Review of Crises and Crisis Management: Integration & Research Dev

VerifiedAdded on 2023/04/21

|51

|34271

|453

Literature Review

AI Summary

This literature review integrates research on crises and crisis management from various disciplines, including strategic management, organizational theory, organizational behavior, public relations, and corporate communication. It proposes a framework incorporating two dominant perspectives: an internal perspective focused on the technical and structural aspects of a crisis and an external perspective focused on managing stakeholder relationships. The review identifies opportunities for integration between these perspectives across three stages: precrisis prevention, crisis management, and postcrisis outcomes. It highlights research on organizational preparedness, stakeholder relationships, crisis leadership, stakeholder perceptions, organizational learning, and social evaluations, providing a foundation for future cross-disciplinary research and practical application. The study also addresses the fragmented nature of crisis management research, aiming to foster a more cohesive understanding of the field.

Journal of Management

Vol. XX No. X, Month XXXX 1 –32

DOI: 10.1177/0149206316680030

© The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Crises and Crisis Management: Integration,

Interpretation, and Research Development

Jonathan Bundy

Arizona State University

Michael D. Pfarrer

Cole E. Short

University of Georgia

W. Timothy Coombs

Texas A&M University

Organizational research has long been interested in crises and crisis management. Whether

focused on crisis antecedents, outcomes, or managing a crisis, research has revealed a number

of important findings. However, research in this space remains fragmented, making it difficult

for scholars to understand the literature’s core conclusions, recognize unsolved problems, and

navigate paths forward. To address these issues, we propose an integrative framework of crises

and crisis management that draws from research in strategy, organizational theory, and orga-

nizational behavior as well as from research in public relations and corporate communication.

We identify two primary perspectives in the literature, one focused on the internal dynamics of

a crisis and one focused on managing external stakeholders. We review core concepts from each

perspective and highlight the commonalities that exist between them. Finally, we use our inte-

grative framework to propose future research directions for scholars interested in crises and

crisis management.

Keywords: crisis; crises; crisis management; organizational wrongdoing; perception and

impression management

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Miles Zachary for comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. We

are also grateful to associate editor Karen Schnatterly and two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback

and guidance.

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Corresponding author: Jonathan Bundy, Arizona State University, P.O. Box 874006, Tempe, AZ 85287-4006,

USA.

680030 JOMXXX10.1177/0149206316680030Journal of Management Bundy et al. / Review of Crises and Crisis Management

research-article2016

Vol. XX No. X, Month XXXX 1 –32

DOI: 10.1177/0149206316680030

© The Author(s) 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Crises and Crisis Management: Integration,

Interpretation, and Research Development

Jonathan Bundy

Arizona State University

Michael D. Pfarrer

Cole E. Short

University of Georgia

W. Timothy Coombs

Texas A&M University

Organizational research has long been interested in crises and crisis management. Whether

focused on crisis antecedents, outcomes, or managing a crisis, research has revealed a number

of important findings. However, research in this space remains fragmented, making it difficult

for scholars to understand the literature’s core conclusions, recognize unsolved problems, and

navigate paths forward. To address these issues, we propose an integrative framework of crises

and crisis management that draws from research in strategy, organizational theory, and orga-

nizational behavior as well as from research in public relations and corporate communication.

We identify two primary perspectives in the literature, one focused on the internal dynamics of

a crisis and one focused on managing external stakeholders. We review core concepts from each

perspective and highlight the commonalities that exist between them. Finally, we use our inte-

grative framework to propose future research directions for scholars interested in crises and

crisis management.

Keywords: crisis; crises; crisis management; organizational wrongdoing; perception and

impression management

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Miles Zachary for comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. We

are also grateful to associate editor Karen Schnatterly and two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback

and guidance.

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Corresponding author: Jonathan Bundy, Arizona State University, P.O. Box 874006, Tempe, AZ 85287-4006,

USA.

680030 JOMXXX10.1177/0149206316680030Journal of Management Bundy et al. / Review of Crises and Crisis Management

research-article2016

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

An organizational crisis—an event perceived by managers and stakeholders as highly

salient, unexpected, and potentially disruptive—can threaten an organization’s goals and

have profound implications for its relationships with stakeholders. For example, BP’s Gulf

oil spill harmed its financial performance and reputation, and it redefined its relationship

with customers, employees, local communities, and governments. Similarly, Target’s con-

sumer data breach caused financial and reputational damage to the company, and the crisis

spurred large-scale changes in the way electronic records are now processed and stored.

Because of these implications, organizational research from a variety of disciplines has

devoted considerable attention to crises and crisis management, working to understand how

and why crises occur (Coombs & Holladay, 2002; Perrow, 1984; Weick, 1993), and how

organizations can manage them to reduce harm (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015; Coombs, 2007;

Kahn, Barton, & Fellows, 2013). Organizational research has also considered a number of

important crisis outcomes, including stakeholders’ perceptions of organizational reputation,

trust, and legitimacy (Coombs, 2007; Elsbach, 1994; Gillespie & Dietz, 2009; Pfarrer,

DeCelles, Smith, & Taylor, 2008), organizational learning and adaptation (Lampel, Shamsie,

& Shapira, 2009; Veil, 2011), and financial performance and survival (D’Aveni & MacMillan,

1990; Marcus & Goodman, 1991).

However, despite sustained interest across multiple disciplines, recent commentary on the

field suggests that “we have only just begun to scratch the surface in our understanding” of

crises and crisis management, and encourages further consideration of the theoretical mecha-

nisms at work (Coombs, 2010: 479; Pearson, Roux-Dufort, & Clair, 2007). Additionally,

research in this area has been criticized for its lack of theoretical and empirical rigor, given

that many of its conclusions and prescriptions are derived from case studies or anecdotal

evidence (Coombs, 2007; Sellnow & Seeger, 2013). Finally, many scholars continue to

lament a silo effect, noting that researchers from different perspectives often talk past one

another without capitalizing on opportunities to build cross-disciplinary scholarship (James,

Wooten, & Dushek, 2011; Jaques, 2009; Kahn et al., 2013). As such, there is little consensus

and integration across fields of study, numerous and sometimes conflicting prescriptions

abound, and debates continue regarding the relevant antecedents, processes, and outcomes

associated with crises and crisis management.

The purpose of this article is twofold: First, we review and integrate the literature on crises

and crisis management from multiple disciplines, including strategic management, organiza-

tion theory, and organizational behavior as well as public relations and corporate communi-

cation. Second, we contribute to scholarship by specifying a framework that incorporates two

dominant perspectives found in the literature. The first perspective is internally oriented

toward the technical and structural aspects of a crisis, while the second perspective is exter-

nally oriented toward managing stakeholder relationships. Our review reveals that these per-

spectives have developed largely independently, and we identify numerous opportunities for

integration. Ultimately, our framework serves as a foundation for future cross-disciplinary

research as well an effective tool for practitioners.

Method and Review Framework

To conduct our review, we performed an extensive and integrative search of articles pub-

lished in major organizational academic journals, with certain boundary conditions to make

An organizational crisis—an event perceived by managers and stakeholders as highly

salient, unexpected, and potentially disruptive—can threaten an organization’s goals and

have profound implications for its relationships with stakeholders. For example, BP’s Gulf

oil spill harmed its financial performance and reputation, and it redefined its relationship

with customers, employees, local communities, and governments. Similarly, Target’s con-

sumer data breach caused financial and reputational damage to the company, and the crisis

spurred large-scale changes in the way electronic records are now processed and stored.

Because of these implications, organizational research from a variety of disciplines has

devoted considerable attention to crises and crisis management, working to understand how

and why crises occur (Coombs & Holladay, 2002; Perrow, 1984; Weick, 1993), and how

organizations can manage them to reduce harm (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015; Coombs, 2007;

Kahn, Barton, & Fellows, 2013). Organizational research has also considered a number of

important crisis outcomes, including stakeholders’ perceptions of organizational reputation,

trust, and legitimacy (Coombs, 2007; Elsbach, 1994; Gillespie & Dietz, 2009; Pfarrer,

DeCelles, Smith, & Taylor, 2008), organizational learning and adaptation (Lampel, Shamsie,

& Shapira, 2009; Veil, 2011), and financial performance and survival (D’Aveni & MacMillan,

1990; Marcus & Goodman, 1991).

However, despite sustained interest across multiple disciplines, recent commentary on the

field suggests that “we have only just begun to scratch the surface in our understanding” of

crises and crisis management, and encourages further consideration of the theoretical mecha-

nisms at work (Coombs, 2010: 479; Pearson, Roux-Dufort, & Clair, 2007). Additionally,

research in this area has been criticized for its lack of theoretical and empirical rigor, given

that many of its conclusions and prescriptions are derived from case studies or anecdotal

evidence (Coombs, 2007; Sellnow & Seeger, 2013). Finally, many scholars continue to

lament a silo effect, noting that researchers from different perspectives often talk past one

another without capitalizing on opportunities to build cross-disciplinary scholarship (James,

Wooten, & Dushek, 2011; Jaques, 2009; Kahn et al., 2013). As such, there is little consensus

and integration across fields of study, numerous and sometimes conflicting prescriptions

abound, and debates continue regarding the relevant antecedents, processes, and outcomes

associated with crises and crisis management.

