Detailed Case Analysis: Income Tax Computation, Deductions, and Laws

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/20

|10

|2425

|372

Case Study

AI Summary

This case study provides a detailed analysis of income tax computation, deductible donations, and relevant tax laws. It includes calculations for dividend credits and taxation service expenses, highlighting the importance of understanding tax regulations. The analysis also delves into the FCT vs Cooke and Sherdon case, examining its relevance in contemporary tax law. The document further explains assessable income, rental income taxation, and the treatment of fringe benefits, offering a comprehensive overview of income tax principles. Desklib is a platform where students can find similar solved assignments and study resources.

Case Analysis and Calculations 1

Case Analysis and Calculations

(Name)

Name

Affiliated Institute

Professor

Date

Case Analysis and Calculations

(Name)

Name

Affiliated Institute

Professor

Date

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Case Analysis and Calculations 2

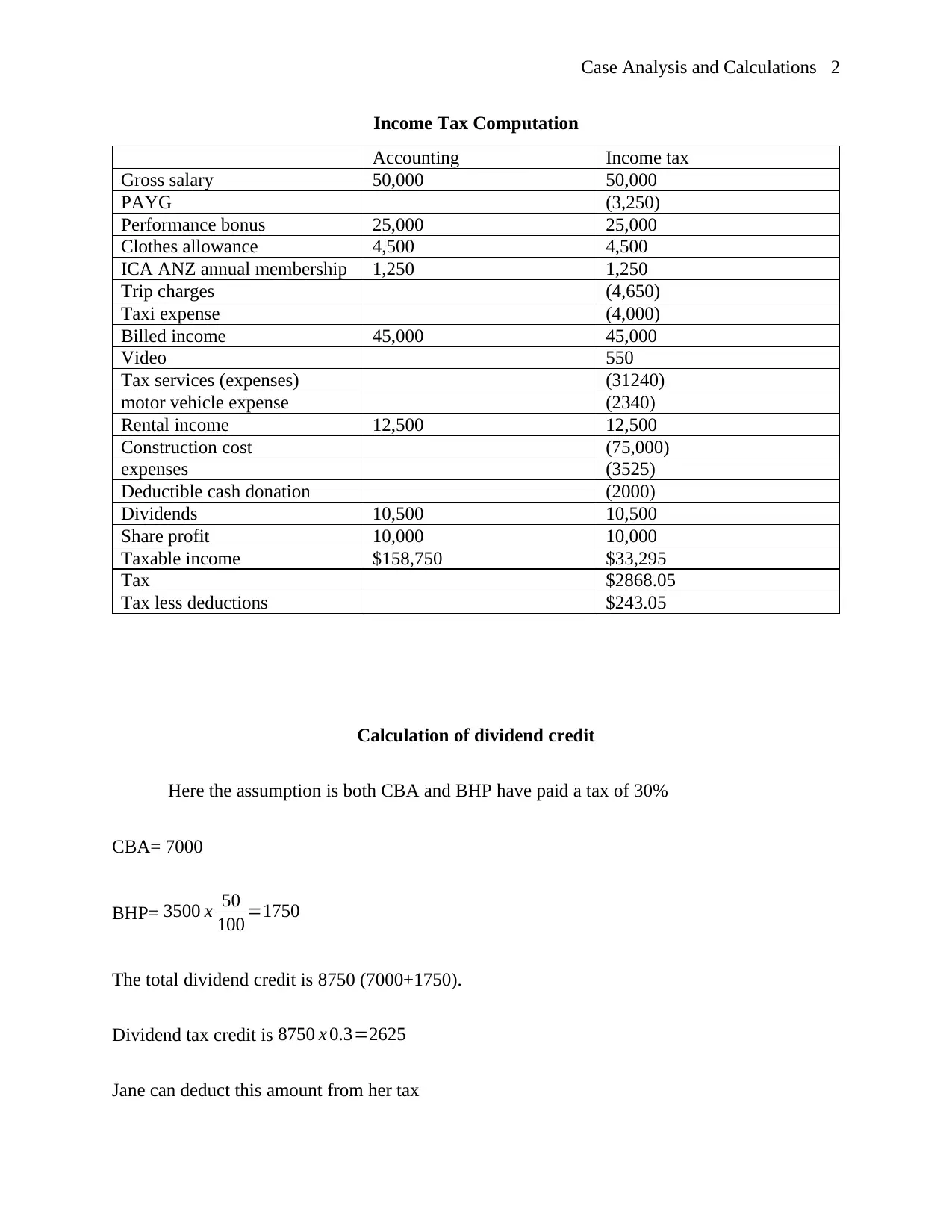

Income Tax Computation

Accounting Income tax

Gross salary 50,000 50,000

PAYG (3,250)

