Chinese Business Review, Vol. 14, No. 7, July 2015: Project Delays

VerifiedAdded on 2023/01/11

|48

|26319

|33

Report

AI Summary

The provided document is an excerpt from the Chinese Business Review, Volume 14, Number 7, published in July 2015. It features an article focusing on the effects of delayed payment of contractors on the completion of infrastructural projects, specifically using the Sondu-Miriu hydropower project in Kisumu County, Kenya, as a case study. The study, conducted in May 2011, utilized a causal-comparative design and collected primary data from 39 senior management staff. It examined the relative importance of delayed payments compared to other contractual delays and assessed the perceived effects of delayed payments on project completion. The findings reveal that delayed payments significantly impacted the project, leading to reduced productivity, increased costs, re-scheduling of works, and potential delays in completion. The study emphasizes the importance of timely payments to contractors for ensuring project success and recommends mitigative measures against potential risks associated with fund disbursement.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Chinese Business Review

Volume 14, Number 7, July 2015 (Serial Number 145)

David

David Publishing Company

www.davidpublisher.com

PublishingDavid

Volume 14, Number 7, July 2015 (Serial Number 145)

David

David Publishing Company

www.davidpublisher.com

PublishingDavid

Publication Information:

Chinese Business Review is published monthly in hard copy (ISSN 1537-1506) and online by David Publishing

Company located at 1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA.

Aims and Scope:

Chinese Business Review, a monthly professional academic journal, covers all sorts of researches on Economic

Research, Management Theory and Practice, Experts Forum, Macro or Micro Analysis, Economical Studies of Theory

and Practice, Finance and Finance Management, Strategic Management, and Human Resource Management, and other

latest findings and achievements from experts and scholars all over the world.

Editorial Board Members:

Kathleen G. Rust (USA)

Moses N. Kiggundu (Canada)

Helena Maria Baptista Alves (Portugal)

Marcello Signorelli (Italy)

Doaa Mohamed Salman (Egypt)

Amitabh Deo Kodwani (Poland)

Lorena Blasco-Arcas (Spain)

Yutaka Kurihara (Japan)

Shelly SHEN (China)

Salvatore Romanazzi (Italy)

Saeb Farhan Al Ganideh (Jordan)

GEORGE ASPRIDIS (Greece)

Agnieszka Izabela Baruk (Poland)

Goran Kutnjak (Croatia)

Elenica Pjero (Albania)

Kazuhiro TAKEYASU (Japan)

Mary RÉDEI (Hungary)

Bonny TU (China)

Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web Submission, or

E-mail to economists@davidpublishing.com, china4review@hotmail.com. Submission guidelines and Web

Submission system are available at http://www.davidpublisher.com.

Editorial Office:

1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA E-mail: economists@davidpublishing.com

Copyright© 2015 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing

Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international

convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including

various websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be

considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation, however, all

the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author.

Abstracted / Indexed in:

Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA

Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, USA

ProQuest/CSA Social Science Collection, PAIS, USA

Cabell’s Directory of Publishing Opportunities, USA

Summon Serials Solutions, USA

ProQuest

Google Scholar

Chinese Database of CEPS, OCLC

ProQuest Asian Business and Reference

Index Copernicus, Poland

Qualis/Capes Index, Brazil

NSD/DBH, Norway

Universe Digital Library S/B, ProQuest, Malaysia

Polish Scholarly Bibliography (PBN), Poland

SCRIBD (Digital Library), USA

PubMed, USA

Open Academic Journals Index (OAJI), Russian

Electronic Journals Library (EZB), Germany

Journals Impact Factor (JIF) (0.5)

WZB Berlin Social Science Center, Germany

UniMelb, Australia

NewJour, USA

InnoSpace, USA

Publicon Science Index, USA

Turkish Education Index, Turkey

Universal Impact Factor, USA

BASE, Germany

WorldCat, USA

Subscription Information:

Print $520 Online $360 Print and Online $680

David Publishing Company, 1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA

Tel: +1-323-984-7526, 323-410-1082 Fax: +1-323-984-7374, 323-908-0457

E-mail: order@davidpublishing.com

Digital Cooperative Company: www.bookan.com.cn

David Publishing Company

www.davidpublisher.com

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

Chinese Business Review is published monthly in hard copy (ISSN 1537-1506) and online by David Publishing

Company located at 1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA.

Aims and Scope:

Chinese Business Review, a monthly professional academic journal, covers all sorts of researches on Economic

Research, Management Theory and Practice, Experts Forum, Macro or Micro Analysis, Economical Studies of Theory

and Practice, Finance and Finance Management, Strategic Management, and Human Resource Management, and other

latest findings and achievements from experts and scholars all over the world.

Editorial Board Members:

Kathleen G. Rust (USA)

Moses N. Kiggundu (Canada)

Helena Maria Baptista Alves (Portugal)

Marcello Signorelli (Italy)

Doaa Mohamed Salman (Egypt)

Amitabh Deo Kodwani (Poland)

Lorena Blasco-Arcas (Spain)

Yutaka Kurihara (Japan)

Shelly SHEN (China)

Salvatore Romanazzi (Italy)

Saeb Farhan Al Ganideh (Jordan)

GEORGE ASPRIDIS (Greece)

Agnieszka Izabela Baruk (Poland)

Goran Kutnjak (Croatia)

Elenica Pjero (Albania)

Kazuhiro TAKEYASU (Japan)

Mary RÉDEI (Hungary)

Bonny TU (China)

Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web Submission, or

E-mail to economists@davidpublishing.com, china4review@hotmail.com. Submission guidelines and Web

Submission system are available at http://www.davidpublisher.com.

Editorial Office:

1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA E-mail: economists@davidpublishing.com

Copyright© 2015 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing

Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international

convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including

various websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be

considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation, however, all

the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author.

Abstracted / Indexed in:

Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA

Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, USA

ProQuest/CSA Social Science Collection, PAIS, USA

Cabell’s Directory of Publishing Opportunities, USA

Summon Serials Solutions, USA

ProQuest

Google Scholar

Chinese Database of CEPS, OCLC

ProQuest Asian Business and Reference

Index Copernicus, Poland

Qualis/Capes Index, Brazil

NSD/DBH, Norway

Universe Digital Library S/B, ProQuest, Malaysia

Polish Scholarly Bibliography (PBN), Poland

SCRIBD (Digital Library), USA

PubMed, USA

Open Academic Journals Index (OAJI), Russian

Electronic Journals Library (EZB), Germany

Journals Impact Factor (JIF) (0.5)

WZB Berlin Social Science Center, Germany

UniMelb, Australia

NewJour, USA

InnoSpace, USA

Publicon Science Index, USA

Turkish Education Index, Turkey

Universal Impact Factor, USA

BASE, Germany

WorldCat, USA

Subscription Information:

Print $520 Online $360 Print and Online $680

David Publishing Company, 1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA

Tel: +1-323-984-7526, 323-410-1082 Fax: +1-323-984-7374, 323-908-0457

E-mail: order@davidpublishing.com

Digital Cooperative Company: www.bookan.com.cn

David Publishing Company

www.davidpublisher.com

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Chinese

Business Review

Volume 14, Number 7, July 2015 (Serial Number 145)

Contents

Management

Effects of Delayed Payment of Contractors on the Completion of Infrastructural Projects:

A Case of Sondu-Miriu Hydropower Project, Kisumu County, Kenya 325

Maurice Paul Okeyo, Charles Mallans Rambo, Paul Amollo Odundo

Instruments for Analysis of Knowledge Management in Operators Companies of Metropolitan

