Statistical Analysis of a Mental Health Wellbeing Study: Findings

VerifiedAdded on 2020/04/13

|12

|1757

|293

Report

AI Summary

This report presents an analysis of a mental health study that investigated the impact of exercise sessions on the mental wellbeing of women. The study compared two groups: an intervention group receiving exercise sessions and a control group. Data was collected at three time points, measuring Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) scores, steps per day, and BMI. The analysis included descriptive statistics, hypothesis testing to determine the effects of exercise on mental wellbeing, and assessment of the association between physical activity stages and the participant's group. The results indicated a significant positive correlation between exercise and mental wellbeing. Age was also examined as a potential confounder. The report provides detailed statistical findings and concludes that exercise sessions have a positive impact on mental wellbeing.

Measuring Positive Mental Health 1

Mental Health – Measuring Positive Mental Health

Name

Course Number

Date

Faculty Name

Mental Health – Measuring Positive Mental Health

Name

Course Number

Date

Faculty Name

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Measuring Positive Mental Health 2

Mental Health – Measuring Positive Mental Health

Introduction

Mental health status can be measured based on predetermined scale(s), which focus on

the state of human mind during a specified period. Several factors determine the mental state of

an individual amongst which include physical exercises and age among other possible

confounders such as gender and ethnicity (NHS Health Scotland, 2017). Observations and tests

are required to determine the mental state of a person. It is believed that people who engage in

more physical activities are more likely to have better mental health compared to their fellows

(Pratt, 2013). In this study, two groups of women will be compared on basis of their mental

status. The groups include those studied at baseline and were not involved in any form of

physical activities and the others received free sessions, hence the intervention group.

Information recorded for purposes of research analysis based on the three periods for the two

groups (Elder, Evans and Nizette, 2009). The aim of the analysis is to see whether there is a

correlation between the amount of activity and their Mental Health wellbeing score. Their BMI

is monitored for change to see whether the activity has an effect on it. Participants are monitored

from pre-contemplation to maintenance level using a pedometer. Physical activity stage of

change (PASOC) is checked at 3, 12 and 24 months.

Research Questions

1. Does Offering exercise sessions to the physically restricted help encourage and maintain

a healthy mental wellbeing state?

The wellbeing of a person is affected by the physical state of the body. Therefore, increasing

the rate physical activities, the chance of mental state improvements is elevated (Choi, 2014).

2. Is there a significant association between physical activity stage of change at each time

point 1, 2 & 3 and offering exercise sessions?

Due to the expected changes in physical activity stage of change between the groups, we

presume that there will be a significant association between the participant's groups and the

physical activity stage (Choi, 2014).

3. Is age a confounder for the prediction of a participant’s group using the measurements of

the third recording as the predictors?

Mental Health – Measuring Positive Mental Health

Introduction

Mental health status can be measured based on predetermined scale(s), which focus on

the state of human mind during a specified period. Several factors determine the mental state of

an individual amongst which include physical exercises and age among other possible

confounders such as gender and ethnicity (NHS Health Scotland, 2017). Observations and tests

are required to determine the mental state of a person. It is believed that people who engage in

more physical activities are more likely to have better mental health compared to their fellows

(Pratt, 2013). In this study, two groups of women will be compared on basis of their mental

status. The groups include those studied at baseline and were not involved in any form of

physical activities and the others received free sessions, hence the intervention group.

Information recorded for purposes of research analysis based on the three periods for the two

groups (Elder, Evans and Nizette, 2009). The aim of the analysis is to see whether there is a

correlation between the amount of activity and their Mental Health wellbeing score. Their BMI

is monitored for change to see whether the activity has an effect on it. Participants are monitored

from pre-contemplation to maintenance level using a pedometer. Physical activity stage of

change (PASOC) is checked at 3, 12 and 24 months.

Research Questions

1. Does Offering exercise sessions to the physically restricted help encourage and maintain

a healthy mental wellbeing state?

The wellbeing of a person is affected by the physical state of the body. Therefore, increasing

the rate physical activities, the chance of mental state improvements is elevated (Choi, 2014).

2. Is there a significant association between physical activity stage of change at each time

point 1, 2 & 3 and offering exercise sessions?

Due to the expected changes in physical activity stage of change between the groups, we

presume that there will be a significant association between the participant's groups and the

physical activity stage (Choi, 2014).

3. Is age a confounder for the prediction of a participant’s group using the measurements of

the third recording as the predictors?

Measuring Positive Mental Health 3

The rate of physical exercises gradually reduces as women get to older ages. Therefore, age

is a possible confounder in the prediction of whether a participant in the control or intervention

group (Sedgwick, 2013).

Specific Hypothesis

1. Offering exercise sessions to the physically restricted help encourage and maintain a

healthy mental wellbeing state

Null hypothesis: Offering exercise sessions has no effect on encouraging or maintaining a

healthy mental Wellbeing state

2. The physical state of change at each time is proportionally related to offering exercise

sessions

Null hypothesis: There is no association between offering exercise and the physical state of

change.

3. Age is a potential confounder in the modelling of individuals benefiting from exercise

sessions

Null hypothesis: Age is not a confounder in the modelling of individuals benefiting from

exercise sessions

Descriptive Statistics

There were 89 (32.5%) participants in the intervention group and 185 (67.5%) in the control

group.

Table 1: Disability, its effects in activities and promotion of parents/guardians

Yes No N/A

Disability? 37 (13.5%) 237 (86.5%)

Disability Limit Activity? 28 (10.2%) 10 (3.6%) 236 (86.1%)

Parent/Guardian? 181 (66.1%) 93 (33.9%)

Table 2: Physical activity stage summary

Physical activity stage

Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3

Pre-contemplation 12 (4.4%) 10 (3.6%) 7 (2.6%)

The rate of physical exercises gradually reduces as women get to older ages. Therefore, age

is a possible confounder in the prediction of whether a participant in the control or intervention

group (Sedgwick, 2013).

Specific Hypothesis

1. Offering exercise sessions to the physically restricted help encourage and maintain a

healthy mental wellbeing state

Null hypothesis: Offering exercise sessions has no effect on encouraging or maintaining a

healthy mental Wellbeing state

2. The physical state of change at each time is proportionally related to offering exercise

sessions

Null hypothesis: There is no association between offering exercise and the physical state of

change.

3. Age is a potential confounder in the modelling of individuals benefiting from exercise

sessions

Null hypothesis: Age is not a confounder in the modelling of individuals benefiting from

exercise sessions

Descriptive Statistics

There were 89 (32.5%) participants in the intervention group and 185 (67.5%) in the control

group.