Performance bonus 25,000 25,000

Clothes allowance 4,500 4,500

ICA ANZ annual membership 1,250 1,250

Trip charges (4,650)

Taxi expense (4,000)

Billed income 45,000 45,000

Video 550

Tax services (expenses) (31240)

motor vehicle expense (2340)

Rental income 12,500 12,500

Construction cost (75,000)

expenses (3525)

Deductible cash donation (2000)

Dividends 10,500 10,500

Share profit 10,000 10,000

Taxable income $158,750 $33,295

Tax $2868.05

Tax less deductions $243.05

Calculation of dividend credit

Here the assumption is both CBA and BHP have paid a tax of 30%

CBA= 7000

BHP= 3500 x 50

100 =1750

The total dividend credit is 8750 (7000+1750).

Dividend tax credit is 8750 x 0.3=2625

Jane can deduct this amount from her tax

Income Tax Computation

Accounting Income tax

Gross salary 50,000 50,000

PAYG (3,250)

Performance bonus 25,000 25,000

Clothes allowance 4,500 4,500

ICA ANZ annual membership 1,250 1,250

Trip charges (4,650)

Taxi expense (4,000)

Billed income 45,000 45,000

Video 550

Tax services (expenses) (31240)

motor vehicle expense (2340)

Rental income 12,500 12,500

Construction cost (75,000)

expenses (3525)

Deductible cash donation (2000)

Dividends 10,500 10,500

Share profit 10,000 10,000

Taxable income $158,750 $33,295

Tax $2868.05

Tax less deductions $243.05

Calculation of dividend credit

Here the assumption is both CBA and BHP have paid a tax of 30%

CBA= 7000

BHP= 3500 x 50

100 =1750

The total dividend credit is 8750 (7000+1750).

