Motivational Interviewing Training with Simulation for Opioid Abuse

VerifiedAdded on 2022/09/03

|9

|7385

|40

Report

AI Summary

This research article investigates the effectiveness of motivational interviewing (MI) training, incorporating didactic lectures, role-playing exercises, and standardized patient (SP) simulation, on the learning outcomes of Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) students. The study, employing a one-group pretest-posttest design, aimed to enhance students' knowledge and confidence in managing prescription opioid abuse among older adults. Findings revealed significant improvements in both knowledge and confidence levels post-training. The study highlights the potential of MI training with SP simulation to improve care for older adults who misuse opioids, addressing a critical healthcare issue. The research underscores the importance of integrating MI into healthcare curricula to equip future providers with effective behavioral intervention skills.

Perspect Psychiatr Care.2019;55:681-689. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/ppc © 2019 Wiley Periodicals,Inc. | 681

Received:24 September 2018| Revised: 14 April 2019| Accepted:5 May 2019

DOI: 10.1111/ppc.12402

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

Motivational interviewing training with standardized patient

simulation for prescription opioid abuse among older adults

Yu‐Ping Chang PhD,RN, FGSA, FAAN 1 | Jade Cassalia DNP,FNP‐C2 |

Molli Warunek DNP,FNP‐C1 | Yvonne Scherer EdD,RN1

1School of Nursing,The State University of

New York,University at Buffalo,Buffalo,New

York

2Newark‐Wayne Community Hospital,

Rochester,New York

Correspondence

Yu‐Ping Chang PhD,RN, FGSA,FAAN, School

of Nursing,The State University of New York,

University at Buffalo,Buffalo,3435 Main

Street,Wende Hall Rm 301C,Buffalo,NY

14214.

Email:yc73@buffalo.edu

Funding information

Health Foundation for Western and Central

New York

Abstract

Purpose:This study aimed to examine the effect of motivationalinterviewing (MI)

education on the doctorate of nursing practice (DNP) students’learning outcomes.

Design and methods:This study used a one‐group with preposttestdesign.The

sample consisted of31 DNP students who received an MI training,including a

didactic lecture,role‐playing exercise,and standardized patient simulation.

Findings: Findings indicated a significantincrease in students’knowledge and

confidence regarding MI at both posttests compared with baseline.

Practice implications: Findings suggested that MI training with standardized patient

simulation demonstrated preliminary promising effects on DNP students’knowledge

and confidence in MI techniques to manage prescription opioid abuse among older

adults. This study showed the potential to enhance the care of older adults who abuse

opioids to address this problem in practice.

K E Y W O R D S

chronic pain,motivationalinterviewing,older adults,prescription opioid misuse,standardized

patient simulation

1 | INTRODUCTION

Prescription opioids are a common strategy for managing chronic

pain in older adults.1 The use of these medications in the older adult

population has increased nine‐fold between the years of1995 to

2010.2 It has been found that 92% of older adults that were

prescribed opioids had been on them for a period of5 years or

more.3 Opioids are being used more frequently and for longer

periods of time to treat patients experiencing chronic pain.4 As the

use of opioids has increased, there has been a corresponding increase

in their misuse or abuse.5 In 2012, 2.9 million older adults in America

reported nonmedical use of their prescription drugs.6 In addition, the

rates of older adults being admitted into facilities for treatment of

prescription drug abuse has increased from 0.7% to 3.5% between

the years of 1992 to 2005.3 As the population of older adults

increases,especially with the aging of baby boomers,it is expected

that providers will be faced with increased incidences of chronic pain.

Inevitably,this will lead to increased prescription opioid use by the

older adult population, thereby increasing the potential for misuse or

abuse.7

The question raised by this growing problem is how to properly

intervene in older adults with chronic pain who misuse or abuse their

prescription opioids?Currently, there is limited information on

effective interventionsfor substance use disorder(SUD) among

older adults.However,there are severalavailable evidence‐based

practice approaches for the treatment ofSUD within the general

population.One approach is the use of motivationalinterviewing

(MI). MI is a patient‐centered,semi‐directive cognitive behavioral

method that focuses on enhancing intrinsic motivation,and auton-

omy to change behavior.8 Clinicians help patients identify problem

behaviors,resolve ambivalence,determine and enhance motivation,

and aid in problem‐solving and goalsetting.9 MI has been demon-

strated to be effective in patient health behavior outcomes, including

substance abuse.8,9 There are studies that support the efficacy of MI

on behavior change among older adults to address a variety of health

care issues including physical activity, general health, smoking

Received:24 September 2018| Revised: 14 April 2019| Accepted:5 May 2019

DOI: 10.1111/ppc.12402

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

Motivational interviewing training with standardized patient

simulation for prescription opioid abuse among older adults

Yu‐Ping Chang PhD,RN, FGSA, FAAN 1 | Jade Cassalia DNP,FNP‐C2 |

Molli Warunek DNP,FNP‐C1 | Yvonne Scherer EdD,RN1

1School of Nursing,The State University of

New York,University at Buffalo,Buffalo,New

York

2Newark‐Wayne Community Hospital,

Rochester,New York

Correspondence

Yu‐Ping Chang PhD,RN, FGSA,FAAN, School

of Nursing,The State University of New York,

University at Buffalo,Buffalo,3435 Main

Street,Wende Hall Rm 301C,Buffalo,NY

14214.

Email:yc73@buffalo.edu

Funding information

Health Foundation for Western and Central

New York

Abstract

Purpose:This study aimed to examine the effect of motivationalinterviewing (MI)

education on the doctorate of nursing practice (DNP) students’learning outcomes.

Design and methods:This study used a one‐group with preposttestdesign.The

sample consisted of31 DNP students who received an MI training,including a

didactic lecture,role‐playing exercise,and standardized patient simulation.

Findings: Findings indicated a significantincrease in students’knowledge and

confidence regarding MI at both posttests compared with baseline.

Practice implications: Findings suggested that MI training with standardized patient

simulation demonstrated preliminary promising effects on DNP students’knowledge

and confidence in MI techniques to manage prescription opioid abuse among older

adults. This study showed the potential to enhance the care of older adults who abuse

opioids to address this problem in practice.

K E Y W O R D S

chronic pain,motivationalinterviewing,older adults,prescription opioid misuse,standardized

patient simulation

1 | INTRODUCTION

Prescription opioids are a common strategy for managing chronic

pain in older adults.1 The use of these medications in the older adult

population has increased nine‐fold between the years of1995 to

2010.2 It has been found that 92% of older adults that were

prescribed opioids had been on them for a period of5 years or

more.3 Opioids are being used more frequently and for longer

periods of time to treat patients experiencing chronic pain.4 As the

use of opioids has increased, there has been a corresponding increase

in their misuse or abuse.5 In 2012, 2.9 million older adults in America

reported nonmedical use of their prescription drugs.6 In addition, the

rates of older adults being admitted into facilities for treatment of

prescription drug abuse has increased from 0.7% to 3.5% between

the years of 1992 to 2005.3 As the population of older adults

increases,especially with the aging of baby boomers,it is expected

that providers will be faced with increased incidences of chronic pain.

Inevitably,this will lead to increased prescription opioid use by the

older adult population, thereby increasing the potential for misuse or

abuse.7

The question raised by this growing problem is how to properly

intervene in older adults with chronic pain who misuse or abuse their

prescription opioids?Currently, there is limited information on

effective interventionsfor substance use disorder(SUD) among

older adults.However,there are severalavailable evidence‐based

practice approaches for the treatment ofSUD within the general

population.One approach is the use of motivationalinterviewing

(MI). MI is a patient‐centered,semi‐directive cognitive behavioral

method that focuses on enhancing intrinsic motivation,and auton-

omy to change behavior.8 Clinicians help patients identify problem

behaviors,resolve ambivalence,determine and enhance motivation,

and aid in problem‐solving and goalsetting.9 MI has been demon-

strated to be effective in patient health behavior outcomes, including

substance abuse.8,9 There are studies that support the efficacy of MI

on behavior change among older adults to address a variety of health

care issues including physical activity, general health, smoking

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

cessation,diet, weight loss,and cardiovascular risk factors.10 One

study on hazardous drinking among the older adult population found

that MI had a significant impact on decreasing the number of drinks

per day, the total number of drinks overall, as well as increasing days

of abstinence when compared with standard care.11

2 | CURRENT ISSUE ON BEHAVIORAL

INTERVENTION TRAINING AMONG

HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS

Without adequate mentaland behavioralhealth services to treat

older adults who are misusing or abusing their prescription opioids,

the burden falls to other health care providers,such as primary care

providers.Currently,MI has not been adequately incorporated into

the educational curriculum of health care providers, preventing them

from gaining enough knowledge and skill to perform this intervention

when they begin practicing.It has also been noted that older adults

are less likely to seek help for their substance use,12 partially due to

perceived stigma.Utilizing MI techniques within the primary care

setting might increase older adults’motivation to seek treatments.

As a counseling approach that can be utilized by any health care

providers,including primary care,MI could be a feasible solution to

overcoming barriers for providing intervention to older adults with a

SUD.The utilization of MI would allow any health care provider who

is a part of the patient’s care, the ability to promote behavior change.

