Comparative Analysis: Islamic and State Courts in Singapore

VerifiedAdded on 2022/08/17

|14

|3623

|16

Report

AI Summary

This report provides an overview of the dual court system in Singapore, focusing on the jurisdiction and evolution of both Islamic (Sharia) and State courts. It examines the historical context of Islamic law, the establishment of the Syariah Court, and its role in regulating Muslim marriages, divorces, and related matters. The report highlights the impact of the Syariah Court on divorce rates and the development of conciliation services. It also details the structure and functions of the State courts, including their jurisdiction over civil and criminal cases. The analysis includes a comparison of the two court systems, addressing the resolution of conflicts, the influence of traditional practices, and the application of Islamic law in Singapore's legal framework, with references to relevant literature.

Running head: REPORT

Report

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Report

Name of the Student

Name of the University

Authors Note

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

1REPORT

ANSWER- 2

Islamic court or Islamic courts may denote the following courts, such as:

Islamic court, which follows Sharia;

Sharia courts, situated in the judiciary of the Saudi Arabia;

Syariah Court, situated in Malaysia;

Islamic Revolutionary Court, a special systematic court in the Islamic Republic of

Iran;

Islamic Courts Union, situated in Somalia.

Previously, Islamic law or Sharia always present in the Islamic states. These laws were

interpreted by several independent jurists the basis of which was sources of scripts and several

lawful mythologies. In the present era, the outdated laws are replaced by the European codes in

numerous parts of the Muslim world along with the rules of classical sharia reserved in family

laws (Bin Abbas, 2012). This law has been codified by statutory bodies that have tried to

modernize it without ignoring conventional legal jurisprudence. The Islamic renaissance took

place at the end of the 20th century. Islamist movements called for the complete application of

Sharia law, including capital punishments, namely hudud, such as stoning, which in certain case

led to conventional legal restructuring (Lindsey, 2016). Some Muslim minority nations use

Sharia laws in order to control the marriage between Muslim People, legacy and other private

affairs. Many scholars and academics are of the view that nowadays, the Islamic are gaining

influence in some countries in Southeast Asia. Singapore is a sovereign island town-state in

Southeast Asia, formally known as Republic of Singapore. Sharia courts may hear and decide

acts in which all parties are Muslim or parties concerned are married according to the Islamic

law (Jani & Hassan, 2015). Court has jurisdiction over marriage proceedings, divorces, marital

ANSWER- 2

Islamic court or Islamic courts may denote the following courts, such as:

Islamic court, which follows Sharia;

Sharia courts, situated in the judiciary of the Saudi Arabia;

Syariah Court, situated in Malaysia;

Islamic Revolutionary Court, a special systematic court in the Islamic Republic of

Iran;

Islamic Courts Union, situated in Somalia.

Previously, Islamic law or Sharia always present in the Islamic states. These laws were

interpreted by several independent jurists the basis of which was sources of scripts and several

lawful mythologies. In the present era, the outdated laws are replaced by the European codes in

numerous parts of the Muslim world along with the rules of classical sharia reserved in family

laws (Bin Abbas, 2012). This law has been codified by statutory bodies that have tried to

modernize it without ignoring conventional legal jurisprudence. The Islamic renaissance took

place at the end of the 20th century. Islamist movements called for the complete application of

Sharia law, including capital punishments, namely hudud, such as stoning, which in certain case

led to conventional legal restructuring (Lindsey, 2016). Some Muslim minority nations use

Sharia laws in order to control the marriage between Muslim People, legacy and other private

affairs. Many scholars and academics are of the view that nowadays, the Islamic are gaining

influence in some countries in Southeast Asia. Singapore is a sovereign island town-state in

Southeast Asia, formally known as Republic of Singapore. Sharia courts may hear and decide

acts in which all parties are Muslim or parties concerned are married according to the Islamic

law (Jani & Hassan, 2015). Court has jurisdiction over marriage proceedings, divorces, marital

2REPORT

disputes, marriage cases related with nullity, judicial separation, splits of property on divorce

cases, dowry payments, maintenance and muta cases. In this way influence has been spread by

these courts. Sharia law is considered to be a part of the Islamic tradition. Modern Islamic case

law theory accepts 4 Sharia sources: the Quran, sunnah (authentic hadeeth), qiyas (analogy), and

ijma (legal consensus). The methodologies for originating Shari decisions from theological

sources are established by diverse legal schools, most popular of which are Hanafi, Maliki,

Shafi'i, Hanbali and Jafari. Two main areas of law, such as the Últra-Bibâdāt (rituals) and the

Últra-Muāmalāt (social relations) are characterized by traditional jurisprudence. Many parts of

sharia thus align with the Western notion of law, while others more closely relate to the life of

God.