Dividend tax credit is 8750 x 0.3=2625

Jane can deduct this amount from her tax

Case Analysis and Calculations 3

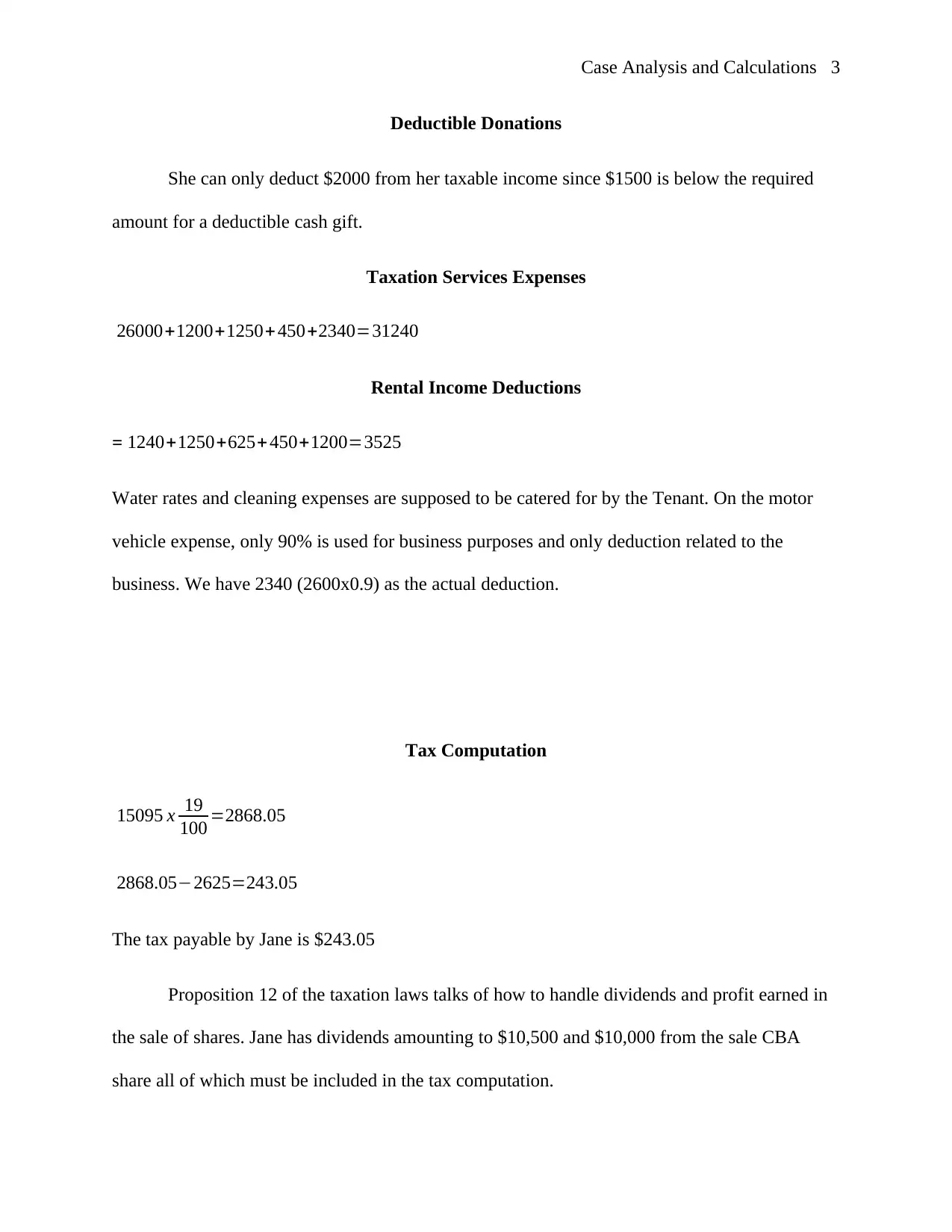

Deductible Donations

She can only deduct $2000 from her taxable income since $1500 is below the required

amount for a deductible cash gift.

Taxation Services Expenses

26000+1200+1250+ 450+2340=31240

Rental Income Deductions

= 1240+1250+625+ 450+1200=3525

Water rates and cleaning expenses are supposed to be catered for by the Tenant. On the motor

vehicle expense, only 90% is used for business purposes and only deduction related to the

business. We have 2340 (2600x0.9) as the actual deduction.

Tax Computation

15095 x 19

100 =2868.05

2868.05−2625=243.05

The tax payable by Jane is $243.05

Proposition 12 of the taxation laws talks of how to handle dividends and profit earned in

the sale of shares. Jane has dividends amounting to $10,500 and $10,000 from the sale CBA

share all of which must be included in the tax computation.

Deductible Donations

She can only deduct $2000 from her taxable income since $1500 is below the required

amount for a deductible cash gift.

Taxation Services Expenses

26000+1200+1250+ 450+2340=31240

Rental Income Deductions

= 1240+1250+625+ 450+1200=3525

Water rates and cleaning expenses are supposed to be catered for by the Tenant. On the motor

vehicle expense, only 90% is used for business purposes and only deduction related to the

business. We have 2340 (2600x0.9) as the actual deduction.

Tax Computation

15095 x 19

100 =2868.05

2868.05−2625=243.05

The tax payable by Jane is $243.05

Proposition 12 of the taxation laws talks of how to handle dividends and profit earned in

the sale of shares. Jane has dividends amounting to $10,500 and $10,000 from the sale CBA

share all of which must be included in the tax computation.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Case Analysis and Calculations 4

