Challenges and Opportunities of Free Flaps in Nepal: A Review

VerifiedAdded on 2022/11/25

|7

|5423

|291

Report

AI Summary

This report presents a retrospective cohort study analyzing the first 108 free flap cases performed in Nepal, focusing on the challenges and opportunities within a developing country setting. The study, conducted at Public Health Concern Trust–NEPAL hospitals, reviews patient demographics, indications for surgery (including tumor, trauma, and burns), types of flaps used (radial artery forearm, anterolateral thigh, and free fibular flaps being the most common), hospital stays, complications, and the impact of microsurgery teaching workshops. The findings reveal a flap success rate of approximately 90%, highlighting the feasibility of reconstructive microsurgery with persistent technical support and training programs. The study underscores the importance of such initiatives in improving access to reconstructive services and achieving positive outcomes in resource-limited environments.

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327340729

Review of the First 108 Free Flaps at Public Health Concern Trust–NEPAL

Hospitals: Challenges and Opportunities in Developing Countries

Article in Annals of Plastic Surgery · August 2018

DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001583

CITATIONS

0

READS

40

11 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

MicrosurgeryView project

burn surgeryView project

Kiran Nakarmi

Kirtipur Hospital

18PUBLICATIONS19CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Bishal Karki

Kathmandu Model Hospital

12PUBLICATIONS30CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Review of the First 108 Free Flaps at Public Health Concern Trust–NEPAL

Hospitals: Challenges and Opportunities in Developing Countries

Article in Annals of Plastic Surgery · August 2018

DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001583

CITATIONS

0

READS

40

11 authors, including:

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

MicrosurgeryView project

burn surgeryView project

Kiran Nakarmi

Kirtipur Hospital

18PUBLICATIONS19CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Bishal Karki

Kathmandu Model Hospital

12PUBLICATIONS30CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

Review of the First 108 Free Flaps at Public Health Conce

Trust–NEPAL Hospitals

Challenges and Opportunities in Developing Countries

Kiran K. Nakarmi, MCh,* Danielle H. Rochlin, MD,† Surendra J. Basnet, MS,* Pramila Sha

Bishal Karki, MCh,* Mangal G. Magar, FCPS,* Krishna K. Nagarkoti, MBBS,*

Pradeep K. Rajbhandari, MD,‡ Devendra Maharjan, MD,‡

Susan S. Prajapati, MD,‡ and Shankar M. Rai, MS*

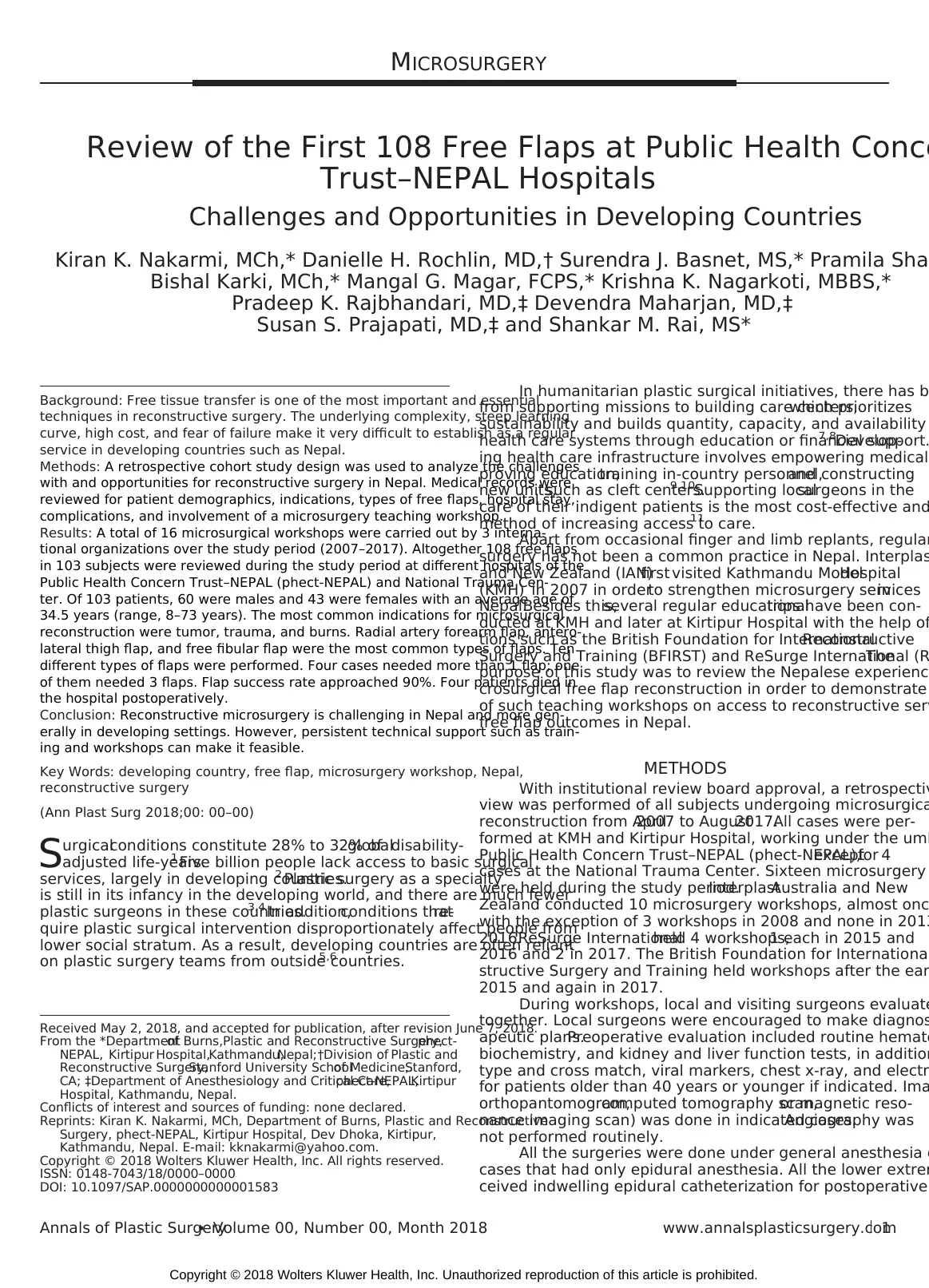

Background: Free tissue transfer is one of the most important and essential

techniques in reconstructive surgery. The underlying complexity, steep learning

curve, high cost, and fear of failure make it very difficult to establish as a regular

service in developing countries such as Nepal.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study design was used to analyze the challenges

with and opportunities for reconstructive surgery in Nepal. Medical records were

reviewed for patient demographics, indications, types of free flaps, hospital stay,

complications, and involvement of a microsurgery teaching workshop.

Results: A total of 16 microsurgical workshops were carried out by 3 interna-

tional organizations over the study period (2007–2017). Altogether 108 free flaps

in 103 subjects were reviewed during the study period at different hospitals of the

Public Health Concern Trust–NEPAL (phect-NEPAL) and National Trauma Cen-

ter. Of 103 patients, 60 were males and 43 were females with an average age of

34.5 years (range, 8–73 years). The most common indications for microsurgical

reconstruction were tumor, trauma, and burns. Radial artery forearm flap, antero-

lateral thigh flap, and free fibular flap were the most common types of flaps. Ten

different types of flaps were performed. Four cases needed more than 1 flap; one

of them needed 3 flaps. Flap success rate approached 90%. Four patients died in

the hospital postoperatively.

Conclusion: Reconstructive microsurgery is challenging in Nepal and more gen-

erally in developing settings. However, persistent technical support such as train-

ing and workshops can make it feasible.

Key Words: developing country, free flap, microsurgery workshop, Nepal,

reconstructive surgery

(Ann Plast Surg 2018;00: 00–00)

Surgicalconditions constitute 28% to 32% ofglobaldisability-

adjusted life-years.1 Five billion people lack access to basic surgical

services, largely in developing countries.2 Plastic surgery as a specialty

is still in its infancy in the developing world, and there are much fewer

plastic surgeons in these countries.3,4 In addition,conditions thatre-

quire plastic surgical intervention disproportionately affect people from

lower social stratum. As a result, developing countries are often reliant

on plastic surgery teams from outside countries.5,6

In humanitarian plastic surgical initiatives, there has b

from supporting missions to building care centers,which prioritizes

sustainability and builds quantity, capacity, and availability

health care systems through education or financial support.7,8Develop-

ing health care infrastructure involves empowering medical

proving education,training in-country personnel,and constructing

new units,such as cleft centers.9,10Supporting localsurgeons in the

care of their indigent patients is the most cost-effective and

method of increasing access to care.11

Apart from occasional finger and limb replants, regular

surgery has not been a common practice in Nepal. Interplas

and New Zealand (IAN)first visited Kathmandu ModelHospital

(KMH) in 2007 in orderto strengthen microsurgery servicesin

Nepal.Besides this,several regular educationaltrips have been con-

ducted at KMH and later at Kirtipur Hospital with the help of

tions such as the British Foundation for InternationalReconstructive

Surgery and Training (BFIRST) and ReSurge International (RThe

purpose of this study was to review the Nepalese experienc

crosurgical free flap reconstruction in order to demonstrate

of such teaching workshops on access to reconstructive serv

free flap outcomes in Nepal.