Transport Systems 337

Manoel Agrasso Neto, Andre Ricardo Wesendonck, Viviane D’Barsoles Gonçalves Werutzky

IT Influence on Organizational Structure: Empirical Studies Among Polish Organizations 348

Katarzyna Tworek

Systems Analysis in the Study of the Political Elite 354

Nadezhda Ponomarenko

Privatizing War 360

Kenneth Shaw

Business Review

Volume 14, Number 7, July 2015 (Serial Number 145)

Contents

Management

Effects of Delayed Payment of Contractors on the Completion of Infrastructural Projects:

A Case of Sondu-Miriu Hydropower Project, Kisumu County, Kenya 325

Maurice Paul Okeyo, Charles Mallans Rambo, Paul Amollo Odundo

Instruments for Analysis of Knowledge Management in Operators Companies of Metropolitan

Transport Systems 337

Manoel Agrasso Neto, Andre Ricardo Wesendonck, Viviane D’Barsoles Gonçalves Werutzky

IT Influence on Organizational Structure: Empirical Studies Among Polish Organizations 348

Katarzyna Tworek

Systems Analysis in the Study of the Political Elite 354

Nadezhda Ponomarenko

Privatizing War 360

Kenneth Shaw

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Chinese Business Review, July 2015, Vol. 14, No. 7, 325-336

doi: 10.17265/1537-1506/2015.07.001

Effects of Delayed Payment of Contractors on the Completion of

Infrastructural Projects: A Case of Sondu-Miriu Hydropower

Project, Kisumu County, Kenya

Maurice Paul Okeyo, Charles Mallans Rambo, Paul Amollo Odundo

University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

Sondu-Miriu hydropower (SMHP) project experienced delay for about five years and one of the contributing

factors was delayed payment of the contractor, with ripples effect extending down the contractual hierarchy. This

study assessed the effects of delayed payment of the contractor on the completion of SMHP project in Kisumu County,

Kenya. More specifically, the study addressed two research questions: What is the relative importance of delayed

payment of the contractor compared to other forms of contractual delays? What is the perceived effect of delayed

payment of the contractor on the project’s completion? A causal-comparative design was adopted and primary data

sourced in May 2011 from 39 senior management staff of contractual parties. Relative importance index (RII) was

used to determine the relative importance of perceived effects of delayed payment of the contractor on the project’s

completion; while Kendell’s coefficient of concordance was applied to determine the degree of agreement among

participants regarding their perceived effects of delayed payment. The study found that delayed payment of the

contractor affected the project by causing: loss of productivity and efficiency (71.8%); increase in time-related

costs (71.8%); re-scheduling and re-sequencing of works (69.2%); extension of time and acceleration (69.2%); as

well as prevention of early completion (53.8%). The study concludes that timely payment of contractors is crucial

for ensuring the continuity of works and completion of infrastructural projects within time, budget, and quality

specifications. The study recommends the need for appropriate mitigative measures against potential risks, such as

delayed disbursement of funds by external financiers, delayed approval of contractors’ payment requests, as well as

community participation and involvement of civil society to influence accountability in the management of project

funds and expedite disbursement of funds for subsequent project phases.

Keywords: infrastructural projects, contractor, delayed payment, budget overrun, time overrun

Introduction

Sondu-Miriu hydropower (SMHP) project is located in Kisumu County, about 337 kilometres from

Acknowledgement: Special thanks go to the University of Nairobi for granting opportunity to the first author to pursue his

Master of Arts Degree Project Planning and Management. Secondly, all the participants who took their time to provide the

requisite information are thanked. Thirdly, the support provided by Tom Odhiambo in reviewing the manuscript is acknowledged.

Maurice Paul Okeyo, M.A., project planning and management, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

Charles Mallans Rambo, Ph.D., extra mural studies, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

Paul Amollo Odundo, Ph.D., education administration, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Charles Mallans Rambo, P.O. Box 30197-00100, Nairobi,

Kenya. E-mail: crambo@uonbi.ac.ke; rambocharls@gmail.com.

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

doi: 10.17265/1537-1506/2015.07.001

Effects of Delayed Payment of Contractors on the Completion of

Infrastructural Projects: A Case of Sondu-Miriu Hydropower

Project, Kisumu County, Kenya

Maurice Paul Okeyo, Charles Mallans Rambo, Paul Amollo Odundo

University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

Sondu-Miriu hydropower (SMHP) project experienced delay for about five years and one of the contributing

factors was delayed payment of the contractor, with ripples effect extending down the contractual hierarchy. This

study assessed the effects of delayed payment of the contractor on the completion of SMHP project in Kisumu County,

Kenya. More specifically, the study addressed two research questions: What is the relative importance of delayed

payment of the contractor compared to other forms of contractual delays? What is the perceived effect of delayed

payment of the contractor on the project’s completion? A causal-comparative design was adopted and primary data

sourced in May 2011 from 39 senior management staff of contractual parties. Relative importance index (RII) was

used to determine the relative importance of perceived effects of delayed payment of the contractor on the project’s

completion; while Kendell’s coefficient of concordance was applied to determine the degree of agreement among

participants regarding their perceived effects of delayed payment. The study found that delayed payment of the

contractor affected the project by causing: loss of productivity and efficiency (71.8%); increase in time-related

costs (71.8%); re-scheduling and re-sequencing of works (69.2%); extension of time and acceleration (69.2%); as

well as prevention of early completion (53.8%). The study concludes that timely payment of contractors is crucial

for ensuring the continuity of works and completion of infrastructural projects within time, budget, and quality

specifications. The study recommends the need for appropriate mitigative measures against potential risks, such as

delayed disbursement of funds by external financiers, delayed approval of contractors’ payment requests, as well as

community participation and involvement of civil society to influence accountability in the management of project

funds and expedite disbursement of funds for subsequent project phases.

Keywords: infrastructural projects, contractor, delayed payment, budget overrun, time overrun

Introduction

Sondu-Miriu hydropower (SMHP) project is located in Kisumu County, about 337 kilometres from

Acknowledgement: Special thanks go to the University of Nairobi for granting opportunity to the first author to pursue his

Master of Arts Degree Project Planning and Management. Secondly, all the participants who took their time to provide the

requisite information are thanked. Thirdly, the support provided by Tom Odhiambo in reviewing the manuscript is acknowledged.

Maurice Paul Okeyo, M.A., project planning and management, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

Charles Mallans Rambo, Ph.D., extra mural studies, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

Paul Amollo Odundo, Ph.D., education administration, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Charles Mallans Rambo, P.O. Box 30197-00100, Nairobi,

Kenya. E-mail: crambo@uonbi.ac.ke; rambocharls@gmail.com.

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

A CASE OF SONDU-MIRIU HYDROPOWER PROJECT, KISUMU COUNTY, KENYA326

Nairobi. The project is a run-of-the-river scheme, relying on the water from the Sondu-Miriu River, flowing

into Lake Victoria. The project was initiated by Kenya Electricity Generating Company Limited (KenGen) to

inject an additional 80 mega watts of electricity into the national grid and more particularly to support the

economy of western Kenya, which had a power deficit of about 75 mega watts at the time the project was

initiated in 1995 (KenGen, 2004).

