Comprehensive Life Cycle Analysis of Lithium-ion Battery Production

VerifiedAdded on 2021/04/21

|15

|4204

|498

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive life cycle analysis (LCA) of lithium-ion batteries, examining their environmental impact from production to recycling. The study delves into the various stages of battery manufacturing, including the extraction of raw materials like lithium carbonate and the production of cathode and anode components. It highlights the energy-intensive nature of processes such as graphitization and cathode material synthesis, and the use of fossil fuels. The report also explores the battery assembly process, from paste coating to cell charging and testing, emphasizing the energy consumption and potential waste generation at each stage. Furthermore, the analysis underscores the importance of recycling processes to mitigate environmental burdens and improve energy efficiency, particularly given the scarcity of materials used in Li-ion batteries. The report aims to provide insights into the environmental challenges and trade-offs associated with Li-ion battery technology, considering the increasing demand for electric vehicles and the need for sustainable practices.

1

Life Cycle Analysis for Lithium-ion Battery Production and Processing

1.0 Introduction

The debate on the impact of automotive emissions on environment has been

escalating over the past decades. The Olofsson (1) estimates that transportation sector emits

16% of CO2, which needs drastic reduction. Different legislative stipulations have been

passed to facilitate the reduction of the emissions: for example, Euro-6 and Euro-VI emission

stipulations for light and heavy vehicles respectively were introduced in 2014 to regulate the

emission of NOx among the new models (1). With increasing fear on debilitation of fossil fuel

and pressing issues of energy security, there is a growing interest on the need to improve

energy efficiency. Based on the recent developments from auto industry and the government,

Gaines et al (2) observe that batteries are considered to be the most suitable in manufacturing

as well as marketing electric-drive cars; both “plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs)” and

battery electric vehicles (p.3).

According to Gaines et al (2), effective installation of “viable battery systems for

electric-driven vehicles” has the efficacy to minimize fossil fuels consumption as well as

reducing greenhouse emissions (GHG) (p.3). Nevertheless, so much is yet to be established

insofar as electric-drive performance and impacts of batteries on their efficiencies is

concerned. Batteries that contain high specific energy and peculiar life cycle remain the

fundamental elements that will facilitate successful manufacture of electric-drive vehicles,

however. More importantly, scientists consider lithium-ion batteries (Li-ion) to be the main

factor that will enhance the penetration of the technology. Nelson et al (3) attest that the

nature of electric-drive market is multi-faceted— in terms of engineering execution,

consumer preference, and affordability (2).

Life Cycle Analysis for Lithium-ion Battery Production and Processing

1.0 Introduction

The debate on the impact of automotive emissions on environment has been

escalating over the past decades. The Olofsson (1) estimates that transportation sector emits

16% of CO2, which needs drastic reduction. Different legislative stipulations have been

passed to facilitate the reduction of the emissions: for example, Euro-6 and Euro-VI emission

stipulations for light and heavy vehicles respectively were introduced in 2014 to regulate the

emission of NOx among the new models (1). With increasing fear on debilitation of fossil fuel

and pressing issues of energy security, there is a growing interest on the need to improve

energy efficiency. Based on the recent developments from auto industry and the government,

Gaines et al (2) observe that batteries are considered to be the most suitable in manufacturing

as well as marketing electric-drive cars; both “plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs)” and

battery electric vehicles (p.3).

According to Gaines et al (2), effective installation of “viable battery systems for

electric-driven vehicles” has the efficacy to minimize fossil fuels consumption as well as

reducing greenhouse emissions (GHG) (p.3). Nevertheless, so much is yet to be established

insofar as electric-drive performance and impacts of batteries on their efficiencies is

concerned. Batteries that contain high specific energy and peculiar life cycle remain the

fundamental elements that will facilitate successful manufacture of electric-drive vehicles,

however. More importantly, scientists consider lithium-ion batteries (Li-ion) to be the main

factor that will enhance the penetration of the technology. Nelson et al (3) attest that the

nature of electric-drive market is multi-faceted— in terms of engineering execution,

consumer preference, and affordability (2).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

2

Essentially, the impact of such vehicles on the environmental performance is among

the key driving factors towards their developments. On the crux of the matter is emission and

energy efficiency of battery cells. However, there are some existential trade-offs that are

inevitable when deployment of electric-drive vehicle will be effected. The energy trade-off

necessitates quantification in developing conventional cars by lightweight materials, which

reflects the balance between extra energy incurred in developing lightweight material and the

fuel saved in driving it, due to the reduced weight (3).

Like any other product system, the burdens of life-cycle batteries emanates from

different life-cycle phases, for example, during production of the material, during production

and the usage of the battery, or during battery recycling phase. Adequate information on

challenges incurred when developing lithium component materials like iron phosphate,

lithium cobalt dioxide, lithium hexafuolorophosphate, and lithium nickel dioxide —

including some process information— is still lacking. Due to this absence, estimation of the

production energy as well as emissions with regard to the life cycle has been made difficult.

This paper provides an overview on the impacts of lithium-ion life cycle batteries. The paper

focuses on the burden of battery recycling to the production of active materials, which have

not been properly characterized hitherto.

1.1 Goal

The objective of this paper is to examine the life cycle impacts of Lithium-ion

batteries. Special interest is placed on the burden of the production process and recycling

process of Li-ion battery cells. Due to the scarcity of materials used in the manufacturing of

Li-ion, the paper dissects recycling processes that have the efficacy to underscore energy

efficiency and reduce emissions.

