Industrial Marketing Management: SCM Framework Progress and Potential

VerifiedAdded on 2023/02/01

|16

|18296

|35

Report

AI Summary

This report analyzes the advancements and potential of the Supply Chain Management (SCM) framework, originally proposed by Lambert and Cooper in 2000. It examines the evolution of the framework, which focuses on integrating key business processes across firms to create a competitive advantage. The report reviews the progress made in SCM research, including the development and implementation of eight cross-functional, cross-firm processes. It highlights the importance of managing relationships within a network of companies and provides insights into how managers can benefit from using the framework. The analysis covers an updated definition of SCM, an evaluation of its role in competition, the significance of relationship management, and the tools used to structure key supply chain relationships. Furthermore, the report explores the current state of the SCM framework, revised process descriptions, implementation guidelines, and process assessment tools, comparing it with the Supply Chain Operating Reference (SCOR) model. The paper concludes with opportunities for future research and offers a comprehensive overview of the SCM framework's progress and potential within industrial marketing.

Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential

Douglas M. Lamberta,

⁎, Matias G. Enzb

a Fisher College of Business, 506A Fisher Hall, 2100 Neil Avenue Columbus, The Ohio State University, OH 43210, United States

b Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Argentina

a b s t r a c ta r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 23 August 2016

Received in revised form 12 October 2016

Accepted 1 December 2016

Available online xxxx

In a 2000 article in Industrial Marketing Management, “Issues in Supply Chain Management,” Lambert and C

presented a framework for Supply Chain Management (SCM) as well as issues related to how it should be im

mented and directions for future research. The framework was comprised of eight cross-functional, cross- fir

business processes that could be used as a new way to manage relationships with suppliers and customers.

was based on research conducted by a team of academic researchers working with a group of executives fr

non-competing firms that had been meeting regularly since 1992 with the objective of improving SCM theor

and practice. The research has continued for the past 16 years and now covers a total of 25 years. In this pa

we review the progress that has been made in the development and implementation of the proposed SCM f

work since 2000 and identify opportunities for further research.

© 2016 Published by Elsevier Inc.

1. Introduction

In this journal in 2000, a Supply Chain Management (SCM) frame-

work was presented as a new business model and a way to create com-

petitive advantage by strategically managing relationships with key

customers and suppliers (Lambert & Cooper,2000).It was based on

the idea that organizations do not compete as solely autonomous enti-

ties but as members of a network of companies (Anderson,

Hakansson, & Johanson, 1994). In fact, it is common that companies pur-

chase from many of the same suppliers and sell to the same customers,

so the organizations that win more often are those that best manage

these relationships. In order to successfully manage key relationships

across a network of companies, the authors proposed a framework com-

prised of eight cross-functional, cross-firm processes. Implementation

of the processes requires the involvement of all business functions.

Sixteen years have gone by since the 2000 SCM article in Industrial

Marketing Management and the terms supply chain and SCM have be-

come common in the corporate world and in academic research

(Varoutsa & Scapens,2015).However,there is still not a consensus

view of what SCM involves or how it should be implemented (Vallet-

Bellmunt, Martínez-Fernández,& Capó-Vicedo, 2011). Given the

number of university programs devoted to SCM (many with specialized

research centers on the topic), it is startling there are only two cross-

functional, cross-firm, process-based frameworks that can be,and

have been,implemented in major corporations (Lambert,García-

Dastugue, & Croxton,2005): The Supply Chain Operations Reference

(SCOR) model developed and endorsed by the Supply-Chain Council

(now part of The American Production and Inventory Control Society),

and the SCM framework described by Lambert and Cooper (2000).

While many areas for research still exist, the research team led by

the first author of the 2000 article has addressed many of the research

questions raised in that article. The results of 16 years of research devo

ed to further development of the framework have been reported in a

total of 30 publications including two books, one in the fourth edition.

Our purpose in this article is to summarize the progress made, describe

how managers can benefit from using the framework and identify op-

portunities for further research. In the next section, we provide a sum-

mary of the contributions to SCM made by Lambert and Cooper

(2000). This is followed by a description of the research priorities that

the executive members identified since the early days of the research

center1 and a timeline of the publications that resulted from the re-

search. Then, the methodologies used to refine and extend the original

SCM framework since 2000 are described.Next, we provide the re-

search findings including: an updated definition of SCM; an evaluation

of the premise that the new basis for competition is supply chain vs.

supply chain; an explanation of why supply chain management is

about relationship management; a description of two tools that can be

used to structure key supply chain relationships; an overview of supply

chain mapping; and, a summary of changes to the original supply chain

framework described in the 2000 article. This is followed by a section on

the SCM framework in 2016 which includes: a description of the current

state of the SCM framework; revised process descriptions and figures;

guidelines for implementing the SCM processes; findings on value co-

Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: lambert.119@osu.edu (D.M. Lambert).

1 The research center involves executives from non-competing firms and academics

who have been meeting regularly since 1992 with the objective of improving SCM theory

and practice.

IMM-07437; No of Pages 16

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

0019-8501/© 2016 Published by Elsevier Inc.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Industrial Marketing Management

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing M

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

Douglas M. Lamberta,

⁎, Matias G. Enzb

a Fisher College of Business, 506A Fisher Hall, 2100 Neil Avenue Columbus, The Ohio State University, OH 43210, United States

b Universidad Nacional de Rosario, Argentina

a b s t r a c ta r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 23 August 2016

Received in revised form 12 October 2016

Accepted 1 December 2016

Available online xxxx

In a 2000 article in Industrial Marketing Management, “Issues in Supply Chain Management,” Lambert and C

presented a framework for Supply Chain Management (SCM) as well as issues related to how it should be im

mented and directions for future research. The framework was comprised of eight cross-functional, cross- fir

business processes that could be used as a new way to manage relationships with suppliers and customers.

was based on research conducted by a team of academic researchers working with a group of executives fr

non-competing firms that had been meeting regularly since 1992 with the objective of improving SCM theor

and practice. The research has continued for the past 16 years and now covers a total of 25 years. In this pa

we review the progress that has been made in the development and implementation of the proposed SCM f

work since 2000 and identify opportunities for further research.

© 2016 Published by Elsevier Inc.

1. Introduction

In this journal in 2000, a Supply Chain Management (SCM) frame-

work was presented as a new business model and a way to create com-

petitive advantage by strategically managing relationships with key

customers and suppliers (Lambert & Cooper,2000).It was based on

the idea that organizations do not compete as solely autonomous enti-

ties but as members of a network of companies (Anderson,

Hakansson, & Johanson, 1994). In fact, it is common that companies pur-

chase from many of the same suppliers and sell to the same customers,

so the organizations that win more often are those that best manage

these relationships. In order to successfully manage key relationships

across a network of companies, the authors proposed a framework com-

prised of eight cross-functional, cross-firm processes. Implementation

of the processes requires the involvement of all business functions.

Sixteen years have gone by since the 2000 SCM article in Industrial

Marketing Management and the terms supply chain and SCM have be-

come common in the corporate world and in academic research

(Varoutsa & Scapens,2015).However,there is still not a consensus

view of what SCM involves or how it should be implemented (Vallet-

Bellmunt, Martínez-Fernández,& Capó-Vicedo, 2011). Given the

number of university programs devoted to SCM (many with specialized

research centers on the topic), it is startling there are only two cross-

functional, cross-firm, process-based frameworks that can be,and

have been,implemented in major corporations (Lambert,García-

Dastugue, & Croxton,2005): The Supply Chain Operations Reference

(SCOR) model developed and endorsed by the Supply-Chain Council

(now part of The American Production and Inventory Control Society),

and the SCM framework described by Lambert and Cooper (2000).

While many areas for research still exist, the research team led by

the first author of the 2000 article has addressed many of the research

questions raised in that article. The results of 16 years of research devo

ed to further development of the framework have been reported in a

total of 30 publications including two books, one in the fourth edition.

Our purpose in this article is to summarize the progress made, describe

how managers can benefit from using the framework and identify op-

portunities for further research. In the next section, we provide a sum-

mary of the contributions to SCM made by Lambert and Cooper

(2000). This is followed by a description of the research priorities that

the executive members identified since the early days of the research

center1 and a timeline of the publications that resulted from the re-

search. Then, the methodologies used to refine and extend the original

SCM framework since 2000 are described.Next, we provide the re-

search findings including: an updated definition of SCM; an evaluation

of the premise that the new basis for competition is supply chain vs.

supply chain; an explanation of why supply chain management is

about relationship management; a description of two tools that can be

used to structure key supply chain relationships; an overview of supply

chain mapping; and, a summary of changes to the original supply chain

framework described in the 2000 article. This is followed by a section on

the SCM framework in 2016 which includes: a description of the current

state of the SCM framework; revised process descriptions and figures;

guidelines for implementing the SCM processes; findings on value co-

Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

⁎ Corresponding author.

E-mail address: lambert.119@osu.edu (D.M. Lambert).

1 The research center involves executives from non-competing firms and academics

who have been meeting regularly since 1992 with the objective of improving SCM theory

and practice.

IMM-07437; No of Pages 16

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

0019-8501/© 2016 Published by Elsevier Inc.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Industrial Marketing Management

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing M

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

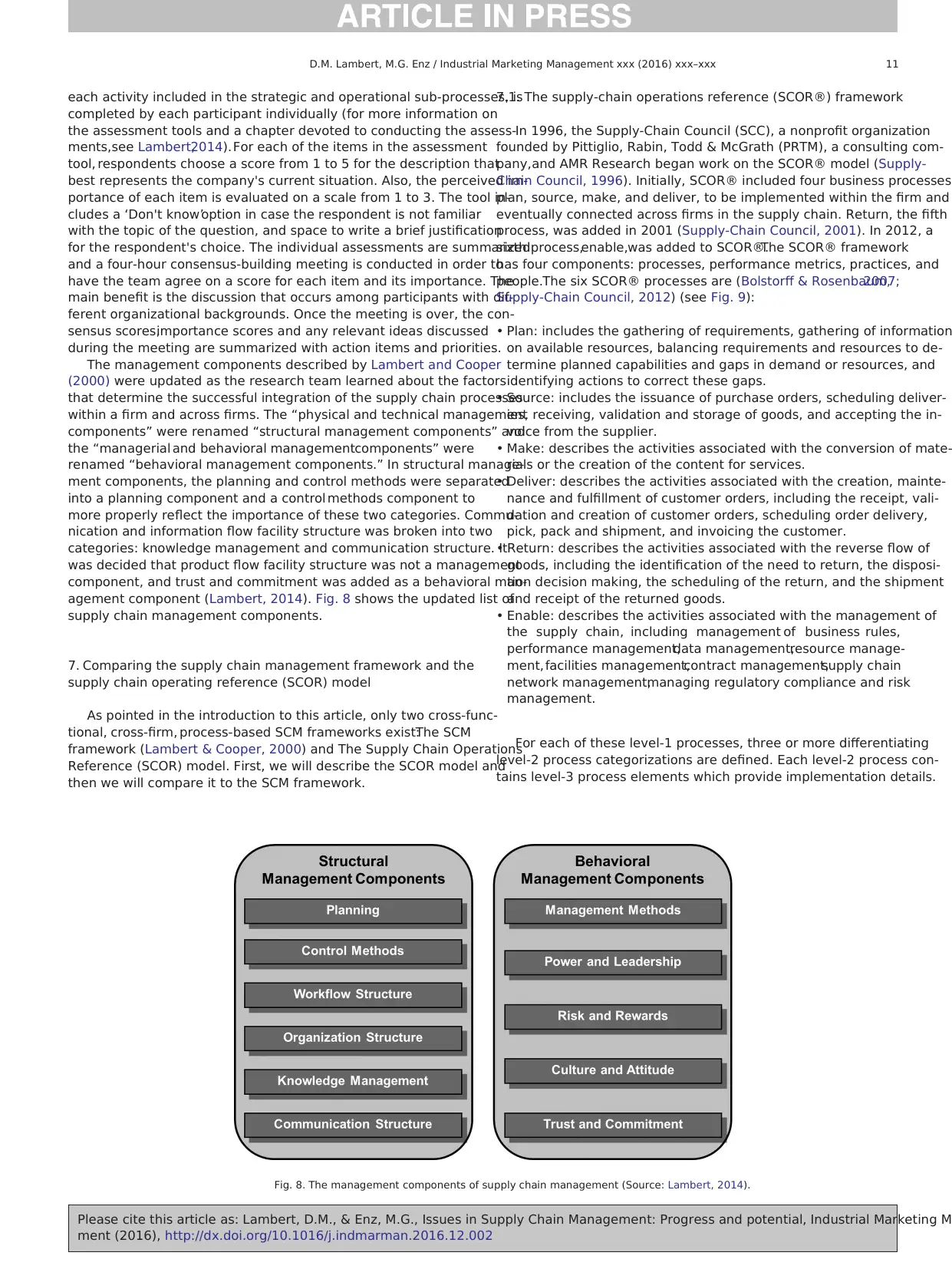

creation; an explanation of how SCM process performance affects EVA;

a description of process assessment tools; and, an updated list of man-

agement components.Then,the SCM framework is compared with

the Supply Chain Operating Reference (SCOR) model. The paper ends

with opportunities for future research and conclusions.

