Leading Diversity: Towards a Theory of Functional Leadership

VerifiedAdded on 2023/05/11

|28

|33350

|184

Report

AI Summary

This report presents the Leading Diversity (LeaD) model, an integrative conceptual review of functional leadership in diverse teams. It addresses the critical need for a dynamic theory on the interplay between team diversity and leadership, reviewing existing research and identifying shortcomings. The LeaD model proposes that effective leadership requires knowledge of diversity-related processes (informational vs. intergroup), mastery of task- and person-focused leadership behaviors, and the competencies to diagnose team needs and apply appropriate leadership actions. The model integrates findings from various studies, highlighting the importance of proactive and reactive attention to team needs and the management of these processes. It emphasizes the role of leaders in shaping the influence of team diversity on team outcomes, and the importance of specific competencies that enable leaders to effectively manage diverse teams to promote optimal processes and performance. The report covers definitions of team and diversity, and its scope focuses on interdependent teams working on complex tasks.

INTEGRATIVE CONCEPTUAL REVIEW

Leading Diversity: Towards a Theory of Functional Leadership in

Diverse Teams

Astrid C. Homan and Seval Gündemir

University of Amsterdam

Claudia Buengeler

Kiel University

Gerben A. van Kleef

University of Amsterdam

The importance of leaders as diversity managers is widely acknowledged. However, a dynamic and

comprehensive theory on the interplay between team diversity and team leadership is missing. We

provide a review of the extant (scattered) research on the interplay between team diversity and team

leadership, which reveals critical shortcomings in the current scholarly understanding. This calls for an

integrative theoretical account of functional diversity leadership in teams. Here we outline such an

integrative theory. We propose that functional diversity leadership requires (a) knowledge of the

favorable and unfavorable processes that can be instigated by diversity, (b) mastery of task- and

person-focused leadership behaviors necessary to address associated team needs, and (c) competencies

to predict and/or diagnose team needs and to apply corresponding leadership behaviors to address those

needs. We integrate findings of existing studies on the interplay between leadership and team diversity

with insights from separate literatures on team diversity and (team) leadership. The resulting Leading

Diversity model (LeaD) posits that effective leadership of diverse teams requires proactive as well as

reactive attention to teams’ needs in terms of informational versus intergroup processes and adequate

management of these processes through task- versus person-focused leadership. LeaD offers new insights

into specific competencies and actions that allow leaders to shape the influence of team diversity on team

outcomes and, thereby, harvest the potential value in diversity. Organizations can capitalize on this model

to promote optimal processes and performance in diverse teams.

Keywords: team diversity, team leadership, team performance, intergroup bias, information elaboration

With the influx of diversity in today’s organizations and work

teams, leaders are increasingly at the forefront of managing the

potential advantages and disadvantages of team diversity. Team

leaders are vital for promoting, managing, supporting, and devel-

oping team functioning (Burke et al., 2006; Horne, Plessis, &

Nkomo, 2015; Yukl, 2010; Zaccaro & Klimoski, 2002; Zaccaro,

Rittman, & Marks, 2001), and diversity management is inherent to

leading teams. In the current work, we first present an extensive

review of the literature on the intersection of team diversity and

team leadership, which reveals critical lacunae in our current

understanding that call for an integrative theoretical account of

functional diversity leadership in teams. Next, we present such an

integrative theoretical model, integrating knowledge on two core

leadership functions with emergent insights on the complexities of

team diversity in shaping team processes and outcomes.

Recently, scholars have begun to investigate the interface be-

tween team leadership and team diversity, by focusing on how

leadership behaviors and skills moderate the effects of team di-

versity (e.g., Homan & Greer, 2013; Hüttermann & Boerner, 2011;

Kearney & Gebert, 2009; Somech, 2006). This research has fo-

cused on a variety of diversity dimensions, examined both lead-

ership behaviors and characteristics, and suggests that leaders can

both proactively influence as well as reactively attend to diversity-

This article was published Online First January 23, 2020.

X Astrid C. Homan and Seval Gündemir, Department of Work and

Organizational Psychology, University of Amsterdam; Claudia Buengeler,

Institute of Business, Department of Human Resource Management and

Organization, Kiel University; Gerben A. van Kleef, Department of Social

Psychology, University of Amsterdam.

Portions of this article were presented at the International Association

for Conflict Management conference (2012), the Group Processes and

Intergroup Relations Conference at Stanford University (2018), the Inter-

national Workshop on Teamworking 23 (2019), Solvay Brussels School

(2019), and the Dutch Association for Social Psychological Research

conference (2019).

We are very grateful to Drew Carton, John Hollenbeck, Stephen Hum-

phrey, and Barbara Nevicka for their useful feedback, ideas, and insights.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Astrid C.

Homan, Department of Work and Organizational Psychology,University of

Amsterdam, P.O. Box 15919, 1001NK Amsterdam, the Netherlands. E-mail:

ac.homan@uva.nl

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Journal of Applied Psychology

© 2020 American Psychological Association 2020, Vol. 105, No. 10, 1101–1128

ISSN: 0021-9010 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000482

1101

Leading Diversity: Towards a Theory of Functional Leadership in

Diverse Teams

Astrid C. Homan and Seval Gündemir

University of Amsterdam

Claudia Buengeler

Kiel University

Gerben A. van Kleef

University of Amsterdam

The importance of leaders as diversity managers is widely acknowledged. However, a dynamic and

comprehensive theory on the interplay between team diversity and team leadership is missing. We

provide a review of the extant (scattered) research on the interplay between team diversity and team

leadership, which reveals critical shortcomings in the current scholarly understanding. This calls for an

integrative theoretical account of functional diversity leadership in teams. Here we outline such an

integrative theory. We propose that functional diversity leadership requires (a) knowledge of the

favorable and unfavorable processes that can be instigated by diversity, (b) mastery of task- and

person-focused leadership behaviors necessary to address associated team needs, and (c) competencies

to predict and/or diagnose team needs and to apply corresponding leadership behaviors to address those

needs. We integrate findings of existing studies on the interplay between leadership and team diversity

with insights from separate literatures on team diversity and (team) leadership. The resulting Leading

Diversity model (LeaD) posits that effective leadership of diverse teams requires proactive as well as

reactive attention to teams’ needs in terms of informational versus intergroup processes and adequate

management of these processes through task- versus person-focused leadership. LeaD offers new insights

into specific competencies and actions that allow leaders to shape the influence of team diversity on team

outcomes and, thereby, harvest the potential value in diversity. Organizations can capitalize on this model

to promote optimal processes and performance in diverse teams.

Keywords: team diversity, team leadership, team performance, intergroup bias, information elaboration

With the influx of diversity in today’s organizations and work

teams, leaders are increasingly at the forefront of managing the

potential advantages and disadvantages of team diversity. Team

leaders are vital for promoting, managing, supporting, and devel-

oping team functioning (Burke et al., 2006; Horne, Plessis, &

Nkomo, 2015; Yukl, 2010; Zaccaro & Klimoski, 2002; Zaccaro,

Rittman, & Marks, 2001), and diversity management is inherent to

leading teams. In the current work, we first present an extensive

review of the literature on the intersection of team diversity and

team leadership, which reveals critical lacunae in our current

understanding that call for an integrative theoretical account of

functional diversity leadership in teams. Next, we present such an

integrative theoretical model, integrating knowledge on two core

leadership functions with emergent insights on the complexities of

team diversity in shaping team processes and outcomes.

Recently, scholars have begun to investigate the interface be-

tween team leadership and team diversity, by focusing on how

leadership behaviors and skills moderate the effects of team di-

versity (e.g., Homan & Greer, 2013; Hüttermann & Boerner, 2011;

Kearney & Gebert, 2009; Somech, 2006). This research has fo-

cused on a variety of diversity dimensions, examined both lead-

ership behaviors and characteristics, and suggests that leaders can

both proactively influence as well as reactively attend to diversity-

This article was published Online First January 23, 2020.

X Astrid C. Homan and Seval Gündemir, Department of Work and

Organizational Psychology, University of Amsterdam; Claudia Buengeler,

Institute of Business, Department of Human Resource Management and

Organization, Kiel University; Gerben A. van Kleef, Department of Social

Psychology, University of Amsterdam.

Portions of this article were presented at the International Association

for Conflict Management conference (2012), the Group Processes and

Intergroup Relations Conference at Stanford University (2018), the Inter-

national Workshop on Teamworking 23 (2019), Solvay Brussels School

(2019), and the Dutch Association for Social Psychological Research

conference (2019).

We are very grateful to Drew Carton, John Hollenbeck, Stephen Hum-

phrey, and Barbara Nevicka for their useful feedback, ideas, and insights.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Astrid C.

Homan, Department of Work and Organizational Psychology,University of

Amsterdam, P.O. Box 15919, 1001NK Amsterdam, the Netherlands. E-mail:

ac.homan@uva.nl

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Journal of Applied Psychology

© 2020 American Psychological Association 2020, Vol. 105, No. 10, 1101–1128

ISSN: 0021-9010 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000482

1101

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

related processes in teams. Our comprehensive review of this

literature reveals inconsistent findings pertaining to the interplay

of leadership and team diversity. For instance, research on the role

of transformational leadership behaviors—the most widely studied

leadership behavior in diverse teams— demonstrates positive, neg-

ative as well as null effects for its moderating influence on the

effects of team diversity (e.g., Kearney & Gebert, 2009; Kim,

2017; Scheuer, 2017). Based on the current empirical findings, it

remains unclear why the same leadership behaviors result in dif-

ferential outcomes of team diversity.

The idiosyncratic approaches adopted in previous empirical

work do not allow for generalized conclusions about the mecha-

nisms and contingencies that govern effective leadership of team

diversity. New empirical research is unlikely to successfully tackle

this challenge in the absence of a guiding theoretical framework.

Diversity characteristics and leadership styles can converge in

myriad ways, and scattered investigations of random combinations

are unable to provide theoretical insights necessary to derive

broadly applicable managerial implications and effective interven-

tions. As a result, academics and practitioners alike continue to

face the challenge of understanding why certain types of leader-

ship facilitate the performance of diverse teams in some cases and

frustrate performance in others (Homan & Greer, 2013; Klein,

Knight, Ziegert, Lim, & Saltz, 2011; Nishii & Mayer, 2009;

Stewart & Johnson, 2009).

Here we systematically integrate theory on the potential conse-

quences of team diversity with theory on functional team leader-

ship. This integration offers a novel lens to (re)interpret past

research findings and guides future research through a unique

theoretical synthesis of diversity and (team) leadership literatures.

