Intraoperative Awareness: Incidence, Sequelae, and Prevention

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/31

|7

|6177

|24

Report

AI Summary

This report is a review article discussing intraoperative awareness, its incidence, sequelae, and prevention. The article explores the controversies and non-controversies surrounding awareness during anesthesia, including the effectiveness of the modified Brice interview in detecting awareness with explicit recall, and the higher incidence of awareness without explicit recall. It also examines the link between intraoperative awareness and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as the role of processed electroencephalographic monitoring in preventing awareness. Furthermore, it addresses the increased incidence of awareness when neuromuscular blocking agents are used. The review synthesizes evidence from multiple studies, highlighting key findings and implications for clinical practice and patient safety.

R E V I E W A R T I C L E

Intraoperative awareness: controversies

and non-controversies

G. A. Mashour1,* and M. S. Avidan2

1University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, and2Washington University School of Medicine,

St Louis, MO, USA

*Corresponding author. E-mail: gmashour@med.umich.edu

Abstract

Intraoperative awareness, with or without recall, continues to be a topic of clinical significance and neurobiological interest.

In this article, we review evidence pertaining to the incidence, sequelae, and prevention of intraoperative awareness. We also

assess which aspects of the complication are well understood (i.e. non-controversial) and which require further research for

clarification (i.e. controversial).

Key words: anaesthesia, awareness, consciousness, post-traumatic stress disorder

Editor’s key points

• Recent large prospective studies have addressed the

incidence, detection, and prevention of awareness under

general anaesthesia.

• While important controversies remain, a number of con-

cepts regarding intraoperative awareness can be consid-

ered non-controversial.

• Controversies remain in both the aetiological and the

neurobiological bases of awareness.

The unintended experience and memory of surgical or proced-

ural events can be devastating for patients and remains a dynam-

ic area of investigation. Intraoperative awareness, with or

without explicit episodic recall, is relevant to patient safety, stan-

dards for intraoperative monitoring, and the search for the neural

correlates of consciousness. The objective of this narrative

review is to assess the state of the field by addressing key topics

related to intraoperative awareness and to consider whether the

evidence associated with these topics should be deemed contro-

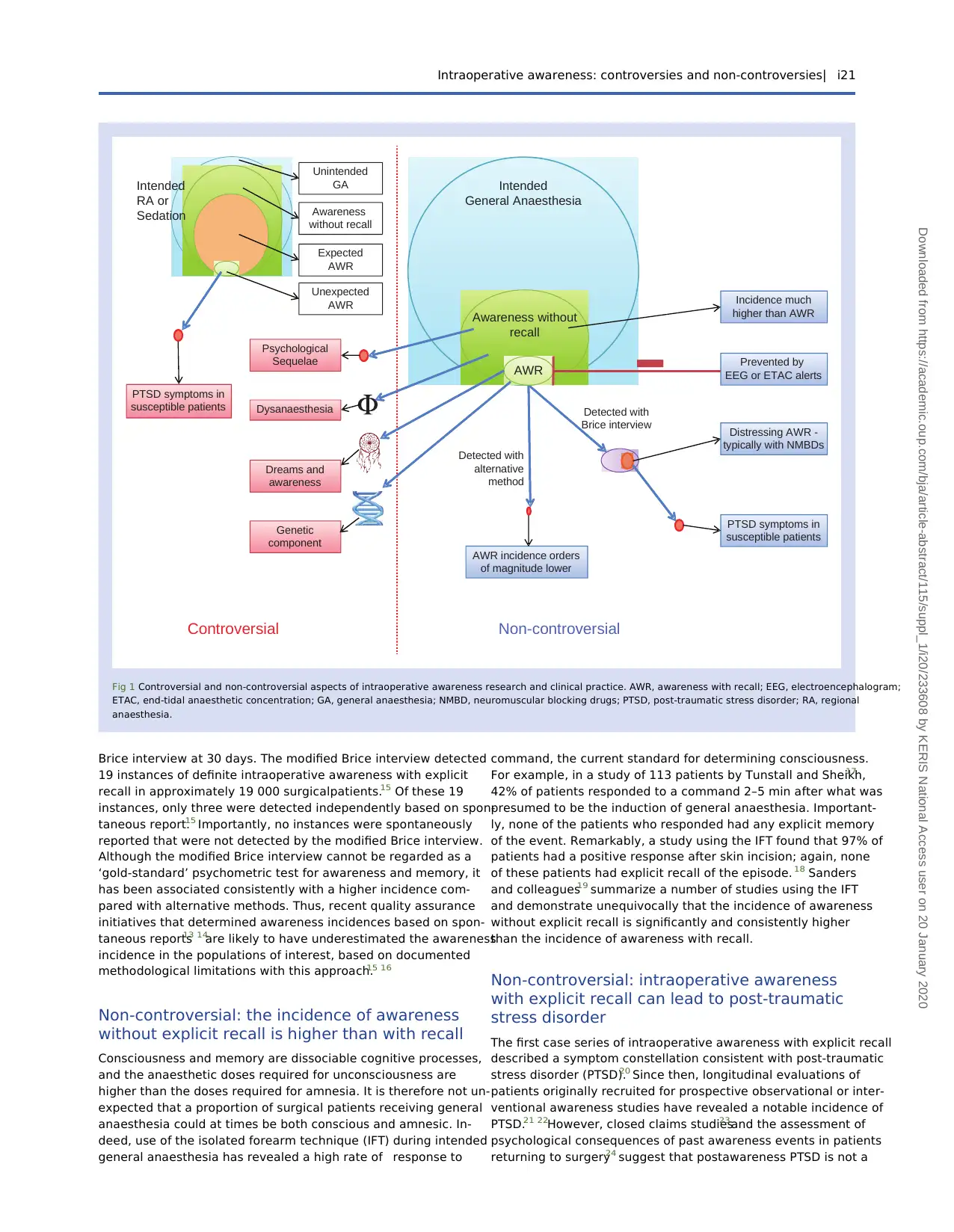

versial or non-controversial (see Figure 1 for summary).