Table 1: Disability, its effects in activities and promotion of parents/guardians

Yes No N/A

Disability? 37 (13.5%) 237 (86.5%)

Disability Limit Activity? 28 (10.2%) 10 (3.6%) 236 (86.1%)

Parent/Guardian? 181 (66.1%) 93 (33.9%)

Table 2: Physical activity stage summary

Physical activity stage

Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3

Pre-contemplation 12 (4.4%) 10 (3.6%) 7 (2.6%)

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Measuring Positive Mental Health 4

Contemplation 58 (21.2%) 50 (18.2%) 22 (8%)

Preparation 47 (17.2%) 45 16.4%) 77 (28.1%)

Decision/Action 19 (6.9%) 28 (10.2%) 37 (13.5%)

Maintenance 138 (50.4%) 141 (51.5%) 131 (47.8%)

Table 3: Employment status summary

Frequency

Employed 173 (63.1%)

Unemployed 28 (10.2%)

Self-employed 7 (2.6%)

Student 19 (6.6%)

Carer 5 (1.8%)

Retired 42 (15.3%)

63.1% of the women who participated in the study were employed, 10.2% unemployed, 2.6%

self-employed, 6.6% were students, 1.8% carers and 15.3% were retired.

Table 4: Age distribution of the participants

Mean Standard Deviation Minimum Maximum

Age 43.39 15.27 16 89

Contemplation 58 (21.2%) 50 (18.2%) 22 (8%)

Preparation 47 (17.2%) 45 16.4%) 77 (28.1%)

Decision/Action 19 (6.9%) 28 (10.2%) 37 (13.5%)

Maintenance 138 (50.4%) 141 (51.5%) 131 (47.8%)

Table 3: Employment status summary

Frequency

Employed 173 (63.1%)

Unemployed 28 (10.2%)

Self-employed 7 (2.6%)

Student 19 (6.6%)

Carer 5 (1.8%)

Retired 42 (15.3%)

63.1% of the women who participated in the study were employed, 10.2% unemployed, 2.6%

self-employed, 6.6% were students, 1.8% carers and 15.3% were retired.

Table 4: Age distribution of the participants

Mean Standard Deviation Minimum Maximum

Age 43.39 15.27 16 89

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Measuring Positive Mental Health 5

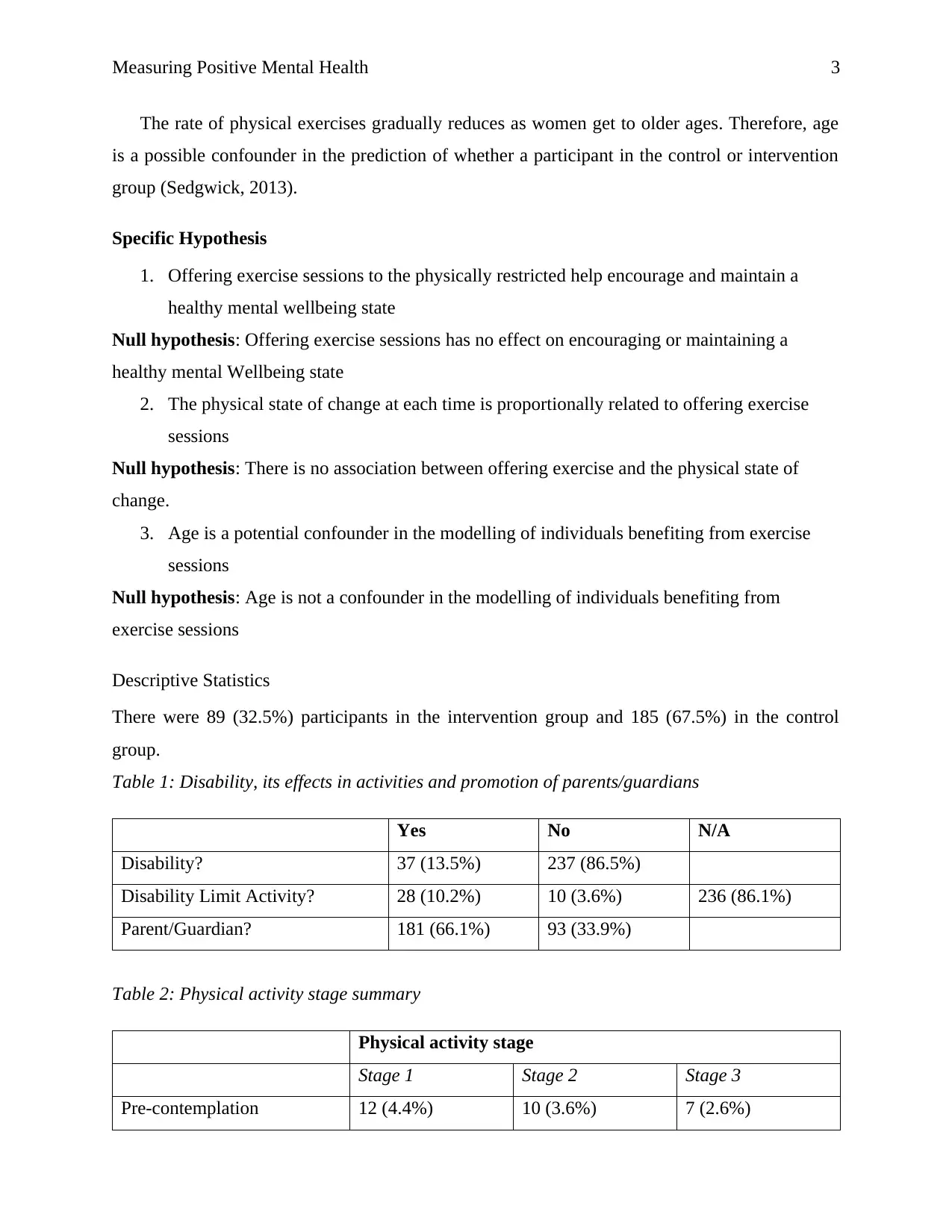

Figure 1: Distribution of age in baseline and session groups

The average is a woman who participated in the study was 43.39years with a standard deviation

of 15.27years. The distribution of age between the two groups is approximately normal.

