Evaluating Vertical GSHP Performance in Saudi Arabia's Climate

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/10

|43

|10088

|189

Thesis and Dissertation

AI Summary

This thesis examines the performance of vertical Ground Source Heat Pumps (GSHPs) in the hot and dry climate of Saudi Arabia, aiming to reduce costs, CO2 emissions, and save energy. The study critically reviews existing GSHP technology, presents the concept of GSHP thermal performance, and investigates operational temperatures and heat transfer effects. It analyzes soil heat accumulation in high-temperature regions, estimates total energy savings across a forecast period, and assesses the potential energy savings and peak demand reductions using GHSP systems. The research methodology employs mathematical and numerical analyses, utilizing Ground Loop Design (GLD) programs and TRNSYS simulation software to investigate the impact of weather, soil, and load parameters on GSHP performance, including the vertical separation distance between ground loop pipes under Saudi Arabia's geographical conditions. The study also includes a literature review of energy use history, renewable energy trends, geothermal energy, and the application of ground source heat pumps in similar climates.

The Performance of Vertical Ground Source Heat Pumps (GSHPs) in Hot/Dry Climates (Saudi

Arabia)

By:

Faisal Alshehri

The University of Sheffield

Faculty of Engineering

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Arabia)

By:

Faisal Alshehri

The University of Sheffield

Faculty of Engineering

Department of Mechanical Engineering

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Submission Date

10 Jul. 2018

Table of content

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Research background………………………………………… 1

1.2 Saudi Arabia vision 2030……………………………………. 2

1.3 Thesis aims and objectives……………………………………. 3

1.4 Methodology…………………………………………………. 4

Chapter 2 Literature Review

2.1 History of energy use…………………………………………. 5

2.2 Renewable energy……………………………………………. 6

2.3 Renewable energy trend ……………………………………. 7

2.4 Geothermal energy …………………………………………… 9

2.5 History of the heat pump……………………………………… 10

2.5.1 Heat pump and refrigerators………………………. 11

2.5.2 Heat pump components……………………………. 12

2.5.3 Basic heat pump cycle………………………………. 14

2.6 Ground source heat pump technology…………..……….… 16

2.7 Principle of operation of GSHPs……………………………… 17

2.7.1 Ground loop………………………………………... 17`

2.7.2 Heat pump…………………………………………... 18

2.7.3 Distribution system…………………………………. 18

2.8 Factors affecting GSHP operations…………………………. 19

2.9 Types of geothermal heat pump systems…………………… 20

2.9.1 Closed loop system…………………………………. 20

2.9.1.1 Vertical closed loop………………………. 21

2.9.1.2 Horizontal closed loop……………………. 21

10 Jul. 2018

Table of content

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Research background………………………………………… 1

