Fundamentals of Inventory Management: A Detailed Overview

VerifiedAdded on 2019/09/30

|26

|11025

|134

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of inventory management, beginning with a definition of inventory and the reasons for maintaining it, such as meeting demand, keeping operations running, managing lead times, hedging against price increases, and taking advantage of quantity discounts. It then delves into inventory control methods, including the ABC approach and cycle counting, which help firms manage large numbers of inventory items efficiently. The report also addresses the critical aspect of balancing inventory levels with costs, detailing the three main types of costs: holding costs, set-up costs, and purchasing costs. Holding costs include storage, personnel, taxes, and obsolescence, while set-up costs involve preparing machines for production or order costs for purchased items. Purchasing costs are simply the cost of the items themselves. By understanding these costs and applying effective control methods, firms can optimize their inventory management strategies to minimize expenses and ensure adequate supply.

Inventory Management

Inventory management, or inventory control, is an attempt to balance inventory needs and

requirements with the need to minimize costs resulting from obtaining and holding inventory.

There are several schools of thought that view inventory and its function differently. These will

be addressed later, but first we present a foundation to facilitate the reader's understanding of

inventory and its function.

WHAT IS INVENTORY?

Inventory is a quantity or store of goods that is held for some purpose or use (the term may also

be used as a verb, meaning to take inventory or to count all goods held in inventory). Inventory

may be kept “in-house,” meaning on the premises or nearby for immediate use; or it may be held

in a distant warehouse or distribution center for future use. With the exception of firms utilizing

just-in-time methods, the term “inventory” typically implies a stored quantity of goods that

exceeds what is needed for the firm to function at the current time (e.g., within the next few

hours).

WHY KEEP INVENTORY?

Why would a firm hold more inventory than is currently necessary to ensure the firm's

operation? The following is a list of reasons for maintaining what would appear to be “excess”

inventory.

Meet Demand. In order for a retailer to stay in business, it must have the products that the

customer wants on hand when the customer wants them. If not, the retailer will have to back-

order the product. If the customer can get the good from some other source, he or she may

choose to do so rather than electing to allow the original retailer to meet demand later (through

back-order). Hence, in many instances, if a good is not in inventory, a sale is lost forever.

Keep Operations Running. A manufacturer must have certain purchased items (raw materials,

components, or subassemblies) in order to manufacture its product. Running out of only one item

can prevent a manufacturer from completing the production of its finished goods.

Inventory between successive dependent operations also serves to decouple the dependency of

the operations. A machine or workcenter is often dependent upon the previous operation to

provide it with parts to work on. If work ceases at a workcenter, then all subsequent centers will

shut down for lack of work. If a supply of work-in-process inventory is kept between each

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 1

Inventory management, or inventory control, is an attempt to balance inventory needs and

requirements with the need to minimize costs resulting from obtaining and holding inventory.

There are several schools of thought that view inventory and its function differently. These will

be addressed later, but first we present a foundation to facilitate the reader's understanding of

inventory and its function.

WHAT IS INVENTORY?

Inventory is a quantity or store of goods that is held for some purpose or use (the term may also

be used as a verb, meaning to take inventory or to count all goods held in inventory). Inventory

may be kept “in-house,” meaning on the premises or nearby for immediate use; or it may be held

in a distant warehouse or distribution center for future use. With the exception of firms utilizing

just-in-time methods, the term “inventory” typically implies a stored quantity of goods that

exceeds what is needed for the firm to function at the current time (e.g., within the next few

hours).

WHY KEEP INVENTORY?

Why would a firm hold more inventory than is currently necessary to ensure the firm's

operation? The following is a list of reasons for maintaining what would appear to be “excess”

inventory.

Meet Demand. In order for a retailer to stay in business, it must have the products that the

customer wants on hand when the customer wants them. If not, the retailer will have to back-

order the product. If the customer can get the good from some other source, he or she may

choose to do so rather than electing to allow the original retailer to meet demand later (through

back-order). Hence, in many instances, if a good is not in inventory, a sale is lost forever.

Keep Operations Running. A manufacturer must have certain purchased items (raw materials,

components, or subassemblies) in order to manufacture its product. Running out of only one item

can prevent a manufacturer from completing the production of its finished goods.

Inventory between successive dependent operations also serves to decouple the dependency of

the operations. A machine or workcenter is often dependent upon the previous operation to

provide it with parts to work on. If work ceases at a workcenter, then all subsequent centers will

shut down for lack of work. If a supply of work-in-process inventory is kept between each

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 1

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

workcenter, then each machine can maintain its operations for a limited time, hopefully until

operations resume at the original center.

Lead Time. Lead time is the time that elapses between the placing of an order (either a purchase

order or a production order issued to the shop or the factory floor) and actually receiving the

goods ordered.

If a supplier (an external firm or an internal department or plant) cannot supply the required

goods on demand, then the client firm must keep an inventory of the needed goods. The longer

the lead time, the larger the quantity of goods the firm must carry in inventory.

A just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing firm, such as Nissan in Smyrna, Tennessee, can maintain

extremely low levels of inventory. Nissan takes delivery on truck seats as many as 18 times per

day. However, steel mills may have a lead time of up to three months. That means that a firm

that uses steel produced at the mill must place orders at least three months in advance of their

need. In order to keep their operations running in the meantime, an on-hand inventory of three

months' steel requirements would be necessary.

Hedge. Inventory can also be used as a hedge against price increases and inflation. Salesmen

routinely call purchasing agents shortly before a price increase goes into effect. This gives the

buyer a chance to purchase material, in excess of current need, at a price that is lower than it

would be if the buyer waited until after the price increase occurs.

Quantity Discount. Often firms are given a price discount when purchasing large quantities of a

good. This also frequently results in inventory in excess of what is currently needed to meet

demand. However, if the discount is sufficient to offset the extra holding cost incurred as a result

of the excess inventory, the decision to buy the large quantity is justified.

