Leadership Capabilities and Transition Strategies: An Essay Analysis

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/17

|30

|12000

|328

Essay

AI Summary

This essay examines leadership capabilities and transition strategies for individual improvement within a chosen workplace or organization. It explores self-management and relationship-building aspects of leadership, evaluating them within a specific context. The essay then delves into the implementation of transition strategies designed to enhance individual leadership abilities. The structure includes an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion, with attention given to English language proficiency, grammar, and proper citation using APA referencing. The assignment focuses on providing a comprehensive analysis of leadership, offering practical strategies for personal and professional development in a business setting. It evaluates how leaders can adapt to changes in consumer behavior and business trading patterns. The essay also uses the iceberg model of virtues to illustrate the importance of deeper levels of cultural change in business decision-making.

Leadership for the

Sustainability Transition

WILLIAM THROOP AND MATT MAYBERRY

ABSTRACT

Society is looking to business to help solve our most com-

plex environmental and social challenges as we transition

to a more sustainable economic model. However, without

a fundamental shift in the dominant virtues that have

influenced business decision making for the past 150

years to a new set of dominant virtues that better fit

today’s environment,it will be more natural for compa-

nies to resist the necessary changes than to find the

opportunities within them. We use the term “virtues”

quite broadly to describe dispositions to think, feel and

act in skillful ways that promote the aims of a practice.

Addressing this deeper levelof cultural change is essen-

tial to cultivating new instinctive behavior in business

decision making. In this article, we describe five clusters

of virtues that facilitate effective response to the transition

challenges—adaptive, collaborative, frugality, humility,

and systems virtues. To illustrate the application of these

virtues, we present a detailed case study of Green Moun-

tain Power, a Vermont electric utility that has embraced

the shift to renewable energy and smart-grid technology,

and is creating an innovative business model that is

William Throop is a Professor of Philosophy and Environmental Studies at the Green Mountain

College, Poultney, VT. E-mail: throopw@greenmtn.edu.Matt Mayberry is President of Whole-

Works, Manchester, VT. E-mail: mayberry@wholeworks.com.

VC 2017 W. Michael Hoffman Center for Business Ethics at Bentley University. Published by

Wiley Periodicals, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA, and 9600 Garsington

Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK.

Business and Society Review 122:2 221–250

bs_bs_banner

Sustainability Transition

WILLIAM THROOP AND MATT MAYBERRY

ABSTRACT

Society is looking to business to help solve our most com-

plex environmental and social challenges as we transition

to a more sustainable economic model. However, without

a fundamental shift in the dominant virtues that have

influenced business decision making for the past 150

years to a new set of dominant virtues that better fit

today’s environment,it will be more natural for compa-

nies to resist the necessary changes than to find the

opportunities within them. We use the term “virtues”

quite broadly to describe dispositions to think, feel and

act in skillful ways that promote the aims of a practice.

Addressing this deeper levelof cultural change is essen-

tial to cultivating new instinctive behavior in business

decision making. In this article, we describe five clusters

of virtues that facilitate effective response to the transition

challenges—adaptive, collaborative, frugality, humility,

and systems virtues. To illustrate the application of these

virtues, we present a detailed case study of Green Moun-

tain Power, a Vermont electric utility that has embraced

the shift to renewable energy and smart-grid technology,

and is creating an innovative business model that is

William Throop is a Professor of Philosophy and Environmental Studies at the Green Mountain

College, Poultney, VT. E-mail: throopw@greenmtn.edu.Matt Mayberry is President of Whole-

Works, Manchester, VT. E-mail: mayberry@wholeworks.com.

VC 2017 W. Michael Hoffman Center for Business Ethics at Bentley University. Published by

Wiley Periodicals, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA, and 9600 Garsington

Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK.

Business and Society Review 122:2 221–250

bs_bs_banner

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

disrupting the industry. After distilling key findings from

the case, we outline an approach to leadership develop-

ment that can help accelerate the infusion of transitional

virtues across an organization.

LEADERSHIP FOR THE SUSTAINABILITY TRANSITION

B usiness is in the midst of a great transition—one similar in

scope to the industrial and digital revolutions. This sus-

tainability transition is driven in part by the need to adjust

to planetary limits, but also by opportunities presented by an

evolving globaleconomic system that is highly sensitive to disrup-

tive social dynamics. Business leaders face a complex tangle of eco-

nomic, social, and environmental challenges that require deep

changes in operations and organizational culture. To use Ronald

Heifetz’ language, today’s greatest social challenges are not so

much technical problems as they are adaptive challenges where

the “problem definition is not clear-cut, and technical fixes are not

available.”1 For businesses to flourish, leaders will need to behave

in new ways consistent with a finite, complex, uncertain, changing,

collaborative, connected, and caring world.

This will require a shift in the dominant virtues that characterize

most corporate cultures today. We use the term “virtues” quite

broadly to describe dispositions to think, feel and act in skillful

ways that promote the aims of a practice. Although the term

“virtue” sometimes connotes only moral habits, we use it in Aristo-

tle’s sense which focuses on cognitive/behavioral skills rooted in a

deep understanding of a practice. Companies often identify core

competencies they want employees to have. Competency models

used in talent developmentrepresent a model of effective perfor-

mance that helps an organization achieve its goals.2 If competen-

cies are interpreted as involving more than discrete skills, and

including patterns of thought, feeling, and motivation embedded in

enduring character traits, then competencies approximate virtues.

Virtues, however, generally have a broader range of applicability

(across a range of business and personal contexts), they tend to be

mutually reinforcing and embedded in a worldview. Aristotle

argued that manifesting the excellences associated with being

222 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

the case, we outline an approach to leadership develop-

ment that can help accelerate the infusion of transitional

virtues across an organization.

LEADERSHIP FOR THE SUSTAINABILITY TRANSITION

B usiness is in the midst of a great transition—one similar in

scope to the industrial and digital revolutions. This sus-

tainability transition is driven in part by the need to adjust

to planetary limits, but also by opportunities presented by an

evolving globaleconomic system that is highly sensitive to disrup-

tive social dynamics. Business leaders face a complex tangle of eco-

nomic, social, and environmental challenges that require deep

changes in operations and organizational culture. To use Ronald

Heifetz’ language, today’s greatest social challenges are not so

much technical problems as they are adaptive challenges where

the “problem definition is not clear-cut, and technical fixes are not

available.”1 For businesses to flourish, leaders will need to behave

in new ways consistent with a finite, complex, uncertain, changing,

collaborative, connected, and caring world.

This will require a shift in the dominant virtues that characterize

most corporate cultures today. We use the term “virtues” quite

broadly to describe dispositions to think, feel and act in skillful

ways that promote the aims of a practice. Although the term

“virtue” sometimes connotes only moral habits, we use it in Aristo-

tle’s sense which focuses on cognitive/behavioral skills rooted in a

deep understanding of a practice. Companies often identify core

competencies they want employees to have. Competency models

used in talent developmentrepresent a model of effective perfor-

mance that helps an organization achieve its goals.2 If competen-

cies are interpreted as involving more than discrete skills, and

including patterns of thought, feeling, and motivation embedded in

enduring character traits, then competencies approximate virtues.