The project was financed by the Government of Japan through Japanese International Corporation Agency

(JICA), under Overseas Development Agency (ODA) loans at a cost of KES 18 billion (JICA, 1985). The loan

was disbursed in two phases: in 1999, where KenGen received about 40% of the approved funds; in 2004,

where the remaining 60% of the funds was disbursed. Phase I funding covered civil works and engineering

services; while Phase II funding covered remaining civil works, hydro-mechanical works, generating

equipment, and transmission line works (KenGen, 2004; Nippon Koei, 2008). According to the initial

construction plan, the project was supposed to be completed by December 2005. However, due to delay, the

project’s completion date was revised to November 2011. Among the factors that contributed to the delay was

delay in the payment of contractors for completed works (Nippon Koei, 2008; Abiero, 2010).

As noted by Alaghbari, Kadir, Salim, and Ernawati (2007), late and inconsistent payment of contractors

for completed works is one of the critical factors, causing delays in the completion of infrastructural projects in

developing countries. Delay in payment at the higher end of hierarchy is likely to trickle down the chain of

contracts (Construction Industry Working Group on Payment, 2007). More specifically, delay in payment of

completed works is likely to constrain contractors’ cash flow, which in turn might affect timely payment of

sub-contractors, workers, suppliers, and service providers. Regarding human labor, delayed payment of

workers is likely to affect motivation, punctuality, productivity, honesty, pace of works, and completion of

construction projects.

Memon, Rahman, Aziz, Ravish, and Hanas (2011) have associated prolonged delays in payment with

consequences, such as high risk of industrial disputes, wanton destruction of property, and a high turn-over of

workers; while Raj and Kothai (2014) pointed out that timely payment of workers is necessary for maintaining

motivation, willingness, confidence, discipline, and cheerfulness to perform work. Furthermore, Abdul-Rahman,

Takim, and Min (2009) linked delayed payment to causal factors, such as clients’ poor financial and business

management; financial impropriety and political interference; inaccurate valuation for completed works; as well

as insufficient documentation and information for valuation, among other factors. Whereas causes of delays in

the construction of infrastructural projects have attracted many studies, particularly in developing economies,

the effects of such delays have not received as much attention (Sambasivan & Soon, 2007; Aziz, 2013;

Owolabi et al., 2014). More specifically, few studies, such as Sambasivan and Soon (2007), Abdul-Rahman et

al. (2009), and Memon et al. (2011), have focused on the effects of delayed payment of contractors on the

completion of infrastructural projects.

In Kenya, no studies have ever assessed the effect of delayed payment of contractors on the completion of

infrastructural facilities. This study examined the effects of delayed payment of contractors on the completion

of SMHP project by aggregating perspectives of the project’s key stakeholders, including KenGen (the

employer), Nippon Koei Company Limited (the engineer), Sinohydro (the contractor), and JICA (the financier).

The study further applied a coefficient of concordance to determine the degree of agreement among the four

categories of participants with respect to their ranking. The study addressed two research questions: What is the

relative importance of delayed payment of contractors compared to other forms of contractual delays? What is

Nairobi. The project is a run-of-the-river scheme, relying on the water from the Sondu-Miriu River, flowing

into Lake Victoria. The project was initiated by Kenya Electricity Generating Company Limited (KenGen) to

inject an additional 80 mega watts of electricity into the national grid and more particularly to support the

economy of western Kenya, which had a power deficit of about 75 mega watts at the time the project was

initiated in 1995 (KenGen, 2004).

The project was financed by the Government of Japan through Japanese International Corporation Agency

(JICA), under Overseas Development Agency (ODA) loans at a cost of KES 18 billion (JICA, 1985). The loan

was disbursed in two phases: in 1999, where KenGen received about 40% of the approved funds; in 2004,

where the remaining 60% of the funds was disbursed. Phase I funding covered civil works and engineering

services; while Phase II funding covered remaining civil works, hydro-mechanical works, generating

equipment, and transmission line works (KenGen, 2004; Nippon Koei, 2008). According to the initial

construction plan, the project was supposed to be completed by December 2005. However, due to delay, the

project’s completion date was revised to November 2011. Among the factors that contributed to the delay was

delay in the payment of contractors for completed works (Nippon Koei, 2008; Abiero, 2010).

As noted by Alaghbari, Kadir, Salim, and Ernawati (2007), late and inconsistent payment of contractors

for completed works is one of the critical factors, causing delays in the completion of infrastructural projects in

developing countries. Delay in payment at the higher end of hierarchy is likely to trickle down the chain of

contracts (Construction Industry Working Group on Payment, 2007). More specifically, delay in payment of

completed works is likely to constrain contractors’ cash flow, which in turn might affect timely payment of

sub-contractors, workers, suppliers, and service providers. Regarding human labor, delayed payment of

workers is likely to affect motivation, punctuality, productivity, honesty, pace of works, and completion of

construction projects.

Memon, Rahman, Aziz, Ravish, and Hanas (2011) have associated prolonged delays in payment with

consequences, such as high risk of industrial disputes, wanton destruction of property, and a high turn-over of

workers; while Raj and Kothai (2014) pointed out that timely payment of workers is necessary for maintaining

motivation, willingness, confidence, discipline, and cheerfulness to perform work. Furthermore, Abdul-Rahman,

Takim, and Min (2009) linked delayed payment to causal factors, such as clients’ poor financial and business

management; financial impropriety and political interference; inaccurate valuation for completed works; as well

as insufficient documentation and information for valuation, among other factors. Whereas causes of delays in

the construction of infrastructural projects have attracted many studies, particularly in developing economies,

the effects of such delays have not received as much attention (Sambasivan & Soon, 2007; Aziz, 2013;

Owolabi et al., 2014). More specifically, few studies, such as Sambasivan and Soon (2007), Abdul-Rahman et

al. (2009), and Memon et al. (2011), have focused on the effects of delayed payment of contractors on the

completion of infrastructural projects.

In Kenya, no studies have ever assessed the effect of delayed payment of contractors on the completion of

infrastructural facilities. This study examined the effects of delayed payment of contractors on the completion

of SMHP project by aggregating perspectives of the project’s key stakeholders, including KenGen (the

employer), Nippon Koei Company Limited (the engineer), Sinohydro (the contractor), and JICA (the financier).

The study further applied a coefficient of concordance to determine the degree of agreement among the four

categories of participants with respect to their ranking. The study addressed two research questions: What is the

relative importance of delayed payment of contractors compared to other forms of contractual delays? What is

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A CASE OF SONDU-MIRIU HYDROPOWER PROJECT, KISUMU COUNTY, KENYA 327

the perceived effect of delayed payment of contractors on the project’s completion?

The purpose of the study was to inform stakeholders about the potential negative effects of delayed

payment of contractors on the completion of large infrastructural projects. The study also intended to contribute

to existing literature on infrastructural project delays, particularly in Sub-Sahara African (SSA) countries, with

a view to sensitizing stakeholders to work towards lessening such delays, in order to deliver inspirational,

durable, efficient, and safe infrastructural facilities within scheduled timeframes and allocated budgets.

Enhancing efficiency in the construction of infrastructural facilities is particularly important for SSA countries,

where available resources cannot suffice the need for more infrastructural facilities and where nearly half of the

population live on less than US$ 1.25 a day (World Bank, 2015; Gutman, Sy, & Chattopadhyay, 2015).