METHODS

With institutional review board approval, a retrospectiv

view was performed of all subjects undergoing microsurgica

reconstruction from April2007 to August2017.All cases were per-

formed at KMH and Kirtipur Hospital, working under the umb

Public Health Concern Trust–NEPAL (phect-NEPAL),exceptfor 4

cases at the National Trauma Center. Sixteen microsurgery

were held during the study period.InterplastAustralia and New

Zealand conducted 10 microsurgery workshops, almost onc

with the exception of 3 workshops in 2008 and none in 2013

2016.ReSurge Internationalheld 4 workshops,1 each in 2015 and

2016 and 2 in 2017. The British Foundation for International

structive Surgery and Training held workshops after the ear

2015 and again in 2017.

During workshops, local and visiting surgeons evaluate

together. Local surgeons were encouraged to make diagnos

apeutic plans.Preoperative evaluation included routine hemato

biochemistry, and kidney and liver function tests, in addition

type and cross match, viral markers, chest x-ray, and electr

for patients older than 40 years or younger if indicated. Ima

orthopantomogram,computed tomography scan,or magnetic reso-

nance imaging scan) was done in indicated cases.Angiography was

not performed routinely.

All the surgeries were done under general anesthesia e

cases that had only epidural anesthesia. All the lower extrem

ceived indwelling epidural catheterization for postoperative

Received May 2, 2018, and accepted for publication, after revision June 7, 2018.

From the *Departmentof Burns,Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery,phect-

NEPAL, Kirtipur Hospital,Kathmandu,Nepal;†Division of Plastic and

Reconstructive Surgery,Stanford University Schoolof Medicine,Stanford,

CA; ‡Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care,phect-NEPAL,Kirtipur

Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding: none declared.

Reprints: Kiran K. Nakarmi, MCh, Department of Burns, Plastic and Reconstructive

Surgery, phect-NEPAL, Kirtipur Hospital, Dev Dhoka, Kirtipur,

Kathmandu, Nepal. E-mail: kknakarmi@yahoo.com.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

ISSN: 0148-7043/18/0000–0000

DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001583

MICROSURGERY

Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018 www.annalsplasticsurgery.com1

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Trust–NEPAL Hospitals

Challenges and Opportunities in Developing Countries

Kiran K. Nakarmi, MCh,* Danielle H. Rochlin, MD,† Surendra J. Basnet, MS,* Pramila Sha

Bishal Karki, MCh,* Mangal G. Magar, FCPS,* Krishna K. Nagarkoti, MBBS,*

Pradeep K. Rajbhandari, MD,‡ Devendra Maharjan, MD,‡

Susan S. Prajapati, MD,‡ and Shankar M. Rai, MS*

Background: Free tissue transfer is one of the most important and essential

techniques in reconstructive surgery. The underlying complexity, steep learning

curve, high cost, and fear of failure make it very difficult to establish as a regular

service in developing countries such as Nepal.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study design was used to analyze the challenges

with and opportunities for reconstructive surgery in Nepal. Medical records were

reviewed for patient demographics, indications, types of free flaps, hospital stay,

complications, and involvement of a microsurgery teaching workshop.

Results: A total of 16 microsurgical workshops were carried out by 3 interna-

tional organizations over the study period (2007–2017). Altogether 108 free flaps

in 103 subjects were reviewed during the study period at different hospitals of the

Public Health Concern Trust–NEPAL (phect-NEPAL) and National Trauma Cen-

ter. Of 103 patients, 60 were males and 43 were females with an average age of

34.5 years (range, 8–73 years). The most common indications for microsurgical

reconstruction were tumor, trauma, and burns. Radial artery forearm flap, antero-

lateral thigh flap, and free fibular flap were the most common types of flaps. Ten

different types of flaps were performed. Four cases needed more than 1 flap; one

of them needed 3 flaps. Flap success rate approached 90%. Four patients died in

the hospital postoperatively.

Conclusion: Reconstructive microsurgery is challenging in Nepal and more gen-

erally in developing settings. However, persistent technical support such as train-

ing and workshops can make it feasible.

Key Words: developing country, free flap, microsurgery workshop, Nepal,

reconstructive surgery

(Ann Plast Surg 2018;00: 00–00)

Surgicalconditions constitute 28% to 32% ofglobaldisability-

adjusted life-years.1 Five billion people lack access to basic surgical

services, largely in developing countries.2 Plastic surgery as a specialty

is still in its infancy in the developing world, and there are much fewer

plastic surgeons in these countries.3,4 In addition,conditions thatre-

quire plastic surgical intervention disproportionately affect people from

lower social stratum. As a result, developing countries are often reliant

on plastic surgery teams from outside countries.5,6

In humanitarian plastic surgical initiatives, there has b

from supporting missions to building care centers,which prioritizes

sustainability and builds quantity, capacity, and availability

health care systems through education or financial support.7,8Develop-

ing health care infrastructure involves empowering medical

proving education,training in-country personnel,and constructing

new units,such as cleft centers.9,10Supporting localsurgeons in the

care of their indigent patients is the most cost-effective and

method of increasing access to care.11

Apart from occasional finger and limb replants, regular

surgery has not been a common practice in Nepal. Interplas

and New Zealand (IAN)first visited Kathmandu ModelHospital

(KMH) in 2007 in orderto strengthen microsurgery servicesin

Nepal.Besides this,several regular educationaltrips have been con-

ducted at KMH and later at Kirtipur Hospital with the help of

tions such as the British Foundation for InternationalReconstructive

Surgery and Training (BFIRST) and ReSurge International (RThe

purpose of this study was to review the Nepalese experienc

crosurgical free flap reconstruction in order to demonstrate

of such teaching workshops on access to reconstructive serv

free flap outcomes in Nepal.

METHODS

With institutional review board approval, a retrospectiv

view was performed of all subjects undergoing microsurgica

reconstruction from April2007 to August2017.All cases were per-

formed at KMH and Kirtipur Hospital, working under the umb

Public Health Concern Trust–NEPAL (phect-NEPAL),exceptfor 4

cases at the National Trauma Center. Sixteen microsurgery

were held during the study period.InterplastAustralia and New

Zealand conducted 10 microsurgery workshops, almost onc

with the exception of 3 workshops in 2008 and none in 2013

2016.ReSurge Internationalheld 4 workshops,1 each in 2015 and

2016 and 2 in 2017. The British Foundation for International

structive Surgery and Training held workshops after the ear

2015 and again in 2017.

During workshops, local and visiting surgeons evaluate

together. Local surgeons were encouraged to make diagnos

apeutic plans.Preoperative evaluation included routine hemato

biochemistry, and kidney and liver function tests, in addition

type and cross match, viral markers, chest x-ray, and electr

for patients older than 40 years or younger if indicated. Ima

orthopantomogram,computed tomography scan,or magnetic reso-

nance imaging scan) was done in indicated cases.Angiography was

not performed routinely.

All the surgeries were done under general anesthesia e

cases that had only epidural anesthesia. All the lower extrem

ceived indwelling epidural catheterization for postoperative

Received May 2, 2018, and accepted for publication, after revision June 7, 2018.

From the *Departmentof Burns,Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery,phect-

NEPAL, Kirtipur Hospital,Kathmandu,Nepal;†Division of Plastic and

Reconstructive Surgery,Stanford University Schoolof Medicine,Stanford,

CA; ‡Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care,phect-NEPAL,Kirtipur

Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding: none declared.

