Comprehensive Report: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Overview

VerifiedAdded on 2020/05/04

|20

|5243

|67

Report

AI Summary

This report provides a comprehensive overview of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), a respiratory illness originating in Saudi Arabia. It delves into the epidemiology of MERS, including transmission routes, risk factors, and clinical features, highlighting the role of the MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The report discusses the interaction between the causative agent, host, and environmental factors in the development and spread of the condition, with a focus on the zoonotic transmission from dromedary camels. The report also examines the human-to-human transmission, especially in healthcare settings. It further explores the risk factors, including age, underlying health conditions, and healthcare worker exposure. The report concludes by discussing potential policy responses to control the spread of the virus and mitigate its impact on public health. The report also highlights the global impact of the disease, including outbreaks in countries outside the Middle East. The analysis underscores the importance of understanding MERS to develop effective prevention and control strategies.

Running head: MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME (MERS)

Name

Institution

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME (MERS)

Name

Institution

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)

Introduction

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) is a respiratory syndrome that can be traced

back to Saudi Arabia in 2012. It was initially restricted to persons who were traveling within the

Middle East and/or their contacts, but later had a spill-over effect into other countries as

demonstrated by outbreaks in countries out of the Middle East block such as the Republic of

Korea (RoK), Austria, the Philippines, Thailand, France, Tunisia, Germany, Malaysia, Greece

and the United Kingdom (World Health Organization (WHO), 2017; NSW Government, 2017).

MERS is caused by Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). MERS is

not a national notifiable in Australia, but it is at least classified as a notifiable condition in some

parts of Australia, precisely South and Western Australia (Government of South Australia - SA

Health, n.d.) and the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2015).

This paper is a discussion on MERS with focus on the role of agent, host and

environmental factors in the development and spread of the condition and the corresponding

potential policy responses to the same. This is achieved through discussions on three main

sections. The first section discusses the epidemiology, transmission routes, risk factors and

clinical features, while the second part is a discussion on the interaction between the causative

agent, host and environmental factors in the production of the illness in individuals, and the last

part discusses various responses towards the control of the spread of the virus.

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)

Introduction

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) is a respiratory syndrome that can be traced

back to Saudi Arabia in 2012. It was initially restricted to persons who were traveling within the

Middle East and/or their contacts, but later had a spill-over effect into other countries as

demonstrated by outbreaks in countries out of the Middle East block such as the Republic of

Korea (RoK), Austria, the Philippines, Thailand, France, Tunisia, Germany, Malaysia, Greece

and the United Kingdom (World Health Organization (WHO), 2017; NSW Government, 2017).

MERS is caused by Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). MERS is

not a national notifiable in Australia, but it is at least classified as a notifiable condition in some

parts of Australia, precisely South and Western Australia (Government of South Australia - SA

Health, n.d.) and the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2015).

This paper is a discussion on MERS with focus on the role of agent, host and

environmental factors in the development and spread of the condition and the corresponding

potential policy responses to the same. This is achieved through discussions on three main

sections. The first section discusses the epidemiology, transmission routes, risk factors and

clinical features, while the second part is a discussion on the interaction between the causative

agent, host and environmental factors in the production of the illness in individuals, and the last

part discusses various responses towards the control of the spread of the virus.

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

Discussion

Epidemiology, Transmission Routes, Risk Factors and Clinical Features

Epidemiology

The MERS coronavirus belongs to the large and diverse family of coronaviruses which

are known to cause ill health to both humans and animals. Four strains of coronaviruses that

affect humans {human coronaviruses (hCoV)} are known to cause respiratory infections in

human, with severity ranging from mild to moderate. These hCoVs include the alpha-

coronaviruses hCoV-NL63 and hCoV-229E and betacoronaviruses hCoV-HKU and hCoV-OC43

(The Department of Health, 2014). In the class of beta-coronaviruses also lies the viruses causing

MERS-CoV and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV). However,

according to The Australian Department of Health, these two viruses are genetically distinct

from each other (The Department of Health, 2014). The MERS coronavirus was only identified

in 2012 as a new variant of the coronavirus family that could lead to a rapid onset of severe

respiratory illness in humans (Zaki, van Boheemen, Bestebroer, Osterhaus, & Fouchier, 2012).

Most of MERS cases have been found to develop in persons presenting with other underlying

conditions which predispose them to respiratory infections. While MERS-CoV is distinct from

the SARS-CoV in humans, the MERS-CoV has some similarity to coronaviruses found in bats

(The Department of Health, 2014).

