ECON 3: Federal, State, and Local Government Budget Comparison Report

VerifiedAdded on 2020/02/18

|12

|1840

|53

Report

AI Summary

This report, prepared for an Economics 3 course, examines the budgetary differences between the federal, state, and local governments. It analyzes the allocation of funds, revenue sources (including taxes, levies, and licenses), and expenditure patterns of each level of government. The federal budget, primarily focused on defense and national programs, is contrasted with state budgets that emphasize social security, education, and health, and local government budgets which are focused on public transport and communication. The report highlights the varying proportions of allocations, revenue generation methods, and the implications of these differences. The analysis also includes a case study of two investment options, their pros and cons, and the decision-making process involved, considering factors like financial capacity and project feasibility. The report concludes by summarizing the key differences and providing references to support the analysis.

ECONOMICS 1

Course

Name

Institution Affiliation

Course

Name

Institution Affiliation

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECONOMICS 2

Federal Government Budget, State Government Budget and Local Government Budget

Differences

The federal budget in Sydney largely allocates funds for federal programs. These programs

include defense programs and at times it also includes funding for other programs which may be

operated at a state level such as public transport, hospitals and school education. It therefore has

more access to funding compared to the states. It is observable that the federal government

budget is higher than that of the state and local budget. Most of its allocations are to deal with

national defense facilities and other allocations to state agencies. Also, it may have a higher

allocation in order to deal with externa affairs as well as integration and pension (Wang, 2015).

Federal Government Budget, State Government Budget and Local Government Budget

Differences

The federal budget in Sydney largely allocates funds for federal programs. These programs

include defense programs and at times it also includes funding for other programs which may be

operated at a state level such as public transport, hospitals and school education. It therefore has

more access to funding compared to the states. It is observable that the federal government

budget is higher than that of the state and local budget. Most of its allocations are to deal with

national defense facilities and other allocations to state agencies. Also, it may have a higher

allocation in order to deal with externa affairs as well as integration and pension (Wang, 2015).

ECONOMICS 3

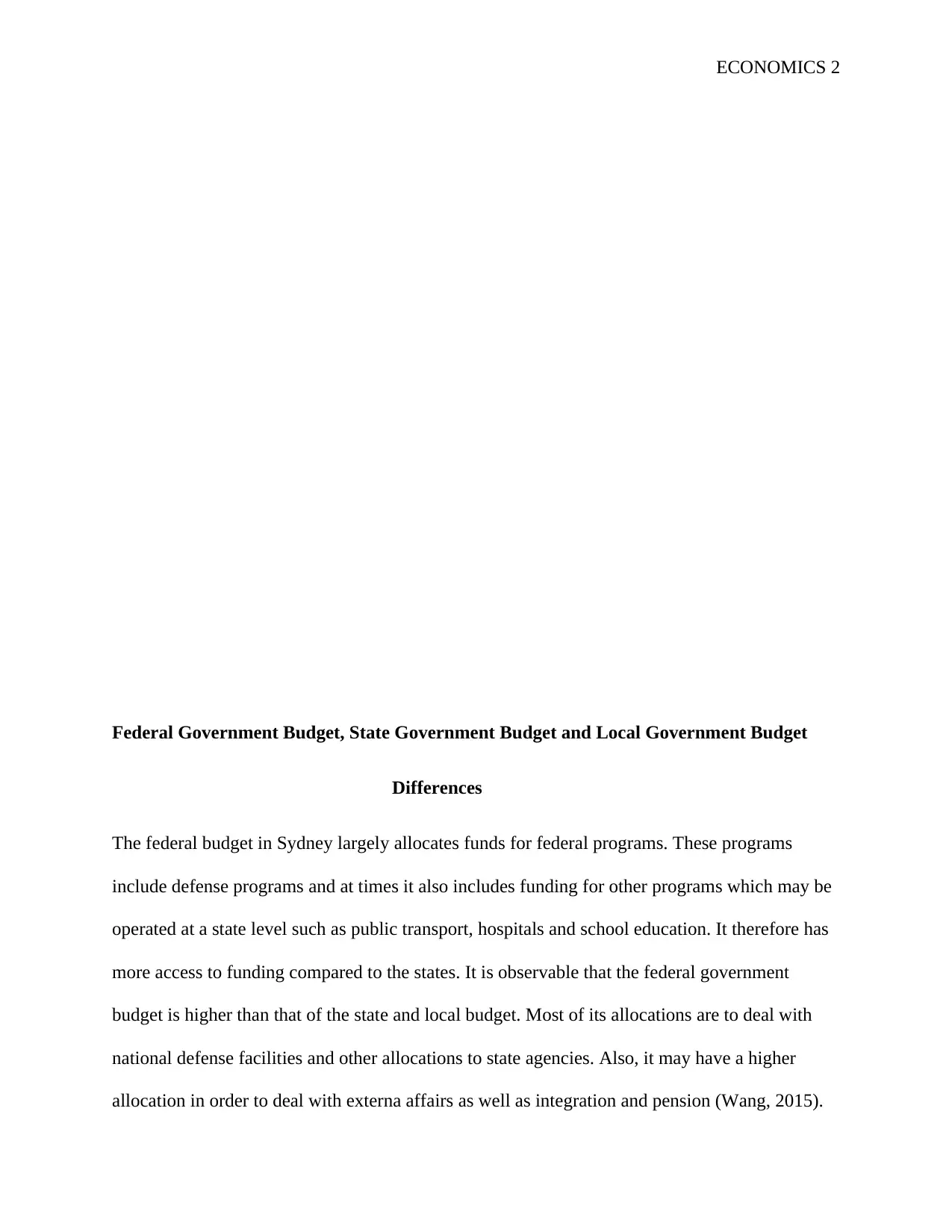

Looking at the revenues, it is clear that the federal government has more allocated funds by

nearly more than half compared to the combination of state allocations. The state allocations are

mostly retrieved from gambling taxes, vehicle tax, payroll taxes and property taxes. On the other

hand, the federal revenues are retrieved from the tax from individuals as well as corporate tax.