The purpose of this article is twofold: First, we review and integrate the literature on crises

and crisis management from multiple disciplines, including strategic management, organiza-

tion theory, and organizational behavior as well as public relations and corporate communi-

cation. Second, we contribute to scholarship by specifying a framework that incorporates two

dominant perspectives found in the literature. The first perspective is internally oriented

toward the technical and structural aspects of a crisis, while the second perspective is exter-

nally oriented toward managing stakeholder relationships. Our review reveals that these per-

spectives have developed largely independently, and we identify numerous opportunities for

integration. Ultimately, our framework serves as a foundation for future cross-disciplinary

research as well an effective tool for practitioners.

Method and Review Framework

To conduct our review, we performed an extensive and integrative search of articles pub-

lished in major organizational academic journals, with certain boundary conditions to make

Bundy et al. / Review of Crises and Crisis Management 3

the review pertinent to management and organizational scholars. Pearson and Clair’s (1998)

Academy of Management Review article has been a foundation of subsequent developments

in the literature; therefore, we used their article as our starting point. We cover the time

period from 1998 to 2015 with a few exceptions, primarily to reference seminal research.

Following the recommendations of Short (2009), we primarily focused our review on the

following journals: Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review,

Administrative Science Quarterly, Journal of Management, Journal of Management Studies,

Organization Science, and Strategic Management Journal. To identify relevant articles from

these outlets, we conducted full-text searches on the terms crisis, crises, and crisis manage-

ment. We then identified and categorized critical themes to generate a set of articles for inclu-

sion. This involved removing articles that did not primarily focus on crises or crisis

management in their research questions, hypotheses, or propositions. We also extended our

methodology by searching the references of the articles identified in our initial search as well

as searching for research that cites these articles (cf. Johnson, Schnatterly, & Hill, 2013;

Short, 2009). This led us to include a number of influential books, relevant articles in other

respected journals, and research from public relations and communication. Overall, we

sought to collect the work that is most relevant to management and organizational scholars.

Despite a diversity of perspectives and intellectual traditions, our analysis of the multiple

definitions of crises and crisis management over the past 20 years reveals convergence (see

Heath, 2012; James et al., 2011; Jaques, 2009; Pearson & Clair, 1998; and Sellnow & Seeger,

2013, for detailed definitional reviews). Drawing from this convergence, we define an orga-

nizational crisis as an event perceived by managers and stakeholders to be highly salient,

unexpected, and potentially disruptive. We also recognize that crises have four primary char-

acteristics: (a) crises are sources of uncertainty, disruption, and change (cf. Bundy & Pfarrer,

2015; James et al., 2011; Kahn et al., 2013); (b) crises are harmful or threatening for organi-

zations and their stakeholders, many of whom may have conflicting needs and demands (cf.

Fediuk, Coombs, & Botero, 2012; James et al., 2011; Kahn et al., 2013); (c) crises are behav-

ioral phenomena, meaning that the literature has recognized that crises are socially con-

structed by the actors involved rather than a function of the depersonalized factors of an

objective environment (cf. Coombs, 2010: 478; Gephart, 2007; Lampel et al., 2009); and (d)

crises are parts of larger processes, rather than discrete events (cf. Jaques, 2009; Pearson &

Clair, 1998; Roux-Dufort, 2007). Additionally, we recognize that crisis management broadly

captures organizational leaders’ actions and communication that attempt to reduce the likeli-

hood of a crisis, work to minimize harm from a crisis, and endeavor to reestablish order fol-

lowing a crisis (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015; Kahn et al., 2013; Pearson & Clair, 1998).

Definitional convergence aside, a number of scholars prior to and throughout our review

period have noted a lack of integration across disciplines and perspectives (cf. Jaques, 2009).

For example, Shrivastava (1993: 33) highlighted a “Tower of Babel” effect, arguing that

there are “many disciplinary voices, talking in so many different languages to different issues

and audiences” that it becomes difficult to build cross-disciplinary theory and policy guide-

lines. More recently, Pearson and colleagues (2007: viii) worried that the “virtual galaxy of

critical concepts” resulting from this lack of coordination not only may impede on the ability

to build theory and aid practice but also risks the “legitimacy and credibility” of the field as

a whole. James and colleagues (2011: 457) echoed this concern in their review of crisis lead-

ership, noting that “fragmentation has prevented a widely accepted understanding of, or com-

the review pertinent to management and organizational scholars. Pearson and Clair’s (1998)

Academy of Management Review article has been a foundation of subsequent developments

in the literature; therefore, we used their article as our starting point. We cover the time

period from 1998 to 2015 with a few exceptions, primarily to reference seminal research.

Following the recommendations of Short (2009), we primarily focused our review on the

following journals: Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review,

Administrative Science Quarterly, Journal of Management, Journal of Management Studies,

Organization Science, and Strategic Management Journal. To identify relevant articles from

these outlets, we conducted full-text searches on the terms crisis, crises, and crisis manage-

ment. We then identified and categorized critical themes to generate a set of articles for inclu-

sion. This involved removing articles that did not primarily focus on crises or crisis

management in their research questions, hypotheses, or propositions. We also extended our

methodology by searching the references of the articles identified in our initial search as well

as searching for research that cites these articles (cf. Johnson, Schnatterly, & Hill, 2013;

Short, 2009). This led us to include a number of influential books, relevant articles in other

respected journals, and research from public relations and communication. Overall, we

sought to collect the work that is most relevant to management and organizational scholars.

Despite a diversity of perspectives and intellectual traditions, our analysis of the multiple

definitions of crises and crisis management over the past 20 years reveals convergence (see

Heath, 2012; James et al., 2011; Jaques, 2009; Pearson & Clair, 1998; and Sellnow & Seeger,

2013, for detailed definitional reviews). Drawing from this convergence, we define an orga-

nizational crisis as an event perceived by managers and stakeholders to be highly salient,

unexpected, and potentially disruptive. We also recognize that crises have four primary char-

acteristics: (a) crises are sources of uncertainty, disruption, and change (cf. Bundy & Pfarrer,

2015; James et al., 2011; Kahn et al., 2013); (b) crises are harmful or threatening for organi-

zations and their stakeholders, many of whom may have conflicting needs and demands (cf.

Fediuk, Coombs, & Botero, 2012; James et al., 2011; Kahn et al., 2013); (c) crises are behav-

ioral phenomena, meaning that the literature has recognized that crises are socially con-

structed by the actors involved rather than a function of the depersonalized factors of an

objective environment (cf. Coombs, 2010: 478; Gephart, 2007; Lampel et al., 2009); and (d)

crises are parts of larger processes, rather than discrete events (cf. Jaques, 2009; Pearson &

Clair, 1998; Roux-Dufort, 2007). Additionally, we recognize that crisis management broadly

captures organizational leaders’ actions and communication that attempt to reduce the likeli-

hood of a crisis, work to minimize harm from a crisis, and endeavor to reestablish order fol-

lowing a crisis (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015; Kahn et al., 2013; Pearson & Clair, 1998).

Definitional convergence aside, a number of scholars prior to and throughout our review

period have noted a lack of integration across disciplines and perspectives (cf. Jaques, 2009).

For example, Shrivastava (1993: 33) highlighted a “Tower of Babel” effect, arguing that

there are “many disciplinary voices, talking in so many different languages to different issues

and audiences” that it becomes difficult to build cross-disciplinary theory and policy guide-

lines. More recently, Pearson and colleagues (2007: viii) worried that the “virtual galaxy of

critical concepts” resulting from this lack of coordination not only may impede on the ability

to build theory and aid practice but also risks the “legitimacy and credibility” of the field as

a whole. James and colleagues (2011: 457) echoed this concern in their review of crisis lead-

ership, noting that “fragmentation has prevented a widely accepted understanding of, or com-

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

From our review of the literature, we have identified two primary perspectives that focus

on different aspects of crises and crisis management and that draw from different theoretical

traditions to answer distinct research questions. The first perspective, which we label the

internal perspective, focuses on the within-organization dynamics of managing risk, com-

plexity, and technology (e.g., Bigley & Roberts, 2001; Gephart, Van Maanen, & Oberlechner,

2009; Pearson & Clair, 1998; Perrow, 1984; Starbuck & Milliken, 1988). For these scholars,

crisis management involves the coordination of complex technical and relational systems

and the design of organizational structures to prevent the occurrence, reduce the impact, and

learn from a crisis. In contrast, the second perspective, which we label the external perspec-

tive, focuses on the interactions of organizations and external stakeholders, largely drawing

from theories of social perception and impression management (e.g., Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015;

Coombs, 2007; Elsbach, 1994; Pfarrer, DeCelles, et al., 2008). According to this perspective,

crisis management involves shaping perceptions and coordinating with stakeholders to pre-

vent, solve, and grow from a crisis.