Up to date, all cases of MERS in humans have been in persons who have been residents

in or travellers to the countries in the Middle East or have had a close contact with persons

presenting with the infection in the same region. The disease has been predominantly reported in

in travellers or residents in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Jordan, Qatar and the Kingdom of

Discussion

Epidemiology, Transmission Routes, Risk Factors and Clinical Features

Epidemiology

The MERS coronavirus belongs to the large and diverse family of coronaviruses which

are known to cause ill health to both humans and animals. Four strains of coronaviruses that

affect humans {human coronaviruses (hCoV)} are known to cause respiratory infections in

human, with severity ranging from mild to moderate. These hCoVs include the alpha-

coronaviruses hCoV-NL63 and hCoV-229E and betacoronaviruses hCoV-HKU and hCoV-OC43

(The Department of Health, 2014). In the class of beta-coronaviruses also lies the viruses causing

MERS-CoV and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV). However,

according to The Australian Department of Health, these two viruses are genetically distinct

from each other (The Department of Health, 2014). The MERS coronavirus was only identified

in 2012 as a new variant of the coronavirus family that could lead to a rapid onset of severe

respiratory illness in humans (Zaki, van Boheemen, Bestebroer, Osterhaus, & Fouchier, 2012).

Most of MERS cases have been found to develop in persons presenting with other underlying

conditions which predispose them to respiratory infections. While MERS-CoV is distinct from

the SARS-CoV in humans, the MERS-CoV has some similarity to coronaviruses found in bats

(The Department of Health, 2014).

Up to date, all cases of MERS in humans have been in persons who have been residents

in or travellers to the countries in the Middle East or have had a close contact with persons

presenting with the infection in the same region. The disease has been predominantly reported in

in travellers or residents in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Jordan, Qatar and the Kingdom of

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

Saudi Arabia (Who Mers-Cov Research Group., 2013). But as demonstrated in later years, the

infection is not just restricted to the Middle East as evidenced by the reported cases in countries,

not in the Middle East. This includes countries in Europe such as Italy, Germany, the United

Kingdom, France, Tunisia, Malaysia, South Korea, the Philippines, Thailand and Greece (NSW

Government, 2017). South Korea reported the largest outbreak in 2015, which was a multi-centre

hospital outbreak which was traced to a traveller from the Middle East (WHO, 2015; CDC,

2015). Notably, Australia has so far reported zero MERS-CoV cases. (NSW Government, 2017).

A MERS situation update by WHO for the months of January and February 2017 states that as of

the beginning of March 2017, a total of 1,916 laboratory confirmed cases of MERS have been

reported to WHO and a total of 702 persons have died, translating to a case-fatality rate of 36.6%

(WHO, 2017). According to the same update, a total of 27 countries worldwide have reported

MERS cases.

Transmission routes

The epidemiologic aspects of the MERS-CoV have not been adequately defined, but the

most recognized means of transmission is the human-to-human transmission of the virus, in

healthcare settings. However, just like other coronaviruses, the spread of the virus is thought to

occur through contact with an infected individual’s secretions. The exposure in healthcare

facilities could be justified by the 2015 outbreak in South Korea and Saudi Arabia, whose point

of introduction is always a single introduction of MERS, probably zoonotic (Al-Abdallat, et al.,

2014). According to the WHO, MERS-CoV is a zoonotic virus which enters the sphere of

humans through contact with infected dromedary camels in the Middle East (WHO, 2016). The

restriction that it is dromedary camels in the Arabian Peninsula can be supported by negative

findings of the virus in tested camels from other parts of the world (Chan, et al., 2015).

Saudi Arabia (Who Mers-Cov Research Group., 2013). But as demonstrated in later years, the

infection is not just restricted to the Middle East as evidenced by the reported cases in countries,

not in the Middle East. This includes countries in Europe such as Italy, Germany, the United

Kingdom, France, Tunisia, Malaysia, South Korea, the Philippines, Thailand and Greece (NSW

Government, 2017). South Korea reported the largest outbreak in 2015, which was a multi-centre

hospital outbreak which was traced to a traveller from the Middle East (WHO, 2015; CDC,

2015). Notably, Australia has so far reported zero MERS-CoV cases. (NSW Government, 2017).

A MERS situation update by WHO for the months of January and February 2017 states that as of

the beginning of March 2017, a total of 1,916 laboratory confirmed cases of MERS have been

reported to WHO and a total of 702 persons have died, translating to a case-fatality rate of 36.6%

(WHO, 2017). According to the same update, a total of 27 countries worldwide have reported

MERS cases.

Transmission routes

The epidemiologic aspects of the MERS-CoV have not been adequately defined, but the

most recognized means of transmission is the human-to-human transmission of the virus, in

healthcare settings. However, just like other coronaviruses, the spread of the virus is thought to

occur through contact with an infected individual’s secretions. The exposure in healthcare

facilities could be justified by the 2015 outbreak in South Korea and Saudi Arabia, whose point

of introduction is always a single introduction of MERS, probably zoonotic (Al-Abdallat, et al.,

2014). According to the WHO, MERS-CoV is a zoonotic virus which enters the sphere of

humans through contact with infected dromedary camels in the Middle East (WHO, 2016). The

restriction that it is dromedary camels in the Arabian Peninsula can be supported by negative

findings of the virus in tested camels from other parts of the world (Chan, et al., 2015).

