Comprehensive Analysis of Nitrogen Metabolism in the Human Body

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/15

|9

|1466

|168

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a detailed overview of nitrogen metabolism in the human body, beginning with the dietary intake of nitrogen through protein consumption. It explains how amino acids are broken down, releasing nitrogen in the form of ammonia, and how the carbon backbones are converted into glucose. The report describes the digestion process, including the role of enzymes in the stomach and small intestine, and the absorption of amino acids. It explores the transamination of amino acids in the liver, the role of glutamate, and the oxidative deamination process. The urea cycle is explained step-by-step, including the production of carbamoyl phosphate, the conversion of ornithine to citrulline, and the final excretion of urea. The report also highlights the interconnectedness of the urea cycle with the Krebs cycle through the malate-aspartate shuttle and the regulatory mechanisms of the urea cycle, including the roles of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I and N-acetyl glutamate. The report concludes with a discussion of the key enzymes and pathways involved in maintaining nitrogen balance within the body and provides relevant references.

Running head: NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author Note:

NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

Name of the Student:

Name of the University:

Author Note:

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

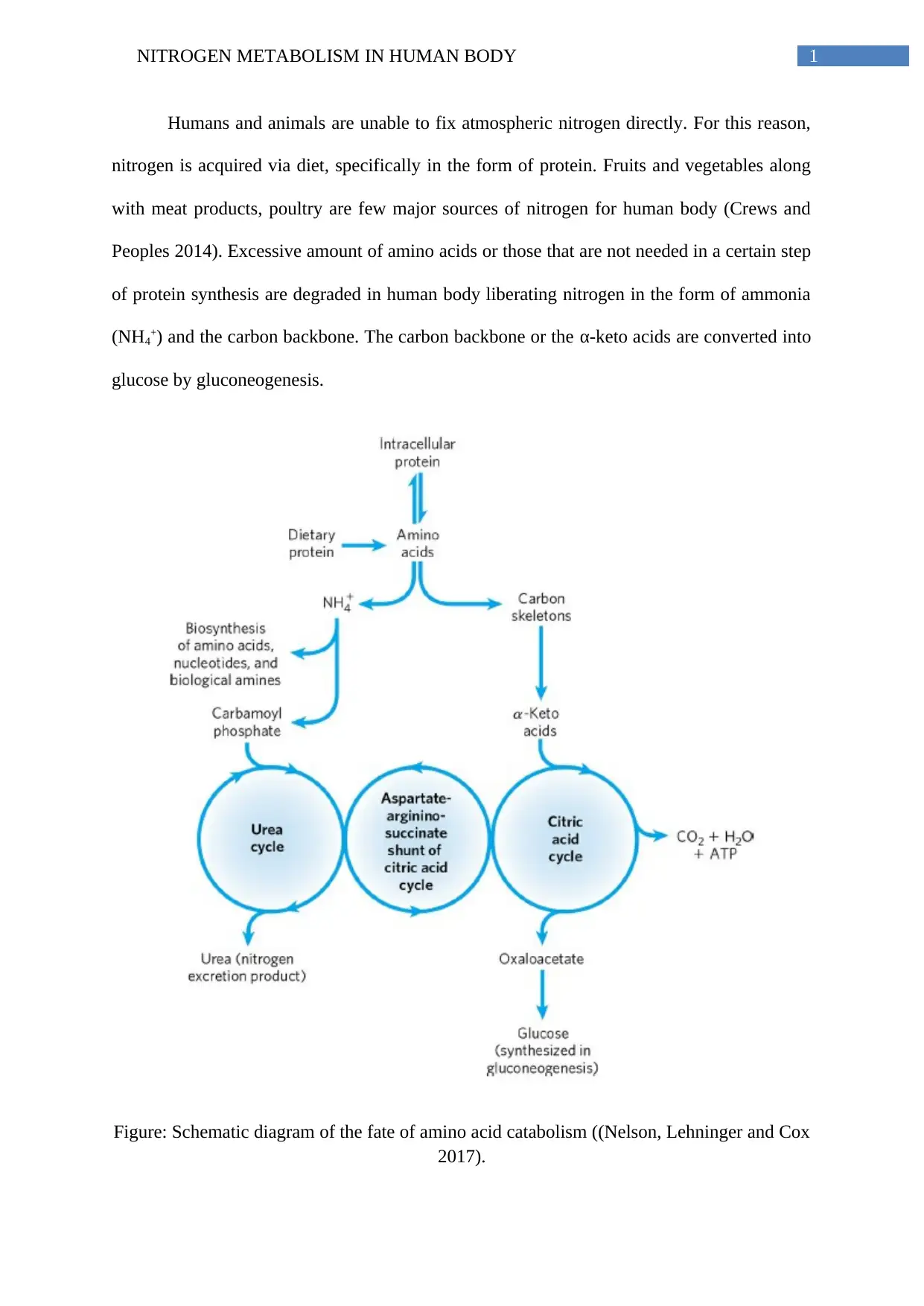

Humans and animals are unable to fix atmospheric nitrogen directly. For this reason,

nitrogen is acquired via diet, specifically in the form of protein. Fruits and vegetables along

with meat products, poultry are few major sources of nitrogen for human body (Crews and