While sharing a number of core assumptions and commonalities that we detail below, the

internal and external perspectives have largely evolved independently. Therefore, we frame

our review around these two dominant perspectives and highlight a number of opportunities

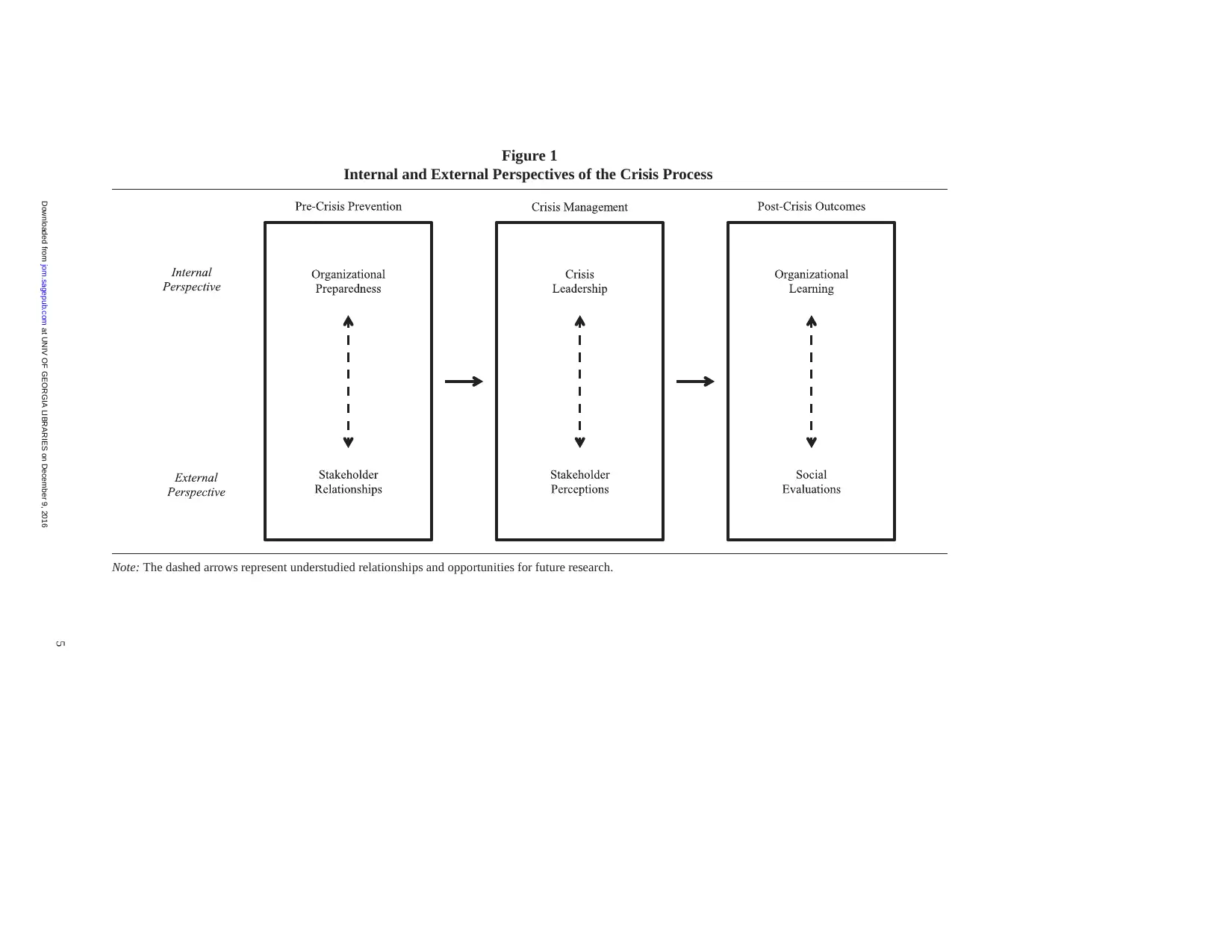

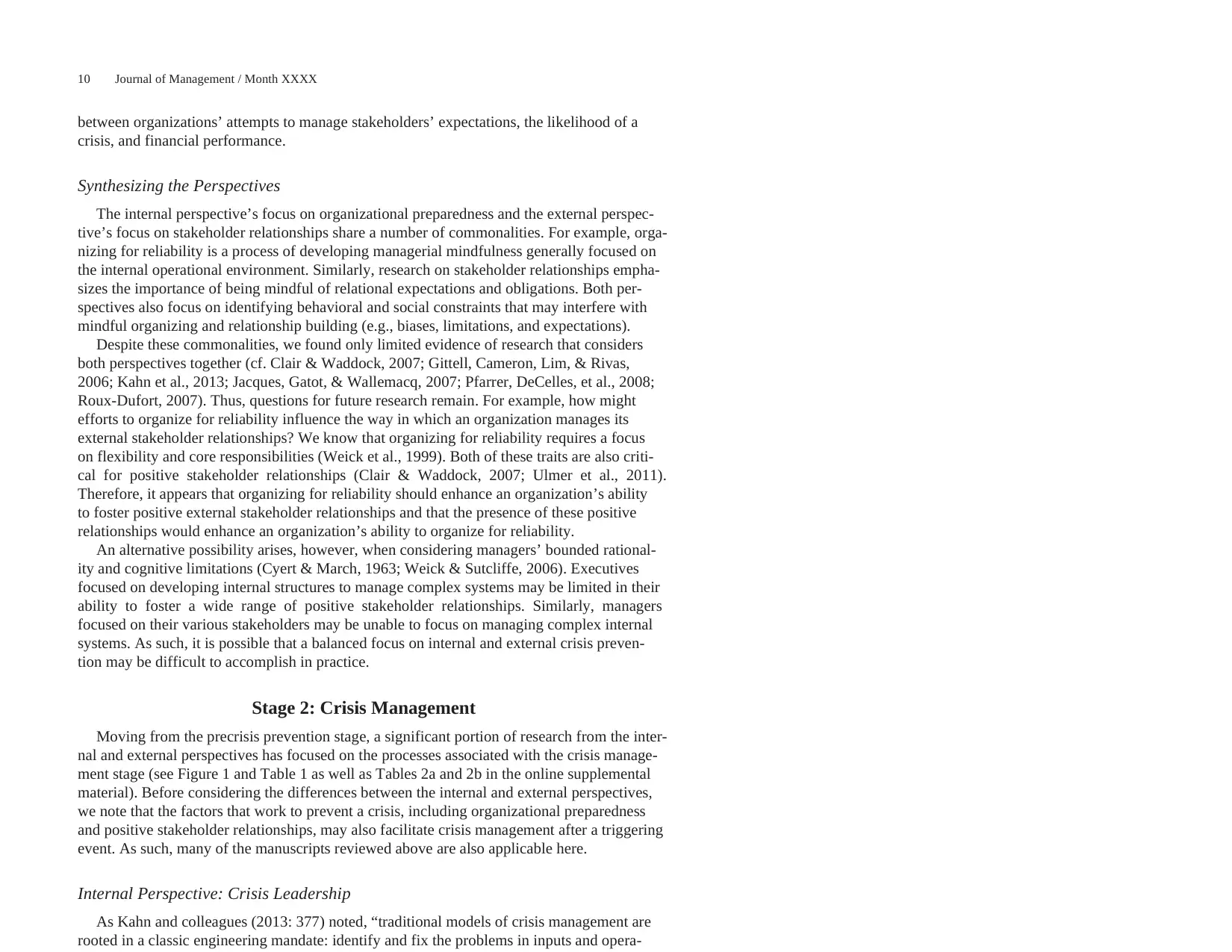

for integration. We present our framework in Figure 1, which categorizes the literature into

internal and external perspectives and is situated around three primary stages of a crisis: pre-

crisis prevention, crisis management, and postcrisis outcomes. The articles featured in our

review are outlined in Table 1, and more detailed tables are available in the online appendix.

We detail our model below while synthesizing commonalities among the perspectives and

offering directions for future research. First, we review the literature that has considered how

organizations can reduce the likelihood of a crisis, which we label the precrisis prevention

stage. In particular, we highlight research on organizational preparedness from the internal

perspective and research on stakeholder relationships from the external perspective. This

research is also summarized online in Tables 1a and 1b.

Second, we focus on the crisis management stage, which considers the actions taken by

managers in the immediate aftermath of a crisis. 1 From our literature review, we recognize

that the internal perspective focuses on crisis leadership, while the external perspective

focuses on stakeholder perceptions of the crisis. This research is also summarized online in

Tables 2a and 2b.

The final component of our model focuses on the postcrisis outcomes stage. The literature

from the internal perspective has highlighted the role of organizational learning following a

crisis, while the literature from the external perspective focuses on social evaluations as out-

comes (e.g., assessments of reputation, legitimacy, and trust). Although not pictured in Figure

1, we also note that both perspectives consider other tangible organizational outcomes, such

as turnover and performance. This research is also summarized online in Tables 3a and 3b.

Stage 1: Precrisis Prevention

Internal Perspective: Organizational Preparedness

Precrisis prevention research from the internal perspective generally draws from the work

of Perrow (1984) and others to highlight the inevitability of crises due to the complexity of

From our review of the literature, we have identified two primary perspectives that focus

on different aspects of crises and crisis management and that draw from different theoretical

traditions to answer distinct research questions. The first perspective, which we label the

internal perspective, focuses on the within-organization dynamics of managing risk, com-

plexity, and technology (e.g., Bigley & Roberts, 2001; Gephart, Van Maanen, & Oberlechner,

2009; Pearson & Clair, 1998; Perrow, 1984; Starbuck & Milliken, 1988). For these scholars,

crisis management involves the coordination of complex technical and relational systems

and the design of organizational structures to prevent the occurrence, reduce the impact, and

learn from a crisis. In contrast, the second perspective, which we label the external perspec-

tive, focuses on the interactions of organizations and external stakeholders, largely drawing

from theories of social perception and impression management (e.g., Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015;

Coombs, 2007; Elsbach, 1994; Pfarrer, DeCelles, et al., 2008). According to this perspective,

crisis management involves shaping perceptions and coordinating with stakeholders to pre-

vent, solve, and grow from a crisis.

While sharing a number of core assumptions and commonalities that we detail below, the

internal and external perspectives have largely evolved independently. Therefore, we frame

our review around these two dominant perspectives and highlight a number of opportunities

for integration. We present our framework in Figure 1, which categorizes the literature into

internal and external perspectives and is situated around three primary stages of a crisis: pre-

crisis prevention, crisis management, and postcrisis outcomes. The articles featured in our

review are outlined in Table 1, and more detailed tables are available in the online appendix.