1.2 Saudi Arabia vision 2030……………………………………. 2

1.3 Thesis aims and objectives……………………………………. 3

1.4 Methodology…………………………………………………. 4

Chapter 2 Literature Review

2.1 History of energy use…………………………………………. 5

2.2 Renewable energy……………………………………………. 6

2.3 Renewable energy trend ……………………………………. 7

2.4 Geothermal energy …………………………………………… 9

2.5 History of the heat pump……………………………………… 10

2.5.1 Heat pump and refrigerators………………………. 11

2.5.2 Heat pump components……………………………. 12

2.5.3 Basic heat pump cycle………………………………. 14

2.6 Ground source heat pump technology…………..……….… 16

2.7 Principle of operation of GSHPs……………………………… 17

2.7.1 Ground loop………………………………………... 17`

2.7.2 Heat pump…………………………………………... 18

2.7.3 Distribution system…………………………………. 18

2.8 Factors affecting GSHP operations…………………………. 19

2.9 Types of geothermal heat pump systems…………………… 20

2.9.1 Closed loop system…………………………………. 20

2.9.1.1 Vertical closed loop………………………. 21

2.9.1.2 Horizontal closed loop……………………. 21

2.9.1.3 Slinky closed loop………………………… 23

2.9.1.4 Closed pond loop…………………………. 23

2.9.2 Open loop systems…………………………………. 23

2.10 Ground source heat pumps in hot and dry climates ………… 25

2.10.1 Saudi Arabia ………………………………………. 25

2.10.2 Erbil, Iraq…………………………………………. 26

2.10.3 Tunisia ……………………………………………. 27

2.10.4 Qatar………………………………………………. 28

2.10.5 Egypt ……………………………………………… 28

2.10.6 Algerian……………………………………………. 29

2.11 Conclusion…………………………………………………... 30

2.9.1.4 Closed pond loop…………………………. 23

2.9.2 Open loop systems…………………………………. 23

2.10 Ground source heat pumps in hot and dry climates ………… 25

2.10.1 Saudi Arabia ………………………………………. 25

2.10.2 Erbil, Iraq…………………………………………. 26

2.10.3 Tunisia ……………………………………………. 27

2.10.4 Qatar………………………………………………. 28

2.10.5 Egypt ……………………………………………… 28

2.10.6 Algerian……………………………………………. 29

2.11 Conclusion…………………………………………………... 30

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Research Background

Saudi Arabia, officially known as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, is a nation-state in the Arab

sovereign and is situated in Western Asia. It has a land mass of approximately 2,150,000 km2

and a population of 32.5 million (General Authority for Statistics, 2018). It has a hot temperature

and becomes very warm during the summer, except for the mountains in the south-western

region. Also, monsoon is very rare in this country and occurs only in a few months (Sultana and

Nasrollahi, 2018). However, it is particularly mild in the winter, with the aforementioned

exception of the south-western region. Most of the climatic features are due to the desert

conditions that are predominately present in the Kingdom.

In terms of energy consumption, energy supplies in Saudi Arabia totally depend on oil and gas

power plants. In Saudi Arabia, energy consumption is extensively subsidized leading to overuse

and misallocation of oil and natural gas resources. The subsidization of energy has given little

incentive for its fast-growing population to save energy consumption in the different economic

activities (Alshehry and Belloumi, 2015). For this reason, domestic energy consumption of oil

has rapidly grown in the past 40-year period and has recently comprised one-fourth of the total

oil production in the country. Over the last five years, Saudi Arabia’s domestic energy

consumption has rapidly grown by 10% annually, with an average of 6% over the last three

decades. The 3.4% population growth per year has had a large impact on the consumption of

domestic oil. This has led to a rapid increase in the demand of electricity in the country. In

addition, it has been estimated that by the year 2025 the electricity generation of Saudi Arabia

might become more than double of the existing demand (Ramli et al., 2015). This is due to the

1

1.1 Research Background

Saudi Arabia, officially known as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, is a nation-state in the Arab

sovereign and is situated in Western Asia. It has a land mass of approximately 2,150,000 km2

and a population of 32.5 million (General Authority for Statistics, 2018). It has a hot temperature

and becomes very warm during the summer, except for the mountains in the south-western

region. Also, monsoon is very rare in this country and occurs only in a few months (Sultana and

Nasrollahi, 2018). However, it is particularly mild in the winter, with the aforementioned

exception of the south-western region. Most of the climatic features are due to the desert

conditions that are predominately present in the Kingdom.

In terms of energy consumption, energy supplies in Saudi Arabia totally depend on oil and gas

power plants. In Saudi Arabia, energy consumption is extensively subsidized leading to overuse

and misallocation of oil and natural gas resources. The subsidization of energy has given little

incentive for its fast-growing population to save energy consumption in the different economic

activities (Alshehry and Belloumi, 2015). For this reason, domestic energy consumption of oil

has rapidly grown in the past 40-year period and has recently comprised one-fourth of the total

oil production in the country. Over the last five years, Saudi Arabia’s domestic energy

consumption has rapidly grown by 10% annually, with an average of 6% over the last three

decades. The 3.4% population growth per year has had a large impact on the consumption of

domestic oil. This has led to a rapid increase in the demand of electricity in the country. In

addition, it has been estimated that by the year 2025 the electricity generation of Saudi Arabia

might become more than double of the existing demand (Ramli et al., 2015). This is due to the