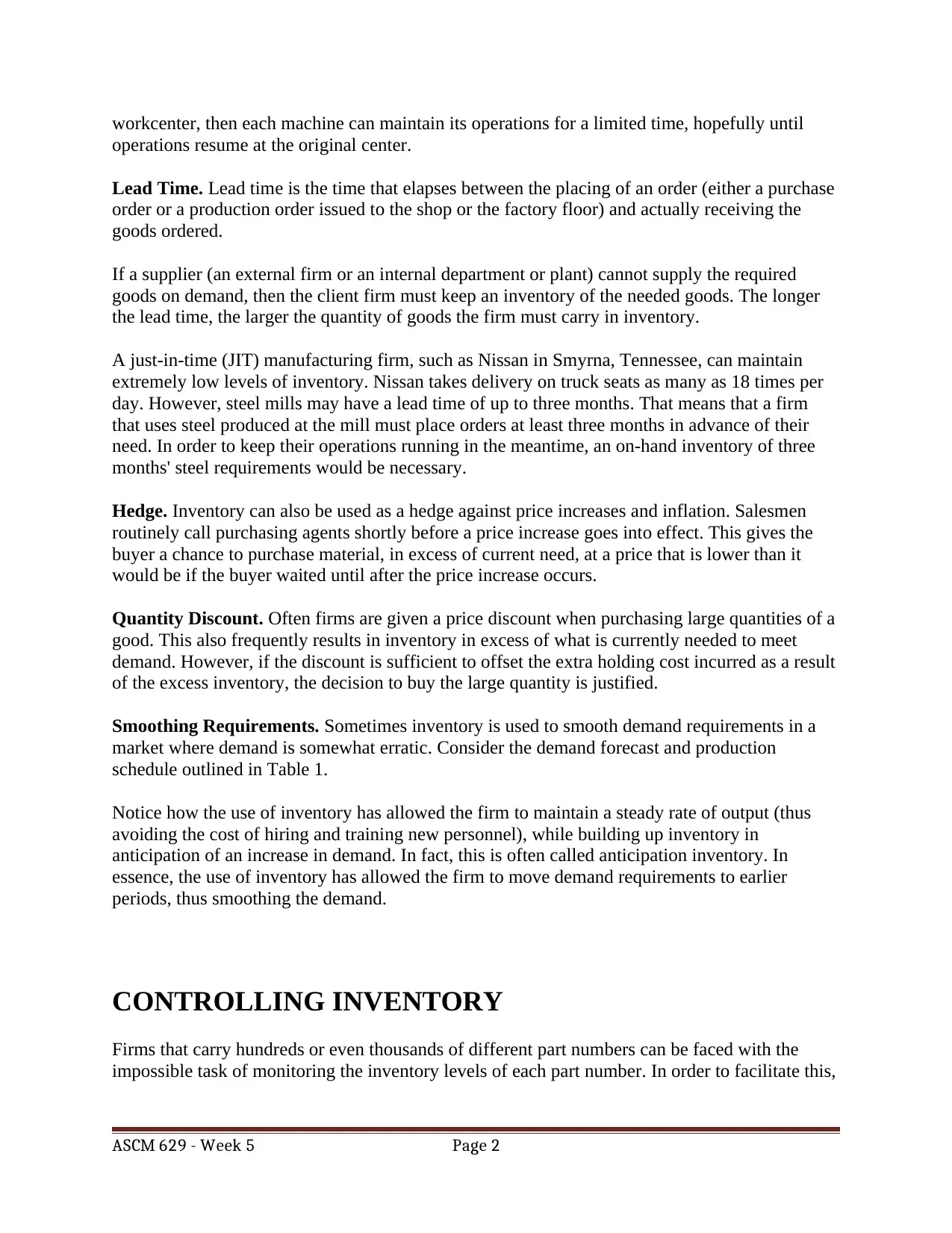

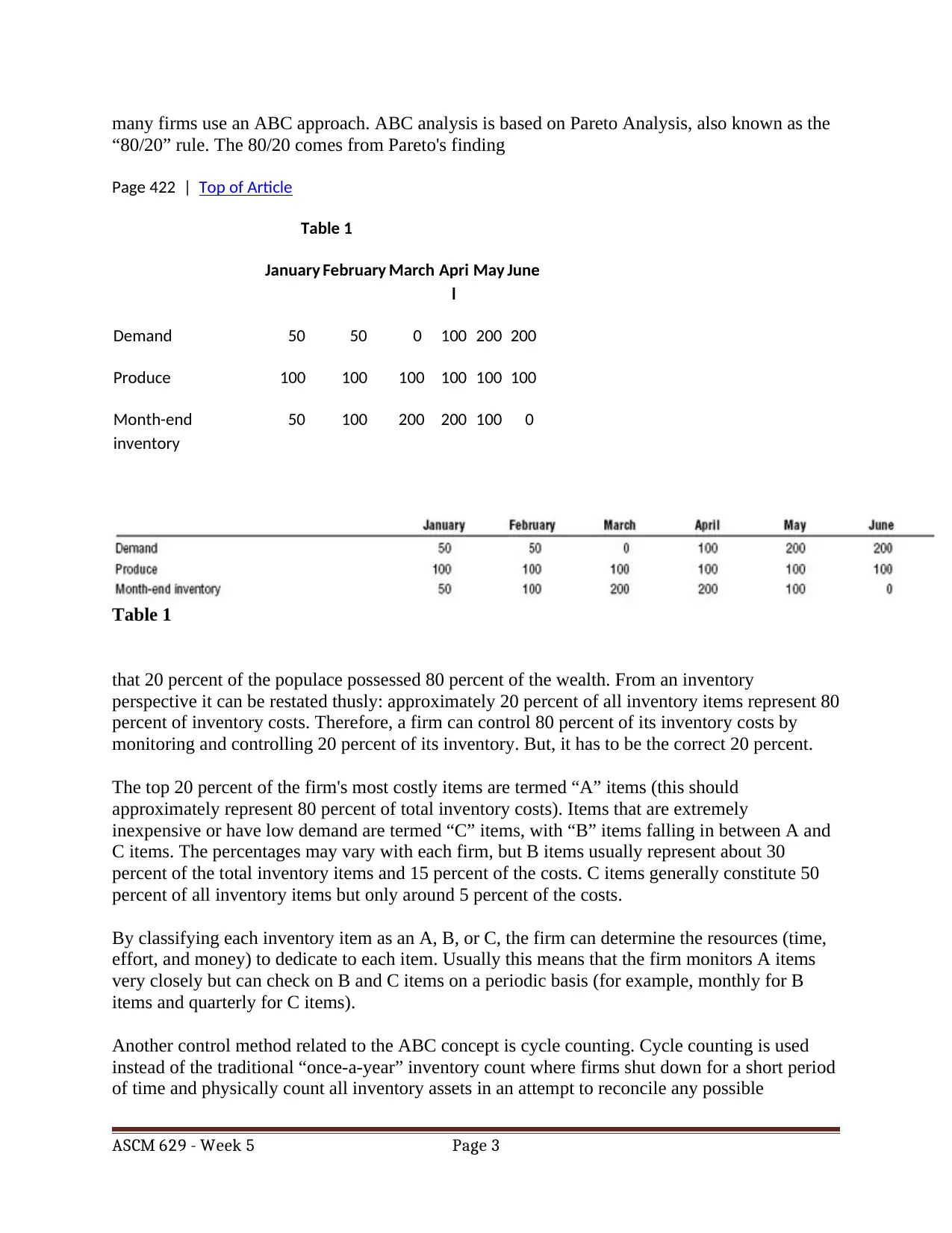

Smoothing Requirements. Sometimes inventory is used to smooth demand requirements in a

market where demand is somewhat erratic. Consider the demand forecast and production

schedule outlined in Table 1.

Notice how the use of inventory has allowed the firm to maintain a steady rate of output (thus

avoiding the cost of hiring and training new personnel), while building up inventory in

anticipation of an increase in demand. In fact, this is often called anticipation inventory. In

essence, the use of inventory has allowed the firm to move demand requirements to earlier

periods, thus smoothing the demand.

CONTROLLING INVENTORY

Firms that carry hundreds or even thousands of different part numbers can be faced with the

impossible task of monitoring the inventory levels of each part number. In order to facilitate this,

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 2

operations resume at the original center.

Lead Time. Lead time is the time that elapses between the placing of an order (either a purchase

order or a production order issued to the shop or the factory floor) and actually receiving the

goods ordered.

If a supplier (an external firm or an internal department or plant) cannot supply the required

goods on demand, then the client firm must keep an inventory of the needed goods. The longer

the lead time, the larger the quantity of goods the firm must carry in inventory.

A just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing firm, such as Nissan in Smyrna, Tennessee, can maintain

extremely low levels of inventory. Nissan takes delivery on truck seats as many as 18 times per

day. However, steel mills may have a lead time of up to three months. That means that a firm

that uses steel produced at the mill must place orders at least three months in advance of their

need. In order to keep their operations running in the meantime, an on-hand inventory of three

months' steel requirements would be necessary.