Reprints: Kiran K. Nakarmi, MCh, Department of Burns, Plastic and Reconstructive

Surgery, phect-NEPAL, Kirtipur Hospital, Dev Dhoka, Kirtipur,

Kathmandu, Nepal. E-mail: kknakarmi@yahoo.com.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

ISSN: 0148-7043/18/0000–0000

DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001583

MICROSURGERY

Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018 www.annalsplasticsurgery.com1

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

During workshops, flap dissection and donor site preparation were each

performed by a team consisting of a local and visiting surgeons in order

to optimize focused learning; both local surgeons then participated in

flap in-setting and microanastomosis.Surgeries priorto May 2008

and those done at National Trauma Center were performed with operat-

ing loupes. The remaining flaps were performed with operating micro-

scopes.Postoperatively,patients remained intubated overnightif the

surgery lasted for 12 hours or longer or if there were issues with venti-

lation.Patients were generally transferred to the postoperative ward

(which is a step-down unit with a 4:1 patient-to-nurse ratio) or to the in-

tensive care unit if they were intubated. Flaps were monitored by clini-

cal examination and Dopplerevery 15 minutes for2 hours,every

30 minutes for the next 2 hours, and then every 2 hours for the next

2 days. Flap monitoring was subsequently done every 6 hours until dis-

charge. Feeding was started after 24 hours of flap observation, except

for cases of oral surgery in which feeding via nasogastric tube was per-

formed until oral feeding after the fifth postoperative day. Most of the

oral cancer patients received temporary tracheostomy that was typically

removed by 1 week after a plugging trial. Patients were given 2500 IU

of heparin intravenously twice daily for 5 days and low-dose aspirin for

a month. Discharge criteria included no further need for flap monitor-

ing, resolved flap swelling, tracheostomy and nasogastric tube removed,

adequate oral intake, and independent patient mobility.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 108 free flaps in 103 patients were reviewed. Males

outnumbered females (Table 1). The average age was 34.5 years (range,

8–73 years),with patients mostfrequently in the 16- to 30-year age

group (39.8%).

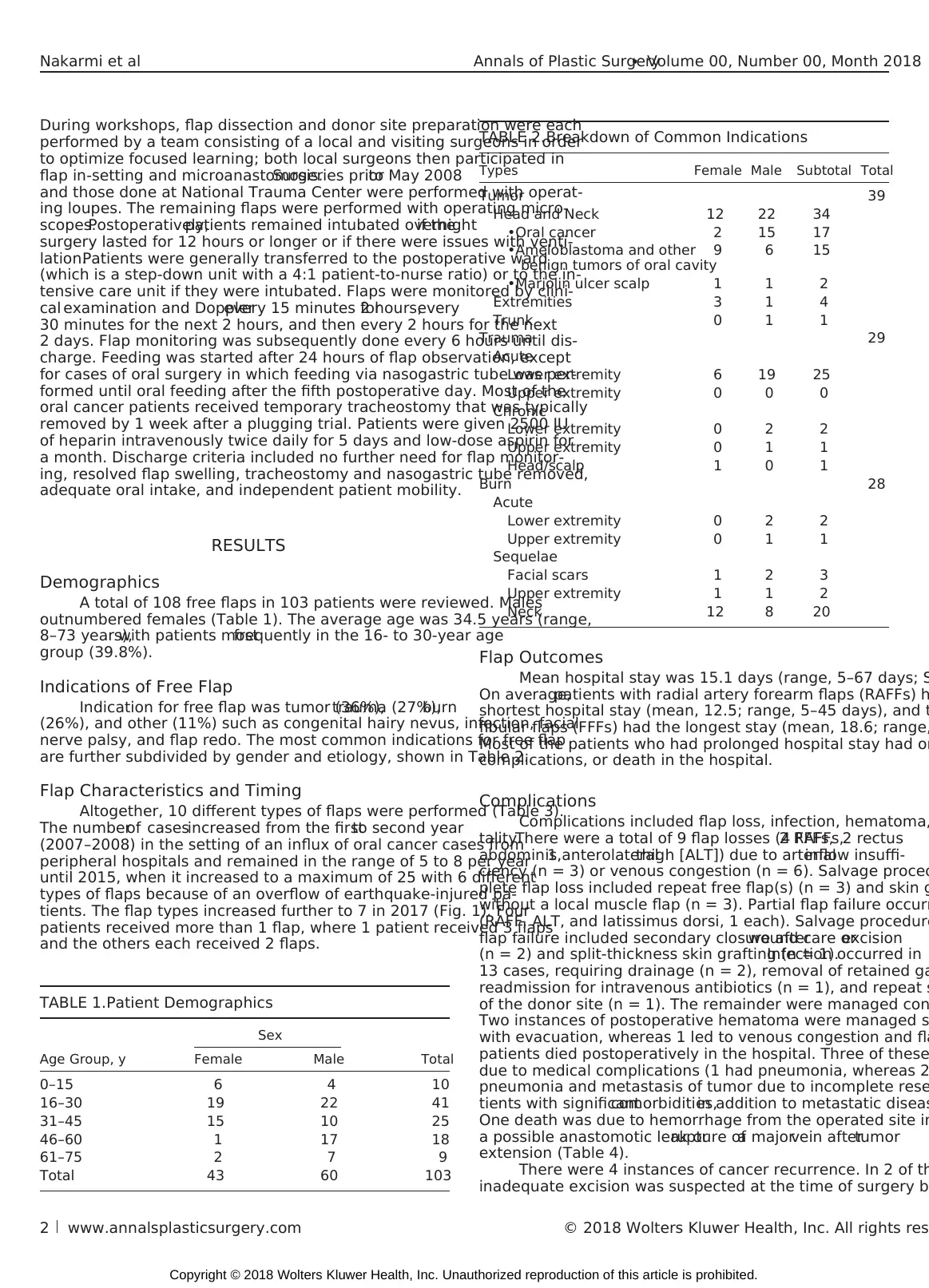

Indications of Free Flap

Indication for free flap was tumor (36%),trauma (27%),burn

(26%), and other (11%) such as congenital hairy nevus, infection, facial

nerve palsy, and flap redo. The most common indications for free flap

are further subdivided by gender and etiology, shown in Table 2.