Essentially, the impact of such vehicles on the environmental performance is among

the key driving factors towards their developments. On the crux of the matter is emission and

energy efficiency of battery cells. However, there are some existential trade-offs that are

inevitable when deployment of electric-drive vehicle will be effected. The energy trade-off

necessitates quantification in developing conventional cars by lightweight materials, which

reflects the balance between extra energy incurred in developing lightweight material and the

fuel saved in driving it, due to the reduced weight (3).

Like any other product system, the burdens of life-cycle batteries emanates from

different life-cycle phases, for example, during production of the material, during production

and the usage of the battery, or during battery recycling phase. Adequate information on

challenges incurred when developing lithium component materials like iron phosphate,

lithium cobalt dioxide, lithium hexafuolorophosphate, and lithium nickel dioxide —

including some process information— is still lacking. Due to this absence, estimation of the

production energy as well as emissions with regard to the life cycle has been made difficult.

This paper provides an overview on the impacts of lithium-ion life cycle batteries. The paper

focuses on the burden of battery recycling to the production of active materials, which have

not been properly characterized hitherto.

1.1 Goal

The objective of this paper is to examine the life cycle impacts of Lithium-ion

batteries. Special interest is placed on the burden of the production process and recycling

process of Li-ion battery cells. Due to the scarcity of materials used in the manufacturing of

Li-ion, the paper dissects recycling processes that have the efficacy to underscore energy

efficiency and reduce emissions.

3

1.2 Life Cycle Assessment

Generally, LCA method is used to dissect the environmental consequences of an

entire life cycle that involves production of a given product or service (1). The most common

areas, according to Olofsson (1) where the knowledge of LCA is applied include “product

development, production processes, and waste management” (p.2). The method has become

increasingly significant for environmental communication. On product development, LCA is

facilitates assessment of potential hotspots of a product life cycle and improves development

of eco-design, which provides a springboard to identify “the most optimal design” at the

conceptual phase (1). In order to realize the optimal design it is imperative to avoid hazardous

materials, cut down the energy used in production stage, use light materials and high quality

features to encourage weight minimization, and use materials that can be upgraded, repaired,

recycled, and reused.

2.0 Functional Unit

2.1 Rechargeable battery

The use of batteries to develop small-scale electric sources and portable devices has

been on upward trajectory. Depending on their capacities, batteries can be used to power a

variety of electronic devices and automotive. Young (4) observes that the capability of

rechargeable battery to store chemical energy and produce electric energy, as well their

durability feature has made it more prevalent in today’s society. Olofsson (1) asserts that

when battery cell is connected to an external circuit, “oxidation and reduction reactions occur

at the negative and positive electrodes respectively” (p.4). Consequently, the electrons flow

towards and the external circuit while the ions flow within electrodes via electrolyte. An

electric insulator separates the anode and the cathode, and facilitates the flow of electrons to

the external circuit only. The insulator also slows down the reaction process when the cell is

1.2 Life Cycle Assessment

Generally, LCA method is used to dissect the environmental consequences of an

entire life cycle that involves production of a given product or service (1). The most common

areas, according to Olofsson (1) where the knowledge of LCA is applied include “product

development, production processes, and waste management” (p.2). The method has become

increasingly significant for environmental communication. On product development, LCA is

facilitates assessment of potential hotspots of a product life cycle and improves development

of eco-design, which provides a springboard to identify “the most optimal design” at the

conceptual phase (1). In order to realize the optimal design it is imperative to avoid hazardous

materials, cut down the energy used in production stage, use light materials and high quality

features to encourage weight minimization, and use materials that can be upgraded, repaired,

recycled, and reused.

2.0 Functional Unit

2.1 Rechargeable battery

The use of batteries to develop small-scale electric sources and portable devices has

been on upward trajectory. Depending on their capacities, batteries can be used to power a

variety of electronic devices and automotive. Young (4) observes that the capability of

rechargeable battery to store chemical energy and produce electric energy, as well their

durability feature has made it more prevalent in today’s society. Olofsson (1) asserts that

when battery cell is connected to an external circuit, “oxidation and reduction reactions occur

at the negative and positive electrodes respectively” (p.4). Consequently, the electrons flow

towards and the external circuit while the ions flow within electrodes via electrolyte. An

electric insulator separates the anode and the cathode, and facilitates the flow of electrons to

the external circuit only. The insulator also slows down the reaction process when the cell is

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

4

connected to an external source. The pendulum of the amount of energy that the battery has

swings from state of charge (SOC) to discharge, depending on how the battery is used (4).

2.2 Materials available in Lithium-ion batteries/ components

Li et al (5) state that LCA is the most appropriate method when it comes to comparing

alternative technological systems, since it entails broad assessment of life cycle of a product

or a service, including production of materials, service provision, and maintenance. The paper

focuses on quantitative elements of LCA. The paper relies on Gaines et al analysis of

GREETZ 2.7 model to examine impact of Lithium-ion batteries. Dunn et al (6) hold that Li-

ion batteries have been considered efficient in contemporary as well as future battery

technology because they quintessentially have high volumes of energy and gravimetric

power. The interplay flow of lithium ions between anode and cathode forms the central basis

of Li-ion batteries mechanism. The electrodes are made up of conducting foil. Between the

electrodes lies electrolyte. The active component of electrode is made of intercalation

materials that have the efficacy to host Li-ions without dismantling their structures. Most

chemistries prefer using graphite to make cathode material (4).

2.2.1 Production of active materials

2.2.1.1 Lithium Carbonate

Generally, Lithium is extracted from spodumene or brine-lake deposits (2). Due to

energy consumption and economic purposes, brine-lake resources are considered to be more

efficient and have the capacity to meet the surging demand of for Li-ion automotive batteries.