Looking at the revenues, it is clear that the federal government has more allocated funds by

nearly more than half compared to the combination of state allocations. The state allocations are

mostly retrieved from gambling taxes, vehicle tax, payroll taxes and property taxes. On the other

hand, the federal revenues are retrieved from the tax from individuals as well as corporate tax.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ECONOMICS 4

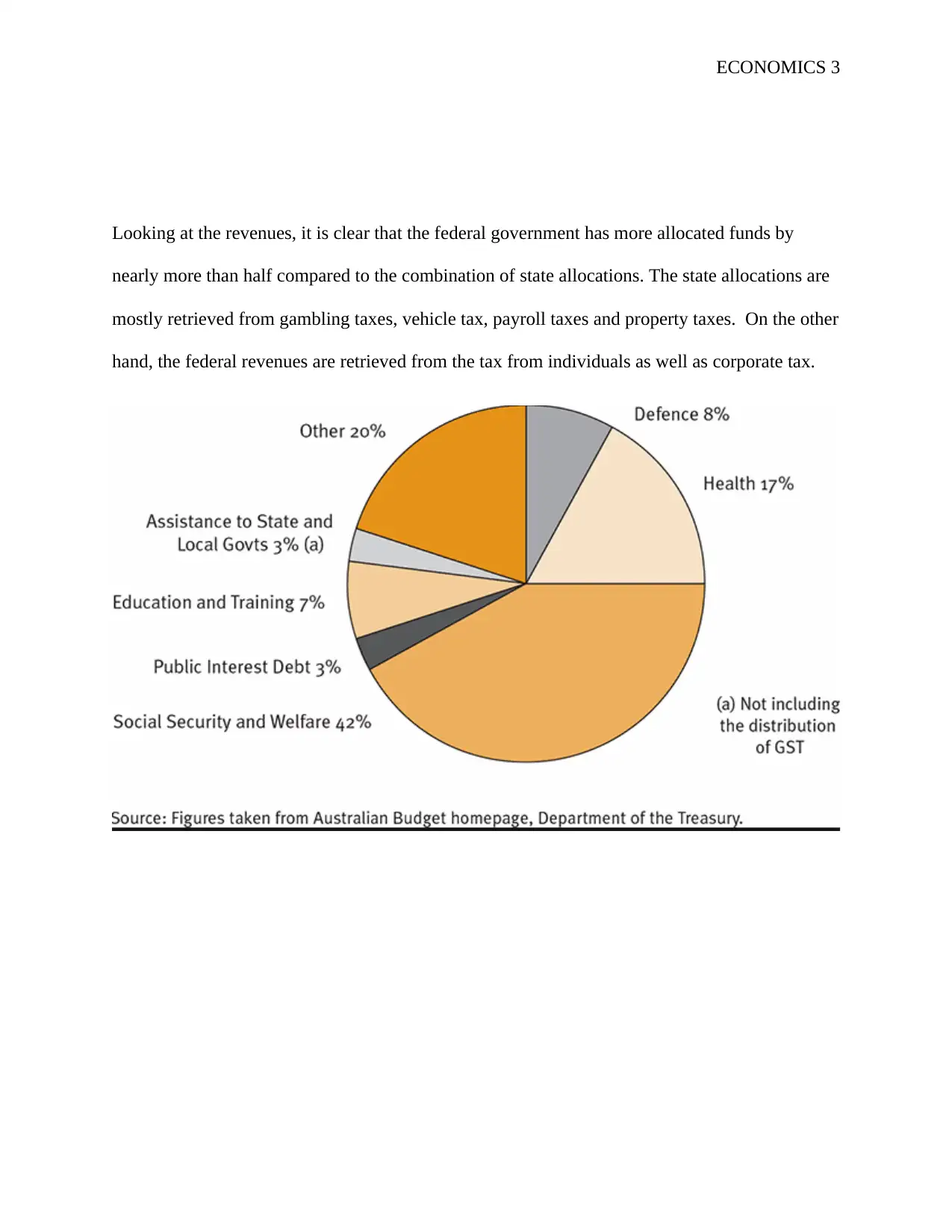

The

headline expenses in the federal budget in Sydney in Sydney include the security and welfare

budget, education, defense, housing, transport and communications. Also, the budgetary

allocations are higher than those of the state budgets (Smith and Williams, 2013). The state

budgets largely deal with social security, housing, transport and communication, education and

health. Subject to a few special cases. Quite, area 90 of the Constitution gives the government

selective control over the lucrative income surges of traditions and extract obligations (imposes

on products, for example, liquor, tobacco and fuel). Until the Second World War, Australians

paid pay duty to both state and governments (Wanna and De Vries, 2015). However since 1942,

the government has been the sole authority of wage charge. The government has additionally

gathered organization assess for more than 100 years, and the GST since 2000. The states could

at present gather wage impose on the off chance that they needed to, yet pick not to for political

reasons. Segment 96 of the Constitution accommodates the national government to give a