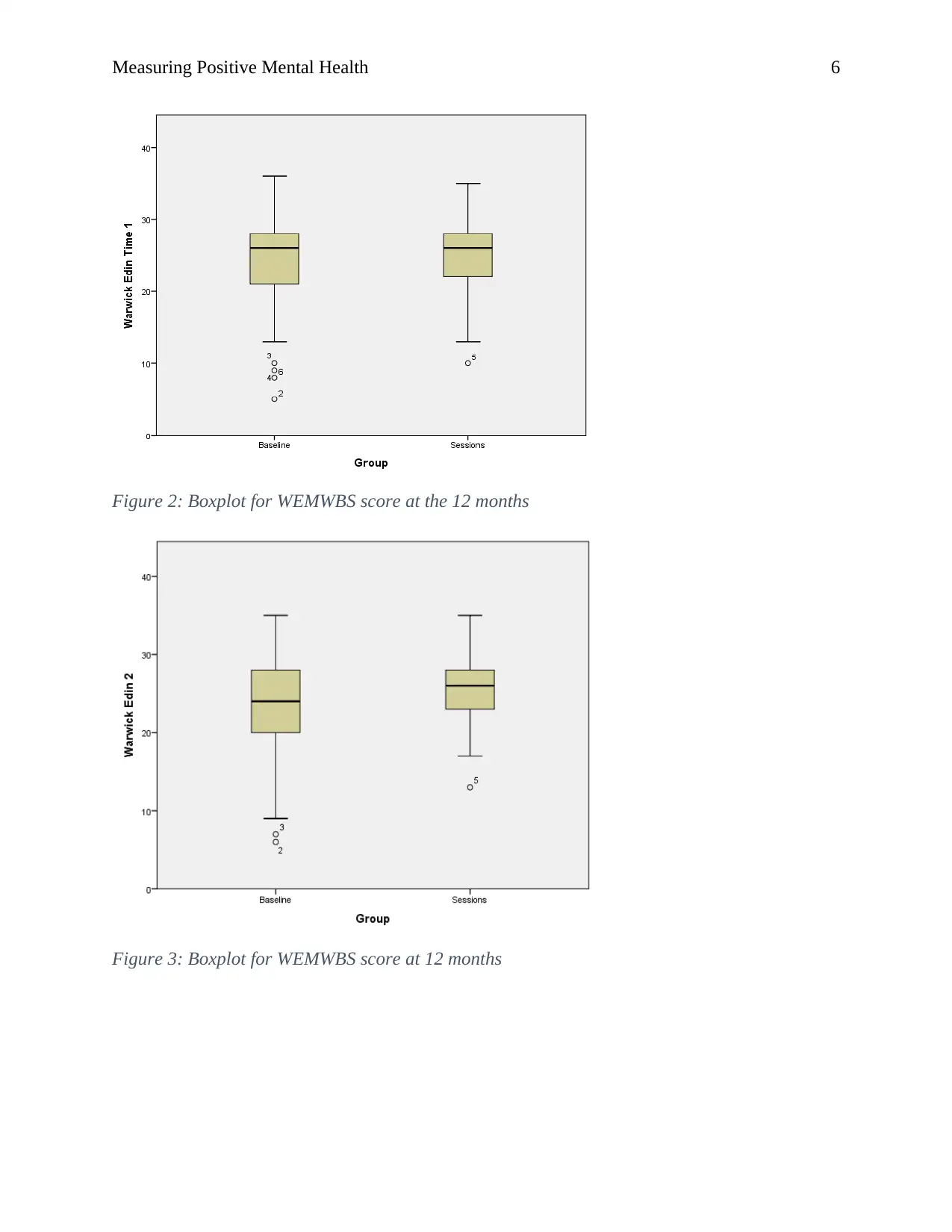

Table 5: Distribution of Warwick Edinburgh wellbeing score, steps per day and BMI

Time of recording, mean and standard deviation

3 Months 12 Months 24 Months

Mean S.D Mean S.D Mean S.D

Warwick Edinburgh score 24.66 5.53 24.52 5.026 25.32 5.425

Steps per day 8,985.9 389.86 10,105.62 414.59 11,022.36 396.27

BMI 24.44 5.18 25.15 6.48

Figure 1: Distribution of age in baseline and session groups

The average is a woman who participated in the study was 43.39years with a standard deviation

of 15.27years. The distribution of age between the two groups is approximately normal.

Table 5: Distribution of Warwick Edinburgh wellbeing score, steps per day and BMI

