Healthcare Systems: Australia and South Africa Comparison Report

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/08

|14

|3369

|280

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comparative analysis of the healthcare systems in Australia and South Africa, addressing key aspects such as financing mechanisms, the role of the private sector, and the populations facing limited access to healthcare services. The report explores the financing systems in both countries, highlighting the contributions towards universal healthcare, including the involvement of public and private funding. It also examines the role of the private sector in both systems, including the availability of private health insurance and its impact on healthcare access and delivery. Furthermore, the report identifies population groups with restricted access to healthcare in both Australia and South Africa, along with the barriers they face, such as geographical limitations, financial constraints, and socioeconomic disparities. The analysis draws on data and insights from various sources, including government reports, academic literature, and healthcare organizations, to provide a comprehensive overview of the healthcare landscapes in both countries. The report is structured to address the specific questions outlined in the HEAL6010 assignment brief, offering a detailed comparison and contrast of the two healthcare systems.

Running head: ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

Organisation of Healthcare Systems

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Author note

Organisation of Healthcare Systems

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Author note

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

Question 1

Financing system of Australia and the contribution towards the universal healthcare

To understand the funding system of healthcare in Australia the involvement of public

and government funding in healthcare and associated system have to be identified to examine

their contribution towards the Universal healthcare system. In Australia, the governing

system of universal healthcare comprises three levels of government: federal and state,

territorial and local government. The federal government offers financial supports and several

indirect supports along with the healthcare professionals. The federal government also

subsidises primary care providers under the process of Medicare Benefits Scheme or MBS

and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme or PBS (Aihw.gov.au. 2016). The federal

government also provides funding for state healthcare services. In direct service delivery it

only has a limited role. On the other hand, the chief responsibility of the of the State

government are associated with the public hospitals, ambulance services, dental services,

public health and mental health services. In addition to the funding provided by the federal

government, the state government has to also contribute their own funding for these

healthcare services in state level (Morgan, Leopold and Wagner 2017).

In Australian financial system for healthcare, for providing the Community health

services such as vaccines and food-standard regulation as well preventive health programs,

the local governments plays a major role. According to annual report of 2014-2015, total

health spending in local and state level on healthcare and related services was 10.0% of GDP,

which is a 2.8% boost from the annual expenditure of 2013–2014. The government has

funded the 67% of the total expenditure of the health system (Schmidt, Gostin and Emanuel,

2015). In this regards it has to be mentioned that the visitors of Australia cannot access the

general Medicare system. Medicare is partially financed by a particular taxation system under

Question 1

Financing system of Australia and the contribution towards the universal healthcare

To understand the funding system of healthcare in Australia the involvement of public

and government funding in healthcare and associated system have to be identified to examine

their contribution towards the Universal healthcare system. In Australia, the governing

system of universal healthcare comprises three levels of government: federal and state,

territorial and local government. The federal government offers financial supports and several

indirect supports along with the healthcare professionals. The federal government also

subsidises primary care providers under the process of Medicare Benefits Scheme or MBS

and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme or PBS (Aihw.gov.au. 2016). The federal

government also provides funding for state healthcare services. In direct service delivery it

only has a limited role. On the other hand, the chief responsibility of the of the State

government are associated with the public hospitals, ambulance services, dental services,

public health and mental health services. In addition to the funding provided by the federal

government, the state government has to also contribute their own funding for these

healthcare services in state level (Morgan, Leopold and Wagner 2017).

In Australian financial system for healthcare, for providing the Community health

services such as vaccines and food-standard regulation as well preventive health programs,

the local governments plays a major role. According to annual report of 2014-2015, total

health spending in local and state level on healthcare and related services was 10.0% of GDP,

which is a 2.8% boost from the annual expenditure of 2013–2014. The government has

funded the 67% of the total expenditure of the health system (Schmidt, Gostin and Emanuel,

2015). In this regards it has to be mentioned that the visitors of Australia cannot access the

general Medicare system. Medicare is partially financed by a particular taxation system under

2ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

the control of government. In the 2013–2014 fiscal year the funding in Medicare system

raised up to AUD 10.3 trillion (Stigler et al. 2016). The fund was further expanded in July

2014 to improve the financial capability for the disability care system. Public policies

encourage PHI enrolment with a tax discount and, over and above some income, a penalty

payment for not having PHI (Medicare Levy supplement).

Financing system of Africa and the contribution towards the universal healthcare

In South Africa, a combination of private and public funding system is used for

providing the financial support to national level healthcare system. The financial contribution

of this mixed funding mechanism can be clearly seen in the reported funding of the year

2005, where the funding from general tax allocation was around 40%, whereas around 45%

of the total health care funding was from private healthcare scheme and around 14% from

out-of-pocket payments (Rao et al. 2014). It is critical that households finance healthcare

according to their ability to pay and if risk is pooled to improve their prepayment for

healthcare in this context. Accordingly, universal coverage requires considerable social

solidarity, often enshrined in African cultures. Solidarity enables the rich (income cross-

subsidies), and the healthy (risk cross-subsidies) to cross-subsidize the poor. Like many other

developing countries, South Africa coexists in both private and public health. In comparison

with the public system, the private healthcare system currently accounts for the largest

portion, including both medical and private out - of-pocket payments, of all funding for

healthcare (Fusheini and Eyles 2016).

The highest total per capita level of health care expenditure is found in Africa in South Africa

(i.e. from public and private sources). This means, after the Commission on macroeconomics

and the estimates on health resource requirements from the Commission, that there is a

relatively sufficient amount of health care per capita to provide everyone with more than a

the control of government. In the 2013–2014 fiscal year the funding in Medicare system

raised up to AUD 10.3 trillion (Stigler et al. 2016). The fund was further expanded in July

2014 to improve the financial capability for the disability care system. Public policies

encourage PHI enrolment with a tax discount and, over and above some income, a penalty

payment for not having PHI (Medicare Levy supplement).