2. The supply chain management framework in 2000

The original article (Lambert & Cooper,2000) described the out-

comes of empirical research conducted by a team of academics and ex-

ecutives who met regularly since 1992 with the goal of developing a

normative SCM framework. The contributions of the article included:

1) a clarification in terminology regarding the differences between lo-

gistics (an organizational function) and SCM (the management of a net-

work of companies); 2) a definition of SCM that focused on the

integration of eight macro business processes across firms; 3) a require-

ment that the eight SCM processes are managed by cross-functional

teams that involve all key business functions; 4) a recognition of the im-

portance of managing business relationships within a complex network

of companies; 5) a description of methods for mapping the supply chain

network structure and for identifying the supply chain members with

whom key business processes should be linked (i.e.,customer and

supplier segmentation); 6) a description of the eight key SCM

processes that need to be implemented; 7) an explanation of nine

managementcomponents to manage each process; 8) a list of

recommendations for implementation; and, 9) a summary of directions

for future research.

The predominant definitions of SCM that existed at the time the

research center began in 1992 resembled the contemporary under-

standing of logistics management.The nature of logistics and SCM

as functional silos within companies remained unchallenged,

which created confusion for managers and academics.For many,

this confusion continues to exist (Hingley, Lindgreen, & Grant,

2015). Also, the complexity required to manage all suppliers back

to the point of origin and all intermediaries to the point of consump-

tion by a single function made the popular definitions of SCM unreal-

istic and impracticable at a minimum.The following definition of

SCM, developed with input from the members of the research center,

changed the focus from a functional orientation to one that empha-

sized the management of business processes across companies to

create a competitive advantage.

“Supply chain management is the integration of key business pro-

cesses from end user through originalsuppliers that provides

products,services and information that add value for customers

and other stakeholders” (Lambert & Cooper, 2000, p. 66).

The research conducted with the member companies combined

with concepts from the marketing channels literature led to a “concep-

tual framework of supply chain management” (Lambert & Cooper, 2000,

p. 69) that described three major interrelated steps that needed to be

designed and implemented in order to successfully manage a supply

chain. The first step consisted of identifying the key supply chain mem-

bers with whom to link processes.

