Systematic Review: Enhancing Medication Adherence in Heart Failure

VerifiedAdded on 2023/06/13

|9

|7032

|229

Literature Review

AI Summary

This systematic review examines interventions designed to improve medication adherence in patients with heart failure (CHF). The review included randomized controlled trials that assessed the impact of various strategies on medication adherence, measured through methods such as pill counts, electronic monitoring, and self-reported data. The study selection process involved searching databases like MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, and PsychInfo, resulting in the identification of 16 independent studies with a total of 3305 patients. Interventions ranged from simplifying medication regimens and patient education to healthcare provider monitoring and motivational techniques. The review assesses the risk of bias in included studies, focusing on selection, performance, attrition, and detection biases. While data pooling was not possible due to heterogeneity, the review provides a comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of different adherence-enhancing interventions in CHF.

Advances in Heart Failure

Interventions to Enhance Adherence to Medications in

Patients With Heart Failure

A Systematic Review

Gerard J. Molloy, BSc, PhD; Ronan E. O’Carroll, BSc, PhD;

Miles D. Witham, BM, BCh, PhD, MRCP; Marion E.T. McMurdo, BM, BCh, FRCP, CBiol, FIBiol

Prognosis remains poor for patients with chronic heart

failure (CHF), despite improvements in the prevention

and treatment of heart failure over the last 25 years. Recent

estimates indicate that the median survival after a first

episode of heart failure is 2.3 years for men and 1.8 years for

women. 1 It is suggested that the improvements in outcomes

that have been achieved can be partly explained by increases

in prescribing rates of medications such as angiotensin-

converting enzyme inhibitors, 2 -blockers, 3 and spironolac-

tone 4 over this period. 1 Although the evidence on medication

efficacy for certain subgroups of patients with CHF is clear,

there are also compelling data showing that many of these

patients do not take their medications as prescribed by health

care providers. 5,6 This “nonadherence” to medication there-

fore remains a significant barrier to enhancing the effective-

ness of existing treatments.

Estimates for nonadherence to medications in CHF have

varied widely.5 One of the largest studies found that only 80%

of patients with a prescription for angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitors at hospital discharge completed the pre-

scription form 30 days after discharge, and this rate subse-

quently fell to 60% over 1 year. 7 Full adherence, defined as

filing enough prescriptions to have daily medication available

for 1 year, may be as low as 10% in CHF. 8 Poor adherence to

medication in CHF is associated with worse outcomes in

observational studies, including shorter event-free survival. 9

Therefore, strategies to enhance adherence provide a poten-

tially valuable strategy for improving survival, reducing

hospitalization and managing patient symptoms in CHF.

In this report, we provide an up-to-date review and analysis

of those studies that have developed and evaluated medica-

tion adherence interventions in CHF. Because CHF is typi-

cally symptomatic and includes medication with actions that

are discernible to the patient within hours of ingestion, for

example, diuretics and consequent diuresis, an examination

of interventions for this population in isolation from cardio-

vascular disease populations more generally is warranted

because some CVD patient populations can have asymptom-

atic conditions, for example, hypertension or hyperlipidemia

and medication regimens with little or no side effects. 10

Previous reviews 11 may have also set inclusion criteria that

may be too stringent for CHF populations, in which high

morbidity and mortality rates can make attrition rates for

medication adherence outcome measures appear abnormally

high over 1 year even in high-quality studies, for example,

⬎80% participant follow-up and ⬎6 month follow-up inclu-

sion criteria. 11 Therefore, potentially useful studies may have

been overlooked in previous reviews. The objective of this

systematic review was to identify and summarize the effec-

tiveness of intervention strategies to enhance adherence to

medications in heart failure populations.

Study Selection

The following inclusion criteria were used to identify appro-

priate published studies for the review:

(1) The study design was a randomized, controlled trial in

which an intervention group was compared with treat-

ment as usual or a clearly justified comparison group.

(2) The population of interest comprised adults (⬎18

years old) with a diagnosis of heart failure confirmed

by a physician.

(3) The intervention strategy clearly had a primary or

secondary aim to increase adherence to medication

prescribed for heart failure.

(4) Self-administered medication, that is, medication not

administered by a health care professional, was mea-

sured as an outcome by any of the following methods:

pill count, electronic monitoring, refill or prescription

records, and self-reported data.

A trial was included if it met all our inclusion criteria.

Reference Manager (version 11) software was used to iden-

tify and extract duplicate studies.

Literature Search

We performed a systematic review, using guidelines devel-

oped by the Cochrane Collaboration. The databases of the

Received August 24, 2011; accepted November 17, 2011.

From the Division of Psychology (G.J.M., R.E.O.), School of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland; and Ninewells Hospital and

Medical School (M.D.W., M.E.T.M.), Section of Ageing and Health, University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland.

Correspondence to Gerard J. Molloy, BSc, PhD, Division of Psychology, School of Natural Sciences, Cottrell Bldg, University of Stirling, FK9 4LA,

Scotland. E-mail g.j.molloy@stir.ac.uk

(Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:126-133.)

© 2012 American Heart Association, Inc.

Circ Heart Fail is available at http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964569

126

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

Interventions to Enhance Adherence to Medications in

Patients With Heart Failure

A Systematic Review

Gerard J. Molloy, BSc, PhD; Ronan E. O’Carroll, BSc, PhD;

Miles D. Witham, BM, BCh, PhD, MRCP; Marion E.T. McMurdo, BM, BCh, FRCP, CBiol, FIBiol

Prognosis remains poor for patients with chronic heart

failure (CHF), despite improvements in the prevention

and treatment of heart failure over the last 25 years. Recent

estimates indicate that the median survival after a first

episode of heart failure is 2.3 years for men and 1.8 years for

women. 1 It is suggested that the improvements in outcomes

that have been achieved can be partly explained by increases

in prescribing rates of medications such as angiotensin-

converting enzyme inhibitors, 2 -blockers, 3 and spironolac-

tone 4 over this period. 1 Although the evidence on medication

efficacy for certain subgroups of patients with CHF is clear,

there are also compelling data showing that many of these

patients do not take their medications as prescribed by health

care providers. 5,6 This “nonadherence” to medication there-

fore remains a significant barrier to enhancing the effective-

ness of existing treatments.

Estimates for nonadherence to medications in CHF have

varied widely.5 One of the largest studies found that only 80%

of patients with a prescription for angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitors at hospital discharge completed the pre-

scription form 30 days after discharge, and this rate subse-

quently fell to 60% over 1 year. 7 Full adherence, defined as

filing enough prescriptions to have daily medication available

for 1 year, may be as low as 10% in CHF. 8 Poor adherence to

medication in CHF is associated with worse outcomes in

observational studies, including shorter event-free survival. 9

Therefore, strategies to enhance adherence provide a poten-

tially valuable strategy for improving survival, reducing

hospitalization and managing patient symptoms in CHF.

In this report, we provide an up-to-date review and analysis

of those studies that have developed and evaluated medica-

tion adherence interventions in CHF. Because CHF is typi-

cally symptomatic and includes medication with actions that

are discernible to the patient within hours of ingestion, for

example, diuretics and consequent diuresis, an examination

of interventions for this population in isolation from cardio-

vascular disease populations more generally is warranted

because some CVD patient populations can have asymptom-

atic conditions, for example, hypertension or hyperlipidemia

and medication regimens with little or no side effects. 10

Previous reviews 11 may have also set inclusion criteria that

may be too stringent for CHF populations, in which high

morbidity and mortality rates can make attrition rates for

medication adherence outcome measures appear abnormally

high over 1 year even in high-quality studies, for example,

⬎80% participant follow-up and ⬎6 month follow-up inclu-

sion criteria. 11 Therefore, potentially useful studies may have

been overlooked in previous reviews. The objective of this

systematic review was to identify and summarize the effec-

tiveness of intervention strategies to enhance adherence to

medications in heart failure populations.

Study Selection

The following inclusion criteria were used to identify appro-

priate published studies for the review:

(1) The study design was a randomized, controlled trial in

which an intervention group was compared with treat-

ment as usual or a clearly justified comparison group.

(2) The population of interest comprised adults (⬎18

years old) with a diagnosis of heart failure confirmed

by a physician.

(3) The intervention strategy clearly had a primary or

secondary aim to increase adherence to medication

prescribed for heart failure.

(4) Self-administered medication, that is, medication not

administered by a health care professional, was mea-

sured as an outcome by any of the following methods:

pill count, electronic monitoring, refill or prescription

records, and self-reported data.

A trial was included if it met all our inclusion criteria.

Reference Manager (version 11) software was used to iden-

tify and extract duplicate studies.

Literature Search

We performed a systematic review, using guidelines devel-

oped by the Cochrane Collaboration. The databases of the

Received August 24, 2011; accepted November 17, 2011.

From the Division of Psychology (G.J.M., R.E.O.), School of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, Scotland; and Ninewells Hospital and

Medical School (M.D.W., M.E.T.M.), Section of Ageing and Health, University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland.

Correspondence to Gerard J. Molloy, BSc, PhD, Division of Psychology, School of Natural Sciences, Cottrell Bldg, University of Stirling, FK9 4LA,

Scotland. E-mail g.j.molloy@stir.ac.uk

(Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:126-133.)

© 2012 American Heart Association, Inc.

Circ Heart Fail is available at http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964569

126

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE,

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

(CINAHL), Embase, and PsychInfo were searched for full

published reports to the end of December 2010. All databases

were searched from their start date. The search strategy

incorporated relevant terms from recent Cochrane Reviews

on adherence to medication 11,12 and heart failure, 13 and a

highly sensitive search strategy developed by the Cochrane

group for maximizing the identification of randomized trials

was also applied in Medline. 14 The reference lists of all

selected articles and relevant review articles were also

searched for additional studies. Only studies/abstracts in

English were included because translation services were not

available to the authors for this review.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted from selected studies with the use of a

predefined form. Data were extracted by Dr Molloy. Risk of

bias was assessed independently by Drs Molloy and

O’Carroll, and discrepancies were resolved by discussing the

discrepant judgments. Details of information extracted are

provided in Tables 1 and 2. Study authors were contacted for

additional information.