Financing system of Africa and the contribution towards the universal healthcare

In South Africa, a combination of private and public funding system is used for

providing the financial support to national level healthcare system. The financial contribution

of this mixed funding mechanism can be clearly seen in the reported funding of the year

2005, where the funding from general tax allocation was around 40%, whereas around 45%

of the total health care funding was from private healthcare scheme and around 14% from

out-of-pocket payments (Rao et al. 2014). It is critical that households finance healthcare

according to their ability to pay and if risk is pooled to improve their prepayment for

healthcare in this context. Accordingly, universal coverage requires considerable social

solidarity, often enshrined in African cultures. Solidarity enables the rich (income cross-

subsidies), and the healthy (risk cross-subsidies) to cross-subsidize the poor. Like many other

developing countries, South Africa coexists in both private and public health. In comparison

with the public system, the private healthcare system currently accounts for the largest

portion, including both medical and private out - of-pocket payments, of all funding for

healthcare (Fusheini and Eyles 2016).

The highest total per capita level of health care expenditure is found in Africa in South Africa

(i.e. from public and private sources). This means, after the Commission on macroeconomics

and the estimates on health resource requirements from the Commission, that there is a

relatively sufficient amount of health care per capita to provide everyone with more than a

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

basic level of care. In the field of health policy, the NHI proposal by ANC has generated

considerable debate among key health stakeholders and academics. It is anticipated that the

proposed scheme would pool its funds into one single unit or NHIF. However, the budget

share in the health sector has declined from approximately 11.5% in 2000/2001 to about

10.9% in 2007/2008, as opposed to the Abuja declaration by the African Heads of State in

2001 that requires countries to allocate to the health sector up to 15% of the overall budget in

the Government (Fusheini and Eyles 2016).

Question 2

Role of the private sector in both Australian healthcare systems

The PHI is readily available and provides more options for providers (mainly

hospitals), faster access to non-emergency services, and discounts on the services selected.

The Lifetime Health Coverage program is a reduction in the premium for life when

participants sign up before the age of 31 (Jakovljevic, Groot and Souliotis 2016). The

government policy encourages PHI registration by tax discounts or by penalty, in excess of

certain incomes. PHI does not have a Medicare levy charge. There is a 2% increase in

baseline premiums for people who do not sign up after 30 years of age each year. As a result,

the absorption of 30 people is higher and below but rapidly decreases with age, with an opt-

out trend starting at 50 years. Almost half of the people in Australia (47%) have private

hospital coverage and almost 56% in 2016 received general treatment. Insurers are a

combination of profits and non-profits (Mayosi and Benatar 2014). Private health expenses

accounted for 8.7% of all health expenditures in 2014–2015. Private health insurance may

include hospital, general or ambulance treatment coverage. Private health insurance

providing a more flexible range of suppliers (especially in hospitals), speedier access to non-

emergency services and discounts on selected services is now readily available. Nearly half

basic level of care. In the field of health policy, the NHI proposal by ANC has generated

considerable debate among key health stakeholders and academics. It is anticipated that the

proposed scheme would pool its funds into one single unit or NHIF. However, the budget

share in the health sector has declined from approximately 11.5% in 2000/2001 to about

10.9% in 2007/2008, as opposed to the Abuja declaration by the African Heads of State in

2001 that requires countries to allocate to the health sector up to 15% of the overall budget in

the Government (Fusheini and Eyles 2016).

Question 2

Role of the private sector in both Australian healthcare systems

The PHI is readily available and provides more options for providers (mainly

hospitals), faster access to non-emergency services, and discounts on the services selected.

The Lifetime Health Coverage program is a reduction in the premium for life when

participants sign up before the age of 31 (Jakovljevic, Groot and Souliotis 2016). The

government policy encourages PHI registration by tax discounts or by penalty, in excess of

certain incomes. PHI does not have a Medicare levy charge. There is a 2% increase in

baseline premiums for people who do not sign up after 30 years of age each year. As a result,

the absorption of 30 people is higher and below but rapidly decreases with age, with an opt-

out trend starting at 50 years. Almost half of the people in Australia (47%) have private

hospital coverage and almost 56% in 2016 received general treatment. Insurers are a

combination of profits and non-profits (Mayosi and Benatar 2014). Private health expenses

accounted for 8.7% of all health expenditures in 2014–2015. Private health insurance may

include hospital, general or ambulance treatment coverage. Private health insurance

providing a more flexible range of suppliers (especially in hospitals), speedier access to non-

emergency services and discounts on selected services is now readily available. Nearly half

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

of the Australian population (47%) had private hospital coverage and nearly 56 percent had

general treatment coverage in 2016 (Asante et al. 2016).

Patients can opt for treatment with full fees (with full fee coverage) as a public patient

or a private patient (with 75% fee coverage) when accessing hospital services. Insurance

covers MBS fees for private patients (Hall 2015). The consumer will bear the costs of the

difference, if a provider charges above the MBS fee, unless it has gaps. Costs for hospital

accommodation, operational fees (implants and theater fees) and diagnostic trials can also be

charged to the patient. The coverage includes dental, physiotherapy, chiropractic, podiatry,

home nursing and optometry insurance. The amount or number of services covered may be

limited by dollars. The socio-economic status of private health insurance varies. PHI only

includes one out of five (22,1%) of the poorest 20% of the population, up to more than 57,2%

for the most advantaged quintile population (Asante et al. 2016). This difference is partly due

to the surcharge for higher-income payers from Medicare levies.

Role of the private sector in both African healthcare systems

The national health minister once again said at a press conference on South Africa's

National Health Insurance that private health care only serves 16 percent of the population.

About 18% of the population in South Africa belong to medical schemes that give them

privacy. In 1997 there were 161, in 2004 there were 200. The number of private hospitals is

rapidly increasing. Netcare, with approximately 43 hospitals and 18 day clinics in the whole

of South Africa, and Medi-clinic (www.netcare.co.za), with around 53 hospitals, are two of

the leading private healthcare providers. In 2012, private health care providers provided

primary health care services for 28 percent, an estimated 38 percent of the South African

people, due to the relative extent of this demand and the resulting growth and development in

of the Australian population (47%) had private hospital coverage and nearly 56 percent had

general treatment coverage in 2016 (Asante et al. 2016).