Virtues, however, generally have a broader range of applicability

(across a range of business and personal contexts), they tend to be

mutually reinforcing and embedded in a worldview. Aristotle

argued that manifesting the excellences associated with being

222 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

human—the virtues—was the road to flourishing.3 We have found

that if the virtues embedded in an organizational culture fits its

context, then they contribute greatly to its flourishing. If not, then

even the best leaders and innovative strategies are often thwarted

by virtues out of sync with the context.

In this article, we briefly summarize some major challenges busi-

ness faces and then describe five clusters ofvirtues that facilitate

effective response to the challenges.We argue that making these

virtue shifts is essential work for business leaders because it will

be required to fully grasp the opportunities of this time and to

avoid missteps, as is illustrated in a detailed case study. The vir-

tues are not novel, though they are underemphasized. The changes

we recommend are occurring in some businesses and the transi-

tional virtues can be cultivated by any organization through delib-

erate practice and reflection. Such training requires a safe learning

environment to overcome performance anxiety, and sufficient time

for the changes to become internalized.4 In our conclusion, we out-

line an approach to leadership development that can infuse transi-

tional virtues across the organization.

THE CHALLENGES OF THE TRANSITION

The momentum behind the sustainability transition is building

with the agreement at COP 21, the new United Nations Sustainable

Development Goals, and the recent Encyclical Letter by Pope Fran-

cis.5 It is driven by a growing understanding of the challenges we

must meet. Although each business faces challenges specific to its

history and sector, we see common themes across sectors that

stem from the larger scale social, economic, and environmental

contexts in which business operates.

Environmental Challenges

In the last 50 years, we have seen a tremendous increase in human

impacts on ecosystems; Steffen et al.6 have called this the great

acceleration. Climate change and human population growth are

the trump cards in this process because of their pervasive impact

on the ecological services that support society. In this context,

firms must be more sensitive to the cumulative impacts of their

223THROOP AND MAYBERRY

that if the virtues embedded in an organizational culture fits its

context, then they contribute greatly to its flourishing. If not, then

even the best leaders and innovative strategies are often thwarted

by virtues out of sync with the context.

In this article, we briefly summarize some major challenges busi-

ness faces and then describe five clusters ofvirtues that facilitate

effective response to the challenges.We argue that making these

virtue shifts is essential work for business leaders because it will

be required to fully grasp the opportunities of this time and to

avoid missteps, as is illustrated in a detailed case study. The vir-

tues are not novel, though they are underemphasized. The changes

we recommend are occurring in some businesses and the transi-

tional virtues can be cultivated by any organization through delib-

erate practice and reflection. Such training requires a safe learning

environment to overcome performance anxiety, and sufficient time

for the changes to become internalized.4 In our conclusion, we out-

line an approach to leadership development that can infuse transi-

tional virtues across the organization.

THE CHALLENGES OF THE TRANSITION

The momentum behind the sustainability transition is building

with the agreement at COP 21, the new United Nations Sustainable

Development Goals, and the recent Encyclical Letter by Pope Fran-

cis.5 It is driven by a growing understanding of the challenges we

must meet. Although each business faces challenges specific to its

history and sector, we see common themes across sectors that

stem from the larger scale social, economic, and environmental

contexts in which business operates.

Environmental Challenges

In the last 50 years, we have seen a tremendous increase in human

impacts on ecosystems; Steffen et al.6 have called this the great

acceleration. Climate change and human population growth are

the trump cards in this process because of their pervasive impact

on the ecological services that support society. In this context,

firms must be more sensitive to the cumulative impacts of their

223THROOP AND MAYBERRY

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

sector on resource availability and the capacity of systems to

absorb waste, which in turn increase supply chain risks and

threaten the economic bottom line.

A business’s specific environmental challenges depend on the

dynamics of the bioregions in which it operates, and may include:

carbon risk, sea level rise, super storms, flooding, availability of

clean water, lack of pollinators, catastrophic fire, and so on. 7 The

risks of such challenges affect business stakeholders—consumers,

investors, and employees—which will affect operations and sales.

The acceleration of these challenges also destabilizes the regulatory

environment, making it harder for firms to plan strategically. The

narrative of our exceeding environmental limits is pervasive among

a growing subset of the population, especially the young, which

fuels the pursuit of sustainability and resilience.

Social Challenges

Businesses are operating in an increasingly unstable social climate.

They are embedded in a 24/7 decentralized media environment

which has an insatiable demand for controversy. Media must create

news out of whatever occurs,and stimulate strong reactions that

fuel increased interestin analysis and updates. One result is an

amplification of our differences.Political polarization is just one

manifestation ofthe way our media make it harder for us to solve

problems together and erode trust in the social institutions like busi-

ness, science,and government.8 Another is rapid dissemination of

information on social media which often focuses on latest trends

rather than historical context and contributes to information over-

load. The latter makes it increasingly hard for businesses to break

through the media clutter to create an enduring brand identity.

As the stresses associated with the great acceleration magnify,

we see more armed conflict around the globe, escalating anger

among the disenfranchised,increased racial tensions, and declin-

ing social capital, all of which increase supply chain risk in a glob-

alized economy. In the political sphere, we see poll-driven

leadership, lack of political participation, intolerance of complexity

and nuance, over-regulation, and an adversarial approach to

problem-solving.These all contribute to the failure of government

to address our challenges. Businesses must also deal with

224 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

absorb waste, which in turn increase supply chain risks and

threaten the economic bottom line.

A business’s specific environmental challenges depend on the

dynamics of the bioregions in which it operates, and may include:

carbon risk, sea level rise, super storms, flooding, availability of

clean water, lack of pollinators, catastrophic fire, and so on. 7 The

risks of such challenges affect business stakeholders—consumers,

investors, and employees—which will affect operations and sales.

The acceleration of these challenges also destabilizes the regulatory

environment, making it harder for firms to plan strategically. The

narrative of our exceeding environmental limits is pervasive among

a growing subset of the population, especially the young, which

fuels the pursuit of sustainability and resilience.

Social Challenges

Businesses are operating in an increasingly unstable social climate.

They are embedded in a 24/7 decentralized media environment

which has an insatiable demand for controversy. Media must create

news out of whatever occurs,and stimulate strong reactions that

fuel increased interestin analysis and updates. One result is an

amplification of our differences.Political polarization is just one

manifestation ofthe way our media make it harder for us to solve

problems together and erode trust in the social institutions like busi-

ness, science,and government.8 Another is rapid dissemination of

information on social media which often focuses on latest trends

rather than historical context and contributes to information over-

load. The latter makes it increasingly hard for businesses to break

through the media clutter to create an enduring brand identity.