During the extraction process, extensive pumping of brine from brine well “into a solar

evaporation pond” occurs and the brine is left to concentrate (2). Once sufficient evaporation

and concentration has occurred, pumping of brines to successive ponds follows until

crystallization and precipitation of sodium chloride and other salts takes place (4). After

connected to an external source. The pendulum of the amount of energy that the battery has

swings from state of charge (SOC) to discharge, depending on how the battery is used (4).

2.2 Materials available in Lithium-ion batteries/ components

Li et al (5) state that LCA is the most appropriate method when it comes to comparing

alternative technological systems, since it entails broad assessment of life cycle of a product

or a service, including production of materials, service provision, and maintenance. The paper

focuses on quantitative elements of LCA. The paper relies on Gaines et al analysis of

GREETZ 2.7 model to examine impact of Lithium-ion batteries. Dunn et al (6) hold that Li-

ion batteries have been considered efficient in contemporary as well as future battery

technology because they quintessentially have high volumes of energy and gravimetric

power. The interplay flow of lithium ions between anode and cathode forms the central basis

of Li-ion batteries mechanism. The electrodes are made up of conducting foil. Between the

electrodes lies electrolyte. The active component of electrode is made of intercalation

materials that have the efficacy to host Li-ions without dismantling their structures. Most

chemistries prefer using graphite to make cathode material (4).

2.2.1 Production of active materials

2.2.1.1 Lithium Carbonate

Generally, Lithium is extracted from spodumene or brine-lake deposits (2). Due to

energy consumption and economic purposes, brine-lake resources are considered to be more

efficient and have the capacity to meet the surging demand of for Li-ion automotive batteries.

During the extraction process, extensive pumping of brine from brine well “into a solar

evaporation pond” occurs and the brine is left to concentrate (2). Once sufficient evaporation

and concentration has occurred, pumping of brines to successive ponds follows until

crystallization and precipitation of sodium chloride and other salts takes place (4). After

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

5

pumping the brine into 4-5 ponds, addition of slake lime— to precipitate calcium and

magnesium salts— follow. This results to the production of magnesia and gypsum. When

more slake-lime is added to the successive ponds, depletion of calcium, magnesium, and

sodium salts occurs until brine with capacity of 0.5% lithium can be redirected to a

manufacturing plant that extracts lithium from lithium carbonate.

2.1.1.2 Spodumene

Another source of lithium is spodumene. Based on Gaines et al analysis (2),

spodumene is a mineral that consist of “lithium aluminium inosilicate— LiAl(SiO3)” (p.6).

Due to efficiency concerns, its production from minerals has drastically reduced. Eventually,

new cost-effective technique, which involves “production from salars,” has been discovered

(1). Nevertheless, producers still consider extraction from mineral deposits, in pursuit of

achieving supply diversification and reducing reliability of the external suppliers (4). Besides

extracting and processing the ore and raw spodumene must be subjected to a temperature of

1000oC in order to effectively transform alpha to beta and facilitate percolation “using

sulphuric acid” (2). The next process involves recovering of lithium in form of lithium salts.

2.2.2 Cathode production

The materials that are used in making cathode are manufactured through oxidation of

lithium carbonate at a very high temperature. Another chemical used in the process is

Lithium hydroxide, which requires special handling during mixing process. Reactions in solid

state at a range of temperatures between 600 to 800oC are a fundamental requirement to

ensure there is maximum crystallization and that suitable structures are obtained (3). Iriyama

et al (7) assert that fossil energy is the most suitable for this process. Structural as well as

physical features like packing density and morphology are the key determinants in

pumping the brine into 4-5 ponds, addition of slake lime— to precipitate calcium and

magnesium salts— follow. This results to the production of magnesia and gypsum. When

more slake-lime is added to the successive ponds, depletion of calcium, magnesium, and

sodium salts occurs until brine with capacity of 0.5% lithium can be redirected to a

manufacturing plant that extracts lithium from lithium carbonate.

2.1.1.2 Spodumene

Another source of lithium is spodumene. Based on Gaines et al analysis (2),

spodumene is a mineral that consist of “lithium aluminium inosilicate— LiAl(SiO3)” (p.6).

Due to efficiency concerns, its production from minerals has drastically reduced. Eventually,

new cost-effective technique, which involves “production from salars,” has been discovered

(1). Nevertheless, producers still consider extraction from mineral deposits, in pursuit of

achieving supply diversification and reducing reliability of the external suppliers (4). Besides

extracting and processing the ore and raw spodumene must be subjected to a temperature of

1000oC in order to effectively transform alpha to beta and facilitate percolation “using

sulphuric acid” (2). The next process involves recovering of lithium in form of lithium salts.

2.2.2 Cathode production

The materials that are used in making cathode are manufactured through oxidation of

lithium carbonate at a very high temperature. Another chemical used in the process is

Lithium hydroxide, which requires special handling during mixing process. Reactions in solid

state at a range of temperatures between 600 to 800oC are a fundamental requirement to

ensure there is maximum crystallization and that suitable structures are obtained (3). Iriyama

et al (7) assert that fossil energy is the most suitable for this process. Structural as well as

physical features like packing density and morphology are the key determinants in

6

establishing the appropriateness of the material that should be used in cathode for Lithium-

ion cells (1).

2.2.3 Anode Production

The most commonly used materials in anode production are soft carbon, hard carbon,

graphite, and mesocarbon micro-bead (6). Essentially, a temperature of 2700oC is needed for

graphitization of synthetic graphite materials (2). The process involves huge consumption of

energy, particularly fossil fuels. In the recent past, there has been usage of amorphous carbon

layer as a robust way of protecting carbonaceous anode cells against corrosion during cell

working periods. According to Casas et al (8) process also involves usage of gas-phase

substances like methane and propylene, which need to be exposed to a temperature of 700oC

to crack them (1).

