Engineering Analysis: Ground Source Heat Pump Systems & Climate

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/11

|15

|3592

|72

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an in-depth analysis of Ground Source Heat Pump (GSHP) systems, covering their operational principles, major components like ground loops, heat pumps, and distribution systems, and various types including closed-loop (vertical, horizontal, slinky, pond) and open-loop systems. It discusses factors affecting GSHP operations, such as Seasonal Performance Factor, and explores the application of these systems in hot and dry climates, referencing studies conducted in regions like Saudi Arabia. The report highlights the temperature profiles, soil properties, and cost analyses associated with GSHP implementation, emphasizing the potential for energy savings and the importance of considering geological and economic factors. It also notes the advantages and disadvantages of different loop configurations, providing a comprehensive overview of GSHP technology and its practical considerations.

ENGINEERING

[Author Name(s), First M. Last, Omit Titles and Degrees]

[Institutional Affiliation(s)]

[Author Name(s), First M. Last, Omit Titles and Degrees]

[Institutional Affiliation(s)]

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2.4 Principle of operation of GSHP

Ground Source Heat Pumps are systems that consist of three major elements; (a) the ground loop

major element that is includes in the GSHP system. A schematic representation of the operation

of the GSHP system is given in the figure 2.1. In detail, the GSHP contains a ground loop

(ground heat exchanger GHE), a heat pump unit and distribution system. In addition to this a

refrigeration system is also included in a GSHP system.

2.4.1 Ground Loop

The Ground loop is formed by a connection of network which is a closed loop and an outlet

structure known as open loop which is located underground or underwater. The entire set up of

the ground loop is always located outside the building footprint. Collecting the heat from the

ground water or the ground and disposing the heat to the ground or ground water is the main

function of ground loop (Bonin, 2015). This function of the ground loop is accomplished when

circulating a fluid through pipes. In the submerged pipes, working fluid is made to circulate and

the groundwater is also taken out of the ground loop.

2.4.2 Heat pump

Heat is transferred by a heat pump from a fluid with a low temperature and passes it at very high

temperature to another fluid; a heat pump may also be used. From low to high temperature; heat

is transferred a by heat pump that is Heat collected in the ground is transferred to the application

using refrigeration where the ground is used as the heat source. The discharged heat is

transferred from the building to the ground in the cooling mode (Ghosh, 2011).

Ground Source Heat Pumps are systems that consist of three major elements; (a) the ground loop

major element that is includes in the GSHP system. A schematic representation of the operation

of the GSHP system is given in the figure 2.1. In detail, the GSHP contains a ground loop

(ground heat exchanger GHE), a heat pump unit and distribution system. In addition to this a

refrigeration system is also included in a GSHP system.

2.4.1 Ground Loop

The Ground loop is formed by a connection of network which is a closed loop and an outlet

structure known as open loop which is located underground or underwater. The entire set up of

the ground loop is always located outside the building footprint. Collecting the heat from the

ground water or the ground and disposing the heat to the ground or ground water is the main

function of ground loop (Bonin, 2015). This function of the ground loop is accomplished when

circulating a fluid through pipes. In the submerged pipes, working fluid is made to circulate and

the groundwater is also taken out of the ground loop.

2.4.2 Heat pump

Heat is transferred by a heat pump from a fluid with a low temperature and passes it at very high

temperature to another fluid; a heat pump may also be used. From low to high temperature; heat

is transferred a by heat pump that is Heat collected in the ground is transferred to the application

using refrigeration where the ground is used as the heat source. The discharged heat is

transferred from the building to the ground in the cooling mode (Ghosh, 2011).

2.4.3 Distribution System

The major function of a distribution system is to distribute heat to the application and the heat

from the application is also removed by a distribution system. Consider heating a swimming pool

which is the best example of the distribution system. A good example is heating the swimming

pool.

2.4 Factors effect GSHP operations

For the ground source heat pump, the Seasonal Performance Factor is always about 4 and ground

source heat pumps are much more efficient for the heating season.

2.5 Types of Geothermal Heat Pump Systems

Based on the set up or installation surface of the GSHP can be classified into several categories.

A GSPH can be installed above the surface of the ground about 20 meters from the surface the

ground. When a GSHP is installed below the ground surface and the distance is not more than 20

meter then it is said to be superficial shallow (Bonin, 2015). A GSHP be installed between 30

meter to 400 meter under the ground surface and this is defined as shallow ground. Ground

Source and Heat Pump can be installed in two ways which are termed as a closed loop and an

open loop.

2.5.1 Closed loop systems

Heat transfer in the closed loop systems does not have any direct contact with the ground and the

loop fluid for the heat transfer is enclosed. Further, There will is direct contact of the closed

loop system with the ground and Pipe is installed and it is only through the piping that the heat

The major function of a distribution system is to distribute heat to the application and the heat

from the application is also removed by a distribution system. Consider heating a swimming pool

which is the best example of the distribution system. A good example is heating the swimming

pool.

