Analysis of Australia's 'No Jab, No Pay' Policy & US Relevance

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/14

|2

|2153

|27

Report

AI Summary

This report examines Australia's 'No Jab, No Pay' legislation, which links families' eligibility for government welfare and benefits to the immunization status of their children. The policy, implemented to address low vaccination rates, denies benefits to families whose children are not up-to-date on their vaccinations, with limited medical exemptions. The report discusses the potential relevance, legality, and ethical considerations of such a program in the United States, where some state-based welfare programs already have similar links. While the Australian program has shown some success in increasing immunization rates, concerns remain about its disproportionate impact on low-income families and potential adverse consequences for children. The analysis concludes by considering the trade-offs and design details necessary for such a policy to be acceptable and effective in addressing gaps in immunization coverage.

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Linking Immunization Status and Eligibility

for Welfare and Benefits Payments

The Australian “No Jab, No Pay” Legislation

The recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable dis-

eases have refocused attention on the threat posed by

unvaccinated and undervaccinated individuals.1Gov-

ernments around the world have responded by strength-

ening laws and policies directed at increasing vaccina-

tion rates. The standard menu of options includes

education and information initiatives, incentives, and

mandates; these may be directed at the general public,

health care organizations, or practitioners.

The term mandate is somewhat misleading, because

there are exceptions1

—always on medical grounds, fre-

quently on religious grounds, and sometimes on philo-

sophical grounds. Moreover, the thrust of mandates is not

to forcibly require vaccination but to predicate eligibility

for a service or benefit on adherence to the recommended

immunizationscheduleofvaccination.IntheUnitedStates,

every state requires proof of immunization for entry into

public schools, and some states also have similar require-

ments for entry into day care facilities and private schools.

These requirements can seem coercive to families who do

not have other feasible schooling or child care options.

However, the logic and acceptability of these requirements

are rooted in the fact that the risks posed by clusters of non-

immunized children are heightened in these very settings.

In Australia, half of its 6 states and 2 territories have

vaccine requirements for school entry, and the 3 most

populous states (New South Wales,Victoria,and

Queensland) recently extended such requirements for

entry to kindergartens and child care facilities. These

rules overlay a more controversial policy: for nearly 20

years, the Australian government has linked families’ eli-

gibility for government welfare and benefits to chil-

dren’s vaccination status. In this Viewpoint, we de-

scribe a recent expansion of the Australian program and

consider the relevance, legality, and ethics of such an ap-

proach in the United States.

No Jab, No Pay

In the mid-1990s, vaccination rates were dangerously

low in Australia: only half of all children had the nation-

ally recommended immunization coverage. To address

the problem, the federal government implemented a

multipronged strategy that is widely regarded as hav-

ing been successful. The welfare incentive program was

one component of the strategy.

In 2015, a controversial new law— titled, “No Jab,

No Pay”—expanded the program and substantially in-

creased the incentives.2Effective January 1, 2016, fami-

lies’ eligibility for federal benefits worth up to US $15 000

per child per year (Table) depends on the immuniza-

tion status of all family members through 19 years of

age.2 The benefits are unavailable to families for each

year in which an otherwise eligible family member in this

age group does not have the recommended vaccines for

1-, 2-, and 5-year-olds or is not participating in an immu-

nization catch-up program.2 The law also ended “con-

scientious objections” as a basis for exemptions,2 fol-

lowing the termination of religious exemptions earlier in

the year. Only medical exemptions remain, which may

be granted after a physician attests to the existence of

a disqualifying condition, such as certain allergies and im-

munocompromising illnesses.

The government has projected a savings over 5 years

of US $380 million from the new law.3About half the es-

timated savings is expected to come from benefits not

paid, with an estimated 10 000 families expected to lose

eligibility for payments in 2016-2017 alone.3 Although

the effects of the law have yet to be formally evalu-

ated, the government recently announced that 5738 pre-

viously unvaccinated children in families receiving ben-

efits were immunized in the first 6 months of the new

law’s effective date, and 187 695 children who were lag-

ging on the recommended vaccination schedule had

caught up.4,5With a total of approximately 5 million chil-

dren in Australia, these are substantial shifts.

Existing Incentives for Welfare Beneficiaries

in the United States

In the United States, a number of state-based welfare

programs already link welfare payments to vaccination

status. For example, in California’s CalWORKs welfare

program, families who fail to submit up-to-date immu-

nization records or an exemption form for children

younger than 6 years risk losing part of their cash assis-

tance. Florida’s Temporary Cash Assistance program may

withhold benefits from families with children younger

than 5 years whose immunizations are not up to date.