Hedge. Inventory can also be used as a hedge against price increases and inflation. Salesmen

routinely call purchasing agents shortly before a price increase goes into effect. This gives the

buyer a chance to purchase material, in excess of current need, at a price that is lower than it

would be if the buyer waited until after the price increase occurs.

Quantity Discount. Often firms are given a price discount when purchasing large quantities of a

good. This also frequently results in inventory in excess of what is currently needed to meet

demand. However, if the discount is sufficient to offset the extra holding cost incurred as a result

of the excess inventory, the decision to buy the large quantity is justified.

Smoothing Requirements. Sometimes inventory is used to smooth demand requirements in a

market where demand is somewhat erratic. Consider the demand forecast and production

schedule outlined in Table 1.

Notice how the use of inventory has allowed the firm to maintain a steady rate of output (thus

avoiding the cost of hiring and training new personnel), while building up inventory in

anticipation of an increase in demand. In fact, this is often called anticipation inventory. In

essence, the use of inventory has allowed the firm to move demand requirements to earlier

periods, thus smoothing the demand.

CONTROLLING INVENTORY

Firms that carry hundreds or even thousands of different part numbers can be faced with the

impossible task of monitoring the inventory levels of each part number. In order to facilitate this,

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 2

many firms use an ABC approach. ABC analysis is based on Pareto Analysis, also known as the

“80/20” rule. The 80/20 comes from Pareto's finding

Page 422 | Top of Article

Table 1

January February March Apri

l

May June

Demand 50 50 0 100 200 200

Produce 100 100 100 100 100 100

Month-end

inventory

50 100 200 200 100 0

Table 1

that 20 percent of the populace possessed 80 percent of the wealth. From an inventory

perspective it can be restated thusly: approximately 20 percent of all inventory items represent 80

percent of inventory costs. Therefore, a firm can control 80 percent of its inventory costs by

monitoring and controlling 20 percent of its inventory. But, it has to be the correct 20 percent.

The top 20 percent of the firm's most costly items are termed “A” items (this should

approximately represent 80 percent of total inventory costs). Items that are extremely

inexpensive or have low demand are termed “C” items, with “B” items falling in between A and

C items. The percentages may vary with each firm, but B items usually represent about 30

percent of the total inventory items and 15 percent of the costs. C items generally constitute 50

percent of all inventory items but only around 5 percent of the costs.

By classifying each inventory item as an A, B, or C, the firm can determine the resources (time,

effort, and money) to dedicate to each item. Usually this means that the firm monitors A items

very closely but can check on B and C items on a periodic basis (for example, monthly for B

items and quarterly for C items).

Another control method related to the ABC concept is cycle counting. Cycle counting is used

instead of the traditional “once-a-year” inventory count where firms shut down for a short period

of time and physically count all inventory assets in an attempt to reconcile any possible

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 3

“80/20” rule. The 80/20 comes from Pareto's finding

Page 422 | Top of Article

Table 1

January February March Apri

l

May June

Demand 50 50 0 100 200 200

Produce 100 100 100 100 100 100

Month-end

inventory

50 100 200 200 100 0

Table 1

that 20 percent of the populace possessed 80 percent of the wealth. From an inventory

perspective it can be restated thusly: approximately 20 percent of all inventory items represent 80

percent of inventory costs. Therefore, a firm can control 80 percent of its inventory costs by

monitoring and controlling 20 percent of its inventory. But, it has to be the correct 20 percent.

The top 20 percent of the firm's most costly items are termed “A” items (this should

approximately represent 80 percent of total inventory costs). Items that are extremely

inexpensive or have low demand are termed “C” items, with “B” items falling in between A and

C items. The percentages may vary with each firm, but B items usually represent about 30

percent of the total inventory items and 15 percent of the costs. C items generally constitute 50

percent of all inventory items but only around 5 percent of the costs.

By classifying each inventory item as an A, B, or C, the firm can determine the resources (time,

effort, and money) to dedicate to each item. Usually this means that the firm monitors A items

very closely but can check on B and C items on a periodic basis (for example, monthly for B

items and quarterly for C items).

Another control method related to the ABC concept is cycle counting. Cycle counting is used

instead of the traditional “once-a-year” inventory count where firms shut down for a short period

of time and physically count all inventory assets in an attempt to reconcile any possible

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 3

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

discrepancies in their inventory records. When cycle counting is used the firm is continually

taking a physical count but not of total inventory.

A firm may physically count a certain section of the plant or warehouse, moving on to other

sections upon completion, until the entire facility is counted. Then the process starts all over

again.

The firm may also choose to count all the A items, then the B items, and finally the C items.

Certainly, the counting frequency will vary with the classification of each item. In other words,

A items may be counted monthly, B items quarterly, and C items yearly. In addition, the required

accuracy of inventory records may vary according to classification, with A items requiring the

most accurate record keeping.

BALANCING INVENTORYAND COSTS

As stated earlier, inventory management is an attempt to maintain an adequate supply of goods

while minimizing inventory costs. We saw a variety of reasons companies hold inventory and

these reasons dictate what is deemed to be an adequate supply of inventory. Now, how do we

balance this supply with its costs? First let's look at what kind of costs we are talking about.

There are three types of costs that together constitute total inventory costs: holding costs, set-up

costs, and purchasing costs.

Holding costs. Holding costs, also called carrying costs, are the costs that result from

maintaining the inventory. Inventory in excess of current demand frequently means that its

holder must provide a place for its storage when not in use. This could range from a small

storage area near the production line to a huge warehouse or distribution center. A storage

facility requires personnel to move the inventory when needed and to keep track of what is stored

and where it is stored. If the inventory is heavy or bulky, forklifts may be necessary to move it

around.

Storage facilities also require heating, cooling, lighting, and water. The firm must pay taxes on

the inventory, and opportunity costs occur from the lost use of the funds that were spent on the

inventory. Also, obsolescence, pilferage (theft), and shrinkage are problems. All of these things

add cost to holding or carrying inventory.

If the firm can determine the cost of holding one unit of inventory for one year (H) it can

determine its annual holding cost by multiplying the cost of holding one unit by the average

inventory held for a one-year period. Average inventory can be computed by dividing the

amount of goods that are ordered every time an order is placed (Q) by two. Thus, average

inventory is expressed as Q/2. Annual holding cost, then, can be expressed as H(Q/2).

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 4

taking a physical count but not of total inventory.

A firm may physically count a certain section of the plant or warehouse, moving on to other

sections upon completion, until the entire facility is counted. Then the process starts all over

again.

The firm may also choose to count all the A items, then the B items, and finally the C items.

Certainly, the counting frequency will vary with the classification of each item. In other words,

A items may be counted monthly, B items quarterly, and C items yearly. In addition, the required

accuracy of inventory records may vary according to classification, with A items requiring the

most accurate record keeping.

BALANCING INVENTORYAND COSTS

As stated earlier, inventory management is an attempt to maintain an adequate supply of goods

while minimizing inventory costs. We saw a variety of reasons companies hold inventory and

these reasons dictate what is deemed to be an adequate supply of inventory. Now, how do we

balance this supply with its costs? First let's look at what kind of costs we are talking about.

There are three types of costs that together constitute total inventory costs: holding costs, set-up

costs, and purchasing costs.