1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

projected growth in the population and the current energy demands. Moreover, Saudi Arabia has

benefitted by the high level of energy consumption per capita, making it one of the predominant

global polluters (in terms of the energy used per capita). This has resulted in 16 metric tons of

carbon dioxide emissions per capita in the year 2009, in comparison to a global average of about

4.7 metric tons. Therefore, the government of Saudi Arabia is attempting to reduce their

greenhouse gas emissions by 130 metric tons (Mt CO2), preferably by 2030.

In addition, research has projected that the peak demand for electricity will reach 70% in 2030

(Al-Yousef and Al-Sheikh, 2012) and 70% of the consumption of the electrical energy per

building will be consumed by ventilation, heating, and air conditioning purposes (HVAC). For

example, in 2010, due to the high temperatures during the summer and an outdoor temperature

of 45 C, buildings consume 65% of the total electricity the and this is 47% higher than the

world average. Hence, special focus should be given to air conditioning systems. This can be

achieved by setting higher efficiency standards, implementing adequate insulation measures as

well as using renewable energy.

1.2 Saudi Arabia Vision 2030

One of the main goals of the Saudi Arabia Vision 2030 is to transform the Kingdom’s oil-

dependent economy to one which is diverse, sustainable, and situated at the crossroads of

international trade. A significant target under the Vision 2030 is to decrease the energy

consumption and greenhouse gas emissions from both the building and industrial sectors. Thus,

the Saudi Arabia Renewable Energy program started with establishment of the King Abdullah

City for Atomic and Renewable Energy (KACARE) which is responsible for the development of

technology which relates to renewable energy, associated research, and the setting of the

2

benefitted by the high level of energy consumption per capita, making it one of the predominant

global polluters (in terms of the energy used per capita). This has resulted in 16 metric tons of

carbon dioxide emissions per capita in the year 2009, in comparison to a global average of about

4.7 metric tons. Therefore, the government of Saudi Arabia is attempting to reduce their

greenhouse gas emissions by 130 metric tons (Mt CO2), preferably by 2030.

In addition, research has projected that the peak demand for electricity will reach 70% in 2030

(Al-Yousef and Al-Sheikh, 2012) and 70% of the consumption of the electrical energy per

building will be consumed by ventilation, heating, and air conditioning purposes (HVAC). For

example, in 2010, due to the high temperatures during the summer and an outdoor temperature

of 45 C, buildings consume 65% of the total electricity the and this is 47% higher than the

world average. Hence, special focus should be given to air conditioning systems. This can be

achieved by setting higher efficiency standards, implementing adequate insulation measures as

well as using renewable energy.

1.2 Saudi Arabia Vision 2030

One of the main goals of the Saudi Arabia Vision 2030 is to transform the Kingdom’s oil-

dependent economy to one which is diverse, sustainable, and situated at the crossroads of

international trade. A significant target under the Vision 2030 is to decrease the energy

consumption and greenhouse gas emissions from both the building and industrial sectors. Thus,

the Saudi Arabia Renewable Energy program started with establishment of the King Abdullah

City for Atomic and Renewable Energy (KACARE) which is responsible for the development of

technology which relates to renewable energy, associated research, and the setting of the

2

policies and legislative frameworks pertaining to Saudi Arabia’s energy consumption (Saleem

and Ali, 2016).

Thus, the Saudi Arabia government intends to impose enthusiastic programs with the

purpose of harnessing renewable energy, for which there are not only great opportunities but also

much room for improvement. Furthermore, they also want to increase their energy mix, which

will include solar thermal, solar PV, waste, wind, and geothermal energy systems. Thus, the

general aims and objectives of this research falls in line with the National Transformation

Program in Saudi Arabia which plans to cut public-sector subsidies, as a part of Vision 2030, by

2020. The Kingdom’s government plans to adjust the subsidies for petroleum products, water,

and electricity over the next five years in order to achieve the efficient use of energy as well as

conservation of natural resources (Surf and Mostafa, 2017).