In addition,MI has been found to be useful in situations where there

is limited contact with patients and can be performed in as little as

one to two sessions.13 MI also has the potentialto be used as a

preventative measure for prescription opioid misuse or abuse for

individuals with chronic pain issues.A pilot study found that the use

of MI decreased the risk of prescription opioid abuse in older adults

with chronic pain,as well as decreased the risk of alcohol abuse for

those that drank.14

2.1 | Motivational interviewing training

With the lack of educational preparation on behavioral interventions

and the inadequate numbers of trained mentalhealth providers,an

argument can be made that it is important for future health care

providers to be educated on the use ofMI. With proper training,

health care providers can be more competent in addressing issues

among older adults with chronic pain who are misusing or abusing

their prescription opioids. Multiple studies have focused on

incorporating MI education into the curricula ofdifferent health

care disciplines.The most frequently studied discipline is medical

education.15-17 These studies indicated that a formalized MI

education helped to increase medical student’s behavioral counseling

skills and supported that MI education should be a part of an

educationalcurriculum for future providers in an effort to better

prepare them to address behavior modification in their future patient

population.Yet, such integration and evaluation of MI education in

nursing education is lacking.

2.2 | Standardized patient simulations

With the understanding that MI education is important,the question

arises as to how to educate future health care providers in this

technique.A number of studies on MI education with medical

students utilized standardizedpatients (SP) as an educational

intervention and assessmenttool.15-17 Research supports the use

of SP as an educational strategy that has been found to be effective

in improving student’s knowledge,psychomotor skills,and commu-

nication skills when used in the fields of medical and nursing

education.18 A meta‐analysis on the efficacy of SP in nursing

education found that SP had a significant positive effect on students’

cognitive (knowledge,critical thinking, communication,problem‐

solving),affective (learning motivation,self‐efficacy,learning satis-

faction), and psychomotor (clinical competencies) learning domains.19

SP used in mental health education provides an increased benefit of

allowing students to be able to assess nonverbalcues that patients

exhibit such as body and facial expression. Nonverbal communication

can provide information that may be useful in evaluating and

developing a plan of care for patients.20

With approximately two‐thirdsof Americansbeing seen by

advanced practice nurses (APNs)for their health care needs,the

potential for APNs to make a significant contribution toward

addressing the needs of older adults who are misusing or abusing

their prescription opioids is clearly evident. This supports the

argumentfor the need to educate APNs on MI so they will be

equipped with the appropriate skills and knowledge needed to utilize

this behavioral intervention.However,there is a lack of research on

MI education for APN students.This study aimed to evaluate an MI

educationalintervention through the use of didactic and SP

simulations on the doctorate of nursing practice (DNP) students to

address prescription opioid abuse in the older adult population living

with chronic pain.

3 | METHOD

3.1 | Design and sample

This study utilized a one‐group pretest‐posttest design with a

convenience sampling.The outcome variables included confi-

dence,knowledge,and skills regarding the use of MI.The sample

consisted of 31 students who were enrolled in the baccalaureate

of nursing (BSN) to the doctorate of nursing practice program

(DNP) of a University. The MI educational intervention was

integrated into the advanced health assessment course.The MI

education included a didactic lecture,a role‐playing exercise,and

SP simulation.All students enrolled in the course were required

to complete this activity.The students were given a choice as to

whether or not they wanted to complete the pre‐ and posttests.

Completion of the pre‐ and posttests were indicative of informed

consent that the data could be used for research purposes.An

explanation of how this data would be used was provided to the

students before the implementation ofthe study. The didactic

682 | CHANG ET AL.

study on hazardous drinking among the older adult population found

that MI had a significant impact on decreasing the number of drinks

per day, the total number of drinks overall, as well as increasing days

of abstinence when compared with standard care.11

2 | CURRENT ISSUE ON BEHAVIORAL

INTERVENTION TRAINING AMONG

HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS

Without adequate mentaland behavioralhealth services to treat

older adults who are misusing or abusing their prescription opioids,

the burden falls to other health care providers,such as primary care

providers.Currently,MI has not been adequately incorporated into

the educational curriculum of health care providers, preventing them

from gaining enough knowledge and skill to perform this intervention

when they begin practicing.It has also been noted that older adults

are less likely to seek help for their substance use,12 partially due to

perceived stigma.Utilizing MI techniques within the primary care

setting might increase older adults’motivation to seek treatments.

As a counseling approach that can be utilized by any health care

providers,including primary care,MI could be a feasible solution to

overcoming barriers for providing intervention to older adults with a

SUD.The utilization of MI would allow any health care provider who

is a part of the patient’s care, the ability to promote behavior change.

In addition,MI has been found to be useful in situations where there

is limited contact with patients and can be performed in as little as

one to two sessions.13 MI also has the potentialto be used as a

preventative measure for prescription opioid misuse or abuse for

individuals with chronic pain issues.A pilot study found that the use

of MI decreased the risk of prescription opioid abuse in older adults

with chronic pain,as well as decreased the risk of alcohol abuse for

those that drank.14

2.1 | Motivational interviewing training

With the lack of educational preparation on behavioral interventions

and the inadequate numbers of trained mentalhealth providers,an

argument can be made that it is important for future health care

providers to be educated on the use ofMI. With proper training,

health care providers can be more competent in addressing issues

among older adults with chronic pain who are misusing or abusing

their prescription opioids. Multiple studies have focused on

incorporating MI education into the curricula ofdifferent health

care disciplines.The most frequently studied discipline is medical

education.15-17 These studies indicated that a formalized MI

education helped to increase medical student’s behavioral counseling

skills and supported that MI education should be a part of an

educationalcurriculum for future providers in an effort to better

prepare them to address behavior modification in their future patient

population.Yet, such integration and evaluation of MI education in

nursing education is lacking.

2.2 | Standardized patient simulations

With the understanding that MI education is important,the question

arises as to how to educate future health care providers in this

technique.A number of studies on MI education with medical

students utilized standardizedpatients (SP) as an educational

intervention and assessmenttool.15-17 Research supports the use

of SP as an educational strategy that has been found to be effective

in improving student’s knowledge,psychomotor skills,and commu-

nication skills when used in the fields of medical and nursing

education.18 A meta‐analysis on the efficacy of SP in nursing

education found that SP had a significant positive effect on students’

cognitive (knowledge,critical thinking, communication,problem‐

solving),affective (learning motivation,self‐efficacy,learning satis-

faction), and psychomotor (clinical competencies) learning domains.19

SP used in mental health education provides an increased benefit of

allowing students to be able to assess nonverbalcues that patients

exhibit such as body and facial expression. Nonverbal communication

can provide information that may be useful in evaluating and

developing a plan of care for patients.20

With approximately two‐thirdsof Americansbeing seen by

advanced practice nurses (APNs)for their health care needs,the

potential for APNs to make a significant contribution toward

addressing the needs of older adults who are misusing or abusing

their prescription opioids is clearly evident. This supports the

argumentfor the need to educate APNs on MI so they will be

equipped with the appropriate skills and knowledge needed to utilize

this behavioral intervention.However,there is a lack of research on

MI education for APN students.This study aimed to evaluate an MI

educationalintervention through the use of didactic and SP

simulations on the doctorate of nursing practice (DNP) students to

address prescription opioid abuse in the older adult population living

with chronic pain.

3 | METHOD

3.1 | Design and sample

This study utilized a one‐group pretest‐posttest design with a

convenience sampling.The outcome variables included confi-

dence,knowledge,and skills regarding the use of MI.The sample

consisted of 31 students who were enrolled in the baccalaureate

of nursing (BSN) to the doctorate of nursing practice program

(DNP) of a University. The MI educational intervention was

integrated into the advanced health assessment course.The MI

education included a didactic lecture,a role‐playing exercise,and

SP simulation.All students enrolled in the course were required

to complete this activity.The students were given a choice as to

whether or not they wanted to complete the pre‐ and posttests.

Completion of the pre‐ and posttests were indicative of informed

consent that the data could be used for research purposes.An

explanation of how this data would be used was provided to the

students before the implementation ofthe study. The didactic

682 | CHANG ET AL.

lecture and the role‐playing exercise occurred in a classroom

setting and the SP simulation took place within the simulation

center of the University.Approval for this study was obtained by

the University’s InstitutionalReview Board.

3.2 | Didactic lecture and role play

The MI lecture and role‐playing scenario were developed by two

experts who have experience in utilizing MI in research,education,

and clinicalpractice.Materials used for the didactic lecture were

taken in part from the Motivational Interviewing Network of

Trainers,an organization designed to promote research and training

of MI. Other materials were obtained from a thorough review of the

current literature on MI training. The didactic lecture includes

content on MI principles,spirit, core skills,techniques,and clinical

applications,as well as barriers to helping patientschange.The

lecture used the example of an older adult who took more

prescription opioids than prescribed.A role‐playing scenario utilizing

that example was demonstrated to students by the research team.

The students were then given similar scenarios and performed role‐

playing by taking turns,acting as both the patient and practitioner.

The research team and course instructorwere available to help

students with MI skills and techniques,provide immediate feedback,

and answer any questions.

3.3 | Simulation preparation and implementation

3.3.1 | Preparation

The SP scenario was developed by an expert panelof psychiatric‐

mental health professionals,family nursing practitioners,MI experts,

addiction researchers, experienced educators, and simulation faculty.

The SP simulation involved an older adult patient who was asking for

an early refillof prescription opioid medication that he took for his

chronic pain.The patient had been misusing his opioids by taking

more than prescribed to help with pain and other symptoms.The

patient in the scenario was a recent widower who was becoming

increasingly depressed and was also drinking in excess.He had risk

factors of socialisolation,limited mobility,and unmanaged pain.An

MI lecture was provided to 11 SP who were experienced professional

actors in simulation.A training section was held to promote SP’s

understanding of MIeducation,as well as the simulation scenario.