Non-controversial: the modified Brice interview

detects more instances of intraoperative

awareness with explicit recall than alternative

methods

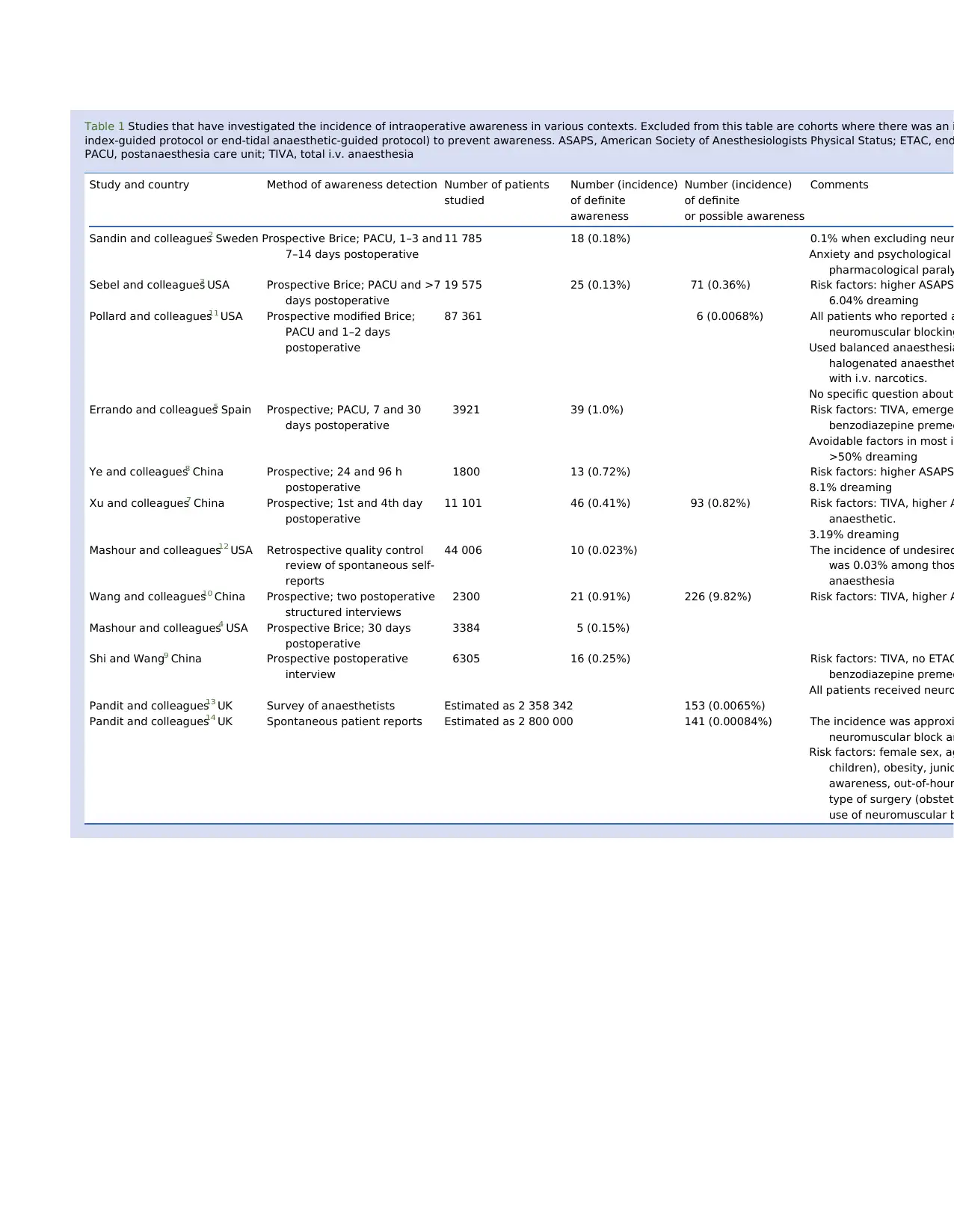

Multiple prospective studies using the modified Brice interview1

as the method of assessing intraoperative awareness with expli-

cit recall have consistently found an incidence of approximately

1–2 per 10002–4 or higher.5–10 In contrast, studies using in-

struments without specific questions pertaining to awareness

(such as Pollard and colleagues),11 quality assurance data (such

as Mashour and colleagues)12 or spontaneous reports [such as

the recent National Audit Project (NAP) 5]13 14 have consistently

found the incidence to be lower by an order of magnitude

(Table 1).11–14 It was unclear from these conflicting reports

whether the differences in incidence resulted from disparities

in patient population, anaesthetic technique, clinical severity,

or method of detection. In an attempt to resolve the controversy

across studies and study populations, Mashour and colleagues15

compared the incidence of intraoperative awareness with expli-

cit recall in a single population of surgical patients who received

both a standard postoperative evaluation (without a structured

interview intended to detect awareness) and a single modified

Accepted: December 4, 2014

© The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Journal of Anaesthesia. All rights reserved.

For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

British Journal of Anaesthesia 2015, i20–i26

doi: 10.1093/bja/aev034

Advance Access Publication Date: 3 March 2015

Review Article

i20

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

Intraoperative awareness: controversies

and non-controversies

G. A. Mashour1,* and M. S. Avidan2

1University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, and2Washington University School of Medicine,

St Louis, MO, USA

*Corresponding author. E-mail: gmashour@med.umich.edu

Abstract

Intraoperative awareness, with or without recall, continues to be a topic of clinical significance and neurobiological interest.

In this article, we review evidence pertaining to the incidence, sequelae, and prevention of intraoperative awareness. We also

assess which aspects of the complication are well understood (i.e. non-controversial) and which require further research for

clarification (i.e. controversial).

Key words: anaesthesia, awareness, consciousness, post-traumatic stress disorder

Editor’s key points

• Recent large prospective studies have addressed the

incidence, detection, and prevention of awareness under

general anaesthesia.

• While important controversies remain, a number of con-

cepts regarding intraoperative awareness can be consid-

ered non-controversial.

• Controversies remain in both the aetiological and the

neurobiological bases of awareness.

The unintended experience and memory of surgical or proced-

ural events can be devastating for patients and remains a dynam-

ic area of investigation. Intraoperative awareness, with or

without explicit episodic recall, is relevant to patient safety, stan-

dards for intraoperative monitoring, and the search for the neural

correlates of consciousness. The objective of this narrative

review is to assess the state of the field by addressing key topics

related to intraoperative awareness and to consider whether the

evidence associated with these topics should be deemed contro-

versial or non-controversial (see Figure 1 for summary).

Non-controversial: the modified Brice interview

detects more instances of intraoperative

awareness with explicit recall than alternative

methods

Multiple prospective studies using the modified Brice interview1

as the method of assessing intraoperative awareness with expli-

cit recall have consistently found an incidence of approximately

1–2 per 10002–4 or higher.5–10 In contrast, studies using in-

struments without specific questions pertaining to awareness

(such as Pollard and colleagues),11 quality assurance data (such

as Mashour and colleagues)12 or spontaneous reports [such as

the recent National Audit Project (NAP) 5]13 14 have consistently

found the incidence to be lower by an order of magnitude

(Table 1).11–14 It was unclear from these conflicting reports

whether the differences in incidence resulted from disparities

in patient population, anaesthetic technique, clinical severity,

or method of detection. In an attempt to resolve the controversy

across studies and study populations, Mashour and colleagues15

compared the incidence of intraoperative awareness with expli-

cit recall in a single population of surgical patients who received

both a standard postoperative evaluation (without a structured

interview intended to detect awareness) and a single modified

Accepted: December 4, 2014

© The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Journal of Anaesthesia. All rights reserved.

For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com

British Journal of Anaesthesia 2015, i20–i26

doi: 10.1093/bja/aev034

Advance Access Publication Date: 3 March 2015

Review Article

i20

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Brice interview at 30 days. The modified Brice interview detected

19 instances of definite intraoperative awareness with explicit

recall in approximately 19 000 surgicalpatients.15 Of these 19

instances, only three were detected independently based on spon-

taneous report.15 Importantly, no instances were spontaneously

reported that were not detected by the modified Brice interview.

Although the modified Brice interview cannot be regarded as a

‘gold-standard’ psychometric test for awareness and memory, it

has been associated consistently with a higher incidence com-

pared with alternative methods. Thus, recent quality assurance

initiatives that determined awareness incidences based on spon-

taneous reports13 14

are likely to have underestimated the awareness

incidence in the populations of interest, based on documented

methodological limitations with this approach.15 16

Non-controversial: the incidence of awareness

without explicit recall is higher than with recall

Consciousness and memory are dissociable cognitive processes,

and the anaesthetic doses required for unconsciousness are

higher than the doses required for amnesia. It is therefore not un-

expected that a proportion of surgical patients receiving general

anaesthesia could at times be both conscious and amnesic. In-

deed, use of the isolated forearm technique (IFT) during intended

general anaesthesia has revealed a high rate of response to

command, the current standard for determining consciousness.

For example, in a study of 113 patients by Tunstall and Sheikh,17

42% of patients responded to a command 2–5 min after what was

presumed to be the induction of general anaesthesia. Important-

ly, none of the patients who responded had any explicit memory

of the event. Remarkably, a study using the IFT found that 97% of

patients had a positive response after skin incision; again, none

of these patients had explicit recall of the episode. 18 Sanders

and colleagues19 summarize a number of studies using the IFT

and demonstrate unequivocally that the incidence of awareness

without explicit recall is significantly and consistently higher

than the incidence of awareness with recall.

Non-controversial: intraoperative awareness

with explicit recall can lead to post-traumatic

stress disorder

The first case series of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall

described a symptom constellation consistent with post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD).20 Since then, longitudinal evaluations of

patients originally recruited for prospective observational or inter-

ventional awareness studies have revealed a notable incidence of

PTSD.21 22However, closed claims studies23and the assessment of

psychological consequences of past awareness events in patients

returning to surgery24 suggest that postawareness PTSD is not a

AWR

Awareness without

recall

Intended

General Anaesthesia

Detected with

Brice interview

Detected with

alternative

method

Distressing AWR -

typically with NMBDs

PTSD symptoms in

susceptible patients

Prevented by

EEG or ETAC alerts

Non-controversialControversial

Unexpected

AWR

Unintended

GA

Expected

AWR

Awareness

without recall

PTSD symptoms in

susceptible patients

Psychological

Sequelae

Genetic

component

Dysanaesthesia

Dreams and

awareness

AWR incidence orders

of magnitude lower

Incidence much

higher than AWR

Intended

RA or

Sedation

Fig 1 Controversial and non-controversial aspects of intraoperative awareness research and clinical practice. AWR, awareness with recall; EEG, electroencephalogram;

ETAC, end-tidal anaesthetic concentration; GA, general anaesthesia; NMBD, neuromuscular blocking drugs; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RA, regional

anaesthesia.

Intraoperative awareness: controversies and non-controversies| i21

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

19 instances of definite intraoperative awareness with explicit

recall in approximately 19 000 surgicalpatients.15 Of these 19

instances, only three were detected independently based on spon-

taneous report.15 Importantly, no instances were spontaneously

reported that were not detected by the modified Brice interview.