Other materials that have been widely used to supplant graphite anodes in the recent

past are components of “Lithium titanate (Li4Ti5O12).” Li4Ti5O12 is preferred due to its high-

energy supply. To produce Li4Ti5O1, a reaction of Titania—TiO2 and Li2CO3 is conducted in

crystalline structure, at a temperature of 859oC, in the air (1). The process is less energy-

intensive compared to the graphite production. Another advantage of Li4Ti5O1 is that it does

not react with the electrolyte. Li4Ti5O1 anode also allows faster charge/discharge, insofar as

the diffusion lengths are not long. However, for Li4Ti5O1 anode to be effective, according to

Oloffson (1), they have to be used with “high potential cathodes” to minimize the “open

circuit voltage (OCV)” (p.22). The weight of the material may also be disadvantageous in

locomotive purposes.

3.0 Inventory analysis

3.1 The process of assembling battery

establishing the appropriateness of the material that should be used in cathode for Lithium-

ion cells (1).

2.2.3 Anode Production

The most commonly used materials in anode production are soft carbon, hard carbon,

graphite, and mesocarbon micro-bead (6). Essentially, a temperature of 2700oC is needed for

graphitization of synthetic graphite materials (2). The process involves huge consumption of

energy, particularly fossil fuels. In the recent past, there has been usage of amorphous carbon

layer as a robust way of protecting carbonaceous anode cells against corrosion during cell

working periods. According to Casas et al (8) process also involves usage of gas-phase

substances like methane and propylene, which need to be exposed to a temperature of 700oC

to crack them (1).

Other materials that have been widely used to supplant graphite anodes in the recent

past are components of “Lithium titanate (Li4Ti5O12).” Li4Ti5O12 is preferred due to its high-

energy supply. To produce Li4Ti5O1, a reaction of Titania—TiO2 and Li2CO3 is conducted in

crystalline structure, at a temperature of 859oC, in the air (1). The process is less energy-

intensive compared to the graphite production. Another advantage of Li4Ti5O1 is that it does

not react with the electrolyte. Li4Ti5O1 anode also allows faster charge/discharge, insofar as

the diffusion lengths are not long. However, for Li4Ti5O1 anode to be effective, according to

Oloffson (1), they have to be used with “high potential cathodes” to minimize the “open

circuit voltage (OCV)” (p.22). The weight of the material may also be disadvantageous in

locomotive purposes.