1.3 Thesis aims and objectives

The main aim of this research is to investigate and test the performance of vertical

Ground Source Heat Pumps (GSHPs) in hot/dry climate which is the predominant climate in

Saudi Arabia in order to reduce its costs and its CO2 emissions along with saving energy. In

order to fulfil this aim, a number of objectives are addressed:

Existing GSHP technology is critically reviewed, and the various aspects of GSHP are

presented.

The concept of GSPH thermal performance is presented, and the various equations

necessary for assessing the performance are described.

The required operational temperature and heat transfer for various effects are

investigated.

3

and Ali, 2016).

Thus, the Saudi Arabia government intends to impose enthusiastic programs with the

purpose of harnessing renewable energy, for which there are not only great opportunities but also

much room for improvement. Furthermore, they also want to increase their energy mix, which

will include solar thermal, solar PV, waste, wind, and geothermal energy systems. Thus, the

general aims and objectives of this research falls in line with the National Transformation

Program in Saudi Arabia which plans to cut public-sector subsidies, as a part of Vision 2030, by

2020. The Kingdom’s government plans to adjust the subsidies for petroleum products, water,

and electricity over the next five years in order to achieve the efficient use of energy as well as

conservation of natural resources (Surf and Mostafa, 2017).

1.3 Thesis aims and objectives

The main aim of this research is to investigate and test the performance of vertical

Ground Source Heat Pumps (GSHPs) in hot/dry climate which is the predominant climate in

Saudi Arabia in order to reduce its costs and its CO2 emissions along with saving energy. In

order to fulfil this aim, a number of objectives are addressed:

Existing GSHP technology is critically reviewed, and the various aspects of GSHP are

presented.

The concept of GSPH thermal performance is presented, and the various equations

necessary for assessing the performance are described.

The required operational temperature and heat transfer for various effects are

investigated.

3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

The problem of soil heat accumulation in Ground Source Heat Pump Systems, in high

temperature regions, will be analyzed.

The total accumulation of energy savings across the forecast period will be estimated.

By using GHSP systems, the potential energy savings and peak demand reductions will

be estimated.

1.4 Methodology

In order to achieve the objectives that have been proposed in this thesis, the research

methodology is based on mathematical and numerical analyses, by employing Ground Loop

Design (GLD) programs and the TRNSYS simulation software, which is used to investigate and

test the performance of the GSHP in hot/dry climates that pertains to Saudi Arabia.

In general, this work aims to investigate the effect of the weather, soil, and load parameters on

the performance of the Ground Source Heat Pump (GSHP) along with the vertical separation

distance between its ground loop pipes in the geographical conditions of Saudi Arabia.

4

temperature regions, will be analyzed.

The total accumulation of energy savings across the forecast period will be estimated.

By using GHSP systems, the potential energy savings and peak demand reductions will

be estimated.

1.4 Methodology

In order to achieve the objectives that have been proposed in this thesis, the research

methodology is based on mathematical and numerical analyses, by employing Ground Loop

Design (GLD) programs and the TRNSYS simulation software, which is used to investigate and

test the performance of the GSHP in hot/dry climates that pertains to Saudi Arabia.

In general, this work aims to investigate the effect of the weather, soil, and load parameters on

the performance of the Ground Source Heat Pump (GSHP) along with the vertical separation

distance between its ground loop pipes in the geographical conditions of Saudi Arabia.