The

headline expenses in the federal budget in Sydney in Sydney include the security and welfare

budget, education, defense, housing, transport and communications. Also, the budgetary

allocations are higher than those of the state budgets (Smith and Williams, 2013). The state

budgets largely deal with social security, housing, transport and communication, education and

health. Subject to a few special cases. Quite, area 90 of the Constitution gives the government

selective control over the lucrative income surges of traditions and extract obligations (imposes

on products, for example, liquor, tobacco and fuel). Until the Second World War, Australians

paid pay duty to both state and governments (Wanna and De Vries, 2015). However since 1942,

the government has been the sole authority of wage charge. The government has additionally

gathered organization assess for more than 100 years, and the GST since 2000. The states could

at present gather wage impose on the off chance that they needed to, yet pick not to for political

reasons. Segment 96 of the Constitution accommodates the national government to give a

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECONOMICS 5

noteworthy extent of its income to the states that the Parliament may allow money related help to

any State on such terms and conditions as the Parliament thinks fit. This circulation of income

takes two structures – general income help and installments for a particular reason. The

unfastened financing that states get from the central government is generally comprised of the

cash that the government gathers from the GST. The states can spend this cash as they see fit

(Rubin, 2013). Notwithstanding, the passing on of the GST income is not unqualified. It's

restrictive on the states surrendering the accumulation of a number various states charges. The

perplexing undertaking of cutting up the GST income between the states is left to the

Commonwealth Grants Commission. The yearly procedure dependably appears to leave a

minimum one state guaranteeing it ought to get a more prominent offer of the pie. The

government may likewise give subsidizing to the states to a particular reason. The states need to

agree to getting the subsidizing (which is not ordinarily an issue), but rather it means that the

government can't force programs on the states that they fervently restrict (Reddick and and

Puron-Cid, 2017).

100%

3%

97%

0%

63%

37%

commonwealth state local government

In general, the following differences are highlighted:

noteworthy extent of its income to the states that the Parliament may allow money related help to

any State on such terms and conditions as the Parliament thinks fit. This circulation of income

takes two structures – general income help and installments for a particular reason. The

unfastened financing that states get from the central government is generally comprised of the

cash that the government gathers from the GST. The states can spend this cash as they see fit

(Rubin, 2013). Notwithstanding, the passing on of the GST income is not unqualified. It's

restrictive on the states surrendering the accumulation of a number various states charges. The

perplexing undertaking of cutting up the GST income between the states is left to the

Commonwealth Grants Commission. The yearly procedure dependably appears to leave a

minimum one state guaranteeing it ought to get a more prominent offer of the pie. The

government may likewise give subsidizing to the states to a particular reason. The states need to

agree to getting the subsidizing (which is not ordinarily an issue), but rather it means that the

government can't force programs on the states that they fervently restrict (Reddick and and

Puron-Cid, 2017).

100%

3%

97%

0%

63%

37%

commonwealth state local government

In general, the following differences are highlighted:

ECONOMICS 6

The proportion of the allocations is highest in the federal budget in Sydney

followed by the state budget and the local government budget.

Also, the type of budget is different in the sense that the federal budget mostly

deals with defense issues while state budgets deal with welfare and the local

government budgets mostly deal with public transport and communication.

The other difference concerns the nature of revenues for the budget. It is clear that

while the federal budget obtains its revenues from individual and corporate taxes,

state revenues are obtained from trade excises and levies. The local government

obtains its revenues from licenses, rates and rent (L’Ecuyer and Huffman, 2015).