Quality Assessment

As recommended by the Cochrane Reviewers Handbook, 14

we assessed study quality according to 4 main sources of

potential bias in the identified studies: (1) selection bias, (2)

performance bias, (3) attrition bias, and (4) and detection

bias. To do this, studies were assessed for adequate sequence

generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), the

presence of blinding in outcome assessment (performance

and detection bias), and whether reporting of losses to

follow-up and intention-to-treat analysis were specified (at-

trition bias). Selective reporting bias was not assessed be-

cause few studies had published protocols before completing

and reporting their studies, making assessing this aspect of

bias difficult in most cases. The overall quality assessment for

each study was summarized by using a risk-of-bias summary

figure, based on Cochrane review recommendations. 14

Analysis

Pooling of the data was not possible because of the hetero-

geneity of measurement and analysis between studies. We

grouped studies according to the main components included

in the interventions. This was based on categories specified in

a recent systematic review of interventions to enhance adher-

ence to lipid-lowering medication. 12

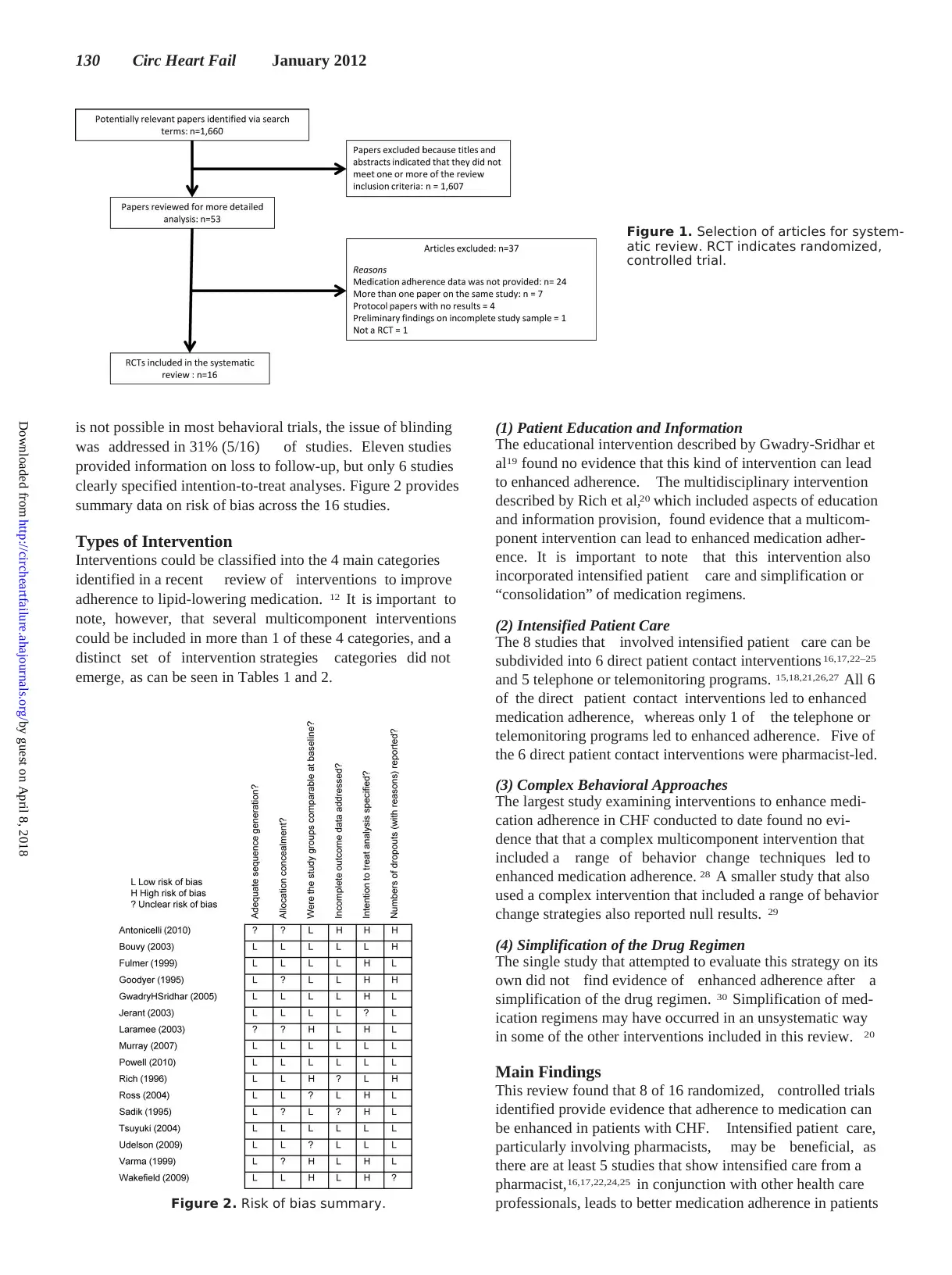

Selection of Trials

In total, the search strategies identified 1660 records (after

removal of duplicate records) of potential relevance from

searches of all 5 electronic databases (Figure 1). An inspec-

tion of study titles and the study abstracts revealed that more

than 95% of these did not meet the review inclusion criteria.

Fifty-three studies were retained for closer inspection, and

only 16 independent studies derived from these studies met

all the review inclusion criteria. The flow of studies through

the selection process is summarized in Figure 1.

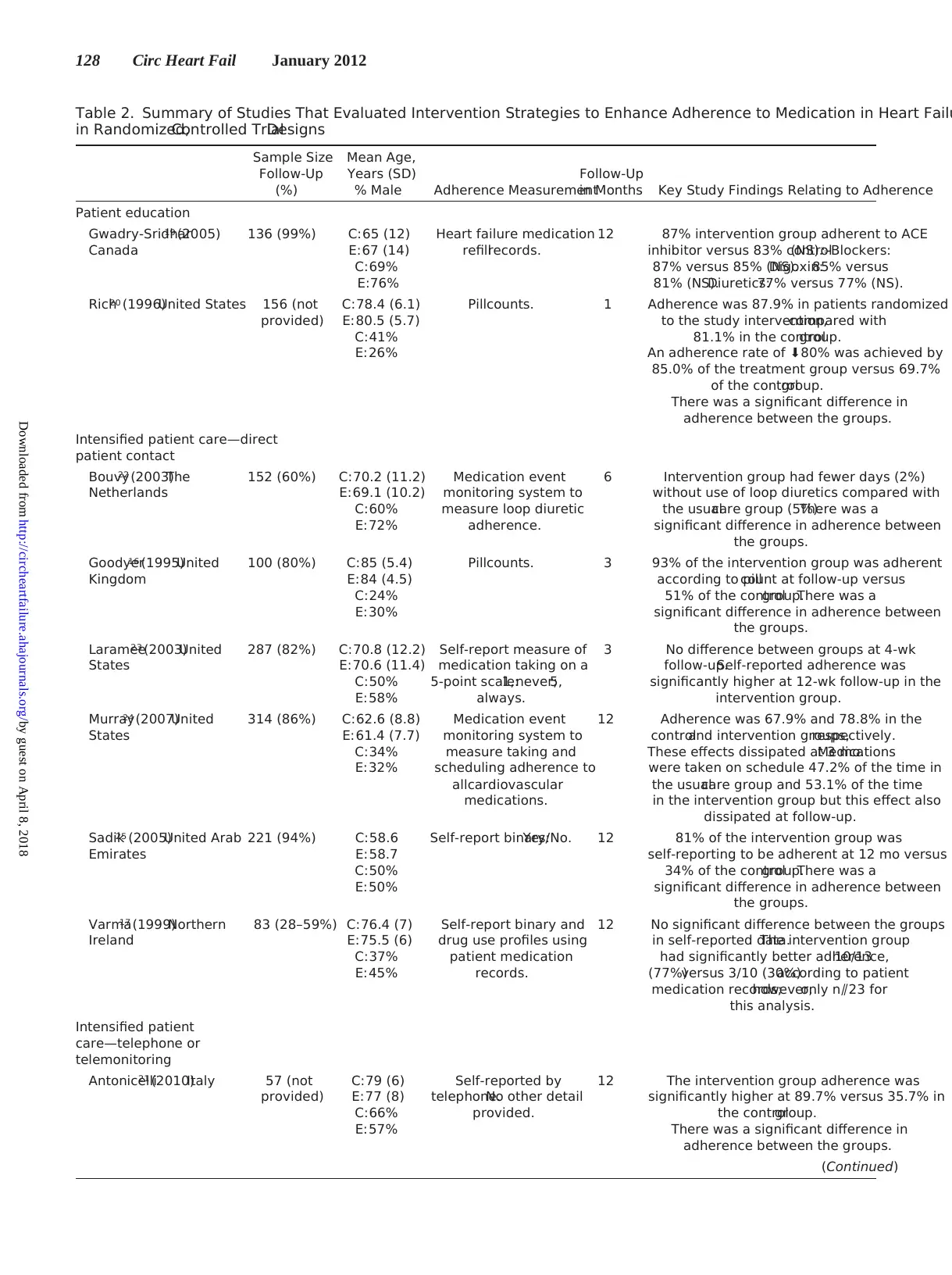

Characteristics of Included Studies

Sixteen randomized, controlled trials were identified, con-

taining data on 3305 patients with CHF. The median total

sample size was 144 patients, with a range of 37–902. The

majority of studies (9/16) were conducted in the United

States. The average age of the study samples ranged from 55

years 15 to 85 years. 16 Male participation in trials ranged from

37%17 to 99%. 18 The median follow-up time was 6 months,

ranging from 2 weeks to 12 months, with 6 of 16 (38%) of

studies having follow-up times of less than 6 months. The

mean percentage of patients included at follow-up in the 13

studies that provided this data was 79.8%, with a range of

28 –100%. Adherence was measured by self-report in 5

studies, the medication event monitoring system in 5 studies,

tablet counts in 3 studies, and medication refill records in 3

studies. Because of the heterogeneity of measurement and

limitations in reporting, it was not possible to report a

summary of baseline rates of adherence for the reviewed

studies. Table 1 outlines a list of intervention techniques that

could be identified from the reviewed studies. Full details of

all included studies are provided in Table 2.