Time of recording, mean and standard deviation

3 Months 12 Months 24 Months

Mean S.D Mean S.D Mean S.D

Warwick Edinburgh score 24.66 5.53 24.52 5.026 25.32 5.425

Steps per day 8,985.9 389.86 10,105.62 414.59 11,022.36 396.27

BMI 24.44 5.18 25.15 6.48

Measuring Positive Mental Health 6

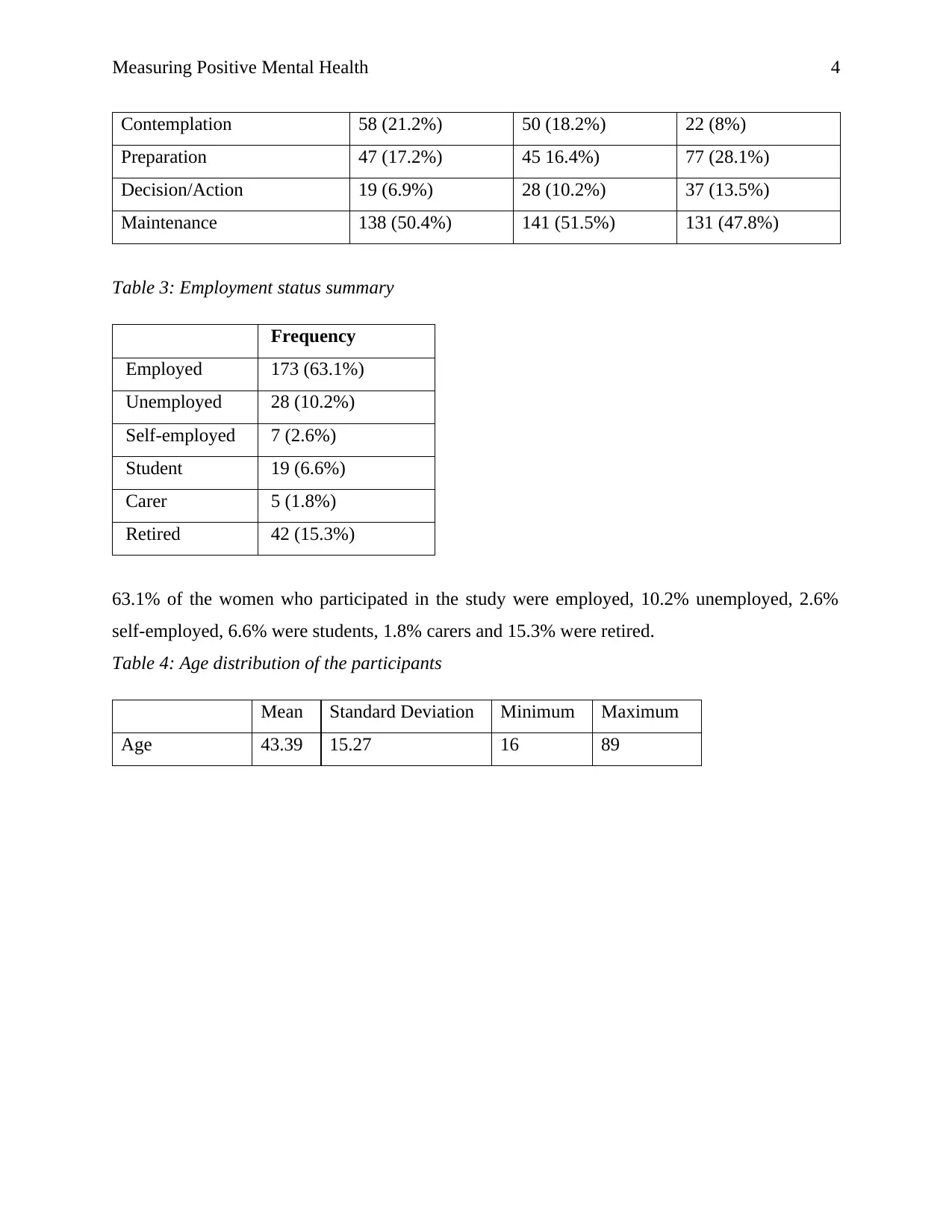

Figure 2: Boxplot for WEMWBS score at the 12 months

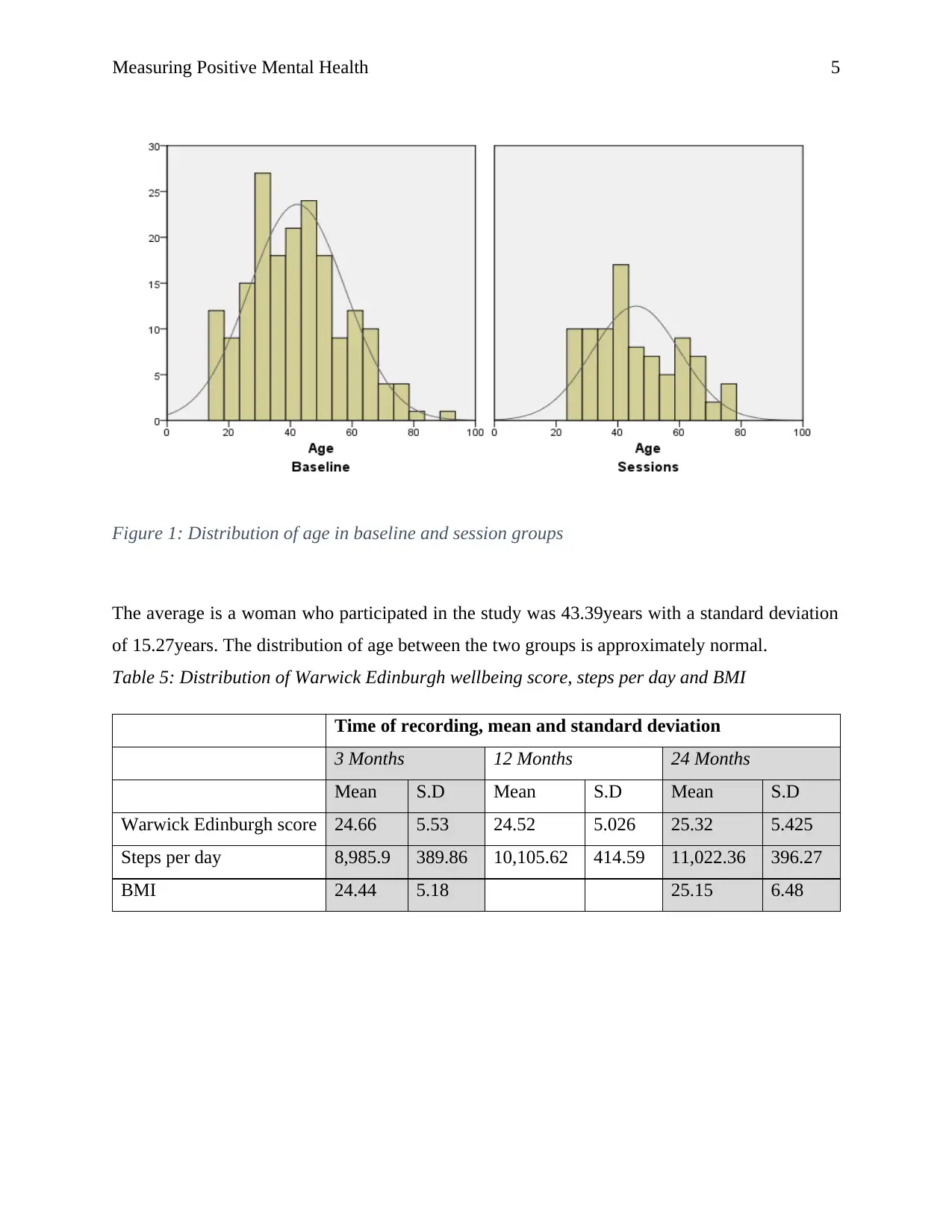

Figure 3: Boxplot for WEMWBS score at 12 months

Figure 2: Boxplot for WEMWBS score at the 12 months

Figure 3: Boxplot for WEMWBS score at 12 months

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Measuring Positive Mental Health 7