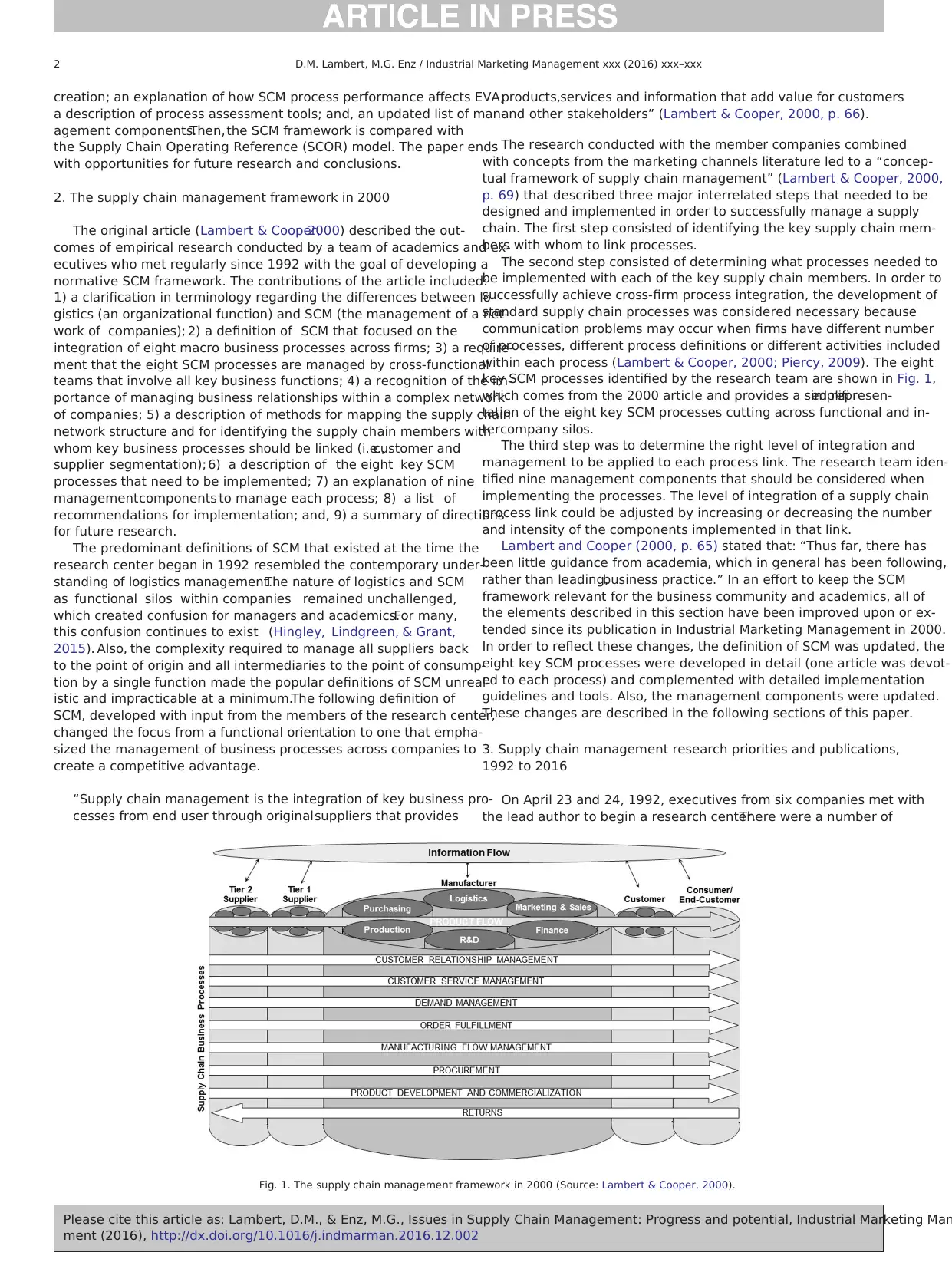

The second step consisted of determining what processes needed to

be implemented with each of the key supply chain members. In order to

successfully achieve cross-firm process integration, the development of

standard supply chain processes was considered necessary because

communication problems may occur when firms have different number

of processes, different process definitions or different activities included

within each process (Lambert & Cooper, 2000; Piercy, 2009). The eight

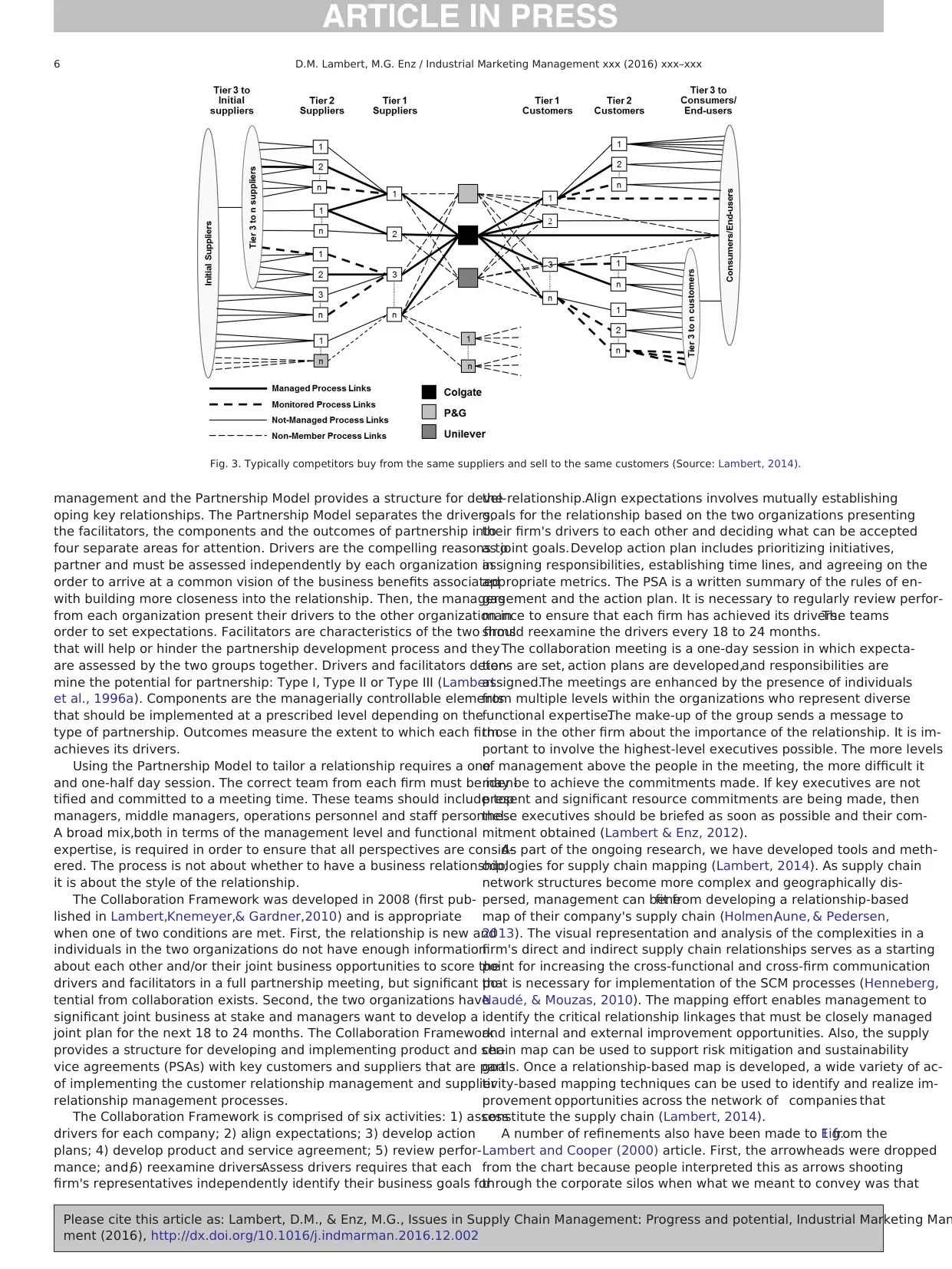

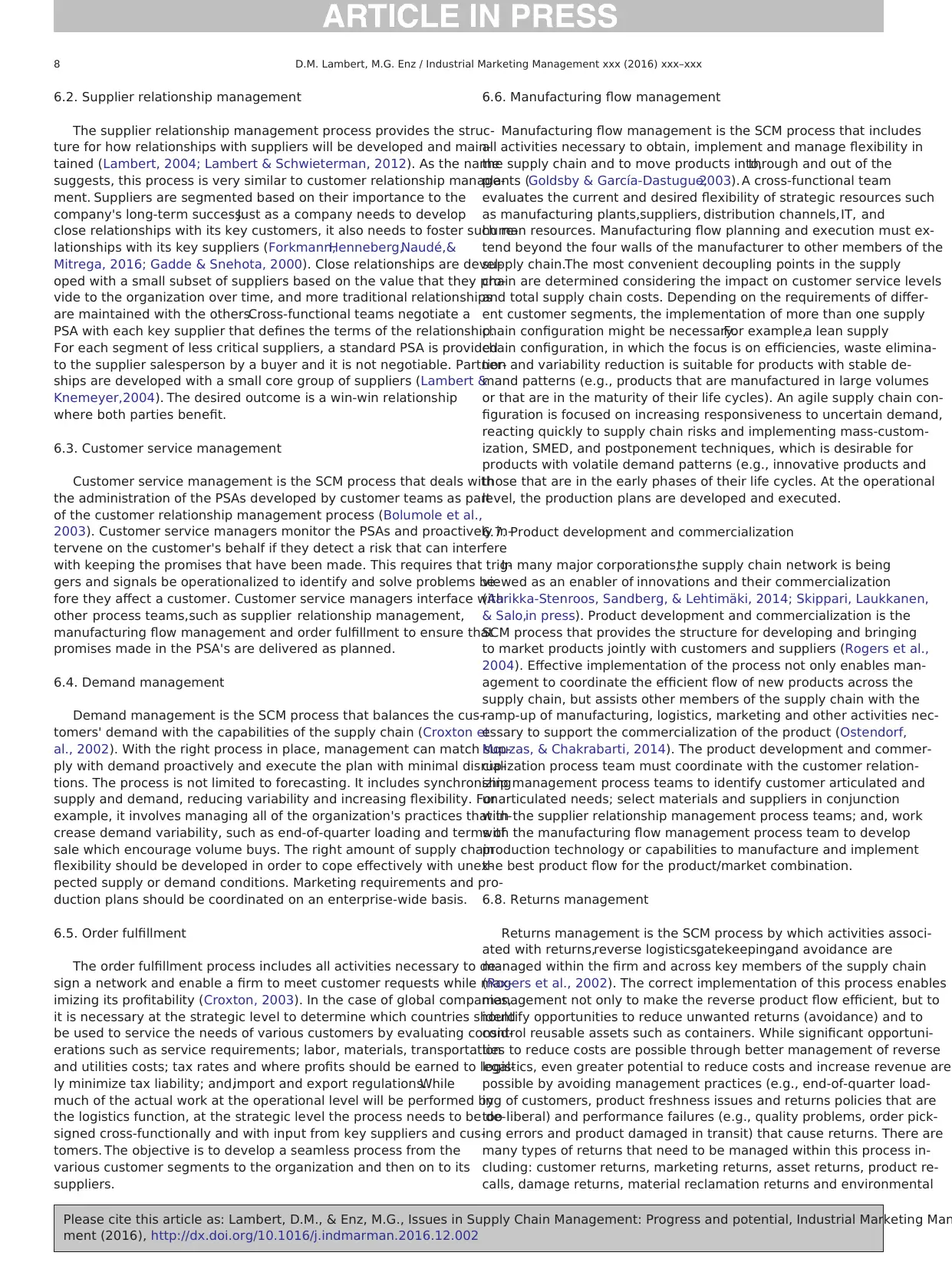

key SCM processes identified by the research team are shown in Fig. 1,

which comes from the 2000 article and provides a simplified represen-

tation of the eight key SCM processes cutting across functional and in-

tercompany silos.

The third step was to determine the right level of integration and

management to be applied to each process link. The research team iden-

tified nine management components that should be considered when

implementing the processes. The level of integration of a supply chain

process link could be adjusted by increasing or decreasing the number

and intensity of the components implemented in that link.

Lambert and Cooper (2000, p. 65) stated that: “Thus far, there has

been little guidance from academia, which in general has been following,

rather than leading,business practice.” In an effort to keep the SCM

framework relevant for the business community and academics, all of

the elements described in this section have been improved upon or ex-

tended since its publication in Industrial Marketing Management in 2000.

In order to reflect these changes, the definition of SCM was updated, the

eight key SCM processes were developed in detail (one article was devot-

ed to each process) and complemented with detailed implementation

guidelines and tools. Also, the management components were updated.

These changes are described in the following sections of this paper.

3. Supply chain management research priorities and publications,

1992 to 2016

On April 23 and 24, 1992, executives from six companies met with

the lead author to begin a research center.There were a number of

Fig. 1. The supply chain management framework in 2000 (Source: Lambert & Cooper, 2000).

2 D.M. Lambert, M.G. Enz / Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing Man

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

a description of process assessment tools; and, an updated list of man-

agement components.Then,the SCM framework is compared with

the Supply Chain Operating Reference (SCOR) model. The paper ends

with opportunities for future research and conclusions.

2. The supply chain management framework in 2000

The original article (Lambert & Cooper,2000) described the out-

comes of empirical research conducted by a team of academics and ex-

ecutives who met regularly since 1992 with the goal of developing a

normative SCM framework. The contributions of the article included:

1) a clarification in terminology regarding the differences between lo-

gistics (an organizational function) and SCM (the management of a net-

work of companies); 2) a definition of SCM that focused on the

integration of eight macro business processes across firms; 3) a require-

ment that the eight SCM processes are managed by cross-functional

teams that involve all key business functions; 4) a recognition of the im-

portance of managing business relationships within a complex network

of companies; 5) a description of methods for mapping the supply chain

network structure and for identifying the supply chain members with

whom key business processes should be linked (i.e.,customer and

supplier segmentation); 6) a description of the eight key SCM

processes that need to be implemented; 7) an explanation of nine

managementcomponents to manage each process; 8) a list of

recommendations for implementation; and, 9) a summary of directions

for future research.

The predominant definitions of SCM that existed at the time the

research center began in 1992 resembled the contemporary under-

standing of logistics management.The nature of logistics and SCM

as functional silos within companies remained unchallenged,

which created confusion for managers and academics.For many,

this confusion continues to exist (Hingley, Lindgreen, & Grant,

2015). Also, the complexity required to manage all suppliers back

to the point of origin and all intermediaries to the point of consump-

tion by a single function made the popular definitions of SCM unreal-

istic and impracticable at a minimum.The following definition of

SCM, developed with input from the members of the research center,

changed the focus from a functional orientation to one that empha-

sized the management of business processes across companies to

create a competitive advantage.

“Supply chain management is the integration of key business pro-

cesses from end user through originalsuppliers that provides

products,services and information that add value for customers

and other stakeholders” (Lambert & Cooper, 2000, p. 66).

The research conducted with the member companies combined

with concepts from the marketing channels literature led to a “concep-

tual framework of supply chain management” (Lambert & Cooper, 2000,

p. 69) that described three major interrelated steps that needed to be

designed and implemented in order to successfully manage a supply

chain. The first step consisted of identifying the key supply chain mem-

bers with whom to link processes.

The second step consisted of determining what processes needed to

be implemented with each of the key supply chain members. In order to

successfully achieve cross-firm process integration, the development of

standard supply chain processes was considered necessary because

communication problems may occur when firms have different number

of processes, different process definitions or different activities included

within each process (Lambert & Cooper, 2000; Piercy, 2009). The eight

key SCM processes identified by the research team are shown in Fig. 1,

which comes from the 2000 article and provides a simplified represen-

tation of the eight key SCM processes cutting across functional and in-

tercompany silos.

The third step was to determine the right level of integration and

management to be applied to each process link. The research team iden-

tified nine management components that should be considered when

implementing the processes. The level of integration of a supply chain

process link could be adjusted by increasing or decreasing the number

and intensity of the components implemented in that link.

Lambert and Cooper (2000, p. 65) stated that: “Thus far, there has

been little guidance from academia, which in general has been following,

rather than leading,business practice.” In an effort to keep the SCM

framework relevant for the business community and academics, all of

the elements described in this section have been improved upon or ex-

tended since its publication in Industrial Marketing Management in 2000.

In order to reflect these changes, the definition of SCM was updated, the

eight key SCM processes were developed in detail (one article was devot-

ed to each process) and complemented with detailed implementation

guidelines and tools. Also, the management components were updated.

These changes are described in the following sections of this paper.

3. Supply chain management research priorities and publications,

1992 to 2016

On April 23 and 24, 1992, executives from six companies met with

the lead author to begin a research center.There were a number of

Fig. 1. The supply chain management framework in 2000 (Source: Lambert & Cooper, 2000).

2 D.M. Lambert, M.G. Enz / Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing Man

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

things that made this research center unique at the time, but the two

most significant were that the members would be executives from

non-competing companies and the executives would determine the re-

search agenda. Each company would contribute $20,000 per year and

two people from each company could attend the meetings. The mission

was to provide the opportunity for leading practitioners and academics

to pursue the critical issues related to achieving excellence in SCM.

Membership consisted of representatives of firms recognized as indus-

try leaders. Balance was maintained both as to the nature of the firms

and the expertise of their representatives,and the membership was

targeted at 12 to 15 firms in order to preserve the intimacy provided

by the smaller size.

