GVC Start-up Selection: A Decision-Making Model Using Fuzzy TOPSIS

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/18

|23

|13976

|84

AI Summary

This research paper introduces a decision-making model employing the intuitionistic fuzzy Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method to enhance the selection of start-up businesses within a government venture capital (GVC) scheme. Addressing the prevalent issue of underperformance in GVC-funded start-ups due to factors like lack of transparency and biases, the proposed model aims to increase fairness and incorporate uncertainties in the selection criteria using fuzzy set theory. The methodology involves establishing relevant criteria, analyzing them using TOPSIS in an intuitionistic fuzzy environment, and aggregating decision-maker ratings with the intuitionistic fuzzy weighted averaging operator. By providing a numerical example, the paper demonstrates the practical application of the model in a competitive GVC setting, offering a valuable framework for improving the selection process and ensuring the support of start-ups with high potential for success.

Management Decision

A decision making model for selecting start-up businesses in a government

venture capital scheme

Eric Afful-Dadzie, Anthony Afful-Dadzie,

Article information:

To cite this document:

Eric Afful-Dadzie, Anthony Afful-Dadzie, (2016) "A decision making model for selecting start-up

businesses in a government venture capital scheme", Management Decision, Vol. 54 Issue: 3,

pp.714-734, https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-06-2015-0226

Permanent link to this document:

https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-06-2015-0226

Downloaded on: 30 November 2018, At: 06:06 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 76 other documents.

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 1306 times since 2016*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2012),"Cases of start-up financing: An analysis of new venture capitalisation structures and

patterns", International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, Vol. 18 Iss 1 pp. 28-47

<a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551211201367">https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551211201367</

a>

(2017),"Supporting start-up business model design through system dynamics modelling",

Management Decision, Vol. 55 Iss 1 pp. 57-80 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/

MD-06-2016-0395">https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-06-2016-0395</a>

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald-

srm:534301 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emera

for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submis

guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more informa

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The compa

manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes

well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and

services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the

Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for

digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

A decision making model for selecting start-up businesses in a government

venture capital scheme

Eric Afful-Dadzie, Anthony Afful-Dadzie,

Article information:

To cite this document:

Eric Afful-Dadzie, Anthony Afful-Dadzie, (2016) "A decision making model for selecting start-up

businesses in a government venture capital scheme", Management Decision, Vol. 54 Issue: 3,

pp.714-734, https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-06-2015-0226

Permanent link to this document:

https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-06-2015-0226

Downloaded on: 30 November 2018, At: 06:06 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 76 other documents.

To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 1306 times since 2016*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2012),"Cases of start-up financing: An analysis of new venture capitalisation structures and

patterns", International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, Vol. 18 Iss 1 pp. 28-47

<a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551211201367">https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551211201367</

a>

(2017),"Supporting start-up business model design through system dynamics modelling",

Management Decision, Vol. 55 Iss 1 pp. 57-80 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/

MD-06-2016-0395">https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-06-2016-0395</a>

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by emerald-

srm:534301 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emera

for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submis

guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more informa

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The compa

manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes

well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and

services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the

Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for

digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A decision making model for

selecting start-up businesses

in a government venture

capital scheme

Eric Afful-Dadzie

Faculty of Applied Informatics,

Tomas Bata University in Zlin, Zlin, Czech Republic, and

Anthony Afful-Dadzie

Business School, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana

Abstract

Purpose – The purpose ofthis paperis to propose an intuitionistic fuzzy technique fororder

preference by similarity to idealsolution (TOPSIS)multi-criteria decision making method for the

selection of start-up businesses in a government venture capital(GVC)scheme.Most GVC funded

start-ups fail or underperform compared to those funded by private VCs due to a number of re

including lack of transparency and unfairness in the selection process.By its design,the proposed

method is able to increase transparency and reduce the influence of bias in GVC start-up selec

processes. The proposed method also models uncertainty in the selection criteria using fuzzy s

that mirrors the natural human decision-making process.

Design/methodology/approach – The proposed method first presents a set of criteria relevant

the selection of early stage but high-potential start-ups in a GVC financing scheme.These criteria are

then analyzed using the TOPSIS method in an intuitionistic fuzzy environment.The intuitionistic

fuzzy weighted averaging Operator is used to aggregate ratings of decision makers.A numerical

example of how the proposed method could be used in GVC start-up candidate selection in a h

competitive GVC scheme is provided.

Findings – The methodology adopted increases fairness and transparency in the selection of st

businesses for fund supportin a government-run VC scheme.The criteria setproposed is ideal

for selecting start-up businessesin a governmentcontrolled VC scheme.The decision-making

framework demonstrates how uncertainty in the selection criteria are efficiently modelled with

TOPSIS method.

Practical implications – As GVC schemes increase around the world,and concerns about failure

and underperformance ofGVC funded start-ups increase,the proposed method could help bring

formalism and ensure the selection of start-ups with high potential for success.

Originality/value – The framework designsrelevantsets of criteria fora selection problem,

demonstrates the use of extended TOPSIS method in intuitionistic fuzzy sets and apply the pro

method in an area that has not been considered before. Additionally, it demonstrates how intu

fuzzy TOPSIS could be carried out in a real decision-making application setting.

Keywords Decision making,Start-up businesses,Government venture capital (GVC),

Intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS (IFS)

Paper type Research paper

Management Decision

Vol.54 No.3,2016

pp.714-734

© Emerald Group Publishing Limited

0025-1747

DOI 10.1108/MD-06-2015-0226

Received 10 June 2015

Revised 7 October 2015

5 January 2016

Accepted 11 January 2016

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at:

www.emeraldinsight.com/0025-1747.htm

This work was supported by Grant Agency of the Czech Republic – GACR P103/15/0670

further by financial support of research project NPU I No.MSMT-7778/2014 by the Ministry of

Education of the Czech Republic and also by the European Regional Development Fund

the Project CEBIA-Tech No. CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0089. Further, this work was supported b

Grant Agency of Tomas Bata University under the project No.IGA/FAI/2015/054.

714

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

selecting start-up businesses

in a government venture

capital scheme

Eric Afful-Dadzie

Faculty of Applied Informatics,

Tomas Bata University in Zlin, Zlin, Czech Republic, and

Anthony Afful-Dadzie

Business School, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana

Abstract

Purpose – The purpose ofthis paperis to propose an intuitionistic fuzzy technique fororder

preference by similarity to idealsolution (TOPSIS)multi-criteria decision making method for the

selection of start-up businesses in a government venture capital(GVC)scheme.Most GVC funded

start-ups fail or underperform compared to those funded by private VCs due to a number of re

including lack of transparency and unfairness in the selection process.By its design,the proposed

method is able to increase transparency and reduce the influence of bias in GVC start-up selec

processes. The proposed method also models uncertainty in the selection criteria using fuzzy s

that mirrors the natural human decision-making process.

Design/methodology/approach – The proposed method first presents a set of criteria relevant

the selection of early stage but high-potential start-ups in a GVC financing scheme.These criteria are

then analyzed using the TOPSIS method in an intuitionistic fuzzy environment.The intuitionistic

fuzzy weighted averaging Operator is used to aggregate ratings of decision makers.A numerical

example of how the proposed method could be used in GVC start-up candidate selection in a h

competitive GVC scheme is provided.

Findings – The methodology adopted increases fairness and transparency in the selection of st

businesses for fund supportin a government-run VC scheme.The criteria setproposed is ideal

for selecting start-up businessesin a governmentcontrolled VC scheme.The decision-making

framework demonstrates how uncertainty in the selection criteria are efficiently modelled with

TOPSIS method.

Practical implications – As GVC schemes increase around the world,and concerns about failure

and underperformance ofGVC funded start-ups increase,the proposed method could help bring

formalism and ensure the selection of start-ups with high potential for success.

Originality/value – The framework designsrelevantsets of criteria fora selection problem,

demonstrates the use of extended TOPSIS method in intuitionistic fuzzy sets and apply the pro

method in an area that has not been considered before. Additionally, it demonstrates how intu

fuzzy TOPSIS could be carried out in a real decision-making application setting.

Keywords Decision making,Start-up businesses,Government venture capital (GVC),

Intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS (IFS)

Paper type Research paper

Management Decision

Vol.54 No.3,2016

pp.714-734

© Emerald Group Publishing Limited

0025-1747

DOI 10.1108/MD-06-2015-0226

Received 10 June 2015

Revised 7 October 2015

5 January 2016

Accepted 11 January 2016

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at:

www.emeraldinsight.com/0025-1747.htm

This work was supported by Grant Agency of the Czech Republic – GACR P103/15/0670

further by financial support of research project NPU I No.MSMT-7778/2014 by the Ministry of

Education of the Czech Republic and also by the European Regional Development Fund

the Project CEBIA-Tech No. CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0089. Further, this work was supported b

Grant Agency of Tomas Bata University under the project No.IGA/FAI/2015/054.

714

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

1. Introduction

Venture capital (VC) investment is proving to be the mainstay in the lives of start-up

businesses around the world,especially those in the “high-tech” industry.Evidence

from the USA,Europe,China,India,Canada and Israel,points to a gradualglobal

acceptance of VC support for early stage but high-potential businesses. In 2013,global

VC investment was estimated at US$48.5 billion (Ernst & Young,2014).According to

Bertoniet al. (2011),Gompersand Lerner(2004),Chemmanuret al. (2011)and

Alperovych et al. (2015),there is enough evidence to show that the commercial success

rates of start-up businesses that receive support from VC far outweigh those that do

not receive any such supports. However, in recent times, due to very strict demands on

start-up businesses from Private Venture Capitalists (PVCs) and the apparent lack of

opportunities atsecuring financialsupportthrough traditionalinvestmentsources,

many governments around the world have joined the fray as far as VC investment is

concerned (Bertoni and Tykvová, 2015; Nkusu, 2011; Colombo et al., 2014). For instance

in Europe,a total of 40 per cent of all VC investments in 2013 were reported to have

come from their governments.Similarly in the USA,the federalgovernment’s Small

Business Innovation Research programme is the single largest investor of early stage

innovations(Ernst & Young, 2014;Audretsch,2003;Lerner,2000).Government

venture capital(GVC)is also quite popular in Brazil,Russia,India,China and South

Africa and in developing countries where private VC funding are hard to come by

compared to what exist in the USA and Europe (Ernst & Young,2014).In spite of the

growing interests in GVCs, many studies report of a worrying trend of GVC supported

early stage businesses underperforming against their counterparts that obtain funding

from PVCs (Brander etal.,2008;Luukkonen etal.,2013;Grilli and Murtinu,2014;

Alperovych etal.,2015;Bertoniand Tykvová,2012).A number ofreasons for the

underperformance has been offered.Some authors assert that the selection process

in GVC schemes lack the rigorousness demanded in PVC schemes (Christofidis and

Debande,2001;Leleux and Surlemont,2003).Many also cite the undue influence of

political and pressure groups (usually aligned with governments) as a major reason for

the poor performance of GVC funded start-up businesses (Knoesen, 2009; Nattrass and

Seekings,2001;Iheduru,2004).Others also argue thatsuch underperformance is

exacerbated by the lack ofmodels thatexplicitly feature importantaspects ofthe

selection process such as uncertainties in some of the evaluation criteria (Zacharakis

and Shepherd,2001;Muzyka etal.,1996;Zacharakis and Meyer,2000).This paper

addresses the concerns of such authors and proposes a model for the evaluation and

selection of start-up businesses in a GVC scheme that incorporates uncertainties in the

selection criteria.To do this,the paper first contrasts GVCs with PVCs for a better

understanding of their differences and subsequently,the reasons why GVC funded

start-ups usually underperform against PVC funded start-ups.