Literature Review

Infrastructural projects are considered successful when delivered within scheduled duration, allocated

budget, and specified quality (Majid, 2006; Owolabi et al., 2014). Delay in the completion of infrastructural

facilities is a critical challenge with a global dimension, often leading to increased construction costs due to

time extension or acceleration as well as loss of productivity, disruption of work, loss of revenue through

lawsuits between contractual parties, and project abandonment (Sambasivan & Soon, 2007; Owolabi et al.,

2014). Many SSA economies experience losses amounting to billions of dollars, as a result of delayed

completion of infrastructural projects, which undermines the noble goal of poverty reduction (Gutman et al.,

2015). Delay in the completion of infrastructural projects has significant cost implications, which in turn bears

far-reaching consequences in the lives of citizens, especially in SSA countries. Costs arising due to such delays

often manifest themselves in terms of accumulated interest on loans, high cost of maintaining management staff,

as well as continuous escalation in wages and material prices.

Studies conducted in various contexts have deduced that although delay in the completion of infrastructural

projects is a global phenomenon, it appears to be more common in developing than in developed countries

(Sambasivan & Soon, 2007; Alaghbari et al., 2007; Aziz, 2013). Among the developed countries, delay in the

completion of infrastructural projects has been reported in Canada, the United States, Australia, and Britain,

among others. In Canada for instance, De Souza (2009) attributed delays in the completion of infrastructural

projects to various factors, including reduced funding by sponsors, communication breakdown, delayed

disbursement of funds, poor site management by contractors, and tedious legislative procedures. In the United

States, SNL Financial (2010) reported delay in the completion of a pipeline project connecting Florida State

and Bahamas, particularly due to design changes; while Baldwin and Manthei (1971) associated project delays

in the United States with weather vagaries, labor supply, and poor management of sub-contractors.

In developing countries, delays in the completion of infrastructural projects have been reported in India,

Malaysia, Indonesia, Qatar, Jordan, Egypt, Ghana, South Africa, and Kenya, among other countries. In India, a

government Infrastructure Delay Report of 2006 reported delays in the completion of a rail project in West

Bengal and a coal project for about three and two decades, respectively, which were attributed to slow design

processes and late disbursement of project funds (Government of India, 2006). In Qatar, a Public Works Report

of 2009 linked delays in the completion of about one-third of infrastructural projects to contractors lack of

capacity, escalation of construction material prices, prolonged transfer of land ownership rights to contractors,

deferral of payments due to design issues, as well as legislative challenges in the procurement of necessary

equipment and machinery from overseas market (Government of Qatar, 2009).

the perceived effect of delayed payment of contractors on the project’s completion?

The purpose of the study was to inform stakeholders about the potential negative effects of delayed

payment of contractors on the completion of large infrastructural projects. The study also intended to contribute

to existing literature on infrastructural project delays, particularly in Sub-Sahara African (SSA) countries, with

a view to sensitizing stakeholders to work towards lessening such delays, in order to deliver inspirational,

durable, efficient, and safe infrastructural facilities within scheduled timeframes and allocated budgets.

Enhancing efficiency in the construction of infrastructural facilities is particularly important for SSA countries,

where available resources cannot suffice the need for more infrastructural facilities and where nearly half of the

population live on less than US$ 1.25 a day (World Bank, 2015; Gutman, Sy, & Chattopadhyay, 2015).

Literature Review

Infrastructural projects are considered successful when delivered within scheduled duration, allocated

budget, and specified quality (Majid, 2006; Owolabi et al., 2014). Delay in the completion of infrastructural

facilities is a critical challenge with a global dimension, often leading to increased construction costs due to

time extension or acceleration as well as loss of productivity, disruption of work, loss of revenue through

lawsuits between contractual parties, and project abandonment (Sambasivan & Soon, 2007; Owolabi et al.,

2014). Many SSA economies experience losses amounting to billions of dollars, as a result of delayed

completion of infrastructural projects, which undermines the noble goal of poverty reduction (Gutman et al.,

2015). Delay in the completion of infrastructural projects has significant cost implications, which in turn bears

far-reaching consequences in the lives of citizens, especially in SSA countries. Costs arising due to such delays

often manifest themselves in terms of accumulated interest on loans, high cost of maintaining management staff,

as well as continuous escalation in wages and material prices.

Studies conducted in various contexts have deduced that although delay in the completion of infrastructural

projects is a global phenomenon, it appears to be more common in developing than in developed countries

(Sambasivan & Soon, 2007; Alaghbari et al., 2007; Aziz, 2013). Among the developed countries, delay in the

completion of infrastructural projects has been reported in Canada, the United States, Australia, and Britain,

among others. In Canada for instance, De Souza (2009) attributed delays in the completion of infrastructural

projects to various factors, including reduced funding by sponsors, communication breakdown, delayed

disbursement of funds, poor site management by contractors, and tedious legislative procedures. In the United

States, SNL Financial (2010) reported delay in the completion of a pipeline project connecting Florida State

and Bahamas, particularly due to design changes; while Baldwin and Manthei (1971) associated project delays

in the United States with weather vagaries, labor supply, and poor management of sub-contractors.

In developing countries, delays in the completion of infrastructural projects have been reported in India,

Malaysia, Indonesia, Qatar, Jordan, Egypt, Ghana, South Africa, and Kenya, among other countries. In India, a

government Infrastructure Delay Report of 2006 reported delays in the completion of a rail project in West

Bengal and a coal project for about three and two decades, respectively, which were attributed to slow design

processes and late disbursement of project funds (Government of India, 2006). In Qatar, a Public Works Report

of 2009 linked delays in the completion of about one-third of infrastructural projects to contractors lack of

capacity, escalation of construction material prices, prolonged transfer of land ownership rights to contractors,

deferral of payments due to design issues, as well as legislative challenges in the procurement of necessary

equipment and machinery from overseas market (Government of Qatar, 2009).

A CASE OF SONDU-MIRIU HYDROPOWER PROJECT, KISUMU COUNTY, KENYA328

In Malaysia, Sambasivan and Soon (2007) identified causes of delays in the completion of infrastructural

projects, including contractor’s improper planning, poor site management, inadequate experience, inconsistent

flow of payments for completed work, poor management of sub-contractors, inconsistent communication

between parties, as well as shortage of materials, equipment, and labor. In South Africa, a government report

linked infrastructural project delays with changes in project design, inconsistent flow of financial resources, and

contractor’s lack of capacity to deliver (Government of South Africa, 1999). In Ghana, delay in payments, poor

contractor management, delays in material procurement, poor technical performances, and escalation of

material prices were identified as key factors accounting for about 80% of delays in the completion of

infrastructural projects (Frimpong, Olowoye, & Crawford, 2003).

In Kenya, delays in the completion of infrastructural facilities have been associated with factors, such as

poor financial management by government agencies, inadequate designs, and poor management of the

construction process by contractors (Talukhaba, 1999). Arguably, these factors are compounded by secondary

factors, such as poor management of materials and equipment by contractors, inadequate recognition and

response to risks emanating from the physical and socio-economic environments, as well as inadequate regard

for stakeholders’ needs (Talukhaba, 1999). Another study conducted by Ondari and Gekara (2013) reported

significant correlation between project delays and factors, such as management support (r = 0.625), design

specifications (r = 0.836), contractor’s capacity (r = 0.567), and supervision capacity (r = 0.712).

Delays in the completion of infrastructural facilities were also identified by Abiero (2010) in the study that

examined challenges of stakeholder management in implementation of SMHP project in Kenya. The study

reported that the Phase II of the SMHP project delayed for four and half years due to delays in the release of

funds, which in turn was caused by delay in the management of issues arising, including unsatisfactory

accountability for funds released in the previous phase and improper management of dissenting voices among

stakeholders (Abiero, 2010). The study further cited cases of delayed infrastructural projects in the lake region

of Kenya, including the Kisii-Chemosite Road, which delayed for more than 15 years, as well as the Nyanza

Provincial Headquarters, which stalled for more than two decades. The study noted that delayed completion of

the projects has led to loss of both time and possession utility of the projects.