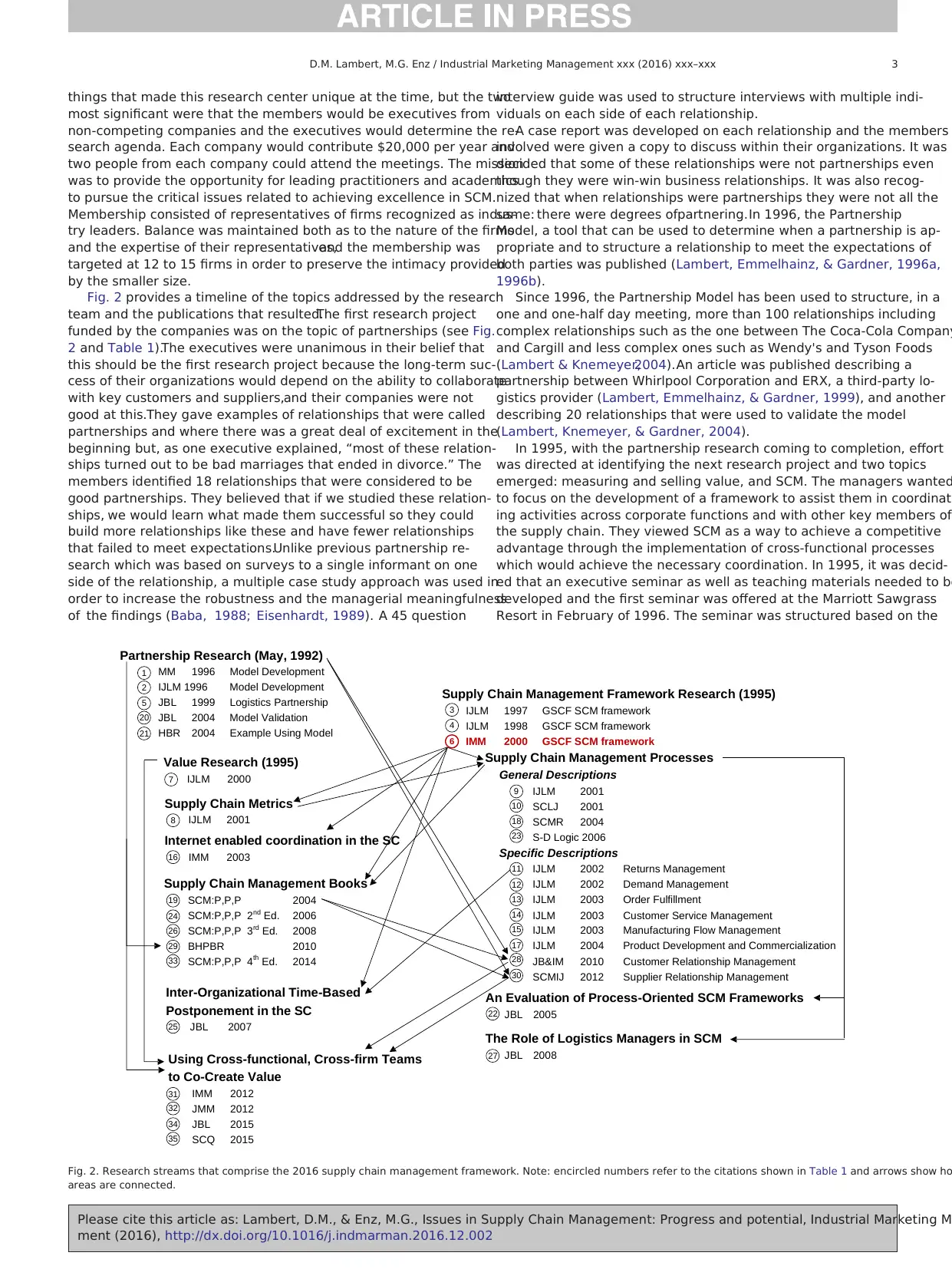

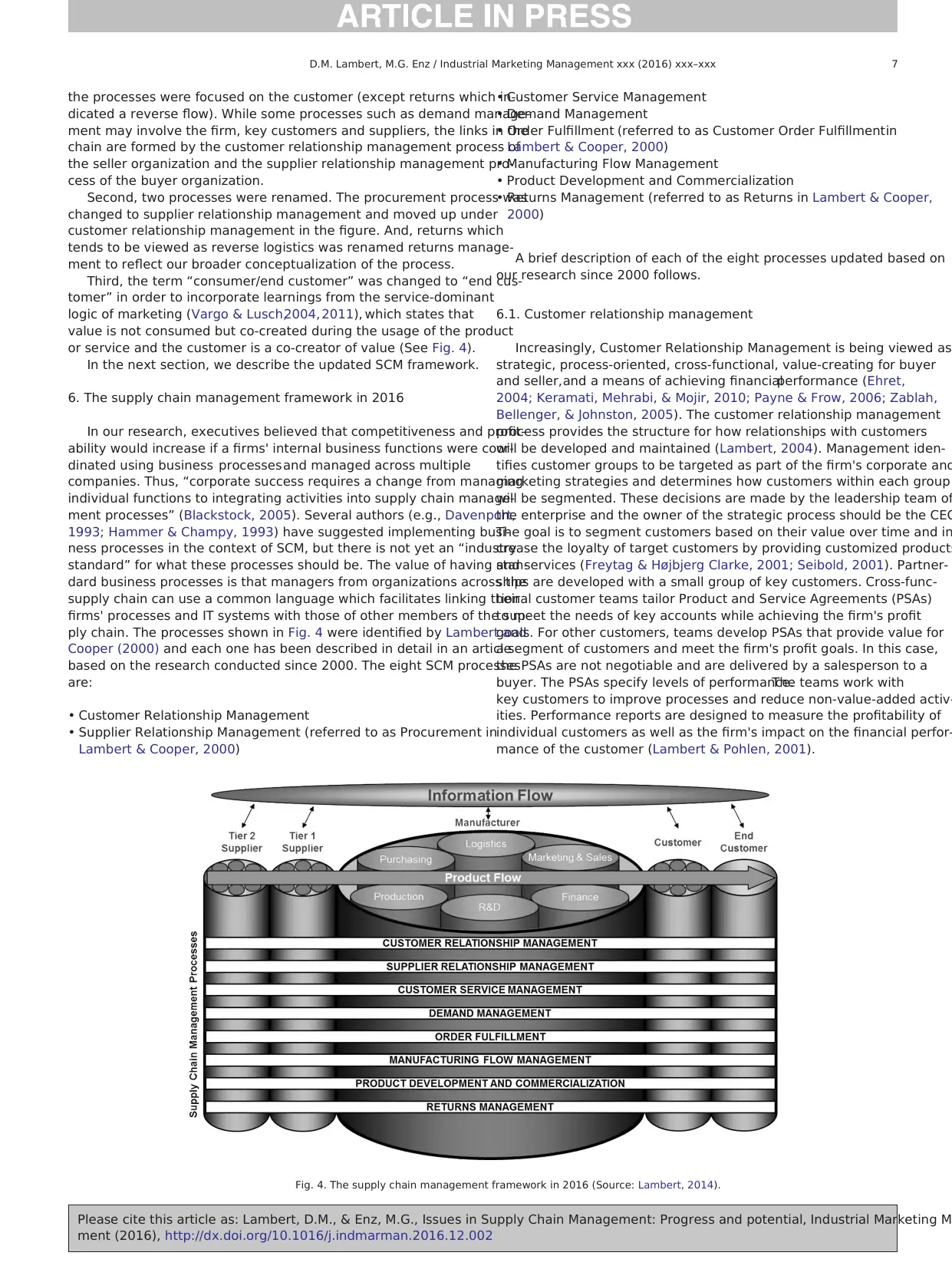

Fig. 2 provides a timeline of the topics addressed by the research

team and the publications that resulted.The first research project

funded by the companies was on the topic of partnerships (see Fig.

2 and Table 1).The executives were unanimous in their belief that

this should be the first research project because the long-term suc-

cess of their organizations would depend on the ability to collaborate

with key customers and suppliers,and their companies were not

good at this.They gave examples of relationships that were called

partnerships and where there was a great deal of excitement in the

beginning but, as one executive explained, “most of these relation-

ships turned out to be bad marriages that ended in divorce.” The

members identified 18 relationships that were considered to be

good partnerships. They believed that if we studied these relation-

ships, we would learn what made them successful so they could

build more relationships like these and have fewer relationships

that failed to meet expectations.Unlike previous partnership re-

search which was based on surveys to a single informant on one

side of the relationship, a multiple case study approach was used in

order to increase the robustness and the managerial meaningfulness

of the findings (Baba, 1988; Eisenhardt, 1989). A 45 question

interview guide was used to structure interviews with multiple indi-

viduals on each side of each relationship.

A case report was developed on each relationship and the members

involved were given a copy to discuss within their organizations. It was

decided that some of these relationships were not partnerships even

though they were win-win business relationships. It was also recog-

nized that when relationships were partnerships they were not all the

same: there were degrees ofpartnering.In 1996, the Partnership

Model, a tool that can be used to determine when a partnership is ap-

propriate and to structure a relationship to meet the expectations of

both parties was published (Lambert, Emmelhainz, & Gardner, 1996a,

1996b).

Since 1996, the Partnership Model has been used to structure, in a

one and one-half day meeting, more than 100 relationships including

complex relationships such as the one between The Coca-Cola Company

and Cargill and less complex ones such as Wendy's and Tyson Foods

(Lambert & Knemeyer,2004).An article was published describing a

partnership between Whirlpool Corporation and ERX, a third-party lo-

gistics provider (Lambert, Emmelhainz, & Gardner, 1999), and another

describing 20 relationships that were used to validate the model

(Lambert, Knemeyer, & Gardner, 2004).

In 1995, with the partnership research coming to completion, effort

was directed at identifying the next research project and two topics

emerged: measuring and selling value, and SCM. The managers wanted

to focus on the development of a framework to assist them in coordinat

ing activities across corporate functions and with other key members of

the supply chain. They viewed SCM as a way to achieve a competitive

advantage through the implementation of cross-functional processes

which would achieve the necessary coordination. In 1995, it was decid-

ed that an executive seminar as well as teaching materials needed to be

developed and the first seminar was offered at the Marriott Sawgrass

Resort in February of 1996. The seminar was structured based on the

Supply Chain Management Framework Research (1995)

IJLM 1997 GSCF SCM framework

IJLM 1998 GSCF SCM framework

IMM 2000 GSCF SCM framework

Supply Chain Management Processes

General Descriptions

IJLM 2001

SCLJ 2001

SCMR 2004

S-D Logic 2006

Specific Descriptions

IJLM 2002 Returns Management

IJLM 2002 Demand Management

IJLM 2003 Order Fulfillment

IJLM 2003 Customer Service Management

IJLM 2003 Manufacturing Flow Management

IJLM 2004 Product Development and Commercialization

JB&IM 2010 Customer Relationship Management

SCMIJ 2012 Supplier Relationship Management

Partnership Research (May, 1992)

MM 1996 Model Development

IJLM 1996 Model Development

JBL 1999 Logistics Partnership

JBL 2004 Model Validation

HBR 2004 Example Using Model

Value Research (1995)

IJLM 2000

Supply Chain Metrics

IJLM 2001

Internet enabled coordination in the SC

IMM 2003

Supply Chain Management Books

SCM:P,P,P 2004

SCM:P,P,P 2nd Ed. 2006

SCM:P,P,P 3rd Ed. 2008

BHPBR 2010

SCM:P,P,P 4th Ed. 2014

Inter-Organizational Time-Based

Postponement in the SC

JBL 2007

Using Cross-functional, Cross-firm Teams

to Co-Create Value

IMM 2012

JMM 2012

JBL 2015

SCQ 2015

An Evaluation of Process-Oriented SCM Frameworks

JBL 2005

The Role of Logistics Managers in SCM

JBL 2008

1

2

5

20

21

7

8

19

24

29

26

25

31

32

34

35

16

33

3

4

6

9

10

18

23

11

12

13

14

15

17

28

30

22

27

Fig. 2. Research streams that comprise the 2016 supply chain management framework. Note: encircled numbers refer to the citations shown in Table 1 and arrows show ho

areas are connected.

3D.M. Lambert, M.G. Enz / Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing M

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

most significant were that the members would be executives from

non-competing companies and the executives would determine the re-

search agenda. Each company would contribute $20,000 per year and

two people from each company could attend the meetings. The mission

was to provide the opportunity for leading practitioners and academics

to pursue the critical issues related to achieving excellence in SCM.

Membership consisted of representatives of firms recognized as indus-

try leaders. Balance was maintained both as to the nature of the firms

and the expertise of their representatives,and the membership was

targeted at 12 to 15 firms in order to preserve the intimacy provided

by the smaller size.

Fig. 2 provides a timeline of the topics addressed by the research

team and the publications that resulted.The first research project

funded by the companies was on the topic of partnerships (see Fig.

2 and Table 1).The executives were unanimous in their belief that

this should be the first research project because the long-term suc-

cess of their organizations would depend on the ability to collaborate

with key customers and suppliers,and their companies were not

good at this.They gave examples of relationships that were called

partnerships and where there was a great deal of excitement in the

beginning but, as one executive explained, “most of these relation-

ships turned out to be bad marriages that ended in divorce.” The

members identified 18 relationships that were considered to be

good partnerships. They believed that if we studied these relation-

ships, we would learn what made them successful so they could

build more relationships like these and have fewer relationships

that failed to meet expectations.Unlike previous partnership re-

search which was based on surveys to a single informant on one

side of the relationship, a multiple case study approach was used in

order to increase the robustness and the managerial meaningfulness

of the findings (Baba, 1988; Eisenhardt, 1989). A 45 question

interview guide was used to structure interviews with multiple indi-

viduals on each side of each relationship.

A case report was developed on each relationship and the members

involved were given a copy to discuss within their organizations. It was

decided that some of these relationships were not partnerships even

though they were win-win business relationships. It was also recog-

nized that when relationships were partnerships they were not all the

same: there were degrees ofpartnering.In 1996, the Partnership

Model, a tool that can be used to determine when a partnership is ap-

propriate and to structure a relationship to meet the expectations of

both parties was published (Lambert, Emmelhainz, & Gardner, 1996a,

1996b).

Since 1996, the Partnership Model has been used to structure, in a

one and one-half day meeting, more than 100 relationships including

complex relationships such as the one between The Coca-Cola Company

and Cargill and less complex ones such as Wendy's and Tyson Foods

(Lambert & Knemeyer,2004).An article was published describing a

partnership between Whirlpool Corporation and ERX, a third-party lo-

gistics provider (Lambert, Emmelhainz, & Gardner, 1999), and another

describing 20 relationships that were used to validate the model

(Lambert, Knemeyer, & Gardner, 2004).

In 1995, with the partnership research coming to completion, effort

was directed at identifying the next research project and two topics

emerged: measuring and selling value, and SCM. The managers wanted

to focus on the development of a framework to assist them in coordinat

ing activities across corporate functions and with other key members of

the supply chain. They viewed SCM as a way to achieve a competitive

advantage through the implementation of cross-functional processes

which would achieve the necessary coordination. In 1995, it was decid-

ed that an executive seminar as well as teaching materials needed to be

developed and the first seminar was offered at the Marriott Sawgrass

Resort in February of 1996. The seminar was structured based on the

Supply Chain Management Framework Research (1995)

IJLM 1997 GSCF SCM framework

IJLM 1998 GSCF SCM framework

IMM 2000 GSCF SCM framework

Supply Chain Management Processes

General Descriptions

IJLM 2001

SCLJ 2001

SCMR 2004

S-D Logic 2006

Specific Descriptions

IJLM 2002 Returns Management

IJLM 2002 Demand Management

IJLM 2003 Order Fulfillment

IJLM 2003 Customer Service Management

IJLM 2003 Manufacturing Flow Management

IJLM 2004 Product Development and Commercialization

JB&IM 2010 Customer Relationship Management

SCMIJ 2012 Supplier Relationship Management

Partnership Research (May, 1992)

MM 1996 Model Development

IJLM 1996 Model Development

JBL 1999 Logistics Partnership

JBL 2004 Model Validation

HBR 2004 Example Using Model

Value Research (1995)

IJLM 2000

Supply Chain Metrics

IJLM 2001

Internet enabled coordination in the SC

IMM 2003

Supply Chain Management Books

SCM:P,P,P 2004

SCM:P,P,P 2nd Ed. 2006

SCM:P,P,P 3rd Ed. 2008

BHPBR 2010

SCM:P,P,P 4th Ed. 2014

Inter-Organizational Time-Based

Postponement in the SC

JBL 2007

Using Cross-functional, Cross-firm Teams

to Co-Create Value

IMM 2012

JMM 2012

JBL 2015

SCQ 2015

An Evaluation of Process-Oriented SCM Frameworks

JBL 2005

The Role of Logistics Managers in SCM

JBL 2008

1

2

5

20

21

7

8

19

24

29

26

25

31

32

34

35

16

33

3

4

6

9

10

18

23

11

12

13

14

15

17

28

30

22

27

Fig. 2. Research streams that comprise the 2016 supply chain management framework. Note: encircled numbers refer to the citations shown in Table 1 and arrows show ho

areas are connected.