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

All 16 studies reported random allocation; however, there

was limited information provided on sequence generation and

allocation concealment to evaluate this with confidence for

many of the studies in this review. Although double blinding

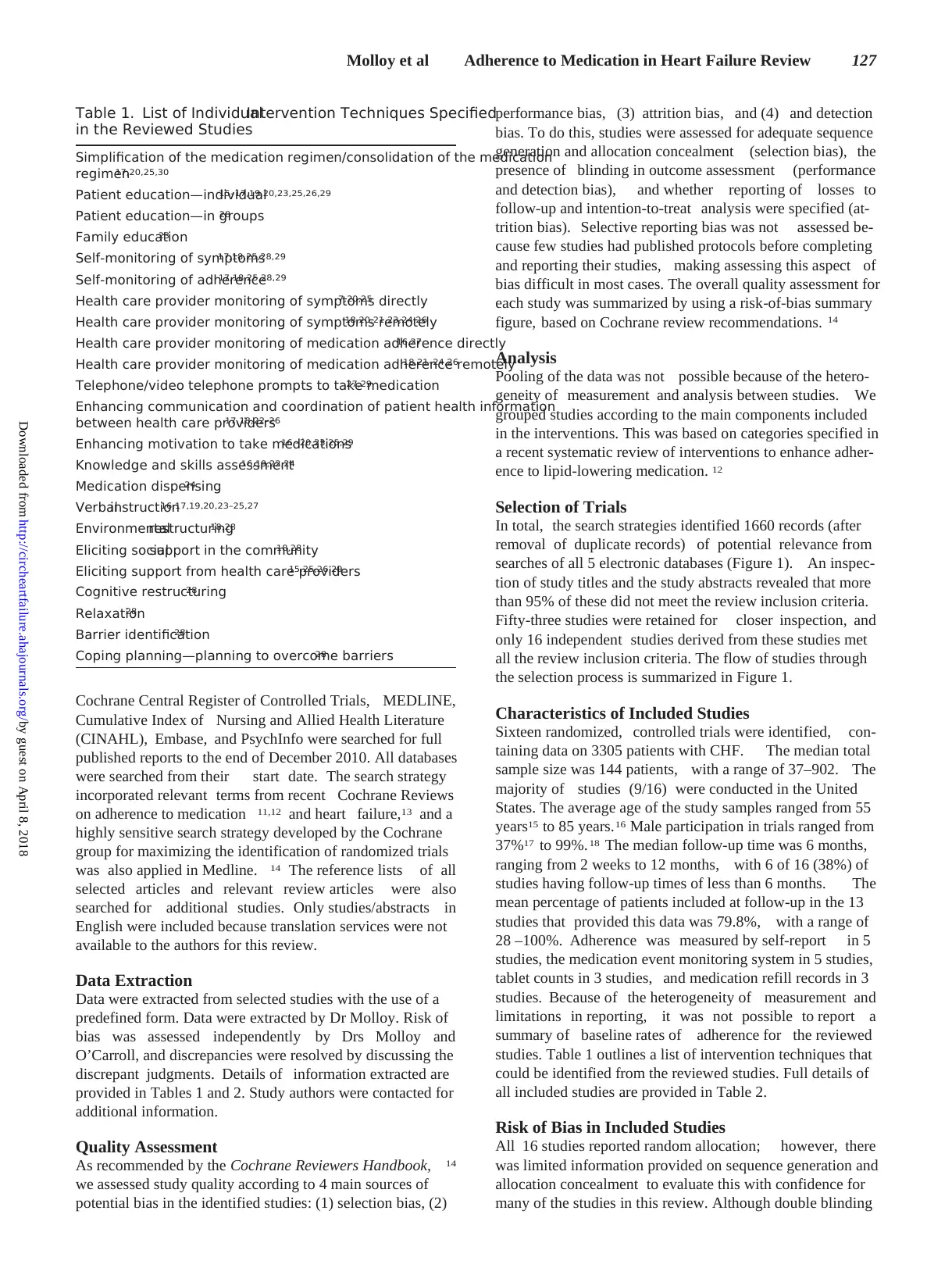

Table 1. List of IndividualIntervention Techniques Specified

in the Reviewed Studies

Simplification of the medication regimen/consolidation of the medication

regimen17,20,25,30

Patient education—individual15–17,19,20,23,25,26,29

Patient education—in groups28

Family education23

Self-monitoring of symptoms17,18,25,28,29

Self-monitoring of adherence17,18,25,28,29

Health care provider monitoring of symptoms directly7,20,25

Health care provider monitoring of symptoms remotely18,20,21,23,24,26

Health care provider monitoring of medication adherence directly16,27

Health care provider monitoring of medication adherence remotely18,21–24,26

Telephone/video telephone prompts to take medication27,29

Enhancing communication and coordination of patient health information

between health care providers17,18,22–26

Enhancing motivation to take medications16 –20,23,25,29

Knowledge and skills assessment16,19,22,24

Medication dispensing24

Verbalinstruction16,17,19,20,23–25,27

Environmentalrestructuring18,28

Eliciting socialsupport in the community18,28

Eliciting support from health care providers15,25,26,29

Cognitive restructuring28

Relaxation28

Barrier identification28

Coping planning—planning to overcome barriers28

Molloy et al Adherence to Medication in Heart Failure Review 127

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

(CINAHL), Embase, and PsychInfo were searched for full

published reports to the end of December 2010. All databases

were searched from their start date. The search strategy

incorporated relevant terms from recent Cochrane Reviews

on adherence to medication 11,12 and heart failure, 13 and a

highly sensitive search strategy developed by the Cochrane

group for maximizing the identification of randomized trials

was also applied in Medline. 14 The reference lists of all

selected articles and relevant review articles were also

searched for additional studies. Only studies/abstracts in

English were included because translation services were not

available to the authors for this review.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted from selected studies with the use of a

predefined form. Data were extracted by Dr Molloy. Risk of

bias was assessed independently by Drs Molloy and

O’Carroll, and discrepancies were resolved by discussing the

discrepant judgments. Details of information extracted are

provided in Tables 1 and 2. Study authors were contacted for

additional information.

Quality Assessment

As recommended by the Cochrane Reviewers Handbook, 14

we assessed study quality according to 4 main sources of

potential bias in the identified studies: (1) selection bias, (2)

performance bias, (3) attrition bias, and (4) and detection

bias. To do this, studies were assessed for adequate sequence

generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), the

presence of blinding in outcome assessment (performance

and detection bias), and whether reporting of losses to

follow-up and intention-to-treat analysis were specified (at-

trition bias). Selective reporting bias was not assessed be-

cause few studies had published protocols before completing

and reporting their studies, making assessing this aspect of

bias difficult in most cases. The overall quality assessment for

each study was summarized by using a risk-of-bias summary

figure, based on Cochrane review recommendations. 14

Analysis

Pooling of the data was not possible because of the hetero-

geneity of measurement and analysis between studies. We

grouped studies according to the main components included

in the interventions. This was based on categories specified in

a recent systematic review of interventions to enhance adher-

ence to lipid-lowering medication. 12

Selection of Trials

In total, the search strategies identified 1660 records (after

removal of duplicate records) of potential relevance from

searches of all 5 electronic databases (Figure 1). An inspec-

tion of study titles and the study abstracts revealed that more

than 95% of these did not meet the review inclusion criteria.

Fifty-three studies were retained for closer inspection, and

only 16 independent studies derived from these studies met

all the review inclusion criteria. The flow of studies through

the selection process is summarized in Figure 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Sixteen randomized, controlled trials were identified, con-

taining data on 3305 patients with CHF. The median total

sample size was 144 patients, with a range of 37–902. The

majority of studies (9/16) were conducted in the United

States. The average age of the study samples ranged from 55

years 15 to 85 years. 16 Male participation in trials ranged from

37%17 to 99%. 18 The median follow-up time was 6 months,

ranging from 2 weeks to 12 months, with 6 of 16 (38%) of

studies having follow-up times of less than 6 months. The

mean percentage of patients included at follow-up in the 13

studies that provided this data was 79.8%, with a range of

28 –100%. Adherence was measured by self-report in 5

studies, the medication event monitoring system in 5 studies,

tablet counts in 3 studies, and medication refill records in 3

studies. Because of the heterogeneity of measurement and

limitations in reporting, it was not possible to report a

summary of baseline rates of adherence for the reviewed

studies. Table 1 outlines a list of intervention techniques that

could be identified from the reviewed studies. Full details of

all included studies are provided in Table 2.

