Detailed Analysis and Report on Haematology and Blood Transfusion

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/13

|13

|3720

|31

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of haematology and blood transfusion, covering key aspects such as extramedullary hematopoiesis, the diagnosis of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL), and the intricacies of the clotting cascade. Section A examines extramedullary hematopoiesis and ALL, including its classification and diagnostic procedures. Section B delves into the clotting cascade, differentiating between the intrinsic, extrinsic, and common pathways. The report also discusses the critical role of blood transfusions, their benefits, and potential adverse reactions, categorizing these reactions into acute and delayed responses, along with their respective management strategies. The report emphasizes the importance of understanding these processes for effective healthcare practices and patient management.

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 1

HAEMATOLOGY AND BLOOD TRANSFUSION

Student’s Name

Course

Professor’s Name

University

City (State)

Date

HAEMATOLOGY AND BLOOD TRANSFUSION

Student’s Name

Course

Professor’s Name

University

City (State)

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 2

Section A

Question One

a)

Extramedullary hematopoiesis (EH) involves the formation of blood components in the

peripheral organs. It may occur during the development of embryos or following immunological

responses. More also, extramedullary hematopoiesis may arise on pathological circumstances

secondary to unproductive hematopoiesis; for instance, it may be present in malignancies

associated with hematologic diseases (Zhang et al. 2016). Hematopoietic cell accumulation that

characterizes EH occurs in various body sites such as the spleen, lymph nodes, liver, adrenal

glands, nasopharyngeal regions, and malignant neoplasms. Spleens are the common sites for

extramedullary hematopoiesis; therefore, it provides a different place for assessing the

hematopoietic stem cells (Zhang et al. 2016). During embryonic development, extramedullary

hematopoiesis occurs in the yolk sac or spleen before bone marrows mature. More also, in the

immunological response to pathogens, EH occurs in the liver or spleen to produce antigen-

presenting cells (Crane, Jeffery & Morrison 2017). Besides, EH ensues in certain pathological

situations for instance, when the collagenous connective tissues replace the marrow cells. The

result is an inhabitable marrow for both the stem and progenitor cells (Crane, Jeffery & Morrison

2017).

b)

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL) is the cancer of the bone marrow in which the

immature lymphoblasts proliferate and substitute the healthy hematopoietic cells (Stephen et al.

2015). It occurs due to abnormal gene expression among individuals with chromosomal

dislocations often resulting in the production of fewer blood cells. More also, lymphoblast

Section A

Question One

a)

Extramedullary hematopoiesis (EH) involves the formation of blood components in the

peripheral organs. It may occur during the development of embryos or following immunological

responses. More also, extramedullary hematopoiesis may arise on pathological circumstances

secondary to unproductive hematopoiesis; for instance, it may be present in malignancies

associated with hematologic diseases (Zhang et al. 2016). Hematopoietic cell accumulation that

characterizes EH occurs in various body sites such as the spleen, lymph nodes, liver, adrenal

glands, nasopharyngeal regions, and malignant neoplasms. Spleens are the common sites for

extramedullary hematopoiesis; therefore, it provides a different place for assessing the

hematopoietic stem cells (Zhang et al. 2016). During embryonic development, extramedullary

hematopoiesis occurs in the yolk sac or spleen before bone marrows mature. More also, in the

immunological response to pathogens, EH occurs in the liver or spleen to produce antigen-

presenting cells (Crane, Jeffery & Morrison 2017). Besides, EH ensues in certain pathological

situations for instance, when the collagenous connective tissues replace the marrow cells. The

result is an inhabitable marrow for both the stem and progenitor cells (Crane, Jeffery & Morrison

2017).

b)

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL) is the cancer of the bone marrow in which the

immature lymphoblasts proliferate and substitute the healthy hematopoietic cells (Stephen et al.

2015). It occurs due to abnormal gene expression among individuals with chromosomal

dislocations often resulting in the production of fewer blood cells. More also, lymphoblast

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 3

infiltration causes enlargement of different organs such as the liver, spleen, or the lymphatic

system. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia is more prevalent among children than in adults

(Stephen et al. 2015).

There are several classification systems, and since its inception in 1976, the French-

American- British (FAB) system has classified acute lymphoblastic leukaemia according to

morphology. This system considers information about sizes, cytoplasm, nucleus, basophilia, and

vacuolation, which is the investigation of the various geometrical, chromatic, and textural

elements of the cytoplasm and nuclei (Rawat et al. 2017). FAB classifies ALL into three sub-

types: L1, L2, and L3. According to Mandal (2019), about 31% to 84% of the adult and children

incidents of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia fall in the L1 category. Cells under this category

have regular shapes and with homogenous nuclear chromatins. Besides, they have scanty

cytoplasms, small nucleoli and moderate basophilia (Mandal 2019). The cells in sub-subtype L2

are large and have irregular nuclear shapes. The cells have prominent nucleoli and variable

basophilia. These cells are heterogeneous with variable nuclear chromatins (Terwilliger &

Abdul-Hay 2017). Finally, the cells in sub-type L3 are large and exhibit homogenous chromatin.

These cells have regular nuclei and basophilic cytoplasm. Notably, the distinctive element in

ALL-L3 type is the prominent cytoplasmic vacuolation (Terwilliger & Abdul-Hay 2017).