3D.M. Lambert, M.G. Enz / Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing M

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

SCM framework which at the time included seven processes. An eighth

process, returns management, was added prior to the second seminar

held in April 1997. The framework and a definition of SCM were pub-

lished in 1997 (Cooper, Lambert, & Pagh, 1997) based on the contents

of the seminars and research (See Fig. 2 and Table 1). The framework

was further developed as the research continued and follow-up articles

were published in 1998 (Lambert,Cooper,& Pagh,1998) and 2000

(Lambert & Cooper, 2000). Also, an article summarizing the research

on measuring and selling value was published (Lambert & Burduroglu,

2000).

In 2000, an MBA course on SCM based on the framework was of-

fered for the first time at The Ohio State University. In 2001, an article

was published on supply chain metrics research (Lambert & Pohlen,

2001) in which process performance was tied to EVA® (Economic

Value Added) and it was concluded that there were no end-to-end fi-

nancial measures possible for the entire supply chain. Rather,SCM

was really about relationship management, and the customer rela-

tionship management process of the seller organization and the sup-

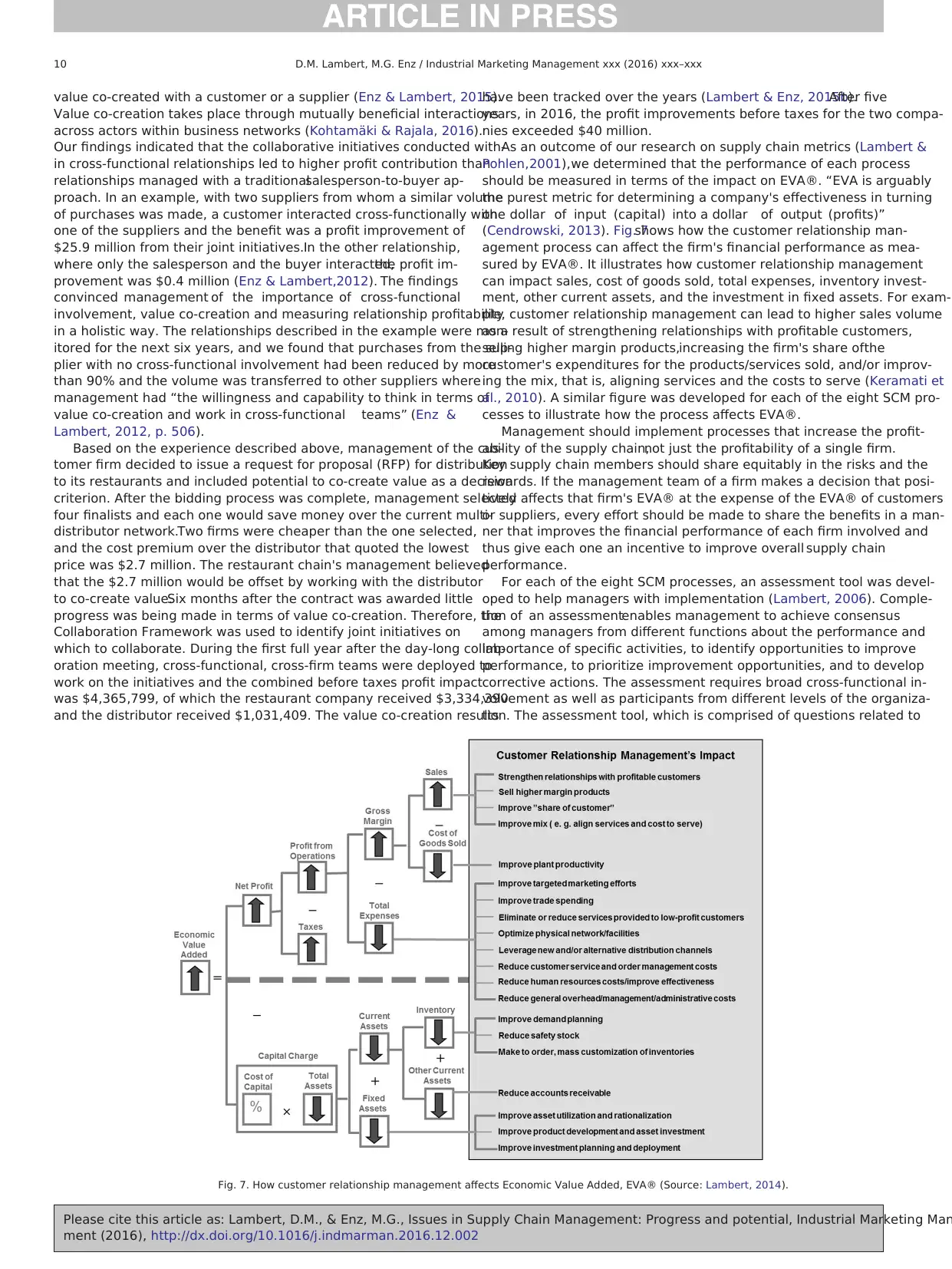

plier relationship management process of the customer organization

formed the links in the chain.Performance at each link would be

measured as the impact of the relationship on each organization's in-

cremental profitability.Also in 2001,an article was published that

described the strategic and operational sub-processes for each of

the eight SCM processes (Croxton, García-Dastugue,Lambert, &

Rogers, 2001).

Publications based on our continuing research provided details on

each process:the returns managementprocess (Rogers,Lambert,

Croxton, & García-Dastugue, 2002), the demand management process

(Croxton, Lambert, García-Dastugue, & Rogers, 2002), the order fulfill-

ment process (Croxton, 2003), the customer service management pro-

cess (Bolumole, Knemeyer, & Lambert, 2003), the manufacturing flow

management process (Goldsby & García-Dastugue, 2003), the product

developmentand commercialization process (Rogers,Lambert,&

Knemeyer,2004), the customer relationship management process,

(Lambert, 2004, 2010), and the supplier relationship management pro-

cess (Lambert, 2004; Lambert & Schwieterman, 2012). In 2004, the first

edition of Supply Chain Management: Processes,Partnerships,Perfor-

mance (Lambert, 2004) was published.

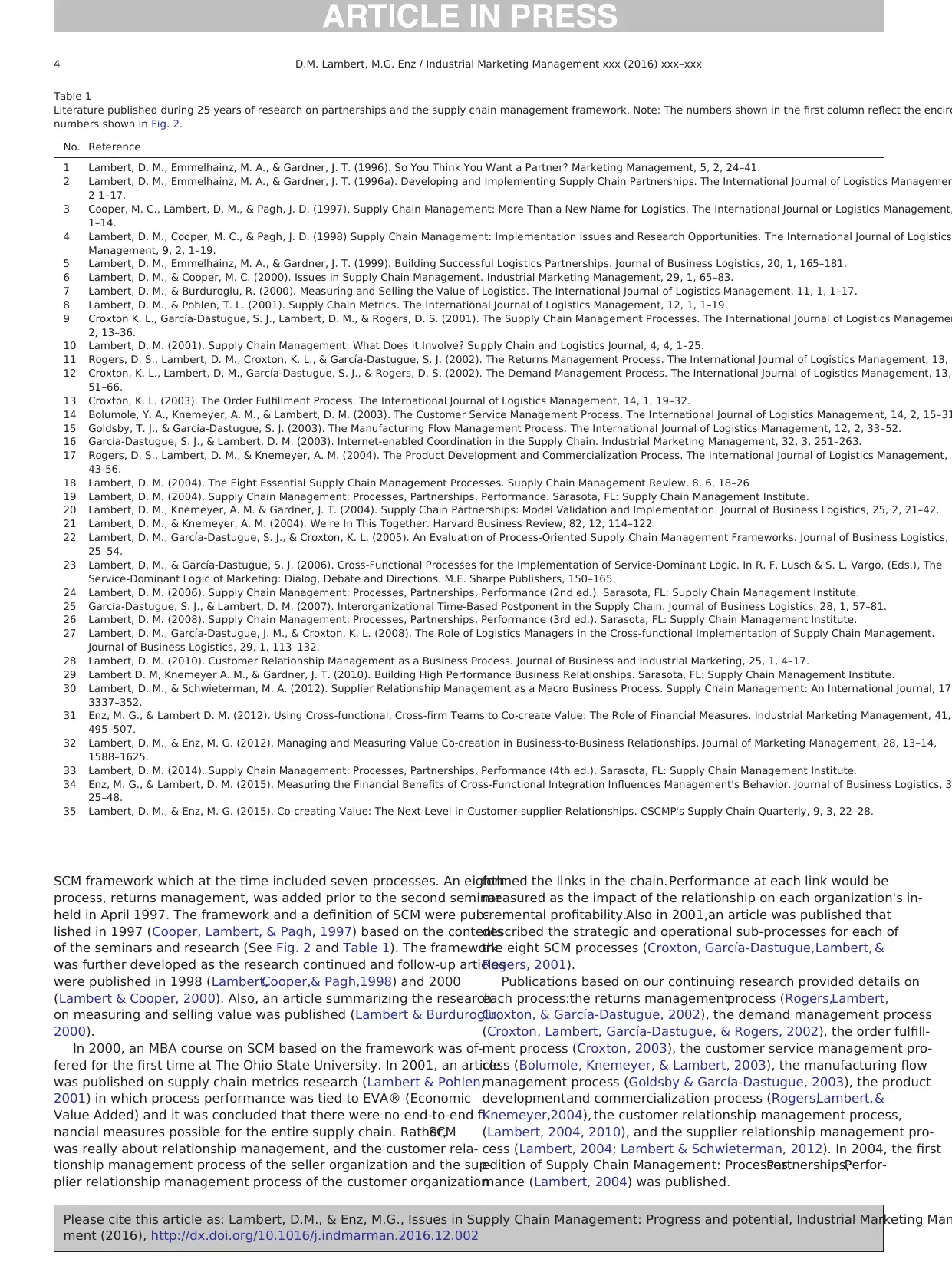

Table 1

Literature published during 25 years of research on partnerships and the supply chain management framework. Note: The numbers shown in the first column reflect the encirc

numbers shown in Fig. 2.

No. Reference

1 Lambert, D. M., Emmelhainz, M. A., & Gardner, J. T. (1996). So You Think You Want a Partner? Marketing Management, 5, 2, 24–41.

2 Lambert, D. M., Emmelhainz, M. A., & Gardner, J. T. (1996a). Developing and Implementing Supply Chain Partnerships. The International Journal of Logistics Managemen

2 1–17.

3 Cooper, M. C., Lambert, D. M., & Pagh, J. D. (1997). Supply Chain Management: More Than a New Name for Logistics. The International Journal or Logistics Management,

1–14.

4 Lambert, D. M., Cooper, M. C., & Pagh, J. D. (1998) Supply Chain Management: Implementation Issues and Research Opportunities. The International Journal of Logistics

Management, 9, 2, 1–19.

5 Lambert, D. M., Emmelhainz, M. A., & Gardner, J. T. (1999). Building Successful Logistics Partnerships. Journal of Business Logistics, 20, 1, 165–181.

6 Lambert, D. M., & Cooper, M. C. (2000). Issues in Supply Chain Management. Industrial Marketing Management, 29, 1, 65–83.

7 Lambert, D. M., & Burduroglu, R. (2000). Measuring and Selling the Value of Logistics. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 11, 1, 1–17.

8 Lambert, D. M., & Pohlen, T. L. (2001). Supply Chain Metrics. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 12, 1, 1–19.

9 Croxton K. L., García-Dastugue, S. J., Lambert, D. M., & Rogers, D. S. (2001). The Supply Chain Management Processes. The International Journal of Logistics Managemen

2, 13–36.

10 Lambert, D. M. (2001). Supply Chain Management: What Does it Involve? Supply Chain and Logistics Journal, 4, 4, 1–25.

11 Rogers, D. S., Lambert, D. M., Croxton, K. L., & García-Dastugue, S. J. (2002). The Returns Management Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 13,

12 Croxton, K. L., Lambert, D. M., García-Dastugue, S. J., & Rogers, D. S. (2002). The Demand Management Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 13,

51–66.

13 Croxton, K. L. (2003). The Order Fulfillment Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 14, 1, 19–32.

14 Bolumole, Y. A., Knemeyer, A. M., & Lambert, D. M. (2003). The Customer Service Management Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 14, 2, 15–31

15 Goldsby, T. J., & García-Dastugue, S. J. (2003). The Manufacturing Flow Management Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 12, 2, 33–52.