SP’s training involved a 2‐hour training session that covered topics

including project overview; read‐through and clarification of scenar-

io; role‐playing;trouble‐shooting;appropriate attire and demeanor

(eg body language,disposition,etc) during simulation;a tour of

simulation rooms;and what type of education students were given.

The SPs were expected to study the training materialfor 4 hours

after the training session before the simulation. The SPs also received

a lecture on the basic concepts of MI.A brief meeting with SPs was

held directly before the simulation for a brief review of the training

materials and to answer any questions.

Students were given a briefreview of the simulation process

before the simulation took place.Studentswere encouraged to

review training materials as described in the didactic and role‐play

section.Students were given a PowerPoint lecture on the simulation

process including the SP,space,time duration,and procedure.A

discussion was also held with students to help them understand the

simulation process,expectations,and to address any questions or

concerns.

3.3.2 | Implementation

Students were given 10 minutesto review a door chart that

contained pertinentpatient information thatwould simulate the

type of information a “real‐life” provider may have before a patient

encounter. The door chart contained instructions for students to help

guide them through the simulation.The instructions were very

detailed,as the participants in the study were the first year DNP

students who had not yet taken their clinicalpracticum course,nor

had any prior experience with SP simulation.After the 10‐minute

review, students were prompted to enter the patient room and begin

the encounter.The encounter was limited to 30 minutes.After the

students finished their encounter,they were asked to wait outside

the patient’s door.Then as a group,they were taken to a computer

lab to complete their simulation evaluation.After all, students

completed their evaluation,they were taken into a conference room

for debriefing.Debriefing was facilitated by the research staff and

included reflection and discussion regarding the simulation scenario,

the educationalintervention,and the simulation process.Students

were asked questions such as: what could be done better with regard

to the simulation experience? What aspects of MIwere you most

successfulat demonstratingor would like to strengthen? And

whether or not a participation in the simulation experience helped

better prepare you for implementing MI into your clinicalpractice.

The debriefing session provided an opportunity forstudentsto

critique and reflect on their performance and facilitate learning by

recognizing the knowledge and skills they demonstrated vs those

they did not.This allowed for students to transform and assimilate

new knowledge by utilizing reflective observation to create abstract

conceptualization.

3.4 | Measures

3.4.1 | Motivational interviewing knowledge and

attitude test

Motivationalinterviewing knowledge and attitude test (MIKAT) is a

measurement tool that assesses MI knowledge and beliefs consistent

with the spirit of MI. The tool is useful for measuring changes in

attitudes and knowledge regarding MIbefore and after an educa-

tionalintervention.The MIKAT is a quiz consisting of 19 questions:

10 true‐false questions about addiction myths; four questions about

MI‐consistent attitudes and assumptions;and five questions about

counseling behaviors consistentwith an MI approach.Scoring is

based upon calculating the number of correct answers given by the

subject then dividing by 19 (the totalnumber ofcorrect answers

possible). Scoring is divided into subcomponentsthat include

CHANG ET AL. | 683

setting and the SP simulation took place within the simulation

center of the University.Approval for this study was obtained by

the University’s InstitutionalReview Board.

3.2 | Didactic lecture and role play

The MI lecture and role‐playing scenario were developed by two

experts who have experience in utilizing MI in research,education,

and clinicalpractice.Materials used for the didactic lecture were

taken in part from the Motivational Interviewing Network of

Trainers,an organization designed to promote research and training

of MI. Other materials were obtained from a thorough review of the

current literature on MI training. The didactic lecture includes

content on MI principles,spirit, core skills,techniques,and clinical

applications,as well as barriers to helping patientschange.The

lecture used the example of an older adult who took more

prescription opioids than prescribed.A role‐playing scenario utilizing

that example was demonstrated to students by the research team.

The students were then given similar scenarios and performed role‐

playing by taking turns,acting as both the patient and practitioner.

The research team and course instructorwere available to help

students with MI skills and techniques,provide immediate feedback,

and answer any questions.

3.3 | Simulation preparation and implementation

3.3.1 | Preparation

The SP scenario was developed by an expert panelof psychiatric‐

mental health professionals,family nursing practitioners,MI experts,

addiction researchers, experienced educators, and simulation faculty.

The SP simulation involved an older adult patient who was asking for

an early refillof prescription opioid medication that he took for his

chronic pain.The patient had been misusing his opioids by taking

more than prescribed to help with pain and other symptoms.The

patient in the scenario was a recent widower who was becoming

increasingly depressed and was also drinking in excess.He had risk

factors of socialisolation,limited mobility,and unmanaged pain.An

MI lecture was provided to 11 SP who were experienced professional

actors in simulation.A training section was held to promote SP’s

understanding of MIeducation,as well as the simulation scenario.

SP’s training involved a 2‐hour training session that covered topics

including project overview; read‐through and clarification of scenar-

io; role‐playing;trouble‐shooting;appropriate attire and demeanor

(eg body language,disposition,etc) during simulation;a tour of

simulation rooms;and what type of education students were given.

The SPs were expected to study the training materialfor 4 hours

after the training session before the simulation. The SPs also received

a lecture on the basic concepts of MI.A brief meeting with SPs was

held directly before the simulation for a brief review of the training

materials and to answer any questions.

Students were given a briefreview of the simulation process

before the simulation took place.Studentswere encouraged to

review training materials as described in the didactic and role‐play

section.Students were given a PowerPoint lecture on the simulation

process including the SP,space,time duration,and procedure.A

discussion was also held with students to help them understand the

simulation process,expectations,and to address any questions or

concerns.

3.3.2 | Implementation

Students were given 10 minutesto review a door chart that

contained pertinentpatient information thatwould simulate the

type of information a “real‐life” provider may have before a patient

encounter. The door chart contained instructions for students to help

guide them through the simulation.The instructions were very

detailed,as the participants in the study were the first year DNP

students who had not yet taken their clinicalpracticum course,nor

had any prior experience with SP simulation.After the 10‐minute

review, students were prompted to enter the patient room and begin

the encounter.The encounter was limited to 30 minutes.After the

students finished their encounter,they were asked to wait outside

the patient’s door.Then as a group,they were taken to a computer

lab to complete their simulation evaluation.After all, students

completed their evaluation,they were taken into a conference room

for debriefing.Debriefing was facilitated by the research staff and

included reflection and discussion regarding the simulation scenario,

the educationalintervention,and the simulation process.Students

were asked questions such as: what could be done better with regard

to the simulation experience? What aspects of MIwere you most

successfulat demonstratingor would like to strengthen? And

whether or not a participation in the simulation experience helped

better prepare you for implementing MI into your clinicalpractice.

The debriefing session provided an opportunity forstudentsto

critique and reflect on their performance and facilitate learning by

recognizing the knowledge and skills they demonstrated vs those

they did not.This allowed for students to transform and assimilate

new knowledge by utilizing reflective observation to create abstract

conceptualization.

3.4 | Measures

3.4.1 | Motivational interviewing knowledge and

attitude test

Motivationalinterviewing knowledge and attitude test (MIKAT) is a

measurement tool that assesses MI knowledge and beliefs consistent

with the spirit of MI. The tool is useful for measuring changes in

attitudes and knowledge regarding MIbefore and after an educa-

tionalintervention.The MIKAT is a quiz consisting of 19 questions:

10 true‐false questions about addiction myths; four questions about

MI‐consistent attitudes and assumptions;and five questions about

counseling behaviors consistentwith an MI approach.Scoring is

based upon calculating the number of correct answers given by the

subject then dividing by 19 (the totalnumber ofcorrect answers

possible). Scoring is divided into subcomponentsthat include

CHANG ET AL. | 683

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

attitudes consistent with MI, SA myths identified, behaviors

consistent with MI (prescribed behaviors),and behaviors not

consistent with MI (proscribed behaviors).21 Internalconsistency of

the toolhas been documented with a Cronbach’s α of 0.84.22

3.4.2 | Motivational interviewing confidence scale

Because there is no established toolmeasuring confidence for MI,the

research team developed this tool to assess the student’s confidence in

understanding and performing MI.The development ofthis tool was

through a review of literature by a group of clinicians and educators who

have expertise in motivational interviewing.The tool was also reviewed

by a panel of researchers and clinicians for content validity. A total of 10

questions were developed to measure how confident students are in

their ability to use MI techniques including express empathy; elicit/evoke

change talk; engage in reflective listening; assess the stage of change; use

the readiness to change ruler,and apply MI in clinical practice.The tool

utilizesa five‐pointLikert scale thatrangesfrom one, being “very

confident”,to five,being “very not confident”.

3.4.3 | Behavior change counseling index

Behavior change counseling index (BECCI) is a tool assessing skills in MI

counseling and has been widely utilized in previous studies.BECCI

includes 11 items that measure the counselor’s MI skills using a five‐point

scale with zero beings “did notdemonstrate atall” and four being

“demonstrated with a greatextent.”The tool aims to focus on the

counselor’s behavior and attitude rather than patient response. While the

internalconsistency is low,this toolhas demonstrated high inter‐rater

reliability with a moderate levelof reliability across time,as wellas a

moderatesensitivityto observe the change in the interviewer’s

performance.23 Score is reported as a mean score (totalscore for all

11 items/11).The tool also assesses how often the counselor spoke,

whether it is “more than half the time”, “about half the time”, or “less than

half the time.” The MI counseling is collaborative and the patient is an

active and engaged participant.The counselor uses MI skills to explore

the patient’s feelings about behavior changes and encourage them to

make their own decisions about change by verbally expressing their

feelings and attitudes. Ideally, the counselor should be speaking less than

50% of the time.