Holding costs. Holding costs, also called carrying costs, are the costs that result from

maintaining the inventory. Inventory in excess of current demand frequently means that its

holder must provide a place for its storage when not in use. This could range from a small

storage area near the production line to a huge warehouse or distribution center. A storage

facility requires personnel to move the inventory when needed and to keep track of what is stored

and where it is stored. If the inventory is heavy or bulky, forklifts may be necessary to move it

around.

Storage facilities also require heating, cooling, lighting, and water. The firm must pay taxes on

the inventory, and opportunity costs occur from the lost use of the funds that were spent on the

inventory. Also, obsolescence, pilferage (theft), and shrinkage are problems. All of these things

add cost to holding or carrying inventory.

If the firm can determine the cost of holding one unit of inventory for one year (H) it can

determine its annual holding cost by multiplying the cost of holding one unit by the average

inventory held for a one-year period. Average inventory can be computed by dividing the

amount of goods that are ordered every time an order is placed (Q) by two. Thus, average

inventory is expressed as Q/2. Annual holding cost, then, can be expressed as H(Q/2).

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 4

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Set-up costs. Set-up costs are the costs incurred from getting a machine ready to produce the

desired good. In a manufacturing setting this would require the use of a skilled technician (a

cost) who disassembles the tooling that is currently in use on the machine. The disassembled

tooling is then taken to a tool room or tool shop for maintenance or possible repair (another cost).

The technician then takes the currently needed tooling from the tool room (where it has been

maintained; another cost) and brings it to the machine in question.

There the technician has to assemble the tooling on the machine in the manner required for the

good to be produced. (This is known as a “set-up.”) Then the technician has to calibrate the

machine and probably will run a number of parts, that will have to be scrapped (a cost), in order

to get the machine correctly calibrated and running. All the while the machine has been idle and

not producing any parts (opportunity cost). As one can see, there is considerable cost involved in

set-up.

If the firm purchases the part or raw material, then an order cost, rather than a set-up cost, is

incurred. Ordering costs include the purchasing agent's salary and travel/entertainment budget,

administrative and secretarial support, office space, copiers and office supplies, forms and

documents, long-distance telephone bills, and computer systems and support. Also, some firms

include the cost of shipping the purchased goods in the order cost.

If the firm can determine the cost of one set-up (S) or one order, it can determine its annual

setup/order cost by multiplying the cost of one set-up by the number of set-ups made or orders

placed annually. Suppose a firm has an annual demand (D) of 1,000 units. If the firm orders 100

units (Q) every time it places an order, the firm will obviously place 10 orders per year (D/Q).

Hence, annual set-up/order cost can be expressed as S(D/Q).

Purchasing cost. Purchasing cost is simply the cost of the purchased item itself. If the firm

purchases a part that goes into its finished product, the firm can determine its annual purchasing

cost by multiplying the cost of one purchased unit (P) by the number of finished products

demanded in a year (D). Hence, purchasing cost is expressed as PD.

Now total inventory cost can be expressed as:

Total = Holding cost + Set-up/Order cost + Purchasing cost

or

Total = H(Q/2) + S(D/Q) + PD

If holding costs and set-up costs were plotted as lines on a graph, the point at which they

intersect (that is, the point at which they are equal) would indicate the lowest total inventory cost.

Therefore, if we want to minimize total inventory cost, every time we place an order, we should

order the quantity (Q) that corresponds to the point where the two values are equal. If we set the

two costs equal and solve forQ we get:

H(Q/2) = S(D/Q)

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 5

desired good. In a manufacturing setting this would require the use of a skilled technician (a

cost) who disassembles the tooling that is currently in use on the machine. The disassembled

tooling is then taken to a tool room or tool shop for maintenance or possible repair (another cost).

The technician then takes the currently needed tooling from the tool room (where it has been

maintained; another cost) and brings it to the machine in question.

There the technician has to assemble the tooling on the machine in the manner required for the

good to be produced. (This is known as a “set-up.”) Then the technician has to calibrate the

machine and probably will run a number of parts, that will have to be scrapped (a cost), in order

to get the machine correctly calibrated and running. All the while the machine has been idle and

not producing any parts (opportunity cost). As one can see, there is considerable cost involved in

set-up.

If the firm purchases the part or raw material, then an order cost, rather than a set-up cost, is

incurred. Ordering costs include the purchasing agent's salary and travel/entertainment budget,

administrative and secretarial support, office space, copiers and office supplies, forms and

documents, long-distance telephone bills, and computer systems and support. Also, some firms

include the cost of shipping the purchased goods in the order cost.

If the firm can determine the cost of one set-up (S) or one order, it can determine its annual

setup/order cost by multiplying the cost of one set-up by the number of set-ups made or orders

placed annually. Suppose a firm has an annual demand (D) of 1,000 units. If the firm orders 100

units (Q) every time it places an order, the firm will obviously place 10 orders per year (D/Q).

Hence, annual set-up/order cost can be expressed as S(D/Q).

Purchasing cost. Purchasing cost is simply the cost of the purchased item itself. If the firm

purchases a part that goes into its finished product, the firm can determine its annual purchasing

cost by multiplying the cost of one purchased unit (P) by the number of finished products

demanded in a year (D). Hence, purchasing cost is expressed as PD.

Now total inventory cost can be expressed as:

Total = Holding cost + Set-up/Order cost + Purchasing cost

or

Total = H(Q/2) + S(D/Q) + PD

If holding costs and set-up costs were plotted as lines on a graph, the point at which they

intersect (that is, the point at which they are equal) would indicate the lowest total inventory cost.

Therefore, if we want to minimize total inventory cost, every time we place an order, we should

order the quantity (Q) that corresponds to the point where the two values are equal. If we set the

two costs equal and solve forQ we get:

H(Q/2) = S(D/Q)

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 5

Q = 2 DS/H

The quantity Q is known as the economic order quantity (EOQ). In order to minimize total

inventory cost, the firm will order Q every time it places an order. For example, a firm with an

annual demand of 12,000 units (at a purchase price of $25 each), annual holding cost of $10 per

unit and an order cost of $150 per order (with orders placed once a month) could save $800

annually by utilizing the EOQ. First, we determine the total costs without using the EOQ

method:

Q = $10(1000/2) + $150(12,000/1,000) + $25(12,000) = $306,800

Then we calculate EOQ:

EOQ = 2(12,000)($150)/$10 = 600

And we calculate total costs at the EOQ of 600:

Q = $10(600/2) + $150(12,000/600) + $25(12,000) = $306,000

Finally, we subtract the total cost of Q from Q to determine the savings:

$306,800 − 306,000 = $800

Notice that if you remove purchasing cost from the equation, the savings is still $800. We might

assume this means that purchasing cost is not relevant to our order decision and can be

eliminated from the equation. It must be noted that this is true only as long as no quantity

discount exists. If a quantity discount is available, the firm must determine whether the savings

of the quantity discount are sufficient to offset the loss of the savings resulting from the use of

the EOQ.

There are a number of assumptions that must be made with the use of the EOQ. These include:

Only one product is involved.

Demand is deterministic (known with certainty).

Demand is constant (stable throughout the year).

There are no quantity discounts.

Costs are constant (no price increases or inflation).

While these assumptions would seem to make EOQ irrelevant for use in a realistic situation, it is

relevant for items that have independent demand. This means that the demand for the item is not

derived from the demand for something else (usually a parent item for which the unit in question

is a component). For example, the demand for steering wheels would be derived from the

demand for automobiles (dependent demand) but the demand for purses is not derived from

anything else; purses have independent demand.