In the first half of the 20th century, the rate of divorce among the Muslims was very high

throughout Singapore. During the war years it peaked at 667 out of 1000 Muslim weddings prior

to its collapse to 493 in 1958. The high level of divorce was accredited to easy divorce at the

time because the old Muslim Ordinances of 1880 had little limitations or advice services. The

high rate of divorce has led to significant social difficulties and problems, leading to lobby for a

new legislation by many Malaysia's society and self-help organizations. In 1951, a subcommittee

was established by the Muslim Consultative Committee in order to make a draft amendment to

prevailing legislation (Feener, 2012). The attempts to amend the law resulted in the adoption by

the Legislative Council of 1957 of the Muslim Ordinance. Nevertheless, a new Muslim Bill was

scheduled at the Legislative Assembly only on 21 November 1955, and its second reading took

place nine months later, the next year, on 2 August. The efforts to reform law culminated in the

promulgation by the Legislative Council in August 1957 of the Muslim Ordinance of 1957. It

provided for the establishment of a Syariah (matrimonial) Court with the sole authority to record

disputes, marriage cases related with nullity, judicial separation, splits of property on divorce

cases, dowry payments, maintenance and muta cases. In this way influence has been spread by

these courts. Sharia law is considered to be a part of the Islamic tradition. Modern Islamic case

law theory accepts 4 Sharia sources: the Quran, sunnah (authentic hadeeth), qiyas (analogy), and

ijma (legal consensus). The methodologies for originating Shari decisions from theological

sources are established by diverse legal schools, most popular of which are Hanafi, Maliki,

Shafi'i, Hanbali and Jafari. Two main areas of law, such as the Últra-Bibâdāt (rituals) and the

Últra-Muāmalāt (social relations) are characterized by traditional jurisprudence. Many parts of

sharia thus align with the Western notion of law, while others more closely relate to the life of

God.

In the first half of the 20th century, the rate of divorce among the Muslims was very high

throughout Singapore. During the war years it peaked at 667 out of 1000 Muslim weddings prior

to its collapse to 493 in 1958. The high level of divorce was accredited to easy divorce at the

time because the old Muslim Ordinances of 1880 had little limitations or advice services. The

high rate of divorce has led to significant social difficulties and problems, leading to lobby for a

new legislation by many Malaysia's society and self-help organizations. In 1951, a subcommittee

was established by the Muslim Consultative Committee in order to make a draft amendment to

prevailing legislation (Feener, 2012). The attempts to amend the law resulted in the adoption by

the Legislative Council of 1957 of the Muslim Ordinance. Nevertheless, a new Muslim Bill was

scheduled at the Legislative Assembly only on 21 November 1955, and its second reading took

place nine months later, the next year, on 2 August. The efforts to reform law culminated in the

promulgation by the Legislative Council in August 1957 of the Muslim Ordinance of 1957. It

provided for the establishment of a Syariah (matrimonial) Court with the sole authority to record

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

3REPORT

divorces not made by mutual consent. In the case of Muslim divorces, Syariah Court strictly

restricted the rights of the Kathis who had been traditionally religious. On 24 November 1958,

the Syariah Court was created. In compliance with Islamic law, the court strained the supervision

of Muslim divorces in Singapore and developed qualified conciliation services. As per a report

published in 1960, the Muslim divorce rate drops to 273 per 1000 Muslim marriages in 1959,

from 493 in 1958, just after one year from the establishment of the Syariah Court. The

decreasing trend sustained until in 1975, the rate of divorce reached a record level of 94 per

1,000 Muslim marriages. This was a result of positive reaction of Muslims to the Syariah Court

which is working to improve the harmony of marriages between the Muslim communities in

Singapore (Lombardi & Feener, 2012).