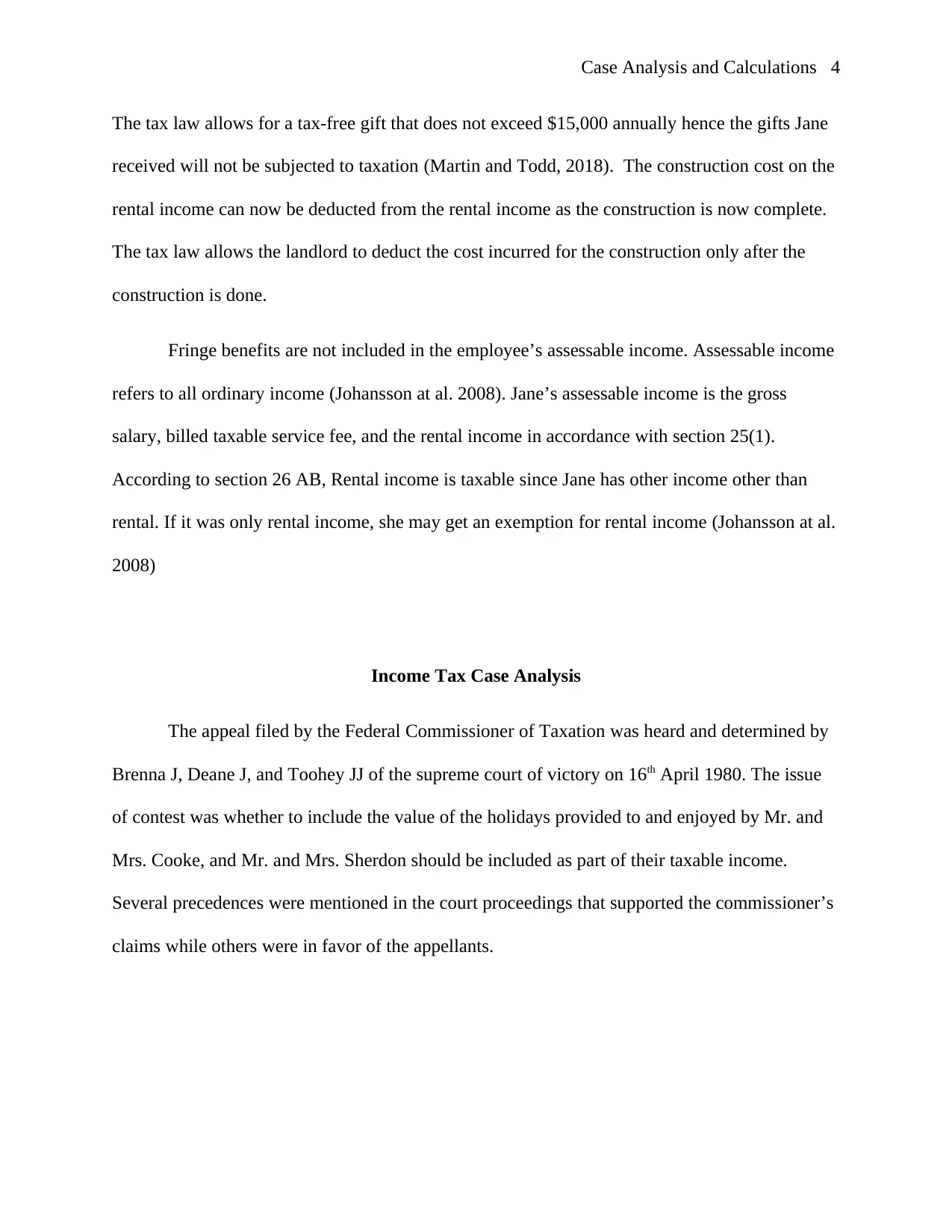

The tax law allows for a tax-free gift that does not exceed $15,000 annually hence the gifts Jane

received will not be subjected to taxation (Martin and Todd, 2018). The construction cost on the

rental income can now be deducted from the rental income as the construction is now complete.

The tax law allows the landlord to deduct the cost incurred for the construction only after the

construction is done.

Fringe benefits are not included in the employee’s assessable income. Assessable income

refers to all ordinary income (Johansson at al. 2008). Jane’s assessable income is the gross

salary, billed taxable service fee, and the rental income in accordance with section 25(1).

According to section 26 AB, Rental income is taxable since Jane has other income other than

rental. If it was only rental income, she may get an exemption for rental income (Johansson at al.

2008)

Income Tax Case Analysis

The appeal filed by the Federal Commissioner of Taxation was heard and determined by

Brenna J, Deane J, and Toohey JJ of the supreme court of victory on 16th April 1980. The issue

of contest was whether to include the value of the holidays provided to and enjoyed by Mr. and

Mrs. Cooke, and Mr. and Mrs. Sherdon should be included as part of their taxable income.

Several precedences were mentioned in the court proceedings that supported the commissioner’s

claims while others were in favor of the appellants.

The tax law allows for a tax-free gift that does not exceed $15,000 annually hence the gifts Jane

received will not be subjected to taxation (Martin and Todd, 2018). The construction cost on the

rental income can now be deducted from the rental income as the construction is now complete.

The tax law allows the landlord to deduct the cost incurred for the construction only after the

construction is done.

Fringe benefits are not included in the employee’s assessable income. Assessable income

refers to all ordinary income (Johansson at al. 2008). Jane’s assessable income is the gross

salary, billed taxable service fee, and the rental income in accordance with section 25(1).

According to section 26 AB, Rental income is taxable since Jane has other income other than

rental. If it was only rental income, she may get an exemption for rental income (Johansson at al.

2008)

Income Tax Case Analysis

The appeal filed by the Federal Commissioner of Taxation was heard and determined by

Brenna J, Deane J, and Toohey JJ of the supreme court of victory on 16th April 1980. The issue

of contest was whether to include the value of the holidays provided to and enjoyed by Mr. and

Mrs. Cooke, and Mr. and Mrs. Sherdon should be included as part of their taxable income.

Several precedences were mentioned in the court proceedings that supported the commissioner’s

claims while others were in favor of the appellants.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Case Analysis and Calculations 5