1.1 PVCs vs GVCs

The main objective of a PVC firm is to generate enough returns for its investors and

maximize their value typically above the level of the public equity markets (Mulcahy,

2014).The fearof losing investors,guide PVC firms to avoid favouritism in the

selection ofstart-up businesses.In view of this,a candidate start-up technology

business must have high potentialto succeed and demonstrate the ability to make

significant profits over a period of time.With this in mind,PVCs usually look out for

early entrepreneurs that can deliver impressive growth within specific time period,

typically not more than six years (Da Rin et al.,2011).

715

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

Venture capital (VC) investment is proving to be the mainstay in the lives of start-up

businesses around the world,especially those in the “high-tech” industry.Evidence

from the USA,Europe,China,India,Canada and Israel,points to a gradualglobal

acceptance of VC support for early stage but high-potential businesses. In 2013,global

VC investment was estimated at US$48.5 billion (Ernst & Young,2014).According to

Bertoniet al. (2011),Gompersand Lerner(2004),Chemmanuret al. (2011)and

Alperovych et al. (2015),there is enough evidence to show that the commercial success

rates of start-up businesses that receive support from VC far outweigh those that do

not receive any such supports. However, in recent times, due to very strict demands on

start-up businesses from Private Venture Capitalists (PVCs) and the apparent lack of

opportunities atsecuring financialsupportthrough traditionalinvestmentsources,

many governments around the world have joined the fray as far as VC investment is

concerned (Bertoni and Tykvová, 2015; Nkusu, 2011; Colombo et al., 2014). For instance

in Europe,a total of 40 per cent of all VC investments in 2013 were reported to have

come from their governments.Similarly in the USA,the federalgovernment’s Small

Business Innovation Research programme is the single largest investor of early stage

innovations(Ernst & Young, 2014;Audretsch,2003;Lerner,2000).Government

venture capital(GVC)is also quite popular in Brazil,Russia,India,China and South

Africa and in developing countries where private VC funding are hard to come by

compared to what exist in the USA and Europe (Ernst & Young,2014).In spite of the

growing interests in GVCs, many studies report of a worrying trend of GVC supported

early stage businesses underperforming against their counterparts that obtain funding

from PVCs (Brander etal.,2008;Luukkonen etal.,2013;Grilli and Murtinu,2014;

Alperovych etal.,2015;Bertoniand Tykvová,2012).A number ofreasons for the

underperformance has been offered.Some authors assert that the selection process

in GVC schemes lack the rigorousness demanded in PVC schemes (Christofidis and

Debande,2001;Leleux and Surlemont,2003).Many also cite the undue influence of

political and pressure groups (usually aligned with governments) as a major reason for

the poor performance of GVC funded start-up businesses (Knoesen, 2009; Nattrass and

Seekings,2001;Iheduru,2004).Others also argue thatsuch underperformance is

exacerbated by the lack ofmodels thatexplicitly feature importantaspects ofthe

selection process such as uncertainties in some of the evaluation criteria (Zacharakis

and Shepherd,2001;Muzyka etal.,1996;Zacharakis and Meyer,2000).This paper

addresses the concerns of such authors and proposes a model for the evaluation and

selection of start-up businesses in a GVC scheme that incorporates uncertainties in the

selection criteria.To do this,the paper first contrasts GVCs with PVCs for a better

understanding of their differences and subsequently,the reasons why GVC funded

start-ups usually underperform against PVC funded start-ups.

1.1 PVCs vs GVCs

The main objective of a PVC firm is to generate enough returns for its investors and

maximize their value typically above the level of the public equity markets (Mulcahy,

2014).The fearof losing investors,guide PVC firms to avoid favouritism in the

selection ofstart-up businesses.In view of this,a candidate start-up technology

business must have high potentialto succeed and demonstrate the ability to make

significant profits over a period of time.With this in mind,PVCs usually look out for

early entrepreneurs that can deliver impressive growth within specific time period,

typically not more than six years (Da Rin et al.,2011).

715

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

To reduce the chances of failure, PVC funded start-up businesses typically un

lengthy and demanding screening processes (Landstrîm, 2007; Lerner, 2002). P

place greater emphasis on the experience of the management team and often

for a representation on the management board of the start-up firm so as to be

monitor and prevent wasteful spending that may derail the development and g

the business (Chemmanuret al., 2011;Lerner,2002).PVCs are prevalentin the

information systemssector,and also in some specifichealth sectorssuch as

the pharmaceutical industry (Lerner,2002).

GVCs on the other hand,mostly operate in sectors that normally lack VC financing

such as education,environment and health sectors (Lerner,2002).They usually fund

start-ups that possess promising technology beneficialto society but which lack the

necessary funding to bring the technology to fruition. In this regard, technologi

potential to spawn positive externalities,such as those with prospects of stimulating

growth in other sectors,have higher chances of attaining GVC funding (Lerner,2002).

Since the main objective of a GVC investment is welfare maximization to the st

GVCs demand rates of returns tend to be far lower than that of a typical PVC (G

1992). As a result, a GVC investment might not yield direct monetary profit to t

and could stillbe considered a success.GVC investments are usually subjectto

statutory terms and conditions in respect to the type of investments and the m

which the investment is carried out (Landstrîm, 2007). Most often however, suc

and conditions are less stricter than those of PVCs.

Using data from the VC industry in Belgium,Alperovych et al.(2015)finds that

PVC-backed firms are more efficient than GVC-backed firms.More tellingly,they find

that GVC-backed firms are less efficientthan non-VC-backed firms.PVC-backed

companies also mostly meet exiting deadlines and conditionalities than GVC-ba

companies (Cumming etal.,2014;Chemmanur etal.,2011;Luukkonen etal.,2013;

Bertoniand Tykvová,2012;Brander et al.,2008).Grilli and Murtinu (2014)show in

their study that PVC funding leads to increase growth in new start-ups than GV

funding. Lerner (2002)also finds that a prevalentcharacteristicsamong

underachieving start-up companies is that most are funded through research g

from government agencies.

A number of factors could account for the gap in performance. Some of these

capitalrecovery rates and undefined exit paths for candidate start-up businesse

GVC schemes (Biekpe,2004).In addition,unlike PVCs,GVCs usually do not require a

position on the management team of the start-up company. The lack of involve

GVCs in the management team (and therefore lack of proper monitoring) of the

company is believed by many as one of the main reasons why GVC funded star

underperform comparedto PVC funded start-ups(Chemmanuret al., 2011;

Cumming,2007).Without proper monitoring,it is easy for a start-up firm to engage

in over spending or lose focus and venture into business programmes unrelated

originalbusiness idea.Furthermore,Christofidis and Debande (2001)observed that

most GVCs are run by inexperienced civil servants who are less motivated unlik

counterpartfund managersat PVCs. Leleux and Surlemont(2003);Meyerand

Mathonet (2011)explain that the seeming lack of motivation of government staff a

GVCs,is because they do not directly share in returns that accrue to the GVCs t

manage.There are also the criticisms of an apparent lack of robust selection crite

(Bertoni et al., 2011), lack of due diligence in the selection process (Baeyens et

poor programmedesign and implementation challenges(Lerner,2009)in GVCs.

The award ofGVC fundsto start-ups,unlikein PVCs, is proneto biasesand

716

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

lengthy and demanding screening processes (Landstrîm, 2007; Lerner, 2002). P

place greater emphasis on the experience of the management team and often

for a representation on the management board of the start-up firm so as to be

monitor and prevent wasteful spending that may derail the development and g

the business (Chemmanuret al., 2011;Lerner,2002).PVCs are prevalentin the

information systemssector,and also in some specifichealth sectorssuch as

the pharmaceutical industry (Lerner,2002).

GVCs on the other hand,mostly operate in sectors that normally lack VC financing

such as education,environment and health sectors (Lerner,2002).They usually fund

start-ups that possess promising technology beneficialto society but which lack the

necessary funding to bring the technology to fruition. In this regard, technologi

potential to spawn positive externalities,such as those with prospects of stimulating

growth in other sectors,have higher chances of attaining GVC funding (Lerner,2002).

Since the main objective of a GVC investment is welfare maximization to the st

GVCs demand rates of returns tend to be far lower than that of a typical PVC (G

1992). As a result, a GVC investment might not yield direct monetary profit to t

and could stillbe considered a success.GVC investments are usually subjectto

statutory terms and conditions in respect to the type of investments and the m

which the investment is carried out (Landstrîm, 2007). Most often however, suc

and conditions are less stricter than those of PVCs.

Using data from the VC industry in Belgium,Alperovych et al.(2015)finds that

PVC-backed firms are more efficient than GVC-backed firms.More tellingly,they find

that GVC-backed firms are less efficientthan non-VC-backed firms.PVC-backed

companies also mostly meet exiting deadlines and conditionalities than GVC-ba

companies (Cumming etal.,2014;Chemmanur etal.,2011;Luukkonen etal.,2013;

Bertoniand Tykvová,2012;Brander et al.,2008).Grilli and Murtinu (2014)show in

their study that PVC funding leads to increase growth in new start-ups than GV

funding. Lerner (2002)also finds that a prevalentcharacteristicsamong

underachieving start-up companies is that most are funded through research g

from government agencies.

A number of factors could account for the gap in performance. Some of these

capitalrecovery rates and undefined exit paths for candidate start-up businesse

GVC schemes (Biekpe,2004).In addition,unlike PVCs,GVCs usually do not require a

position on the management team of the start-up company. The lack of involve

GVCs in the management team (and therefore lack of proper monitoring) of the

company is believed by many as one of the main reasons why GVC funded star

underperform comparedto PVC funded start-ups(Chemmanuret al., 2011;

Cumming,2007).Without proper monitoring,it is easy for a start-up firm to engage

in over spending or lose focus and venture into business programmes unrelated

originalbusiness idea.Furthermore,Christofidis and Debande (2001)observed that

most GVCs are run by inexperienced civil servants who are less motivated unlik

counterpartfund managersat PVCs. Leleux and Surlemont(2003);Meyerand

Mathonet (2011)explain that the seeming lack of motivation of government staff a

GVCs,is because they do not directly share in returns that accrue to the GVCs t

manage.There are also the criticisms of an apparent lack of robust selection crite

(Bertoni et al., 2011), lack of due diligence in the selection process (Baeyens et

poor programmedesign and implementation challenges(Lerner,2009)in GVCs.

The award ofGVC fundsto start-ups,unlikein PVCs, is proneto biasesand

716

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

favouritism (which consequently could lead to failure) since selection could be influenced

by powerfulinterest groups aligned to governments and politicians who may seek to

direct the award of GVC funding in a manner that benefits themselves (Cumming, 2007;

Lerner,2002) and their constituents.This is especially the case in developing countries

where selection of candidates for such capital financing schemes are sometimes clouded

by political,tribaland socialaffiliations (Nkusu,2011).According to Pina-Stranger

and Lazega (2011) and Sorenson and Rogan (2014),these challenges could be avoided

or their impact mitigated through a transparent decision making process (devoid of

personal ties and affiliations) for selecting start-up businesses.