In the court system of Singapore, two tiers are observed there. The Singaporean State

courts, which are generally known as Subordinate courts are situated in one tier, whereas the

Supreme Court is situated in another tier. The District and the Court of Magistrates, which both

supervise civil and criminal cases, along with specialized Courts, namely, the Court of Corons

and the Court of Little Claims, are also regarded as the State Courts. The State courts are

composed of Districts and Magistrates courts. More than 95% of entire cases are heard in the

Singapore State Courts, including civil and criminal cases which do not fall within the remit of

the Supreme Court (Black, 2012). Almost 350,000 cases are heard yearly in the State courts. The

judges, magistrates and registrars involved in the State courts are regarded as officers of legal

service legal services and served their duties under the regulation and observation of the Legal

Service Commission of Singapore. The appointment of the judges and Magistrates are based

upon the recommendation of the Chief Justice. After recommendation received from the Chief

Justice, judges and Magistrates shall be appointed by the President (Hassan & Alhabshi, 2012).

divorces not made by mutual consent. In the case of Muslim divorces, Syariah Court strictly

restricted the rights of the Kathis who had been traditionally religious. On 24 November 1958,

the Syariah Court was created. In compliance with Islamic law, the court strained the supervision

of Muslim divorces in Singapore and developed qualified conciliation services. As per a report

published in 1960, the Muslim divorce rate drops to 273 per 1000 Muslim marriages in 1959,

from 493 in 1958, just after one year from the establishment of the Syariah Court. The

decreasing trend sustained until in 1975, the rate of divorce reached a record level of 94 per

1,000 Muslim marriages. This was a result of positive reaction of Muslims to the Syariah Court

which is working to improve the harmony of marriages between the Muslim communities in

Singapore (Lombardi & Feener, 2012).

In the court system of Singapore, two tiers are observed there. The Singaporean State

courts, which are generally known as Subordinate courts are situated in one tier, whereas the

Supreme Court is situated in another tier. The District and the Court of Magistrates, which both

supervise civil and criminal cases, along with specialized Courts, namely, the Court of Corons

and the Court of Little Claims, are also regarded as the State Courts. The State courts are

composed of Districts and Magistrates courts. More than 95% of entire cases are heard in the

Singapore State Courts, including civil and criminal cases which do not fall within the remit of

the Supreme Court (Black, 2012). Almost 350,000 cases are heard yearly in the State courts. The

judges, magistrates and registrars involved in the State courts are regarded as officers of legal

service legal services and served their duties under the regulation and observation of the Legal

Service Commission of Singapore. The appointment of the judges and Magistrates are based

upon the recommendation of the Chief Justice. After recommendation received from the Chief

Justice, judges and Magistrates shall be appointed by the President (Hassan & Alhabshi, 2012).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

4REPORT

In the State Courts there are six main operating units as per the most recent annual report. These

include the Division of Civil Justice, the Division of Social Justice and Courts, the Division of

Criminal Justice, the Dispute Resolution Center, the Corporate Division, and the Division of

Strategic Planning & Technology. The overall accountability for the purpose of administering

the functions of the State courts and Tribunals, the presiding judge of the State courts and a judge

of the Supreme Court or a Judiciary Commissioner play an active role. The Presiding Judge of

the Court leads a team of judicial officials who decide on cases before the State Courts. The

Deputy Chairman Judge or Registrar and the Corporate and Court Services Department supports

the Presiding Judge directorially. The Family Justice Court was formed in October 2014, and

since then the cases relating to the family and to young people no longer fall within the

jurisdiction of the State Courts (Bell, 2006).

While discussing the jurisdiction of Islamic and State courts it can be said that the Islamic

courts or Sharia courts have the jurisdiction over marriage and divorce. On the other hand, as

provided in Articles 112 and 115 of the Law of Muslim Law administration, the Syariah Court

shall be responsible for distributing the property of a deceased to his or her relatives according to

Islamic law. The State courts have the jurisdiction over all civil and criminal cases.

Over time, many traditions have evolved and can be combined to resolve conflicts: tribal

law, Muslim law and traditional Sharia practices. Conflict resolution practices in Singapore aim

to restore individual and community harmony, by means of third party authority, such as

mediator, arbitrator, instead of providing an opportunity for contentious parties to make their

complaints public (Cederroth & Hassan, 2012). The arbitrator, mediator could push them to

come to an agreement. Many authors stated this system as a tool to control society. Power

imbalances are thus a crucial factor in these systems and can be used instead of modifying.