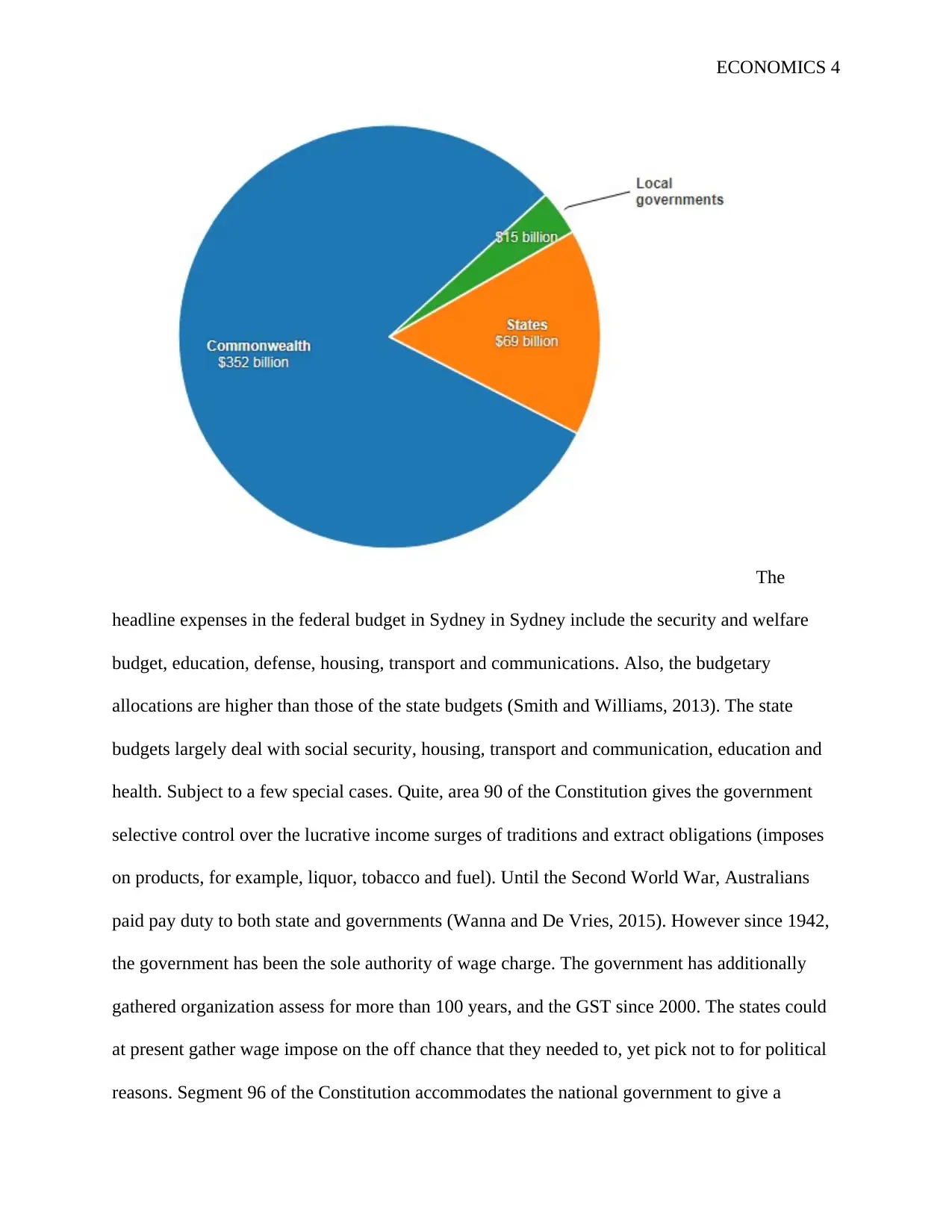

Option

1

y1 y2 y3 y4 y5 y6

Revenu

es 5,000,000.00

10,000,000.

0

15,000,000.0

0

20,000,000.

0

25,000,000.0

0

30,000,000.0

0

Costs

105,000,000.0

0

Operati

ng

profit

(100,000,000.0

0)

10,000,000.

0

15,000,000.0

0 20,000,000.

25,000,000.0

0

30,000,000.0

0

NPV

The proportion of the allocations is highest in the federal budget in Sydney

followed by the state budget and the local government budget.

Also, the type of budget is different in the sense that the federal budget mostly

deals with defense issues while state budgets deal with welfare and the local

government budgets mostly deal with public transport and communication.

The other difference concerns the nature of revenues for the budget. It is clear that

while the federal budget obtains its revenues from individual and corporate taxes,

state revenues are obtained from trade excises and levies. The local government

obtains its revenues from licenses, rates and rent (L’Ecuyer and Huffman, 2015).

Option

1

y1 y2 y3 y4 y5 y6

Revenu

es 5,000,000.00

10,000,000.

0

15,000,000.0

0

20,000,000.

0

25,000,000.0

0

30,000,000.0

0

Costs

105,000,000.0

0

Operati

ng

profit

(100,000,000.0

0)

10,000,000.

0

15,000,000.0

0 20,000,000.