3.5 | Demographic survey

The data collected included:age; sex; race; enrollmentstatus;

specialty enrolled in;employment status;years of working experi-

ence;type of nursing experience; current employment setting; work

experience with substance abuse;graduate‐levelcourse content on

substance abuse;and previous education on MI.

3.6 | Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the StatisticalPackage for the

SocialSciences (SPSS)software,version 24 (SPSS Inc,Chicago,IL).

Descriptive statistics including mean,range,standard deviation,and

percentage were used to describe the demographic data,as wellas

outcomes regarding MI skills obtained from the BECCI.A one way

repeated analysis of variance was utilized to examine the effect of

the MI education outcome variables,including MI confidence,

knowledge,and attitudes across three‐time points.

4 | RESULTS

All 31 students completed the preintervention and poststandardized

patient assessments.Twenty‐eightparticipantswere female and

three were male.Ages ranged from 21 to 42,with a mean age of 27.

Twenty‐five participants reported full‐time student status while six

reported a part‐time status.Amongst participants,45.2% of them

were in the family nurse practitioner program,19.4% in the adult

nurse practitionerprogram,and 35.5% in the psychiatric nurse

practitioner program. Most participants reported being used full‐time

(54.8%),41.9% reported being used part‐time,and 3.2% reported

being unemployed.Years of nursing experience ranged from 1 to

17 years, with the majority falling in the 1 year of nursing experience

(35.5%),and the second highest being 2 years of experience (22.6%).