Question Two

The vital step in the diagnosis of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL) is the

examination of any physical signs. Hematologists ought to take blood samples from the affected

organs such as the swollen glands. The presence of numerous white blood cells is a hallmark for

ALL. Cooper and Brown (2015) assert that 34%-38% of children with ALL present a white

blood cell count of more than 20 x 10˄9/L. In this case, the 10-year old child whose WBC is 50

infiltration causes enlargement of different organs such as the liver, spleen, or the lymphatic

system. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia is more prevalent among children than in adults

(Stephen et al. 2015).

There are several classification systems, and since its inception in 1976, the French-

American- British (FAB) system has classified acute lymphoblastic leukaemia according to

morphology. This system considers information about sizes, cytoplasm, nucleus, basophilia, and

vacuolation, which is the investigation of the various geometrical, chromatic, and textural

elements of the cytoplasm and nuclei (Rawat et al. 2017). FAB classifies ALL into three sub-

types: L1, L2, and L3. According to Mandal (2019), about 31% to 84% of the adult and children

incidents of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia fall in the L1 category. Cells under this category

have regular shapes and with homogenous nuclear chromatins. Besides, they have scanty

cytoplasms, small nucleoli and moderate basophilia (Mandal 2019). The cells in sub-subtype L2

are large and have irregular nuclear shapes. The cells have prominent nucleoli and variable

basophilia. These cells are heterogeneous with variable nuclear chromatins (Terwilliger &

Abdul-Hay 2017). Finally, the cells in sub-type L3 are large and exhibit homogenous chromatin.

These cells have regular nuclei and basophilic cytoplasm. Notably, the distinctive element in

ALL-L3 type is the prominent cytoplasmic vacuolation (Terwilliger & Abdul-Hay 2017).

Question Two

The vital step in the diagnosis of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL) is the

examination of any physical signs. Hematologists ought to take blood samples from the affected

organs such as the swollen glands. The presence of numerous white blood cells is a hallmark for

ALL. Cooper and Brown (2015) assert that 34%-38% of children with ALL present a white

blood cell count of more than 20 x 10˄9/L. In this case, the 10-year old child whose WBC is 50

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 4

x 10 ˄9/L is likely to have acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Several confirmatory tests such as

bone marrow biopsy, cytogenic tests, molecular tests, peripheral smears, and flow cytometry can

be done to confirm this diagnosis.

The vital organ used for testing leukaemia is the bone marrow. Thus, marrow aspiration

and biopsy tests are essential tests in the diagnosis of ALL (Stephen et al. 2015). Both

procedures can be done at almost the same time. A syringe is used to suck the liquid from a

patient’s hip bone marrow when carrying out the bone marrow aspiration procedure. On the

other hand, the bone marrow biopsy procedure can be done after the aspiration procedure where

marrow is obtained for further diagnosis.

Cytochemistry can also be used to confirm the diagnosis for the 10-year old child. In this

test, cells are placed on slides that are then exposed to staining agents. Notably, the stains will

react with only specific leukaemia cells. For example, a dye may color the cells with acute

lymphoblastic leukaemia blue while leaving the unaffected cells intact. Under microscopy, the

stained cells can help hematologist-oncologists to define the type of leukaemia cells present in

the patient’s cell samples (Cooper & Brown 2015).

Cytogenetic tests will help in the diagnosis of the various sub-types of ALL. This test

involves the examination of whole chromosomes via karyotyping or hybridization of the cells in

situ. Normal chromosomes have 23 chromosome pairs, but in patients with ALL, their

chromosomes may have an abnormal number of chromosomes. The recognition of the numerical

change in chromosomes will help identify the three sub-types of ALL (Cooper & Brown 2015).

Equally important, it will be crucial in determining the child’s outlook and their response to

treatment. Cytogenetic testing helps identify chromosomal abnormalities; hence, the diagnosis

for leukaemia subtypes (L1, L2, and L3).

x 10 ˄9/L is likely to have acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Several confirmatory tests such as

bone marrow biopsy, cytogenic tests, molecular tests, peripheral smears, and flow cytometry can

be done to confirm this diagnosis.

The vital organ used for testing leukaemia is the bone marrow. Thus, marrow aspiration

and biopsy tests are essential tests in the diagnosis of ALL (Stephen et al. 2015). Both

procedures can be done at almost the same time. A syringe is used to suck the liquid from a

patient’s hip bone marrow when carrying out the bone marrow aspiration procedure. On the

other hand, the bone marrow biopsy procedure can be done after the aspiration procedure where

marrow is obtained for further diagnosis.

Cytochemistry can also be used to confirm the diagnosis for the 10-year old child. In this

test, cells are placed on slides that are then exposed to staining agents. Notably, the stains will

react with only specific leukaemia cells. For example, a dye may color the cells with acute

lymphoblastic leukaemia blue while leaving the unaffected cells intact. Under microscopy, the

stained cells can help hematologist-oncologists to define the type of leukaemia cells present in

the patient’s cell samples (Cooper & Brown 2015).

Cytogenetic tests will help in the diagnosis of the various sub-types of ALL. This test

involves the examination of whole chromosomes via karyotyping or hybridization of the cells in

situ. Normal chromosomes have 23 chromosome pairs, but in patients with ALL, their

chromosomes may have an abnormal number of chromosomes. The recognition of the numerical

change in chromosomes will help identify the three sub-types of ALL (Cooper & Brown 2015).

Equally important, it will be crucial in determining the child’s outlook and their response to

treatment. Cytogenetic testing helps identify chromosomal abnormalities; hence, the diagnosis

for leukaemia subtypes (L1, L2, and L3).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 5

Flow cytometry and immunophenotyping will help identify surface cell markers that will

be useful in the diagnosis of the different subtypes of leukaemia. Both procedures involve sorting

and counting of blood or bone marrow cells using particular cell surface markers.