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 6

The quantity Q is known as the economic order quantity (EOQ). In order to minimize total

inventory cost, the firm will order Q every time it places an order. For example, a firm with an

annual demand of 12,000 units (at a purchase price of $25 each), annual holding cost of $10 per

unit and an order cost of $150 per order (with orders placed once a month) could save $800

annually by utilizing the EOQ. First, we determine the total costs without using the EOQ

method:

Q = $10(1000/2) + $150(12,000/1,000) + $25(12,000) = $306,800

Then we calculate EOQ:

EOQ = 2(12,000)($150)/$10 = 600

And we calculate total costs at the EOQ of 600:

Q = $10(600/2) + $150(12,000/600) + $25(12,000) = $306,000

Finally, we subtract the total cost of Q from Q to determine the savings:

$306,800 − 306,000 = $800

Notice that if you remove purchasing cost from the equation, the savings is still $800. We might

assume this means that purchasing cost is not relevant to our order decision and can be

eliminated from the equation. It must be noted that this is true only as long as no quantity

discount exists. If a quantity discount is available, the firm must determine whether the savings

of the quantity discount are sufficient to offset the loss of the savings resulting from the use of

the EOQ.

There are a number of assumptions that must be made with the use of the EOQ. These include:

Only one product is involved.

Demand is deterministic (known with certainty).

Demand is constant (stable throughout the year).

There are no quantity discounts.

Costs are constant (no price increases or inflation).

While these assumptions would seem to make EOQ irrelevant for use in a realistic situation, it is

relevant for items that have independent demand. This means that the demand for the item is not

derived from the demand for something else (usually a parent item for which the unit in question

is a component). For example, the demand for steering wheels would be derived from the

demand for automobiles (dependent demand) but the demand for purses is not derived from

anything else; purses have independent demand.

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 6

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

OTHER LOT-SIZING TECHNIQUES

There are a number of other lot-sizing techniques available in addition to EOQ. These include

the fixed-order quantity, fixed-order-interval model, the single-period model, and part-period

balancing.

Fixed-Order-Quantity Model. EOQ is an example of the fixed-order-quantity model since the

same quantity is ordered every time an order is placed. A firm might also use a fixed-order

quantity when it is captive to packaging situations. If you were to walk into an office supply

store and ask to buy twenty-two paper clips, chances are you would walk out with one hundred

paper clips. You were captive to the packaging requirements of paper clips, i.e., they come one

hundred to a box and you cannot purchase a partial box. It works the same way for other

purchasing situations. A supplier may package their goods in certain quantities so that their

customers must buy that quantity or a multiple of that quantity.

Fixed-Order-Interval Model. The fixed-order-interval model is used when orders have to be

placed at fixed time intervals such as weekly, biweekly, or monthly. The lot size is dependent

upon how much inventory is needed from the time of order until the next order must be placed

(order cycle). This system requires periodic checks of inventory levels and is used by many retail

firms such as drug stores and small grocery stores.

Single-Period Model. The single-period model is used in ordering perishables, such as food and

flowers, and items with a limited life, such as newspapers. Unsold or unused goods are not

typically carried over from one period to another and there may even be some disposal costs

involved. This model tries to balance the cost of lost customer goodwill and opportunity cost that

is incurred from not having enough inventory, with the cost of having excess inventory left at the

end of a period.

Part-Period Balancing. Part-period balancing attempts to select the number of periods covered

by the inventory order that will make total carrying costs as close as possible to the set-up/order

cost.

When a proper lot size has been determined, utilizing one of the above techniques, the reorder

point, or point at which an order should be placed, can be determined by the rate of demand and

the lead time. If safety stock is necessary it would be added to the reorder point quantity.

Reorder point = Expected demand during lead time + Safety stock

Thus, an inventory item with a demand of 100 per month, a two-month lead time and a desired

safety stock of two weeks would have a reorder point of 250. In other words, an order would be

placed whenever the inventory level for that good reached 250 units.

Reorder point = 100/month × 2 months + 2 weeks' safety stock = 250

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 7

There are a number of other lot-sizing techniques available in addition to EOQ. These include

the fixed-order quantity, fixed-order-interval model, the single-period model, and part-period

balancing.

Fixed-Order-Quantity Model. EOQ is an example of the fixed-order-quantity model since the

same quantity is ordered every time an order is placed. A firm might also use a fixed-order

quantity when it is captive to packaging situations. If you were to walk into an office supply

store and ask to buy twenty-two paper clips, chances are you would walk out with one hundred

paper clips. You were captive to the packaging requirements of paper clips, i.e., they come one

hundred to a box and you cannot purchase a partial box. It works the same way for other

purchasing situations. A supplier may package their goods in certain quantities so that their

customers must buy that quantity or a multiple of that quantity.

Fixed-Order-Interval Model. The fixed-order-interval model is used when orders have to be

placed at fixed time intervals such as weekly, biweekly, or monthly. The lot size is dependent

upon how much inventory is needed from the time of order until the next order must be placed

(order cycle). This system requires periodic checks of inventory levels and is used by many retail

firms such as drug stores and small grocery stores.

Single-Period Model. The single-period model is used in ordering perishables, such as food and

flowers, and items with a limited life, such as newspapers. Unsold or unused goods are not

typically carried over from one period to another and there may even be some disposal costs

involved. This model tries to balance the cost of lost customer goodwill and opportunity cost that

is incurred from not having enough inventory, with the cost of having excess inventory left at the

end of a period.

Part-Period Balancing. Part-period balancing attempts to select the number of periods covered

by the inventory order that will make total carrying costs as close as possible to the set-up/order

cost.

When a proper lot size has been determined, utilizing one of the above techniques, the reorder

point, or point at which an order should be placed, can be determined by the rate of demand and

the lead time. If safety stock is necessary it would be added to the reorder point quantity.

Reorder point = Expected demand during lead time + Safety stock

Thus, an inventory item with a demand of 100 per month, a two-month lead time and a desired

safety stock of two weeks would have a reorder point of 250. In other words, an order would be

placed whenever the inventory level for that good reached 250 units.

Reorder point = 100/month × 2 months + 2 weeks' safety stock = 250

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 7

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

OTHER SCHOOLS OF THOUGHT IN INVENTORY

MANAGEMENT

There are a number of techniques and philosophies that view inventory management from

different perspectives.

MRP and MRP II. MRP and MRP II are computer-based resource management systems

designed for items that have dependent demand. MRP and MRP II look at order quantities period

by period and, as such, allow discrete ordering (ordering only what is currently needed). In this

way inventory levels can be kept at a very low level; a necessity for a complex item with

dependent demand.

Just-In-Time (JIT). Just-in-time (JIT) is a philosophy that advocates the lowest possible levels

of inventory. JIT espouses that firms need only keep inventory in the right quantity at the right

time with the right quality. The ideal lot size for JIT is one, even though one hears the term “zero

inventory” used.

Theory of Constraints (TOC). Theory of constraints (TOC) is a philosophy which emphasizes

that all management actions should center around the firm's constraints. While it agrees with JIT

that inventory should be at the lowest level possible in most instances, it advocates that there be

some buffer inventory around any capacity constraint (e.g., the slowest machine) and before

finished goods.

THE FUTURE OF INVENTORY MANAGEMENT

The advent, through altruism or legislation, of environmental management has added a new

dimension to inventory management-reverse supply chain logistics. Environmental management

has expanded the number of inventory types that firms have to coordinate. In addition to raw

materials, work-in-process, finished goods, and MRO goods, firms now have to deal with post-

consumer items such as scrap, returned goods, reusable or recyclable containers, and any number

of items that require repair, reuse, recycling, or secondary use in another product. Retailers have

the same type of problems dealing with inventory that has been returned due to defective

material or manufacture, poor fit, finish, or color, or outright “I changed my mind” responses

from customers.