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

All 16 studies reported random allocation; however, there

was limited information provided on sequence generation and

allocation concealment to evaluate this with confidence for

many of the studies in this review. Although double blinding

Table 1. List of IndividualIntervention Techniques Specified

in the Reviewed Studies

Simplification of the medication regimen/consolidation of the medication

regimen17,20,25,30

Patient education—individual15–17,19,20,23,25,26,29

Patient education—in groups28

Family education23

Self-monitoring of symptoms17,18,25,28,29

Self-monitoring of adherence17,18,25,28,29

Health care provider monitoring of symptoms directly7,20,25

Health care provider monitoring of symptoms remotely18,20,21,23,24,26

Health care provider monitoring of medication adherence directly16,27

Health care provider monitoring of medication adherence remotely18,21–24,26

Telephone/video telephone prompts to take medication27,29

Enhancing communication and coordination of patient health information

between health care providers17,18,22–26

Enhancing motivation to take medications16 –20,23,25,29

Knowledge and skills assessment16,19,22,24

Medication dispensing24

Verbalinstruction16,17,19,20,23–25,27

Environmentalrestructuring18,28

Eliciting socialsupport in the community18,28

Eliciting support from health care providers15,25,26,29

Cognitive restructuring28

Relaxation28

Barrier identification28

Coping planning—planning to overcome barriers28

Molloy et al Adherence to Medication in Heart Failure Review 127

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

Table 2. Summary of Studies That Evaluated Intervention Strategies to Enhance Adherence to Medication in Heart Failu

in Randomized,Controlled TrialDesigns

Sample Size

Follow-Up

(%)

Mean Age,

Years (SD)

% Male Adherence Measurement

Follow-Up

in Months Key Study Findings Relating to Adherence

Patient education

Gwadry-Sridhar19 (2005)

Canada

136 (99%) C:65 (12)

E:67 (14)

C:69%

E:76%

Heart failure medication

refillrecords.

12 87% intervention group adherent to ACE

inhibitor versus 83% control(NS).-Blockers:

87% versus 85% (NS).Digoxin:85% versus

81% (NS).Diuretics:77% versus 77% (NS).

Rich20 (1996)United States 156 (not

provided)

C:78.4 (6.1)

E:80.5 (5.7)

C:41%

E:26%

Pillcounts. 1 Adherence was 87.9% in patients randomized

to the study intervention,compared with

81.1% in the controlgroup.

An adherence rate of ⬇80% was achieved by

85.0% of the treatment group versus 69.7%

of the controlgroup.

There was a significant difference in

adherence between the groups.

Intensified patient care—direct

patient contact

Bouvy22 (2003)The

Netherlands

152 (60%) C:70.2 (11.2)

E:69.1 (10.2)

C:60%

E:72%

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure loop diuretic

adherence.

6 Intervention group had fewer days (2%)

without use of loop diuretics compared with

the usualcare group (5%).There was a

significant difference in adherence between

the groups.

Goodyer16 (1995)United

Kingdom

100 (80%) C:85 (5.4)

E:84 (4.5)

C:24%

E:30%

Pillcounts. 3 93% of the intervention group was adherent

according to pillcount at follow-up versus

51% of the controlgroup.There was a

significant difference in adherence between

the groups.

Laramee23 (2003)United

States

287 (82%) C:70.8 (12.2)

E:70.6 (11.4)

C:50%

E:58%

Self-report measure of

medication taking on a

5-point scale:1,never;5,

always.

3 No difference between groups at 4-wk

follow-up.Self-reported adherence was

significantly higher at 12-wk follow-up in the

intervention group.

Murray24 (2007)United

States

314 (86%) C:62.6 (8.8)

E:61.4 (7.7)

C:34%

E:32%

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure taking and

scheduling adherence to

allcardiovascular

medications.

12 Adherence was 67.9% and 78.8% in the

controland intervention groups,respectively.

These effects dissipated at 3 mo.Medications

were taken on schedule 47.2% of the time in

the usualcare group and 53.1% of the time

in the intervention group but this effect also

dissipated at follow-up.

Sadik25 (2005)United Arab

Emirates

221 (94%) C:58.6

E:58.7

C:50%

E:50%

Self-report binary:Yes/No. 12 81% of the intervention group was

self-reporting to be adherent at 12 mo versus

34% of the controlgroup.There was a

significant difference in adherence between

the groups.

Varma17 (1999)Northern

Ireland

83 (28–59%) C:76.4 (7)

E:75.5 (6)

C:37%

E:45%

Self-report binary and

drug use profiles using

patient medication

records.

12 No significant difference between the groups

in self-reported data.The intervention group

had significantly better adherence,10/13

(77%)versus 3/10 (30%)according to patient

medication records;however,only n⫽23 for

this analysis.

Intensified patient

care—telephone or

telemonitoring

Antonicelli21 (2010)Italy 57 (not

provided)

C:79 (6)

E:77 (8)

C:66%

E:57%

Self-reported by

telephone.No other detail

provided.

12 The intervention group adherence was

significantly higher at 89.7% versus 35.7% in

the controlgroup.

There was a significant difference in

adherence between the groups.

(Continued)

128 Circ Heart Fail January 2012

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

in Randomized,Controlled TrialDesigns

Sample Size

Follow-Up

(%)

Mean Age,

Years (SD)

% Male Adherence Measurement

Follow-Up

in Months Key Study Findings Relating to Adherence

Patient education

Gwadry-Sridhar19 (2005)

Canada

136 (99%) C:65 (12)

E:67 (14)

C:69%

E:76%

Heart failure medication

refillrecords.

12 87% intervention group adherent to ACE

inhibitor versus 83% control(NS).-Blockers:

87% versus 85% (NS).Digoxin:85% versus

81% (NS).Diuretics:77% versus 77% (NS).

Rich20 (1996)United States 156 (not

provided)

C:78.4 (6.1)

E:80.5 (5.7)

C:41%

E:26%

Pillcounts. 1 Adherence was 87.9% in patients randomized

to the study intervention,compared with

81.1% in the controlgroup.

An adherence rate of ⬇80% was achieved by

85.0% of the treatment group versus 69.7%

of the controlgroup.

There was a significant difference in

adherence between the groups.

Intensified patient care—direct

patient contact

Bouvy22 (2003)The

Netherlands

152 (60%) C:70.2 (11.2)

E:69.1 (10.2)

C:60%

E:72%

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure loop diuretic

adherence.

6 Intervention group had fewer days (2%)

without use of loop diuretics compared with

the usualcare group (5%).There was a

significant difference in adherence between

the groups.

Goodyer16 (1995)United

Kingdom

100 (80%) C:85 (5.4)

E:84 (4.5)

C:24%

E:30%

Pillcounts. 3 93% of the intervention group was adherent

according to pillcount at follow-up versus

51% of the controlgroup.There was a

significant difference in adherence between

the groups.

Laramee23 (2003)United

States

287 (82%) C:70.8 (12.2)

E:70.6 (11.4)

C:50%

E:58%

Self-report measure of

medication taking on a

5-point scale:1,never;5,

always.

3 No difference between groups at 4-wk

follow-up.Self-reported adherence was

significantly higher at 12-wk follow-up in the

intervention group.

Murray24 (2007)United

States

314 (86%) C:62.6 (8.8)

E:61.4 (7.7)

C:34%

E:32%

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure taking and

scheduling adherence to

allcardiovascular

medications.

12 Adherence was 67.9% and 78.8% in the

controland intervention groups,respectively.

These effects dissipated at 3 mo.Medications

were taken on schedule 47.2% of the time in

the usualcare group and 53.1% of the time

in the intervention group but this effect also

dissipated at follow-up.

Sadik25 (2005)United Arab

Emirates

221 (94%) C:58.6

E:58.7

C:50%

E:50%

Self-report binary:Yes/No. 12 81% of the intervention group was

self-reporting to be adherent at 12 mo versus

34% of the controlgroup.There was a

significant difference in adherence between

the groups.

Varma17 (1999)Northern

Ireland

83 (28–59%) C:76.4 (7)

E:75.5 (6)

C:37%

E:45%

Self-report binary and

drug use profiles using

patient medication

records.

12 No significant difference between the groups

in self-reported data.The intervention group

had significantly better adherence,10/13

(77%)versus 3/10 (30%)according to patient

medication records;however,only n⫽23 for

this analysis.

Intensified patient

care—telephone or

telemonitoring

Antonicelli21 (2010)Italy 57 (not

provided)

C:79 (6)

E:77 (8)

C:66%

E:57%

Self-reported by

telephone.No other detail

provided.

12 The intervention group adherence was

significantly higher at 89.7% versus 35.7% in

the controlgroup.

There was a significant difference in

adherence between the groups.

(Continued)