Peoples 2014). Excessive amount of amino acids or those that are not needed in a certain step

of protein synthesis are degraded in human body liberating nitrogen in the form of ammonia

(NH4+) and the carbon backbone. The carbon backbone or the α-keto acids are converted into

glucose by gluconeogenesis.

Figure: Schematic diagram of the fate of amino acid catabolism ((Nelson, Lehninger and Cox

2017).

Humans and animals are unable to fix atmospheric nitrogen directly. For this reason,

nitrogen is acquired via diet, specifically in the form of protein. Fruits and vegetables along

with meat products, poultry are few major sources of nitrogen for human body (Crews and

Peoples 2014). Excessive amount of amino acids or those that are not needed in a certain step

of protein synthesis are degraded in human body liberating nitrogen in the form of ammonia

(NH4+) and the carbon backbone. The carbon backbone or the α-keto acids are converted into

glucose by gluconeogenesis.

Figure: Schematic diagram of the fate of amino acid catabolism ((Nelson, Lehninger and Cox

2017).

2NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

In case of humans, ingestion of dietary protein stimulates production of gastrin in

stomach. Gastrin induces release of hydrochloric acid by the parietal cells and pepsinogen

from the chief cells. The resulting gastric juice has an acidic pH, which denatures the

globular proteins and exposes the internal peptides for degradation by activated pepsin

(pepsinogen, a zymogen is converted into pepsin by autolytic cleavage). The acidic contents

of the stomach are delivered into pancreas, which stimulates secretin, a hormone responsible

for release of bi-carbonate resulting in an abrupt increase in pH (~pH 7). After reaching

duodenum, it causes release of cholecystokinin, which facilities production of pancreatic

enzymes like chymotrypsinogen, trypsinogen, procarboxypeptidase A, procarboxypeptidase

B from the exocrine cells. Intestinal enteropeptidase activates trypsinogen by converting it

into trypsin, which in turn activates proelastase, procarboxypeptidases and

chymotrypsinogen. Activated carboxypeptidases and aminopeptidases cleaves the amino acid

residues from carboxyl end and amino end respectively, along with selective cleavage by

trypsin and chymotrypsin, which produces monomeric amino acids. These amino acids are

absorbed by villi of the small intestine and transported to the liver, where they undergo

transamination (Barrett et al. 2009). Transfer of an amino group of an amino acid

(deamination) to α-keto glutarate involves specific transaminase and pyridoxal phosphate as a

cofactor, producing glutamate and the subsequent α-keto acid of the amino acid residue.

Glutamate is a key molecule, which could be utilized for nucleotide biosynthesis pathway

(anabolic) or to the excretory pathway (catabolic), according to physiological needs.

Glutamate produced in this abovementioned process travels from cytosol to the liver

mitochondria, where it undergoes oxidative deamination by glutamate dehydrogenase using

NAD+ or NADP+ as a cofactor. Variety of independent pathways contribute to the

accumulation of glutamate in the liver mitochondria. Glutamine derived from extrahepatic

tissues are converted to glutamate by glutaminase, oxaloacetate is converted to aspartate by

In case of humans, ingestion of dietary protein stimulates production of gastrin in

stomach. Gastrin induces release of hydrochloric acid by the parietal cells and pepsinogen

from the chief cells. The resulting gastric juice has an acidic pH, which denatures the

globular proteins and exposes the internal peptides for degradation by activated pepsin

(pepsinogen, a zymogen is converted into pepsin by autolytic cleavage). The acidic contents

of the stomach are delivered into pancreas, which stimulates secretin, a hormone responsible

for release of bi-carbonate resulting in an abrupt increase in pH (~pH 7). After reaching

duodenum, it causes release of cholecystokinin, which facilities production of pancreatic

enzymes like chymotrypsinogen, trypsinogen, procarboxypeptidase A, procarboxypeptidase

B from the exocrine cells. Intestinal enteropeptidase activates trypsinogen by converting it

into trypsin, which in turn activates proelastase, procarboxypeptidases and

chymotrypsinogen. Activated carboxypeptidases and aminopeptidases cleaves the amino acid

residues from carboxyl end and amino end respectively, along with selective cleavage by

trypsin and chymotrypsin, which produces monomeric amino acids. These amino acids are

absorbed by villi of the small intestine and transported to the liver, where they undergo

transamination (Barrett et al. 2009). Transfer of an amino group of an amino acid

(deamination) to α-keto glutarate involves specific transaminase and pyridoxal phosphate as a

cofactor, producing glutamate and the subsequent α-keto acid of the amino acid residue.