Although the modified Brice interview cannot be regarded as a

‘gold-standard’ psychometric test for awareness and memory, it

has been associated consistently with a higher incidence com-

pared with alternative methods. Thus, recent quality assurance

initiatives that determined awareness incidences based on spon-

taneous reports13 14

are likely to have underestimated the awareness

incidence in the populations of interest, based on documented

methodological limitations with this approach.15 16

Non-controversial: the incidence of awareness

without explicit recall is higher than with recall

Consciousness and memory are dissociable cognitive processes,

and the anaesthetic doses required for unconsciousness are

higher than the doses required for amnesia. It is therefore not un-

expected that a proportion of surgical patients receiving general

anaesthesia could at times be both conscious and amnesic. In-

deed, use of the isolated forearm technique (IFT) during intended

general anaesthesia has revealed a high rate of response to

command, the current standard for determining consciousness.

For example, in a study of 113 patients by Tunstall and Sheikh,17

42% of patients responded to a command 2–5 min after what was

presumed to be the induction of general anaesthesia. Important-

ly, none of the patients who responded had any explicit memory

of the event. Remarkably, a study using the IFT found that 97% of

patients had a positive response after skin incision; again, none

of these patients had explicit recall of the episode. 18 Sanders

and colleagues19 summarize a number of studies using the IFT

and demonstrate unequivocally that the incidence of awareness

without explicit recall is significantly and consistently higher

than the incidence of awareness with recall.

Non-controversial: intraoperative awareness

with explicit recall can lead to post-traumatic

stress disorder

The first case series of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall

described a symptom constellation consistent with post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD).20 Since then, longitudinal evaluations of

patients originally recruited for prospective observational or inter-

ventional awareness studies have revealed a notable incidence of

PTSD.21 22However, closed claims studies23and the assessment of

psychological consequences of past awareness events in patients

returning to surgery24 suggest that postawareness PTSD is not a

AWR

Awareness without

recall

Intended

General Anaesthesia

Detected with

Brice interview

Detected with

alternative

method

Distressing AWR -

typically with NMBDs

PTSD symptoms in

susceptible patients

Prevented by

EEG or ETAC alerts

Non-controversialControversial

Unexpected

AWR

Unintended

GA

Expected

AWR

Awareness

without recall

PTSD symptoms in

susceptible patients

Psychological

Sequelae

Genetic

component

Dysanaesthesia

Dreams and

awareness

AWR incidence orders

of magnitude lower

Incidence much

higher than AWR

Intended

RA or

Sedation

Fig 1 Controversial and non-controversial aspects of intraoperative awareness research and clinical practice. AWR, awareness with recall; EEG, electroencephalogram;

ETAC, end-tidal anaesthetic concentration; GA, general anaesthesia; NMBD, neuromuscular blocking drugs; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RA, regional

anaesthesia.

Intraoperative awareness: controversies and non-controversies| i21

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

Table 1 Studies that have investigated the incidence of intraoperative awareness in various contexts. Excluded from this table are cohorts where there was an i

index-guided protocol or end-tidal anaesthetic-guided protocol) to prevent awareness. ASAPS, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status; ETAC, end

PACU, postanaesthesia care unit; TIVA, total i.v. anaesthesia

Study and country Method of awareness detection Number of patients

studied

Number (incidence)

of definite

awareness

Number (incidence)

of definite

or possible awareness

Comments

Sandin and colleagues2 Sweden Prospective Brice; PACU, 1–3 and

7–14 days postoperative

11 785 18 (0.18%) 0.1% when excluding neur

Anxiety and psychological

pharmacological paraly

Sebel and colleagues3 USA Prospective Brice; PACU and >7

days postoperative

19 575 25 (0.13%) 71 (0.36%) Risk factors: higher ASAPS

6.04% dreaming

Pollard and colleagues11 USA Prospective modified Brice;

PACU and 1–2 days

postoperative

87 361 6 (0.0068%) All patients who reported a

neuromuscular blocking

Used balanced anaesthesia

halogenated anaesthet

with i.v. narcotics.

No specific question about

Errando and colleagues5 Spain Prospective; PACU, 7 and 30

days postoperative

3921 39 (1.0%) Risk factors: TIVA, emerge

benzodiazepine premed

Avoidable factors in most in

>50% dreaming

Ye and colleagues8 China Prospective; 24 and 96 h

postoperative

1800 13 (0.72%) Risk factors: higher ASAPS

8.1% dreaming

Xu and colleagues7 China Prospective; 1st and 4th day

postoperative

11 101 46 (0.41%) 93 (0.82%) Risk factors: TIVA, higher A

anaesthetic.

3.19% dreaming

Mashour and colleagues12 USA Retrospective quality control

review of spontaneous self-

reports

44 006 10 (0.023%) The incidence of undesired

was 0.03% among thos

anaesthesia

Wang and colleagues10 China Prospective; two postoperative

structured interviews

2300 21 (0.91%) 226 (9.82%) Risk factors: TIVA, higher A

Mashour and colleagues4 USA Prospective Brice; 30 days

postoperative

3384 5 (0.15%)

Shi and Wang9 China Prospective postoperative

interview

6305 16 (0.25%) Risk factors: TIVA, no ETAC

benzodiazepine premed

All patients received neuro

Pandit and colleagues13 UK Survey of anaesthetists Estimated as 2 358 342 153 (0.0065%)

Pandit and colleagues14 UK Spontaneous patient reports Estimated as 2 800 000 141 (0.00084%) The incidence was approxi

neuromuscular block an

Risk factors: female sex, ag

children), obesity, junio

awareness, out-of-hour

type of surgery (obstet

use of neuromuscular b

index-guided protocol or end-tidal anaesthetic-guided protocol) to prevent awareness. ASAPS, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status; ETAC, end

PACU, postanaesthesia care unit; TIVA, total i.v. anaesthesia

Study and country Method of awareness detection Number of patients

studied

Number (incidence)

of definite

awareness

Number (incidence)

of definite

or possible awareness

Comments

Sandin and colleagues2 Sweden Prospective Brice; PACU, 1–3 and

7–14 days postoperative

11 785 18 (0.18%) 0.1% when excluding neur

Anxiety and psychological

pharmacological paraly

Sebel and colleagues3 USA Prospective Brice; PACU and >7

days postoperative

19 575 25 (0.13%) 71 (0.36%) Risk factors: higher ASAPS

6.04% dreaming

Pollard and colleagues11 USA Prospective modified Brice;

PACU and 1–2 days

postoperative

87 361 6 (0.0068%) All patients who reported a

neuromuscular blocking

Used balanced anaesthesia

halogenated anaesthet

with i.v. narcotics.

No specific question about

Errando and colleagues5 Spain Prospective; PACU, 7 and 30

days postoperative

3921 39 (1.0%) Risk factors: TIVA, emerge

benzodiazepine premed

Avoidable factors in most in

>50% dreaming

Ye and colleagues8 China Prospective; 24 and 96 h

postoperative

1800 13 (0.72%) Risk factors: higher ASAPS

8.1% dreaming

Xu and colleagues7 China Prospective; 1st and 4th day

postoperative

11 101 46 (0.41%) 93 (0.82%) Risk factors: TIVA, higher A

anaesthetic.

3.19% dreaming

Mashour and colleagues12 USA Retrospective quality control

review of spontaneous self-

reports

44 006 10 (0.023%) The incidence of undesired

was 0.03% among thos

anaesthesia

Wang and colleagues10 China Prospective; two postoperative

structured interviews

2300 21 (0.91%) 226 (9.82%) Risk factors: TIVA, higher A

Mashour and colleagues4 USA Prospective Brice; 30 days

postoperative

3384 5 (0.15%)

Shi and Wang9 China Prospective postoperative

interview

6305 16 (0.25%) Risk factors: TIVA, no ETAC

benzodiazepine premed

All patients received neuro

Pandit and colleagues13 UK Survey of anaesthetists Estimated as 2 358 342 153 (0.0065%)

Pandit and colleagues14 UK Spontaneous patient reports Estimated as 2 800 000 141 (0.00084%) The incidence was approxi

neuromuscular block an

Risk factors: female sex, ag

children), obesity, junio

awareness, out-of-hour

type of surgery (obstet

use of neuromuscular b

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

significant problem. In one study, even a long-term follow-up of

surgical patients who had been formally determined to have in-

traoperative awareness with explicit recall demonstrated no

long-term consequences.25 However, this might be attributable

to the fact that the initial experiences themselves were not par-

ticularly traumatic. A recent multicentre study demonstrates

that PTSD symptoms are indeed more common after definite or

possible awareness with recall,26 and the NAP5 audit highlights

the importance of neuromuscular paralysis in psychologically

traumatic experiences.27 Thus, although certain screening meth-

ods or patient populations might be associated with apparently

low incidences of PTSD after awareness reports, it is no longer a

matter of controversy as to whether or not intraoperative aware-

ness with explicit recall can lead to PTSD or PTSD symptoms.