The literature review shows that most studies focused on causes of delays in the completion of

infrastructural projects in developed and developing countries, with a few to explicitly identifying delayed

payment of contractors, as one of the factors contributing to delayed completion of the cited projects. More still,

no study has ever examined the effects of delayed payment of contractors on the completion of infrastructural

projects.

Methodology

The study adopted a causal-comparative design, which permitted the application of quantitative approaches

in data collection, processing, and analysis. Causal-comparative designs employ natural selection principle,

rather than manipulation of dependent variables to reveal relationships with independent variables (Oso & Onen,

2005). Self-administered questionnaires were issued to the management staff of contracting parties to source

information on causes of contractual delays and effects of delayed payment of the contractor on the completion

SMHP project. Primary data were supplemented with secondary data sourced from the project archives.

The study targeted senior management staff of SMHP project, affiliated to all contracting parties,

including KenGen (the employer), Nippon Koei Company Limited (the engineer), Sinohydro (the contractor),

In Malaysia, Sambasivan and Soon (2007) identified causes of delays in the completion of infrastructural

projects, including contractor’s improper planning, poor site management, inadequate experience, inconsistent

flow of payments for completed work, poor management of sub-contractors, inconsistent communication

between parties, as well as shortage of materials, equipment, and labor. In South Africa, a government report

linked infrastructural project delays with changes in project design, inconsistent flow of financial resources, and

contractor’s lack of capacity to deliver (Government of South Africa, 1999). In Ghana, delay in payments, poor

contractor management, delays in material procurement, poor technical performances, and escalation of

material prices were identified as key factors accounting for about 80% of delays in the completion of

infrastructural projects (Frimpong, Olowoye, & Crawford, 2003).

In Kenya, delays in the completion of infrastructural facilities have been associated with factors, such as

poor financial management by government agencies, inadequate designs, and poor management of the

construction process by contractors (Talukhaba, 1999). Arguably, these factors are compounded by secondary

factors, such as poor management of materials and equipment by contractors, inadequate recognition and

response to risks emanating from the physical and socio-economic environments, as well as inadequate regard

for stakeholders’ needs (Talukhaba, 1999). Another study conducted by Ondari and Gekara (2013) reported

significant correlation between project delays and factors, such as management support (r = 0.625), design

specifications (r = 0.836), contractor’s capacity (r = 0.567), and supervision capacity (r = 0.712).

Delays in the completion of infrastructural facilities were also identified by Abiero (2010) in the study that

examined challenges of stakeholder management in implementation of SMHP project in Kenya. The study

reported that the Phase II of the SMHP project delayed for four and half years due to delays in the release of

funds, which in turn was caused by delay in the management of issues arising, including unsatisfactory

accountability for funds released in the previous phase and improper management of dissenting voices among

stakeholders (Abiero, 2010). The study further cited cases of delayed infrastructural projects in the lake region

of Kenya, including the Kisii-Chemosite Road, which delayed for more than 15 years, as well as the Nyanza

Provincial Headquarters, which stalled for more than two decades. The study noted that delayed completion of

the projects has led to loss of both time and possession utility of the projects.

The literature review shows that most studies focused on causes of delays in the completion of

infrastructural projects in developed and developing countries, with a few to explicitly identifying delayed

payment of contractors, as one of the factors contributing to delayed completion of the cited projects. More still,

no study has ever examined the effects of delayed payment of contractors on the completion of infrastructural

projects.

Methodology

The study adopted a causal-comparative design, which permitted the application of quantitative approaches

in data collection, processing, and analysis. Causal-comparative designs employ natural selection principle,

rather than manipulation of dependent variables to reveal relationships with independent variables (Oso & Onen,

2005). Self-administered questionnaires were issued to the management staff of contracting parties to source

information on causes of contractual delays and effects of delayed payment of the contractor on the completion

SMHP project. Primary data were supplemented with secondary data sourced from the project archives.

The study targeted senior management staff of SMHP project, affiliated to all contracting parties,

including KenGen (the employer), Nippon Koei Company Limited (the engineer), Sinohydro (the contractor),

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

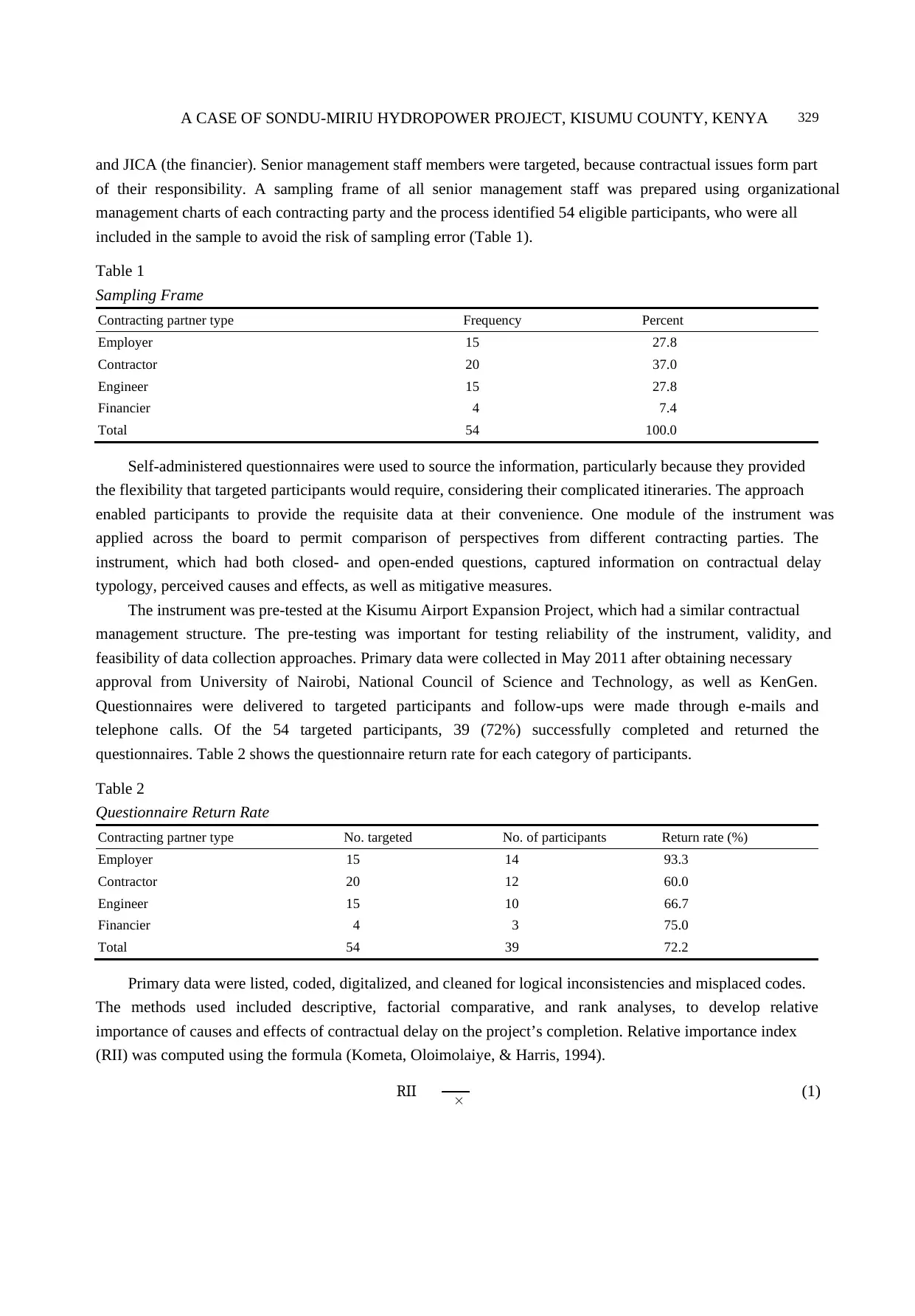

A CASE OF SONDU-MIRIU HYDROPOWER PROJECT, KISUMU COUNTY, KENYA 329

and JICA (the financier). Senior management staff members were targeted, because contractual issues form part

of their responsibility. A sampling frame of all senior management staff was prepared using organizational

management charts of each contracting party and the process identified 54 eligible participants, who were all

included in the sample to avoid the risk of sampling error (Table 1).