Patients can opt for treatment with full fees (with full fee coverage) as a public patient

or a private patient (with 75% fee coverage) when accessing hospital services. Insurance

covers MBS fees for private patients (Hall 2015). The consumer will bear the costs of the

difference, if a provider charges above the MBS fee, unless it has gaps. Costs for hospital

accommodation, operational fees (implants and theater fees) and diagnostic trials can also be

charged to the patient. The coverage includes dental, physiotherapy, chiropractic, podiatry,

home nursing and optometry insurance. The amount or number of services covered may be

limited by dollars. The socio-economic status of private health insurance varies. PHI only

includes one out of five (22,1%) of the poorest 20% of the population, up to more than 57,2%

for the most advantaged quintile population (Asante et al. 2016). This difference is partly due

to the surcharge for higher-income payers from Medicare levies.

Role of the private sector in both African healthcare systems

The national health minister once again said at a press conference on South Africa's

National Health Insurance that private health care only serves 16 percent of the population.

About 18% of the population in South Africa belong to medical schemes that give them

privacy. In 1997 there were 161, in 2004 there were 200. The number of private hospitals is

rapidly increasing. Netcare, with approximately 43 hospitals and 18 day clinics in the whole

of South Africa, and Medi-clinic (www.netcare.co.za), with around 53 hospitals, are two of

the leading private healthcare providers. In 2012, private health care providers provided

primary health care services for 28 percent, an estimated 38 percent of the South African

people, due to the relative extent of this demand and the resulting growth and development in

5ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

the sector. In addition, an estimated 37% of GPs, 59% of experts and 38% of nurses were

involved in the private sector in South Africa (Mayosi, and Benatar 2014).

It is further estimated that in 2013 the private health services sector accounted for

35% of hospitals and 28% of hospital beds. Between 2007/08 and 2011/12 the average health

outlay in South Africa was 50% and 3%, respectively, for the public, private and donor sector

and NGOs. All of these figures show the size and importance of private healthcare in

accessing quality treatment in South Africa (Jakovljevic, Groot and Souliotis 2016). On the

Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), the 3 largest private hospital groups are listed and have

a significant effect on local investment and taxation.

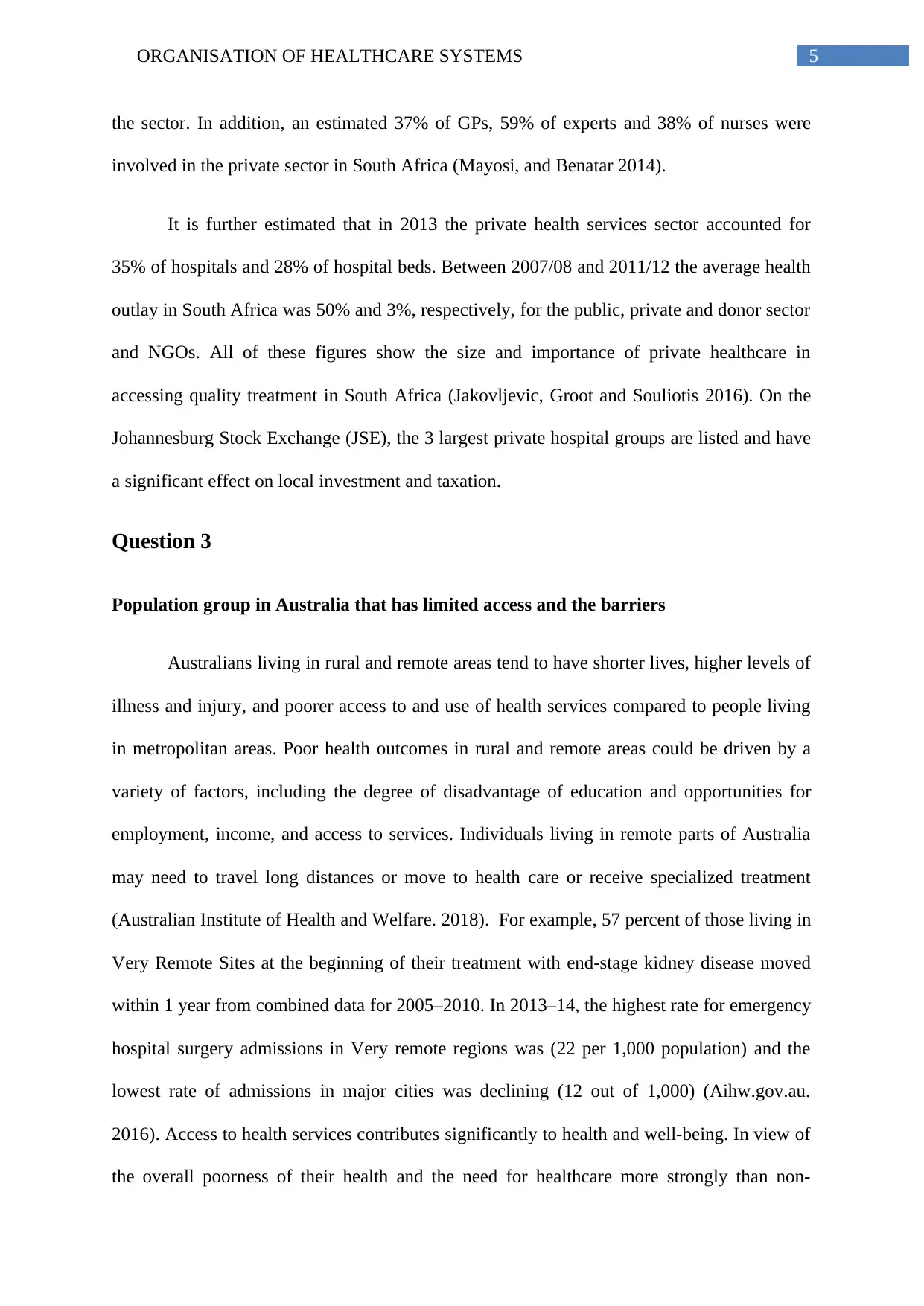

Question 3

Population group in Australia that has limited access and the barriers

Australians living in rural and remote areas tend to have shorter lives, higher levels of

illness and injury, and poorer access to and use of health services compared to people living

in metropolitan areas. Poor health outcomes in rural and remote areas could be driven by a

variety of factors, including the degree of disadvantage of education and opportunities for

employment, income, and access to services. Individuals living in remote parts of Australia

may need to travel long distances or move to health care or receive specialized treatment