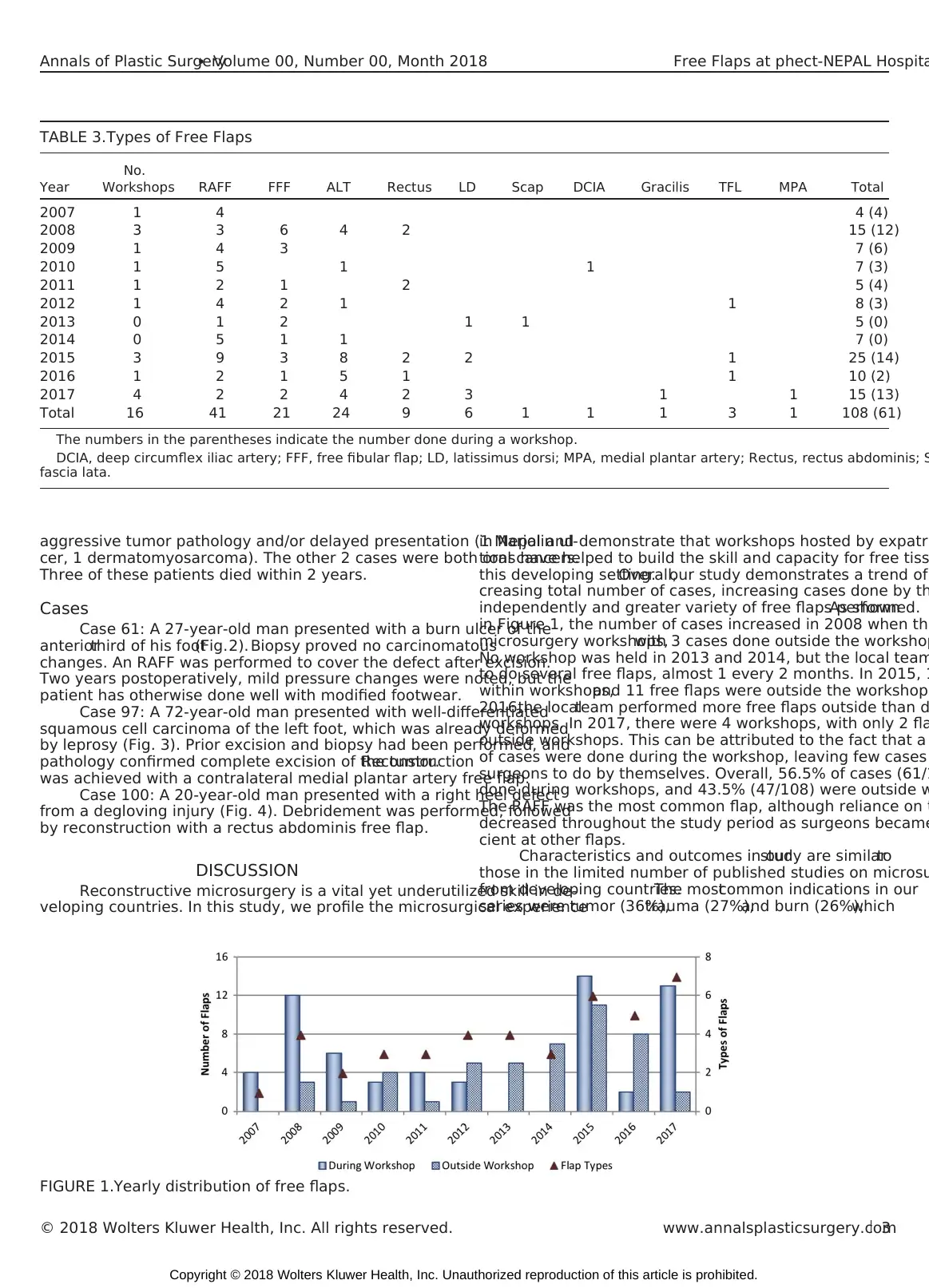

Flap Characteristics and Timing

Altogether, 10 different types of flaps were performed (Table 3).

The numberof casesincreased from the firstto second year

(2007–2008) in the setting of an influx of oral cancer cases from

peripheral hospitals and remained in the range of 5 to 8 per year

until 2015, when it increased to a maximum of 25 with 6 different

types of flaps because of an overflow of earthquake-injured pa-

tients. The flap types increased further to 7 in 2017 (Fig. 1). Four

patients received more than 1 flap, where 1 patient received 3 flaps

and the others each received 2 flaps.

Flap Outcomes

Mean hospital stay was 15.1 days (range, 5–67 days; S

On average,patients with radial artery forearm flaps (RAFFs) h

shortest hospital stay (mean, 12.5; range, 5–45 days), and t

fibular flaps (FFFs) had the longest stay (mean, 18.6; range,

Most of the patients who had prolonged hospital stay had or

complications, or death in the hospital.

Complications

Complications included flap loss, infection, hematoma,

tality.There were a total of 9 flap losses (4 FFFs,2 RAFFs,2 rectus

abdominis,1 anterolateralthigh [ALT]) due to arterialinflow insuffi-

ciency (n = 3) or venous congestion (n = 6). Salvage proced

plete flap loss included repeat free flap(s) (n = 3) and skin g

without a local muscle flap (n = 3). Partial flap failure occurr

(RAFF, ALT, and latissimus dorsi, 1 each). Salvage procedure

flap failure included secondary closure afterwound care orexcision

(n = 2) and split-thickness skin grafting (n = 1).Infection occurred in

13 cases, requiring drainage (n = 2), removal of retained ga

readmission for intravenous antibiotics (n = 1), and repeat s

of the donor site (n = 1). The remainder were managed con

Two instances of postoperative hematoma were managed s

with evacuation, whereas 1 led to venous congestion and fla

patients died postoperatively in the hospital. Three of these

due to medical complications (1 had pneumonia, whereas 2

pneumonia and metastasis of tumor due to incomplete rese

tients with significantcomorbidities,in addition to metastatic diseas

One death was due to hemorrhage from the operated site in

a possible anastomotic leak orrupture ofa majorvein aftertumor

extension (Table 4).

There were 4 instances of cancer recurrence. In 2 of th

inadequate excision was suspected at the time of surgery b

TABLE 1.Patient Demographics

Sex

Age Group, y Female Male Total

0–15 6 4 10

16–30 19 22 41

31–45 15 10 25

46–60 1 17 18

61–75 2 7 9

Total 43 60 103

TABLE 2.Breakdown of Common Indications

Types Female Male Subtotal Total

Tumor 39

Head and Neck 12 22 34

•Oral cancer 2 15 17

•Ameloblastoma and other

benign tumors of oral cavity

9 6 15

•Marjolin ulcer scalp 1 1 2

Extremities 3 1 4

Trunk 0 1 1

Trauma 29

Acute

Lower extremity 6 19 25

Upper extremity 0 0 0

Chronic

Lower extremity 0 2 2

Upper extremity 0 1 1

Head/scalp 1 0 1

Burn 28

Acute

Lower extremity 0 2 2

Upper extremity 0 1 1

Sequelae

Facial scars 1 2 3

Upper extremity 1 1 2

Neck 12 8 20

Nakarmi et al Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018

2 www.annalsplasticsurgery.com © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights res

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

performed by a team consisting of a local and visiting surgeons in order

to optimize focused learning; both local surgeons then participated in

flap in-setting and microanastomosis.Surgeries priorto May 2008

and those done at National Trauma Center were performed with operat-

ing loupes. The remaining flaps were performed with operating micro-

scopes.Postoperatively,patients remained intubated overnightif the

surgery lasted for 12 hours or longer or if there were issues with venti-

lation.Patients were generally transferred to the postoperative ward

(which is a step-down unit with a 4:1 patient-to-nurse ratio) or to the in-

tensive care unit if they were intubated. Flaps were monitored by clini-

cal examination and Dopplerevery 15 minutes for2 hours,every

30 minutes for the next 2 hours, and then every 2 hours for the next

2 days. Flap monitoring was subsequently done every 6 hours until dis-

charge. Feeding was started after 24 hours of flap observation, except

for cases of oral surgery in which feeding via nasogastric tube was per-

formed until oral feeding after the fifth postoperative day. Most of the

oral cancer patients received temporary tracheostomy that was typically

removed by 1 week after a plugging trial. Patients were given 2500 IU

of heparin intravenously twice daily for 5 days and low-dose aspirin for

a month. Discharge criteria included no further need for flap monitor-

ing, resolved flap swelling, tracheostomy and nasogastric tube removed,

adequate oral intake, and independent patient mobility.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 108 free flaps in 103 patients were reviewed. Males

outnumbered females (Table 1). The average age was 34.5 years (range,

8–73 years),with patients mostfrequently in the 16- to 30-year age

group (39.8%).

Indications of Free Flap

Indication for free flap was tumor (36%),trauma (27%),burn

(26%), and other (11%) such as congenital hairy nevus, infection, facial

nerve palsy, and flap redo. The most common indications for free flap

are further subdivided by gender and etiology, shown in Table 2.

Flap Characteristics and Timing

Altogether, 10 different types of flaps were performed (Table 3).

The numberof casesincreased from the firstto second year

(2007–2008) in the setting of an influx of oral cancer cases from

peripheral hospitals and remained in the range of 5 to 8 per year

until 2015, when it increased to a maximum of 25 with 6 different

types of flaps because of an overflow of earthquake-injured pa-

tients. The flap types increased further to 7 in 2017 (Fig. 1). Four

patients received more than 1 flap, where 1 patient received 3 flaps

and the others each received 2 flaps.

Flap Outcomes

Mean hospital stay was 15.1 days (range, 5–67 days; S

On average,patients with radial artery forearm flaps (RAFFs) h

shortest hospital stay (mean, 12.5; range, 5–45 days), and t

fibular flaps (FFFs) had the longest stay (mean, 18.6; range,

Most of the patients who had prolonged hospital stay had or

complications, or death in the hospital.

Complications

Complications included flap loss, infection, hematoma,

tality.There were a total of 9 flap losses (4 FFFs,2 RAFFs,2 rectus

abdominis,1 anterolateralthigh [ALT]) due to arterialinflow insuffi-

ciency (n = 3) or venous congestion (n = 6). Salvage proced

plete flap loss included repeat free flap(s) (n = 3) and skin g

without a local muscle flap (n = 3). Partial flap failure occurr

(RAFF, ALT, and latissimus dorsi, 1 each). Salvage procedure

flap failure included secondary closure afterwound care orexcision

(n = 2) and split-thickness skin grafting (n = 1).Infection occurred in

13 cases, requiring drainage (n = 2), removal of retained ga

readmission for intravenous antibiotics (n = 1), and repeat s

of the donor site (n = 1). The remainder were managed con

Two instances of postoperative hematoma were managed s

with evacuation, whereas 1 led to venous congestion and fla

patients died postoperatively in the hospital. Three of these

due to medical complications (1 had pneumonia, whereas 2

pneumonia and metastasis of tumor due to incomplete rese

tients with significantcomorbidities,in addition to metastatic diseas

One death was due to hemorrhage from the operated site in

a possible anastomotic leak orrupture ofa majorvein aftertumor

extension (Table 4).