16 García-Dastugue, S. J., & Lambert, D. M. (2003). Internet-enabled Coordination in the Supply Chain. Industrial Marketing Management, 32, 3, 251–263.

17 Rogers, D. S., Lambert, D. M., & Knemeyer, A. M. (2004). The Product Development and Commercialization Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 1

43–56.

18 Lambert, D. M. (2004). The Eight Essential Supply Chain Management Processes. Supply Chain Management Review, 8, 6, 18–26

19 Lambert, D. M. (2004). Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance. Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

20 Lambert, D. M., Knemeyer, A. M. & Gardner, J. T. (2004). Supply Chain Partnerships: Model Validation and Implementation. Journal of Business Logistics, 25, 2, 21–42.

21 Lambert, D. M., & Knemeyer, A. M. (2004). We're In This Together. Harvard Business Review, 82, 12, 114–122.

22 Lambert, D. M., García-Dastugue, S. J., & Croxton, K. L. (2005). An Evaluation of Process-Oriented Supply Chain Management Frameworks. Journal of Business Logistics,

25–54.

23 Lambert, D. M., & García-Dastugue, S. J. (2006). Cross-Functional Processes for the Implementation of Service-Dominant Logic. In R. F. Lusch & S. L. Vargo, (Eds.), The

Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Directions. M.E. Sharpe Publishers, 150–165.

24 Lambert, D. M. (2006). Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance (2nd ed.). Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

25 García-Dastugue, S. J., & Lambert, D. M. (2007). Interorganizational Time-Based Postponent in the Supply Chain. Journal of Business Logistics, 28, 1, 57–81.

26 Lambert, D. M. (2008). Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance (3rd ed.). Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

27 Lambert, D. M., García-Dastugue, J. M., & Croxton, K. L. (2008). The Role of Logistics Managers in the Cross-functional Implementation of Supply Chain Management.

Journal of Business Logistics, 29, 1, 113–132.

28 Lambert, D. M. (2010). Customer Relationship Management as a Business Process. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 25, 1, 4–17.

29 Lambert D. M, Knemeyer A. M., & Gardner, J. T. (2010). Building High Performance Business Relationships. Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

30 Lambert, D. M., & Schwieterman, M. A. (2012). Supplier Relationship Management as a Macro Business Process. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17

3337–352.

31 Enz, M. G., & Lambert D. M. (2012). Using Cross-functional, Cross-firm Teams to Co-create Value: The Role of Financial Measures. Industrial Marketing Management, 41,

495–507.

32 Lambert, D. M., & Enz, M. G. (2012). Managing and Measuring Value Co-creation in Business-to-Business Relationships. Journal of Marketing Management, 28, 13–14,

1588–1625.

33 Lambert, D. M. (2014). Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance (4th ed.). Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

34 Enz, M. G., & Lambert, D. M. (2015). Measuring the Financial Benefits of Cross-Functional Integration Influences Management's Behavior. Journal of Business Logistics, 3

25–48.

35 Lambert, D. M., & Enz, M. G. (2015). Co-creating Value: The Next Level in Customer-supplier Relationships. CSCMP's Supply Chain Quarterly, 9, 3, 22–28.

4 D.M. Lambert, M.G. Enz / Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing Man

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

process, returns management, was added prior to the second seminar

held in April 1997. The framework and a definition of SCM were pub-

lished in 1997 (Cooper, Lambert, & Pagh, 1997) based on the contents

of the seminars and research (See Fig. 2 and Table 1). The framework

was further developed as the research continued and follow-up articles

were published in 1998 (Lambert,Cooper,& Pagh,1998) and 2000

(Lambert & Cooper, 2000). Also, an article summarizing the research

on measuring and selling value was published (Lambert & Burduroglu,

2000).

In 2000, an MBA course on SCM based on the framework was of-

fered for the first time at The Ohio State University. In 2001, an article

was published on supply chain metrics research (Lambert & Pohlen,

2001) in which process performance was tied to EVA® (Economic

Value Added) and it was concluded that there were no end-to-end fi-

nancial measures possible for the entire supply chain. Rather,SCM

was really about relationship management, and the customer rela-

tionship management process of the seller organization and the sup-

plier relationship management process of the customer organization

formed the links in the chain.Performance at each link would be

measured as the impact of the relationship on each organization's in-

cremental profitability.Also in 2001,an article was published that

described the strategic and operational sub-processes for each of

the eight SCM processes (Croxton, García-Dastugue,Lambert, &

Rogers, 2001).

Publications based on our continuing research provided details on

each process:the returns managementprocess (Rogers,Lambert,

Croxton, & García-Dastugue, 2002), the demand management process

(Croxton, Lambert, García-Dastugue, & Rogers, 2002), the order fulfill-

ment process (Croxton, 2003), the customer service management pro-

cess (Bolumole, Knemeyer, & Lambert, 2003), the manufacturing flow

management process (Goldsby & García-Dastugue, 2003), the product

developmentand commercialization process (Rogers,Lambert,&

Knemeyer,2004), the customer relationship management process,

(Lambert, 2004, 2010), and the supplier relationship management pro-

cess (Lambert, 2004; Lambert & Schwieterman, 2012). In 2004, the first

edition of Supply Chain Management: Processes,Partnerships,Perfor-

mance (Lambert, 2004) was published.

Table 1

Literature published during 25 years of research on partnerships and the supply chain management framework. Note: The numbers shown in the first column reflect the encirc

numbers shown in Fig. 2.

No. Reference

1 Lambert, D. M., Emmelhainz, M. A., & Gardner, J. T. (1996). So You Think You Want a Partner? Marketing Management, 5, 2, 24–41.

2 Lambert, D. M., Emmelhainz, M. A., & Gardner, J. T. (1996a). Developing and Implementing Supply Chain Partnerships. The International Journal of Logistics Managemen

2 1–17.

3 Cooper, M. C., Lambert, D. M., & Pagh, J. D. (1997). Supply Chain Management: More Than a New Name for Logistics. The International Journal or Logistics Management,

1–14.

4 Lambert, D. M., Cooper, M. C., & Pagh, J. D. (1998) Supply Chain Management: Implementation Issues and Research Opportunities. The International Journal of Logistics

Management, 9, 2, 1–19.

5 Lambert, D. M., Emmelhainz, M. A., & Gardner, J. T. (1999). Building Successful Logistics Partnerships. Journal of Business Logistics, 20, 1, 165–181.

6 Lambert, D. M., & Cooper, M. C. (2000). Issues in Supply Chain Management. Industrial Marketing Management, 29, 1, 65–83.

7 Lambert, D. M., & Burduroglu, R. (2000). Measuring and Selling the Value of Logistics. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 11, 1, 1–17.

8 Lambert, D. M., & Pohlen, T. L. (2001). Supply Chain Metrics. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 12, 1, 1–19.

9 Croxton K. L., García-Dastugue, S. J., Lambert, D. M., & Rogers, D. S. (2001). The Supply Chain Management Processes. The International Journal of Logistics Managemen

2, 13–36.

10 Lambert, D. M. (2001). Supply Chain Management: What Does it Involve? Supply Chain and Logistics Journal, 4, 4, 1–25.

11 Rogers, D. S., Lambert, D. M., Croxton, K. L., & García-Dastugue, S. J. (2002). The Returns Management Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 13,

12 Croxton, K. L., Lambert, D. M., García-Dastugue, S. J., & Rogers, D. S. (2002). The Demand Management Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 13,

51–66.

13 Croxton, K. L. (2003). The Order Fulfillment Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 14, 1, 19–32.

14 Bolumole, Y. A., Knemeyer, A. M., & Lambert, D. M. (2003). The Customer Service Management Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 14, 2, 15–31

15 Goldsby, T. J., & García-Dastugue, S. J. (2003). The Manufacturing Flow Management Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 12, 2, 33–52.

16 García-Dastugue, S. J., & Lambert, D. M. (2003). Internet-enabled Coordination in the Supply Chain. Industrial Marketing Management, 32, 3, 251–263.

17 Rogers, D. S., Lambert, D. M., & Knemeyer, A. M. (2004). The Product Development and Commercialization Process. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 1

43–56.

18 Lambert, D. M. (2004). The Eight Essential Supply Chain Management Processes. Supply Chain Management Review, 8, 6, 18–26

19 Lambert, D. M. (2004). Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance. Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

20 Lambert, D. M., Knemeyer, A. M. & Gardner, J. T. (2004). Supply Chain Partnerships: Model Validation and Implementation. Journal of Business Logistics, 25, 2, 21–42.

21 Lambert, D. M., & Knemeyer, A. M. (2004). We're In This Together. Harvard Business Review, 82, 12, 114–122.

22 Lambert, D. M., García-Dastugue, S. J., & Croxton, K. L. (2005). An Evaluation of Process-Oriented Supply Chain Management Frameworks. Journal of Business Logistics,

25–54.

23 Lambert, D. M., & García-Dastugue, S. J. (2006). Cross-Functional Processes for the Implementation of Service-Dominant Logic. In R. F. Lusch & S. L. Vargo, (Eds.), The

Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate and Directions. M.E. Sharpe Publishers, 150–165.

24 Lambert, D. M. (2006). Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance (2nd ed.). Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

25 García-Dastugue, S. J., & Lambert, D. M. (2007). Interorganizational Time-Based Postponent in the Supply Chain. Journal of Business Logistics, 28, 1, 57–81.

26 Lambert, D. M. (2008). Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance (3rd ed.). Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

27 Lambert, D. M., García-Dastugue, J. M., & Croxton, K. L. (2008). The Role of Logistics Managers in the Cross-functional Implementation of Supply Chain Management.

Journal of Business Logistics, 29, 1, 113–132.

28 Lambert, D. M. (2010). Customer Relationship Management as a Business Process. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 25, 1, 4–17.

29 Lambert D. M, Knemeyer A. M., & Gardner, J. T. (2010). Building High Performance Business Relationships. Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

30 Lambert, D. M., & Schwieterman, M. A. (2012). Supplier Relationship Management as a Macro Business Process. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17

3337–352.

31 Enz, M. G., & Lambert D. M. (2012). Using Cross-functional, Cross-firm Teams to Co-create Value: The Role of Financial Measures. Industrial Marketing Management, 41,

495–507.

32 Lambert, D. M., & Enz, M. G. (2012). Managing and Measuring Value Co-creation in Business-to-Business Relationships. Journal of Marketing Management, 28, 13–14,

1588–1625.

33 Lambert, D. M. (2014). Supply Chain Management: Processes, Partnerships, Performance (4th ed.). Sarasota, FL: Supply Chain Management Institute.

34 Enz, M. G., & Lambert, D. M. (2015). Measuring the Financial Benefits of Cross-Functional Integration Influences Management's Behavior. Journal of Business Logistics, 3

25–48.

35 Lambert, D. M., & Enz, M. G. (2015). Co-creating Value: The Next Level in Customer-supplier Relationships. CSCMP's Supply Chain Quarterly, 9, 3, 22–28.

4 D.M. Lambert, M.G. Enz / Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing Man

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4. Research methodology

In this section, we describe the research methodology used to ex-

tend and refine the SCM framework since 2000. The research included:

focus groups with executives; breakout sessions and discussions during

research center meetings; site visits to document best management

practices; analysis of the data collected; preparation of manuscripts;

and, executive feedback on the manuscripts. The triangulation of the re-

sults obtained using different research approaches increased the robust-

ness of the findings (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2009). Next, we describe the

methodologies used to: 1) identify the sub-processes of the eight SCM

processes and develop the assessment tools, and 2) conduct the value

co-creation research.

In order to identify the sub-processes of the eight SCM processes and

the specific activities that comprised each sub-process, executives were

engaged in focus group sessions (Calder, 1977; Krueger & Casey, 2000;

Morgan, 1997). The executives were from several industries including

agriculture, consumer packaged goods, energy, fashion, food products,

high-technology, industrial goods, paper products, and sporting goods.

The companies occupied multiple positions in the supply chain includ-

ing retailers, distributors, manufacturers and suppliers. Participants rep-

resented various functions and their titles included manager, director,

vice president, senior vice president, group vice president, and chief op-

erations officer.