Immunophenotyping classifies leukaemia in terms of proteins found within the sample cells

hence crucial in determining the specific type of blood disorder.

Finally, molecular tests and peripheral smears are useful in confirming the child’s

diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. In molecular testing, polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) is used to analyze the specific mutations in the DNA; hence, the diagnosis for the

different subtypes of ALL. Besides, the microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears will

help identify blast cells in ALL. A proper diagnosis will be useful in guiding the treatment as

well as in determining the prognosis of the acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

Section B

Question Three

The clotting cascade consists of enzyme activation systems where serine proteases

activate proteins through proteolysis. The outcome of the clotting pathway cascade is the

formation of blood clots through polymerization and activation of blood platelets. Blood clots act

as the barriers that prevent excessive bleeding after an injury. However, unnecessary blood clots

in the vessels can cause pathologic thrombosis. There are three pathways involved in the clotting

cascade: intrinsic, extrinsic and common pathways. The intrinsic (contact activation) and

extrinsic (tissue factor) pathways trigger blood clotting. Alternatively, the extrinsic pathway is

responsible for normal homeostasis.

Extrinsic/ Tissue Factor Pathway

Flow cytometry and immunophenotyping will help identify surface cell markers that will

be useful in the diagnosis of the different subtypes of leukaemia. Both procedures involve sorting

and counting of blood or bone marrow cells using particular cell surface markers.

Immunophenotyping classifies leukaemia in terms of proteins found within the sample cells

hence crucial in determining the specific type of blood disorder.

Finally, molecular tests and peripheral smears are useful in confirming the child’s

diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. In molecular testing, polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) is used to analyze the specific mutations in the DNA; hence, the diagnosis for the

different subtypes of ALL. Besides, the microscopic examination of peripheral blood smears will

help identify blast cells in ALL. A proper diagnosis will be useful in guiding the treatment as

well as in determining the prognosis of the acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

Section B

Question Three

The clotting cascade consists of enzyme activation systems where serine proteases

activate proteins through proteolysis. The outcome of the clotting pathway cascade is the

formation of blood clots through polymerization and activation of blood platelets. Blood clots act

as the barriers that prevent excessive bleeding after an injury. However, unnecessary blood clots

in the vessels can cause pathologic thrombosis. There are three pathways involved in the clotting

cascade: intrinsic, extrinsic and common pathways. The intrinsic (contact activation) and

extrinsic (tissue factor) pathways trigger blood clotting. Alternatively, the extrinsic pathway is

responsible for normal homeostasis.

Extrinsic/ Tissue Factor Pathway

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 6

The extrinsic pathway involves the activation of zymogens through proteolysis, and the

resultant active serine proteases activate other elements of the cascade. Trauma triggers the

initiation of the extrinsic pathway through the release of tissue factor VIIa. Enzymes that trigger

the extrinsic cascade consists of two subunits: fVIIa and TF. Tissue factors (TF) are the

glycosylated integral-membrane proteins that are abundant in blood vessels. TF: VIIa complex

anchors on cell-surface proteins and acts as potent coagulation activator (Smith, Travers &

Morrissey 2015). Through limited proteolysis, the TF: VIIa complex activates factor IX to factor

IXa. Factor X is then converted to factor Xa. Enzymes must anchor to membrane surfaces in

association with their respective fVIIIa and fVa co-factors to iniate the cascade (Morrissey et al.

2017). Prothrombin activator fXa triggers the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, which is

the protease enzyme that processes fibrinogen to fibrin, a clot. Notably, thrombin potently

activates platelets, which contribute to the formation of homeostatic plugs (Morrissey et al.

2017).

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) inhibits the TF: VIIa complex. A small

concentration of TFPI circulates in plasma as a more significant portion is present in the

microvascular endothelium. Platelet activation triggers the secretion of TFPI. TFPI regulates the

coagulation process by inhibiting factor Xa (Morrissey et al. 2017). Besides, factor Xa-

dependent feedback inhibition of the TF: VIIa regulates the clotting process. However,

thrombosis or consumptive coagulopathy may occur due to excessive coagulation of the tissue

factor pathway. Large formation of the TF: VIIa may lead to the loss of integrity in vascular

walls as well as the overexpression of tissue factors.

Contact/ Intrinsic Pathway

The extrinsic pathway involves the activation of zymogens through proteolysis, and the

resultant active serine proteases activate other elements of the cascade. Trauma triggers the

initiation of the extrinsic pathway through the release of tissue factor VIIa. Enzymes that trigger

the extrinsic cascade consists of two subunits: fVIIa and TF. Tissue factors (TF) are the

glycosylated integral-membrane proteins that are abundant in blood vessels. TF: VIIa complex

anchors on cell-surface proteins and acts as potent coagulation activator (Smith, Travers &

Morrissey 2015). Through limited proteolysis, the TF: VIIa complex activates factor IX to factor

IXa. Factor X is then converted to factor Xa. Enzymes must anchor to membrane surfaces in

association with their respective fVIIIa and fVa co-factors to iniate the cascade (Morrissey et al.

2017). Prothrombin activator fXa triggers the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, which is

the protease enzyme that processes fibrinogen to fibrin, a clot. Notably, thrombin potently

activates platelets, which contribute to the formation of homeostatic plugs (Morrissey et al.