As the stresses associated with the great acceleration magnify,

we see more armed conflict around the globe, escalating anger

among the disenfranchised,increased racial tensions, and declin-

ing social capital, all of which increase supply chain risk in a glob-

alized economy. In the political sphere, we see poll-driven

leadership, lack of political participation, intolerance of complexity

and nuance, over-regulation, and an adversarial approach to

problem-solving.These all contribute to the failure of government

to address our challenges. Businesses must also deal with

224 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

increased diversity in the workplace, which can contribute greater

innovation, but which can also make effective teamwork more diffi-

cult. Within these challenges lie well documented opportunities;

movements like creation ofshared value,9 and base of pyramid10

contribute to effective community development and local increases

in trust and associations.11

Economic Challenges

The above socialand environmental challenges increase the likeli-

hood of economic turbulence. Our economic expectations are con-

ditioned by 75 years of extraordinary growth, which will be hard to

sustain in the current climate. Our dominant economic story

remains one of material progress, but many are losing confidence

in rising standards of living.12 Increasing inequality, global interde-

pendence, an aging population, and the difficulty of achieving high

employment levels in low growth economies underlie the fragility of

our economic situation.

For many businesses, this economic turbulence is magnified by

the increasing speed of disruptive innovations, regulatory instabili-

ty, and shifts in global supply chains. Some are also affected by the

high cost of providing worker benefits, high employee turnover

rates, and the declining proportion of consumers in the United

States with discretionary income. Despite living in a period of sig-

nificant economic growth, many people feel economically fragile

and powerless. This affects employee engagementand the talent

pool available to business.

Amidst such challenges, there is a great deal of opportunity—new

markets to be tapped, especially in developing countries; more demand

for waste reducing products and sustainability branding;increased

investment in infrastructure to handle challenges, and a high

demand/payoff for innovative solutions. But are businesses ready to

grasp the opportunities that the transition to sustainability holds?

FLOURISHING AMIDST THE CHALLENGES

Business could be the most potent force helping societies navigate

the transition, but without a fundamental shift in organizational

culture, it will be more natural for companies to resist the

225THROOP AND MAYBERRY

innovation, but which can also make effective teamwork more diffi-

cult. Within these challenges lie well documented opportunities;

movements like creation ofshared value,9 and base of pyramid10

contribute to effective community development and local increases

in trust and associations.11

Economic Challenges

The above socialand environmental challenges increase the likeli-

hood of economic turbulence. Our economic expectations are con-

ditioned by 75 years of extraordinary growth, which will be hard to

sustain in the current climate. Our dominant economic story

remains one of material progress, but many are losing confidence

in rising standards of living.12 Increasing inequality, global interde-

pendence, an aging population, and the difficulty of achieving high

employment levels in low growth economies underlie the fragility of

our economic situation.

For many businesses, this economic turbulence is magnified by

the increasing speed of disruptive innovations, regulatory instabili-

ty, and shifts in global supply chains. Some are also affected by the

high cost of providing worker benefits, high employee turnover

rates, and the declining proportion of consumers in the United

States with discretionary income. Despite living in a period of sig-

nificant economic growth, many people feel economically fragile

and powerless. This affects employee engagementand the talent

pool available to business.

Amidst such challenges, there is a great deal of opportunity—new

markets to be tapped, especially in developing countries; more demand

for waste reducing products and sustainability branding;increased

investment in infrastructure to handle challenges, and a high

demand/payoff for innovative solutions. But are businesses ready to

grasp the opportunities that the transition to sustainability holds?

FLOURISHING AMIDST THE CHALLENGES

Business could be the most potent force helping societies navigate

the transition, but without a fundamental shift in organizational

culture, it will be more natural for companies to resist the

225THROOP AND MAYBERRY

necessary changes than to find the opportunities within them.

When the virtues that dominate a business fail to align with the

cultural context, leaders typically act in intuitive but counterpro-

ductive ways. Our default responses can be overridden, but it takes

significant conscious effort and attention, which are difficult to

muster when acting under pressure.