There were 4 instances of cancer recurrence. In 2 of th

inadequate excision was suspected at the time of surgery b

TABLE 1.Patient Demographics

Sex

Age Group, y Female Male Total

0–15 6 4 10

16–30 19 22 41

31–45 15 10 25

46–60 1 17 18

61–75 2 7 9

Total 43 60 103

TABLE 2.Breakdown of Common Indications

Types Female Male Subtotal Total

Tumor 39

Head and Neck 12 22 34

•Oral cancer 2 15 17

•Ameloblastoma and other

benign tumors of oral cavity

9 6 15

•Marjolin ulcer scalp 1 1 2

Extremities 3 1 4

Trunk 0 1 1

Trauma 29

Acute

Lower extremity 6 19 25

Upper extremity 0 0 0

Chronic

Lower extremity 0 2 2

Upper extremity 0 1 1

Head/scalp 1 0 1

Burn 28

Acute

Lower extremity 0 2 2

Upper extremity 0 1 1

Sequelae

Facial scars 1 2 3

Upper extremity 1 1 2

Neck 12 8 20

Nakarmi et al Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018

2 www.annalsplasticsurgery.com © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights res

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

aggressive tumor pathology and/or delayed presentation (1 Marjolin ul-

cer, 1 dermatomyosarcoma). The other 2 cases were both oral cancers.

Three of these patients died within 2 years.

Cases

Case 61: A 27-year-old man presented with a burn ulcer of the

anteriorthird of his foot(Fig.2). Biopsy proved no carcinomatous

changes. An RAFF was performed to cover the defect after excision.

Two years postoperatively, mild pressure changes were noted, but the

patient has otherwise done well with modified footwear.

Case 97: A 72-year-old man presented with well-differentiated

squamous cell carcinoma of the left foot, which was already deformed

by leprosy (Fig. 3). Prior excision and biopsy had been performed, and

pathology confirmed complete excision of the tumor.Reconstruction

was achieved with a contralateral medial plantar artery free flap.

Case 100: A 20-year-old man presented with a right heel defect

from a degloving injury (Fig. 4). Debridement was performed, followed

by reconstruction with a rectus abdominis free flap.

DISCUSSION

Reconstructive microsurgery is a vital yet underutilized skill in de-

veloping countries. In this study, we profile the microsurgical experience

in Nepal and demonstrate that workshops hosted by expatri

tions have helped to build the skill and capacity for free tiss

this developing setting.Overall,our study demonstrates a trend of

creasing total number of cases, increasing cases done by th

independently and greater variety of free flaps performed.As shown

in Figure 1, the number of cases increased in 2008 when the

microsurgery workshops,with 3 cases done outside the workshop

No workshop was held in 2013 and 2014, but the local team

to do several free flaps, almost 1 every 2 months. In 2015, 1

within workshops,and 11 free flaps were outside the workshops

2016,the localteam performed more free flaps outside than d

workshops. In 2017, there were 4 workshops, with only 2 fla

outside workshops. This can be attributed to the fact that a

of cases were done during the workshop, leaving few cases

surgeons to do by themselves. Overall, 56.5% of cases (61/1

done during workshops, and 43.5% (47/108) were outside w

The RAFF was the most common flap, although reliance on t

decreased throughout the study period as surgeons became

cient at other flaps.

Characteristics and outcomes in ourstudy are similarto

those in the limited number of published studies on microsu

from developing countries.The mostcommon indications in our

series were tumor (36%),trauma (27%),and burn (26%),which

FIGURE 1.Yearly distribution of free flaps.

TABLE 3.Types of Free Flaps

Year

No.

Workshops RAFF FFF ALT Rectus LD Scap DCIA Gracilis TFL MPA Total

2007 1 4 4 (4)

2008 3 3 6 4 2 15 (12)

2009 1 4 3 7 (6)

2010 1 5 1 1 7 (3)

2011 1 2 1 2 5 (4)

2012 1 4 2 1 1 8 (3)

2013 0 1 2 1 1 5 (0)

2014 0 5 1 1 7 (0)

2015 3 9 3 8 2 2 1 25 (14)

2016 1 2 1 5 1 1 10 (2)

2017 4 2 2 4 2 3 1 1 15 (13)

Total 16 41 21 24 9 6 1 1 1 3 1 108 (61)

The numbers in the parentheses indicate the number done during a workshop.

DCIA, deep circumflex iliac artery; FFF, free fibular flap; LD, latissimus dorsi; MPA, medial plantar artery; Rectus, rectus abdominis; S

fascia lata.

Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018 Free Flaps at phect-NEPAL Hospita

© 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.annalsplasticsurgery.com3

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

cer, 1 dermatomyosarcoma). The other 2 cases were both oral cancers.

Three of these patients died within 2 years.

Cases

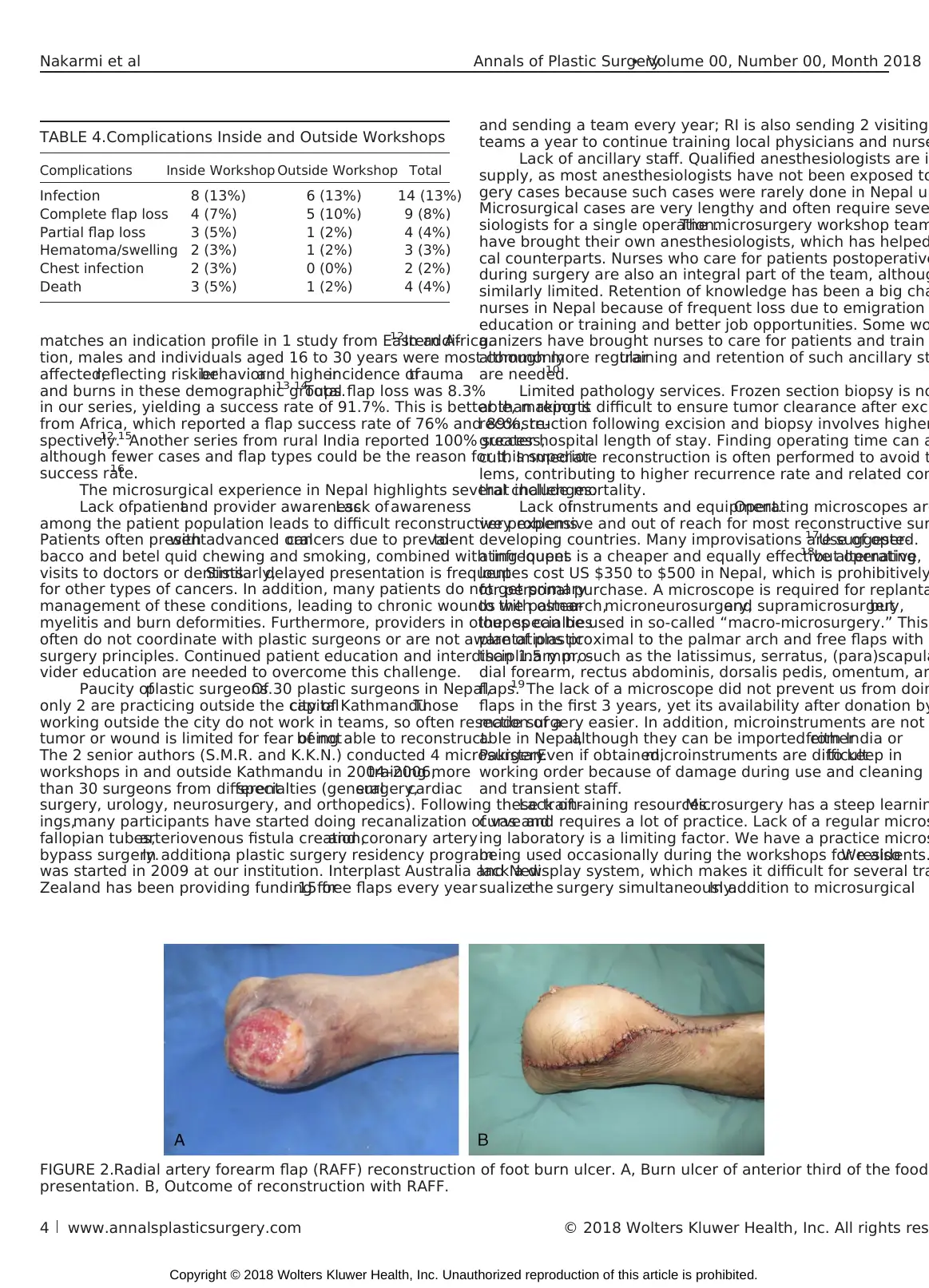

Case 61: A 27-year-old man presented with a burn ulcer of the

anteriorthird of his foot(Fig.2). Biopsy proved no carcinomatous

changes. An RAFF was performed to cover the defect after excision.