Glutamate is a key molecule, which could be utilized for nucleotide biosynthesis pathway

(anabolic) or to the excretory pathway (catabolic), according to physiological needs.

Glutamate produced in this abovementioned process travels from cytosol to the liver

mitochondria, where it undergoes oxidative deamination by glutamate dehydrogenase using

NAD+ or NADP+ as a cofactor. Variety of independent pathways contribute to the

accumulation of glutamate in the liver mitochondria. Glutamine derived from extrahepatic

tissues are converted to glutamate by glutaminase, oxaloacetate is converted to aspartate by

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

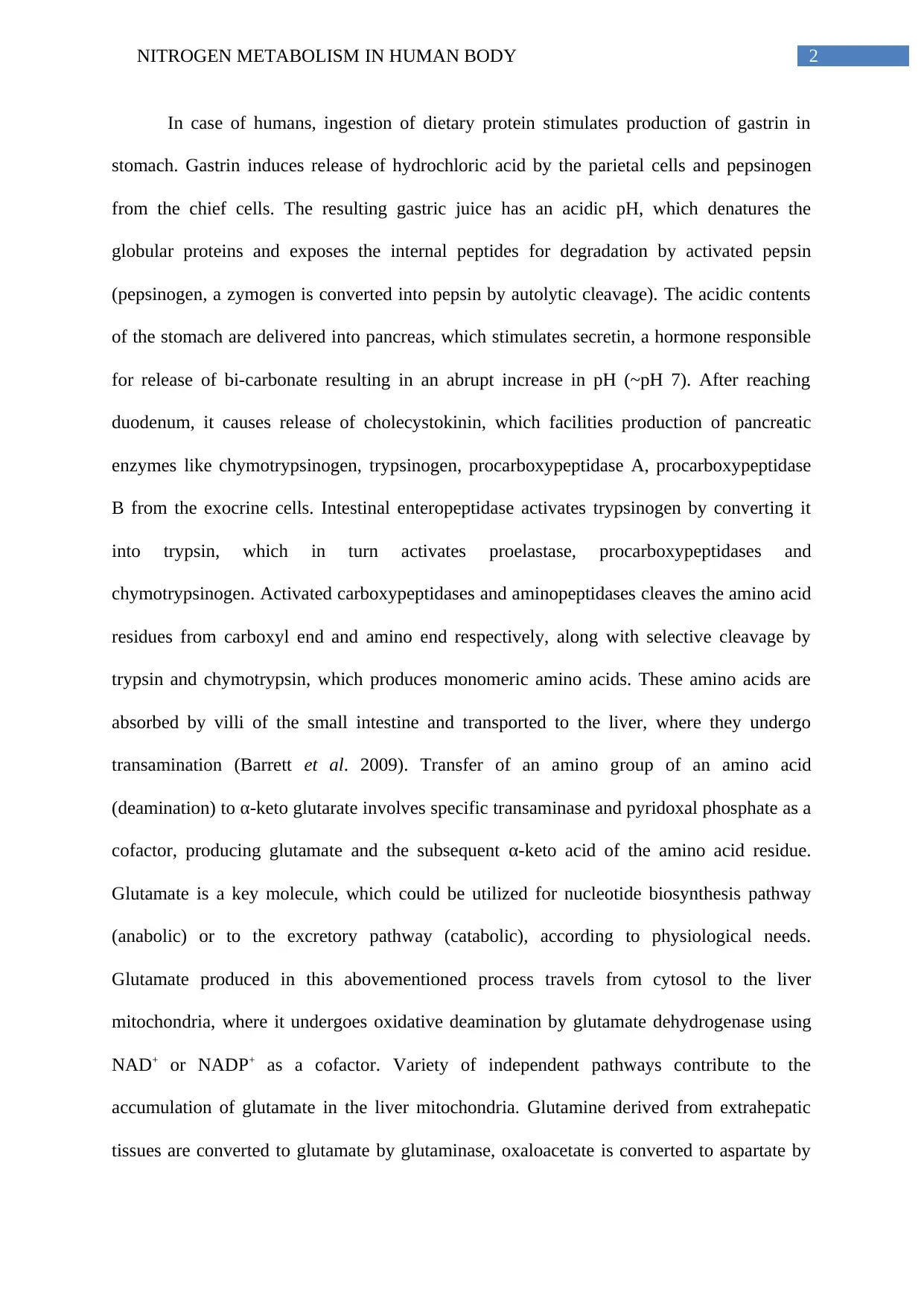

aspartate aminotransferase with subsequent transfer of the amino group to α-keto glutarate