(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018). For example, 57 percent of those living in

Very Remote Sites at the beginning of their treatment with end-stage kidney disease moved

within 1 year from combined data for 2005–2010. In 2013–14, the highest rate for emergency

hospital surgery admissions in Very remote regions was (22 per 1,000 population) and the

lowest rate of admissions in major cities was declining (12 out of 1,000) (Aihw.gov.au.

2016). Access to health services contributes significantly to health and well-being. In view of

the overall poorness of their health and the need for healthcare more strongly than non-

the sector. In addition, an estimated 37% of GPs, 59% of experts and 38% of nurses were

involved in the private sector in South Africa (Mayosi, and Benatar 2014).

It is further estimated that in 2013 the private health services sector accounted for

35% of hospitals and 28% of hospital beds. Between 2007/08 and 2011/12 the average health

outlay in South Africa was 50% and 3%, respectively, for the public, private and donor sector

and NGOs. All of these figures show the size and importance of private healthcare in

accessing quality treatment in South Africa (Jakovljevic, Groot and Souliotis 2016). On the

Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), the 3 largest private hospital groups are listed and have

a significant effect on local investment and taxation.

Question 3

Population group in Australia that has limited access and the barriers

Australians living in rural and remote areas tend to have shorter lives, higher levels of

illness and injury, and poorer access to and use of health services compared to people living

in metropolitan areas. Poor health outcomes in rural and remote areas could be driven by a

variety of factors, including the degree of disadvantage of education and opportunities for

employment, income, and access to services. Individuals living in remote parts of Australia

may need to travel long distances or move to health care or receive specialized treatment

(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018). For example, 57 percent of those living in

Very Remote Sites at the beginning of their treatment with end-stage kidney disease moved

within 1 year from combined data for 2005–2010. In 2013–14, the highest rate for emergency

hospital surgery admissions in Very remote regions was (22 per 1,000 population) and the

lowest rate of admissions in major cities was declining (12 out of 1,000) (Aihw.gov.au.

2016). Access to health services contributes significantly to health and well-being. In view of

the overall poorness of their health and the need for healthcare more strongly than non-

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

indigenous populations, it influences particularly the health status of indigenous and Torres

Strait Islanders. Around 203 indigenous primary healthcare organizations reported data on the

total number of their clients, contacts and care episodes in 2014–15. Services were provided

by more than 5 million contacts to 434,600 clients, with a mean of 12 customers per person

(Aihw.gov.au. 2016). Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders are over three-quarters (79 %)

of those clients. Over time, health care episodes have almost tripled to customers in these

organizations, from 1.2 million in 1999–2000 to 3.5 million in 2014-15 (AIHW 2016b)

(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018). GP services were 10 per cent more than

that for non-Indigenous Australians per 1,000 Indigenous Australians, but the claims for

specialist services for indigenous Australians were 43 per cent less.

Population group in Africa that has limited access and the barriers

In South Africa, access to healthcare is constitutionally enshrined in South Africa;

however considerable inequity still exists, mainly due to distortions in the allocation of

resources. Over one thousand people, mainly in LMICs, are unable to access the needed

healthcare services. They are inexpensive. The barriers to access include large distances and

high travel costs in rural areas in particular; high out - of-pocket (OOP) care payment; long

queues; and disabled patients. The hurdles of access experienced elsewhere in LMIC's

resonate with uneven social power relations (Mayosi and Benatar 2014). The achievement of

a fair UHC requires accessible, necessary services(' dependence') for the whole population('

breadth'), while adapting the disadvantaged groups to' different needs' and financial

constraints(' height'). The differences in health outcomes from racial and socio-economic to

rural and urban to private sectors are still challenging. There were 21 159 of the 4668

households sampled. Four-fifths were black Africans, almost half had primary or minor

education, and 39.9% were rural (Crush and Tawodzera 2014).

indigenous populations, it influences particularly the health status of indigenous and Torres

Strait Islanders. Around 203 indigenous primary healthcare organizations reported data on the

total number of their clients, contacts and care episodes in 2014–15. Services were provided

by more than 5 million contacts to 434,600 clients, with a mean of 12 customers per person

(Aihw.gov.au. 2016). Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders are over three-quarters (79 %)

of those clients. Over time, health care episodes have almost tripled to customers in these

organizations, from 1.2 million in 1999–2000 to 3.5 million in 2014-15 (AIHW 2016b)

(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018). GP services were 10 per cent more than

that for non-Indigenous Australians per 1,000 Indigenous Australians, but the claims for

specialist services for indigenous Australians were 43 per cent less.

Population group in Africa that has limited access and the barriers

In South Africa, access to healthcare is constitutionally enshrined in South Africa;

however considerable inequity still exists, mainly due to distortions in the allocation of

resources. Over one thousand people, mainly in LMICs, are unable to access the needed

healthcare services. They are inexpensive. The barriers to access include large distances and

high travel costs in rural areas in particular; high out - of-pocket (OOP) care payment; long

queues; and disabled patients. The hurdles of access experienced elsewhere in LMIC's

resonate with uneven social power relations (Mayosi and Benatar 2014). The achievement of

a fair UHC requires accessible, necessary services(' dependence') for the whole population('

breadth'), while adapting the disadvantaged groups to' different needs' and financial

constraints(' height'). The differences in health outcomes from racial and socio-economic to

rural and urban to private sectors are still challenging. There were 21 159 of the 4668

households sampled. Four-fifths were black Africans, almost half had primary or minor

education, and 39.9% were rural (Crush and Tawodzera 2014).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