Our Leading Diversity (LeaD) model provides a dynamic perspec-

tive to diversity management that goes beyond prevailing static

empirical approaches, which explicitly or implicitly assume that

particular leadership behaviors have similar effects across diverse

team contexts. LeaD accounts for variations in team-specific needs

(that are related to the dominant process instigated by diversity)

and the ability of leaders to adapt to those anticipated or existing

needs. Moreover, LeaD generates actionable insights by revealing

antecedents of functional leadership in diverse teams that can be

influenced by organizations through, for example, training and

selection. As such, LeaD can help leaders more effectively manage

diverse teams as well as aid organizations in pairing leaders with

teams to enhance performance.

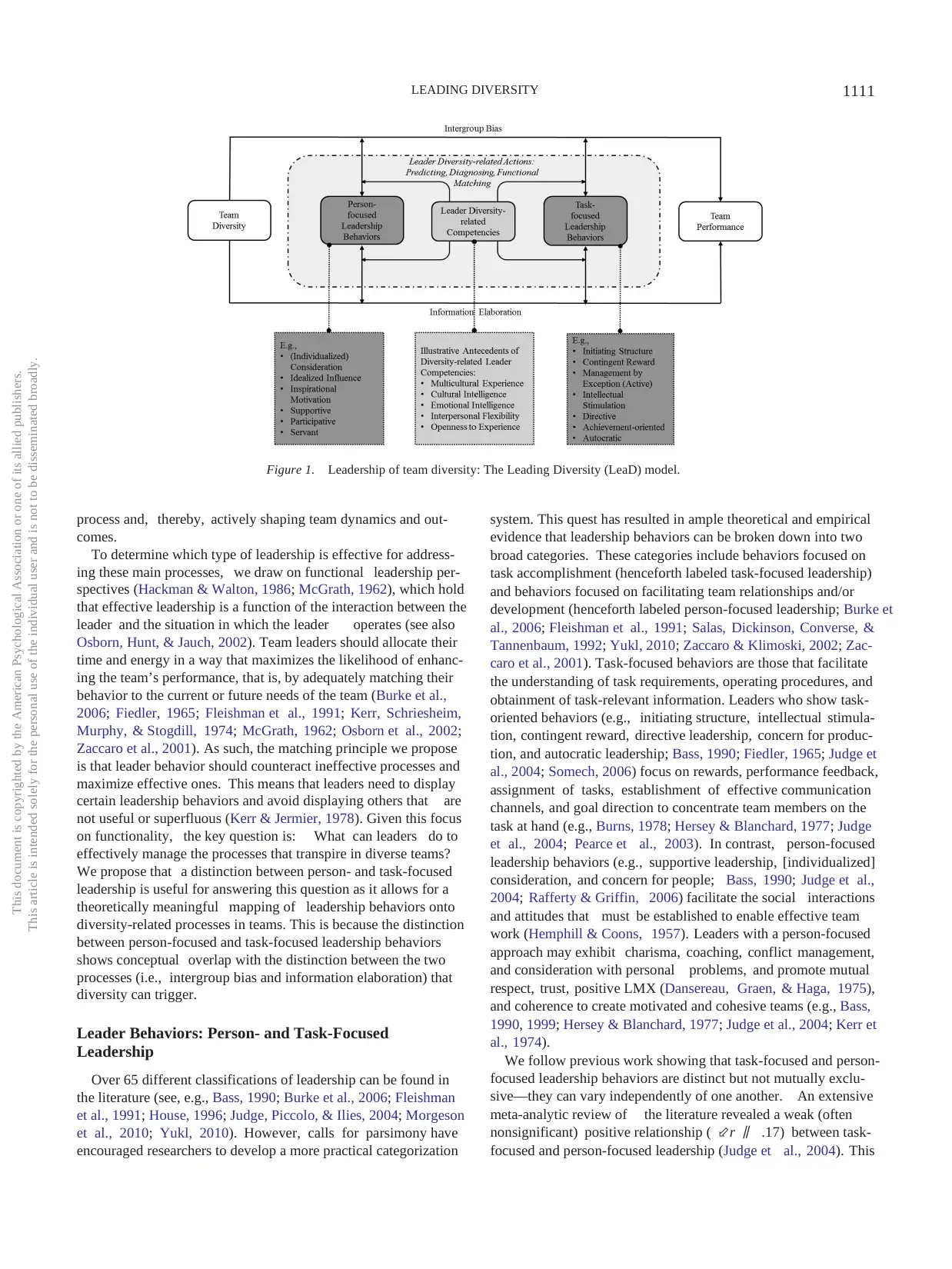

LeaD incorporates the psycho-behavioral processes that can be

instigated by diversity, the behaviors that leaders may exhibit to

address these processes proactively and reactively, and the

diversity-related competencies of leaders that facilitate these be-

haviors. First, we propose that team diversity can create highly

different situations for leaders to operate in, depending on the

predominant processes instigated by team diversity (i.e., subgroup

categorization and concomitant intergroup bias or information

elaboration). Second, to be able to address these processes, leaders

must possess diversity-related competencies (i.e., cognitive under-

standing, social perceptiveness, and behavioral flexibility), which

help them to predict and/or diagnose the team’s needs and perform

functional leadership behaviors (i.e., diversity-related actions; cf.

Hooijberg, Hunt, & Dodge, 1997). Third, leaders must be able to

exhibit functional leadership behaviors (i.e., enact person- and

task- focused leadership), and to flexibly adopt these behaviors to

address distinct diversity-related processes. In short, as we elabo-

rate below, LeaD specifies how leaders’ diversity-related compe-

tencies shape their proactive and reactive behaviors vis-a `-vis di-

verse teams, and when and how the exhibited leadership behaviors

improve or deteriorate the relationship between team diversity and

team performance.

Developing an integrative theory of the interplay between team

diversity and team leadership is important for two interrelated

reasons. First, it is widely accepted that diversity can bring about

favorable as well as unfavorable processes in teams (Milliken &

Martins, 1996; Van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004;

Williams & O’Reilly, 1998), but scholarly understanding of what

team leaders can do to promote the favorable effects and curtail the

unfavorable effects of diversity is limited. LeaD systematically

explains how diversity-related processes give rise to specific needs

at the team level for certain forms of leadership. We will argue

that, depending on the nature of those needs, leaders can proac-

tively or reactively provide complementary or supplementary

matching leadership behaviors. While we acknowledge leaders’

direct influence on team dynamics (independent of diversity; e.g.,

Burke et al., 2006; Day, Gronn, & Salas, 2006; Morgeson, DeRue,

& Karam, 2010; Zaccaro et al., 2001), the current work aims at

contributing to a better understanding of the requirements of

leaders who operate in and with diverse teams by focusing spe-

cifically on the interplay between team diversity and team leader-

ship (cf. Burke et al., 2006). Second, there is a deficiency in the

current literature with respect to understanding when and how

which types of leader behaviors are instrumental in diverse teams.

LeaD advances researchers’ and practitioners’ understanding of

when and why which types of leadership behaviors are effective in

managing diverse teams. By considering team leaders’ role at the

forefront of day-to-day diversity management, our model offers a

fine-grained understanding of the management of team diversity

through leadership.

Definitions and Scope of the Current Model

We define a team as an interdependent group of people with

relative stability and a clear collective goal (e.g., a group task;

Hackman, 2002). This definition includes (but is not limited to)

boards, management teams, R&D teams, brainstorming teams,

service teams, and project teams. Teams can be composed of

members with a variety of different demographic backgrounds,

personalities, values, knowledge, and expertise. We view diversity

as a team-level construct, that is, the distribution of differences

among the team members (Guillaume, Brodbeck, & Riketta,

2012). Diversity is defined as “differences between individuals on

any attribute that may lead to the perception that another person is

different from the self” (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004, p. 1008).

Some scholars have proposed that diversity effects depend on the

type of diversity (Harrison, Price, & Bell, 1998; Williams &

O’Reilly, 1998), with surface-level diversity (e.g., gender) being

associated with intergroup bias and reduced performance, and

deep-level diversity (e.g., personality) being linked to information

elaboration and increased performance. Nonetheless, previous re-

search has not found consistent effects of surface- or deep-level

diversity on team functioning (Bowers, Pharmer, & Salas, 2000;

Van Dijk, Van Engen, & Van Knippenberg, 2012; Webber &

Donahue, 2001). Rather, all dimensions of diversity can instigate

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1102 HOMAN, GU¨ NDEMIR, BUENGELER, AND VAN KLEEF

literature reveals inconsistent findings pertaining to the interplay

of leadership and team diversity. For instance, research on the role

of transformational leadership behaviors—the most widely studied

leadership behavior in diverse teams— demonstrates positive, neg-

ative as well as null effects for its moderating influence on the

effects of team diversity (e.g., Kearney & Gebert, 2009; Kim,

2017; Scheuer, 2017). Based on the current empirical findings, it

remains unclear why the same leadership behaviors result in dif-

ferential outcomes of team diversity.

The idiosyncratic approaches adopted in previous empirical

work do not allow for generalized conclusions about the mecha-

nisms and contingencies that govern effective leadership of team

diversity. New empirical research is unlikely to successfully tackle

this challenge in the absence of a guiding theoretical framework.

Diversity characteristics and leadership styles can converge in

myriad ways, and scattered investigations of random combinations

are unable to provide theoretical insights necessary to derive

broadly applicable managerial implications and effective interven-

tions. As a result, academics and practitioners alike continue to

face the challenge of understanding why certain types of leader-

ship facilitate the performance of diverse teams in some cases and

frustrate performance in others (Homan & Greer, 2013; Klein,

Knight, Ziegert, Lim, & Saltz, 2011; Nishii & Mayer, 2009;

Stewart & Johnson, 2009).

Here we systematically integrate theory on the potential conse-

quences of team diversity with theory on functional team leader-

ship. This integration offers a novel lens to (re)interpret past

research findings and guides future research through a unique

theoretical synthesis of diversity and (team) leadership literatures.

Our Leading Diversity (LeaD) model provides a dynamic perspec-

tive to diversity management that goes beyond prevailing static

empirical approaches, which explicitly or implicitly assume that

particular leadership behaviors have similar effects across diverse

team contexts. LeaD accounts for variations in team-specific needs

(that are related to the dominant process instigated by diversity)

and the ability of leaders to adapt to those anticipated or existing

needs. Moreover, LeaD generates actionable insights by revealing

antecedents of functional leadership in diverse teams that can be

influenced by organizations through, for example, training and

selection. As such, LeaD can help leaders more effectively manage

diverse teams as well as aid organizations in pairing leaders with

teams to enhance performance.