producing glutamate (Bradford and McGivan 1973). Ammonia (NH4+) liberated by the action

of glutamate dehydrogenase is incorporated into bicarbonate with the use of 2 ATP molecules

and carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I, producing carbamoyl phosphate in the mitochondrial

matrix (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017).

Figure: Conversion of bicarbonate to carbamoyl phosphate, utilizing two ATP molecules as

energy (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017).

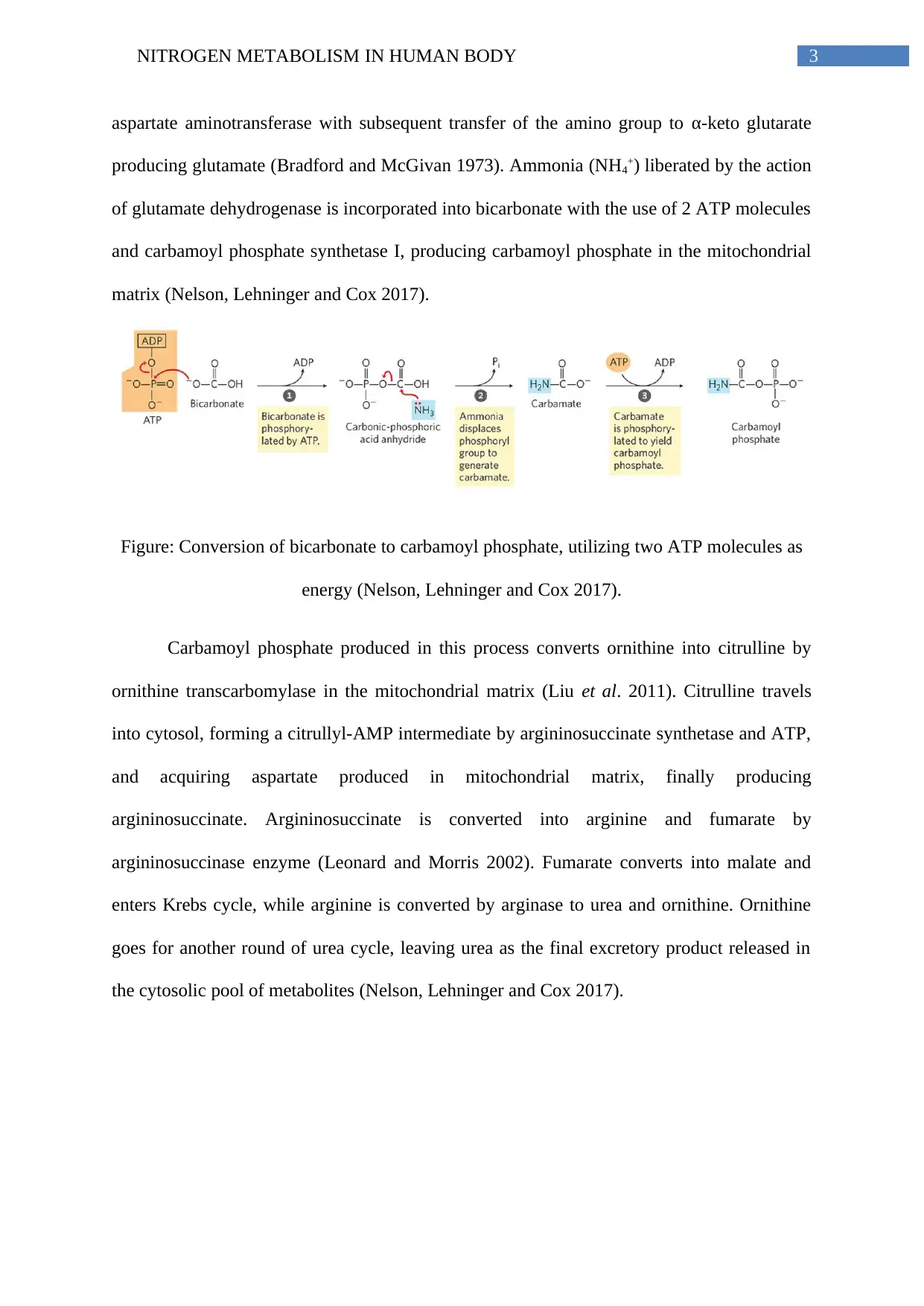

Carbamoyl phosphate produced in this process converts ornithine into citrulline by