2017).

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) inhibits the TF: VIIa complex. A small

concentration of TFPI circulates in plasma as a more significant portion is present in the

microvascular endothelium. Platelet activation triggers the secretion of TFPI. TFPI regulates the

coagulation process by inhibiting factor Xa (Morrissey et al. 2017). Besides, factor Xa-

dependent feedback inhibition of the TF: VIIa regulates the clotting process. However,

thrombosis or consumptive coagulopathy may occur due to excessive coagulation of the tissue

factor pathway. Large formation of the TF: VIIa may lead to the loss of integrity in vascular

walls as well as the overexpression of tissue factors.

Contact/ Intrinsic Pathway

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 7

The contact pathway uses kininogen and prekallikrein in the activation factor XIII. The

conformational change due to the association of blood with artificial surfaces activates factor

XIII to XIIIa that in turn activates prekallikrein to kallikrein (Wheeler & Gailani 2016).

Alternatively, kallikrein and fXIIa activate fXII and plasma prekallikrein respectively resulting

in a positive feedback loop. Also, factor XIIa is responsible for the activation of fXI to fXIa, that

in turn triggers the activation of fX to fXa (Wheeler & Gailani 2016). The product of the

common pathway is fibrin which is an insoluble protein.

On the contrary, the in vivo action of the common pathway results in the release of

bradykinin. Kallikrein cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen to produce the inflammatory

mediator, bradykinin. The binding of bradykinin to its B2 receptors results in vasodilation; hence

an increased vascular permeability (Wheeler & Gailani 2016). More also, the contact pathway

not only contributes to both fibrinolysis and angiogenesis but also to adhesive interactions.

The Common Pathway

The common pathway begins with the activation of factor X to factor Xa by tenase.

Factor Xa, then, activates factor II to factor IIa or thrombin (Smith, Travers & Morrissey 2015).

Notably, factor V acts as a cofactor for fXa in the conversion of prothrombin (factor II) to

thrombin. Subsequently, factor II activates fibrinogen to fibrin. Besides, thrombin activates fXI

and other cofactors (V, VIII and XIII). Platelet plugs are stabilized by fXIII. It is important to

note that thrombin is a positive regulator of the clotting cascade because it activates other factors

present in the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. As a regulator of the coagulation process,

thrombin cleaves protein C which is responsible for inactivating the upstream elements of the

cascade (Smith, Travers & Morrissey 2015). It is vital to note that the positive and negative

feedback systems are responsible for homeostatic processes after an injury.

The contact pathway uses kininogen and prekallikrein in the activation factor XIII. The

conformational change due to the association of blood with artificial surfaces activates factor

XIII to XIIIa that in turn activates prekallikrein to kallikrein (Wheeler & Gailani 2016).

Alternatively, kallikrein and fXIIa activate fXII and plasma prekallikrein respectively resulting

in a positive feedback loop. Also, factor XIIa is responsible for the activation of fXI to fXIa, that

in turn triggers the activation of fX to fXa (Wheeler & Gailani 2016). The product of the

common pathway is fibrin which is an insoluble protein.

On the contrary, the in vivo action of the common pathway results in the release of

bradykinin. Kallikrein cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen to produce the inflammatory

mediator, bradykinin. The binding of bradykinin to its B2 receptors results in vasodilation; hence

an increased vascular permeability (Wheeler & Gailani 2016). More also, the contact pathway

not only contributes to both fibrinolysis and angiogenesis but also to adhesive interactions.

The Common Pathway

The common pathway begins with the activation of factor X to factor Xa by tenase.

Factor Xa, then, activates factor II to factor IIa or thrombin (Smith, Travers & Morrissey 2015).

Notably, factor V acts as a cofactor for fXa in the conversion of prothrombin (factor II) to

thrombin. Subsequently, factor II activates fibrinogen to fibrin. Besides, thrombin activates fXI

and other cofactors (V, VIII and XIII). Platelet plugs are stabilized by fXIII. It is important to

note that thrombin is a positive regulator of the clotting cascade because it activates other factors

present in the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. As a regulator of the coagulation process,

thrombin cleaves protein C which is responsible for inactivating the upstream elements of the

cascade (Smith, Travers & Morrissey 2015). It is vital to note that the positive and negative

feedback systems are responsible for homeostatic processes after an injury.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 8

Question Four

Blood transfusions are life-saving and beneficial to patients. It is the intravenous

administration of blood from a donor to a recipient after bleeding. However, adverse reactions

may occur during transfusion due to immunological complications, infections or even errors that

may arise after the administration of incompatible blood. It is imperative that physicians inform

the patients of possible adverse reactions following blood transfusion. The patients ought to be

monitored from the onset of the process as most are at higher risks of transfusion reactions.

Transfusion reactions often occur after a blood transfusion, and it demands instant recognition,

laboratory investigations, and clinical management.

There are two categories of transfusion reactions: acute and delayed reactions. Acute

reactions ensue 24 hours after the onset of the transfusion procedure (Delaney et al. 2016). On

the contrary, delayed reactions may occur several days after the procedure. Septic reactions,

anaphylactic reactions, minor allergies, and haemolysis characterize acute transfusion responses.