LeaD incorporates the psycho-behavioral processes that can be

instigated by diversity, the behaviors that leaders may exhibit to

address these processes proactively and reactively, and the

diversity-related competencies of leaders that facilitate these be-

haviors. First, we propose that team diversity can create highly

different situations for leaders to operate in, depending on the

predominant processes instigated by team diversity (i.e., subgroup

categorization and concomitant intergroup bias or information

elaboration). Second, to be able to address these processes, leaders

must possess diversity-related competencies (i.e., cognitive under-

standing, social perceptiveness, and behavioral flexibility), which

help them to predict and/or diagnose the team’s needs and perform

functional leadership behaviors (i.e., diversity-related actions; cf.

Hooijberg, Hunt, & Dodge, 1997). Third, leaders must be able to

exhibit functional leadership behaviors (i.e., enact person- and

task- focused leadership), and to flexibly adopt these behaviors to

address distinct diversity-related processes. In short, as we elabo-

rate below, LeaD specifies how leaders’ diversity-related compe-

tencies shape their proactive and reactive behaviors vis-a `-vis di-

verse teams, and when and how the exhibited leadership behaviors

improve or deteriorate the relationship between team diversity and

team performance.

Developing an integrative theory of the interplay between team

diversity and team leadership is important for two interrelated

reasons. First, it is widely accepted that diversity can bring about

favorable as well as unfavorable processes in teams (Milliken &

Martins, 1996; Van Knippenberg, De Dreu, & Homan, 2004;

Williams & O’Reilly, 1998), but scholarly understanding of what

team leaders can do to promote the favorable effects and curtail the

unfavorable effects of diversity is limited. LeaD systematically

explains how diversity-related processes give rise to specific needs

at the team level for certain forms of leadership. We will argue

that, depending on the nature of those needs, leaders can proac-

tively or reactively provide complementary or supplementary

matching leadership behaviors. While we acknowledge leaders’

direct influence on team dynamics (independent of diversity; e.g.,

Burke et al., 2006; Day, Gronn, & Salas, 2006; Morgeson, DeRue,

& Karam, 2010; Zaccaro et al., 2001), the current work aims at

contributing to a better understanding of the requirements of

leaders who operate in and with diverse teams by focusing spe-

cifically on the interplay between team diversity and team leader-

ship (cf. Burke et al., 2006). Second, there is a deficiency in the

current literature with respect to understanding when and how

which types of leader behaviors are instrumental in diverse teams.

LeaD advances researchers’ and practitioners’ understanding of

when and why which types of leadership behaviors are effective in

managing diverse teams. By considering team leaders’ role at the

forefront of day-to-day diversity management, our model offers a

fine-grained understanding of the management of team diversity

through leadership.

Definitions and Scope of the Current Model

We define a team as an interdependent group of people with

relative stability and a clear collective goal (e.g., a group task;

Hackman, 2002). This definition includes (but is not limited to)

boards, management teams, R&D teams, brainstorming teams,

service teams, and project teams. Teams can be composed of

members with a variety of different demographic backgrounds,

personalities, values, knowledge, and expertise. We view diversity

as a team-level construct, that is, the distribution of differences

among the team members (Guillaume, Brodbeck, & Riketta,

2012). Diversity is defined as “differences between individuals on

any attribute that may lead to the perception that another person is

different from the self” (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004, p. 1008).

Some scholars have proposed that diversity effects depend on the

type of diversity (Harrison, Price, & Bell, 1998; Williams &

O’Reilly, 1998), with surface-level diversity (e.g., gender) being

associated with intergroup bias and reduced performance, and

deep-level diversity (e.g., personality) being linked to information

elaboration and increased performance. Nonetheless, previous re-

search has not found consistent effects of surface- or deep-level

diversity on team functioning (Bowers, Pharmer, & Salas, 2000;

Van Dijk, Van Engen, & Van Knippenberg, 2012; Webber &

Donahue, 2001). Rather, all dimensions of diversity can instigate

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1102 HOMAN, GU¨ NDEMIR, BUENGELER, AND VAN KLEEF

positive as well as negative effects depending on moderating

influences (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004), provided that team

members are aware of the respective differences (Shemla, Meyer,

Greer, & Jehn, 2016). Our model is, therefore, applicable to the

wide range of possible diversity characteristics.

We focus our theory development primarily on smaller (rather

than larger) teams, in which leaders can more easily observe and

address group processes. In line with Zaccaro and colleagues

(2001), we presume that a team has a clear hierarchical structure,

in which the leader is held responsible and accountable for its

functioning. We assume that the leader is motivated to understand

the team’s needs and manage team diversity (see also Nishii,

Khattab, Shemla, & Paluch, 2018). Additionally, as diversity has

greater potential to benefit performance on complex and interde-

pendent rather than simple and independent tasks (Bowers et al.,

2000; Chatman, Greer, Sherman, & Doerr, 2019; Jehn, Northcraft,

& Neale, 1999; Van der Vegt & Janssen, 2003; Wegge, Roth,

Neubach, Schmidt, & Kanfer, 2008), our analysis focuses on

interdependent teams working on more complex tasks (e.g.,

problem-solving, creativity, decision-making). Finally, we exam-

ine leader effectiveness at the team level. This means that effective

team leadership should be reflected in the team’s performance,

including its productivity, decision-making quality, innovation,

creativity, viability, and member satisfaction (Yukl, 2010).

Setting the Stage for LeaD

Diversity Effects: Two Overarching Processes

According to the Categorization-Elaboration Model (CEM; Van

Knippenberg et al., 2004), the effects of diversity on team perfor-

mance can be understood by considering the favorable and unfa-

vorable processes that diversity may instigate (Joshi & Roh, 2009;

Van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). The

negative effects of diversity arise from subgroup categorization

and intergroup bias. When diversity triggers subgroup categoriza-

tion, teams are divided into subgroups— creating ingroups (i.e.,

subgroups one is part of) and outgroups (i.e., subgroups one is not

part of)— based on the (perceived) differences between the team

members (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). These subgroups, in turn, are

prone to experience intergroup bias. People tend to favor members

of their ingroup over outgroup members, which may result in

negative intrateam interactions, conflict, distrust, disliking, and

limited communication between members of different subgroups

(Brewer, 1979; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987).

Thus, subgroup categorization and concomitant intergroup bias

can impair team performance (Pelled, Eisenhardt, & Xin, 1999;

Van Knippenberg et al., 2004).

The positive effects of diversity can be explained by the avail-

ability of a richer pool of information. Given their heterogeneous

makeup, diverse teams often have more different perspectives,

information, and ideas available than do homogeneous teams

(Cox, Lobel, & McLeod, 1991). As a result, diverse teams can

potentially outperform homogeneous ones to the extent that they

engage in information elaboration (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004).

Team information elaboration refers to “the degree to which in-

formation, ideas, or cognitive processes are shared, and are being

shared, among the group members” (Hinsz, Tindale, & Vollrath,

1997, p. 43; see also De Dreu, Nijstad, & Van Knippenberg, 2008)

and involves “feeding back the results of [. . .] individual-level

processing into the group, and discussion and integration of their

implications” (Homan, Van Knippenberg, Van Kleef, & De Dreu,

2007a, p. 1189). Information elaboration is related to positive

outcomes of diverse teams, such as increased creativity and en-

hanced decision-making quality (Homan et al., 2007a; Kearney &

Gebert, 2009; Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009).

In summary, two distinct processes—intergroup bias and infor-

mation elaboration—resulting from differences between team

members can explain the differential effects of diversity on team

performance. These processes are not mutually exclusive, but they

tend to be negatively related, and at any given point in time one

process will typically be more dominant and predict performance

better than the other (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004). If diverse

teams experience intergroup bias, information elaboration is less

likely to occur. Conversely, if information elaboration is promi-

nent, intergroup bias is likely to be less pronounced.

Informed by CEM (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004), research in

the last decade has examined a variety of moderators that can

explain why diversity in some cases instigates intergroup bias and

in other cases stimulates information elaboration (for an overview,

see Guillaume, Dawson, Otaye-Ebede, Woods, & West, 2017).

One stream of research has shown that diverse teams are less likely

to experience intergroup bias when social categories are less

salient (Homan et al., 2007a, 2008; Nishii, 2013; Van Knippenberg

et al., 2004). Another stream of research has shown that teams are

more likely to engage in thorough information elaboration when

team members are more open to different information (Homan et

al., 2008; Kearney, Gebert, & Voelpel, 2009; Schippers, Den

Hartog, Koopman, & Wienk, 2003). Within this focus on moder-

ators of team diversity effects, the interest in the role of leaders in

addressing diversity has been steadily increasing (e.g., Guillaume

et al., 2014, 2017; Nishii et al., 2018; Roberts, 2006).