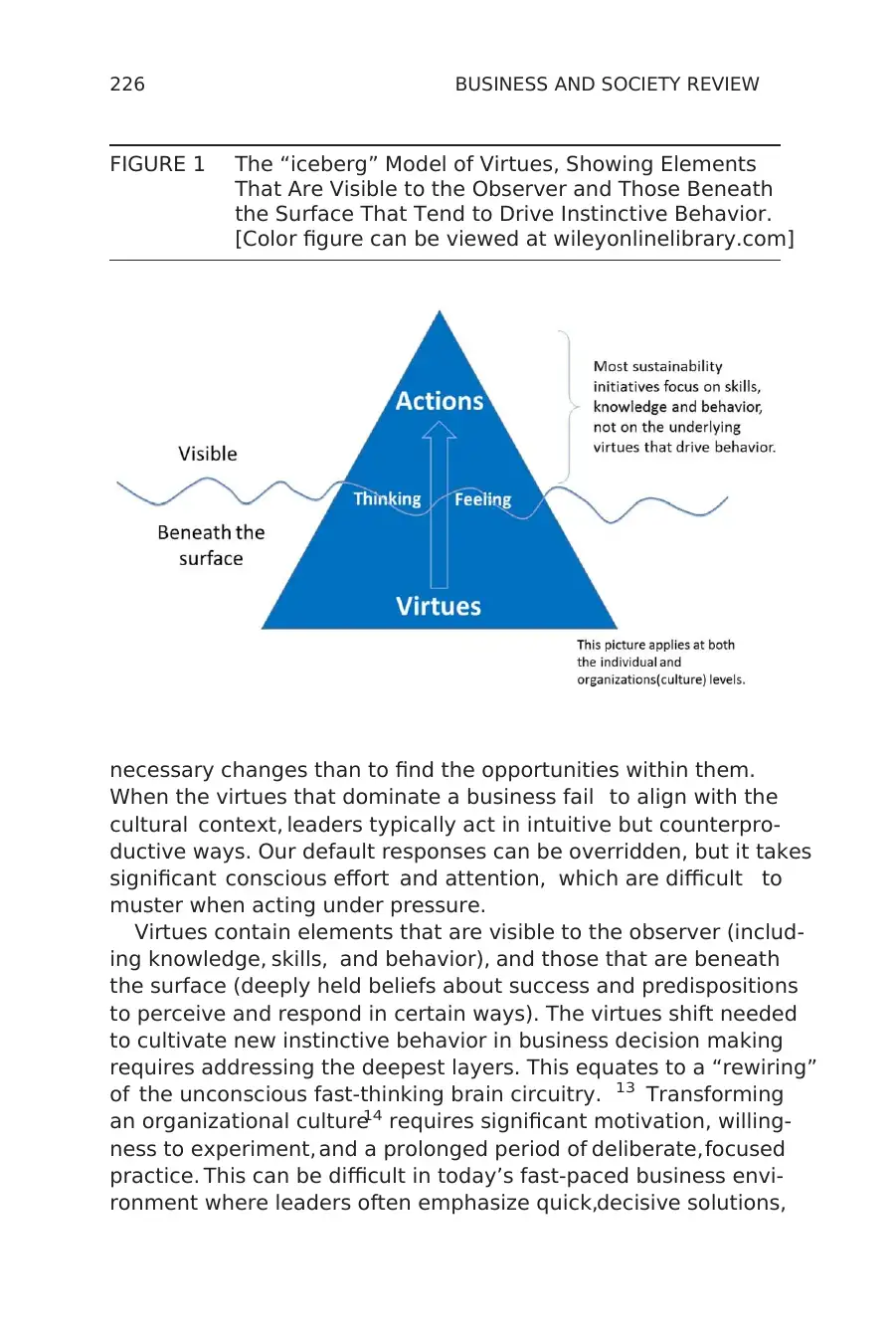

Virtues contain elements that are visible to the observer (includ-

ing knowledge, skills, and behavior), and those that are beneath

the surface (deeply held beliefs about success and predispositions

to perceive and respond in certain ways). The virtues shift needed

to cultivate new instinctive behavior in business decision making

requires addressing the deepest layers. This equates to a “rewiring”

of the unconscious fast-thinking brain circuitry. 13 Transforming

an organizational culture14 requires significant motivation, willing-

ness to experiment, and a prolonged period of deliberate,focused

practice. This can be difficult in today’s fast-paced business envi-

ronment where leaders often emphasize quick,decisive solutions,

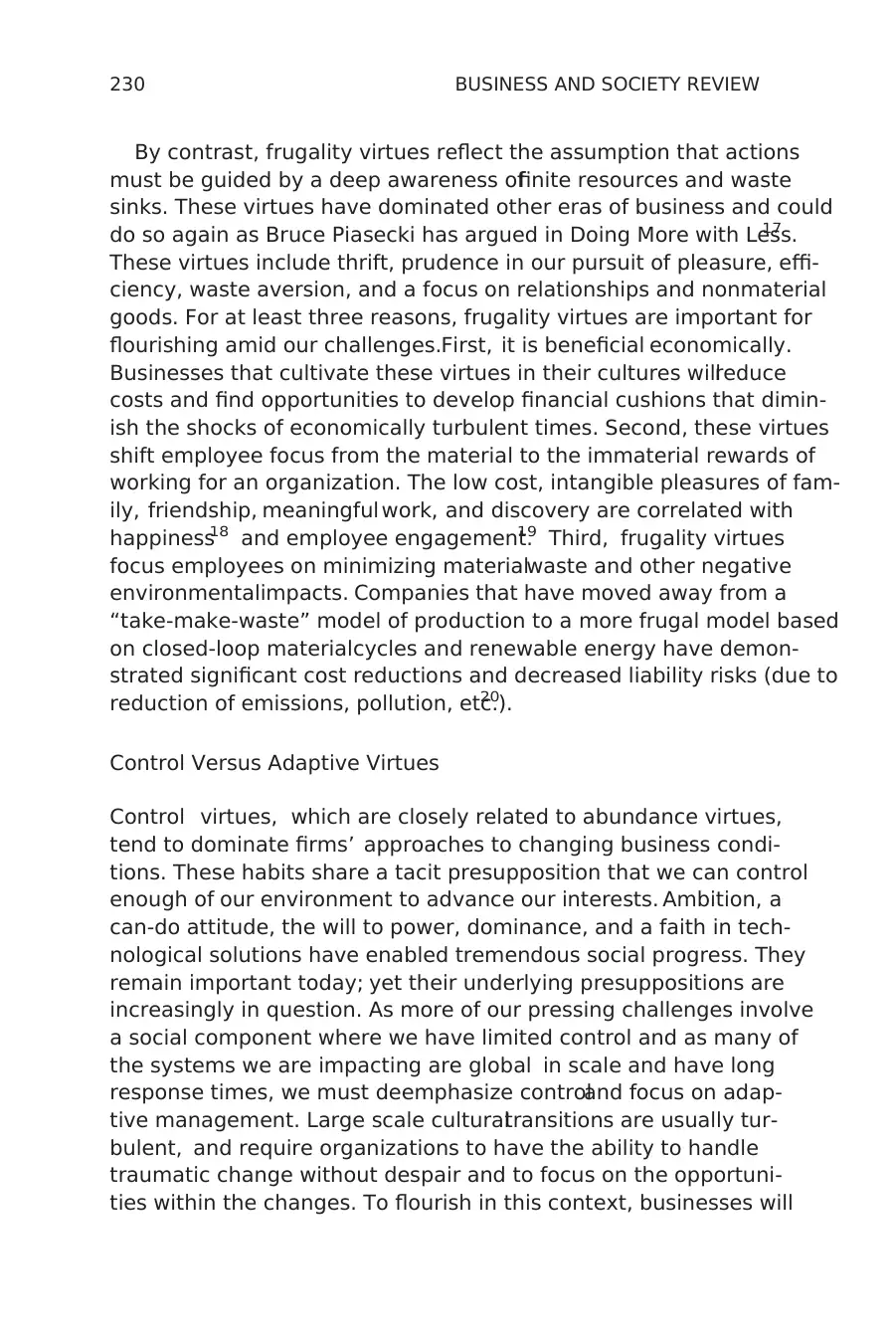

FIGURE 1 The “iceberg” Model of Virtues, Showing Elements

That Are Visible to the Observer and Those Beneath

the Surface That Tend to Drive Instinctive Behavior.

[Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

226 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

When the virtues that dominate a business fail to align with the

cultural context, leaders typically act in intuitive but counterpro-

ductive ways. Our default responses can be overridden, but it takes

significant conscious effort and attention, which are difficult to

muster when acting under pressure.

Virtues contain elements that are visible to the observer (includ-

ing knowledge, skills, and behavior), and those that are beneath

the surface (deeply held beliefs about success and predispositions

to perceive and respond in certain ways). The virtues shift needed

to cultivate new instinctive behavior in business decision making

requires addressing the deepest layers. This equates to a “rewiring”

of the unconscious fast-thinking brain circuitry. 13 Transforming

an organizational culture14 requires significant motivation, willing-

ness to experiment, and a prolonged period of deliberate,focused

practice. This can be difficult in today’s fast-paced business envi-

ronment where leaders often emphasize quick,decisive solutions,

FIGURE 1 The “iceberg” Model of Virtues, Showing Elements

That Are Visible to the Observer and Those Beneath

the Surface That Tend to Drive Instinctive Behavior.

[Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

226 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

imposed from the top to achieve immediate results. Given those

instincts, it can be difficult to muster the required patience and

perseverance needed to unlearn old behaviors and establish new

ones across the organization.

An illustration of this challenge is the difficulty many U.S. firms

have had in adopting TQM and lean production principles in recent

decades.15 Thousands of executives toured Toyota plants each year

hoping to learn the secrets of the Toyota Production System (TPS).

