Model-Driven Engineering of MES for Food and Beverage Industry

VerifiedAdded on 2022/03/22

|21

|11672

|16

Report

AI Summary

This research paper, authored by Xinyu Chen, Christoph Nophut, and Tobias Voigt, introduces a model-driven engineering (MDE) approach for Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES) specifically tailored for the food and beverage industry. The study addresses the challenges of MES implementation in this sector, such as complex integration and customization, by proposing a MDE-based solution to automate MES generation. The approach encompasses the entire engineering process, from specification to MES generation and validation. The authors validate the feasibility and practicality of their method through a case study involving a brewing process, demonstrating its potential to enhance manufacturing efficiency and transparency. The paper also reviews existing literature on MES, MDE, and their application within the food and beverage industry, highlighting the need for a concrete model-driven approach. The research emphasizes the benefits of MDE in simplifying MES implementation, promoting reusability, and reducing complexity in the context of Industry 4.0 principles. This research provides valuable insights into how the food and beverage industry can leverage MDE to improve their production processes.

electronics

Article

Manufacturing Execution Systems for the Food and

Beverage Industry:A Model-Driven Approach

Xinyu Chen *, Christoph Nophut and Tobias Voigt

Chair of Food Packaging Technology, TUM School of Life Sciences, Technical University of Munich,

85354 Freising, Germany; christoph.nophut@tum.de (C.N.); tobias.voigt@tum.de (T.V.)

* Correspondence:xinyu.chen@tum.de

Received:8 November 2020; Accepted:28 November 2020; Published:2 December 2020

Abstract:Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES) are process-oriented information-technology

(IT) solutions for collecting and managing information from manufacturing processes.Due to the

individual programming effort and the complex integration with other manufacturing systems,

though the food and beverage manufacturers can benefit from the MES, its implementation is not

widespread in this industry.To simplify the implementation and engineering process, the concept

of model-driven engineering (MDE) is considered as a solution.However, a feasible model-driven

approach for MES engineering has not been established, not to mention for the food and beverage

industry.This paper presents an approach for the automatic MES generation according to the MDE

concept providing MES functions that are relevant to the food and beverage manufacturing processes

primarily.It consists of necessary phases to cover the whole engineering process of the MES. Based on

the application of the presented approach to the brewing process in a brewhouse, the feasibility and

practicality of this approach were proven.

Keywords:manufacturing execution systems; model-driven engineering; food and beverage industry

1.Introduction

Information-technology (IT) systems have been used to improve production processes and

are indispensable for manufacturing firms seeking to remain competitive in the global market [1].

To utilize the potential for improvement, manufacturing processes on the shop floor should not be

ignored.With the increasing flexibility of processes and the diversification of products, the traditional

operational IT systems (e.g., Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)), are not able to react in real-time

to meet the requirements of improvements on the shop floor.Manufacturing Execution Systems

(MES) are process-oriented software systems that manage and analyze real-time information in the

manufacturing processes.On one hand,MES implement production plans from systems on the

enterprise-level in operative details to the production area.On the other hand, they provide essential

key performance indicators, including specific energy consumption and machine e fficiency metrics,

to the enterprise for making business decisions and for the improvement of the manufacturing

performance.The implementation of MES raises the transparency of manufacturing processes so

that product quality and workflow efficiency can be optimized.Although the sectors in the food and

beverage industry can benefit from MES, the special characteristics of the manufacturing processes

and the lack of human, material, and financial resources have hindered their investment into MES

implementation,in which considered efforts for programming,customizing,and integrating are

indispensable to deal with the high complexity of MES, owing to the wide range of functions required

to control the shop floor processes and the communications with intra- and extra-systems [ 2,3].

Using code-centric technologies to develop such a complex system requires a herculean effort [4].

An essential factor behind the development is the wide conceptual gap between the implementation

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040; doi:10.3390/electronics9122040 www.mdpi.com/journal/electronics

Article

Manufacturing Execution Systems for the Food and

Beverage Industry:A Model-Driven Approach

Xinyu Chen *, Christoph Nophut and Tobias Voigt

Chair of Food Packaging Technology, TUM School of Life Sciences, Technical University of Munich,

85354 Freising, Germany; christoph.nophut@tum.de (C.N.); tobias.voigt@tum.de (T.V.)

* Correspondence:xinyu.chen@tum.de

Received:8 November 2020; Accepted:28 November 2020; Published:2 December 2020

Abstract:Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES) are process-oriented information-technology

(IT) solutions for collecting and managing information from manufacturing processes.Due to the

individual programming effort and the complex integration with other manufacturing systems,

though the food and beverage manufacturers can benefit from the MES, its implementation is not

widespread in this industry.To simplify the implementation and engineering process, the concept

of model-driven engineering (MDE) is considered as a solution.However, a feasible model-driven

approach for MES engineering has not been established, not to mention for the food and beverage

industry.This paper presents an approach for the automatic MES generation according to the MDE

concept providing MES functions that are relevant to the food and beverage manufacturing processes

primarily.It consists of necessary phases to cover the whole engineering process of the MES. Based on

the application of the presented approach to the brewing process in a brewhouse, the feasibility and

practicality of this approach were proven.

Keywords:manufacturing execution systems; model-driven engineering; food and beverage industry

1.Introduction

Information-technology (IT) systems have been used to improve production processes and

are indispensable for manufacturing firms seeking to remain competitive in the global market [1].

To utilize the potential for improvement, manufacturing processes on the shop floor should not be

ignored.With the increasing flexibility of processes and the diversification of products, the traditional

operational IT systems (e.g., Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)), are not able to react in real-time

to meet the requirements of improvements on the shop floor.Manufacturing Execution Systems

(MES) are process-oriented software systems that manage and analyze real-time information in the

manufacturing processes.On one hand,MES implement production plans from systems on the

enterprise-level in operative details to the production area.On the other hand, they provide essential

key performance indicators, including specific energy consumption and machine e fficiency metrics,

to the enterprise for making business decisions and for the improvement of the manufacturing

performance.The implementation of MES raises the transparency of manufacturing processes so

that product quality and workflow efficiency can be optimized.Although the sectors in the food and

beverage industry can benefit from MES, the special characteristics of the manufacturing processes

and the lack of human, material, and financial resources have hindered their investment into MES

implementation,in which considered efforts for programming,customizing,and integrating are

indispensable to deal with the high complexity of MES, owing to the wide range of functions required

to control the shop floor processes and the communications with intra- and extra-systems [ 2,3].

Using code-centric technologies to develop such a complex system requires a herculean effort [4].

An essential factor behind the development is the wide conceptual gap between the implementation

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040; doi:10.3390/electronics9122040 www.mdpi.com/journal/electronics

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040 2 of 21

domains.The concept of model-driven engineering (MDE) is concerned primarily with reducing this

gap through the use of abstractions to software implementations [5,6]. For the software development

using MDE concept, the primary artifacts of development are models, the transformation from models

into running systems is relied on computer-based technologies.By raising the level of abstraction

and automating labor-intensive and error-prone tasks, MDE has been seen as a solution to handle the

complexity of software development [7]. However, though many researchers have focused on the

industrial application of the MDE, such as for embedded software [8], mobile applications [9], and the

automated production systems [10], a concrete approach that covers the whole lifecycle of the MES

engineering has not been established yet.

This paper presents the first model-driven approach for the automatic generation of the MES and

emphasizes specification as well as MES generation with validation to fulfill the requirements from the

food and beverage industry.The feasibility of this approach is proven by its application to a brewing

process for thermal energy management.The paper is structured as follows.Section 2 introduces the

definition and functionality of the MES and gives a literature review to analyze the requirements and

barriers from the food and beverage industry for MES implementation.Previous works related to MDE

have also been presented in this section.Section 3 presents the requirements that should be fulfilled

by a model-driven approach for MES engineering based on the literature review.Section 4 describes

the developed model-driven approach in detail.Section 5 provides a use case on the application of

this approach to a brewhouse and evaluates it according to the requirements presented in Section 3

Section 6 draws conclusions and outlines future work.

2.State of the Art

2.1.Definition and Functionality of the MES

For the manufacturing industry, to fulfill the requirement from the shop floor on the data collection

and operation reaction in real-time, the idea of MES was firstly introduced by AMR Research in 1992,

and also in this year, MESA (Manufacturing Enterprise Solutions Association) was established [11,12].

According to MESA, the core task of the MES is considered as an information center that enables

the manufacturers to optimize production activities [13]. For different manufacturing environments,

twelve MES functionalities were defined [14]: resource allocation and control, dispatching production,

data collection and acquisition,quality management,process management,production tracking,

performance analysis,operations and detailed scheduling,document control,labor management,

maintenance management, and transport, storage, and tracking of materials.

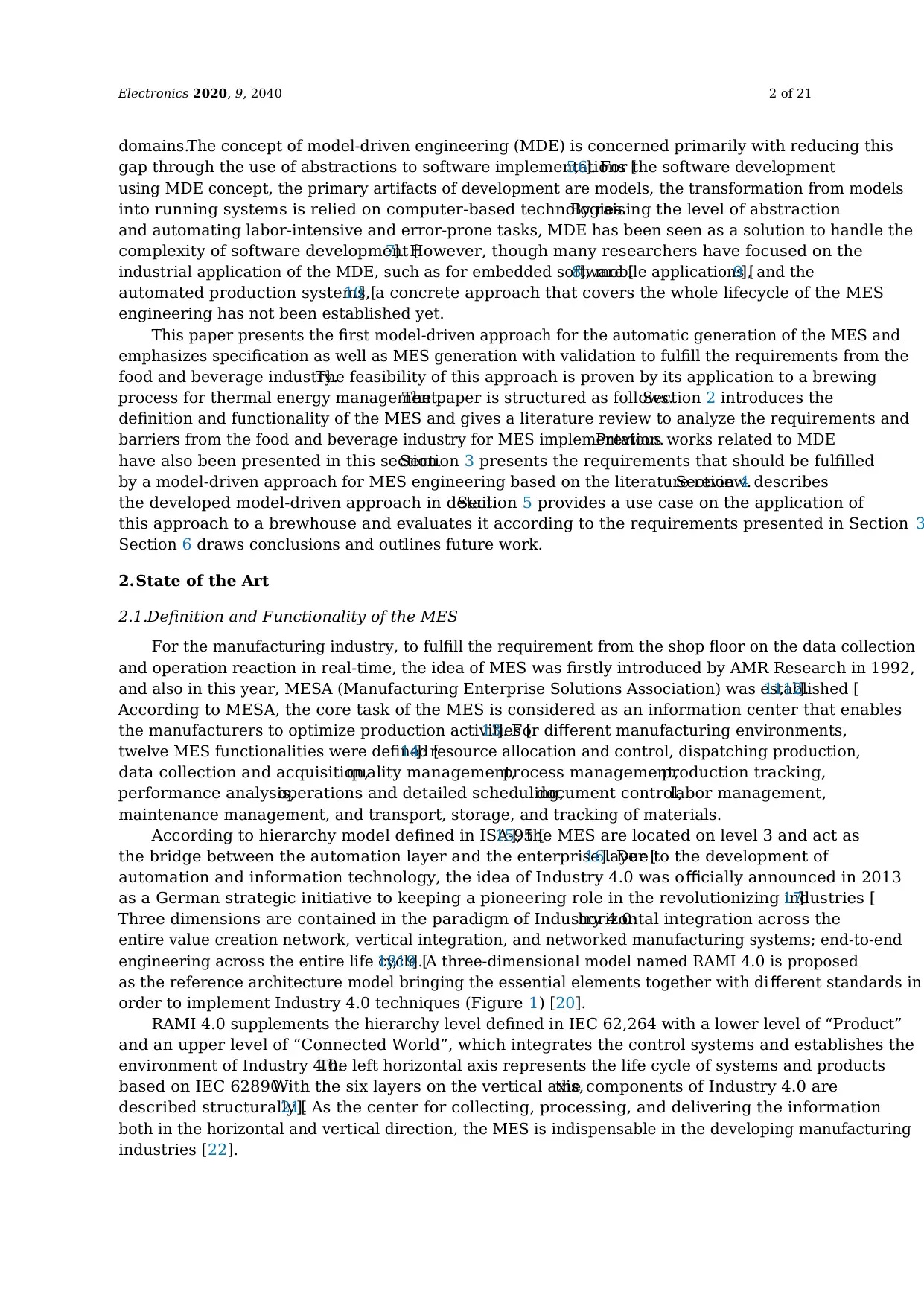

According to hierarchy model defined in ISA-95 [15], the MES are located on level 3 and act as

the bridge between the automation layer and the enterprise layer [16]. Due to the development of

automation and information technology, the idea of Industry 4.0 was officially announced in 2013

as a German strategic initiative to keeping a pioneering role in the revolutionizing industries [17].