128 Circ Heart Fail January 2012

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

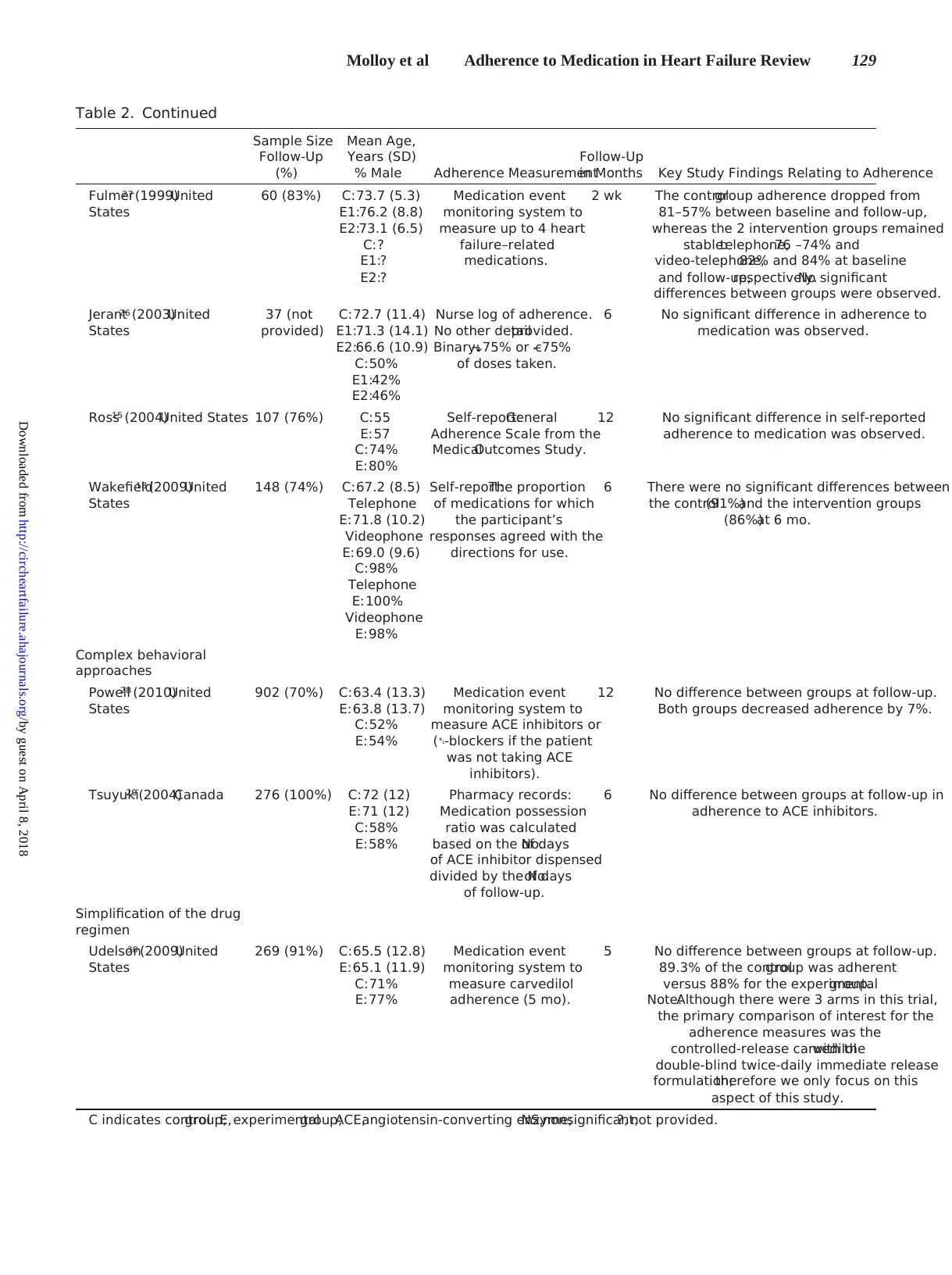

Table 2. Continued

Sample Size

Follow-Up

(%)

Mean Age,

Years (SD)

% Male Adherence Measurement

Follow-Up

in Months Key Study Findings Relating to Adherence

Fulmer27 (1999)United

States

60 (83%) C:73.7 (5.3)

E1:76.2 (8.8)

E2:73.1 (6.5)

C:?

E1:?

E2:?

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure up to 4 heart

failure–related

medications.

2 wk The controlgroup adherence dropped from

81–57% between baseline and follow-up,

whereas the 2 intervention groups remained

stable:telephone,76 –74% and

video-telephone,82% and 84% at baseline

and follow-up,respectively.No significant

differences between groups were observed.

Jerant26 (2003)United

States

37 (not

provided)

C:72.7 (11.4)

E1:71.3 (14.1)

E2:66.6 (10.9)

C:50%

E1:42%

E2:46%

Nurse log of adherence.

No other detailprovided.

Binary:⬎75% or ⱕ75%

of doses taken.

6 No significant difference in adherence to

medication was observed.

Ross15 (2004)United States 107 (76%) C:55

E:57

C:74%

E:80%

Self-report:General

Adherence Scale from the

MedicalOutcomes Study.

12 No significant difference in self-reported

adherence to medication was observed.

Wakefield18 (2009)United

States

148 (74%) C:67.2 (8.5)

Telephone

E:71.8 (10.2)

Videophone

E:69.0 (9.6)

C:98%

Telephone

E:100%

Videophone

E:98%

Self-report:The proportion

of medications for which

the participant’s

responses agreed with the

directions for use.

6 There were no significant differences between

the control(91%)and the intervention groups

(86%)at 6 mo.

Complex behavioral

approaches

Powell28 (2010)United

States

902 (70%) C:63.4 (13.3)

E:63.8 (13.7)

C:52%

E:54%

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure ACE inhibitors or

(-blockers if the patient

was not taking ACE

inhibitors).

12 No difference between groups at follow-up.

Both groups decreased adherence by 7%.

Tsuyuki29 (2004)Canada 276 (100%) C:72 (12)

E:71 (12)

C:58%

E:58%

Pharmacy records:

Medication possession

ratio was calculated

based on the No.of days

of ACE inhibitor dispensed

divided by the No.of days

of follow-up.

6 No difference between groups at follow-up in

adherence to ACE inhibitors.

Simplification of the drug

regimen

Udelson30 (2009)United

States

269 (91%) C:65.5 (12.8)

E:65.1 (11.9)

C:71%

E:77%

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure carvedilol

adherence (5 mo).

5 No difference between groups at follow-up.

89.3% of the controlgroup was adherent

versus 88% for the experimentalgroup.

Note:Although there were 3 arms in this trial,

the primary comparison of interest for the

adherence measures was the

controlled-release carvedilolwith the

double-blind twice-daily immediate release

formulation;therefore we only focus on this

aspect of this study.

C indicates controlgroup;E,experimentalgroup;ACE,angiotensin-converting enzyme;NS,nonsignificant;?, not provided.

Molloy et al Adherence to Medication in Heart Failure Review 129

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

Sample Size

Follow-Up

(%)

Mean Age,

Years (SD)

% Male Adherence Measurement

Follow-Up

in Months Key Study Findings Relating to Adherence

Fulmer27 (1999)United

States

60 (83%) C:73.7 (5.3)

E1:76.2 (8.8)

E2:73.1 (6.5)

C:?

E1:?

E2:?

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure up to 4 heart

failure–related

medications.

2 wk The controlgroup adherence dropped from

81–57% between baseline and follow-up,

whereas the 2 intervention groups remained

stable:telephone,76 –74% and

video-telephone,82% and 84% at baseline

and follow-up,respectively.No significant

differences between groups were observed.

Jerant26 (2003)United

States

37 (not

provided)

C:72.7 (11.4)

E1:71.3 (14.1)

E2:66.6 (10.9)

C:50%

E1:42%

E2:46%

Nurse log of adherence.

No other detailprovided.

Binary:⬎75% or ⱕ75%

of doses taken.

6 No significant difference in adherence to

medication was observed.

Ross15 (2004)United States 107 (76%) C:55

E:57

C:74%

E:80%

Self-report:General

Adherence Scale from the

MedicalOutcomes Study.

12 No significant difference in self-reported

adherence to medication was observed.

Wakefield18 (2009)United

States

148 (74%) C:67.2 (8.5)

Telephone

E:71.8 (10.2)

Videophone

E:69.0 (9.6)

C:98%

Telephone

E:100%

Videophone

E:98%

Self-report:The proportion

of medications for which

the participant’s

responses agreed with the

directions for use.

6 There were no significant differences between

the control(91%)and the intervention groups

(86%)at 6 mo.

Complex behavioral

approaches

Powell28 (2010)United

States

902 (70%) C:63.4 (13.3)

E:63.8 (13.7)

C:52%

E:54%

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure ACE inhibitors or

(-blockers if the patient

was not taking ACE

inhibitors).

12 No difference between groups at follow-up.

Both groups decreased adherence by 7%.

Tsuyuki29 (2004)Canada 276 (100%) C:72 (12)

E:71 (12)

C:58%

E:58%

Pharmacy records:

Medication possession

ratio was calculated

based on the No.of days

of ACE inhibitor dispensed

divided by the No.of days

of follow-up.

6 No difference between groups at follow-up in

adherence to ACE inhibitors.

Simplification of the drug

regimen

Udelson30 (2009)United

States

269 (91%) C:65.5 (12.8)

E:65.1 (11.9)

C:71%

E:77%

Medication event

monitoring system to

measure carvedilol

adherence (5 mo).

5 No difference between groups at follow-up.

89.3% of the controlgroup was adherent

versus 88% for the experimentalgroup.

Note:Although there were 3 arms in this trial,

the primary comparison of interest for the

adherence measures was the

controlled-release carvedilolwith the

double-blind twice-daily immediate release

formulation;therefore we only focus on this

aspect of this study.

C indicates controlgroup;E,experimentalgroup;ACE,angiotensin-converting enzyme;NS,nonsignificant;?, not provided.