In the State Courts there are six main operating units as per the most recent annual report. These

include the Division of Civil Justice, the Division of Social Justice and Courts, the Division of

Criminal Justice, the Dispute Resolution Center, the Corporate Division, and the Division of

Strategic Planning & Technology. The overall accountability for the purpose of administering

the functions of the State courts and Tribunals, the presiding judge of the State courts and a judge

of the Supreme Court or a Judiciary Commissioner play an active role. The Presiding Judge of

the Court leads a team of judicial officials who decide on cases before the State Courts. The

Deputy Chairman Judge or Registrar and the Corporate and Court Services Department supports

the Presiding Judge directorially. The Family Justice Court was formed in October 2014, and

since then the cases relating to the family and to young people no longer fall within the

jurisdiction of the State Courts (Bell, 2006).

While discussing the jurisdiction of Islamic and State courts it can be said that the Islamic

courts or Sharia courts have the jurisdiction over marriage and divorce. On the other hand, as

provided in Articles 112 and 115 of the Law of Muslim Law administration, the Syariah Court

shall be responsible for distributing the property of a deceased to his or her relatives according to

Islamic law. The State courts have the jurisdiction over all civil and criminal cases.

Over time, many traditions have evolved and can be combined to resolve conflicts: tribal

law, Muslim law and traditional Sharia practices. Conflict resolution practices in Singapore aim

to restore individual and community harmony, by means of third party authority, such as

mediator, arbitrator, instead of providing an opportunity for contentious parties to make their

complaints public (Cederroth & Hassan, 2012). The arbitrator, mediator could push them to

come to an agreement. Many authors stated this system as a tool to control society. Power

imbalances are thus a crucial factor in these systems and can be used instead of modifying.

5REPORT

The Morocco case can be discusses in this regard. Since the presence of Berber tribes in

the Atlas Mountains, traditional methods of clash resolution have been utilized in Morocco.

Conflicts originally were settled by the hereditary "saints," who lived alone from the tribes, but

served a variety of purposes, including the one of the ‘mediators’

The Morocco case can be discusses in this regard. Since the presence of Berber tribes in

the Atlas Mountains, traditional methods of clash resolution have been utilized in Morocco.

Conflicts originally were settled by the hereditary "saints," who lived alone from the tribes, but

served a variety of purposes, including the one of the ‘mediators’

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

6REPORT

Reference

Bell, G. F. (2006). Multiculturalism in Law is Legal Pluralism-Lessons from Indonesia,

Singapore and Canada. Sing. J. Legal Stud., 315.

Bin Abbas, A. N. (2012). Islamic Legal System in Singapore, THe. Pac. Rim L. & Pol'y J., 21,

163.

Black, A. (2012). Lessons From Singapore An Evaluation Of The Singapore Model Of Legal

Pluralism. Asian Law Institute Working Paper, 026.

Cederroth, S. C., & Hassan, S. Z. S. (2012). Managing marital disputes in Malaysia: Islamic

mediators and conflict resolution in the Syariah Courts. Routledge.

Feener, R. M. (2012). Social engineering through sharī'a: Islamic law and state-directed da'wa in

contemporary Aceh. Islamic Law and Society, 19(3), 275-311.

Hassan, M. H., & Alhabshi, S. T. S. A. A. (2012). The training, appointment, and supervision of

Islamic judges in Singapore. Pac. Rim L. & Pol'y J., 21, 189.

Jani, N., & Hassan, R. (2015). Dispute Resolution in Singapore: Challenges and Opportunities

for Islamic Finance. Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance, 113(3158), 1-

20.

Lindsey, T. (2016). Islamic courts or courts for Muslims? Shari’a and the state in Indonesia,

Malaysia and Singapore. In Routledge Handbook of Asian Law (pp. 355-375).

Routledge.

Lombardi, C. B., & Feener, R. M. (2012). Why study Islamic legal professionals. Pac. Rim L. &

Pol'y J., 21, 1.

Reference

Bell, G. F. (2006). Multiculturalism in Law is Legal Pluralism-Lessons from Indonesia,

Singapore and Canada. Sing. J. Legal Stud., 315.