On the other hand, transfusion-transmitted infections and alloimmunisation describe the delayed

transfusion reaction. The common signs that indicate a reaction include myalgia, nausea, fever,

breath shortness, hypertension, haemoglobinuria, respiratory distress and tachycardia (Murphy,

Roberts & Yazer 2017)

Once a transfusion reaction is reported to a laboratory, it is vital to stop the blood

transfusion, verify the patient’s identification, blood group, and donor units. It is crucial to

maintain venous access with normal saline while the patient is under investigation. In such

circumstances, a patient’s signs and symptoms ought to direct the treatment procedures. It is

essential that the hematologists examine the patient’s air passage, breathing rate, and blood

circulation. It is imperative to perform standard investigations and vital organ tests. In suspected

Question Four

Blood transfusions are life-saving and beneficial to patients. It is the intravenous

administration of blood from a donor to a recipient after bleeding. However, adverse reactions

may occur during transfusion due to immunological complications, infections or even errors that

may arise after the administration of incompatible blood. It is imperative that physicians inform

the patients of possible adverse reactions following blood transfusion. The patients ought to be

monitored from the onset of the process as most are at higher risks of transfusion reactions.

Transfusion reactions often occur after a blood transfusion, and it demands instant recognition,

laboratory investigations, and clinical management.

There are two categories of transfusion reactions: acute and delayed reactions. Acute

reactions ensue 24 hours after the onset of the transfusion procedure (Delaney et al. 2016). On

the contrary, delayed reactions may occur several days after the procedure. Septic reactions,

anaphylactic reactions, minor allergies, and haemolysis characterize acute transfusion responses.

On the other hand, transfusion-transmitted infections and alloimmunisation describe the delayed

transfusion reaction. The common signs that indicate a reaction include myalgia, nausea, fever,

breath shortness, hypertension, haemoglobinuria, respiratory distress and tachycardia (Murphy,

Roberts & Yazer 2017)

Once a transfusion reaction is reported to a laboratory, it is vital to stop the blood

transfusion, verify the patient’s identification, blood group, and donor units. It is crucial to

maintain venous access with normal saline while the patient is under investigation. In such

circumstances, a patient’s signs and symptoms ought to direct the treatment procedures. It is

essential that the hematologists examine the patient’s air passage, breathing rate, and blood

circulation. It is imperative to perform standard investigations and vital organ tests. In suspected

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 9

haemolytic instances, the patient’s transfusion blood and urine samples should be tested for

different elements such as clotting, crossmatch, and renal haemoglobinuria. According to

Murphy, Roberts, and Yazer (2017), air passage patency ought to be initiated once dyspnoea is

reported. Additionally, it is essential to assess the patient’s arterial/venous blood gases or central

venous pressure (Delaney et al. 2016). Moreover, it is imperative to place the patient in a

recumbent position in hypotensive situations.

Seek guidance where anaphylactic reactions are suspected. Investigations on anaphylactic

reactions require coagulated blood samples from the patient. Serum immunoglobulin levels and

mast cell tryptases would be critical for the investigation. If bacterial contamination or sepsis

infection is reported, send the patient’s blood cultures for analysis. According to Murphy,

Roberts, and Yazer (2017), bacterial contamination occurs due to insufficient sterile preparation

of phlebotomy sites.

Further, it may occur when opening the blood bottles in non-sterile conditions or when

bacteria are present in the donor’s blood circulatory system. It is crucial that investigations be

done with clerical checks in suspected blood transfusion reaction incidents. In other instances,

the examination may demand that samples be referred to other laboratories for more analysis.

Question Five

Since its inception in 1901, the ABO blood group system has been used to classify the

human blood by its genetic properties (Thomas & Weir 2018). The absence or presence of

antigens on the surfaces of erythrocytes characterize the ABO system. Individuals may have

blood type A, B, O, or AB. Blood that has type B antigen on its surface has antibodies against

type A in its serum. In this case, the intravenously administration of blood from a type A donor

haemolytic instances, the patient’s transfusion blood and urine samples should be tested for

different elements such as clotting, crossmatch, and renal haemoglobinuria. According to

Murphy, Roberts, and Yazer (2017), air passage patency ought to be initiated once dyspnoea is

reported. Additionally, it is essential to assess the patient’s arterial/venous blood gases or central

venous pressure (Delaney et al. 2016). Moreover, it is imperative to place the patient in a

recumbent position in hypotensive situations.

Seek guidance where anaphylactic reactions are suspected. Investigations on anaphylactic

reactions require coagulated blood samples from the patient. Serum immunoglobulin levels and

mast cell tryptases would be critical for the investigation. If bacterial contamination or sepsis

infection is reported, send the patient’s blood cultures for analysis. According to Murphy,

Roberts, and Yazer (2017), bacterial contamination occurs due to insufficient sterile preparation

of phlebotomy sites.

Further, it may occur when opening the blood bottles in non-sterile conditions or when

bacteria are present in the donor’s blood circulatory system. It is crucial that investigations be

done with clerical checks in suspected blood transfusion reaction incidents. In other instances,

the examination may demand that samples be referred to other laboratories for more analysis.

Question Five

Since its inception in 1901, the ABO blood group system has been used to classify the

human blood by its genetic properties (Thomas & Weir 2018). The absence or presence of

antigens on the surfaces of erythrocytes characterize the ABO system. Individuals may have

blood type A, B, O, or AB. Blood that has type B antigen on its surface has antibodies against

type A in its serum. In this case, the intravenously administration of blood from a type A donor

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 10

to a patient of blood group B may result in adverse reactions where the Anti-B antibodies destroy

the erythrocytes present in the patient’s blood (Thomas & Weir 2018).