2.4 Factors effect GSHP operations

For the ground source heat pump, the Seasonal Performance Factor is always about 4 and ground

source heat pumps are much more efficient for the heating season.

2.5 Types of Geothermal Heat Pump Systems

Based on the set up or installation surface of the GSHP can be classified into several categories.

A GSPH can be installed above the surface of the ground about 20 meters from the surface the

ground. When a GSHP is installed below the ground surface and the distance is not more than 20

meter then it is said to be superficial shallow (Bonin, 2015). A GSHP be installed between 30

meter to 400 meter under the ground surface and this is defined as shallow ground. Ground

Source and Heat Pump can be installed in two ways which are termed as a closed loop and an

open loop.

2.5.1 Closed loop systems

Heat transfer in the closed loop systems does not have any direct contact with the ground and the

loop fluid for the heat transfer is enclosed. Further, There will is direct contact of the closed

loop system with the ground and Pipe is installed and it is only through the piping that the heat

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

transfer occurs (Rees, 2016). This closed loop is classified into different types, one is a vertically

closed loop, and the other one is horizontally closed loop. Slinky or spiral closed loops and in

addition to closed pond loops are other types of closed loop systems. For all these types the

configuration of the system and the space requirement varies and the installation depth varies

from one type to other type in closed loop systems.

2.5.1 .1 Vertical closed loop

A vertical closed loop, ground bores has to be constructed and it contains vertical oriented heat

exchange pipes. For residential application a bore hole ranging in size from 45 to 75 meter depth

is usually require but for industrial application then above 150 meter depth bore hole is usually

constructed (RSES, 2011). Thermal contact has to be maintained between the heat exchanger and

the borehole wall. Entire gap around the borehole is filled with enhanced cement or sand but

betonies can also be used to fill the gap. In the heat exchanger, the fluid is circulated and

transfers the heat from ground to the heat pump and again from heat pump heat is transferred to

the ground. This process exchanges heat in the ground surface. Based on the type of the heat

exchanger and grouting material employed, the thermal efficiency of BHE varies and

performance of the BHE is based on the initial ground temperature (Orio, 2013). The hydraulic

properties and ground properties also impact on the performance of the BHE. In general, vertical

loop system is more advantageous for large applications but it has the major disadvantage of the

large installation cost. Further in the installation cost is high in the vertical than horizontal closed

loop.

2.5.1.2 Horizontal closed loop

closed loop, and the other one is horizontally closed loop. Slinky or spiral closed loops and in

addition to closed pond loops are other types of closed loop systems. For all these types the

configuration of the system and the space requirement varies and the installation depth varies

from one type to other type in closed loop systems.

2.5.1 .1 Vertical closed loop

A vertical closed loop, ground bores has to be constructed and it contains vertical oriented heat

exchange pipes. For residential application a bore hole ranging in size from 45 to 75 meter depth

is usually require but for industrial application then above 150 meter depth bore hole is usually

constructed (RSES, 2011). Thermal contact has to be maintained between the heat exchanger and

the borehole wall. Entire gap around the borehole is filled with enhanced cement or sand but

betonies can also be used to fill the gap. In the heat exchanger, the fluid is circulated and

transfers the heat from ground to the heat pump and again from heat pump heat is transferred to

the ground. This process exchanges heat in the ground surface. Based on the type of the heat

exchanger and grouting material employed, the thermal efficiency of BHE varies and

performance of the BHE is based on the initial ground temperature (Orio, 2013). The hydraulic

properties and ground properties also impact on the performance of the BHE. In general, vertical

loop system is more advantageous for large applications but it has the major disadvantage of the

large installation cost. Further in the installation cost is high in the vertical than horizontal closed

loop.

2.5.1.2 Horizontal closed loop

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The Heat exchange well contains a loop of piping which is horizontally installed and usually

within 15 feet below the ground surface. A Horizontal closed loop is considerably about 30

percent in a vertical closed loop and several factors have an impact on the cost, namely.

Poor (geology): a larger collector field is required if the geology is poor.

Collector protection: Protection has to be given for the horizontal collector against

sharp stocks (Chiasson, 2016).

Excavation trenches the amount of time spent must be considered.

Landscaping; the ground is a factor.

These factors reduce the cost of the installation of horizontal closed loops; however the exact

costs can only be calculated after a thorough geological investigation the area undertaken.