Three dimensions are contained in the paradigm of Industry 4.0:horizontal integration across the

entire value creation network, vertical integration, and networked manufacturing systems; end-to-end

engineering across the entire life cycle [18,19]. A three-dimensional model named RAMI 4.0 is proposed

as the reference architecture model bringing the essential elements together with di fferent standards in

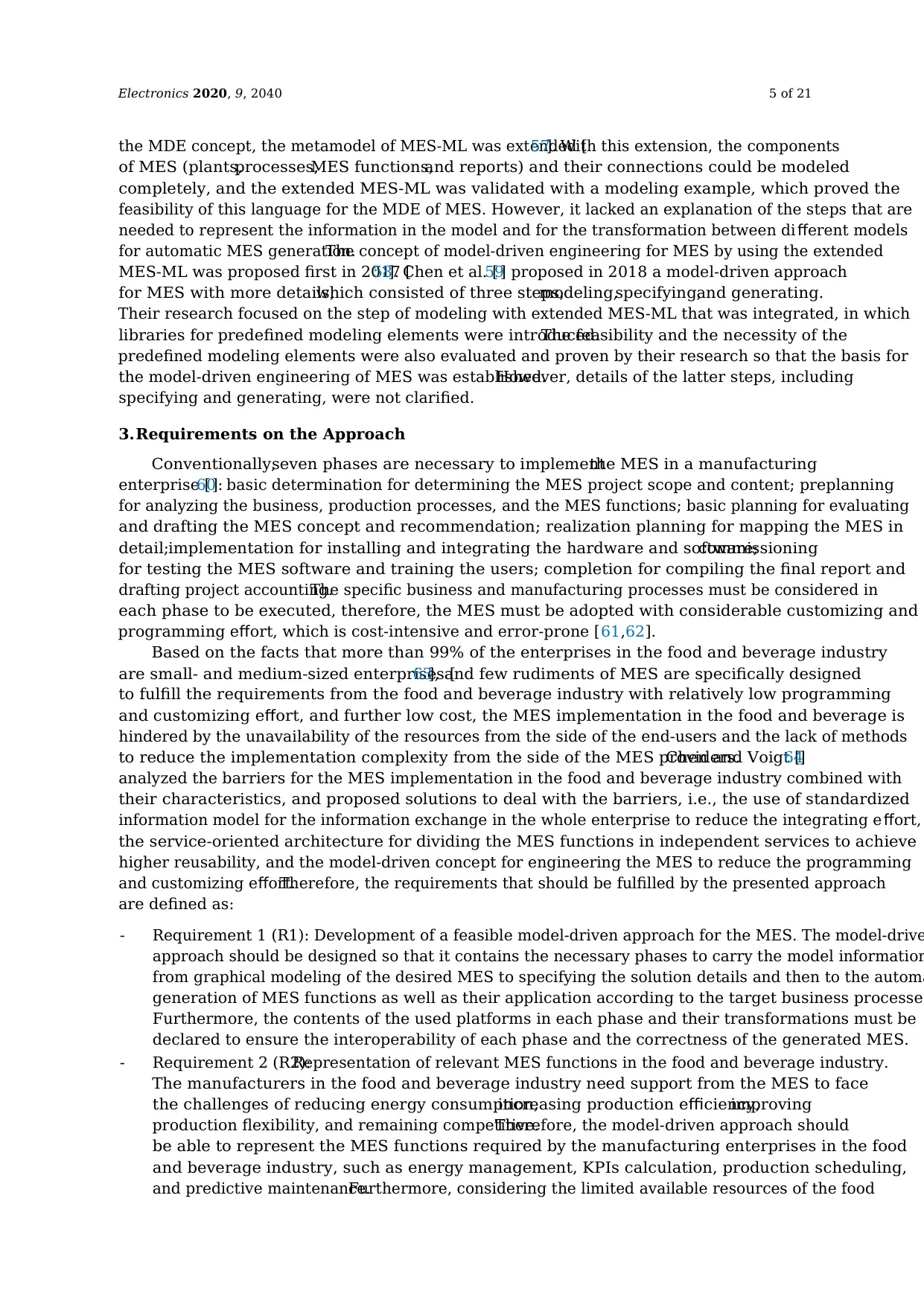

order to implement Industry 4.0 techniques (Figure 1) [20].

RAMI 4.0 supplements the hierarchy level defined in IEC 62,264 with a lower level of “Product”

and an upper level of “Connected World”, which integrates the control systems and establishes the

environment of Industry 4.0.The left horizontal axis represents the life cycle of systems and products

based on IEC 62890.With the six layers on the vertical axis,the components of Industry 4.0 are

described structurally [21]. As the center for collecting, processing, and delivering the information

both in the horizontal and vertical direction, the MES is indispensable in the developing manufacturing

industries [22].

domains.The concept of model-driven engineering (MDE) is concerned primarily with reducing this

gap through the use of abstractions to software implementations [5,6]. For the software development

using MDE concept, the primary artifacts of development are models, the transformation from models

into running systems is relied on computer-based technologies.By raising the level of abstraction

and automating labor-intensive and error-prone tasks, MDE has been seen as a solution to handle the

complexity of software development [7]. However, though many researchers have focused on the

industrial application of the MDE, such as for embedded software [8], mobile applications [9], and the

automated production systems [10], a concrete approach that covers the whole lifecycle of the MES

engineering has not been established yet.

This paper presents the first model-driven approach for the automatic generation of the MES and

emphasizes specification as well as MES generation with validation to fulfill the requirements from the

food and beverage industry.The feasibility of this approach is proven by its application to a brewing

process for thermal energy management.The paper is structured as follows.Section 2 introduces the

definition and functionality of the MES and gives a literature review to analyze the requirements and

barriers from the food and beverage industry for MES implementation.Previous works related to MDE

have also been presented in this section.Section 3 presents the requirements that should be fulfilled

by a model-driven approach for MES engineering based on the literature review.Section 4 describes

the developed model-driven approach in detail.Section 5 provides a use case on the application of

this approach to a brewhouse and evaluates it according to the requirements presented in Section 3

Section 6 draws conclusions and outlines future work.

2.State of the Art

2.1.Definition and Functionality of the MES

For the manufacturing industry, to fulfill the requirement from the shop floor on the data collection

and operation reaction in real-time, the idea of MES was firstly introduced by AMR Research in 1992,

and also in this year, MESA (Manufacturing Enterprise Solutions Association) was established [11,12].

According to MESA, the core task of the MES is considered as an information center that enables

the manufacturers to optimize production activities [13]. For different manufacturing environments,

twelve MES functionalities were defined [14]: resource allocation and control, dispatching production,

data collection and acquisition,quality management,process management,production tracking,

performance analysis,operations and detailed scheduling,document control,labor management,

maintenance management, and transport, storage, and tracking of materials.

According to hierarchy model defined in ISA-95 [15], the MES are located on level 3 and act as

the bridge between the automation layer and the enterprise layer [16]. Due to the development of

automation and information technology, the idea of Industry 4.0 was officially announced in 2013

as a German strategic initiative to keeping a pioneering role in the revolutionizing industries [17].

Three dimensions are contained in the paradigm of Industry 4.0:horizontal integration across the

entire value creation network, vertical integration, and networked manufacturing systems; end-to-end

engineering across the entire life cycle [18,19]. A three-dimensional model named RAMI 4.0 is proposed

as the reference architecture model bringing the essential elements together with di fferent standards in

order to implement Industry 4.0 techniques (Figure 1) [20].

RAMI 4.0 supplements the hierarchy level defined in IEC 62,264 with a lower level of “Product”

and an upper level of “Connected World”, which integrates the control systems and establishes the

environment of Industry 4.0.The left horizontal axis represents the life cycle of systems and products

based on IEC 62890.With the six layers on the vertical axis,the components of Industry 4.0 are

described structurally [21]. As the center for collecting, processing, and delivering the information

both in the horizontal and vertical direction, the MES is indispensable in the developing manufacturing

industries [22].

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040 3 of 21

Electronics 2020, 11, x FOR PEER REVIEW 3 of 21

Figure 1. Reference Architectural Model Industry 4.0 (RAMI 4.0) [21].

2.2. The Food and Beverage Industry

Three different types of the production process can be found in the food and beverage industry

[23]: batch process for the production of finite quantities of material by subjecting quantities of input

materials; continuous process for the continuous material flow through processing equipment;

discrete process for the production of units moving between processing stations. The differences of

the food and beverage industry from the other manufacturing industries can be summarized as [24–

26]: (i) the splitting and mixing lots lead to a combination of divergent processes with convergent

processes in the production; (ii) production yields are uncertain as the property of materials i

changing over time; (iii) products or semi-finished products are recycled during the production

process; (iv) final products have a limited shelf-life and deteriorate over time.

To ensure the quality and safety of the final products, the transparency through the production

must be enhanced to achieve efficient process management, which can be supported by the MES, as

the MES is connected to the shop floor and serves as the center delivering critical process information

to the co-systems [27]. Though researchers have analyzed the factors that can influence the choice of

consumers for food and beverage [28], the price remains the most critical factor [29]. Due to the low-

profit margins, sectors in the food and beverage industry, for reasonable pricing of the final products,

have paid more attention to reduce the energy consumption and enhance the production efficiency

[30]. By understanding the consumption of energy resources globally, the MES can contribute

managing and reducing energy consumption in the manufacturing processes [31]. MES can als

support the application of lean principles, as it provides real-time information to fees and/or validate

the lean processes to improve the efficiency of the production [32]. To satisfy the diverse demands of

the consumers, the variety of food and beverage products is growing in the market [33]. By t

continuousintroductionof new products, the traditionalones can lose their viability in an

unpredictable way [34]. The manufacturers have to shift their production strategy from make-to-

stock to make-to-order to improve production flexibility, scheduling timeliness, and further to react

to the product dynamics. The MES is considered as the basis for scheduling in the process industry,

as the information form the whole enterprise, such as the order delivery time, the use of processing

materials, and the machine availability, must be coupled to generate the production plans [35,36]. In

the new industrial automation environment, owing to its essential role as information center for data

Figure 1.Reference Architectural Model Industry 4.0 (RAMI 4.0) [21].

2.2.The Food and Beverage Industry

Three different types of the production process can be found in the food and beverage industry [23]:

batch process for the production of finite quantities of material by subjecting quantities of input material

continuous process for the continuous material flow through processing equipment; discrete process for

the production of units moving between processing stations.The differences of the food and beverage

industry from the other manufacturing industries can be summarized as [24–26]: (i) the splitting and

mixing lots lead to a combination of divergent processes with convergent processes in the production;

(ii) production yields are uncertain as the property of materials is changing over time; (iii) products or

semi-finished products are recycled during the production process; (iv) final products have a limited

shelf-life and deteriorate over time.