At the federal level, the Special Supplemental Nutrition

Program for Women, Infants, and Children checks the im-

munization status of preschool children and encour-

ages adherence with the recommended schedule.

However, stern approaches such as these are not

widespread in the United States. Questions regarding

whether they are warranted, lawful, and ethically ac-

ceptable warrant attention.

Prospects of No Jab, No Pay in the United States

A program designed to increase adherence with immu-

nizations directed at welfare recipients would seem arbi-

trary, even discriminatory, unless vaccination rates in this

population were especially low. Various state and fed-

eral initiatives over the last 20 years, most notably the

VIEWPOINT

Y. Tony Yang, ScD,

LLM, MPH

Department of Health

Administration and

Policy, George Mason

University, Fairfax,

Virginia.

David M. Studdert,

LLB, ScD, MPH

Stanford University

School of Medicine and

Stanford Law School,

Stanford, California.

Corresponding

Author: Y. Tony Yang,

ScD, LLM, MPH,

Department of Health

Administration and

Policy, George Mason

University, MS: 1J3,

4400 University Dr,

Fairfax, VA 22030

(ytyang@gmu.edu).

Opinion

jama.com (Reprinted)JAMA February 28, 2017Volume 317, Number 8803

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/936072/ by a STANFORD Univ Med Center User on 03/02/2017

Linking Immunization Status and Eligibility

for Welfare and Benefits Payments

The Australian “No Jab, No Pay” Legislation

The recent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable dis-

eases have refocused attention on the threat posed by

unvaccinated and undervaccinated individuals.1Gov-

ernments around the world have responded by strength-

ening laws and policies directed at increasing vaccina-

tion rates. The standard menu of options includes

education and information initiatives, incentives, and

mandates; these may be directed at the general public,

health care organizations, or practitioners.

The term mandate is somewhat misleading, because

there are exceptions1

—always on medical grounds, fre-

quently on religious grounds, and sometimes on philo-

sophical grounds. Moreover, the thrust of mandates is not

to forcibly require vaccination but to predicate eligibility

for a service or benefit on adherence to the recommended

immunizationscheduleofvaccination.IntheUnitedStates,

every state requires proof of immunization for entry into

public schools, and some states also have similar require-

ments for entry into day care facilities and private schools.

These requirements can seem coercive to families who do

not have other feasible schooling or child care options.

However, the logic and acceptability of these requirements

are rooted in the fact that the risks posed by clusters of non-

immunized children are heightened in these very settings.

In Australia, half of its 6 states and 2 territories have

vaccine requirements for school entry, and the 3 most

populous states (New South Wales,Victoria,and

Queensland) recently extended such requirements for

entry to kindergartens and child care facilities. These

rules overlay a more controversial policy: for nearly 20

years, the Australian government has linked families’ eli-

gibility for government welfare and benefits to chil-

dren’s vaccination status. In this Viewpoint, we de-

scribe a recent expansion of the Australian program and

consider the relevance, legality, and ethics of such an ap-

proach in the United States.

No Jab, No Pay

In the mid-1990s, vaccination rates were dangerously

low in Australia: only half of all children had the nation-

ally recommended immunization coverage. To address

the problem, the federal government implemented a

multipronged strategy that is widely regarded as hav-

ing been successful. The welfare incentive program was

one component of the strategy.

In 2015, a controversial new law— titled, “No Jab,

No Pay”—expanded the program and substantially in-

creased the incentives.2Effective January 1, 2016, fami-

lies’ eligibility for federal benefits worth up to US $15 000

per child per year (Table) depends on the immuniza-

tion status of all family members through 19 years of

age.2 The benefits are unavailable to families for each

year in which an otherwise eligible family member in this

age group does not have the recommended vaccines for

1-, 2-, and 5-year-olds or is not participating in an immu-

nization catch-up program.2 The law also ended “con-

scientious objections” as a basis for exemptions,2 fol-

lowing the termination of religious exemptions earlier in

the year. Only medical exemptions remain, which may

be granted after a physician attests to the existence of

a disqualifying condition, such as certain allergies and im-

munocompromising illnesses.