These observations have led to a renewed interests in research aimed at improving the

performance of GVCs (Munari andToschi, 2015). One of such interest is a mechanism for a

transparent and efficient decision making process for determining the commercial viabilit

and the eventual selection of a technology start-up business in a government-run VC.

Any such decision-making mechanism must be able to address the problems listed

above including that of bias and favouritism.More importantly,the mechanism must

place greater importance on the need for effective management team for the success of

the start-up.

1.2 Research gap

Some non-fuzzy decision-making models for evaluating and selecting start-ups in VC

financing schemes have been proposed. Woike et al. (2015) used computer simulation to

study the impact of different strategies on the financial performance of VCs.Riquelme

and Rickards (1992)proposed a self-explicated,hybrid conjointmodelto aid the

selection of start-ups for financing in a VC scheme.These non-fuzzy methods rely on

historical data of past beneficiaries to arrive at a decision.This approach may not all

the time be appropriate for assessing and selecting early stage entrepreneurs that have

little or no past data and might lead to sub-optimaldecisions.Since future values of

data needed for evaluation are uncertain at the time of selection, fuzzy models that have

the ability to explicitly consider uncertainty in the models might be appropriate.

The main objective ofthis paper is therefore to propose a fuzzy multi-criteria

decision making (MCDM) model for the selection of start-ups in GVCs that addresses

the obvious uncertainty problems in such decision problems.It is also hoped that the

proposed approach would help generate interest regarding research in decision models

for VC selection problems.

In our search of literature,only the works of Zhang (2012),and Aouni et al.(2014),

attemptto use fuzzy theory for selecting start-up businesses in a VC.Aounietal.

(2014) used a fuzzy goal programming approach to model uncertainty.However,such

models cannotaccommodate qualitative factors such as leadership experience and

productquality.Zhang (2012),considers fuzziness butonly in the weights ofthe

evaluators and not in the values for the competing start-up candidates.Zhang (2012)

also does not explicitly modeluncertainty but instead attempts to overcome it using

entropy techniqueto determinethe weights.The modelby Zhang (2012)is a

combination ofan optimization and a multi-attribute modelthatseeks to selecta

candidatebased on maximizing risk-adjusted returns.In contrast,our proposed

approach uses a multi-attribute model to generate a composite index that however takes

qualitative factors as wellas a “more is better” and a “less is better” criterion into

account. By considering uncertainties directly in the values for assessment, the proposed

intuitionisticfuzzy techniquefor orderpreferenceby similarity to idealsolution

(TOPSIS) framework is thus more efficient at modelling the natural thought processes of

717

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

by powerfulinterest groups aligned to governments and politicians who may seek to

direct the award of GVC funding in a manner that benefits themselves (Cumming, 2007;

Lerner,2002) and their constituents.This is especially the case in developing countries

where selection of candidates for such capital financing schemes are sometimes clouded

by political,tribaland socialaffiliations (Nkusu,2011).According to Pina-Stranger

and Lazega (2011) and Sorenson and Rogan (2014),these challenges could be avoided

or their impact mitigated through a transparent decision making process (devoid of

personal ties and affiliations) for selecting start-up businesses.

These observations have led to a renewed interests in research aimed at improving the

performance of GVCs (Munari andToschi, 2015). One of such interest is a mechanism for a

transparent and efficient decision making process for determining the commercial viabilit

and the eventual selection of a technology start-up business in a government-run VC.

Any such decision-making mechanism must be able to address the problems listed

above including that of bias and favouritism.More importantly,the mechanism must

place greater importance on the need for effective management team for the success of

the start-up.

1.2 Research gap

Some non-fuzzy decision-making models for evaluating and selecting start-ups in VC

financing schemes have been proposed. Woike et al. (2015) used computer simulation to

study the impact of different strategies on the financial performance of VCs.Riquelme

and Rickards (1992)proposed a self-explicated,hybrid conjointmodelto aid the

selection of start-ups for financing in a VC scheme.These non-fuzzy methods rely on

historical data of past beneficiaries to arrive at a decision.This approach may not all

the time be appropriate for assessing and selecting early stage entrepreneurs that have

little or no past data and might lead to sub-optimaldecisions.Since future values of

data needed for evaluation are uncertain at the time of selection, fuzzy models that have

the ability to explicitly consider uncertainty in the models might be appropriate.

The main objective ofthis paper is therefore to propose a fuzzy multi-criteria

decision making (MCDM) model for the selection of start-ups in GVCs that addresses

the obvious uncertainty problems in such decision problems.It is also hoped that the

proposed approach would help generate interest regarding research in decision models

for VC selection problems.

In our search of literature,only the works of Zhang (2012),and Aouni et al.(2014),

attemptto use fuzzy theory for selecting start-up businesses in a VC.Aounietal.

(2014) used a fuzzy goal programming approach to model uncertainty.However,such

models cannotaccommodate qualitative factors such as leadership experience and

productquality.Zhang (2012),considers fuzziness butonly in the weights ofthe

evaluators and not in the values for the competing start-up candidates.Zhang (2012)

also does not explicitly modeluncertainty but instead attempts to overcome it using

entropy techniqueto determinethe weights.The modelby Zhang (2012)is a

combination ofan optimization and a multi-attribute modelthatseeks to selecta

candidatebased on maximizing risk-adjusted returns.In contrast,our proposed

approach uses a multi-attribute model to generate a composite index that however takes

qualitative factors as wellas a “more is better” and a “less is better” criterion into

account. By considering uncertainties directly in the values for assessment, the proposed

intuitionisticfuzzy techniquefor orderpreferenceby similarity to idealsolution

(TOPSIS) framework is thus more efficient at modelling the natural thought processes of

717

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

humans in decision making.The proposed decision framework also includes selectio

criteria specially tailored to address challenges faced by GVCs such as bias and

favouritism,as wellas ascertaining the effectiveness of the management team of

start-ups.The proposed method in particular can be used to help address some o

challenges encountered in the selection of start-up businesses especially in a g

high priority area such as in informationsystems/informationcommunication

technology (IS/IT) sectors.This is because selecting the ideal start-up to support in IS

IT areas can be very challenging and complex since most of the criteria involve

subjective or hold uncertain data (Pina-Stranger and Lazega,2011).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.First,an elaborate selection criteria

that hinge on the attainment of the objectives of a GVC and the success of the

business culled from literature is introduced.This is followed by a methodology

comprising ofan introduction to classicalfuzzy settheory and its extension into

intuitionisticfuzzy sets(IFS), especially asused in decision making.Next is

a systematic outline with definitions and formulas ofintuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS

method to help select potential candidates in a highly competitive but limited f

situation in a GVC programme. Finally, a numerical example of how intuitionisti

TOPSIS could be used to rank and select high-potentialstart-ups in a government

backed VC is illustrated.