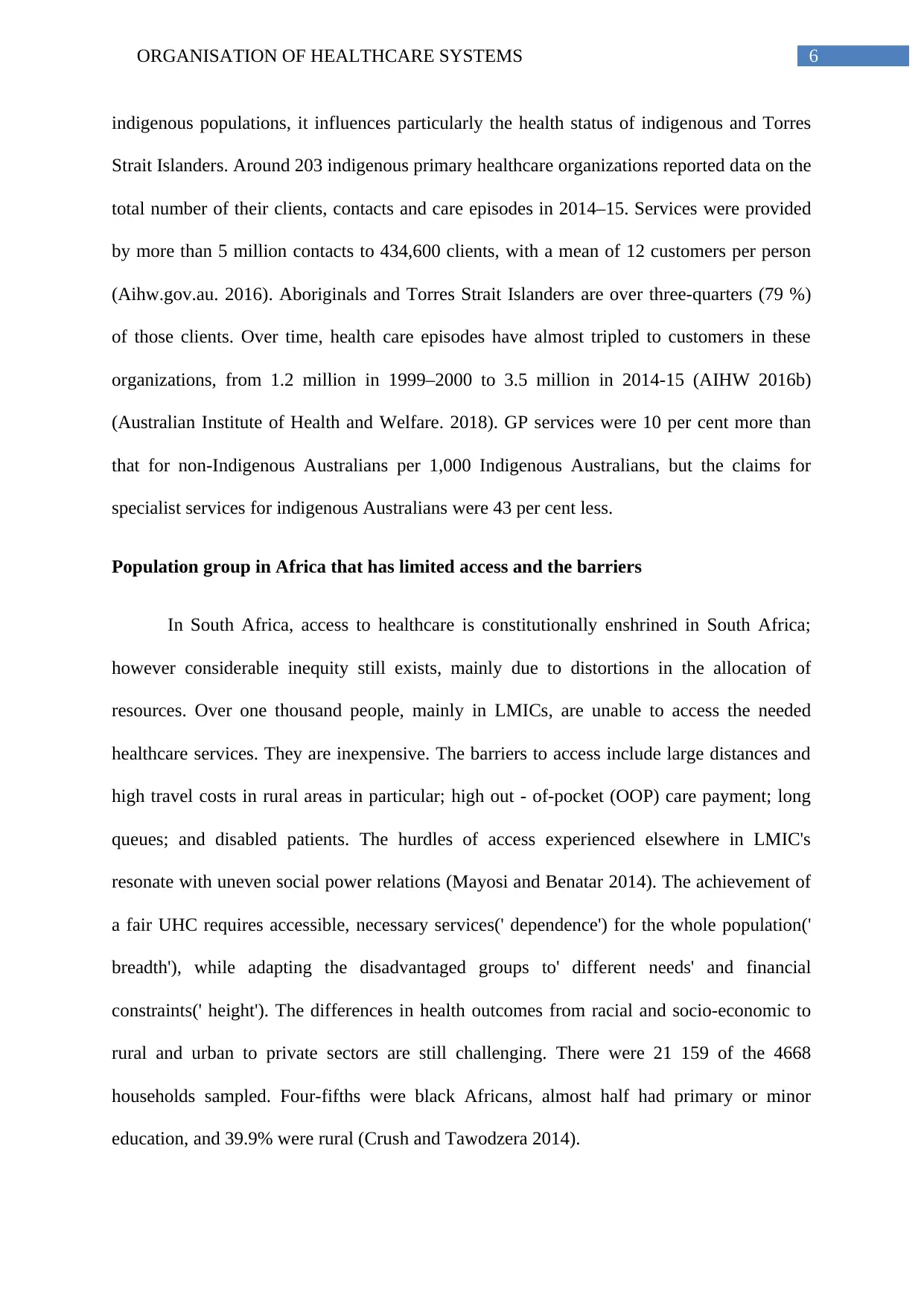

The richer quintiles concentrated surgical visits in the private sector. Private

outpatient care (including general practitioners, private dentists and pharmacies) has been

steadily increasing in consumption, from 15.7% to 60.8% of the wealthy; a group which also

used outpatients in private hospitals four times more than in private hospitals. The total

utilization of hospital-private facilities for rural residents and those living in informal urban

areas was only 10% (33,6 admissions) (van Rensburg 2014). Private admissions in the more

poor, rural provinces of Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and Eastern Cape also produced widespread

differences.