ornithine transcarbomylase in the mitochondrial matrix (Liu et al. 2011). Citrulline travels

into cytosol, forming a citrullyl-AMP intermediate by argininosuccinate synthetase and ATP,

and acquiring aspartate produced in mitochondrial matrix, finally producing

argininosuccinate. Argininosuccinate is converted into arginine and fumarate by

argininosuccinase enzyme (Leonard and Morris 2002). Fumarate converts into malate and

enters Krebs cycle, while arginine is converted by arginase to urea and ornithine. Ornithine

goes for another round of urea cycle, leaving urea as the final excretory product released in

the cytosolic pool of metabolites (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017).

aspartate aminotransferase with subsequent transfer of the amino group to α-keto glutarate

producing glutamate (Bradford and McGivan 1973). Ammonia (NH4+) liberated by the action

of glutamate dehydrogenase is incorporated into bicarbonate with the use of 2 ATP molecules

and carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I, producing carbamoyl phosphate in the mitochondrial

matrix (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017).

Figure: Conversion of bicarbonate to carbamoyl phosphate, utilizing two ATP molecules as

energy (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017).

Carbamoyl phosphate produced in this process converts ornithine into citrulline by

ornithine transcarbomylase in the mitochondrial matrix (Liu et al. 2011). Citrulline travels

into cytosol, forming a citrullyl-AMP intermediate by argininosuccinate synthetase and ATP,

and acquiring aspartate produced in mitochondrial matrix, finally producing

argininosuccinate. Argininosuccinate is converted into arginine and fumarate by

argininosuccinase enzyme (Leonard and Morris 2002). Fumarate converts into malate and

enters Krebs cycle, while arginine is converted by arginase to urea and ornithine. Ornithine

goes for another round of urea cycle, leaving urea as the final excretory product released in

the cytosolic pool of metabolites (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

Figure: Diagrammatic representation of urea cycle (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017).

Fumarate produced in urea cycle is converted to malate by the cytosolic fumrase

enzyme producing malate, which travels inside the mitochondrial matrix as an intermediate

for Krebs Cycle. Several inner mitochondrial transporters like, malate α-ketoglutarate

Figure: Diagrammatic representation of urea cycle (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017).

Fumarate produced in urea cycle is converted to malate by the cytosolic fumrase

enzyme producing malate, which travels inside the mitochondrial matrix as an intermediate

for Krebs Cycle. Several inner mitochondrial transporters like, malate α-ketoglutarate