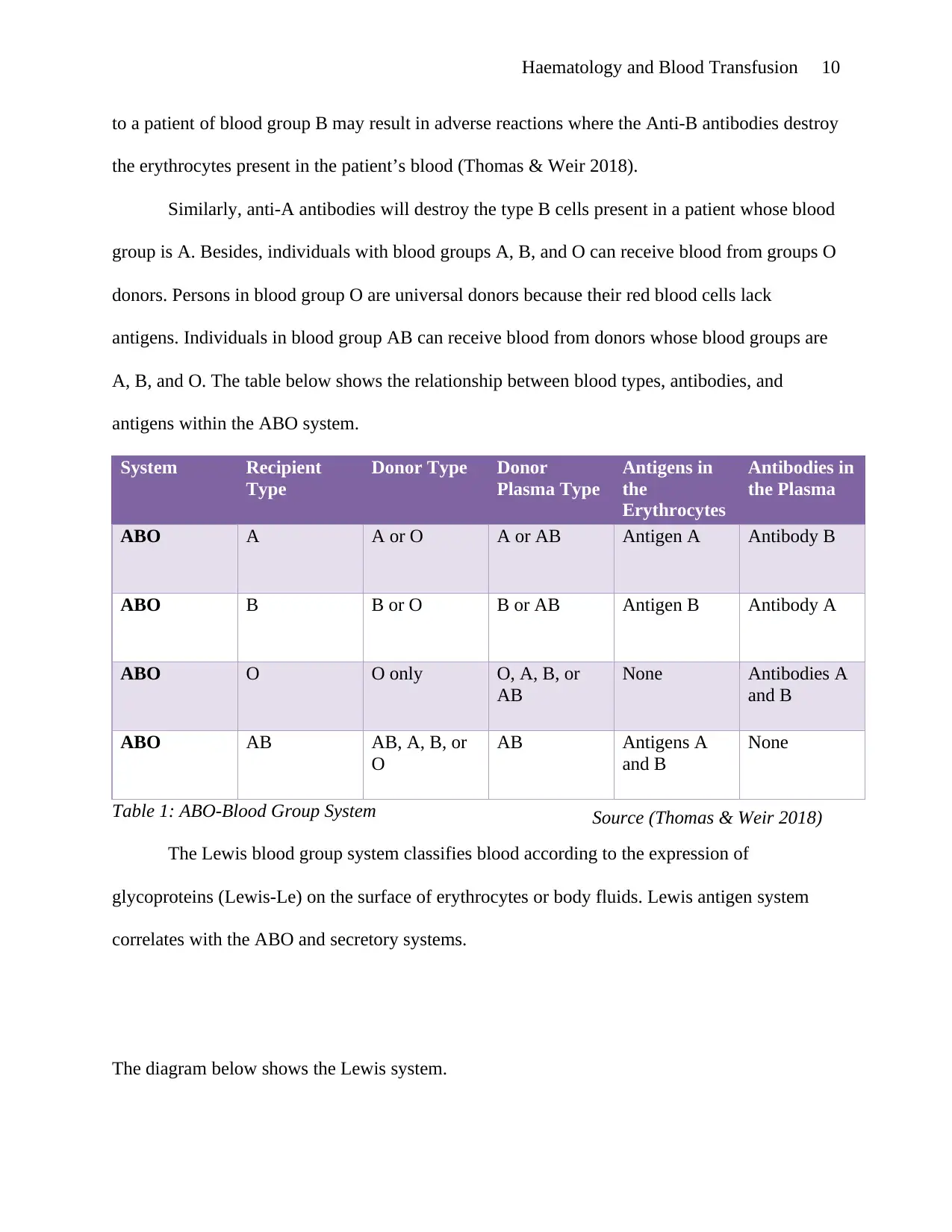

Similarly, anti-A antibodies will destroy the type B cells present in a patient whose blood

group is A. Besides, individuals with blood groups A, B, and O can receive blood from groups O

donors. Persons in blood group O are universal donors because their red blood cells lack

antigens. Individuals in blood group AB can receive blood from donors whose blood groups are

A, B, and O. The table below shows the relationship between blood types, antibodies, and

antigens within the ABO system.