Finally, supply chain management has had a considerable impact on inventory management.

Instead of managing one's inventory to maximize profit and minimize cost for the individual

firm, today's firm has to make inventory decisions that benefit the entire supply chain. Through

the use of real-time and end-to-end supplier chain reporting technologies, buyers can know

exactly where their products are in the supply chain, how much they have in stock, and even how

much their supplier can provide.

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 8

MANAGEMENT

There are a number of techniques and philosophies that view inventory management from

different perspectives.

MRP and MRP II. MRP and MRP II are computer-based resource management systems

designed for items that have dependent demand. MRP and MRP II look at order quantities period

by period and, as such, allow discrete ordering (ordering only what is currently needed). In this

way inventory levels can be kept at a very low level; a necessity for a complex item with

dependent demand.

Just-In-Time (JIT). Just-in-time (JIT) is a philosophy that advocates the lowest possible levels

of inventory. JIT espouses that firms need only keep inventory in the right quantity at the right

time with the right quality. The ideal lot size for JIT is one, even though one hears the term “zero

inventory” used.

Theory of Constraints (TOC). Theory of constraints (TOC) is a philosophy which emphasizes

that all management actions should center around the firm's constraints. While it agrees with JIT

that inventory should be at the lowest level possible in most instances, it advocates that there be

some buffer inventory around any capacity constraint (e.g., the slowest machine) and before

finished goods.

THE FUTURE OF INVENTORY MANAGEMENT

The advent, through altruism or legislation, of environmental management has added a new

dimension to inventory management-reverse supply chain logistics. Environmental management

has expanded the number of inventory types that firms have to coordinate. In addition to raw

materials, work-in-process, finished goods, and MRO goods, firms now have to deal with post-

consumer items such as scrap, returned goods, reusable or recyclable containers, and any number

of items that require repair, reuse, recycling, or secondary use in another product. Retailers have

the same type of problems dealing with inventory that has been returned due to defective

material or manufacture, poor fit, finish, or color, or outright “I changed my mind” responses

from customers.

Finally, supply chain management has had a considerable impact on inventory management.

Instead of managing one's inventory to maximize profit and minimize cost for the individual

firm, today's firm has to make inventory decisions that benefit the entire supply chain. Through

the use of real-time and end-to-end supplier chain reporting technologies, buyers can know

exactly where their products are in the supply chain, how much they have in stock, and even how

much their supplier can provide.

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 8

Management consultants from McKinsey & Company said in late 2007 that emerging

technologies have increased and will continue to increase automation for managing capital and

assets. Carrefour, Metro, Wal-Mart Stores, and other large retailers have adopted (and asked

suppliers to adopt) digital-tagging technologies, such as radio frequency identification (RFID).

These stores are further automating their supply chain and inventory management by integrated

digital tag technologies with other supply chain systems. As the price of these digital tags falls,

they will reduce the costs of managing distribution and increase revenues by helping companies

to manage supply more effectively.

SEE ALSO Aggregate Planning ; Inventory Types ; Lean Manufacturing and Just-in-Time

Production ; Manufacturing Resources Planning ; Reverse Supply Chain Logistics ; Supply

Chain Management

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Biederman, David. “Reversing Inventory Management.” Traffic World 12 December 2004: 1.

“Eight Business Technology Trends to Watch.” CNETNews.com 26 December 2007. Available

from: http://news.cnet.com/Eight-business-technology-trends-to-watch/2030-1069_3-

6223397.html .

Stevenson, William J. Production Operations Management. Boston, MA: Irwin/McGraw-Hill,

2005.

Sucky, Eric. “Inventory Management in Supply Chains: A Bargaining Problem.” International

Journal of Production Economics 93/94, no. 1 (2005): 253–262.

Varmazis, Maria. “Inventory Management: Software Shines Light on Savings.” Purchasing 17

January 2008. Available from: http://www.purchasing.com/article/CA6518764.html .

Source Citation (MLA 7th Edition)

"Inventory Management." Encyclopedia of Management. 6th ed. Detroit: Gale, 2009. 421-425. Gale Virtual

Reference Library. Web. 18 Oct. 2016.

URL

http://ezproxy.umuc.edu/login?url=http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?

p=GVRL&sw=w&u=umd_umuc&v=2.1&id=GALE

%7CCX3273100143&it=r&asid=0018bd220f65bfe0641e6703bce372d2

Gale Document Number: GALE|CX3273100143

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~'

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 9

technologies have increased and will continue to increase automation for managing capital and

assets. Carrefour, Metro, Wal-Mart Stores, and other large retailers have adopted (and asked

suppliers to adopt) digital-tagging technologies, such as radio frequency identification (RFID).

These stores are further automating their supply chain and inventory management by integrated

digital tag technologies with other supply chain systems. As the price of these digital tags falls,

they will reduce the costs of managing distribution and increase revenues by helping companies

to manage supply more effectively.

SEE ALSO Aggregate Planning ; Inventory Types ; Lean Manufacturing and Just-in-Time

Production ; Manufacturing Resources Planning ; Reverse Supply Chain Logistics ; Supply

Chain Management

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Biederman, David. “Reversing Inventory Management.” Traffic World 12 December 2004: 1.

“Eight Business Technology Trends to Watch.” CNETNews.com 26 December 2007. Available

from: http://news.cnet.com/Eight-business-technology-trends-to-watch/2030-1069_3-

6223397.html .

Stevenson, William J. Production Operations Management. Boston, MA: Irwin/McGraw-Hill,

2005.

Sucky, Eric. “Inventory Management in Supply Chains: A Bargaining Problem.” International

Journal of Production Economics 93/94, no. 1 (2005): 253–262.

Varmazis, Maria. “Inventory Management: Software Shines Light on Savings.” Purchasing 17

January 2008. Available from: http://www.purchasing.com/article/CA6518764.html .

Source Citation (MLA 7th Edition)

"Inventory Management." Encyclopedia of Management. 6th ed. Detroit: Gale, 2009. 421-425. Gale Virtual

Reference Library. Web. 18 Oct. 2016.

URL

http://ezproxy.umuc.edu/login?url=http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?

p=GVRL&sw=w&u=umd_umuc&v=2.1&id=GALE

%7CCX3273100143&it=r&asid=0018bd220f65bfe0641e6703bce372d2

Gale Document Number: GALE|CX3273100143

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~'

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 9

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Inventory Management

Inventory management is primarily concerned with specifying the shape and percentage

of stocked goods to reduce costs and improve sales.

Learning Objective

Recognize the applications and benefits of inventory management

Key Points

o Inventory refers to a list compiled for some formal purpose, such as the details of an

estate or the contents of a rented house.

o Inventory management is required at different locations within a facility or within many

locations of a supply network in order to plan for the production and stock of materials.

o Inventory management addresses issues including: replenishment lead time; carrying

costs of inventory; asset management; inventory forecasting; inventory valuation;

inventory visibility; and future inventory price forecasting.

o Supply chain activities can be grouped into strategic, tactical, and operational categories.

o Supply chain activities can be grouped into strategic, tactical, and operational levels.

Terms

tactical planning

an organization's process of determining how to optimize current resources and

operations

supply chain

A supply chain is a system of organizations, people, technology, activities,

information and resources involved in moving a product or service from supplier

to customer.