To ensure the quality and safety of the final products, the transparency through the production

must be enhanced to achieve efficient process management, which can be supported by the MES, as the

MES is connected to the shop floor and serves as the center delivering critical process information

to the co-systems [27]. Though researchers have analyzed the factors that can influence the choice

of consumers for food and beverage [28], the price remains the most critical factor [29]. Due to the

low-profit margins,sectors in the food and beverage industry,for reasonable pricing of the final

products, have paid more attention to reduce the energy consumption and enhance the production

efficiency [30]. By understanding the consumption of energy resources globally, the MES can contribute

to managing and reducing energy consumption in the manufacturing processes [31]. MES can also

support the application of lean principles, as it provides real-time information to fees and /or validate

the lean processes to improve the efficiency of the production [32]. To satisfy the diverse demands of the

consumers, the variety of food and beverage products is growing in the market [33]. By the continuous

introduction of new products, the traditional ones can lose their viability in an unpredictable way [34].

The manufacturers have to shift their production strategy from make-to-stock to make-to-order to

improve production flexibility, scheduling timeliness, and further to react to the product dynamics.

The MES is considered as the basis for scheduling in the process industry, as the information form the

whole enterprise, such as the order delivery time, the use of processing materials, and the machine

Electronics 2020, 11, x FOR PEER REVIEW 3 of 21

Figure 1. Reference Architectural Model Industry 4.0 (RAMI 4.0) [21].

2.2. The Food and Beverage Industry

Three different types of the production process can be found in the food and beverage industry

[23]: batch process for the production of finite quantities of material by subjecting quantities of input

materials; continuous process for the continuous material flow through processing equipment;

discrete process for the production of units moving between processing stations. The differences of

the food and beverage industry from the other manufacturing industries can be summarized as [24–

26]: (i) the splitting and mixing lots lead to a combination of divergent processes with convergent

processes in the production; (ii) production yields are uncertain as the property of materials i

changing over time; (iii) products or semi-finished products are recycled during the production

process; (iv) final products have a limited shelf-life and deteriorate over time.

To ensure the quality and safety of the final products, the transparency through the production

must be enhanced to achieve efficient process management, which can be supported by the MES, as

the MES is connected to the shop floor and serves as the center delivering critical process information

to the co-systems [27]. Though researchers have analyzed the factors that can influence the choice of

consumers for food and beverage [28], the price remains the most critical factor [29]. Due to the low-

profit margins, sectors in the food and beverage industry, for reasonable pricing of the final products,

have paid more attention to reduce the energy consumption and enhance the production efficiency

[30]. By understanding the consumption of energy resources globally, the MES can contribute

managing and reducing energy consumption in the manufacturing processes [31]. MES can als

support the application of lean principles, as it provides real-time information to fees and/or validate

the lean processes to improve the efficiency of the production [32]. To satisfy the diverse demands of

the consumers, the variety of food and beverage products is growing in the market [33]. By t

continuousintroductionof new products, the traditionalones can lose their viability in an

unpredictable way [34]. The manufacturers have to shift their production strategy from make-to-

stock to make-to-order to improve production flexibility, scheduling timeliness, and further to react

to the product dynamics. The MES is considered as the basis for scheduling in the process industry,

as the information form the whole enterprise, such as the order delivery time, the use of processing

materials, and the machine availability, must be coupled to generate the production plans [35,36]. In

the new industrial automation environment, owing to its essential role as information center for data

Figure 1.Reference Architectural Model Industry 4.0 (RAMI 4.0) [21].

2.2.The Food and Beverage Industry

Three different types of the production process can be found in the food and beverage industry [23]:

batch process for the production of finite quantities of material by subjecting quantities of input material

continuous process for the continuous material flow through processing equipment; discrete process for

the production of units moving between processing stations.The differences of the food and beverage

industry from the other manufacturing industries can be summarized as [24–26]: (i) the splitting and

mixing lots lead to a combination of divergent processes with convergent processes in the production;

(ii) production yields are uncertain as the property of materials is changing over time; (iii) products or

semi-finished products are recycled during the production process; (iv) final products have a limited

shelf-life and deteriorate over time.

To ensure the quality and safety of the final products, the transparency through the production

must be enhanced to achieve efficient process management, which can be supported by the MES, as the

MES is connected to the shop floor and serves as the center delivering critical process information

to the co-systems [27]. Though researchers have analyzed the factors that can influence the choice

of consumers for food and beverage [28], the price remains the most critical factor [29]. Due to the

low-profit margins,sectors in the food and beverage industry,for reasonable pricing of the final

products, have paid more attention to reduce the energy consumption and enhance the production

efficiency [30]. By understanding the consumption of energy resources globally, the MES can contribute

to managing and reducing energy consumption in the manufacturing processes [31]. MES can also

support the application of lean principles, as it provides real-time information to fees and /or validate

the lean processes to improve the efficiency of the production [32]. To satisfy the diverse demands of the

consumers, the variety of food and beverage products is growing in the market [33]. By the continuous

introduction of new products, the traditional ones can lose their viability in an unpredictable way [34].

The manufacturers have to shift their production strategy from make-to-stock to make-to-order to

improve production flexibility, scheduling timeliness, and further to react to the product dynamics.

The MES is considered as the basis for scheduling in the process industry, as the information form the

whole enterprise, such as the order delivery time, the use of processing materials, and the machine

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040 4 of 21

availability, must be coupled to generate the production plans [35,36]. In the new industrial automation

environment,owing to its essential role as information center for data processing and providing

between the enterprise level and the automation layer, the modern technologies, such as Industry 4.0,

cyber-physical systems, and digital factory, are enabled by the MES to optimize the food and beverage

manufacturing processes [37,38].

2.3.MDE for Production Management Systems

To promote the reusability and to reduce the complexity of the software development process,

the concept of MDE has been researched and used in a wide range of industrial applications [39],

such as business imaging systems,electric systems for telecommunications,and robot operating

systems [40,41]. For the development of control systems, Alvarez et al. [42] developed a model-driven

approach named MeiA, which has integrated methods and techniques within the automation discipline,

provided more accessible verification procedures and structured designs, and improved productivity

by means of model reuse and code generation.In the area of business process management, the MDE

proposed a set of methodologies, which can bridge the gap between business analysts and software

developers [43]. Blal and Leshob [44] proposed a model-driven method to generate and specify

services of service-oriented systems from business models expressed by Business Process Model and

Notation (BPMN), a standardized graphical specification language for business process modeling and

automation [45]. Due to the support of the modular engineering process, management of heterogeneity

and complexity, reusability of design artifacts, MDE should not be waived to enable technologies

of Industry 4.0 [46]. An MDE framework (MDE4IoT) was introduced in [47] to generate Internet of

Things (IoT) systems supporting the modeling of Things and self-adaptation of connected systems.

Leal et al. [48] developed a model-driven approach (smartHMI4I4) providing reusable Application

Programming Interface (API) and widgets as a global framework to guide the HMI design and

generation for different devices across Industry 4.0 application scenarios.Binder et al. [49] proposed

a model-driven system development process integrating RAMI 4.0 to provide a common basis for

the development of Industry 4.0 systems reducing the complexity of engineering processes and

heterogeneity of platforms and toolsets.

For production management systems,some MDE approaches have already been established.

For the implementation of an ERP system, a model-driven approach was proposed using the MDA

framework by Dugerdil and Gaillard [50]. They defined a UML profile to model the business process

in the level of ERP and used models to describe the transformation.In their approach, the ERP system

was already implemented as a toolbox including different functional components.Instead of code

generation,the components can be enabled or disabled to fulfill the requirements of the business

process.A modeling approach that uses a state chart for describing and simulating the sequence of

operation in MES was presented in [51]. However, the focus was on the modeling and simulation

phase, and it lacked further steps for generating an operational system.Oliveira et al. [52] proposed

an interpretive MDE approach for enterprise applications and compared the productivity, profitabilit

and return on investment (ROI) between the generative and interpretive MDE approaches based on

its application to development of ERP systems.In this research,though the MDE concept has been

implemented,the used modeling language,models and their specifications,and the transformation

between them were not clarified.For the MES, an approach according to the MDA development method

was presented by Mizuoka and Koga [53], in which the UML and XML Metadata Interchange (XMI)

were used for modeling and platforms transforming.The application scenario of this approach was not

declared, and it was also mentioned that the UML as a general modeling language may not be suitabl

for modeling MES [54], because the MES modeling is related to the target business process and requires

interdisciplinary information from the co-workers of different departments, who may have different

views on the same production processes [55].

The MES Modeling Language (MES-ML)was developed as a modeling language for the

interdisciplinary specification of MES [56]. For the generation of operationalMES according to

availability, must be coupled to generate the production plans [35,36]. In the new industrial automation

environment,owing to its essential role as information center for data processing and providing

between the enterprise level and the automation layer, the modern technologies, such as Industry 4.0,

cyber-physical systems, and digital factory, are enabled by the MES to optimize the food and beverage

manufacturing processes [37,38].

2.3.MDE for Production Management Systems

To promote the reusability and to reduce the complexity of the software development process,

the concept of MDE has been researched and used in a wide range of industrial applications [39],

such as business imaging systems,electric systems for telecommunications,and robot operating

systems [40,41]. For the development of control systems, Alvarez et al. [42] developed a model-driven

approach named MeiA, which has integrated methods and techniques within the automation discipline,

provided more accessible verification procedures and structured designs, and improved productivity

by means of model reuse and code generation.In the area of business process management, the MDE

proposed a set of methodologies, which can bridge the gap between business analysts and software

developers [43]. Blal and Leshob [44] proposed a model-driven method to generate and specify

services of service-oriented systems from business models expressed by Business Process Model and

Notation (BPMN), a standardized graphical specification language for business process modeling and

automation [45]. Due to the support of the modular engineering process, management of heterogeneity

and complexity, reusability of design artifacts, MDE should not be waived to enable technologies

of Industry 4.0 [46]. An MDE framework (MDE4IoT) was introduced in [47] to generate Internet of

Things (IoT) systems supporting the modeling of Things and self-adaptation of connected systems.

Leal et al. [48] developed a model-driven approach (smartHMI4I4) providing reusable Application

Programming Interface (API) and widgets as a global framework to guide the HMI design and

generation for different devices across Industry 4.0 application scenarios.Binder et al. [49] proposed

a model-driven system development process integrating RAMI 4.0 to provide a common basis for

the development of Industry 4.0 systems reducing the complexity of engineering processes and

heterogeneity of platforms and toolsets.

For production management systems,some MDE approaches have already been established.

For the implementation of an ERP system, a model-driven approach was proposed using the MDA

framework by Dugerdil and Gaillard [50]. They defined a UML profile to model the business process

in the level of ERP and used models to describe the transformation.In their approach, the ERP system

was already implemented as a toolbox including different functional components.Instead of code

generation,the components can be enabled or disabled to fulfill the requirements of the business

process.A modeling approach that uses a state chart for describing and simulating the sequence of

operation in MES was presented in [51]. However, the focus was on the modeling and simulation

phase, and it lacked further steps for generating an operational system.Oliveira et al. [52] proposed

an interpretive MDE approach for enterprise applications and compared the productivity, profitabilit

and return on investment (ROI) between the generative and interpretive MDE approaches based on

its application to development of ERP systems.In this research,though the MDE concept has been

implemented,the used modeling language,models and their specifications,and the transformation

between them were not clarified.For the MES, an approach according to the MDA development method

was presented by Mizuoka and Koga [53], in which the UML and XML Metadata Interchange (XMI)

were used for modeling and platforms transforming.The application scenario of this approach was not

declared, and it was also mentioned that the UML as a general modeling language may not be suitabl

for modeling MES [54], because the MES modeling is related to the target business process and requires

interdisciplinary information from the co-workers of different departments, who may have different

views on the same production processes [55].