Molloy et al Adherence to Medication in Heart Failure Review 129

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

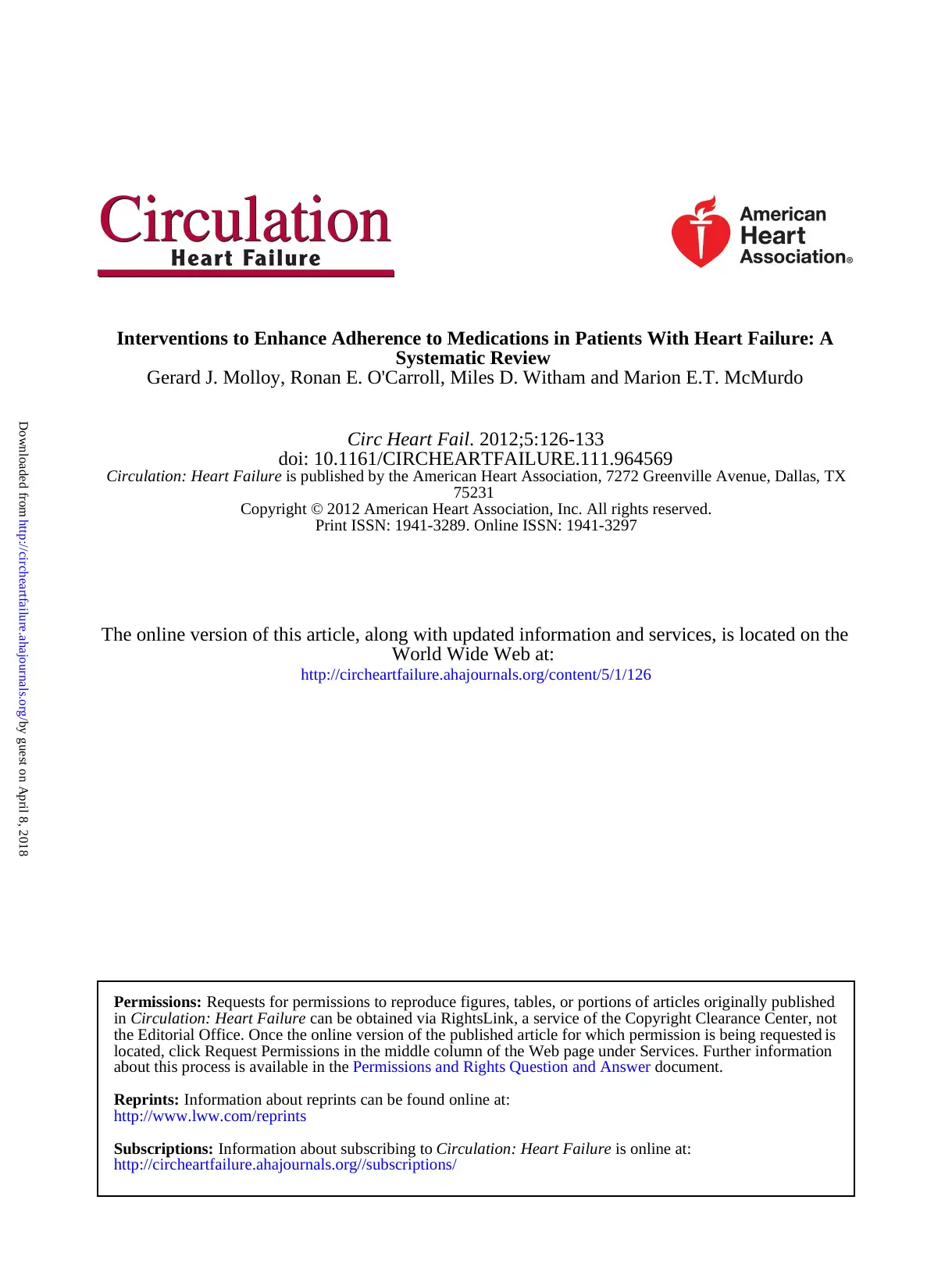

is not possible in most behavioral trials, the issue of blinding

was addressed in 31% (5/16) of studies. Eleven studies

provided information on loss to follow-up, but only 6 studies

clearly specified intention-to-treat analyses. Figure 2 provides

summary data on risk of bias across the 16 studies.

Types of Intervention

Interventions could be classified into the 4 main categories

identified in a recent review of interventions to improve

adherence to lipid-lowering medication. 12 It is important to

note, however, that several multicomponent interventions

could be included in more than 1 of these 4 categories, and a

distinct set of intervention strategies categories did not

emerge, as can be seen in Tables 1 and 2.

(1) Patient Education and Information

The educational intervention described by Gwadry-Sridhar et

al 19 found no evidence that this kind of intervention can lead

to enhanced adherence. The multidisciplinary intervention

described by Rich et al,20 which included aspects of education

and information provision, found evidence that a multicom-

ponent intervention can lead to enhanced medication adher-

ence. It is important to note that this intervention also

incorporated intensified patient care and simplification or

“consolidation” of medication regimens.

(2) Intensified Patient Care

The 8 studies that involved intensified patient care can be

subdivided into 6 direct patient contact interventions 16,17,22–25

and 5 telephone or telemonitoring programs. 15,18,21,26,27 All 6

of the direct patient contact interventions led to enhanced

medication adherence, whereas only 1 of the telephone or

telemonitoring programs led to enhanced adherence. Five of

the 6 direct patient contact interventions were pharmacist-led.

(3) Complex Behavioral Approaches

The largest study examining interventions to enhance medi-

cation adherence in CHF conducted to date found no evi-

dence that that a complex multicomponent intervention that

included a range of behavior change techniques led to

enhanced medication adherence. 28 A smaller study that also

used a complex intervention that included a range of behavior

change strategies also reported null results. 29

(4) Simplification of the Drug Regimen

The single study that attempted to evaluate this strategy on its

own did not find evidence of enhanced adherence after a

simplification of the drug regimen. 30 Simplification of med-

ication regimens may have occurred in an unsystematic way

in some of the other interventions included in this review. 20

Main Findings

This review found that 8 of 16 randomized, controlled trials

identified provide evidence that adherence to medication can

be enhanced in patients with CHF. Intensified patient care,

particularly involving pharmacists, may be beneficial, as

there are at least 5 studies that show intensified care from a

pharmacist, 16,17,22,24,25 in conjunction with other health care

professionals, leads to better medication adherence in patients

Figure 1. Selection of articles for system-

atic review. RCT indicates randomized,

controlled trial.

Figure 2. Risk of bias summary.

130 Circ Heart Fail January 2012

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

was addressed in 31% (5/16) of studies. Eleven studies

provided information on loss to follow-up, but only 6 studies

clearly specified intention-to-treat analyses. Figure 2 provides

summary data on risk of bias across the 16 studies.

Types of Intervention

Interventions could be classified into the 4 main categories

identified in a recent review of interventions to improve

adherence to lipid-lowering medication. 12 It is important to

note, however, that several multicomponent interventions

could be included in more than 1 of these 4 categories, and a

distinct set of intervention strategies categories did not

emerge, as can be seen in Tables 1 and 2.

(1) Patient Education and Information

The educational intervention described by Gwadry-Sridhar et

al 19 found no evidence that this kind of intervention can lead

to enhanced adherence. The multidisciplinary intervention

described by Rich et al,20 which included aspects of education

and information provision, found evidence that a multicom-

ponent intervention can lead to enhanced medication adher-

ence. It is important to note that this intervention also

incorporated intensified patient care and simplification or

“consolidation” of medication regimens.

(2) Intensified Patient Care

The 8 studies that involved intensified patient care can be

subdivided into 6 direct patient contact interventions 16,17,22–25

and 5 telephone or telemonitoring programs. 15,18,21,26,27 All 6

of the direct patient contact interventions led to enhanced

medication adherence, whereas only 1 of the telephone or

telemonitoring programs led to enhanced adherence. Five of

the 6 direct patient contact interventions were pharmacist-led.

(3) Complex Behavioral Approaches

The largest study examining interventions to enhance medi-

cation adherence in CHF conducted to date found no evi-

dence that that a complex multicomponent intervention that

included a range of behavior change techniques led to

enhanced medication adherence. 28 A smaller study that also

used a complex intervention that included a range of behavior

change strategies also reported null results. 29

(4) Simplification of the Drug Regimen

The single study that attempted to evaluate this strategy on its

own did not find evidence of enhanced adherence after a

simplification of the drug regimen. 30 Simplification of med-

ication regimens may have occurred in an unsystematic way

in some of the other interventions included in this review. 20

Main Findings

This review found that 8 of 16 randomized, controlled trials

identified provide evidence that adherence to medication can

be enhanced in patients with CHF. Intensified patient care,

particularly involving pharmacists, may be beneficial, as

there are at least 5 studies that show intensified care from a

pharmacist, 16,17,22,24,25 in conjunction with other health care

professionals, leads to better medication adherence in patients

Figure 1. Selection of articles for system-

atic review. RCT indicates randomized,

controlled trial.

Figure 2. Risk of bias summary.

130 Circ Heart Fail January 2012

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

with CHF. There is emerging evidence that patient education

and self-management training alone is not effective in en-

hancing adherence to medication. 19,28,29 The overall conclu-

sion of the methodological quality of the 16 trials included in

this review indicate that there is limited high-quality evidence

evaluating the effectiveness of specific adherence-enhancing

interventions in patients with CHF and that the findings of

many of the existing randomized, controlled trials should be

interpreted with caution. The heterogeneity in intervention

techniques and measurement methodology observed between

the studies in this review means that a conclusive literature on

enhancing adherence to medication in heart failure has yet to

emerge. This mirrors findings from other related broader

reviews in a range of clinical conditions. 11,12

Our assessment of the sample characteristics also revealed

that the patients enrolled into these studies were not repre-

sentative of the patients with CHF seen in clinical practice in

terms of age and sex profile. This indicates that selection

biases are operating in recruitment in this area of research,

which limits the generalizability of these findings. The

relatively short and variable follow-up times seen across

these 16 studies also show that there are limited data on the

sustainability of both the intervention strategies and the

intervention effects in those studies that found significantly

enhanced adherence. Five of the reports included23–26,29

incorporated a health economics evaluation with varying

degrees of sophistication; therefore the cost implications of

most of the intervention strategies are unknown. However, 2

of these studies26,29 reported significant health care cost

reductions as a consequence of the interventions. This raises

the possibility that medication-enhancing interventions can

reduce health care costs, which may be particularly important

in new health care funding environments, for example,

accountable care organizations in the United States or the

Quality Outcomes Framework in the United Kingdom.

Although a number of studies in this review did include

interventions that used information technology, specifically

telemonitoring of patients with CHF, 13 this area of research

has yet to evaluate the role or potential of electronic patient

records or new developments in handheld communication

devices and social media to enhance adherence to medication

in heart failure. Future work should attempt to investigate the

potential of these new technologies in motivating, enabling,

and prompting patients with heart failure to take their

medications as prescribed.