Bin Abbas, A. N. (2012). Islamic Legal System in Singapore, THe. Pac. Rim L. & Pol'y J., 21,

163.

Black, A. (2012). Lessons From Singapore An Evaluation Of The Singapore Model Of Legal

Pluralism. Asian Law Institute Working Paper, 026.

Cederroth, S. C., & Hassan, S. Z. S. (2012). Managing marital disputes in Malaysia: Islamic

mediators and conflict resolution in the Syariah Courts. Routledge.

Feener, R. M. (2012). Social engineering through sharī'a: Islamic law and state-directed da'wa in

contemporary Aceh. Islamic Law and Society, 19(3), 275-311.

Hassan, M. H., & Alhabshi, S. T. S. A. A. (2012). The training, appointment, and supervision of

Islamic judges in Singapore. Pac. Rim L. & Pol'y J., 21, 189.

Jani, N., & Hassan, R. (2015). Dispute Resolution in Singapore: Challenges and Opportunities

for Islamic Finance. Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance, 113(3158), 1-

20.

Lindsey, T. (2016). Islamic courts or courts for Muslims? Shari’a and the state in Indonesia,

Malaysia and Singapore. In Routledge Handbook of Asian Law (pp. 355-375).

Routledge.

Lombardi, C. B., & Feener, R. M. (2012). Why study Islamic legal professionals. Pac. Rim L. &

Pol'y J., 21, 1.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

7REPORT

Answer- 3

Minerals and metals are important to modern societies and working of economies. In

resource-rich countries, mining offers great economic opportunities. Nevertheless, the mining

process poses problems and threats for human and environmental well-being. One of these

countries major problems is the management of mining so that sustainable development

contributes rather than endangers to it. Mining management at all levels, from study to mine

closure, requires serious social and environmental impacts. Mining legal and contractual systems

are often defined with little regard to ecological sustainability and the well-being of communities

exaggerated. Local communities and indigenous people frequently do not have the right to

participate in decisions on mining projects (Dashwood, 2012). Although many countries have

implemented legislation on the assessment and closure of mines on the environment and social

impact, their implementation has been delayed. Moreover than that, the complete financial

benefits of mining often fail to be achieved by countries and communities. The prospects and

business potential arising from mining may not be used by people and local companies.

The famous scene of ‘Mining’, is probably the old western, where people blast on

mountain sides, tunnel through the Earth, or pan at the riverbanks for gold. The mine has a few

images. One well established scene is from the Old West, where prospects blow up the sides of

the mountains, wind tunnels or pots of gold at the banks of a river. Another one is the

environmental consequences of acid mine drainage from older mining mines which have not

benefited from contemporary management and technology (Esteves, Franks & Vanclay, 2012).

Mining has a common view of the environment. Few non-industry individuals know about

current mining activities and related business, climate and public policy concerns. Or how

mining companies adapt to the environmental challenges of today. The extraction of mineral oil

Answer- 3

Minerals and metals are important to modern societies and working of economies. In

resource-rich countries, mining offers great economic opportunities. Nevertheless, the mining

process poses problems and threats for human and environmental well-being. One of these

countries major problems is the management of mining so that sustainable development

contributes rather than endangers to it. Mining management at all levels, from study to mine

closure, requires serious social and environmental impacts. Mining legal and contractual systems

are often defined with little regard to ecological sustainability and the well-being of communities

exaggerated. Local communities and indigenous people frequently do not have the right to

participate in decisions on mining projects (Dashwood, 2012). Although many countries have

implemented legislation on the assessment and closure of mines on the environment and social

impact, their implementation has been delayed. Moreover than that, the complete financial

benefits of mining often fail to be achieved by countries and communities. The prospects and

business potential arising from mining may not be used by people and local companies.

The famous scene of ‘Mining’, is probably the old western, where people blast on

mountain sides, tunnel through the Earth, or pan at the riverbanks for gold. The mine has a few

images. One well established scene is from the Old West, where prospects blow up the sides of

the mountains, wind tunnels or pots of gold at the banks of a river. Another one is the

environmental consequences of acid mine drainage from older mining mines which have not

benefited from contemporary management and technology (Esteves, Franks & Vanclay, 2012).