4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1 History of energy use

Energy has not only been regarded as a great resource in the past, but its importance and

increased continuous use has resulted from technological changes. However, the use of energy

dates back to prehistoric periods of humankind. During this age, humans have relied on the

muscular power of animals for their survival (Flint, 2016). Before the advent and development of

the industrial sector, humankind has had limited energy requirements. The sun was once the

main energy source for heat, shelter, warmth, and food (Mackay, 2015). Hence, a switch to a

new type of fuel was necessary. This led to the use of coal, oil, and other natural gases as the

main source of fuel. According to the International Correspondence Schools (2012), the 17th

century witnessed the use of steam engines and coal by humans, along with the discovery of

natural gas, oil, and electricity (NaturalGas.org,2018). In 1880, the steam engine was attached to

an electrical generator and powered by coal (International Correspondence Schools, 2012). Also

the fast flow of water was used for creating light energy and thereafter, a hydro-plant was built

by Edison with the assistance of Henry Ford (Strohl, 2010). By the end of the 18th century,

5

2.1 History of energy use

Energy has not only been regarded as a great resource in the past, but its importance and

increased continuous use has resulted from technological changes. However, the use of energy

dates back to prehistoric periods of humankind. During this age, humans have relied on the

muscular power of animals for their survival (Flint, 2016). Before the advent and development of

the industrial sector, humankind has had limited energy requirements. The sun was once the

main energy source for heat, shelter, warmth, and food (Mackay, 2015). Hence, a switch to a

new type of fuel was necessary. This led to the use of coal, oil, and other natural gases as the

main source of fuel. According to the International Correspondence Schools (2012), the 17th

century witnessed the use of steam engines and coal by humans, along with the discovery of

natural gas, oil, and electricity (NaturalGas.org,2018). In 1880, the steam engine was attached to

an electrical generator and powered by coal (International Correspondence Schools, 2012). Also

the fast flow of water was used for creating light energy and thereafter, a hydro-plant was built

by Edison with the assistance of Henry Ford (Strohl, 2010). By the end of the 18th century,

5

petroleum, along with gasoline, was being used as fuel to fire the combustion engines which

were slowly being developed (Boyle & Open University, 2012).

Because of the rapid development and invention of several energy sources and technologies, the

17th and 18th centuries have often been considered as the starting point of the Industrial

Revolution (Pierce, 2005). The world’s human population and their energy usage saw a

significant growth during this period. To achieve the increasing energy requirements worldwide,

the world’s energy production increased rapidly. This energy demand was supported by the

larger power plants as well as hydro plants. A large variety of energy sources were being sought

to generate more power and electricity was made available even in rural regions (Hinrichs &

Kleinbach, 2013).

New technologies have been developed in the modern age. Due to the extensive use of natural

gas, petroleum, and other fossil fuels that have been used to support the high energy demand,

there was a great decline in the availability of these non-renewable fossil fuels. This called for

the invention of new technologies and alternative sources of energy in order to generate the

requisite amount of power. In the 19th century, nuclear power started to be used (Cumo, 2017). In

the 20th century can be regarded as the modern era with regard to energy usage, consumption,

and technological developments. The development and advancement in the field of computers,

IT sectors, space exploration, etc. have provided ample support towards exploring new energy

sources in the modern era. Along with fossil fuels and petroleum, renewable energy sources have

also been used to produce the required amount of energy (Shere, 2013). At present, the use of

renewable energy sources has been large-scale. Nowadays, many countries are quite dependent

on solar and wind energy while eschewing their dependence on conventional sources of energy

(Boyle & Open University, 2012). Along with harnessing wind and solar energy, developed

6

were slowly being developed (Boyle & Open University, 2012).

Because of the rapid development and invention of several energy sources and technologies, the

17th and 18th centuries have often been considered as the starting point of the Industrial

Revolution (Pierce, 2005). The world’s human population and their energy usage saw a

significant growth during this period. To achieve the increasing energy requirements worldwide,

the world’s energy production increased rapidly. This energy demand was supported by the

larger power plants as well as hydro plants. A large variety of energy sources were being sought

to generate more power and electricity was made available even in rural regions (Hinrichs &

Kleinbach, 2013).