2.5.1.3 Slinky closed loop

A slinky closed loop, or spiral loop, is horizontal oriented loop within shallow trenches and

therefore resembles to a conventional horizontal loop. The piping in the slinky closed loop is laid

out as circular loops and therefore requires a smaller area when compared to a horizontal closed

loop and in slinky loop at the end return pipe is attached to the heat pump and the system

requires a huge amount of piping in order to carry on with the load. A spiral GHE can either be

fixed vertically or horizontally (Silberstein, 2015). The heat transfer is low in spiral GHE which

is the major disadvantage of using that system. However slinky supports high pumping, due to

the added pipe length and this is the main advantage of using the system.

2.5.1.4 Closed pond loop

A geothermal long pipe is defined as a closed pond loop and this pipe is attached and placed

inside a lake or a water source. The loop has to be completely immersed in the water and

within 15 feet below the ground surface. A Horizontal closed loop is considerably about 30

percent in a vertical closed loop and several factors have an impact on the cost, namely.

Poor (geology): a larger collector field is required if the geology is poor.

Collector protection: Protection has to be given for the horizontal collector against

sharp stocks (Chiasson, 2016).

Excavation trenches the amount of time spent must be considered.

Landscaping; the ground is a factor.

These factors reduce the cost of the installation of horizontal closed loops; however the exact

costs can only be calculated after a thorough geological investigation the area undertaken.

2.5.1.3 Slinky closed loop

A slinky closed loop, or spiral loop, is horizontal oriented loop within shallow trenches and

therefore resembles to a conventional horizontal loop. The piping in the slinky closed loop is laid

out as circular loops and therefore requires a smaller area when compared to a horizontal closed

loop and in slinky loop at the end return pipe is attached to the heat pump and the system

requires a huge amount of piping in order to carry on with the load. A spiral GHE can either be

fixed vertically or horizontally (Silberstein, 2015). The heat transfer is low in spiral GHE which

is the major disadvantage of using that system. However slinky supports high pumping, due to

the added pipe length and this is the main advantage of using the system.

2.5.1.4 Closed pond loop

A geothermal long pipe is defined as a closed pond loop and this pipe is attached and placed

inside a lake or a water source. The loop has to be completely immersed in the water and

installed in such a way that it is about 8 feet above the pond loop. Further, the pond or lake,

which has larger volume, can only be used for the installation of the closed pond loop. The coils

of pond loop are connected to the skid and installed under the water in order to prevent from

freezing.

2.5.2 Open loop systems

In general for large commercial applications an open loop system is used as the system directly

interacts with the ground (Kavanaugh, 2014). Groundwater or surface water is used as a direct

heat transfer medium in open loop systems and system requires a huge groundwater source for

its operation and as the result it is not suitable for all locations. The water from the lake or

groundwater is directly extracted and sent to the heat exchange pipe and after the heat exchange

is achieved then discharged back to the source of water the through a separate pipe. The issue

that has to be investigated in the installation of an open loop system is if there is sufficient

groundwater available. Thus installation cost of an open loop system is very low when sufficient

ground water is availability (Kavanaugh, 2014). An open loop system has a high coefficient of

performance and the system is considered to be an environment friendly system since the heat

carrying medium is in direct contact with the ground.

2.6 Ground source heat pumps in hot and dry climates

As part of the assessment, a literature review of hot and dry climates where ground coupled heat

exchangers have been used is investigated in order to determine the temperature profiles and soil

properties required for the performance of these heat exchangers. Hot and dry climates are

encountered in vast regions across the globe but, unfortunately, not much data exists in terms of

borehole temperatures at various depths in hot and dry climates. The following studies have been

which has larger volume, can only be used for the installation of the closed pond loop. The coils

of pond loop are connected to the skid and installed under the water in order to prevent from

freezing.

2.5.2 Open loop systems

In general for large commercial applications an open loop system is used as the system directly

interacts with the ground (Kavanaugh, 2014). Groundwater or surface water is used as a direct

heat transfer medium in open loop systems and system requires a huge groundwater source for

its operation and as the result it is not suitable for all locations. The water from the lake or

groundwater is directly extracted and sent to the heat exchange pipe and after the heat exchange

is achieved then discharged back to the source of water the through a separate pipe. The issue

that has to be investigated in the installation of an open loop system is if there is sufficient

groundwater available. Thus installation cost of an open loop system is very low when sufficient

ground water is availability (Kavanaugh, 2014). An open loop system has a high coefficient of

performance and the system is considered to be an environment friendly system since the heat

carrying medium is in direct contact with the ground.

2.6 Ground source heat pumps in hot and dry climates

As part of the assessment, a literature review of hot and dry climates where ground coupled heat

exchangers have been used is investigated in order to determine the temperature profiles and soil

properties required for the performance of these heat exchangers. Hot and dry climates are

encountered in vast regions across the globe but, unfortunately, not much data exists in terms of

borehole temperatures at various depths in hot and dry climates. The following studies have been

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

assessed in order to qualitatively assess the available literature such that it may form part of the

assessment (Lloyd, 2016). A synopsis of how this is relevant in investigation has also been

evaluated.