Mining has a common view of the environment. Few non-industry individuals know about

current mining activities and related business, climate and public policy concerns. Or how

mining companies adapt to the environmental challenges of today. The extraction of mineral oil

8REPORT

is just one step in a complicated and time-consuming process of mineral production. The

exploration and construction of the mine is born. The mining and profit will be pursued and the

mine closure and reconstruction will end. To order to be viable and profitable, a mining business

must conduct all mining activities.

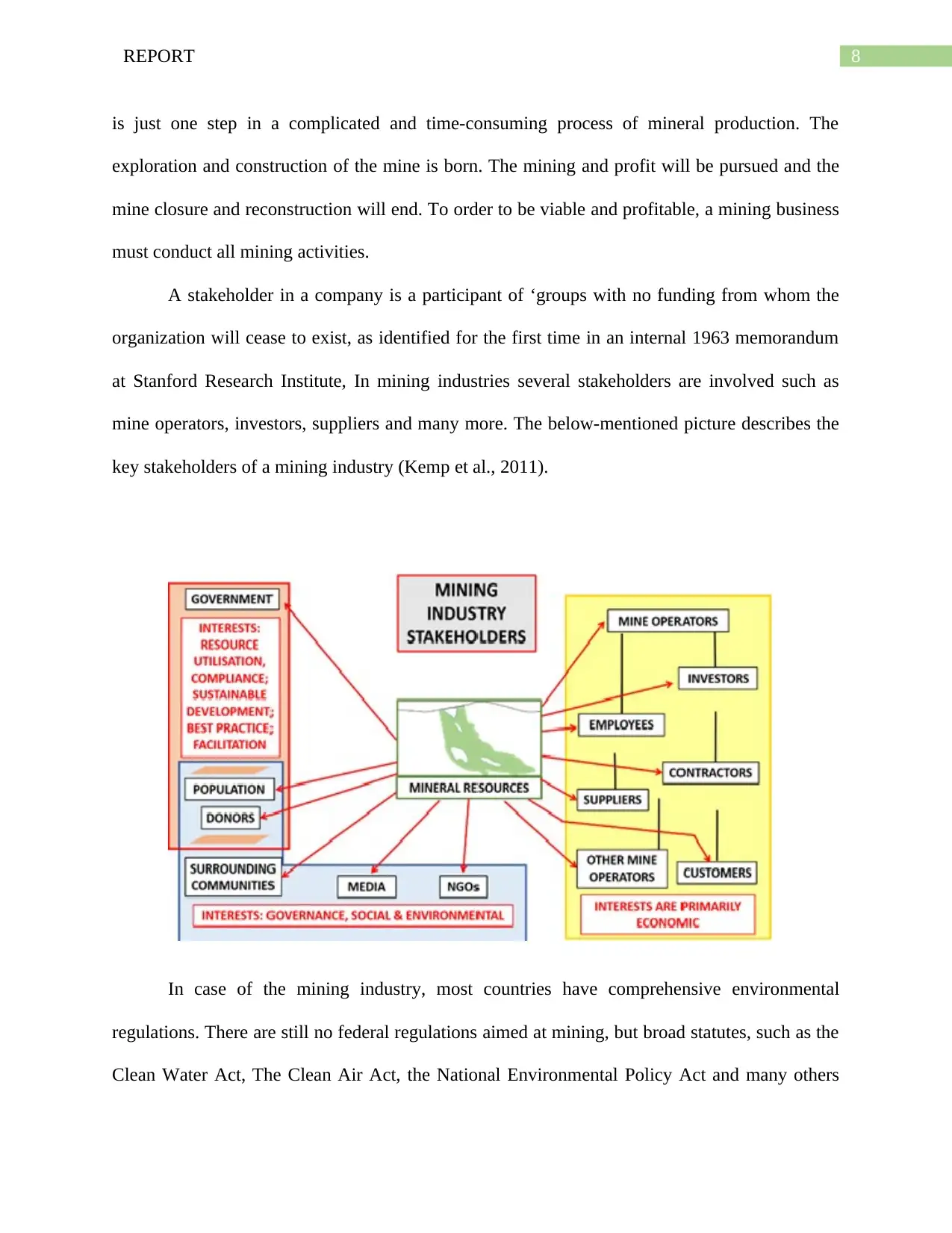

A stakeholder in a company is a participant of ‘groups with no funding from whom the

organization will cease to exist, as identified for the first time in an internal 1963 memorandum

at Stanford Research Institute, In mining industries several stakeholders are involved such as

mine operators, investors, suppliers and many more. The below-mentioned picture describes the

key stakeholders of a mining industry (Kemp et al., 2011).