Non-controversial: processed

electroencephalographic monitoring

is useful in preventing intraoperative

awareness with explicit recall compared

with clinical signs but not compared with

anaesthetic concentration alarms

The role of processed electroencephalographic devices, such as

the bispectral index (BIS) monitor, in the prevention of intrao-

perative awareness with explicit recall is sometimes regarded

as controversial, but should not be. Clear and consistent findings

have emerged from the five major randomized controlled trials

focused on the BIS.4 28–31The B-Aware trial28 demonstrated that

the BIS monitor was effective in reducing definite awareness

events compared with routine clinical care in patients at high

risk for the complication; this has also been demonstrated

for patients receiving total i.v. anaesthesia.31 In contrast, the

BAG-RECALL and B-Unaware trials demonstrated that alarms

based on the BIS are not superior to alarms based on end-tidal

anaesthetic concentration in preventing awareness with explicit

recall in patients at high risk for the complication.29 30The Mich-

igan Awareness Control Study has confirmed these findings

(i.e. BIS superior to clinical signs but not to anaesthetic concen-

tration alerts) in patients at all risk levels for awareness with ex-

plicit recall.4 An article synthesizing the evidence and an updated

Cochrane systematic review reflect the complementary findings

of all five studies, allowing a non-controversial recommendation

that, when patients receive neuromuscular blocking agents, the

BIS is superior to clinical signs alone, especially in patients

receiving total i.v. anaesthesia.32 33 An electroencephalographic

device may be particularly useful during total i.v. anaesthesia

because of higher interindividual variability of sedative–hypnotic

response and the inability routinely to monitor or set alarms for

i.v. anaesthetic levels. In contrast, BIS monitoring is not superior

at preventing awareness when a potent volatile anaesthetic

agent is administered and an alarm is set for a low anaesthetic

concentration.32 33 It is highly likely that the same findings

would hold true for other devices in the current generation of

processed electroencephalographic monitors.32

Non-controversial: the incidence of

intraoperative awareness and distressing

awareness is higher when neuromuscular

blocking agents are administered

It is self-evident that the avoidance of neuromuscular blocking

agents does not in itself prevent intraoperative awareness if in-

sufficient concentrations of hypnotic agents are administered.

In 1846, Abbott received ether for a tumour removal and was

aware, although not in pain, during the procedure.34Gray35popu-

larized the use of neuromuscular blocking agents as essential

components of general anaesthesia in Liverpool in the late

1940s. The underlying principle of the new technique was ‘min-

imal narcotization with adequate curarization.’ 35 The motiva-

tions were to minimize the cardiovascular depressant effects of

high concentrations of ether, cyclopropane, kemithal, or thio-

pental and to facilitate more rapid emergence of patients from

the vulnerable state of general anaesthesia after surgery.35 Des-

pite the advent of modern general anaesthetic agents over the

last four decades, with less cardiovascular depression and rapid

elimination, the practice of pharmacological paralysis with lim-

ited hypnotic administration continued to be popular and still

has proponents in modern practice. In the seminal observational

study by Sandin and colleagues,2 the incidence of unintended

awareness among patients who received general anaesthesia

without neuromuscular blocking agents was 0.1%, compared

with 0.18% when patients were pharmacologically paralysed.

A mundane explanation for the reduction in awareness in non-

pharmacologically paralysed patients is that patient movement

can potentially alert anaesthetists to the possibility of inad-

equate general anaesthesia. However, it is also possible that

the need for or use of neuromuscular blocking agents covaries

with other important risk factors for intraoperative awareness.

Interestingly, only patients who had been pharmacologically pa-

ralysed reported anxiety and psychological symptoms in rela-

tionship to their awareness experience. 2 In a comprehensive

literature review, Ghoneim and colleagues36endorsed the finding

that pharmacological paralysis was an important risk factor

for distressing awareness experiences. This important insight

has again been corroborated in the recently published NAP5

study,27 where the overwhelming majority of awareness reports

were from patients who had received neuromuscular blocking

drugs and also where the anaesthetic concentration was reduced

towards the end of surgery before antagonizing neuromuscular

blockade. The avoidance or minimization of pharmacological

paralysis might be the most effective currently available method

to prevent traumatic intraoperative awareness.

Controversial: intraoperative awareness with

explicit recall has a genetic component

It has been argued that awareness with recall is caused by insuf-

ficient anaesthetic dosing.36 37 Although this assertion is true in

what might be considered a tautological sense—that is, insuffi-

cient anaesthesia is caused by insufficient anaesthesia—the

argument is meant to suggest that awareness with explicit recall

is preventable by attention to anaesthetic dosing rather than the

search for occult factors that enable consciousness and memory

despite what reasonable clinicians might consider adequate

anaesthesia. It is well known based on experimental data that

genetic background can influence sensitivity to the sedative–

hypnotic and, independently, the amnesic effects of general

anaesthetics.38–41Furthermore, patients with a history of intrao-

perative awareness with explicit recall had an incidence of

awareness of almost 1 in 50 with subsequent surgery and an es-

timated five-fold adjusted increase in risk for awareness com-

pared with matched patients who also had at least one risk

factor for awareness.42 It is also striking that several studies in

Chinese populations have found surprisingly high incidences of

awareness.6 10 31 It is therefore unclear whether, in some in-

stances, genetically mediated resistance to anaesthetic-induced

Intraoperative awareness: controversies and non-controversies| i23

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

surgical patients who had been formally determined to have in-

traoperative awareness with explicit recall demonstrated no

long-term consequences.25 However, this might be attributable

to the fact that the initial experiences themselves were not par-

ticularly traumatic. A recent multicentre study demonstrates

that PTSD symptoms are indeed more common after definite or

possible awareness with recall,26 and the NAP5 audit highlights

the importance of neuromuscular paralysis in psychologically

traumatic experiences.27 Thus, although certain screening meth-

ods or patient populations might be associated with apparently

low incidences of PTSD after awareness reports, it is no longer a

matter of controversy as to whether or not intraoperative aware-

ness with explicit recall can lead to PTSD or PTSD symptoms.

Non-controversial: processed

electroencephalographic monitoring

is useful in preventing intraoperative

awareness with explicit recall compared

with clinical signs but not compared with

anaesthetic concentration alarms

The role of processed electroencephalographic devices, such as

the bispectral index (BIS) monitor, in the prevention of intrao-

perative awareness with explicit recall is sometimes regarded

as controversial, but should not be. Clear and consistent findings

have emerged from the five major randomized controlled trials

focused on the BIS.4 28–31The B-Aware trial28 demonstrated that

the BIS monitor was effective in reducing definite awareness

events compared with routine clinical care in patients at high

risk for the complication; this has also been demonstrated

for patients receiving total i.v. anaesthesia.31 In contrast, the

BAG-RECALL and B-Unaware trials demonstrated that alarms

based on the BIS are not superior to alarms based on end-tidal

anaesthetic concentration in preventing awareness with explicit

recall in patients at high risk for the complication.29 30The Mich-

igan Awareness Control Study has confirmed these findings

(i.e. BIS superior to clinical signs but not to anaesthetic concen-

tration alerts) in patients at all risk levels for awareness with ex-

plicit recall.4 An article synthesizing the evidence and an updated

Cochrane systematic review reflect the complementary findings

of all five studies, allowing a non-controversial recommendation

that, when patients receive neuromuscular blocking agents, the

BIS is superior to clinical signs alone, especially in patients

receiving total i.v. anaesthesia.32 33 An electroencephalographic

device may be particularly useful during total i.v. anaesthesia

because of higher interindividual variability of sedative–hypnotic

response and the inability routinely to monitor or set alarms for

i.v. anaesthetic levels. In contrast, BIS monitoring is not superior

at preventing awareness when a potent volatile anaesthetic

agent is administered and an alarm is set for a low anaesthetic

concentration.32 33 It is highly likely that the same findings

would hold true for other devices in the current generation of

processed electroencephalographic monitors.32

Non-controversial: the incidence of

intraoperative awareness and distressing

awareness is higher when neuromuscular

blocking agents are administered

It is self-evident that the avoidance of neuromuscular blocking

agents does not in itself prevent intraoperative awareness if in-

sufficient concentrations of hypnotic agents are administered.