System Recipient

Type

Donor Type Donor

Plasma Type

Antigens in

the

Erythrocytes

Antibodies in

the Plasma

ABO A A or O A or AB Antigen A Antibody B

ABO B B or O B or AB Antigen B Antibody A

ABO O O only O, A, B, or

AB

None Antibodies A

and B

ABO AB AB, A, B, or

O

AB Antigens A

and B

None

Table 1: ABO-Blood Group System

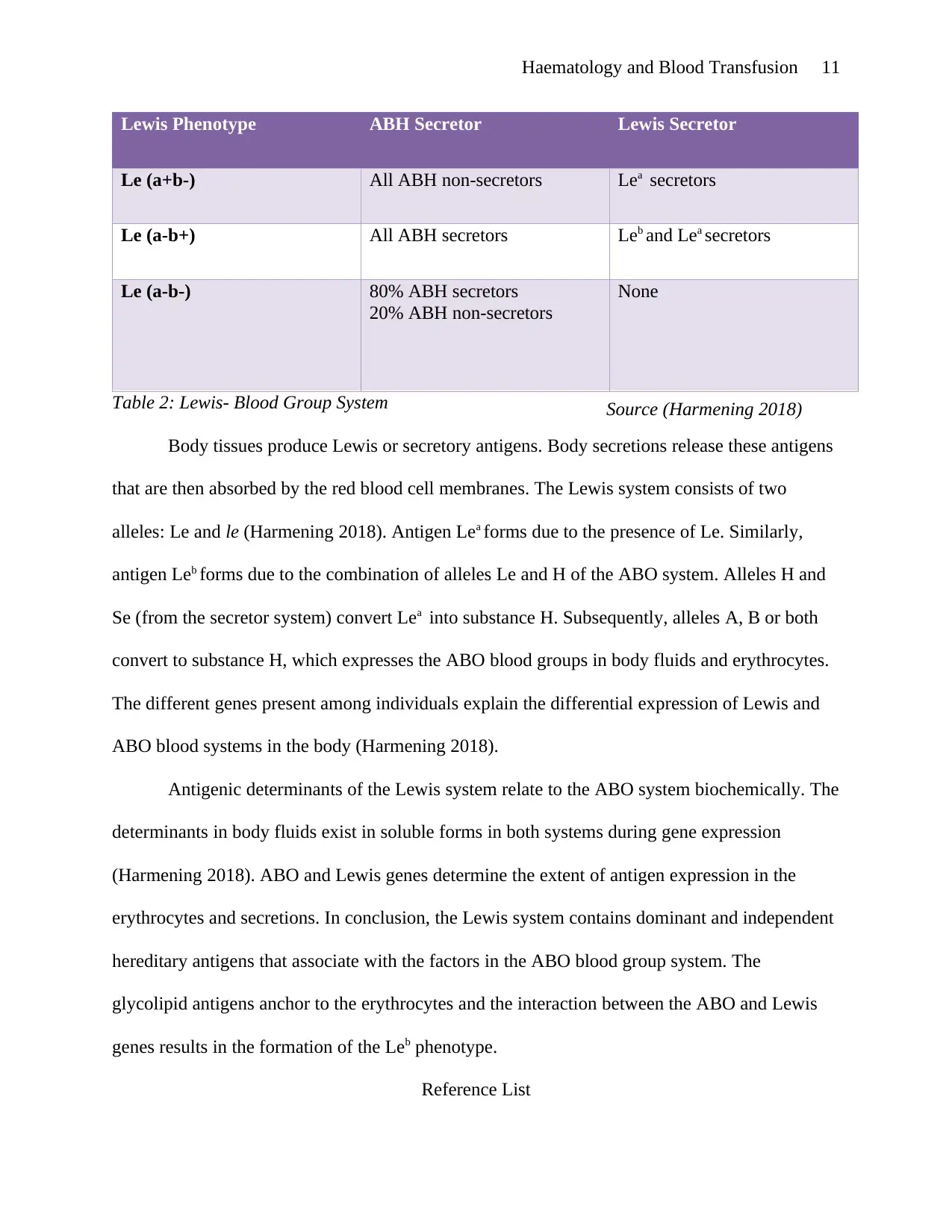

The Lewis blood group system classifies blood according to the expression of

glycoproteins (Lewis-Le) on the surface of erythrocytes or body fluids. Lewis antigen system

correlates with the ABO and secretory systems.

The diagram below shows the Lewis system.

Source (Thomas & Weir 2018)

to a patient of blood group B may result in adverse reactions where the Anti-B antibodies destroy

the erythrocytes present in the patient’s blood (Thomas & Weir 2018).

Similarly, anti-A antibodies will destroy the type B cells present in a patient whose blood

group is A. Besides, individuals with blood groups A, B, and O can receive blood from groups O

donors. Persons in blood group O are universal donors because their red blood cells lack

antigens. Individuals in blood group AB can receive blood from donors whose blood groups are

A, B, and O. The table below shows the relationship between blood types, antibodies, and

antigens within the ABO system.

System Recipient

Type

Donor Type Donor

Plasma Type

Antigens in

the

Erythrocytes

Antibodies in

the Plasma

ABO A A or O A or AB Antigen A Antibody B

ABO B B or O B or AB Antigen B Antibody A

ABO O O only O, A, B, or

AB

None Antibodies A

and B

ABO AB AB, A, B, or

O

AB Antigens A

and B

None

Table 1: ABO-Blood Group System

The Lewis blood group system classifies blood according to the expression of

glycoproteins (Lewis-Le) on the surface of erythrocytes or body fluids. Lewis antigen system

correlates with the ABO and secretory systems.

The diagram below shows the Lewis system.

Source (Thomas & Weir 2018)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 11

Lewis Phenotype ABH Secretor Lewis Secretor

Le (a+b-) All ABH non-secretors Lea secretors

Le (a-b+) All ABH secretors Leb and Lea secretors

Le (a-b-) 80% ABH secretors

20% ABH non-secretors

None

Table 2: Lewis- Blood Group System

Body tissues produce Lewis or secretory antigens. Body secretions release these antigens

that are then absorbed by the red blood cell membranes. The Lewis system consists of two

alleles: Le and le (Harmening 2018). Antigen Lea forms due to the presence of Le. Similarly,

antigen Leb forms due to the combination of alleles Le and H of the ABO system. Alleles H and

Se (from the secretor system) convert Lea into substance H. Subsequently, alleles A, B or both

convert to substance H, which expresses the ABO blood groups in body fluids and erythrocytes.

The different genes present among individuals explain the differential expression of Lewis and

ABO blood systems in the body (Harmening 2018).

Antigenic determinants of the Lewis system relate to the ABO system biochemically. The

determinants in body fluids exist in soluble forms in both systems during gene expression

(Harmening 2018). ABO and Lewis genes determine the extent of antigen expression in the

erythrocytes and secretions. In conclusion, the Lewis system contains dominant and independent

hereditary antigens that associate with the factors in the ABO blood group system. The

glycolipid antigens anchor to the erythrocytes and the interaction between the ABO and Lewis

genes results in the formation of the Leb phenotype.