We detail our model below while synthesizing commonalities among the perspectives and

offering directions for future research. First, we review the literature that has considered how

organizations can reduce the likelihood of a crisis, which we label the precrisis prevention

stage. In particular, we highlight research on organizational preparedness from the internal

perspective and research on stakeholder relationships from the external perspective. This

research is also summarized online in Tables 1a and 1b.

Second, we focus on the crisis management stage, which considers the actions taken by

managers in the immediate aftermath of a crisis. 1 From our literature review, we recognize

that the internal perspective focuses on crisis leadership, while the external perspective

focuses on stakeholder perceptions of the crisis. This research is also summarized online in

Tables 2a and 2b.

The final component of our model focuses on the postcrisis outcomes stage. The literature

from the internal perspective has highlighted the role of organizational learning following a

crisis, while the literature from the external perspective focuses on social evaluations as out-

comes (e.g., assessments of reputation, legitimacy, and trust). Although not pictured in Figure

1, we also note that both perspectives consider other tangible organizational outcomes, such

as turnover and performance. This research is also summarized online in Tables 3a and 3b.

Stage 1: Precrisis Prevention

Internal Perspective: Organizational Preparedness

Precrisis prevention research from the internal perspective generally draws from the work

of Perrow (1984) and others to highlight the inevitability of crises due to the complexity of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

Figure 1

Internal and External Perspectives of the Crisis Process

Note: The dashed arrows represent understudied relationships and opportunities for future research.

at UNIV OF GEORGIA LIBRARIES on December 9, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Figure 1

Internal and External Perspectives of the Crisis Process

Note: The dashed arrows represent understudied relationships and opportunities for future research.

at UNIV OF GEORGIA LIBRARIES on December 9, 2016jom.sagepub.comDownloaded from

6 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

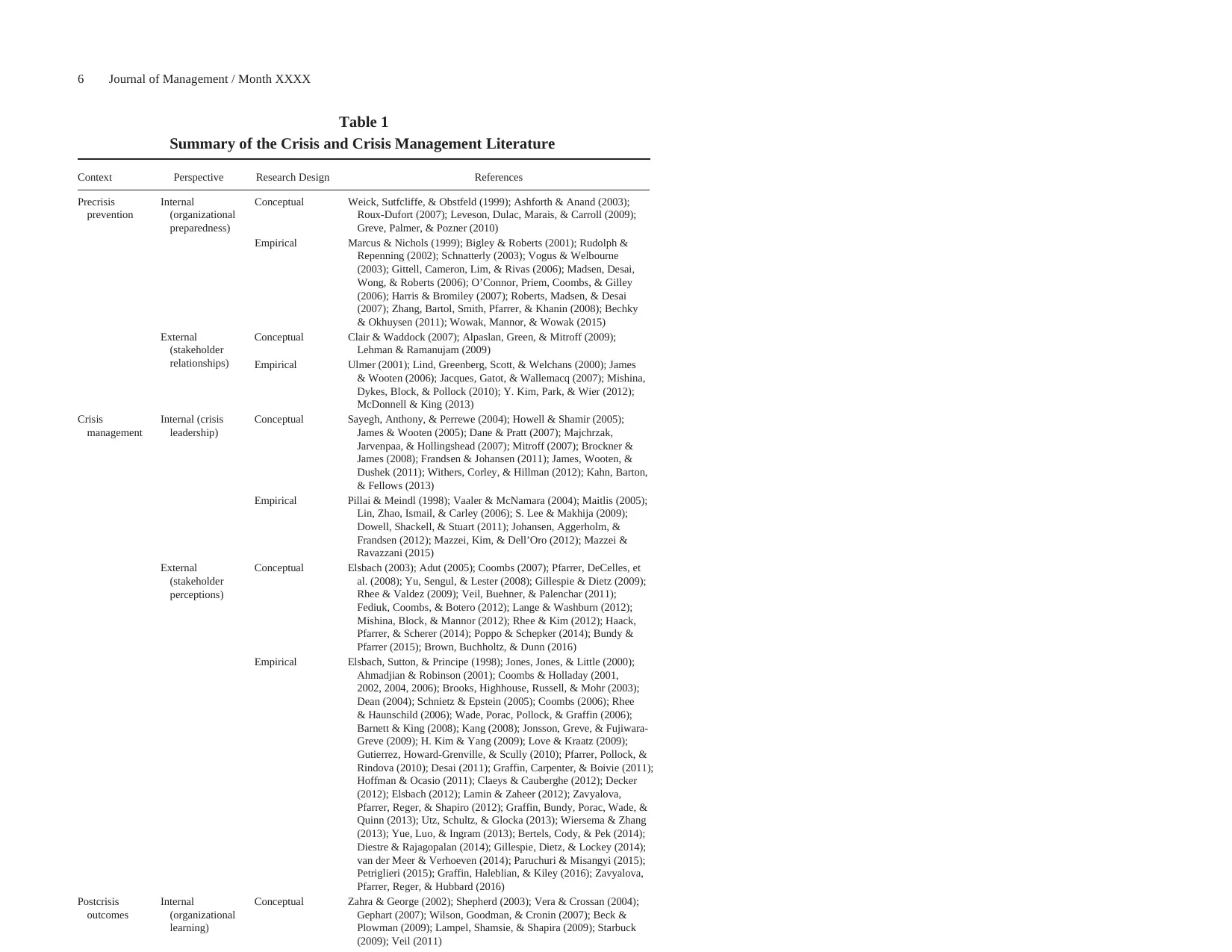

Table 1

Summary of the Crisis and Crisis Management Literature

Context Perspective Research Design References

Precrisis

prevention

Internal

(organizational

preparedness)

Conceptual Weick, Sutfcliffe, & Obstfeld (1999); Ashforth & Anand (2003);

Roux-Dufort (2007); Leveson, Dulac, Marais, & Carroll (2009);

Greve, Palmer, & Pozner (2010)

Empirical Marcus & Nichols (1999); Bigley & Roberts (2001); Rudolph &

Repenning (2002); Schnatterly (2003); Vogus & Welbourne

(2003); Gittell, Cameron, Lim, & Rivas (2006); Madsen, Desai,

Wong, & Roberts (2006); O’Connor, Priem, Coombs, & Gilley

(2006); Harris & Bromiley (2007); Roberts, Madsen, & Desai

(2007); Zhang, Bartol, Smith, Pfarrer, & Khanin (2008); Bechky

& Okhuysen (2011); Wowak, Mannor, & Wowak (2015)

External

(stakeholder

relationships)

Conceptual Clair & Waddock (2007); Alpaslan, Green, & Mitroff (2009);

Lehman & Ramanujam (2009)

Empirical Ulmer (2001); Lind, Greenberg, Scott, & Welchans (2000); James

& Wooten (2006); Jacques, Gatot, & Wallemacq (2007); Mishina,

Dykes, Block, & Pollock (2010); Y. Kim, Park, & Wier (2012);

McDonnell & King (2013)

Crisis

management

Internal (crisis

leadership)

Conceptual Sayegh, Anthony, & Perrewe (2004); Howell & Shamir (2005);

James & Wooten (2005); Dane & Pratt (2007); Majchrzak,

Jarvenpaa, & Hollingshead (2007); Mitroff (2007); Brockner &

James (2008); Frandsen & Johansen (2011); James, Wooten, &

Dushek (2011); Withers, Corley, & Hillman (2012); Kahn, Barton,

& Fellows (2013)

Empirical Pillai & Meindl (1998); Vaaler & McNamara (2004); Maitlis (2005);

Lin, Zhao, Ismail, & Carley (2006); S. Lee & Makhija (2009);

Dowell, Shackell, & Stuart (2011); Johansen, Aggerholm, &

Frandsen (2012); Mazzei, Kim, & Dell’Oro (2012); Mazzei &

Ravazzani (2015)

External

(stakeholder

perceptions)

Conceptual Elsbach (2003); Adut (2005); Coombs (2007); Pfarrer, DeCelles, et

al. (2008); Yu, Sengul, & Lester (2008); Gillespie & Dietz (2009);

Rhee & Valdez (2009); Veil, Buehner, & Palenchar (2011);

Fediuk, Coombs, & Botero (2012); Lange & Washburn (2012);

Mishina, Block, & Mannor (2012); Rhee & Kim (2012); Haack,

Pfarrer, & Scherer (2014); Poppo & Schepker (2014); Bundy &

Pfarrer (2015); Brown, Buchholtz, & Dunn (2016)

Empirical Elsbach, Sutton, & Principe (1998); Jones, Jones, & Little (2000);

Ahmadjian & Robinson (2001); Coombs & Holladay (2001,

2002, 2004, 2006); Brooks, Highhouse, Russell, & Mohr (2003);

Dean (2004); Schnietz & Epstein (2005); Coombs (2006); Rhee

& Haunschild (2006); Wade, Porac, Pollock, & Graffin (2006);

Barnett & King (2008); Kang (2008); Jonsson, Greve, & Fujiwara-

Greve (2009); H. Kim & Yang (2009); Love & Kraatz (2009);

Gutierrez, Howard-Grenville, & Scully (2010); Pfarrer, Pollock, &

Rindova (2010); Desai (2011); Graffin, Carpenter, & Boivie (2011);