In 1846, Abbott received ether for a tumour removal and was

aware, although not in pain, during the procedure.34Gray35popu-

larized the use of neuromuscular blocking agents as essential

components of general anaesthesia in Liverpool in the late

1940s. The underlying principle of the new technique was ‘min-

imal narcotization with adequate curarization.’ 35 The motiva-

tions were to minimize the cardiovascular depressant effects of

high concentrations of ether, cyclopropane, kemithal, or thio-

pental and to facilitate more rapid emergence of patients from

the vulnerable state of general anaesthesia after surgery.35 Des-

pite the advent of modern general anaesthetic agents over the

last four decades, with less cardiovascular depression and rapid

elimination, the practice of pharmacological paralysis with lim-

ited hypnotic administration continued to be popular and still

has proponents in modern practice. In the seminal observational

study by Sandin and colleagues,2 the incidence of unintended

awareness among patients who received general anaesthesia

without neuromuscular blocking agents was 0.1%, compared

with 0.18% when patients were pharmacologically paralysed.

A mundane explanation for the reduction in awareness in non-

pharmacologically paralysed patients is that patient movement

can potentially alert anaesthetists to the possibility of inad-

equate general anaesthesia. However, it is also possible that

the need for or use of neuromuscular blocking agents covaries

with other important risk factors for intraoperative awareness.

Interestingly, only patients who had been pharmacologically pa-

ralysed reported anxiety and psychological symptoms in rela-

tionship to their awareness experience. 2 In a comprehensive

literature review, Ghoneim and colleagues36endorsed the finding

that pharmacological paralysis was an important risk factor

for distressing awareness experiences. This important insight

has again been corroborated in the recently published NAP5

study,27 where the overwhelming majority of awareness reports

were from patients who had received neuromuscular blocking

drugs and also where the anaesthetic concentration was reduced

towards the end of surgery before antagonizing neuromuscular

blockade. The avoidance or minimization of pharmacological

paralysis might be the most effective currently available method

to prevent traumatic intraoperative awareness.

Controversial: intraoperative awareness with

explicit recall has a genetic component

It has been argued that awareness with recall is caused by insuf-

ficient anaesthetic dosing.36 37 Although this assertion is true in

what might be considered a tautological sense—that is, insuffi-

cient anaesthesia is caused by insufficient anaesthesia—the

argument is meant to suggest that awareness with explicit recall

is preventable by attention to anaesthetic dosing rather than the

search for occult factors that enable consciousness and memory

despite what reasonable clinicians might consider adequate

anaesthesia. It is well known based on experimental data that

genetic background can influence sensitivity to the sedative–

hypnotic and, independently, the amnesic effects of general

anaesthetics.38–41Furthermore, patients with a history of intrao-

perative awareness with explicit recall had an incidence of

awareness of almost 1 in 50 with subsequent surgery and an es-

timated five-fold adjusted increase in risk for awareness com-

pared with matched patients who also had at least one risk

factor for awareness.42 It is also striking that several studies in

Chinese populations have found surprisingly high incidences of

awareness.6 10 31 It is therefore unclear whether, in some in-

stances, genetically mediated resistance to anaesthetic-induced

Intraoperative awareness: controversies and non-controversies| i23

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

unconsciousness or amnesia contributes to awareness with re-

call. Furthermore, even assuming a genetic contribution to an-

aesthetic resistance, it is unclear whether reduced potency or

reduced efficacy is the primary cause, which has implications

for how best to alter anaesthetic care in patients at risk.

A pharmacogenomics approach might help to resolve this con-

troversy, although the rarity of the disorder and the probable

lack of parsimonious genetic culprits (e.g. single nucleotide poly-

morphisms) could render genetic explorations unhelpful.

Controversial: undesired awareness with

explicit recall of procedures performed under

sedation is a clinical problem

Self-reports of undesired intraoperative awareness with explicit

recall occur with the same frequency in patients receiving gen-

eral anaesthesia as in those receiving sedation, regional, or neur-

axial anaesthesia.12 This is likely to be the result of mismatched

expectations regarding levels of consciousness in patients who

are not receiving general anaesthesia during surgery or other in-

vasive procedures.43 Recent studies have suggested that un-

desired awareness and explicit recall in patients receiving

sedation, regional anaesthesia, or neuraxial anaesthesia can be

associated with long-term psychological consequences.27 44

A study based on the American Society of Anesthesiologists An-

esthesia Awareness Registry found comparable rates of long-

term psychological sequelae in those reporting awareness during

general anaesthesia and those reporting awareness during alter-

native anaesthetic techniques. 44 Recent data from the NAP5

study27 support the possibility that undesired awareness and

explicit recall during non-general anaesthetic procedures can

be associated with long-term psychological consequences. Al-

though these data would suggest that undesired awareness in

this population is a true clinical problem, the use of sedation

for minor procedures, such as endoscopy, is extremely common.

If psychological sequelae occurred in a significant proportion of

these instances, the absolute number of patient reports would

probably be a salient signal that would already have captured

the attention of medical professionals. Instead, this phenom-

enon has only recently been observed coincidentally through

systematic study of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall

after an intended general anaesthetic. Although the data remain

incomplete and controversial, it is important for anaesthesia pro-

viders to set appropriate expectations and ensure that patients

understand the planned level of consciousness and the potential

for remembering events during the surgery or procedure. In some

instances, this might mitigate the dissatisfaction with or conse-

quences of undesired awareness and recall.

Controversial: intraoperative awareness

without recall has psychological consequences

It is well known that the incidence of awareness without recall is

significantly higher than with recall. This situation generates an

important question: is it ethically acceptable if a patient is transi-

ently conscious but has no explicit memory of the event? Fur-

thermore, would the complete elimination of consciousness

during surgery require anaesthetic regimens that result in other

and potentially more dangerous adverse effects?45 It is a philo-

sophical question as to whether consciousness without memory

is ethically tenable during surgery, but the clinically relevant

question relates to the potential for postoperative psychological

consequences. Although we have focused on explicit recall in

relationship to conscious experience, there is also the possibility

of implicit (or unconscious) recall. It has been argued that impli-

cit recall of a surgical event—especially involving pain—might

result in PTSD even in the absence of explicit recall.46We support

the opinion that—independently of recall—appropriate anal-

gesia during surgery is of paramount importance given the

known potential for intraoperative awareness. However, it is

less clear whether there is compelling epidemiological evidence

for a negative effect of implicit memory on postoperative psycho-

logical function. Given the high incidence of awareness without

recall (as demonstrated by IFT studies)19—especially at the time

of strong nociceptive stimuli, such as laryngoscopy or surgical

incision—even a small proportion of patients experiencing psy-

chological sequelae as a result of implicit memory would trans-

late to a high absolute number of distressed patients. However,

the number of postoperative patients suffering PTSD without re-

call of surgical events appears to be low. When PTSD is precipi-

tated by perioperative events, the most likely contributing

factors include pain, prolonged intubation, unpleasant experi-

ences in the intensive care unit, physical debility, traumatic ex-

plicit memories, and distressing diagnoses. There is currently

little evidence to suggest that implicit memories are important

contributors. However, the dichotomous determination of PTSD

or not might be less relevant in awareness without recall; subsyn-

dromal PTSD must also be explored in addition to psychological

morbidity (such as mood or anxiety disorders) that cannot neces-

sarily be linked to an index event or experience. As a result of the

ethical implications of this controversy, further data are required.

Controversial: positive responses

to an isolated forearm test reflect

a distinct state of consciousness

A positive and unequivocal response to the command ‘squeeze

my hand’ at the end of a surgical procedure is traditionally

taken to constitute sufficient evidence that consciousness has re-

turned. Likewise, one could argue that a positive and unequivocal

response to the command ‘squeeze my hand’ during a surgical

procedure—for example, a positive IFT response—constitutes

sufficient evidence that consciousness has returned. Until there

is compelling evidence to the contrary, this should be the default

assumption. Sanders and colleagues19have clarified the possibil-

ities of perioperative behaviour and experience with a model of

responsiveness, connected consciousness, and disconnected

consciousness (e.g. a dream state). A recent theoretical perspec-

tive suggests an alternative possibility for IFT responses,

although no data have yet been provided. Pandit 47 48 argues

that the positive IFT response does not signify the full return or

persistence of consciousness but rather a ‘third state’ (referred

to as dysanaesthesia) in which patients can follow a simple com-

mand in the absence of a conscious self (see also Wang and col-

leagues, this issue). It is unclear, of course, whether such a state is

possible and, if so, what the candidate neural correlates would be.

This assertion is provocative but should be tested empirically and/

or potentially situated in broader frameworks of consciousness.49

Controversial: true reports of intraoperative

awareness can be distinguished reliably from

false reports of intraoperative awareness and

from dreaming

Detection of intraoperative awareness is unreliable because it

depends on patient reports rather than objective measures.

i24 | Mashour and Avidan

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

call. Furthermore, even assuming a genetic contribution to an-

aesthetic resistance, it is unclear whether reduced potency or

reduced efficacy is the primary cause, which has implications

for how best to alter anaesthetic care in patients at risk.