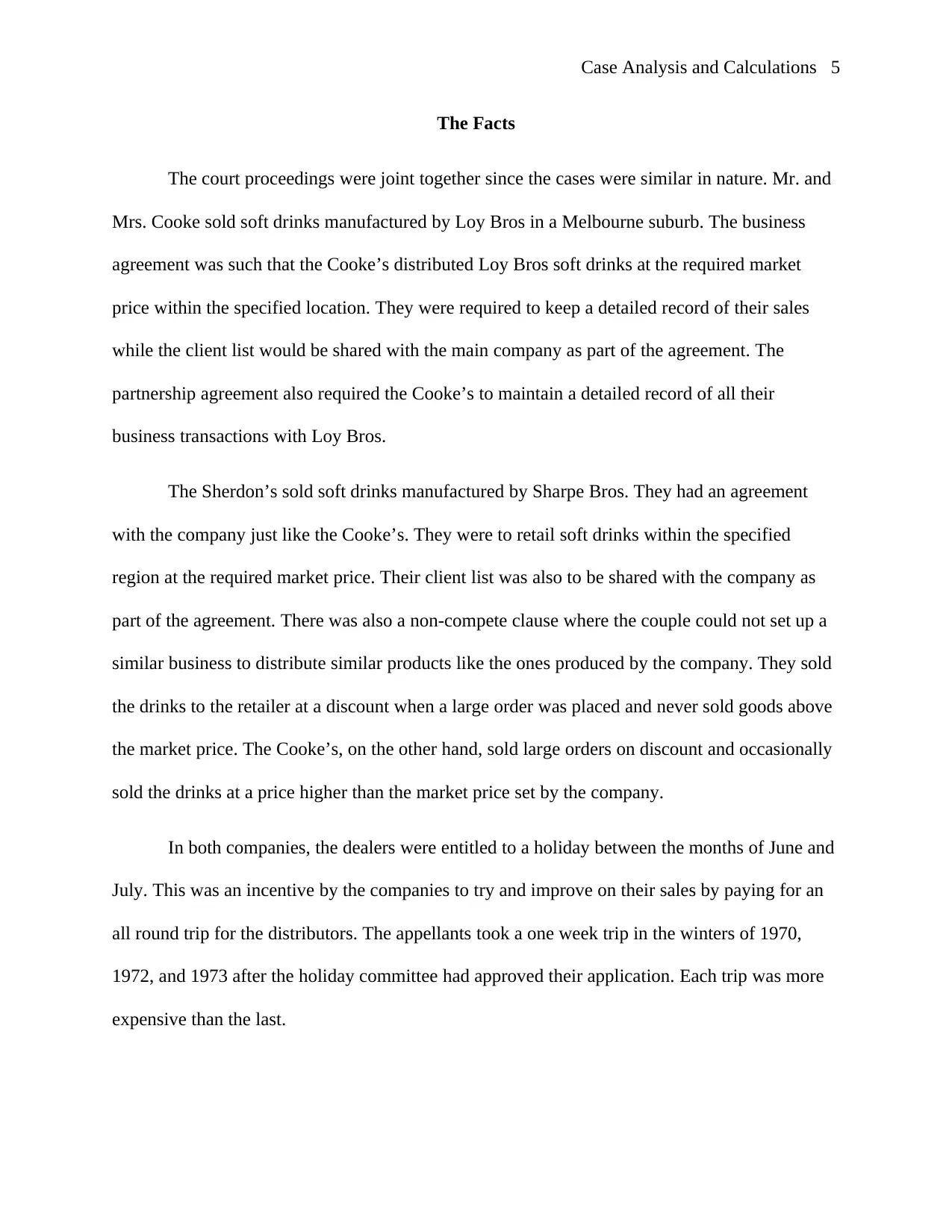

The Facts

The court proceedings were joint together since the cases were similar in nature. Mr. and

Mrs. Cooke sold soft drinks manufactured by Loy Bros in a Melbourne suburb. The business

agreement was such that the Cooke’s distributed Loy Bros soft drinks at the required market

price within the specified location. They were required to keep a detailed record of their sales

while the client list would be shared with the main company as part of the agreement. The

partnership agreement also required the Cooke’s to maintain a detailed record of all their

business transactions with Loy Bros.

The Sherdon’s sold soft drinks manufactured by Sharpe Bros. They had an agreement

with the company just like the Cooke’s. They were to retail soft drinks within the specified

region at the required market price. Their client list was also to be shared with the company as

part of the agreement. There was also a non-compete clause where the couple could not set up a

similar business to distribute similar products like the ones produced by the company. They sold

the drinks to the retailer at a discount when a large order was placed and never sold goods above

the market price. The Cooke’s, on the other hand, sold large orders on discount and occasionally

sold the drinks at a price higher than the market price set by the company.

In both companies, the dealers were entitled to a holiday between the months of June and

July. This was an incentive by the companies to try and improve on their sales by paying for an

all round trip for the distributors. The appellants took a one week trip in the winters of 1970,

1972, and 1973 after the holiday committee had approved their application. Each trip was more

expensive than the last.

The Facts

The court proceedings were joint together since the cases were similar in nature. Mr. and

Mrs. Cooke sold soft drinks manufactured by Loy Bros in a Melbourne suburb. The business

agreement was such that the Cooke’s distributed Loy Bros soft drinks at the required market

price within the specified location. They were required to keep a detailed record of their sales

while the client list would be shared with the main company as part of the agreement. The

partnership agreement also required the Cooke’s to maintain a detailed record of all their

business transactions with Loy Bros.