2.6.1 Saudi Arabia

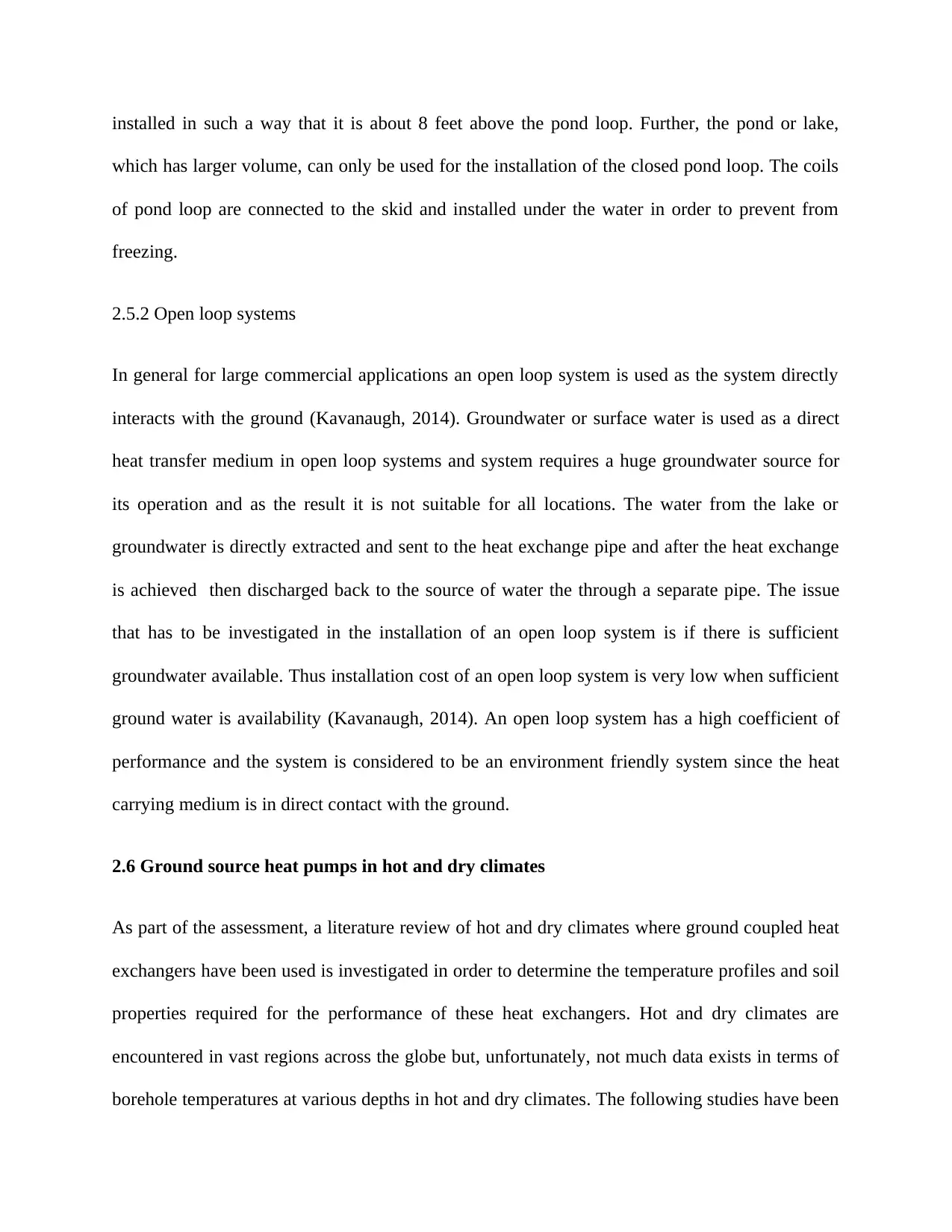

An assessment into the feasibility of using ground-coupled condensers for air-conditioning (A/C)

systems in Saudi Arabia was investigated (Said et al., 2010). The temperatures and soil

properties required for the performance analysis of one of these condensers was determined

experimentally and thermal response tests were conducted to evaluate the effective thermal

conductivity of the ground. The measurements undertaken as part of this investigation revealed

significant differences between the ambient air and the ground temperatures, which results in an

increase in the coefficient of performance and in a reduction in the energy consumption of an

A/C unit when using a vertical ground heat exchanger rather than an air-cooled condenser which

is the existing norm in the country (Ghosh, 2011). A maximum difference of about 12oC was

observed between the ground temperature and the dry bulb temperature of the ambient air. A

steady-state value of 32.5oC for the mean borehole temperature was reached.