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

Studies have demonstrated strong indicators of both direct and indirect exposure to

camels to causing the infections. This hypothesis is supported by at least one group in which the

camels also tested seropositive (WHO, 2017). Outstandingly, a review of literature also indicates

cases where the infections resulted even in the absence of a history of prior exposure to other

animals. This perspective rather suggests the likelihood of the virus being introduced through

multiple channels as opposed to a single zoonotic case.

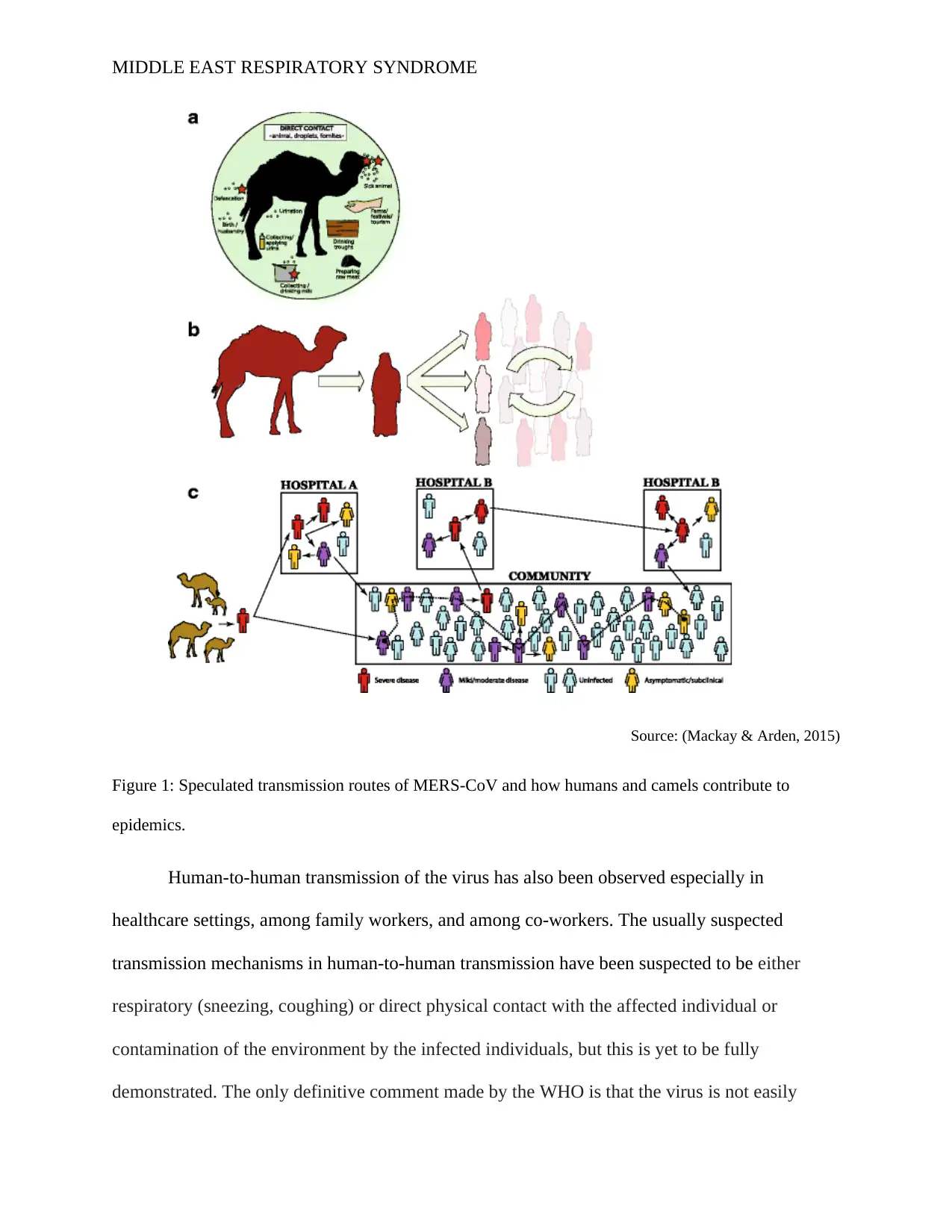

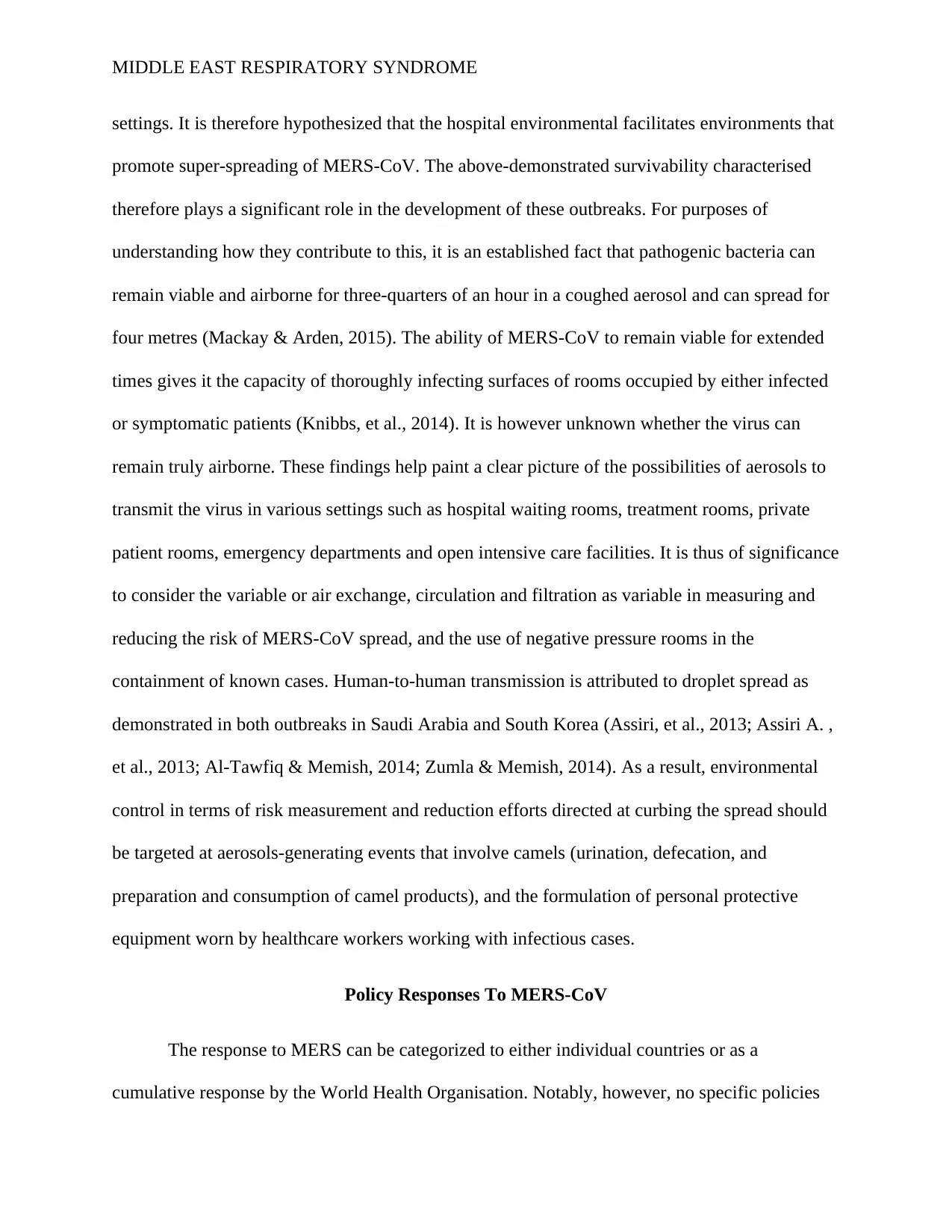

The primary hypothesis in the transmission and resulting outbreaks of MERS has been a

hypothesised link to some animals serving as either the reservoir or intermediate host(s), with

dromedary camels as the primary suspects. They are known to produce a significant amount of

MERS-CoV RNA in their lungs and the urinary tract (Khalafalla, et al., 2015). The droplet

transmission route is claimed to play a significant role in the transmission of the virus. The exact

source from which people acquire the virus from camels has not been clearly defined but it is

postulated that there is an intricate interplay of both animal and human behaviours as

demonstrated in the figure below.

Studies have demonstrated strong indicators of both direct and indirect exposure to

camels to causing the infections. This hypothesis is supported by at least one group in which the

camels also tested seropositive (WHO, 2017). Outstandingly, a review of literature also indicates

cases where the infections resulted even in the absence of a history of prior exposure to other