The Sherdon’s sold soft drinks manufactured by Sharpe Bros. They had an agreement

with the company just like the Cooke’s. They were to retail soft drinks within the specified

region at the required market price. Their client list was also to be shared with the company as

part of the agreement. There was also a non-compete clause where the couple could not set up a

similar business to distribute similar products like the ones produced by the company. They sold

the drinks to the retailer at a discount when a large order was placed and never sold goods above

the market price. The Cooke’s, on the other hand, sold large orders on discount and occasionally

sold the drinks at a price higher than the market price set by the company.

In both companies, the dealers were entitled to a holiday between the months of June and

July. This was an incentive by the companies to try and improve on their sales by paying for an

all round trip for the distributors. The appellants took a one week trip in the winters of 1970,

1972, and 1973 after the holiday committee had approved their application. Each trip was more

expensive than the last.

Case Analysis and Calculations 6

These holiday schemes were controlled by the manufacturers in the fact that the couple

could not sell or give away the trip tickets. Only two tickets were provided per dealer and they

were not transferable. The couples could derive any monetary value from selling the tickets. It is

either they went or they do not apply. Children above 12 years were not catered for by the

companies (Iknow.cch.com.au, 2019). Not every distributor qualified for the trips. Any

misconduct like the transfer of stock would lead to immediate disqualification by the committee.

The Arguments

The commissioner wanted the decision made to include the trip costs as part of the

appellant's income tax to be upheld based on section 25(1) and section (26e) of the Income Tax

Assessment Act of 1936 (Woellner et al, 2010). The argument was that the value of the holidays

constitute income according to the ordinary concept and it is a benefit given to taxpayers. This

could have been the case if the term Income was clearly defined in the tax law but it is not. The

definition relied upon was from the precedence, Jordan. C. J vs F.C of T (1935) which defines

income as “determined by the ordinary concept and usage of mankind.” Section 25 separates

gross income into assessable income and exempt income (Thampapillai, 2014). The Precedence,

Tennant vs Smith (1892) defines income to include what is received in the form of money.

Going by this precedence the trip benefits cannot be treated as income since there is no way of

getting any monetary benefit (Hoopes, Robinson, and Slemrod, 2018).

Section 6(1) of the Income Tax Act deals with income for personal use. It states that income

consists of earnings, salaries, wages, commissions, fees, bonuses, and pensions. Basically, it

defines income as any revenue generates from the sale of good and provision of services (Jones,

2017). At this point, it is important to note that the Cooke’s and the Sherdon’s are not employees

of the respective companies they are associated with. They are partners tasked with the

These holiday schemes were controlled by the manufacturers in the fact that the couple

could not sell or give away the trip tickets. Only two tickets were provided per dealer and they

were not transferable. The couples could derive any monetary value from selling the tickets. It is

either they went or they do not apply. Children above 12 years were not catered for by the

companies (Iknow.cch.com.au, 2019). Not every distributor qualified for the trips. Any

misconduct like the transfer of stock would lead to immediate disqualification by the committee.

The Arguments

The commissioner wanted the decision made to include the trip costs as part of the

appellant's income tax to be upheld based on section 25(1) and section (26e) of the Income Tax

Assessment Act of 1936 (Woellner et al, 2010). The argument was that the value of the holidays

constitute income according to the ordinary concept and it is a benefit given to taxpayers. This

could have been the case if the term Income was clearly defined in the tax law but it is not. The

definition relied upon was from the precedence, Jordan. C. J vs F.C of T (1935) which defines

income as “determined by the ordinary concept and usage of mankind.” Section 25 separates

gross income into assessable income and exempt income (Thampapillai, 2014). The Precedence,

Tennant vs Smith (1892) defines income to include what is received in the form of money.

Going by this precedence the trip benefits cannot be treated as income since there is no way of

getting any monetary benefit (Hoopes, Robinson, and Slemrod, 2018).

Section 6(1) of the Income Tax Act deals with income for personal use. It states that income

consists of earnings, salaries, wages, commissions, fees, bonuses, and pensions. Basically, it

defines income as any revenue generates from the sale of good and provision of services (Jones,

2017). At this point, it is important to note that the Cooke’s and the Sherdon’s are not employees

of the respective companies they are associated with. They are partners tasked with the

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Case Analysis and Calculations 7

distribution of goods with a payment for each product sold. The same section defines taxable

income in terms of assessable income and allowable deduction (Saad and Udin, 2016). Taxable

income in our case is the income earned from the distribution and sale of soft drinks less the

allowed deductions. The commissioner's claim was not supported by this section the financed

holiday was more of incentives to the distributors and they could not derive any cash benefits

from privileges they received.