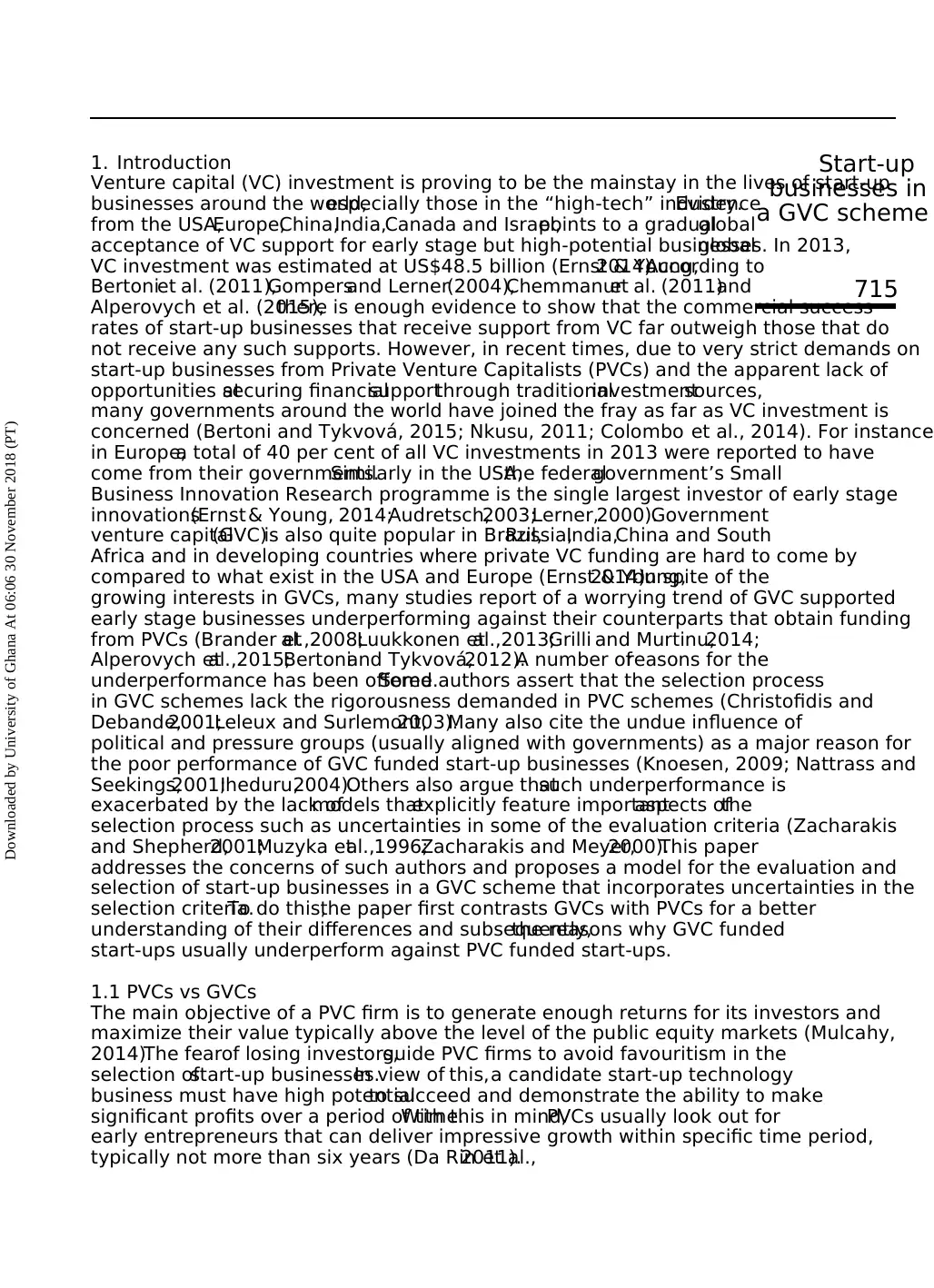

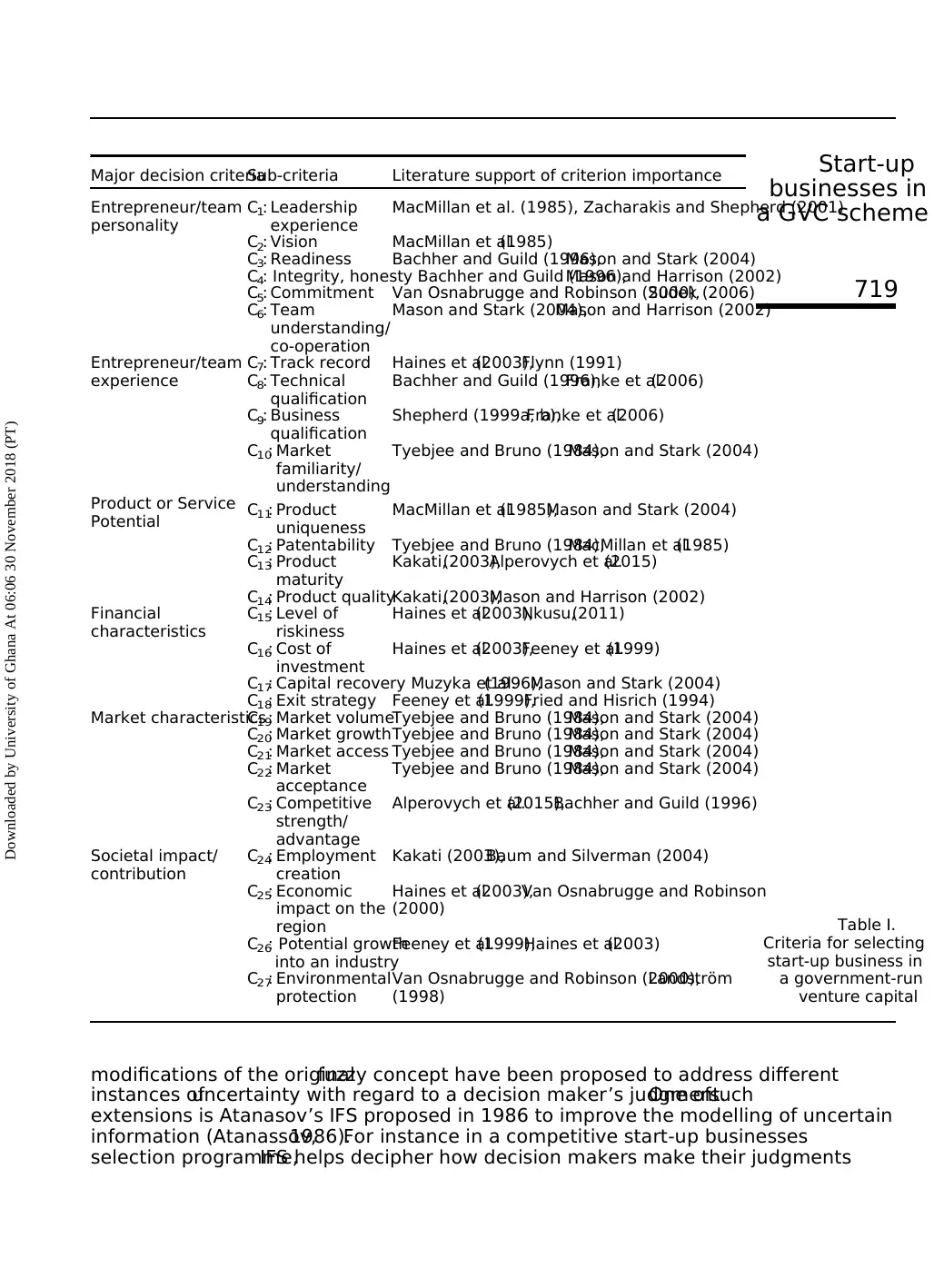

2. GVC funded start-up business selection criteria

Severalauthors have researched into the main criteria used by venture capitalis

evaluate start-up businesses.Table I summarizes major works on these criteria in the

literature,particularly those relevant to GVC schemes.The criteria under entrepreneur/

team personality,entrepreneur/team experience,and product or service potential,model

qualitativeattributeswhiles the criteriaunderfinancialcharacteristics,market

characteristicsand socialimpact/contribution modelquantitativecriteria.As can

be perceived from the criteria,the relevantvalues needed for evaluation cannotbe

determined in the present time but must be estimated based on the judgemen

In classicaldecision analysis,possible outcomes with their probabilities of occurrenc

would be considered in the final decision making.In the case where qualitative criteria

are present,such uncertainty can be modelled using fuzzy theory thatis able to

accommodate both qualitative and quantitative criteria.The next section gives brief

introduction to fuzzy theory and its extension to intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS.

3. Methodology

3.1 Modelling subjectivity with IFS

According to Hisrich and Jankowicz (1990) and Mitchell et al. (2005), venture ca

use many subjective criteria and intuition in their decision making.In view of this,

research mustfocuson developing methodsthat modelthe intuition and the

subjectiveness in the selection process. This section introduces the fuzzy conce

generally used to model intuition and subjectivity in human decision making pr

such as that of start-up business selection. The notion of fuzzy set theory was p

by Zadeh (1965)as a mathematical construct to help dealwith issues of uncertainty,

subjectivities,vaguenessand imprecisionin humanjudgments(Afful-Dadzie

et al.,2014).Since the conception of fuzzy set theory,it has successfully been applied

in many areas including situations that demand efficient modelling of human d

and judgments (Wang,1999;Klir and Yuan,1995).In addition,several extensions and

718

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

criteria specially tailored to address challenges faced by GVCs such as bias and

favouritism,as wellas ascertaining the effectiveness of the management team of

start-ups.The proposed method in particular can be used to help address some o

challenges encountered in the selection of start-up businesses especially in a g

high priority area such as in informationsystems/informationcommunication

technology (IS/IT) sectors.This is because selecting the ideal start-up to support in IS

IT areas can be very challenging and complex since most of the criteria involve

subjective or hold uncertain data (Pina-Stranger and Lazega,2011).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.First,an elaborate selection criteria

that hinge on the attainment of the objectives of a GVC and the success of the

business culled from literature is introduced.This is followed by a methodology

comprising ofan introduction to classicalfuzzy settheory and its extension into

intuitionisticfuzzy sets(IFS), especially asused in decision making.Next is

a systematic outline with definitions and formulas ofintuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS

method to help select potential candidates in a highly competitive but limited f

situation in a GVC programme. Finally, a numerical example of how intuitionisti

TOPSIS could be used to rank and select high-potentialstart-ups in a government

backed VC is illustrated.

2. GVC funded start-up business selection criteria

Severalauthors have researched into the main criteria used by venture capitalis

evaluate start-up businesses.Table I summarizes major works on these criteria in the

literature,particularly those relevant to GVC schemes.The criteria under entrepreneur/

team personality,entrepreneur/team experience,and product or service potential,model

qualitativeattributeswhiles the criteriaunderfinancialcharacteristics,market

characteristicsand socialimpact/contribution modelquantitativecriteria.As can

be perceived from the criteria,the relevantvalues needed for evaluation cannotbe

determined in the present time but must be estimated based on the judgemen

In classicaldecision analysis,possible outcomes with their probabilities of occurrenc

would be considered in the final decision making.In the case where qualitative criteria

are present,such uncertainty can be modelled using fuzzy theory thatis able to

accommodate both qualitative and quantitative criteria.The next section gives brief

introduction to fuzzy theory and its extension to intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS.

3. Methodology

3.1 Modelling subjectivity with IFS

According to Hisrich and Jankowicz (1990) and Mitchell et al. (2005), venture ca

use many subjective criteria and intuition in their decision making.In view of this,

research mustfocuson developing methodsthat modelthe intuition and the

subjectiveness in the selection process. This section introduces the fuzzy conce

generally used to model intuition and subjectivity in human decision making pr

such as that of start-up business selection. The notion of fuzzy set theory was p

by Zadeh (1965)as a mathematical construct to help dealwith issues of uncertainty,

subjectivities,vaguenessand imprecisionin humanjudgments(Afful-Dadzie

et al.,2014).Since the conception of fuzzy set theory,it has successfully been applied

in many areas including situations that demand efficient modelling of human d

and judgments (Wang,1999;Klir and Yuan,1995).In addition,several extensions and

718

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

modifications of the originalfuzzy concept have been proposed to address different

instances ofuncertainty with regard to a decision maker’s judgment.One ofsuch

extensions is Atanasov’s IFS proposed in 1986 to improve the modelling of uncertain

information (Atanassov,1986).For instance in a competitive start-up businesses

selection programme,IFS helps decipher how decision makers make their judgments

Major decision criteriaSub-criteria Literature support of criterion importance

Entrepreneur/team

personality

C1: Leadership

experience

MacMillan et al. (1985), Zacharakis and Shepherd (2001)

C2: Vision MacMillan et al.(1985)

C3: Readiness Bachher and Guild (1996),Mason and Stark (2004)

C4: Integrity, honesty Bachher and Guild (1996),Mason and Harrison (2002)

C5: Commitment Van Osnabrugge and Robinson (2000),Sudek (2006)

C6: Team

understanding/

co-operation

Mason and Stark (2004),Mason and Harrison (2002)

Entrepreneur/team

experience

C7: Track record Haines et al.(2003),Flynn (1991)

C8: Technical

qualification

Bachher and Guild (1996),Franke et al.(2006)

C9: Business

qualification

Shepherd (1999a, b),Franke et al.(2006)

C10: Market

familiarity/

understanding

Tyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

Product or Service

Potential C11: Product

uniqueness

MacMillan et al.(1985),Mason and Stark (2004)

C12: Patentability Tyebjee and Bruno (1984),MacMillan et al.(1985)

C13: Product

maturity

Kakati,(2003),Alperovych et al.(2015)

C14: Product qualityKakati,(2003),Mason and Harrison (2002)

Financial

characteristics

C15: Level of

riskiness

Haines et al.(2003),Nkusu,(2011)

C16: Cost of

investment

Haines et al.(2003),Feeney et al.(1999)

C17: Capital recovery Muzyka et al.(1996),Mason and Stark (2004)

C18: Exit strategy Feeney et al.(1999),Fried and Hisrich (1994)

Market characteristicsC19: Market volumeTyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

C20: Market growthTyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

C21: Market access Tyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

C22: Market

acceptance

Tyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

C23: Competitive

strength/

advantage

Alperovych et al.(2015),Bachher and Guild (1996)

Societal impact/

contribution

C24: Employment

creation

Kakati (2003),Baum and Silverman (2004)

C25: Economic

impact on the

region

Haines et al.(2003),Van Osnabrugge and Robinson

(2000)

C26: Potential growth

into an industry

Feeney et al.(1999),Haines et al.(2003)

C27: Environmental

protection

Van Osnabrugge and Robinson (2000),Landström

(1998)

Table I.