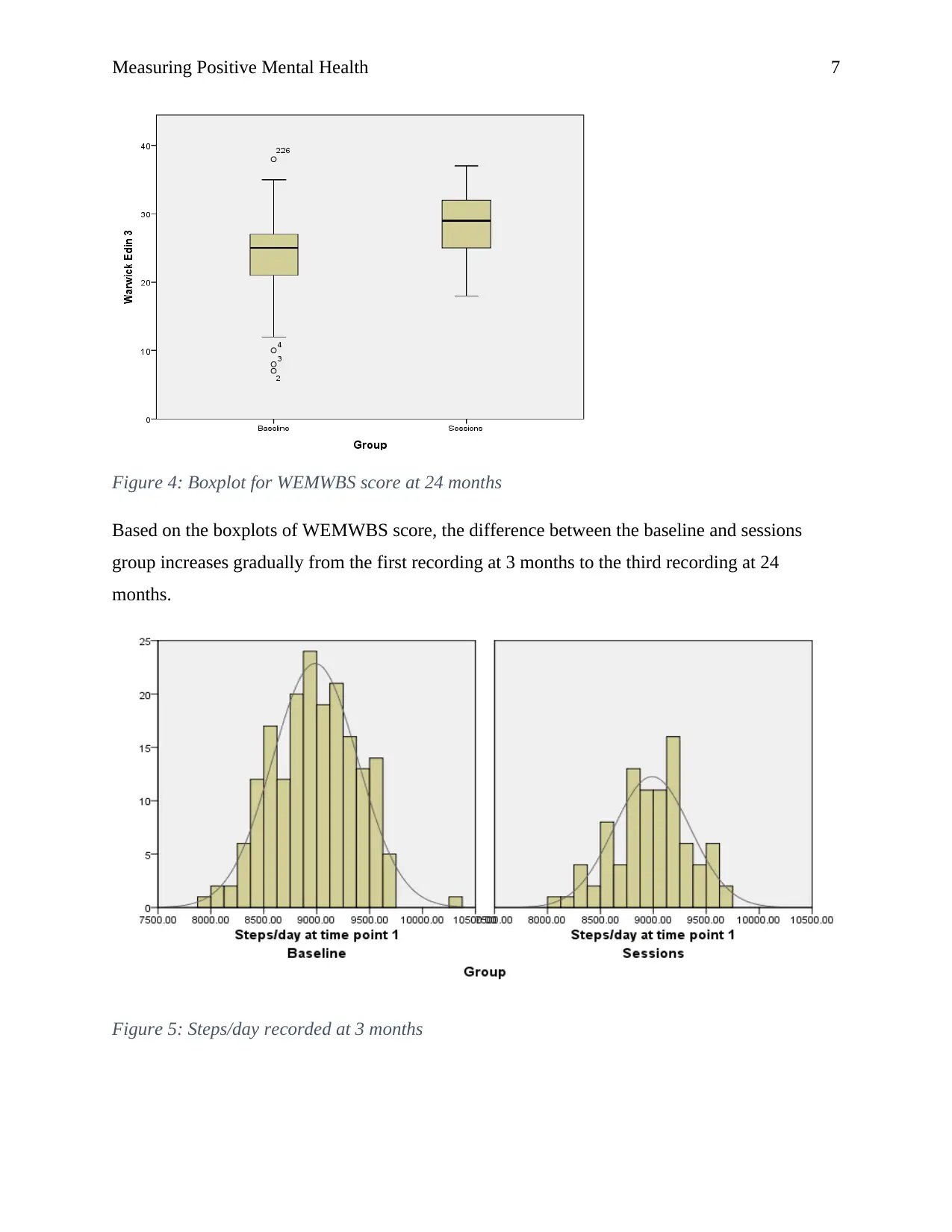

Figure 4: Boxplot for WEMWBS score at 24 months

Based on the boxplots of WEMWBS score, the difference between the baseline and sessions

group increases gradually from the first recording at 3 months to the third recording at 24

months.

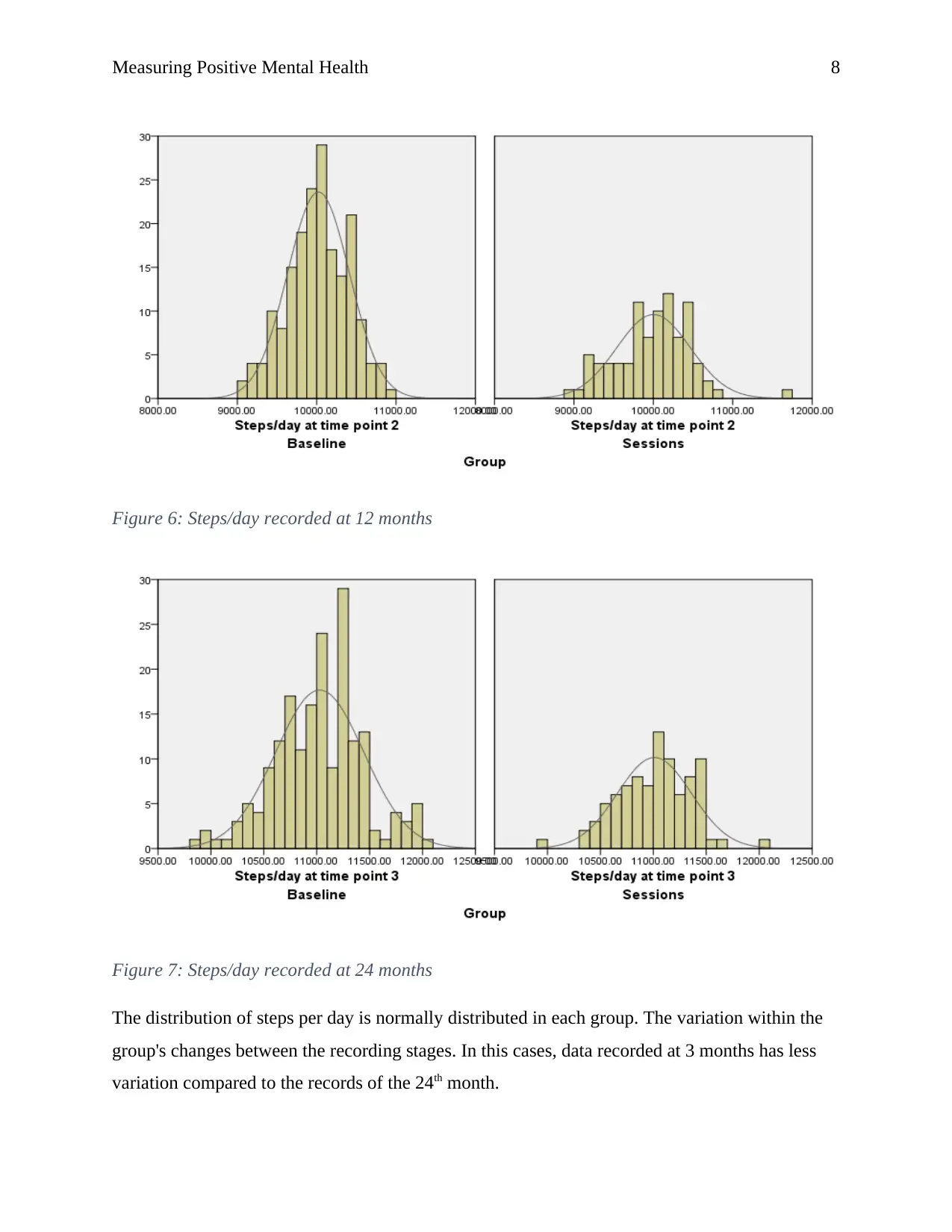

Figure 5: Steps/day recorded at 3 months

Figure 4: Boxplot for WEMWBS score at 24 months

Based on the boxplots of WEMWBS score, the difference between the baseline and sessions

group increases gradually from the first recording at 3 months to the third recording at 24

months.