Hoffman & Ocasio (2011); Claeys & Cauberghe (2012); Decker

(2012); Elsbach (2012); Lamin & Zaheer (2012); Zavyalova,

Pfarrer, Reger, & Shapiro (2012); Graffin, Bundy, Porac, Wade, &

Quinn (2013); Utz, Schultz, & Glocka (2013); Wiersema & Zhang

(2013); Yue, Luo, & Ingram (2013); Bertels, Cody, & Pek (2014);

Diestre & Rajagopalan (2014); Gillespie, Dietz, & Lockey (2014);

van der Meer & Verhoeven (2014); Paruchuri & Misangyi (2015);

Petriglieri (2015); Graffin, Haleblian, & Kiley (2016); Zavyalova,

Pfarrer, Reger, & Hubbard (2016)

Postcrisis

outcomes

Internal

(organizational

learning)

Conceptual Zahra & George (2002); Shepherd (2003); Vera & Crossan (2004);

Gephart (2007); Wilson, Goodman, & Cronin (2007); Beck &

Plowman (2009); Lampel, Shamsie, & Shapira (2009); Starbuck

(2009); Veil (2011)

Table 1

Summary of the Crisis and Crisis Management Literature

Context Perspective Research Design References

Precrisis

prevention

Internal

(organizational

preparedness)

Conceptual Weick, Sutfcliffe, & Obstfeld (1999); Ashforth & Anand (2003);

Roux-Dufort (2007); Leveson, Dulac, Marais, & Carroll (2009);

Greve, Palmer, & Pozner (2010)

Empirical Marcus & Nichols (1999); Bigley & Roberts (2001); Rudolph &

Repenning (2002); Schnatterly (2003); Vogus & Welbourne

(2003); Gittell, Cameron, Lim, & Rivas (2006); Madsen, Desai,

Wong, & Roberts (2006); O’Connor, Priem, Coombs, & Gilley

(2006); Harris & Bromiley (2007); Roberts, Madsen, & Desai

(2007); Zhang, Bartol, Smith, Pfarrer, & Khanin (2008); Bechky

& Okhuysen (2011); Wowak, Mannor, & Wowak (2015)

External

(stakeholder

relationships)

Conceptual Clair & Waddock (2007); Alpaslan, Green, & Mitroff (2009);

Lehman & Ramanujam (2009)

Empirical Ulmer (2001); Lind, Greenberg, Scott, & Welchans (2000); James

& Wooten (2006); Jacques, Gatot, & Wallemacq (2007); Mishina,

Dykes, Block, & Pollock (2010); Y. Kim, Park, & Wier (2012);

McDonnell & King (2013)

Crisis

management

Internal (crisis

leadership)

Conceptual Sayegh, Anthony, & Perrewe (2004); Howell & Shamir (2005);

James & Wooten (2005); Dane & Pratt (2007); Majchrzak,

Jarvenpaa, & Hollingshead (2007); Mitroff (2007); Brockner &

James (2008); Frandsen & Johansen (2011); James, Wooten, &

Dushek (2011); Withers, Corley, & Hillman (2012); Kahn, Barton,

& Fellows (2013)

Empirical Pillai & Meindl (1998); Vaaler & McNamara (2004); Maitlis (2005);

Lin, Zhao, Ismail, & Carley (2006); S. Lee & Makhija (2009);

Dowell, Shackell, & Stuart (2011); Johansen, Aggerholm, &

Frandsen (2012); Mazzei, Kim, & Dell’Oro (2012); Mazzei &

Ravazzani (2015)

External

(stakeholder

perceptions)

Conceptual Elsbach (2003); Adut (2005); Coombs (2007); Pfarrer, DeCelles, et

al. (2008); Yu, Sengul, & Lester (2008); Gillespie & Dietz (2009);

Rhee & Valdez (2009); Veil, Buehner, & Palenchar (2011);

Fediuk, Coombs, & Botero (2012); Lange & Washburn (2012);

Mishina, Block, & Mannor (2012); Rhee & Kim (2012); Haack,

Pfarrer, & Scherer (2014); Poppo & Schepker (2014); Bundy &

Pfarrer (2015); Brown, Buchholtz, & Dunn (2016)

Empirical Elsbach, Sutton, & Principe (1998); Jones, Jones, & Little (2000);

Ahmadjian & Robinson (2001); Coombs & Holladay (2001,

2002, 2004, 2006); Brooks, Highhouse, Russell, & Mohr (2003);

Dean (2004); Schnietz & Epstein (2005); Coombs (2006); Rhee

& Haunschild (2006); Wade, Porac, Pollock, & Graffin (2006);

Barnett & King (2008); Kang (2008); Jonsson, Greve, & Fujiwara-

Greve (2009); H. Kim & Yang (2009); Love & Kraatz (2009);

Gutierrez, Howard-Grenville, & Scully (2010); Pfarrer, Pollock, &

Rindova (2010); Desai (2011); Graffin, Carpenter, & Boivie (2011);

Hoffman & Ocasio (2011); Claeys & Cauberghe (2012); Decker

(2012); Elsbach (2012); Lamin & Zaheer (2012); Zavyalova,

Pfarrer, Reger, & Shapiro (2012); Graffin, Bundy, Porac, Wade, &

Quinn (2013); Utz, Schultz, & Glocka (2013); Wiersema & Zhang

(2013); Yue, Luo, & Ingram (2013); Bertels, Cody, & Pek (2014);

Diestre & Rajagopalan (2014); Gillespie, Dietz, & Lockey (2014);

van der Meer & Verhoeven (2014); Paruchuri & Misangyi (2015);

Petriglieri (2015); Graffin, Haleblian, & Kiley (2016); Zavyalova,

Pfarrer, Reger, & Hubbard (2016)

Postcrisis

outcomes

Internal

(organizational

learning)

Conceptual Zahra & George (2002); Shepherd (2003); Vera & Crossan (2004);

Gephart (2007); Wilson, Goodman, & Cronin (2007); Beck &

Plowman (2009); Lampel, Shamsie, & Shapira (2009); Starbuck

(2009); Veil (2011)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Bundy et al. / Review of Crises and Crisis Management 7

Context Perspective Research Design References

Empirical Amabile & Conti (1999); Haunschild & Sullivan (2002); Elliott &

Smith (2006); Baum & Bahlin (2007); J. Kim & Miner (2007);

Christianson, Farkas, Sutcliffe, & Weick (2009); Madsen (2009);

Rerup (2009); Madsen & Desai (2010); Maguire & Hardy (2013);

Haunschild, Polidoro, & Chandler (2015)

External (social

evaluations)

Conceptual Hudson (2008); Pozner (2008); Devers, Dewett, Mishina, & Belsito

(2009); Tomlinson & Mryer (2009); Hudson & Okhuysen (2014)

Empirical Zyglidopoulos (2001); P. Kim, Ferrin, Cooper, & Dirks (2004);

F. Lee, Peterson, & Tiedens (2004); Tomlinson, Dineen, &

Lewicki (2004); Sinaceur, Heath, & Cole (2005); Coombs &

Holladay (2007); Dardis & Haigh (2009); Jin (2010); Jin, Pang, &

Cameron (2012); Claeys & Cauberghe (2014)

Table 1 (continued)

the roles of organizational culture and structure in how an organization can prepare for a

crisis.

Organizing for reliability. One influential stream of research focuses on high-reliability

organizations (e.g., Bigley & Roberts, 2001; Gittel, Cameron, Lim, & Rivas, 2006; Weick &

Sutcliffe, 2001; Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 1999). The overarching thesis from this stream

is that organizations can orient themselves—via changes in culture, design, and structure—to

prevent system breakdowns that may lead to crises. In this sense, a high-reliability organi-

zation has the capability to manage unexpected events, which results from a cognitive and

behavioral process of collective managerial “mindfulness” (Weick et al., 1999: 37; Weick

& Sutcliffe, 2001). While often studied in volatile industries or environments (e.g., nuclear

power, military, NASA, air traffic control, SWAT teams, and emergency health care), “high

reliability” can apply to any organization interested in managing complexity and seeking to

avoid crises.

For example, Bigley and Roberts (2001) focused on three aspects of high-reliability orga-

nizations: mechanisms that allow for the alteration of formal structures, leadership support

for improvisation, and methods that allow for enhanced sensemaking. As the authors noted,

to the extent an organization has the capacity to implement preplanned organizational solutions

rapidly enough to meet the more predictable aspects of an evolving incident, potential reaction

speed is increased, depletion of cognitive and other resources is reduced, and the probability of

organizational dysfunction is limited. (Bigley & Roberts, 2001: 1297; also see Madsen, Desai,

Wong, & Roberts, 2006; Roberts, Madsen, & Desai, 2007)

Building on this premise, other scholars have focused on the factors that may limit an

organization’s ability to organize for reliability, such as managers’ emotional and cognitive

limitations (Kahn et al., 2013; Roux-Dufort, 2007), the number of organizational disruptions

(Rudolph & Repenning, 2002), the availability and use of organizational resources (Marcus

& Nichols, 1999), and the roles of practices and structures used to promote reliability (Lin,

Zhao, Ismail, & Carley, 2006; Vogus & Welbourne, 2003).