animals. This perspective rather suggests the likelihood of the virus being introduced through

multiple channels as opposed to a single zoonotic case.

The primary hypothesis in the transmission and resulting outbreaks of MERS has been a

hypothesised link to some animals serving as either the reservoir or intermediate host(s), with

dromedary camels as the primary suspects. They are known to produce a significant amount of

MERS-CoV RNA in their lungs and the urinary tract (Khalafalla, et al., 2015). The droplet

transmission route is claimed to play a significant role in the transmission of the virus. The exact

source from which people acquire the virus from camels has not been clearly defined but it is

postulated that there is an intricate interplay of both animal and human behaviours as

demonstrated in the figure below.

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

Source: (Mackay & Arden, 2015)

Figure 1: Speculated transmission routes of MERS-CoV and how humans and camels contribute to

epidemics.

Human-to-human transmission of the virus has also been observed especially in

healthcare settings, among family workers, and among co-workers. The usually suspected

transmission mechanisms in human-to-human transmission have been suspected to be either

respiratory (sneezing, coughing) or direct physical contact with the affected individual or

contamination of the environment by the infected individuals, but this is yet to be fully

demonstrated. The only definitive comment made by the WHO is that the virus is not easily

Source: (Mackay & Arden, 2015)

Figure 1: Speculated transmission routes of MERS-CoV and how humans and camels contribute to

epidemics.