25,000,000.0

0

30,000,000.0

0

NPV

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

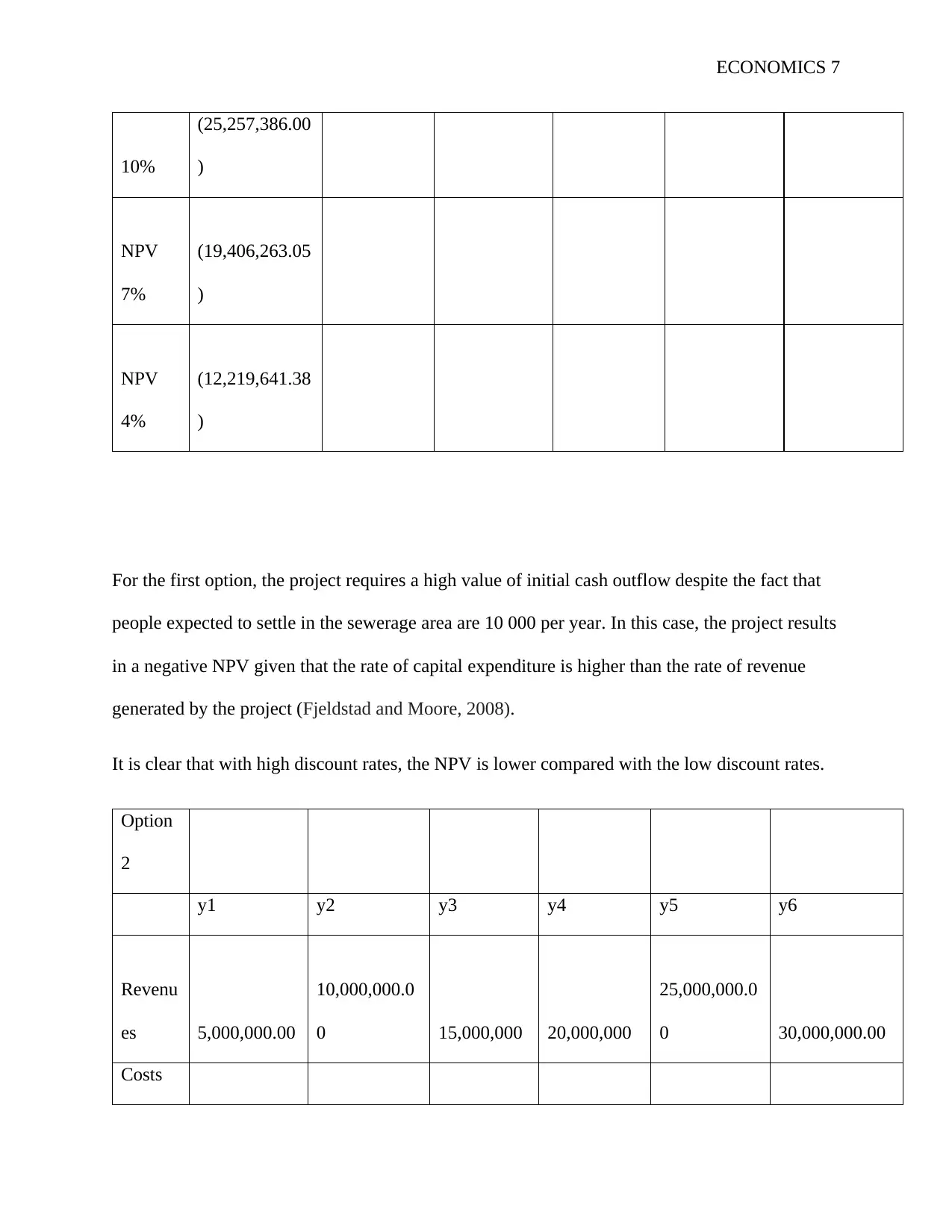

ECONOMICS 7

10%

(25,257,386.00

)

NPV

7%

(19,406,263.05

)

NPV

4%

(12,219,641.38

)

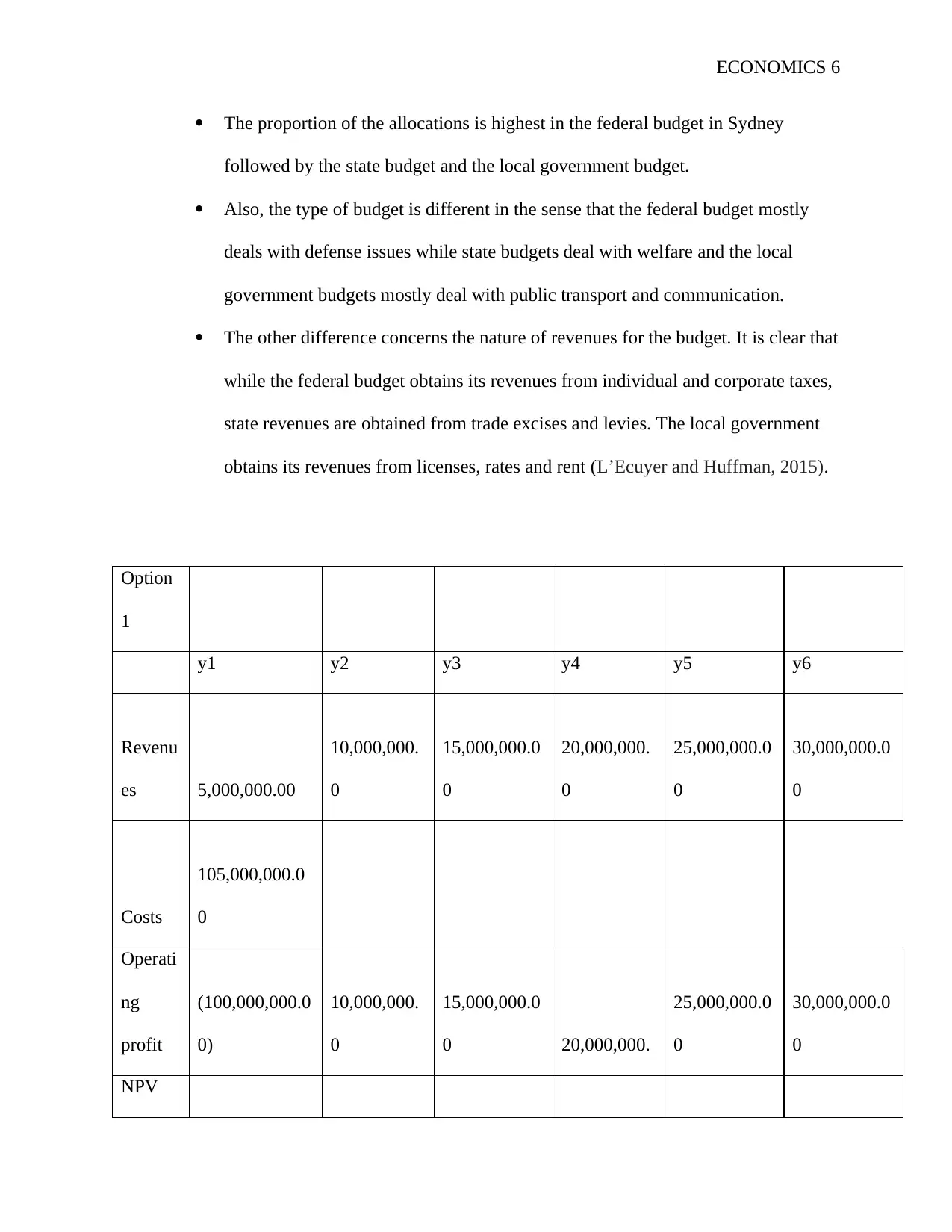

For the first option, the project requires a high value of initial cash outflow despite the fact that

people expected to settle in the sewerage area are 10 000 per year. In this case, the project results

in a negative NPV given that the rate of capital expenditure is higher than the rate of revenue

generated by the project (Fjeldstad and Moore, 2008).

It is clear that with high discount rates, the NPV is lower compared with the low discount rates.