A cost analysis was also undertaken by investigators and this indicated that the use of ground-

source heat pumps in Saudi Arabia would result in about 28% energy savings should ground

coupled heat pumps be utilized over the use of the ambient air. However it was deemed not

economically viable due to the low electricity prices that were prevalent in the country due to

government subsidies and high drilling costs.

assessment (Lloyd, 2016). A synopsis of how this is relevant in investigation has also been

evaluated.

2.6.1 Saudi Arabia

An assessment into the feasibility of using ground-coupled condensers for air-conditioning (A/C)

systems in Saudi Arabia was investigated (Said et al., 2010). The temperatures and soil

properties required for the performance analysis of one of these condensers was determined

experimentally and thermal response tests were conducted to evaluate the effective thermal

conductivity of the ground. The measurements undertaken as part of this investigation revealed

significant differences between the ambient air and the ground temperatures, which results in an

increase in the coefficient of performance and in a reduction in the energy consumption of an

A/C unit when using a vertical ground heat exchanger rather than an air-cooled condenser which

is the existing norm in the country (Ghosh, 2011). A maximum difference of about 12oC was

observed between the ground temperature and the dry bulb temperature of the ambient air. A

steady-state value of 32.5oC for the mean borehole temperature was reached.

A cost analysis was also undertaken by investigators and this indicated that the use of ground-

source heat pumps in Saudi Arabia would result in about 28% energy savings should ground

coupled heat pumps be utilized over the use of the ambient air. However it was deemed not

economically viable due to the low electricity prices that were prevalent in the country due to

government subsidies and high drilling costs.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

The study highlighted some salient aspects to note which are relevant in our study

I. There is a significant temperature difference between the ambient air and the ground that

will favors the performance of GHXs over that of air-cooled condensers.

II. The ground temperature in the KSA does not change significantly below about 30m

depth throughout the year.

III. A performance analysis indicated an increase in the COP, and a reduction in the energy

consumption of an A/C unit, when using a vertical GHX instead of an air-cooled

condenser and this resulting in energy savings of about 28%.