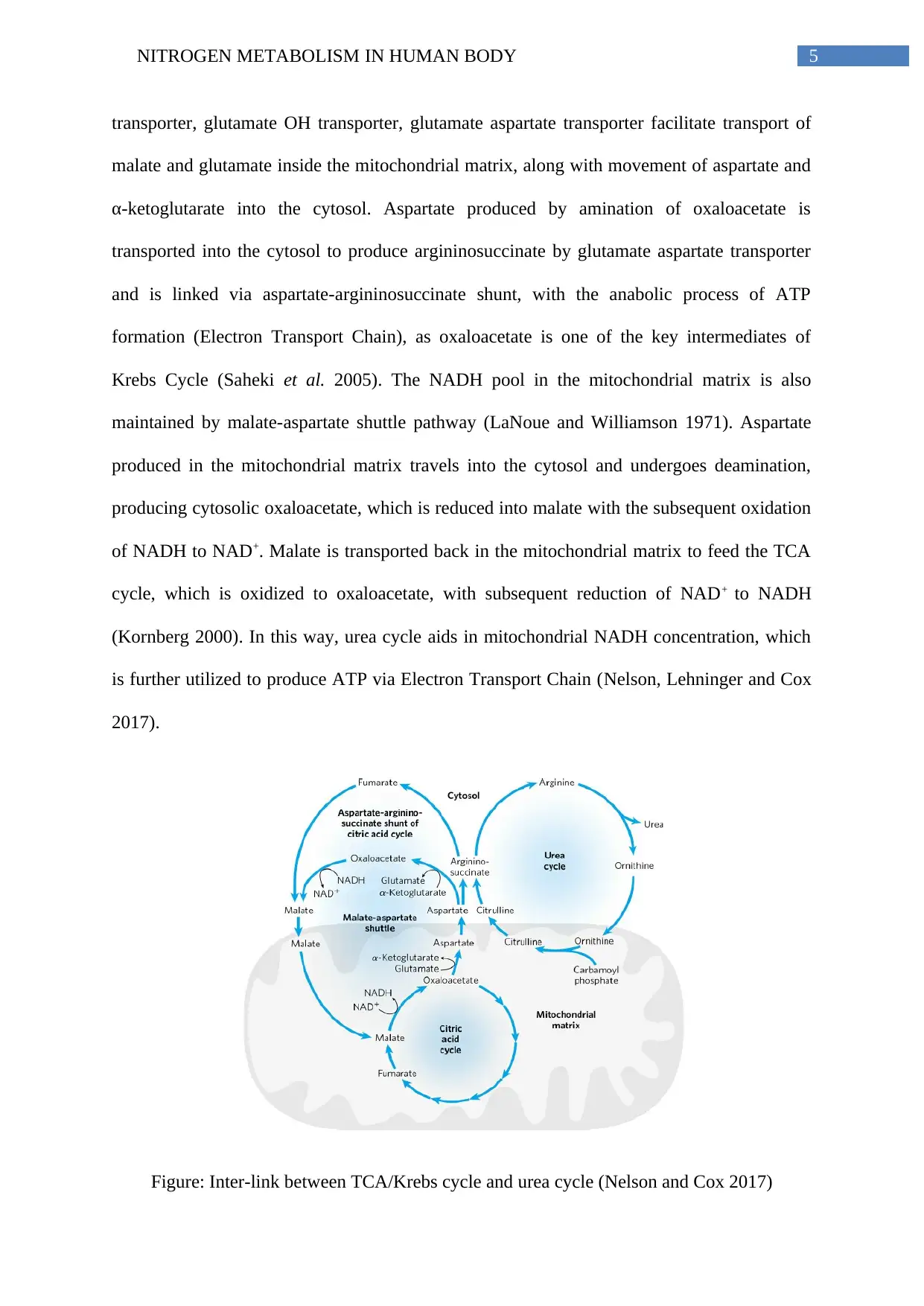

5NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

transporter, glutamate OH transporter, glutamate aspartate transporter facilitate transport of

malate and glutamate inside the mitochondrial matrix, along with movement of aspartate and

α-ketoglutarate into the cytosol. Aspartate produced by amination of oxaloacetate is

transported into the cytosol to produce argininosuccinate by glutamate aspartate transporter

and is linked via aspartate-argininosuccinate shunt, with the anabolic process of ATP

formation (Electron Transport Chain), as oxaloacetate is one of the key intermediates of

Krebs Cycle (Saheki et al. 2005). The NADH pool in the mitochondrial matrix is also

maintained by malate-aspartate shuttle pathway (LaNoue and Williamson 1971). Aspartate

produced in the mitochondrial matrix travels into the cytosol and undergoes deamination,

producing cytosolic oxaloacetate, which is reduced into malate with the subsequent oxidation

of NADH to NAD+. Malate is transported back in the mitochondrial matrix to feed the TCA

cycle, which is oxidized to oxaloacetate, with subsequent reduction of NAD+ to NADH

(Kornberg 2000). In this way, urea cycle aids in mitochondrial NADH concentration, which

is further utilized to produce ATP via Electron Transport Chain (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox

2017).

Figure: Inter-link between TCA/Krebs cycle and urea cycle (Nelson and Cox 2017)

transporter, glutamate OH transporter, glutamate aspartate transporter facilitate transport of

malate and glutamate inside the mitochondrial matrix, along with movement of aspartate and

α-ketoglutarate into the cytosol. Aspartate produced by amination of oxaloacetate is

transported into the cytosol to produce argininosuccinate by glutamate aspartate transporter

and is linked via aspartate-argininosuccinate shunt, with the anabolic process of ATP

formation (Electron Transport Chain), as oxaloacetate is one of the key intermediates of

Krebs Cycle (Saheki et al. 2005). The NADH pool in the mitochondrial matrix is also

maintained by malate-aspartate shuttle pathway (LaNoue and Williamson 1971). Aspartate

produced in the mitochondrial matrix travels into the cytosol and undergoes deamination,

producing cytosolic oxaloacetate, which is reduced into malate with the subsequent oxidation

of NADH to NAD+. Malate is transported back in the mitochondrial matrix to feed the TCA

cycle, which is oxidized to oxaloacetate, with subsequent reduction of NAD+ to NADH

(Kornberg 2000). In this way, urea cycle aids in mitochondrial NADH concentration, which

is further utilized to produce ATP via Electron Transport Chain (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox

2017).