Criteria for selecting

start-up business in

a government-run

venture capital

719

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

instances ofuncertainty with regard to a decision maker’s judgment.One ofsuch

extensions is Atanasov’s IFS proposed in 1986 to improve the modelling of uncertain

information (Atanassov,1986).For instance in a competitive start-up businesses

selection programme,IFS helps decipher how decision makers make their judgments

Major decision criteriaSub-criteria Literature support of criterion importance

Entrepreneur/team

personality

C1: Leadership

experience

MacMillan et al. (1985), Zacharakis and Shepherd (2001)

C2: Vision MacMillan et al.(1985)

C3: Readiness Bachher and Guild (1996),Mason and Stark (2004)

C4: Integrity, honesty Bachher and Guild (1996),Mason and Harrison (2002)

C5: Commitment Van Osnabrugge and Robinson (2000),Sudek (2006)

C6: Team

understanding/

co-operation

Mason and Stark (2004),Mason and Harrison (2002)

Entrepreneur/team

experience

C7: Track record Haines et al.(2003),Flynn (1991)

C8: Technical

qualification

Bachher and Guild (1996),Franke et al.(2006)

C9: Business

qualification

Shepherd (1999a, b),Franke et al.(2006)

C10: Market

familiarity/

understanding

Tyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

Product or Service

Potential C11: Product

uniqueness

MacMillan et al.(1985),Mason and Stark (2004)

C12: Patentability Tyebjee and Bruno (1984),MacMillan et al.(1985)

C13: Product

maturity

Kakati,(2003),Alperovych et al.(2015)

C14: Product qualityKakati,(2003),Mason and Harrison (2002)

Financial

characteristics

C15: Level of

riskiness

Haines et al.(2003),Nkusu,(2011)

C16: Cost of

investment

Haines et al.(2003),Feeney et al.(1999)

C17: Capital recovery Muzyka et al.(1996),Mason and Stark (2004)

C18: Exit strategy Feeney et al.(1999),Fried and Hisrich (1994)

Market characteristicsC19: Market volumeTyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

C20: Market growthTyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

C21: Market access Tyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

C22: Market

acceptance

Tyebjee and Bruno (1984),Mason and Stark (2004)

C23: Competitive

strength/

advantage

Alperovych et al.(2015),Bachher and Guild (1996)

Societal impact/

contribution

C24: Employment

creation

Kakati (2003),Baum and Silverman (2004)

C25: Economic

impact on the

region

Haines et al.(2003),Van Osnabrugge and Robinson

(2000)

C26: Potential growth

into an industry

Feeney et al.(1999),Haines et al.(2003)

C27: Environmental

protection

Van Osnabrugge and Robinson (2000),Landström

(1998)

Table I.

Criteria for selecting

start-up business in

a government-run

venture capital

719

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

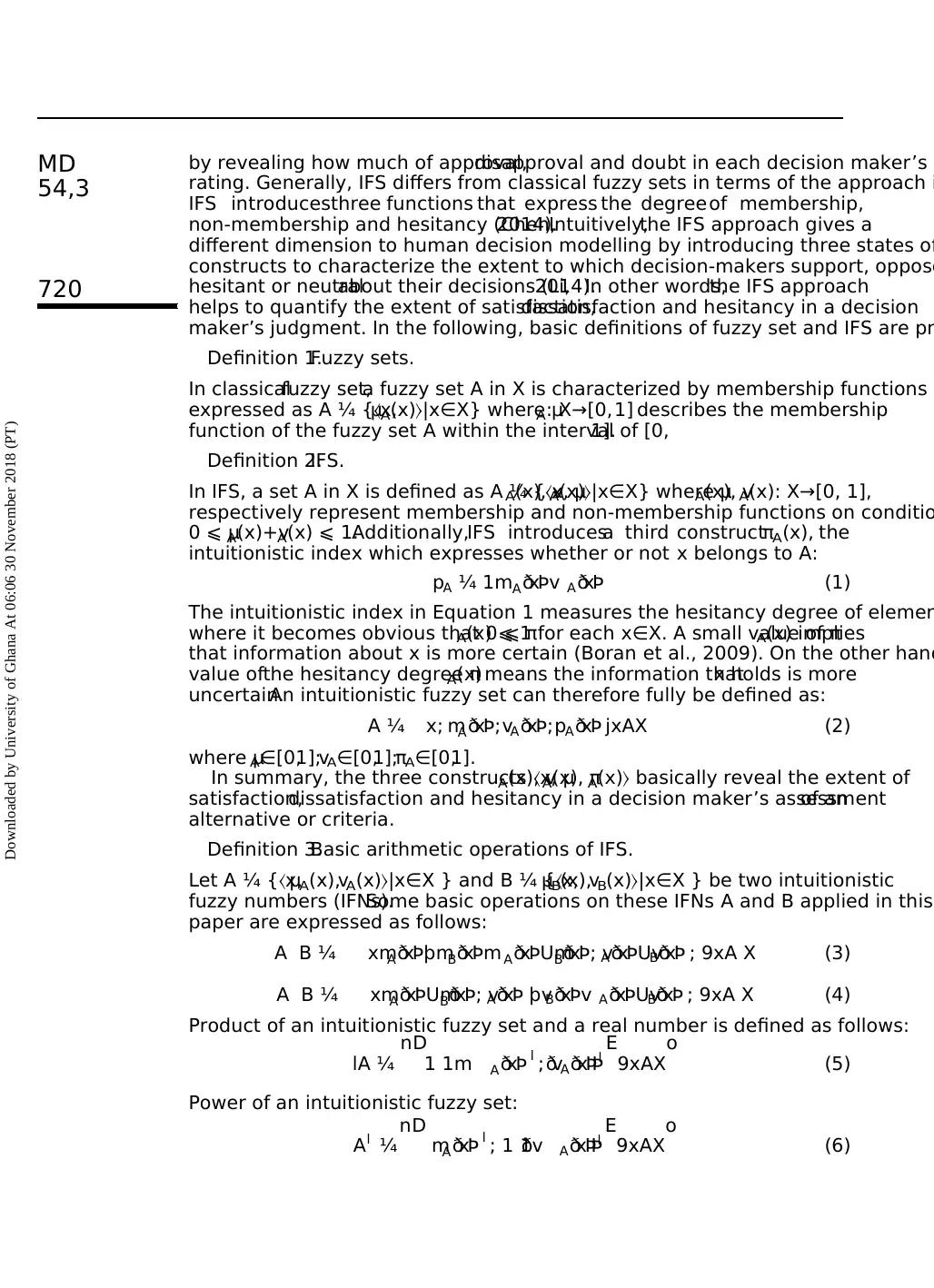

by revealing how much of approval,disapproval and doubt in each decision maker’s

rating. Generally, IFS differs from classical fuzzy sets in terms of the approach i

IFS introducesthree functions that express the degreeof membership,

non-membership and hesitancy (Chen,2014).Intuitively,the IFS approach gives a

different dimension to human decision modelling by introducing three states of

constructs to characterize the extent to which decision-makers support, oppose

hesitant or neutralabout their decisions (Li,2014).In other words,the IFS approach

helps to quantify the extent of satisfaction,dissatisfaction and hesitancy in a decision

maker’s judgment. In the following, basic definitions of fuzzy set and IFS are pr

Definition 1.Fuzzy sets.

In classicalfuzzy set,a fuzzy set A in X is characterized by membership functions

expressed as A ¼ {〈x,μA(x)〉|x∈X} where μA: X→[0,1] describes the membership

function of the fuzzy set A within the interval of [0,1].

Definition 2.IFS.

In IFS, a set A in X is defined as A ¼ {〈x, μA(x), vA(x)〉|x∈X} where μA(x), vA(x): X→[0, 1],

respectively represent membership and non-membership functions on conditio

0 ⩽ μA(x)+vA(x) ⩽ 1.Additionally,IFS introducesa third constructπA(x), the

intuitionistic index which expresses whether or not x belongs to A:

pA ¼ 1mA xð Þv A xð Þ (1)

The intuitionistic index in Equation 1 measures the hesitancy degree of elemen

where it becomes obvious that 0 ⩽ πA(x) ⩽ 1 for each x∈X. A small value of πA(x) implies

that information about x is more certain (Boran et al., 2009). On the other hand

value ofthe hesitancy degree πA(x) means the information thatx holds is more

uncertain.An intuitionistic fuzzy set can therefore fully be defined as:

A ¼ x; mA xð Þ;vA xð Þ;pA xð Þ xAXj (2)

where μA∈[0,1];vA∈[0,1];πA∈[0,1].

In summary, the three constructs 〈x, μA(x), vA(x), πA(x)〉 basically reveal the extent of

satisfaction,dissatisfaction and hesitancy in a decision maker’s assessmentof an

alternative or criteria.

Definition 3.Basic arithmetic operations of IFS.

Let A ¼ {〈x,μA(x),vA(x)〉|x∈X } and B ¼ {〈x,μB(x),vB(x)〉|x∈X } be two intuitionistic

fuzzy numbers (IFNs).Some basic operations on these IFNs A and B applied in this

paper are expressed as follows:

A B ¼ xmA xð ÞþmB xð Þm A xð ÞUmB xð Þ; vA xð ÞUvB xð Þ ; 9xA X (3)

A B ¼ xmA xð ÞUmB xð Þ; vA xð Þ þvB xð Þv A xð ÞUvB xð Þ ; 9xA X (4)

Product of an intuitionistic fuzzy set and a real number is defined as follows:

lA ¼ 1 1m A xð Þ l ; vA xð Þð Þl

D E

9xAX

n o

(5)

Power of an intuitionistic fuzzy set:

Al ¼ mA xð Þ l ; 1 1v A xð Þð Þl

D E

9xAX

n o

(6)

720

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

rating. Generally, IFS differs from classical fuzzy sets in terms of the approach i

IFS introducesthree functions that express the degreeof membership,

non-membership and hesitancy (Chen,2014).Intuitively,the IFS approach gives a

different dimension to human decision modelling by introducing three states of

constructs to characterize the extent to which decision-makers support, oppose

hesitant or neutralabout their decisions (Li,2014).In other words,the IFS approach

helps to quantify the extent of satisfaction,dissatisfaction and hesitancy in a decision

maker’s judgment. In the following, basic definitions of fuzzy set and IFS are pr

Definition 1.Fuzzy sets.

In classicalfuzzy set,a fuzzy set A in X is characterized by membership functions

expressed as A ¼ {〈x,μA(x)〉|x∈X} where μA: X→[0,1] describes the membership

function of the fuzzy set A within the interval of [0,1].

Definition 2.IFS.

In IFS, a set A in X is defined as A ¼ {〈x, μA(x), vA(x)〉|x∈X} where μA(x), vA(x): X→[0, 1],

respectively represent membership and non-membership functions on conditio

0 ⩽ μA(x)+vA(x) ⩽ 1.Additionally,IFS introducesa third constructπA(x), the

intuitionistic index which expresses whether or not x belongs to A:

pA ¼ 1mA xð Þv A xð Þ (1)

The intuitionistic index in Equation 1 measures the hesitancy degree of elemen

where it becomes obvious that 0 ⩽ πA(x) ⩽ 1 for each x∈X. A small value of πA(x) implies

that information about x is more certain (Boran et al., 2009). On the other hand

value ofthe hesitancy degree πA(x) means the information thatx holds is more

uncertain.An intuitionistic fuzzy set can therefore fully be defined as:

A ¼ x; mA xð Þ;vA xð Þ;pA xð Þ xAXj (2)

where μA∈[0,1];vA∈[0,1];πA∈[0,1].

In summary, the three constructs 〈x, μA(x), vA(x), πA(x)〉 basically reveal the extent of

satisfaction,dissatisfaction and hesitancy in a decision maker’s assessmentof an

alternative or criteria.

Definition 3.Basic arithmetic operations of IFS.