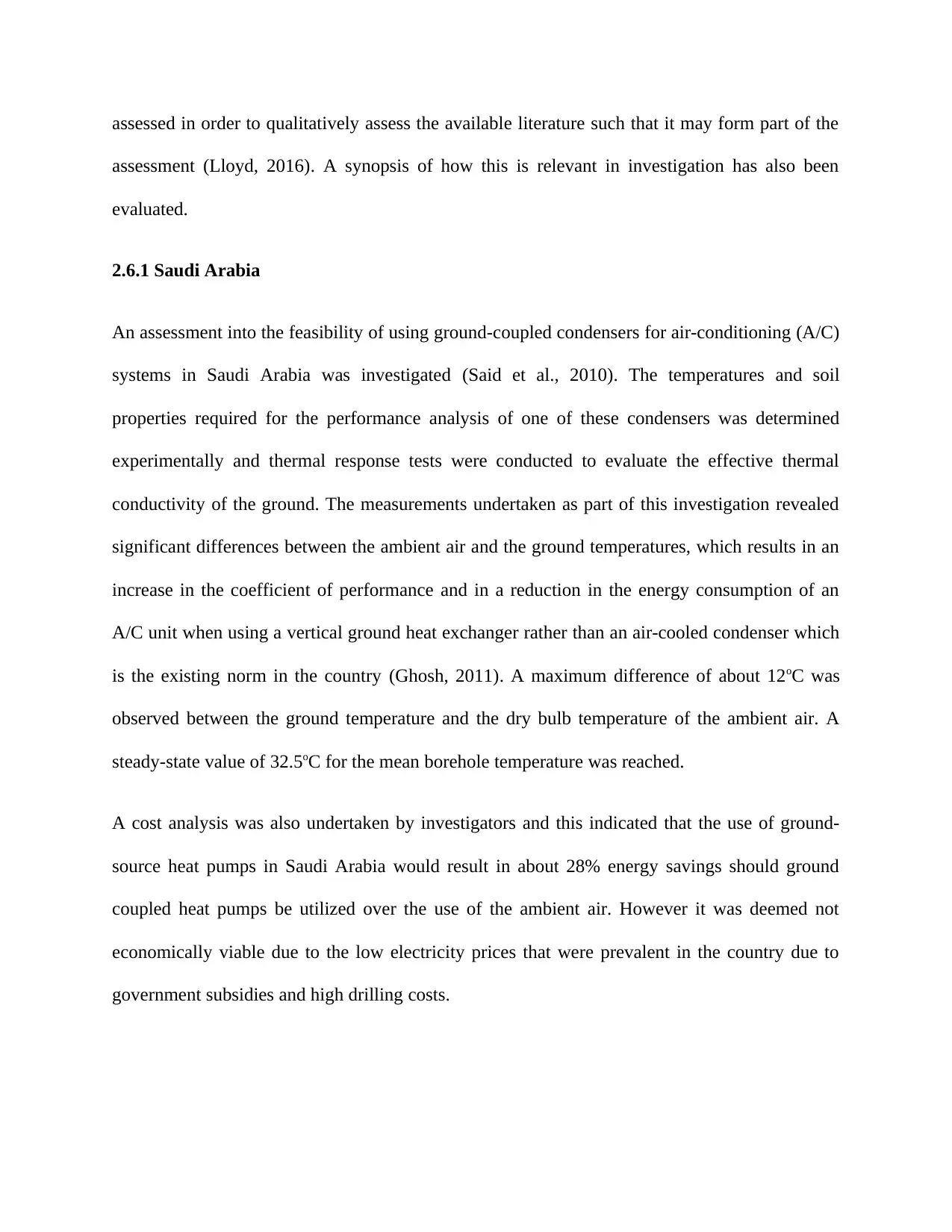

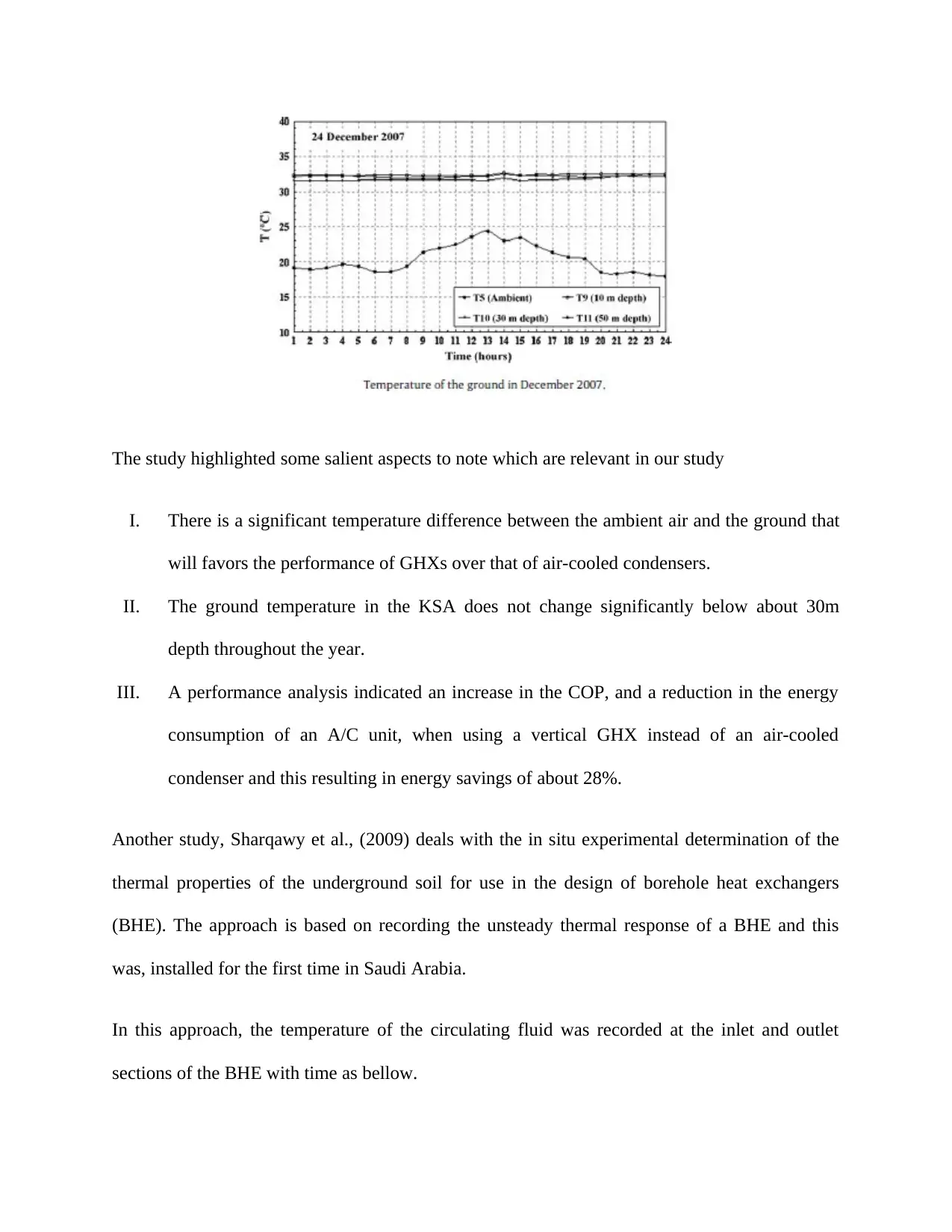

Another study, Sharqawy et al., (2009) deals with the in situ experimental determination of the

thermal properties of the underground soil for use in the design of borehole heat exchangers

(BHE). The approach is based on recording the unsteady thermal response of a BHE and this

was, installed for the first time in Saudi Arabia.