In case of the mining industry, most countries have comprehensive environmental

regulations. There are still no federal regulations aimed at mining, but broad statutes, such as the

Clean Water Act, The Clean Air Act, the National Environmental Policy Act and many others

is just one step in a complicated and time-consuming process of mineral production. The

exploration and construction of the mine is born. The mining and profit will be pursued and the

mine closure and reconstruction will end. To order to be viable and profitable, a mining business

must conduct all mining activities.

A stakeholder in a company is a participant of ‘groups with no funding from whom the

organization will cease to exist, as identified for the first time in an internal 1963 memorandum

at Stanford Research Institute, In mining industries several stakeholders are involved such as

mine operators, investors, suppliers and many more. The below-mentioned picture describes the

key stakeholders of a mining industry (Kemp et al., 2011).

In case of the mining industry, most countries have comprehensive environmental

regulations. There are still no federal regulations aimed at mining, but broad statutes, such as the

Clean Water Act, The Clean Air Act, the National Environmental Policy Act and many others

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

9REPORT

are applicable to mining. Moreover, through its comprehensive environmental response and

compensation, the Federal Government addressed the clean-up of historical waste mining. The

engagement of stakeholders is specifically relevant under the mining industry, by which a

closeness has been provided along with effect on local communities by the use of natural

resources like land, water and energy. Efficient involvement of various stakeholder can enhance

the understanding of a company in regards to it effectual activities, by optimizing investment

advantages while reducing costs (Franks & Vanclay, 2013). Relationships with community

members can improve confidence and promote backing for a local project. Many authors are of

the view that internal stakeholders, such as employees, business partners and contractors are

those stakeholders who are ignored often but it is important to communicate with them on a

regular basis. Such associations are often the main point of contact with members of the

community, many of which live in the community itself. However, when enterprises have a

positive relation to these groups, they not only advance their direct relations, but they can have a

broader effect on the insight of the company within the community. In order to accept a mining

project, the communities need to observe the probable welfares of the project as being greater

than their risks. Companies can help this by engage community members, know their concerns

and proactively address them and build a shared vision for the long-term prospect of the

community (Prno & Slocombe, 2012).

Environmental concern and consideration is one of the key elements of a prosperous

business strategy. Given the increasing attention paid to environmental issues in mining, today

the experience of a different organization demonstrates that it is even more critical. A variety of

environmental policies are based on an environmental policy dependent upon the conditions of

are applicable to mining. Moreover, through its comprehensive environmental response and

compensation, the Federal Government addressed the clean-up of historical waste mining. The

engagement of stakeholders is specifically relevant under the mining industry, by which a

closeness has been provided along with effect on local communities by the use of natural

resources like land, water and energy. Efficient involvement of various stakeholder can enhance

the understanding of a company in regards to it effectual activities, by optimizing investment

advantages while reducing costs (Franks & Vanclay, 2013). Relationships with community

members can improve confidence and promote backing for a local project. Many authors are of

the view that internal stakeholders, such as employees, business partners and contractors are

those stakeholders who are ignored often but it is important to communicate with them on a

regular basis. Such associations are often the main point of contact with members of the

community, many of which live in the community itself. However, when enterprises have a

positive relation to these groups, they not only advance their direct relations, but they can have a

broader effect on the insight of the company within the community. In order to accept a mining

project, the communities need to observe the probable welfares of the project as being greater

than their risks. Companies can help this by engage community members, know their concerns

and proactively address them and build a shared vision for the long-term prospect of the

community (Prno & Slocombe, 2012).

Environmental concern and consideration is one of the key elements of a prosperous

business strategy. Given the increasing attention paid to environmental issues in mining, today

the experience of a different organization demonstrates that it is even more critical. A variety of

environmental policies are based on an environmental policy dependent upon the conditions of

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

10REPORT

the nations and locations in which they reside as a result of lawful obedience, regulatory

obedience and permission (Deegan & Blomquist, 2006).