In the United Kingdom, inventory typically refers to a list compiled for some formal

purpose, such as one that itemizes an estate going to probate or the contents of a

furnished house to be rented. In the U.S. and Canada, inventory has become the

equivalent of the British term stock; that is, it refers to material that is available from and

stocked by a business. In the context of accounting, inventory or stock is considered an

asset.

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 10

Inventory management is primarily concerned with specifying the shape and percentage

of stocked goods to reduce costs and improve sales.

Learning Objective

Recognize the applications and benefits of inventory management

Key Points

o Inventory refers to a list compiled for some formal purpose, such as the details of an

estate or the contents of a rented house.

o Inventory management is required at different locations within a facility or within many

locations of a supply network in order to plan for the production and stock of materials.

o Inventory management addresses issues including: replenishment lead time; carrying

costs of inventory; asset management; inventory forecasting; inventory valuation;

inventory visibility; and future inventory price forecasting.

o Supply chain activities can be grouped into strategic, tactical, and operational categories.

o Supply chain activities can be grouped into strategic, tactical, and operational levels.

Terms

tactical planning

an organization's process of determining how to optimize current resources and

operations

supply chain

A supply chain is a system of organizations, people, technology, activities,

information and resources involved in moving a product or service from supplier

to customer.

In the United Kingdom, inventory typically refers to a list compiled for some formal

purpose, such as one that itemizes an estate going to probate or the contents of a

furnished house to be rented. In the U.S. and Canada, inventory has become the

equivalent of the British term stock; that is, it refers to material that is available from and

stocked by a business. In the context of accounting, inventory or stock is considered an

asset.