What many saw during those tours were the visible elements of

Toyota’s culture, the activities on the shop floor, and the visual

management tools such as the andon lights and kanban bins. In

other words, they saw the TPS as a discrete toolkit to be copied

rather than a system to be developed.When they returned home,

they attempted to install a quality culture in accelerated fashion,

rolling out company-wide quality initiatives led by scores of newly

minted lean leaders and black belts. When the tools of the TPS did

not produce the impact expected, company leaders often lost

patience, put continuous improvement on the back burner, and

reverted to tried-and-true moves, often involving restructuring.

What did they miss?

The answer lies beneath the surface of Toyota’s culture, in the

deeper layers of virtues not visible during the plant tours. They

reside in the tacit habits and patterns of thought that infuse the

Toyota Way. At the heart of the Toyota system are two pillars—con-

tinuous improvement and respect for people—that can be consid-

ered clusters of virtues. They include the deeply held belief that

progress comes from engaging people at alllevels of the organiza-

tion in ongoing problem solving and experimentation. Compared to

most U.S. firms, the role of management was fundamentally differ-

ent in the Toyota system. Managers avoided providing answers;

they were teachers. This meant being with employees on the front

lines (going to the gemba)as they worked through problems. For

U.S. managers, whose success had been based on hitting home

runs from the board room, this was an unfamiliar and uncomfort-

able role. It is easy to see why so many TQM efforts in the United

States failed, given the dominant disposition by management for

big moves and fast results.16

The TPS history illustrates how an organization’s default virtues

make it difficult to grasp the essence of new ones. Intellectual

understanding only goes so far. A deeper understanding requires

227THROOP AND MAYBERRY

instincts, it can be difficult to muster the required patience and

perseverance needed to unlearn old behaviors and establish new

ones across the organization.

An illustration of this challenge is the difficulty many U.S. firms

have had in adopting TQM and lean production principles in recent

decades.15 Thousands of executives toured Toyota plants each year

hoping to learn the secrets of the Toyota Production System (TPS).

What many saw during those tours were the visible elements of

Toyota’s culture, the activities on the shop floor, and the visual

management tools such as the andon lights and kanban bins. In

other words, they saw the TPS as a discrete toolkit to be copied

rather than a system to be developed.When they returned home,

they attempted to install a quality culture in accelerated fashion,

rolling out company-wide quality initiatives led by scores of newly

minted lean leaders and black belts. When the tools of the TPS did

not produce the impact expected, company leaders often lost

patience, put continuous improvement on the back burner, and

reverted to tried-and-true moves, often involving restructuring.

What did they miss?

The answer lies beneath the surface of Toyota’s culture, in the

deeper layers of virtues not visible during the plant tours. They

reside in the tacit habits and patterns of thought that infuse the

Toyota Way. At the heart of the Toyota system are two pillars—con-

tinuous improvement and respect for people—that can be consid-

ered clusters of virtues. They include the deeply held belief that

progress comes from engaging people at alllevels of the organiza-

tion in ongoing problem solving and experimentation. Compared to

most U.S. firms, the role of management was fundamentally differ-

ent in the Toyota system. Managers avoided providing answers;

they were teachers. This meant being with employees on the front

lines (going to the gemba)as they worked through problems. For

U.S. managers, whose success had been based on hitting home

runs from the board room, this was an unfamiliar and uncomfort-

able role. It is easy to see why so many TQM efforts in the United

States failed, given the dominant disposition by management for

big moves and fast results.16

The TPS history illustrates how an organization’s default virtues

make it difficult to grasp the essence of new ones. Intellectual

understanding only goes so far. A deeper understanding requires

227THROOP AND MAYBERRY

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

practicing the new virtues long enough until they begin to make

intuitive sense. This is why Toyota insists that new managers in

the United States spend significant time on the front lines working

within the TPS system. It takes practice to internalize the princi-

ples. We believe that a similar process will be required for organiza-

tions to fully embrace the virtue shift we are describing here. We

now explore those virtues in more detail.

VIRTUES FOR THE TRANSITION TO SUSTAINABILITY

Our identification of the virtue clusters that will enable businesses

to grasp the opportunities in the globaltransition toward sustain-

ability is guided by research into the limits which will become

increasingly important in light of our challenges. As a short hand,

we will call the virtues that businesses will increasingly need to

cultivate sustainability virtues,but these traits are much broader

than the practices traditionally associated with sustainability. To

be clear, we are not saying a virtue shift alone is sufficient to effec-

tively address the challenges. We also need new knowledge, better

technology,and probably more effective governance.We can miti-

gate our challenges with technologicaladvances and by increased

efficiency and strong leadership, but without a virtue shift, most

businesses are unlikely to flourish in the long run.