A pharmacogenomics approach might help to resolve this con-

troversy, although the rarity of the disorder and the probable

lack of parsimonious genetic culprits (e.g. single nucleotide poly-

morphisms) could render genetic explorations unhelpful.

Controversial: undesired awareness with

explicit recall of procedures performed under

sedation is a clinical problem

Self-reports of undesired intraoperative awareness with explicit

recall occur with the same frequency in patients receiving gen-

eral anaesthesia as in those receiving sedation, regional, or neur-

axial anaesthesia.12 This is likely to be the result of mismatched

expectations regarding levels of consciousness in patients who

are not receiving general anaesthesia during surgery or other in-

vasive procedures.43 Recent studies have suggested that un-

desired awareness and explicit recall in patients receiving

sedation, regional anaesthesia, or neuraxial anaesthesia can be

associated with long-term psychological consequences.27 44

A study based on the American Society of Anesthesiologists An-

esthesia Awareness Registry found comparable rates of long-

term psychological sequelae in those reporting awareness during

general anaesthesia and those reporting awareness during alter-

native anaesthetic techniques. 44 Recent data from the NAP5

study27 support the possibility that undesired awareness and

explicit recall during non-general anaesthetic procedures can

be associated with long-term psychological consequences. Al-

though these data would suggest that undesired awareness in

this population is a true clinical problem, the use of sedation

for minor procedures, such as endoscopy, is extremely common.

If psychological sequelae occurred in a significant proportion of

these instances, the absolute number of patient reports would

probably be a salient signal that would already have captured

the attention of medical professionals. Instead, this phenom-

enon has only recently been observed coincidentally through

systematic study of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall

after an intended general anaesthetic. Although the data remain

incomplete and controversial, it is important for anaesthesia pro-

viders to set appropriate expectations and ensure that patients

understand the planned level of consciousness and the potential

for remembering events during the surgery or procedure. In some

instances, this might mitigate the dissatisfaction with or conse-

quences of undesired awareness and recall.

Controversial: intraoperative awareness

without recall has psychological consequences

It is well known that the incidence of awareness without recall is

significantly higher than with recall. This situation generates an

important question: is it ethically acceptable if a patient is transi-

ently conscious but has no explicit memory of the event? Fur-

thermore, would the complete elimination of consciousness

during surgery require anaesthetic regimens that result in other

and potentially more dangerous adverse effects?45 It is a philo-

sophical question as to whether consciousness without memory

is ethically tenable during surgery, but the clinically relevant

question relates to the potential for postoperative psychological

consequences. Although we have focused on explicit recall in

relationship to conscious experience, there is also the possibility

of implicit (or unconscious) recall. It has been argued that impli-

cit recall of a surgical event—especially involving pain—might

result in PTSD even in the absence of explicit recall.46We support

the opinion that—independently of recall—appropriate anal-

gesia during surgery is of paramount importance given the

known potential for intraoperative awareness. However, it is

less clear whether there is compelling epidemiological evidence

for a negative effect of implicit memory on postoperative psycho-

logical function. Given the high incidence of awareness without

recall (as demonstrated by IFT studies)19—especially at the time

of strong nociceptive stimuli, such as laryngoscopy or surgical

incision—even a small proportion of patients experiencing psy-

chological sequelae as a result of implicit memory would trans-

late to a high absolute number of distressed patients. However,

the number of postoperative patients suffering PTSD without re-

call of surgical events appears to be low. When PTSD is precipi-

tated by perioperative events, the most likely contributing

factors include pain, prolonged intubation, unpleasant experi-

ences in the intensive care unit, physical debility, traumatic ex-

plicit memories, and distressing diagnoses. There is currently

little evidence to suggest that implicit memories are important

contributors. However, the dichotomous determination of PTSD

or not might be less relevant in awareness without recall; subsyn-

dromal PTSD must also be explored in addition to psychological

morbidity (such as mood or anxiety disorders) that cannot neces-

sarily be linked to an index event or experience. As a result of the

ethical implications of this controversy, further data are required.

Controversial: positive responses

to an isolated forearm test reflect

a distinct state of consciousness

A positive and unequivocal response to the command ‘squeeze

my hand’ at the end of a surgical procedure is traditionally

taken to constitute sufficient evidence that consciousness has re-

turned. Likewise, one could argue that a positive and unequivocal

response to the command ‘squeeze my hand’ during a surgical

procedure—for example, a positive IFT response—constitutes

sufficient evidence that consciousness has returned. Until there

is compelling evidence to the contrary, this should be the default

assumption. Sanders and colleagues19have clarified the possibil-

ities of perioperative behaviour and experience with a model of

responsiveness, connected consciousness, and disconnected

consciousness (e.g. a dream state). A recent theoretical perspec-

tive suggests an alternative possibility for IFT responses,

although no data have yet been provided. Pandit 47 48 argues

that the positive IFT response does not signify the full return or

persistence of consciousness but rather a ‘third state’ (referred

to as dysanaesthesia) in which patients can follow a simple com-

mand in the absence of a conscious self (see also Wang and col-

leagues, this issue). It is unclear, of course, whether such a state is

possible and, if so, what the candidate neural correlates would be.

This assertion is provocative but should be tested empirically and/

or potentially situated in broader frameworks of consciousness.49

Controversial: true reports of intraoperative

awareness can be distinguished reliably from

false reports of intraoperative awareness and

from dreaming

Detection of intraoperative awareness is unreliable because it

depends on patient reports rather than objective measures.

i24 | Mashour and Avidan

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

Prospective methods using structured questionnaires detect sub-

stantially more awareness events than approaches based on

spontaneous patient reports. However, a concern regarding the

questions in the Brice questionnaire is that they have not been

psychometrically validated and might have the potential to elicit

false reports or memories.1 15 This latter possibility is consistent

with the finding that a significant proportion of patients only re-

port awareness at later time points after multiple structured inter-

views.2 3 Regardless of the detection method, distinguishing true

from false awareness reports is difficult. Occasionally, a patient re-

port is so detailed and specific in describing intraoperative experi-

ences, events, or discussions that independent arbiters can concur

that awareness definitely occurred.4 28–30

Commonly, however, pa-

tient reports are vague and experts express divergent opinions re-

garding whether or not a patient was truly aware.4 28–30

If many of

the possible awareness reports do represent true awareness, this

would mean that the incidence of intraoperative awareness has

been even higher than studies have suggested. In contrast to pos-

sible awareness experiences, it is important to clarify that most re-

ports of intraoperative dreaming, which were previously viewed as

possible or near awareness experiences, are likely to be unrelated

to intraoperative awareness and do not necessarily indicate that

patients were insufficiently anaesthetized during surgery.50–52

Based on clinical and electroencephalographic evidence, it is pos-

sible that dreaming occurs during emergence from general anaes-

thesia, when patients are sedated or in a physiological sleep

state.50 51 However, Samuelsson and colleagues53 found that,

while the content of dreams was unrelated to awareness, the inci-

dence of intraoperative awareness was 19 times more common

among patients who reported a dream after surgery. Therefore,

the precise relationship between awareness and dreaming re-

mains unresolved.

Conclusion

Substantial progress has been made in understanding the inci-

dence, consequences, and prevention of intraoperative aware-

ness with explicit recall. We are not arguing that further

research is unnecessary in these aspects of the field, but rather

that new studies with disparate results do not necessarily create

‘controversy’ unless the methodology is clearly superior and

results are particularly novel compared with the existing litera-

ture. The truly controversial aspects in this field relate less to

the epidemiology and prevention of awareness and more to the

underlying aetiology (e.g. genetic contribution) and whether

there exist unique states of the brain in association with certain

levels of anaesthesia. These questions may or may not have clear

clinical relevance, but certainly represent some of the most inter-

esting neuroscientific and philosophical dimensions of intrao-

perative awareness.

Authors’ contributions

G.A.M. conceived the project. G.A.M. and M.S.A. wrote the

manuscript.

Declaration of interest

M.S.A. is a member of the Associate Editorial Board of the BJA.