Let A ¼ {〈x,μA(x),vA(x)〉|x∈X } and B ¼ {〈x,μB(x),vB(x)〉|x∈X } be two intuitionistic

fuzzy numbers (IFNs).Some basic operations on these IFNs A and B applied in this

paper are expressed as follows:

A B ¼ xmA xð ÞþmB xð Þm A xð ÞUmB xð Þ; vA xð ÞUvB xð Þ ; 9xA X (3)

A B ¼ xmA xð ÞUmB xð Þ; vA xð Þ þvB xð Þv A xð ÞUvB xð Þ ; 9xA X (4)

Product of an intuitionistic fuzzy set and a real number is defined as follows:

lA ¼ 1 1m A xð Þ l ; vA xð Þð Þl

D E

9xAX

n o

(5)

Power of an intuitionistic fuzzy set:

Al ¼ mA xð Þ l ; 1 1v A xð Þð Þl

D E

9xAX

n o

(6)

720

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

3.2 Intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS

The TOPSIS method was proposed by Hwang and Yoon (1981) and has since become

one ofthe popular techniques in MCDM.Like the originalTOPSIS method,fuzzy

TOPSIS also relies on the so-called shortestdistance from the fuzzy positive ideal

solution (FPIS) and the farthest distance from the fuzzy negative ideal solution (FNIS)

to determinethe best alternative.The FNIS maximizesthe cost criteriaand

minimizes the benefit criteria,whiles FPIS maximizes benefit criteria and minimizes

costcriteria.The alternatives are ranked and selected according to theirrelative

closenessdetermined using thetwo distancemeasures.Similarly,the extension

of TOPSIS into IFS also maintains the key features such as the FPIS and the FNIS

(Boran et al.,2009).In the following,we outline the proposed method that incorporates

IFS into fuzzy TOPSIS.

3.3 Steps for Intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS

Step 1. Determining sets of alternatives, criteria, linguistic variables and decision-makers

As it is usual with MCDM methods, the alternatives to be ranked, the criteria to be used

in the ratings and the group of decision-makers are determined.In view of this,let

A ¼ {A1, A2, ..., Am} be the set of alternatives to be considered,C ¼ {C1, C2, ..., Cn},the

set of criteria and, k ¼ {D1, D2, …, Dd} the sets of decision makers. Equation (7), shows

a decision matrix for decision maker,k ¼ 1,2, …, d:

C1 C2 Cn

~k ¼

A1

A2

^

Am

~x11 ~x12 ~x1n

~x21 ~x22 ~x2n

^ ^ & ^

~xm1 ~xm2 ~xmn

2

6

6

6

4

3

7

7

7

5; i ¼ 1;2; . . .;m; j ¼ 1;2; . . .;n (7)

where~xij is the rating of alternative Ai with respect to criterion Cj both expressed in

IFS. This implies that the rating of a decisionmaker k is expressedas

~xk

ij ¼ / ~uk

ij; ~vk

ij; ~pk

iji. Additionally,the linguistic variables (criteria)to be used in the

assessment of start-up candidates are determined.The linguistic variables are further

expressed in linguistic terms and used to rate the performance of each alternative with

respect to a linguistic variable (Kuo and Liang,2012).In this paper,the format of the

linguistic terms are expressed in IFNs as seen in Table II.Linguistic terms are

qualitative words thatdescribe the subjective view ofa decision makerabouta

criterion with respect to each alternative (Klir and Yuan, 1995). In Table II the linguistic

terms and their IFNs are presented.

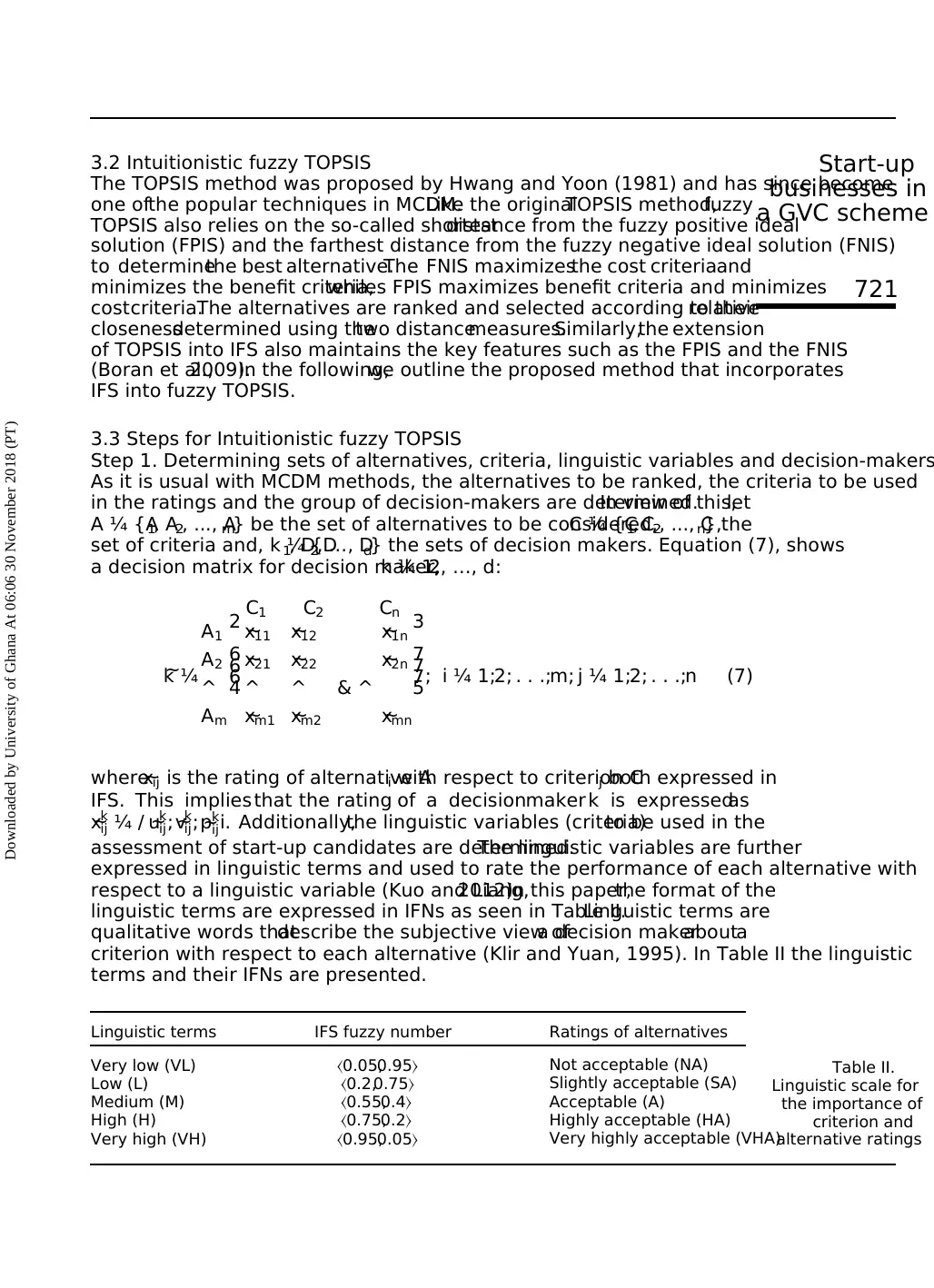

Linguistic terms IFS fuzzy number Ratings of alternatives

Very low (VL) 〈0.05,0.95〉 Not acceptable (NA)

Low (L) 〈0.2,0.75〉 Slightly acceptable (SA)

Medium (M) 〈0.55,0.4〉 Acceptable (A)

High (H) 〈0.75,0.2〉 Highly acceptable (HA)

Very high (VH) 〈0.95,0.05〉 Very highly acceptable (VHA)

Table II.

Linguistic scale for

the importance of

criterion and

alternative ratings

721

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

The TOPSIS method was proposed by Hwang and Yoon (1981) and has since become

one ofthe popular techniques in MCDM.Like the originalTOPSIS method,fuzzy

TOPSIS also relies on the so-called shortestdistance from the fuzzy positive ideal

solution (FPIS) and the farthest distance from the fuzzy negative ideal solution (FNIS)

to determinethe best alternative.The FNIS maximizesthe cost criteriaand

minimizes the benefit criteria,whiles FPIS maximizes benefit criteria and minimizes

costcriteria.The alternatives are ranked and selected according to theirrelative

closenessdetermined using thetwo distancemeasures.Similarly,the extension

of TOPSIS into IFS also maintains the key features such as the FPIS and the FNIS

(Boran et al.,2009).In the following,we outline the proposed method that incorporates

IFS into fuzzy TOPSIS.

3.3 Steps for Intuitionistic fuzzy TOPSIS

Step 1. Determining sets of alternatives, criteria, linguistic variables and decision-makers

As it is usual with MCDM methods, the alternatives to be ranked, the criteria to be used

in the ratings and the group of decision-makers are determined.In view of this,let

A ¼ {A1, A2, ..., Am} be the set of alternatives to be considered,C ¼ {C1, C2, ..., Cn},the

set of criteria and, k ¼ {D1, D2, …, Dd} the sets of decision makers. Equation (7), shows

a decision matrix for decision maker,k ¼ 1,2, …, d:

C1 C2 Cn

~k ¼

A1

A2

^

Am

~x11 ~x12 ~x1n

~x21 ~x22 ~x2n

^ ^ & ^

~xm1 ~xm2 ~xmn

2

6

6

6

4

3

7

7

7

5; i ¼ 1;2; . . .;m; j ¼ 1;2; . . .;n (7)

where~xij is the rating of alternative Ai with respect to criterion Cj both expressed in

IFS. This implies that the rating of a decisionmaker k is expressedas

~xk

ij ¼ / ~uk

ij; ~vk

ij; ~pk

iji. Additionally,the linguistic variables (criteria)to be used in the

assessment of start-up candidates are determined.The linguistic variables are further

expressed in linguistic terms and used to rate the performance of each alternative with

respect to a linguistic variable (Kuo and Liang,2012).In this paper,the format of the

linguistic terms are expressed in IFNs as seen in Table II.Linguistic terms are

qualitative words thatdescribe the subjective view ofa decision makerabouta

criterion with respect to each alternative (Klir and Yuan, 1995). In Table II the linguistic

terms and their IFNs are presented.

Linguistic terms IFS fuzzy number Ratings of alternatives

Very low (VL) 〈0.05,0.95〉 Not acceptable (NA)

Low (L) 〈0.2,0.75〉 Slightly acceptable (SA)

Medium (M) 〈0.55,0.4〉 Acceptable (A)

High (H) 〈0.75,0.2〉 Highly acceptable (HA)

Very high (VH) 〈0.95,0.05〉 Very highly acceptable (VHA)

Table II.