The government has projected a savings over 5 years

of US $380 million from the new law.3About half the es-

timated savings is expected to come from benefits not

paid, with an estimated 10 000 families expected to lose

eligibility for payments in 2016-2017 alone.3 Although

the effects of the law have yet to be formally evalu-

ated, the government recently announced that 5738 pre-

viously unvaccinated children in families receiving ben-

efits were immunized in the first 6 months of the new

law’s effective date, and 187 695 children who were lag-

ging on the recommended vaccination schedule had

caught up.4,5With a total of approximately 5 million chil-

dren in Australia, these are substantial shifts.

Existing Incentives for Welfare Beneficiaries

in the United States

In the United States, a number of state-based welfare

programs already link welfare payments to vaccination

status. For example, in California’s CalWORKs welfare

program, families who fail to submit up-to-date immu-

nization records or an exemption form for children

younger than 6 years risk losing part of their cash assis-

tance. Florida’s Temporary Cash Assistance program may

withhold benefits from families with children younger

than 5 years whose immunizations are not up to date.

At the federal level, the Special Supplemental Nutrition

Program for Women, Infants, and Children checks the im-

munization status of preschool children and encour-

ages adherence with the recommended schedule.

However, stern approaches such as these are not

widespread in the United States. Questions regarding

whether they are warranted, lawful, and ethically ac-

ceptable warrant attention.

Prospects of No Jab, No Pay in the United States

A program designed to increase adherence with immu-

nizations directed at welfare recipients would seem arbi-

trary, even discriminatory, unless vaccination rates in this

population were especially low. Various state and fed-

eral initiatives over the last 20 years, most notably the

VIEWPOINT

Y. Tony Yang, ScD,

LLM, MPH

Department of Health

Administration and

Policy, George Mason

University, Fairfax,

Virginia.

David M. Studdert,

LLB, ScD, MPH

Stanford University

School of Medicine and

Stanford Law School,

Stanford, California.

Corresponding

Author: Y. Tony Yang,

ScD, LLM, MPH,

Department of Health

Administration and

Policy, George Mason

University, MS: 1J3,

4400 University Dr,

Fairfax, VA 22030

(ytyang@gmu.edu).

Opinion

jama.com (Reprinted)JAMA February 28, 2017Volume 317, Number 8803

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/936072/ by a STANFORD Univ Med Center User on 03/02/2017

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

national Vaccines for Children program,6 have substantially in-

creased the proportion of preschool children in low-income families

who receive recommended vaccinations. Nevertheless, low-income

remains a significant risk factor for incomplete immunization.6,7For

example, the 2015 National Immunization Survey indicated that

in households below the poverty level, the proportion of 19- to

35-month-old children with the recommended coverage across a

range of vaccines was 3 to 10 percentage points lower than among

children of the same age living in households above the poverty line.7

The association between low-income and undervaccination is some-

times obscured by the considerable attention focused on the large

number of nonmedical exemptions claimed by white, high-income

families.8It is debatable how much weight disproportionately low cov-

erage among children in low-income households should carry. Some

will argue that linking welfare eligibility to vaccination status remains

indefensible unless the government can demonstrate that lack of im-

munization is not due to problems of access or cost.

Two lines of jurisprudence in US law converge to support the con-

stitutionality of programs that condition welfare benefits on vaccina-

tion status. First, governments have long enjoyed broad legal author-

ity to require vaccinations in the name of public health.9 This authority

permits conditioning receipt of services (eg, public schooling) on ad-

herence and penalizing nonadherence. Second, because welfare pay-

ments are not a constitutionally protected right, governments have

considerable latitude in how they distribute those payments and are

permitted to make distinctions among recipients. Distinctions made

on the basis of constitutionally protected categories, such as race and

sex, are unlikely to survive judicial review. However, a broad distinc-

tion based on adherence with a clinically recommended vaccination

schedule likely would. To the best of our knowledge, the existing state

programs that link welfare payments to vaccination status have not

encountered serious legal challenge.

Conditioning welfare payments on vaccination status also pro-

vokes a number of ethical concerns. The policy disproportionately

affects the poor. Critics have also charged that it harms the very chil-

dren it is intended to help: in addition to missing the vaccination,

affected children experience adverse consequences from the re-

duction in financial support. Other objections point to undesirable

collateral effects, including victimizing “violators,” perpetuating dis-

advantage, fueling distrust of government and the public health

system, and unhelpfully drawing attention away from barriers to

vaccination such as lack of access, time, and education.