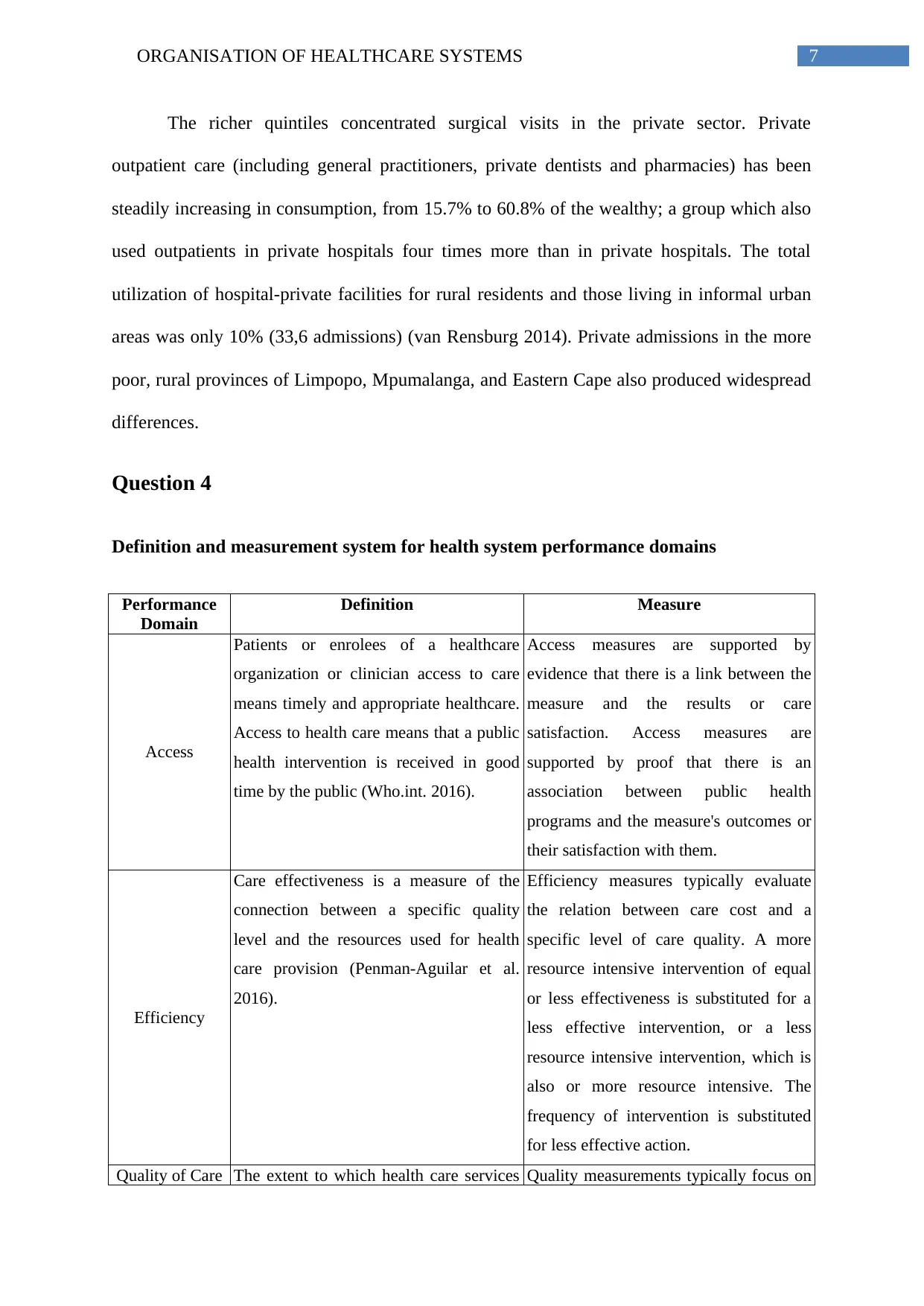

Question 4

Definition and measurement system for health system performance domains

Performance

Domain

Definition Measure

Access

Patients or enrolees of a healthcare

organization or clinician access to care

means timely and appropriate healthcare.

Access to health care means that a public

health intervention is received in good

time by the public (Who.int. 2016).

Access measures are supported by

evidence that there is a link between the

measure and the results or care

satisfaction. Access measures are

supported by proof that there is an

association between public health

programs and the measure's outcomes or

their satisfaction with them.

Efficiency

Care effectiveness is a measure of the

connection between a specific quality

level and the resources used for health

care provision (Penman-Aguilar et al.

2016).

Efficiency measures typically evaluate

the relation between care cost and a

specific level of care quality. A more

resource intensive intervention of equal

or less effectiveness is substituted for a

less effective intervention, or a less

resource intensive intervention, which is

also or more resource intensive. The

frequency of intervention is substituted

for less effective action.

Quality of Care The extent to which health care services Quality measurements typically focus on

The richer quintiles concentrated surgical visits in the private sector. Private

outpatient care (including general practitioners, private dentists and pharmacies) has been

steadily increasing in consumption, from 15.7% to 60.8% of the wealthy; a group which also

used outpatients in private hospitals four times more than in private hospitals. The total

utilization of hospital-private facilities for rural residents and those living in informal urban

areas was only 10% (33,6 admissions) (van Rensburg 2014). Private admissions in the more

poor, rural provinces of Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and Eastern Cape also produced widespread

differences.

Question 4

Definition and measurement system for health system performance domains

Performance

Domain

Definition Measure

Access

Patients or enrolees of a healthcare

organization or clinician access to care

means timely and appropriate healthcare.

Access to health care means that a public

health intervention is received in good

time by the public (Who.int. 2016).

Access measures are supported by

evidence that there is a link between the

measure and the results or care

satisfaction. Access measures are

supported by proof that there is an

association between public health

programs and the measure's outcomes or

their satisfaction with them.

Efficiency

Care effectiveness is a measure of the

connection between a specific quality

level and the resources used for health

care provision (Penman-Aguilar et al.

2016).

Efficiency measures typically evaluate

the relation between care cost and a

specific level of care quality. A more

resource intensive intervention of equal

or less effectiveness is substituted for a

less effective intervention, or a less

resource intensive intervention, which is

also or more resource intensive. The

frequency of intervention is substituted

for less effective action.

Quality of Care The extent to which health care services Quality measurements typically focus on