Review of Research on the Interplay Between

Diversity and Leadership

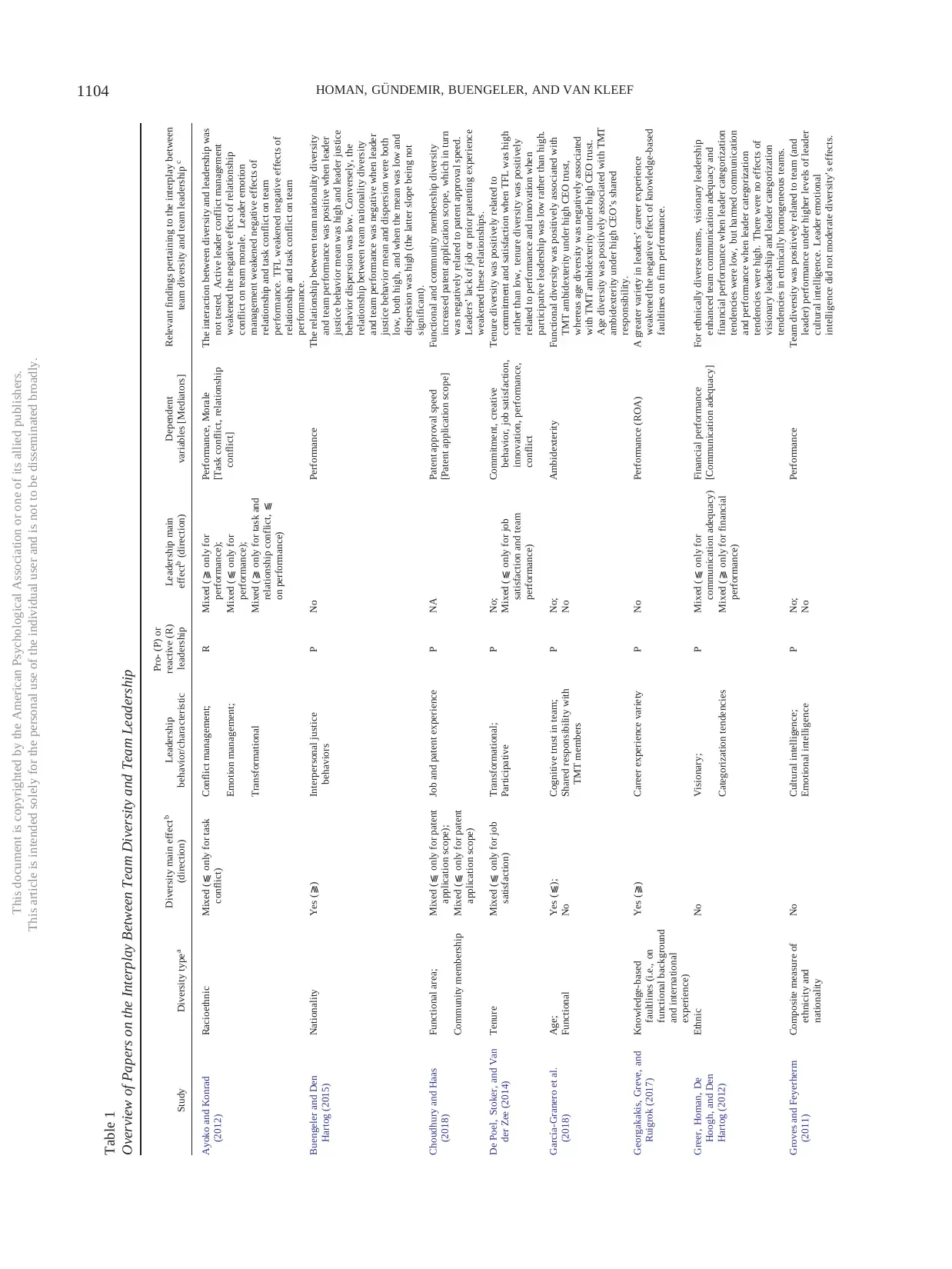

We conducted an extensive review of the literature on the

interplay between team diversity and leadership. We performed a

literature search using Web of Science, Ovid, and Google Scholar

(using the key words “team” or “group” AND “diversity” AND

“leadership”) and identified 44 empirical papers out of approxi-

mately 500 hits that examined the interplay between team diversity

and team leadership on a variety of team processes and outcomes.

A detailed description of the 44 reviewed articles and findings can

be found in Table 1.

Our review reveals that authors have adopted idiosyncratic

approaches in studying the intersection between diversity and

leadership, focusing on a myriad diversity dimensions and over 30

different leadership behaviors and leader characteristics. In terms

of diversity, scholars have investigated, among other things, ef-

fects of diversity in demographic characteristics (e.g., nationality,

ethnicity, gender, and age), personality (e.g., traits, values), and

informational background (e.g., education, professional experi-

ence). These dimensions were crossed with an even larger number

of leadership behaviors and characteristics (see below). The het-

erogeneity of the available set of studies notwithstanding, our

review allows for four broad conclusions about the current state of

the art.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1103LEADING DIVERSITY

influences (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004), provided that team

members are aware of the respective differences (Shemla, Meyer,

Greer, & Jehn, 2016). Our model is, therefore, applicable to the

wide range of possible diversity characteristics.

We focus our theory development primarily on smaller (rather

than larger) teams, in which leaders can more easily observe and

address group processes. In line with Zaccaro and colleagues

(2001), we presume that a team has a clear hierarchical structure,

in which the leader is held responsible and accountable for its

functioning. We assume that the leader is motivated to understand

the team’s needs and manage team diversity (see also Nishii,

Khattab, Shemla, & Paluch, 2018). Additionally, as diversity has

greater potential to benefit performance on complex and interde-

pendent rather than simple and independent tasks (Bowers et al.,

2000; Chatman, Greer, Sherman, & Doerr, 2019; Jehn, Northcraft,

& Neale, 1999; Van der Vegt & Janssen, 2003; Wegge, Roth,

Neubach, Schmidt, & Kanfer, 2008), our analysis focuses on

interdependent teams working on more complex tasks (e.g.,

problem-solving, creativity, decision-making). Finally, we exam-

ine leader effectiveness at the team level. This means that effective

team leadership should be reflected in the team’s performance,

including its productivity, decision-making quality, innovation,

creativity, viability, and member satisfaction (Yukl, 2010).

Setting the Stage for LeaD

Diversity Effects: Two Overarching Processes

According to the Categorization-Elaboration Model (CEM; Van

Knippenberg et al., 2004), the effects of diversity on team perfor-

mance can be understood by considering the favorable and unfa-

vorable processes that diversity may instigate (Joshi & Roh, 2009;

Van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). The

negative effects of diversity arise from subgroup categorization

and intergroup bias. When diversity triggers subgroup categoriza-

tion, teams are divided into subgroups— creating ingroups (i.e.,

subgroups one is part of) and outgroups (i.e., subgroups one is not

part of)— based on the (perceived) differences between the team

members (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). These subgroups, in turn, are

prone to experience intergroup bias. People tend to favor members

of their ingroup over outgroup members, which may result in

negative intrateam interactions, conflict, distrust, disliking, and

limited communication between members of different subgroups

(Brewer, 1979; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987).

Thus, subgroup categorization and concomitant intergroup bias

can impair team performance (Pelled, Eisenhardt, & Xin, 1999;

Van Knippenberg et al., 2004).

The positive effects of diversity can be explained by the avail-

ability of a richer pool of information. Given their heterogeneous

makeup, diverse teams often have more different perspectives,

information, and ideas available than do homogeneous teams

(Cox, Lobel, & McLeod, 1991). As a result, diverse teams can

potentially outperform homogeneous ones to the extent that they

engage in information elaboration (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004).

Team information elaboration refers to “the degree to which in-

formation, ideas, or cognitive processes are shared, and are being

shared, among the group members” (Hinsz, Tindale, & Vollrath,

1997, p. 43; see also De Dreu, Nijstad, & Van Knippenberg, 2008)

and involves “feeding back the results of [. . .] individual-level

processing into the group, and discussion and integration of their

implications” (Homan, Van Knippenberg, Van Kleef, & De Dreu,

2007a, p. 1189). Information elaboration is related to positive

outcomes of diverse teams, such as increased creativity and en-

hanced decision-making quality (Homan et al., 2007a; Kearney &

Gebert, 2009; Mesmer-Magnus & DeChurch, 2009).

In summary, two distinct processes—intergroup bias and infor-

mation elaboration—resulting from differences between team

members can explain the differential effects of diversity on team

performance. These processes are not mutually exclusive, but they

tend to be negatively related, and at any given point in time one

process will typically be more dominant and predict performance

better than the other (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004). If diverse

teams experience intergroup bias, information elaboration is less

likely to occur. Conversely, if information elaboration is promi-

nent, intergroup bias is likely to be less pronounced.

Informed by CEM (Van Knippenberg et al., 2004), research in

the last decade has examined a variety of moderators that can

explain why diversity in some cases instigates intergroup bias and

in other cases stimulates information elaboration (for an overview,

see Guillaume, Dawson, Otaye-Ebede, Woods, & West, 2017).

One stream of research has shown that diverse teams are less likely

to experience intergroup bias when social categories are less

salient (Homan et al., 2007a, 2008; Nishii, 2013; Van Knippenberg

et al., 2004). Another stream of research has shown that teams are

more likely to engage in thorough information elaboration when

team members are more open to different information (Homan et

al., 2008; Kearney, Gebert, & Voelpel, 2009; Schippers, Den

Hartog, Koopman, & Wienk, 2003). Within this focus on moder-

ators of team diversity effects, the interest in the role of leaders in

addressing diversity has been steadily increasing (e.g., Guillaume

et al., 2014, 2017; Nishii et al., 2018; Roberts, 2006).

Review of Research on the Interplay Between

Diversity and Leadership

We conducted an extensive review of the literature on the

interplay between team diversity and leadership. We performed a

literature search using Web of Science, Ovid, and Google Scholar

(using the key words “team” or “group” AND “diversity” AND

“leadership”) and identified 44 empirical papers out of approxi-

mately 500 hits that examined the interplay between team diversity

and team leadership on a variety of team processes and outcomes.

A detailed description of the 44 reviewed articles and findings can

be found in Table 1.

Our review reveals that authors have adopted idiosyncratic

approaches in studying the intersection between diversity and

leadership, focusing on a myriad diversity dimensions and over 30

different leadership behaviors and leader characteristics. In terms

of diversity, scholars have investigated, among other things, ef-

fects of diversity in demographic characteristics (e.g., nationality,

ethnicity, gender, and age), personality (e.g., traits, values), and

informational background (e.g., education, professional experi-

ence). These dimensions were crossed with an even larger number

of leadership behaviors and characteristics (see below). The het-

erogeneity of the available set of studies notwithstanding, our

review allows for four broad conclusions about the current state of

the art.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1103LEADING DIVERSITY