Option

2

y1 y2 y3 y4 y5 y6

Revenu

es 5,000,000.00

10,000,000.0

0 15,000,000 20,000,000

25,000,000.0

0 30,000,000.00

Costs

10%

(25,257,386.00

)

NPV

7%

(19,406,263.05

)

NPV

4%

(12,219,641.38

)

For the first option, the project requires a high value of initial cash outflow despite the fact that

people expected to settle in the sewerage area are 10 000 per year. In this case, the project results

in a negative NPV given that the rate of capital expenditure is higher than the rate of revenue

generated by the project (Fjeldstad and Moore, 2008).

It is clear that with high discount rates, the NPV is lower compared with the low discount rates.

Option

2

y1 y2 y3 y4 y5 y6

Revenu

es 5,000,000.00

10,000,000.0

0 15,000,000 20,000,000

25,000,000.0

0 30,000,000.00

Costs

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

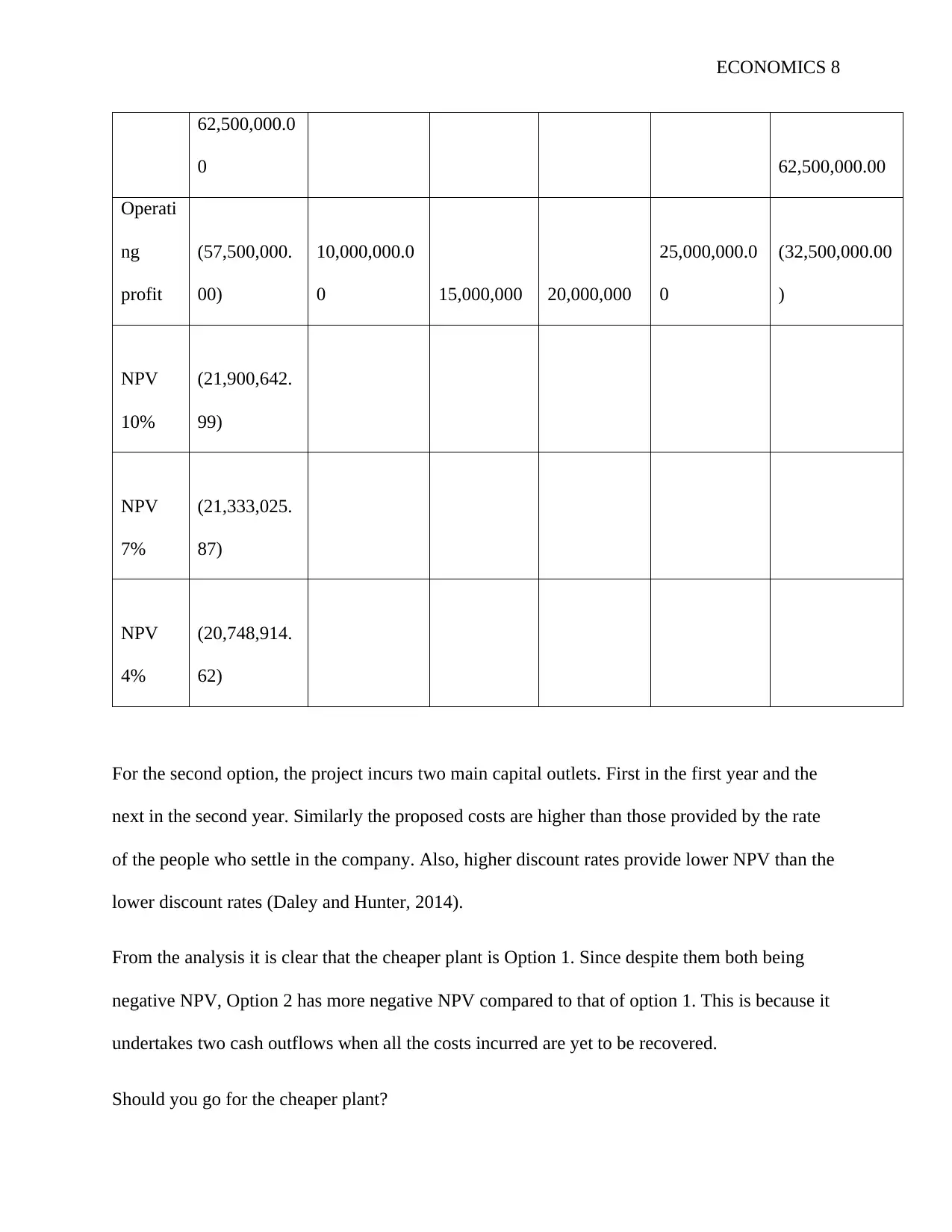

ECONOMICS 8

62,500,000.0

0 62,500,000.00

Operati

ng

profit

(57,500,000.

00)

10,000,000.0

0 15,000,000 20,000,000

25,000,000.0

0

(32,500,000.00

)

NPV

10%

(21,900,642.

99)

NPV

7%

(21,333,025.

87)

NPV

4%

(20,748,914.

62)

For the second option, the project incurs two main capital outlets. First in the first year and the

next in the second year. Similarly the proposed costs are higher than those provided by the rate

of the people who settle in the company. Also, higher discount rates provide lower NPV than the

lower discount rates (Daley and Hunter, 2014).

From the analysis it is clear that the cheaper plant is Option 1. Since despite them both being

negative NPV, Option 2 has more negative NPV compared to that of option 1. This is because it

undertakes two cash outflows when all the costs incurred are yet to be recovered.

Should you go for the cheaper plant?

62,500,000.0

0 62,500,000.00

Operati

ng

profit

(57,500,000.

00)

10,000,000.0

0 15,000,000 20,000,000

25,000,000.0

0

(32,500,000.00

)

NPV

10%

(21,900,642.

99)

NPV

7%

(21,333,025.