The MES Modeling Language (MES-ML)was developed as a modeling language for the

interdisciplinary specification of MES [56]. For the generation of operationalMES according to

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040 5 of 21

the MDE concept, the metamodel of MES-ML was extended [57]. With this extension, the components

of MES (plants,processes,MES functions,and reports) and their connections could be modeled

completely, and the extended MES-ML was validated with a modeling example, which proved the

feasibility of this language for the MDE of MES. However, it lacked an explanation of the steps that are

needed to represent the information in the model and for the transformation between di fferent models

for automatic MES generation.The concept of model-driven engineering for MES by using the extended

MES-ML was proposed first in 2017 [58]. Chen et al. [59] proposed in 2018 a model-driven approach

for MES with more details,which consisted of three steps,modeling,specifying,and generating.

Their research focused on the step of modeling with extended MES-ML that was integrated, in which

libraries for predefined modeling elements were introduced.The feasibility and the necessity of the

predefined modeling elements were also evaluated and proven by their research so that the basis for

the model-driven engineering of MES was established.However, details of the latter steps, including

specifying and generating, were not clarified.

3.Requirements on the Approach

Conventionally,seven phases are necessary to implementthe MES in a manufacturing

enterprise [60]: basic determination for determining the MES project scope and content; preplanning

for analyzing the business, production processes, and the MES functions; basic planning for evaluating

and drafting the MES concept and recommendation; realization planning for mapping the MES in

detail;implementation for installing and integrating the hardware and software;commissioning

for testing the MES software and training the users; completion for compiling the final report and

drafting project accounting.The specific business and manufacturing processes must be considered in

each phase to be executed, therefore, the MES must be adopted with considerable customizing and

programming effort, which is cost-intensive and error-prone [61,62].

Based on the facts that more than 99% of the enterprises in the food and beverage industry

are small- and medium-sized enterprises [63], and few rudiments of MES are specifically designed

to fulfill the requirements from the food and beverage industry with relatively low programming

and customizing effort, and further low cost, the MES implementation in the food and beverage is

hindered by the unavailability of the resources from the side of the end-users and the lack of methods

to reduce the implementation complexity from the side of the MES providers.Chen and Voigt [64]

analyzed the barriers for the MES implementation in the food and beverage industry combined with

their characteristics, and proposed solutions to deal with the barriers, i.e., the use of standardized

information model for the information exchange in the whole enterprise to reduce the integrating e ffort,

the service-oriented architecture for dividing the MES functions in independent services to achieve

higher reusability, and the model-driven concept for engineering the MES to reduce the programming

and customizing effort.Therefore, the requirements that should be fulfilled by the presented approach

are defined as:

- Requirement 1 (R1): Development of a feasible model-driven approach for the MES. The model-drive

approach should be designed so that it contains the necessary phases to carry the model information

from graphical modeling of the desired MES to specifying the solution details and then to the automa

generation of MES functions as well as their application according to the target business processes

Furthermore, the contents of the used platforms in each phase and their transformations must be

declared to ensure the interoperability of each phase and the correctness of the generated MES.

- Requirement 2 (R2):Representation of relevant MES functions in the food and beverage industry.

The manufacturers in the food and beverage industry need support from the MES to face

the challenges of reducing energy consumption,increasing production efficiency,improving

production flexibility, and remaining competitive.Therefore, the model-driven approach should

be able to represent the MES functions required by the manufacturing enterprises in the food

and beverage industry, such as energy management, KPIs calculation, production scheduling,

and predictive maintenance.Furthermore, considering the limited available resources of the food

the MDE concept, the metamodel of MES-ML was extended [57]. With this extension, the components

of MES (plants,processes,MES functions,and reports) and their connections could be modeled

completely, and the extended MES-ML was validated with a modeling example, which proved the

feasibility of this language for the MDE of MES. However, it lacked an explanation of the steps that are

needed to represent the information in the model and for the transformation between di fferent models

for automatic MES generation.The concept of model-driven engineering for MES by using the extended

MES-ML was proposed first in 2017 [58]. Chen et al. [59] proposed in 2018 a model-driven approach

for MES with more details,which consisted of three steps,modeling,specifying,and generating.

Their research focused on the step of modeling with extended MES-ML that was integrated, in which

libraries for predefined modeling elements were introduced.The feasibility and the necessity of the

predefined modeling elements were also evaluated and proven by their research so that the basis for

the model-driven engineering of MES was established.However, details of the latter steps, including

specifying and generating, were not clarified.

3.Requirements on the Approach

Conventionally,seven phases are necessary to implementthe MES in a manufacturing

enterprise [60]: basic determination for determining the MES project scope and content; preplanning

for analyzing the business, production processes, and the MES functions; basic planning for evaluating

and drafting the MES concept and recommendation; realization planning for mapping the MES in

detail;implementation for installing and integrating the hardware and software;commissioning

for testing the MES software and training the users; completion for compiling the final report and

drafting project accounting.The specific business and manufacturing processes must be considered in

each phase to be executed, therefore, the MES must be adopted with considerable customizing and

programming effort, which is cost-intensive and error-prone [61,62].

Based on the facts that more than 99% of the enterprises in the food and beverage industry

are small- and medium-sized enterprises [63], and few rudiments of MES are specifically designed

to fulfill the requirements from the food and beverage industry with relatively low programming

and customizing effort, and further low cost, the MES implementation in the food and beverage is

hindered by the unavailability of the resources from the side of the end-users and the lack of methods

to reduce the implementation complexity from the side of the MES providers.Chen and Voigt [64]

analyzed the barriers for the MES implementation in the food and beverage industry combined with

their characteristics, and proposed solutions to deal with the barriers, i.e., the use of standardized

information model for the information exchange in the whole enterprise to reduce the integrating e ffort,

the service-oriented architecture for dividing the MES functions in independent services to achieve

higher reusability, and the model-driven concept for engineering the MES to reduce the programming

and customizing effort.Therefore, the requirements that should be fulfilled by the presented approach

are defined as:

- Requirement 1 (R1): Development of a feasible model-driven approach for the MES. The model-drive

approach should be designed so that it contains the necessary phases to carry the model information

from graphical modeling of the desired MES to specifying the solution details and then to the automa

generation of MES functions as well as their application according to the target business processes

Furthermore, the contents of the used platforms in each phase and their transformations must be

declared to ensure the interoperability of each phase and the correctness of the generated MES.

- Requirement 2 (R2):Representation of relevant MES functions in the food and beverage industry.

The manufacturers in the food and beverage industry need support from the MES to face

the challenges of reducing energy consumption,increasing production efficiency,improving

production flexibility, and remaining competitive.Therefore, the model-driven approach should

be able to represent the MES functions required by the manufacturing enterprises in the food

and beverage industry, such as energy management, KPIs calculation, production scheduling,

and predictive maintenance.Furthermore, considering the limited available resources of the food

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040 6 of 21

and beverage manufacturing enterprises, the approach should be able to lower the programming

and customizing efforts during the engineering process.

- Requirement 3 (R3):Capability of data flow.To implement the developed model-driven approach

in different application scenarios without redefining the information interface,a consistent

communication standard between the shop floor level and MES level should be supported.

Additionally, a standardized communication interface should be used for data exchange to ensure

the portability of the modeling elements, which are predefined and to be reused.

- Requirement 4 (R4):Automatic adoption of the generated MES. The model-driven approach

should not be defined to serve definite application scenarios but could be applied to fulfill various

demands on the MES from different domains.Thus, the basic elements that were used to establish

the MES model must be defined neutrally.Due to the flexible sequence of the basic elements and

further the information flow, the MES that modeled with the basic elements should be generated

dynamically, so that it can be adopted automatically to each specific application scenario.