3.0 Inventory analysis

3.1 The process of assembling battery

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

7

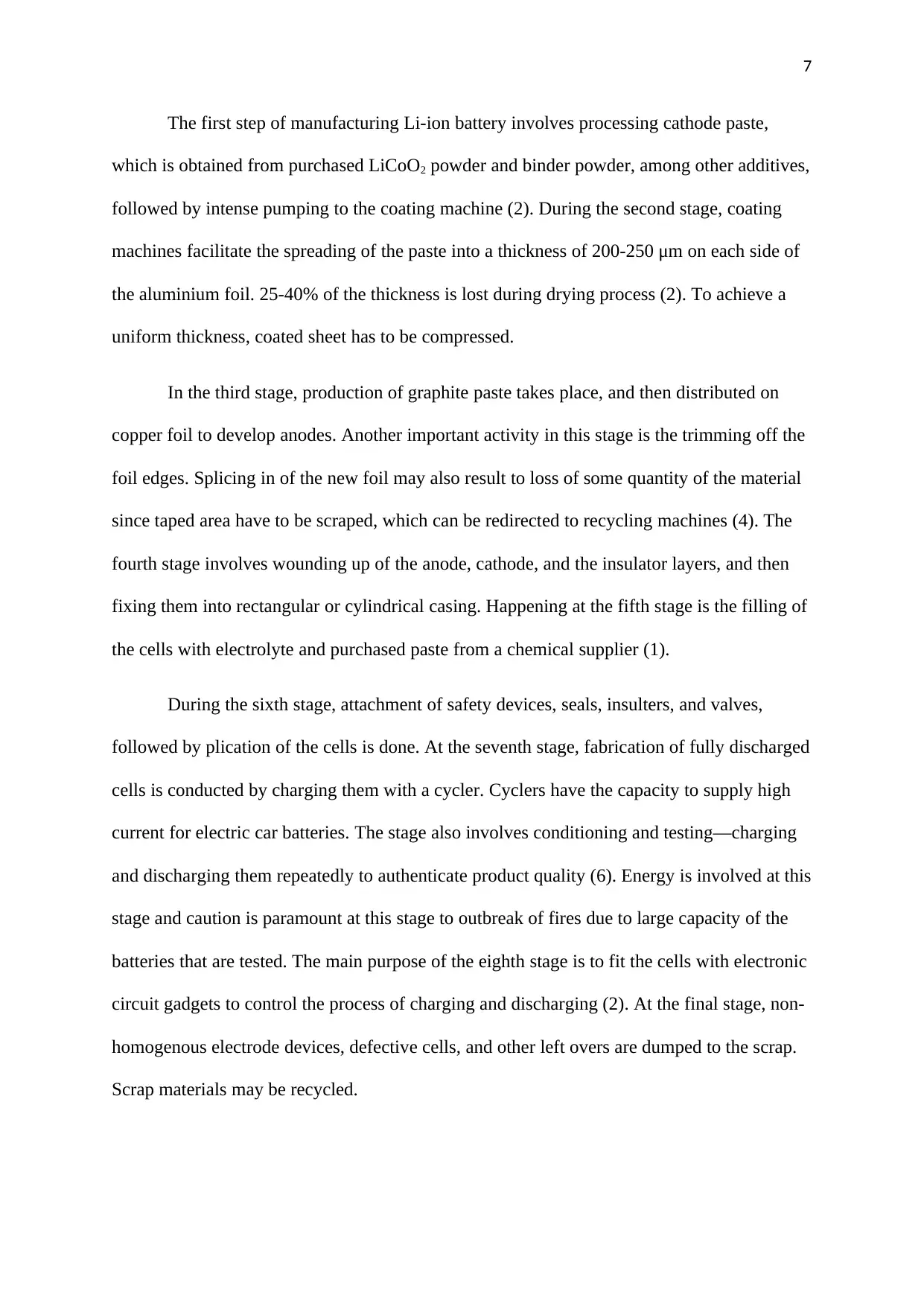

The first step of manufacturing Li-ion battery involves processing cathode paste,

which is obtained from purchased LiCoO2 powder and binder powder, among other additives,

followed by intense pumping to the coating machine (2). During the second stage, coating

machines facilitate the spreading of the paste into a thickness of 200-250 μm on each side of

the aluminium foil. 25-40% of the thickness is lost during drying process (2). To achieve a

uniform thickness, coated sheet has to be compressed.

In the third stage, production of graphite paste takes place, and then distributed on

copper foil to develop anodes. Another important activity in this stage is the trimming off the

foil edges. Splicing in of the new foil may also result to loss of some quantity of the material

since taped area have to be scraped, which can be redirected to recycling machines (4). The

fourth stage involves wounding up of the anode, cathode, and the insulator layers, and then

fixing them into rectangular or cylindrical casing. Happening at the fifth stage is the filling of

the cells with electrolyte and purchased paste from a chemical supplier (1).

During the sixth stage, attachment of safety devices, seals, insulters, and valves,

followed by plication of the cells is done. At the seventh stage, fabrication of fully discharged

cells is conducted by charging them with a cycler. Cyclers have the capacity to supply high

current for electric car batteries. The stage also involves conditioning and testing—charging

and discharging them repeatedly to authenticate product quality (6). Energy is involved at this

stage and caution is paramount at this stage to outbreak of fires due to large capacity of the

batteries that are tested. The main purpose of the eighth stage is to fit the cells with electronic

circuit gadgets to control the process of charging and discharging (2). At the final stage, non-

homogenous electrode devices, defective cells, and other left overs are dumped to the scrap.

Scrap materials may be recycled.

The first step of manufacturing Li-ion battery involves processing cathode paste,

which is obtained from purchased LiCoO2 powder and binder powder, among other additives,

followed by intense pumping to the coating machine (2). During the second stage, coating

machines facilitate the spreading of the paste into a thickness of 200-250 μm on each side of

the aluminium foil. 25-40% of the thickness is lost during drying process (2). To achieve a

uniform thickness, coated sheet has to be compressed.

In the third stage, production of graphite paste takes place, and then distributed on

copper foil to develop anodes. Another important activity in this stage is the trimming off the

foil edges. Splicing in of the new foil may also result to loss of some quantity of the material

since taped area have to be scraped, which can be redirected to recycling machines (4). The

fourth stage involves wounding up of the anode, cathode, and the insulator layers, and then

fixing them into rectangular or cylindrical casing. Happening at the fifth stage is the filling of

the cells with electrolyte and purchased paste from a chemical supplier (1).

During the sixth stage, attachment of safety devices, seals, insulters, and valves,

followed by plication of the cells is done. At the seventh stage, fabrication of fully discharged

cells is conducted by charging them with a cycler. Cyclers have the capacity to supply high

current for electric car batteries. The stage also involves conditioning and testing—charging

and discharging them repeatedly to authenticate product quality (6). Energy is involved at this

stage and caution is paramount at this stage to outbreak of fires due to large capacity of the

batteries that are tested. The main purpose of the eighth stage is to fit the cells with electronic

circuit gadgets to control the process of charging and discharging (2). At the final stage, non-

homogenous electrode devices, defective cells, and other left overs are dumped to the scrap.

Scrap materials may be recycled.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

8

Figure 1: Battery assembly process

Source: Iriyama, Yasutoshi, and Zempachi Ogumi. Solid Electrode–Inorganic Solid

Electrolyte Interface for Advanced All-Solid-State Rechargeable Lithium Batteries.

3.2 Recycling of Li-ion battery

Recycling of batteries has become more dynamic due to diversification of feedstock,

which includes several types of batteries, some of which are inimical to human health in

particular and the environment in general. According to Gaines (2), “recycling electronic

consumer batteries” keeps the companies operational until car batteries are disposed for

Figure 1: Battery assembly process

Source: Iriyama, Yasutoshi, and Zempachi Ogumi. Solid Electrode–Inorganic Solid

Electrolyte Interface for Advanced All-Solid-State Rechargeable Lithium Batteries.

3.2 Recycling of Li-ion battery

Recycling of batteries has become more dynamic due to diversification of feedstock,

which includes several types of batteries, some of which are inimical to human health in

particular and the environment in general. According to Gaines (2), “recycling electronic

consumer batteries” keeps the companies operational until car batteries are disposed for

9

recycling in huge volumes (p.9). The disposal of automotive batteries makes the recycling

process efficient and improves standardization exercise. Income obtained from cobalt

recovery stimulates the recycling process (3). However, due to decline in the use of cobalt,

other initiatives to make the recycling process lucrative business must be identified.