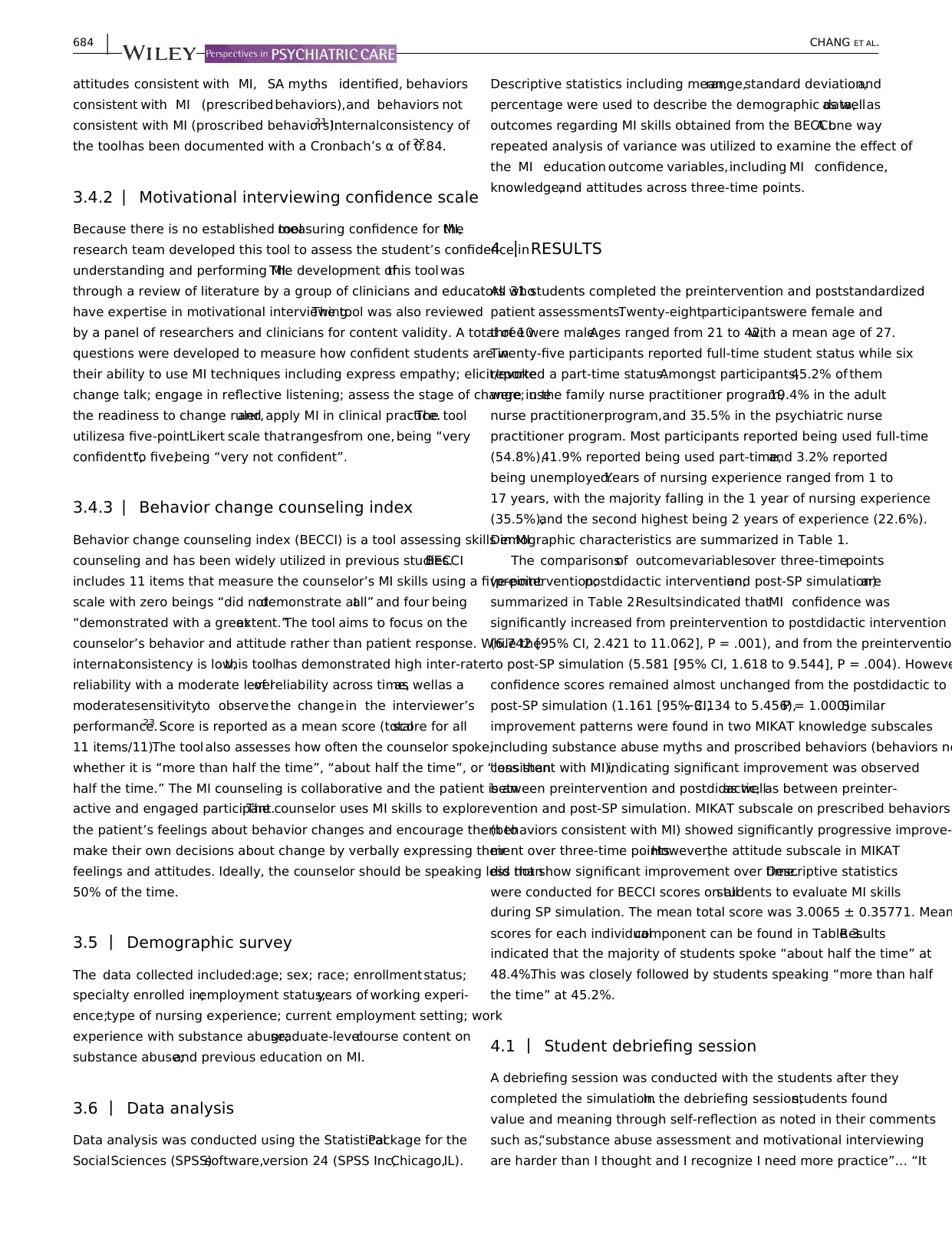

Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

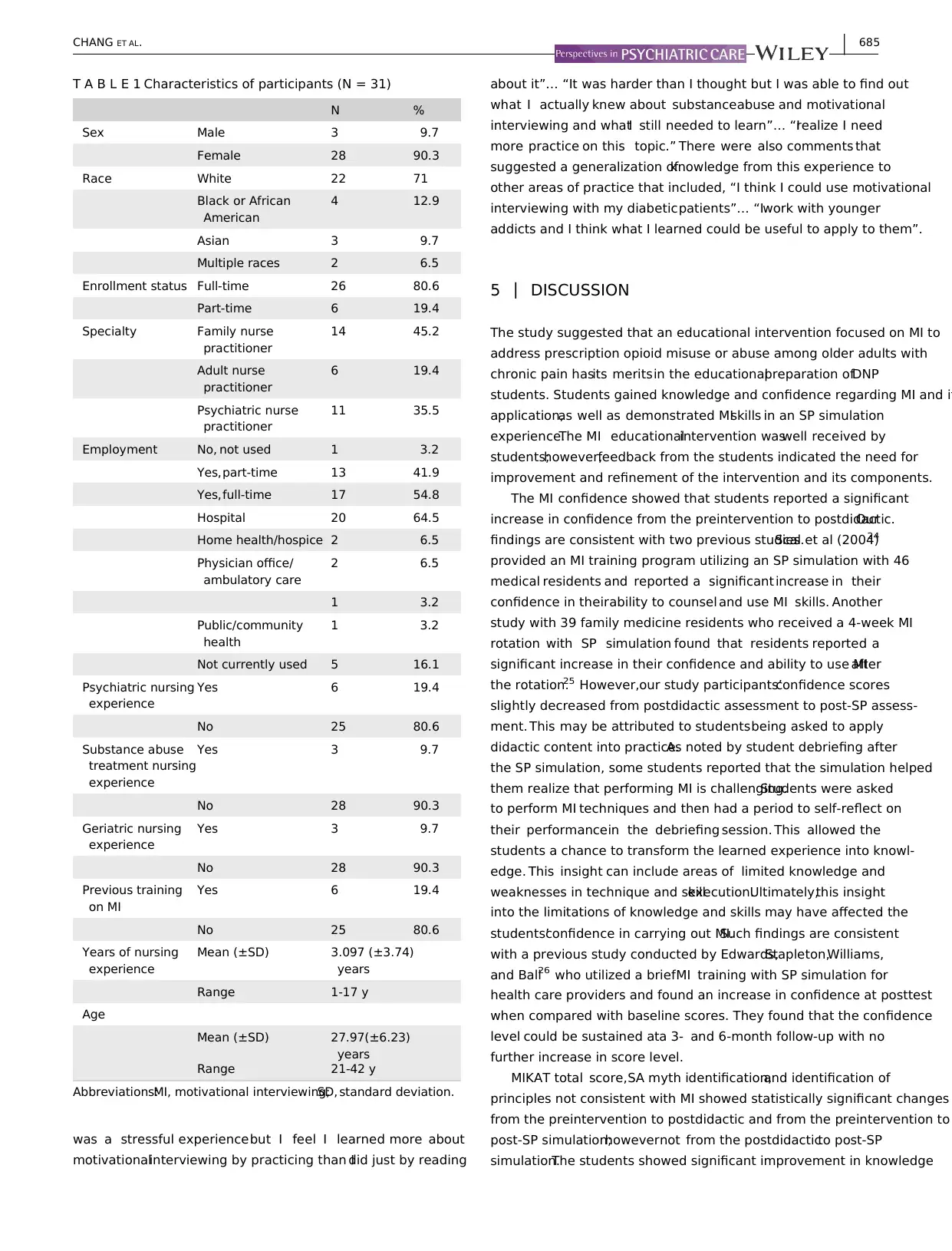

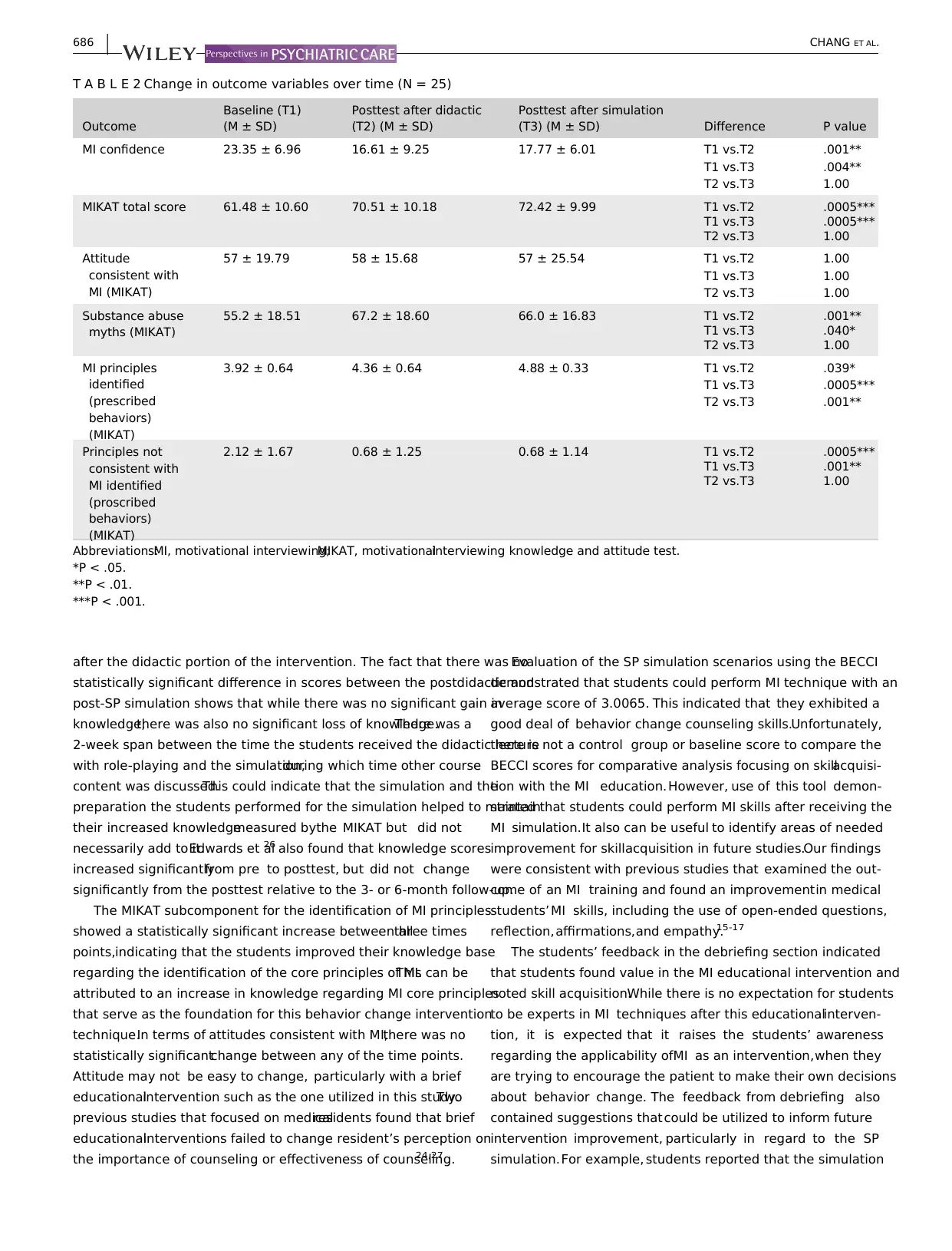

The comparisonsof outcomevariablesover three‐timepoints

(preintervention;postdidactic intervention;and post‐SP simulation)are

summarized in Table 2.Resultsindicated thatMI confidence was

significantly increased from preintervention to postdidactic intervention

(6.742 [95% CI, 2.421 to 11.062], P = .001), and from the preinterventio

to post‐SP simulation (5.581 [95% CI, 1.618 to 9.544], P = .004). Howeve

confidence scores remained almost unchanged from the postdidactic to

post‐SP simulation (1.161 [95% CI,−3.134 to 5.456),P = 1.000).Similar

improvement patterns were found in two MIKAT knowledge subscales

including substance abuse myths and proscribed behaviors (behaviors no

consistent with MI),indicating significant improvement was observed

between preintervention and postdidactic,as wellas between preinter-

vention and post‐SP simulation. MIKAT subscale on prescribed behaviors

(behaviors consistent with MI) showed significantly progressive improve-

ment over three‐time points.However,the attitude subscale in MIKAT

did not show significant improvement over time.Descriptive statistics

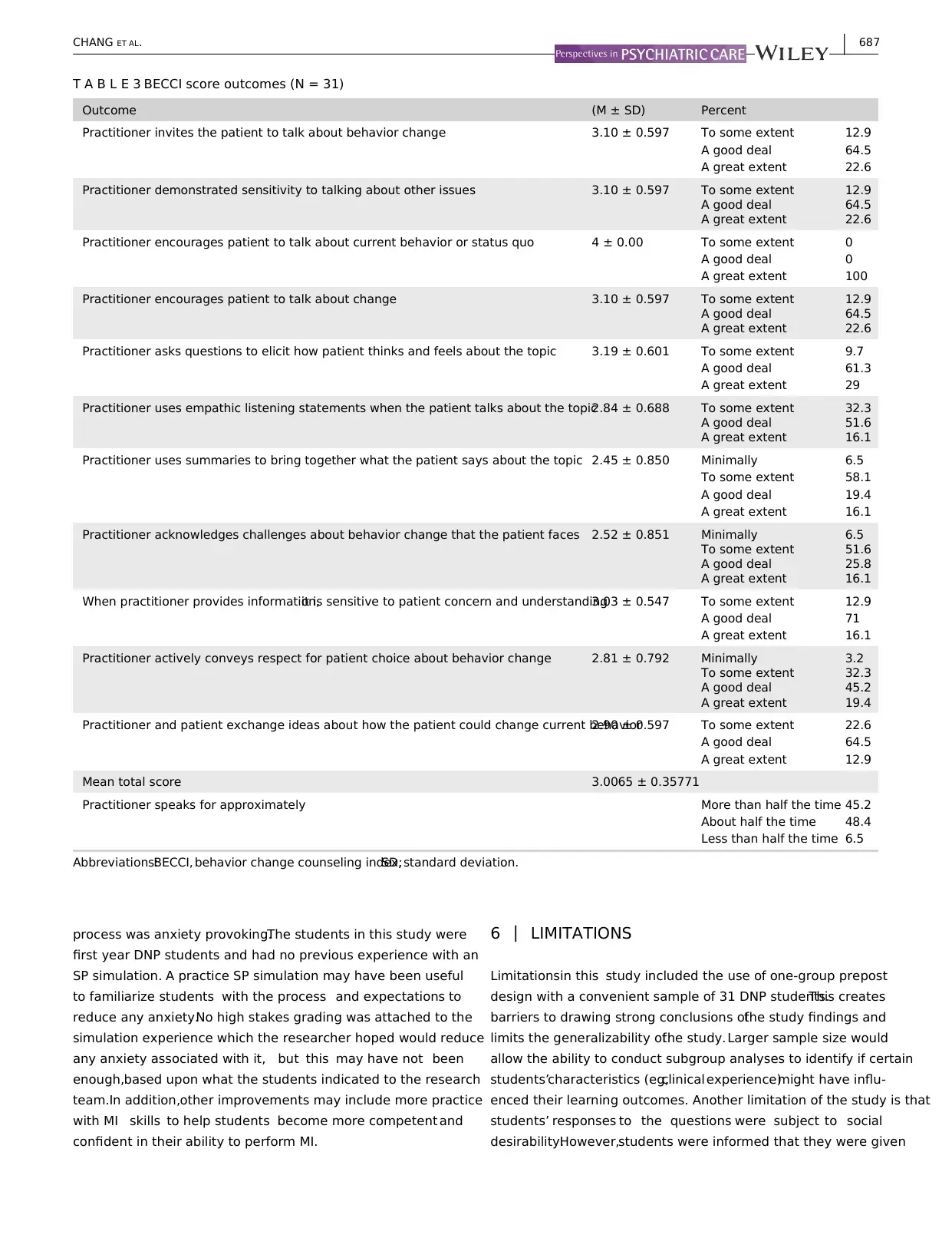

were conducted for BECCI scores on allstudents to evaluate MI skills

during SP simulation. The mean total score was 3.0065 ± 0.35771. Mean

scores for each individualcomponent can be found in Table 3.Results

indicated that the majority of students spoke “about half the time” at

48.4%.This was closely followed by students speaking “more than half

the time” at 45.2%.

4.1 | Student debriefing session

A debriefing session was conducted with the students after they

completed the simulation.In the debriefing session,students found

value and meaning through self‐reflection as noted in their comments

such as,“substance abuse assessment and motivational interviewing

are harder than I thought and I recognize I need more practice”… “It

684 | CHANG ET AL.

consistent with MI (prescribed behaviors),and behaviors not

consistent with MI (proscribed behaviors).21 Internalconsistency of

the toolhas been documented with a Cronbach’s α of 0.84.22

3.4.2 | Motivational interviewing confidence scale

Because there is no established toolmeasuring confidence for MI,the

research team developed this tool to assess the student’s confidence in

understanding and performing MI.The development ofthis tool was

through a review of literature by a group of clinicians and educators who

have expertise in motivational interviewing.The tool was also reviewed

by a panel of researchers and clinicians for content validity. A total of 10

questions were developed to measure how confident students are in

their ability to use MI techniques including express empathy; elicit/evoke

change talk; engage in reflective listening; assess the stage of change; use

the readiness to change ruler,and apply MI in clinical practice.The tool

utilizesa five‐pointLikert scale thatrangesfrom one, being “very

confident”,to five,being “very not confident”.