Section 19 of the Taxation Act recognizes the precedence, Cross vs London and

Provincial Trust Ltd where income was defined to include the capital directed by the taxpayer on

how it is going to be spent without the taxpayer having any contact with the revenue. At this

point, the commissioner was trying to prove that the appellants had a participation in the revenue

used to sponsor the trip since they worked together with the manufacturers (Hartner et al. 2008).

This argument could have merit is the couples were given the chance to choose the destination

they wanted to visit. If this was also true in this case, there could have been no limitation as to

who gets to attend the trip which is one of the rules in the holiday scheme.

The appellants claimed that the trip was only an incentive for the work they had done in

service to the manufacturers. They derived no monetary benefit and received no revenue or cash

incentive during the holiday. They had no capability to turn the offered trip into money as it was

a restricted event where only the couple could attend. Given these facts, there was no standing

precedence where such an incentive was subjected to taxation. The commissioner had no legal

justification for adding the trip value as part of the appellant’s taxable income.

distribution of goods with a payment for each product sold. The same section defines taxable

income in terms of assessable income and allowable deduction (Saad and Udin, 2016). Taxable

income in our case is the income earned from the distribution and sale of soft drinks less the

allowed deductions. The commissioner's claim was not supported by this section the financed

holiday was more of incentives to the distributors and they could not derive any cash benefits

from privileges they received.

Section 19 of the Taxation Act recognizes the precedence, Cross vs London and

Provincial Trust Ltd where income was defined to include the capital directed by the taxpayer on

how it is going to be spent without the taxpayer having any contact with the revenue. At this

point, the commissioner was trying to prove that the appellants had a participation in the revenue

used to sponsor the trip since they worked together with the manufacturers (Hartner et al. 2008).

This argument could have merit is the couples were given the chance to choose the destination

they wanted to visit. If this was also true in this case, there could have been no limitation as to

who gets to attend the trip which is one of the rules in the holiday scheme.

The appellants claimed that the trip was only an incentive for the work they had done in

service to the manufacturers. They derived no monetary benefit and received no revenue or cash

incentive during the holiday. They had no capability to turn the offered trip into money as it was

a restricted event where only the couple could attend. Given these facts, there was no standing

precedence where such an incentive was subjected to taxation. The commissioner had no legal

justification for adding the trip value as part of the appellant’s taxable income.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Case Analysis and Calculations 8

The Decision.

The judges summarized that the respondents offered no service to the manufacturer but

their successful business sales advanced the manufacturers financial positions. These sales were

for the benefit of the respondent and they did so in the aim of fulfilling the contractual obligation

they had with the manufacturers. The issue of sharing their client's information with the

manufacturers was decided by the judges to be an obligation towards the agreement in their

respective contracts (Saad, 2014). The benefit could not be considered an income since it was not

convertible into money. The judges concluded that the appellants did not receive income as the

term is understood according to ordinary concepts and usage.

The Relevance of the Case Today

The set precedence in the case of FCT vs Cooke and Sherdon is only relevant under the

condition with which it was set. If a contract clearly states that partners are entitled to a paid

vacation, the revenue spend is part of the individual taxable income since it will be considered a

benefit of an association to a particular organization. Section 6 defines income for personal use

to include bonuses, pensions, and allowances. As long as an individual is employed in an

organization, all benefits are taxable in according to the income tax laws using the rates set by

Parliament (Burton, 2017). A similar case to that of FCT v Cooke and Sherdon would need to

use this ruling as long as the conditions in both cases are similar and clearly proven in a court of

law. The presiding judge would probably rule in favor of the appellant but only if the standards

set in this case proceedings are met.

The Decision.

The judges summarized that the respondents offered no service to the manufacturer but

their successful business sales advanced the manufacturers financial positions. These sales were

for the benefit of the respondent and they did so in the aim of fulfilling the contractual obligation

they had with the manufacturers. The issue of sharing their client's information with the

manufacturers was decided by the judges to be an obligation towards the agreement in their

respective contracts (Saad, 2014). The benefit could not be considered an income since it was not

convertible into money. The judges concluded that the appellants did not receive income as the

term is understood according to ordinary concepts and usage.

The Relevance of the Case Today

The set precedence in the case of FCT vs Cooke and Sherdon is only relevant under the

condition with which it was set. If a contract clearly states that partners are entitled to a paid

vacation, the revenue spend is part of the individual taxable income since it will be considered a

benefit of an association to a particular organization. Section 6 defines income for personal use

to include bonuses, pensions, and allowances. As long as an individual is employed in an

organization, all benefits are taxable in according to the income tax laws using the rates set by

Parliament (Burton, 2017). A similar case to that of FCT v Cooke and Sherdon would need to

use this ruling as long as the conditions in both cases are similar and clearly proven in a court of

law. The presiding judge would probably rule in favor of the appellant but only if the standards

set in this case proceedings are met.