Figure 5: Steps/day recorded at 3 months

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Measuring Positive Mental Health 8

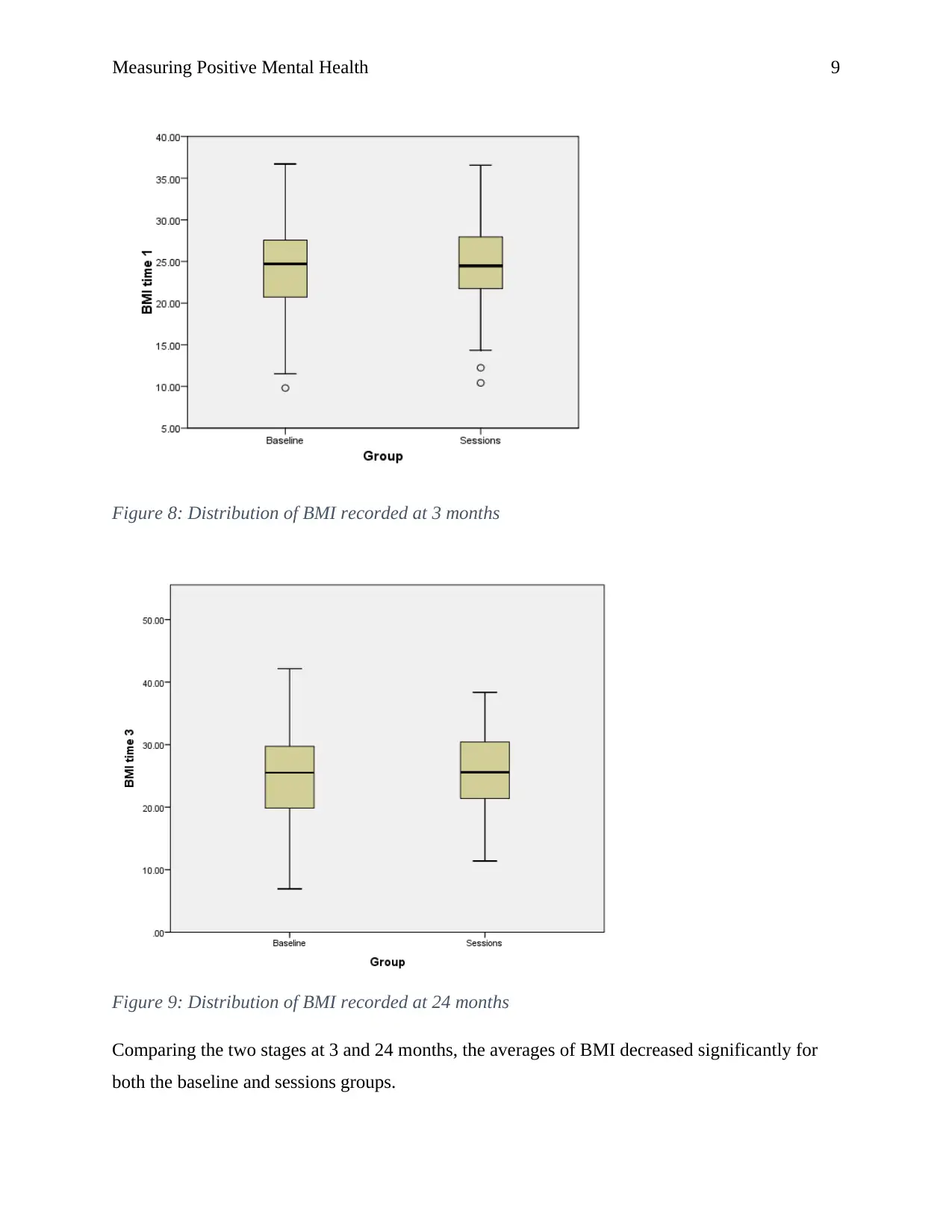

Figure 6: Steps/day recorded at 12 months

Figure 7: Steps/day recorded at 24 months

The distribution of steps per day is normally distributed in each group. The variation within the

group's changes between the recording stages. In this cases, data recorded at 3 months has less

variation compared to the records of the 24th month.

Figure 6: Steps/day recorded at 12 months

Figure 7: Steps/day recorded at 24 months

The distribution of steps per day is normally distributed in each group. The variation within the

group's changes between the recording stages. In this cases, data recorded at 3 months has less

variation compared to the records of the 24th month.