Two years postoperatively, mild pressure changes were noted, but the

patient has otherwise done well with modified footwear.

Case 97: A 72-year-old man presented with well-differentiated

squamous cell carcinoma of the left foot, which was already deformed

by leprosy (Fig. 3). Prior excision and biopsy had been performed, and

pathology confirmed complete excision of the tumor.Reconstruction

was achieved with a contralateral medial plantar artery free flap.

Case 100: A 20-year-old man presented with a right heel defect

from a degloving injury (Fig. 4). Debridement was performed, followed

by reconstruction with a rectus abdominis free flap.

DISCUSSION

Reconstructive microsurgery is a vital yet underutilized skill in de-

veloping countries. In this study, we profile the microsurgical experience

in Nepal and demonstrate that workshops hosted by expatri

tions have helped to build the skill and capacity for free tiss

this developing setting.Overall,our study demonstrates a trend of

creasing total number of cases, increasing cases done by th

independently and greater variety of free flaps performed.As shown

in Figure 1, the number of cases increased in 2008 when the

microsurgery workshops,with 3 cases done outside the workshop

No workshop was held in 2013 and 2014, but the local team

to do several free flaps, almost 1 every 2 months. In 2015, 1

within workshops,and 11 free flaps were outside the workshops

2016,the localteam performed more free flaps outside than d

workshops. In 2017, there were 4 workshops, with only 2 fla

outside workshops. This can be attributed to the fact that a

of cases were done during the workshop, leaving few cases

surgeons to do by themselves. Overall, 56.5% of cases (61/1

done during workshops, and 43.5% (47/108) were outside w

The RAFF was the most common flap, although reliance on t

decreased throughout the study period as surgeons became

cient at other flaps.

Characteristics and outcomes in ourstudy are similarto

those in the limited number of published studies on microsu

from developing countries.The mostcommon indications in our

series were tumor (36%),trauma (27%),and burn (26%),which

FIGURE 1.Yearly distribution of free flaps.

TABLE 3.Types of Free Flaps

Year

No.

Workshops RAFF FFF ALT Rectus LD Scap DCIA Gracilis TFL MPA Total

2007 1 4 4 (4)

2008 3 3 6 4 2 15 (12)

2009 1 4 3 7 (6)

2010 1 5 1 1 7 (3)

2011 1 2 1 2 5 (4)

2012 1 4 2 1 1 8 (3)

2013 0 1 2 1 1 5 (0)

2014 0 5 1 1 7 (0)

2015 3 9 3 8 2 2 1 25 (14)

2016 1 2 1 5 1 1 10 (2)

2017 4 2 2 4 2 3 1 1 15 (13)

Total 16 41 21 24 9 6 1 1 1 3 1 108 (61)

The numbers in the parentheses indicate the number done during a workshop.

DCIA, deep circumflex iliac artery; FFF, free fibular flap; LD, latissimus dorsi; MPA, medial plantar artery; Rectus, rectus abdominis; S

fascia lata.

Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018 Free Flaps at phect-NEPAL Hospita

© 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.annalsplasticsurgery.com3

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Paraphrase This Document

Need a fresh take? Get an instant paraphrase of this document with our AI Paraphraser

matches an indication profile in 1 study from Eastern Africa.12In addi-

tion, males and individuals aged 16 to 30 years were most commonly

affected,reflecting riskierbehaviorand higherincidence oftrauma

and burns in these demographic groups.13,14

Total flap loss was 8.3%

in our series, yielding a success rate of 91.7%. This is better than reports

from Africa, which reported a flap success rate of 76% and 89%, re-

spectively.12,15

Another series from rural India reported 100% success,

although fewer cases and flap types could be the reason for this superior

success rate.16

The microsurgical experience in Nepal highlights several challenges:

Lack ofpatientand provider awareness.Lack ofawareness

among the patient population leads to difficult reconstructive problems.

Patients often presentwith advanced oralcancers due to prevalentto-

bacco and betel quid chewing and smoking, combined with infrequent

visits to doctors or dentists.Similarly,delayed presentation is frequent

for other types of cancers. In addition, many patients do not get primary

management of these conditions, leading to chronic wounds with osteo-

myelitis and burn deformities. Furthermore, providers in other specialties

often do not coordinate with plastic surgeons or are not aware of plastic

surgery principles. Continued patient education and interdisciplinary pro-

vider education are needed to overcome this challenge.

Paucity ofplastic surgeons.Of 30 plastic surgeons in Nepal,

only 2 are practicing outside the capitalcity of Kathmandu.Those

working outside the city do not work in teams, so often resection of a

tumor or wound is limited for fear of notbeing able to reconstruct.

The 2 senior authors (S.M.R. and K.K.N.) conducted 4 microsurgery

workshops in and outside Kathmandu in 2004–2006,training more

than 30 surgeons from differentspecialties (generalsurgery,cardiac

surgery, urology, neurosurgery, and orthopedics). Following these train-

ings,many participants have started doing recanalization of vas and

fallopian tubes,arteriovenous fistula creation,and coronary artery

bypass surgery.In addition,a plastic surgery residency program

was started in 2009 at our institution. Interplast Australia and New

Zealand has been providing funding for15 free flaps every year

and sending a team every year; RI is also sending 2 visiting

teams a year to continue training local physicians and nurse

Lack of ancillary staff. Qualified anesthesiologists are i

supply, as most anesthesiologists have not been exposed to

gery cases because such cases were rarely done in Nepal un

Microsurgical cases are very lengthy and often require seve

siologists for a single operation.The microsurgery workshop team

have brought their own anesthesiologists, which has helped

cal counterparts. Nurses who care for patients postoperative

during surgery are also an integral part of the team, althoug

similarly limited. Retention of knowledge has been a big cha

nurses in Nepal because of frequent loss due to emigration

education or training and better job opportunities. Some wo

ganizers have brought nurses to care for patients and train

although more regulartraining and retention of such ancillary st

are needed.10

Limited pathology services. Frozen section biopsy is no

able, making it difficult to ensure tumor clearance after exci

reconstruction following excision and biopsy involves higher

greater hospital length of stay. Finding operating time can a

cult. Immediate reconstruction is often performed to avoid t

lems, contributing to higher recurrence rate and related com

that include mortality.

Lack ofinstruments and equipment.Operating microscopes are

very expensive and out of reach for most reconstructive sur

developing countries. Many improvisations are suggested.17Use of oper-

ating loupes is a cheaper and equally effective alternative,18but operating

loupes cost US $350 to $500 in Nepal, which is prohibitively

for personal purchase. A microscope is required for replanta

to the palmararch,microneurosurgery,and supramicrosurgery,but

loupes can be used in so-called “macro-microsurgery.” This

plantations proximal to the palmar arch and free flaps with

than 1.5 mm, such as the latissimus, serratus, (para)scapula

dial forearm, rectus abdominis, dorsalis pedis, omentum, an

flaps.19 The lack of a microscope did not prevent us from doin

flaps in the first 3 years, yet its availability after donation by

made surgery easier. In addition, microinstruments are not

able in Nepal,although they can be imported eitherfrom India or

Pakistan.Even if obtained,microinstruments are difficultto keep in

working order because of damage during use and cleaning b

and transient staff.

Lack oftraining resources.Microsurgery has a steep learnin

curve and requires a lot of practice. Lack of a regular micros

ing laboratory is a limiting factor. We have a practice micros

being used occasionally during the workshops for residents.We also

lack a display system, which makes it difficult for several tra

sualizethe surgery simultaneously.In addition to microsurgical

TABLE 4.Complications Inside and Outside Workshops

Complications Inside Workshop Outside Workshop Total

Infection 8 (13%) 6 (13%) 14 (13%)

Complete flap loss 4 (7%) 5 (10%) 9 (8%)

Partial flap loss 3 (5%) 1 (2%) 4 (4%)

Hematoma/swelling 2 (3%) 1 (2%) 3 (3%)

Chest infection 2 (3%) 0 (0%) 2 (2%)

Death 3 (5%) 1 (2%) 4 (4%)

FIGURE 2.Radial artery forearm flap (RAFF) reconstruction of foot burn ulcer. A, Burn ulcer of anterior third of the food

presentation. B, Outcome of reconstruction with RAFF.