In this approach, the temperature of the circulating fluid was recorded at the inlet and outlet

sections of the BHE with time as bellow.

I. There is a significant temperature difference between the ambient air and the ground that

will favors the performance of GHXs over that of air-cooled condensers.

II. The ground temperature in the KSA does not change significantly below about 30m

depth throughout the year.

III. A performance analysis indicated an increase in the COP, and a reduction in the energy

consumption of an A/C unit, when using a vertical GHX instead of an air-cooled

condenser and this resulting in energy savings of about 28%.

Another study, Sharqawy et al., (2009) deals with the in situ experimental determination of the

thermal properties of the underground soil for use in the design of borehole heat exchangers

(BHE). The approach is based on recording the unsteady thermal response of a BHE and this

was, installed for the first time in Saudi Arabia.

In this approach, the temperature of the circulating fluid was recorded at the inlet and outlet

sections of the BHE with time as bellow.

The survey revealed typical costs of a drilling of oil borehole drillers and this can be as high as

$300 per meter of borehole depth but for water well drilling cost much less since it used a rotary

drilling rig and the averaged cost is about at $50 per meter.

The recorded thermal responses, together with the development of a simple line source theory,

were used to determine the thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity and the steady-state

equivalent thermal resistance of the underground soil.

$300 per meter of borehole depth but for water well drilling cost much less since it used a rotary

drilling rig and the averaged cost is about at $50 per meter.

The recorded thermal responses, together with the development of a simple line source theory,

were used to determine the thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity and the steady-state

equivalent thermal resistance of the underground soil.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

This was the first experience at representing a step towards a more detailed study on the effective

thermal properties of soil in different location in Saudi Arabia with a view to possible practical

applications of geothermal energy in the region.

From the experience accumulated from the results obtained by the report the following

conclusions may be

(a) A new approach was introduced in the assessment of a thermal response test data. In this

approach, it was possible to determine the time before which some experimental data could be

excluded to minimize the error associated with the line source model without knowing the value

of the thermal diffusivity v. In addition, the value of soil thermal diffusivity could be obtained as

well as the thermal conductivity and thermal resistance (Energy, 2014).

(b) For the selected site, the BHE effective values of 2.154 (W/m K), 6.252 x 10-6 (m2/s) and

0.315 (m K/W) were determined for the soil thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity and

thermal resistance, respectively.

2.6.2 Erbil, Iraq

Due to the wide and varied climatic and soil conditions encountered in Saudi Arabia, a literature

review of hence conditions in Erbil, Iraq was performed. This area has more northern latitude

than Saudi Arabia but it closely resembles the dry mountainous region of Hejaz which forms a

natural barrier running parallel to the Saudi coastline from Yemen in the south to Jordan in the

North (CHUN-KWONG, 2017).

Investigate the storage technology used to save energy for a school building in Erbil, Iraq and

this covers different storage methods that are used in Iraq for energy storage. The assessment

thermal properties of soil in different location in Saudi Arabia with a view to possible practical

applications of geothermal energy in the region.

From the experience accumulated from the results obtained by the report the following

conclusions may be

(a) A new approach was introduced in the assessment of a thermal response test data. In this

approach, it was possible to determine the time before which some experimental data could be

excluded to minimize the error associated with the line source model without knowing the value

of the thermal diffusivity v. In addition, the value of soil thermal diffusivity could be obtained as

well as the thermal conductivity and thermal resistance (Energy, 2014).

(b) For the selected site, the BHE effective values of 2.154 (W/m K), 6.252 x 10-6 (m2/s) and

0.315 (m K/W) were determined for the soil thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity and

thermal resistance, respectively.

2.6.2 Erbil, Iraq

Due to the wide and varied climatic and soil conditions encountered in Saudi Arabia, a literature

review of hence conditions in Erbil, Iraq was performed. This area has more northern latitude

than Saudi Arabia but it closely resembles the dry mountainous region of Hejaz which forms a

natural barrier running parallel to the Saudi coastline from Yemen in the south to Jordan in the

North (CHUN-KWONG, 2017).

Investigate the storage technology used to save energy for a school building in Erbil, Iraq and

this covers different storage methods that are used in Iraq for energy storage. The assessment

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

covered a borehole thermal energy storage system in an underground structure for large

quantities of heat and cooled energy in the soil and rocks. The Earth energy design 2.0 PC-

Program was used for the borehole design and test building consisted of six class rooms within

the school with a total build area of about 1200m2, a height was 3m and a total volume 0f

3600m3. The annual mean temperature was calculated at 20.95OC and a degree hour method was

used to calculate the energy demand above the base temperature 17OC for heating and 20OC for

cooling (Ochsner, 2012). The required maximum power demand for heating was calculated at

158.4kW and the maximum power demand for cooling the building is 211.2kW based on the

climatic yearly extremes experienced in Erbil. The months from November until April were used

for calculating the total heating demand for the school building, and this was calculated to be

254,52MWh.