Figure: Inter-link between TCA/Krebs cycle and urea cycle (Nelson and Cox 2017)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

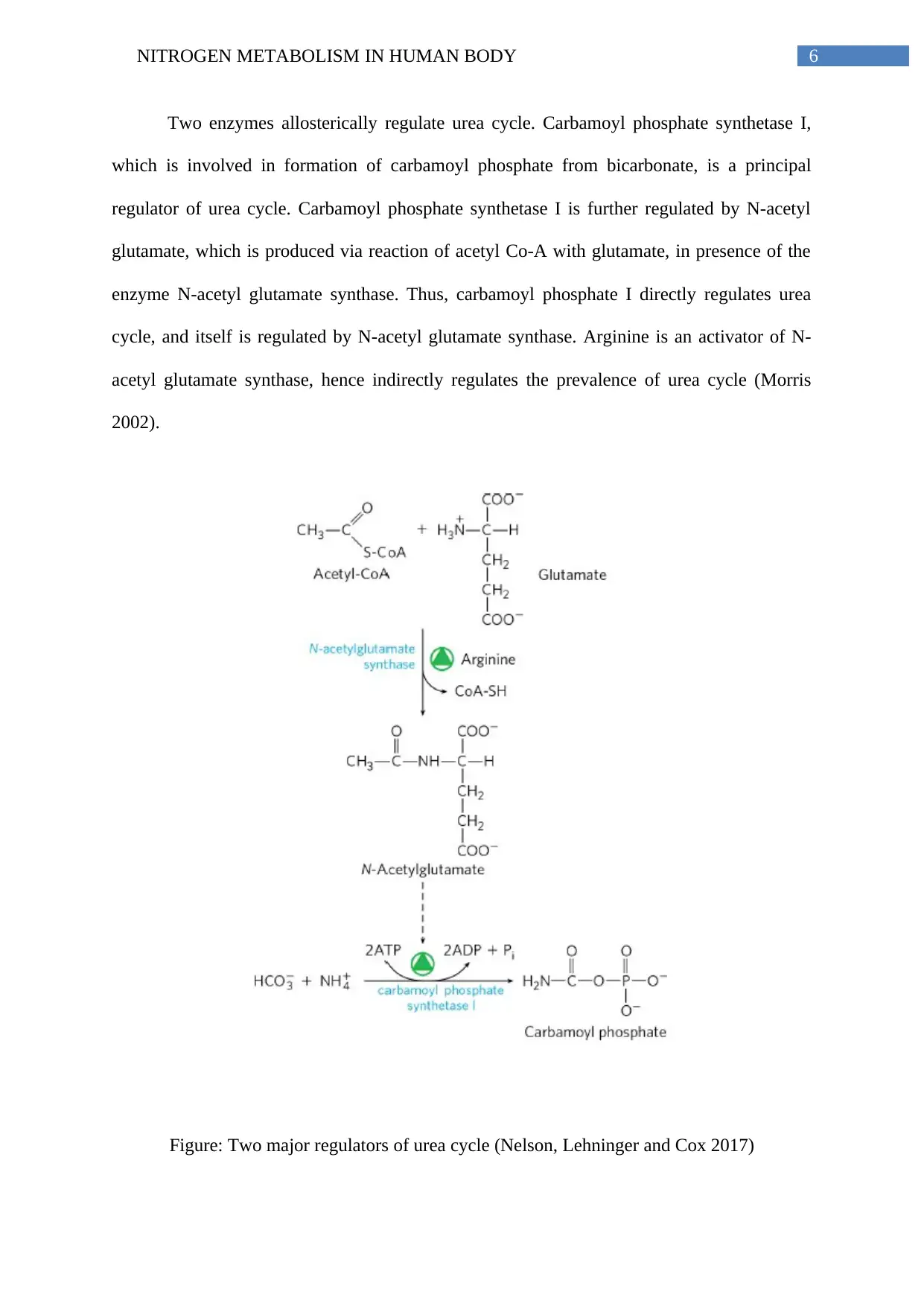

Two enzymes allosterically regulate urea cycle. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I,

which is involved in formation of carbamoyl phosphate from bicarbonate, is a principal

regulator of urea cycle. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I is further regulated by N-acetyl

glutamate, which is produced via reaction of acetyl Co-A with glutamate, in presence of the

enzyme N-acetyl glutamate synthase. Thus, carbamoyl phosphate I directly regulates urea

cycle, and itself is regulated by N-acetyl glutamate synthase. Arginine is an activator of N-

acetyl glutamate synthase, hence indirectly regulates the prevalence of urea cycle (Morris

2002).