3.4.3 | Behavior change counseling index

Behavior change counseling index (BECCI) is a tool assessing skills in MI

counseling and has been widely utilized in previous studies.BECCI

includes 11 items that measure the counselor’s MI skills using a five‐point

scale with zero beings “did notdemonstrate atall” and four being

“demonstrated with a greatextent.”The tool aims to focus on the

counselor’s behavior and attitude rather than patient response. While the

internalconsistency is low,this toolhas demonstrated high inter‐rater

reliability with a moderate levelof reliability across time,as wellas a

moderatesensitivityto observe the change in the interviewer’s

performance.23 Score is reported as a mean score (totalscore for all

11 items/11).The tool also assesses how often the counselor spoke,

whether it is “more than half the time”, “about half the time”, or “less than

half the time.” The MI counseling is collaborative and the patient is an

active and engaged participant.The counselor uses MI skills to explore

the patient’s feelings about behavior changes and encourage them to

make their own decisions about change by verbally expressing their

feelings and attitudes. Ideally, the counselor should be speaking less than

50% of the time.

3.5 | Demographic survey

The data collected included:age; sex; race; enrollmentstatus;

specialty enrolled in;employment status;years of working experi-

ence;type of nursing experience; current employment setting; work

experience with substance abuse;graduate‐levelcourse content on

substance abuse;and previous education on MI.

3.6 | Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the StatisticalPackage for the

SocialSciences (SPSS)software,version 24 (SPSS Inc,Chicago,IL).

Descriptive statistics including mean,range,standard deviation,and

percentage were used to describe the demographic data,as wellas

outcomes regarding MI skills obtained from the BECCI.A one way

repeated analysis of variance was utilized to examine the effect of

the MI education outcome variables,including MI confidence,

knowledge,and attitudes across three‐time points.

4 | RESULTS

All 31 students completed the preintervention and poststandardized

patient assessments.Twenty‐eightparticipantswere female and

three were male.Ages ranged from 21 to 42,with a mean age of 27.

Twenty‐five participants reported full‐time student status while six

reported a part‐time status.Amongst participants,45.2% of them

were in the family nurse practitioner program,19.4% in the adult

nurse practitionerprogram,and 35.5% in the psychiatric nurse

practitioner program. Most participants reported being used full‐time

(54.8%),41.9% reported being used part‐time,and 3.2% reported

being unemployed.Years of nursing experience ranged from 1 to

17 years, with the majority falling in the 1 year of nursing experience

(35.5%),and the second highest being 2 years of experience (22.6%).

Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

The comparisonsof outcomevariablesover three‐timepoints

(preintervention;postdidactic intervention;and post‐SP simulation)are

summarized in Table 2.Resultsindicated thatMI confidence was

significantly increased from preintervention to postdidactic intervention

(6.742 [95% CI, 2.421 to 11.062], P = .001), and from the preinterventio

to post‐SP simulation (5.581 [95% CI, 1.618 to 9.544], P = .004). Howeve

confidence scores remained almost unchanged from the postdidactic to

post‐SP simulation (1.161 [95% CI,−3.134 to 5.456),P = 1.000).Similar

improvement patterns were found in two MIKAT knowledge subscales

including substance abuse myths and proscribed behaviors (behaviors no

consistent with MI),indicating significant improvement was observed

between preintervention and postdidactic,as wellas between preinter-

vention and post‐SP simulation. MIKAT subscale on prescribed behaviors

(behaviors consistent with MI) showed significantly progressive improve-

ment over three‐time points.However,the attitude subscale in MIKAT

did not show significant improvement over time.Descriptive statistics

were conducted for BECCI scores on allstudents to evaluate MI skills

during SP simulation. The mean total score was 3.0065 ± 0.35771. Mean

scores for each individualcomponent can be found in Table 3.Results

indicated that the majority of students spoke “about half the time” at

48.4%.This was closely followed by students speaking “more than half

the time” at 45.2%.

4.1 | Student debriefing session

A debriefing session was conducted with the students after they

completed the simulation.In the debriefing session,students found

value and meaning through self‐reflection as noted in their comments

such as,“substance abuse assessment and motivational interviewing

are harder than I thought and I recognize I need more practice”… “It

684 | CHANG ET AL.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

was a stressful experiencebut I feel I learned more about

motivationalinterviewing by practicing than Idid just by reading

about it”… “It was harder than I thought but I was able to find out

what I actually knew about substanceabuse and motivational

interviewing and whatI still needed to learn”… “Irealize I need

more practice on this topic.” There were also comments that

suggested a generalization ofknowledge from this experience to

other areas of practice that included, “I think I could use motivational

interviewing with my diabeticpatients”… “Iwork with younger

addicts and I think what I learned could be useful to apply to them”.

5 | DISCUSSION

The study suggested that an educational intervention focused on MI to

address prescription opioid misuse or abuse among older adults with

chronic pain hasits meritsin the educationalpreparation ofDNP

students. Students gained knowledge and confidence regarding MI and it

application,as well as demonstrated MIskills in an SP simulation

experience.The MI educationalintervention waswell received by

students;however,feedback from the students indicated the need for

improvement and refinement of the intervention and its components.

The MI confidence showed that students reported a significant

increase in confidence from the preintervention to postdidactic.Our

findings are consistent with two previous studies.Scal et al (2004)24

provided an MI training program utilizing an SP simulation with 46

medical residents and reported a significant increase in their

confidence in theirability to counsel and use MI skills. Another

study with 39 family medicine residents who received a 4‐week MI

rotation with SP simulation found that residents reported a

significant increase in their confidence and ability to use MIafter

the rotation.25 However,our study participants’confidence scores

slightly decreased from postdidactic assessment to post‐SP assess-

ment. This may be attributed to studentsbeing asked to apply

didactic content into practice.As noted by student debriefing after

the SP simulation, some students reported that the simulation helped

them realize that performing MI is challenging.Students were asked

to perform MI techniques and then had a period to self‐reflect on

their performancein the debriefing session. This allowed the

students a chance to transform the learned experience into knowl-

edge. This insight can include areas of limited knowledge and

weaknesses in technique and skillexecution.Ultimately,this insight

into the limitations of knowledge and skills may have affected the

students’confidence in carrying out MI.Such findings are consistent

with a previous study conducted by Edwards,Stapleton,Williams,

and Ball26 who utilized a briefMI training with SP simulation for

health care providers and found an increase in confidence at posttest

when compared with baseline scores. They found that the confidence

level could be sustained ata 3‐ and 6‐month follow‐up with no

further increase in score level.

MIKAT total score,SA myth identification,and identification of

principles not consistent with MI showed statistically significant changes

from the preintervention to postdidactic and from the preintervention to

post‐SP simulation;howevernot from the postdidacticto post‐SP

simulation.The students showed significant improvement in knowledge

T A B L E 1 Characteristics of participants (N = 31)

N %

Sex Male 3 9.7

Female 28 90.3

Race White 22 71

Black or African

American

4 12.9

Asian 3 9.7

Multiple races 2 6.5

Enrollment status Full‐time 26 80.6

Part‐time 6 19.4

Specialty Family nurse

practitioner

14 45.2

Adult nurse

practitioner

6 19.4

Psychiatric nurse

practitioner

11 35.5

Employment No, not used 1 3.2

Yes,part‐time 13 41.9

Yes,full‐time 17 54.8

Hospital 20 64.5

Home health/hospice 2 6.5

Physician office/

ambulatory care

2 6.5

1 3.2

Public/community

health

1 3.2

Not currently used 5 16.1

Psychiatric nursing

experience

Yes 6 19.4

No 25 80.6

Substance abuse

treatment nursing

experience

Yes 3 9.7

No 28 90.3

Geriatric nursing

experience

Yes 3 9.7

No 28 90.3

Previous training

on MI

Yes 6 19.4

No 25 80.6

Years of nursing

experience

Mean (±SD) 3.097 (±3.74)

years

Range 1‐17 y

Age

Mean (±SD) 27.97(±6.23)

years

Range 21‐42 y

Abbreviations:MI, motivational interviewing;SD, standard deviation.

CHANG ET AL. | 685

motivationalinterviewing by practicing than Idid just by reading

about it”… “It was harder than I thought but I was able to find out

what I actually knew about substanceabuse and motivational

interviewing and whatI still needed to learn”… “Irealize I need

more practice on this topic.” There were also comments that

suggested a generalization ofknowledge from this experience to

other areas of practice that included, “I think I could use motivational

interviewing with my diabeticpatients”… “Iwork with younger

addicts and I think what I learned could be useful to apply to them”.

5 | DISCUSSION

The study suggested that an educational intervention focused on MI to

address prescription opioid misuse or abuse among older adults with

chronic pain hasits meritsin the educationalpreparation ofDNP

students. Students gained knowledge and confidence regarding MI and it

application,as well as demonstrated MIskills in an SP simulation

experience.The MI educationalintervention waswell received by

students;however,feedback from the students indicated the need for

improvement and refinement of the intervention and its components.