Efforts should be made throughout a mining lifetime and the entire value chain of mining

to alleviate environmental impacts, safeguard human rights, promote social inclusion and

increase mining assistances. In view of the different mine-life phases: mining explorations, mine

creation, mining operations and mining closure, the effects of mining can be understood in a

better way. Therefore, a ‘Mine Life’ approach allows concrete actions to be established that

governments and other stakeholders may take at various mining periods (Dobele et al., 2014).

While entering into mining agreements, particular attention shall be paid to clauses on the

mitigation of the environmental impact, mine closure, relocation, local content and employment.

Several prescriptive approaches has been used by the government conventionally, which is also

called as technological standards in order to regulate environment must specify that concrete

technologies are to be used to mitigate pollution. Once contracts for mining are concluded,

governments will pay particular attention to provisions relating to mitigation, closure of mining

mine, relocation, local content and jobs. Specific community planning agreements in this respect

can also be beneficial (Pellegrino & Lodhia, 2012).

Nowadays, environmental audit is performed for the purpose of providing thorough

information on ecological presentation and obedience with regulations, effect of mitigation plans

and potential liabilities. Environmental assessments do not substitute for oversight of the

environment. Internal audits and external audits are included in this concept. Internal audits shall

also be called first-party audits, which are performed or contracted by the mining company.

External audits include government, creditor, or depositor audits which are performed by the

the nations and locations in which they reside as a result of lawful obedience, regulatory

obedience and permission (Deegan & Blomquist, 2006).

Efforts should be made throughout a mining lifetime and the entire value chain of mining

to alleviate environmental impacts, safeguard human rights, promote social inclusion and

increase mining assistances. In view of the different mine-life phases: mining explorations, mine

creation, mining operations and mining closure, the effects of mining can be understood in a

better way. Therefore, a ‘Mine Life’ approach allows concrete actions to be established that

governments and other stakeholders may take at various mining periods (Dobele et al., 2014).

While entering into mining agreements, particular attention shall be paid to clauses on the

mitigation of the environmental impact, mine closure, relocation, local content and employment.

Several prescriptive approaches has been used by the government conventionally, which is also

called as technological standards in order to regulate environment must specify that concrete

technologies are to be used to mitigate pollution. Once contracts for mining are concluded,

governments will pay particular attention to provisions relating to mitigation, closure of mining

mine, relocation, local content and jobs. Specific community planning agreements in this respect

can also be beneficial (Pellegrino & Lodhia, 2012).

Nowadays, environmental audit is performed for the purpose of providing thorough

information on ecological presentation and obedience with regulations, effect of mitigation plans

and potential liabilities. Environmental assessments do not substitute for oversight of the

environment. Internal audits and external audits are included in this concept. Internal audits shall

also be called first-party audits, which are performed or contracted by the mining company.

External audits include government, creditor, or depositor audits which are performed by the

11REPORT

second party, and independent audits conducted by third parties (Govindan, Kannan & Shankar,

2014).

The Environment Policy of the company generally dictates that its functions simply

comply with current norms. The operations must illustrate best current practice for minimizing

and eliminating adverse environmental impacts where possible. Appropriate environmental

concern and consideration is one of the key elements of any effective business plan. In view of

the cumulative attention paid in mining to environmental issues, it is even more important today

(Mutti et al., 2012). Finally, it can be concluded that the environment policy of the company

strives to strike a balance between the metals requirement of society with an eco-friendly

approach. Earning profit is important for the advancement of the business as well as the society

but it is also important to preserve the various environmental resources.

second party, and independent audits conducted by third parties (Govindan, Kannan & Shankar,

2014).

The Environment Policy of the company generally dictates that its functions simply

comply with current norms. The operations must illustrate best current practice for minimizing

and eliminating adverse environmental impacts where possible. Appropriate environmental

concern and consideration is one of the key elements of any effective business plan. In view of

the cumulative attention paid in mining to environmental issues, it is even more important today

(Mutti et al., 2012). Finally, it can be concluded that the environment policy of the company

strives to strike a balance between the metals requirement of society with an eco-friendly

approach. Earning profit is important for the advancement of the business as well as the society

but it is also important to preserve the various environmental resources.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 14

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.