Reference List

Source (Harmening 2018)

Lewis Phenotype ABH Secretor Lewis Secretor

Le (a+b-) All ABH non-secretors Lea secretors

Le (a-b+) All ABH secretors Leb and Lea secretors

Le (a-b-) 80% ABH secretors

20% ABH non-secretors

None

Table 2: Lewis- Blood Group System

Body tissues produce Lewis or secretory antigens. Body secretions release these antigens

that are then absorbed by the red blood cell membranes. The Lewis system consists of two

alleles: Le and le (Harmening 2018). Antigen Lea forms due to the presence of Le. Similarly,

antigen Leb forms due to the combination of alleles Le and H of the ABO system. Alleles H and

Se (from the secretor system) convert Lea into substance H. Subsequently, alleles A, B or both

convert to substance H, which expresses the ABO blood groups in body fluids and erythrocytes.

The different genes present among individuals explain the differential expression of Lewis and

ABO blood systems in the body (Harmening 2018).

Antigenic determinants of the Lewis system relate to the ABO system biochemically. The

determinants in body fluids exist in soluble forms in both systems during gene expression

(Harmening 2018). ABO and Lewis genes determine the extent of antigen expression in the

erythrocytes and secretions. In conclusion, the Lewis system contains dominant and independent

hereditary antigens that associate with the factors in the ABO blood group system. The

glycolipid antigens anchor to the erythrocytes and the interaction between the ABO and Lewis

genes results in the formation of the Leb phenotype.

Reference List

Source (Harmening 2018)

Haematology and Blood Transfusion 12

Cooper, S.L. and Brown, P.A., 2015. Treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

Pediatric Clinics, 62(1), pp. 61-73.

Crane, G.M., Jeffery, E. and Morrison, S.J., 2017. Adult haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nature

Reviews Immunology , 17(9), p. 573.

Delaney, M., Wendel, S., Bercovitz, R.S., Cid, J., Cohn, C., Dunbar, N.M., Apelseth, T.O.,

Popovsky, M., Stanworth, S.J., Tinmouth, A. and Van De Watering, L., 2016.

Transfusion reactions: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. The Lancet, 388(10061), pp.

2825-2836.

Harmening, D.M., 2018. Modern blood banking & transfusion practices. FA Davis

Mandal, A., 2019. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Classification. viewed 1 April 2019,

https://www.news-medical.net/health/Acute-Lymphoblastic-Leukemia-

Classification.aspx

Morrissey, J.H., Smith, S.A., Docampo, R. and Mutch, N.J., 2017. Coagulation and fibrinolytic

cascades modulator. U.S. Patent 9,597,375.

Murphy, M.F., Roberts, D.J. and Yazer, M.H. eds., 2017. Practical transfusion medicine. John

Wiley & Sons.

Rawat, J., Singh, A., Bhadauria, H.S., Virmani, J. and Devgun, J.S., 2017. Classification of acute

lymphoblastic leukaemia using hybrid hierarchical classifiers. Multimedia Tools and

Applications, 76(18), pp. 19057-19085.

Smith, S.A., Travers, J.R. and Morrissey, H. J., 2015. How it all starts: Initiation of the clotting

cascade. Critical reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 50(4), pp. 326-336.

Stephen, P., Hunger, M.D., Charles, G. and Mullinghan, M.D., 2015. Acute lyphoblastic

leukaemia in children. The New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 373, pp. 1541-

Cooper, S.L. and Brown, P.A., 2015. Treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

Pediatric Clinics, 62(1), pp. 61-73.

Crane, G.M., Jeffery, E. and Morrison, S.J., 2017. Adult haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nature

Reviews Immunology , 17(9), p. 573.

Delaney, M., Wendel, S., Bercovitz, R.S., Cid, J., Cohn, C., Dunbar, N.M., Apelseth, T.O.,

Popovsky, M., Stanworth, S.J., Tinmouth, A. and Van De Watering, L., 2016.

Transfusion reactions: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. The Lancet, 388(10061), pp.

2825-2836.

Harmening, D.M., 2018. Modern blood banking & transfusion practices. FA Davis

Mandal, A., 2019. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Classification. viewed 1 April 2019,

https://www.news-medical.net/health/Acute-Lymphoblastic-Leukemia-

Classification.aspx

Morrissey, J.H., Smith, S.A., Docampo, R. and Mutch, N.J., 2017. Coagulation and fibrinolytic

cascades modulator. U.S. Patent 9,597,375.

Murphy, M.F., Roberts, D.J. and Yazer, M.H. eds., 2017. Practical transfusion medicine. John

Wiley & Sons.

Rawat, J., Singh, A., Bhadauria, H.S., Virmani, J. and Devgun, J.S., 2017. Classification of acute

lymphoblastic leukaemia using hybrid hierarchical classifiers. Multimedia Tools and

Applications, 76(18), pp. 19057-19085.

Smith, S.A., Travers, J.R. and Morrissey, H. J., 2015. How it all starts: Initiation of the clotting

cascade. Critical reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 50(4), pp. 326-336.

Stephen, P., Hunger, M.D., Charles, G. and Mullinghan, M.D., 2015. Acute lyphoblastic

leukaemia in children. The New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 373, pp. 1541-

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 13

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.