Through the recycling process, several materials can be recovered at different stages

of production. For instance, smelting process has the efficacy to retrieve the basic elements

and salts. Smelting process occurs at very high temperatures and involves burning of carbon

anodes and electrolytes as reductant (2). Cobalt and nickel, which are the valuable metals

recovered from the process, are redirected to the refining plant to make them more conducive

for any purpose. Other elements that are contained in the slag like lithium are used for

additive function. Hydrometallurgical process is the main method that is used to recover

lithium from the slag (2). The process of recovering battery grade materials demands a high

uniform feed since contamination of the feed with impurities may be detrimental to the

product quality. Therefore, component must be separated through effective variety of

chemical and physical technique to ensure that all active elements are recovered. Other active

materials may need to be purification to make them appropriate for reuse in new battery cells.

However, the separator cannot be reused since its material cannot be recycled. While many

papers have discussed recycling of Lithium-ion batteries, only a few companies, 3 to be

exact, have detailed germane information that could be used in current analysis. These

processes are analysed below:

3.2.1 Umicore Process

Umicore is a European battery processing company. It gathers used batteries and

dispose them to its processing plant, which is designated in Sweden. Once the materials are

collected, they are smelted. The next step is combustion of organic materials in the batteries

recycling in huge volumes (p.9). The disposal of automotive batteries makes the recycling

process efficient and improves standardization exercise. Income obtained from cobalt

recovery stimulates the recycling process (3). However, due to decline in the use of cobalt,

other initiatives to make the recycling process lucrative business must be identified.

Through the recycling process, several materials can be recovered at different stages

of production. For instance, smelting process has the efficacy to retrieve the basic elements

and salts. Smelting process occurs at very high temperatures and involves burning of carbon

anodes and electrolytes as reductant (2). Cobalt and nickel, which are the valuable metals

recovered from the process, are redirected to the refining plant to make them more conducive

for any purpose. Other elements that are contained in the slag like lithium are used for

additive function. Hydrometallurgical process is the main method that is used to recover

lithium from the slag (2). The process of recovering battery grade materials demands a high

uniform feed since contamination of the feed with impurities may be detrimental to the

product quality. Therefore, component must be separated through effective variety of

chemical and physical technique to ensure that all active elements are recovered. Other active

materials may need to be purification to make them appropriate for reuse in new battery cells.

However, the separator cannot be reused since its material cannot be recycled. While many

papers have discussed recycling of Lithium-ion batteries, only a few companies, 3 to be

exact, have detailed germane information that could be used in current analysis. These

processes are analysed below:

3.2.1 Umicore Process

Umicore is a European battery processing company. It gathers used batteries and

dispose them to its processing plant, which is designated in Sweden. Once the materials are

collected, they are smelted. The next step is combustion of organic materials in the batteries

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

10

like carbon electrodes, plastics, and electrolyte solvents. The combustion steers the smelter

and carbon is used a reductant for some metals. Recovered elements, nickel and cobalt, are

shipped to a refinery plant in Belgium, where CoCl2 is manufactured. After processing CoCl2,

it is transported to South Korea to manufacture LiCoO2 for battery cells. Recovery of nickel

and cobalt helps makes the process efficient, considering that at least 70% of the energy

required for their extraction from the sulphide ores is saved. The production process also

prevents emission of Sulphur oxide gase. However, the aluminium and lithium elements from

the smelting process flows into the slag, which has low value uses. The subjection of waste

gases to extremely high temperatures ensures that they are not released into the environment.

According to the company, out of 93% recovered lithium-ion batteries, 69% is metal, 10% is

carbon, and 14% is plastic (2).

Figure 2: Umicore process

3.2.2 The Toxco Process

This method has been commonly used in battery processing since 1993 in Canada to

manufacture Lithium-ion batteries for different purposes (3). In 2009, Toxco Company was

granted a licence by the US Department of Energy to reprocess Lithium-ion battery cells at

like carbon electrodes, plastics, and electrolyte solvents. The combustion steers the smelter

and carbon is used a reductant for some metals. Recovered elements, nickel and cobalt, are

shipped to a refinery plant in Belgium, where CoCl2 is manufactured. After processing CoCl2,

it is transported to South Korea to manufacture LiCoO2 for battery cells. Recovery of nickel

and cobalt helps makes the process efficient, considering that at least 70% of the energy

required for their extraction from the sulphide ores is saved. The production process also

prevents emission of Sulphur oxide gase. However, the aluminium and lithium elements from

the smelting process flows into the slag, which has low value uses. The subjection of waste

gases to extremely high temperatures ensures that they are not released into the environment.

According to the company, out of 93% recovered lithium-ion batteries, 69% is metal, 10% is

carbon, and 14% is plastic (2).

Figure 2: Umicore process

3.2.2 The Toxco Process

This method has been commonly used in battery processing since 1993 in Canada to

manufacture Lithium-ion batteries for different purposes (3). In 2009, Toxco Company was

granted a licence by the US Department of Energy to reprocess Lithium-ion battery cells at