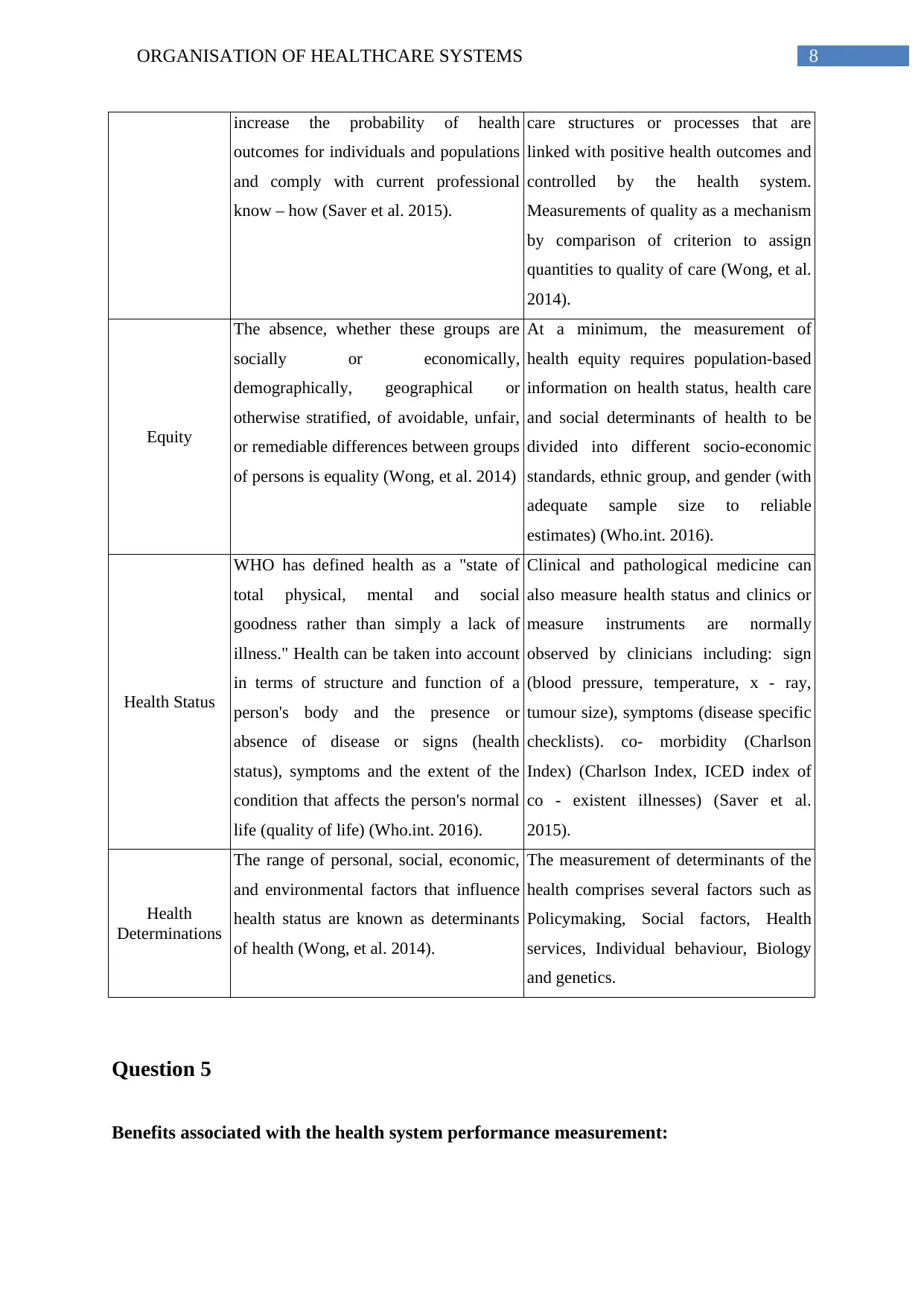

8ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

increase the probability of health

outcomes for individuals and populations

and comply with current professional

know – how (Saver et al. 2015).

care structures or processes that are

linked with positive health outcomes and

controlled by the health system.

Measurements of quality as a mechanism

by comparison of criterion to assign

quantities to quality of care (Wong, et al.

2014).

Equity

The absence, whether these groups are

socially or economically,

demographically, geographical or

otherwise stratified, of avoidable, unfair,

or remediable differences between groups

of persons is equality (Wong, et al. 2014)

At a minimum, the measurement of

health equity requires population-based

information on health status, health care

and social determinants of health to be

divided into different socio-economic

standards, ethnic group, and gender (with

adequate sample size to reliable

estimates) (Who.int. 2016).

Health Status

WHO has defined health as a "state of

total physical, mental and social

goodness rather than simply a lack of

illness." Health can be taken into account

in terms of structure and function of a

person's body and the presence or

absence of disease or signs (health

status), symptoms and the extent of the

condition that affects the person's normal

life (quality of life) (Who.int. 2016).

Clinical and pathological medicine can

also measure health status and clinics or

measure instruments are normally

observed by clinicians including: sign

(blood pressure, temperature, x - ray,

tumour size), symptoms (disease specific

checklists). co- morbidity (Charlson

Index) (Charlson Index, ICED index of

co - existent illnesses) (Saver et al.

2015).

Health

Determinations

The range of personal, social, economic,

and environmental factors that influence

health status are known as determinants

of health (Wong, et al. 2014).

The measurement of determinants of the

health comprises several factors such as

Policymaking, Social factors, Health

services, Individual behaviour, Biology

and genetics.

Question 5

Benefits associated with the health system performance measurement:

increase the probability of health

outcomes for individuals and populations

and comply with current professional

know – how (Saver et al. 2015).

care structures or processes that are

linked with positive health outcomes and

controlled by the health system.

Measurements of quality as a mechanism

by comparison of criterion to assign

quantities to quality of care (Wong, et al.

2014).

Equity

The absence, whether these groups are

socially or economically,

demographically, geographical or

otherwise stratified, of avoidable, unfair,

or remediable differences between groups

of persons is equality (Wong, et al. 2014)

At a minimum, the measurement of

health equity requires population-based

information on health status, health care

and social determinants of health to be

divided into different socio-economic

standards, ethnic group, and gender (with

adequate sample size to reliable

estimates) (Who.int. 2016).

Health Status

WHO has defined health as a "state of

total physical, mental and social

goodness rather than simply a lack of

illness." Health can be taken into account

in terms of structure and function of a

person's body and the presence or

absence of disease or signs (health

status), symptoms and the extent of the

condition that affects the person's normal

life (quality of life) (Who.int. 2016).

Clinical and pathological medicine can

also measure health status and clinics or

measure instruments are normally

observed by clinicians including: sign

(blood pressure, temperature, x - ray,

tumour size), symptoms (disease specific

checklists). co- morbidity (Charlson

Index) (Charlson Index, ICED index of

co - existent illnesses) (Saver et al.

2015).

Health

Determinations

The range of personal, social, economic,

and environmental factors that influence

health status are known as determinants

of health (Wong, et al. 2014).

The measurement of determinants of the

health comprises several factors such as

Policymaking, Social factors, Health

services, Individual behaviour, Biology

and genetics.