Organizational culture and structure. Research from the internal perspective has also

Context Perspective Research Design References

Empirical Amabile & Conti (1999); Haunschild & Sullivan (2002); Elliott &

Smith (2006); Baum & Bahlin (2007); J. Kim & Miner (2007);

Christianson, Farkas, Sutcliffe, & Weick (2009); Madsen (2009);

Rerup (2009); Madsen & Desai (2010); Maguire & Hardy (2013);

Haunschild, Polidoro, & Chandler (2015)

External (social

evaluations)

Conceptual Hudson (2008); Pozner (2008); Devers, Dewett, Mishina, & Belsito

(2009); Tomlinson & Mryer (2009); Hudson & Okhuysen (2014)

Empirical Zyglidopoulos (2001); P. Kim, Ferrin, Cooper, & Dirks (2004);

F. Lee, Peterson, & Tiedens (2004); Tomlinson, Dineen, &

Lewicki (2004); Sinaceur, Heath, & Cole (2005); Coombs &

Holladay (2007); Dardis & Haigh (2009); Jin (2010); Jin, Pang, &

Cameron (2012); Claeys & Cauberghe (2014)

Table 1 (continued)

the roles of organizational culture and structure in how an organization can prepare for a

crisis.

Organizing for reliability. One influential stream of research focuses on high-reliability

organizations (e.g., Bigley & Roberts, 2001; Gittel, Cameron, Lim, & Rivas, 2006; Weick &

Sutcliffe, 2001; Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 1999). The overarching thesis from this stream

is that organizations can orient themselves—via changes in culture, design, and structure—to

prevent system breakdowns that may lead to crises. In this sense, a high-reliability organi-

zation has the capability to manage unexpected events, which results from a cognitive and

behavioral process of collective managerial “mindfulness” (Weick et al., 1999: 37; Weick

& Sutcliffe, 2001). While often studied in volatile industries or environments (e.g., nuclear

power, military, NASA, air traffic control, SWAT teams, and emergency health care), “high

reliability” can apply to any organization interested in managing complexity and seeking to

avoid crises.

For example, Bigley and Roberts (2001) focused on three aspects of high-reliability orga-

nizations: mechanisms that allow for the alteration of formal structures, leadership support

for improvisation, and methods that allow for enhanced sensemaking. As the authors noted,

to the extent an organization has the capacity to implement preplanned organizational solutions

rapidly enough to meet the more predictable aspects of an evolving incident, potential reaction

speed is increased, depletion of cognitive and other resources is reduced, and the probability of

organizational dysfunction is limited. (Bigley & Roberts, 2001: 1297; also see Madsen, Desai,

Wong, & Roberts, 2006; Roberts, Madsen, & Desai, 2007)

Building on this premise, other scholars have focused on the factors that may limit an

organization’s ability to organize for reliability, such as managers’ emotional and cognitive

limitations (Kahn et al., 2013; Roux-Dufort, 2007), the number of organizational disruptions

(Rudolph & Repenning, 2002), the availability and use of organizational resources (Marcus

& Nichols, 1999), and the roles of practices and structures used to promote reliability (Lin,

Zhao, Ismail, & Carley, 2006; Vogus & Welbourne, 2003).

Organizational culture and structure. Research from the internal perspective has also

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

culture, governance, and compensation structure (Ashforth & Anand, 2003; Greve, Palmer,

& Pozner, 2010; Harris & Bromiley, 2007; O’Connor, Priem, Coombs, & Gilley, 2006; Pfar-

rer, DeCelles, et al., 2008; Pfarrer, Smith, Bartol, Khanin, & Zhang, 2008; Schnatterly, 2003;

Zhang, Bartol, Smith, Pfarrer, & Khanin, 2008). For example, Greve and colleagues (2010)

and Ashforth and Anand (2003) argued that an organization’s culture can be more accepting

of misconduct, often resulting from managerial aspirations or power contests. Similarly, in her

study of corporate governance structures, Schnatterly (2003) found that certain governance

practices—including the clarity of policies and communication—were more effective at pre-

venting white-collar crime than other governance structures, such as increasing the percentage

of outsiders on the board. Finally, research has also shown that certain executive compensa-

tion arrangements—including the use of out-of-the-money stock options—may encourage

financial fraud and risk taking to increase the likelihood of a crisis (e.g., Harris & Bromiley,

2007; O’Connor et al., 2006; Wowak, Mannor, & Wowak, 2015; Zhang et al., 2008).

Summary. Three elements emerge from the internal perspective’s focus on organiza-

tional preparedness: First, organizing for high reliability is often treated as a cognitive and

behavioral task. Second, numerous studies suggest that high-reliability organizations are

more capable of preventing crises. Third, other factors may influence the likelihood of a

crisis occurring, including organizational culture and structure. While not directly studied,

it can be assumed that the cultural and structural factors increasing the likelihood of a crisis

also make it more difficult to organize for reliability. Testing this assumption provides an

excellent opportunity for future research. For example, scholars could consider how differ-

ent compensation or governance structures influence the process of organizing for reliability.

We also note that research on high-reliability organizations specifically, and organiza-

tional preparedness in general, has been criticized for lacking specificity (Leveson, Dulac,

Marais, & Carroll, 2009). For example, Bigley and Roberts (2001: 1295) recognized the

“somewhat abstract” nature of their theory and suggested that a more “comprehensive and

detailed treatment” of high-reliability organizations is needed. Our review of the literature

suggests that this detailed treatment has yet to fully materialize. Additionally, most high-

reliability studies are case based and focus on atypical, highly volatile environments, limiting

their generalizability (Leveson et al., 2009). As such, examinations of more “typical” organi-

zations remain underdeveloped (cf. Vogus & Welbourne, 2003).

External Perspective: Stakeholder Relationships

In contrast to the internal focus on organizational preparedness, precrisis research from

the external perspective highlights the role of stakeholder relationships. We identified two

streams within this area that focus on positive and negative relationships, respectively.

Positive stakeholder relationships. Precrisis prevention research from the external per-

spective argues that maintaining positive relationships with stakeholders can reduce the

likelihood of a crisis (Clair & Waddock, 2007; Coombs, 2007; Pfarrer, DeCelles, et al.,

2008; Ulmer, 2001; Ulmer & Sellnow, 2002). For example, Clair and Waddock (2007: 299)

proposed a “total responsibility management” approach, which focused on the importance

of recognizing an organization’s responsibilities to stakeholders in order to enhance crisis

culture, governance, and compensation structure (Ashforth & Anand, 2003; Greve, Palmer,

& Pozner, 2010; Harris & Bromiley, 2007; O’Connor, Priem, Coombs, & Gilley, 2006; Pfar-

rer, DeCelles, et al., 2008; Pfarrer, Smith, Bartol, Khanin, & Zhang, 2008; Schnatterly, 2003;

Zhang, Bartol, Smith, Pfarrer, & Khanin, 2008). For example, Greve and colleagues (2010)

and Ashforth and Anand (2003) argued that an organization’s culture can be more accepting

of misconduct, often resulting from managerial aspirations or power contests. Similarly, in her

study of corporate governance structures, Schnatterly (2003) found that certain governance

practices—including the clarity of policies and communication—were more effective at pre-

venting white-collar crime than other governance structures, such as increasing the percentage

of outsiders on the board. Finally, research has also shown that certain executive compensa-

tion arrangements—including the use of out-of-the-money stock options—may encourage

financial fraud and risk taking to increase the likelihood of a crisis (e.g., Harris & Bromiley,

2007; O’Connor et al., 2006; Wowak, Mannor, & Wowak, 2015; Zhang et al., 2008).

Summary. Three elements emerge from the internal perspective’s focus on organiza-

tional preparedness: First, organizing for high reliability is often treated as a cognitive and

behavioral task. Second, numerous studies suggest that high-reliability organizations are

more capable of preventing crises. Third, other factors may influence the likelihood of a

crisis occurring, including organizational culture and structure. While not directly studied,

it can be assumed that the cultural and structural factors increasing the likelihood of a crisis

also make it more difficult to organize for reliability. Testing this assumption provides an

excellent opportunity for future research. For example, scholars could consider how differ-

ent compensation or governance structures influence the process of organizing for reliability.

We also note that research on high-reliability organizations specifically, and organiza-

tional preparedness in general, has been criticized for lacking specificity (Leveson, Dulac,

Marais, & Carroll, 2009). For example, Bigley and Roberts (2001: 1295) recognized the

“somewhat abstract” nature of their theory and suggested that a more “comprehensive and

detailed treatment” of high-reliability organizations is needed. Our review of the literature

suggests that this detailed treatment has yet to fully materialize. Additionally, most high-

reliability studies are case based and focus on atypical, highly volatile environments, limiting

their generalizability (Leveson et al., 2009). As such, examinations of more “typical” organi-

zations remain underdeveloped (cf. Vogus & Welbourne, 2003).

External Perspective: Stakeholder Relationships

In contrast to the internal focus on organizational preparedness, precrisis research from

the external perspective highlights the role of stakeholder relationships. We identified two

streams within this area that focus on positive and negative relationships, respectively.

Positive stakeholder relationships. Precrisis prevention research from the external per-

spective argues that maintaining positive relationships with stakeholders can reduce the

likelihood of a crisis (Clair & Waddock, 2007; Coombs, 2007; Pfarrer, DeCelles, et al.,

2008; Ulmer, 2001; Ulmer & Sellnow, 2002). For example, Clair and Waddock (2007: 299)

proposed a “total responsibility management” approach, which focused on the importance

of recognizing an organization’s responsibilities to stakeholders in order to enhance crisis

Bundy et al. / Review of Crises and Crisis Management 9

detection and prevention (also see Alpaslan, Green, & Mitroff, 2009). Using similar logic,

Kahn and colleagues (2013) theorized how relational cohesion, flexibility, and open commu-

nication between internal and external stakeholders can help prevent crises (also see Ulmer,

Sellnow, & Seeger, 2011). Finally, Coombs (2015: 107) noted that “stakeholders should be

part of the prevention thinking and process,” and that stakeholders can help in both identify-

ing and mitigating the risks that may lead to a crisis.