87)

NPV

4%

(20,748,914.

62)

For the second option, the project incurs two main capital outlets. First in the first year and the

next in the second year. Similarly the proposed costs are higher than those provided by the rate

of the people who settle in the company. Also, higher discount rates provide lower NPV than the

lower discount rates (Daley and Hunter, 2014).

From the analysis it is clear that the cheaper plant is Option 1. Since despite them both being

negative NPV, Option 2 has more negative NPV compared to that of option 1. This is because it

undertakes two cash outflows when all the costs incurred are yet to be recovered.

Should you go for the cheaper plant?

ECONOMICS 9

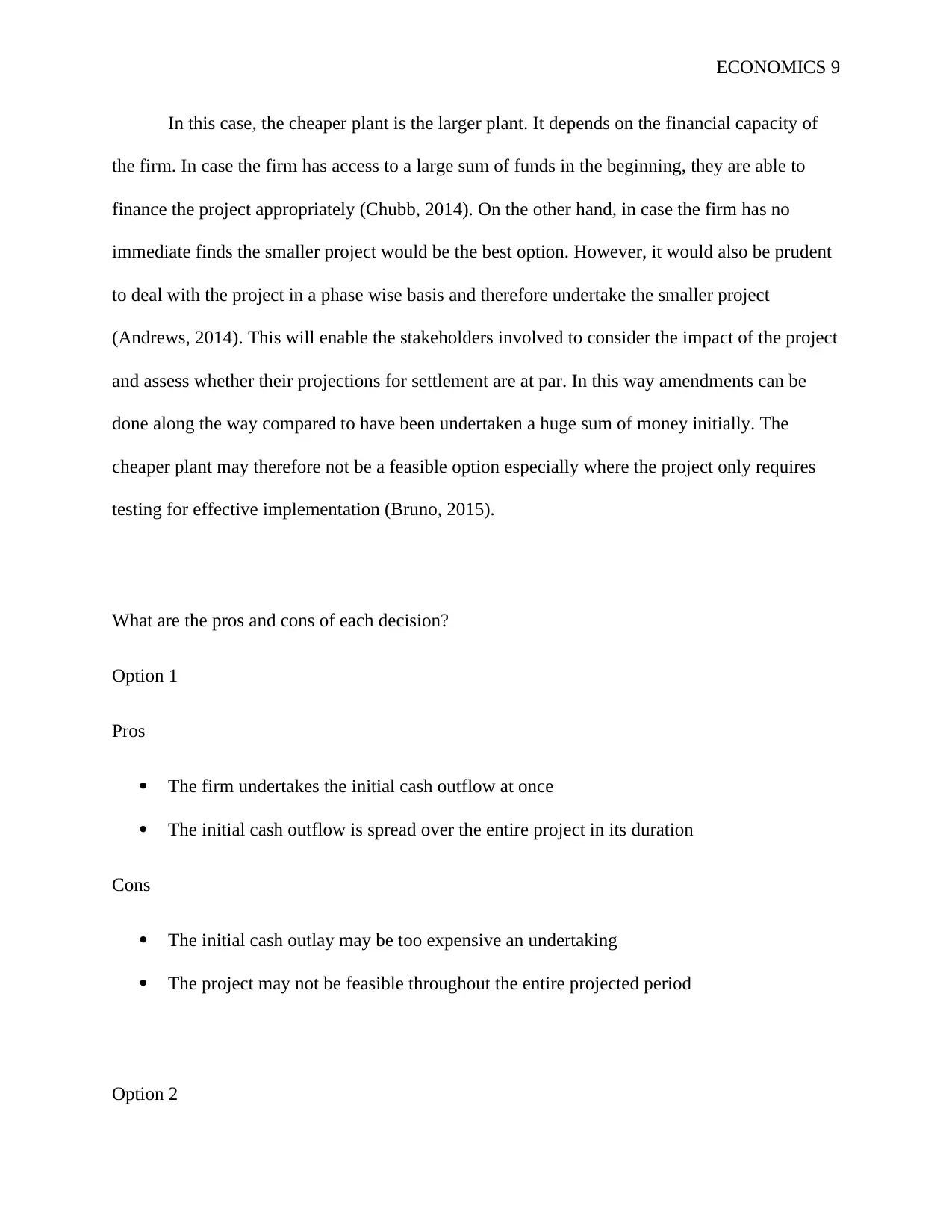

In this case, the cheaper plant is the larger plant. It depends on the financial capacity of

the firm. In case the firm has access to a large sum of funds in the beginning, they are able to

finance the project appropriately (Chubb, 2014). On the other hand, in case the firm has no

immediate finds the smaller project would be the best option. However, it would also be prudent

to deal with the project in a phase wise basis and therefore undertake the smaller project

(Andrews, 2014). This will enable the stakeholders involved to consider the impact of the project

and assess whether their projections for settlement are at par. In this way amendments can be

done along the way compared to have been undertaken a huge sum of money initially. The

cheaper plant may therefore not be a feasible option especially where the project only requires

testing for effective implementation (Bruno, 2015).

What are the pros and cons of each decision?

Option 1

Pros

The firm undertakes the initial cash outflow at once

The initial cash outflow is spread over the entire project in its duration

Cons

The initial cash outlay may be too expensive an undertaking

The project may not be feasible throughout the entire projected period

Option 2

In this case, the cheaper plant is the larger plant. It depends on the financial capacity of

the firm. In case the firm has access to a large sum of funds in the beginning, they are able to

finance the project appropriately (Chubb, 2014). On the other hand, in case the firm has no

immediate finds the smaller project would be the best option. However, it would also be prudent

to deal with the project in a phase wise basis and therefore undertake the smaller project

(Andrews, 2014). This will enable the stakeholders involved to consider the impact of the project

and assess whether their projections for settlement are at par. In this way amendments can be

done along the way compared to have been undertaken a huge sum of money initially. The

cheaper plant may therefore not be a feasible option especially where the project only requires

testing for effective implementation (Bruno, 2015).