References

1. Brice DD, Hetherington RR, Utting JE. A simple study of aware-

ness and dreaming during anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1970; 42:

535–42

2. Sandin RH, Enlund G, Samuelsson P, Lennmarken C. Aware-

ness during anaesthesia: a prospective case study. Lancet

2000; 355: 707–11

3. Sebel PS, Bowdle TA, Ghoneim MM, et al.The incidence of

awareness during anesthesia: a multicenter United States

study. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 833–9, table of contents

4. Mashour GA, Shanks A, Tremper KK, et al. Prevention of in-

traoperative awareness with explicit recall in an unselected

surgical population: a randomized comparative effectiveness

trial. Anesthesiology 2012; 117: 717–25

5. Errando CL, Sigl JC, Robles M, et al. Awareness with recall dur-

ing general anaesthesia: a prospective observational evalu-

ation of 4001 patients. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101: 178–85

6. Wang Y, Yue Y, Sun YH, et al. Investigation and analysis of

incidence of awareness in patients undergoing cardiac sur-

gery in Beijing, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2005; 118: 1190–4

7. Xu L, Wu AS, Yue Y. The incidence of intra-operative aware-

ness during general anesthesia in China: a multi-center ob-

servational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009; 53: 873–82

8. Ye Z, Guo QL, Zheng H. Investigation and analysis of the inci-

dence of awareness during general anesthesia. Zhong Nan Da

Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2008; 33: 533–6

9. Shi X, Wang DX. The incidence of awareness with recall dur-

ing general anesthesia has been lowered: a historical con-

trolled trial. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013; 93: 3272–5

10. Wang E, Ye Z, Pan Y, et al. Incidence and risk factors of intrao-

perative awareness during general anesthesia. Zhong Nan Da

Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2011; 36: 671–5

11. Pollard RJ, Coyle JP, Gilbert RL, Beck JE. Intraoperative aware-

ness in a regional medical system: a review of 3 years’ data.

Anesthesiology 2007; 106: 269–74

12. Mashour GA, Wang LY, Turner CR, et al. A retrospective study

of intraoperative awareness with methodological implica-

tions. Anesth Analg 2009; 108: 521–6

13. Pandit JJ, Cook TM, Jonker WR, O’Sullivan E. A national survey

of anaesthetists (NAP5 Baseline) to estimate an annual inci-

dence of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia

in the UK. Anaesthesia 2013; 68: 343–53

14. Pandit JJ, Andrade J, Bogod DG, et al. 5th National Audit Project

(NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaesthesia:

summary of main findings and risk factors. Br J Anaesth 2014;

113: 549–59

15. Mashour GA, Kent C, Picton P, et al. Assessment of intraopera-

tive awareness with explicit recall: a comparison of 2 meth-

ods. Anesth Analg 2013; 116: 889–91

16. Pryor KA, Hemmings HC Jr. NAP5: intraoperative awareness

detected, and undetected. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113: 530–3

17. Tunstall ME, Sheikh A. Comparison of 1.5% enflurane with

1.25% isoflurane in oxygen for caesarean section: avoidance

of awareness without nitrous oxide. Br J Anaesth 1989;62:

138–43

18. King H, Ashley S, Brathwaite D, Decayette J, Wooten DJ. Ad-

equacy of general anesthesia for cesarean section. Anesth

Analg 1993; 77: 84–8

19. Sanders RD, Tononi G, Laureys S, Sleigh JW. Unresponsive-

ness ≠ unconsciousness. Anesthesiology 2012; 116: 946–59

20. Meyer BC, Blacher RS. A traumatic neurotic reaction

induced by succinylcholine chloride. N Y State J Med 1961;

61: 1255–61

21. Lennmarken C, Bildfors K, Enlund G, Samuelsson P, Sandin R.

Victims of awareness.Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002; 46: 229–31

22. Leslie K, Chan MT, Myles PS, Forbes A, McCulloch TJ. Post-

traumatic stress disorder in aware patients from the

B-aware trial. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 823–8

Intraoperative awareness: controversies and non-controversies| i25

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

stantially more awareness events than approaches based on

spontaneous patient reports. However, a concern regarding the

questions in the Brice questionnaire is that they have not been

psychometrically validated and might have the potential to elicit

false reports or memories.1 15 This latter possibility is consistent

with the finding that a significant proportion of patients only re-

port awareness at later time points after multiple structured inter-

views.2 3 Regardless of the detection method, distinguishing true

from false awareness reports is difficult. Occasionally, a patient re-

port is so detailed and specific in describing intraoperative experi-

ences, events, or discussions that independent arbiters can concur

that awareness definitely occurred.4 28–30

Commonly, however, pa-

tient reports are vague and experts express divergent opinions re-

garding whether or not a patient was truly aware.4 28–30

If many of

the possible awareness reports do represent true awareness, this

would mean that the incidence of intraoperative awareness has

been even higher than studies have suggested. In contrast to pos-

sible awareness experiences, it is important to clarify that most re-

ports of intraoperative dreaming, which were previously viewed as

possible or near awareness experiences, are likely to be unrelated

to intraoperative awareness and do not necessarily indicate that

patients were insufficiently anaesthetized during surgery.50–52

Based on clinical and electroencephalographic evidence, it is pos-

sible that dreaming occurs during emergence from general anaes-

thesia, when patients are sedated or in a physiological sleep

state.50 51 However, Samuelsson and colleagues53 found that,

while the content of dreams was unrelated to awareness, the inci-

dence of intraoperative awareness was 19 times more common

among patients who reported a dream after surgery. Therefore,

the precise relationship between awareness and dreaming re-

mains unresolved.

Conclusion

Substantial progress has been made in understanding the inci-

dence, consequences, and prevention of intraoperative aware-

ness with explicit recall. We are not arguing that further

research is unnecessary in these aspects of the field, but rather

that new studies with disparate results do not necessarily create

‘controversy’ unless the methodology is clearly superior and

results are particularly novel compared with the existing litera-

ture. The truly controversial aspects in this field relate less to

the epidemiology and prevention of awareness and more to the

underlying aetiology (e.g. genetic contribution) and whether

there exist unique states of the brain in association with certain

levels of anaesthesia. These questions may or may not have clear

clinical relevance, but certainly represent some of the most inter-

esting neuroscientific and philosophical dimensions of intrao-

perative awareness.

Authors’ contributions

G.A.M. conceived the project. G.A.M. and M.S.A. wrote the

manuscript.

Declaration of interest

M.S.A. is a member of the Associate Editorial Board of the BJA.

References

1. Brice DD, Hetherington RR, Utting JE. A simple study of aware-

ness and dreaming during anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 1970; 42:

535–42

2. Sandin RH, Enlund G, Samuelsson P, Lennmarken C. Aware-

ness during anaesthesia: a prospective case study. Lancet

2000; 355: 707–11

3. Sebel PS, Bowdle TA, Ghoneim MM, et al.The incidence of

awareness during anesthesia: a multicenter United States

study. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 833–9, table of contents

4. Mashour GA, Shanks A, Tremper KK, et al. Prevention of in-

traoperative awareness with explicit recall in an unselected

surgical population: a randomized comparative effectiveness

trial. Anesthesiology 2012; 117: 717–25

5. Errando CL, Sigl JC, Robles M, et al. Awareness with recall dur-

ing general anaesthesia: a prospective observational evalu-

ation of 4001 patients. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101: 178–85

6. Wang Y, Yue Y, Sun YH, et al. Investigation and analysis of

incidence of awareness in patients undergoing cardiac sur-

gery in Beijing, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2005; 118: 1190–4

7. Xu L, Wu AS, Yue Y. The incidence of intra-operative aware-

ness during general anesthesia in China: a multi-center ob-

servational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009; 53: 873–82

8. Ye Z, Guo QL, Zheng H. Investigation and analysis of the inci-

dence of awareness during general anesthesia. Zhong Nan Da

Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2008; 33: 533–6

9. Shi X, Wang DX. The incidence of awareness with recall dur-

ing general anesthesia has been lowered: a historical con-

trolled trial. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013; 93: 3272–5

10. Wang E, Ye Z, Pan Y, et al. Incidence and risk factors of intrao-

perative awareness during general anesthesia. Zhong Nan Da

Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2011; 36: 671–5

11. Pollard RJ, Coyle JP, Gilbert RL, Beck JE. Intraoperative aware-

ness in a regional medical system: a review of 3 years’ data.