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

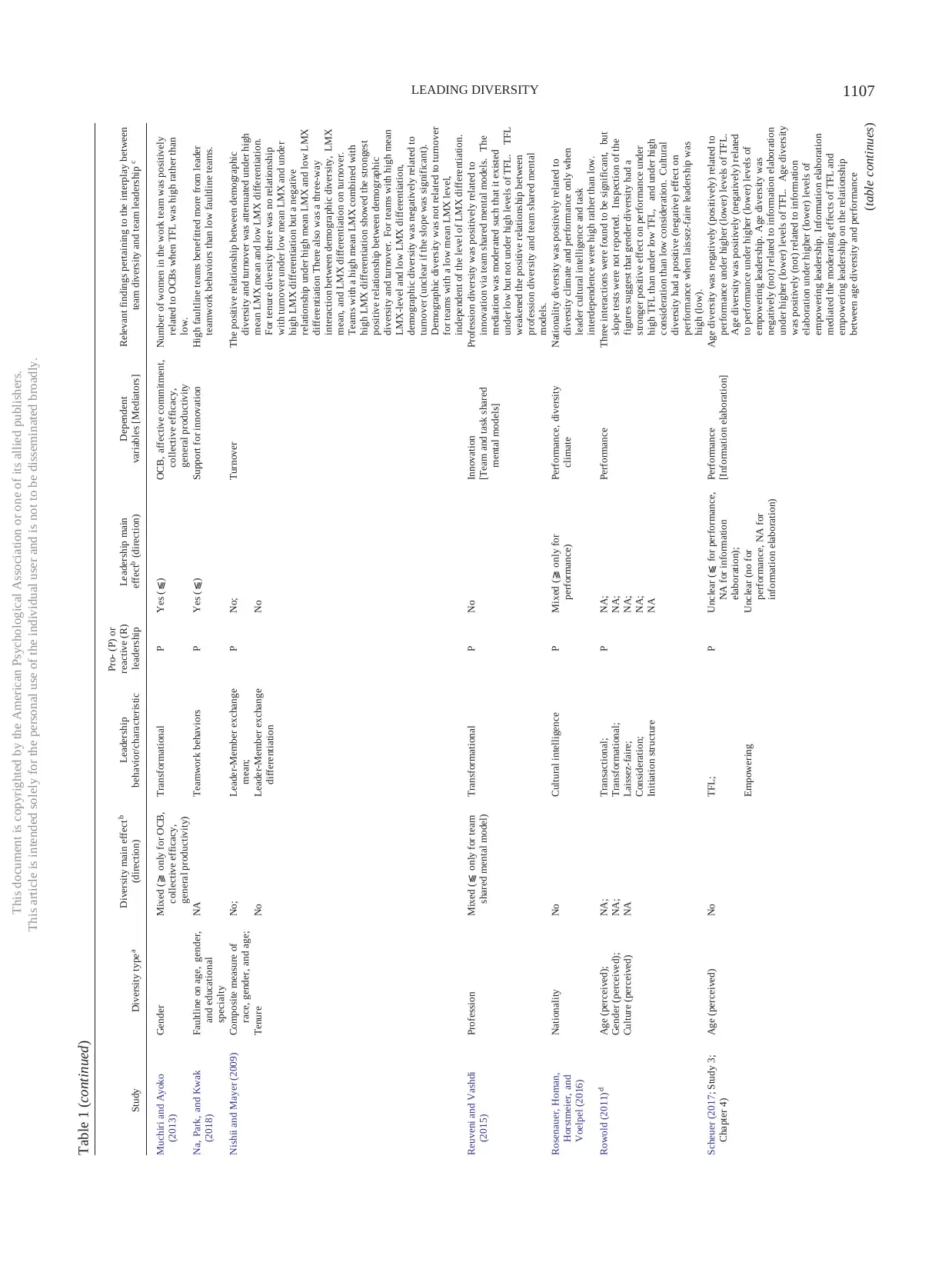

Table 1

Overview of Papers on the Interplay Between Team Diversity and Team Leadership

Study Diversity type a

Diversity main effect b

(direction)

Leadership

behavior/characteristic

Pro- (P) or

reactive (R)

leadership

Leadership main

effectb (direction)

Dependent

variables [Mediators]

Relevant findings pertaining to the interplay between

team diversity and team leadership c

Ayoko and Konrad

(2012)

Racioethnic Mixed (⫹ only for task

conflict)

Conflict management; R Mixed (⫺ only for

performance);

Performance, Morale

[Task conflict, relationship

conflict]

The interaction between diversity and leadership was

not tested. Active leader conflict management

weakened the negative effect of relationship

conflict on team morale. Leader emotion

management weakened negative effects of

relationship and task conflict on team

performance. TFL weakened negative effects of

relationship and task conflict on team

performance.

Emotion management; Mixed (⫹ only for

performance);

Transformational Mixed (⫺ only for task and

relationship conflict, ⫹

on performance)

Buengeler and Den

Hartog (2015)

Nationality Yes (⫺) Interpersonal justice

behaviors

P No Performance The relationship between team nationality diversity

and team performance was positive when leader

justice behavior mean was high and leader justice

behavior dispersion was low. Conversely, the

relationship between team nationality diversity

and team performance was negative when leader

justice behavior mean and dispersion were both

low, both high, and when the mean was low and

dispersion was high (the latter slope being not

significant).

Choudhury and Haas

(2018)

Functional area; Mixed (⫹ only for patent

application scope);

Job and patent experience P NA Patent approval speed

[Patent application scope]

Functional and community membership diversity

increased patent application scope, which in turn

was negatively related to patent approval speed.

Leaders’ lack of job or prior patenting experience

weakened these relationships.

Community membership Mixed (⫹ only for patent

application scope)

De Poel, Stoker, and Van

der Zee (2014)

Tenure Mixed (⫹ only for job

satisfaction)

Transformational;

Participative

P No;

Mixed (⫹ only for job

satisfaction and team

performance)

Commitment, creative

behavior, job satisfaction,

innovation, performance,

conflict

Tenure diversity was positively related to

commitment and satisfaction when TFL was high

rather than low, tenure diversity was positively

related to performance and innovation when

participative leadership was low rather than high.

García-Granero et al.

(2018)

Age;

Functional

Yes (⫹);

No

Cognitive trust in team;

Shared responsibility with

TMT members

P No;

No

Ambidexterity Functional diversity was positively associated with

TMT ambidexterity under high CEO trust,

whereas age diversity was negatively associated

with TMT ambidexterity under high CEO trust.

Age diversity was positively associated with TMT

ambidexterity under high CEO’s shared

responsibility.

Georgakakis, Greve, and

Ruigrok (2017)

Knowledge-based

faultlines (i.e., on

functional background

and international

experience)

Yes (⫺) Career experience variety P No Performance (ROA) A greater variety in leaders’ career experience

weakened the negative effect of knowledge-based

faultlines on firm performance.

Greer, Homan, De

Hoogh, and Den

Hartog (2012)

Ethnic No Visionary; P Mixed (⫹ only for

communication adequacy)

Financial performance

[Communication adequacy]

For ethnically diverse teams, visionary leadership

enhanced team communication adequacy and

financial performance when leader categorization

tendencies were low, but harmed communication

and performance when leader categorization

tendencies were high. There were no effects of

visionary leadership and leader categorization

tendencies in ethnically homogeneous teams.

Categorization tendencies Mixed (⫺ only for financial

performance)

Groves and Feyerherm

(2011)

Composite measure of

ethnicity and

nationality

No Cultural intelligence;

Emotional intelligence

P No;

No

Performance Team diversity was positively related to team (and

leader) performance under higher levels of leader

cultural intelligence. Leader emotional

intelligence did not moderate diversity’s effects.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1104 HOMAN, GU¨ NDEMIR, BUENGELER, AND VAN KLEEF

Overview of Papers on the Interplay Between Team Diversity and Team Leadership

Study Diversity type a

Diversity main effect b

(direction)

Leadership

behavior/characteristic

Pro- (P) or

reactive (R)

leadership

Leadership main

effectb (direction)

Dependent

variables [Mediators]

Relevant findings pertaining to the interplay between

team diversity and team leadership c

Ayoko and Konrad

(2012)

Racioethnic Mixed (⫹ only for task

conflict)

Conflict management; R Mixed (⫺ only for

performance);

Performance, Morale

[Task conflict, relationship

conflict]

The interaction between diversity and leadership was

not tested. Active leader conflict management

weakened the negative effect of relationship

conflict on team morale. Leader emotion

management weakened negative effects of

relationship and task conflict on team

performance. TFL weakened negative effects of

relationship and task conflict on team

performance.

Emotion management; Mixed (⫹ only for

performance);

Transformational Mixed (⫺ only for task and

relationship conflict, ⫹

on performance)

Buengeler and Den

Hartog (2015)

Nationality Yes (⫺) Interpersonal justice

behaviors

P No Performance The relationship between team nationality diversity

and team performance was positive when leader

justice behavior mean was high and leader justice

behavior dispersion was low. Conversely, the

relationship between team nationality diversity

and team performance was negative when leader

justice behavior mean and dispersion were both

low, both high, and when the mean was low and

dispersion was high (the latter slope being not

significant).

Choudhury and Haas

(2018)

Functional area; Mixed (⫹ only for patent

application scope);

Job and patent experience P NA Patent approval speed

[Patent application scope]

Functional and community membership diversity

increased patent application scope, which in turn

was negatively related to patent approval speed.

Leaders’ lack of job or prior patenting experience

weakened these relationships.

Community membership Mixed (⫹ only for patent

application scope)

De Poel, Stoker, and Van

der Zee (2014)

Tenure Mixed (⫹ only for job

satisfaction)

Transformational;

Participative

P No;

Mixed (⫹ only for job

satisfaction and team

performance)

Commitment, creative

behavior, job satisfaction,

innovation, performance,

conflict

Tenure diversity was positively related to

commitment and satisfaction when TFL was high

rather than low, tenure diversity was positively

related to performance and innovation when

participative leadership was low rather than high.

García-Granero et al.

(2018)

Age;

Functional

Yes (⫹);

No

Cognitive trust in team;

Shared responsibility with

TMT members

P No;

No

Ambidexterity Functional diversity was positively associated with

TMT ambidexterity under high CEO trust,

whereas age diversity was negatively associated

with TMT ambidexterity under high CEO trust.

Age diversity was positively associated with TMT

ambidexterity under high CEO’s shared

responsibility.

Georgakakis, Greve, and

Ruigrok (2017)

Knowledge-based

faultlines (i.e., on

functional background

and international

experience)

Yes (⫺) Career experience variety P No Performance (ROA) A greater variety in leaders’ career experience

weakened the negative effect of knowledge-based

faultlines on firm performance.

Greer, Homan, De

Hoogh, and Den

Hartog (2012)

Ethnic No Visionary; P Mixed (⫹ only for

communication adequacy)

Financial performance

[Communication adequacy]

For ethnically diverse teams, visionary leadership

enhanced team communication adequacy and

financial performance when leader categorization

tendencies were low, but harmed communication

and performance when leader categorization

tendencies were high. There were no effects of

visionary leadership and leader categorization

tendencies in ethnically homogeneous teams.