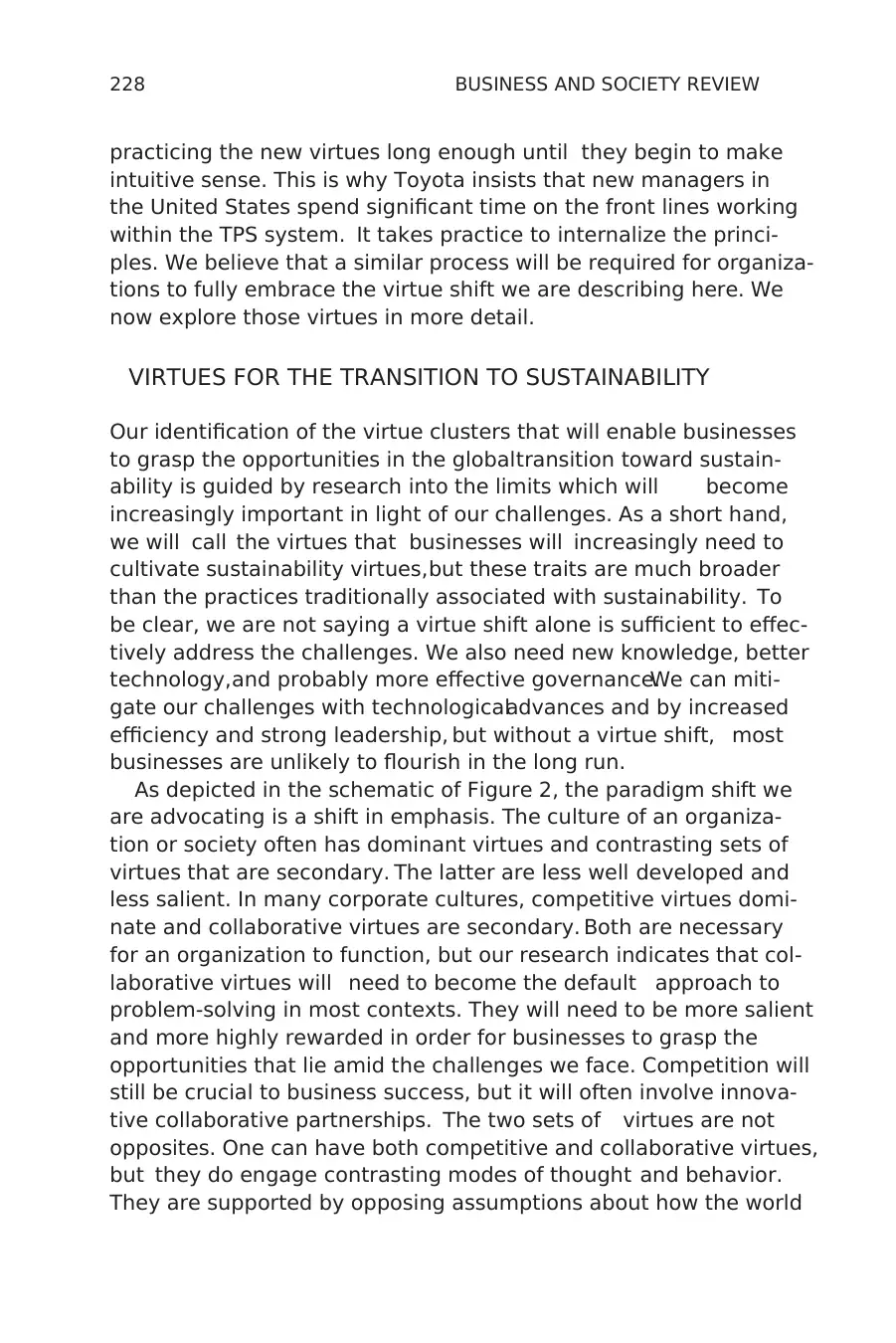

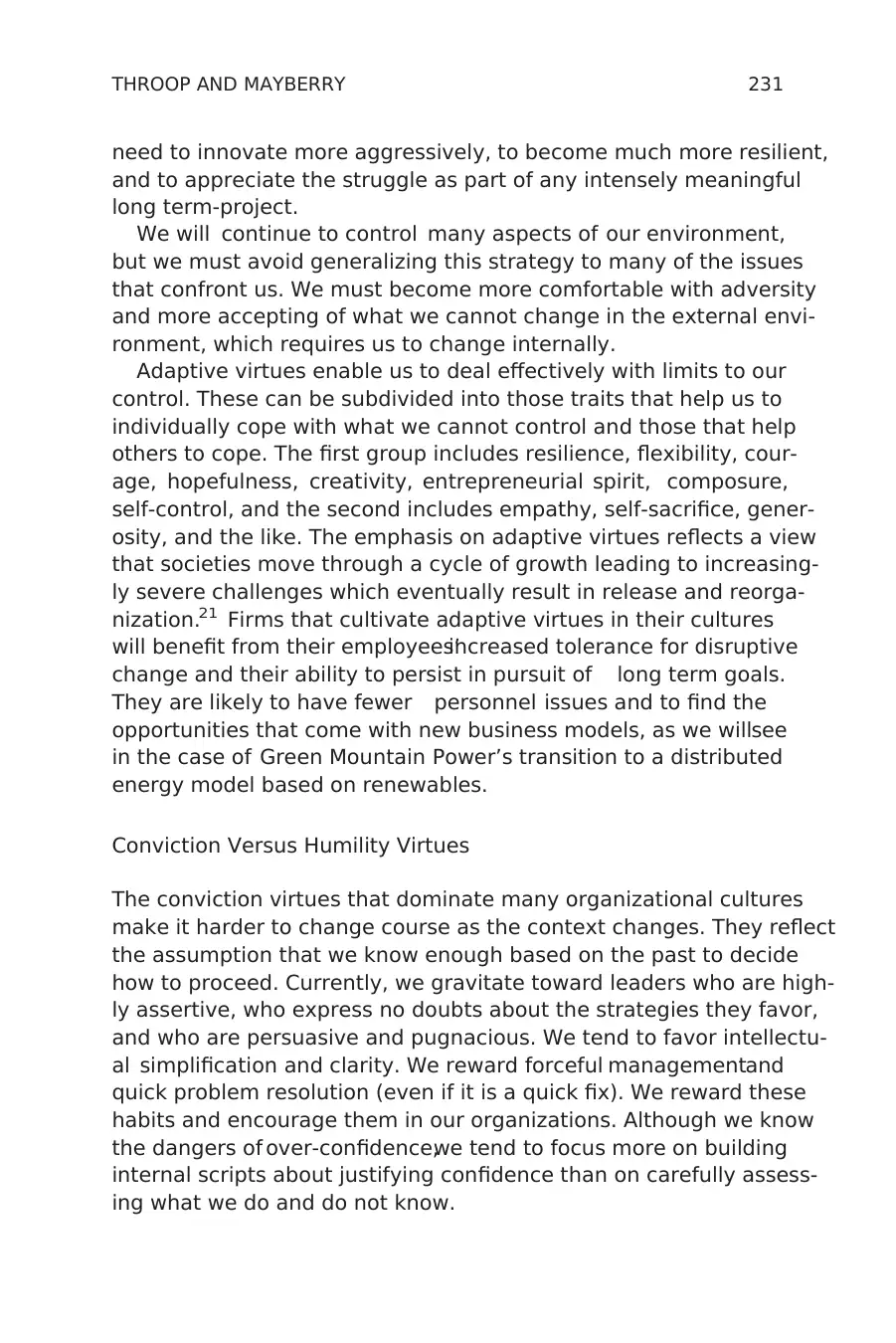

As depicted in the schematic of Figure 2, the paradigm shift we

are advocating is a shift in emphasis. The culture of an organiza-

tion or society often has dominant virtues and contrasting sets of

virtues that are secondary. The latter are less well developed and

less salient. In many corporate cultures, competitive virtues domi-

nate and collaborative virtues are secondary. Both are necessary

for an organization to function, but our research indicates that col-

laborative virtues will need to become the default approach to

problem-solving in most contexts. They will need to be more salient

and more highly rewarded in order for businesses to grasp the

opportunities that lie amid the challenges we face. Competition will

still be crucial to business success, but it will often involve innova-

tive collaborative partnerships. The two sets of virtues are not

opposites. One can have both competitive and collaborative virtues,

but they do engage contrasting modes of thought and behavior.

They are supported by opposing assumptions about how the world

228 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

intuitive sense. This is why Toyota insists that new managers in

the United States spend significant time on the front lines working

within the TPS system. It takes practice to internalize the princi-

ples. We believe that a similar process will be required for organiza-

tions to fully embrace the virtue shift we are describing here. We

now explore those virtues in more detail.

VIRTUES FOR THE TRANSITION TO SUSTAINABILITY

Our identification of the virtue clusters that will enable businesses

to grasp the opportunities in the globaltransition toward sustain-

ability is guided by research into the limits which will become

increasingly important in light of our challenges. As a short hand,

we will call the virtues that businesses will increasingly need to

cultivate sustainability virtues,but these traits are much broader

than the practices traditionally associated with sustainability. To

be clear, we are not saying a virtue shift alone is sufficient to effec-

tively address the challenges. We also need new knowledge, better

technology,and probably more effective governance.We can miti-

gate our challenges with technologicaladvances and by increased

efficiency and strong leadership, but without a virtue shift, most

businesses are unlikely to flourish in the long run.