Limitations

The most obvious limitation in this review was that quanti-

tative meta-analysis was not possible. A recent meta-analysis

of 33 studies 31 testing adherence-enhancing interventions for

older adults estimated that effect sizes were likely to be in the

small to medium range, with a summary standardized mean

difference of 0.33 in medication adherence observed between

control and intervention groups. Only 1 of the studies in the

published meta-analysis is included in our review. 20 Until

there is greater consistency of measurement and analysis

across studies, we cannot know whether similar effects can be

achieved in CHF populations. Future investigators should

therefore assume that intervention effects will not be larger

than the small to medium range when conducting sample size

calculations for new studies.

The limited number of studies identified that describe a

heterogeneous range of interventions prevent us from draw-

ing firm conclusions on many types of adherence promoting

strategies for patients with CHF. For example, the null

findings for the one study 30 in this review that compared

once-daily dosing with twice-daily dosing should be consid-

ered in light of the limitations of that particular study and the

considerable evidence in other conditions that simplifying

medication regimens is associated with better adherence. 32

There was also limited detail provided on the contexts in

which interventions were delivered. This makes it difficult to

know where and when effective interventions to enhance

adherence to medication are best delivered.

Implications for Research

Adherence to medication and other aspects of self-care for a

debilitating symptomatic chronic illness such as CHF is a

complex behavior with multifactorial determinants, 6,33 in-

cluding a range of individual and social-environment fac-

tors.34,35 Although earlier studies have reviewed the broader

issues of adherence to health professionals’ self-care recom-

mendation in CHF, 5 this review focused on those interven-

tions that specifically address medication adherence for 3 key

reasons. First, the association between medication adherence

and health outcomes is more precisely described, 2,4 whereas

the benefits of other aspects of adherence to CHF self-care

cannot be estimated with the same degree of precision

because of measurement and study design limitations that are

inherent in studying these phenomena, for example, weighing

oneself daily and limiting sodium intake. Second, adherence

to medication is a very different behavioral phenomenon 36

than other aspects of adherence to self-care in heart failure

that is likely to have different determinants. Finally,

intervention strategies to enhance adherence to medication

are likely to be of a different form than many other aspects

of adherence to self-care, given the unique barriers and

facilitators to this behavior. 5,33 Therefore, there is clearly

scope to develop a focus for further investigation into

adherence to medication in heart failure as opposed to more

generalized management of self-care in heart failure. 5

Four of the studies included in this review 18,21,28,30 have

been published since the Cochrane review of interventions for

enhancing medication adherence,11 and only 1 of the studies25

included in the present review was included in that Cochrane

review. Another more recent relevant review on improving

adherence to cardiovascular medication 10 included only 4

studies from the present review. 16,24,27,30

Many of the reviewed studies provided limited information

on the content of the study interventions. This prevents the

development of a cumulative body of research or even simple

replication of individual studies. The increasing emphasis on

publishing detailed protocol reports in advance of the study

commencement has reduced this problem in more recent

studies. This area of research would, however, be greatly

strengthened by the development of a taxonomy of behavior

change techniques for medication adherence– enhancing in-

terventions to standardize the content, classification, and

Molloy et al Adherence to Medication in Heart Failure Review 131

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

and self-management training alone is not effective in en-

hancing adherence to medication. 19,28,29 The overall conclu-

sion of the methodological quality of the 16 trials included in

this review indicate that there is limited high-quality evidence

evaluating the effectiveness of specific adherence-enhancing

interventions in patients with CHF and that the findings of

many of the existing randomized, controlled trials should be

interpreted with caution. The heterogeneity in intervention

techniques and measurement methodology observed between

the studies in this review means that a conclusive literature on

enhancing adherence to medication in heart failure has yet to

emerge. This mirrors findings from other related broader

reviews in a range of clinical conditions. 11,12

Our assessment of the sample characteristics also revealed

that the patients enrolled into these studies were not repre-

sentative of the patients with CHF seen in clinical practice in

terms of age and sex profile. This indicates that selection

biases are operating in recruitment in this area of research,

which limits the generalizability of these findings. The

relatively short and variable follow-up times seen across

these 16 studies also show that there are limited data on the

sustainability of both the intervention strategies and the

intervention effects in those studies that found significantly

enhanced adherence. Five of the reports included23–26,29

incorporated a health economics evaluation with varying

degrees of sophistication; therefore the cost implications of

most of the intervention strategies are unknown. However, 2

of these studies26,29 reported significant health care cost

reductions as a consequence of the interventions. This raises

the possibility that medication-enhancing interventions can

reduce health care costs, which may be particularly important

in new health care funding environments, for example,

accountable care organizations in the United States or the

Quality Outcomes Framework in the United Kingdom.

Although a number of studies in this review did include

interventions that used information technology, specifically

telemonitoring of patients with CHF, 13 this area of research

has yet to evaluate the role or potential of electronic patient

records or new developments in handheld communication

devices and social media to enhance adherence to medication

in heart failure. Future work should attempt to investigate the

potential of these new technologies in motivating, enabling,

and prompting patients with heart failure to take their

medications as prescribed.

Limitations

The most obvious limitation in this review was that quanti-

tative meta-analysis was not possible. A recent meta-analysis

of 33 studies 31 testing adherence-enhancing interventions for

older adults estimated that effect sizes were likely to be in the

small to medium range, with a summary standardized mean

difference of 0.33 in medication adherence observed between

control and intervention groups. Only 1 of the studies in the

published meta-analysis is included in our review. 20 Until

there is greater consistency of measurement and analysis

across studies, we cannot know whether similar effects can be

achieved in CHF populations. Future investigators should

therefore assume that intervention effects will not be larger

than the small to medium range when conducting sample size

calculations for new studies.

The limited number of studies identified that describe a

heterogeneous range of interventions prevent us from draw-

ing firm conclusions on many types of adherence promoting

strategies for patients with CHF. For example, the null

findings for the one study 30 in this review that compared

once-daily dosing with twice-daily dosing should be consid-

ered in light of the limitations of that particular study and the

considerable evidence in other conditions that simplifying

medication regimens is associated with better adherence. 32

There was also limited detail provided on the contexts in

which interventions were delivered. This makes it difficult to

know where and when effective interventions to enhance

adherence to medication are best delivered.

Implications for Research

Adherence to medication and other aspects of self-care for a

debilitating symptomatic chronic illness such as CHF is a

complex behavior with multifactorial determinants, 6,33 in-

cluding a range of individual and social-environment fac-

tors.34,35 Although earlier studies have reviewed the broader

issues of adherence to health professionals’ self-care recom-

mendation in CHF, 5 this review focused on those interven-

tions that specifically address medication adherence for 3 key

reasons. First, the association between medication adherence

and health outcomes is more precisely described, 2,4 whereas

the benefits of other aspects of adherence to CHF self-care

cannot be estimated with the same degree of precision

because of measurement and study design limitations that are

inherent in studying these phenomena, for example, weighing

oneself daily and limiting sodium intake. Second, adherence

to medication is a very different behavioral phenomenon 36

than other aspects of adherence to self-care in heart failure

that is likely to have different determinants. Finally,

intervention strategies to enhance adherence to medication

are likely to be of a different form than many other aspects

of adherence to self-care, given the unique barriers and

facilitators to this behavior. 5,33 Therefore, there is clearly

scope to develop a focus for further investigation into

adherence to medication in heart failure as opposed to more

generalized management of self-care in heart failure. 5

Four of the studies included in this review 18,21,28,30 have

been published since the Cochrane review of interventions for

enhancing medication adherence,11 and only 1 of the studies25

included in the present review was included in that Cochrane

review. Another more recent relevant review on improving

adherence to cardiovascular medication 10 included only 4

studies from the present review. 16,24,27,30

Many of the reviewed studies provided limited information

on the content of the study interventions. This prevents the

development of a cumulative body of research or even simple

replication of individual studies. The increasing emphasis on

publishing detailed protocol reports in advance of the study

commencement has reduced this problem in more recent

studies. This area of research would, however, be greatly

strengthened by the development of a taxonomy of behavior

change techniques for medication adherence– enhancing in-

terventions to standardize the content, classification, and

Molloy et al Adherence to Medication in Heart Failure Review 131

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

description of intervention strategies. The value of such

taxonomies is gaining increasing recognition in other areas of

behavioral science that focus on the role self-care in promot-

ing health. 37 Because the content and context of many

adherence-enhancing interventions is not clearly specified in

standardized terminology and theory from behavioral science

is often absent, the approaches to intervention development in

this area can be likened to developing antihypertensive

medications without any understanding of the pharmacology

of the medication, the physiology of systemic blood pressure

control, or the pathophysiology of hypertension. 38

Implications for Practice

There is clearly scope to significantly improve outcomes in

heart failure by enhancing adherence to those existing med-

ications that are known to reduce morbidity and mortality

from heart failure. CHF medication regimens have become

increasingly complex as new treatments have emerged, 6

which provides a challenge for patients with CHF to manage.

Practitioners should consider that developing effective meth-

ods to increase patient adherence to existing medications with

known efficacy could have far greater health benefits than

providing new treatments that may not be followed. 11 The

reviewed studies do provide evidence that enhanced adher-

ence to medications can be achieved in heart failure patients

and that the role of pharmacists may be particularly impor-

tant, in particular, direct communication between patient,

pharmacists, and other health care providers.22,24,25 This

review also suggests that patient education about CHF or

self-management training alone may not be effective. Overall

it is clear, however, that formal recommendations on the best

approaches to enhance adherence to medication in CHF

cannot be derived from the existing studies. New studies with

more clearly justified and specified methodology are required

to generate a cumulative body of findings that could be used

to inform clinical practice. In particular, more explicit use of

behavioral sciences in developing adherence interventions in

CHF is clearly warranted.

