for social status and class; low power distance

societies are more likely to value equality. Uncertainty avoidance indicates the extent

11

to which people in a society feel threatened by ambiguous or unpredictable

circumstances. Individualism/collectivism represents the degree that cultures vary in

their emphasis on individualistic or collectivistic views of social life and personal

identity, and the degree to which they value group ties, which may be loose or strong.

Societies also range in characteristics that are associated with masculinity and

femininity, with members of masculine cultures viewing the world in terms of

winners and losers and feminine cultures discouraging the notion of competition. The

final dimension is the extent to which societies have different time horizons, either

long term or short term, and whether they value the past or are more future orientated.

Other researchers have added to these cultural dimensions (Kluckhohn and

Strodtbeck, 1961….etc)

Although there been accolades to his work, there have also been many criticisms. One

major problem with Hofstede’s approach is methodological. Cray and Mallory (1998)

write that the use of aggregated national data can be misleading when applying

societal characteristics to individual behaviour because there can be considerable

variance in the degree to which individuals adhere to any set of values. Others (cf.

Dorfman & Howell, 1988; Goodstein, 1981; Hunt, 1981; Robinson, 1983;

Sondergaard, 1994) have also criticised his scales in terms of their validity and

usefulness of their four dimensions at the individual level of analysis. It was argued

that it is not possible to discuss the impact of cultures on organisational structures if

all the data originates from the same study (Tayeb, 1988), with Hunt (1981:62)

questioning whether Hofstede was “studying the culture of the Japanese or the French

or the British or Malaysian executive or the culture of a multinational firm”. A

further criticism is that underlying values are derived from a measurement instrument

in which the focus is on the ultimate goal state, therefore the resultant underlying

values are frequently the result of very little data (Dahl, 2004).

A different approach in developing a framework in which to understand cultural

differences has been adopted by Schwartz (1992, 1994), who clearly distinguishes

between individual level analysis and culture level analysis in comparison to the work

of Hofstede and others (Dahl, 2004). This approach develops parallel sets of concepts

applicable to different levels of analysis, ie at the individual level and at the culture

level. Using data from more than 60,000 located in 63 countries, Schwartz derived

12

circumstances. Individualism/collectivism represents the degree that cultures vary in

their emphasis on individualistic or collectivistic views of social life and personal

identity, and the degree to which they value group ties, which may be loose or strong.

Societies also range in characteristics that are associated with masculinity and

femininity, with members of masculine cultures viewing the world in terms of

winners and losers and feminine cultures discouraging the notion of competition. The

final dimension is the extent to which societies have different time horizons, either

long term or short term, and whether they value the past or are more future orientated.

Other researchers have added to these cultural dimensions (Kluckhohn and

Strodtbeck, 1961….etc)

Although there been accolades to his work, there have also been many criticisms. One

major problem with Hofstede’s approach is methodological. Cray and Mallory (1998)

write that the use of aggregated national data can be misleading when applying

societal characteristics to individual behaviour because there can be considerable

variance in the degree to which individuals adhere to any set of values. Others (cf.

Dorfman & Howell, 1988; Goodstein, 1981; Hunt, 1981; Robinson, 1983;

Sondergaard, 1994) have also criticised his scales in terms of their validity and

usefulness of their four dimensions at the individual level of analysis. It was argued

that it is not possible to discuss the impact of cultures on organisational structures if

all the data originates from the same study (Tayeb, 1988), with Hunt (1981:62)

questioning whether Hofstede was “studying the culture of the Japanese or the French

or the British or Malaysian executive or the culture of a multinational firm”. A

further criticism is that underlying values are derived from a measurement instrument

in which the focus is on the ultimate goal state, therefore the resultant underlying

values are frequently the result of very little data (Dahl, 2004).

A different approach in developing a framework in which to understand cultural

differences has been adopted by Schwartz (1992, 1994), who clearly distinguishes

between individual level analysis and culture level analysis in comparison to the work

of Hofstede and others (Dahl, 2004). This approach develops parallel sets of concepts

applicable to different levels of analysis, ie at the individual level and at the culture

level. Using data from more than 60,000 located in 63 countries, Schwartz derived

12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 27

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.