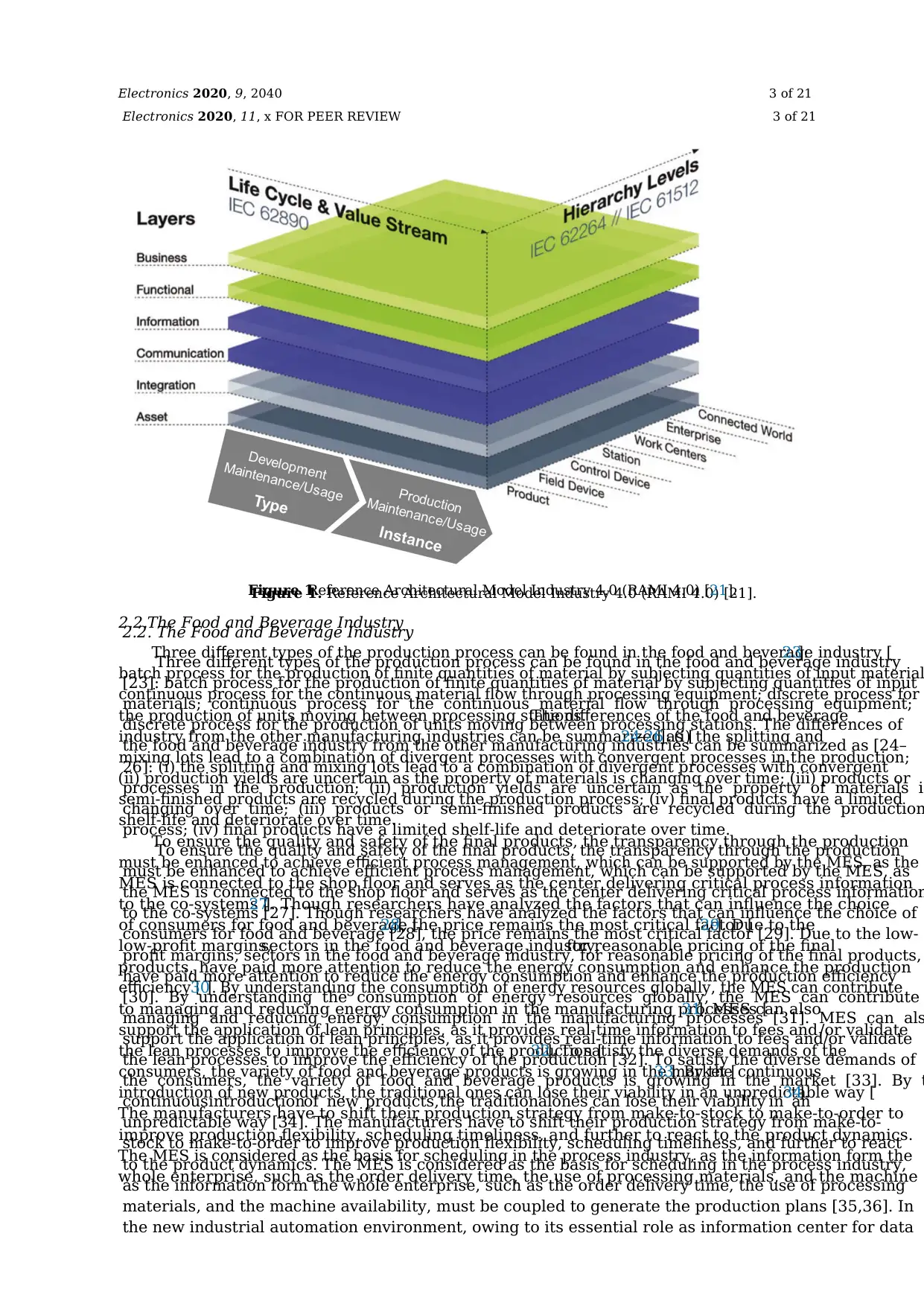

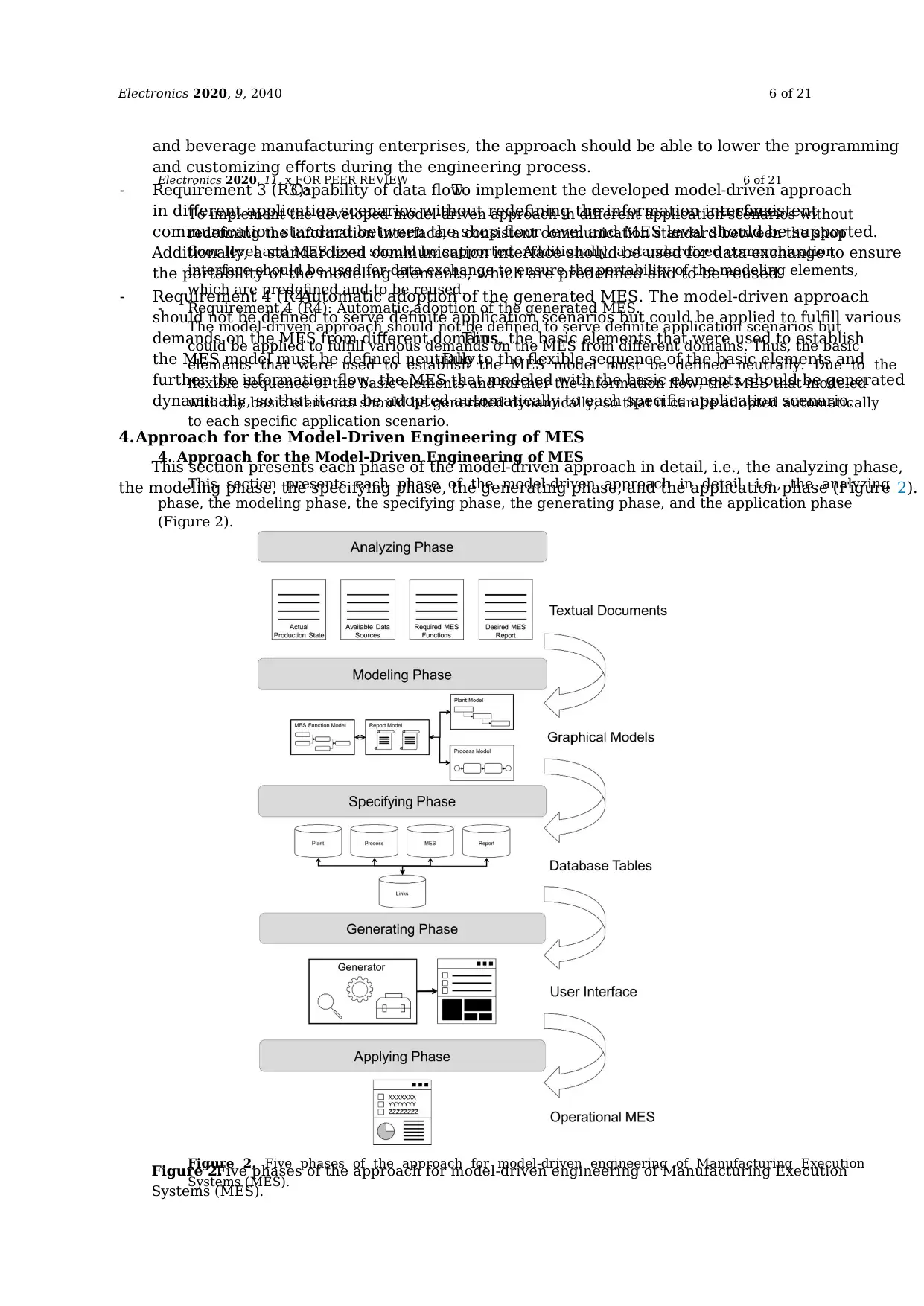

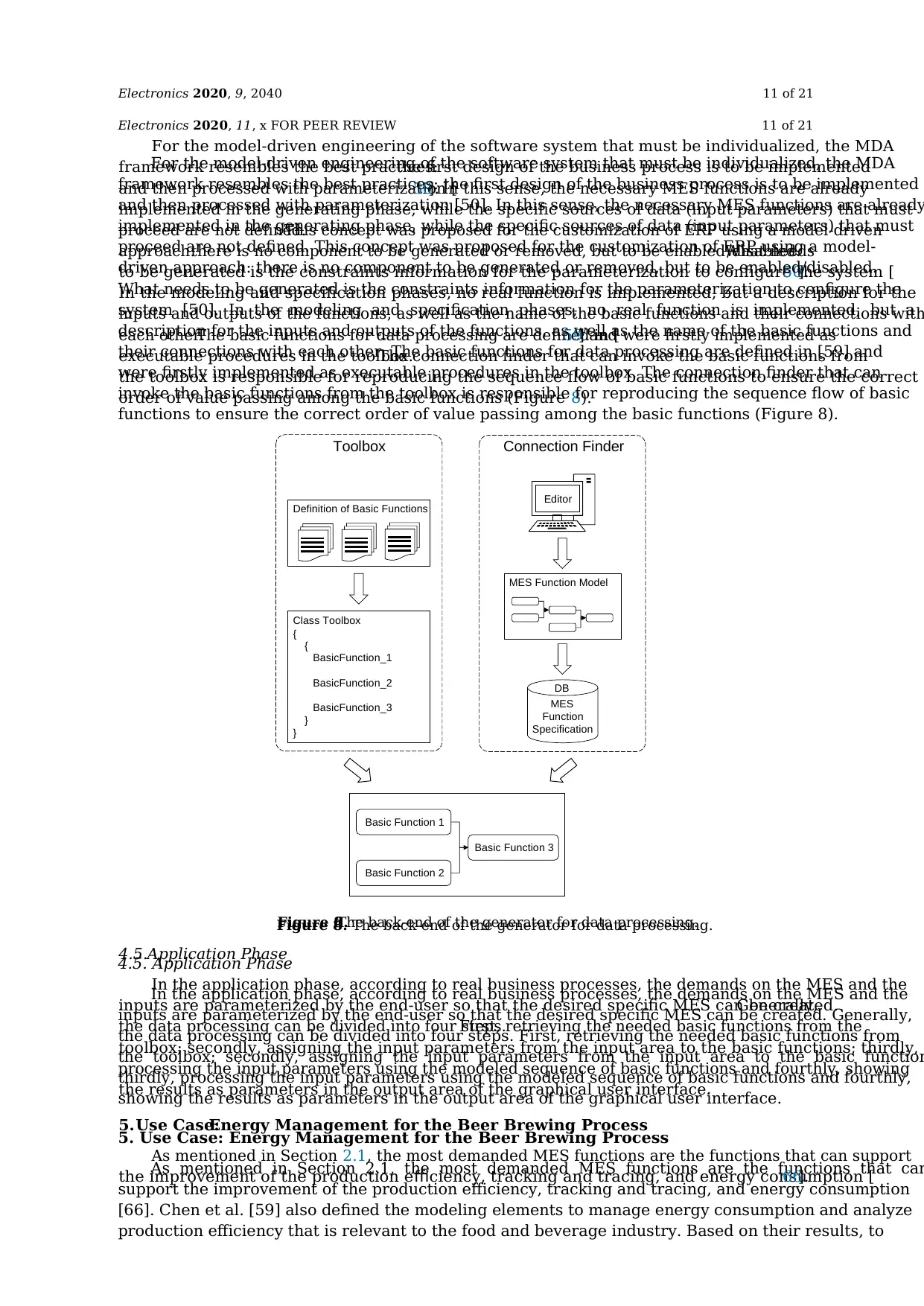

4.Approach for the Model-Driven Engineering of MES

This section presents each phase of the model-driven approach in detail, i.e., the analyzing phase,

the modeling phase, the specifying phase, the generating phase, and the application phase (Figure 2).

Electronics 2020, 11, x FOR PEER REVIEW 6 of 21

To implement the developed model-driven approach in different application scenarios without

redefining the information interface, a consistent communication standard between the shop

floor level and MES level should be supported. Additionally, a standardized communication

interface should be used for data exchange to ensure the portability of the modeling elements,

which are predefined and to be reused.

- Requirement 4 (R4): Automatic adoption of the generated MES.

The model-driven approach should not be defined to serve definite application scenarios but

could be applied to fulfill various demands on the MES from different domains. Thus, the basic

elements that were used to establish the MES model must be defined neutrally. Due to the

flexible sequence of the basic elements and further the information flow, the MES that modeled

with the basic elements should be generated dynamically, so that it can be adopted automatically

to each specific application scenario.

4. Approach for the Model-Driven Engineering of MES

This section presents each phase of the model-driven approach in detail, i.e., the analyzing

phase, the modeling phase, the specifying phase, the generating phase, and the application phase

(Figure 2).

Figure 2. Five phases of the approach for model-driven engineering of Manufacturing Execution

Systems (MES).

Figure 2.Five phases of the approach for model-driven engineering of Manufacturing Execution

Systems (MES).

and beverage manufacturing enterprises, the approach should be able to lower the programming

and customizing efforts during the engineering process.

- Requirement 3 (R3):Capability of data flow.To implement the developed model-driven approach

in different application scenarios without redefining the information interface,a consistent

communication standard between the shop floor level and MES level should be supported.

Additionally, a standardized communication interface should be used for data exchange to ensure

the portability of the modeling elements, which are predefined and to be reused.

- Requirement 4 (R4):Automatic adoption of the generated MES. The model-driven approach

should not be defined to serve definite application scenarios but could be applied to fulfill various

demands on the MES from different domains.Thus, the basic elements that were used to establish

the MES model must be defined neutrally.Due to the flexible sequence of the basic elements and

further the information flow, the MES that modeled with the basic elements should be generated

dynamically, so that it can be adopted automatically to each specific application scenario.

4.Approach for the Model-Driven Engineering of MES

This section presents each phase of the model-driven approach in detail, i.e., the analyzing phase,

the modeling phase, the specifying phase, the generating phase, and the application phase (Figure 2).

Electronics 2020, 11, x FOR PEER REVIEW 6 of 21

To implement the developed model-driven approach in different application scenarios without

redefining the information interface, a consistent communication standard between the shop

floor level and MES level should be supported. Additionally, a standardized communication

interface should be used for data exchange to ensure the portability of the modeling elements,

which are predefined and to be reused.

- Requirement 4 (R4): Automatic adoption of the generated MES.

The model-driven approach should not be defined to serve definite application scenarios but

could be applied to fulfill various demands on the MES from different domains. Thus, the basic

elements that were used to establish the MES model must be defined neutrally. Due to the

flexible sequence of the basic elements and further the information flow, the MES that modeled

with the basic elements should be generated dynamically, so that it can be adopted automatically

to each specific application scenario.

4. Approach for the Model-Driven Engineering of MES

This section presents each phase of the model-driven approach in detail, i.e., the analyzing

phase, the modeling phase, the specifying phase, the generating phase, and the application phase

(Figure 2).

Figure 2. Five phases of the approach for model-driven engineering of Manufacturing Execution

Systems (MES).

Figure 2.Five phases of the approach for model-driven engineering of Manufacturing Execution

Systems (MES).

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040 7 of 21

To ensure the consistency of data flow in the horizontal transformation from model to the operable

system,as well as in the vertical integration between the automation level and enterprise level,

“Weihenstephan Standards (WS)” [65] are integrated in this approach,which are widely used in

the food and beverage industry.The WS is a standard information model that defines a universal

communication interface for the communication between different process control systems and the

MES. With WS, the processing of the machine and process data could be consistently defined for the

MES functions.To ensure the portability of models, WS is used as the primary information model

through the whole approach.The following sections present the engineering processes, the tasks,

and the related tools of each phase.