Measuring Positive Mental Health 9

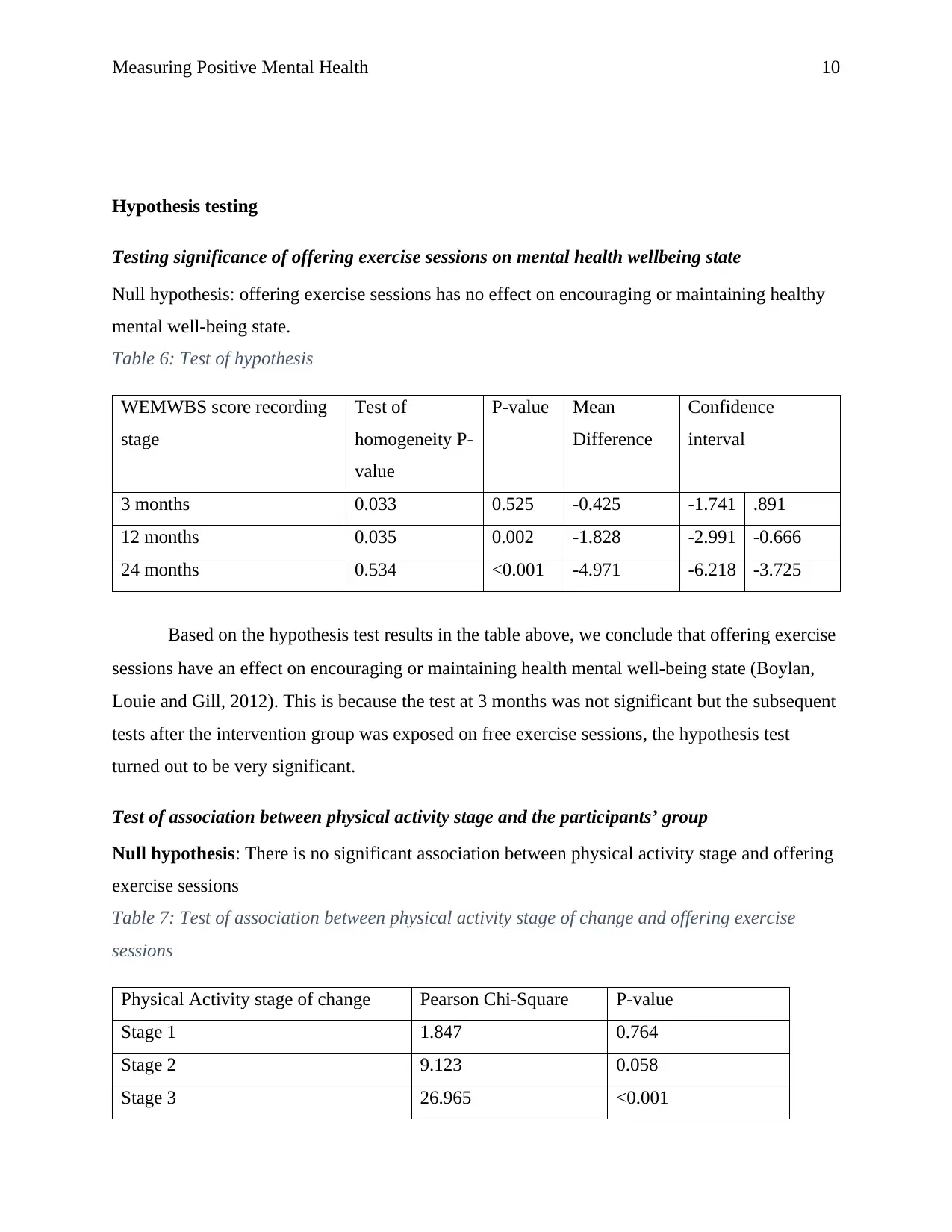

Figure 8: Distribution of BMI recorded at 3 months

Figure 9: Distribution of BMI recorded at 24 months

Comparing the two stages at 3 and 24 months, the averages of BMI decreased significantly for

both the baseline and sessions groups.

Figure 8: Distribution of BMI recorded at 3 months

Figure 9: Distribution of BMI recorded at 24 months

Comparing the two stages at 3 and 24 months, the averages of BMI decreased significantly for

both the baseline and sessions groups.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Measuring Positive Mental Health 10

Hypothesis testing

Testing significance of offering exercise sessions on mental health wellbeing state

Null hypothesis: offering exercise sessions has no effect on encouraging or maintaining healthy

mental well-being state.

Table 6: Test of hypothesis

WEMWBS score recording

stage

Test of

homogeneity P-

value

P-value Mean

Difference

Confidence

interval

3 months 0.033 0.525 -0.425 -1.741 .891

12 months 0.035 0.002 -1.828 -2.991 -0.666

24 months 0.534 <0.001 -4.971 -6.218 -3.725

Based on the hypothesis test results in the table above, we conclude that offering exercise

sessions have an effect on encouraging or maintaining health mental well-being state (Boylan,

Louie and Gill, 2012). This is because the test at 3 months was not significant but the subsequent

tests after the intervention group was exposed on free exercise sessions, the hypothesis test

turned out to be very significant.

Test of association between physical activity stage and the participants’ group

Null hypothesis: There is no significant association between physical activity stage and offering

exercise sessions

Table 7: Test of association between physical activity stage of change and offering exercise

sessions

Physical Activity stage of change Pearson Chi-Square P-value

Stage 1 1.847 0.764

Stage 2 9.123 0.058

Stage 3 26.965 <0.001

Hypothesis testing

Testing significance of offering exercise sessions on mental health wellbeing state

Null hypothesis: offering exercise sessions has no effect on encouraging or maintaining healthy

mental well-being state.

Table 6: Test of hypothesis

WEMWBS score recording

stage

Test of

homogeneity P-

value

P-value Mean

Difference

Confidence

interval

3 months 0.033 0.525 -0.425 -1.741 .891

12 months 0.035 0.002 -1.828 -2.991 -0.666

24 months 0.534 <0.001 -4.971 -6.218 -3.725

Based on the hypothesis test results in the table above, we conclude that offering exercise

sessions have an effect on encouraging or maintaining health mental well-being state (Boylan,

Louie and Gill, 2012). This is because the test at 3 months was not significant but the subsequent

tests after the intervention group was exposed on free exercise sessions, the hypothesis test

turned out to be very significant.

Test of association between physical activity stage and the participants’ group

Null hypothesis: There is no significant association between physical activity stage and offering

exercise sessions

Table 7: Test of association between physical activity stage of change and offering exercise

sessions

Physical Activity stage of change Pearson Chi-Square P-value

Stage 1 1.847 0.764

Stage 2 9.123 0.058

Stage 3 26.965 <0.001

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Measuring Positive Mental Health 11

The first and second stages emerged to be insignificant. However, the last recording stage

results showed a big change with a p-value <0.001. We conclude that there was a significant

association of physical activity stage of change in recording 3 for each group. Based on the

information recorded in the 24th month, we can see that there is a marked difference in each

group (Giangregorio and Cook, 2009).