Linguistic scale for

the importance of

criterion and

alternative ratings

721

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

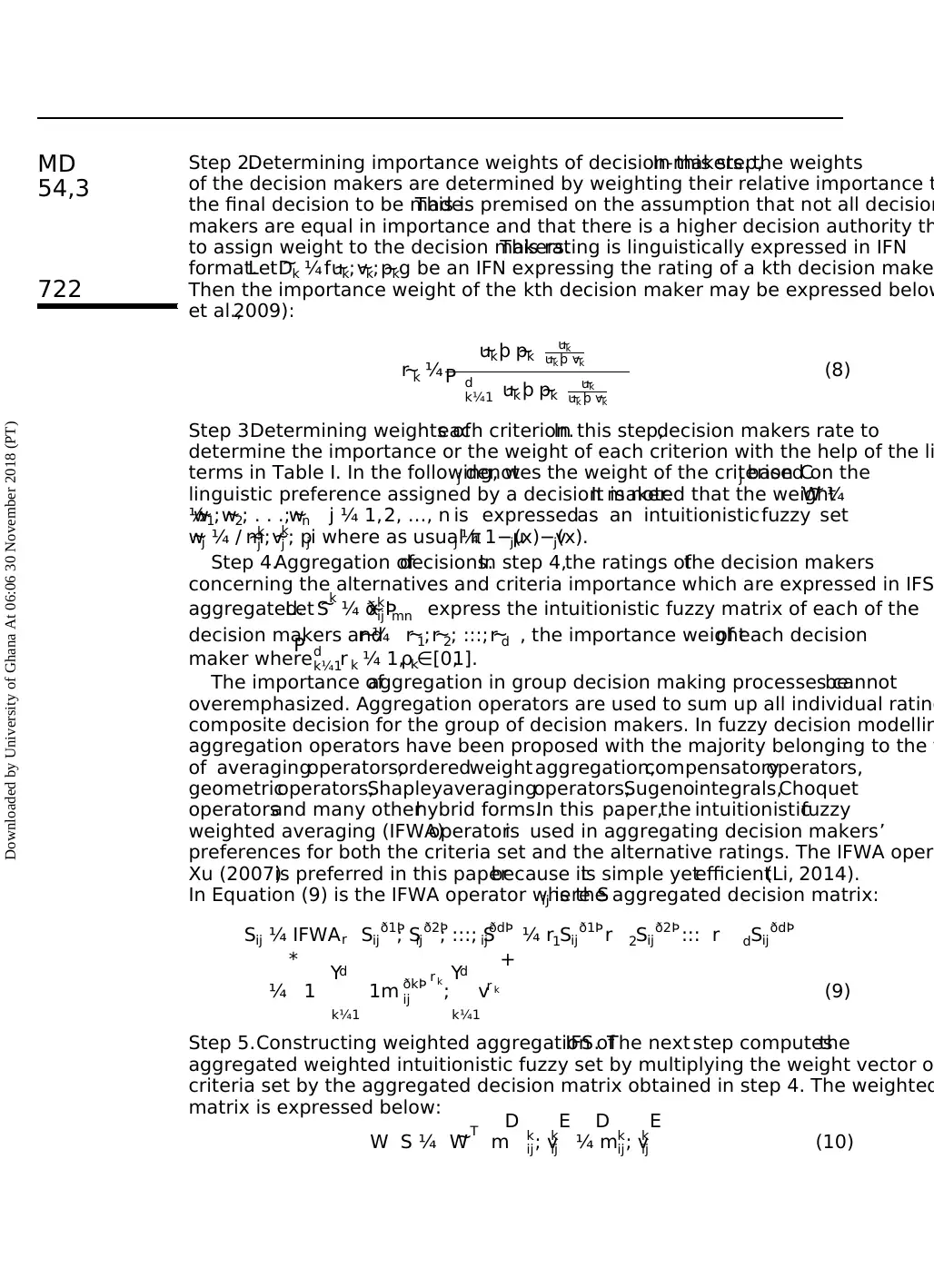

Step 2.Determining importance weights of decision-makers.In this step,the weights

of the decision makers are determined by weighting their relative importance t

the final decision to be made.This is premised on the assumption that not all decision

makers are equal in importance and that there is a higher decision authority th

to assign weight to the decision makers.This rating is linguistically expressed in IFN

format.Let ~Dk ¼ ~uk; ~vk; ~pkf g be an IFN expressing the rating of a kth decision make

Then the importance weight of the kth decision maker may be expressed below

et al.,2009):

~r k ¼

~ukþ ~pk ~uk

~uk þ ~vk

P d

k¼1 ~uk þ ~pk ~uk

~uk þ ~vk

(8)

Step 3.Determining weights ofeach criterion.In this step,decision makers rate to

determine the importance or the weight of each criterion with the help of the li

terms in Table I. In the following, wj denotes the weight of the criterion Cj based on the

linguistic preference assigned by a decision maker.It is noted that the weight~W ¼

~w1; ~w2; . . .;~wn½ j ¼ 1,2, …, n is expressedas an intuitionisticfuzzy set

~wj ¼ / ~mk

j ; ~vk

j ; pji where as usual πj ¼ 1−μj(x)−vj(x).

Step 4.Aggregation ofdecisions.In step 4,the ratings ofthe decision makers

concerning the alternatives and criteria importance which are expressed in IFS

aggregated.Let ~Sk ¼ ð~xk

ijÞmn express the intuitionistic fuzzy matrix of each of the

decision makers and~r ¼ ~r 1; ~r 2; :::; ~r d , the importance weightof each decision

maker where

P d

k¼1r k ¼ 1,ρk∈[0,1].

The importance ofaggregation in group decision making processes cannotbe

overemphasized. Aggregation operators are used to sum up all individual rating

composite decision for the group of decision makers. In fuzzy decision modellin

aggregation operators have been proposed with the majority belonging to the f

of averagingoperators,orderedweight aggregation,compensatoryoperators,

geometricoperators,Shapleyaveragingoperators,Sugenointegrals,Choquet

operatorsand many otherhybrid forms.In this paper,the intuitionisticfuzzy

weighted averaging (IFWA)operatoris used in aggregating decision makers’

preferences for both the criteria set and the alternative ratings. The IFWA opera

Xu (2007)is preferred in this paperbecause itis simple yetefficient(Li, 2014).

In Equation (9) is the IFWA operator where Sij is the aggregated decision matrix:

Sij ¼ IFWAr Sijð1Þ

; Sijð2Þ

; :::; SijðdÞ ¼ r1Sijð1Þ r 2Sijð2Þ ::: r dSijðdÞ

¼ 1 Yd

k¼1

1m ðkÞ

ij

r k

;Yd

k¼1

vr k

* +

(9)

Step 5.Constructing weighted aggregation ofIFS. The next step computesthe

aggregated weighted intuitionistic fuzzy set by multiplying the weight vector o

criteria set by the aggregated decision matrix obtained in step 4. The weighted

matrix is expressed below:

W S ¼ ~W T m k

ij; vk

ij

D E

¼ mk

ij; vk

ij

D E

(10)

722

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

of the decision makers are determined by weighting their relative importance t

the final decision to be made.This is premised on the assumption that not all decision

makers are equal in importance and that there is a higher decision authority th

to assign weight to the decision makers.This rating is linguistically expressed in IFN

format.Let ~Dk ¼ ~uk; ~vk; ~pkf g be an IFN expressing the rating of a kth decision make

Then the importance weight of the kth decision maker may be expressed below

et al.,2009):

~r k ¼

~ukþ ~pk ~uk

~uk þ ~vk

P d

k¼1 ~uk þ ~pk ~uk

~uk þ ~vk

(8)

Step 3.Determining weights ofeach criterion.In this step,decision makers rate to

determine the importance or the weight of each criterion with the help of the li

terms in Table I. In the following, wj denotes the weight of the criterion Cj based on the

linguistic preference assigned by a decision maker.It is noted that the weight~W ¼

~w1; ~w2; . . .;~wn½ j ¼ 1,2, …, n is expressedas an intuitionisticfuzzy set

~wj ¼ / ~mk

j ; ~vk

j ; pji where as usual πj ¼ 1−μj(x)−vj(x).

Step 4.Aggregation ofdecisions.In step 4,the ratings ofthe decision makers

concerning the alternatives and criteria importance which are expressed in IFS

aggregated.Let ~Sk ¼ ð~xk

ijÞmn express the intuitionistic fuzzy matrix of each of the

decision makers and~r ¼ ~r 1; ~r 2; :::; ~r d , the importance weightof each decision

maker where

P d

k¼1r k ¼ 1,ρk∈[0,1].

The importance ofaggregation in group decision making processes cannotbe

overemphasized. Aggregation operators are used to sum up all individual rating

composite decision for the group of decision makers. In fuzzy decision modellin

aggregation operators have been proposed with the majority belonging to the f

of averagingoperators,orderedweight aggregation,compensatoryoperators,

geometricoperators,Shapleyaveragingoperators,Sugenointegrals,Choquet

operatorsand many otherhybrid forms.In this paper,the intuitionisticfuzzy

weighted averaging (IFWA)operatoris used in aggregating decision makers’

preferences for both the criteria set and the alternative ratings. The IFWA opera

Xu (2007)is preferred in this paperbecause itis simple yetefficient(Li, 2014).

In Equation (9) is the IFWA operator where Sij is the aggregated decision matrix:

Sij ¼ IFWAr Sijð1Þ

; Sijð2Þ

; :::; SijðdÞ ¼ r1Sijð1Þ r 2Sijð2Þ ::: r dSijðdÞ

¼ 1 Yd

k¼1

1m ðkÞ

ij

r k

;Yd

k¼1

vr k

* +

(9)

Step 5.Constructing weighted aggregation ofIFS. The next step computesthe

aggregated weighted intuitionistic fuzzy set by multiplying the weight vector o

criteria set by the aggregated decision matrix obtained in step 4. The weighted

matrix is expressed below:

W S ¼ ~W T m k

ij; vk

ij

D E

¼ mk

ij; vk

ij

D E

(10)

722

MD

54,3

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

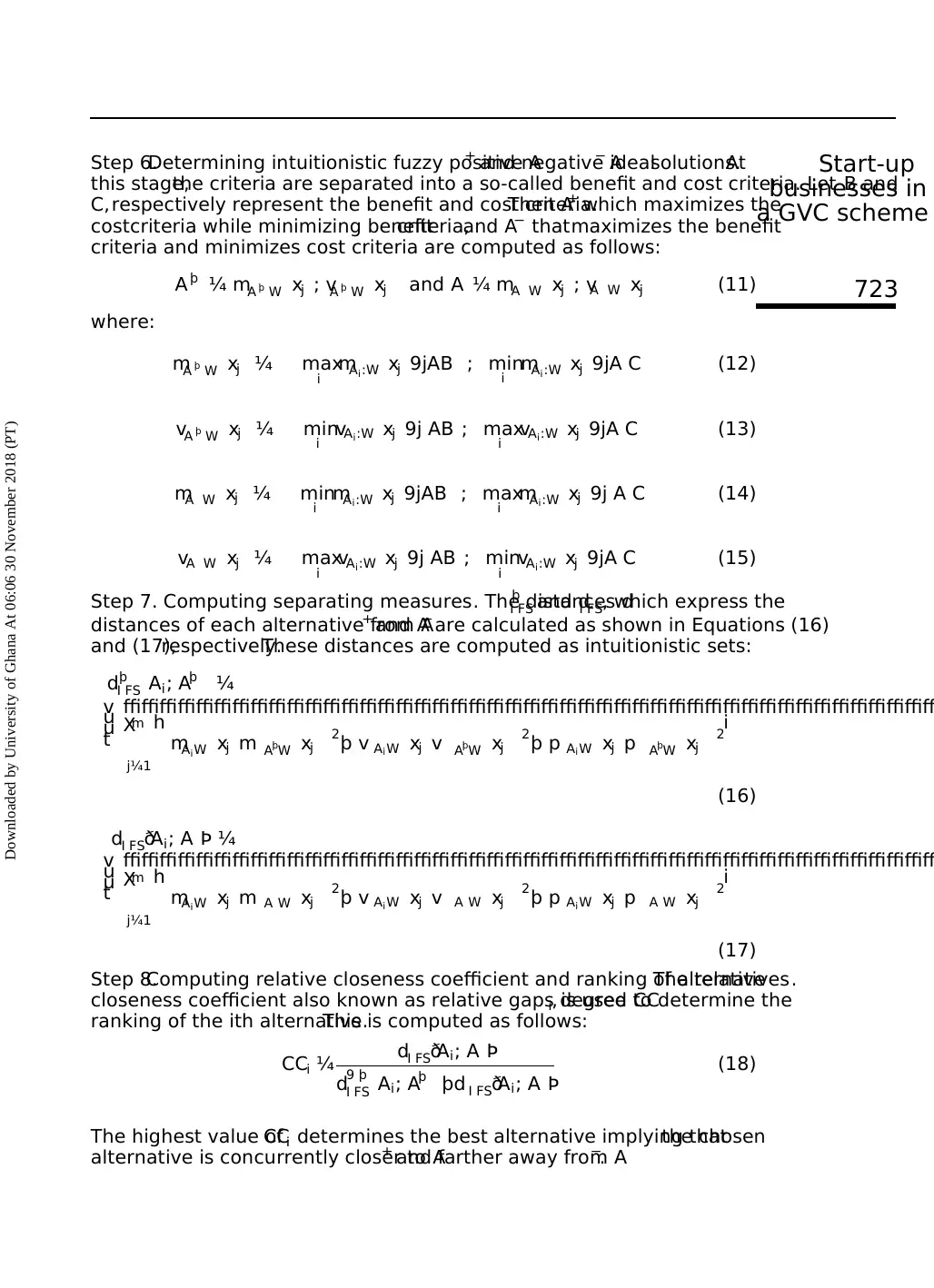

Step 6.Determining intuitionistic fuzzy positive A+ and negative A− idealsolutions.At

this stage,the criteria are separated into a so-called benefit and cost criteria. Let B and