4.1.Analyzing Phase

As the preliminary study before the modeling phase, the actual state of the production plant

and its processes with their acquirable data sources,the demands on the MES functions,and the

desired MES reports should be analyzed.This phase is addressed primarily at the end-users.The main

concepts and entities of the domain are analyzed.Multiple co-workers (end-users with internal and/or

external solution analysts) with different focuses and working backgrounds must work together to

figure out the proper MES functions as well as the information flow among departments in a completed

MES [56]. The results of this phase are textual specification sheets indicating the actual stand of the

production state (technical systems and production processes), the available data sources from the

production, the required functions, and the desired report of the MES.

4.2.Modeling Phase

At the modeling phase, the MES that fulfill the demands in the first phase must be modeled,

based on the results of the analyzing phase.The extended MES Modeling Language (MES-ML) is a

formal modeling language and was proven to be suitable for modeling the MES with a model-driven

concept [57]. An editor that supports the extended MES-ML can assist the modeling process.The output

of the modeling phase is a completed graphical model of the MES containing the necessary information

for the transformation and generation in the later phases.

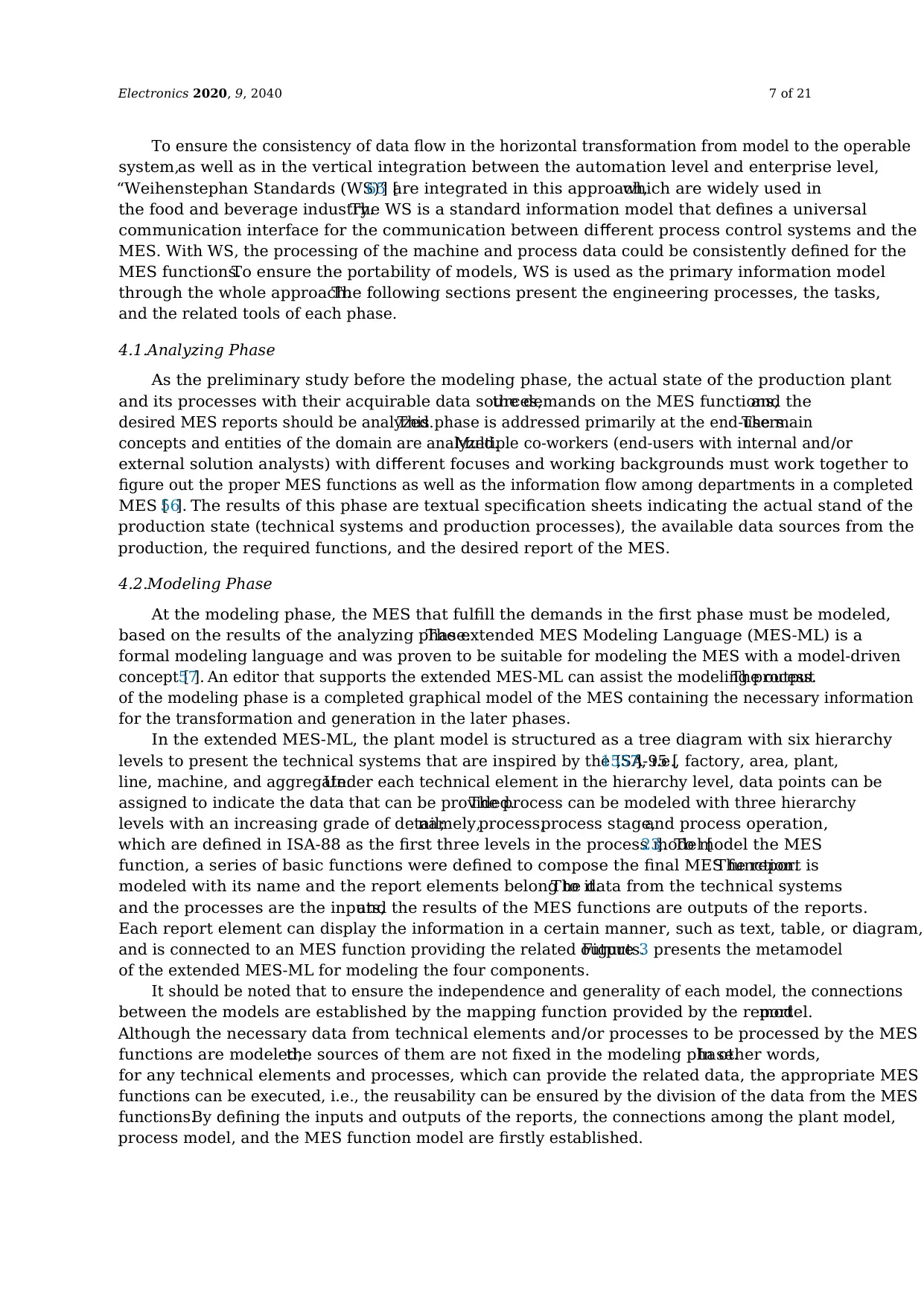

In the extended MES-ML, the plant model is structured as a tree diagram with six hierarchy

levels to present the technical systems that are inspired by the ISA-95 [15,57], i.e., factory, area, plant,

line, machine, and aggregate.Under each technical element in the hierarchy level, data points can be

assigned to indicate the data that can be provided.The process can be modeled with three hierarchy

levels with an increasing grade of detail;namely,process,process stage,and process operation,

which are defined in ISA-88 as the first three levels in the process model [23]. To model the MES

function, a series of basic functions were defined to compose the final MES function.The report is

modeled with its name and the report elements belong to it.The data from the technical systems

and the processes are the inputs,and the results of the MES functions are outputs of the reports.

Each report element can display the information in a certain manner, such as text, table, or diagram,

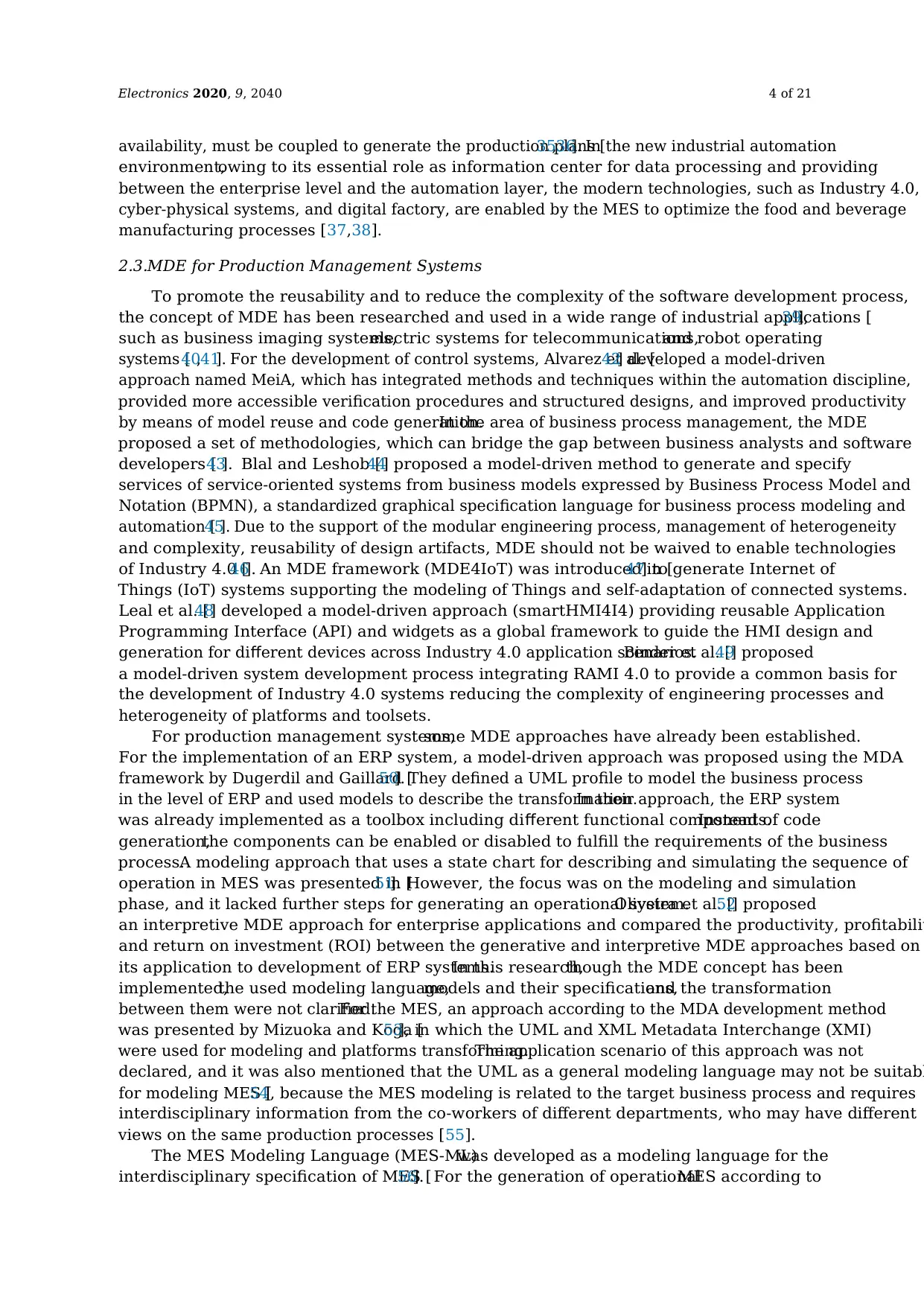

and is connected to an MES function providing the related outputs.Figure 3 presents the metamodel

of the extended MES-ML for modeling the four components.

It should be noted that to ensure the independence and generality of each model, the connections

between the models are established by the mapping function provided by the reportmodel.

Although the necessary data from technical elements and/or processes to be processed by the MES

functions are modeled,the sources of them are not fixed in the modeling phase.In other words,

for any technical elements and processes, which can provide the related data, the appropriate MES

functions can be executed, i.e., the reusability can be ensured by the division of the data from the MES

functions.By defining the inputs and outputs of the reports, the connections among the plant model,

process model, and the MES function model are firstly established.

To ensure the consistency of data flow in the horizontal transformation from model to the operable

system,as well as in the vertical integration between the automation level and enterprise level,

“Weihenstephan Standards (WS)” [65] are integrated in this approach,which are widely used in

the food and beverage industry.The WS is a standard information model that defines a universal

communication interface for the communication between different process control systems and the

MES. With WS, the processing of the machine and process data could be consistently defined for the

MES functions.To ensure the portability of models, WS is used as the primary information model

through the whole approach.The following sections present the engineering processes, the tasks,

and the related tools of each phase.

4.1.Analyzing Phase

As the preliminary study before the modeling phase, the actual state of the production plant

and its processes with their acquirable data sources,the demands on the MES functions,and the

desired MES reports should be analyzed.This phase is addressed primarily at the end-users.The main

concepts and entities of the domain are analyzed.Multiple co-workers (end-users with internal and/or

external solution analysts) with different focuses and working backgrounds must work together to

figure out the proper MES functions as well as the information flow among departments in a completed

MES [56]. The results of this phase are textual specification sheets indicating the actual stand of the

production state (technical systems and production processes), the available data sources from the

production, the required functions, and the desired report of the MES.

4.2.Modeling Phase

At the modeling phase, the MES that fulfill the demands in the first phase must be modeled,

based on the results of the analyzing phase.The extended MES Modeling Language (MES-ML) is a

formal modeling language and was proven to be suitable for modeling the MES with a model-driven

concept [57]. An editor that supports the extended MES-ML can assist the modeling process.The output

of the modeling phase is a completed graphical model of the MES containing the necessary information

for the transformation and generation in the later phases.