Nakarmi et al Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018

4 www.annalsplasticsurgery.com © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights res

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

tion, males and individuals aged 16 to 30 years were most commonly

affected,reflecting riskierbehaviorand higherincidence oftrauma

and burns in these demographic groups.13,14

Total flap loss was 8.3%

in our series, yielding a success rate of 91.7%. This is better than reports

from Africa, which reported a flap success rate of 76% and 89%, re-

spectively.12,15

Another series from rural India reported 100% success,

although fewer cases and flap types could be the reason for this superior

success rate.16

The microsurgical experience in Nepal highlights several challenges:

Lack ofpatientand provider awareness.Lack ofawareness

among the patient population leads to difficult reconstructive problems.

Patients often presentwith advanced oralcancers due to prevalentto-

bacco and betel quid chewing and smoking, combined with infrequent

visits to doctors or dentists.Similarly,delayed presentation is frequent

for other types of cancers. In addition, many patients do not get primary

management of these conditions, leading to chronic wounds with osteo-

myelitis and burn deformities. Furthermore, providers in other specialties

often do not coordinate with plastic surgeons or are not aware of plastic

surgery principles. Continued patient education and interdisciplinary pro-

vider education are needed to overcome this challenge.

Paucity ofplastic surgeons.Of 30 plastic surgeons in Nepal,

only 2 are practicing outside the capitalcity of Kathmandu.Those

working outside the city do not work in teams, so often resection of a

tumor or wound is limited for fear of notbeing able to reconstruct.

The 2 senior authors (S.M.R. and K.K.N.) conducted 4 microsurgery

workshops in and outside Kathmandu in 2004–2006,training more

than 30 surgeons from differentspecialties (generalsurgery,cardiac

surgery, urology, neurosurgery, and orthopedics). Following these train-

ings,many participants have started doing recanalization of vas and

fallopian tubes,arteriovenous fistula creation,and coronary artery

bypass surgery.In addition,a plastic surgery residency program

was started in 2009 at our institution. Interplast Australia and New

Zealand has been providing funding for15 free flaps every year

and sending a team every year; RI is also sending 2 visiting

teams a year to continue training local physicians and nurse

Lack of ancillary staff. Qualified anesthesiologists are i

supply, as most anesthesiologists have not been exposed to

gery cases because such cases were rarely done in Nepal un

Microsurgical cases are very lengthy and often require seve

siologists for a single operation.The microsurgery workshop team

have brought their own anesthesiologists, which has helped

cal counterparts. Nurses who care for patients postoperative

during surgery are also an integral part of the team, althoug

similarly limited. Retention of knowledge has been a big cha

nurses in Nepal because of frequent loss due to emigration

education or training and better job opportunities. Some wo

ganizers have brought nurses to care for patients and train

although more regulartraining and retention of such ancillary st

are needed.10

Limited pathology services. Frozen section biopsy is no

able, making it difficult to ensure tumor clearance after exci

reconstruction following excision and biopsy involves higher

greater hospital length of stay. Finding operating time can a

cult. Immediate reconstruction is often performed to avoid t

lems, contributing to higher recurrence rate and related com

that include mortality.

Lack ofinstruments and equipment.Operating microscopes are

very expensive and out of reach for most reconstructive sur

developing countries. Many improvisations are suggested.17Use of oper-

ating loupes is a cheaper and equally effective alternative,18but operating

loupes cost US $350 to $500 in Nepal, which is prohibitively

for personal purchase. A microscope is required for replanta

to the palmararch,microneurosurgery,and supramicrosurgery,but

loupes can be used in so-called “macro-microsurgery.” This

plantations proximal to the palmar arch and free flaps with

than 1.5 mm, such as the latissimus, serratus, (para)scapula

dial forearm, rectus abdominis, dorsalis pedis, omentum, an

flaps.19 The lack of a microscope did not prevent us from doin

flaps in the first 3 years, yet its availability after donation by

made surgery easier. In addition, microinstruments are not

able in Nepal,although they can be imported eitherfrom India or

Pakistan.Even if obtained,microinstruments are difficultto keep in

working order because of damage during use and cleaning b

and transient staff.

Lack oftraining resources.Microsurgery has a steep learnin

curve and requires a lot of practice. Lack of a regular micros

ing laboratory is a limiting factor. We have a practice micros

being used occasionally during the workshops for residents.We also

lack a display system, which makes it difficult for several tra

sualizethe surgery simultaneously.In addition to microsurgical

TABLE 4.Complications Inside and Outside Workshops

Complications Inside Workshop Outside Workshop Total

Infection 8 (13%) 6 (13%) 14 (13%)

Complete flap loss 4 (7%) 5 (10%) 9 (8%)

Partial flap loss 3 (5%) 1 (2%) 4 (4%)

Hematoma/swelling 2 (3%) 1 (2%) 3 (3%)

Chest infection 2 (3%) 0 (0%) 2 (2%)

Death 3 (5%) 1 (2%) 4 (4%)

FIGURE 2.Radial artery forearm flap (RAFF) reconstruction of foot burn ulcer. A, Burn ulcer of anterior third of the food

presentation. B, Outcome of reconstruction with RAFF.

Nakarmi et al Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018

4 www.annalsplasticsurgery.com © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights res

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

anastomoses, flap harvesting skills also need to be learned and perfected

because of the importance of handling the flap and pedicle. Fresh per-

fused human cadavers can give almost real life experience,20,21

yet ca-

davers are not easily available in developing countries.22

Prohibitive cost. Microsurgery is costly because of long opera-

tive time, high utilization of medicines and supplies, and involvement

of many surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and other support staff in

the operating room and afterward. Although the government of Nepal

has made many health-related services free of cost,microsurgery is

not covered by government funding. Cases in our series were made pos-

sible largely because of the financial support of foundations (IAN,

RI) and other third parties. Costs are likely to be even higher in pri-

vate hospitals,discouraging such institutions from offering these

surgeries. Developing a robust microsurgery practice in Nepal will

require a more sustainable funding scheme.

CONCLUSION

Free flap transfer allows reconstruction of the most challenging

tissue defects that result from tumor resection, trauma, burns, and other

circumstances that frequently occur in developing countries. Microsur-

gery is thus a critical skill for surgeons in these settings, but there are

several challenges that prevent its widespread adoption. In Nepal, train-

ing and support of local health personnel have increased local capability

to perform microsurgical reconstruction and are an important step in

creating a sustainable model.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Damien Grinsell, FRACS, country director for

Nepal,Interplast Australia and New Zealand,ReSurge International,

and British Foundation for InternationalReconstructive Surgery

and Training.

REFERENCES

1. Shrime MG, Bickler SW, Alkire BC, et al. Global burden of surgical dise

an estimation from the provider perspective. Lancet Global Health. 20

S8–S9.

2. Alkire B, Raykar NP, Shrime MG, et al. Global access to surgical care:

ling study. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3:e316–e323.

3. Corlew DS. Estimation of impact of surgical disease through economic

of cleft lip and palate care. World J Surg. 2010;34:391–396.

4. Semer NB, Sullivan SR, Meara JG. Plastic surgery and global health: h

surgery impacts the global burden of surgical disease. J Plast Reconst

Surg. 2010;63:1244–1248.

5. Figus A, Fioramonti P, Morselli P, et al. Interplast Italy: a 20-year plast

constructive surgery humanitarian experience in developing countriePlast

Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1340–1348.

6. d'Agostino S,Del Rossi C, Del Curto S, et al. Surgery ofcongenital

malformations in developing countries: experience in 13 humanitaria

during 9 years. Pediatr Med Chir. 2001;23:117–121.

7. Magee WP,VanderBurg R, HatcherKW. Cleft lip and palate as a cost-

effective health care treatment in the developing world. World J Surg.

420–427.

8. AbenavoliFM. Operation Smile humanitarian missions.PlastReconstr Surg.

2005;115:356–357.

9. Persing J. The changing role of volunteer organizations and host coun

tions: a personal perspective. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68:5–6.

10. Silinzieds A,Simmons L,Edward KL,et al. Nurse education in developing

countries—Australian plastics and microsurgicalnurses in Nepal.PlastSurg

Nurs. 2012;32:148–155.

11. Corlew DS.Perspectives on plastic surgery and global health.Ann Plast Surg.

2009;62:473–477.