As depicted in the schematic of Figure 2, the paradigm shift we

are advocating is a shift in emphasis. The culture of an organiza-

tion or society often has dominant virtues and contrasting sets of

virtues that are secondary. The latter are less well developed and

less salient. In many corporate cultures, competitive virtues domi-

nate and collaborative virtues are secondary. Both are necessary

for an organization to function, but our research indicates that col-

laborative virtues will need to become the default approach to

problem-solving in most contexts. They will need to be more salient

and more highly rewarded in order for businesses to grasp the

opportunities that lie amid the challenges we face. Competition will

still be crucial to business success, but it will often involve innova-

tive collaborative partnerships. The two sets of virtues are not

opposites. One can have both competitive and collaborative virtues,

but they do engage contrasting modes of thought and behavior.

They are supported by opposing assumptions about how the world

228 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

works and different models of success. Where one set is the default

approach to decision making, the contrasting set tends to be less

developed and under-represented in the culture.

Abundance Versus Frugality Virtues

We are calling a cluster of character traits associated with a focus

on material wellbeing “abundance virtues,” because their current

manifestation is based on an assumption that we can transcend

material limits and continue to grow indefinitely—that technologi-

cal innovation makes our resources abundant. These virtues

include being acquisitive, opportunistic, magnanimous, and opti-

mistic. Our tendencies to focus on size (larger is better), on materi-

al standard of living, on convenience and technologicalsolutions,

and on GDP as a measure of progress are manifestations of these

virtues. These habits have motivated us to be industrious, creative,

competitive, and specialized; they have led to tremendous material

prosperity. As population has increased, however,that prosperity

has threatened the ecosystems on which we depend.

FIGURE 2 The Shift in Dominant Virtues Needed to Align with

Today’s Business Environment.

229THROOP AND MAYBERRY

approach to decision making, the contrasting set tends to be less

developed and under-represented in the culture.

Abundance Versus Frugality Virtues

We are calling a cluster of character traits associated with a focus

on material wellbeing “abundance virtues,” because their current

manifestation is based on an assumption that we can transcend

material limits and continue to grow indefinitely—that technologi-

cal innovation makes our resources abundant. These virtues

include being acquisitive, opportunistic, magnanimous, and opti-

mistic. Our tendencies to focus on size (larger is better), on materi-

al standard of living, on convenience and technologicalsolutions,

and on GDP as a measure of progress are manifestations of these

virtues. These habits have motivated us to be industrious, creative,

competitive, and specialized; they have led to tremendous material

prosperity. As population has increased, however,that prosperity

has threatened the ecosystems on which we depend.

FIGURE 2 The Shift in Dominant Virtues Needed to Align with

Today’s Business Environment.

229THROOP AND MAYBERRY

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

By contrast, frugality virtues reflect the assumption that actions

must be guided by a deep awareness offinite resources and waste

sinks. These virtues have dominated other eras of business and could

do so again as Bruce Piasecki has argued in Doing More with Less.17

These virtues include thrift, prudence in our pursuit of pleasure, effi-

ciency, waste aversion, and a focus on relationships and nonmaterial

goods. For at least three reasons, frugality virtues are important for

flourishing amid our challenges.First, it is beneficial economically.

Businesses that cultivate these virtues in their cultures willreduce

costs and find opportunities to develop financial cushions that dimin-

ish the shocks of economically turbulent times. Second, these virtues

shift employee focus from the material to the immaterial rewards of

working for an organization. The low cost, intangible pleasures of fam-

ily, friendship, meaningful work, and discovery are correlated with

happiness18 and employee engagement.19 Third, frugality virtues

focus employees on minimizing materialwaste and other negative

environmentalimpacts. Companies that have moved away from a

“take-make-waste” model of production to a more frugal model based

on closed-loop materialcycles and renewable energy have demon-

strated significant cost reductions and decreased liability risks (due to

reduction of emissions, pollution, etc.).20

Control Versus Adaptive Virtues

Control virtues, which are closely related to abundance virtues,

tend to dominate firms’ approaches to changing business condi-

tions. These habits share a tacit presupposition that we can control

enough of our environment to advance our interests. Ambition, a

can-do attitude, the will to power, dominance, and a faith in tech-

nological solutions have enabled tremendous social progress. They

remain important today; yet their underlying presuppositions are

increasingly in question. As more of our pressing challenges involve

a social component where we have limited control and as many of

the systems we are impacting are global in scale and have long

response times, we must deemphasize controland focus on adap-

tive management. Large scale culturaltransitions are usually tur-

bulent, and require organizations to have the ability to handle

traumatic change without despair and to focus on the opportuni-

ties within the changes. To flourish in this context, businesses will

230 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

must be guided by a deep awareness offinite resources and waste

sinks. These virtues have dominated other eras of business and could

do so again as Bruce Piasecki has argued in Doing More with Less.17

These virtues include thrift, prudence in our pursuit of pleasure, effi-

ciency, waste aversion, and a focus on relationships and nonmaterial

goods. For at least three reasons, frugality virtues are important for

flourishing amid our challenges.First, it is beneficial economically.

Businesses that cultivate these virtues in their cultures willreduce

costs and find opportunities to develop financial cushions that dimin-

ish the shocks of economically turbulent times. Second, these virtues

shift employee focus from the material to the immaterial rewards of

working for an organization. The low cost, intangible pleasures of fam-

ily, friendship, meaningful work, and discovery are correlated with

happiness18 and employee engagement.19 Third, frugality virtues

focus employees on minimizing materialwaste and other negative

environmentalimpacts. Companies that have moved away from a

“take-make-waste” model of production to a more frugal model based

on closed-loop materialcycles and renewable energy have demon-

strated significant cost reductions and decreased liability risks (due to

reduction of emissions, pollution, etc.).20

Control Versus Adaptive Virtues

Control virtues, which are closely related to abundance virtues,

tend to dominate firms’ approaches to changing business condi-

tions. These habits share a tacit presupposition that we can control

enough of our environment to advance our interests. Ambition, a

can-do attitude, the will to power, dominance, and a faith in tech-

nological solutions have enabled tremendous social progress. They

remain important today; yet their underlying presuppositions are

increasingly in question. As more of our pressing challenges involve

a social component where we have limited control and as many of

the systems we are impacting are global in scale and have long

response times, we must deemphasize controland focus on adap-

tive management. Large scale culturaltransitions are usually tur-

bulent, and require organizations to have the ability to handle

traumatic change without despair and to focus on the opportuni-

ties within the changes. To flourish in this context, businesses will

230 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

need to innovate more aggressively, to become much more resilient,

and to appreciate the struggle as part of any intensely meaningful

long term-project.