New technologies have been developed in the modern age. Due to the extensive use of natural

gas, petroleum, and other fossil fuels that have been used to support the high energy demand,

there was a great decline in the availability of these non-renewable fossil fuels. This called for

the invention of new technologies and alternative sources of energy in order to generate the

requisite amount of power. In the 19th century, nuclear power started to be used (Cumo, 2017). In

the 20th century can be regarded as the modern era with regard to energy usage, consumption,

and technological developments. The development and advancement in the field of computers,

IT sectors, space exploration, etc. have provided ample support towards exploring new energy

sources in the modern era. Along with fossil fuels and petroleum, renewable energy sources have

also been used to produce the required amount of energy (Shere, 2013). At present, the use of

renewable energy sources has been large-scale. Nowadays, many countries are quite dependent

on solar and wind energy while eschewing their dependence on conventional sources of energy

(Boyle & Open University, 2012). Along with harnessing wind and solar energy, developed

6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

countries have increased the funding of research activities aimed at identifying and harnessing

different sources of energy including biomass, hydraulic, solar, wind, geothermal, wave, tidal,

biogas, ocean, fuel cells, and hydrogen, in order to improve the ways of harnessing energy from

sources and support a clean environment with no gaseous emissions (Sierra Forest Legacy,

2012).

2.2 Renewable energy

In 1973, the oil crisis in many countries made them think about alternatives to oil and they

started looking for sources of renewable energy. Actually, there are numerous different sources

and forms of energy. Broadly, there are two sources: renewable and non-renewable energy

(Bartoletto, 2012). However, there is a slight difference between the two sources of energy;

renewable energy is obtained from sources at a less, or equal, rate in which the source

replenishes itself. In other words, it is derived from sources which will never be completely

depleted and will continue to provide energy for many years to come. Examples of renewable

energy include, but are not limited to, solar, wind, geothermal, biomass, ocean waves, and

hydraulic energy. On the other hand, non-renewable energy sources are obtained at a rate which

exceeds the rate at which the sources replenish themselves, e.g. uranium (which is used for

nuclear fusion) and fossil fuels (Harold et al., 1963; Wang & Chen, 2016).

2.3 Renewable Energy Trend

Over the last few decades, excessive use of fossil fuels has resulted in an increase in

carbon dioxide emissions. Due to the massive use of oil and the high demand for energy,

developed and developing countries are seeking to apply advanced technological innovations

that meet the requirements of safe and efficient energy and do not adversely affect the climate

7

different sources of energy including biomass, hydraulic, solar, wind, geothermal, wave, tidal,

biogas, ocean, fuel cells, and hydrogen, in order to improve the ways of harnessing energy from

sources and support a clean environment with no gaseous emissions (Sierra Forest Legacy,

2012).

2.2 Renewable energy

In 1973, the oil crisis in many countries made them think about alternatives to oil and they

started looking for sources of renewable energy. Actually, there are numerous different sources

and forms of energy. Broadly, there are two sources: renewable and non-renewable energy

(Bartoletto, 2012). However, there is a slight difference between the two sources of energy;

renewable energy is obtained from sources at a less, or equal, rate in which the source

replenishes itself. In other words, it is derived from sources which will never be completely

depleted and will continue to provide energy for many years to come. Examples of renewable

energy include, but are not limited to, solar, wind, geothermal, biomass, ocean waves, and

hydraulic energy. On the other hand, non-renewable energy sources are obtained at a rate which

exceeds the rate at which the sources replenish themselves, e.g. uranium (which is used for

nuclear fusion) and fossil fuels (Harold et al., 1963; Wang & Chen, 2016).