The realities of how choices about childhood vaccinations are

made complicate the ethical calculus. The fact that children may lose

benefits because of a decision their parents made is troubling. On

the other hand, if the law prompts parents who would not other-

wise have vaccinated their children to do so, those children avoid

risks their parents have imposed on them.

These are difficult trade-offs. For many, the question of accept-

ability may come down to details of program design, such as the ac-

cessibility and cost of the required vaccinations, how often pay-

ments are actually withheld, and how important a public health

problem immunization coverage is among the subgroups affected.

Conclusions

The sporadic reemergence of vaccine-preventable illnesses has ex-

posed gaps in the laws and policies that surround one of public

health’s most successful interventions. If outbreaks of vaccine-

preventable disease spread, state and federal governments could

be expected to consider strong measures to plug those gaps. The

Australian experience may be instructive. It may attract special in-

terest in places where immunization coverage among welfare-

dependent families is disproportionately low and themes of per-

sonal responsibility have strong political traction.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have

completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and

none were reported.

REFERENCES

1.Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, Omer

SB. Association between vaccine refusal and

vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States:

a review of measles and pertussis. JAMA. 2016;

315(11):1149-1158.

2. Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Social Services Legislation Amendment

(No Jab, No Pay) Bill 2015. http://www.aph.gov.au

/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills

_Search_Results/Result?bId=r5540. Accessed

January 27, 2017.

3. Klapdor M, Grove A. Parliament of the

Commonwealth of Australia website. ‘No Jab No

Pay’ and other immunisation measures. http://www

.aph.gov.au/about_parliament/parliamentary

_departments/parliamentary_library/pubs/rp

/budgetreview201516/vaccination#_ftn7. Published

May 2015. Accessed November 30, 2016.

4. Minister for Social Services. No jab, no pay

lifts immunisation rates. http://christianporter

.dss.gov.au/media-releases/no-jab-no-pay-lifts

-immunisation-rates. Published July 31, 2016.

Accessed November 30, 2016.

5. Minister for Social Services. Tasmania leads

childhood immunisation rate improvement

as indigenous immunisation rates soar.

http://christianporter.dss.gov.au/media-releases

/20161106-immunisation. Published November 6,

2016. Accessed November 30, 2016.

6. Lieu TA, Ray GT, Klein NP, Chung C, Kulldorff M.

Geographic clusters in underimmunization and

vaccine refusal. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):280-289.

7. Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA,

Dietz V. Vaccination coverage among children aged

19-35 months—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb

Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1065-1071.

8. Yang YT, Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Mello MM.

Sociodemographic predictors of vaccination

exemptions on the basis of personal belief in

California. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):172-177.