In the extended MES-ML, the plant model is structured as a tree diagram with six hierarchy

levels to present the technical systems that are inspired by the ISA-95 [15,57], i.e., factory, area, plant,

line, machine, and aggregate.Under each technical element in the hierarchy level, data points can be

assigned to indicate the data that can be provided.The process can be modeled with three hierarchy

levels with an increasing grade of detail;namely,process,process stage,and process operation,

which are defined in ISA-88 as the first three levels in the process model [23]. To model the MES

function, a series of basic functions were defined to compose the final MES function.The report is

modeled with its name and the report elements belong to it.The data from the technical systems

and the processes are the inputs,and the results of the MES functions are outputs of the reports.

Each report element can display the information in a certain manner, such as text, table, or diagram,

and is connected to an MES function providing the related outputs.Figure 3 presents the metamodel

of the extended MES-ML for modeling the four components.

It should be noted that to ensure the independence and generality of each model, the connections

between the models are established by the mapping function provided by the reportmodel.

Although the necessary data from technical elements and/or processes to be processed by the MES

functions are modeled,the sources of them are not fixed in the modeling phase.In other words,

for any technical elements and processes, which can provide the related data, the appropriate MES

functions can be executed, i.e., the reusability can be ensured by the division of the data from the MES

functions.By defining the inputs and outputs of the reports, the connections among the plant model,

process model, and the MES function model are firstly established.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040 8 of 21

Electronics 2020, 11, x FOR PEER REVIEW 8 of 21

Figure 3. Metamodel of the modeling language MES Modeling Language (MES-ML) [57,59].

4.3. Specifying Phase

Following the modeling phase, taking the graphicalMES model as the input, an MES

specification as the output of the specifying phase is filled. The primary task of this phase is t

transform the information from the graphical models into a format that software can utilize. The

database tables are the platform for the MES specification. Different tables related to the four models

in the modeling phase are defined to represent the information in the graphical model. In this phase,

the transformation process is a mapping process, as the structure, content, and the relationship of the

tables were defined as a one-to-one mapping of the extended MES-ML metamodel. This phase can

be performed automatically by using a mapping tool that knows the relationship between the

metamodel of the extended MES-ML and the database tables.

In the following, the related logical entity-relationship diagrams (ERD) of the database are

presented using Crow’s Foot Notation. As the technical systems are modeled using different

hierarchies and the data points for collection can be assigned to each element in the plant model

(according to the meta model of MES-ML), two tables named “Location” and “LocationDataPoint”

are used to describe the plant model (Figure 4, left). The table “Location” contains attributes that are

identical to the hierarchy level of the plant metamodel with factory, area, plant, line, machine, and

aggregatebeing used to present the modeling elements on each hierarchy. The table

“LocationDataPoint” presents the data points on each element. The types and descriptions of the data

points can also be found with the attributes “DataPointType” and “DataPointDescription”. Besides

that, the attribute named “LocationLink” is made to indicate the relationship between a specific data

point and its host element. Similar to the plant model, the information in the process model can be

represented with two tables named “Process” and “ProcessDataPoint” (Figure 4, right). The name of

the modeling elements on each hierarchy level in the process model can be found in the “Process”

table. The type of the used process data points and their link to the process element can be described

with the attributes “DataPointType” and “ProcessLink.” Another table to indicate the correlation

between the plant model and the process model is also defined (Figure 4, middle). By using the two

attributes “ProcessLink” and “LocationLink” in the “LocationProcess” table, the link between the

processes and technical systems can be found.

Figure 3.Metamodel of the modeling language MES Modeling Language (MES-ML) [57,59].

4.3.Specifying Phase

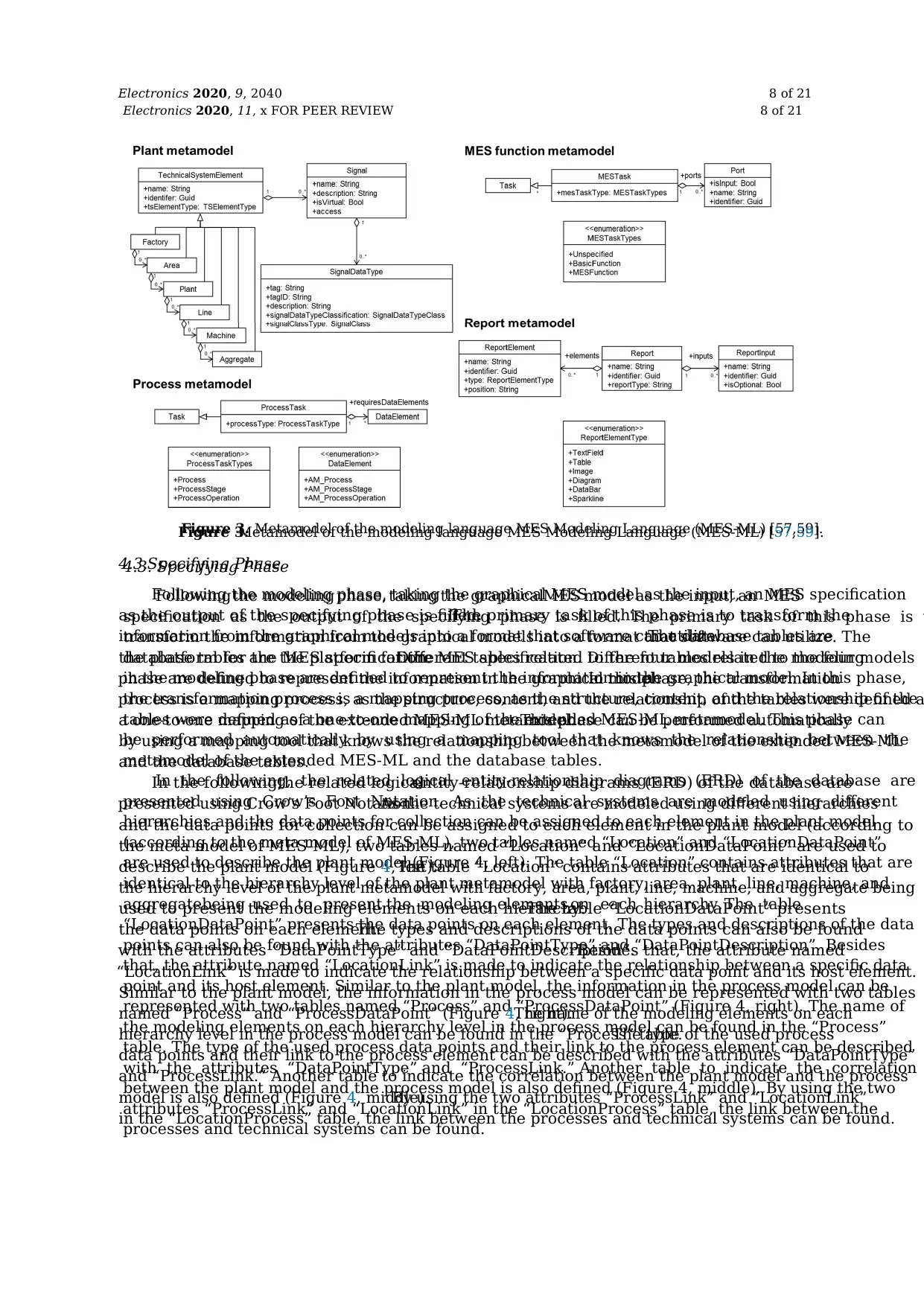

Following the modeling phase, taking the graphical MES model as the input, an MES specification

as the output of the specifying phase is filled.The primary task of this phase is to transform the

information from the graphical models into a format that software can utilize.The database tables are

the platform for the MES specification.Different tables related to the four models in the modeling

phase are defined to represent the information in the graphical model.In this phase, the transformation

process is a mapping process, as the structure, content, and the relationship of the tables were defined a

a one-to-one mapping of the extended MES-ML metamodel.This phase can be performed automatically

by using a mapping tool that knows the relationship between the metamodel of the extended MES-ML

and the database tables.

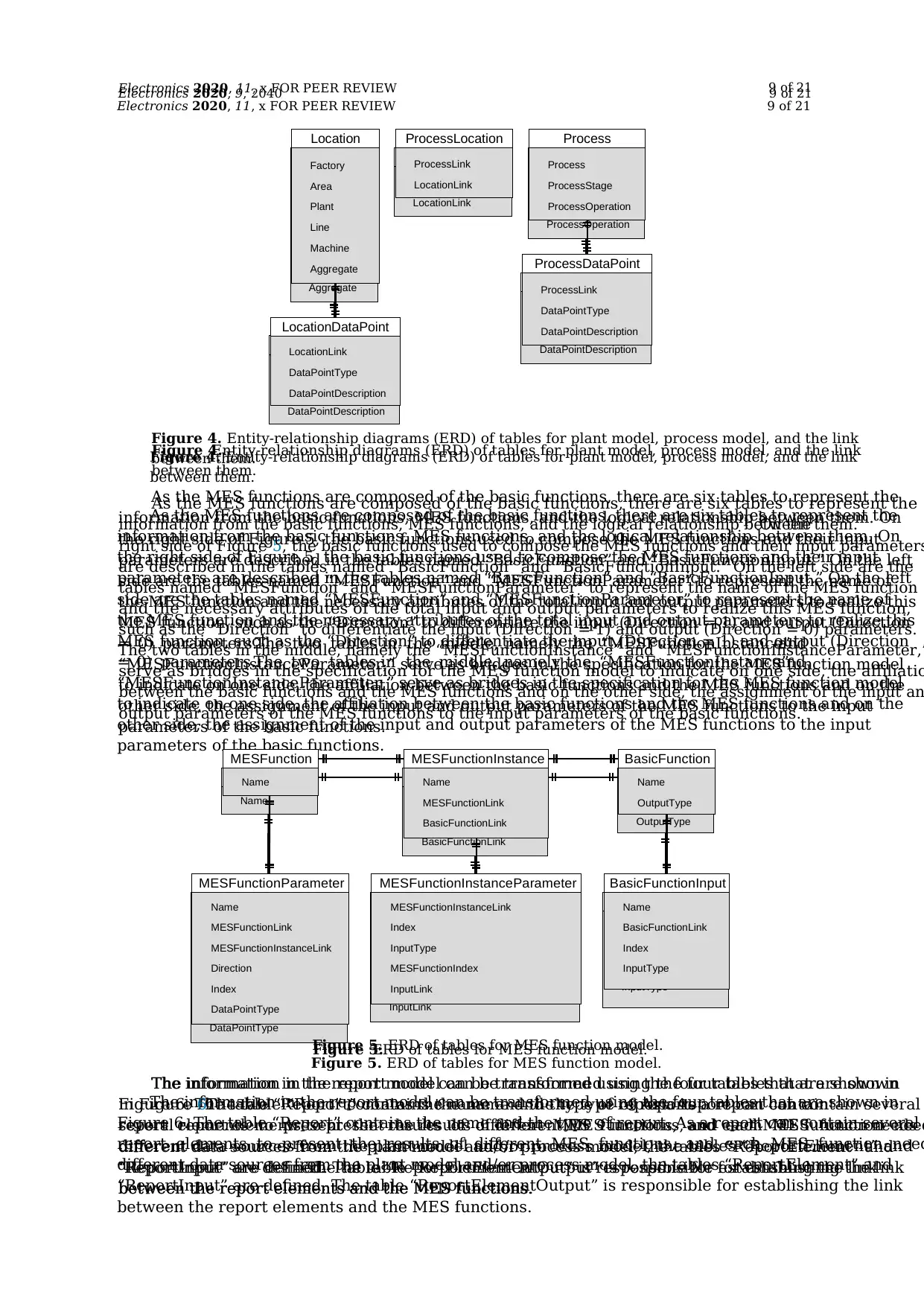

In the following,the related logicalentity-relationship diagrams (ERD) of the database are

presented using Crow’s Foot Notation.As the technical systems are modeled using different hierarchies

and the data points for collection can be assigned to each element in the plant model (according to

the meta model of MES-ML), two tables named “Location” and “LocationDataPoint” are used to

describe the plant model (Figure 4, left).The table “Location” contains attributes that are identical to

the hierarchy level of the plant metamodel with factory, area, plant, line, machine, and aggregate being

used to present the modeling elements on each hierarchy.The table “LocationDataPoint” presents

the data points on each element.The types and descriptions of the data points can also be found

with the attributes “DataPointType” and “DataPointDescription”.Besides that, the attribute named

“LocationLink” is made to indicate the relationship between a specific data point and its host element.