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

11

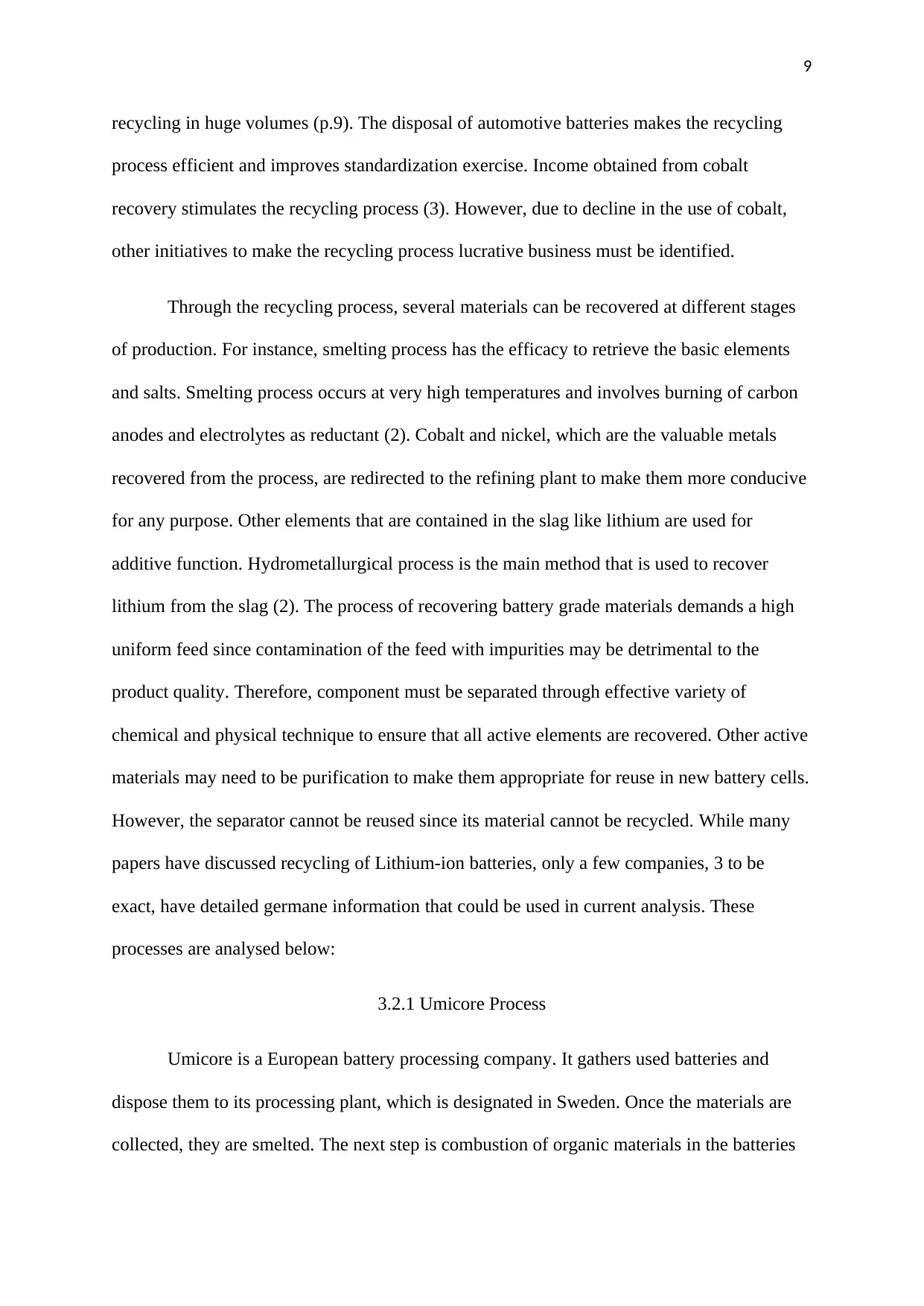

plant designated at Ohio (2). Through mechanical and chemical recycling process, products

obtained from the process are “copper cobalt, fluff, and cobalt filter cake” (2). Copper cobalt

is used to extract metals like copper, cobalt, nickel, and aluminium. On the other hand, cobalt

filter cake is reused to coat appliances. Sodium Chloride was added to the resultant solution

in order to precipitate Li2Co3. The mechanical and chemical recycling process ensures that the

emission is minimized. One benefit of this process is that it is not energy-intensive. Besides,

it is possible to recycle at least 60% of the battery pack materials and 10 percent reused. The

fluff consists of 25% of the battery pack: it is first landfilled, and then the plastic can be

retrieved when their capacity is high enough to ensure there is efficiency (2).

Figure 3: the Toxco process

So

urce: Dunn, Jennifer B., and Linda Gaines. Life Cycle Analysis Summary for Automotive

Lithium-Ion Battery Production and Recycling. REWAS 2016, 2016

3.2.3 Eco-Bat Process

Orengon Company is the developer of this process. The company has partnered with

RSR, a recycling company in Texas. Eco-Bat process consumes less energy hence it more

plant designated at Ohio (2). Through mechanical and chemical recycling process, products

obtained from the process are “copper cobalt, fluff, and cobalt filter cake” (2). Copper cobalt

is used to extract metals like copper, cobalt, nickel, and aluminium. On the other hand, cobalt

filter cake is reused to coat appliances. Sodium Chloride was added to the resultant solution

in order to precipitate Li2Co3. The mechanical and chemical recycling process ensures that the

emission is minimized. One benefit of this process is that it is not energy-intensive. Besides,

it is possible to recycle at least 60% of the battery pack materials and 10 percent reused. The

fluff consists of 25% of the battery pack: it is first landfilled, and then the plastic can be

retrieved when their capacity is high enough to ensure there is efficiency (2).