The months of May until September were used for calculating the total cooling demand for the

building, and it was calculated to be 10MWh. The month of October had a mild climate which

required no heating or cooling.

Erbil has been selected in our study due to a pervasive mountainous terrain which is similar to

the dry mountainous region in Hejaz which forms part of eastern Saudi Arabia. It is envisaged

that a similar borehole thermal energy storage system could be adopted in eastern Saudi Arabia.

2.6.3 Tunisia

The aim of this study by Naili et al., (2012) was first to evaluate the Tunisian geothermal energy

potential and to test the performance of a horizontal ground heat exchanger.

quantities of heat and cooled energy in the soil and rocks. The Earth energy design 2.0 PC-

Program was used for the borehole design and test building consisted of six class rooms within

the school with a total build area of about 1200m2, a height was 3m and a total volume 0f

3600m3. The annual mean temperature was calculated at 20.95OC and a degree hour method was

used to calculate the energy demand above the base temperature 17OC for heating and 20OC for

cooling (Ochsner, 2012). The required maximum power demand for heating was calculated at

158.4kW and the maximum power demand for cooling the building is 211.2kW based on the

climatic yearly extremes experienced in Erbil. The months from November until April were used

for calculating the total heating demand for the school building, and this was calculated to be

254,52MWh.

The months of May until September were used for calculating the total cooling demand for the

building, and it was calculated to be 10MWh. The month of October had a mild climate which

required no heating or cooling.

Erbil has been selected in our study due to a pervasive mountainous terrain which is similar to

the dry mountainous region in Hejaz which forms part of eastern Saudi Arabia. It is envisaged

that a similar borehole thermal energy storage system could be adopted in eastern Saudi Arabia.

2.6.3 Tunisia

The aim of this study by Naili et al., (2012) was first to evaluate the Tunisian geothermal energy

potential and to test the performance of a horizontal ground heat exchanger.

An experimental set-up was constructed for the climatic conditions in the Bork Cedria region

which is located in the north of Tunisia. The ground temperature at several depths was measured,

and the overall heat transfer coefficient (U) was determined.

The heat exchange rate was quantified, and the pressure losses were calculated. The total heat

rejected by using the ground heat exchanger (GHE) system was compared to the total

requirements of a tested room with a 12 m2 surface. The results showed that the GHE, with a 25

m of length buried at 1 m depth and this covered about 38% of the total cooling requirement of

the tested room.

This study showed that the ground heat exchanger could provide a new way of cooling buildings,

and also showed it that Tunisia has an important geothermal potential which could allow Tunisia

to be a pioneer in the exploitation of geothermal energy for the installation of ground source heat

pump systems (Chiasson, 2016).

While Tunisia is at more northern latitude than Saudi Arabia, it does but share similar climatic

conditions. The feasibility of horizontal borehole heat pumps can be utilized as a cooling

requirement of up to 38% can be realized at shallow depths of 1m and this could be considered

for standalone borehole heat pump applications (Orio, 2013).

Chapter 3: Ground Source Heat Pump Modeling

3.1 Introduction

One of the fundamental tasks in the design of a reliable ground-coupled heat pump system is the

proper sizing of the ground-coupled heat exchanger length i.e. the depth of borehole. Recent

which is located in the north of Tunisia. The ground temperature at several depths was measured,

and the overall heat transfer coefficient (U) was determined.

The heat exchange rate was quantified, and the pressure losses were calculated. The total heat

rejected by using the ground heat exchanger (GHE) system was compared to the total

requirements of a tested room with a 12 m2 surface. The results showed that the GHE, with a 25

m of length buried at 1 m depth and this covered about 38% of the total cooling requirement of

the tested room.

This study showed that the ground heat exchanger could provide a new way of cooling buildings,

and also showed it that Tunisia has an important geothermal potential which could allow Tunisia

to be a pioneer in the exploitation of geothermal energy for the installation of ground source heat

pump systems (Chiasson, 2016).

While Tunisia is at more northern latitude than Saudi Arabia, it does but share similar climatic

conditions. The feasibility of horizontal borehole heat pumps can be utilized as a cooling

requirement of up to 38% can be realized at shallow depths of 1m and this could be considered

for standalone borehole heat pump applications (Orio, 2013).

Chapter 3: Ground Source Heat Pump Modeling

3.1 Introduction

One of the fundamental tasks in the design of a reliable ground-coupled heat pump system is the

proper sizing of the ground-coupled heat exchanger length i.e. the depth of borehole. Recent

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 15

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.