Similar to the plant model, the information in the process model can be represented with two tables

named “Process” and “ProcessDataPoint” (Figure 4, right).The name of the modeling elements on each

hierarchy level in the process model can be found in the “Process” table.The type of the used process

data points and their link to the process element can be described with the attributes “DataPointType”

and “ProcessLink.” Another table to indicate the correlation between the plant model and the process

model is also defined (Figure 4, middle).By using the two attributes “ProcessLink” and “LocationLink”

in the “LocationProcess” table, the link between the processes and technical systems can be found.

Electronics 2020, 11, x FOR PEER REVIEW 8 of 21

Figure 3. Metamodel of the modeling language MES Modeling Language (MES-ML) [57,59].

4.3. Specifying Phase

Following the modeling phase, taking the graphicalMES model as the input, an MES

specification as the output of the specifying phase is filled. The primary task of this phase is t

transform the information from the graphical models into a format that software can utilize. The

database tables are the platform for the MES specification. Different tables related to the four models

in the modeling phase are defined to represent the information in the graphical model. In this phase,

the transformation process is a mapping process, as the structure, content, and the relationship of the

tables were defined as a one-to-one mapping of the extended MES-ML metamodel. This phase can

be performed automatically by using a mapping tool that knows the relationship between the

metamodel of the extended MES-ML and the database tables.

In the following, the related logical entity-relationship diagrams (ERD) of the database are

presented using Crow’s Foot Notation. As the technical systems are modeled using different

hierarchies and the data points for collection can be assigned to each element in the plant model

(according to the meta model of MES-ML), two tables named “Location” and “LocationDataPoint”

are used to describe the plant model (Figure 4, left). The table “Location” contains attributes that are

identical to the hierarchy level of the plant metamodel with factory, area, plant, line, machine, and

aggregatebeing used to present the modeling elements on each hierarchy. The table

“LocationDataPoint” presents the data points on each element. The types and descriptions of the data

points can also be found with the attributes “DataPointType” and “DataPointDescription”. Besides

that, the attribute named “LocationLink” is made to indicate the relationship between a specific data

point and its host element. Similar to the plant model, the information in the process model can be

represented with two tables named “Process” and “ProcessDataPoint” (Figure 4, right). The name of

the modeling elements on each hierarchy level in the process model can be found in the “Process”

table. The type of the used process data points and their link to the process element can be described

with the attributes “DataPointType” and “ProcessLink.” Another table to indicate the correlation

between the plant model and the process model is also defined (Figure 4, middle). By using the two

attributes “ProcessLink” and “LocationLink” in the “LocationProcess” table, the link between the

processes and technical systems can be found.

Figure 3.Metamodel of the modeling language MES Modeling Language (MES-ML) [57,59].

4.3.Specifying Phase

Following the modeling phase, taking the graphical MES model as the input, an MES specification

as the output of the specifying phase is filled.The primary task of this phase is to transform the

information from the graphical models into a format that software can utilize.The database tables are

the platform for the MES specification.Different tables related to the four models in the modeling

phase are defined to represent the information in the graphical model.In this phase, the transformation

process is a mapping process, as the structure, content, and the relationship of the tables were defined a

a one-to-one mapping of the extended MES-ML metamodel.This phase can be performed automatically

by using a mapping tool that knows the relationship between the metamodel of the extended MES-ML

and the database tables.

In the following,the related logicalentity-relationship diagrams (ERD) of the database are

presented using Crow’s Foot Notation.As the technical systems are modeled using different hierarchies

and the data points for collection can be assigned to each element in the plant model (according to

the meta model of MES-ML), two tables named “Location” and “LocationDataPoint” are used to

describe the plant model (Figure 4, left).The table “Location” contains attributes that are identical to

the hierarchy level of the plant metamodel with factory, area, plant, line, machine, and aggregate being

used to present the modeling elements on each hierarchy.The table “LocationDataPoint” presents

the data points on each element.The types and descriptions of the data points can also be found

with the attributes “DataPointType” and “DataPointDescription”.Besides that, the attribute named

“LocationLink” is made to indicate the relationship between a specific data point and its host element.

Similar to the plant model, the information in the process model can be represented with two tables

named “Process” and “ProcessDataPoint” (Figure 4, right).The name of the modeling elements on each

hierarchy level in the process model can be found in the “Process” table.The type of the used process

data points and their link to the process element can be described with the attributes “DataPointType”

and “ProcessLink.” Another table to indicate the correlation between the plant model and the process

model is also defined (Figure 4, middle).By using the two attributes “ProcessLink” and “LocationLink”

in the “LocationProcess” table, the link between the processes and technical systems can be found.

Electronics 2020, 9, 2040 9 of 21

Electronics 2020, 11, x FOR PEER REVIEW 9 of 21

Figure 4. Entity-relationship diagrams (ERD) of tables for plant model, process model, and the link

between them.

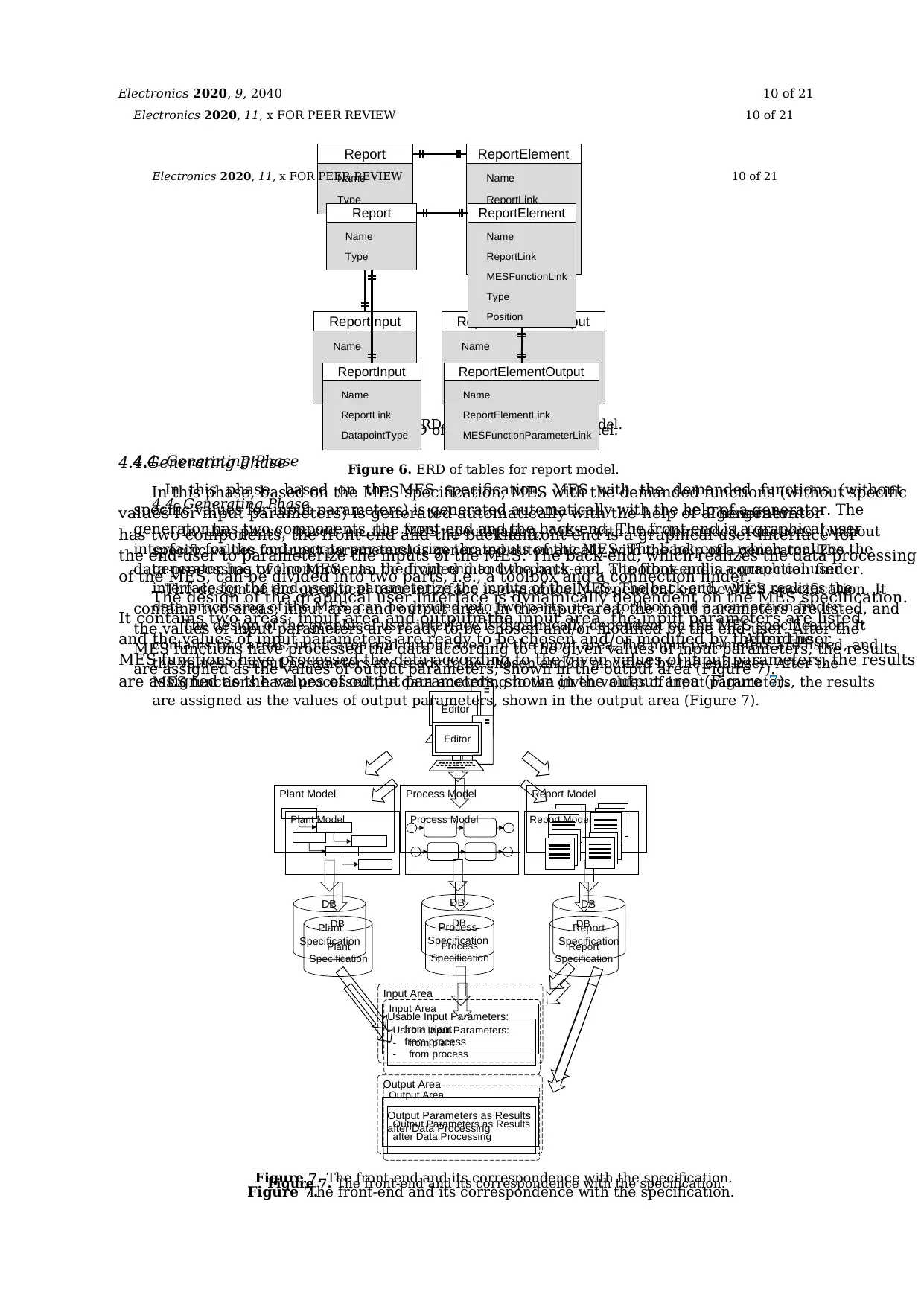

As the MES functions are composed of the basic functions, there are six tables to represent the

information from the basic functions, MES functions, and the logical relationship between them. On

the right side of Figure 5, the basic functions used to compose the MES functions and their input

parameters are described in the tables named “BasicFunction” and “BasicFunctionInput.” On the left

side are the tables named “MESFunction” and “MESFunctionParameter” to represent the name of

the MES function and the necessary attributes of the total input and output parameters to realize this

MES function, such as the “Direction” to differentiate the input (Direction = 1) and output (Direction

= 0) parameters.The two tables in the middle, namely the “MESFunctionInstance”and

“MESFunctionInstanceParameter,” serve as bridges in the specification for the MES function model

to indicate on one side, the affiliation between the basic functions and the MES functions and on the

other side, the assignment of the input and output parameters of the MES functions to the input

parameters of the basic functions.

Figure 5. ERD of tables for MES function model.

The information in the report model can be transformed using the four tables that are shown in

Figure 6. The table “Report” contains the name and the type of report. As a report can contain several

report elements to present the results of different MES functions, and each MES function need

different data sources from the plant model and/or process model, the tables “ReportElement” and

“ReportInput” are defined. The table “ReportElementOutput” is responsible for establishing the link

between the report elements and the MES functions.

Factory

Area

Plant

Line

Machine

Aggregate

Location

LocationLink

DataPointType

DataPointDescription

LocationDataPoint

ProcessLink

LocationLink

ProcessLocation

Process

ProcessStage

ProcessOperation

Process

ProcessLink

DataPointType

DataPointDescription

ProcessDataPoint

Name

MESFunction

Name

MESFunctionLink

MESFunctionInstanceLink

Direction

Index

DataPointType

MESFunctionParameter

Name

MESFunctionLink

BasicFunctionLink

MESFunctionInstance

MESFunctionInstanceLink

Index

InputType

MESFunctionIndex

InputLink

MESFunctionInstanceParameter

Name

OutputType

BasicFunction

Name

BasicFunctionLink

Index

InputType

BasicFunctionInput

Figure 4.Entity-relationship diagrams (ERD) of tables for plant model, process model, and the link

between them.

As the MES functions are composed of the basic functions, there are six tables to represent the

information from the basic functions, MES functions, and the logical relationship between them.On the