Whereas research in this area is theoretically diverse, empirical investigations remain

limited. While some studies provide evidence that positive stakeholder relationships can

mitigate the potential damage from a crisis—including Ulmer’s (2001) examination of an

industrial fire at Malden Mills and Coombs and Holladay’s (2001) study of stakeholder rela-

tionships in accident crises—few have directly examined the link between positive relation-

ships and the likelihood of a crisis occurring. For example, future research could examine the

relationship between corporate social performance (CSP) and the likelihood of a crisis. That

is, if CSP is an indicator of having positive stakeholder relationships, then organizations with

higher CSP scores should experience fewer crises, all else equal.

Negative stakeholder relationships. In contrast to the positive view detailed above,

other scholars have considered the negative side of stakeholder relationships. For example,

Mishina, Dykes, Block, and Pollock (2010) found that prior positive organizational perfor-

mance increases stakeholders’ expectations for future positive performance and that organi-

zations may engage in illegal behavior in order to meet these expectations (also see Lehman

& Ramanujam, 2009). Greve and colleagues (2010: 64) highlighted this social pressure as

an example of “strain theory,” which posits that “actors resort to misconduct when they are

unable to achieve their goals through legitimate means.” As such, the pressures associated

with meeting stakeholders’ expectations may encourage organizational behavior that can

lead to a crisis.

Additionally, scholars have also considered how negative relationships with stakeholders

may trigger a crisis in the form of retaliatory action, including protests, activism, boycotts, and

lawsuits (James & Wooten, 2006; Lind, Greenberg, Scott, & Welchans, 2000; McDonnell &

King, 2013). For example, James and Wooten (2006) considered negative relationships in the

context of discrimination lawsuits, and McDonnell and King (2013) studied the influence of

an organization’s positive and negative relationships in the context of consumer boycotts.

Summary. The external perspective’s focus on stakeholder relationships in the precri-

sis prevention stage suggests the following: Fostering positive stakeholder relationships is

essential, as negative relationships can cause or escalate crises. Positive relationships also

need to be founded on reasonable expectations and open lines of communication in order

to avoid the strain associated with untenable goals. Establishing such a foundation is likely

the responsibility of both organizations and stakeholders, as organizations must focus on

managing expectations and communicating transparently, while stakeholders need to be

mindful of inflated expectations and associated biases (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015). Of course,

while managing expectations may help prevent a crisis, this may have negative implications

on organizational performance. For example, shareholders may perceive attempts to man-

age expectations negatively, particularly in the aftermath of positive performance. As such,

an opportunity for future research would be to investigate the potential tradeoffs that exist

detection and prevention (also see Alpaslan, Green, & Mitroff, 2009). Using similar logic,

Kahn and colleagues (2013) theorized how relational cohesion, flexibility, and open commu-

nication between internal and external stakeholders can help prevent crises (also see Ulmer,

Sellnow, & Seeger, 2011). Finally, Coombs (2015: 107) noted that “stakeholders should be

part of the prevention thinking and process,” and that stakeholders can help in both identify-

ing and mitigating the risks that may lead to a crisis.

Whereas research in this area is theoretically diverse, empirical investigations remain

limited. While some studies provide evidence that positive stakeholder relationships can

mitigate the potential damage from a crisis—including Ulmer’s (2001) examination of an

industrial fire at Malden Mills and Coombs and Holladay’s (2001) study of stakeholder rela-

tionships in accident crises—few have directly examined the link between positive relation-

ships and the likelihood of a crisis occurring. For example, future research could examine the

relationship between corporate social performance (CSP) and the likelihood of a crisis. That

is, if CSP is an indicator of having positive stakeholder relationships, then organizations with

higher CSP scores should experience fewer crises, all else equal.

Negative stakeholder relationships. In contrast to the positive view detailed above,

other scholars have considered the negative side of stakeholder relationships. For example,

Mishina, Dykes, Block, and Pollock (2010) found that prior positive organizational perfor-

mance increases stakeholders’ expectations for future positive performance and that organi-

zations may engage in illegal behavior in order to meet these expectations (also see Lehman

& Ramanujam, 2009). Greve and colleagues (2010: 64) highlighted this social pressure as

an example of “strain theory,” which posits that “actors resort to misconduct when they are

unable to achieve their goals through legitimate means.” As such, the pressures associated

with meeting stakeholders’ expectations may encourage organizational behavior that can

lead to a crisis.

Additionally, scholars have also considered how negative relationships with stakeholders

may trigger a crisis in the form of retaliatory action, including protests, activism, boycotts, and

lawsuits (James & Wooten, 2006; Lind, Greenberg, Scott, & Welchans, 2000; McDonnell &

King, 2013). For example, James and Wooten (2006) considered negative relationships in the

context of discrimination lawsuits, and McDonnell and King (2013) studied the influence of

an organization’s positive and negative relationships in the context of consumer boycotts.

Summary. The external perspective’s focus on stakeholder relationships in the precri-

sis prevention stage suggests the following: Fostering positive stakeholder relationships is

essential, as negative relationships can cause or escalate crises. Positive relationships also

need to be founded on reasonable expectations and open lines of communication in order

to avoid the strain associated with untenable goals. Establishing such a foundation is likely

the responsibility of both organizations and stakeholders, as organizations must focus on

managing expectations and communicating transparently, while stakeholders need to be

mindful of inflated expectations and associated biases (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015). Of course,

while managing expectations may help prevent a crisis, this may have negative implications

on organizational performance. For example, shareholders may perceive attempts to man-

age expectations negatively, particularly in the aftermath of positive performance. As such,

an opportunity for future research would be to investigate the potential tradeoffs that exist

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

between organizations’ attempts to manage stakeholders’ expectations, the likelihood of a

crisis, and financial performance.

Synthesizing the Perspectives

The internal perspective’s focus on organizational preparedness and the external perspec-

tive’s focus on stakeholder relationships share a number of commonalities. For example, orga-

nizing for reliability is a process of developing managerial mindfulness generally focused on

the internal operational environment. Similarly, research on stakeholder relationships empha-

sizes the importance of being mindful of relational expectations and obligations. Both per-

spectives also focus on identifying behavioral and social constraints that may interfere with

mindful organizing and relationship building (e.g., biases, limitations, and expectations).

Despite these commonalities, we found only limited evidence of research that considers

both perspectives together (cf. Clair & Waddock, 2007; Gittell, Cameron, Lim, & Rivas,

2006; Kahn et al., 2013; Jacques, Gatot, & Wallemacq, 2007; Pfarrer, DeCelles, et al., 2008;

Roux-Dufort, 2007). Thus, questions for future research remain. For example, how might

efforts to organize for reliability influence the way in which an organization manages its

external stakeholder relationships? We know that organizing for reliability requires a focus

on flexibility and core responsibilities (Weick et al., 1999). Both of these traits are also criti-

cal for positive stakeholder relationships (Clair & Waddock, 2007; Ulmer et al., 2011).

Therefore, it appears that organizing for reliability should enhance an organization’s ability

to foster positive external stakeholder relationships and that the presence of these positive

relationships would enhance an organization’s ability to organize for reliability.

An alternative possibility arises, however, when considering managers’ bounded rational-

ity and cognitive limitations (Cyert & March, 1963; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2006). Executives

focused on developing internal structures to manage complex systems may be limited in their

ability to foster a wide range of positive stakeholder relationships. Similarly, managers

focused on their various stakeholders may be unable to focus on managing complex internal

systems. As such, it is possible that a balanced focus on internal and external crisis preven-

tion may be difficult to accomplish in practice.

Stage 2: Crisis Management

Moving from the precrisis prevention stage, a significant portion of research from the inter-

nal and external perspectives has focused on the processes associated with the crisis manage-

ment stage (see Figure 1 and Table 1 as well as Tables 2a and 2b in the online supplemental

material). Before considering the differences between the internal and external perspectives,

we note that the factors that work to prevent a crisis, including organizational preparedness

and positive stakeholder relationships, may also facilitate crisis management after a triggering

event. As such, many of the manuscripts reviewed above are also applicable here.

Internal Perspective: Crisis Leadership

As Kahn and colleagues (2013: 377) noted, “traditional models of crisis management are

rooted in a classic engineering mandate: identify and fix the problems in inputs and opera-

between organizations’ attempts to manage stakeholders’ expectations, the likelihood of a

crisis, and financial performance.

Synthesizing the Perspectives

The internal perspective’s focus on organizational preparedness and the external perspec-

tive’s focus on stakeholder relationships share a number of commonalities. For example, orga-

nizing for reliability is a process of developing managerial mindfulness generally focused on

the internal operational environment. Similarly, research on stakeholder relationships empha-

sizes the importance of being mindful of relational expectations and obligations. Both per-

spectives also focus on identifying behavioral and social constraints that may interfere with

mindful organizing and relationship building (e.g., biases, limitations, and expectations).

Despite these commonalities, we found only limited evidence of research that considers

both perspectives together (cf. Clair & Waddock, 2007; Gittell, Cameron, Lim, & Rivas,

2006; Kahn et al., 2013; Jacques, Gatot, & Wallemacq, 2007; Pfarrer, DeCelles, et al., 2008;

Roux-Dufort, 2007). Thus, questions for future research remain. For example, how might

efforts to organize for reliability influence the way in which an organization manages its

external stakeholder relationships? We know that organizing for reliability requires a focus

on flexibility and core responsibilities (Weick et al., 1999). Both of these traits are also criti-

cal for positive stakeholder relationships (Clair & Waddock, 2007; Ulmer et al., 2011).