Table 1

Sampling Frame

Contracting partner type Frequency Percent

Employer 15 27.8

Contractor 20 37.0

Engineer 15 27.8

Financier 4 7.4

Total 54 100.0

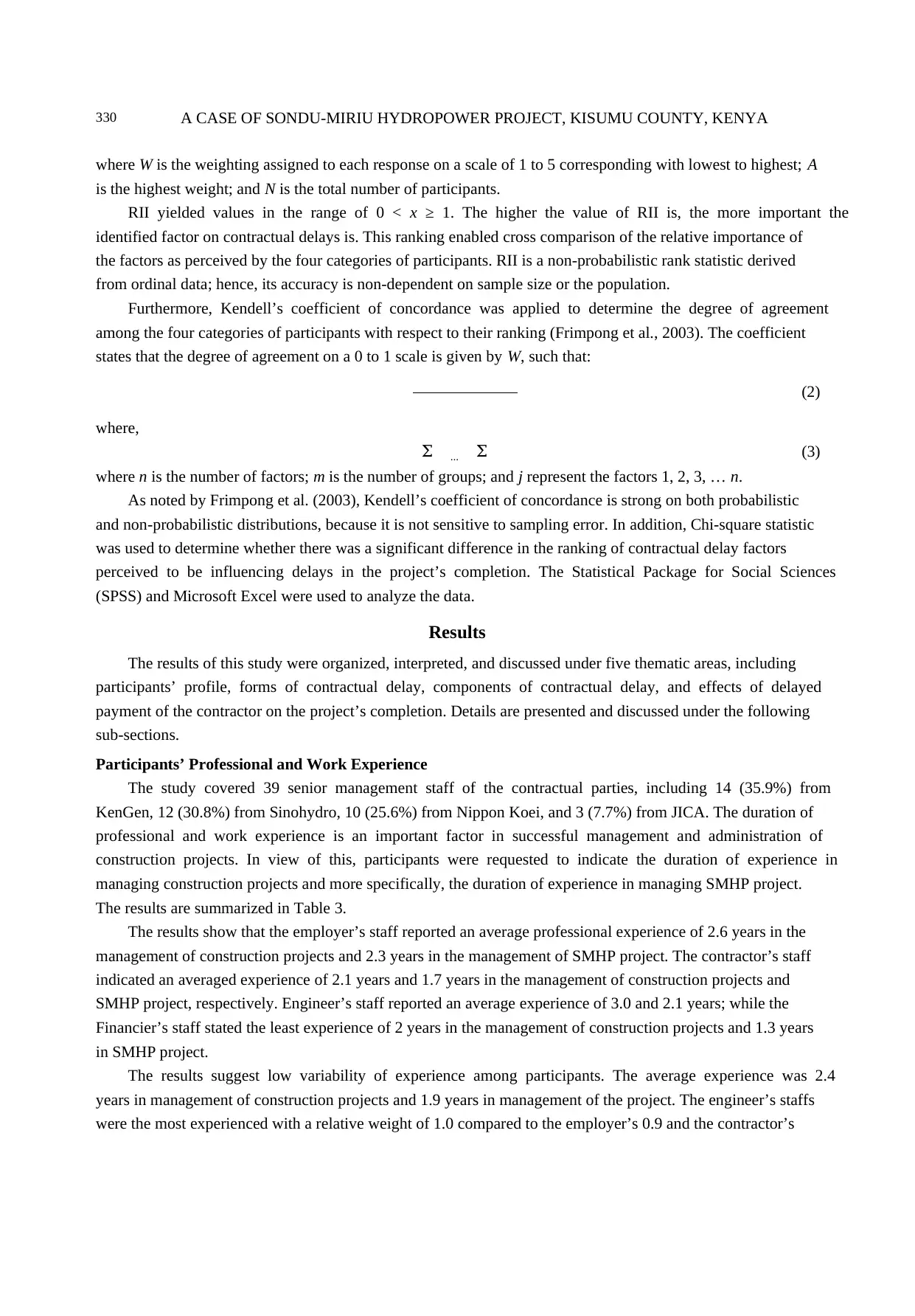

Self-administered questionnaires were used to source the information, particularly because they provided

the flexibility that targeted participants would require, considering their complicated itineraries. The approach

enabled participants to provide the requisite data at their convenience. One module of the instrument was

applied across the board to permit comparison of perspectives from different contracting parties. The

instrument, which had both closed- and open-ended questions, captured information on contractual delay

typology, perceived causes and effects, as well as mitigative measures.

The instrument was pre-tested at the Kisumu Airport Expansion Project, which had a similar contractual

management structure. The pre-testing was important for testing reliability of the instrument, validity, and

feasibility of data collection approaches. Primary data were collected in May 2011 after obtaining necessary

approval from University of Nairobi, National Council of Science and Technology, as well as KenGen.

Questionnaires were delivered to targeted participants and follow-ups were made through e-mails and

telephone calls. Of the 54 targeted participants, 39 (72%) successfully completed and returned the

questionnaires. Table 2 shows the questionnaire return rate for each category of participants.

Table 2

Questionnaire Return Rate

Contracting partner type No. targeted No. of participants Return rate (%)

Employer 15 14 93.3

Contractor 20 12 60.0

Engineer 15 10 66.7

Financier 4 3 75.0

Total 54 39 72.2

Primary data were listed, coded, digitalized, and cleaned for logical inconsistencies and misplaced codes.

The methods used included descriptive, factorial comparative, and rank analyses, to develop relative

importance of causes and effects of contractual delay on the project’s completion. Relative importance index

(RII) was computed using the formula (Kometa, Oloimolaiye, & Harris, 1994).

RII (1)

and JICA (the financier). Senior management staff members were targeted, because contractual issues form part

of their responsibility. A sampling frame of all senior management staff was prepared using organizational

management charts of each contracting party and the process identified 54 eligible participants, who were all

included in the sample to avoid the risk of sampling error (Table 1).

Table 1

Sampling Frame

Contracting partner type Frequency Percent

Employer 15 27.8

Contractor 20 37.0

Engineer 15 27.8

Financier 4 7.4

Total 54 100.0

Self-administered questionnaires were used to source the information, particularly because they provided

the flexibility that targeted participants would require, considering their complicated itineraries. The approach

enabled participants to provide the requisite data at their convenience. One module of the instrument was

applied across the board to permit comparison of perspectives from different contracting parties. The

instrument, which had both closed- and open-ended questions, captured information on contractual delay

typology, perceived causes and effects, as well as mitigative measures.