Human-to-human transmission of the virus has also been observed especially in

healthcare settings, among family workers, and among co-workers. The usually suspected

transmission mechanisms in human-to-human transmission have been suspected to be either

respiratory (sneezing, coughing) or direct physical contact with the affected individual or

contamination of the environment by the infected individuals, but this is yet to be fully

demonstrated. The only definitive comment made by the WHO is that the virus is not easily

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

transmitted from an individual to another unless there is close contact between the two, as

demonstrated in the provision of unprotected care to an infected patient (WHO, 2017). Cases of

human-to-human transmission have only been documented in the health care environment and

nowhere else.

Notably, the origins of MERS-CoV virus are yet to be fully understood, but analysis of

the virus genomes have demonstrated that the virus could have originated in bats and was

transmitted to dromedary camels during early ages.

Risk factors

The distribution of the disease among the already reported cases is demonstrated to be

skewed heavily to middle-aged persons and the elderly. The risk is heightened in persons who

are elderly, are immunocompromised, or present with other comorbidities (WHO, 2017). For

MERS associated with the health care environment, the risk for infection among healthcare

workers is magnified among those who have close contact with patients infected with the virus,

especially radiology technicians and nurses (Alraddadi, et al., 2016). In addition, according to the

same authors, health care workers with a history of smoking had 3 times increased risk for the

infection compared to non-smokers. This association further arouses the curiosity of the role that

smoking plays in the risk profile, unluckily, there is no literature addressing the same. This

requires further research.

Males aged above 60 years are also claimed to be at increased risk of contracting the

virus. The risk is further heightened if they suffer from underlying conditions such as renal

failure, hypertension, and diabetes (WHO, 2017). A twist to this association could rather suggest

that instead of a sex-specific difference in biologic susceptibility, males have exhibit social and

transmitted from an individual to another unless there is close contact between the two, as

demonstrated in the provision of unprotected care to an infected patient (WHO, 2017). Cases of

human-to-human transmission have only been documented in the health care environment and

nowhere else.

Notably, the origins of MERS-CoV virus are yet to be fully understood, but analysis of

the virus genomes have demonstrated that the virus could have originated in bats and was

transmitted to dromedary camels during early ages.

Risk factors

The distribution of the disease among the already reported cases is demonstrated to be

skewed heavily to middle-aged persons and the elderly. The risk is heightened in persons who

are elderly, are immunocompromised, or present with other comorbidities (WHO, 2017). For

MERS associated with the health care environment, the risk for infection among healthcare

workers is magnified among those who have close contact with patients infected with the virus,

especially radiology technicians and nurses (Alraddadi, et al., 2016). In addition, according to the

same authors, health care workers with a history of smoking had 3 times increased risk for the

infection compared to non-smokers. This association further arouses the curiosity of the role that

smoking plays in the risk profile, unluckily, there is no literature addressing the same. This

requires further research.

Males aged above 60 years are also claimed to be at increased risk of contracting the

virus. The risk is further heightened if they suffer from underlying conditions such as renal

failure, hypertension, and diabetes (WHO, 2017). A twist to this association could rather suggest

that instead of a sex-specific difference in biologic susceptibility, males have exhibit social and

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

behavioural factors which increase their exposure to the virus compared to females. This can be

supported by an observation by Mackay and Arden, (2015) in which males infected by MERS-

CoV present with a more severe disease compared to females of the same class.

Clinical picture

The mean incubation period for MERS-CoV has been determined to be 5 to 6 days, ranging from

2 to 16 days, with 13-14 days between when one person develops the diseases and spreads it to

another (Assiri, et al., 2013; Memish, Zumla, Al-Hakeem, Al-Rabeeah, & Stephens, 2013). For

cases with progressive illness, the median death is 11-13 days (Assiri, et al., 2013; Ki, 2015).

Early symptoms of the illness include fever, myalgia, chills and gastrointestinal symptoms,

which subsequently decline, only be substituted with more severe systemic and respiratory

syndrome, severe pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome and multi-organ failure

(Kraaij-Dirkzwager, et al., 2014; Mailles, et al., 2013).

The Interaction Between The MERS-CoV, Host and Environmental Factors to Produce

MERS

Majority of camels in the Arabian Peninsula are dromedary camels and their contact with

humans ranges between little to close. This contact serves as the gateway to the transmission and

the corresponding outbreaks; hence it is significant to illustrate the interplay of the agent, the

reservoir and the environmental factors that predispose the host to the virus and consequential

development of the syndrome.

The human-camel contact is commonplace in the Arabian Peninsula and may result from

various ways (as illustrated in the figure above). Most of the countries in the Middle East (with

behavioural factors which increase their exposure to the virus compared to females. This can be

supported by an observation by Mackay and Arden, (2015) in which males infected by MERS-

CoV present with a more severe disease compared to females of the same class.