We will continue to control many aspects of our environment,

but we must avoid generalizing this strategy to many of the issues

that confront us. We must become more comfortable with adversity

and more accepting of what we cannot change in the external envi-

ronment, which requires us to change internally.

Adaptive virtues enable us to deal effectively with limits to our

control. These can be subdivided into those traits that help us to

individually cope with what we cannot control and those that help

others to cope. The first group includes resilience, flexibility, cour-

age, hopefulness, creativity, entrepreneurial spirit, composure,

self-control, and the second includes empathy, self-sacrifice, gener-

osity, and the like. The emphasis on adaptive virtues reflects a view

that societies move through a cycle of growth leading to increasing-

ly severe challenges which eventually result in release and reorga-

nization.21 Firms that cultivate adaptive virtues in their cultures

will benefit from their employees’increased tolerance for disruptive

change and their ability to persist in pursuit of long term goals.

They are likely to have fewer personnel issues and to find the

opportunities that come with new business models, as we willsee

in the case of Green Mountain Power’s transition to a distributed

energy model based on renewables.

Conviction Versus Humility Virtues

The conviction virtues that dominate many organizational cultures

make it harder to change course as the context changes. They reflect

the assumption that we know enough based on the past to decide

how to proceed. Currently, we gravitate toward leaders who are high-

ly assertive, who express no doubts about the strategies they favor,

and who are persuasive and pugnacious. We tend to favor intellectu-

al simplification and clarity. We reward forceful managementand

quick problem resolution (even if it is a quick fix). We reward these

habits and encourage them in our organizations. Although we know

the dangers of over-confidence,we tend to focus more on building

internal scripts about justifying confidence than on carefully assess-

ing what we do and do not know.

231THROOP AND MAYBERRY

and to appreciate the struggle as part of any intensely meaningful

long term-project.

We will continue to control many aspects of our environment,

but we must avoid generalizing this strategy to many of the issues

that confront us. We must become more comfortable with adversity

and more accepting of what we cannot change in the external envi-

ronment, which requires us to change internally.

Adaptive virtues enable us to deal effectively with limits to our

control. These can be subdivided into those traits that help us to

individually cope with what we cannot control and those that help

others to cope. The first group includes resilience, flexibility, cour-

age, hopefulness, creativity, entrepreneurial spirit, composure,

self-control, and the second includes empathy, self-sacrifice, gener-

osity, and the like. The emphasis on adaptive virtues reflects a view

that societies move through a cycle of growth leading to increasing-

ly severe challenges which eventually result in release and reorga-

nization.21 Firms that cultivate adaptive virtues in their cultures

will benefit from their employees’increased tolerance for disruptive

change and their ability to persist in pursuit of long term goals.

They are likely to have fewer personnel issues and to find the

opportunities that come with new business models, as we willsee

in the case of Green Mountain Power’s transition to a distributed

energy model based on renewables.

Conviction Versus Humility Virtues

The conviction virtues that dominate many organizational cultures

make it harder to change course as the context changes. They reflect

the assumption that we know enough based on the past to decide

how to proceed. Currently, we gravitate toward leaders who are high-

ly assertive, who express no doubts about the strategies they favor,

and who are persuasive and pugnacious. We tend to favor intellectu-

al simplification and clarity. We reward forceful managementand

quick problem resolution (even if it is a quick fix). We reward these

habits and encourage them in our organizations. Although we know

the dangers of over-confidence,we tend to focus more on building

internal scripts about justifying confidence than on carefully assess-

ing what we do and do not know.

231THROOP AND MAYBERRY

These virtues have undoubtedly contributed to personal and

organizational success, but their dominance in corporate cul-

tures now makes it harder to deal effectively with the complexity

of the systems which we must try to explain and predict. Convic-

tion virtues tend to limit the creative thinking necessary for deal-

ing with novel situations, and they tend to polarize people

around ideological issues. They also require a degree of hypocrisy

in our leaders, who must claim to know what to do in unfolding

crises, when that is often unreasonable. Over time, this results

in lack of trust in the institutions that we need to help us

address our challenges.

The contrasting humility virtues focus us on the limits in our

knowledge about how a complex system will behave, and about

how to resolve our differences respectfully. Humility virtues include

an open-mindedness about the views of others and a curiosity

about the perspectives of multiple disciplines. They promote genu-

ine questioning of one’s own and others’ views. They include the

gratitude appropriate for all that we learn from others. Humble

leaders typically celebrate the work ofothers, rely on high stand-

ards to motivate people, use transparent decision making, and act

“with quiet, calm determination.”22 This is compatible with also

acknowledging that we have some important kinds of knowledge,

but these virtues avoid the hubris of generalizing knowledge

beyond its legitimate scope. In times of major transition, our usual

forms of inductive reasoning about the future are even less reliable

than normal. Under such conditions, asking the right questions is

often more important than having an answer. Firms that cultivate

open-mindedness and curiosity are more likely to see break-

through solutions to problems. They are also likely to avoid group

think. If they emphasize humility virtues, organizations will be

more open to complexity and less likely to oversimplify.They will

be more likely to seek the wisdom of others and to collaborate.

They will be better positioned to be genuine learning

organizations.23

Competitive Versus Collaborative Virtues

The conviction virtues are reinforced by a set of competitive

virtues, which we celebrate in schools, sports, business, and

232 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

organizational success, but their dominance in corporate cul-

tures now makes it harder to deal effectively with the complexity

of the systems which we must try to explain and predict. Convic-

tion virtues tend to limit the creative thinking necessary for deal-

ing with novel situations, and they tend to polarize people

around ideological issues. They also require a degree of hypocrisy

in our leaders, who must claim to know what to do in unfolding

crises, when that is often unreasonable. Over time, this results

in lack of trust in the institutions that we need to help us

address our challenges.

The contrasting humility virtues focus us on the limits in our

knowledge about how a complex system will behave, and about

how to resolve our differences respectfully. Humility virtues include

an open-mindedness about the views of others and a curiosity

about the perspectives of multiple disciplines. They promote genu-

ine questioning of one’s own and others’ views. They include the

gratitude appropriate for all that we learn from others. Humble

leaders typically celebrate the work ofothers, rely on high stand-

ards to motivate people, use transparent decision making, and act

“with quiet, calm determination.”22 This is compatible with also

acknowledging that we have some important kinds of knowledge,

but these virtues avoid the hubris of generalizing knowledge

beyond its legitimate scope. In times of major transition, our usual

forms of inductive reasoning about the future are even less reliable

than normal. Under such conditions, asking the right questions is

often more important than having an answer. Firms that cultivate

open-mindedness and curiosity are more likely to see break-

through solutions to problems. They are also likely to avoid group

think. If they emphasize humility virtues, organizations will be

more open to complexity and less likely to oversimplify.They will

be more likely to seek the wisdom of others and to collaborate.

They will be better positioned to be genuine learning

organizations.23

Competitive Versus Collaborative Virtues

The conviction virtues are reinforced by a set of competitive

virtues, which we celebrate in schools, sports, business, and

232 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 30

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.