9. Jacobson v Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

197 US 11 (1905).

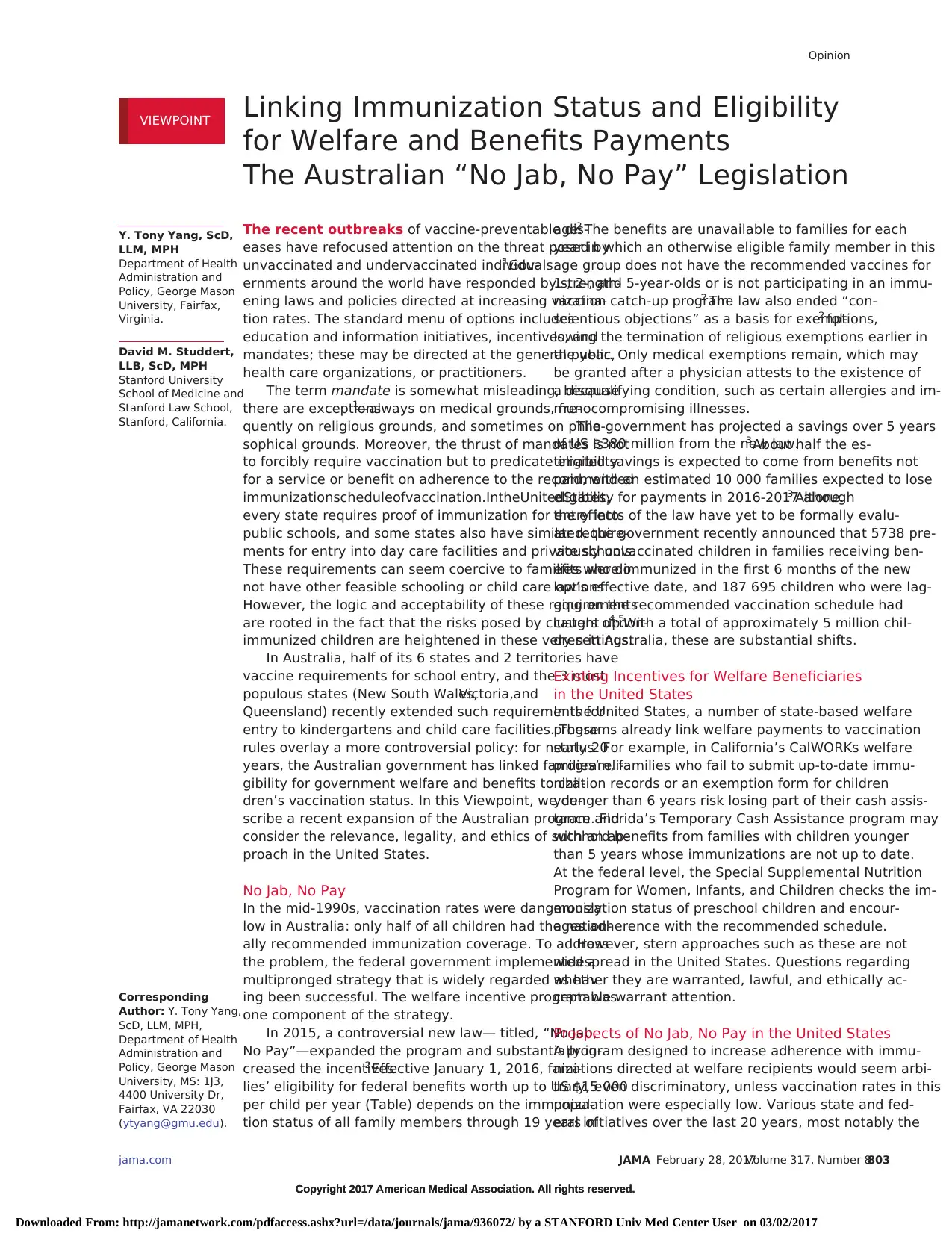

Table. Federal Benefits Conditioned on Children’s Immunization Status in Australia

Program Description Income Tested?

Value per Child

per Year in 2016, A$a

Child care benefit Helps meet costs of approved and registered care (eg, long-term, family,

or occasional day care; vacation care; preschool and kindergarten)

Yes ≤11 024

Child care rebate Covers 50% of out-of-pocket child care expenses for approved child care,

up to an annual limit per child

No ≤7500

Family tax benefit part A end-of-year

supplement (“family assistance payments”)

Payment to assist families with costs of raising children Yes ≤726

a Dollar amounts are current as of September 2016. Between December 1, 2015, and November 30, 2016, the Australian dollar averaged US $0.75.

Opinion Viewpoint

804 JAMA February 28, 2017Volume 317, Number 8(Reprinted) jama.com

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/936072/ by a STANFORD Univ Med Center User on 03/02/2017

national Vaccines for Children program,6 have substantially in-

creased the proportion of preschool children in low-income families

who receive recommended vaccinations. Nevertheless, low-income

remains a significant risk factor for incomplete immunization.6,7For

example, the 2015 National Immunization Survey indicated that

in households below the poverty level, the proportion of 19- to

35-month-old children with the recommended coverage across a

range of vaccines was 3 to 10 percentage points lower than among

children of the same age living in households above the poverty line.7

The association between low-income and undervaccination is some-

times obscured by the considerable attention focused on the large

number of nonmedical exemptions claimed by white, high-income

families.8It is debatable how much weight disproportionately low cov-

erage among children in low-income households should carry. Some

will argue that linking welfare eligibility to vaccination status remains

indefensible unless the government can demonstrate that lack of im-

munization is not due to problems of access or cost.

Two lines of jurisprudence in US law converge to support the con-

stitutionality of programs that condition welfare benefits on vaccina-

tion status. First, governments have long enjoyed broad legal author-

ity to require vaccinations in the name of public health.9 This authority

permits conditioning receipt of services (eg, public schooling) on ad-

herence and penalizing nonadherence. Second, because welfare pay-

ments are not a constitutionally protected right, governments have

considerable latitude in how they distribute those payments and are

permitted to make distinctions among recipients. Distinctions made

on the basis of constitutionally protected categories, such as race and

sex, are unlikely to survive judicial review. However, a broad distinc-

tion based on adherence with a clinically recommended vaccination

schedule likely would. To the best of our knowledge, the existing state

programs that link welfare payments to vaccination status have not

encountered serious legal challenge.