Clinical picture

The mean incubation period for MERS-CoV has been determined to be 5 to 6 days, ranging from

2 to 16 days, with 13-14 days between when one person develops the diseases and spreads it to

another (Assiri, et al., 2013; Memish, Zumla, Al-Hakeem, Al-Rabeeah, & Stephens, 2013). For

cases with progressive illness, the median death is 11-13 days (Assiri, et al., 2013; Ki, 2015).

Early symptoms of the illness include fever, myalgia, chills and gastrointestinal symptoms,

which subsequently decline, only be substituted with more severe systemic and respiratory

syndrome, severe pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome and multi-organ failure

(Kraaij-Dirkzwager, et al., 2014; Mailles, et al., 2013).

The Interaction Between The MERS-CoV, Host and Environmental Factors to Produce

MERS

Majority of camels in the Arabian Peninsula are dromedary camels and their contact with

humans ranges between little to close. This contact serves as the gateway to the transmission and

the corresponding outbreaks; hence it is significant to illustrate the interplay of the agent, the

reservoir and the environmental factors that predispose the host to the virus and consequential

development of the syndrome.

The human-camel contact is commonplace in the Arabian Peninsula and may result from

various ways (as illustrated in the figure above). Most of the countries in the Middle East (with

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

special reference to Saudi Arabia due the fact that it has so far recorded the highest number of

cases), has several large well-attended festivals, parades, sales and races which feature

dromedary camels and also, these camels are bred and reared close to populated areas (Al-

Mukhtar & Estimo, 2014; Hemida, et al., 2015)127-128. In addition, inhabitants of these

countries have the tendency to consume milk and meat from camels after the Hajj pilgrimage

(Mackay & Arden, 2015). Notably, however, reports of infections of MERS-CoV are much

lower compared to the frequent habits of preparing, drinking, eating products from dromedary

camels. It is also established that some tribes in Saudi Arabia consume fresh unpasteurised milk

from dromedary camels, alongside their urine which is claimed to be having some health

benefits. It is however interesting to note that butchers make up a larger proportion of the local

occupations, and neither them nor any of the associated risk groups have ever been identified

among MERS cases (Mackay & Arden, 2015). A logical explanation to explain the same is that

there is a heightened likelihood to be a reporting issue and not just an unexplainable absence of

the illness. This association can be corroborated by evidence from a 2015 case-control study that

concluded that the onset of MERS is as a result of direct contact with dromedary camels and not

the ingestion of products from these animals (Alraddadi, et al., 2014). Some researchers hold a

different hypothesis that there is the likelihood of humans infecting dromedary camels, contrary

to the already established hypothesis. This divergent proposition has been instigated by

laboratory finding in which whenever cases of MERS have been reported, the camel population

is also found to have nasal colonisation of the virus alike. This hypothesis is however yet to be

studied and proven.

Camels often calve during the winter months that run between late October and late

February and this season may be characterised by an increased risk of spill-over of the virus to

special reference to Saudi Arabia due the fact that it has so far recorded the highest number of

cases), has several large well-attended festivals, parades, sales and races which feature

dromedary camels and also, these camels are bred and reared close to populated areas (Al-

Mukhtar & Estimo, 2014; Hemida, et al., 2015)127-128. In addition, inhabitants of these

countries have the tendency to consume milk and meat from camels after the Hajj pilgrimage

(Mackay & Arden, 2015). Notably, however, reports of infections of MERS-CoV are much

lower compared to the frequent habits of preparing, drinking, eating products from dromedary

camels. It is also established that some tribes in Saudi Arabia consume fresh unpasteurised milk

from dromedary camels, alongside their urine which is claimed to be having some health

benefits. It is however interesting to note that butchers make up a larger proportion of the local

occupations, and neither them nor any of the associated risk groups have ever been identified

among MERS cases (Mackay & Arden, 2015). A logical explanation to explain the same is that

there is a heightened likelihood to be a reporting issue and not just an unexplainable absence of

the illness. This association can be corroborated by evidence from a 2015 case-control study that

concluded that the onset of MERS is as a result of direct contact with dromedary camels and not

the ingestion of products from these animals (Alraddadi, et al., 2014). Some researchers hold a

different hypothesis that there is the likelihood of humans infecting dromedary camels, contrary

to the already established hypothesis. This divergent proposition has been instigated by

laboratory finding in which whenever cases of MERS have been reported, the camel population

is also found to have nasal colonisation of the virus alike. This hypothesis is however yet to be

studied and proven.