Anesthesiology 2007; 106: 269–74

12. Mashour GA, Wang LY, Turner CR, et al. A retrospective study

of intraoperative awareness with methodological implica-

tions. Anesth Analg 2009; 108: 521–6

13. Pandit JJ, Cook TM, Jonker WR, O’Sullivan E. A national survey

of anaesthetists (NAP5 Baseline) to estimate an annual inci-

dence of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia

in the UK. Anaesthesia 2013; 68: 343–53

14. Pandit JJ, Andrade J, Bogod DG, et al. 5th National Audit Project

(NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaesthesia:

summary of main findings and risk factors. Br J Anaesth 2014;

113: 549–59

15. Mashour GA, Kent C, Picton P, et al. Assessment of intraopera-

tive awareness with explicit recall: a comparison of 2 meth-

ods. Anesth Analg 2013; 116: 889–91

16. Pryor KA, Hemmings HC Jr. NAP5: intraoperative awareness

detected, and undetected. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113: 530–3

17. Tunstall ME, Sheikh A. Comparison of 1.5% enflurane with

1.25% isoflurane in oxygen for caesarean section: avoidance

of awareness without nitrous oxide. Br J Anaesth 1989;62:

138–43

18. King H, Ashley S, Brathwaite D, Decayette J, Wooten DJ. Ad-

equacy of general anesthesia for cesarean section. Anesth

Analg 1993; 77: 84–8

19. Sanders RD, Tononi G, Laureys S, Sleigh JW. Unresponsive-

ness ≠ unconsciousness. Anesthesiology 2012; 116: 946–59

20. Meyer BC, Blacher RS. A traumatic neurotic reaction

induced by succinylcholine chloride. N Y State J Med 1961;

61: 1255–61

21. Lennmarken C, Bildfors K, Enlund G, Samuelsson P, Sandin R.

Victims of awareness.Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002; 46: 229–31

22. Leslie K, Chan MT, Myles PS, Forbes A, McCulloch TJ. Post-

traumatic stress disorder in aware patients from the

B-aware trial. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 823–8

Intraoperative awareness: controversies and non-controversies| i25

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

23. Domino KB, Posner KL, Caplan RA, Cheney FW. Awareness

during anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology

1999; 90: 1053–61

24. Samuelsson P, Brudin L, Sandin RH. Late psychological symp-

toms after awareness among consecutively included surgical

patients. Anesthesiology 2007; 106: 26–32

25. Laukkala T, Ranta S, Wennervirta J, et al. Long-term psycho-

social outcomes after intraoperative awareness with recall.

Anesth Analg 2014; 119: 86–92

26. Whitlock E, Rodebaugh T, Hassett A, et al. Psychological se-

quelae of surgery in a prospective cohort of patients from

three intraoperative awareness prevention trials. Anesth

Analg 2015; 120: 87–95

27. Cook TM, Andrade J, Bogod DG, et al. 5th National Audit Pro-

ject (NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaes-

thesia: patient experiences, human factors, sedation,

consent, and medicolegal issues. Br J Anaesth 2014;113:

560–74

28. Myles PS, Leslie K, McNeil J, Forbes A, Chan MT. Bispectral

index monitoring to prevent awareness during anaesthesia:

the B-Aware randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:

1757–63

29. Avidan MS, Jacobsohn E, Glick D, et al. Prevention of intrao-

perative awareness in a high-risk surgical population. N

Engl J Med 2011; 365: 591–600

30. Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al. Anesthesia awareness

and the bispectral index. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1097–108

31. Zhang C, Xu L, Ma YQ, et al. Bispectral index monitoring

prevent awareness during total intravenous anesthesia: a

prospective, randomized, double-blinded, multi-center con-

trolled trial. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011; 124: 3664–9

32. Avidan MS, Mashour GA. Prevention of intraoperative aware-

ness with explicit recall: making sense of the evidence.

Anesthesiology 2013; 118: 449–56

33. Punjasawadwong Y, Phongchiewboon A, Bunchungmongkol N.

Bispectral index for improving anaesthetic delivery and post-

operative recovery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;6: CD003843

34. Bigelow H. Insensibility during surgical operations produced

by inhalation. The Boston Medicaland SurgicalJournal 1846;

XXXV: 309–17

35. Gray TC. A system of anaesthesia using d-tubocurarine chlor-

ide for chest surgery. Postgrad Med J 1948; 24: 514–26

36. Ghoneim MM, Block RI, Haffarnan M, Mathews MJ. Awareness

during anesthesia: risk factors, causes and sequelae: a review

of reported cases in the literature. Anesth Analg 2009;108:

527–35

37. Nickalls RW, Mahajan RP. Awareness and anaesthesia: think

dose, think data. Br J Anaesth 2010; 104: 1–2

38. Cheng VY, Martin LJ, Elliott EM, et al. α5GABAA receptors me-

diate the amnestic but not sedative-hypnotic effects of the

general anesthetic etomidate. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 3713–20

39. Kretschmannova K, Hines RM, Revilla-Sanchez R, et al.

Enhanced tonic inhibition influences the hypnotic and am-

nestic actions of the intravenous anesthetics etomidate and

propofol. J Neurosci 2013; 33: 7264–73

40. Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, et al. General anesthetic actions

in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the

GABAA receptor β3 subunit. FASEB J 2003; 17: 250–2

41. Zeller A, Arras M, Jurd R, Rudolph U. Mapping the contribu-

tion of β3-containing GABAA receptors to volatile and intra-

venous general anesthetic actions. BMC Pharmacol 2007; 7: 2

42. Aranake A, Gradwohl S, Ben-Abdallah A, et al. Increased risk

of intraoperative awareness in patients with a history of

awareness. Anesthesiology 2013; 119: 1275–83

43. Esaki RK, Mashour GA. Levels of consciousness during re-

gional anesthesia and monitored anesthesia care: patient

expectations and experiences. Anesth Analg 2009; 108:

1560–3

44. Kent CD, Mashour GA, Metzger NA, Posner KL, Domino KB.

Psychological impact of unexpected explicit recall of events

occurring during surgery performed under sedation, regional

anaesthesia, and general anaesthesia: data from the Anes-

thesia Awareness Registry. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110: 381–7

45. Crosby G. General anesthesia — minding the mind during

surgery. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 660–1

46. Wang M, Messina AG, Russell IF. The topography of aware-

ness: a classification of intra-operative cognitive states.

Anaesthesia 2012; 67: 1197–201

47. Pandit JJ. Isolated forearm – or isolated brain? Interpreting re-

sponses during anaesthesia – or ‘dysanaesthesia’. Anaesthesia

2013; 68: 995–1000

48. Pandit JJ. Acceptably aware during general anaesthesia:

‘dysanaesthesia’ – the uncoupling of perception from sen-

sory inputs. Conscious Cogn 2014; 27: 194–212

49. Oizumi M, Albantakis L, Tononi G. From the phenomenology

to the mechanisms of consciousness: Integrated Information

Theory 3.0. PLoS Comput Biol 2014; 10: e1003588

50. Leslie K, Skrzypek H, Paech MJ, Kurowski I, Whybrow T.

Dreaming during anesthesia and anesthetic depth in elective

surgery patients: a prospective cohort study. Anesthesiology

2007; 106: 33–42

51. Leslie K, Sleigh J, Paech MJ, et al. Dreaming and electroence-

phalographic changes during anesthesia maintained with

propofol or desflurane. Anesthesiology 2009; 111: 547–55

52. Samuelsson P, Brudin L, Sandin RH. BIS does not predict

dreams reported after anaesthesia.Acta Anaesthesiol Scand

2008; 52: 810–4

53. Samuelsson P, Brudin L, Sandin RH. Intraoperative dreams

reported after general anaesthesia are not early interpre-

tations of delayed awareness. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand

2008; 52: 805–9

Handling editor: H. C. Hemmings

i26 | Mashour and Avidan

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bja/article-abstract/115/suppl_1/i20/233608 by KERIS National Access user on 20 January 2020

during anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology

1999; 90: 1053–61

24. Samuelsson P, Brudin L, Sandin RH. Late psychological symp-

toms after awareness among consecutively included surgical

patients. Anesthesiology 2007; 106: 26–32

25. Laukkala T, Ranta S, Wennervirta J, et al. Long-term psycho-

social outcomes after intraoperative awareness with recall.

Anesth Analg 2014; 119: 86–92

26. Whitlock E, Rodebaugh T, Hassett A, et al. Psychological se-

quelae of surgery in a prospective cohort of patients from

three intraoperative awareness prevention trials. Anesth

Analg 2015; 120: 87–95

27. Cook TM, Andrade J, Bogod DG, et al. 5th National Audit Pro-

ject (NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaes-

thesia: patient experiences, human factors, sedation,

consent, and medicolegal issues. Br J Anaesth 2014;113:

560–74

28. Myles PS, Leslie K, McNeil J, Forbes A, Chan MT. Bispectral

index monitoring to prevent awareness during anaesthesia:

the B-Aware randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:

1757–63

29. Avidan MS, Jacobsohn E, Glick D, et al. Prevention of intrao-

perative awareness in a high-risk surgical population. N

Engl J Med 2011; 365: 591–600

30. Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al. Anesthesia awareness

and the bispectral index. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1097–108

31. Zhang C, Xu L, Ma YQ, et al. Bispectral index monitoring

prevent awareness during total intravenous anesthesia: a

prospective, randomized, double-blinded, multi-center con-

trolled trial. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011; 124: 3664–9

32. Avidan MS, Mashour GA. Prevention of intraoperative aware-

ness with explicit recall: making sense of the evidence.

Anesthesiology 2013; 118: 449–56

33. Punjasawadwong Y, Phongchiewboon A, Bunchungmongkol N.

Bispectral index for improving anaesthetic delivery and post-