The instrument was pre-tested at the Kisumu Airport Expansion Project, which had a similar contractual

management structure. The pre-testing was important for testing reliability of the instrument, validity, and

feasibility of data collection approaches. Primary data were collected in May 2011 after obtaining necessary

approval from University of Nairobi, National Council of Science and Technology, as well as KenGen.

Questionnaires were delivered to targeted participants and follow-ups were made through e-mails and

telephone calls. Of the 54 targeted participants, 39 (72%) successfully completed and returned the

questionnaires. Table 2 shows the questionnaire return rate for each category of participants.

Table 2

Questionnaire Return Rate

Contracting partner type No. targeted No. of participants Return rate (%)

Employer 15 14 93.3

Contractor 20 12 60.0

Engineer 15 10 66.7

Financier 4 3 75.0

Total 54 39 72.2

Primary data were listed, coded, digitalized, and cleaned for logical inconsistencies and misplaced codes.

The methods used included descriptive, factorial comparative, and rank analyses, to develop relative

importance of causes and effects of contractual delay on the project’s completion. Relative importance index

(RII) was computed using the formula (Kometa, Oloimolaiye, & Harris, 1994).

RII (1)

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

A CASE OF SONDU-MIRIU HYDROPOWER PROJECT, KISUMU COUNTY, KENYA330

where W is the weighting assigned to each response on a scale of 1 to 5 corresponding with lowest to highest; A

is the highest weight; and N is the total number of participants.

RII yielded values in the range of 0 < x ≥ 1. The higher the value of RII is, the more important the

identified factor on contractual delays is. This ranking enabled cross comparison of the relative importance of

the factors as perceived by the four categories of participants. RII is a non-probabilistic rank statistic derived

from ordinal data; hence, its accuracy is non-dependent on sample size or the population.

Furthermore, Kendell’s coefficient of concordance was applied to determine the degree of agreement

among the four categories of participants with respect to their ranking (Frimpong et al., 2003). The coefficient

states that the degree of agreement on a 0 to 1 scale is given by W, such that:

(2)

where,

Σ … Σ (3)

where n is the number of factors; m is the number of groups; and j represent the factors 1, 2, 3, … n.

As noted by Frimpong et al. (2003), Kendell’s coefficient of concordance is strong on both probabilistic

and non-probabilistic distributions, because it is not sensitive to sampling error. In addition, Chi-square statistic

was used to determine whether there was a significant difference in the ranking of contractual delay factors

perceived to be influencing delays in the project’s completion. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS) and Microsoft Excel were used to analyze the data.

Results

The results of this study were organized, interpreted, and discussed under five thematic areas, including

participants’ profile, forms of contractual delay, components of contractual delay, and effects of delayed

payment of the contractor on the project’s completion. Details are presented and discussed under the following

sub-sections.

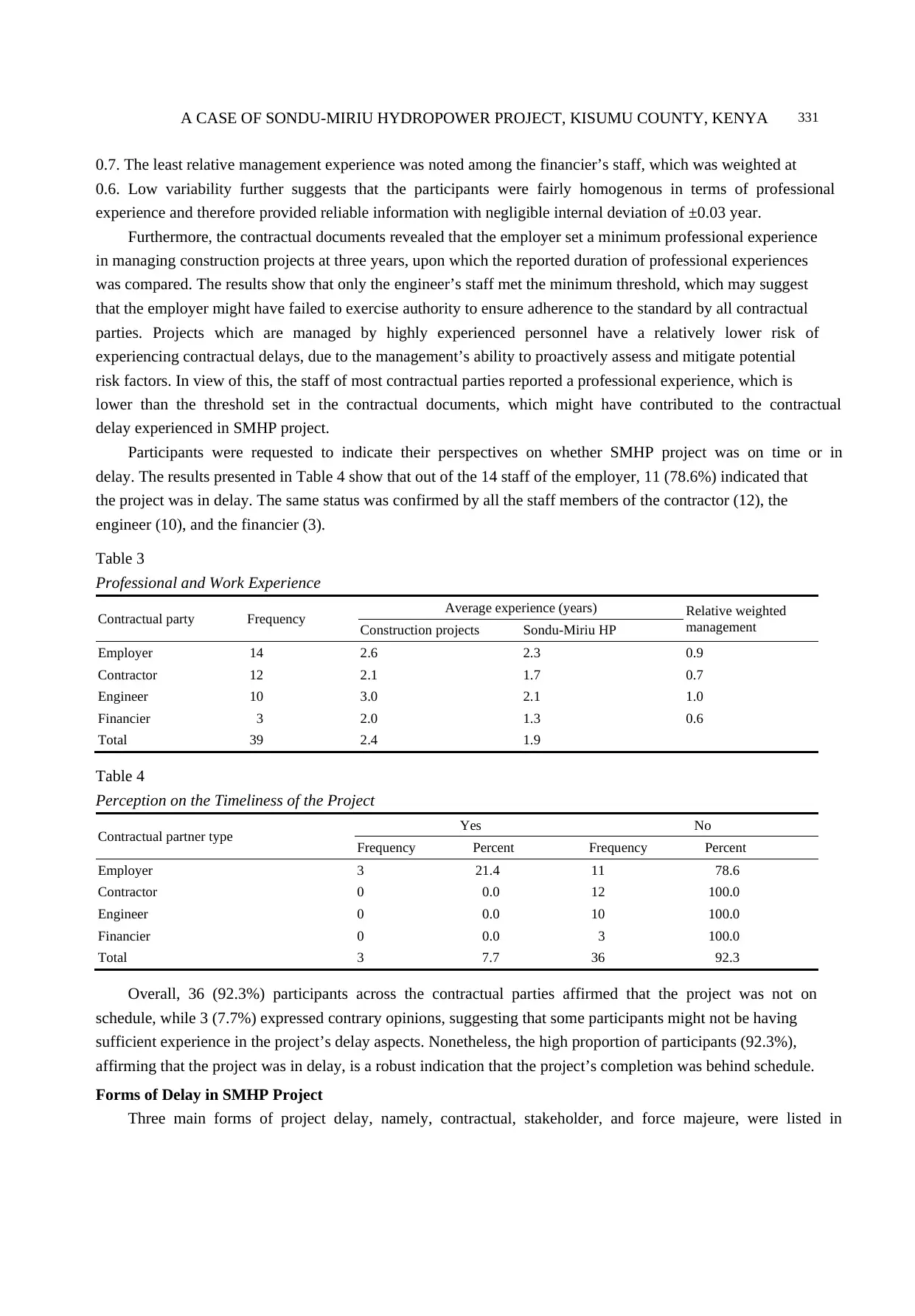

Participants’ Professional and Work Experience

The study covered 39 senior management staff of the contractual parties, including 14 (35.9%) from

KenGen, 12 (30.8%) from Sinohydro, 10 (25.6%) from Nippon Koei, and 3 (7.7%) from JICA. The duration of

professional and work experience is an important factor in successful management and administration of

construction projects. In view of this, participants were requested to indicate the duration of experience in

managing construction projects and more specifically, the duration of experience in managing SMHP project.

The results are summarized in Table 3.

The results show that the employer’s staff reported an average professional experience of 2.6 years in the

management of construction projects and 2.3 years in the management of SMHP project. The contractor’s staff

indicated an averaged experience of 2.1 years and 1.7 years in the management of construction projects and

SMHP project, respectively. Engineer’s staff reported an average experience of 3.0 and 2.1 years; while the

Financier’s staff stated the least experience of 2 years in the management of construction projects and 1.3 years

in SMHP project.