Camels often calve during the winter months that run between late October and late

February and this season may be characterised by an increased risk of spill-over of the virus to

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

humans because new infections are often likely to occur within the camel populations (Hemida,

et al., 2015). The role played by maternal camel antibody in delaying infection in the calves is

yet to be established (Memish, et al., 2013; Hemida, et al., 2015). Young camels have been

found to host active infection more often compared to their parents, and as a result of the

inclination to choose camels aged 5 years or older for sacrificial slaughter, and this is

accompanied with an insignificant risk of exposure to the virus. This conclusion draws reference

back to the fact that slaughterhouse workers stand out as a high-risk occupational group.

The survivability of MERS-CoV in the environment is also important towards

understanding the association between the various parameters leading to the development of the

illness. Laboratory experiments have demonstrated that adding the virus to milk from either a

camel, goat or cow, and storing it at low temperatures (4 degrees Celsius), the virus could still be

recovered at least seventy-two hours later, and if stored at 22 degrees Celsius (almost room

temperature), the virus could still survive up to 48 hours (van Doremalen, Bushmaker, &

Munster, 2013).

On the survivability of the virus in the environment in the absence of a milk medium, a

study by van Doremalen, Bushmaker, and Munster, (2013) was able to demonstrate that even at

high ambient temperatures (about 30 degrees Celsius) and low relative humidity (30%), the virus

still remains viable for up to 24 hours. This demonstrates quite a significant survivability rate

compared to other well-known and efficiently transmitted respiratory virus such as influenza A

virus which cannot be recovered even after four hours under the same conditions to those

survived by MERS-CoV (van Doremalen, Bushmaker, & Munster, 2013). However, the survival

of MERS-CoV is still said to be inferior compared to that of SARS-CoV (Chan, et al., 2011).

MERS outbreaks have been so far experienced in health care settings as opposed to community

humans because new infections are often likely to occur within the camel populations (Hemida,

et al., 2015). The role played by maternal camel antibody in delaying infection in the calves is

yet to be established (Memish, et al., 2013; Hemida, et al., 2015). Young camels have been

found to host active infection more often compared to their parents, and as a result of the

inclination to choose camels aged 5 years or older for sacrificial slaughter, and this is

accompanied with an insignificant risk of exposure to the virus. This conclusion draws reference

back to the fact that slaughterhouse workers stand out as a high-risk occupational group.

The survivability of MERS-CoV in the environment is also important towards

understanding the association between the various parameters leading to the development of the

illness. Laboratory experiments have demonstrated that adding the virus to milk from either a

camel, goat or cow, and storing it at low temperatures (4 degrees Celsius), the virus could still be

recovered at least seventy-two hours later, and if stored at 22 degrees Celsius (almost room

temperature), the virus could still survive up to 48 hours (van Doremalen, Bushmaker, &

Munster, 2013).

On the survivability of the virus in the environment in the absence of a milk medium, a

study by van Doremalen, Bushmaker, and Munster, (2013) was able to demonstrate that even at

high ambient temperatures (about 30 degrees Celsius) and low relative humidity (30%), the virus

still remains viable for up to 24 hours. This demonstrates quite a significant survivability rate

compared to other well-known and efficiently transmitted respiratory virus such as influenza A

virus which cannot be recovered even after four hours under the same conditions to those

survived by MERS-CoV (van Doremalen, Bushmaker, & Munster, 2013). However, the survival

of MERS-CoV is still said to be inferior compared to that of SARS-CoV (Chan, et al., 2011).

MERS outbreaks have been so far experienced in health care settings as opposed to community

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

settings. It is therefore hypothesized that the hospital environmental facilitates environments that

promote super-spreading of MERS-CoV. The above-demonstrated survivability characterised

therefore plays a significant role in the development of these outbreaks. For purposes of

understanding how they contribute to this, it is an established fact that pathogenic bacteria can

remain viable and airborne for three-quarters of an hour in a coughed aerosol and can spread for

four metres (Mackay & Arden, 2015). The ability of MERS-CoV to remain viable for extended

times gives it the capacity of thoroughly infecting surfaces of rooms occupied by either infected

or symptomatic patients (Knibbs, et al., 2014). It is however unknown whether the virus can

remain truly airborne. These findings help paint a clear picture of the possibilities of aerosols to

transmit the virus in various settings such as hospital waiting rooms, treatment rooms, private

patient rooms, emergency departments and open intensive care facilities. It is thus of significance

to consider the variable or air exchange, circulation and filtration as variable in measuring and

reducing the risk of MERS-CoV spread, and the use of negative pressure rooms in the

containment of known cases. Human-to-human transmission is attributed to droplet spread as

demonstrated in both outbreaks in Saudi Arabia and South Korea (Assiri, et al., 2013; Assiri A. ,

et al., 2013; Al-Tawfiq & Memish, 2014; Zumla & Memish, 2014). As a result, environmental

control in terms of risk measurement and reduction efforts directed at curbing the spread should

be targeted at aerosols-generating events that involve camels (urination, defecation, and

preparation and consumption of camel products), and the formulation of personal protective

equipment worn by healthcare workers working with infectious cases.