Therefore, it appears that organizing for reliability should enhance an organization’s ability

to foster positive external stakeholder relationships and that the presence of these positive

relationships would enhance an organization’s ability to organize for reliability.

An alternative possibility arises, however, when considering managers’ bounded rational-

ity and cognitive limitations (Cyert & March, 1963; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2006). Executives

focused on developing internal structures to manage complex systems may be limited in their

ability to foster a wide range of positive stakeholder relationships. Similarly, managers

focused on their various stakeholders may be unable to focus on managing complex internal

systems. As such, it is possible that a balanced focus on internal and external crisis preven-

tion may be difficult to accomplish in practice.

Stage 2: Crisis Management

Moving from the precrisis prevention stage, a significant portion of research from the inter-

nal and external perspectives has focused on the processes associated with the crisis manage-

ment stage (see Figure 1 and Table 1 as well as Tables 2a and 2b in the online supplemental

material). Before considering the differences between the internal and external perspectives,

we note that the factors that work to prevent a crisis, including organizational preparedness

and positive stakeholder relationships, may also facilitate crisis management after a triggering

event. As such, many of the manuscripts reviewed above are also applicable here.

Internal Perspective: Crisis Leadership

As Kahn and colleagues (2013: 377) noted, “traditional models of crisis management are

rooted in a classic engineering mandate: identify and fix the problems in inputs and opera-

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Bundy et al. / Review of Crises and Crisis Management 11

beyond this mandate, the internal perspective continues to emphasize a “fix-the-problem”

approach, often by focusing on the factors that influence within-organization crisis leader-

ship. For example, James and colleagues (2011: 458) highlighted the importance of “crisis

handlers,” focusing not just on the “tactical aspects of management” during a crisis but also

on the “responsibilities of leading an organization in the pre- and post-crisis phases.” In par-

ticular, the authors emphasized the relationship between crisis perceptions and crisis leader-

ship, suggesting that leaders who frame crises as threats react more emotionally and are more

limited in their efforts, while leaders who frame crises as opportunities are more open-minded

and flexible (also see Brockner & James, 2008; Dane & Pratt, 2007; James & Wooten, 2005,

2010; Mitroff, 2007; Sayegh, Anthony, & Perrewe, 2004; Vaaler & McNamara, 2004). Others

have focused on characteristics of the crisis leader—such as charisma—and how such char-

acteristics may influence internal cohesion during a crisis (Howell & Shamir, 2005; James

et al., 2011; Pillai & Meindl, 1998).

Scholars have also considered how leaders at high-reliability organizations manage a cri-

sis, recognizing that the ability to adapt and change mental models in an emergency situation

can enhance coordination and effective communication (Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa, &

Hollingshead, 2007; Roberts et al., 2007). This suggests that not only does organizing for

reliability help to prevent a crisis, but it can also enhance leadership efforts in the event that

one occurs.

Conditional factors on crisis leadership. Research has also considered a number of

conditional factors that may affect internal leadership during a crisis. For example, With-

ers, Corley, and Hillman (2012) suggested that a quality board may reduce the impact of a

crisis and enhance leadership efforts. Similarly, Dowell, Shackell, and Stuart (2011) found

that organizations with independent and smaller boards, which are more capable of enacting

dynamic change, were less likely to experience failure following a crisis. The authors also

found that more powerful CEOs, who are better able to make rapid decisions, reduced the

likelihood of failure.

Moving beyond governance factors, Lin and colleagues (2006) demonstrated that the

complexity of an organization’s structure and task environment combines to influence crisis

management efforts, both positively and negatively. S. Lee and Makhija (2009) emphasized

the role of strategic flexibility in crisis management, which, like organizing for reliability,

can enhance leadership efforts. Others have considered how more tangible aspects of an

organization, such as size and age, influence crisis management, the greater of which may

inhibit leadership efforts during a crisis (Lange & Washburn, 2012; Rhee & Valdez, 2009).

Finally, researchers in corporate communication and public relations have recently begun to

focus on the role of internal crisis communication, showing the negative effects of neglecting

employees during a crisis (Mazzei & Ravazzani, 2015) as well as the positive effects of

engaging with them (Mazzei, Kim, & Dell’Oro, 2012), including the possibility of employ-

ees becoming outspoken defenders of the organization (Frandsen & Johansen, 2011;

Johansen, Aggerholm, & Frandsen, 2012).

Summary. The internal perspective suggests that leaders are critical to the crisis man-

agement process and that a number of factors influence their ability to lead. However,

much like the research on organizational preparedness, research on crisis leadership is

beyond this mandate, the internal perspective continues to emphasize a “fix-the-problem”

approach, often by focusing on the factors that influence within-organization crisis leader-

ship. For example, James and colleagues (2011: 458) highlighted the importance of “crisis

handlers,” focusing not just on the “tactical aspects of management” during a crisis but also

on the “responsibilities of leading an organization in the pre- and post-crisis phases.” In par-

ticular, the authors emphasized the relationship between crisis perceptions and crisis leader-

ship, suggesting that leaders who frame crises as threats react more emotionally and are more

limited in their efforts, while leaders who frame crises as opportunities are more open-minded

and flexible (also see Brockner & James, 2008; Dane & Pratt, 2007; James & Wooten, 2005,

2010; Mitroff, 2007; Sayegh, Anthony, & Perrewe, 2004; Vaaler & McNamara, 2004). Others

have focused on characteristics of the crisis leader—such as charisma—and how such char-

acteristics may influence internal cohesion during a crisis (Howell & Shamir, 2005; James

et al., 2011; Pillai & Meindl, 1998).

Scholars have also considered how leaders at high-reliability organizations manage a cri-

sis, recognizing that the ability to adapt and change mental models in an emergency situation

can enhance coordination and effective communication (Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa, &

Hollingshead, 2007; Roberts et al., 2007). This suggests that not only does organizing for

reliability help to prevent a crisis, but it can also enhance leadership efforts in the event that

one occurs.

Conditional factors on crisis leadership. Research has also considered a number of

conditional factors that may affect internal leadership during a crisis. For example, With-

ers, Corley, and Hillman (2012) suggested that a quality board may reduce the impact of a

crisis and enhance leadership efforts. Similarly, Dowell, Shackell, and Stuart (2011) found

that organizations with independent and smaller boards, which are more capable of enacting

dynamic change, were less likely to experience failure following a crisis. The authors also

found that more powerful CEOs, who are better able to make rapid decisions, reduced the

likelihood of failure.

Moving beyond governance factors, Lin and colleagues (2006) demonstrated that the

complexity of an organization’s structure and task environment combines to influence crisis

management efforts, both positively and negatively. S. Lee and Makhija (2009) emphasized

the role of strategic flexibility in crisis management, which, like organizing for reliability,

can enhance leadership efforts. Others have considered how more tangible aspects of an

organization, such as size and age, influence crisis management, the greater of which may

inhibit leadership efforts during a crisis (Lange & Washburn, 2012; Rhee & Valdez, 2009).

Finally, researchers in corporate communication and public relations have recently begun to

focus on the role of internal crisis communication, showing the negative effects of neglecting

employees during a crisis (Mazzei & Ravazzani, 2015) as well as the positive effects of

engaging with them (Mazzei, Kim, & Dell’Oro, 2012), including the possibility of employ-

ees becoming outspoken defenders of the organization (Frandsen & Johansen, 2011;

Johansen, Aggerholm, & Frandsen, 2012).

Summary. The internal perspective suggests that leaders are critical to the crisis man-

agement process and that a number of factors influence their ability to lead. However,

much like the research on organizational preparedness, research on crisis leadership is

12 Journal of Management / Month XXXX

often criticized for its lack of specificity. Indeed, attempts to empirically examine the rec-

ommendations of this literature, such as the development of organizational structures to

aid with information processing and resource allocation, have not found strong support (cf.

Lin et al., 2006). As Lin and colleagues (2006: 611) noted, “more exploration is needed to

extend current organizational theories” of crisis management, and “the way in which orga-

nizations should be designed to encourage adaptation” needs to be reconsidered (2006:

614). In their critique, they highlighted that critical and specific questions about how orga-

nizations should structure and coordinate to enhance crisis leadership remain unanswered

(Lin et al., 2006).

Additionally, how different internal factors combine to influence crisis management also

remains unclear. For example, as we noted above, research suggests that both a strong board

(Withers et al., 2012) and a powerful CEO (Dowell et al., 2011) should enhance internal

crisis leadership. However, strong boards may work to curb CEO power, and powerful CEOs

often seek to reduce board impact (Shen, 2003). Furthermore, research also shows that pow-

erful CEOs may take more risks (Zahra, Priem, & Rasheed, 2005), which may enhance the

likelihood of a crisis (Mishina et al., 2010). Thus, the factors that lead to more effective

internal crisis management may also paradoxically lead to more crises.

External Perspective: Stakeholder Perceptions

In contrast to the focus on internal crisis leadership, a great deal of research from the

external perspective has focused on how stakeholders perceive and react to crises and how

organizations influence these perceptions. Below we consider multiple elements of this

research.

Crisis response strategies. Numerous studies captured in our review focus on how orga-

nizations use crisis response strategies, or the “set of coordinated communication and actions

used to influence evaluators’ crisis perceptions” (Bundy & Pfarrer, 2015: 346). Much of this