2.3 Renewable Energy Trend

Over the last few decades, excessive use of fossil fuels has resulted in an increase in

carbon dioxide emissions. Due to the massive use of oil and the high demand for energy,

developed and developing countries are seeking to apply advanced technological innovations

that meet the requirements of safe and efficient energy and do not adversely affect the climate

7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

(Bartoletto, 2012; Malanima, 2006). Although technological innovation is a key driver of energy

transition, there are many other related factors which include, but are not limited to, politics,

culture, economy, and geography. These considerations are important when selecting distinct

technologies which are to be adopted in the course of harnessing energy sources as well as

providing other energy-related services worldwide (Cottrell, 2009). Also, developed countries

have increased the funds allotted towards research activities regarding different sources of

renewable energy, in order to support a clean environment with no emissions (Sierra Forest

Legacy2012)

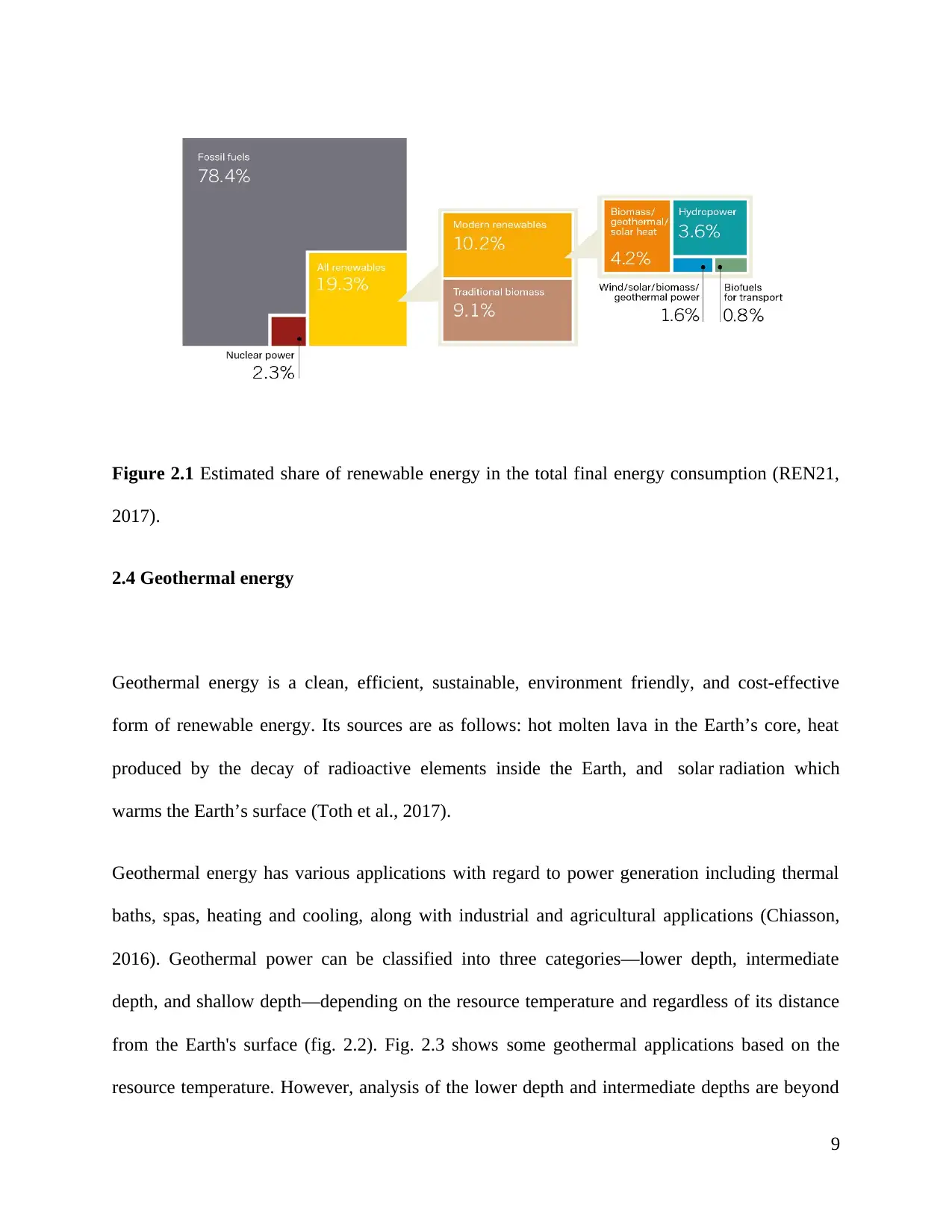

According to the renewable global status report (REN21, 2017) the increase in the

demand of renewable energy has taken place in several directions and can be summarized

as follows:

(i) .Growth: In 2015, the use of renewable energy amounted to about 19.3% of the global

energy consumption.