Policy Responses To MERS-CoV

The response to MERS can be categorized to either individual countries or as a

cumulative response by the World Health Organisation. Notably, however, no specific policies

settings. It is therefore hypothesized that the hospital environmental facilitates environments that

promote super-spreading of MERS-CoV. The above-demonstrated survivability characterised

therefore plays a significant role in the development of these outbreaks. For purposes of

understanding how they contribute to this, it is an established fact that pathogenic bacteria can

remain viable and airborne for three-quarters of an hour in a coughed aerosol and can spread for

four metres (Mackay & Arden, 2015). The ability of MERS-CoV to remain viable for extended

times gives it the capacity of thoroughly infecting surfaces of rooms occupied by either infected

or symptomatic patients (Knibbs, et al., 2014). It is however unknown whether the virus can

remain truly airborne. These findings help paint a clear picture of the possibilities of aerosols to

transmit the virus in various settings such as hospital waiting rooms, treatment rooms, private

patient rooms, emergency departments and open intensive care facilities. It is thus of significance

to consider the variable or air exchange, circulation and filtration as variable in measuring and

reducing the risk of MERS-CoV spread, and the use of negative pressure rooms in the

containment of known cases. Human-to-human transmission is attributed to droplet spread as

demonstrated in both outbreaks in Saudi Arabia and South Korea (Assiri, et al., 2013; Assiri A. ,

et al., 2013; Al-Tawfiq & Memish, 2014; Zumla & Memish, 2014). As a result, environmental

control in terms of risk measurement and reduction efforts directed at curbing the spread should

be targeted at aerosols-generating events that involve camels (urination, defecation, and

preparation and consumption of camel products), and the formulation of personal protective

equipment worn by healthcare workers working with infectious cases.

Policy Responses To MERS-CoV

The response to MERS can be categorized to either individual countries or as a

cumulative response by the World Health Organisation. Notably, however, no specific policies

MIDDLE EAST RESPIRATORY SYNDROME

have been designed to control the virus, but rather various guidelines are available for the control

of the same. For instance, the Saudi Arabian Ministry of health has responded with both

outbreak control policies touching on notification of suspected cases, risk assessment,

investigation procedures and treatment protocols. WHO has likewise taken various steps and also

projected steps to be undertaken later on.

WHO works with various countries, and has notably worked with CDC to develop

policies aimed at improving the efficiency of surveillance (Banerjee, Rawat, & Subudhi, 2015),

and the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health (MoH) to develop specific guideline for the control

and prevention of infections by the virus for both health care workers, patients and their family

members contained under the Scientific Advisory Board’s Infection Prevention and Control

Guidelines for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Infection (Saudi

Arabia Ministry of Health, 2014; Scientific Advisory Board, 2015). Neither CDC nor Saudi

Arabia MoH has prescribed specific guidelines for the control of the agent, but have rather made

recommendations for quarantine measures for infected individuals and have also prescribed

guidelines to be followed before the infected person resumes regular activities following

recovery. Both the CDC, Saudi Arabian MoH and various agencies from most countries

(Australia included) have also prescribed guidelines for airport staff on the management of

suspected MERS cases, and likewise developed advisories and precautionary statements for

travellers into and out of the countries.

The WHO Director-General convened the International Health Regulations (IHR)

Emergency Committee on MERS which is chaired by Australia’s Chief Medical Officer (The

Department of Health, 2016). In the case of Australia, the country’s Communicable Diseases

Network Australia has also developed a national guideline for the public health management of

have been designed to control the virus, but rather various guidelines are available for the control

of the same. For instance, the Saudi Arabian Ministry of health has responded with both

outbreak control policies touching on notification of suspected cases, risk assessment,

investigation procedures and treatment protocols. WHO has likewise taken various steps and also

projected steps to be undertaken later on.

WHO works with various countries, and has notably worked with CDC to develop

policies aimed at improving the efficiency of surveillance (Banerjee, Rawat, & Subudhi, 2015),

and the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health (MoH) to develop specific guideline for the control

and prevention of infections by the virus for both health care workers, patients and their family

members contained under the Scientific Advisory Board’s Infection Prevention and Control

Guidelines for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Infection (Saudi

Arabia Ministry of Health, 2014; Scientific Advisory Board, 2015). Neither CDC nor Saudi

Arabia MoH has prescribed specific guidelines for the control of the agent, but have rather made

recommendations for quarantine measures for infected individuals and have also prescribed

guidelines to be followed before the infected person resumes regular activities following

recovery. Both the CDC, Saudi Arabian MoH and various agencies from most countries

(Australia included) have also prescribed guidelines for airport staff on the management of

suspected MERS cases, and likewise developed advisories and precautionary statements for

travellers into and out of the countries.

The WHO Director-General convened the International Health Regulations (IHR)

Emergency Committee on MERS which is chaired by Australia’s Chief Medical Officer (The

Department of Health, 2016). In the case of Australia, the country’s Communicable Diseases

Network Australia has also developed a national guideline for the public health management of

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

1 out of 20

Related Documents

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.