Categorization tendencies Mixed (⫺ only for financial

performance)

Groves and Feyerherm

(2011)

Composite measure of

ethnicity and

nationality

No Cultural intelligence;

Emotional intelligence

P No;

No

Performance Team diversity was positively related to team (and

leader) performance under higher levels of leader

cultural intelligence. Leader emotional

intelligence did not moderate diversity’s effects.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1104 HOMAN, GU¨ NDEMIR, BUENGELER, AND VAN KLEEF

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

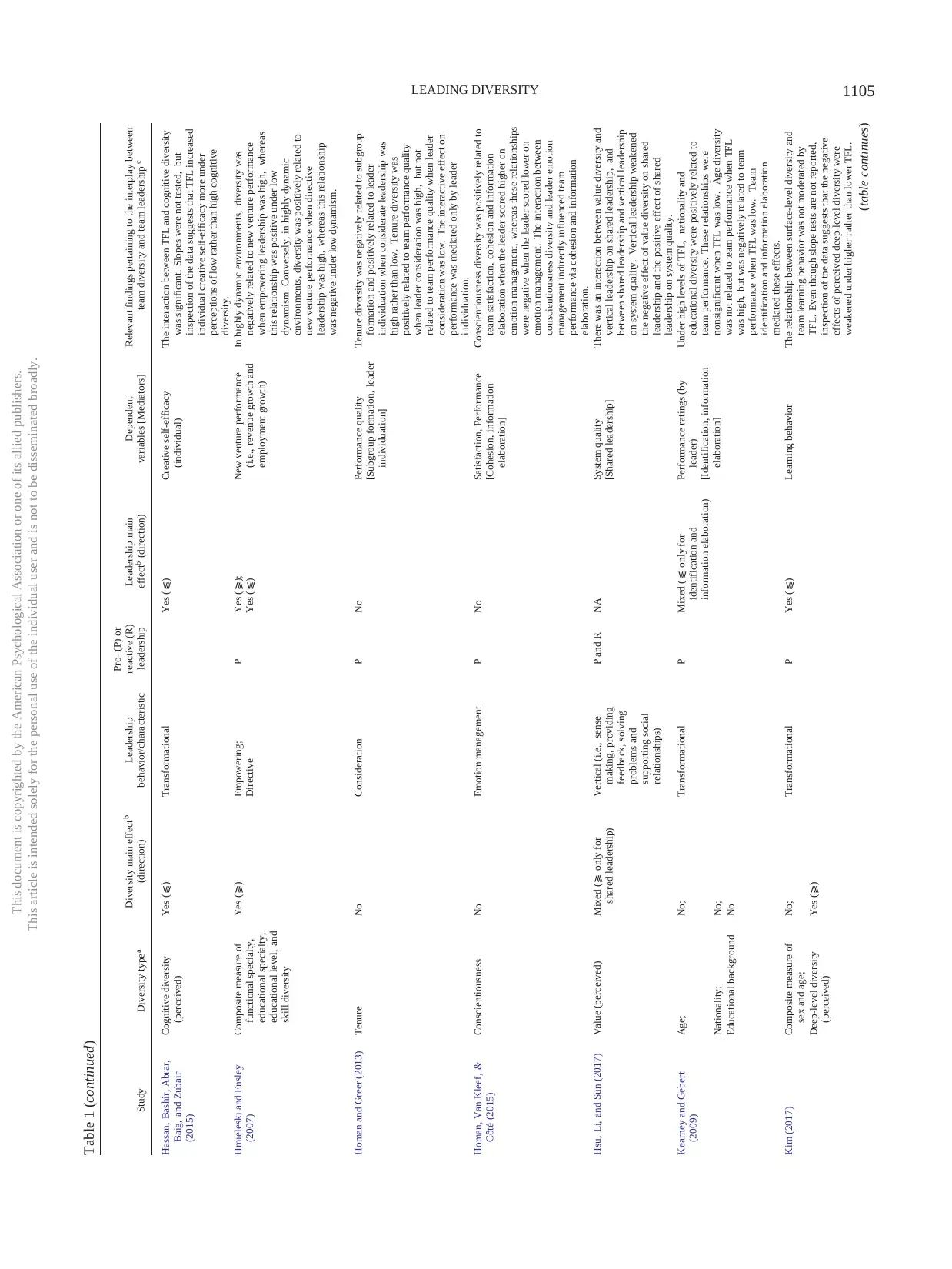

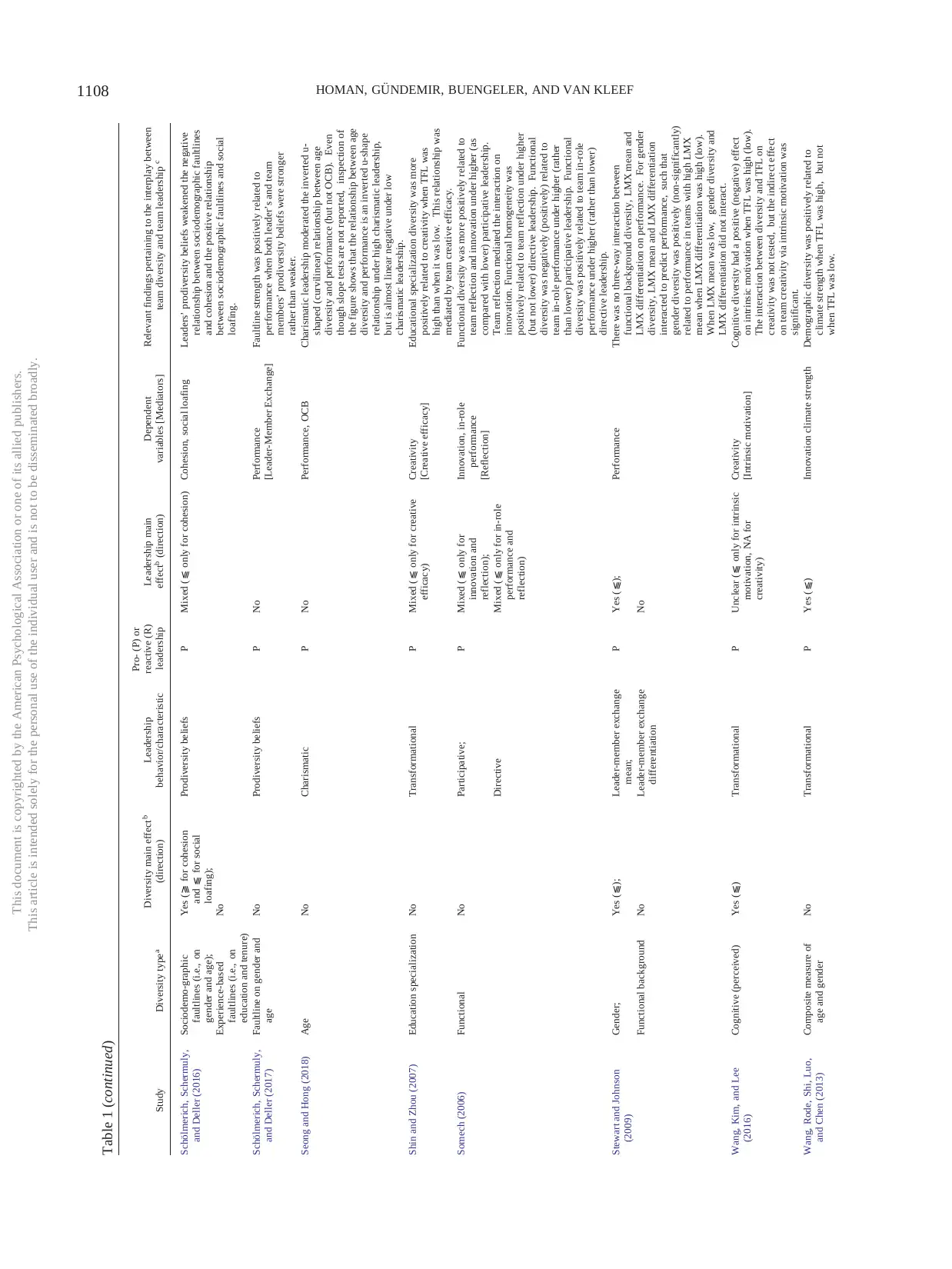

Table 1 (continued)

Study Diversity type a

Diversity main effect b

(direction)

Leadership

behavior/characteristic

Pro- (P) or

reactive (R)

leadership

Leadership main

effectb (direction)

Dependent

variables [Mediators]

Relevant findings pertaining to the interplay between

team diversity and team leadership c

Hassan, Bashir, Abrar,

Baig, and Zubair

(2015)

Cognitive diversity

(perceived)

Yes (⫹) Transformational Yes (⫹) Creative self-efficacy

(individual)

The interaction between TFL and cognitive diversity

was significant. Slopes were not tested, but

inspection of the data suggests that TFL increased

individual creative self-efficacy more under

perceptions of low rather than high cognitive

diversity.

Hmieleski and Ensley

(2007)

Composite measure of

functional specialty,

educational specialty,

educational level, and

skill diversity

Yes (⫺) Empowering;

Directive

P Yes (⫺);

Yes (⫹)

New venture performance

(i.e., revenue growth and

employment growth)

In highly dynamic environments, diversity was

negatively related to new venture performance

when empowering leadership was high, whereas

this relationship was positive under low

dynamism. Conversely, in highly dynamic

environments, diversity was positively related to

new venture performance when directive

leadership was high, whereas this relationship

was negative under low dynamism.

Homan and Greer (2013) Tenure No Consideration P No Performance quality

[Subgroup formation, leader

individuation]

Tenure diversity was negatively related to subgroup

formation and positively related to leader

individuation when considerate leadership was

high rather than low. Tenure diversity was

positively related to team performance quality

when leader consideration was high, but not

related to team performance quality when leader

consideration was low. The interactive effect on

performance was mediated only by leader

individuation.

Homan, Van Kleef, &

Côté (2015)

Conscientiousness No Emotion management P No Satisfaction, Performance

[Cohesion, information

elaboration]

Conscientiousness diversity was positively related to

team satisfaction, cohesion and information

elaboration when the leader scored higher on

emotion management, whereas these relationships

were negative when the leader scored lower on

emotion management. The interaction between

conscientiousness diversity and leader emotion

management indirectly influenced team

performance via cohesion and information

elaboration.

Hsu, Li, and Sun (2017) Value (perceived) Mixed (⫺ only for

shared leadership)

Vertical (i.e., sense

making, providing

feedback, solving

problems and

supporting social

relationships)

P and R NA System quality

[Shared leadership]

There was an interaction between value diversity and

vertical leadership on shared leadership, and

between shared leadership and vertical leadership

on system quality. Vertical leadership weakened

the negative effect of value diversity on shared

leadership and the positive effect of shared

leadership on system quality.

Kearney and Gebert

(2009)

Age; No; Transformational P Mixed (⫹ only for

identification and

information elaboration)

Performance ratings (by

leader)

[Identification, information

elaboration]

Under high levels of TFL, nationality and

educational diversity were positively related to

team performance. These relationships were

nonsignificant when TFL was low. Age diversity

was not related to team performance when TFL

was high, but was negatively related to team

performance when TFL was low. Team

identification and information elaboration

mediated these effects.

Nationality; No;

Educational background No

Kim (2017) Composite measure of

sex and age;

No; Transformational P Yes (⫹) Learning behavior The relationship between surface-level diversity and

team learning behavior was not moderated by

TFL. Even though slope tests are not reported,

inspection of the data suggests that the negative

effects of perceived deep-level diversity were

weakened under higher rather than lower TFL.