Figure: Two major regulators of urea cycle (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017)

Two enzymes allosterically regulate urea cycle. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I,

which is involved in formation of carbamoyl phosphate from bicarbonate, is a principal

regulator of urea cycle. Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I is further regulated by N-acetyl

glutamate, which is produced via reaction of acetyl Co-A with glutamate, in presence of the

enzyme N-acetyl glutamate synthase. Thus, carbamoyl phosphate I directly regulates urea

cycle, and itself is regulated by N-acetyl glutamate synthase. Arginine is an activator of N-

acetyl glutamate synthase, hence indirectly regulates the prevalence of urea cycle (Morris

2002).

Figure: Two major regulators of urea cycle (Nelson, Lehninger and Cox 2017)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

References

Barrett, K.E., Barman, S.M., Boitano, S. and Brooks, H., 2009. Ganong’s review of medical

physiology. 23. NY: McGraw-Hill Medical.

Bradford, N.M. and McGivan, J.D., 1973. Quantitative characteristics of glutamate transport

in rat liver mitochondria. Biochemical Journal, 134(4), pp.1023-1029.

Crews, T.E. and Peoples, M.B., 2004. Legume versus fertilizer sources of nitrogen:

ecological tradeoffs and human needs. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment, 102(3),

pp.279-297.

Kornberg, H., 2000. Krebs and his trinity of cycles. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell

Biology, 1(3), p.225.

LaNoue, K.F. and Williamson, J.R., 1971. Interrelationships between malate-aspartate shuttle

and citric acid cycle in rat heart mitochondria. Metabolism, 20(2), pp.119-140.

Leonard, J.V. and Morris, A.A.M., 2002, February. Urea cycle disorders. In Seminars in

neonatology (Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 27-35). WB Saunders.

Liu, H., Dong, H., Robertson, K. and Liu, C., 2011. DNA methylation suppresses expression

of the urea cycle enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) in human hepatocellular

carcinoma. The American journal of pathology, 178(2), pp.652-661.

Morris Jr, S.M., 2002. Regulation of enzymes of the urea cycle and arginine

metabolism. Annual review of nutrition, 22(1), pp.87-105.

References

Barrett, K.E., Barman, S.M., Boitano, S. and Brooks, H., 2009. Ganong’s review of medical

physiology. 23. NY: McGraw-Hill Medical.

Bradford, N.M. and McGivan, J.D., 1973. Quantitative characteristics of glutamate transport

in rat liver mitochondria. Biochemical Journal, 134(4), pp.1023-1029.

Crews, T.E. and Peoples, M.B., 2004. Legume versus fertilizer sources of nitrogen:

ecological tradeoffs and human needs. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment, 102(3),

pp.279-297.

Kornberg, H., 2000. Krebs and his trinity of cycles. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell

Biology, 1(3), p.225.

LaNoue, K.F. and Williamson, J.R., 1971. Interrelationships between malate-aspartate shuttle

and citric acid cycle in rat heart mitochondria. Metabolism, 20(2), pp.119-140.

Leonard, J.V. and Morris, A.A.M., 2002, February. Urea cycle disorders. In Seminars in

neonatology (Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 27-35). WB Saunders.

Liu, H., Dong, H., Robertson, K. and Liu, C., 2011. DNA methylation suppresses expression

of the urea cycle enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) in human hepatocellular

carcinoma. The American journal of pathology, 178(2), pp.652-661.

Morris Jr, S.M., 2002. Regulation of enzymes of the urea cycle and arginine

metabolism. Annual review of nutrition, 22(1), pp.87-105.

8NITROGEN METABOLISM IN HUMAN BODY

Nelson, D.L., Lehninger, A.L. and Cox, M.M., 2017. Lehninger principles of biochemistry.

Macmillan.

Saheki, T., Kobayashi, K., Iijima, M., Moriyama, M., Yazaki, M., Takei, Y.I. and Ikeda, S.I.,

2005. Metabolic derangements in deficiency of citrin, a liver-type mitochondrial aspartate–

glutamate carrier. Hepatology research, 33(2), pp.181-184.

Nelson, D.L., Lehninger, A.L. and Cox, M.M., 2017. Lehninger principles of biochemistry.

Macmillan.

Saheki, T., Kobayashi, K., Iijima, M., Moriyama, M., Yazaki, M., Takei, Y.I. and Ikeda, S.I.,

2005. Metabolic derangements in deficiency of citrin, a liver-type mitochondrial aspartate–

glutamate carrier. Hepatology research, 33(2), pp.181-184.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 9

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.