Conditioning welfare payments on vaccination status also pro-

vokes a number of ethical concerns. The policy disproportionately

affects the poor. Critics have also charged that it harms the very chil-

dren it is intended to help: in addition to missing the vaccination,

affected children experience adverse consequences from the re-

duction in financial support. Other objections point to undesirable

collateral effects, including victimizing “violators,” perpetuating dis-

advantage, fueling distrust of government and the public health

system, and unhelpfully drawing attention away from barriers to

vaccination such as lack of access, time, and education.

The realities of how choices about childhood vaccinations are

made complicate the ethical calculus. The fact that children may lose

benefits because of a decision their parents made is troubling. On

the other hand, if the law prompts parents who would not other-

wise have vaccinated their children to do so, those children avoid

risks their parents have imposed on them.

These are difficult trade-offs. For many, the question of accept-

ability may come down to details of program design, such as the ac-

cessibility and cost of the required vaccinations, how often pay-

ments are actually withheld, and how important a public health

problem immunization coverage is among the subgroups affected.

Conclusions

The sporadic reemergence of vaccine-preventable illnesses has ex-

posed gaps in the laws and policies that surround one of public

health’s most successful interventions. If outbreaks of vaccine-

preventable disease spread, state and federal governments could

be expected to consider strong measures to plug those gaps. The

Australian experience may be instructive. It may attract special in-

terest in places where immunization coverage among welfare-

dependent families is disproportionately low and themes of per-

sonal responsibility have strong political traction.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have

completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and

none were reported.

REFERENCES

1.Phadke VK, Bednarczyk RA, Salmon DA, Omer

SB. Association between vaccine refusal and

vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States:

a review of measles and pertussis. JAMA. 2016;

315(11):1149-1158.

2. Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Social Services Legislation Amendment

(No Jab, No Pay) Bill 2015. http://www.aph.gov.au

/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills

_Search_Results/Result?bId=r5540. Accessed

January 27, 2017.

3. Klapdor M, Grove A. Parliament of the

Commonwealth of Australia website. ‘No Jab No

Pay’ and other immunisation measures. http://www

.aph.gov.au/about_parliament/parliamentary

_departments/parliamentary_library/pubs/rp

/budgetreview201516/vaccination#_ftn7. Published

May 2015. Accessed November 30, 2016.

4. Minister for Social Services. No jab, no pay

lifts immunisation rates. http://christianporter

.dss.gov.au/media-releases/no-jab-no-pay-lifts

-immunisation-rates. Published July 31, 2016.

Accessed November 30, 2016.

5. Minister for Social Services. Tasmania leads

childhood immunisation rate improvement

as indigenous immunisation rates soar.

http://christianporter.dss.gov.au/media-releases

/20161106-immunisation. Published November 6,

2016. Accessed November 30, 2016.

6. Lieu TA, Ray GT, Klein NP, Chung C, Kulldorff M.

Geographic clusters in underimmunization and

vaccine refusal. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):280-289.

7. Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA,

Dietz V. Vaccination coverage among children aged

19-35 months—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb

Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1065-1071.

8. Yang YT, Delamater PL, Leslie TF, Mello MM.

Sociodemographic predictors of vaccination

exemptions on the basis of personal belief in

California. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):172-177.

9. Jacobson v Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

197 US 11 (1905).

Table. Federal Benefits Conditioned on Children’s Immunization Status in Australia

Program Description Income Tested?

Value per Child

per Year in 2016, A$a

Child care benefit Helps meet costs of approved and registered care (eg, long-term, family,

or occasional day care; vacation care; preschool and kindergarten)

Yes ≤11 024

Child care rebate Covers 50% of out-of-pocket child care expenses for approved child care,

up to an annual limit per child

No ≤7500

Family tax benefit part A end-of-year

supplement (“family assistance payments”)

Payment to assist families with costs of raising children Yes ≤726

a Dollar amounts are current as of September 2016. Between December 1, 2015, and November 30, 2016, the Australian dollar averaged US $0.75.

Opinion Viewpoint

804 JAMA February 28, 2017Volume 317, Number 8(Reprinted) jama.com

Copyright 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jamanetwork.com/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/jama/936072/ by a STANFORD Univ Med Center User on 03/02/2017

1 out of 2

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.