Deep-level diversity

(perceived)

Yes (⫺)

(table continues)

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1105LEADING DIVERSITY

Study Diversity type a

Diversity main effect b

(direction)

Leadership

behavior/characteristic

Pro- (P) or

reactive (R)

leadership

Leadership main

effectb (direction)

Dependent

variables [Mediators]

Relevant findings pertaining to the interplay between

team diversity and team leadership c

Hassan, Bashir, Abrar,

Baig, and Zubair

(2015)

Cognitive diversity

(perceived)

Yes (⫹) Transformational Yes (⫹) Creative self-efficacy

(individual)

The interaction between TFL and cognitive diversity

was significant. Slopes were not tested, but

inspection of the data suggests that TFL increased

individual creative self-efficacy more under

perceptions of low rather than high cognitive

diversity.

Hmieleski and Ensley

(2007)

Composite measure of

functional specialty,

educational specialty,

educational level, and

skill diversity

Yes (⫺) Empowering;

Directive

P Yes (⫺);

Yes (⫹)

New venture performance

(i.e., revenue growth and

employment growth)

In highly dynamic environments, diversity was

negatively related to new venture performance

when empowering leadership was high, whereas

this relationship was positive under low

dynamism. Conversely, in highly dynamic

environments, diversity was positively related to

new venture performance when directive

leadership was high, whereas this relationship

was negative under low dynamism.

Homan and Greer (2013) Tenure No Consideration P No Performance quality

[Subgroup formation, leader

individuation]

Tenure diversity was negatively related to subgroup

formation and positively related to leader

individuation when considerate leadership was

high rather than low. Tenure diversity was

positively related to team performance quality

when leader consideration was high, but not

related to team performance quality when leader

consideration was low. The interactive effect on

performance was mediated only by leader

individuation.

Homan, Van Kleef, &

Côté (2015)

Conscientiousness No Emotion management P No Satisfaction, Performance

[Cohesion, information

elaboration]

Conscientiousness diversity was positively related to

team satisfaction, cohesion and information

elaboration when the leader scored higher on

emotion management, whereas these relationships

were negative when the leader scored lower on

emotion management. The interaction between

conscientiousness diversity and leader emotion

management indirectly influenced team

performance via cohesion and information

elaboration.

Hsu, Li, and Sun (2017) Value (perceived) Mixed (⫺ only for

shared leadership)

Vertical (i.e., sense

making, providing

feedback, solving

problems and

supporting social

relationships)

P and R NA System quality

[Shared leadership]

There was an interaction between value diversity and

vertical leadership on shared leadership, and

between shared leadership and vertical leadership

on system quality. Vertical leadership weakened

the negative effect of value diversity on shared

leadership and the positive effect of shared

leadership on system quality.

Kearney and Gebert

(2009)

Age; No; Transformational P Mixed (⫹ only for

identification and

information elaboration)

Performance ratings (by

leader)

[Identification, information

elaboration]

Under high levels of TFL, nationality and

educational diversity were positively related to

team performance. These relationships were

nonsignificant when TFL was low. Age diversity

was not related to team performance when TFL

was high, but was negatively related to team

performance when TFL was low. Team

identification and information elaboration

mediated these effects.

Nationality; No;

Educational background No

Kim (2017) Composite measure of

sex and age;

No; Transformational P Yes (⫹) Learning behavior The relationship between surface-level diversity and

team learning behavior was not moderated by

TFL. Even though slope tests are not reported,

inspection of the data suggests that the negative

effects of perceived deep-level diversity were

weakened under higher rather than lower TFL.

Deep-level diversity

(perceived)

Yes (⫺)

(table continues)

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1105LEADING DIVERSITY

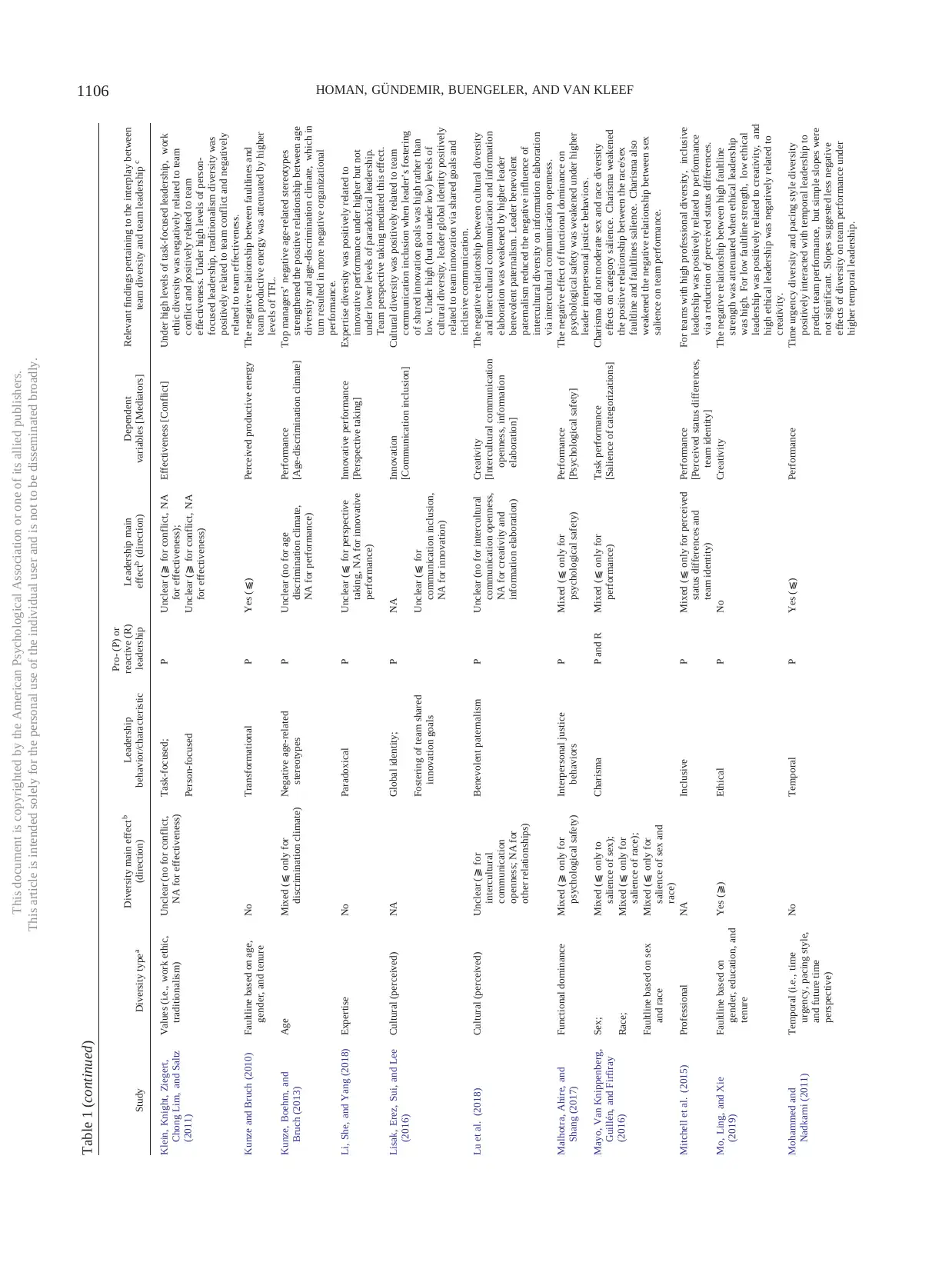

Table 1 (continued)

Study Diversity type a

Diversity main effect b

(direction)

Leadership

behavior/characteristic

Pro- (P) or

reactive (R)

leadership

Leadership main

effectb (direction)

Dependent

variables [Mediators]

Relevant findings pertaining to the interplay between

team diversity and team leadership c

Klein, Knight, Ziegert,

Chong Lim, and Saltz

(2011)

Values (i.e., work ethic,

traditionalism)

Unclear (no for conflict,

NA for effectiveness)

Task-focused; P Unclear (⫺ for conflict, NA

for effectiveness);

Effectiveness [Conflict] Under high levels of task-focused leadership, work

ethic diversity was negatively related to team

conflict and positively related to team

effectiveness. Under high levels of person-

focused leadership, traditionalism diversity was

positively related to team conflict and negatively

related to team effectiveness.

Person-focused Unclear (⫺ for conflict, NA

for effectiveness)

Kunze and Bruch (2010) Faultline based on age,

gender, and tenure

No Transformational P Yes (⫹) Perceived productive energy The negative relationship between faultlines and

team productive energy was attenuated by higher

levels of TFL.

Kunze, Boehm, and

Bruch (2013)

Age Mixed (⫹ only for

discrimination climate)

Negative age-related

stereotypes

P Unclear (no for age

discrimination climate,

NA for performance)

Performance

[Age-discrimination climate]

Top managers’ negative age-related stereotypes

strengthened the positive relationship between age

diversity and age-discrimination climate, which in

turn resulted in more negative organizational

performance.

Li, She, and Yang (2018) Expertise No Paradoxical P Unclear (⫹ for perspective

taking, NA for innovative

performance)

Innovative performance

[Perspective taking]

Expertise diversity was positively related to

innovative performance under higher but not

under lower levels of paradoxical leadership.

Team perspective taking mediated this effect.

Lisak, Erez, Sui, and Lee

(2016)

Cultural (perceived) NA Global identity; P NA Innovation

[Communication inclusion]

Cultural diversity was positively related to team

communication inclusion when leader’s fostering

of shared innovation goals was high rather than

low. Under high (but not under low) levels of

cultural diversity, leader global identity positively

related to team innovation via shared goals and

inclusive communication.

Fostering of team shared

innovation goals

Unclear (⫹ for

communication inclusion,

NA for innovation)

Lu et al. (2018) Cultural (perceived) Unclear (⫺ for

intercultural

communication

openness; NA for

other relationships)

Benevolent paternalism P Unclear (no for intercultural

communication openness,

NA for creativity and

information elaboration)

Creativity

[Intercultural communication

openness, information

elaboration]

The negative relationship between cultural diversity

and intercultural communication and information

elaboration was weakened by higher leader

benevolent paternalism. Leader benevolent

paternalism reduced the negative influence of

intercultural diversity on information elaboration

via intercultural communication openness.

Malhotra, Ahire, and

Shang (2017)

Functional dominance Mixed (⫺ only for

psychological safety)

Interpersonal justice

behaviors

P Mixed (⫹ only for

psychological safety)

Performance

[Psychological safety]

The negative effect of functional dominance on

psychological safety was weakened under higher

leader interpersonal justice behaviors.

Mayo, Van Knippenberg,

Guillén, and Firfiray

(2016)

Sex; Mixed (⫹ only to

salience of sex);

Charisma P and R Mixed (⫹ only for

performance)

Task performance

[Salience of categorizations]

Charisma did not moderate sex and race diversity

effects on category salience. Charisma weakened

the positive relationship between the race/sex

faultline and faultlines salience. Charisma also

weakened the negative relationship between sex

salience on team performance.