12. Citron I, Galiwango G, Hodges A. Challenges in global microsurgery: a

review of outcomes at an East African hospital.J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg.

2016;69:189–195.

13. Gupta S, Mahmood U, Gurung S, et al. Burns in Nepal: a population ba

assessment. Burns. 2015;41:1126–1132.

FIGURE 3.Medial plantar artery free flap reconstruction of cancer excision of foot. A, Ulcerating squamous cell carcinom

prior to excision. B, Reconstruction with contralateral medial plantar artery free flap.

FIGURE 4.Rectus abdominis free flap reconstruction of degloving injury of foot. A, Primary defect following debridemen

B, Inset of rectus abdominis free muscle flap. C, Final reconstruction with skin graft over muscle flap.

Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018 Free Flaps at phect-NEPAL Hospita

© 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.annalsplasticsurgery.com5

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

because of the importance of handling the flap and pedicle. Fresh per-

fused human cadavers can give almost real life experience,20,21

yet ca-

davers are not easily available in developing countries.22

Prohibitive cost. Microsurgery is costly because of long opera-

tive time, high utilization of medicines and supplies, and involvement

of many surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and other support staff in

the operating room and afterward. Although the government of Nepal

has made many health-related services free of cost,microsurgery is

not covered by government funding. Cases in our series were made pos-

sible largely because of the financial support of foundations (IAN,

RI) and other third parties. Costs are likely to be even higher in pri-

vate hospitals,discouraging such institutions from offering these

surgeries. Developing a robust microsurgery practice in Nepal will

require a more sustainable funding scheme.

CONCLUSION

Free flap transfer allows reconstruction of the most challenging

tissue defects that result from tumor resection, trauma, burns, and other

circumstances that frequently occur in developing countries. Microsur-

gery is thus a critical skill for surgeons in these settings, but there are

several challenges that prevent its widespread adoption. In Nepal, train-

ing and support of local health personnel have increased local capability

to perform microsurgical reconstruction and are an important step in

creating a sustainable model.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Damien Grinsell, FRACS, country director for

Nepal,Interplast Australia and New Zealand,ReSurge International,

and British Foundation for InternationalReconstructive Surgery

and Training.

REFERENCES

1. Shrime MG, Bickler SW, Alkire BC, et al. Global burden of surgical dise

an estimation from the provider perspective. Lancet Global Health. 20

S8–S9.

2. Alkire B, Raykar NP, Shrime MG, et al. Global access to surgical care:

ling study. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3:e316–e323.

3. Corlew DS. Estimation of impact of surgical disease through economic

of cleft lip and palate care. World J Surg. 2010;34:391–396.

4. Semer NB, Sullivan SR, Meara JG. Plastic surgery and global health: h

surgery impacts the global burden of surgical disease. J Plast Reconst

Surg. 2010;63:1244–1248.

5. Figus A, Fioramonti P, Morselli P, et al. Interplast Italy: a 20-year plast

constructive surgery humanitarian experience in developing countriePlast

Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1340–1348.

6. d'Agostino S,Del Rossi C, Del Curto S, et al. Surgery ofcongenital

malformations in developing countries: experience in 13 humanitaria

during 9 years. Pediatr Med Chir. 2001;23:117–121.

7. Magee WP,VanderBurg R, HatcherKW. Cleft lip and palate as a cost-

effective health care treatment in the developing world. World J Surg.

420–427.

8. AbenavoliFM. Operation Smile humanitarian missions.PlastReconstr Surg.

2005;115:356–357.

9. Persing J. The changing role of volunteer organizations and host coun

tions: a personal perspective. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68:5–6.

10. Silinzieds A,Simmons L,Edward KL,et al. Nurse education in developing

countries—Australian plastics and microsurgicalnurses in Nepal.PlastSurg

Nurs. 2012;32:148–155.

11. Corlew DS.Perspectives on plastic surgery and global health.Ann Plast Surg.

2009;62:473–477.

12. Citron I, Galiwango G, Hodges A. Challenges in global microsurgery: a

review of outcomes at an East African hospital.J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg.

2016;69:189–195.

13. Gupta S, Mahmood U, Gurung S, et al. Burns in Nepal: a population ba

assessment. Burns. 2015;41:1126–1132.

FIGURE 3.Medial plantar artery free flap reconstruction of cancer excision of foot. A, Ulcerating squamous cell carcinom

prior to excision. B, Reconstruction with contralateral medial plantar artery free flap.

FIGURE 4.Rectus abdominis free flap reconstruction of degloving injury of foot. A, Primary defect following debridemen

B, Inset of rectus abdominis free muscle flap. C, Final reconstruction with skin graft over muscle flap.

Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018 Free Flaps at phect-NEPAL Hospita

© 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.annalsplasticsurgery.com5

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

⊘ This is a preview!⊘

Do you want full access?

Subscribe today to unlock all pages.

Trusted by 1+ million students worldwide

14. Gupta S,Gupta SK,Devkota S,et al. Fall injuries in Nepal:a countrywide

population-based survey. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81:487–494.

15. Nangole WF, Khainga S, Aswani J, et al. Free flaps in a resource constrained

environment: a five-year experience-outcomes and lessons learned. Plast Surg

Int. 2015;2015:194174.

16. Trivedi NP, Trivedi P, Trivedi H, et al. Microvascular free flap reconstruction for

head and neck cancer in a resource-constrained environment in rural India. Indian

J Plast Surg. 2013;46:82–86.

17. Peltola TJ,MäntyjärviM, Teräsvirta M,et al. Build your own multipur-

pose,economically priced portable stereo microscope.Trop Doct.2000;30:

28–29.

18. PannucciCJ, Basta MN,Kovach SJ,etal.Loupes-only microsurgery is a safe

alternative to the operating microscope: an analysis of 1,649 consecu

breast reconstructions. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2015;31:636–642.

19. Pieptu D, Luchian S.Loupes-only microsurgery. Microsurgery. 2003;23

20. Carey JN,MinnetiM, Leland HA,et al. Perfused fresh cadavers:method for

application to surgical simulation. Am J Surg. 2015;210:179–187.

21. Carey JN,RommerE, SheckterC, et al. Simulation ofplastic surgery and

microvascular procedures using perfused fresh human cadavers. J Pla

Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:e42–e48.

22. Anyanwu GE,Udemezue OO,ObikiliEN. Dark age of sourcing cadavers in

developing countries: a Nigerian survey. Clin Anat. 2011;24:831–836.

Nakarmi et al Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018

6 www.annalsplasticsurgery.com © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights res

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.View publication statsView publication stats

population-based survey. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81:487–494.

15. Nangole WF, Khainga S, Aswani J, et al. Free flaps in a resource constrained

environment: a five-year experience-outcomes and lessons learned. Plast Surg

Int. 2015;2015:194174.

16. Trivedi NP, Trivedi P, Trivedi H, et al. Microvascular free flap reconstruction for

head and neck cancer in a resource-constrained environment in rural India. Indian

J Plast Surg. 2013;46:82–86.

17. Peltola TJ,MäntyjärviM, Teräsvirta M,et al. Build your own multipur-

pose,economically priced portable stereo microscope.Trop Doct.2000;30:

28–29.

18. PannucciCJ, Basta MN,Kovach SJ,etal.Loupes-only microsurgery is a safe

alternative to the operating microscope: an analysis of 1,649 consecu

breast reconstructions. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2015;31:636–642.

19. Pieptu D, Luchian S.Loupes-only microsurgery. Microsurgery. 2003;23

20. Carey JN,MinnetiM, Leland HA,et al. Perfused fresh cadavers:method for

application to surgical simulation. Am J Surg. 2015;210:179–187.

21. Carey JN,RommerE, SheckterC, et al. Simulation ofplastic surgery and

microvascular procedures using perfused fresh human cadavers. J Pla

Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:e42–e48.

22. Anyanwu GE,Udemezue OO,ObikiliEN. Dark age of sourcing cadavers in

developing countries: a Nigerian survey. Clin Anat. 2011;24:831–836.

Nakarmi et al Annals of Plastic Surgery• Volume 00, Number 00, Month 2018

6 www.annalsplasticsurgery.com © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights res

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.View publication statsView publication stats

1 out of 7

Your All-in-One AI-Powered Toolkit for Academic Success.

+13062052269

info@desklib.com

Available 24*7 on WhatsApp / Email

![[object Object]](/_next/static/media/star-bottom.7253800d.svg)

Unlock your academic potential

Copyright © 2020–2026 A2Z Services. All Rights Reserved. Developed and managed by ZUCOL.