C,respectively represent the benefit and cost criteria.Then A+ which maximizes the

costcriteria while minimizing benefitcriteria,and A− thatmaximizes the benefit

criteria and minimizes cost criteria are computed as follows:

A þ ¼ mA þ W xj ; vA þ W xj and A ¼ mA W xj ; vA W xj (11)

where:

mA þ W xj ¼ max

i mAi :W xj 9jAB ; min

i mAi :W xj 9jA C (12)

vA þ W xj ¼ min

i vAi:W xj 9j AB ; max

i vAi :W xj 9jA C (13)

mA W xj ¼ min

i mAi:W xj 9jAB ; max

i

mAi:W xj 9j A C (14)

vA W xj ¼ max

i vAi:W xj 9j AB ; min

i vAi:W xj 9jA C (15)

Step 7. Computing separating measures. The distances dþ

I FS and dI FS, which express the

distances of each alternative from A+ and A− are calculated as shown in Equations (16)

and (17),respectively.These distances are computed as intuitionistic sets:

dþ

I FS Ai; Aþ ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

Xm

j¼1

mAiW xj m AþW xj

2þ v Ai W xj v AþW xj

2þ p Ai W xj p AþW xj

2

h i

v

u

u

t

(16)

dI FS Ai; Að Þ ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

Xm

j¼1

mAiW xj m A W xj

2þ v Ai W xj v A W xj

2þ p Ai W xj p A W xj

2

h i

v

u

u

t

(17)

Step 8.Computing relative closeness coefficient and ranking of alternatives.The relative

closeness coefficient also known as relative gaps degree CCi, is used to determine the

ranking of the ith alternative.This is computed as follows:

CCi ¼ dI FS Ai; Að Þ

d9 þ

I FS Ai; Aþ þd I FS Ai; Að Þ

(18)

The highest value ofCCi determines the best alternative implying thatthe chosen

alternative is concurrently closer to A+ and farther away from A−.

723

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

this stage,the criteria are separated into a so-called benefit and cost criteria. Let B and

C,respectively represent the benefit and cost criteria.Then A+ which maximizes the

costcriteria while minimizing benefitcriteria,and A− thatmaximizes the benefit

criteria and minimizes cost criteria are computed as follows:

A þ ¼ mA þ W xj ; vA þ W xj and A ¼ mA W xj ; vA W xj (11)

where:

mA þ W xj ¼ max

i mAi :W xj 9jAB ; min

i mAi :W xj 9jA C (12)

vA þ W xj ¼ min

i vAi:W xj 9j AB ; max

i vAi :W xj 9jA C (13)

mA W xj ¼ min

i mAi:W xj 9jAB ; max

i

mAi:W xj 9j A C (14)

vA W xj ¼ max

i vAi:W xj 9j AB ; min

i vAi:W xj 9jA C (15)

Step 7. Computing separating measures. The distances dþ

I FS and dI FS, which express the

distances of each alternative from A+ and A− are calculated as shown in Equations (16)

and (17),respectively.These distances are computed as intuitionistic sets:

dþ

I FS Ai; Aþ ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

Xm

j¼1

mAiW xj m AþW xj

2þ v Ai W xj v AþW xj

2þ p Ai W xj p AþW xj

2

h i

v

u

u

t

(16)

dI FS Ai; Að Þ ¼

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

Xm

j¼1

mAiW xj m A W xj

2þ v Ai W xj v A W xj

2þ p Ai W xj p A W xj

2

h i

v

u

u

t

(17)

Step 8.Computing relative closeness coefficient and ranking of alternatives.The relative

closeness coefficient also known as relative gaps degree CCi, is used to determine the

ranking of the ith alternative.This is computed as follows:

CCi ¼ dI FS Ai; Að Þ

d9 þ

I FS Ai; Aþ þd I FS Ai; Að Þ

(18)

The highest value ofCCi determines the best alternative implying thatthe chosen

alternative is concurrently closer to A+ and farther away from A−.

723

Start-up

businesses in

a GVC scheme

Downloaded by University of Ghana At 06:06 30 November 2018 (PT)

4. Application

The Governmentof South Africa has instituted a number ofpro entrepreneurial

initiatives that is run by the Department of Trade and Industry and the Econom

Development department.One of such initiatives is the Technology Venture Capital

Fund,a government publicly run VC scheme.The GVC among other things offers

seed capitalto high potentialbut early stage technology firms to trigger growth

(Government of South Africa,2015).The fund primarily supports commercialization

of technology-focused innovations to help create jobs and wealth for the citizen

(Governmentof South Africa,2015;Koekemoerand Kachieng’a,2002).Since its

introduction,the fund has supported many businesses with some relative success

but largely,most businesses failed to achieve commercialsuccess resulting in low

capital recovery rates.Rogerson (2004) notes that most government venture schem

for small, medium and micro enterprises fail because often time start-ups that

potentialfor success are discriminated in favourof start-ups with links to the

government. Knoesen (2009), Nattrass and Seekings (2001) and Iheduru (2004

that the influence ofpolitical,social,racialand tribalaffiliations often lead to

misappropriation ofpublic funds and therefore need to be curbed to ensure the

success of such funds.In what follows,a numerical example showing step by step,

how the proposed fuzzy intuitionistic TOPSIS method can be used to evaluate a

select start-up businesses under GVC’s such as that operated by the Governme

South Africa is presented.

4.1 Step 1.Determining sets of alternatives, criteria, linguistic variables and deci

makers

The first step involves the identification of linguistic variables,linguistic terms,the

alternatives and decision makers. Table I lists the 27 sets of criteria deemed re

the selection problem.Table II also shows the linguistic terms used in rating both th

importance criteria and the alternatives expressed in their IFN format.The numerical

example has five start-up businesses and four decision makers.

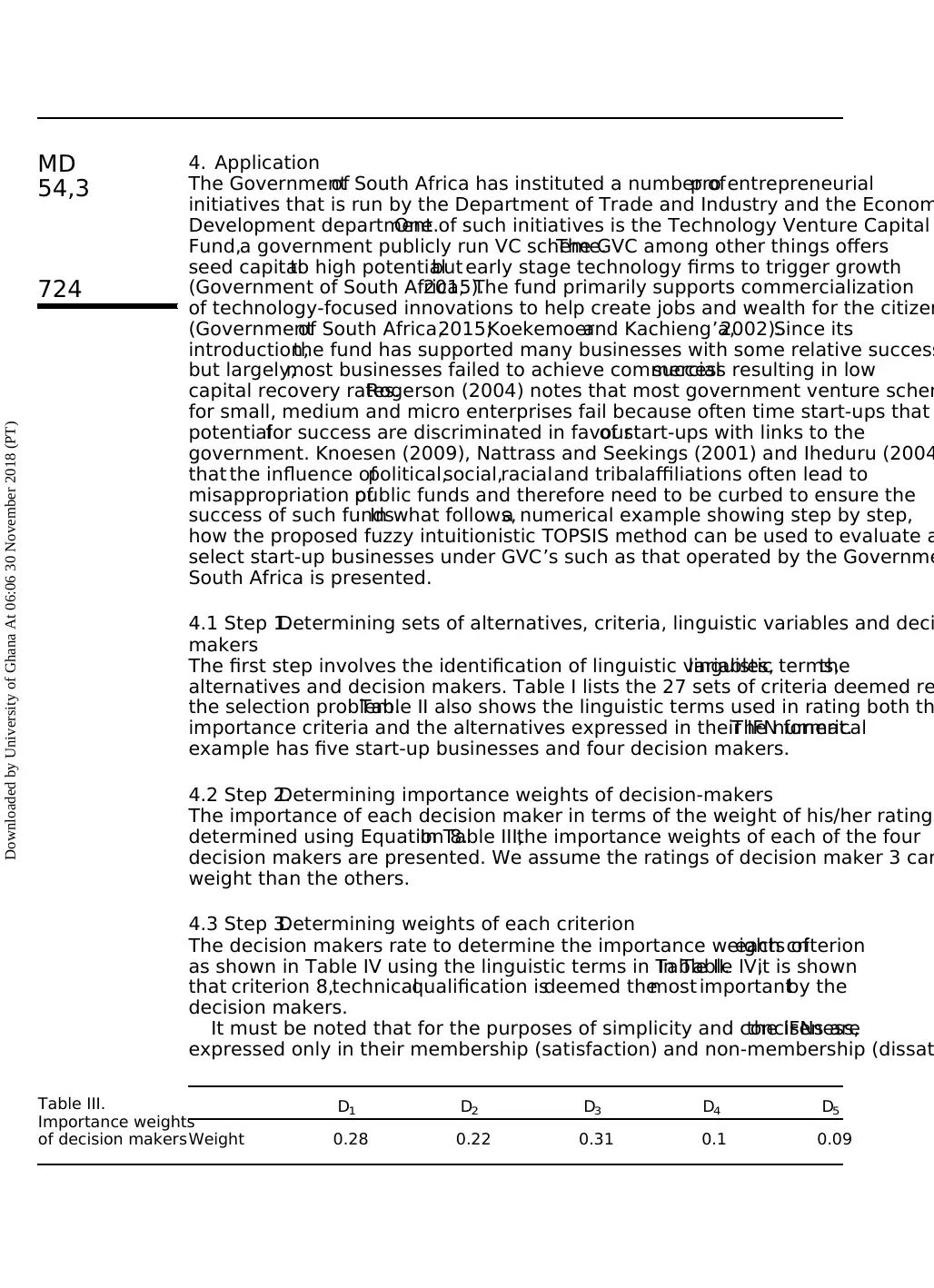

4.2 Step 2.Determining importance weights of decision-makers

The importance of each decision maker in terms of the weight of his/her ratings

determined using Equation 8.In Table III,the importance weights of each of the four