Case Analysis and Calculations 9

References.

Burton, M., 2017. A Review of Judicial References to the Dictum of Jordan CJ, Expressed in

Scott v. Commissioner of Taxation, in Elaborating the Meaning of Income for the Purposes of

the Australian Income Tax. Australian Taxation, 19, p.50.

Hartner, M., Rechberger, S., Kirchler, E. and Schabmann, A., 2008. Procedural fairness and tax

compliance. Economic analysis and policy, 38(1), p.137.

Hoopes, J.L., Robinson, L. and Slemrod, J., 2018. Public tax-return disclosure. Journal of

Accounting and Economics. (Vol. 20, p.66)

Iknow.cch.com.au. (2019). CCH iKnow | Australian Tax & Accounting. [online] Available at:

https://iknow.cch.com.au/document/atagUio552255sl16866643/federal-commissioner-of-

taxation-v-cooke-and-sherden [Accessed 13 Feb. 2019].

Johansson, Å. Heady, C., Arnold, J., Brys, B., and Vartia, L., 2008. Taxation and economic

growth, P.25

Jones, D., 2017. Mid-market focus: Income or capital?: Taxpayer draws a blank. Taxation in

Australia, 51(7), p.357.

Martin, F. and Todd, T.M., 2018, August. The income tax exemption of charities and the tax

deductibility of charitable donations: the United States and Australia compared. In Australian

Tax Forum (Vol. 33, No. 4).

Martin, F., 2018. The major tax concessions granted to charities in Australia, New Zealand,

England, the United States of America and Hong Kong: what lessons can we learn?. In Research

Handbook on Not-For-Profit Law. Edward Elgar Publishing.

References.

Burton, M., 2017. A Review of Judicial References to the Dictum of Jordan CJ, Expressed in

Scott v. Commissioner of Taxation, in Elaborating the Meaning of Income for the Purposes of

the Australian Income Tax. Australian Taxation, 19, p.50.

Hartner, M., Rechberger, S., Kirchler, E. and Schabmann, A., 2008. Procedural fairness and tax

compliance. Economic analysis and policy, 38(1), p.137.

Hoopes, J.L., Robinson, L. and Slemrod, J., 2018. Public tax-return disclosure. Journal of

Accounting and Economics. (Vol. 20, p.66)

Iknow.cch.com.au. (2019). CCH iKnow | Australian Tax & Accounting. [online] Available at:

https://iknow.cch.com.au/document/atagUio552255sl16866643/federal-commissioner-of-

taxation-v-cooke-and-sherden [Accessed 13 Feb. 2019].

Johansson, Å. Heady, C., Arnold, J., Brys, B., and Vartia, L., 2008. Taxation and economic

growth, P.25

Jones, D., 2017. Mid-market focus: Income or capital?: Taxpayer draws a blank. Taxation in

Australia, 51(7), p.357.

Martin, F. and Todd, T.M., 2018, August. The income tax exemption of charities and the tax

deductibility of charitable donations: the United States and Australia compared. In Australian

Tax Forum (Vol. 33, No. 4).

Martin, F., 2018. The major tax concessions granted to charities in Australia, New Zealand,

England, the United States of America and Hong Kong: what lessons can we learn?. In Research

Handbook on Not-For-Profit Law. Edward Elgar Publishing.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Case Analysis and Calculations 10

Saad, N. and Udin, N. (2016). Public Rulings as Explanatory Materials to the Income Tax Act

1967: Readability Assessment. Advanced Science Letters, 22(5), pp.1448-1451.

Saad, N., 2014. Tax knowledge, tax complexity, and tax compliance: Taxpayers’

view. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, pp.1069-1075.

Thampapillai, D. (2014). The Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 S23AG and Double Tax

Avoidance Agreements. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Woellner, R.H., Barkoczy, S., Murphy, S., Evans, C. and Pinto, D., 2010. Australian taxation

law. CCH Australia.

Saad, N. and Udin, N. (2016). Public Rulings as Explanatory Materials to the Income Tax Act

1967: Readability Assessment. Advanced Science Letters, 22(5), pp.1448-1451.

Saad, N., 2014. Tax knowledge, tax complexity, and tax compliance: Taxpayers’

view. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, pp.1069-1075.

Thampapillai, D. (2014). The Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 S23AG and Double Tax

Avoidance Agreements. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Woellner, R.H., Barkoczy, S., Murphy, S., Evans, C. and Pinto, D., 2010. Australian taxation

law. CCH Australia.

1 out of 10

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.