Conclusions

It may be possible to improve adherence to medication in

patients with CHF by using a range of strategies; however,

the specification of effective techniques requires greater

clarity in this literature. There is currently limited high-

quality evidence on the effectiveness of interventions that aim

to enhance adherence to medication in typical heart failure

patients, and further research is needed to identify the

optimum strategies for implementation in clinical practice.

Disclosures

None.

References

1. Jhund PS, Macintyre K, Simpson CR, Lewsey JD, Stewart S, Redpath A,

Chalmers JW, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. Long-term trends in first hos-

pitalization for heart failure and subsequent survival between 1986 and

2003: a population study of 5.1 million people. Circulation. 2009;119:

515–523.

2. SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with

reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure: the

SOLVD Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302.

3. Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, Colucci WS, Fowler MB, Gilbert EM,

Shusterman NH. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in

patients with chronic heart failure: US Carvedilol Heart Failure Study

Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1349 –1355.

4. Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky

J, Wittes J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in

patients with severe heart failure: Randomized Aldactone Evaluation

Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709 –717.

5. van der Wal MH, Jaarsma T. Adherence in heart failure in the elderly:

problem and possible solutions. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125:203–208.

6. Hauptman PJ. Medication adherence in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev.

2008;13:99 –106.

7. Butler J, Arbogast PG, Daugherty J, Jain MK, Ray WA, Griffin MR.

Outpatient utilization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors among

heart failure patients after hospital discharge. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;

43:2036 –2043.

8. Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Avorn J. Noncompliance

with congestive heart failure therapy in the elderly. Arch Intern Med.

1994;154:433– 437.

9. Wu JR, Moser DK, De Jong MJ, Rayens MK, Chung ML, Riegel B,

Lennie TA. Defining an evidence-based cutpoint for medication

adherence in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009;157:285–291.

10. Glynn L, Fahey T. Cardiovascular medication: improving adherence. Clin

Evid (Online). 2011. Available at http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com.

11. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for

enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:

CD000011.

12. Schedlbauer A, Davies P, Fahey T. Interventions to improve adherence to

lipid lowering medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;

CD004371.

13. Inglis SC, Clark RA, McAlister FA, Ball J, Lewinter C, Cullington D,

Stewart S, Cleland JG. Structured telephone support or telemonitoring

programmes for patients with chronic heart failure. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 2010;8:CD007228.

14. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of

Interventions. Chichester, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration and John

Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008.

15. Ross SE, Moore LA, Earnest MA, Wittevrongel L, Lin CT. Providing a

web-based online medical record with electronic communication capa-

bilities to patients with congestive heart failure: randomized trial. J Med

Internet Res. 2004;6:e12.

16. Goodyer LI, Miskelly F, Milligan P. Does encouraging good compliance

improve patients’ clinical condition in heart failure? Br J Clin Pract.

1995;49:173–176.

17. Varma S, McElnay JC, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, Varma M. Pharma-

ceutical care of patients with congestive heart failure: interventions and

outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:860 – 869.

18. Wakefield BJ, Holman JE, Ray A, Scherubel M, Burns TL, Kienzle MG,

Rosenthal GE. Outcomes of a home telehealth intervention for patients

with heart failure. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15:46 –50.

19. Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Arnold JM, Zhang Y, Brown JE, Marchiori G,

Guyatt G. Pilot study to determine the impact of a multidisciplinary

educational intervention in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Am

Heart J. 2005;150:982e1–982e9.

20. Rich MW, Gray DB, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Luther P. Effect of a

multidisciplinary intervention on medication compliance in elderly

patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Med. 1996;101:270 –276.

21. Antonicelli R, Mazzanti I, Abbatecola AM, Parati G. Impact of home

patient telemonitoring on use of beta-blockers in congestive heart failure.

Drugs Aging. 2010;27:801– 805.

22. Bouvy ML, Heerdink ER, Urquhart J, Grobbee DE, Hoes AW, Leufkens

HG. Effect of a pharmacist-led intervention on diuretic compliance in

heart failure patients: a randomized controlled study. J Card Fail. 2003;

9:404 – 411.

23. Laramee AS, Levinsky SK, Sargent J, Ross R, Callas P. Case man-

agement in a heterogeneous congestive heart failure population: a ran-

domized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:809 – 817.

24. Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, Tu W, Weiner M, Morrow D, Stroupe KT,

Wu J, Clark D, Smith F, Gradus-Pizlo I, Weinberger M, Brater DC.

Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure:

a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:714 –725.

25. Sadik A, Yousif M, McElnay JC. Pharmaceutical care of patients with

heart failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:183–193.

26. Jerant AF, Azari R, Martinez C, Nesbitt TS. A randomized trial of

telenursing to reduce hospitalization for heart failure: patient-centered

132 Circ Heart Fail January 2012

by guest on April 8, 2018http://circheartfailure.ahajournals.org/Downloaded from

taxonomies is gaining increasing recognition in other areas of

behavioral science that focus on the role self-care in promot-

ing health. 37 Because the content and context of many

adherence-enhancing interventions is not clearly specified in

standardized terminology and theory from behavioral science

is often absent, the approaches to intervention development in

this area can be likened to developing antihypertensive

medications without any understanding of the pharmacology

of the medication, the physiology of systemic blood pressure

control, or the pathophysiology of hypertension. 38

Implications for Practice

There is clearly scope to significantly improve outcomes in

heart failure by enhancing adherence to those existing med-

ications that are known to reduce morbidity and mortality

from heart failure. CHF medication regimens have become

increasingly complex as new treatments have emerged, 6

which provides a challenge for patients with CHF to manage.

Practitioners should consider that developing effective meth-

ods to increase patient adherence to existing medications with

known efficacy could have far greater health benefits than

providing new treatments that may not be followed. 11 The

reviewed studies do provide evidence that enhanced adher-

ence to medications can be achieved in heart failure patients

and that the role of pharmacists may be particularly impor-

tant, in particular, direct communication between patient,

pharmacists, and other health care providers.22,24,25 This

review also suggests that patient education about CHF or

self-management training alone may not be effective. Overall

it is clear, however, that formal recommendations on the best

approaches to enhance adherence to medication in CHF

cannot be derived from the existing studies. New studies with

more clearly justified and specified methodology are required

to generate a cumulative body of findings that could be used

to inform clinical practice. In particular, more explicit use of

behavioral sciences in developing adherence interventions in

CHF is clearly warranted.

Conclusions

It may be possible to improve adherence to medication in

patients with CHF by using a range of strategies; however,

the specification of effective techniques requires greater

clarity in this literature. There is currently limited high-

quality evidence on the effectiveness of interventions that aim

to enhance adherence to medication in typical heart failure

patients, and further research is needed to identify the

optimum strategies for implementation in clinical practice.

Disclosures

None.

References

1. Jhund PS, Macintyre K, Simpson CR, Lewsey JD, Stewart S, Redpath A,

Chalmers JW, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. Long-term trends in first hos-

pitalization for heart failure and subsequent survival between 1986 and

2003: a population study of 5.1 million people. Circulation. 2009;119:

515–523.

2. SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with

reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure: the

SOLVD Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302.

3. Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, Colucci WS, Fowler MB, Gilbert EM,

Shusterman NH. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in

patients with chronic heart failure: US Carvedilol Heart Failure Study

Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1349 –1355.

4. Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky

J, Wittes J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in

patients with severe heart failure: Randomized Aldactone Evaluation

Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709 –717.

5. van der Wal MH, Jaarsma T. Adherence in heart failure in the elderly:

problem and possible solutions. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125:203–208.

6. Hauptman PJ. Medication adherence in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev.

2008;13:99 –106.

7. Butler J, Arbogast PG, Daugherty J, Jain MK, Ray WA, Griffin MR.

Outpatient utilization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors among

heart failure patients after hospital discharge. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;

43:2036 –2043.

8. Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Avorn J. Noncompliance

with congestive heart failure therapy in the elderly. Arch Intern Med.

1994;154:433– 437.

9. Wu JR, Moser DK, De Jong MJ, Rayens MK, Chung ML, Riegel B,

Lennie TA. Defining an evidence-based cutpoint for medication

adherence in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009;157:285–291.

10. Glynn L, Fahey T. Cardiovascular medication: improving adherence. Clin

Evid (Online). 2011. Available at http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com.

11. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for

enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:

CD000011.

12. Schedlbauer A, Davies P, Fahey T. Interventions to improve adherence to

lipid lowering medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;

CD004371.

13. Inglis SC, Clark RA, McAlister FA, Ball J, Lewinter C, Cullington D,

Stewart S, Cleland JG. Structured telephone support or telemonitoring

programmes for patients with chronic heart failure. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 2010;8:CD007228.

14. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of

Interventions. Chichester, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration and John

Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008.

15. Ross SE, Moore LA, Earnest MA, Wittevrongel L, Lin CT. Providing a

web-based online medical record with electronic communication capa-

bilities to patients with congestive heart failure: randomized trial. J Med

Internet Res. 2004;6:e12.

16. Goodyer LI, Miskelly F, Milligan P. Does encouraging good compliance

improve patients’ clinical condition in heart failure? Br J Clin Pract.

1995;49:173–176.

17. Varma S, McElnay JC, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, Varma M. Pharma-

ceutical care of patients with congestive heart failure: interventions and

outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 1999;19:860 – 869.

18. Wakefield BJ, Holman JE, Ray A, Scherubel M, Burns TL, Kienzle MG,

Rosenthal GE. Outcomes of a home telehealth intervention for patients

with heart failure. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15:46 –50.

19. Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Arnold JM, Zhang Y, Brown JE, Marchiori G,

Guyatt G. Pilot study to determine the impact of a multidisciplinary