Executives were involved in a total of eight two-day research center

meetings over a period of 28 months from July 2001 to October 2003. In

the first three meetings, the executives provided the research team with

input on the sub-processes that should comprise each of the eight busi-

ness processes. Then, in the next five meetings, sessions were held for

each specific process. For example, sessions were specifically devoted

to identifying the detailed activities and implementation issues for the

customer relationship management process (Lambert,2010).In the

July 2002 meeting, 22 executives participated. The task was to deter-

mine the specific activities that comprised each of the strategic and op-

erational sub-processes. During the October 2002 meeting, in which 18

executives participated, slides were presented that summarized the re-

sults of the previous session and the learnings from company visits. Fol-

lowing the presentation, the executives participated in an open

discussion providing suggestions for clarification. Based on the execu-

tives' feedback and additional company visits to document practice, a

manuscript was produced for the following meeting. In the third, fourth

and fifth meetings, 16, 17, and 21 executives respectively participated in

open discussion and after each session, the manuscript was revised. Ad-

ditional revisions were made to the material as experience was gained

working with member companies on implementation of the customer

relationship management process. A similar methodology was used to

develop the assessment tools (Lambert,2006) that can be used by

managers to identify opportunities for process improvement (the

assessment tools are described in ‘The supply chain management

framework in 2016’ section of this manuscript).

The value co-creation research was conducted using case study

(Eisenhardt,1989; Yin, 2009) and action research methodologies

(Näslund, Kale, & Paulraj, 2010; Stringer, 2007). Theoretical sampling

was used to select two pairs of relationships (one pair was between a

customer firm and two of its key suppliers and the other pair was be-

tween a supplier firm and two of its key customers). The relationships

within each pair were comparable in terms of business volume and im-

portance, and the main factor that differentiated them was that one of

the relationships within each pair was managed using cross-functional

teams while the other was based on traditional salesperson and buyer

interactions. The first step consisted of interviewing managers from dif-

ferent functional backgrounds within the six firms in order to identify

and compare their perceptions about the relationship in which they

were involved. The second step consisted of identifying the collabora-

tive initiatives conducted within each relationship during the previous

two years and calculating the contribution to the focal firm's

profitability. We found that relationships managed using cross-func-

tional teams led to appreciably more financial value than those man-

aged using a single contact within each organization (Enz & Lambert,

2012). In a third step, we interviewed a subset of managers in the orig-

inal sample in order to explore how perceptions about the relationships

had changed after we showed managers the financial results associated

with each relationship. The evolution of the one pair of relationships

was monitored for the next six years (Lambert & Enz, 2015a).

For the next project, an action research approach was used to ex-

plore how the Collaboration Framework can be used to develop Product

Service Agreements (PSAs) and create joint action plans for value co-

creation (Lambert & Enz, 2012). The researchers helped managers de-

velop a management structure and measurement methods to support

the implementation of the action plans. The financial outcomes of the

value co-creation initiatives were measured over time.

5. Research findings

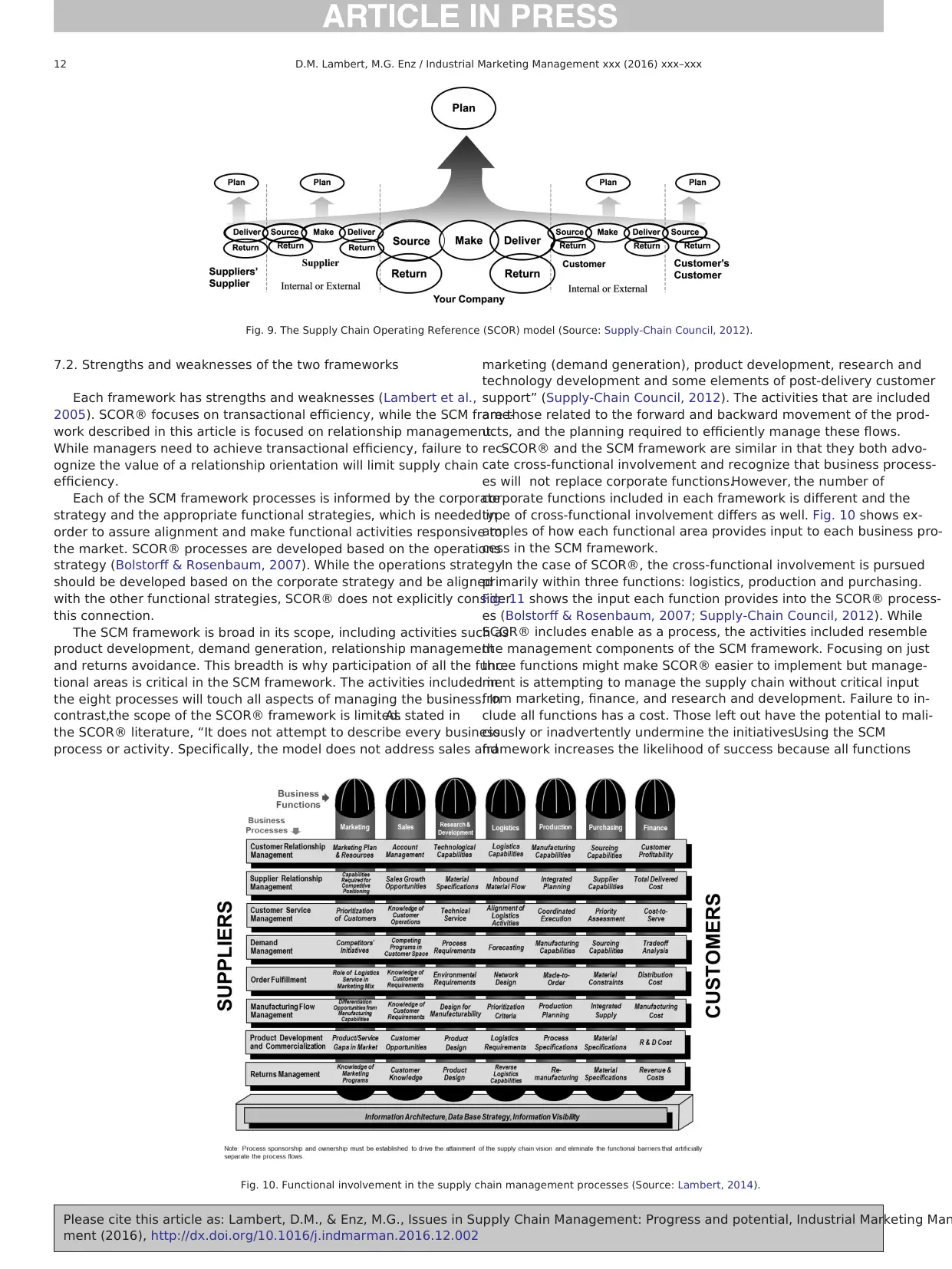

As a result of the research conducted since 2000, a number of chang

es have been made to the SCM framework and to our thinking about

SCM. The definition of SCM developed in 1995 and reported in

Lambert and Cooper (2000) was updated because it did not mention:

relationships,network of organizations or that the processes were

cross-functional. In 2013, we worked with the executive members of

the research center to craft the following new definition:

“Supply chain management is the management of relationships in

the network of organizations, from end customers through original

suppliers, using key cross-functional business processes to create

value for customers and other stakeholders” (Lambert, 2014, p. 2).

It had become common to say that competition is no longer between

companies,but it is “supply chain versus supply chain” (Lambert &

Cooper, 2000, p. 65). We have changed our minds about this. While sup

ply chain versus supply chain has some appeal given that companies

exist in supply chains, it is not technically correct. For the competition

to be supply chain versus supply chain, there would have to be a team

“A” playing a team “B”. When does this happen? The Coca-Cola Compa-

ny and PepsiCo Inc. both purchase sweeteners from Cargill and packag-

ing from the Graham Packaging Company,and in many cases,their

products are sold to the same retail customers. This overlapping of sup-

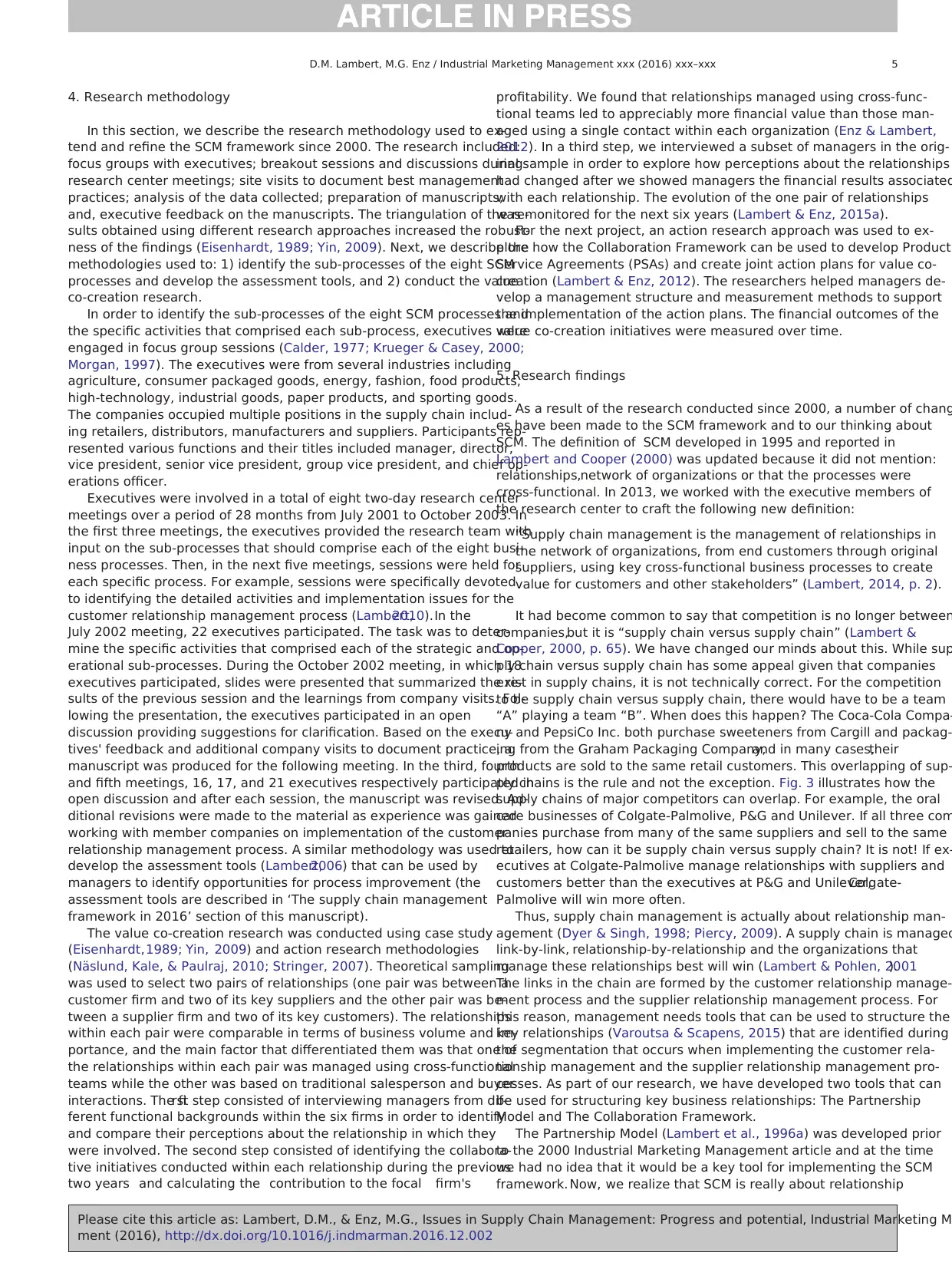

ply chains is the rule and not the exception. Fig. 3 illustrates how the

supply chains of major competitors can overlap. For example, the oral

care businesses of Colgate-Palmolive, P&G and Unilever. If all three com

panies purchase from many of the same suppliers and sell to the same

retailers, how can it be supply chain versus supply chain? It is not! If ex-

ecutives at Colgate-Palmolive manage relationships with suppliers and

customers better than the executives at P&G and Unilever,Colgate-

Palmolive will win more often.

Thus, supply chain management is actually about relationship man-

agement (Dyer & Singh, 1998; Piercy, 2009). A supply chain is managed

link-by-link, relationship-by-relationship and the organizations that

manage these relationships best will win (Lambert & Pohlen, 2001).

The links in the chain are formed by the customer relationship manage-

ment process and the supplier relationship management process. For

this reason, management needs tools that can be used to structure the

key relationships (Varoutsa & Scapens, 2015) that are identified during

the segmentation that occurs when implementing the customer rela-

tionship management and the supplier relationship management pro-

cesses. As part of our research, we have developed two tools that can

be used for structuring key business relationships: The Partnership

Model and The Collaboration Framework.