The MI confidence showed that students reported a significant

increase in confidence from the preintervention to postdidactic.Our

findings are consistent with two previous studies.Scal et al (2004)24

provided an MI training program utilizing an SP simulation with 46

medical residents and reported a significant increase in their

confidence in theirability to counsel and use MI skills. Another

study with 39 family medicine residents who received a 4‐week MI

rotation with SP simulation found that residents reported a

significant increase in their confidence and ability to use MIafter

the rotation.25 However,our study participants’confidence scores

slightly decreased from postdidactic assessment to post‐SP assess-

ment. This may be attributed to studentsbeing asked to apply

didactic content into practice.As noted by student debriefing after

the SP simulation, some students reported that the simulation helped

them realize that performing MI is challenging.Students were asked

to perform MI techniques and then had a period to self‐reflect on

their performancein the debriefing session. This allowed the

students a chance to transform the learned experience into knowl-

edge. This insight can include areas of limited knowledge and

weaknesses in technique and skillexecution.Ultimately,this insight

into the limitations of knowledge and skills may have affected the

students’confidence in carrying out MI.Such findings are consistent

with a previous study conducted by Edwards,Stapleton,Williams,

and Ball26 who utilized a briefMI training with SP simulation for

health care providers and found an increase in confidence at posttest

when compared with baseline scores. They found that the confidence

level could be sustained ata 3‐ and 6‐month follow‐up with no

further increase in score level.

MIKAT total score,SA myth identification,and identification of

principles not consistent with MI showed statistically significant changes

from the preintervention to postdidactic and from the preintervention to

post‐SP simulation;howevernot from the postdidacticto post‐SP

simulation.The students showed significant improvement in knowledge

T A B L E 1 Characteristics of participants (N = 31)

N %

Sex Male 3 9.7

Female 28 90.3

Race White 22 71

Black or African

American

4 12.9

Asian 3 9.7

Multiple races 2 6.5

Enrollment status Full‐time 26 80.6

Part‐time 6 19.4

Specialty Family nurse

practitioner

14 45.2

Adult nurse

practitioner

6 19.4

Psychiatric nurse

practitioner

11 35.5

Employment No, not used 1 3.2

Yes,part‐time 13 41.9

Yes,full‐time 17 54.8

Hospital 20 64.5

Home health/hospice 2 6.5

Physician office/

ambulatory care

2 6.5

1 3.2

Public/community

health

1 3.2

Not currently used 5 16.1

Psychiatric nursing

experience

Yes 6 19.4

No 25 80.6

Substance abuse

treatment nursing

experience

Yes 3 9.7

No 28 90.3

Geriatric nursing

experience

Yes 3 9.7

No 28 90.3

Previous training

on MI

Yes 6 19.4

No 25 80.6

Years of nursing

experience

Mean (±SD) 3.097 (±3.74)

years

Range 1‐17 y

Age

Mean (±SD) 27.97(±6.23)

years

Range 21‐42 y

Abbreviations:MI, motivational interviewing;SD, standard deviation.

CHANG ET AL. | 685

after the didactic portion of the intervention. The fact that there was no

statistically significant difference in scores between the postdidactic and

post‐SP simulation shows that while there was no significant gain in

knowledge,there was also no significant loss of knowledge.There was a

2‐week span between the time the students received the didactic lecture

with role‐playing and the simulation,during which time other course

content was discussed.This could indicate that the simulation and the

preparation the students performed for the simulation helped to maintain

their increased knowledgemeasured bythe MIKAT but did not

necessarily add to it.Edwards et al26 also found that knowledge scores

increased significantlyfrom pre to posttest, but did not change

significantly from the posttest relative to the 3‐ or 6‐month follow‐up.

The MIKAT subcomponent for the identification of MI principles

showed a statistically significant increase between allthree times

points,indicating that the students improved their knowledge base

regarding the identification of the core principles of MI.This can be

attributed to an increase in knowledge regarding MI core principles

that serve as the foundation for this behavior change intervention

technique.In terms of attitudes consistent with MI,there was no

statistically significantchange between any of the time points.

Attitude may not be easy to change, particularly with a brief

educationalintervention such as the one utilized in this study.Two

previous studies that focused on medicalresidents found that brief

educationalinterventions failed to change resident’s perception on

the importance of counseling or effectiveness of counseling.24,27

Evaluation of the SP simulation scenarios using the BECCI

demonstrated that students could perform MI technique with an

average score of 3.0065. This indicated that they exhibited a

good deal of behavior change counseling skills.Unfortunately,

there is not a control group or baseline score to compare the

BECCI scores for comparative analysis focusing on skillacquisi-

tion with the MI education. However, use of this tool demon-

strated that students could perform MI skills after receiving the

MI simulation.It also can be useful to identify areas of needed

improvement for skillacquisition in future studies.Our findings

were consistent with previous studies that examined the out-

come of an MI training and found an improvementin medical

students’ MI skills, including the use of open‐ended questions,

reflection,affirmations,and empathy.15-17

The students’ feedback in the debriefing section indicated

that students found value in the MI educational intervention and

noted skill acquisition.While there is no expectation for students

to be experts in MI techniques after this educationalinterven-

tion, it is expected that it raises the students’ awareness

regarding the applicability ofMI as an intervention,when they

are trying to encourage the patient to make their own decisions

about behavior change. The feedback from debriefing also

contained suggestions that could be utilized to inform future

intervention improvement, particularly in regard to the SP

simulation.For example, students reported that the simulation

T A B L E 2 Change in outcome variables over time (N = 25)

Outcome

Baseline (T1)

(M ± SD)

Posttest after didactic

(T2) (M ± SD)

Posttest after simulation

(T3) (M ± SD) Difference P value

MI confidence 23.35 ± 6.96 16.61 ± 9.25 17.77 ± 6.01 T1 vs.T2 .001**

T1 vs.T3 .004**

T2 vs.T3 1.00

MIKAT total score 61.48 ± 10.60 70.51 ± 10.18 72.42 ± 9.99 T1 vs.T2 .0005***

T1 vs.T3 .0005***

T2 vs.T3 1.00

Attitude

consistent with

MI (MIKAT)

57 ± 19.79 58 ± 15.68 57 ± 25.54 T1 vs.T2 1.00

T1 vs.T3 1.00

T2 vs.T3 1.00

Substance abuse

myths (MIKAT)

55.2 ± 18.51 67.2 ± 18.60 66.0 ± 16.83 T1 vs.T2 .001**

T1 vs.T3 .040*

T2 vs.T3 1.00

MI principles

identified

(prescribed

behaviors)

(MIKAT)

3.92 ± 0.64 4.36 ± 0.64 4.88 ± 0.33 T1 vs.T2 .039*

T1 vs.T3 .0005***

T2 vs.T3 .001**

Principles not

consistent with

MI identified

(proscribed

behaviors)

(MIKAT)

2.12 ± 1.67 0.68 ± 1.25 0.68 ± 1.14 T1 vs.T2 .0005***

T1 vs.T3 .001**

T2 vs.T3 1.00

Abbreviations:MI, motivational interviewing;MIKAT, motivationalinterviewing knowledge and attitude test.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

686 | CHANG ET AL.

statistically significant difference in scores between the postdidactic and

post‐SP simulation shows that while there was no significant gain in

knowledge,there was also no significant loss of knowledge.There was a

2‐week span between the time the students received the didactic lecture

with role‐playing and the simulation,during which time other course

content was discussed.This could indicate that the simulation and the

preparation the students performed for the simulation helped to maintain

their increased knowledgemeasured bythe MIKAT but did not

necessarily add to it.Edwards et al26 also found that knowledge scores

increased significantlyfrom pre to posttest, but did not change

significantly from the posttest relative to the 3‐ or 6‐month follow‐up.

The MIKAT subcomponent for the identification of MI principles

showed a statistically significant increase between allthree times

points,indicating that the students improved their knowledge base

regarding the identification of the core principles of MI.This can be

attributed to an increase in knowledge regarding MI core principles

that serve as the foundation for this behavior change intervention

technique.In terms of attitudes consistent with MI,there was no

statistically significantchange between any of the time points.

Attitude may not be easy to change, particularly with a brief

educationalintervention such as the one utilized in this study.Two

previous studies that focused on medicalresidents found that brief

educationalinterventions failed to change resident’s perception on

the importance of counseling or effectiveness of counseling.24,27

Evaluation of the SP simulation scenarios using the BECCI

demonstrated that students could perform MI technique with an

average score of 3.0065. This indicated that they exhibited a

good deal of behavior change counseling skills.Unfortunately,

there is not a control group or baseline score to compare the

BECCI scores for comparative analysis focusing on skillacquisi-

tion with the MI education. However, use of this tool demon-

strated that students could perform MI skills after receiving the

MI simulation.It also can be useful to identify areas of needed

improvement for skillacquisition in future studies.Our findings

were consistent with previous studies that examined the out-

come of an MI training and found an improvementin medical

students’ MI skills, including the use of open‐ended questions,

reflection,affirmations,and empathy.15-17

The students’ feedback in the debriefing section indicated

that students found value in the MI educational intervention and

noted skill acquisition.While there is no expectation for students

to be experts in MI techniques after this educationalinterven-

tion, it is expected that it raises the students’ awareness

regarding the applicability ofMI as an intervention,when they

are trying to encourage the patient to make their own decisions

about behavior change. The feedback from debriefing also

contained suggestions that could be utilized to inform future

intervention improvement, particularly in regard to the SP

simulation.For example, students reported that the simulation

T A B L E 2 Change in outcome variables over time (N = 25)

Outcome

Baseline (T1)

(M ± SD)

Posttest after didactic

(T2) (M ± SD)

Posttest after simulation

(T3) (M ± SD) Difference P value

MI confidence 23.35 ± 6.96 16.61 ± 9.25 17.77 ± 6.01 T1 vs.T2 .001**

T1 vs.T3 .004**

T2 vs.T3 1.00

MIKAT total score 61.48 ± 10.60 70.51 ± 10.18 72.42 ± 9.99 T1 vs.T2 .0005***

T1 vs.T3 .0005***

T2 vs.T3 1.00

Attitude

consistent with

MI (MIKAT)