(ii) . Energy Policy: 176 countries had renewable energy targets, 126 countries had power

policies, 68 countries had transport policies, and 21 countries had heating and cooling

policies.

(iii) .Job Opportunity: In 2016, the renewable energy industry employed around 9.8

million to their workforce, which was 1.1% higher than their employment percentile

in 2015.

(iv). Investment: The market share of renewable energy was 241.6 billion USD in 2016.

For the past five years, the investment in the sector of renewable power energy has

been almost double of what has been invested in harnessing the energy based on

fossil fuels.

8

transition, there are many other related factors which include, but are not limited to, politics,

culture, economy, and geography. These considerations are important when selecting distinct

technologies which are to be adopted in the course of harnessing energy sources as well as

providing other energy-related services worldwide (Cottrell, 2009). Also, developed countries

have increased the funds allotted towards research activities regarding different sources of

renewable energy, in order to support a clean environment with no emissions (Sierra Forest

Legacy2012)

According to the renewable global status report (REN21, 2017) the increase in the

demand of renewable energy has taken place in several directions and can be summarized

as follows:

(i) .Growth: In 2015, the use of renewable energy amounted to about 19.3% of the global

energy consumption.

(ii) . Energy Policy: 176 countries had renewable energy targets, 126 countries had power

policies, 68 countries had transport policies, and 21 countries had heating and cooling

policies.

(iii) .Job Opportunity: In 2016, the renewable energy industry employed around 9.8

million to their workforce, which was 1.1% higher than their employment percentile

in 2015.

(iv). Investment: The market share of renewable energy was 241.6 billion USD in 2016.

For the past five years, the investment in the sector of renewable power energy has

been almost double of what has been invested in harnessing the energy based on

fossil fuels.

8

Figure 2.1 Estimated share of renewable energy in the total final energy consumption (REN21,

2017).

2.4 Geothermal energy

Geothermal energy is a clean, efficient, sustainable, environment friendly, and cost-effective

form of renewable energy. Its sources are as follows: hot molten lava in the Earth’s core, heat

produced by the decay of radioactive elements inside the Earth, and solar radiation which

warms the Earth’s surface (Toth et al., 2017).

Geothermal energy has various applications with regard to power generation including thermal

baths, spas, heating and cooling, along with industrial and agricultural applications (Chiasson,

2016). Geothermal power can be classified into three categories—lower depth, intermediate

depth, and shallow depth—depending on the resource temperature and regardless of its distance

from the Earth's surface (fig. 2.2). Fig. 2.3 shows some geothermal applications based on the

resource temperature. However, analysis of the lower depth and intermediate depths are beyond

9

2017).

2.4 Geothermal energy

Geothermal energy is a clean, efficient, sustainable, environment friendly, and cost-effective

form of renewable energy. Its sources are as follows: hot molten lava in the Earth’s core, heat

produced by the decay of radioactive elements inside the Earth, and solar radiation which

warms the Earth’s surface (Toth et al., 2017).

Geothermal energy has various applications with regard to power generation including thermal

baths, spas, heating and cooling, along with industrial and agricultural applications (Chiasson,

2016). Geothermal power can be classified into three categories—lower depth, intermediate

depth, and shallow depth—depending on the resource temperature and regardless of its distance

from the Earth's surface (fig. 2.2). Fig. 2.3 shows some geothermal applications based on the

resource temperature. However, analysis of the lower depth and intermediate depths are beyond

9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 43

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.