The results suggest low variability of experience among participants. The average experience was 2.4

years in management of construction projects and 1.9 years in management of the project. The engineer’s staffs

were the most experienced with a relative weight of 1.0 compared to the employer’s 0.9 and the contractor’s

where W is the weighting assigned to each response on a scale of 1 to 5 corresponding with lowest to highest; A

is the highest weight; and N is the total number of participants.

RII yielded values in the range of 0 < x ≥ 1. The higher the value of RII is, the more important the

identified factor on contractual delays is. This ranking enabled cross comparison of the relative importance of

the factors as perceived by the four categories of participants. RII is a non-probabilistic rank statistic derived

from ordinal data; hence, its accuracy is non-dependent on sample size or the population.

Furthermore, Kendell’s coefficient of concordance was applied to determine the degree of agreement

among the four categories of participants with respect to their ranking (Frimpong et al., 2003). The coefficient

states that the degree of agreement on a 0 to 1 scale is given by W, such that:

(2)

where,

Σ … Σ (3)

where n is the number of factors; m is the number of groups; and j represent the factors 1, 2, 3, … n.

As noted by Frimpong et al. (2003), Kendell’s coefficient of concordance is strong on both probabilistic

and non-probabilistic distributions, because it is not sensitive to sampling error. In addition, Chi-square statistic

was used to determine whether there was a significant difference in the ranking of contractual delay factors

perceived to be influencing delays in the project’s completion. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS) and Microsoft Excel were used to analyze the data.

Results

The results of this study were organized, interpreted, and discussed under five thematic areas, including

participants’ profile, forms of contractual delay, components of contractual delay, and effects of delayed

payment of the contractor on the project’s completion. Details are presented and discussed under the following

sub-sections.

Participants’ Professional and Work Experience

The study covered 39 senior management staff of the contractual parties, including 14 (35.9%) from

KenGen, 12 (30.8%) from Sinohydro, 10 (25.6%) from Nippon Koei, and 3 (7.7%) from JICA. The duration of

professional and work experience is an important factor in successful management and administration of

construction projects. In view of this, participants were requested to indicate the duration of experience in

managing construction projects and more specifically, the duration of experience in managing SMHP project.

The results are summarized in Table 3.

The results show that the employer’s staff reported an average professional experience of 2.6 years in the

management of construction projects and 2.3 years in the management of SMHP project. The contractor’s staff

indicated an averaged experience of 2.1 years and 1.7 years in the management of construction projects and

SMHP project, respectively. Engineer’s staff reported an average experience of 3.0 and 2.1 years; while the

Financier’s staff stated the least experience of 2 years in the management of construction projects and 1.3 years

in SMHP project.

The results suggest low variability of experience among participants. The average experience was 2.4

years in management of construction projects and 1.9 years in management of the project. The engineer’s staffs

were the most experienced with a relative weight of 1.0 compared to the employer’s 0.9 and the contractor’s

A CASE OF SONDU-MIRIU HYDROPOWER PROJECT, KISUMU COUNTY, KENYA 331

0.7. The least relative management experience was noted among the financier’s staff, which was weighted at

0.6. Low variability further suggests that the participants were fairly homogenous in terms of professional

experience and therefore provided reliable information with negligible internal deviation of ±0.03 year.

Furthermore, the contractual documents revealed that the employer set a minimum professional experience

in managing construction projects at three years, upon which the reported duration of professional experiences

was compared. The results show that only the engineer’s staff met the minimum threshold, which may suggest

that the employer might have failed to exercise authority to ensure adherence to the standard by all contractual

parties. Projects which are managed by highly experienced personnel have a relatively lower risk of

experiencing contractual delays, due to the management’s ability to proactively assess and mitigate potential

risk factors. In view of this, the staff of most contractual parties reported a professional experience, which is

lower than the threshold set in the contractual documents, which might have contributed to the contractual

delay experienced in SMHP project.

Participants were requested to indicate their perspectives on whether SMHP project was on time or in

delay. The results presented in Table 4 show that out of the 14 staff of the employer, 11 (78.6%) indicated that

the project was in delay. The same status was confirmed by all the staff members of the contractor (12), the

engineer (10), and the financier (3).

Table 3

Professional and Work Experience

Contractual party Frequency Average experience (years) Relative weighted

managementConstruction projects Sondu-Miriu HP

Employer 14 2.6 2.3 0.9

Contractor 12 2.1 1.7 0.7

Engineer 10 3.0 2.1 1.0

Financier 3 2.0 1.3 0.6

Total 39 2.4 1.9

Table 4

Perception on the Timeliness of the Project

Contractual partner type Yes No

Frequency Percent Frequency Percent

Employer 3 21.4 11 78.6

Contractor 0 0.0 12 100.0

Engineer 0 0.0 10 100.0

Financier 0 0.0 3 100.0

Total 3 7.7 36 92.3

Overall, 36 (92.3%) participants across the contractual parties affirmed that the project was not on

schedule, while 3 (7.7%) expressed contrary opinions, suggesting that some participants might not be having

sufficient experience in the project’s delay aspects. Nonetheless, the high proportion of participants (92.3%),

affirming that the project was in delay, is a robust indication that the project’s completion was behind schedule.

Forms of Delay in SMHP Project

Three main forms of project delay, namely, contractual, stakeholder, and force majeure, were listed in

0.7. The least relative management experience was noted among the financier’s staff, which was weighted at

0.6. Low variability further suggests that the participants were fairly homogenous in terms of professional

experience and therefore provided reliable information with negligible internal deviation of ±0.03 year.

Furthermore, the contractual documents revealed that the employer set a minimum professional experience

in managing construction projects at three years, upon which the reported duration of professional experiences

was compared. The results show that only the engineer’s staff met the minimum threshold, which may suggest

that the employer might have failed to exercise authority to ensure adherence to the standard by all contractual

parties. Projects which are managed by highly experienced personnel have a relatively lower risk of

experiencing contractual delays, due to the management’s ability to proactively assess and mitigate potential

risk factors. In view of this, the staff of most contractual parties reported a professional experience, which is

lower than the threshold set in the contractual documents, which might have contributed to the contractual

delay experienced in SMHP project.

Participants were requested to indicate their perspectives on whether SMHP project was on time or in

delay. The results presented in Table 4 show that out of the 14 staff of the employer, 11 (78.6%) indicated that

the project was in delay. The same status was confirmed by all the staff members of the contractor (12), the

engineer (10), and the financier (3).

Table 3

Professional and Work Experience

Contractual party Frequency Average experience (years) Relative weighted

managementConstruction projects Sondu-Miriu HP

Employer 14 2.6 2.3 0.9

Contractor 12 2.1 1.7 0.7

Engineer 10 3.0 2.1 1.0

Financier 3 2.0 1.3 0.6

Total 39 2.4 1.9

Table 4

Perception on the Timeliness of the Project

Contractual partner type Yes No

Frequency Percent Frequency Percent

Employer 3 21.4 11 78.6

Contractor 0 0.0 12 100.0

Engineer 0 0.0 10 100.0

Financier 0 0.0 3 100.0

Total 3 7.7 36 92.3

Overall, 36 (92.3%) participants across the contractual parties affirmed that the project was not on

schedule, while 3 (7.7%) expressed contrary opinions, suggesting that some participants might not be having

sufficient experience in the project’s delay aspects. Nonetheless, the high proportion of participants (92.3%),

affirming that the project was in delay, is a robust indication that the project’s completion was behind schedule.

Forms of Delay in SMHP Project

Three main forms of project delay, namely, contractual, stakeholder, and force majeure, were listed in

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 48

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.