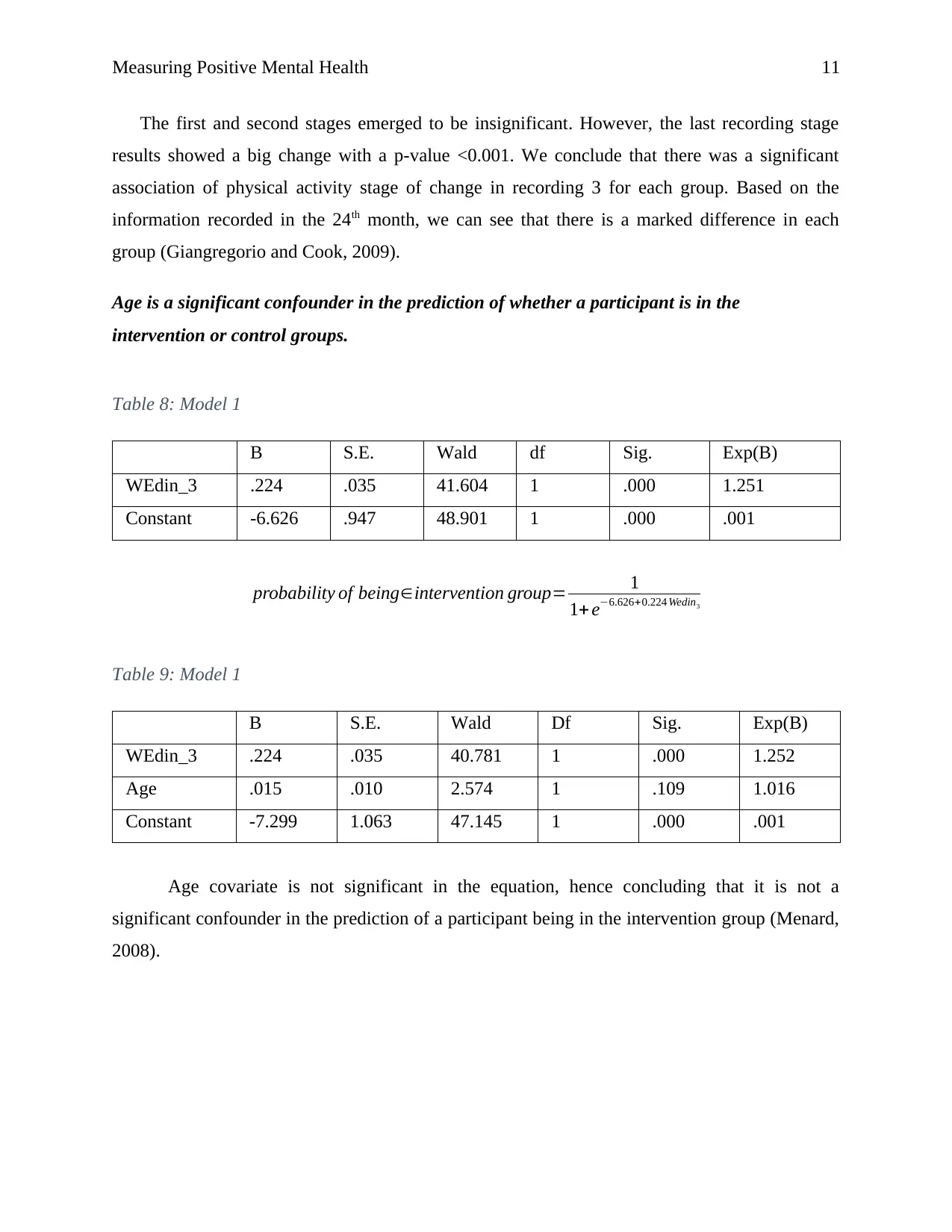

Age is a significant confounder in the prediction of whether a participant is in the

intervention or control groups.

Table 8: Model 1

B S.E. Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

WEdin_3 .224 .035 41.604 1 .000 1.251

Constant -6.626 .947 48.901 1 .000 .001

probability of being∈intervention group= 1

1+ e−6.626+0.224 Wedin3

Table 9: Model 1

B S.E. Wald Df Sig. Exp(B)

WEdin_3 .224 .035 40.781 1 .000 1.252

Age .015 .010 2.574 1 .109 1.016

Constant -7.299 1.063 47.145 1 .000 .001

Age covariate is not significant in the equation, hence concluding that it is not a

significant confounder in the prediction of a participant being in the intervention group (Menard,

2008).

The first and second stages emerged to be insignificant. However, the last recording stage

results showed a big change with a p-value <0.001. We conclude that there was a significant

association of physical activity stage of change in recording 3 for each group. Based on the

information recorded in the 24th month, we can see that there is a marked difference in each

group (Giangregorio and Cook, 2009).

Age is a significant confounder in the prediction of whether a participant is in the

intervention or control groups.

Table 8: Model 1

B S.E. Wald df Sig. Exp(B)

WEdin_3 .224 .035 41.604 1 .000 1.251

Constant -6.626 .947 48.901 1 .000 .001

probability of being∈intervention group= 1

1+ e−6.626+0.224 Wedin3

Table 9: Model 1

B S.E. Wald Df Sig. Exp(B)

WEdin_3 .224 .035 40.781 1 .000 1.252

Age .015 .010 2.574 1 .109 1.016

Constant -7.299 1.063 47.145 1 .000 .001

Age covariate is not significant in the equation, hence concluding that it is not a

significant confounder in the prediction of a participant being in the intervention group (Menard,

2008).

Measuring Positive Mental Health 12

References

Boylan, S., Louie, J. and Gill, T. (2012). Consumer response to healthy eating, physical activity

and weight-related recommendations: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 13(7), pp.606-617.

Choi, B. (2014). The Relationship Between Mental Health and Physical Health. Hanyang

Medical Reviews, 34(2), p.51.

Elder, R., Evans, K. and Nizette, D. (2009). Psychiatric and mental health nursing. Edinburgh:

Mosby.

Giangregorio, L. and Cook, R. (2009). Hypothesis testing in clinical and basic science research.

Transfusion, 50(9), pp.1878-1880.

Menard, S. (2008). Applied logistic regression analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage.

NHS Health Scotland (2017). Mental health and wellbeing. [Online] Healthscotland.scot.

Available at: http://www.healthscotland.scot/health-topics/mental-health-and-wellbeing

[Accessed 14 Nov. 2017].

Pratt, L. (2013). Measuring mental health status for international comparisons: Washington

Group on Disability Statistics. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(8), pp.e33-e34.

Sedgwick, P. (2013). Analyzing case-control studies: adjusting for confounding. BMJ, 346(jan04

1), pp.f25-f25.

References

Boylan, S., Louie, J. and Gill, T. (2012). Consumer response to healthy eating, physical activity

and weight-related recommendations: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 13(7), pp.606-617.

Choi, B. (2014). The Relationship Between Mental Health and Physical Health. Hanyang

Medical Reviews, 34(2), p.51.

Elder, R., Evans, K. and Nizette, D. (2009). Psychiatric and mental health nursing. Edinburgh:

Mosby.

Giangregorio, L. and Cook, R. (2009). Hypothesis testing in clinical and basic science research.

Transfusion, 50(9), pp.1878-1880.

Menard, S. (2008). Applied logistic regression analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif. [u.a.]: Sage.

NHS Health Scotland (2017). Mental health and wellbeing. [Online] Healthscotland.scot.

Available at: http://www.healthscotland.scot/health-topics/mental-health-and-wellbeing

[Accessed 14 Nov. 2017].

Pratt, L. (2013). Measuring mental health status for international comparisons: Washington

Group on Disability Statistics. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(8), pp.e33-e34.

Sedgwick, P. (2013). Analyzing case-control studies: adjusting for confounding. BMJ, 346(jan04

1), pp.f25-f25.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 12

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.