Question 5

Benefits associated with the health system performance measurement:

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

The healthcare system performance measurement can offer a broad assessment of

system performance as well as can also stimulate better data collection and analytic

efforts across health systems and nations.

The healthcare system performance measurement enables the authority to place the

healthcare system performance measurement at the centre of the governmental policy

where policy-makers at all levels can have the freedom to concentrate on areas where

improvements are most readily secured, in contrast to piecemeal performance

indicators (Wong, et al. 2014).

The healthcare system performance measurement offers a clear indication which

systems represent the best overall performance and improvement efforts. As a result,

it enables more accurate and effective judgement and cross-national comparison in

order to improve the health system efficiency

Challenges associated with health system performance measurement:

One of the major limitation of health system performance measurement is that it May

disguise failings in specific parts of the health care system, which can lead to making

individual measures under a contentious and hidden dataset while statistically

calculating the aggregation of the obtained data. Sometimes the performance

measurement ignores some aspects of performance that are difficult to measure,

leading to adverse behavioural effects (Penman-Aguilar et al. 2016).

The health system performance measurement can make the whole measurement

system difficult to determine where poor performance is occurring and, consequently,

may make policy and planning more difficult and less effective.

The healthcare system performance measurement can offer a broad assessment of

system performance as well as can also stimulate better data collection and analytic

efforts across health systems and nations.

The healthcare system performance measurement enables the authority to place the

healthcare system performance measurement at the centre of the governmental policy

where policy-makers at all levels can have the freedom to concentrate on areas where

improvements are most readily secured, in contrast to piecemeal performance

indicators (Wong, et al. 2014).

The healthcare system performance measurement offers a clear indication which

systems represent the best overall performance and improvement efforts. As a result,

it enables more accurate and effective judgement and cross-national comparison in

order to improve the health system efficiency

Challenges associated with health system performance measurement:

One of the major limitation of health system performance measurement is that it May

disguise failings in specific parts of the health care system, which can lead to making

individual measures under a contentious and hidden dataset while statistically

calculating the aggregation of the obtained data. Sometimes the performance

measurement ignores some aspects of performance that are difficult to measure,

leading to adverse behavioural effects (Penman-Aguilar et al. 2016).

The health system performance measurement can make the whole measurement

system difficult to determine where poor performance is occurring and, consequently,

may make policy and planning more difficult and less effective.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

Health system performance measurement often can lead to double counting, because

of high positive correlation May use feeble data when seeking to cover many areas,

which may make the methodological soundness of the entire indicator questionable.

As a result, sometime it only reflects certain preferences when inadequately

developed methods for applying weights to composite indicators are used.

Health system performance measurement often can lead to double counting, because

of high positive correlation May use feeble data when seeking to cover many areas,

which may make the methodological soundness of the entire indicator questionable.

As a result, sometime it only reflects certain preferences when inadequately

developed methods for applying weights to composite indicators are used.

11ORGANISATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

Reference

Aihw.gov.au. 2016. how-does-australias-health-system-work. [online] Available at:

https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/f2ae1191-bbf2-47b6-a9d4-1b2ca65553a1/ah16-2-1-how-

does-australias-health-system-work.pdf.aspx [Accessed 8 Apr. 2019].

Aihw.gov.au. 2016. Indigenous Australians’ access to health services. [online] Available at:

https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/01d88043-31ba-424a-a682-98673783072e/ah16-6-6-

indigenous-australians-access-health-services.pdf.aspx [Accessed 8 Apr. 2019].

Asante, A., Price, J., Hayen, A., Jan, S. and Wiseman, V., 2016. Equity in health care

financing in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of evidence from studies

using benefit and financing incidence analyses. PloS one, 11(4), p.e0152866.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018. Rural & remote health, Access to health

services - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. [online] Available at:

https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-health/rural-remote-health/contents/access-to-health-

services [Accessed 8 Apr. 2019].

Crush, J. and Tawodzera, G., 2014. Medical xenophobia and Zimbabwean migrant access to

public health services in South Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(4),

pp.655-670.

Fusheini, A. and Eyles, J., 2016. Achieving universal health coverage in South Africa

through a district health system approach: conflicting ideologies of health care

provision. BMC health services research, 16(1), p.558.

Gauld, R., Burgers, J., Dobrow, M., Minhas, R., Wendt, C., B. Cohen, A. and Luxford, K.,

2014. Healthcare system performance improvement: a comparison of key policies in seven

high-income countries. Journal of health organization and management, 28(1), pp.2-20.

Reference

Aihw.gov.au. 2016. how-does-australias-health-system-work. [online] Available at:

https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/f2ae1191-bbf2-47b6-a9d4-1b2ca65553a1/ah16-2-1-how-

does-australias-health-system-work.pdf.aspx [Accessed 8 Apr. 2019].

Aihw.gov.au. 2016. Indigenous Australians’ access to health services. [online] Available at:

https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/01d88043-31ba-424a-a682-98673783072e/ah16-6-6-

indigenous-australians-access-health-services.pdf.aspx [Accessed 8 Apr. 2019].

Asante, A., Price, J., Hayen, A., Jan, S. and Wiseman, V., 2016. Equity in health care

financing in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of evidence from studies

using benefit and financing incidence analyses. PloS one, 11(4), p.e0152866.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018. Rural & remote health, Access to health

services - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. [online] Available at:

https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-health/rural-remote-health/contents/access-to-health-

services [Accessed 8 Apr. 2019].

Crush, J. and Tawodzera, G., 2014. Medical xenophobia and Zimbabwean migrant access to

public health services in South Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(4),

pp.655-670.

Fusheini, A. and Eyles, J., 2016. Achieving universal health coverage in South Africa

through a district health system approach: conflicting ideologies of health care

provision. BMC health services research, 16(1), p.558.

Gauld, R., Burgers, J., Dobrow, M., Minhas, R., Wendt, C., B. Cohen, A. and Luxford, K.,

2014. Healthcare system performance improvement: a comparison of key policies in seven

high-income countries. Journal of health organization and management, 28(1), pp.2-20.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 14

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.