Race; Mixed (⫹ only for

salience of race);

Faultline based on sex

and race

Mixed (⫹ only for

salience of sex and

race)

Mitchell et al. (2015) Professional NA Inclusive P Mixed (⫹ only for perceived

status differences and

team identity)

Performance

[Perceived status differences,

team identity]

For teams with high professional diversity, inclusive

leadership was positively related to performance

via a reduction of perceived status differences.

Mo, Ling, and Xie

(2019)

Faultline based on

gender, education, and

tenure

Yes (⫺) Ethical P No Creativity The negative relationship between high faultline

strength was attenuated when ethical leadership

was high. For low faultline strength, low ethical

leadership was positively related to creativity, and

high ethical leadership was negatively related to

creativity.

Mohammed and

Nadkarni (2011)

Temporal (i.e., time

urgency, pacing style,

and future time

perspective)

No Temporal P Yes (⫹) Performance Time urgency diversity and pacing style diversity

positively interacted with temporal leadership to

predict team performance, but simple slopes were

not significant. Slopes suggested less negative

effects of diversity on team performance under

higher temporal leadership.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1106 HOMAN, GU¨ NDEMIR, BUENGELER, AND VAN KLEEF

Study Diversity type a

Diversity main effect b

(direction)

Leadership

behavior/characteristic

Pro- (P) or

reactive (R)

leadership

Leadership main

effectb (direction)

Dependent

variables [Mediators]

Relevant findings pertaining to the interplay between

team diversity and team leadership c

Klein, Knight, Ziegert,

Chong Lim, and Saltz

(2011)

Values (i.e., work ethic,

traditionalism)

Unclear (no for conflict,

NA for effectiveness)

Task-focused; P Unclear (⫺ for conflict, NA

for effectiveness);

Effectiveness [Conflict] Under high levels of task-focused leadership, work

ethic diversity was negatively related to team

conflict and positively related to team

effectiveness. Under high levels of person-

focused leadership, traditionalism diversity was

positively related to team conflict and negatively

related to team effectiveness.

Person-focused Unclear (⫺ for conflict, NA

for effectiveness)

Kunze and Bruch (2010) Faultline based on age,

gender, and tenure

No Transformational P Yes (⫹) Perceived productive energy The negative relationship between faultlines and

team productive energy was attenuated by higher

levels of TFL.

Kunze, Boehm, and

Bruch (2013)

Age Mixed (⫹ only for

discrimination climate)

Negative age-related

stereotypes

P Unclear (no for age

discrimination climate,

NA for performance)

Performance

[Age-discrimination climate]

Top managers’ negative age-related stereotypes

strengthened the positive relationship between age

diversity and age-discrimination climate, which in

turn resulted in more negative organizational

performance.

Li, She, and Yang (2018) Expertise No Paradoxical P Unclear (⫹ for perspective

taking, NA for innovative

performance)

Innovative performance

[Perspective taking]

Expertise diversity was positively related to

innovative performance under higher but not

under lower levels of paradoxical leadership.

Team perspective taking mediated this effect.

Lisak, Erez, Sui, and Lee

(2016)

Cultural (perceived) NA Global identity; P NA Innovation

[Communication inclusion]

Cultural diversity was positively related to team

communication inclusion when leader’s fostering

of shared innovation goals was high rather than

low. Under high (but not under low) levels of

cultural diversity, leader global identity positively

related to team innovation via shared goals and

inclusive communication.

Fostering of team shared

innovation goals

Unclear (⫹ for

communication inclusion,

NA for innovation)

Lu et al. (2018) Cultural (perceived) Unclear (⫺ for

intercultural

communication

openness; NA for

other relationships)

Benevolent paternalism P Unclear (no for intercultural

communication openness,

NA for creativity and

information elaboration)

Creativity

[Intercultural communication

openness, information

elaboration]

The negative relationship between cultural diversity

and intercultural communication and information

elaboration was weakened by higher leader

benevolent paternalism. Leader benevolent

paternalism reduced the negative influence of

intercultural diversity on information elaboration

via intercultural communication openness.

Malhotra, Ahire, and

Shang (2017)

Functional dominance Mixed (⫺ only for

psychological safety)

Interpersonal justice

behaviors

P Mixed (⫹ only for

psychological safety)

Performance

[Psychological safety]

The negative effect of functional dominance on

psychological safety was weakened under higher

leader interpersonal justice behaviors.

Mayo, Van Knippenberg,

Guillén, and Firfiray

(2016)

Sex; Mixed (⫹ only to

salience of sex);

Charisma P and R Mixed (⫹ only for

performance)

Task performance

[Salience of categorizations]

Charisma did not moderate sex and race diversity

effects on category salience. Charisma weakened

the positive relationship between the race/sex

faultline and faultlines salience. Charisma also

weakened the negative relationship between sex

salience on team performance.

Race; Mixed (⫹ only for

salience of race);

Faultline based on sex

and race

Mixed (⫹ only for

salience of sex and

race)

Mitchell et al. (2015) Professional NA Inclusive P Mixed (⫹ only for perceived

status differences and

team identity)

Performance

[Perceived status differences,

team identity]

For teams with high professional diversity, inclusive

leadership was positively related to performance

via a reduction of perceived status differences.

Mo, Ling, and Xie

(2019)

Faultline based on

gender, education, and

tenure

Yes (⫺) Ethical P No Creativity The negative relationship between high faultline

strength was attenuated when ethical leadership

was high. For low faultline strength, low ethical

leadership was positively related to creativity, and

high ethical leadership was negatively related to

creativity.

Mohammed and

Nadkarni (2011)

Temporal (i.e., time

urgency, pacing style,

and future time

perspective)

No Temporal P Yes (⫹) Performance Time urgency diversity and pacing style diversity

positively interacted with temporal leadership to

predict team performance, but simple slopes were

not significant. Slopes suggested less negative

effects of diversity on team performance under

higher temporal leadership.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

1106 HOMAN, GU¨ NDEMIR, BUENGELER, AND VAN KLEEF

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

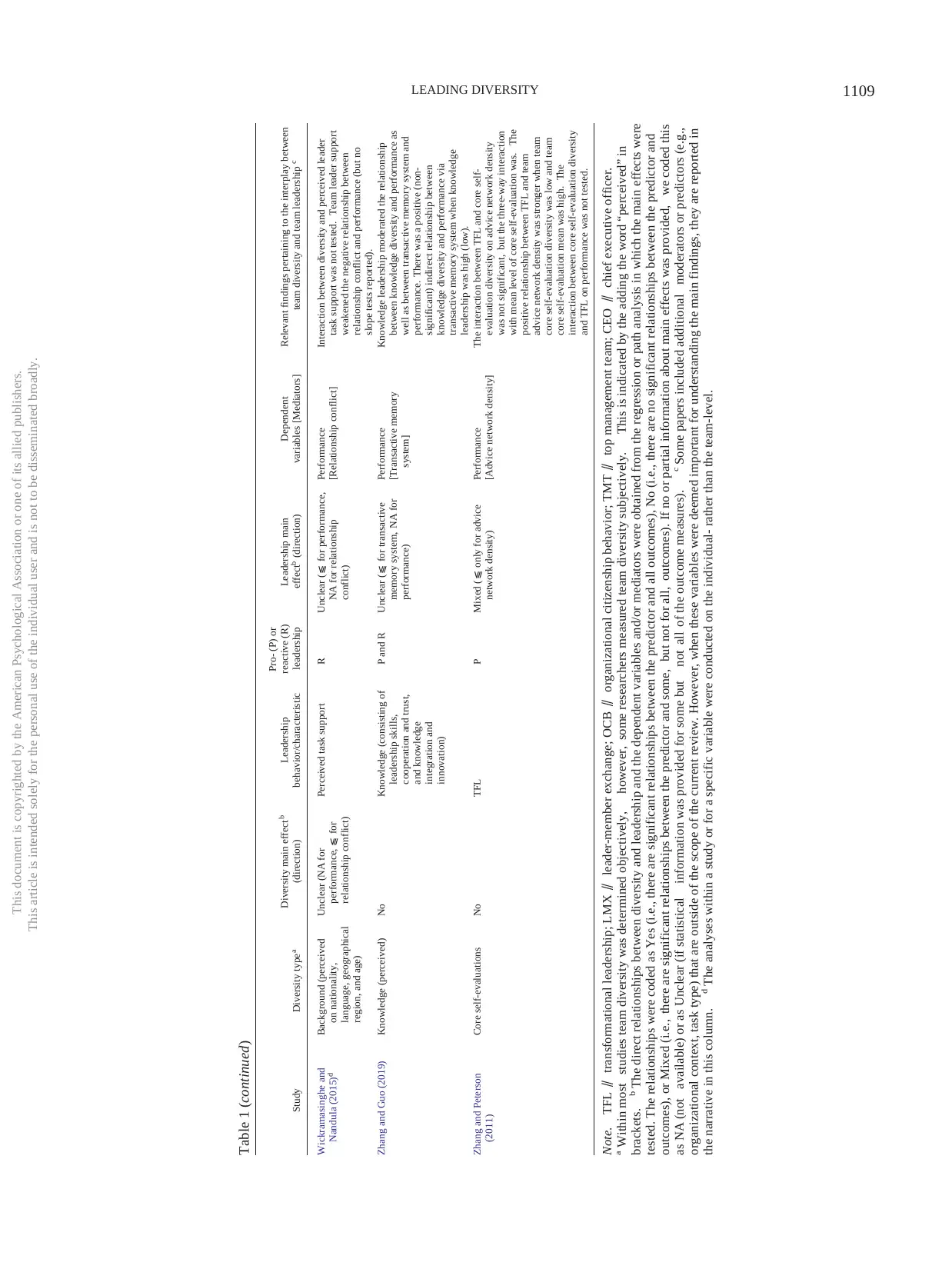

Table 1 (continued)

Study Diversity type a

Diversity main effect b

(direction)

Leadership

behavior/characteristic

Pro- (P) or

reactive (R)

leadership

Leadership main

effectb (direction)

Dependent

variables [Mediators]

Relevant findings pertaining to the interplay between

team diversity and team leadership c

Muchiri and Ayoko

(2013)

Gender Mixed (⫺ only for OCB,

collective efficacy,

general productivity)

Transformational P Yes (⫹) OCB, affective commitment,

collective efficacy,

general productivity

Number of women in the work team was positively

related to OCBs when TFL was high rather than

low.

Na, Park, and Kwak

(2018)

Faultline on age, gender,

and educational

specialty

NA Teamwork behaviors P Yes (⫹) Support for innovation High faultline teams benefitted more from leader

teamwork behaviors than low faultline teams.