57 ± 19.79 58 ± 15.68 57 ± 25.54 T1 vs.T2 1.00

T1 vs.T3 1.00

T2 vs.T3 1.00

Substance abuse

myths (MIKAT)

55.2 ± 18.51 67.2 ± 18.60 66.0 ± 16.83 T1 vs.T2 .001**

T1 vs.T3 .040*

T2 vs.T3 1.00

MI principles

identified

(prescribed

behaviors)

(MIKAT)

3.92 ± 0.64 4.36 ± 0.64 4.88 ± 0.33 T1 vs.T2 .039*

T1 vs.T3 .0005***

T2 vs.T3 .001**

Principles not

consistent with

MI identified

(proscribed

behaviors)

(MIKAT)

2.12 ± 1.67 0.68 ± 1.25 0.68 ± 1.14 T1 vs.T2 .0005***

T1 vs.T3 .001**

T2 vs.T3 1.00

Abbreviations:MI, motivational interviewing;MIKAT, motivationalinterviewing knowledge and attitude test.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

***P < .001.

686 | CHANG ET AL.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

process was anxiety provoking.The students in this study were

first year DNP students and had no previous experience with an

SP simulation. A practice SP simulation may have been useful

to familiarize students with the process and expectations to

reduce any anxiety.No high stakes grading was attached to the

simulation experience which the researcher hoped would reduce

any anxiety associated with it, but this may have not been

enough,based upon what the students indicated to the research

team.In addition,other improvements may include more practice

with MI skills to help students become more competent and

confident in their ability to perform MI.

6 | LIMITATIONS

Limitationsin this study included the use of one‐group prepost

design with a convenient sample of 31 DNP students.This creates

barriers to drawing strong conclusions ofthe study findings and

limits the generalizability ofthe study.Larger sample size would

allow the ability to conduct subgroup analyses to identify if certain

students’characteristics (eg,clinical experience)might have influ-

enced their learning outcomes. Another limitation of the study is that

students’ responses to the questions were subject to social

desirability.However,students were informed that they were given

T A B L E 3 BECCI score outcomes (N = 31)

Outcome (M ± SD) Percent

Practitioner invites the patient to talk about behavior change 3.10 ± 0.597 To some extent 12.9

A good deal 64.5

A great extent 22.6

Practitioner demonstrated sensitivity to talking about other issues 3.10 ± 0.597 To some extent 12.9

A good deal 64.5

A great extent 22.6

Practitioner encourages patient to talk about current behavior or status quo 4 ± 0.00 To some extent 0

A good deal 0

A great extent 100

Practitioner encourages patient to talk about change 3.10 ± 0.597 To some extent 12.9

A good deal 64.5

A great extent 22.6

Practitioner asks questions to elicit how patient thinks and feels about the topic 3.19 ± 0.601 To some extent 9.7

A good deal 61.3

A great extent 29

Practitioner uses empathic listening statements when the patient talks about the topic2.84 ± 0.688 To some extent 32.3

A good deal 51.6

A great extent 16.1

Practitioner uses summaries to bring together what the patient says about the topic 2.45 ± 0.850 Minimally 6.5

To some extent 58.1

A good deal 19.4

A great extent 16.1

Practitioner acknowledges challenges about behavior change that the patient faces 2.52 ± 0.851 Minimally 6.5

To some extent 51.6

A good deal 25.8

A great extent 16.1

When practitioner provides information,it is sensitive to patient concern and understanding3.03 ± 0.547 To some extent 12.9

A good deal 71

A great extent 16.1

Practitioner actively conveys respect for patient choice about behavior change 2.81 ± 0.792 Minimally 3.2

To some extent 32.3

A good deal 45.2

A great extent 19.4

Practitioner and patient exchange ideas about how the patient could change current behavior2.90 ± 0.597 To some extent 22.6

A good deal 64.5

A great extent 12.9

Mean total score 3.0065 ± 0.35771

Practitioner speaks for approximately More than half the time 45.2

About half the time 48.4

Less than half the time 6.5

Abbreviations:BECCI, behavior change counseling index;SD, standard deviation.

CHANG ET AL. | 687

first year DNP students and had no previous experience with an

SP simulation. A practice SP simulation may have been useful

to familiarize students with the process and expectations to

reduce any anxiety.No high stakes grading was attached to the

simulation experience which the researcher hoped would reduce

any anxiety associated with it, but this may have not been

enough,based upon what the students indicated to the research

team.In addition,other improvements may include more practice

with MI skills to help students become more competent and

confident in their ability to perform MI.

6 | LIMITATIONS

Limitationsin this study included the use of one‐group prepost

design with a convenient sample of 31 DNP students.This creates

barriers to drawing strong conclusions ofthe study findings and

limits the generalizability ofthe study.Larger sample size would

allow the ability to conduct subgroup analyses to identify if certain

students’characteristics (eg,clinical experience)might have influ-

enced their learning outcomes. Another limitation of the study is that

students’ responses to the questions were subject to social

desirability.However,students were informed that they were given

T A B L E 3 BECCI score outcomes (N = 31)

Outcome (M ± SD) Percent

Practitioner invites the patient to talk about behavior change 3.10 ± 0.597 To some extent 12.9

A good deal 64.5

A great extent 22.6

Practitioner demonstrated sensitivity to talking about other issues 3.10 ± 0.597 To some extent 12.9

A good deal 64.5

A great extent 22.6

Practitioner encourages patient to talk about current behavior or status quo 4 ± 0.00 To some extent 0

A good deal 0

A great extent 100

Practitioner encourages patient to talk about change 3.10 ± 0.597 To some extent 12.9

A good deal 64.5

A great extent 22.6

Practitioner asks questions to elicit how patient thinks and feels about the topic 3.19 ± 0.601 To some extent 9.7

A good deal 61.3

A great extent 29

Practitioner uses empathic listening statements when the patient talks about the topic2.84 ± 0.688 To some extent 32.3

A good deal 51.6

A great extent 16.1

Practitioner uses summaries to bring together what the patient says about the topic 2.45 ± 0.850 Minimally 6.5

To some extent 58.1

A good deal 19.4

A great extent 16.1

Practitioner acknowledges challenges about behavior change that the patient faces 2.52 ± 0.851 Minimally 6.5

To some extent 51.6

A good deal 25.8

A great extent 16.1

When practitioner provides information,it is sensitive to patient concern and understanding3.03 ± 0.547 To some extent 12.9

A good deal 71

A great extent 16.1

Practitioner actively conveys respect for patient choice about behavior change 2.81 ± 0.792 Minimally 3.2

To some extent 32.3

A good deal 45.2

A great extent 19.4

Practitioner and patient exchange ideas about how the patient could change current behavior2.90 ± 0.597 To some extent 22.6

A good deal 64.5

A great extent 12.9

Mean total score 3.0065 ± 0.35771

Practitioner speaks for approximately More than half the time 45.2

About half the time 48.4

Less than half the time 6.5

Abbreviations:BECCI, behavior change counseling index;SD, standard deviation.

CHANG ET AL. | 687

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

full credit for the SP simulation if they participated and put forth a

good effort. This also helped to reduce social desirability bias. Finally,

our study did not examine students’ knowledge and attitudes toward

older adults with opioid abuse as outcomes of MItraining.Future

research should incorporate knowledge and attitude measures as

training outcomes.

7 | CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that an MIeducation can successfully

be implemented into a DNP curriculum with promising results in

improving student’s knowledge and confidence, as well as

demonstrating skill acquisition. This study showed that the SP

simulation is a promising format to educate students on

behavioral interventions like MI, by allowing them to interact

with a real patient in a safe and supervised setting.Even with the

limitations of the study, there were valuable findings that

supported the implementation of MI education for DNP students.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The study was funded by the Health Foundation for Western and

Central New York (grant no.870‐12).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID

Yu‐Ping Chang http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2328-6876

REFERENCES

1. Chang YP,Compton P.Opioid misuse/abuse and quality persistent pain

management in older adults.J Gerontol Nurs.2016;42(12):21‐30.https://

doi.org/10.3928/00989134‐20161110‐06

2. Olfson M,Wang S,Iza M, Crystal S,Blanco C.National trends in the

office‐based prescription ofschedule II opioids.J Clin Psychiatry.

2013;74(9):932‐939.https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08349

3. Kalapatapu R,Sullivan M.Prescription use disorder in older adults.

Am J Addict. 2010;19(6):515‐522.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521‐

0391.2010.00080.x

4. Chang YP, Compton P. Management ofchronic pain with chronic

opioid therapy in patients with substance use disorders.Addict Sci

Clin Pract.2013;8(1):21.https://doi.org/10.1186/1940‐0640‐8‐21

5. Franklin GM.Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a position paper of

the American academy of neurology.Neurology.2014;83(14):1277‐

1284.https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000839

6. Substance Abuse and MentalHealth Service Administration (2013).

Results from the 2012 national survey on drug use and health: summary

of national findings.Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/

NSDUH/2012summnatfinddettables/nationalfindings/

NSDUHresults2012.htm

7. Chang YP. Factors Associated with Prescription Opioid Misuse in

Adults Aged 50 or Older.Nurs Outlook.2018;66(2):112‐120.https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2017.10.007

8. Smedslund G,Berg R, Hammerstrom K,et al. Motivationalinter-

viewing for substance abuse.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2011;11(5).

https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008063.pub2

9. Dunhill D, Schmidt S, Klein R. Motivational interviewing interventions

in graduate medicaleducation:a systematic review ofevidence.J