The Partnership Model (Lambert et al., 1996a) was developed prior

to the 2000 Industrial Marketing Management article and at the time

we had no idea that it would be a key tool for implementing the SCM

framework. Now, we realize that SCM is really about relationship

5D.M. Lambert, M.G. Enz / Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing M

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

In this section, we describe the research methodology used to ex-

tend and refine the SCM framework since 2000. The research included:

focus groups with executives; breakout sessions and discussions during

research center meetings; site visits to document best management

practices; analysis of the data collected; preparation of manuscripts;

and, executive feedback on the manuscripts. The triangulation of the re-

sults obtained using different research approaches increased the robust-

ness of the findings (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2009). Next, we describe the

methodologies used to: 1) identify the sub-processes of the eight SCM

processes and develop the assessment tools, and 2) conduct the value

co-creation research.

In order to identify the sub-processes of the eight SCM processes and

the specific activities that comprised each sub-process, executives were

engaged in focus group sessions (Calder, 1977; Krueger & Casey, 2000;

Morgan, 1997). The executives were from several industries including

agriculture, consumer packaged goods, energy, fashion, food products,

high-technology, industrial goods, paper products, and sporting goods.

The companies occupied multiple positions in the supply chain includ-

ing retailers, distributors, manufacturers and suppliers. Participants rep-

resented various functions and their titles included manager, director,

vice president, senior vice president, group vice president, and chief op-

erations officer.

Executives were involved in a total of eight two-day research center

meetings over a period of 28 months from July 2001 to October 2003. In

the first three meetings, the executives provided the research team with

input on the sub-processes that should comprise each of the eight busi-

ness processes. Then, in the next five meetings, sessions were held for

each specific process. For example, sessions were specifically devoted

to identifying the detailed activities and implementation issues for the

customer relationship management process (Lambert,2010).In the

July 2002 meeting, 22 executives participated. The task was to deter-

mine the specific activities that comprised each of the strategic and op-

erational sub-processes. During the October 2002 meeting, in which 18

executives participated, slides were presented that summarized the re-

sults of the previous session and the learnings from company visits. Fol-

lowing the presentation, the executives participated in an open

discussion providing suggestions for clarification. Based on the execu-

tives' feedback and additional company visits to document practice, a

manuscript was produced for the following meeting. In the third, fourth

and fifth meetings, 16, 17, and 21 executives respectively participated in

open discussion and after each session, the manuscript was revised. Ad-

ditional revisions were made to the material as experience was gained

working with member companies on implementation of the customer

relationship management process. A similar methodology was used to

develop the assessment tools (Lambert,2006) that can be used by

managers to identify opportunities for process improvement (the

assessment tools are described in ‘The supply chain management

framework in 2016’ section of this manuscript).

The value co-creation research was conducted using case study

(Eisenhardt,1989; Yin, 2009) and action research methodologies

(Näslund, Kale, & Paulraj, 2010; Stringer, 2007). Theoretical sampling

was used to select two pairs of relationships (one pair was between a

customer firm and two of its key suppliers and the other pair was be-

tween a supplier firm and two of its key customers). The relationships

within each pair were comparable in terms of business volume and im-

portance, and the main factor that differentiated them was that one of

the relationships within each pair was managed using cross-functional

teams while the other was based on traditional salesperson and buyer

interactions. The first step consisted of interviewing managers from dif-

ferent functional backgrounds within the six firms in order to identify

and compare their perceptions about the relationship in which they

were involved. The second step consisted of identifying the collabora-

tive initiatives conducted within each relationship during the previous

two years and calculating the contribution to the focal firm's

profitability. We found that relationships managed using cross-func-

tional teams led to appreciably more financial value than those man-

aged using a single contact within each organization (Enz & Lambert,

2012). In a third step, we interviewed a subset of managers in the orig-

inal sample in order to explore how perceptions about the relationships

had changed after we showed managers the financial results associated

with each relationship. The evolution of the one pair of relationships

was monitored for the next six years (Lambert & Enz, 2015a).

For the next project, an action research approach was used to ex-

plore how the Collaboration Framework can be used to develop Product

Service Agreements (PSAs) and create joint action plans for value co-

creation (Lambert & Enz, 2012). The researchers helped managers de-

velop a management structure and measurement methods to support

the implementation of the action plans. The financial outcomes of the

value co-creation initiatives were measured over time.

5. Research findings

As a result of the research conducted since 2000, a number of chang

es have been made to the SCM framework and to our thinking about

SCM. The definition of SCM developed in 1995 and reported in

Lambert and Cooper (2000) was updated because it did not mention:

relationships,network of organizations or that the processes were

cross-functional. In 2013, we worked with the executive members of

the research center to craft the following new definition:

“Supply chain management is the management of relationships in

the network of organizations, from end customers through original

suppliers, using key cross-functional business processes to create

value for customers and other stakeholders” (Lambert, 2014, p. 2).

It had become common to say that competition is no longer between

companies,but it is “supply chain versus supply chain” (Lambert &

Cooper, 2000, p. 65). We have changed our minds about this. While sup

ply chain versus supply chain has some appeal given that companies

exist in supply chains, it is not technically correct. For the competition

to be supply chain versus supply chain, there would have to be a team

“A” playing a team “B”. When does this happen? The Coca-Cola Compa-

ny and PepsiCo Inc. both purchase sweeteners from Cargill and packag-

ing from the Graham Packaging Company,and in many cases,their

products are sold to the same retail customers. This overlapping of sup-

ply chains is the rule and not the exception. Fig. 3 illustrates how the

supply chains of major competitors can overlap. For example, the oral

care businesses of Colgate-Palmolive, P&G and Unilever. If all three com

panies purchase from many of the same suppliers and sell to the same

retailers, how can it be supply chain versus supply chain? It is not! If ex-

ecutives at Colgate-Palmolive manage relationships with suppliers and

customers better than the executives at P&G and Unilever,Colgate-

Palmolive will win more often.

Thus, supply chain management is actually about relationship man-

agement (Dyer & Singh, 1998; Piercy, 2009). A supply chain is managed

link-by-link, relationship-by-relationship and the organizations that

manage these relationships best will win (Lambert & Pohlen, 2001).

The links in the chain are formed by the customer relationship manage-

ment process and the supplier relationship management process. For

this reason, management needs tools that can be used to structure the

key relationships (Varoutsa & Scapens, 2015) that are identified during

the segmentation that occurs when implementing the customer rela-

tionship management and the supplier relationship management pro-

cesses. As part of our research, we have developed two tools that can

be used for structuring key business relationships: The Partnership

Model and The Collaboration Framework.

The Partnership Model (Lambert et al., 1996a) was developed prior

to the 2000 Industrial Marketing Management article and at the time

we had no idea that it would be a key tool for implementing the SCM

framework. Now, we realize that SCM is really about relationship

5D.M. Lambert, M.G. Enz / Industrial Marketing Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx

Please cite this article as: Lambert, D.M., & Enz, M.G., Issues in Supply Chain Management: Progress and potential, Industrial Marketing M

ment (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.12.002

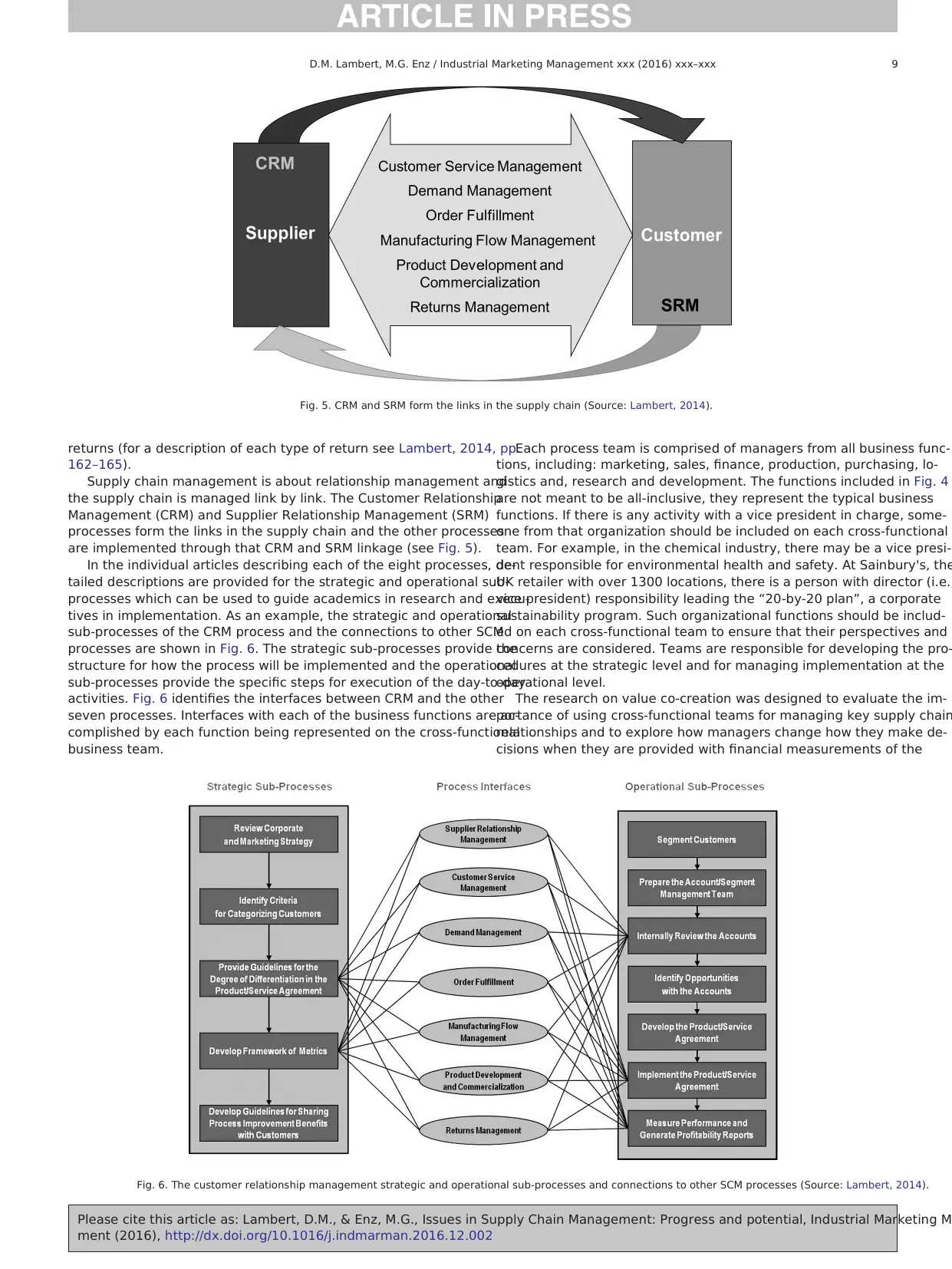

management and the Partnership Model provides a structure for devel-

oping key relationships. The Partnership Model separates the drivers,

the facilitators, the components and the outcomes of partnership into

four separate areas for attention. Drivers are the compelling reasons to

partner and must be assessed independently by each organization in

order to arrive at a common vision of the business benefits associated

with building more closeness into the relationship. Then, the managers

from each organization present their drivers to the other organization in

order to set expectations. Facilitators are characteristics of the two firms

that will help or hinder the partnership development process and they

are assessed by the two groups together. Drivers and facilitators deter-

mine the potential for partnership: Type I, Type II or Type III (Lambert

et al., 1996a). Components are the managerially controllable elements

that should be implemented at a prescribed level depending on the

type of partnership. Outcomes measure the extent to which each firm

achieves its drivers.

Using the Partnership Model to tailor a relationship requires a one

and one-half day session. The correct team from each firm must be iden-

tified and committed to a meeting time. These teams should include top

managers, middle managers, operations personnel and staff personnel.

A broad mix,both in terms of the management level and functional

expertise, is required in order to ensure that all perspectives are consid-

ered. The process is not about whether to have a business relationship;

it is about the style of the relationship.

The Collaboration Framework was developed in 2008 (first pub-

lished in Lambert,Knemeyer,& Gardner,2010) and is appropriate

when one of two conditions are met. First, the relationship is new and

individuals in the two organizations do not have enough information

about each other and/or their joint business opportunities to score the

drivers and facilitators in a full partnership meeting, but significant po-

tential from collaboration exists. Second, the two organizations have

significant joint business at stake and managers want to develop a

joint plan for the next 18 to 24 months. The Collaboration Framework

provides a structure for developing and implementing product and ser-

vice agreements (PSAs) with key customers and suppliers that are part

of implementing the customer relationship management and supplier

relationship management processes.

The Collaboration Framework is comprised of six activities: 1) assess

drivers for each company; 2) align expectations; 3) develop action

plans; 4) develop product and service agreement; 5) review perfor-

mance; and,6) reexamine drivers.Assess drivers requires that each