What are the pros and cons of each decision?

Option 1

Pros

The firm undertakes the initial cash outflow at once

The initial cash outflow is spread over the entire project in its duration

Cons

The initial cash outlay may be too expensive an undertaking

The project may not be feasible throughout the entire projected period

Option 2

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

ECONOMICS 10

Pros

The firm’s cash outflow is incurred at different points of the project which allows for the

revenues recovered for the second part of the project.

The project can be stopped at any time

Cons

The company undertakes two cash outflows in the project

The project might underestimate the expected settlements in the project which limits the

revenues received.

How do you decide?

I decide on the basis of the feasibility of the project. This is because I believe that it being

a social project it should be able to generate sufficient revenue for the project to fund

itself. I therefore believe that option two is best suited to be selected since it gives the

management the option to opt out and select better alternatives if the method is not

feasible (Smith and Williams, 2013).

Pros

The firm’s cash outflow is incurred at different points of the project which allows for the

revenues recovered for the second part of the project.

The project can be stopped at any time

Cons

The company undertakes two cash outflows in the project

The project might underestimate the expected settlements in the project which limits the

revenues received.

How do you decide?

I decide on the basis of the feasibility of the project. This is because I believe that it being

a social project it should be able to generate sufficient revenue for the project to fund

itself. I therefore believe that option two is best suited to be selected since it gives the

management the option to opt out and select better alternatives if the method is not

feasible (Smith and Williams, 2013).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

ECONOMICS 11

References

Andrews, M., 2014. Budget boost for Australian resources sector. Australia's Paydirt, 1(217),

p.10.

Bruno, R., 2015. Investments in Public Education, Investments in Public Infrastructure, and a

Balanced State Budget.

Chubb, I., 2014. Australia needs a strategy. Science, 345(6200), pp.985-985.

Daley, J., McGannon, C. and Hunter, A., 2014. Budget pressures on Australian governments

2014. Grattan Institute.

Fjeldstad, O.H. and Moore, M., 2008. Tax reform and state building in a globalized

world. Taxation and state-building in developing countries: Capacity and consent, pp.235-260.

L’Ecuyer, T.S., Beaudoing, H.K., Rodell, M., Olson, W., Lin, B., Kato, S., Clayson, C.A.,

Wood, E., Sheffield, J., Adler, R. and Huffman, G., 2015. The observed state of the energy

budget in the early twenty-first century. Journal of Climate, 28(21), pp.8319-8346.

Reddick, C.G., Chatfield, A.T. and Puron-Cid, G., 2017, June. Online Budget Transparency

Innovation in Government: A Case Study of the US State Governments. In Proceedings of the

18th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research (pp. 232-241). ACM.

References

Andrews, M., 2014. Budget boost for Australian resources sector. Australia's Paydirt, 1(217),

p.10.

Bruno, R., 2015. Investments in Public Education, Investments in Public Infrastructure, and a

Balanced State Budget.

Chubb, I., 2014. Australia needs a strategy. Science, 345(6200), pp.985-985.

Daley, J., McGannon, C. and Hunter, A., 2014. Budget pressures on Australian governments

2014. Grattan Institute.

Fjeldstad, O.H. and Moore, M., 2008. Tax reform and state building in a globalized

world. Taxation and state-building in developing countries: Capacity and consent, pp.235-260.

L’Ecuyer, T.S., Beaudoing, H.K., Rodell, M., Olson, W., Lin, B., Kato, S., Clayson, C.A.,

Wood, E., Sheffield, J., Adler, R. and Huffman, G., 2015. The observed state of the energy

budget in the early twenty-first century. Journal of Climate, 28(21), pp.8319-8346.

Reddick, C.G., Chatfield, A.T. and Puron-Cid, G., 2017, June. Online Budget Transparency

Innovation in Government: A Case Study of the US State Governments. In Proceedings of the

18th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research (pp. 232-241). ACM.

ECONOMICS 12

Rubin, I., 2015. Past and future budget classics: A research agenda. Public Administration

Review, 75(1), pp.25-35.

Santamouris, M. ed., 2013. Energy and climate in the urban built environment. Routledge.

Smith, M., Whitelegg, J. and Williams, N.J., 2013. Greening the built environment. Routledge.

Wang, X.S., 2015. The Chinese economy in crisis: state capacity and tax reform. Routledge.

Wanna, J., Lindquist, E.A. and De Vries, J. eds., 2015. The Global Financial Crisis and Its

Budget Impacts in OECD Nations: Fiscal Responses and Future Challenges. Edward Elgar

Publishing.

Rubin, I., 2015. Past and future budget classics: A research agenda. Public Administration

Review, 75(1), pp.25-35.

Santamouris, M. ed., 2013. Energy and climate in the urban built environment. Routledge.

Smith, M., Whitelegg, J. and Williams, N.J., 2013. Greening the built environment. Routledge.

Wang, X.S., 2015. The Chinese economy in crisis: state capacity and tax reform. Routledge.

Wanna, J., Lindquist, E.A. and De Vries, J. eds., 2015. The Global Financial Crisis and Its

Budget Impacts in OECD Nations: Fiscal Responses and Future Challenges. Edward Elgar

Publishing.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.