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 10

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

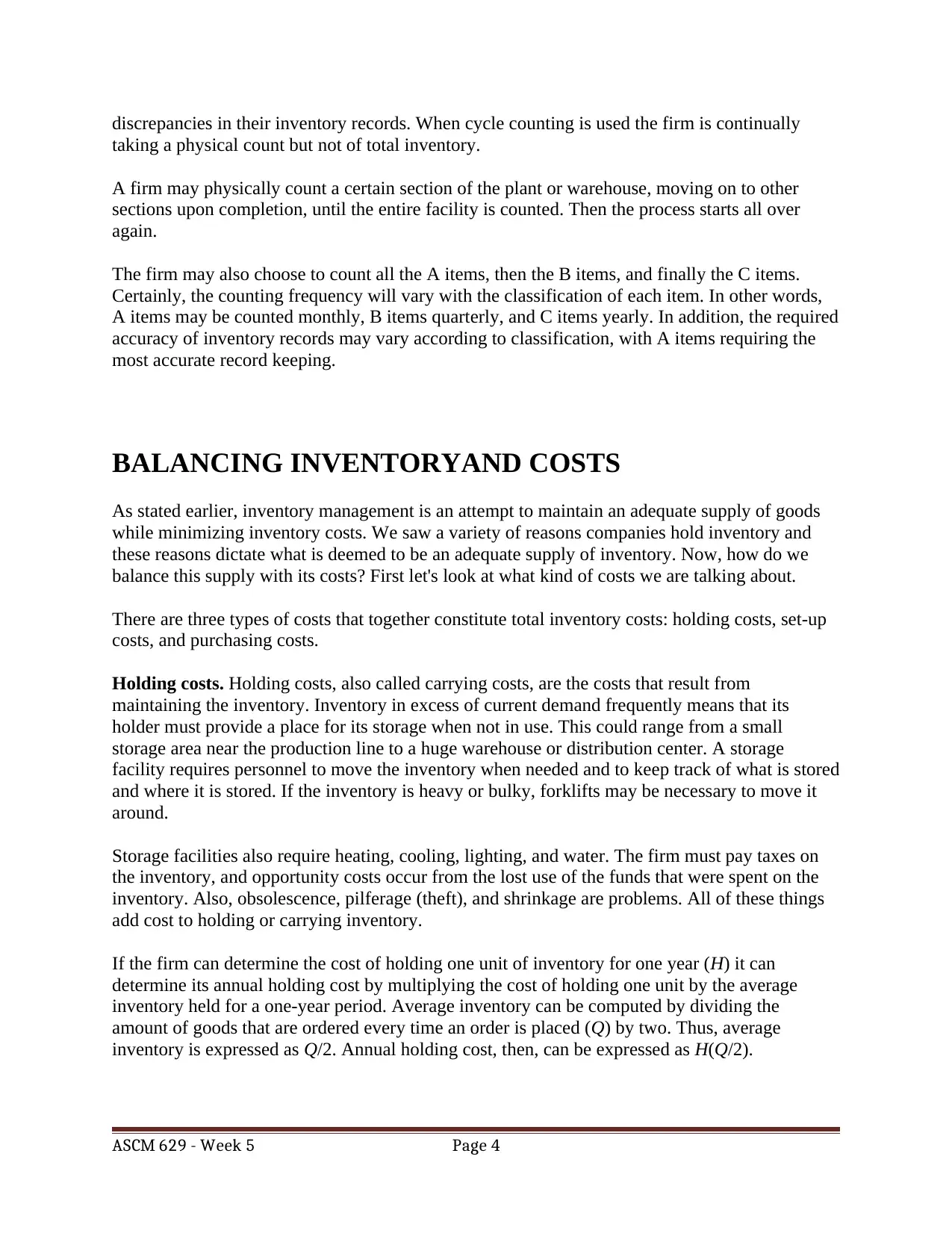

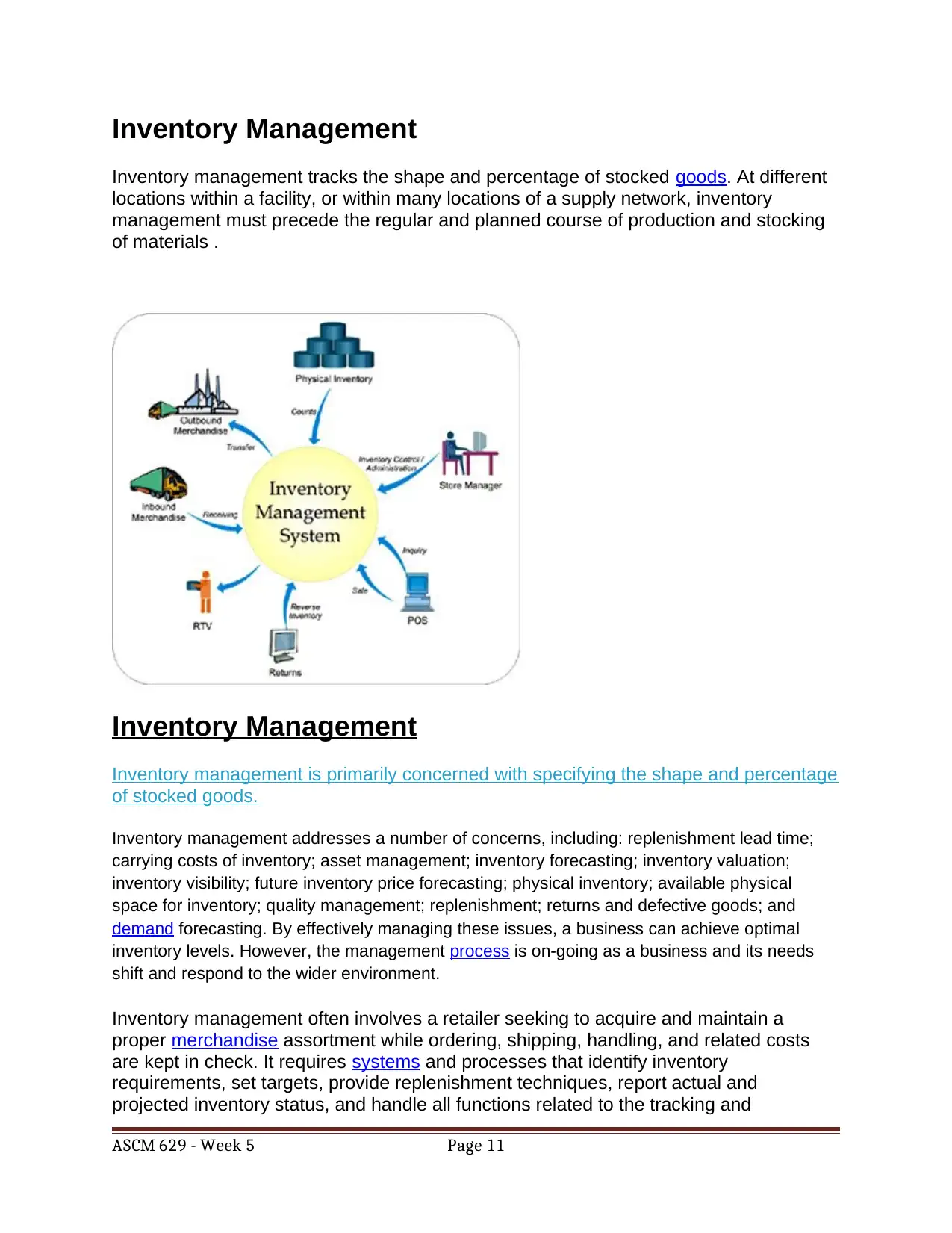

Inventory Management

Inventory management tracks the shape and percentage of stocked goods. At different

locations within a facility, or within many locations of a supply network, inventory

management must precede the regular and planned course of production and stocking

of materials .

Inventory Management

Inventory management is primarily concerned with specifying the shape and percentage

of stocked goods.

Inventory management addresses a number of concerns, including: replenishment lead time;

carrying costs of inventory; asset management; inventory forecasting; inventory valuation;

inventory visibility; future inventory price forecasting; physical inventory; available physical

space for inventory; quality management; replenishment; returns and defective goods; and

demand forecasting. By effectively managing these issues, a business can achieve optimal

inventory levels. However, the management process is on-going as a business and its needs

shift and respond to the wider environment.

Inventory management often involves a retailer seeking to acquire and maintain a

proper merchandise assortment while ordering, shipping, handling, and related costs

are kept in check. It requires systems and processes that identify inventory

requirements, set targets, provide replenishment techniques, report actual and

projected inventory status, and handle all functions related to the tracking and

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 11

Inventory management tracks the shape and percentage of stocked goods. At different

locations within a facility, or within many locations of a supply network, inventory

management must precede the regular and planned course of production and stocking

of materials .

Inventory Management

Inventory management is primarily concerned with specifying the shape and percentage

of stocked goods.

Inventory management addresses a number of concerns, including: replenishment lead time;

carrying costs of inventory; asset management; inventory forecasting; inventory valuation;

inventory visibility; future inventory price forecasting; physical inventory; available physical

space for inventory; quality management; replenishment; returns and defective goods; and

demand forecasting. By effectively managing these issues, a business can achieve optimal

inventory levels. However, the management process is on-going as a business and its needs

shift and respond to the wider environment.

Inventory management often involves a retailer seeking to acquire and maintain a

proper merchandise assortment while ordering, shipping, handling, and related costs

are kept in check. It requires systems and processes that identify inventory

requirements, set targets, provide replenishment techniques, report actual and

projected inventory status, and handle all functions related to the tracking and

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 11

management of material. These include the monitoring of material moved into and out

of stockroom locations, as well as the reconciling of inventory balances. Processes may

also include ABC analysis, lot tracking, and cycle counting support.

Management of inventories, aimed primarily at determining and controlling stock levels

within the physical distribution system, serves to balance the need for product

availability against the need for minimizing stock holding and handling costs. Reasons

for keeping an inventory include:

Time: The time lag in the supply chain from supplier to user requires the availability of a certain

amount of inventory for use during this lead time. In practice, inventory is maintained for

consumption during variations in lead time, and lead time itself can be addressed by ordering a

specified number of days in advance.

Uncertainty: Inventories are maintained as buffers to meet uncertainties in demand, supply, and

movement of goods.

Economies of scale: To deliver one unit of product at a time, and in response to the specific need

and location of a given user, would be costly and logistically difficult. In contrast, bulk buying,

movement, and storage translate into economies of scale and inventory.

Inventory and the Supply Chain

Supply chain activities can be grouped into strategic, tactical, and operational levels.

Inventory considerations present at each level include:

Strategic: Network optimization, including the number, location, and size of

warehousing, distribution centers, and facilities.

Tactical: Inventory decisions, including quantity, location, and quality of inventory.

Operational: Sourcing planning, including current inventory and forecast demand, done

in collaboration with all suppliers; inbound operations, including transportation from

suppliers and receiving inventory; outbound operations, including all fulfillment activities,

warehousing, and transportation to customers; management of non-moving, short-dated

inventory and avoidance of short-dated products.

Source: Boundless. “Inventory Management.” Boundless Business. Boundless, 08 Aug. 2016. Retrieved

18 Oct. 2016 from https://www.boundless.com/business/textbooks/boundless-business-textbook/

operations-management-10/controlling-the-supply-chain-72/inventory-management-338-7464/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~'

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 12

of stockroom locations, as well as the reconciling of inventory balances. Processes may

also include ABC analysis, lot tracking, and cycle counting support.

Management of inventories, aimed primarily at determining and controlling stock levels

within the physical distribution system, serves to balance the need for product

availability against the need for minimizing stock holding and handling costs. Reasons

for keeping an inventory include:

Time: The time lag in the supply chain from supplier to user requires the availability of a certain

amount of inventory for use during this lead time. In practice, inventory is maintained for

consumption during variations in lead time, and lead time itself can be addressed by ordering a

specified number of days in advance.

Uncertainty: Inventories are maintained as buffers to meet uncertainties in demand, supply, and

movement of goods.

Economies of scale: To deliver one unit of product at a time, and in response to the specific need

and location of a given user, would be costly and logistically difficult. In contrast, bulk buying,

movement, and storage translate into economies of scale and inventory.

Inventory and the Supply Chain

Supply chain activities can be grouped into strategic, tactical, and operational levels.

Inventory considerations present at each level include:

Strategic: Network optimization, including the number, location, and size of

warehousing, distribution centers, and facilities.

Tactical: Inventory decisions, including quantity, location, and quality of inventory.

Operational: Sourcing planning, including current inventory and forecast demand, done

in collaboration with all suppliers; inbound operations, including transportation from

suppliers and receiving inventory; outbound operations, including all fulfillment activities,

warehousing, and transportation to customers; management of non-moving, short-dated

inventory and avoidance of short-dated products.

Source: Boundless. “Inventory Management.” Boundless Business. Boundless, 08 Aug. 2016. Retrieved

18 Oct. 2016 from https://www.boundless.com/business/textbooks/boundless-business-textbook/

operations-management-10/controlling-the-supply-chain-72/inventory-management-338-7464/

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~'

ASCM 629 - Week 5 Page 12

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 26

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2025 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.