Figure 3: the Toxco process

So

urce: Dunn, Jennifer B., and Linda Gaines. Life Cycle Analysis Summary for Automotive

Lithium-Ion Battery Production and Recycling. REWAS 2016, 2016

3.2.3 Eco-Bat Process

Orengon Company is the developer of this process. The company has partnered with

RSR, a recycling company in Texas. Eco-Bat process consumes less energy hence it more

12

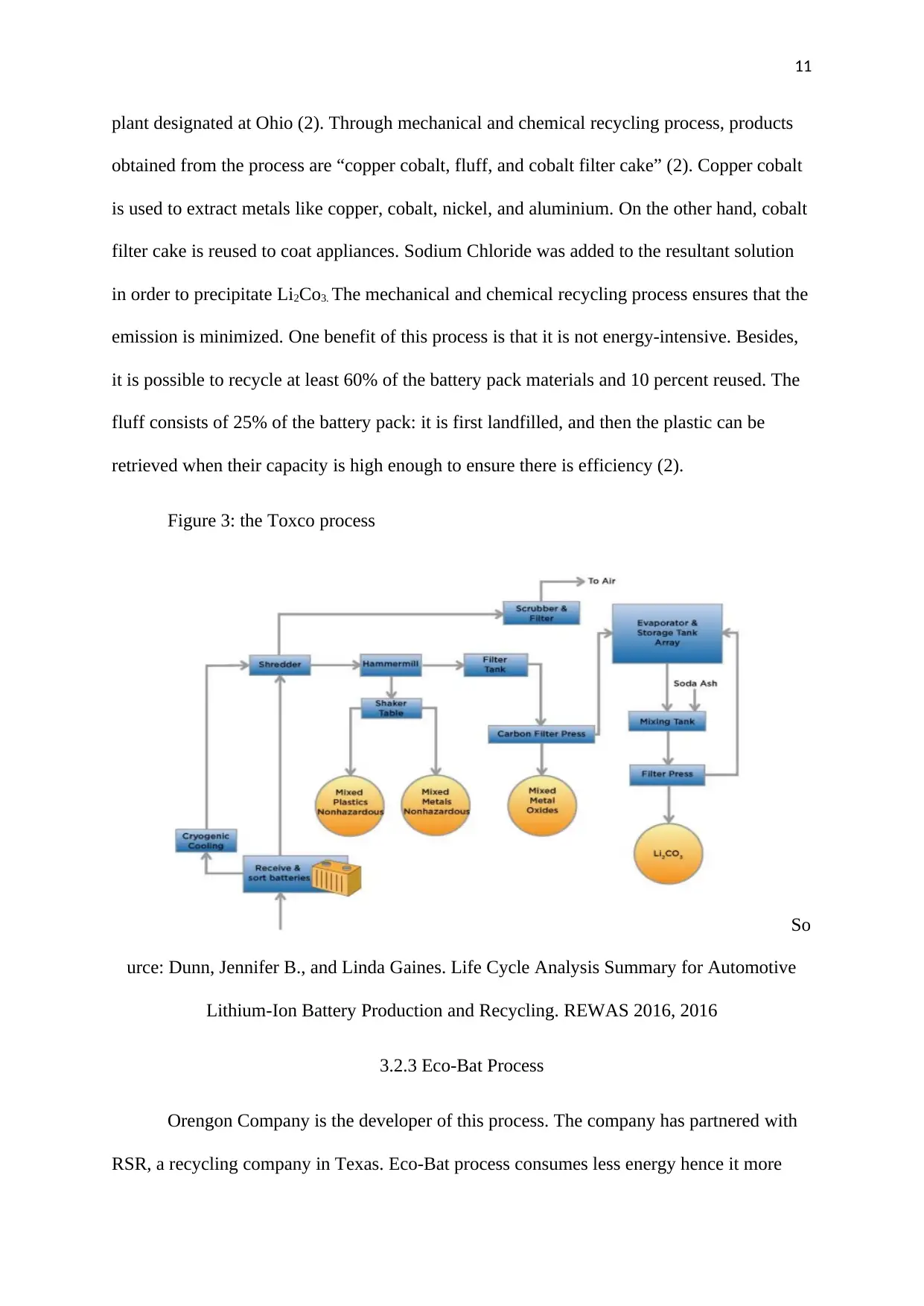

efficient. The process involves reusing of electrolyte solvent and salts. Like other recycling

processes, reusing the separator is impossible. The metal elements are retrieved and used for

recycling. Battery pack casing may also be reused, but the process will depend on the system

of configuration in place. The process is a quintessentially possibility of design-for-recycling

method. Extraction of electrolyte if facilitated by using supercritical CO2, which carries away

the salt and can be reused. The CO2 used in this process can be obtained from burning waste.

The leftovers from the structure can be broken down into small fragments to enhance the

separation process. This process ensures that active elements are recovered and the new

battery is manufactured with minimal treatment. About 80% of the materials used in the

process can be recycle. However, the method requires additional separation process to

process a mixed feed and to produce high quality final products.

Figure 4: Eco-Bat Process

4.0 Impact analysis

4.1 Comparison to total Life-Cycle Energy

efficient. The process involves reusing of electrolyte solvent and salts. Like other recycling

processes, reusing the separator is impossible. The metal elements are retrieved and used for

recycling. Battery pack casing may also be reused, but the process will depend on the system

of configuration in place. The process is a quintessentially possibility of design-for-recycling

method. Extraction of electrolyte if facilitated by using supercritical CO2, which carries away

the salt and can be reused. The CO2 used in this process can be obtained from burning waste.

The leftovers from the structure can be broken down into small fragments to enhance the

separation process. This process ensures that active elements are recovered and the new

battery is manufactured with minimal treatment. About 80% of the materials used in the

process can be recycle. However, the method requires additional separation process to

process a mixed feed and to produce high quality final products.

Figure 4: Eco-Bat Process

4.0 Impact analysis

4.1 Comparison to total Life-Cycle Energy

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 15

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.